John Michael McCarty's Blog, page 5

November 17, 2018

Duncans Mills, the Blue Heron

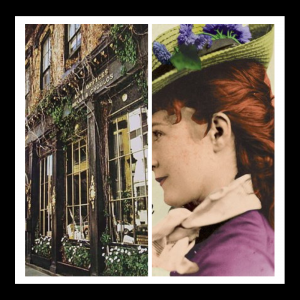

The Blue Heron was built soon after the town of Duncans Mills was established in 1877 and has served as a trusted watering hole ever since. Several history buffs whisper that it is the oldest tavern along the entire length of the Russian River. The Blue Heron is known today for its hearty pub food and selected spirits.

“What the Shuck”, the saloon’s intrepid cook, serves barbecued oysters alongside Sunday afternoon music on the patio. My dear friend Dave Camarillo, a.k.a Dr. Love, and his Blue Burners are a favorite (voted best blues band in the county by Krush radio, 95.9 FM).

Blue Heron and Pink Elephant:

There is a strong connection between the Blue Heron and Pink Elephant bar, which is located in nearby Monte Rio and dates back to the 1930’s. Tom O’Bryan, who reopened the Blue Heron in 2008, purchased the Pink two years later from Tim Parker. Unfortunately, a complaint from a “close associate”, triggered a county inspection, which deemed that Parker had exceeded the scope of his permit by attempting to relocate the bathrooms. Parker estimated the septic system work alone would cost between $60,000 to $80,000. Some people in town talked of passing the hat for donations to reboot the bar but no dice.

O’Bryan supposedly has reached an agreement with county officials regarding the septic issue. In addition, it is rumored that he will soon procure a liquor license from the owner of Lucy’s, another Monte Rio restaurant/bar that is changing hands after the first of the year. Perhaps the Pink will finally restart. Thank you Tom O’Bryan of the Blue Heron.

The post Duncans Mills, the Blue Heron appeared first on John McCarty.

November 11, 2018

Duncans Mills Railroad Days

The first train arrived in the new town of Duncans Mills in 1877, becoming the northernmost terminus of the North Pacific Coast R.R. (NPC). The NPC operated almost 93 miles of track while a ferry connected San Francisco to Sausalito where the line began. The railroad carried redwood lumber, local dairy and agricultural products, express and passengers.

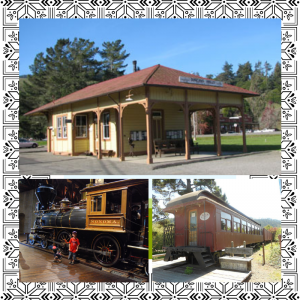

The NPC developed into the North Shore Railroad (NSR) that later became part of the North Western Pacific (NWP). The depot (upper photo) was erected in 1907 and restored in 1971.

Duncans Mills:

Standing nearby today on narrow-gauge tracks (36″) are the restored NWP coach, two box cars and Caboose #2 (lower right photo), which was part of the last train to Duncans Mills in 1935. Old No. 12, dubbed the Sonoma (lower left photo), spilled steam from its stack while hauling as many as thirteen cars on a single run (Sonoma is housed at the railroad museum in Sacramento).

During the 1906 earthquake, Duncans Mills lost its three Victorian hotels. Essentially the entire village was destroyed and left to the sprouting weeds for years to come. Not too soon after the town rose from the ashes, Mother Nature dealt another cruel blow. On September 17, 1923 a moonshine still blew up, igniting a blaze that roared through the lumber mills from Guerneville through Cazadero and Duncans Mills to Jenner. But the good citizens of Duncans Mills carried on. With the lumber trade on the fritz, passenger service picked up the slack over a standard gauge track (56″). Service existed to and from Duncans Mills with a daily patron average of nearly 225. The NWP offered “dollar days” on the weekend with a roundtrip fare of $1.25 from San Francisco to any point along the Russian River. And then the Depression arrived in earnest to challenge the town once again. With the railroad running over a million dollars in the red, the town slowly faded until a 1976 restoration project, associated with the celebration of the U.S. Bicentennial, brought about a period of building restoration. It’s seems as though these Duncans Mills folks don’t want to surrender. A hardy breed for sure.

The post Duncans Mills Railroad Days appeared first on John McCarty.

November 8, 2018

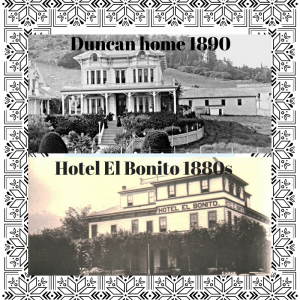

Duncans Mills Moniker

Duncans Mills gets its moniker from the Duncan brothers, Samuel and Alexander. Some say they were the first sawmill operators on the Sonoma Coast. They originally founded a mill just east of Freestone before relocating near the mouth of the Russian River near today’s Bridgehaven. Many a log, which floated downstream to the site, would wash out to sea in bad weather. Another disadvantage to this location was the lumber would have to be hauled by horse-drawn tram to Duncan Point (just south of Wright’s Beach) where waves, currents and weather often did not cooperate with the loading of timber onto waiting ships headed for the San Francisco market. Two events in 1877 changed the town’s destiny forever. A fire burned much of the mill, and the North Pacific Coast Railroad was approaching inland.

Duncans Mills gets its moniker from the Duncan brothers, Samuel and Alexander. Some say they were the first sawmill operators on the Sonoma Coast. They originally founded a mill just east of Freestone before relocating near the mouth of the Russian River near today’s Bridgehaven. Many a log, which floated downstream to the site, would wash out to sea in bad weather. Another disadvantage to this location was the lumber would have to be hauled by horse-drawn tram to Duncan Point (just south of Wright’s Beach) where waves, currents and weather often did not cooperate with the loading of timber onto waiting ships headed for the San Francisco market. Two events in 1877 changed the town’s destiny forever. A fire burned much of the mill, and the North Pacific Coast Railroad was approaching inland.

Duncans Mills:

The brothers decided to move the surviving buildings by barge upstream three miles to the present-day locale. By 1880 Duncans Mills was the largest town along the lower reaches of the Russian River, boasting a post office, telegraph office, train depot, two hotels, saloon, meat market, blacksmith shop, shoe shop, livery stable, dance hall, school and a notion store for your sewing supplies, fabrics, buttons, snaps, etc. The population of the town numbered about 250 souls at this time. According to the 2000 census, the town now claims seventy-five fewer residents. Some would consider that progress.

The post Duncans Mills Moniker appeared first on John McCarty.

November 5, 2018

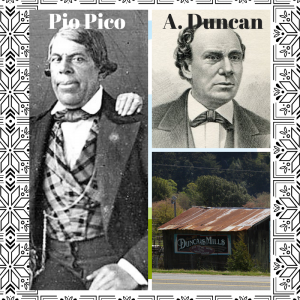

Duncans Mills, the Early Days

Duncans Mills, the early days, tells a tale of greed, international tension and fate. Once upon a time it was part of Alta California, which was under the Mexican governorship of Pio Pico. He was often ridiculed for his physical deformities resulting from acromegaly, a disease caused by the unregulated release of hormones causing abnormal growth of hands, feet and face. One newspaper critic called him the “ugliest man in the territory”. It is easy to understand why Pico developed a tough skin. He scorned his enemies and protected his allies. When the Russians abandoned Fort Ross in 1841 and sold the surrounding land to John Sutter, Governor Pico exposed his combative side and went into action. He issued the sale “null & void” and instead gave the land to a close friend, Manuel Torres, as part of the Rancho Muniz Land Grant.

Duncans Mills, the early days, tells a tale of greed, international tension and fate. Once upon a time it was part of Alta California, which was under the Mexican governorship of Pio Pico. He was often ridiculed for his physical deformities resulting from acromegaly, a disease caused by the unregulated release of hormones causing abnormal growth of hands, feet and face. One newspaper critic called him the “ugliest man in the territory”. It is easy to understand why Pico developed a tough skin. He scorned his enemies and protected his allies. When the Russians abandoned Fort Ross in 1841 and sold the surrounding land to John Sutter, Governor Pico exposed his combative side and went into action. He issued the sale “null & void” and instead gave the land to a close friend, Manuel Torres, as part of the Rancho Muniz Land Grant.

Duncans Mills:

Rancho Muniz extended from Slat Point to the Russian River including the present-day area of Duncans Mills. Sutter had his own militia and the fear of violence was very real. With the cession of Alta California to the U.S. following the Mexican-American War, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided that this land grant be honored. If Sutter had succeeded in his claim of ownership, would he have sold part of his land to Alexander Duncan as Manuel Torres eventually did? My guess is that Sutter would not have in order to prosper from the future potential of lumber. Our small hamlet along the Russian River could have easily been labeled Sutter’s Mill instead of Duncans Mills. And to what extent would this have changed the area? Who knows, but the name “Sutter” back in the day carried a lot of weight.

The post Duncans Mills, the Early Days appeared first on John McCarty.

October 20, 2018

Secret World War Two Tunnels

A secret World War Two tunnel supposedly runs somewhere north of Civic Center in San Francisco. Built in the early 1900s, this passage used to transport soldiers and materials. Behind a pair of twenty-foot gates, there is a huge metal door. Thrill seekers tell of their adventures deep inside this maze. Doubters insist the photo on the left simply appears to be a sewer, others testify that this urban legend is true. If you are of the latter persuasion, keep in mind that presumably inside there’s a nuke-esque sign that reads “Fallout Shelter”, and best believe I’ll be there if necessary.

Secret Bunker Tunnels continued:

A second W.W.II underground bunker in the City was featured on The History Channel in 2009. The series, Cities of the Underworld, told in one episode of classified military headquarters beneath San Francisco. A fifteen-foot long tunnel led to the edge of a hundred-foot man-made cement cliff. A metal ladder, pounded into the concrete wall, took one downward to a military complex. Hidden far below the city’s surface were a series of ballroom-size caverns, tunnels and smaller rooms (right photo) that once existed in a long-forgotten era. The History Channel show initiated a flood of curiosity seekers. The authorities eventually discovered the hidden entrance and shut it down not too long after it aired.

The post Secret World War Two Tunnels appeared first on John McCarty.

October 14, 2018

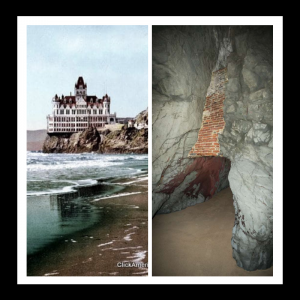

Secret Tunnel Under Cliff House

At Land’s End, usually frequented only by raccoons, is a forgotten tunnel under the Cliff House in San Francisco. In 1891 a grizzly old miner announced there was a fortune in the coal vein he’d found. On March 28 of that same year, readers of the Chronicle were greeted with astonishing news: Coal Discovered in the City! “An old miner has found a vein hugging the coastline below the bluff at the Cliff House (left photo). ‘Do try to buy up that land,’ miner Charles Jackson told Superintendent H.H. Lynch of the Cliff House and Ferries Railway. ‘There is a fortune in it, for I am sure there are thousands of tons of good coal in that district.'”

Tunnel Under Cliff House:

But the vein and tunnel under the Cliff House (right photo) sat on land owned by Adolph Sutro, the Comstock Lode magnate who would later become mayor of San Francisco as well as build the famous Sutro Baths. Sutro immediately went to work. He put a crew of miners digging a tunnel about 200 feet below the Ferries Railway track, which was then about the same distance from sea level. Miner Jackson’s discovery was confirmed: There was indeed coal under Land’s End. But the mine was never fully developed despite the city’s reliance on coal in the late 19 century. No one knows why. Today the story of San Francisco’s coal mine is largely forgotten. The tunnel is still there, although in decaying condition, thanks to decades of erosion. Mudslides, earthquakes and storms have collapsed portions of the tunnel and nearly buried its eastern opening. Accessing the tunnel is no picnic. Technical climbing and careful attention to tides is required. For more on the Secret Tunnels of San Francisco, scroll to the bottom of this page and click on “Tunnels”. Cheers and happy adventures!

The post Secret Tunnel Under Cliff House appeared first on John McCarty.

October 11, 2018

Secret Tunnel Beneath San Francisco Speakeasy

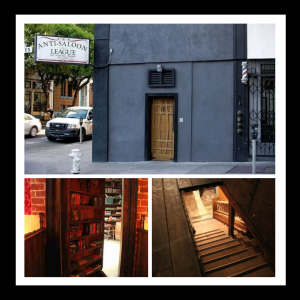

Another example of a secret tunnel beneath a San Francisco speakeasy is at the present site of a Bourbon and Branch saloon at 501 Jones St. near O’Farrell. Look for the Anti-Saloon League sign (upper photo). Between 1923-1935 the nondescript building housed the J.J. Russell Cigar Shop, but an aromatic havana was not their main product. One would knock on the main door and provide a password (today, you must make reservations via their website where you are given a password to be used just as in olden days). Once inside, if you requested a particular cigar, an employee would lead the way through a trap door to the basement where a bartender would serve the finest bootleg contraband shipped from Vancouver. There was a brass bell, which was connected to a lever behind the counter upstairs. If this sounded, a warning would be sent throughout the speakeasy. Patrons would scurry through various tunnels. The Ladies Exit, for example, granted safe passage to Leavenworth Street, a full block away.

Another example of a secret tunnel beneath a San Francisco speakeasy is at the present site of a Bourbon and Branch saloon at 501 Jones St. near O’Farrell. Look for the Anti-Saloon League sign (upper photo). Between 1923-1935 the nondescript building housed the J.J. Russell Cigar Shop, but an aromatic havana was not their main product. One would knock on the main door and provide a password (today, you must make reservations via their website where you are given a password to be used just as in olden days). Once inside, if you requested a particular cigar, an employee would lead the way through a trap door to the basement where a bartender would serve the finest bootleg contraband shipped from Vancouver. There was a brass bell, which was connected to a lever behind the counter upstairs. If this sounded, a warning would be sent throughout the speakeasy. Patrons would scurry through various tunnels. The Ladies Exit, for example, granted safe passage to Leavenworth Street, a full block away.

Secret Tunnel:

Today the saloon capitalizes on its notorious reputation, making available the original five rooms used during Prohibition. Each has a secret entrance such as the Ipswitch Room in the basement where one gains access via a trap door (photo bottom right) or the Wilson & Wilson Room via a faux bookshelf (photo bottom left). The secret tunnels are marked where they once served a clandestine clientele, but due to insurance requirements they have since been barricaded. Have a stiff one in the same space where perhaps a distant relative once imbibed. Cheers!

The post Secret Tunnel Beneath San Francisco Speakeasy appeared first on John McCarty.

September 30, 2018

Secret Tunnels of Chinatown, cont.

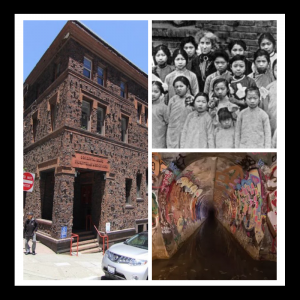

Secret tunnels in Chinatown included the one emanating from the present-day Cameron House at 920 Sacramento Street (left photo). In the 19th and early 20th centuries, neither Chinese American leaders nor white officials in San Francisco made any real effort to curb the tide of a growing slave trade. With few legal resources, a Protestant missionary by the name of Donaldina Cameron (upper right photo) extricated upwards of three thousand girls from serfdom. They were known as mui tsai and sold into prostitution or domestic work by the tongs who ran the brothels. The rescue work was dangerous as Miss Cameron received ongoing death threats from the gangs. Bold beyond description, she would chase down leads to free the women. On one occasion, the missionary shared a slave girl’s cell in order to save her.

Secret Tunnel under Cameron House:

While Miss Cameron had the assistance of the Chinatown Squad, other officers from downtown accepted bribes to aid the tongs. When tong owners came with search warrants to the brick building on Sacramento, the girls would scurry down to the basement where they would escape through a secret tunnel that led to a maze of sewers (lower right photo). Donaldina Cameron died in 1968. Today, the Cameron House still serves the city’s Asian American community, offering a range of social services and popular youth programs. Access to the secret tunnel has been bricked off but remains well-marked for visitors to remind them of a past once teeming with abuse.

The post Secret Tunnels of Chinatown, cont. appeared first on John McCarty.

September 23, 2018

Secret Tunnels of Chinatown

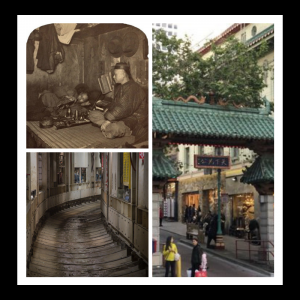

The 1906 earthquake and fire unearthed the vast system of secret tunnels beneath Chinatown in San Francisco. Many believe the catacombs stretched throughout the sixteen-block enclave and into North Beach. The leaders of the tongs guarded the whereabouts of entrances to these passageways with their lives. The underpasses hid thriving opium dens (upper left photo), torture and execution chambers as well as escape routes that confounded authorities for decades. Mayor Eugene Schmitz (mayor 1902-1907) and attorney Abe Ruef would use their influence to scare Chinese out of their downtown enclave.

Gang Wars:

Schmitz was found guilty of corruption and sentenced to five years at San Quentin before the Court of Appeals overturned his conviction. But if racist attacks were a fact of life, so were the tong wars, some of which were rekindled as gang battles in the 1970s. Extortion is still rampant. If you ever spot a red piece of paper attached to a storefront window, it is a signal that that particular owner has paid his/her protection money for the month. I personally worked with a Joe Boys gang member who drove the getaway car and turned state’s evidence in the Golden Dragon Restaurant shooting in 1977. It was part of his probation—performing community service work as my personal consultant while a handful of us dealt with the new influx of Asian gangs at Mission High School. He later confided in me that the tunnels were still used. Many, however, believe this to be urban myth. Side notes: Joe Boys, Wah Ching, and Worms were split apart, dispersing several members who had attended Galileo High after the attempted assassination of the principal there. Also, there is a Muni subway (lower left photo), which is nearing completion, that will connect Moscone Center with Chinatown.

The post Secret Tunnels of Chinatown appeared first on John McCarty.

September 13, 2018

Secret Tunnels of San Francisco – Part 2

A secret tunnel runs under the former San Francisco law office of Melvin Belli (1907-1996), the “King of Torts”, whose client list included Errol Flynn, Muhammad Ali, The Rolling Stones, Mae West, Jack Ruby, and others. After winning a court case, Belli would raise a Jolly Roger flag over his office building and fire a cannon, mounted on the roof, to announce the victory and the impending party. The structure at 722 Montgomery Street in the Barbary Coast District was built circa 1850. Belli claimed that it was a Gold Rush era brothel, later to become the Melodeon Theater where one of the most acclaimed and beloved entertainers in the City’s history performed. Lotta Crabtree was a noted singer with a zealous fan base.

Secret Tunnel:

To avoid the harangues of intoxicated patrons, she would exit via a secret tunnel constructed just for her. While conducting a field study on behalf of St. Mary’s College in the 1980’s, my students and I were invited inside. We stepped under crystal chandeliers, past red velvet drapes and a statue of a Swiss Madonna, wearing an ostrich plume from South Africa. A discreet staircase came into view, exposing the entrance to the passageway. It once led under an adjoining alley to a horse stable, allowing a quick getaway for Miss Crabtree. City officials declared it unsafe following the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989. While renovating the building for a future Belli museum, workers unearthed the tunnel to find the remains of two bodies. Belli married six times with five divorces, declaring bankruptcy toward the end. I often wondered if he ever used the tunnel for his own personal escapes.

The post Secret Tunnels of San Francisco – Part 2 appeared first on John McCarty.