Paul R. Boudreau's Blog, page 5

April 13, 2020

Chapter 7: A Modern Allegory of the Spirituality Spectrum: The Gurdjieff Work

Of course human examination of who and what we are has continued throughout the ages and we have much written material to contribute to our present day understanding. Next in our presentation of the creative irrational we select the much more recent the works of 19th and 20th Century researcher G.I. Gurdjieff. Next in the Table 2 in lines 4, we cite the works describing the terminology developed by this 20th Century mystic, philosopher and spiritual teacher[1]. Gurdjieff studied the esoteric teachings of cultures in the Middle East. He developed his own approach to the question of human existence based on the various potential “Reasons” of a human. At the base of his teaching is the idea that we as individuals are not a single whole entity. On the left hand side of the spectrum in Table 2, we note that he taught that we are a collection of three independent Reasons or functionings. Gurdjieff called them “Reason of Body” “Reason of Feeling”’ and “Reason of Thinking”, thus emphasizing the virtual separation among the various members of the set as separate entities. Gurdjieff argued that as a result of this separation and isolation of functions within us, we live our lives in a waking sleep. As a result, he referred to average humans as “Three-Brained Beings” because of the prominence that these lower three Reasons have in our ordinary lives. He taught, however, that the existence of higher, more fully conscious levels of existence are natural for real human existence. His metaphoric style, with many new and unfamiliar terms, deliberately requires hard work on the part of the reader who ventures to comprehend it. Nevertheless, the body of his work can be seen as similar to others that we present in this book.

As we have shown, we are far from being the first to consider these ideas of levels of consciousness and higher Being. Expressions of the more-than-merely physical world have been made by humans since the beginning of time. In fact we are arguing that this is what makes us human. Appreciation for this, our creative irrational, is a common thread that runs through the history of Homo sapiens. In this section we present a look into the work of an individual from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, G.I. Gurdjieff, who spent his life working with individuals to help them awaken from their waking sleep, to experience the more-than-merely physical components of life within us so that we might become more like the “real” humans we need to be[2].

Gurdjieff was born in 1855 in Alexandropol, Armenia in the southern foothills of the Caucasus Mountains between the Black and Caspian Seas[3]. He spent his life travelling and searching the world for an understanding of the human condition. He developed and taught a system of self-study based on ancient esoteric knowledge that has since become known as “The Work”. He established a centre for study and work called “The Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man”, in Fontainebleau, France just south of Paris where he died in late 1949. Groups following his method continue to function in various locations around the globe today. It is important to note that Gurdjieff intentionally demanded constant work of his students to continually challenge themselves physically, emotionally and mentally to develop their levels of consciousness. He refers to such a practice of constant challenges as “Conscious Labours and Intentional Suffering”. He maintained that only by aspiring to such a manner of self observation could a person hope to develop one’s Self, which he recognized as the aim of all sensible human beings. We find ourselves much indebted to him. Later authors have been publishing for decades attempting to convey the substance of his teachings[4]. Readers are encouraged to explore the extensive body of work that exists. Intensive study must be left to readers to undertake for themselves.

In approaching his thoughts on the human condition it is important to note that language was not a challenge to Gurdjieff. He was a polyglot speaking Armenian, Greek, Russian and Turkish along with a working facility with several European languages including English. Yet, when we come to his writings he presents readers with seemingly absurd images and concepts. Gurdjieff produced three books that are referred to as the “All and Everything” trilogy. They are “Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson”[5], “Meetings With Remarkable Men”[6] and “Life is Real Only Then, When ‘I Am’ ”[7]. In none of these books does he simply and clearly lay out his ideas about the state of humans and his recommendations on how to improve consciousness. Readers are constantly required to struggle to decipher the meaning of long and involved sentences and paragraphs. He avoided using words that would easily allow us to make a mental note and mindlessly move on. He was well aware of how easily we get distracted by our lower Reason of Thinking, or as he called it “Degindad” (Table 2).

In regard to the levels of a real human, Gurdjieff’s view is buried in Beelzebub’s Tales where he writes about one of the “Laws of the Universe” that he called “Heptaparaparshinokh”. The basis of this Law is that any active process can be regarded as consisting of a series of seven distinctive steps. Its name comes partially from the Greek word for the number seven “Hepta”. We can gain some insights into this meaning from something that we are accustomed to hearing in music as the “octave”. There we have a succession of seven tones in an octave scale, an eighth tone beginning the repeat of the original sequence one octave higher. In such a situation the final note following any sequence of seven musical notes in the scale leads to the repeat of the pattern. We in the Western World have learned and become accustomed to calling it an octave[8]. Gurdjieff alternatively refers to Heptaparaparshinokh as “The Law of Octaves”. Of course most musicians understand that development of this octave series is not an isolated event, but follows a particular historical series that most of us have now become accustomed to. For example, we may take the first three notes of this octave scale: “Doh, Re, Me”. Almost everyone who has done any group singing will recognize how seemingly natural it is for us to sing this simple sequence repeatedly – up three notes, then down three notes, then up again. The simple repetition seems quite natural to us, and is often utilized by singers “warming up”. Such simple practices can effectively impress on us a certain feeling, tone or mood. Musically Gurdjieff, as all artists, composed pieces in which the Law of Octaves is used to deliberately promote certain moods in the listener.

But Gurdjieff definitely did not restrict the application of Heptaparaparshinokh to music alone. The study of this Law of Seven permits us to seek to understand psychological ideas of harmony other than those that are strictly associated with physical phenomena, but that are still a part of our living experience. For instance, it is useful in appreciating our inability to hold an intention beyond the initial motivation for action. It draws attention to our difficulty in progressing from an initial movement of the “do, re, me sequence” to a full octave through the difficult intervals of the “me” and “fa” steps in the octave progression. These naturally occurring difficult intervals impede our reaching goals and objectives in our lives. So whether it is an intention to lose weight, or to be more relaxed, or to be a better person, Gurdjieff’s concept of Heptaparaparshinokh seems to capture some key properties that are not clearly recognized in our usual functioning. It is evident that there is much important information buried in the obscure lexicon of Gurdjieff’s writing that applies to the creative irrational and the spiritual levels that can be experienced in much of our daily lives.

Three Brained Beings

Recognizing that Gurdjieff deliberately avoided clear language, what can we present here that could contribute to our creative irrational concept, spirituality and the levels of human consciousness? Of critical importance, the basic Gurdjieff model of the average modern everyday participant in Western culture was that we are “three-brained beings”. He meant this in no way as a complement. He identified the body, emotion and mind as separate, distinct independent functions within us. As shown by us in the three cells to the left of Row 4 in our Spirituality Spectrum in Table 2 these are the three lowest levels of human “Reason”.

While we present his concepts as levels of “Reason” it is important to bear in mind his efforts to use words that are commonly used by Western minds, but may mean much more. In the typical manner of Gurdjieff’s teaching his language is difficult and requires unusual effort for followers to understand it. It is for this reason we also present here the terminology of one of his students, P.D. Ouspensky. In row 5 of Table 2 we present Ouspensky’s complimentary, more simplified version of Gurdjieff’s thoughts. He published extensively about his experiences in groups led by Gurdjieff as well as extensive studies of later work with his own pupils. Ouspensky was more of a thinking type and as a result his writings are much more approachable by individuals in Western culture. In contrast to Gurdjieff’s deliberate cloaking of his thoughts in mystery, Ouspensky, refers to the separate independent functions as simply “centres”, thereby displaying them more as aspects of a single body. We show, starting at the left side of row 5, Ouspensky’s names for the first three, lower categories of our functionings. Yet with Gurdjieff’s obscure terminology and Ouspensky’s potential oversimplification, both clearly recognize our need to appreciate several levels of being and the striving for higher consciousness that we call the creative irrational and spirituality.

While Ouspensky recognized the importance of Gurdjieff’s ideas he presented his own versions of them in his own style, a style that generally appeals more readily to modern Western readers (Row 5 in Table 2). For instance Ouspensky presents our three brains as independent “centres”. The more approachable concept of “centre” refers to our independent internal “functionings”. In our experience Ouspensky’s clarity provides an important introduction to the more challenging terms presented in detail by Gurdjieff but the overall work and effort of understanding these concepts, whether referred to as Reasons, centres or functionings, is critical to fully experiencing and appreciating our disjunctive day-to-day operations.

Returning to the question of us as “three-brained beings”, we continue our introduction with reference to long established esoteric studies of human functions by initiates from other non-western tradition. In their study of human development, both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky encountered individuals who concentrated their work on only one of their specific functionings or centers[9] & [10]. These ancient forms of study and self-work are known as:

1) The Way of the Fakir focusing on the “body”[11];

2) The Way of the Monk focusing on the “emotion” [12]; and,

3) The Way of the Yogis focusing on the “mind” [13].

These three Ways or lifestyles for self-study require initiates to undergo extensive training and exercise in an effort to reach higher levels of states of spiritual existence and consciousness. These approaches generally require work isolated away from ordinary life. While monks, or at least the image of a stylized monk, are somewhat acceptable in the development of Western Christian thought, we are less familiar with the other “Ways”.

As an example of the Way of the Fakir, we mention Egypt's most famed fakir from the 1920s Tahra Bey[14] as reported by Paul Brunton[15]. Bey was trained and practiced as a fakir to accomplish seemingly impossible physical feats. According to Brunton, Bey subjected himself to scientific study while with great control and intention he deliberately put himself in death-like trance states. He was able to exist while his physical body displayed nothing of what we would consider signs of life. Of significance to our study, Bey is said to have had the ability to separate his physical body from his other centres, thus maintaining himself isolated from a heartbeat, breath and sensory reactions. As a result of this manipulation in his state, Bey was reported to have been physically rejuvenated upon regaining consciousness. While impossible for us to be sure, it seems to us that Bey’s experience, may have been similar to what took place in the 5,000-year old Ancient Egyptian pharaonic initiation rites suggested in the Pyramid Texts.

While the modern western world has many examples of the use of yoga for improving health and well-being, they are a mere shadow of what Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and Brunton would have encountered in the early 20th Century in Central and East Asia. Yogi’s of that time and place were intent on following a lifestyle in search of higher levels of consciousness, quite different from the common modern day yoga practices associated with ordinary health and well-being. The real yoga self-study focused on their “Reason of Thinking”.

Building on the three independent Ways of the fakir, monk and yogi, Gurdjieff developed an approach where an individual works to develop simultaneously his/her three lower brains in our ordinary day-to-day lives. Thus Ouspensky’s teachings are often referred to as the Fourth Way[16]. So from Gurdjieff’s work we come to appreciate that he is talking about a nature that is based on three independent functions: “doing”, “feeling”, and “thinking”, that are relatively easy to identify in ourselves. When we come to seriously study them we may also come to realize that while they may seem to act almost independently of each other, according to this prescription of “three-brained”, they must be identifiable as aspects of a being with at least the possible reality of a central unity. It is the bringing of this supposedly unified set of functionings into a true unity of action that includes the proper operation of our other higher Reasons shown in Table 2that is the central theme of Gurdjieff’s whole teaching and the reason why we need to deal with it here. And while going beyond our lower three brain operation is not so simple, with persistent practice and attention, our own experience suggests that it is possible to find all three functions operating at once.

The Higher Reasons of Real Humans

Here we turn our focus to Gurdjieff’s grand allegory of human history and our present state that is found in Beelzebub’s Tales. It is nominally an allegorical journey of the central figure Beelzebub across the universe in a spaceship with his grandson. Throughout the tale we are provided with an expansive and distracting view of our world. Nothing is stated in simple terms. It deserves intensive study, but we can only summarize certain points here that pertain to the levels of human consciousness. So far in this section we have focused on the three lower, elementary stages of consciousness on the left side of Table 2. These are or can be directly addressed through our self-study and with prolonged effort can result in a degree of “self-knowledge”. Here we find that there are possibilities working towards those higher levels to which Gurdjieff gave the strange names used in line 4 of Table 2.

The story ends with Beelzebub receiving the greatest of honours and recognition, by beings with even higher understanding. Such a story cannot be omitted from our consideration of our higher levels of awareness and consciousness. In spite of Gurdjieff’s stated objectives of “burying the bone deeper”[17] there are definite insights that, with sufficient attention, the reader can penetrate to understand the various levels of Being and appreciate the difficulties encountered in the seeing of these levels within oneself.

In the allegory the final “transformation” in Beelzebub’s development of “level of being” is represented by the sprouting of forked horns on the top of his head. Gurdjieff describes a scene that occurs during Beelzebub’s final appearance on earth. The story tells of how a group of assembled observers witness the expression of Beelzebub’s levels of being through the growth of new prongs on his horns. His antlers keep growing new prongs up to and including a special fifth fork. This indicates that his being had indeed reached only one step below the level of what he called “The Sacred Anklad” or the “Reason of God” which, as shown in Table 2, is the step just before the highest level of “OUR ENDLESS CREATOR”.

We present here one small section from Beelzebub’s Tales to explore his representation of the higher levels Being. We quote it as follows:

“At first, while just the bare horns were being formed, only a concentrated quiet gravely prevailed among those assembled. But from the moment that forks began to appear upon the horns a tense interest and rapt attention began to be manifested among them. This latter state proceeded among them, because everybody was agitated by the wish to learn how many forks would make their appearance on Beelzebub’s head, since by their number the gradation of Reason to which he had attained according to the sacred measure of Reason would be defined.

“First one fork formed, then another, and then a third, and as each fork made its appearance a clearly perceptible thrill of joy and unconcealed satisfaction proceeded among all those present. As the fourth fork began to be formed on the horns, the tension among those assembled reached its height, since the formation of the fourth fork on the horns signified that the Reason of Beelzebub had already been perfected to the sacred Ternoonald and hence that there remained for Beelzebub only two gradations before attaining to the sacred Anklad.

“When the whole of this unusual ceremony neared its end and before all those assembled had had time to recover their self-possession from their earlier joyful agitation, there suddenly and unexpectedly appeared on the horns of Beelzebub quite independently a fifth fork of a special form known to them all.

“Thereupon all without exception, even the venerable archangel himself, fell prostrate before Beelzebub, who had now risen to his feet and stood transfigured with a mystical appearance, owing to the truly majestic horns which had arisen on his head. All fell prostrate before Beelzebub because by the fifth fork on his horns it was indicated that He had attained the Reason of the sacred Podkolad, i.e., the last gradation before the Reason of the sacred Anklad .

“The Reason of the sacred Anklad is the highest to which in general any being can attain, being the third in degree from the Absolute Reason of HIS ENDLESSNESS HIMSELF.”

In regards to the levels of individual development as portrayed by the growth of Beelzebub’s horns, beyond the three lower levels of Reason, Gurdjieff adds the several categories of Being as the steps through which humans may eventually proceed: “Reason of Astral Body” (Ternoonald), “Reason of Spiritual Body” (Podkolad), “Reason of God” (Anklad). The highest level he calls “Common Endless Creator, Our Endless Endlessness-all Quarters Maintainer” which we equate with the Egyptian Ra and which Plato presents as the Sun itself.

It is through his description of prongs sprouting on the head of Beelzebub that we find a terminology that allows an equivalence to be drawn between his perception and those of others that we study in this book. These all too difficult to recognize “higher” levels presented allegorically in Gurdjieff’s book as growth of horns on the head of Beelzebub make it easy for the casual reader to laugh off this scene as a humorous, useless fiction. We argue that it is no more fanciful than the human-headed birds and sphinx of the Ancient Egyptians or chained observers in Plato’s cave. To speak about the more-than-physical, creative irrational world has always been a challenge.

Gurdjieff’s writing provides insights into how we may be able capitalize on what he calls our “Conscious Labours and Intentional Suffering” to enable us to recognize the potentially higher states that he suggests are true possibilities for us. He points out that such higher states require a deliberate balancing of the characteristics that are revealed in our ordinary lives so that with additional understanding of ourselves we can gradually learn to pass from these primitive natural levels of reactivity to the higher levels that appear only with conscious balanced efforts; revealed with phenomena that only appear when these lower stages act together.

Coming as it does towards the end of the long tale of Beelzebub’s travels it is easy for the reader to fall “asleep” and get lost in the amusement of the image of horns growing on the head of a superior being. To Gurdjieff’s credit the “bone is indeed well buried” in these distracting images. Our purpose for inserting the line of Gurdjieff’s “Reasons” into Table 2 is to emphasize that this unusual image of sprouting horns may represent the most important guidance for us of what is in his book, and what we need to know. As we see in Table 2 his “Reasons” can be aligned with the major thoughts of other traditions. His lack of detail on the characteristics of these higher Reasons is also consistent with our ordinary understanding that they are very rarely realized but are ultimately personal and important in our recognition.

Are we, at this point in our study, being invited once again for some specific reason to seriously re-consider this assumed unity of being and the parts of which it is composed? We are accustomed to the idea of there being three basic functions of our natures that he calls “bodies”: (our bodies, our emotions, and our minds), but there seems to be something more suggested here. We customarily consider that these three independent functions work together in a recognizable harmony of operation towards a particular purpose. But one of the apparently main purposes of the life teachings of Gurdjieff was to encourage us to seriously question this supposed unity for ourselves. In examining this Table we therefore remind our readers that we need to take the question of this unity seriously. We invite our readers to do the same, perhaps being better able to keep this qualification of our sometimes-erratic functioning in mind when we are specifically pointed in that direction. How then are we to proceed?

By such methods Gurdjieff utilized many elements of every-day life to illustrate particular phenomena that are not otherwise familiar to us. As an example we point out that in this description he utilized quite specific esoteric influences on us that are not usual during our daily activities. We regard his utilization of an almost automatic action of the three notes of the octave sequences in this way. While the 3-note sequence may be familiar to singers, we need to appreciate how it may, without our intention, induce or help hold particular moods in us.

Over his lifetime Gurdjieff developed a method for awakening out of our daily sleep so as to ascend from it to a higher level of being alive to oneself, and through that to live a more real human life. In addition to the books that he prepared for publication, his pupils have since compiled others, including a volume entitled “Views from the Real World: Early Talks of Gurdjieff as Recollected by his Pupils[18]”. Additional works have also appeared, one of particular note based on discussions led and reported by Madame Jean de Salzmann, who spent much of her life attending Gurdjieff’s activities. She published works of her own, based on his leadership, but after his death. Notable among them is the collection of essays comprising a Book entitled, “The Reality of Being. The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff.”[19]

While Gurdjieff deliberately chose the new and unfamiliar imagery to convey much of what he intended his readers to understand, it can be seen to be in keeping with other great traditions concerning our striving for a more complete existence in this world, our creative irrational.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Gurdjieff

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Gurdjieff

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenia

[4] Churton, T. 2017. Deconstructing Gurdjieff Biography of a Spiritual Magician. Inner Traditions. Vermont.

[5] Gurdjieff, G.I. 1950. Beelzebub’s Tales To His Grandson. All and Everything Third Series. Penguin Putnam Inc. 375 Hudson St., New York.

[6] https://www.amazon.com/Meetings-Remarkable-Men-G-Gurdjieff/dp/1578988934/

[7] https://www.amazon.com/Life-Real-Only-Then-When/dp/0140195858/

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Octave

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meetings_with_Remarkable_Men

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_Search_of_the_Miraculous

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fakir

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monk

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yogi

[14] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tahra-Bey

[15] Brunton, P. 2007. A Search in Secret Egypt. Larson Publications. Burdett, New York.

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fourth_Way

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beelzebub%27s_Tales_to_His_Grandson

[18] Gurdjieff, Views from the Real World 1973. Early talks in Moscow, Essentuki, Tiflis,, Berlin, London, Paris, New York and Chicago As Recollected by his Pupils. With a Forward by Jeanne de Salzmann. E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc. New York.

[19] de Salzman, J. 2010. The Reality of Being. The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff. Shambala

April 8, 2020

Chapter 6: The Greek Expression of the Creative Irrational

The Ancient Greeks followed the Ancient Egyptians in the final centuries of the Egyptian culture. Between 728 and 525 BCE the glory of Ancient Egypt was fading with the waves of invasions by the Nubians, Assyrians and Persians. It was during this period that the Ancient Greeks were learning at the feet of the remaining Egyptian teachers. Both early Greek philosophers ,Thales of Miletus[1] (circa 624 – c. 546 BCE) and Solon[2] (circa 638 – c. 558 BCE), journeyed to Egypt and met with Pharaohs, and were trained by priests. Thales was considered by Aristotle as the first philosopher and the later was noted by Plato as the source of the tales of the sinking of Atlantis. It should not then surprise us to find a comparable spectrum of spirituality in the Greek tradition.

Comparable to the Egyptians, the approaches of Parmenides, Plato and Plotinus provide us with a means for exploring the underlying human expression of our creative irrational and its striving towards spirituality at the highest levels.

Parmenides – As far as longing can reach

We begin with the lessons of the ancient Greek teacher Parmenides (circa 550 BCE) as presented by Kingsley[3]. His presentation helps us trace the possibilities for a new path to higher development. In particular we note that Kingsley’s insights into the writings of Parmenides show a link from the practices of the Ancient Egyptians into what the Greeks saw as the attraction to the higher.

Parmenides[4] was an early philosopher teaching in the town of Velia in Southern Italy. He was apparently an early priest of the worship of Apollo. While only a small amount of his original works has survived, one of his major works, entitled “On Nature” has survived. In this writing he provides a metaphor for the journeys to the edge of existence, the edge of our creative irrational. The first of the three sections of “On Nature” describes the undertaking of an initially spiritual journey from Parmenides’ ordinary life to the edges of this world to learn the great mysteries of life. He issummoned by the “Daughters of the Sun”.

We quote:

“In short, the Daughters of the Sun have come along to fetch him from the world of the living and take him right back to where they belong. This is no journey from confusion to clarity; from darkness into light. On the contrary, the journey Parmenides is describing is exactly the opposite. He is travelling straight into the ultimate night that no human being could possibly survive without divine protection. He is being taken to the heart of the underworld, the world of the dead.[5]”

So what does Parmenides, an early Ancient Greek with Phocaean heritage, have to contribute to our understanding of the purpose and drive behind the human creative irrational? What would make Parmenides succumb to this exceptional journey to the “edges of existence”? Kingsley portrays his motivation as originating from “longing”. To quote Kingsley again:

“The mares that carry me as far as longing can reach.”[6]

Parmenides is being dragged along by the power of allegorical horses at breakneck speed. This longing is no ordinary longing. It is not the rational individual ephemeral desires, appetites and wants of food, shelter and sex. His longing cannot be any stronger. It is almost as if this longing is insatiable; that it seems beyond reach. It is core to his Being. Although this longing is personal to Parmenides, it appears of exceptional and unusual scale to us all.

A little later Parmenides’ poem states:

“For it is no hard fate that sent you travelling this road - so far away from the beaten track of humans - but Rightness, and Justice.”

This introduces the necessary balance between the high-level internal longing on the part of Parmenides and the external influences of higher morals. Rightness and Justice have put him on this extraordinary journey. They are not personal. They are basic properties of the World that are beyond the ownership of any particular individual. So his journey is the result of both an exceptional personal longing and one that is combined with the more-than-merely personal higher forces at work in him.

The creative irrational pull that draws him is a central theme of the poem. But there is another aspect of his journey that cannot be missed. After he arrives in the presence of the goddess she provides him with insights. But there is an additional requirement paced on him. He is directed to “carry it away”. It is not sufficient that he receives the higher knowledge, but he is compelled to return to life with this knowledge. It becomes evident that this journey of his is not a one-way street. It seems that the return is an integral part of the motivation for the journey. There is a need for this knowledge to be delivered by Parmenides back to those who have not, or cannot, make the journey. There is something beyond the individual that is being satisfied by the experience.

So in Kingsley’s treatment of Parmenides we see the key elements of our personal creative irrational that includes an extreme internal personal longing as well as an external, more-than-merely personal influence to continue our existence beyond the rational biological, physical requirements.

The Classic Greek Metaphor of the Spirituality Spectrum: The Allegory of the Cave

The difficulties of simultaneously understanding different states within ourselves, ones that constitute our more usual situation, and others that are transformed states that we know only in special moments, comprise the main theme of “The Allegory of the Cave”, contained in Plato's writing called “The Republic[7]”. This classic allegory is an extended metaphor; a comparative image intended to convey a deeper level of understanding.

The second line of Table 2 describes in our own wording the description of the various stages in development of a human being according to the famous portrayal by Plato of his concept of the development of an individual’s movement from darkness into the bright light of the sun, as it is described in his essay the “Allegory of the Cave”. Plato, the archetypal classical Greek philosopher, thinker and writer circa 400 BCE, continues to be highly revered in the modern Western World for his contribution to our present day worldview. One of Plato’s it greatest works deals with levels of human existence. This “Allegory of the Cave” makes no sense if thought of literally in a physical world. It points to the need to see the levels of Being that are required for living consciously.

As we can see from the first two lines in Table 2 there are strong similarities between Plato’s description and that of the much earlier Ancient Egyptian. They both contain descriptions of both the rational biological and physical bodies and the more-than-merely personal levels of higher existence. In keeping with our definition of the creative irrational as being “beyond reason”, they are both dealing with the creative irrational using their preferred language and images.

Plato's mental construct in the Allegory begins with his presentation of the lowest level of human existence. He likens it to that of prisoners who from earliest childhood have been chained so that they can only look at the back of a long cave. They sit in a row and in only one position, unable to turn their heads; thus constrained to look only ahead of them at shadows cast on the back wall of the cave by the light of a fire burning behind them. They see only the shadow images, cast from what moves behind them, between them and the fire, images that appear to move along the wall. If someone carried implements behind them between them and the light, they would see only shadows of the carriers and the implements. And if sounds were heard, they would think that they came from the shadow images. These images would be the whole perceptual basis for their concept of what is real.

Plato then asks that we picture what would happen if one of the prisoners was freed and compelled to stand up and turn around to look at the light of the fire. He would suffer pain at gazing directly at it, and be so dazzled that he could scarcely discern the objects that had cast the shadows, and which made the sounds.

The story continues:

"What do you suppose would be his answer if someone told him that what he had seen before was all a cheat and an illusion, but that now, being nearer to reality and turned toward more real things, he saw more truly? And if also one should point out to him each of the passing objects and constrain him by questions to say what it is, do you not think that he would be at a loss and that he would regard what he formerly saw as more real than the things now pointed out to him?...

"...and if someone should drag him by force up the ascent ... into the light of the sun, do you not think that he would find it painful,...and when he came out into the light that his eyes would be filled with its beams so that he would not be able to see even one of the things that we call real?...

"There would be need of habituation, ... to be able to see the things higher up. At first he would most easily discern the shadows, ... later the things themselves, and from that he would go on to contemplate the appearances in the heavens and heaven itself .... And so finally, he would be able to look upon the sun itself and see its true nature, not by reflections in water or phantasms of it in an alien setting, but in and by itself in its own place. [8] "

By using such relatable physical items such as “cave”, “shadows”, “fire” and “Sun”, the story presents the very abstract, intangible concepts in a spectrum of spirituality from the lower physical to the highest level of being. The Allegory captures not only the various levels of spirituality but also the key point that progress up the spectrum involves great effort and pain for the person striving for the higher levels. The allegory also points out that the climb from the back of the cave into full daylight might take a rather long time and a great deal of effort. The allegory refers specifically to the need for what it calls a period of habituation for acclimating ourselves to what is encountered on the climb. This is consistent with the many statements in the Pyramid Texts that urge the central figure to rise, to continue on, to do what is difficult for an ordinary person – such as fly. Both sets of text make no secret of the difficulty in reaching the higher levels of experience. The texts speaks of the fact that in one state it is very difficult to appreciate what might be encountered in the others; the very objects accessible to sight are seen entirely differently in the different situations, so differently that experience in one state is insufficient preparation for understanding what is seen in others. To reach a "higher" state from that which determines our present outlook clearly requires a considerable effort of understanding and tolerance, both towards ourselves and towards others with whom we may be related.

The allegory states in several instances that movement from the dark to the light is both painful and dazzling, so much so that it is questionable if it could be undertaken voluntarily by ordinary man. Plato suggests that the act could be undertaken only under duress or being forced by some outside power, perhaps an event or condition that might lead us to recognize an inner sense of great need.

It is even suggested that if the possibilities were introduced without this help from our circumstances, and if we were able to apprehend it under ordinary conditions we would rather kill the urge than obey it. This follows the situation of Parmenides being drawn by forces both internal and external. Such dramatic language is not easy to appreciate until one encounters the resistance in oneself, such as our resistance to a re-interpretation of symbols with which we have been raised or have lived with for a long time.

But the allegory doesn’t stop with the scenario of the person appreciating the highest levels of existence as represented by the image of the Sun. Plato goes on to discuss what would happen to the same person brought down again into the cave among the former fellow prisoners. What had been experienced in the bright light of the full strength of the sun would now make it impossible for the person to see and identify the shadows as well those who remained in the cave. The person would be laughed at and counted as one who had lost their sight if the person tried to tell them about it, and they would all conclude that it was clearly not worth even to attempt such folly in an ascent. In fact, they would actively resist exposure to the new interpretations. As Plato puts it, "If it were possible to lay hands on and to kill the man who tried to release them and lead them up, would they not kill him?" What is more, the person’s situation, having returned to their former world of illusion would be worse, not better.

"Do you think it at all strange if a man returning from divine contemplations to the petty miseries of men cuts a sorry figure and appears most ridiculous, if, while still blinking through the gloom, and before he has become sufficiently accustomed to the environing darkness, he is compelled in courtrooms or elsewhere to contend about the shadows of justice or the images that cast the shadows and to wrangle in debate about the notions of these things in the minds of those who have never seen justice itself?

"A sensible man would remember that there are two distinct disturbances of the eyes arising from two causes, according as the shift is from light to darkness or from darkness to light, and, believing that the same thing happens to the soul too, whenever he saw a soul perturbed and unable to discern something, he would not laugh unthinkingly, but would observe whether coming from a brighter life its vision was obscured by the unfamiliar darkness, or whether the passage from the deeper dark of ignorance into the more luminous world and the greater brightness had dazzled his vision. And so he would deem the one happy in its experience and way of life and pity the other, and if it pleased him to laugh at it, his laughter would be less laughable than that at the expense of the soul that had come down from the light above.... [9] "

One of the principal attractions of Plato’s work in the current context is that it uses images from an everyday level of experience to cast additional light on states that are removed but that can be recognized in our ordinary life. It thus provides important further perspective on what is needed to bridge the gap that separates our ordinary life from other levels of understanding. Plato states in the very beginning of this dialogue that in developing his ideas he is not intending to describe man's situation in the exterior world, so much as using the imagery of social and political situations to enlighten our understanding of what takes place within us (emphasis added), when we are able to pay attention. The imagery captures much of what we can discern about our confused, lack of understanding between the vastly different states within ourselves - see Row 2 in Table 2.

In keeping with the theme of the creative irrational being “beyond reason”, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave presents us with a description of human life that is far beyond food, shelter and procreation. He presents a model of human existence that includes higher levels, each requiring effort and habituation to appreciate as well as a necessary return from full experience to assist our fellow “prisoners”. Perhaps because of the great difficulty of seeing how these infrequent, hence unfamiliar insights depend on us, many religions have implied that they arise outside of us, in a consciousness that exists independently of us. In such a case insights might only be activated in special conditions of need, such as we presented in Chapter 1 regarding the car accident or the encounter with the aged “Mi’kmaw” woman. Perhaps it is possible from comparable states of prayer. We do not wish here to enter into a debate on the impartiality or reality of religious beliefs. However, if we treat all such statements as symbolic in the same sense that the allegory of the cave is told, we might be able to agree that images of external influences are speaking of externality in the sense that they are external to our exoteric sense of reality. For instance who or what would force the prisoner to break their shackles and turn to the burning bright light of the fire at the back of the cave?

But is the same true for our esoteric parts? Such interpretation is consistent with the theory that they arise through an innate commonality of our individual unconscious. We can at least conclude that we seem to harbour within us a knowledge of influences and functions that are properly the characteristics of another level of being. For our level, however, they are the "secrets" told to initiates.

What matters most at the moment is to recognize that because of the way new understanding arises and works in us, certain ancient, traditional stories can be seen to have been deliberately intended to use metaphor and allegory to appeal to personal experience as the primary means of conveying the meanings of questions of quality and value. In this way, our new understandings may often seem to be a rediscovery of what has long been known. The insights provided by the ancient stories can nevertheless be seen as in some way essential to the continued development of the sense of coherence and unity that we individually seek. They contain influences that do not appear under the ordinary processes of learning in a context of an orderly elaboration of knowledge of external things. The sense that there is a direction towards a higher level of values in civilization, a change in level that might also be likened to our wish for objectivity, seems to depend on the existence within us of this common capacity to use characteristics to discriminate between levels of comprehension. It appears as a mode of knowing that we learn about in special circumstances and that may be evoked in metaphor.

Whether we accept the later views of Philo who thought that only a select few humans can attain the higher levels of connection with the divine[10] or the view of Saint Paul that all may reach the kingdom of Heaven, there is certainly agreement of the existence of higher spiritual levels in the spirituality spectrum.

So we are dealing with a sphere of human interest that is not well communicated by common language. Throughout the history of human activities we have had to resort to metaphor and allegory to try and address our higher interest. Of course the greatest difficulty is that the lesson may be taken literally – missing the whole point of the artistic creation. As might be expected from the Egyptian lineage of Plato’s ideas, it is relatively easy for us to draw equivalence between the various levels found in each of the two traditions (Table 2). Each culture presents their understanding in different ways. It may also be expected that the representation of levels found in the Classic Greek version seems more approachable. The symbolism of fire, shadow and the sun connects more easily with our modern sensitivities than human-headed birds, disembodied hearts on scales and crocodile-headed gods. Yet the insights are the same: there is more to us than we normally attend to.

Intellectual Principle – Plotinus

Plotinus, circa 200 CE, was a Neo-Platonic philosopher writing about 800 years after Parmenides[11]. His major works entitled the “Enneads”[12] developed ideas of levels of existence that included the soul (Psuchē), the Intellectual Principle (Nous) and the highest level of the One (Monad). The third line of Table 2 names the levels according to the Plotinus. While his philosophy is linked to Plato, he is likely to have been influenced by Philo and the early Christian authors[13].

Plotinus believed that, “Everything leads to the One”. The One is the indivisible “All” containing the foundation of everything. Below the One he identified a number of levels of existence showing increasing differentiation as they occur lower in the scale. The key challenge of life according to Plotinus is to find within the highest existence, the Nous, that has been variously translated from Greek as the Intellectual Principle, Divine Mind, Logos or Order. Although Plotinus’ writings are not as widely recognized today as Plato’s, they have greatly influenced many of the Western World’s religions and Christianity in particular[14].

In light of our discussions regarding the different levels of phenomena in our daily existence, and the creative irrationality in seeing beyond our common experiences in our inner world, we can with effort still approach the terminology of Plato or of Plotinus. Thus, for example, perhaps without directly experiencing what the ancients called a Soul, or being able to identify exactly what was meant by Spirit, we are still in a position to recognize in these expressions hierarchies of phenomena in the inner world that do not differ in principle from levels in the hierarchy of phenomena described in exoteric models. In this way we can, for example, be prepared to appreciate the intent of Plotinus’ terminology. We can understand such terms to describe what he has detected as the levels or stages of ascent in inner spiritual transformation, rather than immediately dismissing them as either personal or “merely” metaphysical abstractions. By realizing the analogy with our own models of exoteric hierarchical structures, we can begin to contemplate the possibility of structures in the inner world that, while inaccessible to us in our ordinary conditions, are nevertheless phenomena that can be appreciated by us from their description by Plotinus.

In his presentation the Nous is the God within us that is simply a part of the indivisible, ever-present Monad. Plotinus speaks of the essential attraction of that part of us, the Nous, towards the all-present Monad. In his words:

“Any that have seen know what I have in mind: the soul takes another life as it draws nearer and nearer to God and gains participation in Him; thus restored it feels that the dispenser of true life is There to see, that now we have nothing to look for but, far otherwise, that we must put aside all else and rest in This alone, This becomes, This alone, all the earthly environment done away, in haste to be free, impatient of any bond holding us to the baser, so that with our being entire we may cling about This, no part in us remaining but through it we have touch with God. Thus we have all the vision that may be of Him and of ourselves; but it is of a self-wrought to splendour, brimmed with the Intellectual light, become that very light, pure, buoyant, unburdened, raised to Godhood, better, knowing its Godhood, all aflame then – but crushed out once more if it should take up the discarded burden.

“But how comes the soul not to keep that ground:

“Because it has not yet escaped wholly: but there will be the time of scission unbroken, the self hindered no longer by any hindrance of body.” [15]

This sounds very similar to the experience that Philo witnessed and reported.

Plotinus describes the Monad as a non-duality state that permeates everything. Its emanations establish all lower levels of existence. These ideas were developed a hundred years before Constantine formulated Christian beliefs of an omnipresent God[16]. Christianity later corrupted the concept of an all-present God into a concept of a separate, identifiable father figure that oversees everthing. In the Renaissance, 14th to 17th century CE, this “ever-present” God even became represented as an external old man sitting on a cloud surveying a physical world (Figure 28).

![Figure 28. An image of the “Creation of Adam” painting by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City [17] .](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1586429385i/29260151._SX540_.png)

Figure 28. An image of the “Creation of Adam” painting by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City [17] .

While recognizing that the pictorial representation in Figure 28 is a piece of art created to convey complex higher level metaphysical thoughts to a general audience, we must also see that it unintentionally actually presents a vision of a separation into many parts – human from God, sky from earth, higher from lower. Quite a distraction from Plotinus’ urge to find the unity in our being that represents the Monad.

So what does Plotinus have to offer our search for the creative irrational in Greek philosopy? He specifically refers to our true nature as the soul or Intellectual-Principle that is a shared aspect of God. He makes an awkward analogy with the “love of a daughter for a noble father” who falls as a result of being lured by a mortal love. He says, “But one day coming to hate her shame, she puts away the evil of earth, once more seeks the father, and finds her peace.”[18] We call this awkward because it still falls into depending on the duality of two separate and independent beings, father and daughter. Duality is a philosophical position that it is not easy for us to avoid. In the Western world we seem consumed by thoughts of good versus bad, you versus me, etc.

Indeed Plotinus frequently espouses “love” as the driving force that underlies our desire for levels above the physical ordinary life. Elsewhere he expresses the shared components among God and ourselves as individuals. He states:

“So it is with the individual souls; the appetite for the divine Intellect urges them to return to their source.” [19]

And

“It looks towards its higher and has intellection; towards itself and orders, administers, governs its lower.” [20]

The sharing of the aspects of God in ourselves leads us to a sense of loss in our ordinary lives and a desire to get back into contact with the higher. According to Plotinus, it is a shared love of a singularity that motivates us. Our preparation for this reconnection requires us to become disassociated from the distractions of our ordinary lives. The reconnection requires quiet preparation and waiting as well as the occurrence of God showing himself like an “eye waits on the rising of the sun”[21].

It is important to point out that Plotinus also recognizes our inability to stay connected with the higher. He says:

“Many times it has happened: lifted out of the body into myself; becoming external to all other things and self-encentred; beholding a marvelous beauty; then, more than ever, assured of community with the loftiest order; enacting the noblest life, acquiring identity with the divine; stationing within It by having attained that activity; poised above whatsoever within the Intellectual is less than the Supreme: yet, there comes the moment of descent from intellection to reasoning, and after that sojourn in the divine, I ask myself how it happens that I can now be descending, and how did the Soul ever enter into my body, the Soul which, even within the body, is the high thing it has shown itself to be.”[22]

And from a translation by Hadot, Plotinus states:

“Often I reawaken from my body to myself: I come to be outside other things, and inside myself. What an extraordinarily wonderful beauty I then see! It is then, above all, that I believe I belong to the greater portion. I then realize the best form of life; I become at one with the Divine, and I establish myself in it. Once I reach this supreme activity, I establish myself above every other spiritual entity. After this repose in the Divine, however, when I come back down from intuition into rational thought, then I wonder: How is it ever possible that I should come down now, and how was it ever possible that my soul has come to be within my body, even though she is the kind of being that she has just revealed herself to be, when she appeared as she is in herself, although she is still within my body? [23] ”

The attitudes developed in contemplating such testimonials can help us understand the intent of searches into the phenomena of the inner world by allowing the creation within us of a sympathetic impulse towards the sincerity of the messages they have undertaken to convey to our generations. Plotinus recognizes the need to connect with the higher as well as the inevitable return to the ordinary.

He makes the point that the two states, the higher and lower, are naturally occurring and can be realized according to their circumstances:

“Souls that take this way have place in both spheres, living of necessity the life there and the life here by turns, the upper life reigning in those able to consort more continuously with the divine Intellect, the lower dominant where character or circumstances are less favourable.”

Critical to the distinction between Plotinian thought and the later Christian thought is the sense of who has access to the higher. In this quote the phrase “able to consort” strongly suggests that Plotinus saw a distinction between individuals who were prepared and able to access the higher and those who did not or could not access the higher. This is quite different from the modern Christian view espoused by Saint Paul that everyone who undergoes the process of baptism can expect access to the Kingdom of Heaven[24]. This distinction between those who expended significant effort and work and those who gain “entry” into heaven through a short, once in a lifetime ceremony certainly would have been seen and appreciated by Nietzsche.

So to summarize, Plotinus saw in us a portion of the unified God that longed to extend beyond our physical body and return to a communion with the Higher. Individuals are required to see themselves, develop a calm, quiet waiting posture and be prepared for when the unity of God presents itself. The answer to the question of “why awaken?” found in Plotinus’ teaching is that we inevitably hold a share of the indivisible, ever-present Monad within us. With time, effort and patience, our work in our ordinary life opens up the possibility of seeing this part of the Monad in ourselves and calls us out of our limited, unsatisfactory lives to the higher. Returning to the quote that we have presented in the “Introduction” of this book, he spoke of the attraction of ourselves to the higher with these words:

“I am striving to give back the Divine in myself to the Divine in the All”[25].

Consistency in the Creative Irrational of Greek Philosophy

The shared themes of Parmenides, Plato and Plotinus for a necessary departure and return to normal life are key. Parmenides was dragged away by “mares”, instructed by external powers and ordered to “carry it away”. In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave what constitutes our awakening involves moving from the dark to stare into the sun before returning into the cave. He explicitly addresses the need and the challenges that a returnee faces upon descending back into the cave after acclimating to the bright light of the sun. The “Allegory of the Cave” doesn’t deal much with the reasons why a person would go through the pain and suffering of moving up and out of the cave to look directly at the bright sun. Following that difficult challenge, he doesn’t suggest a reason for a person’s actions in leaving the sun behind and returning into the depths of the cave in an attempt to unshackle those remaining in the shadows. But both the exit and the return seem essential parts of the process. Finally in our presentation Plotinus, in this same lineage of thought, refers to awe of experiencing Monad and the inability of the individual to maintain such a connection. One must inevitably return to “real” life. The distancing and return to normal life seems to be a part of a completing process in a full cycle of reaching for Being and then returning again to one’s usual existence. Whereas there appears to be a deep-seated longing required for an individual to strive for higher consciousness, the return in our long-term personal development is also required by these philosophers as being obligatory. The whole concept of such movements highlights the creative irrational of such great and influential thoughts in the development of Western culture.

Although we present this creative irrational as something intrinsically human, it is obvious that its strength varies greatly and its full potential is only ever realized in a very limited number of individuals. It is not clear from the Greek writings whether they were addressing something realized by a few select dedicated individuals or all humans. As reported by Plotinus, the difficult and fleeting ultimate goal of the creative irrational in connecting with the “ever present” occurs rarely and requires individual preparation and work to become open to the opportunities when they present themselves. Using a Christian phrase it is said that, “many are called but few are chosen.” Thus we do not present the creative irrational as a recipe for the attainment of higher consciousness, but as a potential work aid to help focus our attention on the internal more-than-personal movements within us.

In summary, we appreciate from the points of view presented by Parmenides, Plato and Plotinus that they were struggling to provide insights into a process of individual development that while clearly irrational, is incredibly powerful in forming a human connection with the more-than-merely personal. All are obviously dealing with life beyond rational normal day-to-day existence towards the higher levels of existence and Being. All of them allude to a natural process of longing to be reunited with something that is more-than-merely-personal, something that is more than ordinary for most of us as individuals. Plotinus specifically points out that we are a part of something that is all encompassing in our world. The higher levels draw our interest in rejoining the higher. Parmenides made the point that there is great reward in experiencing the life at the edge of existence. But his view is that our initial encounters with the higher are unsustainable in our regular being. The creative irrational is a part of our existence; a longing for something that is beyond our ordinary lives, something more-than-merely personal in our consciousness.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thales_of_Miletus

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solon

[3] Kingsley, P. 2003. Reality. The Golden Sufi Centre Publishing. Inverness, California.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parmenides

[5] Kingsley, P. 2003. Reality. The Golden Sufi Centre Publishing. Inverness California.

[6] Kingsley, P. 2003. Reality. The Golden Sufi Centre Publishing. Inverness California.

[7] Hamilton E. and H. Cairns. 1980. Plato, The Collected Dialogues, including the letters. Bollingen Series LXXI. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1743 pp.

[8] Hamilton E. and H. Cairns. 1980. Plato, The Collected Dialogues, including the letters. Bollingen Series LXXI. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1743 pp.

[9] Hamilton E. and H. Cairns. 1980. Plato, The Collected Dialogues, including the letters. Bollingen Series LXXI. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1743 pp.

[10] Sandmel, S. 1979. Philo of Alexandra: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. New York.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plotinus

[12] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philo

[14] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plotinus

[15] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. IV.9 (9-10)

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constantine_the_Great_and_Christianity

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Creation_of_Adam

[18] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. VI.9.

[19] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. IV.8.4.

[20] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. IV.8.3.

[21] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. V.5.5.

[22] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. IV.8.1.

[23] Hadot, P. 1993. Plotinus or The Simplicity of Vision. M. Chase (trans.). Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_the_Apostle - Basic_message

[25] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications. Page 2.

March 28, 2020

Chapter 4: The Spirituality Spectrum

For hundreds of thousands of years modern humans lived, reproduced, evolved and distinguished themselves from the other hominin species. They interbred with Neanderthals, Denisovan and likely other hominins. Like other hominins they created art and buried their dead. As we saw in the last chapter, only Homo sapiens began pursuing creative irrational activities, most notably the creation of megalithic structures, circa 12,000 BCE. The early megalithic constructions most likely were attempts to capture impulses higher than those arising from hunger or fear. The ubiquitous alignments of their stone structures with celestial markers, whether sunrise, sunset, the Milky Way and or star clusters strongly suggest their connections with the more-than-merely personal aspects of their lives. They were definitely working to receive and transmit the creative irrational in their lives.

It was not for another 7,000 years after the beginning of the Göbekli Tepe constructions that humans developed a new method of expressing themselves. The cultures of the Sumerians and Egyptians circa 3,000 BCE establish writing. An expression that we take for granted in our modern day societies providing the societies with further opportunity to express their higher complex thoughts. As a result, the writing that we have found provides much greater insights into their motivations and worldviews. Indeed while these two advanced cultures produced megalithic architecture and art it is through writing that they were able to provide metaphor and allegory to address the more-than-merely personal aspects of life. As our discussion moves from the pre-literate period of human development to a time when human consciousness was recorded in words, phrases and literature we find evidence of more than day-to-day concerns. We can recognize a continuing development of interest in the higher, creative irrational, leading toward spiritual, aspects of human existence.Although time and culture separate us from the scribes there is a shared commonality that allows us to still appreciate and learn from their efforts[1].

Between the two extremes of human existence from purely physical to that of our highest spiritual expressions there are various levels of existence available to humans. We capture this range of existence in what we see as the “spirituality spectrum”. It is an effort to connect our most mundane, ordinary, day-to-day existence, associated primarily with our rational animal sides, with the highest spiritual expression. The spirituality spectrum as presented in Table 2attempts to capture our rational aspects in the left-hand side while the highest levels of human existence are on the right-hand side.

Table 2. Spirituality Spectrum showing a comparison of a selection of classifications of the levels of human consciousness relating to the irrational and spiritual.

We begin the Table with the oldest description of the various levels of human existence. It comes from the Ancient Egyptians initially in the Pyramid Texts circa 2,500 BCE and elsewhere in their literature and art. They first captured this range of human existence in their presentation of the various “human bodies”. Our interpretation of the Ancient Egyptian bodies is presented in the first row of Table 2 from its purely physical body form on the left, through to the existence in Ra on the right. The following rows in the Table represents a “rough” mapping of the various stages of Being as conceived of by cultures and individuals onto the structure provided by the Ancient Egyptians. We find very similar representations in a selection of later traditions from the ancient Greeks to the 20th century teacher Gurdjieff and the psychologist Jung. This presents a gross summary of the results from the many approaches followed throughout the history of human culture. In the remainder of this book we explore all of these interpretations of the human condition in more detail. The reader needs to be aware that there can be no exact equivalence drawn among the different traditions – some traditions that extend over millennia. Over such a period human consciousness and individual Being are likely to have been experienced in so many different personal ways as to defy simple classification. Yet, we need to recognize that humans have been examining and attempting to express such thoughts since the very beginning of modern human societies. As we see it, these are just different formulations of a worldview that is ultimately irrational and strongly linked to the spiritual aspects of humanity. As a result, these few examples help us to recognize expressions of the creative irrational in many traditions that have evolved over the past 5,000 years.

[1] Dickie, L.M. and P.R. Boudreau. 2015. Awakening Higher Consciousness: Guidance from Ancient Egypt and Sumer. Inner Traditions, Vt.

[2] MacKenna, S. 1992. Plotinus The Enneads. Larson Publications

[3] http://www.gurdjieff.justwizard.com/all&ever.html & http://ae.gurdjieff.org.gr/chapters/en50/chapter47.htm

March 20, 2020

Chapter 2: The Rational in Non-Humans

In our effort to distinguish humans from other biological organisms in terms of irrationality and spirituality it is critical to establish a baseline for comparison. While it is difficult to discuss spirituality in humans, it makes absolutely no sense to project measures of spirituality on other animals. But one can examine the extent to which their actions appear rational or not. So we begin our exploration of the importance of the human irrationality by looking at its opposite – the rational. That is, we can to establish what other general animal behavior is like. Is it primarily rational or irrational? Specifically we need to see how animals behave in their routine lives.

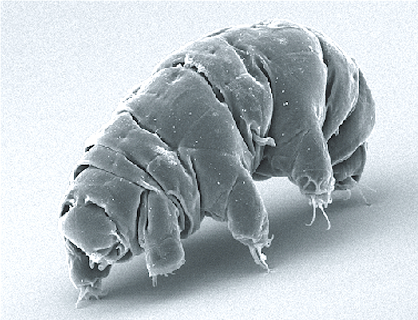

To do this we start with a definition of the rational objectives of all animal species as being concerned with food, shelter, procreation and immediate pleasures. The success of any species is tied to these four necessary aspects of life. They are what will ensure that their genes will survive to be passed on to their offspring. Although across the animal kingdom the actual requirements for a species survival are incredibly diverse, they all need to be achieved within the lifetime of the individuals of the species. While the requirements for one species’ existence may need to be found within a very narrow range of environmental conditions, such as giant pandas that survive only in bamboo forests, in other species, such as the tardigard (Figure 4), that can actually survive for periods of time in the harsh environments such as in the vacuum of outer space[1].

Figure 4. Tardigrade that measures 0.5 mm / 0.02 inches and is one of the hardiest animals known. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tardigrade ).

For our examination we focus on higher order animals and their rational behavior patterns. They meet immediate needs and result in tangible benefits. We look here at a select number of examples of non-human animals that represent the broader rational approach to to meet survival requirements. In particular we explore the use of tools in animals.

Of course there are many behaviors that animals use to acquire their food. These could involve complex strategies for hunting and gathering food items. Many predators have developed complex coordinated action and social interactions for stalking and killing prey, such as can be seen with the archetypical actions of a pride of lions picking out a wildebeest on the African savanna. But in addition to highly evolved actions, many animals are known to select and modify items from their surroundings and use these items in their procurement of food[2].

We start with an example from the bird kingdom. While parrots are thought to be fairly intelligent through their well-known and amusing ability to mimic the voice of humans, in the bird world, crows, ravens and rooks better display traits indicating high intelligence in birds. Most critically this is reflected in their intelligent, ingenious use of tools. For example, ravens are known to drop walnuts in front of passing cars to get the nuts cracked and the meats made accessible. They have been observed using sticks to reach food that is beyond their grasp. They have also been observed to actually select specific objects for use in displacing water in a container to more efficiently access articles of food. This selection process can be quite complex. That is, they choose objects that meet their needs on the basis of both their size and weight (Figure 5). Another notable example of tool use by birds is that of the Egyptian vulture. It manipulates rocks with its beak to pound them onto the shell of an ostrich egg until it cracks (Figure 6).

Figure 5. The 'water displacement' tasks (pictured) were all variations of the Aesop's fable in which a thirsty crow drops stones to raise the level of water in a pitcher ( http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2590046/Crows-intelligent-CHILDREN-Study-reveals-birds-intelligence-seven-year-old.html ).

Figure 6. Juvenile Egyptian vulture breaking egg with stone ( http://www.arkive.org/egyptian-vulture/neophron-percnopterus/image-G30003.htm ).

Moving to mammals, whales and dolphins are known to be especially intelligent for their communication and learning of human-taught tricks. But they also express their abilities when it comes to acquiring food. For example, a pod of bottlenose dolphins in Australia has been seen tearing off pieces of sponge and wrapping them around their noses, apparently to prevent abrasions while they poked about the sea floor hunting for buried animals as food.

Even the strong jaws of the sea otter aren't always enough to pry open a tasty clam or oyster. That's when this charismatic marine mammal gets wise. The otter makes use of stones. They might use one on its belly as an anvil or they might uses one to pound open its mollusk meal[3].

If we consider primates, there are many examples of animals modifying objects for procuring food. Capuchin monkeys make stone knives by banging flint against the floor until the pieces are sharp. Primates also pick up or break off sticks and after some alteration stick, poke, or jab them into holes in various situations to acquire bush babies, ants, honey or other food sources. One case of such alterations of an object for purposes of getting food can be found in the Senegal chimpanzees[4]. In one reported case sticks were not only selected and stripped of their leaves, but the ends were sharpened by the chimpanzees by chewing them down to a point. Once pointed the “spears” could be jabbed into holes in trees to acquire bush babies that would otherwise have been inaccessible.

Shelter

Many higher animals are known to manipulate their environment and produce tools to enhance their use as shelter. For example, the octopus is heralded as the most intelligent non-human invertebrate on the planet. Octopuses have been observed carrying shells that can be used to protect them when threatened (Figure 7). Hermit crabs are the archetypal example of an animal that has a shelter made from materials in its environment. It also uses the shells from other species as its mobile home (Figure 8). The Blanket octopus has been known to use “tools” for shelter from attack[5]. They tear off tentacles from a jellyfish and wield them as a weapon. Both of these uses of “tools” show the application of inventive rational activity to the task of procuring shelter.

Figure 7. An octopus using a bivalve shell for its own protection ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tool_use_by_animals#In_cephalopods ).

Figure 8. Hermit crab “housed” in the shell from another species ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermit_crab ).

Nests in birds and primates provide one of the many, many examples where materials are fashioned to improve their use in life situations in very rational ways. In the world of mammals, for simplicity and ease, chimpanzees select large leaves to shelter themselves from the rain. Elephants use available sticks as back scratchers and for swatting flies making their lives more pleasant. Many animals have developed consistent methods for creating very complex, amazingly detailed constructions with minimum tolerance on the form of the final product (Figure 9). In all cases the use of the tool is clearly related to the specific, rational intent and purpose.

![Figure 9. Intricate nest construction of a weaver bird’s nest [6] .](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1584791261i/29141271._SX540_.png)

Figure 9. Intricate nest construction of a weaver bird’s nest [6] .

Procreation

All higher animals must mate to give rise to future generations that will continue the species. Of course each species has its own mating process. Whether it is the notable tail feathers of the peacock or the relatively over-sized human genitalia, successful attraction of a mate is critical to the species success[7]. But in addition to the way animals are built and how they behave, non-human animal species have also been seen to actually make use of objects to enhance their attractiveness and thus procreation success[8].

The rationality in animals for use in procreation can easily be seen in the usage by some animals of decoration for attraction. Magpies are believed to acquire shiny objects that will attract other ravens. Bearded vultures add color to their plumage by rubbing against certain soils[9].

Looking at modern human’s closest relatives bonobos and chimpanzees, they have been observed making "sponges" out of leaves and moss to suck up water and use the result for grooming, apparently resulting in increased attractiveness to mates. In wild bonobos, tool use is mainly for personal care, cleaning and social purposes. It is to be noted that in both of these primate species tool use is more predominate among the females.

Immediate Pleasures

Finally, in addition to animal’s rational use of tools for food, shelter and procreation, there are also instances of animals making use of tools for immediate pleasures and apparent amusement. While such activities border on the irrational, the results of the tools use is immediate and closely tied in time to activity. Crows actually create toys for their pleasure. Orcas kill for non-food use, possibly in relation to training and practicing their essential life skills in non-life-threatening situations. In addition to humans, a number of primate and non-primate animals have been observed to masturbate[10]. Mammals that masturbate include elephants, bats and marine mammals. In the bird world penguins masturbate. In the reptile world both turtles and lizards have been observed to carry out this kind of activity. In most of these cases other objects in their environment, such as a rock, may be made use of to help self-satisfy. We mention these examples of behavior here as evidence for the use of tools by animals that don’t immediately meet the needs of food, shelter and procreation.

Summary

All these activities can be seen as totally rational - for the specific purpose of enhancing the survival of the fittest in a direct and immediate manner. Poking for food, building shelters, and adorning nests to attract a mate all are limited activities that are widely seen in the species of interest without much individual creativity, variation or abstraction. It is impressive to see how highly evolved are the diverse behaviors of animals. But it is important to note that, as we proceed to explore human rational and irrational characteristics, that all of these activities are expressions of rationality and that it is almost ubiquitous in the animal kingdom. And as humans are ultimately biological species, they too express high levels of rationality for their survival. Our tool making is highly refined and without a doubt a function of our success in occupying almost all areas of the globe.