Janet Fisher's Blog, page 15

July 2, 2016

The TRUE Shifting Winds ~ 1: The Oregon

In the coming weeks prior to my July 16 reading and signing event at the historic Fort Vancouver site in Vancouver, Washington, I’ll be offering some background color in this new series I’m calling “The TRUE Shifting Winds.”

In the coming weeks prior to my July 16 reading and signing event at the historic Fort Vancouver site in Vancouver, Washington, I’ll be offering some background color in this new series I’m calling “The TRUE Shifting Winds.”

What sets my book The Shifting Winds apart from many historical novels of adventure and romance is the history. Yes, there’s a triangle love story, two men vying for one young woman, but there’s another triangle, two nations vying for one land. The winds of rivalry shifting back and forth in the fictional love story echo the true story of shifting winds between rivals Britain and America over the disputed Oregon Territory in the 1840s.

The Afterword of the book presents some of the actual history through which the story flows and several of the real people who populate it. In this new series of blog posts I want to delve deeper into that history. I hope these posts will enhance your reading of the book—or add perspective if you’ve already read it.

To start, let’s go way back, about 350 years before my story opens, to the events that led Europeans into this land of Oregon, at a time when the winds did shift aplenty.

River of the West

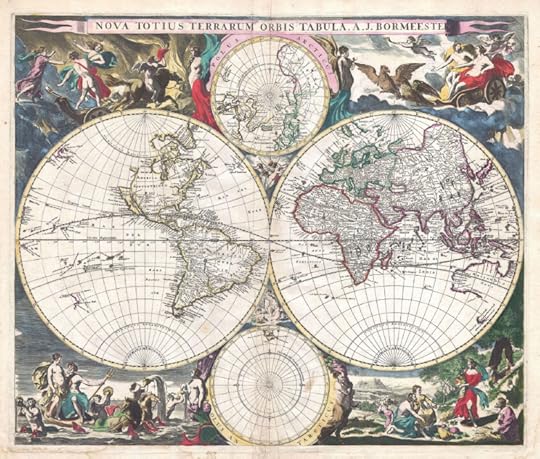

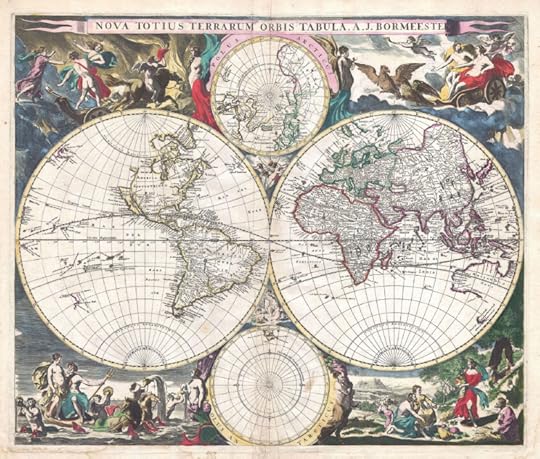

The winds of change in the true history of Oregon began to stir long before my characters walked onto the stage. The land had been settled by early tribes for thousands of years before even a whisper of its existence entered the minds of Europeans who had begun exploring the world in their improved sailing craft. Maps left no space for such a place. The coastline of what is now the state of Oregon was the last of the entire globe to be examined and charted by European navigators.

The above map provides one version of the world as envisioned in 1684 by Dutch map publisher Joachim Bormeester. From Geographicus. California is an island and the Pacific Northwest pretty much blank. But in the 1400s that whole left globe was an unknown, and a fair portion of the rest as well.

The above map provides one version of the world as envisioned in 1684 by Dutch map publisher Joachim Bormeester. From Geographicus. California is an island and the Pacific Northwest pretty much blank. But in the 1400s that whole left globe was an unknown, and a fair portion of the rest as well.

Shortly after Christopher Columbus sailed for India in 1492 and bumped into what would be called the Americas, the Catholic Pope chose to settle the rivalry of Spain and Portugal over rights of exploration by dividing the world between the two nations. He gave Spain a free field to the west and Portugal a free field to the east. And if their paths should cross, any land in the middle would be taken by right of discovery. The two nations agreed. Just like that. The whole world.

Studying the reports of Columbus, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan thought he could reach the tasty bounty of the Spice Islands on his half of the world by sailing west and finding passage through this new land Columbus happened upon. But Magellan wasn’t on good terms with his own king, and when the Portuguese king refused him he petitioned the Spanish king instead. Under the Spanish flag Magellan led a fleet of five ships in 1518 in search of a passage but found no opening until he reached the far south, where he traveled through the strait that now bears his name and came around the Horn into new waters. Having just sailed through stormy seas he found the ocean to be refreshingly calm in that moment, and he called it the Pacific Ocean. Events would turn less peaceful. He was killed in a battle in the Philippines, and his other ships ravaged, but one ship limped back to Spain, the first to circumnavigate the globe.

With more knowledge of the world, the new pope issued another decree setting a new north-south line dividing Portugal and Spain at 37 degrees west—which is why people in Brazil today speak Portuguese, instead of Spanish like their neighbors. This decree and the early voyages by Spanish navigators would later be used by Spain to claim exclusive right to the Pacific Coast of North America.

But with the religious upheavals of the Reformation, papal authority weakened and Protestant nations defied the rights given to Catholic Spain and Portugal, demanding freedom of the sea. And they didn’t hesitate to relieve the Spanish and Portuguese of their plunder.

The dashing Sir Francis Drake, hero of Britain, may have visited the Oregon Coast on one of these raids against the Spanish, but his descriptions aren’t clear enough to say. He had first caught sight of the Pacific Ocean as a young man after trudging across the Isthmus of Panama, where he’d gone to raid a Spanish settlement in 1573.

Four years later Drake sailed around the Horn for his daring adventure to pillage Spanish ships in the Pacific, capturing so much gold and other booty his ships nearly sank with the treasure. At this point no one in Europe knew anything about Oregon. The colonies of Virginia and Massachusetts had recently been formed. California was believed to be an island, and Drake may have thought he could escape the angry Spanish by doing a run around the north side of California and taking a direct shot for the Atlantic and home. But the weather was so bad he turned back south with no exploration of the land for uncertain passages. He returned to England in 1580 by going back around the Horn.

For the next 200 years the British did nothing to secure the west coast. But in 1763 after the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War in the US) Britain gained the Canadian colonies from the French and began exploring the western sea, sending out Captain James Cook of the Royal Navy to map the uncharted region.

The first known use of the name “Oregon” came in 1765 when Major Robert Rogers submitted a proposal to King George the Third, asking him to send an overland expedition to search for the elusive northwest passage believed to exist between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Roberts proposed to go from the Great Lakes to the Head of the Mississippi and from there to a “River called by the Indians Ouragon,” also called the River of the West, which flowed westward into the Pacific Ocean.

The expedition was not completed, but one of the partners in the venture, Jonathan Carver, later wrote a book about his travels in which he names the river “Oregon or River of the West,” so spelled in the published version. The name Oregon began to appear on maps to identify the river. Both Roberts and Carter claimed the name was of Indian origin, not a derivation of a French or English word as some scholars suggested. Lewis and Clark evidently found no tribes in the area using that name, and detractors point to its similarity with the French word ouragan, meaning “windstorm,” an apt reference for this river when its winds whip up. The French comingled with Native Americans throughout North America, and other tribes could have picked up on the reference. The controversy continues.

One of Jonathan Carver’s maps, above, published in the book of his travels in 1778 shows the “River of the West” on the west coast of North America. From the Library of Congress.

One of Jonathan Carver’s maps, above, published in the book of his travels in 1778 shows the “River of the West” on the west coast of North America. From the Library of Congress.

Captain Cook kept exploring by sea. On his third voyage into the Pacific he visited the Oregon Coast in hopes of finding the northwest passage, but he missed the mouth of this legendary River of the West. He had set sail for this third voyage on July 12, 1776, only a few days after the American colonists declared their independence. Just when he was hoping to benefit Europe with new discoveries, his nation was attempting to put down a revolution in one of their previous discoveries. Cook was killed on this journey in a fracas in Hawaii, but when his men returned home, word of fantastic trade possibilities leaked out.

China was offering high prices for furs from the Pacific Coast, which traders could obtain from the local tribes for simple trinkets, and the furs could be exchanged in China for tea and other Chinese goods to take to Boston for a fine profit. A Boston company was formed and sent out Captain John Kendrick and Captain Robert Gray in two vessels, the Columbia Rediviva and the Lady Washington. The fur trade era had begun.

The Spanish at this time considered the Pacific their own pond and the Pacific Coast of North America part of their domain. They were clearly suspicious of the US purpose in these waters. Kendrick and Gray, for their part, were instructed to keep the peace, but they had a few scrapes even so. During the venture Gray dared move his ship closer to the coastline than most ships and discovered many bays and inlets and promising streams. He returned to Boston in the Columbia Rediviva, the first US ship to circumnavigate the globe, and his company quickly refitted the Columbia, sending Gray back to the Pacific.

On May 11, 1792, Gray revisited a place he believed to be the mouth of a large river. He tried for days to enter the stream across a formidable bar, then finally sent a smaller craft to find a channel by sounding. When his men found what they considered a safe channel he crossed the bar into a great wide river. The local tribesmen met him with excitement, having never seen such a craft come into their waters, and Gray knew he had made a significant discovery. Was this the River of the West? The Oregon? The northwest passage? Perhaps. He named the river the Columbia after his ship.

Gray sailed upriver a ways, went aground, then drew free again, finally leaving for the sea after nine days. Sailing up the coast he approached the British Captain George Vancouver, who was also exploring the area. Gray told Vancouver about his discovery, and Vancouver sailed south along with another British vessel commanded by Lieutenant William Broughton to check out what Gray had found. Vancouver’s ship being too large to cross the bar, he dispatched Broughton with the smaller of their two vessels. Broughton sailed up the river about 120 miles, considerably farther than Gray, but Vancouver graciously credited Gray with the discovery and accepted the name Columbia.

London would later use Broughton’s journey into the river as part of their claim to the country. And when Dr. John McLoughlin chose the site for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s western headquarters he noted the location to be within this stretch sailed by his countryman Broughton, just downriver from the height of Broughton’s excursion on the river. McLoughlin named the fort for Broughton’s superior officer, Vancouver.

As the River of the West became the Columbia, the name Oregon gradually came to refer to the region surrounding this great river.

Sources:

Carey, Charles H., LLD. General History of Oregon: Through Early Statehood. Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1971.

Various websites

NEXT: Fur Traders

The TRUE Shifting Winds ~ 1

In the coming weeks prior to my July 16 reading and signing event at the historic Fort Vancouver site in Vancouver, Washington, I’ll be offering some background color in this new series I’m calling “The TRUE Shifting Winds.”

In the coming weeks prior to my July 16 reading and signing event at the historic Fort Vancouver site in Vancouver, Washington, I’ll be offering some background color in this new series I’m calling “The TRUE Shifting Winds.”

What sets my book The Shifting Winds apart from many historical novels of adventure and romance is the history. Yes, there’s a triangle love story, two men vying for one young woman, but there’s another triangle, two nations vying for one land. The winds of rivalry shifting back and forth in the fictional love story echo the true story of shifting winds between rivals Britain and America over the disputed Oregon Territory in the 1840s.

The Afterword of the book presents some of the actual history through which the story flows and several of the real people who populate it. In this new series of blog posts I want to delve deeper into that history. I hope these posts will enhance your reading of the book—or add perspective if you’ve already read it.

To start, let’s go way back, about 350 years before my story opens, to the events that led Europeans into this land of Oregon, at a time when the winds did shift aplenty.

The Oregon River

The winds of change in the true history of Oregon began to stir long before my characters walked onto the stage. The land had been settled by early tribes for thousands of years before even a whisper of its existence entered the minds of Europeans who had begun exploring the world in their improved sailing craft. Maps left no space for such a place. The coastline of what is now the state of Oregon was the last of the entire globe to be examined and charted by European navigators.

The above map provides one version of the world as envisioned in 1684 by Dutch map publisher Joachim Bormeester. California is an island and the Pacific Northwest pretty much blank. But in the 1400s that whole left globe was an unknown, and a fair portion of the rest as well.

The above map provides one version of the world as envisioned in 1684 by Dutch map publisher Joachim Bormeester. California is an island and the Pacific Northwest pretty much blank. But in the 1400s that whole left globe was an unknown, and a fair portion of the rest as well.

Shortly after Christopher Columbus sailed for India in 1492 and bumped into what would be called the Americas, the Catholic Pope chose to settle the rivalry of Spain and Portugal over rights of exploration by dividing the world between the two nations. He gave Spain a free field to the west and Portugal a free field to the east. And if their paths should cross, any land in the middle would be taken by right of discovery. The two nations agreed. Just like that. The whole world.

Studying the reports of Columbus, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan thought he could reach the tasty bounty of the Spice Islands on his half of the world by sailing west and finding passage through this new land Columbus happened upon. But Magellan wasn’t on good terms with his own king, and when the Portuguese king refused him he petitioned the Spanish king instead. Under the Spanish flag Magellan led a fleet of five ships in 1518 in search of a passage but found no opening until he reached the far south, where he traveled through the strait that now bears his name and came around the Horn into new waters. Having just sailed through stormy seas he found the ocean to be refreshingly calm in that moment, and he called it the Pacific Ocean. Events would turn less peaceful. He was killed in a battle in the Philippines, and his other ships ravaged, but one ship limped back to Spain, the first to circumnavigate the globe.

With more knowledge of the world, the new pope issued another decree setting a new north-south line dividing Portugal and Spain at 37 degrees west—which is why people in Brazil today speak Portuguese, instead of Spanish like their neighbors. This decree and the early voyages by Spanish navigators would later be used by Spain to claim exclusive right to the Pacific Coast of North America.

But with the religious upheavals of the Reformation, papal authority weakened and Protestant nations defied the rights given to Catholic Spain and Portugal, demanding freedom of the sea. And they didn’t hesitate to relieve the Spanish and Portuguese of their plunder.

The dashing Sir Francis Drake, hero of Britain, may have visited the Oregon Coast on one of these raids against the Spanish, but his descriptions aren’t clear enough to say. He had first caught sight of the Pacific Ocean as a young man after trudging across the Isthmus of Panama, where he’d gone to raid a Spanish settlement in 1573.

Four years later Drake sailed around the Horn for his daring adventure to pillage Spanish ships in the Pacific, capturing so much gold and other booty his ships nearly sank with the treasure. At this point no one in Europe knew anything about Oregon. The colonies of Virginia and Massachusetts had recently been formed. California was believed to be an island, and Drake may have thought he could escape the angry Spanish by doing a run around the north side of California and taking a direct shot for the Atlantic and home. But the weather was so bad he turned back south with no exploration of the land for uncertain passages. He returned to England in 1580 by going back around the Horn.

For the next 200 years the British did nothing to secure the west coast. But in 1763 after the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War in the US) Britain gained the Canadian colonies from the French and began exploring the western sea, sending out Captain James Cook of the Royal Navy to map the uncharted region.

The first known use of the name “Oregon” came in 1765 when Major Robert Rogers submitted a proposal to King George the Third, asking him to send an overland expedition to search for the elusive northwest passage believed to exist between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Roberts proposed to go from the Great Lakes to the Head of the Mississippi and from there to a “River called by the Indians Ouragon,” also called the River of the West, which flowed westward into the Pacific Ocean.

The expedition was not completed, but one of the partners in the venture, Jonathan Carver, later wrote a book about his travels in which he names the river “Oregon or River of the West,” so spelled in the published version. The name Oregon began to appear on maps to identify the river. Both Roberts and Carter claimed the name was of Indian origin, not a derivation of a French or English word as some scholars suggested. Lewis and Clark evidently found no tribes in the area using that name, and detractors point to its similarity with the French word ouragan, meaning “windstorm,” an apt reference for this river when its winds whip up. The French comingled with Native Americans throughout North America, and other tribes could have picked up on the reference. The controversy continues.

One of Jonathan Carver’s maps, above, published in the book of his travels in 1778 shows the “River of the West” on the west coast of North America.

One of Jonathan Carver’s maps, above, published in the book of his travels in 1778 shows the “River of the West” on the west coast of North America.

Captain Cook kept exploring by sea. On his third voyage into the Pacific he visited the Oregon Coast in hopes of finding the northwest passage, but he missed the mouth of this legendary River of the West. He had set sail for this third voyage on July 12, 1776, only a few days after the American colonists declared their independence. Just when he was hoping to benefit Europe with new discoveries, his nation was attempting to put down a revolution in one of their previous discoveries. Cook was killed on this journey in a fracas in Hawaii, but when his men returned home, word of fantastic trade possibilities leaked out.

China was offering high prices for furs from the Pacific Coast, which traders could obtain from the local tribes for simple trinkets, and the furs could be exchanged in China for tea and other Chinese goods to take to Boston for a fine profit. A Boston company was formed and sent out Captain John Kendrick and Captain Robert Gray in two vessels, the Columbia Rediviva and the Lady Washington. The fur trade era had begun.

The Spanish at this time considered the Pacific their own pond and the Pacific Coast of North America part of their domain. They were clearly suspicious of the US purpose in these waters. Kendrick and Gray, for their part, were instructed to keep the peace, but they had a few scrapes even so. During the venture Gray dared move his ship closer to the coastline than most ships and discovered many bays and inlets and promising streams. He returned to Boston in the Columbia Rediviva, the first US ship to circumnavigate the globe, and his company quickly refitted the Columbia, sending Gray back to the Pacific.

On May 11, 1792, Gray revisited a place he believed to be the mouth of a large river. He tried for days to enter the stream across a formidable bar, then finally sent a smaller craft to find a channel by sounding. When his men found what they considered a safe channel he crossed the bar into a great wide river. The local tribesmen met him with excitement, having never seen such a craft come into their waters, and Gray knew he had made a significant discovery. Was this the River of the West? The Oregon? The northwest passage? Perhaps. He named the river the Columbia after his ship.

Gray sailed upriver a ways, went aground, then drew free again, finally leaving for the sea after nine days. Sailing up the coast he approached the British Captain George Vancouver, who was also exploring the area. Gray told Vancouver about his discovery, and Vancouver sailed south along with another British vessel commanded by Lieutenant William Broughton to check out what Gray had found. Vancouver’s ship being too large to cross the bar, he dispatched Broughton with the smaller of their two vessels. Broughton sailed up the river about 120 miles, considerably farther than Gray, but Vancouver graciously credited Gray with the discovery and accepted the name Columbia.

London would later use Broughton’s journey into the river as part of their claim to the country. And when Dr. John McLoughlin chose the site for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s western headquarters he noted the location to be within this stretch sailed by his countryman Broughton, just downriver from the height of Broughton’s excursion on the river. McLoughlin named the fort for Broughton’s superior officer, Vancouver.

As the River of the West became the Columbia, the name Oregon gradually came to refer to the region surrounding this great river.

Sources:

Carey, Charles H., LLD. General History of Oregon: Through Early Statehood. Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1971.

Various websites

NEXT: Fur Traders

June 25, 2016

Fort Vancouver Event Coming Soon

My reading and signing event at the fantastic Fort Vancouver site in Vancouver, Washington, is just three weeks away, Saturday, July 16, starting at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. As mentioned in my March post “Upcoming Book Event at Fort Vancouver,” it was a dream of mine to hold an event at this historic fort for my new historical novel, The Shifting Winds, because the fort plays a significant part in the story. Now that dream is about to happen.

Through my presentation at the fort Visitor Center–a lecture, a slideshow of related photos, and a tour of the fort–I hope to draw people back to the days of my story. The lecture and book signing will be from 2 to 3:30. Afterward, from 4 to 5 I’ll lead attendees on a tour through the fort and highlight some of the places that appear in my book. The bastion in the fort palisade is shown above.

Through my presentation at the fort Visitor Center–a lecture, a slideshow of related photos, and a tour of the fort–I hope to draw people back to the days of my story. The lecture and book signing will be from 2 to 3:30. Afterward, from 4 to 5 I’ll lead attendees on a tour through the fort and highlight some of the places that appear in my book. The bastion in the fort palisade is shown above.

Several scenes in the story take the reader to this amazing spot of British civilization in a wilderness isolated from all that’s familiar to the young American protagonist, reluctant pioneer Jennie Haviland. And one of the major players, Hudson’s Bay Company clerk Alan Radford, works at the fort.

In the early 1840a when the story takes place, Fort Vancouver stands as the center of the British fur trade in the Pacific Northwest, and American settlers have just begun trickling into the area, hoping to gain the land for the United States. For more than 20 years Britain and the United States have jointly occupied the Oregon Country, unable to come to terms on a boundary between them.

Given Fort Vancouver’s significance in Western American history, the fort has been faithfully reconstructed as a living representation of the times, including the home of the commanding officer and his second in command, above, which is furnished much as it would have been when Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin lived there and essentially ruled the Oregon Territory. The McLoughlin sitting room is shown below.

Given Fort Vancouver’s significance in Western American history, the fort has been faithfully reconstructed as a living representation of the times, including the home of the commanding officer and his second in command, above, which is furnished much as it would have been when Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin lived there and essentially ruled the Oregon Territory. The McLoughlin sitting room is shown below.

Now a National Historic Site maintained by the National Park Service, the fort offers visitors a chance to step back in history and see what life was like in the fort’s heyday.

Now a National Historic Site maintained by the National Park Service, the fort offers visitors a chance to step back in history and see what life was like in the fort’s heyday.

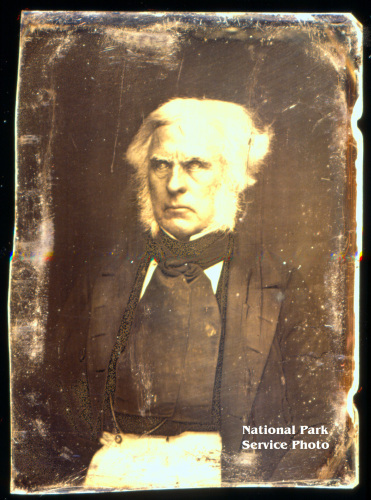

Chief Factor McLoughlin, shown in the daguerreotype at right, is one of the real characters portrayed in the book.

Chief Factor McLoughlin, shown in the daguerreotype at right, is one of the real characters portrayed in the book.

My story takes place during the historic time of rising tension between the two nations over this one land. Within that true story of conflict, a fictional clash develops between two men–the British HBC clerk Alan Radford, and American mountain man Jake Johnston–who vie for protagonist Jennie as their nations vie for Oregon.

The park’s main calendar page shows my presentation and book signing now. Just scroll down to the 16th and there I am.[image error] To find the fort and center, their website offers maps and directions. The Visitor Center, where my event will be held, is at 1501 East Evergreen Boulevard.

The Visitor Center Bookstore will have copies of The Shifting Winds for sale, as well as copies of my previous book, A Place of Her Own.

My thanks to the National Park Service and the Friends of Fort Vancouver for co-hosting the event. And a special thanks to Mary Rose, Executive Director of the Friends of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, for making the arrangements.

In these next three weeks I plan to offer a series of posts here on my blog to help set the stage for my story and for this event. Because the posts will delve into the historical setting, I’ll call the new series “The True Shifting Winds.”

June 24, 2016

Pleasant Evening at Bookmine

Gail at The Bookmine in Cottage Grove set up a lovely display for my encore signing and reading party for The Shifting Winds Thursday evening, to which I added my new poster for the book (at left).

Gail at The Bookmine in Cottage Grove set up a lovely display for my encore signing and reading party for The Shifting Winds Thursday evening, to which I added my new poster for the book (at left).

We also had copies of my first book, A Place of Her Own, available and actually sold quite a few of them as well. It continues to gain interest.

It was a busy evening with the Farmer’s Market just outside, and several people drifted in to join those who’d come for the event.

An attentive group stayed for the readings. I chose three short segments, a couple of tense cliff hangers and, for a change of pace, one of Joe Meek’s stories. Joe, a mountain man, is one of the real characters in the book. Gail also offered refreshments, shown in the photo above, so folks nibbled and listened.

After the reading we had a few questions. And I signed a few books.

Altogether a pleasant evening. It was nice to have both of my daughters, Carisa and Christiane, and my granddaughter, Calliope, with me.

Thanks to Christiane for taking the pictures.

June 16, 2016

Bookmine Encore

A chill breeze swept in through the open doorway of The Bookmine in Cottage Grove the evening of the season’s first Art Walk in April.

A chill breeze swept in through the open doorway of The Bookmine in Cottage Grove the evening of the season’s first Art Walk in April.

I was at this bookstore on Cottage Grove’s historic Main Street to sign and sell my books and had planned to do a reading from my new novel, The Shifting Winds.

Proprietor Gail Hoelzle came over to my table toward the end of the scheduled event and smiled. “I think we should have another event for you, a regular signing and reading.”

That sounded good to me. The Bookmine had hosted me a couple of years earlier with my first book, A Place of Her Own, a very successful event.

“Actually we’ve done quite well this evening,” I told her.

“I know. You sold a lot of books, but you didn’t get to read.”

There never seemed a good time for a reading because the people kept moving through, apparently wanting to visit as many businesses as possible on that chilly day–and maybe to beat the rain, which had threatened all day and finally struck in earnest just before the final hour came to an end.

So we’re doing an encore, a regular book signing and reading at The Bookmine, one of my favorite stores. It’s Thursday evening, June 23, from 5 to 7, hopefully a pleasant summer day this time.

So we’re doing an encore, a regular book signing and reading at The Bookmine, one of my favorite stores. It’s Thursday evening, June 23, from 5 to 7, hopefully a pleasant summer day this time.

June 3, 2016

Gala Readers

Readers for the Mid-Valley Willamette Writers Author’s Celebration annual gala relax a little after reading from their new published works last night at Tsunami Books in Eugene. From left to right, the 2016 group: Julie Dawn, Bill Cameron, Sarina Dorie, Valerie Brooks, and me, Janet Fisher.

Bill opened the evening with an intense reading from his young adult mystery, Property of the State, which is so new he had only one copy available last night. The book will be released next week by The Poisoned Pencil. Next up was Julie Dawn, writer of “a different kind of horror,” reading from her new novel, Yosemite Rising. I read a couple of excerpts then from The Shifting Winds, part of the opening scene, followed by one of Joe Meek’s stories, a tale he actually told. I did my best to give it the Joe Meek flavor with his Kentucky drawl and mountain man jargon.

Bill opened the evening with an intense reading from his young adult mystery, Property of the State, which is so new he had only one copy available last night. The book will be released next week by The Poisoned Pencil. Next up was Julie Dawn, writer of “a different kind of horror,” reading from her new novel, Yosemite Rising. I read a couple of excerpts then from The Shifting Winds, part of the opening scene, followed by one of Joe Meek’s stories, a tale he actually told. I did my best to give it the Joe Meek flavor with his Kentucky drawl and mountain man jargon.

Valerie Brooks read next from her TravelNoirStories set in the intrigue of Paris, one of her favorite places. Her book is so new she didn’t have copies yet, but it’s coming out soon. Sarina Dorie closed the evening on a light note with a reading from her book Fairies, Robots and Unicorns–Oh My! A Collection of Funny Short Stories. From the collection she read “Eels for Heels,” a humorous urban fantasy romance previously published in Roar magazine.

It was a delightful evening. Despite the usual jitters that come from sharing our own work, all the readers seemed to have a good time, encouraged by a very receptive audience. After the readings we enjoyed chatting, selling a few books, and sampling wine and snacks.

The gala event serves to showcase published authors from the Mid-Valley Willamette Writers group with the readers chosen from entries submitted. This was the third annual gala.

May 26, 2016

Author Gala Reading

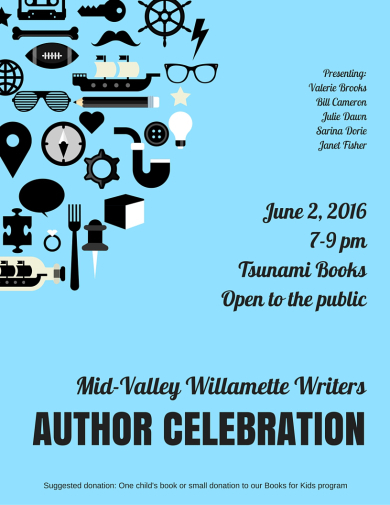

The annual Mid-Valley Willamette Writers Author Celebration happens next week when several members are selected to read from their published works. I’m excited to be one of the readers again. At this year’s event I’ll be reading from my new historical novel, The Shifting Winds.

Pulling up some pleasant memories, here’s the group that read in 2014 at the first of these gala events. That time I read from A Place of Her Own, which had just been released.

What a fun evening! It was so exciting to be sharing my very first published book. A great time for us all. I developed some lasting friendships from that gathering. We were at Tsunami Books in Eugene, the regular meeting place for the Mid-Valley Willamette Writers, and the gala will be at the same place this year.

What a fun evening! It was so exciting to be sharing my very first published book. A great time for us all. I developed some lasting friendships from that gathering. We were at Tsunami Books in Eugene, the regular meeting place for the Mid-Valley Willamette Writers, and the gala will be at the same place this year.

Here’s the poster for the event, at left.

Here’s the poster for the event, at left.

It’s the first Thursday of the month, the usual meeting night for the group, June 2, from 7 to 9 pm.

We’ll have fewer readers this time, including Valerie Brooks, Bill Cameron, Julie Dawn, Sarina Dorie, and me.

As noted on the poster it’s open to the public. The suggested donation is one new or gently used children’s book or a small cash donation in support of the group’s Books for Kids program. Tsunami Books is at 2585 Willamette Street in Eugene.

I’ll be reading the opening scene from The Shifting Winds and introducing one of the real historic characters from my book, Joe Meek, mountain man extraordinaire.

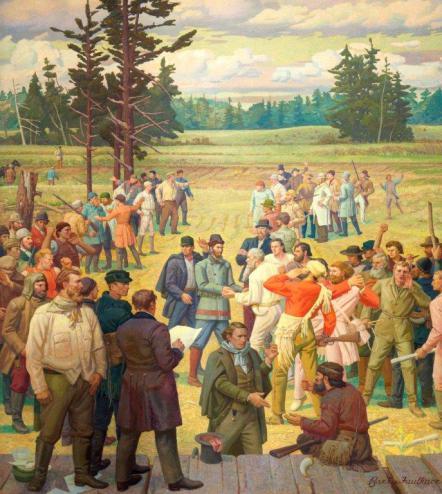

Here he is at right, portrayed in his immortal role at the gathering of settlers at Champoeg in May 1843, just 173 years ago this month.

Here he is at right, portrayed in his immortal role at the gathering of settlers at Champoeg in May 1843, just 173 years ago this month.

American settlers were hoping to get an agreement that would give them the protection of law in this isolated frontier.

When the vote seemed uncertain, the bold mountaineer called out in his booming voice, “Who’s fer a divide?” And the voters lined up to be counted.

This large mural is displayed in the Oregon State Capitol building. That’s Joe in the red shirt toward the front, rifle in hand, calling for the divide.

He was a storyteller at heart, which I guess all of us authors must be too. I look forward to hearing readings from the stories of my fellow Mid-Valley Willamette Writers authors and look forward to sharing my own.

May 15, 2016

Prose at Poetry Night

The Axe & Fiddle, a pub in historic downtown Cottage Grove, offers a change of pace this coming Tuesday night, May 17, when the entertainment turns to words. Poetry Night happens just once a month at this restaurant and public house known for its live music and craft brews, full bar, and locally sourced food, and I’m delighted to be their featured guest. But I won’t be reading poetry–or singing it.

Instead they have asked me to read from my new historical novel about Oregon’s early days, The Shifting Winds. So in keeping with the night’s theme, I’ll select a couple of short excerpts that present a bit of what might be called poetic prose.

Instead they have asked me to read from my new historical novel about Oregon’s early days, The Shifting Winds. So in keeping with the night’s theme, I’ll select a couple of short excerpts that present a bit of what might be called poetic prose.

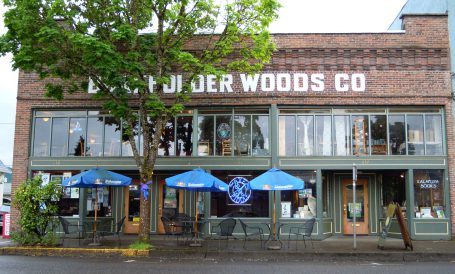

You’ll find the Axe & Fiddle on Cottage Grove’s historic Main Street on the corner of 7th and Main, next door to Kalapuya Books, the bookstore that presents Poetry Night. The building is shown at right.

You’ll find the Axe & Fiddle on Cottage Grove’s historic Main Street on the corner of 7th and Main, next door to Kalapuya Books, the bookstore that presents Poetry Night. The building is shown at right.

The show starts at 7:30 pm and is expected to run until 9:30. They open at 4 pm, so there’s plenty of time to stop in beforehand for dinner or a drink, or both, and the doors are open Tuesdays until midnight.

So what’s poetic prose? To me, it seems to show up in description that paints a scene with a touch of velvet in the words. I’ll read one of those at the event. Then it may be a stretch of the word poetic, but I’d also like to read a segment I’ve never tried for any of my other readings.

In this book, although my lead characters are fictional, I also have some real people meandering through the pages. It’s a story with a lot of real history and those people sometimes play their factual parts in the historic scenes.

In this book, although my lead characters are fictional, I also have some real people meandering through the pages. It’s a story with a lot of real history and those people sometimes play their factual parts in the historic scenes.

One of my more colorful real characters is mountain man Joe Meek, and the book includes half a dozen or so stories that Joe actually told to 19th century author Frances Fuller Victor for her 1870 book River of the West about Joe’s life as a fur trapper in the Rockies and his life in western Oregon as a settler. Joe’s speech is a mix of Kentucky, the vernacular of a mountain man, and traces that come from a boy who preferred to play with his father’s slaves rather than go to school. Poetic? Well, he was an inveterate storyteller whose words carry a certain ring.

I’m looking forward to a fun evening at the Axe & Fiddle, a very different venue than I’ve tried before. I’ll have books there for sale, copies of The Shifting Winds and also my previous book, A Place of Her Own. A big thanks to Betsy at Kalapuya Books for the invite.

May 4, 2016

Stories of Story

I spoke at the Roseburg Rotary Club meeting last night. They invited me to talk about my new book The Shifting Winds, and when I began putting together my speech for this I struggled a bit. What could I say in 20 minutes to give the essence of this full-length novel and still entertain an audience? So I asked myself, what is special about this particular book? Well, for one thing, the historical setting stands out. This story steps back in time to places here in the Pacific Northwest–like Fort Vancouver, a historic site you can visit today. And I had stories about that.

The Big House, at left, was the home of the commanding officer at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver, the western headquarters of the British fur trading empire during the nineteenth century. Much of the fort has been reconstructed on the original site in what is now Vancouver, Washington, with meticulous attention to authenticity.

The Big House, at left, was the home of the commanding officer at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver, the western headquarters of the British fur trading empire during the nineteenth century. Much of the fort has been reconstructed on the original site in what is now Vancouver, Washington, with meticulous attention to authenticity.

As I mulled over ways to present this information, the thought came to me that people want to hear stories, so my speech told stories about my story. The Shifting Winds is a historical novel of the 1840s Oregon Territory with a lot of real historical drama set in real places. While it’s often hard to find a historic site unaltered by modernization, the reconstructed Fort Vancouver can take you right back into these early times.

You can walk into the chief factor’s house where characters from my story walked and see the furnished rooms as they would have appeared in the 1840s.

You can stroll across the grounds where my characters strolled and see the Indian Trade Store and hear the blacksmith’s hammer striking hot metal on the anvil.

So in my speech I told about visiting the fort for research that inspired the book. Then I told about my dream of holding an event at the fort for this newly published book–and how it happened that this dream will come true in July. My stories.

Another way to tell about a book is to read from it. So I did that too. I’ve heard it said that we’re hardwired for stories. It’s how we communicate and our stories tend to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. We expect resolution.

But of course if you want people to read your book, you don’t want to spoil their reading by giving away the end. So you stop short, leaving them guessing. The cliff hanger. This jolts their innate sense of story.

One of the excerpts I shared in the speech showed my characters trekking up the portage trail around the Willamette Falls, shown at left. Modernization may have dimmed the glory of these falls in what is now Oregon City, but the power of the water cannot be denied. The thrum rolls through you when you stand nearby, and you can see why the settlers rushed to claim it.

One of the excerpts I shared in the speech showed my characters trekking up the portage trail around the Willamette Falls, shown at left. Modernization may have dimmed the glory of these falls in what is now Oregon City, but the power of the water cannot be denied. The thrum rolls through you when you stand nearby, and you can see why the settlers rushed to claim it.

That except follows the protagonist as she tells her suitor good-bye at the head of the falls, then decides to take a walk alone in the woods above town. There’s a reason she’s been warned against going into the woods by herself, and when she comes face to face with danger I choose to leave the vignette hanging. The audience reacted with a burst of groans and uneasy laughter as I had hoped. The tension strikes because we need the satisfying conclusion as part of our sense of story. Resolution.

So throughout the evening we shared story. Even before the meeting when I met my friend Laura Lusa who’d arranged for me to speak, she and I sat down together and shared our stories. “How are you doing?” I ask. She answers with her story. I respond with mine. Unfinished stories. How will they turn out? Will there be resolution?

During Q & A I found myself answering questions with snippets of story. And after my speech people came up to talk to me. They told me their stories–about their pioneer families, their interests in history–and I came to know them a little bit better.

Stories. It’s how we communicate. And perhaps that’s why we so need the complete stories in books. When our own stories lack completion, we answer part of our need by reading a well-crafted book with a beginning, a middle, and a satisfying end. Resolution.

April 25, 2016

Spring Art Walk Event

It must be spring! The first Art Walk of the season comes this Friday, April 29, to the charming historic downtown of Cottage Grove. And I’ll be there with my books at The Bookmine from 6 to 8 pm or later. It’s such a great store–a pleasant place to hang out during the Art Walk, or anytime for that matter.

This small Oregon town enjoys the good fortune of having three bookstores within five blocks on Main Street, from The Bookmine at 702 to Kalapuya Books at 637 to Books on Main at 319, and I’m happy to say they all stock my books. They also have a wonderful library a few blocks away (and, yes, my books are there too). A very literary place.

This small Oregon town enjoys the good fortune of having three bookstores within five blocks on Main Street, from The Bookmine at 702 to Kalapuya Books at 637 to Books on Main at 319, and I’m happy to say they all stock my books. They also have a wonderful library a few blocks away (and, yes, my books are there too). A very literary place.

I lived in Cottage Grove for several years before moving to the family farm in Douglas County, and the people of Cottage Grove continue to be supportive. I am most grateful.

The town’s Art Walk happens on the last Friday of the month from April to October. You’ll find food, art, music, a variety of shopping at the local shops, and of course books.

I’ll read a time or two from my new historical novel, The Shifting Winds, and will have that one as well as my first, A Place of Her Own, available for signing. The Shifting Winds is a fictional tale set in a lot of true history. A Place of Her Own is a true story with some creative conjecture. They’re both Oregon Trail stories about strong pioneer women. I’ll be open to informal Q & A as people stop by and to just chatting about the new story and my other work and your own stories.

If you’re in the neighborhood I hope you’ll visit me at The Bookmine.