Josh Cook's Blog, page 3

August 16, 2017

Reading is Resistance: On Free Speech & Nazis

As of writing there is a rally planned by a bunch of white men for Saturday on Boston Common and, as of writing, the supposed theme of this rally is “free speech,” and I guess it will be just coincidence or something that only white men and maybe a few white women will attend this rally. As a bookseller and a writer, the idea of free speech is not just important to me, it is vital to who I am. Protecting and providing access to ideas I disagree with is one of the fundamental responsibilities of being a bookseller and the ability to express whatever is in my mind in whatever manner I see fit, whether other people like it or not, is fundamental to being a writer. Furthermore, there is power in being around ideas that make you uncomfortable, that challenge your world view, that you disagree with and, both as a bookseller and as an author, I do feel it is also my responsibility to make sure everyone has the opportunity to be uncomfortable. But (so no one has to be nervous while I build my argument) the First Amendment right to free expression does not, in any way shape or form, apply to Nazism or white supremacy.

As with so much of the reaction to what's happening this piece will be a little raw and I can't promise the best structure or that I have considered and accounted for all possible counter arguments or implications of my argument. Furthermore, in terms of a bookseller's specific role in how and what information and opinions are accessible in their communities, I will honestly say that I still feel a tension between the authors around the edges of this movement and with those who might be considered enablers of this movement (Ann Coulter and Bill O'Reily immediately spring to mind), who don't explicitly talk about white supremacy, who I, personally, wouldn't want to stock on my shelves and that responsibility to get whatever book a reader wants for them, without any judgment. There is a point where the debate becomes more nuanced, when the arguments around free speech and bookselling become more fraught and when we'll be faced with either/or decisions without an obvious answer (and I'm not counting the "do I need to make this money" as part of this nuanced point because, well, I don't believe that money has any real relevance whatsoever to this issue) and I'll be honest right now, that I don't explore that point in this post. Even in a brain dump like this, I just don't have it all settled in my head enough to share.

A lot of you who read this will already agree with me, and if you've been following this issue, you'll see a number of familiar points, some of which have been made far more eloquently than I ever could by cartoons and other images and tweets. As a white dude, I see it is as my responsibility to talk to other white dudes and as writer I see it as my responsibility to create prose that might pull someone back from the edge, refine another white dude's understanding of what they are doing in the world, tweak an attempted-ally's behavior, or, at the very least, add the privilege of my voice to existing arguments. Finally, I also recognize that, historically, the types of ideas and expressions that are censored by the government have been those that I would consider protected under the First Amendment. Most of the time, when the government (or whoever) seeks to restrict expression, their goals have been to either silence dissent or police sexuality. With all of that said, I'll say this again: The First Amendment right to free expression does not, in any way, shape or form, apply to Nazism or white supremacy.

I think it's important to start by exploring exactly why the First Amendment and the right to free expression is important. Then I'm going to talk about the types of speech we already restrict. Finally, I'm (hopefully) going to pull that all together into something coherent. Finally, (for real this time, sorry for all the preambles) I should probably reiterate that this post (and really all my other posts, tweets, etc) reflect only my opinion. OK.

On a political level, there is inherent value in allowing for competing, disagreeing, divergent, even mutually opposed ideas to be expressed freely and without restraint. Debate, discourse, conversation, are the laboratories of human political, social, and artistic ideas. Allowing dissenting views to be expressed leads to better policy and creates the opportunity for consensus in a way that is simply not possible when ideas are restricted by the government. Furthermore, there is value to interacting with ideas you disagree with even if you don't reach consensus. Not only is your idea strengthened and your understanding of it deepened through your defense of it, you are able to see the nuance that makes the opposing idea legitimate and perhaps adjust your own assumptions and assessments of the idea, even if you don't agree with it. In theory, something positive could come from debating the value of an idea I agree with, like a federally administered minimum income, with a “small-government” republican even if we never reach a consensus or agreement.

Free expression is also vital to a society, because, ultimately, humans are communication animals. Our lives are defined by what, how, and who we communicate with. It is absolutely vital to our personhood that we be able to express ourselves. (Hang on to that word, “personhood.”) Not being able to express who you are is fundamentally identical to not being able to be who you are.

But, even with that, American jurisprudence, and well, basic common sense acknowledge that you can't say always say whatever you want whenever you want. Shouting “fire” in a crowded theater is, of course, the go-to example, because when you shout “fire” in a crowded theater, you risk causing a panic that leads to physical harm or death. (It should also be said, that even if everyone knows there is no fire, you still interrupt the experience the audience and your asshole ass should be thrown out even if maybe it shouldn't be arrested.) But you can also can't tell lies about someone that hurts them. Depending on the person, you also can't even share true things (like, say, a sex tape) if sharing that true thing causes them harm. You also can't call someone up in the middle of the night and threaten to kill them. You also can't (I'll throw in a “technically” here, because dudes get away with it all the time) tweet rape threats at people. Another classic ethical formulation is “You have the right to swing your fist right up until it hits my nose,” and we, as a society, have decided that some speech counts as hitting a nose.

First, and many other people, usually people of color, have said this better than I have, but I'll put it in here anyway: there is no consensus between the idea “I am a person” and the idea “No, you're not.” There is no middle ground. There is no compromise. There is no negotiation. There is no chance to grow through debate between these two ideas, because one of them assumes the other doesn't actually have personhood to grow. Nothing the whole free exchange of ideas thing is supposed to do can happen between “I am a person” and “No, you're not.”

But more importantly, white supremacy is a death threat. As clear, as distinct, as dangerous, and as damaging as calling someone on the phone and threatening to kill them. Holding a Confederate flag is no different from standing outside the home of a person of color and dragging your thumb across your throat. The fundamental idea of white supremacy, no matter how apologizers and adjacents try to soften or mitigate it, is that white people have the right to kill other people. Naziism was based on the idea that white Germans had the right to kill Jews, Romany, homosexuals, and others. The Confederacy was based on the idea that white people had the right to kill black people. Every Nazi flag is a death threat. Every Confederate flag is a death threat. Every Confederate monument is a death threat. Every school, street, park, highway, whatever, named in honor of a Confederate general, soldier, politician, or hero is a reminder to all people of color that a whole lot of white people still want the right to kill them. The n-word out of the mouth of a white person is a death threat. Every racial slur out of the mouth of a white person is a death threat. And death threats are not protected by the First Amendment.

The debate over white supremacy is over. There is a reason why there are no statues of Hitler in Germany, why Mein Kampf was banned until very recently, why Nazi symbols are only in museums. No one gains anything from white supremacy's presence in our marketplace of ideas. And it's presence is a constant, relentless threat to well-being and lives of millions of Americans. If you want to argue that Nazis and other white supremacists have the right to express their white supremacy you need to look a person of color in the eyes and tell them they don't have the right to feel safe in their own country. If you can do that, well, then I guess I'm done exchanging ideas with you.

One final point on the legitimacy of the white supremacist free speech argument: do you really believe they would permit criticism of their white power if they took over our government? Do you really believe they would encourage a vigorous exchange of opinions in a free marketplace of ideas? Do you really believe a black person would be able to express themselves freely under David Duke? Of course, not. Protests would be outlawed the next day, monuments to people of color would be torn down, and every MLK street, school, and park would be renamed. They'd confiscate every history book, defund every college they accused of “indoctrinating” the youth, and arrest every activist of color they got their hands on. Because this has never, not for one second, actually been about free speech, and those who repeat that argument have (at best) been conned. Every argument about the sanctity of free speech is (at best) a fundamental misunderstanding of the process of building ideas in a society, but is far, far more often, a simple smoke screen to give them a chance to recruit more sad, scared, and angry white men to their hateful cause.

As with so much of the reaction to what's happening this piece will be a little raw and I can't promise the best structure or that I have considered and accounted for all possible counter arguments or implications of my argument. Furthermore, in terms of a bookseller's specific role in how and what information and opinions are accessible in their communities, I will honestly say that I still feel a tension between the authors around the edges of this movement and with those who might be considered enablers of this movement (Ann Coulter and Bill O'Reily immediately spring to mind), who don't explicitly talk about white supremacy, who I, personally, wouldn't want to stock on my shelves and that responsibility to get whatever book a reader wants for them, without any judgment. There is a point where the debate becomes more nuanced, when the arguments around free speech and bookselling become more fraught and when we'll be faced with either/or decisions without an obvious answer (and I'm not counting the "do I need to make this money" as part of this nuanced point because, well, I don't believe that money has any real relevance whatsoever to this issue) and I'll be honest right now, that I don't explore that point in this post. Even in a brain dump like this, I just don't have it all settled in my head enough to share.

A lot of you who read this will already agree with me, and if you've been following this issue, you'll see a number of familiar points, some of which have been made far more eloquently than I ever could by cartoons and other images and tweets. As a white dude, I see it is as my responsibility to talk to other white dudes and as writer I see it as my responsibility to create prose that might pull someone back from the edge, refine another white dude's understanding of what they are doing in the world, tweak an attempted-ally's behavior, or, at the very least, add the privilege of my voice to existing arguments. Finally, I also recognize that, historically, the types of ideas and expressions that are censored by the government have been those that I would consider protected under the First Amendment. Most of the time, when the government (or whoever) seeks to restrict expression, their goals have been to either silence dissent or police sexuality. With all of that said, I'll say this again: The First Amendment right to free expression does not, in any way, shape or form, apply to Nazism or white supremacy.

I think it's important to start by exploring exactly why the First Amendment and the right to free expression is important. Then I'm going to talk about the types of speech we already restrict. Finally, I'm (hopefully) going to pull that all together into something coherent. Finally, (for real this time, sorry for all the preambles) I should probably reiterate that this post (and really all my other posts, tweets, etc) reflect only my opinion. OK.

On a political level, there is inherent value in allowing for competing, disagreeing, divergent, even mutually opposed ideas to be expressed freely and without restraint. Debate, discourse, conversation, are the laboratories of human political, social, and artistic ideas. Allowing dissenting views to be expressed leads to better policy and creates the opportunity for consensus in a way that is simply not possible when ideas are restricted by the government. Furthermore, there is value to interacting with ideas you disagree with even if you don't reach consensus. Not only is your idea strengthened and your understanding of it deepened through your defense of it, you are able to see the nuance that makes the opposing idea legitimate and perhaps adjust your own assumptions and assessments of the idea, even if you don't agree with it. In theory, something positive could come from debating the value of an idea I agree with, like a federally administered minimum income, with a “small-government” republican even if we never reach a consensus or agreement.

Free expression is also vital to a society, because, ultimately, humans are communication animals. Our lives are defined by what, how, and who we communicate with. It is absolutely vital to our personhood that we be able to express ourselves. (Hang on to that word, “personhood.”) Not being able to express who you are is fundamentally identical to not being able to be who you are.

But, even with that, American jurisprudence, and well, basic common sense acknowledge that you can't say always say whatever you want whenever you want. Shouting “fire” in a crowded theater is, of course, the go-to example, because when you shout “fire” in a crowded theater, you risk causing a panic that leads to physical harm or death. (It should also be said, that even if everyone knows there is no fire, you still interrupt the experience the audience and your asshole ass should be thrown out even if maybe it shouldn't be arrested.) But you can also can't tell lies about someone that hurts them. Depending on the person, you also can't even share true things (like, say, a sex tape) if sharing that true thing causes them harm. You also can't call someone up in the middle of the night and threaten to kill them. You also can't (I'll throw in a “technically” here, because dudes get away with it all the time) tweet rape threats at people. Another classic ethical formulation is “You have the right to swing your fist right up until it hits my nose,” and we, as a society, have decided that some speech counts as hitting a nose.

First, and many other people, usually people of color, have said this better than I have, but I'll put it in here anyway: there is no consensus between the idea “I am a person” and the idea “No, you're not.” There is no middle ground. There is no compromise. There is no negotiation. There is no chance to grow through debate between these two ideas, because one of them assumes the other doesn't actually have personhood to grow. Nothing the whole free exchange of ideas thing is supposed to do can happen between “I am a person” and “No, you're not.”

But more importantly, white supremacy is a death threat. As clear, as distinct, as dangerous, and as damaging as calling someone on the phone and threatening to kill them. Holding a Confederate flag is no different from standing outside the home of a person of color and dragging your thumb across your throat. The fundamental idea of white supremacy, no matter how apologizers and adjacents try to soften or mitigate it, is that white people have the right to kill other people. Naziism was based on the idea that white Germans had the right to kill Jews, Romany, homosexuals, and others. The Confederacy was based on the idea that white people had the right to kill black people. Every Nazi flag is a death threat. Every Confederate flag is a death threat. Every Confederate monument is a death threat. Every school, street, park, highway, whatever, named in honor of a Confederate general, soldier, politician, or hero is a reminder to all people of color that a whole lot of white people still want the right to kill them. The n-word out of the mouth of a white person is a death threat. Every racial slur out of the mouth of a white person is a death threat. And death threats are not protected by the First Amendment.

The debate over white supremacy is over. There is a reason why there are no statues of Hitler in Germany, why Mein Kampf was banned until very recently, why Nazi symbols are only in museums. No one gains anything from white supremacy's presence in our marketplace of ideas. And it's presence is a constant, relentless threat to well-being and lives of millions of Americans. If you want to argue that Nazis and other white supremacists have the right to express their white supremacy you need to look a person of color in the eyes and tell them they don't have the right to feel safe in their own country. If you can do that, well, then I guess I'm done exchanging ideas with you.

One final point on the legitimacy of the white supremacist free speech argument: do you really believe they would permit criticism of their white power if they took over our government? Do you really believe they would encourage a vigorous exchange of opinions in a free marketplace of ideas? Do you really believe a black person would be able to express themselves freely under David Duke? Of course, not. Protests would be outlawed the next day, monuments to people of color would be torn down, and every MLK street, school, and park would be renamed. They'd confiscate every history book, defund every college they accused of “indoctrinating” the youth, and arrest every activist of color they got their hands on. Because this has never, not for one second, actually been about free speech, and those who repeat that argument have (at best) been conned. Every argument about the sanctity of free speech is (at best) a fundamental misunderstanding of the process of building ideas in a society, but is far, far more often, a simple smoke screen to give them a chance to recruit more sad, scared, and angry white men to their hateful cause.

Published on August 16, 2017 08:28

August 10, 2017

There is a Story Here: On the Book of Disquiet

There is a story here. I know it doesn't look like a story, that it doesn't have the plot you expect from a story or the characters you expect from a story or the relationships you expect from a story or the arc of events you expect from a story, but I assure you it is a story. It is a story about the course of consciousness, the nature of thought, the self's consideration of the self, the existence of the brain in the world. It is a story about figuring shit out, about our inability to figure shit out, about the mechanisms of understanding both the grand abstract concepts that drive art and philosophy and the bullshit your boss does in the office, and it is a story about the limitations of those mechanisms, the gears of the mechanisms, the grease of those mechanisms.

There is a story here. I know it doesn't look like a story, that it doesn't have the plot you expect from a story or the characters you expect from a story or the relationships you expect from a story or the arc of events you expect from a story, but I assure you it is a story. It is a story about the course of consciousness, the nature of thought, the self's consideration of the self, the existence of the brain in the world. It is a story about figuring shit out, about our inability to figure shit out, about the mechanisms of understanding both the grand abstract concepts that drive art and philosophy and the bullshit your boss does in the office, and it is a story about the limitations of those mechanisms, the gears of the mechanisms, the grease of those mechanisms. The thing is, unlike most stories, we all experience this story every day. We all think about the shit that happened to us and we all think about the best way to think about the shit that happened to us, and sometimes we come to conclusions and sometimes we don't and sometimes we come to different conclusions later that make those first conclusions look really fucking stupid. This is a story about how we are and how we become meaningful. But to see The Book of Disquiet as a story, to see it as distinct from a fictional diary or collection of disconnected musings you need to learn to read it as a story.

Not all books can or should be read in the same way. This is one of those ideas that sounds strange, but once put into context, is almost obvious. You would read a collection of poetry differently than you would read the next installment in your favorite fantasy epic; you would pay attention to different details, keep different types of information at the forefront of your mind as you read, and react to your own reactions differently. You read a collection of essays differently from a collection of short stories, a work of literature differently from a work of entertainment, a work you have some doubts about differently from a work your best friend swears by. Furthermore, you can even read the same book differently, depending on the context. For example, you read a book differently when you read it for a class or for a book club from when you read it for fun. Some books, the books I often consider the greatest books, need to be read differently from every other book, and one of their responsibilities and one of the definers of their greatness is that they teach you how to read themselves. So The Book of Disquiet, rather than starting with some kind of introductory passage that would try to frame this as a collection of diary entries or, at least, as a collection of distinct units, begins with a story. A story about how the “author” came to meet “Vicente Guedes,” the “writer” of everything else that will follow. Furthermore, the opening image of the first “entry” is of a “hidden orchestra” and a “symphony” or, to put it another way, of a particular type of human expression in which a series of distinct acts come together to create a unified experience.

This is a story because, directly and indirectly, through confronting the concept and through atmosphere created by the prose, the book returns again and again to one particular idea, and explores how that idea describes the narrator's experience with the world. The narrator may not change, the events may not change, the rising and falling action we associate with a plot might not happen, but the nature of this idea changes and does go through the rising and falling action we associate with a plot. In a way, the book feels almost like someone worrying at a loose tooth, but that is a story. There is conflict, there is tension (will the tooth fall out?), and ultimately, there is resolution. The concept, of course, is disquiet. Disquiet is a mercurial idea, and the narrator rolls it around in his hands, bending and stretching into different shapes, but, if I had to define it in some kind of, uh, definite way, I'd say that Pessoa's disquiet is the parallax created by the separation between existence and observation, from the fact that observing what happens and how you feel about it is distinct from what actually happens and what you feel about what actually happens. Disquiet names the perpetual Heisenberg uncertainty principle that is an inherent aspect of consciousness itself. There is a synapse between us and the world and disquiet is the emotion we feel when we think about that synapse.

This is a story about disquiet in the exact same way that In Search of Lost Time is a story about memory. The difference, of course, is in the angle of approach. Proust takes the long way (perhaps, the absolute longest way), showing the accumulation of memory over the course of a life and how the force of memory guides and shapes a life as a way to consider the ideas that describe memory. It is a long, slow build up that climaxes when a small moment triggers the emotional experience of what the fact of having memory means. It takes Proust thousands of pages to set up this climax because memory is a book with thousands of pages. (I, for one, think it's worth it.) Pessoa just goes right at it, his narrator confronting the idea directly and rarely with any kind of “real world” connection. In a way, this makes The Book of Disquiet read more like a work of philosophy or even of literary criticism (there is a lot about the act of writing in here as well), but, in a way, you can arrange any good work of philosophy into a story about an idea if you want to.

But, just because this is a story doesn't mean you need to read it as a story. Along with teaching you how to read themselves, great books also support multiple reading methods, giving readers the power to find their own best experience with the text. You could also read The Book of Disquiet as a devotional or a book of hours. You could keep it at your bedside to read upon waking or before going to sleep. You could read it front to back like a story, or you could wander through it. I think you could also get tremendous value out of it, even if you never finish it, even if you just keep circling back to the passages that most resonated with you. The Book of Disquiet is a story, but it is a story that gives your the freedom to read it as though it is not.

I've dogeared hundreds of passages. I have had my breath taken away hundreds of times. The primary motivation for writing this post wasn't necessarily the argument that the The Book of Disquiet is a story (though I think it is and I think that argument gave me the chance to have some interesting thoughts about how we read and what we consider a “story”), but that when I experience this kind of brilliance in a book I want to write about it. But I didn't want to just essentially string of bunch of blurbs together and call it a post. There can be a kind of diminishing return when you gush about a book. At some point you don't really add to your argument and at another point people can start getting suspicious and at a similar point you can set expectations so high a first impression of disappointment will follow them throughout the rest of the book. The Book of Disquiet is a masterpiece, a cornerstone of much twentieth-century fiction, an often perplexing but also delightful book, and as much as it deserves praise, as much as it deserves blurbs and handsells, it deserves essays more.

Like my bookish writing? Support my work on Patreon.

Published on August 10, 2017 19:29

July 30, 2017

Launching a Patreon

I like to joke that I have two full time jobs and neither one of them pays very much. (You know, the kind of joke when laughter always seems to be right on the edge of tears. That kind.) I'm a bookseller at an independent bookstore and a writer. I could talk for a long time about how and why our contemporary economy acts the way it does, why it values what it values, and why, say, our nation's greatest primary care doctors make less money than mediocre investment bankers, but that would be a very long way to say that, among many other valuable professions and vocations, the structure of our formal economy does not pay booksellers and writers very well. This presents one set of challenges when you're 24 and getting your shit together, but an entirely different set of challenges when you're 37 and trying to figure out how to sustain and protect the shit you got together. I have been both privileged and lucky to actually publish a book with a fantastic small press, to work for a store that values me and understands the financial limitations of working in a bookstore, and to have a partner that is willing to work at less satisfying but higher paying jobs to make up the gap. I have been very fortunate, but the result of that fortune doesn't include a retirement fund, much flexibility or long term stability and it doesn't provide contingency options if something drastic happens in my life, either bad (drastically changing housing costs) or good (my partner who is also an artist and really and truly kicks ass gets an opportunity to work in the arts, crafts, in a brewery, or something that doesn't make up the gap). Since it is important to ask for what you need, even if you might not get it, I am launching a Patreon and asking for your support.

I like to joke that I have two full time jobs and neither one of them pays very much. (You know, the kind of joke when laughter always seems to be right on the edge of tears. That kind.) I'm a bookseller at an independent bookstore and a writer. I could talk for a long time about how and why our contemporary economy acts the way it does, why it values what it values, and why, say, our nation's greatest primary care doctors make less money than mediocre investment bankers, but that would be a very long way to say that, among many other valuable professions and vocations, the structure of our formal economy does not pay booksellers and writers very well. This presents one set of challenges when you're 24 and getting your shit together, but an entirely different set of challenges when you're 37 and trying to figure out how to sustain and protect the shit you got together. I have been both privileged and lucky to actually publish a book with a fantastic small press, to work for a store that values me and understands the financial limitations of working in a bookstore, and to have a partner that is willing to work at less satisfying but higher paying jobs to make up the gap. I have been very fortunate, but the result of that fortune doesn't include a retirement fund, much flexibility or long term stability and it doesn't provide contingency options if something drastic happens in my life, either bad (drastically changing housing costs) or good (my partner who is also an artist and really and truly kicks ass gets an opportunity to work in the arts, crafts, in a brewery, or something that doesn't make up the gap). Since it is important to ask for what you need, even if you might not get it, I am launching a Patreon and asking for your support. You'll support my writing, including my blog posts here, essays, criticism, poetry and stories published elsewhere (like this recent piece on resistance and The Curfew), as well as the works that will (I hope) become my future books and any other projects, performances, and events I might write, organize, and contribute to.

You'll also support my work as a bookseller where I've made a commitment to advocate for small and independent presses, works in translation, experimental works, works that make people uncomfortable, works that challenge readers, works that are entertaining but don't have the publicity budget to get in front of your eyes; in short, the great books being written and published that deserve to be read and loved by readers but that don't get in front of readers any other way. In my time at PSB, I've advocated for authors like Valeria Luiselli, Renee Gladman, Victor LaValle, Kevin Young, Patricia Lockwood, Mary Rueffle, Yuri Herrera, Maggie Nelson, Robin Coste Lewis, Ananda Devi, Bhanu Kapil and a whole bunch of other authors you should be reading right now.

So what do patrons get as a thank you? All patrons will get access to capsule reviews of pretty much every book I read. (I'll make the first few public to give you a sense of what those reviews will look like.) Once I reach my goal of $500 a month, patrons at $5 a month and up will get an exclusive newsletter with longer considerations on books, politics, and the world as well as first looks at my writing projects slated for publication. (Scroll back through this blog to get a sense of what you might get in a newsletter.) Patrons at $10 a month and up will also get one personalized book recommendation a month. Yep, once a month, these patrons will be able to message me with what they're looking to read and/or give and get a personal recommendation. If you don't live in the metro-Cambridge area it's the closest you can get to visiting me at the store. (In some ways, it'll be even better, because I'll have the chance to do a little research.) Finally, patrons at $20 will get all that other stuff plus the occasional free book from my (sadly) finite shelves.

Thank you in advance if you end up becoming a patron, but also, thank you if you read my blog and other work, and also thank you if you read my book, and extra special thank you if you recommend it to other people. If you're one of my publishing friends, thank you for all the books you've sent me over the years and for helping bring new books into the world, even though publishing doesn't pay well either. If you're one of my bookseller friends, thank you for all of the work you do helping to keep a vital aspect of human culture afloat in our economy. If you're one of my writer friends, thank you for continuing to write. It often feels like we're shouting into a void, but we are not.

Finally, I understand, for whatever reason, you might not want to become my patron. That's cool. There is no shortage of people doing great work who deserve your support in some form or another. You can't ask if you're not ready to accept “No.” (And as a writer who still gets way more rejections than acceptances, I've built up a pretty thick skin.) But if books are important to you and writing is important to you, then even if you decide not to support me, go out to an independent bookstore (or visit one online) ask for a recommendation from the bookseller and buy a book by someone you've never heard of. Do this once a month. Do this once a quarter. Do this every year for your cool friend's birthday. Do this at whatever capacity you can. Writing a book is a series of small acts stacked on top of each other, one word at a time, and keeping the book world thriving works the same way; small acts, spread out among readers, adding fuel to one of the fundamental engines of human culture.

Support my Patreon here.

Published on July 30, 2017 20:24

July 23, 2017

Reading is Resistance: Take This Cup from Me Performance

In some ways, it was an idle thought, a passing observation, an idea that would be pretty obvious to just about anyone who was looking, but still, it caught in my brain as these things sometimes do. Pretty much since I first encountered Cesar Vallejo in an anthology edited by Clayton Eshelman called Conductors of the Pit, I knew I wanted to write a book about him. Eventually, I decided that I wanted to focus on just ten poems and call the book “10 Poems by Vallejo” even though I had (have) no idea what form or angle the book might take. Finding myself in between projects, I started typing up the ten poems I'd selected, including “Spain, Take this Cup from Me.” Said idle thought passed through my mind; there were some interesting and potentially enlightening parallels between the Spanish Civil War Vallejo wrote about and our current resistance to the Trump administration (and the notes of our own civil war playing in the background). I started thinking about how we could use Vallejo's poem to explore our own political turmoil. And, I wrote this post on Facebook:

In some ways, it was an idle thought, a passing observation, an idea that would be pretty obvious to just about anyone who was looking, but still, it caught in my brain as these things sometimes do. Pretty much since I first encountered Cesar Vallejo in an anthology edited by Clayton Eshelman called Conductors of the Pit, I knew I wanted to write a book about him. Eventually, I decided that I wanted to focus on just ten poems and call the book “10 Poems by Vallejo” even though I had (have) no idea what form or angle the book might take. Finding myself in between projects, I started typing up the ten poems I'd selected, including “Spain, Take this Cup from Me.” Said idle thought passed through my mind; there were some interesting and potentially enlightening parallels between the Spanish Civil War Vallejo wrote about and our current resistance to the Trump administration (and the notes of our own civil war playing in the background). I started thinking about how we could use Vallejo's poem to explore our own political turmoil. And, I wrote this post on Facebook: Writerly, readerly friends, especially poets or those poetic inclinations. I'm kicking around a project that might become an event or might become something else (anthology, chapbook, who knows.) It involves rewriting a poem about and inspired by the Spanish Civil War by the Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo. So, if you're a fan of Vallejo and fighting fascists and might be interested in participating, comment or send me a message. Right now, I'm just gauging interest. Thanks.

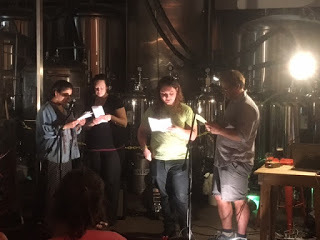

And writerly, readerly friends responded. I'm still a little blown away, but, then again, Vallejo kicks serious ass. The first result was a translation and response event called Take This Cup from Me, in The Late Night Poetry Lab reading series the bookstore hosts at Aeronaut brewing.

Throughout the event, a slideshow juxtaposing images from the Spanish Civil War and the political turmoil of the last year or so, played. What struck me about these juxtaposed images was the similarities and differences in the energies of the people in the pictures. There was a vibrancy in most of the images from both eras. Even if that volume of energy was driven by anger as it was at Trump rallies, there was a volume to the emotions that was thrilling. But there was something different in the eyes of the people in the images that were clearly from later in the Spanish Civil War. I was paying attention to too many other moving parts (like getting the slideshow to actually work) to really identify what I saw in those eyes; maybe a kind of exhausted defiance, maybe just exhaustion, maybe something else entirely, but it is clear something happens to people over the course of a long struggle. And, I suspect, regardless of what happens with Trump himself, we're going to find out what it is.

The main event of the evening was what I called a cascading line by line translation. Reading one line at a time, the poem was performed first in the original Spanish and then in three different English translations, Eshelman, Gerard Malanga, and an original translation made for the event by Maria Jose Gimenez and Anna Rosenwong. This let us hear some of the different ways Vallejo's Spanish could be rendered in our English and it was fascinating. Sometimes the differences were subtle, some of the differences were drawn from the strangeness and complexity of Vallejo's vocabulary and imagery, and some were, in the moment at least, inexplicable to me. More than a few times I had to remind myself to focus on the line I was about to read rather than the differences in the lines I'd just heard.

The main event of the evening was what I called a cascading line by line translation. Reading one line at a time, the poem was performed first in the original Spanish and then in three different English translations, Eshelman, Gerard Malanga, and an original translation made for the event by Maria Jose Gimenez and Anna Rosenwong. This let us hear some of the different ways Vallejo's Spanish could be rendered in our English and it was fascinating. Sometimes the differences were subtle, some of the differences were drawn from the strangeness and complexity of Vallejo's vocabulary and imagery, and some were, in the moment at least, inexplicable to me. More than a few times I had to remind myself to focus on the line I was about to read rather than the differences in the lines I'd just heard.The cascading line by line translation was followed by a number of responses to Vallejo's piece. A poem by Epi Arias was performed in both Spanish and English. Then, I performed my original line-by-line response to Eshelman's translation (posted below).

Perhaps my favorite part of the event was that, through Chris Boucher, I was able to connect with Jean-Christophe Cloutier, who recently translated some works by Kerouac, and get my response translated into Quebecois French. I grew up in Lewiston, a French-Canadian mill town in Maine, and, though I have plenty of Quebecois heritage (including a great uncle who played hockey against/with Maurice Richard once) I don't feel as though I have a particularly strong connection to it. Getting my poem translated into Quebecois interacted with the theme of the event and strengthened this connection for me. Furthermore, it was fascinating to hear my work in another language. Even without being able to speak French (Quebecois or otherwise), it was clear that this translation brought out an anger, that, in the English original, was under the surface and between the lines. What was a kind of exasperated frustration, a long sustained, “Guys, seriously, come on,” became a glorious spittle-flecked rant, a kind of linguistically hallucinogenic “These fucking guys!” (There was also something truly beautiful about listening to this angry Quebecois poem echoing around a bar.)

But that is, of course, the power of translation. Translating a work from one language to another, in essence creates an entirely new work that is in direct conversation with the original, highlighting and illuminating aspects of the ideas in the original that its original language was unable to express. In many ways, our ability to express ourselves in words is fundamentally limited by the language we use, a language (any and every language) that simply cannot contain and transmit all of our complexities. Every time the idea is translated into another language a different aspect of it is revealed. Which leads me to a kind of Borgesian idea; that the only truly complete thought is one that has been translated into every human language that has ever or will ever be spoken.

Next Alyeda Morales read an original response in Spanish and did a fantastic job. Not speaking Spanish, I only understood the occasional word here and there. (OK, that occasional word was “gringo.”) Which got me thinking. I, personally, love hearing people speak languages I don't know. Maybe it's because, as a writer I have an inherent interest in language, maybe it's because I like to try to figure out what people are saying, or maybe it's because, as a poet, I'm interested in the mechanics of the sound of language. Regardless of why, one of my favorite parts of living in a city is listening to conversations in languages I don't understand. (Which makes me wonder what a sociological study examining how people react to overhearing a foreign language would reveal.)

Given that there was so much Spanish in this performance and a little Quebecois, for me, and many other audiences members, this was a musical event as much as it was a poetry event, an experience of the sound of the human voice as much as it was an experience of the spoken word. Which meant having singer-songwriter JD Debris close the night with his song “Vallejo,” (which he tweaked specifically for the event) was a perfect way to end the performance.

Given that there was so much Spanish in this performance and a little Quebecois, for me, and many other audiences members, this was a musical event as much as it was a poetry event, an experience of the sound of the human voice as much as it was an experience of the spoken word. Which meant having singer-songwriter JD Debris close the night with his song “Vallejo,” (which he tweaked specifically for the event) was a perfect way to end the performance.Because it was Vallejo's words that started this whole project, I concluded the event by reading this excerpt from Vallejo's essay “The Great Cultural Lessons of the Spanish Civil War” from The Selected Writings of Cesar Vallejo:

But the jurisdiction of thought has its revenge. If the protest cries out loud and clear, and the expression of combat in the flesh truly explodes against the coagulated powers of the economy, then the timeless inflection of an idea from a speech, article, message, or manifestation could be a petard that falls into the guts of the people and explodes into certain incontrovertible outcomes on the day we least expect it. It's by thinking and constructing, without expecting immediate explosive miracles from their present work, and by devoting the maximum spiritual strength and dignity necessary for the social interpretation of contemporary problems...that [intellectuals] exercise influence and have a bearing on the ulterior process of history. And it's especially important for the intellectual to translate the popular aspirations in the most authentic and direct way, worrying less about the immediate...effect on their actions and more about their resonance and efficiency in the social dialectic, since the latter, in the long run, laughs off hurdles of all kinds, including economic ones, when a social leap is ripe for the taking.

And...I've decided that, among other goods the Spanish people's victory over fascism will bring is proof to foreign intellectuals that, although creating an intrinsically revolutionary work in the silence and seclusion of a study is a beautiful and transcendent act, creation is even more revolutionary when it's done in the heat of battle by pulling it from life's hottest and deepest pits.

At time of writing (which, given the pace of our times should be an assumed phrase), Donald Trump is reportedly considering finding a way to fire Robert Mueller, pardoning everyone in his family, and pardoning himself. At the same time, for reasons that really and truly only seem to be a personal vendetta Mitch McConnell has against President Obama, Republicans are trying to destroy the contemporary American healthcare system. A process that started with Nixon's Southern Strategy and intensified under the politicizing of radical Christianity, has culminated in a national, mainstream party enacting and supporting the transformation of the United States of America back into a malignant and overt white supremacist nation. I don't know what the fuck is going to happen next. I mean, we all know how the Spanish Civil War turned out. I don't know if events, acts, and moments like these really help. Well, I know they help me. I know they helped the other performers and I know they helped at least some of the people who attended. And I know that we must fight, both using established techniques and flailing about the vastness of human experience for something that might break through.

Finally, though it can be easy to dismiss poetry performances, acts of art, and other experiments with expressing dissent as impractical or silly, or as alienating to some other population one hopes to ally with politically in 2018, though it can be easy to point to a translation event at a bar and ask how that could possibly influence Senator Susan Collins or whichever other Republican we're hoping might actually act with a modicum of human decency, we need to remember that acts of poetry, acts of art, acts of creative life aren't just acts of resistance or examples of the fight; art, poetry, and creative life are also what we're fighting for.

USA, Take This Cup from Me

White dudes of the USA,if the USA falls—Hey, it could happen—if her torchfalls upon your fraternal scaffolding secured,in a necktie, by waning logistic highways;white dudes, what harvested the corporeality of grounds!how it feels to bear water for the first time!how obvious the tassels of your confidence!how to recuperate without sick days!

White dudes of the USA, motherUSA reveals the army you concealed from yourself;her others once beyond your barbutesshe appears as mother and teacher,training and strength, reside in the muscle fiber,chamber and hammer and competence, white dudes;she arms all soldiers, they remember!

If she falls—Hey, it could happen—if the USAfalls, from the homestead upon,white dudes, how could you possibly win!how by tomorrow you will be yesterday!how your atrophied muscles tremble from others' typical gravityhow the fraternal network smally betrays, the crumbs of the crumbs!How the little league will laughat mocking marionettes made from your filament enhancements!How your auxiliary attachments will be distributedone way or another and abdicating leaves fewer scars!

White dudes,sons of soldiers, meanwhile,ready or not, for with or without you, the USA is changingher gaze into phallus agnostic eyes,body cameras, riots, and people.Ready or not, for sheawokens catastrophically, knowing justwhat to do, and she has in her handsthe legal case, arguing away,the case, the one with the provisions,the case, our argument for!

Ready or not, I tell you,ready or not the white between the print, the whisperof being and the strong reveille of the monuments, and eventhat of your chambers, which walk with two stones!Ready or waiting, and ifthe torch comes down,if the barbutes shrink, if it is lunch,if seams occupy the balance of our logistic highways,if there is potent creaking in the executive joints,if I am late,if they do not regard you, if the barricaded earsstarve you, if motherUSA falls—Hey, it could happen—let go, white dudes of the world, let go of entitled!...

Published on July 23, 2017 19:32

June 28, 2017

Buses & IDs: A Different Strategy for Democrats in 2018

I tend to believe the idea of Democrats as weak, disorganized, unstructured, plagued with infighting, etc., is an idea that comes more from how we cover the horse race of politics and how successful Republicans are at framing discourse than any actual weakness, disorganization, infighting, etc., that exists within the party. To put this another way, respect for nuanced debate and difference of opinion within a shared goal or identity can look like all of those things when compared to an authoritarian party that sets much of the public conversation through ruthless repetition of bullshit while pundits, journalists, other media professionals, and many other Americans try to find a different answer for the success of terrible Republican policies besides “America is racist.” Which is not to say that the Democrats are perfect or always have good strategies. I, for one, attribute an amount of Obama's success in 2008, and specifically the success of his coattails in bringing other Democrats along with him to Howard Dean's fifty-state strategy and that the hyper focus on specific districts was part of why Democrats lost Obama voters to Trump in 2016.

I tend to believe the idea of Democrats as weak, disorganized, unstructured, plagued with infighting, etc., is an idea that comes more from how we cover the horse race of politics and how successful Republicans are at framing discourse than any actual weakness, disorganization, infighting, etc., that exists within the party. To put this another way, respect for nuanced debate and difference of opinion within a shared goal or identity can look like all of those things when compared to an authoritarian party that sets much of the public conversation through ruthless repetition of bullshit while pundits, journalists, other media professionals, and many other Americans try to find a different answer for the success of terrible Republican policies besides “America is racist.” Which is not to say that the Democrats are perfect or always have good strategies. I, for one, attribute an amount of Obama's success in 2008, and specifically the success of his coattails in bringing other Democrats along with him to Howard Dean's fifty-state strategy and that the hyper focus on specific districts was part of why Democrats lost Obama voters to Trump in 2016.I think the Democrat strategy for 2018 is still very much taking shape and it is still early to have fully synthesized the results of this recent round of special elections into a coherent strategy, but I have one idea that I haven't seen floating anywhere else that I think will help them break gerrymandered districts, mitigate the impact of voter suppression, and at least flip the House and perhaps even take the Senate.

That idea: Charter buses and shuttles to run from college campuses and minority community centers to the correct polling locations on election day and assume the costs of getting whatever ID is required to vote in whatever state for those who cannot afford it. Elections, it seems, have become a turnout a game one way to get likely Democrat voters to turn out is get them registered and drive them to the polls.

There is some argument that Democrats should continue to reach out to moderate Republican voters, that there is something active Democrats can do that will pull back voters who switched from Obama to Trump or capture centrists and moderates who sat out 2016, that a series of measured and moderate policies and messages will capture those moderate Republicans who are put off by some of what's happening in their party. It's an idea that sounds reasonable. That said, if Trump admitting to serial sexual assault, flaunting the norms around conflict of interest, golfing every fucking weekend, pathologically lying about everything, inadvertently or intentionally leaking state secrets and intelligence, all while being under investigation for what would be the single greatest political crime in our nation's history won't convince a “moderate” Republican to defect for an election cycle or two, what “centrist” policy would? Trump is doing damage that will take decades to undo if it can ever be undone. Why would we have to make any other argument to convince someone to abandon the Republican party at this point?

And it's not like Congressional Republicans have acted much better. For reasons I still don't understand, they have rushed and rubber-stamped every single one of Trump's atrocious nominees for cabinet positions, while dragging their feet (at best) on the Russia investigation. They are also, again for reasons I simply cannot understand, rushing to pass objectively disastrous and historically unpopular legislation. If the Senate bill manages to pass and Trumpcare becomes law, sure, you'll probably want to run a bunch of ads in every district about it, but, again, if the past sixish months haven't convinced Republicans to defect, some kind of middle ground economic policy isn't going to do it.

The lesson from Georgia is simple: All that matters to a critical mass of Republicans is that they vote Republican. In Georgia-6, Republicans had a significant registration advantage, one created intentionally to guarantee a Republican victory, and, despite everything else, Republicans showed up and voted for the Republican. Maybe I'm must being cynical, but I suspect, unless actual collusion between Putin and the Trump campaign is proved at a criminal court level and Republican Congressional complicity is proved at a criminal court level (and even then), Republicans will show up in 2018 and vote Republican. And when they do, the current gerrymandered, small state preferring, and voter suppressed system will deliver them victories.

And so, instead of spending money on ads that attempt to reach out to disaffected Republican voters, instead of developing a platform that tries to lure them into the Democrat fold for a cycle or two, Democrats, at a national party level, should leverage their Super PAC money, partner with existing voter rights organizations or build their own, and foot the bill for driving college students and minority voters back and forth to the polls while helping people surmount the barriers to voting tactically built by Republicans to suppress likely Democratic voters. (I'm a bit of a radical, but I'd go so far as to say if someone has the desire and means to move from a safe blue district to a swing district for a year, these organizations should help them sort out their registration and transportation as well.)

One might argue that Republicans would turn around and accuse Democrats of packing the polls, of voter fraud, of all sorts of electoral malfeasance. Which is true. Republicans would lose their minds over this. They'd try and pass legislation to stop it. They might even file lawsuits. They'd spend hundreds of hours on Fox News talking about how George Soros is stealing the election. My response: THEY ALREADY FUCKING DO THAT SHIT. FUCK 'EM. Republicans already accuse Democrats of everything they can think of and all without any proof whatsoever, all so they can pass legislation that gives then a major turnout advantage. Remember those thousands of voters who were supposedly bused into New Hampshire from Massachusetts? Of course not, because they don't exist. Frankly, (and this is probably why the Democratic National Committee isn't going to hire me any time soon) I don't give a fuck what Republican party leaders, pundits, and members of Congress say or think about anything because (and this is a fact I haven't seen discussed enough) they sure as shit don't give a fuck what anybody else thinks. They lied about WMDs in Iraq, they lied about Obamacare (and Republican leadership didn't do a whole lot to quell the birther nonsense), they lied and continue to lie about voter fraud, they broke the Senate and then lied about breaking the Senate, and if the Democrats do bus likely Democrat voters to the polls and do defray the cost of Republican voter suppression tactics Republicans will lie about that too, and if Democrats don't do anything to increase their turnout in 2018 the Republicans will lie about that too, because, and I can't stress this enough, at the party level Republicans don't give a fuck about anything other than electing Republicans.

I, like many Americans, believe our nation is stronger when there is political debate, when we discuss the actual policies affecting Americans, when all sides of the debate share the common goal of making America a better place, and when voters can switch allegiance from time to time as the political landscape changes, and I, like many Americans, also know there aren't any angels in politics, that at best we have people with good intentions trying to solve impossible problems, that Democrats make mistakes, that Democrats listen to their donors, that good policy can come from compromise, and that it is important to find some level of consensus for major policy changes, but Democrats didn't spew shit about death panels, Democrats didn't clog up the Senate with filibusters, Democrats didn't steal a Supreme Court seat for a serial sexual assaulter who publicly mocked a disabled journalist, and Democrats aren't covering up America's greatest scandal, so if we can't have debate, then I believe our nation is stronger when it is not run by white supremacist kleptocrats. And I think one way to boot Trump out of power is to bus college students and minority voters to the polls and pay for otherwise prohibitive voter IDs.

Published on June 28, 2017 06:42

June 14, 2017

Reading is Resistance: Bloomsday

As Bloomsday approaches, and as our reality continues to resemble the first draft of a Pynchon novel, and as the torrent of events coming from the Trump administration establishes a permanent colony in my brain so that it's nearly impossible to go through a day without some half-yelling conversation with my partner about these fucking guys, I've started thinking about the nature of politics in Ulysses. Like just about every topic in Ulysses, the more one begins to think about it, the more one finds. There is, of course, The Citizen spouting off, and rumblings of potential city council or mayoral elections. Characters revisit one of the great political scandals in Irish history and the viceregal cavalcade winds through the streets of Dublin and through the events in the book as a reminder of the constant presence of a distant power. There's also plenty of identity politics as well, as Leopold Bloom, a non-practicing Jew, navigates his relationship with the Irish nation.

As Bloomsday approaches, and as our reality continues to resemble the first draft of a Pynchon novel, and as the torrent of events coming from the Trump administration establishes a permanent colony in my brain so that it's nearly impossible to go through a day without some half-yelling conversation with my partner about these fucking guys, I've started thinking about the nature of politics in Ulysses. Like just about every topic in Ulysses, the more one begins to think about it, the more one finds. There is, of course, The Citizen spouting off, and rumblings of potential city council or mayoral elections. Characters revisit one of the great political scandals in Irish history and the viceregal cavalcade winds through the streets of Dublin and through the events in the book as a reminder of the constant presence of a distant power. There's also plenty of identity politics as well, as Leopold Bloom, a non-practicing Jew, navigates his relationship with the Irish nation.And, like all great books, if you put effort into the project you can find a way to make the politics in Ulysses relevant to our experience today. Though, there is no election or slide from democracy to fascism happening in the book, it is clear we are also watching a long standing (and undecided) conversation about what kind of nation Ireland should be, not just in terms of home rule or British rule, but also, like us, about what it means to be Irish, what it means to live in Ireland, and what it means to consider yourself a citizen of Ireland.

But when I think about politics and Ulysses through the lens of resistance and our personal relationship to resistance, I think less of the grander architectures and political landscapes of the book and more about one character: Leopold Bloom. Some of Bloom's political moments are overt, as when he debates The Citizen about what it means to be a member of a nation, while others are more policy specific as when he proposes a tram to move cattle so herds no longer disrupt traffic and when he recommends the government put a small amount of money in the bank for every child so that, as interest accrues on that deposit, every person has a financial safety net, while still others, like his acceptance and support of Molly's sexuality, we would see as overtly political even though Bloom (and perhaps Joyce) would not. Finally, other events and scenes in the book illuminate two other traits that seem to drive Bloom's political opinions; his curiosity and his imagination. Often, the reforms he offers in the course of his day start with him asking a question, and follow from him imagining an answer.

It isn't terribly original to describe Bloom as a reformer. Both the specific policies mentioned above Bloom offered in response to encountering a specific problem, I've talked about his drive to reform elsewhere and, though my memory is failing me at this point, he or another character might describe him as such. But our political moment is one of resistance, not reform. It is an existential struggle for a particular type of American nation, and it is a conflict with massive repercussions both in the short term and in the long term. But we can still draw from the core of Bloom's (and perhaps Joyce's) political beliefs and his motivations for reform.

Even in his wildest fantasies, in Circe, when he is able to enact a kind of hallucinatory wish-fulfillment, he doesn't imagine conquering other nations or accruing vast amounts of wealth or wielding god-like ultimately powers, but, essentially, of becoming a kind of uber-Robert Moses minus the malignant elitism that stained Moses' achievements, instituting vast social, technological, and economic reforms that would greatly improve the living conditions and lives of all those under his purview. Sure, it's foolish, filled with impossible technology, short on meaningful details, and, well, in a scene with gender swapping, S&M, and talking furniture, but ultimately it expresses a deep and profound desire, one that is (well I wanted to say “shockingly” but what shocks us anymore, so...) distressingly rejected by significant currents in our contemporary politics; to help every human being as much as possible. For Bloom, the goal of, well, everything, including government, isn't the preservation and elevation of a nation or nationality or even an ideal, but the preservation and elevation of people.

Furthermore, Bloom does two other things that illuminate his values. First, he checks on Mina Purefoy at the hospital because he heard she is going through a particularly difficult birth. Second, he follows Stephen, who is visibly drunk, into Night Town. These two big events, along with a series of smaller moments throughout the book, display Bloom's compassion. He is not a saint, he is not perfect, he has his flaws, and he makes his mistakes, but ultimately, Bloom is sensitive to the lives of those around him. He wants to ease the suffering of those who suffer and improve the lives of everyone.

What brings all of this together, what defines Bloom both as a human being and as a political actor, what makes him heroic and what makes him a role model for our own times and our own resistance, is the combination of three fundamental principles; curiosity, imagination, and compassion. For a famously difficult, confusing, and oblique book, Ulysses seems pretty direct in terms of how it thinks we should interact with our politics; a set of values that can easily be transferred from the politics of reform, to the politics of resistance. Perhaps that is universal and the distance between those two political acts is not nearly as far as I first thought. But it also could be specific to our political moment; there is a way to understand Bloom's values beyond politics, as core attitudes, or behaviors for being a decent human being and when the regime in power is so virulently anti-humanist, being a decent human being is an act of resistance in itself.

So, what does Bloom the reformer teach us in the resistance: Seek to know more than you know now, look beyond what has been done to discover what can be done, and do what you can to make the lives of others better.

Want to here me blathering some more about Ulysses? I'll be at Sherman's in Portland on Bloomsday.

Published on June 14, 2017 20:15

May 18, 2017

Reading is Resistance: Culture as Weapon

I'm going to say something and it is going to feel like pustulent garbage under a hot plate when it hits your brain, but it is true. Are ye brain-stuffs girded? OK. Here goes. Bill O'Reilly, of accused of serial sexual harassment fame, is the most important public intellectual in America of the last twenty or thirty years.

Deep breath.

OK. It is now clear that, as much as we want to blame it on things the kids use like Twitter, Fox News is a primary driving force in the polarizing of American politics and that it has radicalized almost an entire generation of white men. Fox's use of the myth of liberal bias in the media to relentlessly and dishonestly present a particular narrative is a big reason why we elected Donald Trump. Could Fox News have pulled off this twenty-year grift without the veneer of decency cast by O'Reilly? Could they have maintained the necessary attention to indoctrinate (or at least manipulate) without O'Reilly's skills in communication? Could anyone have transferred the vein-popping bluster of conservative talk radio to television better than O'Reilly?

And it's clear that O'Reilly is an extremely talented communicator. From his now cliché use of “folks,” to the direct and simple graphics, to overall delivery and body language, he was able to affect the codes of your white uncle who's really into politics, who will give it to you straight and who (courageously, of course) doesn't care who he might offend in the process. I am certain that, over the years, many people came to feel almost as though O'Reilly was their politics savvy uncle Bill and looked forward to checking in with him every day to see what he thought about what went on. (I'm tempted to describe him as the anti-Mister Rogers.) To put this another way, he used a persona (who knows how far it is from his real personality) to make coded racism, class warfare against the poor, Republican talking points, and alternative realities, emotionally compelling. When presented through O'Reilly's techniques, his ideas and opinions felt right and felt good, especially when they leveraged existing fears and biases. It would probably be a step too far to say that Bill O'Reilly is an artist, but he certainly used many of the techniques of the artist to build connections in our brain between certain emotions and ideas, policies, and (most importantly) other public figures. Obviously, O'Reilly himself would bristle at the label “public intellectual” but ultimately, given that until his recent ouster for serial sexual harassment, he discussed, analyzed, and presented ideas in public for money, he is (regardless of how bad his ideas are) the definition of a “public intellectual.”

Nato Thompson's brilliant new book, Culture as Weapon: The Art of Influence in Everyday Life , has a simple thesis; culture—art, communication, social relationships—is really a set of tools that can be used by anyone for any purpose. What makes us enjoy a painting or a song or a story or a public park can be used to sell us crap we don't need, make us loyal to corporations, and even get us to vote against our interests. This use of culture for purposes other than enriching our lives is most obvious in advertising and public relations, but it goes deeper than that to corporate strategies, store design, and, even though Thompson doesn't take it in this direction, the Republican use of tribal identity and community to keep voters Republican policies historically harm voting Republican.

Nato Thompson's brilliant new book, Culture as Weapon: The Art of Influence in Everyday Life , has a simple thesis; culture—art, communication, social relationships—is really a set of tools that can be used by anyone for any purpose. What makes us enjoy a painting or a song or a story or a public park can be used to sell us crap we don't need, make us loyal to corporations, and even get us to vote against our interests. This use of culture for purposes other than enriching our lives is most obvious in advertising and public relations, but it goes deeper than that to corporate strategies, store design, and, even though Thompson doesn't take it in this direction, the Republican use of tribal identity and community to keep voters Republican policies historically harm voting Republican.

For the most part, this book is a starting point, with Thompson setting the stage and proving his thesis (you should see my copy, I must have tagged over a hundred of Thompson's points, phrases, and ideas) and leaving it to readers and activists to explore and apply his conclusions. Perhaps the most troubling aspect of Thompson's ideas, and why they are so relevant today is that, from the Dada rejection of sense in response to Europe's disastrous decay to the community building of the Civil Rights Movement to the leveraging of social media messaging by Black Lives Matter, culture is usually used to oppose unjust powers in service to a commitment to a greater humanity. If culture can be used by the wealthiest corporations and the already powerful and unjust governments, if Pepsi feels like it has the right to use images of protest, how exactly are we supposed to use art and culture to fight today? If an earnest attempt to imbue humanity and justice in our systems of government through image, story, and community can be turned into an ad, are those attempts and are those techniques effective anymore? If part of the fundamental argument of culture and creation is the value of all human beings, how do you use it to influence people who clearly do not believe all humans are valuable? How do you fight a reality TV star?

I don't have a good answer to those questions, but there is something of a silver lining here. We are exploitable because we seek connections, because we strive for empathy, because we want to help, because we want to provide for our families, because we want strong communities. So much of how we are exploited through cultural weapons are based in the angels of our better nature. On the one hand, it makes us easy targets; just slap the label “family values” on yourself and you get almost free rein for hate and bigotry, but on the other hand, it also proves we have those angels, that even if we disagree on the process, we all want the same things. In a strange way, the most shortsighted, cynical, greedy systems of research and production have, in a way, proved the existence of our core of human decency.

Furthermore, I think it is important to point out that there is probably a reason why most artists, intellectuals, professors, creators of culture, tend to be humanist (or at least aspire to humanism even if they often fall short), to create works that inspire and empower, rather than items that compel consumption or leverage fear of the other for personal gain. Yes, there are plenty of talented, brilliant, content creators, embedding GEICO slogans into our brains and creating talking points for fascism, as there were always plenty of talented, brilliant artists willing to paint Jesus a thousand different ways for popes and cardinals, but still. There's a reason why the Right hates Hollywood. There's a reason why Evangelicals hate artists and creative expression. There is a reason why Conservatives are afraid of higher education. This is not to sanctify artists and intellectuals, but to argue that there is at least some historical, statistical implication, that engaging in the creation of culture has a close relationship with wanting to make the world a better place for everyone.

But there is still a gap between this idea and actions we can take today. On the one hand, it seems to imply the possibility of reaching out and across and finding those better angels in the people who put Trump in power and who are keeping him there, that if we could just tell the right story in the right way, we could breakthrough with at least enough of them to alter our elections, but at the same time, there has already been tons of that reaching out and the result of that, more often than not, seems to somehow distill into the idea that we need to be nice to certain white racists in order to reclaim their votes for other white Democrats.

Technique aside, it raises a question that I don't have a good answer for: can works of culture overcome tribalism in individuals? Or rather, since we know this does happen, since much of the social progress we have experienced over the course of humanity can be attributed to this very phenomenon, perhaps the question should be asked: why do some people respond strongly enough to works of culture to break out of their tribal (racist) dogmas while others do not? Can acts of humanist culture every truly gain more than temporary reprieves and incremental (often technology driven) improvements against the acts of tribalist culture like the works of Bill O'Reilly?

We like to assume the arc of history bends towards justice, but there is a chance, a good one, that the post WWII rise of democracy and egalitarianism is actually the fluke, and that we are now, to our doom, returning to the humanity's typical organization of small groups of powerful people using their power to enrich themselves and those they identify as belonging to their tribe, but that doesn't mean we give up. Each individual person raised up over the centuries of struggle for humanist societies, makes the fight worth it and works of culture, even if their techniques have been appropriated, are part of that fight. Furthermore, acts of resistance in the form of works of culture, along with whatever they may or may not do in terms of stopping the rise of fascism in the U.S, result in themselves. They have a value that outlives whatever they do or do not accomplish.

And they persist during the times of injustice, they are solace and strength for the oppressed, they are connections across cultures and across time between all those who fight for justice, and they are proof that we can create a better world even if, ultimately, we never do. They are evidence of the fight and creating evidence of the fight matters. Ultimately, Thompson's main point is not that we should reject culture as a method of positive change or resistance, but that we need to be mindful of its limitations and prepared for systems of power to respond in kind. I don't know what that looks like. I don't know if we really have time to figure out how to apply Thompson's insights while we still have a democracy. But I do know we've got to do something.

So, fight and create evidence of your fight.

Deep breath.

OK. It is now clear that, as much as we want to blame it on things the kids use like Twitter, Fox News is a primary driving force in the polarizing of American politics and that it has radicalized almost an entire generation of white men. Fox's use of the myth of liberal bias in the media to relentlessly and dishonestly present a particular narrative is a big reason why we elected Donald Trump. Could Fox News have pulled off this twenty-year grift without the veneer of decency cast by O'Reilly? Could they have maintained the necessary attention to indoctrinate (or at least manipulate) without O'Reilly's skills in communication? Could anyone have transferred the vein-popping bluster of conservative talk radio to television better than O'Reilly?