Paul E. Fallon's Blog, page 7

June 13, 2024

Father’s Day

I’ve been on the receiving end of Father’s Day for thirty years now; my children were born in 1989 and 1990; my own father died in 1994. Dad’s been gone so long that weeks, months can pass and he doesn’t cross my mind. Until something jiggers a memory and there he is again: Jack Fallon, Black Irish to the core.

Molly McCloskey (left) with her father and siblings. Photo courtesy of The New Yorker

Molly McCloskey (left) with her father and siblings. Photo courtesy of The New YorkerMolly McCloskey’s profile of her father, Jack McCloskey (The New Yorker, June 3, 2024) drew enough parallels to bring my own father back, rich in memory.

Jack McCloskey was the General Manger of the Detroit Pistons when the “Bad Boys” of the NBA edged out darlings like Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson to win the Championship in 1989 and 1990. Jack Fallon never did anything quite so notable, though he was a founding fanatic that transformed Toms River, New Jersey into a Little League baseball powerhouse that eventually won multiple state titles and the Little League World Series.

Molly was the last of six children, a basketball striver with talent; always reaching for, though never quite attaining, her father’s affection. I was the fourth of five, with no athletic talent, also striving for my dad’s affection. Until I endured so many humiliating strike-outs and got hit by so many baseballs I swallowed my miscoordination and handed in my glove.

Jack McCloskey left his family; growing up, Molly barely saw him. Jack Fallon left his family after we kids were gone; then years went by without contact.

Molly and Jack had a rapprochement, of sorts, when her dad slid into dementia. As he fell away, she became more interested in what she’d missed, reached out to players he’d coached, and discovered a man she never knew. Warm. Concerned. Present.

My dad and I had no grand rapprochement; we’d never fallen that far apart. We did, however, have an affecting final meeting. One that Molly’s article brought clear back to me.

It was the fall of 1993. My father had returned to his native New Jersey, after hauling the entire family to Oklahoma twenty years earlier (that’s a whole other story). He was dying of pancreatic cancer. His second wife, better suited to him than our mother, took great care. I’d come out as a gay man that spring. Flew to Oklahoma in the summer to tell my mother and siblings in person. And decided that, even though my father might be quite content to go to his grave without this particular bit of news, I wanted to tell him, in person, as well. So I invited myself to his home and drove across four states to spend a few hours delivering my news.

“Well, that explains baseball,” was Dad’s first response to learning that I’m gay. Immediately followed by, “It’s God’s way of dealing with population control.” I had to give the guy credit for his unique take on my life, though I declined to counter with the fact that I’d fathered two children. Children whom, multiple invitations notwithstanding, he’d never seen.

About that moment, two paintings posted on the wall above a corner desk caught my eye. My father was a copyist. He recreates photos in acrylic: part caricature; part art. I’d seen his Johnny Carson, Bob Hope, Phyllis Diller. Entertainers he loved. But here were two fresh portraits, created from photos I’d sent. My children.

I was impressed that my father had spent hours creating likeness of his grandchildren, though heartbroken that he was incapable of actually seeing them in person. As if his brushstrokes tried to satisfy an intimacy he himself could not actualize.

That moment crystallized the limits of my father’s capacity to love. Somehow, these expressions of love, created at a distance, clarified the triangle of me and my father and baseball. How I’d witnessed him jostle his players, pat them on the head, spur them to victory, be present for them in ways he never was with me. They were his true kin, the apples of his eye. I was blood related, yet utterly different.

Me (left) in my Little League shirt, with my siblings and father

Me (left) in my Little League shirt, with my siblings and fatherIt would be too strong to say I felt unloved growing up. I didn’t feel much of anything. I was neither neglected nor abused. I was simply there. Unsatisfactory. Uncoordinated. Incomplete. A genetic fluke born into the wrong family. I always thought the deficiency was mine, until I gazed at the portraits of grandchildren he’d never see, and understood that my father lacked something fundamental. A man who’d severed ties with his own parents, his own brother, his own sister. Then severed ties with his own children and now his grandchildren.

In that moment, my heart opened up to him. I decided that he loved me, and my children, as much as he possibly could. It is not for me to begrudge how meagerly it manifested.

In Molly McCloskey’s essay, she comes to accept her father’s limited love; even as he’s able to better express abundant love to his players. Her profound words triggered emotions in me at an opportune time. My son and his wife are expecting; I hope to be a grandfather in September. I don’t plan to draw pictures of my grandson. I plan to break out of the constrictions that plagued me and my father and his parents. To be there for my son and grandson at the glorious event, and all the days after. Present.

June 7, 2024

Everybody Wants to Get Paid for Everything

All photographs courtesy of The Boston Globe

All photographs courtesy of The Boston GlobeA couple of months ago The Boston Globe ran an article about the Dartmouth College basketball team, which voted to form a union. I imagined the writer trying mightily not to pen the story as satire. Which got me wondering, what is the proper perspective from which to write about a bunch of privileged guys (they go to Dartmouth, after all) wanting to get paid for playing a sport they choose to play, but they’re not all that good at (they go to Dartmouth after all)? This is not a case of a basketball powerhouse taking advantage of hardscrabble yet incredibly tall kids for whom basketball is the key to their future. The NCAA needs to address abuses in that arena. These are guys attending an elite college that does not offer athletic scholarships, but does practice need-blind admission. Back in the day, I benefited from that policy and worked in the college library as part of my work study. It never occurred to me that I should be paid for my ballroom dance prowess, though I’m a damn good dancer.

In the fifty years since my work-in-the-library days, more and more people clamor to be paid for more and more tasks. Most of the claims come from the realm of personal care. Should parents be paid to care for their children? Should spouses get paid to care for incapacitated spouses? Should children get paid to care for elderly parents?

Unlike the Dartmouth basketball players, these requests aren’t frivolous. Parents, spouses, children who care for one another in youth, sickness, and old age provide important societal services, and deflect significant costs we would all have to bear if any government hand was involved. Don’t those folks deserve to get paid?

The answer is: probably. But the question is wrong.

Life is not fair. From beginning to end. It’s not fair that I had two parents who survived into reasonable old age and then died without much need of outside assistance, while Sara, a woman I know, endured five years of her mother battling acute cancer, followed her father descending into dementia for five more. Sara cared for her parents in their homes. It was an awful burden. No one would have blamed Sara for putting her parents in a home. But she chose not to. Thus, she derived the priceless satisfaction of doing what she thought was right. We owe Sara a collective debt of gratitude, and hopefully find inspiration in her service. But do we owe her money?

The answer is: probably. But the question is wrong.

Regardless of which came first, the family unit or the almighty dollar, our culture has traditionally held that dollars apply outside the home, but not within. Farm work was paid; domestic work was not. Industrial work was paid; caregiver work was not. The Industrial Revolution, which greatly increased wage-earning work, also sowed the seeds of family unit decay. Particularly over the last two generations, the line between domestic life and wage-earning life has blurred. More and more people are taking care of others, and getting paid little or nothing for their effort. Shouldn’t everyone caring for someone get paid? Even if they are in your own family?

The answer is: probably. But again, it’s the wrong question.

If we decide to pay parents to care for their children, or spouses to care for each other, or pay children to care for their parents, where will it stop? We will never find a way to properly value and allocate money to everyone who thinks they deserve it. Before we know it, we’ll be paying Dartmouth College basketball players to do something we used to think they did for enjoyment.

The correct question is not how much we should pay this or that person for this or that service. The correct question is, “What do we need to provide everyone—I mean everyone—the means to live their best possible life?” Realizing not all of us will achieve that, since, as stated above, life is not fair. The answer to that question is, of course, Universal Basic Income. Give everyone the rudimentary amount for daily living and let each individual decide how to allocate their life.

The beauty of UBI is that it could actually reduce the outsized role that money plays in our lives. If everyone had a modest ‘enough,’ we could place more value on other things. Like creativity or spirituality or ethics or caring for those we love, or any of the values that are being completely submerged by the chase of the almighty dollar.

If someone chose to stay home with their children, they might not live as lavishly as an employed worker, but they could make that choice without going hungry. If they preferred to work and send their child to paid care, UBI would give them a leg up on that. Same same for caring for an aging parent.

As the indomitable Dolly Levi said, “Money is like manure. Put is in a big pile and it stinks to high heaven. Spread it around and everything grows better.” Let’s spread it around. Not to this person because their child is deemed sick or that person because their parent is doddering, or that basketball player, just because. Let’s give a bit to everyone so we all have a basic amount, just because we’re human, and we’re here.

Oh, and those tall boys at Dartmouth? The college refused to acknowledge or negotiate with them. Thank goodness.

May 29, 2024

My David Sedaris Challenge

David Sedaris is a well-known humorist; a go-to guy for wholesome satire with a touch of irony. He often writes about the joy and discovery of walking. In a recent article, he boasted of logging 40,000 steps and dreamed, one day, of clocking 100,000. I’m unaware of David Sedaris’ fitness-guru credentials. But that didn’t stop me from taking up his challenge.

“I could do 100,000 steps in a day,” rang in my head. “I already do 10,000. What’s another zero?”

I have a shallow gait. Walking 10,000 steps measures somewhere over four miles. Thus, a hundred thousand would require the far side of forty miles. My boyfriend Dave lives 44 miles away. Perfect! Some day, instead of cycling home from Dave’s, I’ll walk instead!

Wait a sec. I don’t walk fast. In fact, I walk slower than most anyyone I know. My daily 10,000 takes at least an hour and a half. Do the math. That’s fifteen hours of walking.

No problem, I decide. I’ll just leave early and walk late.

But…just…maybe…walking from Holden to Cambridge is a lousy route. All those hills. Few sidewalks. Better to plan a flat course with paved paths.

Proposed Walking Route

Proposed Walking RouteEureka! I will circle the Charles River! Dedicated footpaths. Few intersections. A full loop from Charlestown to Waltham and back is about 40 miles. Besides, in the (highly) unlikely case that I can’t complete the journey, I’ll never be more than a mile from a train or bus to carry me home.

I don’t tell anyone of my plan. Probably because I know there’s a bit of crazy embedded in the idea, and I’m disinclined to confront reason.

A few weeks after the Sedaris Challenge germinates, the perfect day arrives: Monday May 13. Fair-weather forecast; no commitments. The night before I make a couple of peanut butter sandwiches and stuck them in the fridge along with some leftover egg casserole and a serious hunk of chocolate cake. I lay out a pair of shorts, shirts that layer, extra socks, and a windbreaker. Set the alarm for 5 a.m., and go to sleep.

A few hours solid sleep later, I snap up, bolt awake. Excited! Further rest is futile. I give in, get up, dress, load the backpack, throw in a couple of bananas, and am out the door at 3:18 a.m. Crazy, right? Just wait.

The streets of Cambridge are near empty. When I come upon a lone woman along Brattle Street, I hack a cough of friendly warning. She crosses to the other side. I arrive at the river at 4 a.m. 5,000 steps done. Only 95,000 to go!

4:45 a.m. Boston Skyline

4:45 a.m. Boston SkylineMy early departure enables serendipitous timing. The sky outline glows the skyline at 4:45. The sun illuminates the Longfellow Bridge arches at 5:07. Boats glimmer in Charlestown marina at 6:08.

At 6:16 I stride to the eastern-most point of my route, where the Mystic River flows into Boston Harbor. 20,000 steps down: making great time! At y turnaround, a man is enjoying the sunrise; an amputee in a wheelchair outside of Spaulding Rehab Hospital. A gregarious guy, ebullient as the new day. We chat a bit; I don’t reveal the scope of my journey. T’would be a cruel taunt to a legless man.

I eat my sandwiches in motion, but my stomach hankers for more, and so I take a break at harbor’s edge and chow down on chocolate cake. Never eaten anything so decadent so early in the day. If I wasn’t so committed to walking, I could run, or maybe even fly. So much chocolate courses through me.

6:08 a.m. Charlestown Marina

6:08 a.m. Charlestown MarinaBack at the Museum of Science I shift to the Boston side of the river and head west. Again, perfect timing. The morning is cool, the breeze light, the flowers glorious. The Esplanade is full of eye-candy runners doing their before-work bridge circuits. How envious they would be to know that I’m undertaking the longest bridge circuit of all! The passing scene’s so fascinating I don’t feel a trace of fatigue until well past the BU Bridge.

7:40 a.m. Charles River Basin

7:40 a.m. Charles River BasinThe narrowest, ugliest portion of ambulating the Charles is from BU to Harvard. The sidewalk’s a mere four feet wide. Cars whiz by on Soldier’s Field Road. The Mass Pike looms overhead. I will away all distraction by singing Mary Chapin Carpenter. “What If We Went to Italy?” Definitely preferable to Allston.

Just after nine. I turn left on North Harvard Street; pick up bananas and chocolate at Trader Joes. 36,000 steps: already a personal best. I return to the river and continue west. The landscape opens up, but the number of passersby dwindles. My thighs are sore. My shins are taut. My feet begin to complain. Buckle up! I command my body parts. I croon Paul Simon against my irritations all the way to Watertown Square.

9:52 a.m. A Pastoral Stretch of River

9:52 a.m. A Pastoral Stretch of RiverA stretch of river side I’ve never walked. The foot path is lush and shady. The day turns warm. I’m down to shirtsleeves. Early on, I’d pegged the McDonald’s on California Street in Nonantum as a place to caffeine-up. A short detour off the path. I order my Diet Coke, sit down, and check the pedometer: 50,031 steps at 11:23 a.m. What a roll!

When I stand up to get a refill I feel stiff. I sit some more. I get up again. Stiffer yet. I disregard my body’s signals and reason that I’ll loosen up on the trail. I return to the river and continue west.

Suddenly, there’s lots of folks along the path. All old. All speaking Russian. Their faces come at me: half-funny; half frightening. I press on.

12:07 p.m. Natural Path in Newton

12:07 p.m. Natural Path in NewtonThe landscape becomes more natural. Asphalt devolves into dirt. Some stretches are so quiet I can’t hear any cars. The day turns hot; I’m thankful for shade. I reach Waltham Center at 60,000 steps. Ignore any distress my lower body proclaims. I plow on.

12:50 p.m. Waltham Waterfall

12:50 p.m. Waltham WaterfallBeyond Waltham, the river path turns spotty. There are intermittent stretches of city street. I find an overlook bench, eat a few bananas, tell myself everything is fine. But take note that my pace is slowing. A lot.

I rise, stiff. I put one foot in front of the other. My feet rub in my shoes. I consider changing into my fresh socks. But I don’t. I’m not hungry or thirsty or dizzy. But I am feverish. And I keep losing the river. It’s a lot of effort to just keep walking. One foot, then another. My steps are so short, I’m hardly going anywhere. I check the time and realize, I’m not making any. Suddenly I’m back in Newton, in an industrial area, no less. I have lost the river. Nothing is recognizable. I am afraid to stop and rest; I might lack the will to get going again. I stand in the mid-day sun. Dazed. I admit to myself, “You have hit the wall.”

There’s a busy road ahead. Moody Street, leading back to Waltham Center. My spirit wants to ignore it. To turn away. To keep walking. To find the river. I can be foolish, but I am no fool. It’s time to quit. So I trundle back to Waltham Center in search of a bus or a train.

Lucky me. The commuter rail banner announces a train in two minutes. I hobble aboard and roll to Waverly, where I switch to the 73 bus, which deposits me a few blocks from my house. I baby step my tender feet, and arrive home at 3:18. Exactly twelve hours after I left.

When I tell my housemate what I’ve been up to, he rolls his eyes. For good reason. “It’s the first time you’ve tried it. Maybe, if you practice…”

“No way! I’m never doing this again.” Lactic acid throbs my legs. Blisters spear my every step. I crawl upstairs. Force myself into the tub to soak my feet. Lie flat on my bed for an hour.

Final pedometer reading: 30.6 miles; 67,096 steps.

4:06 p.m. Pedometer Reading

4:06 p.m. Pedometer ReadingMy mind filters back to college, when I completed the 20-mile Walk for Hunger in under five hours, then sauntered home afterward. Today, I feel like a loser. Thirty miles annihilated me. I know, intellectually, that its foolish to compare my 21- and 69-year-old selves. Still, physical decline is an ugly thing.

Next day I am sooo stiff and sooo sore. But I manage. Wednesday’s a bit better. By Thursday, the legs are fine; my blisters shrink. As my body regains confidence, the pain of my final 17,000 steps dissipates, and the joy of the first 50,000 lift my spirits. I stop feeling bad about only reaching 2/3 of my ludicrous goal. Instead, I celebrate that I walked twice as far, twice as many steps, as any single day in my pedometer era.

If David Sedaris ever follows his dream and walks 100,000 steps in a single day, I’m sure it will make for a humorous essay. As for me: I’m never trying to do that again.

Actual Route: Waking in Red, Public Transit in Green

Actual Route: Waking in Red, Public Transit in Green

May 22, 2024

Memorial Day

This is a reprint of an essay from Memorial Day 2012. Unfortunately, it all needs to be said again, and again.

Memorial Day has always struck me as a holiday in desperate need of a root cause analysis. We honor our war dead, who deserve to be honored, but we fail to ask the deeper question, “Why are there so many of them, and why do we continue to have more?”

I have an idealist viewpoint on war—I am against it, without exception. If we suggest that this war is just or that war is necessary, we capitulate to the fantasy that war can accomplish some good. War occurs when all else fails, but as long as war is an option, we excuse ourselves from the work required to achieve peace.

As long as war is an option we can talk of justice but insist our point of view prevails.

As long as war is an option we can talk of respect but consider our own country superior.

As long as war is an option we can talk of communicating but we won’t have to take the difficult walk in another man’s shoes to understand his point of view.

We love war, even more than we love to say we are for peace. We are violent creatures, our capacity to destroy is incredible, fascinating really. We do not weigh war’s outcome realistically because we believe the virtue of our cause will tilt the outcome in our favor. Whether we are the rebel or the establishment, each side finds precedent to support his cause. War can smile on the light-footed and inspired, as it did when the Minutemen beat the Hessians in 1775 or the Vietnamese whooped us back nearly two hundred years later. Other times simple “might makes right” prevails. After we pummeled Dresden with thousands of bombs, and Hiroshima with just one, we brought our enemies to heel.

We also love war at a personal level. War is the ultimate adolescent activity, raging action, reckless and liberating. No one ever thinks they are going to die in a war; if they did they would not go. We always think we are invincible, the other guy will die. But sometimes the other guy kills us, and though it is tragic, we die heroes, our deaths count for something, we exit this earth at the height or our virtue, and are honored forever. We make an early, but glorious, exit.

As a child, Memorial Day included a ceremony at the high school stadium with a military procession, a twenty-one-gun salute, and tri-folded flags. It did not stir me. For years I did nothing, pretending Memorial Day was nothing more than a calendar glitch for a long weekend. Then a few years ago the City of Boston began a simple, stunning Memorial Day tribute that touches me deeply. On a rise in the Common, volunteers plant small American flags. There are over 33,000 this year, representing every Massachusetts soldier killed since the Civil War.

Every year I am discouraged because the number of flags keeps growing. But every year I also find hope in the sea of dense packed red, white and blue flags. The individual colors merge, like pointillist dots of an Impressionist painting. The flags lose their unique identity, the flags lose their national symbolism, and the hill becomes a graceful sea of purple.

I doubt the day will come when the people of this earth understand that our commonalties are more important than our differences, that nations and ethnicities and religions do more to separate us than to unite us, and that our best future is the one that makes a seat at the table for everyone. In the meantime I choose interpret Boston’s inspiring tribute to dead soldiers not as a collection of individuals lost to us in war’s folly, but as a beacon of what the world might look like when we lay down our arms and move forward together.

May 15, 2024

All the Privilege I Cannot See

Image Courtesy of MAX

Image Courtesy of MAXI can’t seem to get Alex Edelman’s Just for Us out of my head. I keep digging beneath the comic surface of his sometimes naïve, always humorous, wonderings about whether this fair skinned Orthodox Jewish man-child is actually white.

One particular bit, towards the end of the show, resonates strong. The day after Alex has been kicked out of the white supremacist meeting, in a bravado solo enactment of both sides of a telephone conversation, Alex’s friend calls him out. Of course Alex is white. The whole episode is the height of white privilege: to assume that you, a Jew, could walk into a meeting of white supremacists and think, “This will probably be fine.”

The line, delivered in a sing-song voice with a flip of the wrist, is hysterical. But the serious undertone lingers. That so often, privilege is more than simply having more of everything. It’s all that we take for granted. All the bennie’s we can’t even see.

I live at the top of the food chain: a healthy, affluent, educated, white male. I know, I know, officially I can claim membership in a minority. But I think being gay doesn’t quite count because, most often, I get to decide whether to play the gay card. So it doesn’t carry the same oppressive weight as being Black or Brown or female or disabled, or any other minority status that reveals itself before the first introduction is made.

I’m not about to crash a white supremacist meeting anytime soon. But I could. In fact, there are very few places I can’t go. For over twenty years I designed health care facilities all over the country. I went into emergency departments, ICUs, and operating suites to take photos or measurements or observe processes. Not once—never once—did anyone, in any hospital, ever question me or my purpose. I was polite; I’d introduce myself to the unit secretary, explain my mission. But dozens of other people saw this non-employee walking around supposedly secure areas without any idea of my purpose, yet no one ever bothered to question. Because I looked like I belonged. I did it for years before I realized: Wow! Not everyone gets this privilege.

Over time I became more aware of the privilege I cannot see. I was ‘woke’ before it was a thing, and I still find it usefully humbling to appreciate what’s easily taken for granted, even as ‘woke’ has been cancelled, or pronounced dead, or whatever.

Image Courtesy NBC Sports Boston

Image Courtesy NBC Sports BostonLast month my daughter—a huge Celtics fan—was all excited that the March 18 game had been televised by an all-female team of broadcasters as part of Female Empowerment Month. “That is so awesome. For girls to see these women doing the whole thing. I never saw anything like that.

I was floored by her intensity. Anyone who knows Abby knows she is a tornado of empowerment. I’ve never had the slightest doubt that she’s capable of anything—and she knows it. The whole, “children need to see themselves reflected in positions of influence” argument always rang hollow in me. Until I heard Abby explain how meaningful it was to her to see women broadcast a game she had always, always, seen delivered by men. Duh. Of course I never thought it was a big deal to see role models who looked like me. Because they always did.

I don’t buy that the way to accept all we cannot see is by trying to experience others’ realities. I’m never going to know what it feels like to be transgender or disabled, to be obese, or addicted, or date-raped. It would be disingenuous of me to pretend. What I can do is to hear people’s stories, and give credence to the challenges they encounter. And if a person says they’ve been discriminated against, or that they feel oppressed, or they feel blessed, I must take them at their word.

Which brings me to an odd paradox of bias in my personal empathy. The more divergent a person is from me, by whatever psycho-social-economic profile, the greater understanding I offer, the more I accept their difficulties as described. I would never contest the tale of a transgender Native American or a Haitian immigrant. I accept their stories as their truth. But the more a person mirrors my own life and experience, the less compassion I extend. I know a healthy, college-educated, middle-aged, white, gay guy who stopped working at age fifty, miscalculated his retirement needs, and has ended up in public housing. Certainly not the first—or last—person to ever do such a thing. Yet, I don’t feel empathy for him. Rather, I feel anger. Because, hell, if I managed to hold my nose to the grindstone long enough to keep off the dole, why can’t he? It’s cruel of me, I know. I don’t enjoy being righteous and unforgiving. But for a guy with so many of my same privileges to be—lazy—sticks in my craw. The label ‘freeloader’ festers on my lips.

Perhaps I’ve overshot the mark, holding more empathy for lives I cannot fathom over those I can easily compare. Alas, such is the ongoing challenge of our world, whether writ large or small. For our society, to get to the point that having an all-female broadcast team is no big deal; to actually get to the point that we don’t even need to have ‘Female Empowerment Month.’ For me personally, to bring all the privilege I cannot see into the light, to question constantly what and how I think of others, and to squelch the instinct to judge, in the spiral pursuit of trying to be a more generous human.

May 8, 2024

Alex Edelman: Just for Us

All images taken from Theatrical Program and MAX trailer

All images taken from Theatrical Program and MAX trailerYou haven’t seen comedian Alex Edelman’s MAX special, Just for Us? You must.

I first read about Alex a few years ago, in a profile of the Brookline-born comedian, so when his special appeared in my MAX queue, I hit play. For ninety minutes, I howled. Next night, I watched it again, and I laughed tears. This weekend, I watched it a third time, and roared all over again. He is simply the funniest stand-up comedian I’ve ever seen.

Technically, Alex doesn’t do stand-up. It’s more run-around-in-circles. The guy is one nervous nebbish, who rates the Guinness Book of World Records for most miles of anxious pacing across a single stage. He’s disorienting at first, but once you get lulled into his motion, you’re entranced.

In this moment, with the Middle East more fraught than ever, it’s tough to imagine how a comedy skit whose overarching scenario is a Jew crashing a meeting of white supremacists could land well. Yet somehow it does. Part of the charm, for me, is the exquisite structure of the piece. Something that becomes clearer on second and third viewings. Yes, Alex Edelman does go to a meeting of white supremacists in Queens. Yes, he infiltrates them with naïve bravado. Yes, he gets outed as a Jew. And yes, his rom-com fantasy with an alluring neo-Nazi woman goes down in flames. But in between these bizarre plot points, he touches on gorillas who use sign language, Prince Harry’s cocaine habit, the ridiculous Olympic sport ‘skeleton,’ and Donny Osmond’s star turn on Broadway. There are so many detours, so deliciously woven, that we simply waft over the improbability of the main event. Alex triumphs in creating something completely Jewish that transcends the ugly politics of our moment. And also manages to tie all the inane elements into a satisfying, still humorous, ending.

Just for Us includes plenty of silly trivia; the man tells us straight out his affection for bad jokes and then revels in how much he gets us to laugh at them. Still, like all good comedians these days, Alex manages to infuse his jokes with social commentary. But unlike Hannah Gadsby or Mark Moran, or the uber-relevant Trevor Noah, Alex Edelman never lets his politics overshadow his primary objective: to land the joke.

Underlying the structure of the show is the fundamental question: is a Jewish person white? My first reaction is, of course. And yet, Alex clarifies that Jews are certainly not as white as, say, Boston Brahmins (who get their call-out during the monologue). Certainly, white supremacists don’t consider Jews to be white. The Nazi’s despised Brown and Black people; they killed homosexuals and gypsies simply for existing; but the genocide they leveled against Jews has earned its own name in history: The Holocaust.

Ouch! That last sentence is much too heavy for a puff piece on Alex Edelman. And yet, that truth exists beneath his buoyant hysterics.

Watch Just For Us. It is so much funnier than I am.

May 1, 2024

Building Our Way to Equity: A Convenient Fallacy

Over the last dozen years or so, I’ve watched my small, wealthy, city of Cambridge MA grapple with how to create a more resilient and equitable community. How to provide more affordable housing. How to encourage more sustainable transportation. And the response to these problems is always the same: build. Build more bike lanes, separate them from cars, raise pedestrian crosswalks. Build more housing, mandate affordable units. Build. Build. Build.

New bike lanes with granite dividers make Huron Ave less flexible

New bike lanes with granite dividers make Huron Ave less flexibleWe spend millions ripping up and realigning streets to enhance our bicycle/pedestrian infrastructure. Yet the relationship between vehicle drivers, cyclists and pedestrians remains tense, and a local pedestrian or cyclist still gets killed every year. Why? Because we’re trying to build our way out of the problem instead of addressing the behavioral changes that would actually create a safer cit

We are all-in on spending money for pedestrian ‘improvements,’ but we don’t actually enforce the rules that will make pedestrians safe. Since Cambridge adopted Vision Zero in 2016, the city speed limit has been reduced to 20 miles per hour. Hand-held phone use is prohibited while driving. But I’ve never seen those laws enforced. Recently, I entered the crosswalk on Concord Ave. State law requires a vehicle to stop before any pedestrian in the cross walk. But no law can protect me from two tons of velocitized steel, and so when I stepped off the curb and signaled intent to cross, I hesitated to ensure the approaching car actually stopped. A Lexus streamed through, at more than twenty miles per hour, the driver chatting and holding her phone. Regardless what the law says, if I’d exercised my right-of-way, I’d be dead.

New residential construction at Alewife, courtesy BLDUP

New residential construction at Alewife, courtesy BLDUPOur build, build, build approach to housing is even more disingenuous. More new housing units were built in Cambridge in the decade of 2010-2020 than any time since the 1920’s; thousands of condos; millions of square feet of new construction. Our population increased—some—but the new units did not absorb the increased demand, nor come anywhere close to meeting our future demand. Add in the reality that, unless a dwelling unit in Cambridge is subsidized, it’s unaffordable to anyone without a top income.

How is it that we can build so much and not dent housing demand? Because family sizes are shrinking, so we have fewer people in each dwelling unit. Because the city has long history of two and three family dwellings, many of which are now being converted into singles. Because the city has restrictive zoning that makes ancillary dwellings difficult. Because we limit congregate living. Because we are unwilling to upset any aspect of the status quo—i.e. current homeowners and voters—in order to achieve broader objectives.

Park Ave with two-families turned into singles or demolished for new single family houses

Park Ave with two-families turned into singles or demolished for new single family housesThe Cambridge City Council is a dedicated and responsive body—usually. Yet when I wrote to each of my councilors and outlined five ways we could both increase the city’s population and provide more housing opportunities by better utilizing our existing housing stock, not one of them even responded. New housing units bring in additional tax revenue without threatening their constituents, but rethinking our existing stock to shelter more people without new construction upsets existing, entrenched, Cambridge residents without bringing in any new revenue. Viable, sustainable change for our city: dead on arrival.

We will never build our way to an equitable society as long as the general needs of the many take a backseat to the wealthy few. As long as the rich and entitled find favor with the City of Cambridge; as long as they can motor as they please, unhindered, and turn two and three family houses into grand singles, as long as the clout of money trumps the lip service of fairness, we’ll never achieve the equitable society we proclaim to want.

April 22, 2024

This Earth Day: Do Something that Hurts…Until it Feels Good

Ask any person if they are sustainable and the answer is a resounding, “Yes.” After all, we’re all good people, and we want to save the earth, so we do our part. This one recycles beer cans. That one installs a set-back thermostat. The other guy rode the subway last week. Hooray! We’re all sustainable!

Of course, the accurate response to the question is, “No.” Since there is no agreed-upon definition of what constitutes “sustainable” we are all free to interpret it as we like. Yet by any meaningful measure, none of us live sustainable lives, giving more to our planet than we extract from it.

Almost a decade ago, in an after-midnight conversation more reminiscent of college than middle age, an inspiring Quaker said to me. “The only real measure of what we offer each other, and our planet, is how much sacrifice it entails. Giving up meat if you’re a vegetarian is meaningless. Taking your own bag to the grocery store is little more than a gesture. To do something meaningful demands that we make real change in how we live. The act of sacrifice heightens our consciousness, and acknowledges our appropriate place within the circle of life.”

Allen, a transportation consultant who lives in Portland, Maine, decided to give up flying; no easy feat in a society where people are accustomed to traveling great distances quickly. Some of Allen’s clients were wary of his ‘no-fly’ decision. He became an early adopter of virtual presentations, years before the pandemic and zoom. And if he decided to go to a meeting or conference beyond the Northeast in person, he adapted to accommodate days of travel.

Allen knew the environmental benefits of his commitment wouldn’t be noticeable until the number of non-flyers scaled up. But he found immediate, personal upsides. He learned to schedule his time more generously. He became all-around less hurried. Allen’s life got simpler.

I met Allen in May 2015, on the second day of what eventually spun into a fourteen-month, 20,000+-mile bicycle ride to every state in the continental US. He was my first warmshowers host, the first of many folks who challenged me about how I lived, even as I was living a life very different from most Americans.

Along the journey, in Nebraska, I gave up my two-coke-a-day habit. In California I decided to longer purchase or cook meat. When I got home I decided to see how long I could last without a car; still haven’t bought one. I turned off the heat in my bedroom on winter nights and added a comforter. I stopped using the gas dryer; I hang my laundry out to dry.

Each time I tweaked my life to accord with an environmental objective, my mind sizzled with objections. That I needed the bubbles and the caffeine; that I would crave hamburgers; that I was too busy to take the bus; that I’d catch a winter cold; that New England doesn’t offer enough sunny days to dry clothes.

But every time, over time, my objections withered and I came to appreciate—make that enjoy—a new pattern of my life. These days, I reserve cokes for marathon cycling trips, and they taste so much sweeter than when I downed them every day. I don’t miss hamburgers or steak at all, though sometimes, in a heavy-meat-on-the menu restaurant, I’ll order chicken and savor every bite. I get a lot of reading done waiting for the bus, and have become completely enamored with our commuter trains. I hate sleeping in a room that’s hot, and love the fresh scent of my clothes.

Nevertheless, when I tote the bins of trash and recycle and compost and garden trimmings to the curb each week, I display to all the world the evidence of my still-unsustainable life.

And so I keep looking for ways to tread more lightly on this earth. I haven’t made Allen’s sacrifice to forego flying completely, but I don’t fly distances under 1000 miles. Which means that New York, DC, even Chicago, now lie a bus or train-ride away in my mind. Last year I started a new, somewhat unsavory, environmental endeavor. I use my urine as fertilizer. It takes time to collect, ferment, and distribute. It was a hassle when I started. Now it’s just part of my routine. Meanwhile, our water bills have gone down, and my gardens are flourishing.

I don’t know what cockamamie sustainability practice I’ll normalize in my future, but I’m no longer put off by the prospect of, “that will be too hard,” or “that won’t make any difference.” As one in eight billion, I now my statistical contribution to extending our life on this planet is seconds, at best. But each individual’s seconds saved from extinction can multiply to minutes, hours, even years.

Meanwhile, every time I do something that hurts in service to the planet, I find that the hurt dissolves pretty quick, and is replaced by the satisfaction that maybe I’m doing something useful. And that something feels fine.

April 17, 2024

The Simple Beauty of Following Right-of-Way

It’s Spring! The weather is warming, the cyclists are swarming, and motorists are alert to us everywhere.

As a guy whose primary means of transport for over fifty years has been my bicycle, I appreciate how turf battles over pavement take a breather this time of year. Perhaps, with so many cyclists filling the bike lanes, it’s difficult for drivers to begrudge us the blacktop that spooled empty through the winter. Perhaps it’s simply that improving weather improves everyone’s mood.

Still, the ongoing tension between cyclists and drivers—and how we share pavement—persists.

In theory, everyone loves cyclists. Urban descendants of cowboys, pedalers are free-spirits in fresh air; integrating fitness and honoring the environment as we go about our day.

In fact, drivers hate proximity to actual cyclists. Folks encased in massive, powerful, potentially destructive vehicles get nervous around nimble, vulnerable bicycles. They’re uncertain how we’re going to move, yet keen to the knowledge that pressing their pedal foot too hard could kill us. Meanwhile, the libertine impulse in many cyclists induces us to run stoplights, weave lanes, and travel in the wrong direction. Thereby validating driver’s suspicions.

Easing tensions between cyclists and motor vehicle drivers involves rethinking our relationship in both directions.

Cyclists: reframe your view of the road. Instead of approaching an intersection by figuring, “I can dash across before that guy hits me,” consider, “Will accelerating distress the oncoming driver?” Every time you reconsider an impulsive burst by acknowledging its effect on others, you will cycle more prudently.

Drivers: treat us like any other vehicle on the road. Give us space. Slow down. Don’t honk unless we are doing something wrong. When you have right-of-way, take it, carefully. When you don’t have right-of-way: yield.

The rules of our roads are quite simple: stay right; pass left; obey signals and signs; yield to oncoming traffic before making turns. When everyone—in every form of vehicle—obeys these rules, traffic flows smoother and safer.

During this benevolent time of year, I find many motorists abandon these basic rules in dealing with cyclists. Instead of following right-of-way protocol, they go into auto-yield. Perhaps they are trying to be nice. Perhaps they just want us gone. Regardless, the result creates increased frustration for everyone.

Often, when I slide toward the middle of a multi-lane road, slow down, and put out my arm to indicate a left turn, a well-intentioned oncoming driver slows, stops, and waves me on. Unfortunately, they’ve just blocked my view of any vehicle coming up on their right. So, I don’t move. I wave them on. They signal back, more emphatically. Then they get aggravated, sometimes even roll their window and decry my ungratefulness. Meanwhile, I’m straddling my bike in the middle of the road. Vulnerable, to be sure, but in less danger than crossing the yellow line without determining all is clear. Which I can’t do until the well-intentioned driver moves out of the way. Thus, another cyclist/motorist interaction turns sour.

Drivers, please, know that treating a cyclist as an exception to the rules of right-of-way worsens the dichotomy between us. Grant us the full rights-of-way enjoyed by other vehicles (which happens to be the law in Massachusetts and every other state). But also exercise the right-of-way when it is yours. We occupy different vehicles, but our anomalies do not require special consideration.

Cyclists, please. Know that the rules of the road apply to us as well as motorists. These rules may seem onerous for the light and agile creatures we are, but the same rules have to apply to every vehicle on the road.

When we all follow right-of-way, taking and yielding our due, we grant each other the highest form of mutual respect.

April 10, 2024

Wanted: Our Joseph Welch in 2024

Joseph Welch may not be a household name, but on June 9, 1954, the Boston attorney made an invaluable contribution to our nation’s democracy when he uttered the famous words, “Have you no sense of decency sir?” Overnight, the McCarthy era came to an end.

Joseph Welch (left) and Joseph McCarthy courtesy Bettmann/Getty Images

Joseph Welch (left) and Joseph McCarthy courtesy Bettmann/Getty ImagesJoseph McCarthy, Senator from Wisconsin, soared to public attention in 1950 when he alleged that hundreds of communists had infiltrated the State Department and other federal agencies. His anti-communist campaign struck the heart of Cold War America’s fears. In 1953 McCarthy became Chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, a platform that provided him singular focus on alleged communists. In both public and private hearings, He accused hundreds, called scores of witnesses, alienated the democratic members of the committee to the point they all resigned, and called impromptu or remote hearings that made it difficult for even his Republican peers to attend. McCarthy often held hearings solo, along with his trusty council, infamous attorney Roy Cohn.

In 1954 McCarthy picked a fight with the US Army, charging them with lax security at a top-secret facility. The army countered that McCarthy had requested preferential draft treatment for one of his aides. Joseph Welch represented the army during thirty days of publicly televised hearings. Before Watergate. Before Ira-Contra. Before Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill. Before Benghazi. Before Kavanaugh, Cohen, and Mueller.

Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn, courtesy YouTube

Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn, courtesy YouTubeOn Day 30, with his back against the wall facing a deadline to produce the 130 names of purported communists, McCarthy accused Attorney Welch’s associate, Fred Fisher, of belonging to the National Lawyers Guild, the legal arm of the Communist Party. It was a familiar McCarthy ploy—to distract deadlines and facts by planting fear with more accusations. But Joseph Welch did not respond by crumbling.

Joseph Welch knew that Fred Fisher had belonged to the National lawyers Guild in his youth. He and Fred had predetermined that Fred should not be involved in this hearing. But McCarthy’s out-of-left-field accusation on national television infuriated Welch to rise above legalese with an emotional plea that changed the mindset of our nation:

Until this moment, Senator, I think I have never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. Fred Fisher is a young man who went to the Harvard Law School and came into my firm and is starting what looks to be a brilliant career with us. … Little did I dream you could be so reckless and so cruel as to do an injury to that lad…

When McCarthy doubled down with more attacks on Fisher, Welch plunged his rhetorical blow:

Senator, may we not drop this? We know he belonged to the Lawyers Guild … Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?

The parallels between June 1954 and today are uncanny.

First there is the obvious: that after Roy Cohn cut his fangs on Joseph McCarthy, he became a prominent advisor to Donald Trump.

Donald Trump and Roy Cohn, courtesy The New Yorker

Donald Trump and Roy Cohn, courtesy The New YorkerSecond, there is the strategic. Just like McCarthy, Trump is long on accusation and heavy on invoking fear. When pressed, his response is always: double down, deny, and reaccuse at a higher level.

Third, there is the clash that so-called saviors of the common folk stir up against the educated elite with their established institutions. McCarthy began his allegations against the State Department and took his last stand against a Harvard grad. Trump supposedly battles the ‘Deep State’ (though Federal employment grew under his Presidency) and any Ivy-league school (though Trump attended one).

Finally, is the reality that neither Joseph McCarthy nor Donald Trump has any sense of decency. McCarthy used the term ‘communist’ to demean other human beings. Trump uses blunter words: Nazi, vermin, rapists.

But the most important, and stupefying, parallel between 1954 is not between McCarthy and Trump. It is between us—then—and us—now. How have we, as a nation, allowed these two men to capture our attention, and hold it, spellbound? In the early 1950’s Joseph McCarthy made headline news again and again. In our own era, we have allowed Trump to dominate our media for over a decade. The result of bestowing this influence upon him is that we have become meaner, more divisive, more tribal, more prejudiced, less informed, and more skeptical.

In the early 1950’s McCarthy’s communist accusations fed into our national anxieties, and exacerbated them. In the 2010’s and 2020’s Trump’s dark vision of a dangerous world that requires a strongman leader with unlimited authority, feeds our own fear that the world is too complicated for something as naïve as democracy. Besides, democracy requires real effort on the part of every citizen to succeed, while a strongman promises to relieve us that load, without numerating the many freedoms we will lose in the process.

Yet, in 1954, a relatively unknown, unelected citizen was able to halt Joseph McCarthy in his tracks. By June 7, 1954 McCarthyism was dead. McCarthy was sanctioned by the Senate, ostracized by his party, and ignored by the Press.

Who is willing—and able—to do that today? Republicans elected to high positions in the past: George H.W. Bush, Mike Pence, Dick Cheney, have come out against Trump, to little apparent effect. Jack Smith’s indictments don’t appear to nudge Trump’s popularity. Nor E. Jean Carroll’s successful suit; nor Judge Engoron’s required bonds, not even Trump’s inability to raise the cash he’s so often boasted about in order to pay the bonds.

We Americans have received more than enough warnings—and evidence—to stop the disaster of Donald Trump and turn the man away. And yet we don’t do so.

One hallmark of the MAGA creed is that it harkens to a better time in America. That time, fantasy though it may be, is usually the 1950’s, a period of unprecedented national identity, economic growth, and international dominance: if you were a white man. What the MAGA-folk never invoke is that during that same decade the American populace woke up—quick—from a dangerous illusion, and righted their course.

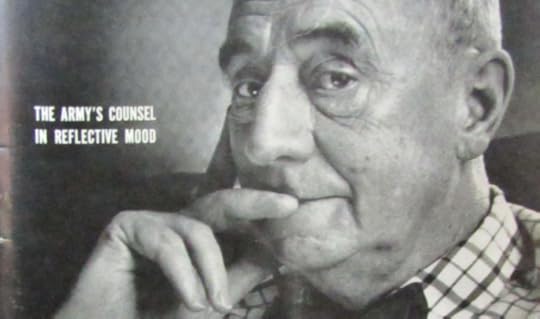

Joseph Welch on the cover of LIFE Magazine June 26, 1954

Joseph Welch on the cover of LIFE Magazine June 26, 1954I say we emulate the 1950’s all over again. Snap out of our fascination with Donald Trump. Ignore him. Censor him. Maybe even him send him to jail. But please, please, don’t elect him.

Mr. Welch 2024: we are waiting for you to bring us to our senses.