Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 778

May 15, 2016

Donald Trump is not an LGBT-friendly candidate: His presidency would be a disaster for human rights

Donald Trump (Credit: AP/Carlos Osorio)

Donald Trump has an answer to the right-wing debate over where transgender people should be able to go pee: Leave it up to the states to decide.

The billionaire CEO, who is currently the last man standing in the GOP presidential race, told ABC that trans equality is a “states’ rights issue.” In a Friday interview, Trump was asked about a pending statement from the Obama administration that will urge schools and universities to allow trans students to use the facilities that most closely correspond with their gender identity. The federal government will reportedly outline this stance in a 25-page document that, according to the New York Times, will be sent directly to public school administrators. Trump responded that he doesn’t believe top-down action on the issue is required. “Well, I believe it should be states’ rights, and I think the state should make the decision,” he said.

Donald Trump has long been applauded for a relative centrist stance on trans issues, especially in contrast to the other Republicans who, until recently, were running against him. Sen. Ted Cruz has long been an outspoken opponent of LGBT rights. During his presidential campaign, Cruz came out swinging against the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision on marriage equality, which made same-sex unions legal in all 50 states, and said he would not endorse it, calling the ruling “disastrous,” “tragic,” and “fundamentally illegitimate.” Cruz has taken issue with gay pride parades and has said that providing affirming bathroom access for trans people “opens the door for predators,” even though numerous research studies have proven that assertion to be a myth.

Trump’s recent statement, however, shows that he’s no LGBT rights hero, either, and he needs to stop being patted on the back for being slightly less terrible than other Republicans on the issue. In truth, there’s absolutely nothing moderate about his so-called support for the trans community, which he has already walked back once. By supporting the forced deportation of millions of undocumented workers across the U.S., his policies will also affect trans immigrants, many of which are already vulnerable to mistreatment. His presidency would be bad for queer Latinos, queer Muslims, and every other marginalized community in the United States. Whether you’re a person of color or literally anyone else who isn’t a wealthy, loud-mouthed businessman, Donald Trump is not your friend.

Trump’s Friday statement would be a huge step backwards from his earlier condemnation of legislation like House Bill 2 if he hadn’t already taken a step back. On March 23, North Carolina pushed through legislation that forces its trans residents to use the bathroom that corresponds with the sex they were assigned at birth, not their gender identity. During an April town hall event on NBC’s “Today” show, Trump argued that HB 2 is simply unnecessary. “There have been very few complaints the way it is,” he said. “People go. They use the bathroom that they feel is appropriate. There has been so little trouble.” He was right: There’s never been a single reported case of a trans person harming someone else in a public restroom.

In response, Ted Cruz quickly lashed out at Trump for his stance on the issue, saying that his opinions make him “no different from politically correct leftist elites.” Cruz continued, “Today, he joined them in calling for grown men to be allowed to use little girls’ public restrooms. As the dad of young daughters, I dread what this will mean for our daughters—and for our sisters and our wives. It is a reckless policy that will endanger our loved ones.” Trump, rather than standing his ground, would take a different tack—later the very same day. In an interview with Fox News host Sean Hannity, Trump said: “I think that local communities and states should make the decision. And I feel very strongly about that. The federal government should not be involved.”

His Friday statement is, more or less, the same argument spiced up with a bit of old-school racism. The phrase “states’ rights” is an oft-employed code word used in defense of racist policies; it was, in particular, a favorite term of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Davis claimed that the issue of slavery should be decided by individual states, not through federal government interference, such as in a February 1860 resolution presented to the Senate. It argued that the “union of these States rests on the equality of rights and privileges among its members.” The states’ rights argument has since been used to oppose marriage equality (including in a pre-emptive Senate bill introduced by Ted Cruz in February 2015, in anticipation of the SCOTUS ruling) and also trotted out by Cruz during a March GOP debate when asked about same-sex adoptions.

Donald Trump isn’t just engaging in dog-whistle politics. The CEO is also illustrating the fact that he’s not nearly as liberal on LGBT issues as he is often credited to be. Last year, MSNBC’s Emma Margolin called Trump “the most LGBT-friendly Republican running for president.” Back in 2000, the candidate notably supported nondiscrimination protections for LGBT workers, even if it meant updating federal policy on the issue. “[A]mending the Civil Rights Act would grant the same protection to gay people that we give to other Americans—it’s only fair,” he told The Advocate. Even today, that’s a sadly progressive stance: Currently, just 19 states—as well as Washington D.C.—have laws on the books that prevent workers from being fired on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

His support of workplace protections, however, masks the fact that a Trump presidency would be a disaster for LGBT people. Although Donald Trump claimed in 2013 that he was “evolving” on the issue of marriage equality—like President Barack Obama and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have—that has not been the case. Following the SCOTUS ruling Obergefell v. Hodges last year, he tweeted that legalizing same-sex unions was a mistake, one he blamed on the Bush family. “Once again the Bush appointed Supreme Court Justice John Roberts has let us down,” Trump said. “Jeb pushed him hard! Remember!” Since then, Trump has further upheld his support for “traditional marriage.”

That might suggest that his opposition to the freedom to marry for all couples is passive. It is not. As the Huffington Post’s Michelangelo Signorile pointed out, Trump has repeatedly hinted that if he were in the White House, he would work to appoint Supreme Court justices that would nullify same-sex marriage rights. Speaking with David Brody of the Christian Broadcasting Network, Trump had a message for right-wing evangelicals concerned that he wouldn’t take action to overturn the ruling: “Trust me.” He further told Fox News on the subject: “If I’m elected, I would be very strong in putting certain judges on the bench that I think maybe could change things, but they have a long way to go.”

His stance on marriage equality is only part of the issue with a Trump presidency. While Donald Trump’s campaign has largely singled out Latinos and Muslims as wedge issues, these populations also intersect with the LGBT community. Queer people are often portrayed in film and television as being white, but LGBT folks are every race, ethnicity, and religion. A 2013 report from UCLA’s Williams Institute estimated that 1.2 million Latino adults in the United States identify as part of the vast queer alphabet. While LGBT Muslims might struggle for visibility and acceptance, they are part of a vibrant, growing community—with increasing numbers of people coming out every year. This is the same emerging population Trump has suggested be listed in a national database to keep tabs on them.

Since announcing his candidacy for the president last July, Donald Trump has referred to Latino immigrants as “ criminals, drug dealers, [and] rapists.” He has further promised to expel 11 million undocumented workers from the United States, many of which are be queer-identified. In addition, LGBT immigrants—specifically transgender women—face some of the harshest treatment of any detainees in detention centers. Often housed in the general population with men, they face extremely high rates of abuse and even sexual assault. Donald Trump’s policies are bad for all Latinos and Muslims, but it’s trans women who will likely experience the most significant violence in Immigration and Customs Enforcement lockups.

The truth is that as long as Donald Trump’s hate-filled agenda continues to give a platform to white supremacists and bigots, his campaign will provide a safe haven for all forms of discrimination. When Trump won the South Carolina primary in February, research from the Public Policy Polling showed that a third of those who supported him also favored blocking LGBT immigrants from entering the U.S. As The Advocate pointed out, that figure was “nearly twice the percentage of supporters of any other Republican candidate.” For reference, only 17 percent of those who backed Sen. Marco Rubio in the S.C. primary agreed with that same statement.

Trump’s recent stance on “states’ rights” might shock those who believe him to be the lesser evil when it comes to LGBT equality, but make no mistake—his policies are pretty evil.

Secrets of the “Exile” sessions: Drugs, sex and madness as the Rolling Stones took over France

Mick Taylor, Mick Jagger, and Charlie Watts pose during a press conference in Paris, France in 1970. (Credit: AP)

When did Keith Richards take his first hit of heroin?

Even he doesn’t know.

He says it was probably an accident, that he mistook a line of smack for a line of blow at a party at the rag end of the decade. It was everywhere. Cheap, nearly impossible to avoid, an unintended consequence of the Vietnam War. When we opened a channel to South- east Asia, soldiers flowed out and china white flowed in.

Heroin had been a passion of Keith’s heroes—black blues players who’d chased the high until they lost everything. If you’re of a certain temperament, you do things you know are bad for you because without the experience, you can’t emulate the art. To make music with the depth of the masters, Keith had to experience what they experienced, had to touch the seafloor, where the pearl is buried in the muck. When he speaks about his junkie years—“I know the angle,” he told Zigzag magazine in 1980, “waiting for the man, sitting in some goddamn basement waiting for some creep to come, with four other guys sniveling, puking and retching around”—it’s not without a certain pride. Fame removed Keith from the kind of suffering that stands behind the Delta blues. He’d never know cotton shacks or rent parties. He sought that crucial authenticity in debauchery instead.

Heroin was in part Keith’s response to Altamont. He reeled from riot to stupor. He loved how it made him feel—how it answered every question, removed every obligation, annihilated every stare. (“I never liked being famous,” he said.“I could face people a lot easier on the stuff.”) Like prime rib with cabernet sauvignon or creeper weed with high school, junk went perfectly with that bleak, washed-out moment. Vietnam, the streets filled with psychotic vets, LSD cut with strychnine, Richard Nixon in the White House. The shift from the sixties to the seventies was the shift from LSD to heroin. LSD was aspirational. Heroin was nihilistic. The promise of hippie epiphany was gone; only the high remained. Keith came to personify that—the oldest young man in the world; stand him up and watch him play; shoot him up and watch him die.

*

The Stones were in the same condition as the culture, having come to realize, despite all their hit records and sold-out shows, that they were essentially broke. When they asked Allen Klein for more of what they assumed was their money, he sent it grudgingly, in dribs and drabs. Jagger finally reached out to his friend Christopher Gibbs, the art dealer, who put him in touch with the private London banker Prince Rupert Loewenstein. At first glance, Loewenstein, a prematurely middle-aged aristocrat who spoke with a slight German accent, seemed an unlikely partner for the Stones. “My tastes . . . leaned towards Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms,” Loewenstein writes in his memoir.“The name of the [Stones] meant virtually nothing to me at the time, but I asked my wife to tell me about them. She gave me a briefing and my curiosity was tickled.

“Mick slipped into the room, wearing a green tweed suit,” Loewenstein goes on.“We sat and talked for an hour or so. It was a good, long chat. His manner was careful. The essence of what he told me was,‘I have no money. None of us have any money.’ Given the success of the Stones, he could not understand why none of the money they were expecting was even trickling down to the band members.”

It took Loewenstein eighteen months to untangle the contracts and deals. He explained the problem to the band in 1970: Klein advised you to incorporate in the United States for tax purposes; as this new company was given the same name as your British concern— Nanker Phelge (named after their old Edith Grove housemate)— you’ve assumed it’s the same company; it’s not. The American Nanker Phelge is owned by Allen Klein; you are his employees. Royalties, publishing fees—all of it belongs to Klein, who can pay you as he sees fit. This also gives Klein ownership of just about every one of your songs. “They were completely in the hands of a man who was like an old-fashioned Indian moneylender,” Loewenstein writes, “who takes everything and only releases to others a tiny sliver of income, before tax.”

Jagger was humiliated, ashamed. Here was the smartest rocker, the LSE student, being taken in a game of three-card monte. “There was one frightening incident in the Savoy Hotel when Mick started screaming at Klein who darted out of the room and ran down the corridor with Mick in hot pursuit,” Loewenstein writes.“I had to stop him and say,‘You cannot risk laying a hand on Klein.’”

Loewenstein proposed a two-step course of action. One: the Stones immediately sever all ties with Klein. The second step had to do with Inland Revenue, as the British equivalent of the IRS was then called. As Klein had cashed checks from Decca, he never withheld or paid the band’s taxes. The musicians had accrued a tremendous debt as a result. Not only were they broke, they were in danger of being sued. What’s more, the Stones’ earnings—on paper—put them in the top bracket, which in Britain at the time meant paying a marginal income tax rate of up to 98 percent. In other words, the government would take almost everything you made over a certain amount. This made it nearly impossible for the Stones to earn enough money to ever satisfy Inland Revenue. If they wanted to live safely in England, they’d have to move somewhere with a less punishing structure, then make enough money to square themselves. The term for this is “tax exile.”

“My advice is contained in four words,” Loewenstein told Jagger. ‘Drop Klein and out.’”

The Stones broke with Klein in December 1970, then sued for $29.2 million. A settlement for $2 million was reached in 1972, though litigation carried on for years.

As for exile, Loewenstein suggested France. The prince, who had pull with Parisian officials, was able to arrange a deal: the Stones agreed to stay in the country for at least twelve months and spend at least £150,000 per year; in return, no additional taxes would be levied by the French government. Band members began leaving England in the spring of 1971.

Keith and Anita quit heroin before they went into exile. They did it to avoid certain hassles. Being addicted means having to carry drugs, hook up with local dealers—expose yourself in a million dangerous ways. Keith kicked first. Vomited and wept; wept and prayed. He was clear-eyed when he arrived at Gatwick Airport in April 1971, twenty-seven years old, the coolest person walking the planet other than Elvis and Brando, but Elvis and Brando were past their prime, slouching toward late afternoon, whereas Keith was at his apex. In photos taken that day, he has the look of a man used to being looked at. The sharp angles and rock star lines that would later characterize his face had not yet hardened. He carried his son, Marlon. Anita was in London, in the midst of withdrawal. She would join Keith and Marlon in France as soon as she was clean.

A house had been selected for the family in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a port on the Côte d’Azur. Fleetingly small, bathed in boredom and sunlight. Nothing is happening. Nothing has happened, or will ever happen. Exactly what Keith required. I visited the town shortly before my mother died—checked in to a hotel on the harbor, talked to strangers, walked. The ancient streets are steep and shaded by plane trees. There are alleys and storefronts and wine shops that reek of time. In the summer, the squares are picked clean by le sirocco, a wind that originates in the Sahara and covers the rooftops in fine red sand. What you feel in Villefranche is not the Stones but their absence. The world’s most powerful rock ’n’ roll energy had once concentrated here, but that was decades ago. The bars where the boys once drank as the sun went down are long gone. What remains is the silence that you hear as you sit alone in a hotel room after the last song has played.

I hailed a taxi in front of my hotel and asked the driver to take me to the house where Keith and Anita once lived. He had no idea what I was talking about, so I asked him to take me to the house where the Stones recorded Exile on Main Street. Still no idea. So I told him about the summer of ’71, the mansion in the hills, the drugs and the songs. He said “Oui, oui” but still did not know, so I just gave him the address: no. 10, avenue Louise Bordes.

The road wound around the shore and began to climb. The trees made a canopy overhead, a tunnel of leaves. The driver hit the brakes and pointed. There was a steel gate and, hundreds of yards beyond it, a house. I got out and stood before the closed gate, hands on the bars, studying the lawn and fountain, the complicated roof and chimneys, the windows, the front steps, the door. I closed my eyes and could actually feel the warm air turning into a groove, the lyrics drifting across the sky in cartoon bubbles. Then, just as I was about to lose myself entirely, the driver honked.“My boo-boo, monsieur,” he said.“I have you at the wrong address.”

I burned with shame as we went a quarter mile up the road. I got out timidly, but this time certain that I was in the right place. There were the street number and the nameplate. Grand houses, like racehorses, have names. Mick’s country estate was Stargroves. Elvis lived at Graceland. The house in Villefranche is Nellcôte, a mansion in the European style, with porticos, columns, and gardens. I stood with my face to the gate. It was no longer magic I felt, but yearning. I longed to go inside and poke around. As the driver shouted “Non, non,” I climbed the fence and dropped down hard on the other side. I stood there for a long time, listening for alarms and dogs. I’d read that Nellcôte had been purchased by a Russian oligarch. I pictured a goon named Boris, a cell in a provincial jail, the sheriff ’s wife serving me foie gras and Beaujolais.

I walked up the long drive, knocked on the door. Nothing. I looked around the gardens and gates, then lost courage. The driver cursed me when I got back, but in words I couldn’t understand anyway. Besides, I was proud of my transgression. That’s rock ’n’ roll, baby. And I’d gotten a lovely unobstructed view of the house. So I didn’t get inside. So what? I already had a good idea of the interior. The grand staircase, the living room, the balcony that overlooked Cap Ferrat. It had all been described to me in great detail by June Shelley, who, in those crucial months in the early seventies, served the Stones as a girl Friday. She’d been an actress and the wife of the folk legend Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, but was beached on the coast when her (second) husband spotted the ad in the International Herald Tribune. “Wanted. For English organization in the South of France, bilingual, organized woman, salary plus expenses, 25–35 years of age.”

Shelley was interviewed by Jo Bergman, the Stones’ manager, then taken to the mansion.“I confessed on the way that I didn’t know all their names,” Shelley told me.“I knew Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. But I didn’t know the others. So Jo ran them down. She said,‘Bill Wyman, bass player, Renaissance man; moody, doesn’t speak much. Charlie Watts, drummer, blah-blah-blah.’ She described them each in a few words. ‘Mick Taylor, new kid; this will be his first album with the boys. He looks like an angel with blue eyes, round face, blond hair, and worships Keith.’ When we pulled into the garden at Villa Nellcôte, I knew everyone immediately from her description. Bill, Charlie, and Mick Taylor were sitting on the steps. It was like the circus had come to town; there were people everywhere, dogs and kids, trucks, men moving things around. Jo says,‘Hi, guys, this is June, she’s going to be your new assistant.’ They nod, and we go inside.

“What a crazy wonderful house,” Shelley went on.“You went into a long hallway and there were rooms right and left. An old-fashioned kitchen and an old-fashioned study, a partially finished basement that we later fixed up so they could record.”

Nellcôte was built in the 1800s for a British admiral, who spent many melancholic years there studying the horizon through a telescope. The Germans took possession during the Second World War. According to Richards, it served as a Gestapo headquarters. The basement was the setting of unspeakable horrors, which gave the house an appropriate sheen of menace. Dominique Tarlé, a photographer who stayed in the house that summer, spoke of exploring the basement with a friend and finding“a box down there with a big swastika on it, full of injection phials. They all contained morphine. It was very old, of course, and our first reaction was,‘If Keith had found this box . . . ’ So one night we carried it to the end of the garden and threw it into the sea.”

Richards rented Nellcôte for $2,400 a week. He kept on the old staff, including an Austrian maid and a cook affectionately known as Fat Jacques, who was fired that summer for reasons too fraught and nefarious to get into. The first floor became a kind of salon, with musicians crashed in every corner. The second floor remained off-limits, the private preserve of Keith, Anita, and Marlon. Even Jagger didn’t go up.

*

The other band members were scattered across France. Bill Wyman rented a house near the sea. Charlie Watts was in the countryside. Jagger had settled in Paris, where he took on the life of the jet-set party boy. Reeling from the breakup with Marianne Faithfull, he was seen in all the gossips, whispering in the corner of every party, confiding his pain to every beautiful woman. He’d had a torrid affair with Marsha Hunt, the devastatingly beautiful black singer and model who’d become famous in the London company of Hair. That’s her, with towering Afro, on the playbill. The Stones had asked Hunt to pose for “Honky Tonk Women,” but she refused, later telling The Philadelphia Inquirer that she “did not want to look like [she’d] just been had by all the Rolling Stones.” Jagger followed with phone calls, which turned into illicit hotel meetings. In her autobiography, Hunt claims that she was the inspiration for “Brown Sugar.” In November 1970, she gave birth to Jagger’s first child, a daughter, Karis. As in a story from the Bible, this love child, at first rejected, would later become a great solace and balm for her father in his old age.

It was at a party in Paris in 1970 that Jagger met Bianca Pérez-Mora Macias, the daughter, depending on the conversation, of a plantation owner or a diplomat or a wealthy businessman from Nicaragua. She was young but refused to be fixed to an exact number. Here was a rich girl so dismissive of rock ’n’ roll that Jagger could not help but be entranced. Friends claimed that they looked like doppelgangers, twins. That Mick’s love for Bianca was a kind of self-love. Bianca got pregnant early in 1971, and just like that, Mick was sending out wedding invitations. The ceremony was in St. Tropez that spring, soon after the band arrived in France. It was the celebrity clusterfuck of the season. Helicopters buzzed the beach as the paparazzi closed in. Mick chartered a plane to fly his friends from London.“If that plane went down, you would have lost twenty years of popular music,” Anna Menzies, who worked for the Stones and was on the plane, told me. “Bobby Keys was on that flight, Jim Price, Paul McCartney with Ringo. Keith Moon. Peter Frampton, Robert Fraser, Eric Clapton. There was so much booze the plane could’ve flown without fuel!”

The theme from Love Story played as Mick and Bianca walked down the aisle. A reception was held at Café des Arts. It was a rage. Can till can’t. As on the last day. Jagger had hired a reggae band called the Rudies, but everyone got up and jammed. Jade Jagger was born a few months later. Asked to explain the baby’s name, Mick told a reporter, “Because she is very precious and quite, quite perfect.” Mick and Bianca divorced in 1979. I won’t go into that relationship further, because it just makes me sad. Suffice it to say, the marriage is credited with inspiring the great Stones song “Beast of Burden.”

*

Keith and Anita were soon back on heroin. It started with a male nurse who shot Keith up with morphine after a go-kart wreck in which Richards, racing his friend Tommy Weber at a nearby track, flipped his vehicle, chewing his back into hamburger. Appetite whetted, Keith began looking for still more relief—it’s a story hauntingly told by Robert Greenfield in Exile on Main Street: A Season in Hell with the Rolling Stones. One afternoon, Jean de Breteuil, a notorious drug dealer known, because of his suspenders, as Johnny Braces, showed up at Nellcôte. He handed Keith a woman’s compact filled with astonishingly pure heroin. Richards passed out as soon as he snorted it. When he came to, he said he wanted more—a lot more.

By June, life at the house had settled into a strange junkie rhythm. Most days began at two or three in the afternoon. Keith would wake up, yawn, stretch, hack up phlegm, swallow whiskey, reach for pills. He started with Mandrax, a downer that shoehorned him into consciousness. It was a hot summer, often above a hundred degrees. Anita was pregnant. Keith shot up before his afternoon breakfast and did not make his first appearance downstairs until five or six, a gray smack-filled ghost. He spent hours listening to music or playing. At nine, he would go to the basement to work. Like an Arab trader, he slept all morning and crossed the desert at night. He emerged at dawn. If the weather was good, everyone followed him down to the dock, where he kept a speedboat, the Mandrax II. He stood at the wheel as the coast unspooled, crossing the border into Italy, where he’d tie up at a pier and stumble up stone stairs to a bistro for eggs and kippered herring, or pancakes with strong black coffee.

Marlon was eighteen months old. Keith was far older, but a heroin addict is a baby. It’s all about bodily functions and human needs. You cry when you’re hungry. You sleep if you can. You live desperately from feeding to feeding. In this way, Keith and Marlon fell into lockstep, the addict and the kid playing on the beach.

*

Nellcôte in 1971 was like Paris in the twenties. The biggest stars and brightest lights of rock ’n’ roll came to pay tribute, get loaded, and play. People felt compelled not merely to visit but to party, measuring themselves against Keith. Like dancing with the bear, or staying up with the adults, or drinking with the corner boys. Eric Clapton got lost in the house, only to be discovered hours later, passed out with a needle in his arm. John Lennon, visiting with Yoko Ono, vomited in the hall and had to be taken away.

*

Gram Parsons turned up with his girlfriend, Gretchen. He was out of sorts, experiencing a kind of interregnum between lives. His band had broken up; his music was in a state of transition. At Nellcôte, Richards and Parsons resumed the work they’d begun years before, playing their way deep into the roots of American music. It went on for days and days, Gram, twenty-four years old, long-limbed and fine-featured but not quite handsome, sitting beside Keith on the piano bench. Their relationship was intense, mysterious. They connected spiritually as well as musically, loved each other sober and loved each other high. “We’d come down off the stuff and sit at a piano for three days in agony, just trying to take our minds off it, arguing about whether the chord change on ‘I Fall to Pieces’ should be a minor or a major,” Richards said later. If you have one friend like that in your entire life, you’re lucky.

History has been kind to Gram Parsons—the importance of his legacy revealed only in the fullness of time. The tone he worked on at Nellcôte with Keith, the perfect B-minor twang that can be heard on Exile on Main Street, inspired some of the great pop artists of later eras. The Jayhawks, Wilco, Beck—I hear Gram whenever I turn on my stereo. The mood was contagious. Jagger caught it like a cold. “Mick and Gram never clicked, mainly because the Stones are such a tribal thing,” Richards explained.“At the same time, Mick was listening to what Gram was doing. Mick’s got ears. Sometimes, when we were making Exile on Main Street, the three of us would be plonking away on Hank Williams songs while waiting for the rest of the band to arrive.” The country tunes that distinguish the Stones— “Dead Flowers,” “Sweet Virginia”—wouldn’t exist as they do if not for Parsons, who, like any third man, is there even when he can’t be seen.

The Stones, then in the process of signing a distribution deal with Ahmet Ertegun and Atlantic Records, needed to make a follow-up to Sticky Fingers. They’d gone into exile with several cuts in the can, leftovers from previous sessions—some recorded at Olympic, some recorded at Stargroves, Mick’s country house. France was scouted for studios, but in the end, unable to find a place that could accommodate Keith’s junkie needs, they decided to record at Nellcôte. Sidemen, engineers, and producers began turning up in June 1971. Ian Stewart drove the Stones’ mobile unit—a recording studio built in the back of a truck—over from England. Parked in the driveway, it was connected via snaking cables to the cellar, which had been insulated, amped, and otherwise made ready, though it was an awkward space. “[The cellar] had been a torture chamber during World War II,” sound engineer Andy Johns told Goldmine magazine.“I didn’t notice until we’d been there for a while that the floor heating vents in the hallway were shaped like swastikas. Gold swastikas. And I said to Keith, ‘ What the fuck is that?’ ‘Oh, I never told you? This was [Gestapo] headquarters.’”

The cellar was a honeycomb of enclosures. As the sessions progressed, the musicians spread out in search of the best sound. In the end, each was like a monk in a cell, connected by technology. Richards and Wyman were in one room, but Watts was by himself and Taylor was under the stairs. Pianist Nicky Hopkins was at the end of one hall and the brass section was at the end of another. “It was a catacomb,” sax player Bobby Keys told me, “dark and creepy. Me and Jim Price—Jim played trumpet—set up far away from the other guys. We couldn’t see anyone. It was fucked up, man.”

Together and alone—the human condition.

The real work began in July. Historians mark it as July 6, but it was messier than that. There was no clean beginning to Exile, or end. It never stopped and never started, but simply emerged out of the everyday routine. It was punishingly hot in the cellar. The musicians played without shirts or shoes. Among the famous images of the sessions is Bobby Keys in a bathing suit, blasting away on his sax. The names of the songs—“Ventilator Blues,”“Turd on the Run”—were inspired by the conditions, as was the album’s working title: Tropical Disease. The Stones might hone a single song for several nights. Some of the best—“Let It Loose,”“Soul Survivor”—emerged from a free-for-all, a seemingly pointless jam, out of which, after hours of nothing much, a melody would appear, shining and new. On outtakes, you can hear Jagger quieting everyone at the key moment: “All right, all right, here we go.” As in life, the music came faster than the words. Now and then, Jagger stood before a microphone, grunting as the groove took shape—vowel sounds that slowly formed into phrases. On one occasion, they employed a modernist technique, the cutout method used by William S. Burroughs. Richards clipped bits of text from newspapers and dropped them into a hat. Selecting at random, Jagger and Richards assembled the lyric of “Casino Boogie”:

Dietrich movies

close up boogies

The record came into focus the same way: slowly, over weeks, along a path determined by metaphysical forces, chaos, noise, and beauty netted via a never-to-be-repeated process. They called it Exile on Main Street—Main Street being a pet name for the French Riviera as well as an invocation of that small-town American nowhere that gave the world all this music.

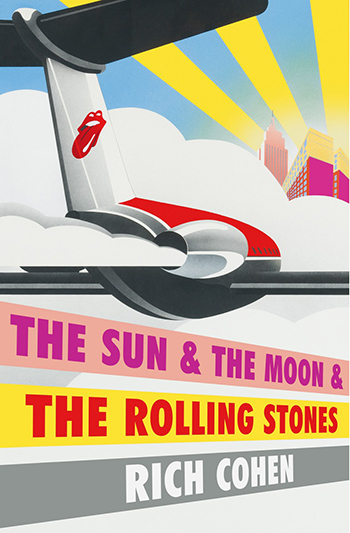

Excerpted from the Book “The Sun & the Moon & the Rolling Stones” by Rich Cohen. Copyright © 2016 by Tough Jews, Inc. Published by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Ayn Rand goes to “Silicon Valley”: The farcical libertarian world of Mike Judge, where corporations are the new soul-crushing villains

"Silicon Valley," Ayn Rand (Credit: HBO/AP)

Two weeks ago, “Silicon Valley” aired a scene that I haven’t been able to get out of my head since. Though it rather unforgettably features two horses engaged in the very loud, wet, and physical act of mating, that’s not exactly what ended up staying with me about it. Instead, it’s the conversation happening between the owner of the mare, a tech company CEO, and his irritating employee, who just happens to be that same company’s founder. Over the past two seasons, “Silicon Valley” has told the story of how awkward-but-brilliant programmer Richard (Thomas Middleditch) created a game-changing data compression algorithm and made it, with fits and starts, into its own company. But at the end of season two, the board of directors in the company he created fired him, wholesale, because he was a pretty shoddy CEO. And in his place they installed Jack (Stephen Tobolowsky), a non-coding business savant a generation older than Richard and his core group of founding employees. (Richard gets to stay on as head of tech.)

Within the span of just one episode (“Two In A Box”), Jack neatly dismantles Richard’s vision—going so far, in a “Monty Python”-esque farcical move, to “pivot” the company from user-facing machine-learning cloud-computing algorithm to B2B, security-focused, literal “metal fucking box.” Richard watches the sales team’s soft-focus promotional video for said metal box—“a rhetorical example of a bad idea”—with waves of disbelief washing over his face, and then in a fit of rage, leaps out of the conference room and into his car, to find Jack wherever he is.

That leads us to the horse-fucking. Jack has paid $150,000 for his mare to be covered by this thoroughbred stallion, and as he watches over the two horses sealing the deal, Richard emerges on the scene. With the backdrop of urgent neighing and gushing fluid, both distracting and carnal, Richard tells Jack that he believes this is a product that can both help the world and make a billion dollars. Jack responds, with the sweetest tones of dulcet encouragement: “Richard, I don’t think you understand what the product is. The product isn’t the platform. And the product isn’t your algorithm. And it’s not even your software. Do you know what Pied Piper’s product is, Richard?”

Richard, torn between encouragement and frustration, thinks he knows the answer. “Is it me?” he stammers, pointing to his chest, just above his heart.

Jack practically yelps. “Oh God no. How could it possibly be you? You got fired! Pied Piper’s product is its stock! And whatever makes the value of that stock go up? That is what we are going to make.”

The moment is, quite possibly, the most distilled critique of tech, capitalism, and the American way that I’ve seen—a combination of brutal physical comedy, as Middleditch and Toblowsky are conversing next to a real pair of mating horses, and unvarnished, clear-eyed awareness of how idiotic the type of capitalism we live in truly is, all the way down to its core. Adam McKay’s Oscar-winning “The Big Short” laid bare corporate human recklessness and the greed of playing markets like video games; Judge’s slacker comedy “Office Space” revealed the moral bankruptcy at the core of any regional manager’s bureaucracy. “Silicon Valley” marries the two with the particular brand of do-gooding, disrupting, one-percenter technobabble that has profound effects on our lives from an insular system in a rarefied community with bizarre, meaningless rules.

It was not obvious, at first, that this was what “Silicon Valley” was going to be. Unlike “Veep,” the show’s sister comedy on HBO, “Silicon Valley” is not purely satire. “Veep”’s delivery is joke-driven and cutting, an array of sharp zingers and takedowns deployed one after another, usually from one character to another. “Silicon Valley” is sharp, but its critiques are by and large embedded in the structure of the show. In last week’s episode, for example, “Meinertzhagen’s Haversack,” the protagonists embark on an elaborate plan to circumvent Jack’s authority. But in the final scene, Richard trips over a hose and scatters his top-secret, to-be-shredded plans in plain view of the entire office. This is less a punchline and more a gut-punch; it is not the characters that are funny, it is that all of humanity’s efforts boil down to nothing.

Which is why it’s taken me, at least, all the way to the third season to fully appreciate the dysfunctional atmosphere of the show’s rendition of the tech scene, which is where the show almost entirely derives its humor. From the animated opening credits that depict a San Francisco overrun with logos—which a Bay Area resident would tell you is not so different from what has really happened to that city—to the banal, khakis-and-polos-based wardrobe of the leads, “Silicon Valley” is steeped in its target’s culture. In “Veep,” you get the impression that though all the leads hate themselves, they force themselves through the motions of politics, either because they’re narcissists or masochists. In “Silicon Valley,” the leads are just embracing the madness.

And upon closer examination, especially if you’re not in a tech-adjacent industry, the circus of Silicon Valley really does seem like madness: Surface-level progressive values about identity combined with a ruthless opposition to labor laws and inconvenient community ordinances. Tech billionaires have actually drunk the Kool-aid in believing that creating cell phone apps makes the world a better place; mid-level programmers really did mourn Steve Jobs as if he was a fallen god. The tech industry is so insular and airless that its “thought leaders” are high on their own supply of hot air (produced largely through TED talks, natch).

Given how much is theorized about libertarian values taking hold on real-life Silicon Valley—with arguments both for and against the influence of the original thinkfluencer, Ayn Rand—it is intriguing that Mike Judge, the creator and co-showrunner of “Silicon Valley,” is widely believed to be either conservative or libertarian. (The important thing, as these articles suggest, is that he is not just another Hollywood Liberal.) He has not described himself as either on the record, but in an oft-cited sit-down interview with InfoWars, the site reports:

Judge told Alex Jones that his parents raised him to be a liberal but he doesn’t feel comfortable describing himself as a Democrat or a Republican because the two extremes of partisanship resemble a “religion”. Judge added that he had become “interested in smaller government kind of thinking” since he began building his own projects and was getting “penalized left and right” by the system as a result.

The best example of this scorched-earth cynicism, to the politically minded viewer, is not his seminal MTV classic “Beavis And Butt-Head” or the cult hit “Office Space”; it’s the 2006 film “Idiocracy,” which is back on people’s brains following Donald Trump’s rise to the top of the Republican party. It’s a comedy Judge thought of, he tells the Verge, while waiting in line for the spinning teacups at Disneyland. Two women in dispute over their place in line engaged in a no-holds-barred, “cussing” argument in front of their children. He wondered if the future would not be more progressive, à la Stanley Kubrick’s sleek “2001: A Space Odyssey,” but less. What follows is a story where, one thousand years into the future, only the stupidest people have chosen to reproduce, thus populating the planet with increasing levels of idiocy. To quote Matt Nowak at Gizmodo:

What’s so wrong with this thinking? Unlike other films that satirize the media and the soul-crushing consequences of sensationalized entertainment … “Idiocracy” lays the blame at the feet of an undeserved target (the poor) while implicitly advocating a terrible solution (eugenics). The movie’s underlying premise is a fundamentally dangerous and backwards way to understand the world.

I wouldn’t go so far as Nowak does, but Judge’s vision is unsettling for its breathtaking lack of idealism—its lack of investment in the future of the human race, really. Rather than use idiocy as a call for greater understanding, awareness, or compassion, Judge is content with unleashing cynicism without obvious recourse. “Office Space”’s solution is literally to burn it all down (via carefully cheating it, in the process); “Idiocracy” presents a world where it already is burnt down, more or less.

Which is to say—whether or not Mike Judge is a libertarian, he does appear to have created a libertarian body of work. Except that instead of government intervention, his bugbear is mindless corporate bureaucracy; not exactly Ayn Rand, but echoing her vilifications of mediocrity and communitarianism. In “Office Space,” Judge himself played the chain restaurant manager who demanded more “flair” from Jennifer Aniston’s character; the reflexive response that, well actually, “the Nazis had pieces of flair that they made the Jews wear,” is probably the most kneejerk anti-establishment statement in history (and also very funny). “Beavis And Butt-Head” is essentially a show about two idiot teenagers mocking the very institution that puts them on the air, via shit-talking music videos and making long allusions to the word “fire.”

The individual is always in conflict with the institution, and in this case, the institution can be government regulation—witness “Silicon Valley”’s ongoing plot about how San Francisco housing laws make it very difficult to evict a freeloader—but is much more often the wheels of the capitalist machine, which tend to satisfy the individual self-interest of one guy all the way at the top and leaves pretty much everyone else in the dust. In “Silicon Valley,” an original idea—the beautiful algorithm for Richard’s company, Pied Piper—is constantly under assault by rapacious investors, billionaires in pursuit of an iota of authentic vision.

Yes, of course: A strict Randian interpretation would argue that Judge’s vilified corporate culture isn’t the unadulterated laissez-faire capitalism that Rand so stridently argued for as morally just. But given how rapacious (and Rand-studying) a company like Uber is, for example, that interpretation holds less water. For what it’s worth, “Silicon Valley” also pokes fun at the Howard Roark-esque individualists tortured by the brilliance of their own vision; Gavin Belson (Matt Ross) is a pitch-perfect parody of the modern-day Roark, right down to the nonsensical philosophy, narcissism, and performed heavy burden of “innovation.” In “Atlas Shrugged,” the top industrialists of the nation, fatigued by the labor of making tons of money providing infrastructure to everyone else, leave the nation entirely to seclude themselves somewhere in the mountains. “Silicon Valley” is a farce of that same plot; the “innovators” that run an important technological infrastructure seclude themselves to a specific part of the world to brood over their many woes. Rand wrings her hands at their absence from our world; Judge’s “Silicon Valley,” meanwhile, revels in how idiotic they are, when they are all condensed to just one spot.

Judge’s ethos—developed over time, borrowing from libertarianism and anarchism and the purely id sense of what makes his friends laugh—is perfect for the idiocy of the tech industry. The show observes this entire scene, from Silicon Valley’s most progressive elements to its most conservative, with an equally jaundiced eye; this is why I can write a piece lauding the way “Silicon Valley” entered the conversation about women in tech, and the Federalist can write a piece, as if this is a good thing, calling it “HBO’s Most Subversively Conservative Show.” It’s sort of both, because it’s sort of neither. It’s mostly just cynical, about other people and also ourselves.

And if “Veep”’s cynicism is a call to arms—because after all, those elected officials are paid through our tax dollars—“Silicon Valley”’s cynicism is the kind of lie-down-on-the-floor-in-despair comedy of the pawns who are at the mercy of an industry they have no voice in. It doesn’t matter how much users complain, there’s always another Facebook redesign around the corner.

In the best of Judge’s work, he’s been able to capture how the most disaffected of us really speak and feel, whether that was the office drone exploding in anger at the copier/printer, the waitress at the TGI Friday’s encouraged to produce more “flair,” or the slacker teenage boys talking shit about music videos all day. The protagonists of Judge’s work are smarter than their positions require, but still hapless. And there’s a certain kind of compassion for the neediest there, one that Rand never could produce in her blinding understanding of human selfishness. Whatever Judge’s brand of cynicism roots its politics in, on those days where you feel the semi-anarchic rage of being just another cog in the machine, it is helpful to know that someone out there really and truly gets it.

Donald Trump is a serial liar. More upsetting is that no one seems to care

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Carlo Allegri)

Donald Trump is a serial liar. Okay, to be a bit less Trumpian about it, he has trouble with the truth. If you look at Politifact, the Pulitzer Prize-winning site that examines candidates’ pronouncements for accuracy, 76 percent of Trump’s statements are rated either “mostly false,” “false,” or “pants on fire,” which is to say off-the-charts false. By comparison, Hillary Clinton’s total is 29 percent.

But if Trump doesn’t cotton much to the truth, he doesn’t seem to cotton much to his own ideas, either. He waffles, flip-flops and obfuscates, sometimes changing positions from one press appearance to the next, as Peter Alexander reported on NBC Nightly News this past Monday — a rare television news critique of Trump.

I say “rare” because most of the time, as Glenn Kessler noted in The Washington Post this week, MSM — the mainstream media — just sit back and let Trump unleash his whoppers without any pushback, even as they criticize his manners and attitude.

In an ordinary political season, perhaps Trump would be under fire for his habitual untruths, like the one that Ted Cruz’s father might have been involved with Lee Harvey Oswald. This time around, though, neither the media nor the public — least of all his supporters — seem to care. Which leads to the inescapable conclusion that these days, as far as our political discourse goes, truth, logic, reason and consistency don’t seem to count for very much.

The question is why.

One simple explanation is that Trump has changed the rules. He is not a politician but a provocateur, and he isn’t held to the same standards as Clinton or Bernie Sanders or even Cruz, all of whom actually have policies. For Trump, policies are beside the point.

… Truth, logic, reason and consistency don’t seem to count for very much. The question is why.

Another explanation is that long before Trump, social scientists observed that truth matters less to people than reinforcement, and that most of us have the ability to reformulate misstatements into truth so long as they conform to our own biases. We believe what we believe, and we are not changing even in the face of opposing facts (without this capacity for self-deception there would be no Fox News).

There is, however, another and even more terrifying explanation as to why the truth doesn’t seem to matter. It has less to do with Trump or our own proclivities to reshape reality than it has to do with infotainment — with the idea that a lot of information isn’t primarily about education or elevation, where truth matters, but entertainment, where it doesn’t. You might call it “the Winchell Effect.”

Walter Winchell, about whom I wrote a 1994 biography, was a hugely popular New York-based gossip columnist for the Hearst newspaper chain and an equally popular radio personality, although saying that is a little like saying that Michael Jordan was a basketball player. Winchell was the gossip columnist, with an estimated daily audience of 50 million. He practically invented the form, and the form was a long chain of snippets — rumor, prediction, innuendo — racing down the page, separated by ellipses.

Some of these snippets were scarcely more than a noun, a verb and an object: Mr. So-and-so is “that way” about Miss So-and-so. Does her husband know? In this way, Winchell became not only the minimalist master of gossip but also, quite possibly, the first tweeter – before Twitter.

If you are wondering how this is relevant to the 2016 campaign, in time Winchell turned his roving eye from entertainment to politics, deploying exactly the same arsenal to the latter as he had to the former. Thus did gossip leap the tracks from Hollywood and Broadway to Washington. In this, Winchell’s approach was a precursor of modern election coverage. He was obsessed with letting readers in on what was going to happen — the clairvoyance of rumor — rather than with what was happening or what it actually meant. That is, he was a horse-race handicapper long before horse-race coverage became the dominant form of political journalism.

One prominent example: At the behest of the White House, Winchell spent months floating trial balloons for Franklin D. Roosevelt and his ambitions for a third term. Basically, it was presidentially endorsed gossip.

But Winchell’s influence didn’t stop at conflating entertainment with politics — and this is where the indifference to truth comes in. Winchell reported dozens of tidbits of gossip each day. Presumably, that’s why people read him or listened to him on the radio; they wanted to be ahead of the curve. But the vast majority of these tidbits were unverifiable, and nearly half of the flashes that were verifiable turned out to be false, according to a survey conducted for a six-part New Yorker profile of Winchell by St. Clair McKelway. Since there was always a passel of new scoops every day, no one seemed to notice — or care — that he was usually wrong.

One can only assume this was because readers seemed to relish the excitement of the “news” more than they desired its accuracy. Or, to put it another way, gossip was entertainment, not information. Thus the Winchell Effect.

The Winchell Effect is alive and well in today’s politics in two respects. First, candidates can get away with saying pretty much anything they want without being held accountable so long as what they say is entertaining and so long as they keep the comments coming. Trump has been the major beneficiary of this disinclination by the MSM to examine statements. The blast of his utterances always supersedes their substance. And the MSM plays along.

To wit: Trump announced his tax plan way back in September 2015. With kudos to the Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post, which did look at his plan, it is just this week that most of the MSM are getting around to examining it — even as he changes it. (I may have missed it, but I still have yet to see a single story delving into Trump’s tax policies on the network news.)

The blast of his utterances always supersedes their substance. And the MSM plays along.

Perhaps better late than never, but the fact that he could throw out wild schemes involving trillions of dollars without the media feeling the need to vet them means that primary voters had no way to understand his tax plan and see its flaws. Of course, from the MSM’s perspective, analyzing a plan would be tackling policy, not providing entertainment. And make no mistake, the candidate and the mainstream media are in the entertainment business.

And that is the second way in which the Winchell Effect changes our politics. If candidates are not accountable, neither are the political media. Like Winchell, they are not only besotted with strategies, polls, predictions, and — in the case of a few cable networks — wild, unverifiable charges, they are, like Winchell, seldom challenged when they get it all wrong.

They were wrong about Trump not being a serious candidate. They were wrong about Jeb Bush’s and Marco Rubio’s chances to get the nomination. They were wrong about the likelihood of a contested GOP convention. Since they won’t call one another out, no one calls them out. In effect, they are implicated in the Winchell Effect as much as Trump is, which may be one reason why they don’t challenge him. Neither Trump nor the press has to be right. They just have to keep ginning up the excitement.

What this means is that our politics is no longer politics in the traditional sense of policy and governance. It is, as most of us realize, a show, a game, an ongoing reality TV saga. This is nothing new. The media have been bored with policy for a long time and have been pressing the horse-race narrative over real reporting for just as long. And when they do discuss policy, as The Huffington Post’s Jason Linkins observed, in a typically smart piece, they are likely to prefer the windy, absurd generalities of a Trump to the wonky policies of a Clinton. It makes better copy, and it has the added benefit that it doesn’t require any fact-checking.

Trump is the fullest flower of a non-political politics and the fullest product of the Winchell Effect. With their mutual lack of interest in the truth, Trump and the MSM deserve one another — a synergy of the showman and the gossip columnists. But do wedeserve them? Only if we allow our politics to become a way of amusing ourselves rather than the way to select a leader.

Meanwhile, Trump and the MSM will keep the misinformation coming, on the sadly correct assumption that many of us don’t really care about facts so long as we are being titillated.

Americans need to pay attention to the U.K.: The relationship between the next prez and future prime minister is critical

Theresa May, Boris Johnson (Credit: Reuters/Stefan Wermuth/Peter Nicholls)

Here’s a quick breakdown of the current state of U.K. politics. In the U.K. as in the U.S., until there are significant changes, only one of two parties is realistically going to be elected to govern. Unlike in the U.S., however, smaller opposition parties in the U.K. can receive so substantial an amount of the vote that it may knock one of the two ‘main parties’ out of the running. And right now, the Labour party is the one taking the biggest hit. In 2015, with the Scottish National Party, UK Independence Party and the Green party increasingly taking many left and working-class votes that might once have gone to Labour, the Conservative party returned to power with its first majority in almost two decades.

Now, it’s been said, David Cameron’s government is using its powers to try and render the Labour party “completely dead” as a viable opposition, namely by wiping millions of (largely Labour) voters off the electoral register, redrawing the voting map and attempting to cut off funding to the party. Add in the most biased and right-wing media in Europe and a new Labour leader that’s wildly unpopular nationally, and you’re looking at the likelihood of the British electorate keeping it a Conservative PM until at least 2025. This is important to understand, because it means that whoever succeeds David Cameron could help shape both Britain and US-UK relations for potentially the next decade or more.

For six years, the ties shared by David Cameron and Barack Obama have been – if you’re to believe the official line – strong. It was said earlier this year that the PM “has been as close a partner” as Obama has had during his presidency, indicating that the “special relationship,” first enjoyed by Winston Churchill and Harry Truman some seven decades ago, remains intact. By the end of 2016, however, the dynamic will have changed. There will be a new president, and depending on the outcome of the EU referendum and rising divisions within the Conservative party, there might be a new Prime Minister as well.

It’s deemed likely at this point that Hillary Clinton will be the next POTUS, but there are currently two main contenders to take over from Cameron as PM, and their success could depend entirely on whether Britain votes to Leave or Remain in the European Union on June 23. (Currently, according to the most recent poll, voters are split literally 50/50.) Heading up the Remain camp is Cameron favourite George Osborne, the Chancellor who vowed to erase the national debt but, in administering austerity measures and making sweetheart deals with corporations, has actually doubled it to £1.56 trillion and driven up poverty and homelessness in the process. Campaigning to Leave is Boris Johnson, the former mayor of London who once conspired to have a journalist beaten up and thinks nothing of calling black people “picaninnies” with “watermelon smiles.”

One of these, ladies and gentlemen, will likely be the next Prime Minister of the U.K. If it’s the Clinton-backing Osborne, an influence on and close ally of Cameron, working with Clinton, who apparently wishes to continue in the vein of Obama, the special relationship may remain largely unchanged. If it’s Johnson, however, that probably means the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, and the special relationship would be set to take a hit (potentially further exacerbated by the fact that Johnson has been highly critical of Clinton in the past, referring to her as a “sadistic nurse” representing “everything I came into politics to oppose”). John Major, the Tory PM prior to Cameron, has said that US-UK relations would “wither” if the British people vote Leave, while Obama has said the UK would no longer receive preferential treatment and would find itself at the “back of the queue” on trade.

Even if the U.K. votes ‘In’ on June 23, and it’s Prime Minister Osborne or another Cameronite who ends up leading the U.K. , the special relationship might be in trouble. There will still be necessary common ground between the U.S. and U.K. , in terms of intelligence sharing and more. But while the Obama administration, which Hillary Clinton has effectively promised to extend, has been courteous on the surface for the past six years, in reality Obama has been distancing himself from David Cameron and the Tory government for some time. The president has criticized Cameron and his team on defence spending and their handling of the Libya situation, while declaring that America’s strongest ally is, in fact, France, not Britain. Privately, the White House now “snickers” about the concept of the special relationship.

According to Washington, the special relationship as enjoyed by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, by Blair and Bush, is already in decline. A recent Congress memo suggested that organisations such as the G20 group have diminished the relationship’s “influence and centrality.” A vote for Brexit would undermine it further. Clinton also has her own reasons to remain cool on the current U.K. government: Back in 2010, Clinton was warned by an aide to be wary of the Conservatives, with special mention given to “Tory clown prince” Boris Johnson. Clinton’s emails also revealed that she retains close ties not with the Tories, but with the Blairite wing of the now struggling Labour party.

Ironically, the U.K.’s next PM might have a better relationship with the next POTUS if the Brexit–backing Donald Trump is the one in charge in 2017. Though it seems unlikely, Donald Trump having a clear path onto the ballot in November means there is now at least a chance he could be the 45th President. And though the challengers to Cameron’s throne have all slammed Trump in their own way – Osborne called him a peddler of “nonsense”; Johnson declared him “unfit” to be president – it’s difficult to imagine they would have a hard time working with him. Already the UK government is backpeddling on previous comments by declaring that Donald Trump “deserves respect,” and Trump, as a conservative, might make more of a natural ally to the Tory leadership than the more liberal Clinton would.

Johnson most obviously would make a good fit with the Donald. Where Osborne is hell-bent on forming close ties with Trump’s buzz-enemy China (something that has apparently already caused a rift between Cameron and the Obama administration), Johnson has been described as Britain’s Trump, a wealthy eccentric with signature whacky hairdo that, like Trump, thinks nothing of publicly making vulgar or racially insensitive remarks. He may have opposed Trump’s recent disparaging comments on the British Muslim community, but Boris like Trump has stoked the fire of anti-immigration sentiment himself. He also, like Trump, has shown a leniency towards Vladimir Putin that most Western leaders don’t seek to emulate, while often idolizing his own nation’s tricky past. It’s not hard to imagine these two would get along, both professionally and personally.

Which way would Trump and Johnson lead us? Ironically, these two isolationists could bring the U.S. and U.K. closer together again, with both nations left looking for similar-minded friends as they close doors with other former allies. This is all speculative of course. By some miracle the Labour party could resurrect itself and install Jeremy Corbyn as the PM in 2020. Perhaps both Osborne and Johnson will be outflanked by Theresa May, the ambitious current Home Secretary who wants to push through the most invasive surveillance laws in the western world (so says Snowden) and, in her quest to outlaw every ‘high’ – legal or otherwise – going, might have legally banned tea. May together with Hillary Clinton would be a landmark: the most significant leadership pairing in the Western world, 100% female for the first time in history. Such a pairing might be little more than symbolic, but increasingly it seems the “special relationship” doesn’t qualify as much else.

A tale of two Obamas: The unapolegetic defender of trans Americans & the man who scolds Black Lives Matter

Barack Obama (Credit: Reuters/Carlos Barria)

President Obama’s recent commencement address to the students at Howard University got a fair amount of attention for the words it contained about activism in 2016. Pundits like Frank Bruni could barely contain their glee about Obama’s rebuke to Black Lives Matter protesters.

“If you think that the only way forward is to be as uncompromising as possible, you will feel good about yourself, you will enjoy a certain moral purity, but you’re not going to get what you want,” Obama said, “So don’t try to shut folks out. Don’t try to shut them down, no matter how much you might disagree with them.”

One wonders whether that version of Obama would recognize the one whose administration is now embarking on an aggressive and uncompromising showdown with opponents of transgender rights in the United States. In only the past week, the Justice Department sued North Carolina over its new anti-trans bathroom law; Attorney General Loretta Lynch delivered what has been hailed as a historically important defense of trans people; and the Obama administration issued a decree mandating that public schools allow students to use the bathrooms that match their gender identity.

There is no attempt to understand the other side here. The White House isn’t meeting the government of North Carolina halfway. It’s asserting broad, robust federal authority in a way that is almost certain to land it before the Supreme Court.

So what’s going on? Why is the same president who chastised young black activists for their confrontational attitude deliberately picking a fight with a string of state and local governments over another civil rights issue?

The answer is pretty simple: In what feels like the blink of an eye, it has become more politically advantageous for the White House to be on the side of trans people than to sit on the fence. Actually, forget that positive framing: it’s politically dangerous for the White House not to take this sort of stand. And that’s because trans people, and queer people more generally, are reaping the rewards of decades of sustained, confrontational, fearless activism and movement-building.

It’s just over four years to the day since Obama abandoned his opposition to same-sex marriage. Think about that. Four years ago, the president of the United States wasn’t even in favor of something as conservative as gay marriage. Now, he’s waging battles for trans rights. Look at what that movement made him do! There are untold numbers of LGBT people who will have been told over the past couple of generations that they were moving too fast, that they weren’t representing themselves in the best possible light, that they were scaring straight people too much. Thank heaven for the ones who didn’t listen.

Moreover, for all of Obama’s displeasure about the tactics of the Black Lives Matter movement, just think about how influential that movement has been precisely because so many of its participants have rejected meekness. Look at how petrified they made Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders because they were willing to get in their faces and demand that their issues be addressed. Look at how quickly the discourse around criminal justice has changed—how quickly positions that were once badges of pride for politicians have turned into marks of dishonor. Has everything become better overnight? Of course not. But the entire 2016 race has been shaped by the actions of ordinary citizens taking power into their own hands and wielding it without compromise. Electoral politics has its place. Engaging with the system has its place. But so does hammering that system from the outside.

During a year in which it feels like everything is laser-focused on the presidential campaign, it’s good to be reminded of the singular electricity that comes from regular people demanding to be treated with dignity and confronting authority without apology. It is a lesson that should never be cast aside, no matter who becomes president in November and no matter how much any politician tells people to stop causing so much trouble.

Bernie or Bust will save us: The foul stench of “lesser evilism” has made our politics useless

Bernie Sanders (Credit: Reuters/Jim Urquhart)

For months now, my Facebook feed has been clogged with inspirational posts about Bernie Sanders. Bernie Sanders getting arrested at a civil rights rally. Bernie Sanders’s modest tax returns. Bernie Sanders with a bird. Now that the delegate math is stacked against him, my Facebook feed is full of panicky moralistic posts about how Bernie or Bust is going to ruin everything, that it’s time for Sanders supporters to give up on ideological purity and unify behind the presumed nominee.

But the case for giving up on Sanders is turning out to be as difficult to make as the one for nominating him. Could it be that the Bernie or Bust movement, however righteous or quixotic, is not about Sanders at all, but another symptom of a high-rolling advertising-driven culture that has eroded all our trust in the social contract? I mean, if you’re looking for someone to blame, Edward Bernays is your man, not Sanders—and certainly not anyone who plans to write in Sanders’s name on a general election ballot.

Bernays, who was Sigmund Freud’s nephew, is the one who brought advertising into everyday life, not as billboard and print ads but as real events. In other words “public relations,” a term he also coined. Bernays kicked off his “torches of freedom” campaign for the American Tobacco Company in 1929 by hiring women to pose as suffragists in the Easter Sunday Parade and light up on cue. The point was to convince more women to smoke, but the whole campaign was dressed up as a grass-roots political movement. In 1954, “the father of spin” was hired by the United Fruit Company to set up local media in Guatemala that would coordinate with the CIA to topple the democratically elected government.

But corporate accounts were only a side-job for Bernays. His career really took off when he set up shop in Washington, D.C., with the motto “If you can use propaganda for war, you can certainly use it for peace.” Working for every president from 1924 to 1961 (besides FDR), his notion that politics should be treated as a form of lifestyle advertising inspired a new generation of political consultants. It was Dick Morris, for example, who convinced Bill Clinton in 1994 to drop the platform he won on and adopt, in Morris’s words, a “consumer rules philosophy.” This formulation is misleading. As Adam Curtis argues in his award-winning BBC documentary “The Century of the Self,” this formulation is misleading. In the world of advertising, it isn’t the consumer that is king. It is the unconscious. Consultants like Morris have worked hard to convince leaders in both parties that they should ignore the better angels of our nature and speak directly to our unnamable fears and desires.

Is it any wonder that a country buried to its eyeballs in propaganda would treat the first honest politician to come along as some kind of messiah? And is it so unreasonable that Sanders’s more enthusiastic followers should balk at conventional party-unifying tactics as we transition from primary to general election? Ironically, tragically, the Bernaysian strategies of Debbie Wasserman Schultz and others in the Democratic leadership have turned out to be very bad PR for Hillary Clinton, at least for a certain constituency. To be sure, Clinton can thank these same strategies for her frontrunner status. She has emerged from the primaries with the image of a savvy power broker who knows how to get things done inside a broken system, not least by virtue of the cronyism built into the primary process. This is the “New Democrat” ideal, right? The shrewd and alert face of transactional politics. Our very own Karl Rove.

As Matt Taibbi points out, this strategy is more divisive than party leadership understands. It betrays a fundamental willingness to capitalize on—and exacerbate—the most urgent problem we face in American political culture: the crisis of a representative democracy in which representation, statistically speaking, does not exist (as found, for example, by the 2014 Princeton study.) Bernays’s project of turning politics into a sub-discipline of advertising has been so successful we no longer have a functional public sphere.

Sanders, of course, is no saint. His success raising large funds on small donations has given him plenty of advertising muscle to flex, and by all accounts he has flexed it. But here we need to make an important distinction. It is one thing to advertise your position to potential constituents in a contest of ideas. This is about engaging constituents—a function of the public sphere. It is another thing entirely when advertising *is* your platform. This is political realism: the doctrine that power can and should beget more power. Political realists do not deal in constituents, they deal in consumers. And putting one in charge of fixing America’s crisis of trust, incrementally or otherwise, is like putting the petroleum industry in charge of clean energy. Unfortunately for Democrats, this is also where Clinton utterly fails to distinguish herself from a candidate like Trump.

There is ample evidence that voters in 2016 demand a political system that appeals to their rational judgment, not one that preys on the unconscious. Perhaps party leaders, for all their posturing, really were afraid of a New Deal Democrat like Sanders. Perhaps they were so busy with the work of selling Clinton they didn’t have time to read the writing on the wall. Either way, their heavy-handed endorsement has only served to remind reformist-minded Democrats that they are part of the problem. Their only hope now is that Trump’s screaming orange face will scare us back to Clinton’s side. Who knows? Maybe they are right.

But if we really want to treat the problem—not just the symptoms—I would recommend that we stop wringing our hands on cue and take the Bernie or Bust movement for what it really is. Not the ideological purity of dreamers, or the bad sportsmanship of losers, but a struggle to do something responsible with our faith in politics now that we’ve found it again. That’s why the “vote blue no matter who” slogan, typically accompanied by a photo of Trump’s face exactly as it will appear in our post-election nightmares, is so terribly misguided. The whole thing has the look-feel of a Bernaysian PR trick.

As usual, rank-and-file Democrats want to wait until it’s too late and then crucify the messenger—that’s been our strategy ever since Ralph Nader “spoiled” the election in 2000. Isn’t it time we tried something new? Because the political life of a country is like a relationship. The more you ignore the crisis, the uglier it’s going to get. And, make no mistake, Donald Trump and his brownshirt flavored rallies are also a symptom of this crisis. That’s why the question “Wouldn’t Hillary Clinton do better for our country than Trump?” is so badly formulated—not to mention that it has the same foul smell as the prepackaged consent typically served up by both parties, no doubt on the advice of their PR teams.

Yes, it’s gotten that bad. And for many voters, this November will be a time to decide not who to vote for, but how to enact a newly awakened political will, one that aims to correct the anti-democratic tactics of both parties. Bernie or Bust is no doubt a foolhardy and extreme position, not least because it is bound to create all kinds of bad PR for the reformist cause. In the big picture, however, it looks like our best chance—perhaps our only chance—to deliver a long awaited verdict on a disastrous New Democrat agenda responsible in part for every bad decision from the Iraq Resolution to Citizens United.

More importantly, the write-in vote is our last chance to call bluff on the iron fist of political realism, which Democratic leadership have raised again and again against their own constituents by playing us off against bogeymen like Trump. A century of treating the public sphere as if it were a sub-discipline of advertising has robbed us of all but the bluntest of political instruments—without, for that matter, delivering us from the obligation of using them.

Nate Silver has a Donald Trump problem: Where does data journalism go now?

Donald Trump, Nate Silver (Credit: Reuters/L.E. Baskow/MSNBC/Photo montage by Salon)

In 2012, when I first saw FiveThirtyEight founder Nate Silver making the talk show rounds to tout his site, I was excited. He talked about bringing critical thought to data, striving for better polling analysis, and renewing our collective faith in statistics. He spoke with confidence about the power of pure data analysis as a predictive tool, and I bought every line. FiveThirtyEight has lived up to some of the early promise, but it is also beginning to see disastrous missteps that are leading some to ask whether there is even a place for data journalism going forward.

Listening to FiveThirtyEight’s Election Podcast the message you’ll hear Silver and his crew repeat the most is a warning against overconfidence in polls. Polls, he explains, are of varying quality and must be gathered together with other variables to make predictions. This data aggregation, however, has led FiveThirtyEight to commit their own deadliest sin: in abstracting real information into a predictive figure they have come up with a model in which they have much too much faith.

Wikipedia refers to FiveThirtyEight as a “polling aggregation website,” but FiveThirtyEight has become a cultural phenomenon. Its articles aren’t just graphs and charts, but intelligent political analyses with confident conclusions backed by in-depth statistics. As big data transforms the business and technical world, we are very ready for it to transform our cultural conversations . As the cultural landscape becomes more chaotic, we are desperately seeking order. The problem is, that chaos is also making the handful of historical elections we have good polling data for less predictive of the future.

Perhaps the data renaissance emerged at the wrong time. It might have established more credibility by now if it had emerged in the more predictable ’90s. But in truth, any statistician could tell you that the sample size of elections in the past 50-100 years is not large enough to reach meaningful conclusions, and FiveThirtyEight’s writers must have known that. Separate out the math, and the problem is even more obvious. Could any predictive algorithm take into account the major events that occur throughout a campaign? Could any models using data from pre-Civil War elections have maintained any predictive power in the period directly after?