Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 77

May 12, 2018

Redefining “impact” so research can help real people right away

Getty/Totojang

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Scientists are increasingly expected to produce research with impact that goes beyond the confines of academia. When funding organizations such as the National Science Foundation consider grants to researchers, they ask about “broader impacts.” They want to support science that directly contributes to the “achievement of specific, desired societal outcomes.” It’s not enough for researchers to call it a day, after they publish their results in journal articles read by a handful of colleagues and few, if any, people outside the ivory tower.

Perhaps nowhere is impact of greater importance than in my own fields of ecology and conservation science. Researchers often conduct this work with the explicit goal of contributing to the restoration and long-term survival of the species or ecosystem in question. For instance, research on an endangered plant can help to address the threats facing it.

But scientific impact is a very tricky concept. Science is a process of inquiry; it’s often impossible to know what the outcomes will be at the start. Researchers are asked to imagine potential impacts of their work. And people who live and work in the places where the research is conducted may have different ideas about what impact means.

In collaboration with several Bolivian colleagues, I studied perceptions of research and its impact in a highly biodiverse area in the Bolivian Amazon. We found that researchers – both foreign-based and Bolivian – and people living and working in the area had different hopes and expectations about what ecological research could help them accomplish.

Surveying the researchers

My colleagues and I focused on research conducted in Bolivia’s Madidi National Park and Natural Area for Integrated Management.

Due to its impressive size (approximately 19,000 square kilometers) and diversity of species – including endangered mammals such as the spectacled bear and the giant otter – Madidi attracts large numbers of ecologists and conservation scientists from around the world. The park is also notable for its cultural diversity. Four indigenous territories overlap Madidi, and there are 31 communities located within its boundaries.

Between 2012 and 2015, we carried out interviews and workshops with people living and working in the region, including park guards, indigenous community members and other researchers. We also surveyed scientists who had worked in the area during the previous 10 years. Our goal was to better understand whether they considered their research to have implications for conservation and ecological management, and how and with whom they shared the results of their work.

Eighty-three percent of researchers queried told us their work had implications for management at community, regional and national levels rather than at the international level. For example, knowing the approximate populations of local primate species can be important for communities who rely on the animals for food and ecotourism.

But the scale of relevance didn’t necessarily dictate how researchers actually disseminated the results of their work. Rather, we found that the strongest predictor of how and with whom a researcher shared their work was whether they were based at a foreign or national institution. Foreign-based researchers had extremely low levels of local, regional or even national dissemination. However, they were more likely than national researchers to publish their findings in the international literature.

Ongoing scientific colonialism?

This disparity raises concerns about whether foreign-led research in tropical nations such as Bolivia is perpetuating colonial-era legacies of scientific extractivism.

Along with its South American neighbors, Bolivia was subject to centuries of European explorations, during which collectors gathered interesting specimens of flora and fauna to ship back to the country financing the expedition. As late as the 1990s, more than 90 percent of 37,000 zoological specimens from Bolivia were in collections beyond its borders. The expatriation of biological samples has become increasingly restricted under a national political climate of “decolonization.”

But many locals in the Madidi region still expressed to us perceptions that “research is only for the researcher” and “researchers leave nothing behind.” In interviews and workshops, they lamented opportunities missed because they didn’t know about the results of research conducted on their lands. For example, when the park staff learned about previous research done on mercury levels in the Tuichi river that runs through the park, they talked about the importance of sharing this information with local communities for whom fish is a main sources of protein.

Our results suggest that foreign researchers should be wary of a modern form of scientific colonialism – conducting fieldwork in a far-off land and then taking their data and knowledge home with them.

Our study also revealed that in some cases, the question of whether or not research had been disseminated was a matter of perspective. Park offices, indigenous council headquarters and government institutions all held dusty libraries full of articles and books that were in many cases the final products of scientific studies. But very few people had actually read these reports, in part because many were written in English. Also, people in the Madidi region are more accustomed to obtaining knowledge orally rather than through written texts. So finding new ways to communicate across cultural and language barriers is key.

Collaboration beyond publication

Perhaps one way forward is to think differently about what is meant by impact and when it takes place. Although it’s typically understood to occur after the results have been written up, our research found that the most meaningful forms of impact often took place prior to that.

In ecological and conservation science research, locals are hired as guides or porters, and researchers often stay for days or weeks in communities while they are collecting data. This fieldwork period is filled with potential for knowledge exchange, where both parties can learn from one another. Indigenous communities in the Madidi region are directly dependent on local biodiversity. Not only does it provide food and other resources, but it’s vital for the continuation of their cultures. They possess unique knowledge about the place, and they have a vested interest in ensuring that the local biodiversity will continue to exist for many generations to come.

Rather than impact being addressed at the end of research, societal impacts can be part of the first stages of a study. For example, people living in the region where data is to be collected might have insight into the research questions being investigated; scientists need to build in time and plan ways to ask them. Ecological fieldwork presents many opportunities for knowledge exchange, new ideas and even friendships between different groups. Researchers can take steps to engage more directly with community life, such as by taking a few hours to teach local school kids about their research.

Of course, such activities do not make disseminating the results of research at multiple levels less important. But engaging additional stakeholders earlier in the process could make for a more interested audience when findings are available.

Whether studying hive decline with beekeepers in the United Kingdom or evaluating human-elephant conflicts in India, those affected have the right to know about the results of research. If “broader impacts” are to become more than an afterthought in the research process, non-academics need a bigger voice in the process of determining what those impacts may be.

Anne Toomey, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Science, Pace University

The real reason tech billionaires are prepping for doomsday

Getty/Salon

If you pay attention to what Silicon Valley’s best and brightest are up to, you know about tech survivalism. The digital elite are preparing for the Apocalypse, and have been for a while.

As Evan Osnos wrote in his New Yorker feature, “Doomsday Prep for the Super-Rich,”

Survivalism, the practice of preparing for a crackup of civilization, tends to evoke a certain picture: the woodsman in the tinfoil hat, the hysteric with the hoard of beans, the religious doomsayer. But in recent years survivalism has expanded to more affluent quarters, taking root in Silicon Valley and New York City, among technology executives, hedge-fund managers, and others in their economic cohort.

The Guardian noted that the end-of-days obsession could be traced back to a single source, a sort of ur-text of rich-guy panic: a 1999 book called "The Sovereign Individual: How to Survive and Thrive during the Collapse of the Welfare State." It was written by James Dale Davidson, a private investment advisor, and Lord Rees-Moog, a British newspaper editor.

You can probably already guess at what the book says. More or less, it’s a pastiche of extolling the virtues of how the rich are superior, how they're persecuted by the state, and how digital realms can and will liberate them and make them sovereign individuals. It’s a familiar trope: Ayn Rand had John Galt spewed the same list of self-serving ideas 60 years ago in “Atlas Shrugged.”

That an elite caste of people would find inspiration in these kinds of ideas is unsurprising. But there’s a more obvious reason that rich people are doomsday preppers: because that ideology mirrors their politics and their sociological views of people.

Aristocracy is the faith that a few individuals are better than the herd. Aristocracy justifies great wealth. Aristocracy says that most humans are inherently evil and will turn on each other. The mob needs strong rulers to stay sane. If authority breaks down, the rabid animals will run wild.

And the tech industry is a special subset of rich people. Our society runs on technology. Very few of us understand it, or build it personally; we rely on a select priesthood to handle that necessity. These conditions guarantee an elitist mindset. Even if Silicon Valley wasn't wealthy, they'd still be stocking up on Krugerrands and beaver pelts. The money just gives them more space to indulge Ahab-like paranoia.

Additionally, the digerati tend to view human beings as automatons: easily exchangeable and swappable data points, resources to be exploited. If I wanted to design a system to deliberately turn out an alienated, distanced elite, I'd build Silicon Valley.

To use the language of philosophy, tech-bro survivalism is overdetermined. Imagine you're an obscenely wealthy app magnate. Even if you're skeptical about Armageddon, you probably already believe you're a separate species from the rest of mankind. Letting everyone else go to hell is second nature.

The irony of being a wealthy tech-prepper should be obvious. The rich are only rich because society is skewed to favor them. They are free to enjoy their gains because the majority of us pay for roads, fire trucks and the electrical grid. Society can do without Elon Musk, but Elon Musk is dependent on society.

Tech-preppers think Doomsday will mean a war of all against all. But there's no evidence of this.

In 2009, Rebecca Solnit wrote "A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster." In it, Solnit debunks the "thin veneer of civilization" theory — the notion that authority and a strict social order are all that are keeping us from descending into barbarism.

In that book, Solnit studied the unusual solidarity demonstrated in catastrophes as varied as the 1906 San Francisco and 2008 Tang Shan earthquakes, the 2003 European heat wave, and the 1917 Halifax munitions explosion. And she found the same result, every time. When chaos arrives, the human reaction is cooperation and innovation.

"Disaster," Solnit wrote, "is when the shackles of conventional belief and role fall away and the possibilities open up.” This “unshackling” arrives in unusual ways. On 9/11, half a million people were ferried from Lower Manhattan by a spontaneous rescue armada of individual boats.

Solnit argued disaster solidarity is what led many survivors of the 1940 London Blitz to regard the bombing as a high point in their lives. Catastrophe creates communal feeling where none existed before. Given our evolution as nomadic social animals, this makes sense. Homo sapiens spent 300,000 years as equal creatures facing danger together. The current order, with a few rich and many poor, is relatively new in the history of our species.

If human societies draw together in times of peril, what are the tech-preppers concerned about?

I think we can guess. Deconstruct the fantastical fables these people tell each another. They're not concerned about ecological catastrophe, I promise you.

What are their real fears? I quote from Osnos' article:

“I kind of have this terror scenario: ‘Oh, my God, if there is a civil war or a giant earthquake that cleaves off part of California, we want to be ready.’ ”

“Everybody’s trying to get out, and they’re stuck in traffic. ... Every time I drove through that stretch of road, I would think, I need to own a motorcycle because everybody else is screwed.”

[Marvin Liao] decided that his caches of water and food were not enough. “What if someone comes and takes this?” he asked me.

“I think people who are particularly attuned to the levers by which society actually works understand that we are skating on really thin cultural ice right now.”

“When society loses a healthy founding myth, it descends into chaos,”

"I will probably be in charge, or at least not a slave, when push comes to shove.”

“The tech preppers do not necessarily think a collapse is likely. They consider it a remote event, but one with a very severe downside, so, given how much money they have, spending a fraction of their net worth to hedge against this . . . is a logical thing to do.”

The fears vary, but many worry that, as artificial intelligence takes away a growing share of jobs, there will be a backlash against Silicon Valley ... “Is the country going to turn against the wealthy? Is it going to turn against technological innovation? Is it going to turn into civil disorder?”

"Anyone who’s in this community knows people who are worried that America is heading toward something like the Russian Revolution ...”

What are the tech-preppers really worried about? Not death by fire, quake, or ice. Not the rising seas, or the zombie plague, not the return of Christ or rogue comets. Seen clearly, the calamity that the wealthy fear is democracy returning to the United States. Every tall tale they tell involves the specter of the mob.

The tech-preppers understand, at a deep level, that their ill-gotten gains are predicated on an unjust system. Deep in the brain, where reptile impulses live, tech-bros know hoarding is wrong. Human beings — even very wealthy human beings — have a bone-deep sense of injustice. We know a freeloader.

Why don't we give them the world they want? I invite the tech-preppers to fully indulge their fantasies: leave, and never return, never darken our doors again. Instead of frustrating their hobby, we should enable it. To your scattered bunkers go, await the end of days. The legends of the fall are the first hope of an eventual spring.

Could a future cure for migraines come from a chance discovery in the past?

This article originally appeared on Massive.

The first targeted treatment for migraines may soon gain FDA approval — and the molecule it targets was discovered by chance by researchers studying cancer.

The story begins back in the early 1980s, when Michael Rosenfeld, an endocrinologist at the University of California, San Diego, and his PhD student Susan Amara, were studying the production of hormones in thyroid tumors. In the course of their research, they found some of the tumors would spontaneously reduce their production of a hormone called calcitonin, which is involved in bone metabolism.

That in itself wasn’t strange: Scientists already understood that some hormone-producing tumors would stop producing one hormone, usually accompanied by starting to produce another. What mechanisms the cell used for this change in hormone production is actually what Amara and Rosenfeld were trying to figure out. But oddly, they found the low-calcitonin-producing tumors were still copying the calcitonin gene into RNA — suddenly, they just weren’t making the hormone. Even stranger, those tumors started making large quantities of a different hormone, one the researchers had never seen before.

They named the new hormone calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Weirdly, the genetic instructions for CGRP looked like they were coming from the same gene as calcitonin. Amara and Rosenfeld suspected that a then recently discovered phenomenon called RNA splicing was involved. DNA can be thought of as a “cookbook,” with genes representing different recipes. If a cell wants to make a protein, it must first copy, or transcribe, that protein’s recipe into a molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA) — like copying a recipe onto a note card. Protein-making machinery called ribosomes then translate this recipe to make the new protein.

In between the various steps in each recipe, genes often include notes and guidance about when and where to make their products. This “margin writing” is copied into the initial, primary mRNA, but is then removed in an editing process before the mature mRNA is handed off to the ribosome. This editing process is called RNA splicing, and it was discovered in 1977, around the time Amara and Rosenfeld saw their strange results.

‘Alternative splicing’

The main purpose of this mRNA editing process is to remove extra regulatory information — essentially notes in the margins of a recipe — known as introns. These need to be separated from the protein-coding parts, which are called exons. But the mRNA editing process also makes it possible to create multiple products from the same recipe by modifications — for example, removing both exons and introns, like you would omit walnuts if you didn’t like nuts in your banana bread. This is called “alternative splicing,” and it’s one of the reasons why human DNA doesn’t require more genes than plants and animals that are usually thought of as “less complex.”

Amara and Rosenfeld had discovered one of the first examples of RNA splicing at work: CGRP and calcitonin were produced by the same gene, but very different due to mRNA editing. Further research suggested that, as opposed to calcitonin, which is mainly produced in the thyroid, CGRP was mainly found in the brain, especially in a region called the hypothalamus.

Once they published their findings, other researchers in completely different fields took up the case. Neurologists Lars Edvinsson and Peter Goadsby, for example, initially found CGRP was elevated in the blood of patients experiencing migraines, showing a correlation between CGRP and the severe headaches. But the scientists still needed to show causation — thankfully, a group of selfless volunteers stepped up to the task and allowed themselves to be injected with potentially migraine-inducing hormones in the name of science. Sure enough, the volunteers who received CGRP experienced migraine-like symptoms, while those who received a placebo were unaffected.

Even though exactly how CGRP is connected to migraines is still unclear, evidence for its role has only strengthened over the last few decades. The current idea is that CGRP binds to specific receptors and sensitizes nerves in the head, face, and jaw known as the trigeminal nerves. This helps transmit pain signals, trigger inflammation, and increase blood flow. So scientists began to wonder how to use CGRP or its receptors to develop migraine medication, and pharmaceutical companies began investing in the search.

Antibodies and ‘XenoMice’

Initially, researchers looked for chemicals called small molecules, like those in many conventional drugs. While there were a few promising leads, they turned out to be toxic. An alternative strategy pursued antibodies, proteins that recognize and bind to specific sites on other molecules: They’re how your body recognizes molecules as foreign and targets them for destruction. Researchers hoped that they might be able to find an antibody that binds to CGRP receptors, effectively intercepting the migraine-inducing message.

Early attempts at using mouse antibodies in humans failed, because the antibodies themselves registered as foreign and the immune system destroyed them. To overcome this obstacle, scientists in the late 1990s engineered mice called “XenoMice,” whose antibody genes had been replaced with human antibody genes, so that antibodies the mice made would be “humanized.” In the search for a migraine antibody treatment, researchers injected these mice with human CGRP receptors. The XenoMice then produced humanized antibodies, and scientists isolated the ones that bound to the CGRP receptor. One antibody that seemed promising was erenumab.

A benefit of antibodies is that they can be incredibly selective — other important and naturally occurring molecules have receptors very similar to CGRP’s, so any potential treatment would have to not block various other receptors. Additionally, antibodies are long-lasting; while injections may not be fun, they’d only have to be administered once a month.

Pharmacutical company Novartis (working with Amgen) recently conducted a 12-week, double-blind controlled Phase III trial of Erenumab. During the trial, patients receiving Erenumab (Aimovig™) had significantly fewer migraine days than patients receiving a placebo, and many patients saw improvement in their ability to function. But despite causing an average reduction in headaches, the “response rate” was fairly low; only 30 percent saw at least a 50 percent reduction in migraine days, meaning more than half of the patients receiving the drug saw no significant benefit compared to a placebo. In the patients where the treatment did work, however, it had a big effect; many saw vast symptom improvement. Novartis just announced the encouraging results, and the treatment is slated for FDA approval next month.

It’s unclear whether it will be as a first-line treatment, available to all migraine sufferers, or reserved for more difficult-to-treat cases. And it’s too early to know whether long-term use of Erenumab could have side-effects. This is particularly an issue because, as Erenumab is a preventative medicine, it would have to be taken regularly, long-term. The main concern is the risk of blood clotting events, such as ischemic strokes and heart attacks, because CGRP also plays a role in expanding blood vessels.

Finally, of course, is the question of cost. These drugs are likely to be much more expensive that currently-available treatments, especially until (and if) generic versions become available. However, in addition to Erenumab, which targets the CGRP receptor, there are several other mAbs in clinical trials that target CGRP itself, so competition could potentially bring this price tag down.

Although further research is needed to target who is most likely to benefit and what the risks are, this is an important step in migraine treatment, and an interesting example of the way scientific breakthroughs often rely on previous research — crossing many different fields.

As for Amara and Rosenfeld? Their stories have fruitful endings as well — Rosenfeld is still a professor at UC San Diego, where he continues to study molecular signals and Amara is the Scientific Director of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), where she runs the Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Neurobiology.

My mother and the books that bind us

Getty Images

When I was little, I would pick three books to read each night with my mom before bedtime. They were typically short, but a few stick in my mind: "Bedtime for Frances," all the Frog and Toad stories, and "The Sweet Smells of Christmas," where a young bear discovers the magic of the holiday with his family. That book came with scratch-and-sniff stickers, and to this day I can conjure up the smell of those red-and-white striped candy canes just as surely as I can recall the comfort of snuggling up next to my mom while she read.

As I matured, so did my tastes in reading. It was my mother who introduced me to The Grimm Brothers’ Fairytales, those otherworldly stories of enchanting princesses, hoary beasts and that odd little man, Rumpelstiltskin, who tries to trick the miller’s daughter into giving up her baby. By third grade, I was checking out Nancy Drew mysteries from the library and gobbling them up like a big, fat pack of Twizzlers. My mom would inquire which books I’d liked best and then, like any good parent, would act interested in my opinion.

After reading Louise Fitzhugh’s "Harriet the Spy," I began toting around a notebook to record my observations of the neighborhood. My mother simply smiled, already understanding that it was a passing phase. Over the summers of fourth and fifth grade, I immersed myself in Julie Andrews’ "The Last of the Really Great Whangdoodles," Wilson Rawls’ "The Summer of the Monkeys" and the heartbreaking "Where the Red Fern Grows." Sometimes my mother would read alongside me, and we agreed that Julie Andrews was both a wonderful author and a gifted actress.

During the middle-school years, when it was difficult for my mother to do anything right in my eyes, our bond over books took a hiatus. I gorged myself on Stephen King thrillers, refusing to come to the dinner table until I’d finished the last few chapters of "The Shining." And when I attended a private high school a thousand miles away from home, we spent most of our time talking about how homesick I was or how awful dining hall food could be. Books didn’t come up very often.

But then, like the ebb and flow of all good relationships, my mom and I found our way back to each other, once again through books. In college, I was taking women’s studies courses, and during our weekend talks we would chat about Gloria Steinem’s "Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions" or Betty Friedan’s "The Feminine Mystique."

“Did you ever feel this way, Mom?” I’d ask. “Do you now?” Had I missed a huge piece of her emotional life? She shared her stories about being on the UW-Madison campus before the height of the Vietnam War protests, about how difficult it was to work and raise two children at the same time. Such conversations were a springboard to discuss more books, like Toni Morrison’s "The Bluest Eye" or Gloria Naylor’s "The Women of Brewster Place." Suddenly, reading was more than great storytelling — it was a window onto people’s lives.

But it was really in my late 20s, my 30s and early 40s that our bond over books grew the strongest. My mom had more time on her hands to read, and my tastes had evolved enough that we often discovered we were reading the same book at the same time, unbeknownst to us until we picked up the phone for our Sunday night call. My mom and I both loved Elinor Lipman’s "Isabel’s Bed," with its hilarious, spirited main character. We marveled over Barbara Kingsolver’s storytelling powers in "Animal Dreams" and later confessed that we’d both fallen in love with an old Western, Larry McMurtry’s rollicking, big-hearted "Lonesome Dove." We laughed over Augustus McCrae and Woodrow McCall as if they were our long-lost relatives.

My mother also admired books tied to the land, with a strong sense of place. So, it was Kathleen Norris’s "Dakota" that gave her some solace when she and my dad drove the winding route from Wisconsin to Boston, worrying whether my newborn son, who was delivered not breathing, would survive. It was a book that I would turn to again and again during difficult times. She introduced me to Michael Perry’s "Population: 485," another book steeped in place and a strong sense of community. She loved anything by Jane Hamilton and Charles Baxter, as did I.

Of course, there were also places where our tastes diverged. Later in life, my mom took a liking to Alexander McCall Smith’s "The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency" series while I was reading a bushel of self-help books, thick in the weeds of parenting. (During one phone call my mother advised, “All you need is 'Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care.' I still have the copy I used with you. I’m sending it to you now.”)

When I finally wrote my first novel, "Three Good Things," I worried while my mother pored through the page proofs. Would she like it? How many errors would she find? I knew all too well what a tough critic she could be. Thankfully, the novel held up under her scrutiny, with just a handful of suggested changes. I had misused the word “startled” (a pet peeve of hers), and she had tweaked some details about a festival on the Square in Madison, ensuring all was authentic to her Midwestern eye. She admitted that when she read the acknowledgments page, the mention of my dad, who’d recently passed away, brought tears to her eyes.

My mother never got to read my second or third novels, and sometimes I felt adrift in the writing process without her wise input, her coaching eye. That we can’t go out together to toast "The Summer Sail," just released last week, makes me sad. But I’d like to think that she would have enjoyed the book. It is, at its heart, a story about the strong bond of women’s friendships and family ties.

My mom has been gone for over three years now, and it’s funny how there are still days when I go to call her about a new book I’ve read and have to stop myself. Wherever she might be, I hope she is surrounded by a library filled with wonderful novels.

Wonderful novels and, of course, good friends.

The moms behind these huge careers

Katie Couric, Ralph Macchio and others on what their moms taught them

Salmonella outbreak on East Coast worsens

Getty

Not all is eggcellent in America's food production this week.

Federal health officials announced news on Friday about a salmonella outbreak which has led to a recall of nearly 207 million eggs. Thirty-five cases have been recorded across nine states, and there have been 11 hospitalizations. Nobody has died from the outbreak, however the number of those affected has increased by a dozen since it was first recorded.

“CDC continues to recommend consumers, restaurants, and retailers should not eat, serve, or sell recalled eggs produced by Rose Acre Farms’ Hyde County farm,” the Friday announcement stated. “Throw them away or return them to the place of purchase for a refund.”

In the initial announcement, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated they traced the outbreak to shell eggs from Rose Acre Farms which is located in North Carolina.

“FDA traced the source of some of the shell eggs supplied to these restaurant locations to Rose Acre Farms’ Hyde County, North Carolina farm,” the initial announcement stated. “FDA investigators inspected the farm and collected samples for testing. Laboratory testing identified the outbreak strain of Salmonella Braenderup in environmental samples taken at the farm.”

An Indiana branch of Rose Acre Farms voluntarily recalled over 200 million eggs, stating that their shell eggs may have been contaminated with Salmonella bacteria as well. The recalled eggs were reportedly sold in Colorado, Florida, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia under various brand names, such as Coburn Farms, Country Daybreak, Crystal Farms, Food Lion, Glenview, Great Value, Nelms, Sunshine Farms, and Publix.

According to a Food and Drug Administration report, inspections of the farm in North Carolina found that the farm might have had a rodent problem. According to the report, inspectors recorded "condensation dripping from the ceiling, pipes, and down walls, onto production equipment." Equipment was reportedly "visibly dirty with accumulated grime and food debris."

Insects flying around the food were observed, too.

“Throughout the inspection we observed at least 25 flying insects throughout the egg processing facility,” the report stated. “The insects were observed landing on food, food contact surfaces, and food production equipment.”

“There were insanitary conditions and poor employee practices observed in the egg processing facility that create an environment that allows for the harborage, proliferation and spread of filth and pathogens throughout the facility that could cause the contamination of egg processing equipment and eggs,” the report added.

According to the CDC, Salmonella causes approximately 1.2 million illnesses and 450 deaths every year. The summer months are usually the most common time for the illness to occur.

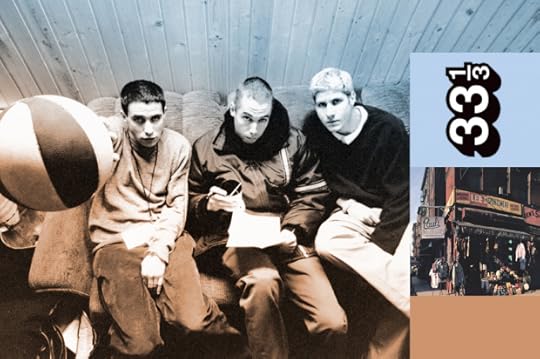

What happens when you rent out your house to the Beastie Boys?

Capitol Records/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon

Excerpted from “The Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique” by Dan LeRoy (Continuum, 2006). Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing.

The G-Spot has entered Beastie Boys lore as the house that allowed them to indulge their deepest, darkest blaxploitation fantasies. It is imagined as a mansion-slash-museum of perfectly preserved seventies chic, which the band and its associates would thoughtlessly trash in orgy after "Licensed to Ill"-inspired orgy.

In fact, an argument can be made that the one-bedroom house on Torreyson Drive, owned by Alex and Marilyn Grasshoff, actually provided the Beastie Boys some much-needed stability at a time when "Paul's Boutique" was threatening to get lost in a morass of recreational drug use and hotel bills. If nothing else, the $11,000 rent the band paid each month still beat the cost of three $200-a-night hotel rooms. "It never had occurred to us that you don't have to live in a hotel," admits Diamond with a laugh. "But I think we had all become more serious about thinking, 'OK, we've gotta finish this record.'"

The property offered a view of all the major movie studios and the Griffith Observatory, while the band's neighbors would have included actress Sharon Stone; the old Errol Flynn estate (later owned by singer Justin Timberlake), was close by on Mullholland Drive. A less glitzy, but still important, benefit was the large gold "G" on the front of the house, making the location's new nickname both perfect and inevitable.

When they attempted to rent from the Grasshoffs, the Beasties' reputation—for once—did not fully precede them. As Marilyn Grasshoff remembers it, "The agent didn't tell us anything about the Beastie Boys. He said they were three young men who were writers."

The Grasshoffs would soon learn the rest of the story. "When I said, The Beastie Boys are living in my home,' people said, 'Oh my gosh, you let them in your home?!' Because they had made this movie where they trashed this house," says Mrs. Grasshoff. Once again, "Fight for Your Right (To Party)"—via its video—had come back to haunt the band. "And of course, I don't watch those kinds of movies, so it made me a little nervous. Maybe we made a mistake."

It was not as if the Grasshoffs were unworldly rubes. Alex Grasshoff was a producer and director who had helmed episodes of "The Rockford Files," and "ChiPs," as well as several films, including the Emmy-winning 1973 documentary "Journey to the Outer Limits." His wife, better known under her stage name Madelyn Clark, owned a Los Angeles studio, which A-list musicians would often rent for tour rehearsals.

The couple, who traveled frequently, also had experience turning their home over to showbiz personalities. Actor Bill Murray had lived at the Grasshoffs' in 1980 while playing gonzo writer Hunter S. Thompson in the film "Where the Buffalo Roam." (Thompson himself stayed in the guesthouse.) And even rocker Jon Bon Jovi had once been a tenant, pleasantly surprising Mrs. Grasshoff with his tidiness and good manners. "He was very good to the house," she recalls.

Speculation to the contrary, she would say the same of the Beasties. "What happened was, they were absolutely clean and neat," she says, "and took care of the place very, very well." However, the Beasties would be the last tenants to rent the Grasshoffs' home. The band had wanted to extend the lease, Marilyn Grasshoff recalls, "but my husband said, 'No, I want to come back home.'" The trio would still recall the Grasshoffs fondly in the 1998 song "The Grasshopper Unit (Keep Movin')," comparing the couple to Thurston and "Lovey" Howell from "Gilligan's Island."

Of course, the Grasshoffs were also not aware of the activities taking place in their absence. The foremost attraction happened to be Mrs. Grasshoff's closet, which yielded, as Ricky Powell remembers, "Crazy, crazy seventies shit. Fur coats. Crazy pimp hats. Platforms. Lots and lots of velvet." Mike Simpson, who also got a good look at the collection, observes, "I don't think she ever threw anything away." It was this gold mine of a wardrobe that would give the Beasties—in particular, Mike D—much of their retro look for the "Paul's Boutique" era.

The trio managed to get a Ping-Pong table into the house—chipping Mr. Grasshoff's Emmy Award in the process. They also made frequent use of the home theater system, rare for its time, and what Mike Simpson remembers as Mr. Grasshoff's "huge collection of prison movies." [producers Mike] Simpson and John King, who had access to the house even when the Beasties were away, spent as much time there as possible.

"Despite the fact that John and I had success from the Tone-Loc and Young MC records, we still hadn't seen a dime. We were sharing a $600-a-month apartment, and we had to step over bums to get into our building, and we were digging in our couches for loose change to buy a burrito at 7-Eleven," Simpson recalls, laughing. "So the G-Spot offered a lot of luxuries that we weren't accustomed to." Yet the only truly crazy thing King noticed there "was a bunch of late teen/early twenties kids hanging out in such a mackadocious—yet dated—pad, partying."

"They didn't trash the place the way they trashed a lot of other places," admits regular guest Sean Carasov, who had seen more than a few accommodations wrecked by the Beasties. "But they worked it." Perhaps the worst bit of damage the band inflicted on the G-Spot, however, wound up having a unexpectedly beneficial effect. A wooden gate, smashed into by Mike D's car, would be repaired by Caldato's friend Mark Ramos-Nishita—later a valuable musical collaborator as the keyboardist Money Mark.

Although Diamond commandeered the home's master suite, while Yauch set up shop in the video room, it would be Horovitz's underground bedroom in the guesthouse, with its window into the swimming pool, that became the G-Spot's best-known feature. Ricky Powell would shoot the inner sleeve photo of Paul's Boutique through this porthole, capturing the Beasties clowning underwater.

Salon Talks: DMC

Darryl "D.M.C." McDaniels, founding member of RUN-D.M.C., breaks down why he thinks hip-hop has a generational divide

Shock and thaw: Alaskan sea ice just took a steep, unprecedented dive

AP Photo/Mark Thiessen

April should be prime walrus hunting season for the native villages that dot Alaska’s remote western coast. In years past the winter sea ice where the animals rest would still be abundant, providing prime targets for subsistence hunters. But this year sea-ice coverage as of late April was more like what would be expected for mid-June, well into the melt season. These conditions are the continuation of a winter-long scarcity of sea ice in the Bering Sea—a decline so stark it has stunned researchers who have spent years watching Arctic sea ice dwindle due to climate change.

Winter sea ice cover in the Bering Sea did not just hit a record low in 2018; it was half that of the previous lowest winter on record (2001), says John Walsh, chief scientist of the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “There’s never ever been anything remotely like this for sea ice” in the Bering Sea going back more than 160 years, says Rick Thoman, an Alaska-based climatologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The record low February sea-ice extent in the Bering Sea, off the coast of Alaska, compared with the 168-year historic record. Credit: Zachary Labe, University of California-Irvine and Heather McFarland, University of Alaska

A confluence of conditions — including warm air and ocean temperatures, along with persistent storms — set the stage for this dramatic downturn in a region that to date has not been one of the main contributors to the overall reduction of Arctic sea ice. Whereas a degree of random weather variability teed up this remarkable winter, the background warming of the Arctic is what provides the “extra kick” to reach such unheard-of extremes, Walsh says.

Sea ice expands outward from the central Arctic Ocean each autumn as the sun dips low in the sky and temperatures drop. In the Chukchi and Bering seas off Alaska, freeze-up used to begin in October. Ice would edge southward and build up throughout the winter until peaking in March when the sun climbs high again, and the ice would then start melting back. But autumn freeze-up in the region has begun steadily later as Arctic temperatures have risen at twice the global rate, fueling a self-perpetuating cycle of ice loss: As it melts it leaves more open water to absorb the sun’s rays in summer, and this further warms the ocean causing more ice to melt, thereby delaying the autumn freeze. In recent years that freeze had moved into November but this year temperatures were so warm the Chukchi Sea still had open ocean in December. “And that,” Walsh says, “hasn’t happened before” in recorded history.

The unusual warmth continued throughout this winter, in part because of an atmospheric pattern that kept warm air and storms periodically sweeping up from the south. One such event in February helped push the monthly temperature over the Bering and Chukchi seas some 18 to 21.5 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 12 degrees Celsius) above normal. Consequently, the Bering Sea lost half its ice extent at a time when ice should still have been growing. The storms also pushed back against the normal southward flow of ice from the Chukchi Sea into the Bering. Accompanying winds stirred up waves that kept new ice from forming, and broke up what thin ice there was.

Such atmospheric conditions have long been a limiting factor to sea-ice growth in the Bering Sea, Thoman says. But until recently the water there was reliably cold enough in autumn that when winds did blow from the north, sea ice would still spread. The last few years have seen unusually warm ocean waters in the Bering. Research meteorologist Nick Bond and others think this is “a lingering hangover” of a larger marine heat wave — dubbed “The Blob” — that lay off the west coast of the U.S. and Canadian mainland from 2014 to 2016. Bond, who works for NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, thinks some of those warm waters followed ocean currents up into the Bering and left a deep reservoir of warmth that impeded ice formation, although he has not yet formally studied this.

The occurrence of these unusual conditions off Alaska this past winter can largely be chalked up to the random weather variations in a chaotic climate system, Bond, Walsh and Thoman all say—but they add that global warming likely amped up the severity of the situation. A study Walsh co-authored in the January Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society found that although The Blob was ushered in by natural variations, without climate change it likely would not have been as intense as it was. And whereas the Bering Sea has had plenty of winters as stormy as this one, the underlying warming trend means such winters can have a much bigger impact on sea-ice formation in today’s climate.

The lack of sea ice is not just hitting walrus hunting hard; throughout the winter and spring, coastal communities have seen substantial flooding and erosion during storms without much of the usual sea ice to act as a buffer. What little there is has been very thin stuff local residents call “junk ice,” Thoman says: “It wasn’t very much better than no ice at all.”

At the end of April the Bering Sea was nearly ice-free — four weeks ahead of schedule. With the sun shining on the Arctic again, the open ocean is soaking up heat that could set up another delayed freeze-up again next fall. Because of the role the weather plays, though, “every year is not going to be like this,” Thoman says. “Next year will almost certainly not be this low.” But as temperatures continue to rise, he says, “odds are very strong that we will not go another 160 years before we see something like this” happen again.

Paris museum welcomed nudists for a day

The Parisians know how to curate a unique art experience—even in the year 2018. CNN reports that earlier this month, Palais de Tokyo in Paris, invited guests for a clothing-free event. Indeed, visitors were allowed to peruse the gallery naked for the day.

According to the report, guests arrived clothed, but had the option to check their clothing at the cloakroom. In order to keep from startling other visitors, the naked affair took place before the museum opened to the public. Staff, fully clothed, were reportedly available to answer any questions that the naked visitors had.

The event is significant because it was the first time a Paris museum welcomed nudists. It is unclear if other famous museums like The Louvre Palace will follow, but last summer in Paris city officials reserved a space for naturists to enjoy themselves in an open grassy space in the Bois de Vincennes park. It was open daily from August 31 to October 15, 2017.

Like anything involving nudity and art, the symbolism behind the event was much more than simply wanting to go to a museum naked.

“Putting on clothing, or an armor, it’s a statement,” Vincent Simonet, a 42-year-old singing teacher who attended the event, told the New York Times. “Today, nudism is seen as a statement, but really it’s the opposite, it should be seen as a pure state.”

As for the New York Times’ reporter, Thomas Rogers suggested, being nude was a little bit of a distraction from the art.

“As for me, I was inclined to revisit the exhibition, especially its more political works, in a clothed context, when I wouldn’t have to worry about feeling insensitive,” he wrote.

The most uncomfortable part of the experience for him was feeling cold though, not exposed.

“A half-hour into the first nudist tour of the Palais de Tokyo, a contemporary art museum in Paris, I had gotten used to the feeling of exposure, but I hadn’t acclimatized to the cold air circulating through the cavernous galleries,”Rogers wrote.

In the U.S., checking your clothes at the door in the name of art has become a form of protest. In June 2017, over one hundred people went to Times Square, took off all their clothes, and painted a unique message across each of their chests to promote various messages of body acceptance.

“I think that human expression is something that is so important and it’s lacking in society today. It helps us to be together and to feel connected as a community, but there aren’t a whole lot of opportunities to do it,” said Matthew "Levee" Chavez, the creator of Subway Therapy, which gained national popularity after the election and inspired the naked event in Times Square.

Nudism does appear to be making a comeback around the world. The American Association for Nude Recreation is hosting a Nude Recreation Week from July 9 - 14 this summer, and the first ever International Skinny Dip Day on July 14.

“Patrick Melrose”: Benedict Cumberbatch’s darkness fix

Showtime/Ollie Upton

As varied and sprawling as an actor’s filmography may be, we have a tendency to link them to specific parts or types of parts. This means that regardless of how many very disparate roles Benedict Cumberbatch has played over the years, most people will see him as the modernized Sherlock Holmes or, lately Doctor Stephen Strange, aka that wizard from “Avengers: Infinity War.”

While Cumberbatch doesn’t give off the impression that he minds associations with high-concept properties, the projects he takes between them speak volumes about how he wants to be viewed in the long term — as a dramatic virtuoso, not merely a star.

In Showtime’s “Patrick Melrose,” a five-part miniseries airing Saturdays at 9 p.m., he gets right to making his case for the former designation even as he displays an awareness of celebrity’s value. This is evidenced in his chosen entry into Edward St. Aubyn’s stories: “Bad News,” the second of St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels and the series’ first installment.

Saturday’s opening hour shows the twenty-something son of an aristocrat holing up in Manhattan’s Drake Hotel in 1982, pummeling himself with all variety of drugs and booze: Quaaludes, Black Beauties, heroin, cocaine, whiskey, anything he can shoot up or swallow, using one intoxicant to mitigate the effects of another.

And “Bad News” is a taxing proposition for Cumberbatch, since on top of bludgeoning his mind and body into oblivion Patrick must attempt, to the best of his ability, to appear respectable at times. His monstrous father, David (Hugo Weaving), has died, bringing an assortment of family friends out of the woodwork, most of them terrible excuses for human beings themselves.

Far worse are the loud, angry, cruel voices bouncing around inside his skull, all of which Cumberbatch acts out or reacts to, much to the disturbance, fright and confusion of the people around him. When he can hold himself together he mutes them with a mordant, unforgiving wit. When he can’t — when the pharmaceuticals kick in, he slurs and shivers, he screams and sweats. In the midst of an awkward conversation with a family friend he excuses himself to smear his incapacitated body down a hallway in a pathetic attempt to escape.

Much of the episode amounts to a solo piece for Cumberbatch, obscenely comical at times, pathetic and heartbreaking, awards-season bait of the highest degree. This is a compliment. Not pandering, just fact: Cumberbatch truly is that extraordinary in these episodes.

The actor calls Patrick one of two roles on his “acting bucket list.” The other is Hamlet, which he checked off in 2015 when he played the Prince of Denmark at the Barbican in London. “Patrick Melrose” calls upon different muscles than the Bard’s famous tragic figure, as Patrick is an entirely different creature of sorrow.

“Patrick Melrose,” which Cumberbatch executive-produces in addition to top-lining the cast, could have been an entirely forgettable enterprise, another entry in the poor rich kid entertainment pantheon that plays to decreasing amounts of sympathy as time goes by.

Instead, it succeeds because of St. Aubyn’s lacerating, unmerciful and highly descriptive prose, all of which Benedict takes into his flesh, and because St. Aubyn has very little to offer in the way of sympathy or credit to the upper class from whence he comes. Like Patrick, St. Aubyn’s father came from English nobility but has only a title and a perverse relationship with masculinity and worth to show for it.

He knows this world well enough to lacerate its weak spots, where the rot has compromised the structure; the apex example is Princess Margaret (Harriet Walter) depicted as an unpleasant, unhappy crone hating life even as champagne and fireworks sparkle all around her. Walter’s role is a minor one, but it says it all.

Through Patrick, it’s plain to see St. Aubyn resents what’s been done to him even as he celebrates the resilience it’s created within. As far as that goes — that is, as a tale of lasting damage — “Patrick Melrose” bears a touch of resemblance to other tragedies. Insofar as it offers the opportunity to unblinkingly observe a man’s life from childhood through his 40s, from the onset of repeated traumas that, as a friend aptly puts it “split the world in half,” through his debased junky phase and onward through sobriety, recovery and setbacks, it’s a marvel.

To be honest, it’s also not the easiest viewing experience, especially if you lack awareness of the depths to which Cumberbatch and St. Aubyn push Patrick. Watching Cumberbatch race through so many character shades proves dizzying in that first hour. But in return, subsequent episodes allow the viewer to appreciate his periods of steadiness and calm, some of it obviously painful to Patrick even though he knows the alternative, though intoxicating to remember, would end in death.

Weaving dominates the second episode, “Never Mind,” which rewinds to 1967, when 9-year-old Patrick (played by Sebastian Maltz) is summering with his family in France. It is there where he suffers the full force of his father’s brutality, mostly implied instead of shown. Weaving’s ability to weaponize fear through the faintest smile comes through again and again, along with Jennifer Jason Leigh’s realization of the sublimated torment Patrick’s mother Eleanor endures.

David is enabled by a gallery of ghastly souls, few as caustic as the social chameleon Nicholas Pratt (Pip Torrens) or as discontented as Bridget Watson-Scott (Holliday Grainger at her minxy finest when we first meet her). But even a few of these accessories receive a measure of benediction in David Nicholls’ screenplay, particularly Indira Varma’s Anne Moore, an American ridiculed for displaying a mote of care for him.

Nicholls makes optimal use of St. Aubyn’s silvery language throughout the script. But Edward Berger’s direction and James Friend’s cinematography ensure the visual experience speaks as loudly and purposefully as the people in Patrick’s world.

When his life is submerged in intoxication, real or allegorical (wealth and status are dangerous drugs in themselves here), the colors are brighter and the world is a glory. Even dim hallways glow with the loveliest blue. Sobriety, meanwhile, appears fuzzier and drained of color, telegraphing the sentiment that ugliness is part of the price of living in a state of clarity and truth.

Nestled within all of its grimness lurk touches of grace, some more obvious than others. “Everything’s a miracle, man,” a man observes to Patrick at one point -- a man who, like him, should have been dead many times over. But that brief moment claims the full weight of hope, even if it’s in passing. The story earns it as surely as Cumberbatch warrants all the accolades coming his way.

What remains to be seen, beyond the question of whether he scores an Emmy nomination, is whether the actor will actually appear for the ceremony if he does. He hasn’t always attended in the past. Considering how extensively his range showed up in “Patrick Melrose,” maybe this time he actually will show up. That is, if he doesn’t deem such a self-congratulatory society demonstration to be too garish.

Moms were behind these huge careers

May 11, 2018

This kind of civil rights lawsuit may be endangered under Trump

AP/Manuel Balce Ceneta/J. Scott Applewhite/Salon

This article originally appeared on Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting

In announcing a $2.85 million settlement in an age discrimination lawsuit today, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s acting chairwoman congratulated her civil rights agency.

In announcing a $2.85 million settlement in an age discrimination lawsuit today, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s acting chairwoman congratulated her civil rights agency.

“I am very proud of the relief the EEOC has obtained here . . . to ensure that applicants and workers do not face this sort of discrimination in the future,” Victoria Lipnic, a longtime commissioner appointed as acting chairwoman by President Donald Trump last year, said in a statement.

But Lipnic actually voted against bringing the lawsuit in the first place.

It’s an example of the kind of ambitious civil rights lawsuit that may not happen once Trump’s other nominees are confirmed and the five-member commission swings from a Democratic majority to a Republican one.

Back in 2015, the commission’s general counsel wanted the go-ahead to sue Seasons 52, part of the Darden family of restaurants, for systematically discriminating against job applicants over the age of 40 at restaurants nationwide.

Lipnic and the other Republican commissioner voted against filing suit, while three Democrats voted for it, clearing the path that led to the nearly $3 million settlement.

In the end, more than 135 job applicants gave testimony that Seasons 52 managers asked them their age and made comments such as, “Seasons 52 girls are younger and fresh,” according to the commission. The settlement also requires the company to change its hiring processes and pay for a compliance monitor to make sure it doesn’t discriminate anymore.

A Seasons 52 spokesman said in an email: “We are pleased to resolve this EEOC matter. Putting this behind us is good for Seasons 52, good for our team members and good for our shareholders.” Its parent company, Darden, also owns the Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse chains.

After Lipnic was appointed acting chairwoman in early 2017, a Reveal review of commission votes found that she voted against pursuing 20 lawsuits in her previous seven years as a commissioner. The other Republican commissioner serving with her voted against more than twice as many cases.

If a majority of the commission votes against bringing a lawsuit, the agency’s findings of discrimination may never become public. The commission discloses its investigations only if there is a lawsuit or if an employer agrees to it as part of a prelitigation settlement, which is rare.

Republicans and business groups have criticized the commission for pursuing large-scale, systemic cases, favoring a focus on reducing the commission’s backlog of individual complaints.

A Republican majority on the commission may lead it in that direction, but two Trump nominees still are awaiting Senate confirmation. One of them, retired Army Lt. Col. Daniel Gade, once called the idea of women in ground combat “laughable,” though he said his views have changed.

Trump also nominated a new general counsel, Sharon Fast Gustafson, who has signaled that she may be less aggressive in filing lawsuits and pursuing national systemic cases. If she is confirmed and steers away from cases such as the one against Seasons 52, they might not even come to the commission for a vote.

Will Evans can be reached at wevans@revealnews.org . Follow him on Twitter: @willCIR .

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.