Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 716

July 17, 2016

Enough of the “Us vs. Them” binary: Why I’m writing in Bernie Sanders on election day

Bernie Sanders (Credit: Reuters/Jim Urquhart)

On Nov. 8, 2016, approximately 54 percent of all eligible U.S. voters will flex their Constitutional right to vote in the general election. In case you aren’t aware of how Americans prioritize their politics, here’s a glimpse: 74 percent of this same demographic tuned in to watch the Super Bowl last year.

Most of us were taught from kindergarten on that our government is a Democracy and that America is the freest country on Earth. Perhaps the reason so few of us vote is that the benefits of all this democratic freedom don’t always measure up to all the hype. For example, instead of having one presidential candidate to choose from – like in a dictatorship – we get two.

It’s a recipe for division if there ever was one. Pit Team A against Team B with the task of solving problems that effect all sides and just watch how little progress can be made. The greater good loses every time.

“Groupthink” – a hallmark of political parties – suppresses independent thought, creativity and dissent and encourages bias and irrational decision making in the “in-group” while any “out-group” is discounted as inferior and scorned. These aspects are intensified when only two groups are powerful enough to achieve a desired goal – in this case, winning an election – and people are forced to choose between them. The human mind shifts to binary mode when presented with only two choices, an evolutionary leftover from times when a snap judgment of “Us vs. Them” could determine our survival. The tendency nowadays is to identify with one and repudiate the other. Normally, it’s not until a third or fourth option is presented that critical thinking is engaged.

If anything ought to be grounds for critical thinking it’s the selection of our government officials who vote on our laws and decide on whether our sons and daughters are sent off to war overseas. Instead, most of us vote to promote our party’s victory or to thwart the other party’s.

The two main strategies for instilling and sustaining an “Us vs. Them” mentality within the larger culture are: A) propagating “fear” of the “other” and B) appealing to the basic human urge of “belonging” to a like-minded group.

An email I received from “Hillary” recently employs both tactics.

“Donald Trump is not a normal candidate, and if he beats us, it will be more than a defeat at the ballot box — it will be a once-in-a-generation setback for our values and our shared idea of what America means.”

Here, Trump is the big bad wolf standing at the doorway of democracy threatening to blow the whole house down and destroy our way of life. We’re admonished to fear him and everything he represents. But, thankfully, all is not lost.

“Chip in before tonight’s midnight deadline, get a free sticker, and let’s show Trump exactly who he’s up against — the strongest team in this election.”

By coughing up some dough we can help Hillary stop the big bad wolf from ruining America and can congratulate ourselves on belonging to the strongest team. Never mind that the $360 million her campaign has already raised isn’t enough, purportedly, to ensure Hillary’s victory.

The “Us vs. Them” mentality and the constant money grubbing that result from bipartisanism are two of the biggest reasons I’m politically unaffiliated. Other reasons have to do with an early love affair I had with the writings of Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and John Adams, who each disapproved of political parties in general, especially a system built around two major parties.

In his Farewell Address, Washington referred to “The alternate domination of one faction over another …” as a “frightful despotism.” While Adams had this to say: “There is nothing which I dread so much as a division of the republic into two great parties … This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.”

More than “dislike” political parties, Jefferson held them in contempt: “If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.”

As an independent voter, I’ve naturally grown accustomed to compromise when deciding whom to vote for. In the past, when there hasn’t been a candidate who’s inspired my support, I’ve voted for whoever seems the less likely to cause much damage, the candidate who seems most trustworthy and honest.

Since both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are dishonest and untrustworthy, I can’t, in good conscience, vote for either of them.

Instead, this election I plan to do something I haven’t done before. I plan to write-in my candidate of choice: Bernie Sanders. And I’m not alone. Millions of others fed up with divisive Establishment politics plan to do the same – if not write in Bernie Sanders, then vote for a third-party candidate.

When Senator Bernie Sanders announced his presidential bid I’ll admit that, as much as I liked him, I thought he wouldn’t stand a chance. The rolling media blackout that darkened the start of his campaign coupled with a majority of superdelegates pledging their support to Clinton eight months before the first ballot was cast made him a long-shot at best.

Nevertheless, in a short amount of time millions of Americans were feeling the Bern, creating a schism in the Democratic Party. Since then, Hillary has called for “party unity” and, to try to draw Sanders’ voters her way, has attempted to come across as much more progressive than she actually is. This isn’t just disingenuous. It’s transparently manipulative and has only succeeded in pushing true Progressives farther from her reach.

Somehow it seems to be lost on her and many other Democratic leaders that Sanders’ political revolution is founded in principles that oppose nearly everything Hillary’s neoliberal brand of democracy consists of – corporatized government, crony capitalism, limitless campaign contributions, increasingly deregulated global trade and control by the wealthiest few.

The Republican Party faces a similar rift among party members. If the absurdity of the 2016 election has revealed anything it’s that voters want more than change – they want something completely different – and will vote for almost anyone who isn’t a figurehead of the Establishment.

Regardless of who’s been president over the past 30 years, median household incomes have either stagnated or steadily declined. The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer as the middle class is diminishing altogether and neither Democratic or Republican incumbents seem to do a damn thing but make it worse. Should Hillary get elected, 4 of 5 presidents in the last 30 years will have been a Clinton or a Bush.

It’s no wonder that Hillary and Trump have respectively earned the highest “unfavorable” ratings of any Democratic or Republican presidential candidate in history, which might have something to do with a couple other things they have in common: a history of outright lying to the public and hundreds of millions of dollars amassed through surreptitious means.

While both parties push for unity, members who aren’t “with her” or with him are being urged to vote against the other party by voting for their party’s nominee. This twisted logic implies that at least you’ll be doing your part as a member to help your party win.

Voting for someone you dislike to block someone you despise is commonly known as choosing between “the lesser of two evils.” This phrase has seen prolific usage as of late. It’s apropos if a little misleading since I don’t think most Americans perceive either candidate as literally evil. But, for the sake of argument, let’s suppose for a minute they are.

Evil’s most prevalent, recognizable trait is a lack of empathy for others’ pain and suffering. If I had to decide if Hillary or Trump were the lesser of two evils based solely on how empathetic each comes across, I’d probably end up voting for Trump.

Many Democrats are genuinely fearful of what a Trump incumbency might mean for the future of America. But I just can’t bring myself to fear him. For one, his more ridiculous and dangerous ideas would be held in check by Congress – he is, after all, only one man. And though he’s made a sweeping array of insensitive comments mainly about certain ethnic groups and women, they were so stereotypical as to sound like drunken rants from a Southern Uncle at a down-home barbeque. Ignorant and inflammatory? Yes. Lacking in empathy? I’m not so sure.

Hillary gave an interview to Diane Sawyer in 2011 in which she joked, then gleefully guffawed about her role in the assassination of Libyan ex-Prime Minister Muammar Gaddafi. Some people take pleasure in an enemy’s death, I suppose. But the mission also entailed the deaths of dozens of innocent women and children, which Hillary surely knew about.

More recently, she was criticized for donning a $12,000 jacket while giving a speech on income inequality. A staggering 46.7 million people in the U.S. live beneath the poverty line, a family of four earning roughly $24,000 a year – twice the amount of Hillary’s jacket.

By pointing out a few times when Hillary seemed empathy-deficient I’m not implying she’s evil, only that these instances cause me to question how committed she really is to protecting and fighting for children’s and women’s rights and to alleviating poverty.

And then we have Bernie Sanders, not a nominee but still an important player who will be taking his political revolution to Philadelphia for the Democratic Convention on July 25th. He’s been fighting for the same issues since the Sixties, not vacillating once. His whole platform is built on empathy for others, on mitigating others’ suffering by working toward social justice in the realms of economy, public education, healthcare, gender and race.

By informing the public of things previously not widely understood – like the meaning of Democratic Socialism and superdelegates’ superhuman sway – he called attention to the ways corporate politics mislead and manipulate the public. In doing so, he made enemies of prominent leaders of the DNC.

The DNC needed Bernie Sanders, at least in the beginning. Here’s why: Trump entered the RNC race as one of 19 contestants. But Hillary had only one viable opponent, Bernie Sanders – unless you count the 4 unknowns who never appeared in a national poll or participated in a debate.

Her nomination would have been a coronation had she not faced any competition. Some argue it was a coronation and that her title had been decided from the start. If Hillary did have any competition in Sanders, she never seemed to think so.

Two months before her nomination was official and on the heels of losing 20 states to Sanders, she announced to CNN, “I will be the nominee for my party. There is no way that I won’t be.” Considering hard data alone, the race was too close for anyone to call at the time. How could she have been so certain of the outcome if the nomination process wasn’t, to some degree… I don’t know, “rigged”?

Conspiracy or not, the DNC’s scheme to force their Establishment Darling on the public provoked the resistance instead. The RNC’s nomination of someone with zero political experience has had similar effects. If Trump or Hillary wins, it’s America who loses.

Whenever we stand against something instead of for something, we’ve already been defeated by negativity. Our position, rooted in groupthink dynamics, leads to reactionary decision-making and irrationality, is always founded in fear and is thoroughly non-progressive.

I won’t hear that my decision to opt out of the lesser-of-two-evils paradigm and vote for a candidate who isn’t on the ballot means I’m casting a vote for the “other” side or throwing my vote away. This kind of party-line propaganda is a self-perpetuating cycle, one that has played an influential role in landing our great nation in the mess it’s in today. If we keep settling for what we’re given – in this case two candidates disliked by most Americans – nothing can change for the better. The progressive and patriotic move is to reverse this regressive way of thinking by refusing to vote for anyone unworthy of the Office of President.

Fear is a powerful contagion. To stop it from spreading, we must become immune. The only way to do this is to stand together against those who would divide us, believing that the American dream of “liberty and justice for all” can still be realized and that, when it is, every one of us will reap its benefits.

July 16, 2016

Georgia O’Keeffe and the gender debate: Can a woman be great, or only a great woman?

Georgia O'Keefe (Credit: AP/Wikimedia/Salon)

On July 6, 2016, doors opened to a retrospective of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work at the Tate Modern in London, where more than 100 of O’Keeffe’s paintings, spanning six decades, are now on display. In addition, an adjoining room focuses on select portraits Alfred Stieglitz photographed of O’Keeffe, many of them nudes.

Georgia O’Keeffe made her mark as an American artist with paintings of oversized flowers, sun-bleached bones, and curvaceous landscapes. For a century, and possibly because of Stieglitz’s influence, her work has carried with it the interpretation of depicting female genitalia, and emphasizing sexual themes. Throughout her lifetime, O’Keeffe denied her art had anything to do with the female form. This summer, 100 years after the first exhibition of her work, we have the opportunity to take a fresh look atO’Keeffe’s work and the opinions which first shaped it, and see her work anew.

The Tate Modern displays this quote:

Men put me down as the best woman painter…

…I think I’m one of the best painters.

—Georgia O’Keeffe

The Tate is setting the stage to help settle the debate. Is Georgia O’Keeffe the best woman painter or one of the best painters, gender not considered?

O’Keeffe’s story is an interesting one. Stieglitz “discovered” O’Keeffe in 1916, when she sent charcoal sketches to a friend, Anita Pollitzer, in New York City. Though O’Keeffe asked Pollitzer to dispose of them, she couldn’t, and instead took them to noted art dealer and agent, Alfred Stieglitz, to see what he thought of them. He fell in love. He exhibited the sketches in his gallery, Gallery 291, without O’Keeffe’s consent.

Soon, O’Keeffe traveled from Texas, where she was a schoolteacher, to New York, to confront him — he, married and 23 years her senior. He convinced her to be a subject for his photography, which developed into nude portraits, and in 1919, Alfred Stieglitz exhibited photographs he took of O’Keeffe. Certainly, O’Keeffe could not have understood the immense effect they would have upon the interpretation and reception of her own paintings — at least, not as Stieglitz did. He convinced her they would stir up a reputation, and that, the nudes did. His influence on her work continued, and for decades, Stieglitz positioned O’Keeffe’s art and her image to be overtly sexual, to raise an eyebrow and hold attention the way he wanted O’Keeffe to be received. O’Keeffe’s is a story before its time.

The Tate Modern isn’t the only reassessment of O’Keeffe to hit the world this year. In February, Random House released “Georgia” by novelist Dawn Tripp — a fictionalized (and by some accounts feminist) interpretation of O’Keeffe’s story.

As Salon’s March 2016 interview with the author discusses, the story of the novel illuminates O’Keeffe’s New York life, her relationship with Stieglitz, their love affair and the resulting power struggle over her brand. A quote from the book:

“For the next few weeks, I paint flowers. On canvas-covered board, I paint petunias—such a simple household flower, arranged as one would expect a still life to be, but cropped, without a vase or background—just blooms. Then I take those same flowers and translate them onto a thirty-six-by-thirty canvases. Massive. Inflated. Their edges soft, like they’re just coming into form. … I’m nearly finished when Stieglitz comes in. He stops when he sees the canvas.

“What exactly do you think you’re going to do with that?”

I smile at him. “I’m just painting it.”

“I don’t see where it will take you.”

“You mean if it will sell?”

“I just don’t see the point.”

“I want to paint a flower. That is the point. I want to paint it so big that people will have no choice but to stop and look and really see it—as it is. The way I want it to be seen.”

The novel raises a key question: Was Georgia O’Keeffe able to paint and have her paintings be interpreted the way she wanted her work to be received?

In Tripp’s author’s note, she alludes to the work and writings of Barbara Buhler Lynes, an O’Keeffe scholar, the editor of O’Keeffe’s Catalogue Raisonee and a founding curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Lynes’s book, “O’Keeffe, Stieligtz and the Critics, 1916-1929,” opens wide the facts and maps in comprehensive detail how our understanding and assessment of O’Keeffe and her work evolved during those years.

She says many of the critics of that time, commonly male, “assigned O’Keeffe the role of a brainless, malleable, unfulfilled creature that Stieglitz was exploiting in his role as ‘showman.’ He was defining her as an object, his property, and Luhna asserted that his proprietary claim was compromising the source of O’Keeffe’s creativity (her “unconsciousness”) and, possibly, her potential as an artist.” In O’Keeffe’s own words, “The men all thought they were right about everything”; “all the male artists I knew … made it very plain that as a woman I couldn’t hope to make it—I might as well stop painting.”

In the 1920s, after Stieglitz’s first showing of his photographs of O’Keeffe, he exhibited her work at his gallery. Her work was received in light of the photographs he took of her and the “femme fatale” image he created. Lynes says, “Several months after the show O’Keeffe was still fuming about the way her work had been interpreted.” Her artistic talent and paintings were defined as “documents of her sexual feelings,” as women were commonly believed to be inferior in their thinking compared to the more concrete thoughts of men. As Lynes says, “The critics had been unwilling to change their hidebound ways and sought the meaning of O’Keeffe’s art in theories, both psychoanalytical and art historical.”

In light of their responses, it is remarkable that O’Keeffe did not stop painting. Perhaps she went on to paint the subjects she did want to paint. O’Keeffe objected repeatedly to the notion that her work intended to convey female things only: feelings, emotions and sexually-charged genitalia, as Stieglitz’s camps contended for years. Instead she said, on why she paints what she does, “I want to paint in terms of my own thinking, and feeling the facts and things which men know.”

“I have painted what each flower is to me and I have painted it big enough so that others would see what I see.” O’Keeffe stated, “I make them just to express myself—Things I feel and want to say—haven’t words for.”

It is possible that O’Keeffe was not controlled by the critics, but the fact is they affected her and her work. Male critics continued to rally around Stieglitz’s subjugation of O’Keeffe, and, what seems archaic now in Western culture, suggested that “the realization of her creative potential was dependent upon sexual union” with Stieglitz.

Even Achim Borchardt-Hume, the current-day Tate Modern’s director of exhibitions, considers O’Keeffe a key figure to open up the debate, noting that women have been overshadowed by men for decades. “There are questions about value and how we define value, when it comes to the contributions of women,” Borchardt-Hume said in The Telegraph.

The cultural questions remain: why and how has the imbalance lasted for so long? Why would a great athlete like Serena Williams, for example, need to be qualified with “greatest female athlete,” if, in fact, she is one of the greatest athletes of all time? Does every woman who achieves have to be proceeded with the gender-qualifying tag that they are a female, too? How long will the contributions and artistic expressions of women still and truly be less than those of men?

In this case, we must ask, will O’Keeffe and her art forever be defined by the lines Stieglitz drew to box her in?

If we allow O’Keeffe’s life, choices and work to speak, they have a voice clear enough to make a statement on their own. She began to realize her situation, and eventually left New York City, Stieglitz and his chronic infidelity, and set out on her own. She bought her own house 3000 miles away from him in the desert, learned to drive a car, painted what she found interesting and meant something to her, and then, at the end of his life, she chose to return and see him on her own time. The tug and pull of his empty promises no longer worked their magic. His photographs of her, nude and young and exposed, which built his name and eroded hers, became merely facts. They held no power to silence her any longer because she had survived him. She became bold, authentic, purposeful. She had something to say and forged her brand — she rose to the challenge Stieglitz posed. He did not make her nothing, less than him. Instead, the opposite happened — she became something, her work more iconic than his, despite him. She found her own voice and learned to use it. Yes, she was a woman, but that didn’t make her any less an artist than the men.

O’Keeffe perhaps didn’t need Stieglitz to achieve her artistic prime. Maybe she would’ve found herself in New Mexico fueled by Nature and its rugged beauty faster without him. Whether or not the world would’ve embraced a woman and her art without his controversial influence is another question. Today, would we say Georgia O’Keeffe is a great woman artist, or a great artist?

Media’s gift to Trump: Low expectations and, therefore, the ease with which to surpass them

Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump listens to a question during an interview after a rally in Virginia Beach, Va., Monday, July 11, 2016. In presenting himself as the "law and order" candidate for president, Donald Trump portrays a nation of lawlessness and disorder. It does not, though, reflect a trend of declining crime that has been unfolding over 25 years. (AP Photo/Steve Helber) (Credit: AP)

This piece originally appeared on BillMoyers.com.

I was struck over the past 10 days or so by the way the media covered two episodes. The first was Donald Trump’s retweeting of that now-infamous white supremacist meme showing Hillary Clinton against the backdrop of $100 bills with a red six-pointed star slapped beside her, suggesting that she was the puppet of Jewish money. The second was Trump’s press release on the killings of two black men by police and the murders of five police officers in Dallas.

The media response to the first was remarkably tepid, considering that a major-party candidate was spreading a scurrilous anti-Semitic libel and considering that Trump, far from recanting, actually said he regretted that his staff had taken it down. The media response to the second was shock followed by congratulations. They had obviously expected Trump to blame the Black Lives Matter movement for the Dallas killings, as former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani did.

When Trump instead issued a restrained message, expressing a need for moderation, you would have thought he had assumed the mantle of the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., although under the circumstances, this is precisely the kind of statement any normal politician would make.

These media responses are important because I believe they are harbingers of the coverage we are likely to get in the upcoming presidential campaign. The basic rule of media coverage of any personality, political or not, is that coverage always adapts to expectations — even though the expectations are themselves, to some degree, media creations. That rule already benefits Trump since expectations for him are so low that he is more likely to exceed them, as he did after Dallas, or continue to play within them, in which case his egregious behavior and pronouncements cease to be news. Anti-Semitism? Well, to the media that’s just another day in the Trump campaign, certainly not anything about which to hyperventilate.

Since most of us don’t know public figures personally, just about everything we feel about them is based on their portrayals by the media. This is how personae are formed, through broad brushstrokes — a few decisive characteristics, adjectives, behaviors and comments. It’s what we mean when we say that Tom Hanks is a good guy, that George Clooney is civically engaged, that Caitlyn Jenner is brave, that Jennifer Garner is a loving mother — or whatever image has hardened around the celebrity. This is big stuff — PR firms are paid millions to purvey positive images of this sort.

But those images also create expectations, and celebrities inevitably are measured against them. Lance Armstrong was a hero until he turned out to be a cheater and was reviled as a result — not just because he cheated, I think, but also because he betrayed our idealistic vision of him. Ditto O.J. Simpson: He couldn’t have committed murder, said many in the jury pool, because he seemed so nice.

Sometimes these expectations die hard, or don’t die at all. A few months back, quarterback Peyton Manning was accused by a former female trainer at his alma mater, the University of Tennessee, of having exposed himself to her and then ruining her career when she complained about it. But his image and the expectations around it are so impregnable that the story quickly died. By the same token, sometimes less shiny expectations can damage a career. Charlie Sheen’s erratic behavior certainly cost him popularity.

And sometimes the expectations for one individual are perfectly consonant with his or her behavior, while the same behavior would be scandalous for another individual because the expectations of the two are so very different. When Madonna published a book of nude photographs of herself, it was exactly what you would expect Madonna to do. Had Julia Roberts done a similar book, I suspect the reaction would have been puzzlement.

In celebrity, the implications of expectation often don’t matter too much, except perhaps to the trajectory of one’s career. In politics, however, they can mean a great deal because expectations form the baseline from which the media issue their judgments. And those judgments, by osmosis, more often than not become our judgments, too.

Witness the coverage of Donald Trump. Whatever else one might have thought of him before he entered politics — and the adjectives then were likely to be “rich,” “powerful,” “bold,” “independent” — as soon as he declared his presidential candidacy, he established an identity that added the adjectives “heedless,” “unscripted,” “insulting,” “bullying,” and in some precincts, “nativist,” “racist” and “sexist.”

Those seeming negatives have shaped our expectations of him. Like him or hate him — and some people like him precisely because of these things — we believe Trump replaces discipline with bravado and braggadocio. But something is happening in the way the media are handling Trump, albeit subtly, and you can see it in that coverage I mentioned earlier. The media have set the bar so low that we fully expect Trump to be a bigot, as he demonstrated in the anti-Semitic tweet, so criticism of his bigotry is largely relegated to left-wing journalists. It isn’t news. It doesn’t change the narrative.

As for the mainstream media, it is a very short distance from “That’s Trump going ballistic again” to “That’s just Trump being Trump.” But when it comes to drawing political conclusions, it’s all the distance in the world. Similarly, that low bar will inevitably lead to high praise whenever Trump jumps it. A Trump debate in which he is even intelligible or slightly muted would undoubtedly unleash a media torrent of approval: Aha! He is more presidential than we thought. We already are getting a preview of this on the Republican Party side, where any hint of sanity by Trump is embraced in a bear hug. It is part of the process of normalizing him.

But just imagine if Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders had retweeted an anti-Semitic or racist post from a white supremacist website. The media’s expectations of them when it comes to civility are so much higher than their expectations of Trump that I’m not sure Clinton or Sanders’s campaigns could have survived. It would have been the political equivalent of Julia Roberts versus Madonna — so out of character that it might have been game-changing.

Of course, the media have created expectations of Clinton too — namely that she is duplicitous and untrustworthy, and that everything she says and does is dishonest. That is her media persona. It’s unclear whether the media will finally settle into a “That’s just Hillary being Hillary” mode, which could deactivate criticism, or whether they will filter everything she does through their expectations of her untrustworthiness and continue bashing, as they did to Al Gore with his alleged inauthenticity in 2000.

But whatever the media choose to do to her, it is worth noting how different the media expectations of Trump and Clinton are, and how different those expectations may play out. This works to Clinton’s detriment. It is much harder to prove you are honest than to demonstrate you are not racist by throwing a few verbal sops to the Hispanic or black community.

You could call this a double standard. In fact, though, the media have multiple standards — one for each candidate — and candidates face them at their peril. The mainstream media had very high expectations for Marco Rubio, and then he defeated them by turning into a robot. They had high expectations for Jeb Bush, and he defeated them, too. The media had very low expectations for Sanders, and then he exceeded them. Clinton had high expectations of electability and low expectations of personal rectitude, and the media are whipsawing her between the two.

But this much is clear: Low expectations help more than high expectations do. By stringing two sentences together in a debate when there was some doubt as to whether he had mastered the English language, the media anointed George W. Bush the second coming of William Jennings Bryan. Just remember that when Trump’s preposterous pronouncements and behavior are reported as just “Trump being Trump,” or as the media begin to adore him for not seeming to be as racist as he had purported to be, that is what we may be encountering in the 2016 election — a media gift of low expectations to The Donald.

Diversity is making science fiction better: “We’re in a full flowering of potential” for the genre

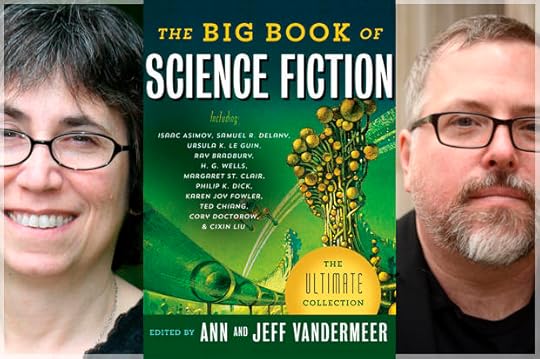

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (Credit: Dana Martin/Kyle Cassidy)

It’s hardly the first, but it’s a gargantuan, wide-ranging volume that anyone with an interest in the field should be aware of. “The Big Book of Science Fiction” collects more than 100 stories, beginning with an H.G.Wells piece from 1897 and closing with a 2002 tale by the Finnish writer Johanna Sinisalo. In between are well-known authors like Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin and William Gibson, as well as writers not associated with the field (Borges, Karen Joy Fowler) and authors from two dozen other countries. (The editors say they wanted to include a story by Robert Heinlein, but were not able to get his estate to give them the rights.)

The anthologists are another reason for excitement: Ann VanderMeer is one of the best-regarded editors in the field – she’s a former editor-in-chief for Weird Tales who now acquires titles for Tor.com. Jeff VanderMeer is the critically acclaimed and bestselling author of the Southern Reach trilogy.

We spoke to the editors from New York, where they were on a book tour. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

There are all kinds of ways to define science fiction, and it’s been described in different ways in different periods. What was your working definition when you put together this book? What was within the bounds for you?

Jeff: There’s always a lot of infighting about that question, both within the genre community and outside of it. So we decided to keep it pretty simple. We didn’t want to make any grand claims, like that Gilgamesh was the first science fiction book, or things like that – the kinds of claims that have been made in the past to legitimize science fiction.

We just thought, really, science-fiction — if you want the most basic definition — is simply any fiction that takes place in the future. We don’t have a lot of steampunk because it seems to have more of a fantasy feel. And there are far-fiction stories where the science is almost indistinguishable from magic, and we thought we’d reserve those stories for a fantasy anthology down the road.

But it eliminates discussions we don’t find that useful about the difference between genre and mainstream.

One of the things that sets your books apart is the huge amount of international science fiction. I wonder if you can talk about a country from which the work has been especially strong, and describe what’s distinctive about it. How different is it from the Anglo-American tradition?

Ann: I think a lot of people can agree that there’s a lot of amazing science fiction that’s come out of Russia in the past few decades. One of the reasons that’s happened is that it was a very good way for the writers in Russia and the Soviet Union to tackle these issues in a way that wasn’t going to get them put into prison. They were still censored in many ways, but that was one thing you saw, not just in the Soviet Union but also Eastern Europe.

We’ve also found many writers from South America – Brazil, Argentina, other countries. We found South American writers to be a little more playful and absurdist.

It sounds like the spirit of Borges is still alive down there.

Jeff: It is true that the Latin American impulse is not driven by a conflict-driven plot or by the kind of adventure tradition that the American pulp fiction still influences, sometimes in very good ways.

There have been political tensions in the field for decades, but the last few years has seen them become more explicit. A group of macho reactionaries tried to take over the Hugo Awards, while the Nebula awards this year went almost entirely to women. Are things coming apart, or being resolved? How significant is all this?

Jeff: As anthologists we take the long view; it’s really useful. There have been Hugo controversies before, like in the ‘50s and ‘60s when the New Wave came around. What really happens is that the controversies get subsumed by whatever becomes successful either critically or commercially. It can seem to the participants that they’re in a life and death struggle. But in the case of the Hugos, it’s really irrelevant to where the energy is in the field.

It’s like what used to happen in the technology and gaming industries – you have a few quote-unquote token women, and that was just fine for the men involved. But once you get beyond 30 or 35 percent, it’s perceived as a threat.

In the last 15 years, women and women of color have come into the field in unprecedented numbers. But what this means is that we’re in a full flowering of potential for science fiction because we’re getting science fiction from so many different kinds of voices. So what this era will be remembered for is that.

As for the Nebulas being all women, I’ll be absolutely honest, in terms of short fiction especially, the writers in science fiction I think are the best are almost all women, for whatever reason. I don’t see that as ideologically based.

Ann: I’m in full agreement with what he’s saying. The way I look at science fiction, I want the world to be as full as it can possibly be. I don’t like to put constrictions and barriers and borders around things. I embrace all the different voices and points of view. I would like everyone to have a piece of the pie.

For a book like this, you’re looking back over a full century, and taking in almost the entire globe. To what extent did your early 21st century perspective — where we’re conscious of climate change — shapes your choices of what was important?

Jeff: Yes, definitely. There are certain things that become more or less relevant and make a story more or less appealing to a modern reader. So if we had two stories of equal quality, we would include the one that had more of an environmental theme. And there were other writers, like F.L. Wallace, who had a story called “Student Body” that was completely overlooked when it came out, but now it’s prescient, seeing the future. While a lot of what was award-winning at that time really doesn’t speak to a modern audience at all.

Ann: It’s quite interesting that there were a lot of stories that did deal with global warming and the environment back then. I also remember a novel I read years ago that made me a lot more conscious of the environment. It was “Nature’s End,” by Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka. I can’t remember details, but I remember how it struck me when I read it, in the ‘80s or ‘90s.

I immediately got involved in the World Wildlife Fund. I also think science fiction, and fiction in general, can make a difference. It can make a difference to how people perceive the world, and it can move them to action. I know that in my case it did.

“There are not a lot of happy people on Wall Street”: Sam Polk opens up about greed, wealth and toxic masculinity

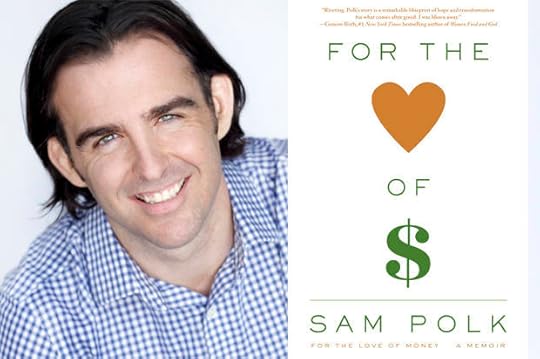

Sam Polk (Credit: Danika Singfield)

In January of 2014, The New York Times published an essay on the cover of its Sunday Review section titled “For the Love of Money.”

“In my last year on Wall Street my bonus was $3.6 million – and I was angry because it wasn’t big enough,” the author, Sam Polk, began. Polk – a former hedge fund trader who left Wall Street and launched the education- and nutrition-focused nonprofit, Groceryships – went on to describe himself as a “giant fireball of greed” who once craved money the way an alcoholic craves a drink.

But the piece was more than just an admission of pathological greed; it was an indictment of a culture filled with – indeed, run by – addicts like Polk. “Wealth addicts are, more than anybody, specifically responsible for the ever widening rift that is tearing apart our once great country,” he wrote. “Only a wealth addict would feel justified in receiving $14 million in compensation – including an $8.5 million bonus – as the McDonald’s C.E.O., Don Thompson, did in 2012, while his company then published a brochure for its work force on how to survive on their low wages. Only a wealth addict would earn hundreds of millions as a hedge-fund manager, and then lobby to maintain a tax loophole that gave him a lower tax rate than his secretary.”

“Look at the magazine covers in any newsstand, plastered with the faces of celebrities and C.E.O.’s; the superrich are our cultural gods,” he continued. “I hope we all confront our part in enabling wealth addicts to exert so much influence over our country.”

The article went viral, reaching more than 1.5 million readers. And in the months that followed, Polk appeared on Tavis Smiley’s show, wrote a follow-up commentary for CNBC, and faced an uncomfortable cross-examination by two hosts on a “Bloomberg” TV show. Now, two and half years later, he has written a memoir.

The core tension of that book, also titled “For the Love of Money,” is similar to the op-ed. Both are about what Polk described in the Times as, “recogniz[ing] my pursuit of wealth as an addiction,” and working to “heal the parts of myself that felt damaged and inadequate, so that I had enough of a core sense of self to walk away.”

But the scope of the book is much wider. There are scenes of childhood trauma and accounts of bouts with bulimia, alcoholism and drug use. There are fistfights, burglaries, sexual escapades and interludes at Columbia University and a Bay-Area tech startup. And, eventually, there is a detailed account of an accelerated career in finance, from Polk’s days as an entry-level financial analyst for Bank of America in Charlotte, North Carolina, to the day he walked out of one of the world’s biggest hedge funds, “and into the bright light of the New York afternoon, with no idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

I recently caught up with the 36-year-old Polk via phone to discuss a book that’s part coming-of-age story, part recovery memoir and part exposé of a rotten, money-drenched Wall Street culture. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Why did you write this book?

I feel like my overriding experience in my twenties, with this desperation for money and success, was true for a lot of people. But I hadn’t read anything that had explored that. So I wanted to write a book that explored my – and our – obsession with money and success, from a super-vulnerable and honest place.

Are you still addicted to money?

No, I’m way more balanced when it comes to money. Before I got to Wall Street, I was obsessed with money and success and I think a lot of that came from my dad, who was, as I said in the op-ed, a Willy Loman-type guy who was an unsuccessful salesman with huge dreams that never seemed to materialize. So, since I was a kid, I always had this idea that money and success would allow me to reach this fantastical place where everything was OK, and I felt like I was enough and beloved and successful. And, of course, you take a kid like that and put him on Wall Street, where the overriding value system is “How much money do you have?” – that created in me this raging desire for money. And that’s what the book is about.

And so when I left [Wall Street], I basically disowned all of that. For the next three years, I did volunteer work, and I ended up starting a nonprofit. And – long story short – two years ago, I had a daughter and …that moment really put things into perspective for me a little bit. I understood that I needed to provide her a living and do my duties as a parent, so I needed to not fully disown that part of myself that was looking for money. But [I] also [needed to] really own this part of me that really wants to help people. I think this new business grew out of that idea of money being a part of a balanced life, as opposed to the primary goal.

Why do you think people responded so strongly to your op-ed?

I think there were a couple reasons. “The Wolf of Wall Street” was out at the time and Wall Street becomes this sort of metaphor for people about people [who] have it all and what unbridled greed and success looks like. One of the benefits of how I wrote that piece was, I think, for the first time, it sort of allowed people into a Wall Street trader’s life in a way that they connected with and understood.

And then secondarily, I do think that as a culture, our primary value is money and success. But it’s sort of like the “Jerry Maguire” memo, “The Things We Think and Do Not Say”: People don’t really talk about how deep their ambition goes, and what it feels like, and how jealous they are of other people who are more successful than them. I did, and people connected with that.

You talk a lot about jealousy both in the op-ed and in the book. Do you think that was something just you were feeling on Wall Street? Is it something people ever talked about?

It’s nothing that is ever talked about. [Laughs.]

And, no, I don’t think it was limited to me. You should see the sort of cold conversations that happen around bonus time, where people are like, “Oh yeah, I got paid really well,” and then you’ll see a smattering of, “Oh, congratulations. That’s really great to hear.” But, behind that, you can tell there’s this deep resentment.

The Wall Street culture you describe is so dominantly male and macho. Perhaps jealousy is a form of weakness that macho men don’t want to admit to. You think that might be part of it?

I think that’s 100 percent right. And, actually, I have a [new] New York Times op-ed about some of those issues – about how male-dominated a culture Wall Street is, and how there’s no place for vulnerability or feelings or, in point of fact, women.

A big chunk of the book relates to women. And, at one point you talk about how you weaned yourself off of watching pornography. For folks who haven’t read the book, why did you include that? Is there a connection between that and the things you talk about in your first op-ed?

For sure. Obviously the biggest theme of the book is money. But the biggest sub-theme is women. Basically those are the two top-of-mind categories for most men in the world. And I wanted to write about both of them, and how both of them can become ways that people use to compensate for an inner lack. And that was certainly true for me. Like I said in the book, with [my college girlfriend] Sloane Taylor, she was this woman who was beautiful and successful and wealthy and looked great on my arm, and that did things for me in the same way that getting a million-dollar bonus did. Which is that it made me feel important and valuable.

To go even further to your point specifically about pornography, we live in this culture that basically objectifies women as sexualized creatures and collections of body parts and then uses them to make ourselves feel good and important, à la trophy wives. And if you think about pornography, as a whole, clearly it can become an addiction. But, even deeper than that, pornography really is, in my mind, less about sex than it is about power, and much more about degrading women in a sexual way to make ourselves feel powerful and important.

Sometimes I think that I sound like a moralizer here, and I’m not. What I am saying is that – I don’t know what the numbers are – something like 80 percent of men regularly look at pornography, but nobody talks about it, even though things like YouPorn are up there with Netflix and Amazon, in terms of the traffic. [This] is having huge repercussions on the subconscious psyche of our culture. And we’re actually not talking about it that much.

When you describe the book in those terms, it’s very much a book about masculinity in America in 2016.

It totally is. I really wanted to write a book that a kid in college – a male kid in college – could read. We hold up these young men [to] an ideal of masculinity that includes no fear, and no backing down, and no expressing emotions. And I know that, for me, I had a tremendous amount of emotion and fear and insecurity. So I tried to be as candid as I could about it in that book, hoping that there were kids out there who were struggling with questions about what to do with their lives, and questions about how to treat women, who maybe could finally get an honest explanation of, at least, what one person did.

Getting back to Wall Street, at one point in the book you talk about how, when you were working in finance, people in the world began to appear to you like “pawns in a trillion-dollar chess game.” As you describe it, you basically started to see the world in terms of dollars and cents. How did working on Wall Street change the way you see the world?

I would say that, in general, the book is about my awakening to a new definition of success that includes making an intentional contribution in the world. People sort of assume that I hate Wall Street, but I don’t. There were so many things that I loved about Wall Street, like how competitive it was, and how smart the people were, and how fun it was to basically play this huge video game for a living. But at the end of the day, the driving value system behind all of it was accumulating money for yourself. My fundamental realization on Wall Street was that, if that was the primary goal in my life, then I would never feel – call it what you will – “fulfilled,” “balanced,” or really, I would never feel like I had spent my brief years in the world wisely.

Despite those aspects of the industry you say you liked, you do come down very hard on Wall Street in the book. At one point you write, “ Our obsessive accumulation of money had led to the widest inequality in centuries. Our hoarding had left millions of people unemployed, starving, and marginalized … Our greed was the source of that poverty. We were the source of that marginalization.” That’s tough stuff. How much responsibility do you think goes to Wall Street for some of those big issues affecting society?

A lot. But I think it’s also broader than that. In some senses, Wall Street is almost like the most concentrated and most emblematic of the type of capitalism that is rife and rampant in the world. And what I mean by that is there are so many industries – whether it’s the food business or the medical business or the oil business – that are really about creating wealth at the expense of other people. So I just think Wall Street is the most concentrated form of that.

But I do think there is responsibility there. When people go to Wall Street, they think that how you judge the quality of a job is basically whether you like your day-to-day skills. Is it fun to break down business reports? Is it fun to trade bonds and trade derivatives? And, if it is, then it’s a great career.

For me, I went through a process that was about saying, “OK, that stuff is fun. But when I start to situate myself in the broader context, then I have to face the reality that my whole job is about [increasing] profit margins and cutting down wages so that the companies I own securities in can be the most profitable. And all of it is about me basically accumulating without really producing anything except a good percentage return, on an annual basis.” And I just came to understand that businesses, I believe, are about solving problems. But businesses have now become something that creates problems. And I would like to be a part of switching that back.

I watched that video of you being interviewed on Bloomberg, and they – unsurprisingly, for that outlet – lay into you pretty hard. Is emblematic of the broader reception you got in the finance industry after your op-ed? Do people see you as a threat to Wall Street’s mystique or credibility?

The first thing I would say is that there’s sort of no underestimating how insular and cloistered and defensive of a culture Wall Street is. And that’s simply by the fact that this is an industry that has earned outsized profits for decades and has been the subject of tremendous amounts of criticism, some deserved and some not. And so [it] has built up defense mechanisms. And so if anyone comes out there saying anything, they’re going to get up in arms and dismissive. And I think that’s largely what a lot of – I would say the broader context on Wall Street – did.

At the same time, I’m very close friends with a lot of people on Wall Street. I got tons of emails from people on Wall Street saying they really identified with what I was doing. I can tell you this, incontrovertibly – at least, in my own mind – there are not a lot of happy people on Wall Street. Most people I know on Wall Street are sad, or wish they were doing something else, or feel trapped by the money. So what I’m talking about, I think, has some resonance for them. And it doesn’t mean people have to … leave their finance careers. But it does mean taking responsibility and making space for the parts of themselves that aren’t acknowledged in Wall Street culture, currently.

In both the book and the op-ed, you describe a scene at the hedge fund when you said during a meeting, “Don’t you think regulations make sense for the system as a whole?” And your boss says, “I don’t have the brain capacity to think about the system as a whole. All I’m concerned with is how this affects our company.” Here’s your chance: What reforms would you prescribe for America or Wall Street to make it a healthier, better place?

I would say, especially for America, it goes back to what I was saying about businesses solving problems rather than creating them. But think about how many businesses externalize problems. Exxon externalizes global warming and Coca Cola externalizes obesity and McDonald’s, in addition to externalizing obesity, has this famous help line for their workers to call in to figure out what government subsidies they can augment their paycheck with, so they can survive, basically. And so the first and foremost thing that I think needs to happen is for – and this sounds a little lofty and grandiose – is for capitalism to be redefined so that each business becomes fully internalized and fully-self-sustaining.

And then there’s obviously a huge amount of work that needs to be done in leveling the playing field. One of the things I’ll talk about in this [latest] New York Times article is about how Wall Street sees itself as this incredibly meritocratic culture. But, in truth, it’s more like the Andover lacrosse team – competitive, but only [within] a certain subset of the population. There’s very few women there. There’s very little diversity on Wall Street. So that needs to be opened up.

But I think the bigger sort of thing, going back to your question about this hedge fund, is – and this sounds lofty and grandiose, as well – the two sort of overriding characteristics of this country, of this culture, are, on one hand, this individualism that’s about self-reliance and free markets and free enterprise. And then on the other side is this idea of democracy and “Every life matters” and “Each person has exactly the same vote.” You could sum that all up as being “We’re all in this together.”

And I think that’s what my old boss’s comment spoke to: which is that Wall Street has become a place of individualism without any sense of how it impacts the rest of the people in that culture. And so I’m hoping that, through this book, but also through this new business that I’m starting, to provide an example of a different kind of corporation, that can be about a fully internalized company solving a problem and making life better for everyone that intersects with it. Rather than a vampire squid sucking the life out of it.

Do you think this country, as a whole, is addicted to wealth?

That would be a good question if everybody had all these savings and all this extra wealth but then kept working themselves to the bone to get more. But that’s actually not how it is. We live in a country where 50 million people are on food stamps, and [a huge] percent of people claim to be living paycheck to paycheck, and where the entire middle class has been basically crushed, so now it basically seems like you’re either poor or super-rich.

And [then there is] what the sort of lower end of the One Percent feels like. Most people that are making $500,000 a year – they definitely feel like they’re not making enough, and some of that is because of the wealth addiction. But also some of it is it because private schools cost a lot, and the cost of living for living in a good school district has gone up. So all of that is to say, people’s obsession with wealth, in some sense, is merited. Because we do have a culture of haves and have-nots.

The words “Wall Street” carry all kinds of meaning in our culture. They mean one thing to Bernie Sanders and another thing to the hosts of that Bloomberg who interviewed you. What do those two words mean to you?

I think it’s a metaphor for what’s best and worst about our culture. We are a culture of “manifest destiny,” and creating the largest economy in the world and the most successful companies. And a lot of that is embodied by Wall Street.

At the same time, we also, as a culture, tend to skew a little to the selfish and the greedy. And [we] forget to take care of people that maybe haven’t had the same luck and benefits as everyone else. And so I do think Wall Street becomes this sort of [“Great Gatsby”-esque] green light that people are both deeply envious of and also very angry at.

Military violence and scandal: We need a public discussion of the sexual assault epidemic in our armed forces

Army Cadets stand in formation, Dec. 12, 2015, in Philadelphia. (Credit: AP/Matt Slocum)

The understandable and natural impulse to honor sacrifice, and award valor, has mutated into a cover story for high levels of violence against innocent people, especially women. It has become nearly impossible to travel anywhere in the United States, or go a few days, without hearing maudlin amplification of tributes to the “heroes” of the American military. Many active duty servicemen and women, and combat veterans, are certainly worthy of praise and gratitude, but the insistence on treating every current and former military member as a secular god, as ritual in the ongoing glorification of the military, allows horrific problems of rape, sexual abuse, and domestic violence to fester and bleed.

The tragic irony is that the victims of America’s societal negligence on military scandals are military members themselves, along with the closely related group who sacrifice in silence – military family members.

It is hardly a surprise that the television media has emphasized Micah Johnson’s connections with black militancy, rather than his status as an Army veteran. Clearly, Johnson was not a good representation of the military, and he was not the typical veteran. There are millions of veterans in the United States, and the problem with assigning the honorific “hero” to each one is that it denies the human and historical reality that any collection of people – large or small – usually contains the ethical and the evil; the kind and the cruel. Johnson, because of his slaughter of innocent people, is among the worst of the worst, but there are elements of his past that, as uncomfortable as it makes people, are not foreign to American military culture.

Those elements deserve scrutiny, rather than shadowing. The need for an honest evaluation of the military’s flaws and failures becomes an imperative for those with a sincere and substantive desire to “support the troops.”

Superiors of Johnson accused the deceased murderer of “egregious sexual harassment,” while he was serving deployment in Afghanistan. They recommended he receive a dishonorable discharge, but for reasons unknown to them, he left the military with an honorable discharge. Sexual harassment, and even assault, is a crime familiar to many women veterans, and the consistent ability of assailants to escape any and all consequences for their sinister acts of sadism, is a continual source of suffering for women who have already endured pain and trauma.

Recent research from the Department of Veterans Affairs indicates that two out of every five military women experience sexual trauma during service. An inquiry into the crisis of sexual assault from former Congresswoman Jane Harman found that in one California veterans hospital, four out of every ten women were raped by fellow soldiers. When sexual violence against men becomes part of the calculus, there are an estimated 38 rapes in the military every single day. Following the physical assault, there is often a bureaucratic rape of emotional and mental health. The RAND Corporation discovered that 62 percent of women who reported their victimization to military superiors experienced professional and social retaliation.

Public discussion of the sexual assault epidemic in the military is rarely audible over the cacophony of phony patriotic imbecility, disguised as indignation. The cheap “How dare you criticize our heroes” sentimentality deflects attention away from the reality that “our heroes” are the ones whose lives undergo destruction at the hands of the minority of sexual predators in the military, and the institutional bias and corruption shielding them from punishment. Genuine patriotism would provide protection for the military members who, in their voluntary duty, experience the worst form of violent and bureaucratic betrayal.

Micah Johnson’s next door neighbor claims that Johnson was “not the same when he came back from Afghanistan,” and according to his mother, he transformed from an “extrovert” into a “hermit.” Several black activist organizations banned Johnson from membership after learning of his sexual harassment, and deemed him “unstable” and “unfit” for participation in their political activity.

Few people have an awareness of how combat changes the personality and character of individuals more than military families. Too often they are not merely observing subtle changes in behavior, but painfully acclimating themselves to a war they never knew they would have to fight. Stacy Bannerman, the leading advocate for military spouses and children who suffer abuse and neglect, calls this thickly curtained theater of war “Homefront 911,” in her latest book detailing “how the families of our veterans are wounded by our wars.”

What Bannerman identifies as the “invisible line item” in the bill for America’s post-9/11 wars is the thousands of women and children who become victims when their partners and fathers return from the battlefield, often with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or Traumatic Brain Injury, and targets for assault and violence. Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs studies both demonstrate that rates of domestic violence are dramatically higher in homes where one parent served in a combat role, and the Military Times recently reported that since 2009, child abuse in Army families has risen by a staggering 40 percent.

A Yale University study in 1994 revealed that combat veterans were responsible for 21 percent of domestic violence cases at the time. Bannerman believes those numbers have held steady, given that VA research indicates that the majority of combat veterans with PTSD commit, at least, one act of interpersonal violence in their first post-deployment year.

Bannerman is the author of the Kristy Huddleston Act. She named it to honor a close friend who was murdered by her husband, an Iraq War veteran, who did multiple tours in an infantry unit. The Kristy Huddleston act would mandate that the Department of Veterans Affairs allocate transition funds to support military families, and veterans’ caregivers, along with medical care and mental health treatment providers, to assist those escaping from a veteran found guilty of spousal violence or child abuse. Bannerman has personally met with 80 members of Congress, and several senators, to argue for the bill. At this point, none of them have agreed to sponsor it.

The consistent and cowardly refusal of the United States government to take aggressive action to protect women in the military, and the women and children of military veterans, exposes the mawkish anthems for “our heroes” as hollow, and convicts the legislative and executive branches of government as guilty of criminal negligence.

The political indictment implicates the American people, because it is largely due to their religious zeal for all things military that the media self-imposes a gag order on military scandal and Congress retreats from its responsibilities to reduce harm and save lives.

The American people chose to react to the simultaneous prosecution of two wars subsequent to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 by tying a yellow ribbon around their eyes, inserting their fingers in their ears, and chanting “hero.” Military members who act with honor and integrity deserve respect and commendation, but those who abuse their power and enlarge the casualty count of war deserve harsh penalty. Ordinary Americans, influential pundits and powerful politicians all claim to revere the troops and their families, but seem satisfied to ignore the injustice inflicted on them every single day.

Micah Johnson is a rare case. The overwhelming majority of combat veterans are not going to massacre innocent people, but irrefutable evidence, along with the heartbroken testimonies of thousands of women and children, demonstrate that too many of them will extend the blast radius of war into the lives of people most worthy of safety.

Every day that America refuses to act and react to the vicious cycle of victimization resulting from its own wars, in the words of Stacy Bannerman, “We lose more lives.”

“He’s a solid, solid person”: Donald Trump officially introduces Mike Pence as his running mate

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, right, talks with Gov. Mike Pence, R-Ind., during a campaign event to announce Pence as the vice presidential running mate on, Saturday, July 16, 2016, in New York. Trump introduced Pence as his running mate calling him "my partner in this campaign" and his first and best choice to join him on a winning Republican presidential ticket. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci) (Credit: AP)

Donald Trump introduced Indiana Gov. Mike Pence as his running mate on Saturday, calling him “my partner in this campaign” and his first and best choice to join him on a winning Republican presidential ticket.

Skipping the traditional massive rally in favor of a low-key announcement in a Manhattan hotel, Trump tried to draw a sharp contrast between Pence, a soft-spoken conservative, and Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential candidate. In fact, he spent about as much time lambasting Clinton as praising Pence, declaring she had led President Barack Obama “down a horrible path” abroad.

He said Pence would stand up to America’s enemies and that he and the governor represent “the law-and-order candidates” at home.

“What a difference between crooked Hillary Clinton and Mike Pence,” Trump said. He added: “He’s a solid, solid person.”

Pence, standing alone in front of American flags, hewed closely to the populist themes that Trump has voiced on the campaign trail, describing himself as “really just a small-town boy.” He praised Trump effusively as “a good man,” a fighter, a legendary businessman and a patriotic American.

“The American people are tired,” Pence said. “We’re tired of being told that this is as good as it gets. We’re tired of having politicians in both parties in Washington, D.C., telling us we’ll get to those problems tomorrow.”

The joint appearance was intended to catapult the party toward a successful and unified Republican National Convention, which kicks off in Cleveland on Monday. Trump conceded that one of the reasons he’d selected Pence was to promote unity within the Republican Party, left deeply fractured by Trump’s ascent.

“So many people have said ‘party unity,’ because I’m an outsider,” Trump said. “I want to be an outsider.”

Yet the announcement lacked much of the stagecraft typically associated with the public unveiling of a running mate, one of the most significant moments in a presidential campaign’s control.

The two did not walk out together, appearing at each other’s side only after Trump delivered a rambling 28-minute address that included a plug for his new hotel in Washington. And when they shook hands, with the political world watching, it was only for a few seconds before Trump left the podium.

Pence, whose calm demeanor forms a marked counterpoint to the fiery Trump, was chosen in part to ease concerns in some GOP corners about the billionaire’s impulsive style and lack of political experience. A steady conservative with extensive governing experience, Pence may also serve to reassure Republicans who are skeptical about Trump’s conservative bona fides.

Brandishing his running mate’s job-creating credentials, Trump ticked through a list of statistics he said showed how Pence had pulled Indiana out of economic recessions: an unemployment rate that fell to less than 5 percent on his watch, an uptick in the labor force and a decrease in Indiana residents on unemployment insurance.

“This is the primary reason I wanted Mike – other than that he looks very good, other than he’s got an incredible family, and incredible wife,” Trump said. He predicted that Pence would have won re-election as governor, were he not running for vice president.

The Trump-Pence event offered Americans the first glimpse at what the 2016 Republican presidential ticket will look like, barring the unexpected. Just as Trump was settling on Pence, Republicans gathering in Cleveland essentially quelled the movement to oust Trump at the convention, all but assuring he’ll be the GOP nominee.

“They got crushed,” Trump said. “And they got crushed immediately, because people want what we’re saying to happen.”

The Indiana governor is well-regarded by evangelical Christians, particularly after signing a law that critics said would allow businesses to deny service to gay people for religious reasons. But his hardline ideology is also at odds with Trump, who has largely avoided wading into social issues.

Clinton’s team was already painting Pence’s conservative social viewpoints as out of step with the mainstream. Her campaign also seized on Trump’s chaotic process for selecting and announcing his pick, painting Trump in a web video released Saturday as “Always divisive. Not so decisive.”

Trump’s formal announcement capped a frenzied few days in the presidential campaign, as early reports that Trump has settled on Pence threw speculation into overdrive. After days of his aides saying he hadn’t made a final decision, the billionaire called Pence Thursday afternoon to offer him the job, but hours later postponed their first appearance after a truck attack killed 84 people in Nice, France.

Trump had spent weeks vetting vice presidential contenders, including former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, and only zeroed in on Pence in recent days. Pence, meanwhile, had faced a Friday deadline to withdraw from his re-election race for governor so he could run for vice president; his aides filed the paperwork about an hour before the cutoff.

In choosing Pence, Trump appeared to be looking past their numerous policy differences.

The Indiana governor has been a longtime advocate of trade deals such as NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, both aggressively opposed by Trump. He’s been critical of Trump’s proposed temporary ban on foreign Muslims entering the U.S., calling the idea “offensive and unconstitutional.” Pence also endorsed Sen. Ted Cruz instead of Trump ahead of Indiana’s presidential primary.

Does the Trumpence nightmare coalition have a chance? Yeah, because it’s 2016 and chaos reigns

Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton (Credit: Reuters/Scott Audette/Mike Blake/Photo montage by Salon)

So here we are, at a major pivot point in the unfolding narrative of America’s Stupidest Election Ever. (Admittedly I haven’t gone back and taken a hard look at “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.”) Our two major political parties head into their conventions with two deeply flawed and widely disliked candidates, who despite their divergent styles and opposed positions come from the same elite caste in American life, and have known each other for years. There has been yet another presumed or probable terrorist attack in France, a gruesome event whose timing in terms of the American presidential election was coincidental, but whose symbolism was not. If the deranged Islamic radicals of Europe don’t actually support Donald Trump, they are nonetheless doing their damndest to get him elected.

Halloween comes to Cleveland a little early this year. Trump will accept the Republican nomination next week and so align himself (if only hypothetically) with a ludicrous platform crafted by party activists apparently coughed up by the 1988 Pat Robertson campaign. Beyond incorporating Trump’s famous wall and dropping all references to the GOP’s traditional free-trade agenda, it has almost nothing to do with the guy at the top of the ticket. The Republican platform won’t be final until delegates adopt it, but it has already made headlines for going “Back to the Future” in spectacular fashion on a whole range of social and cultural issues, mostly things Trump conspicuously doesn’t care about. Not merely has the GOP base rejected the more inclusive approach recommended by party chair Reince Priebus’ “autopsy” commission after the 2012 election, it seems to have embraced the most hard-right social vision in recent American history.

Abortion must be outlawed by constitutional amendment, according to the GOP platform, but at least that one is nothing new. Same-sex marriage also must be undone by the same mechanism, despite the fact that most of the country — Donald Trump included — has clearly accepted the new reality and moved on. Transgender rights are specifically rejected. Legislators are urged to use religion as a guide, although it’s a safe bet that only some religions are acceptable. The Bible should be taught in public school, and judges should respect “traditional family values.” Pornography is defined as a “public menace,” parents should be free to seek “conversion therapy” for LGBT children and a theory is advanced that the offspring of “natural marriage” between a man and a woman are less likely to become substance abusers. Change a couple of proper nouns and ISIS would endorse the whole damn thing.

That goes way beyond trying to lose the 2008 and 2012 elections all over again (and worse), but with more enthusiasm. This is like trying to lose the 1884 election in some alternate universe scripted by Neil Gaiman, or the election in “The Purge: Election Year.” The only reason there isn’t something in there about outlawing the teaching of evolution or stoning adulterers in public is that they didn’t get around to it. Dare to dream, people! There’s an entire week of ideological contact-high and lakefront BBQ ahead of you. You’ve still got time.

One could make almost the same observation in reverse, with a lower degree of cognitive dissonance, about the relationship between Hillary Clinton and the Democratic platform. Whether this represents a strategic shift or just a rhetorical bone being tossed to Bernie Sanders and his supporters, Clinton has abruptly chosen to embrace numerous issues she resisted during the primary campaign: A $15 minimum wage (at least in theory), free tuition for in-state students at public colleges and universities, an expanded “public option” to fill the Obamacare gap. At the very least, the stark contrast between the two party platforms and the worldviews they espouse should remind people who take a deeply cynical view of our paralyzed bipartisan system — people like me, to be fair — that it is not entirely devoid of ideological substance.

If the party platforms meant anything, and if the 2016 election were actually being conducted as a somewhat conscious and coherent debate on the issues, it would be a slam dunk. But as my elderly Scandinavian landlord used to say, if his grandmother had wheels she’d be a wheelbarrow. Elections are almost never about stuff like that and almost always about emotion and symbolism. (Brexit being a recent case in point.) And I’m not sure it’s fair to blame the voters for that, or at least not entirely. When you look at Trump and Clinton, two of the slipperiest people ever to run for high office, you can only conclude that their purported positions on almost everything must be taken with immense blocks of salt, and that what either of them would actually do as president remains a mystery. Which variety of disturbing enigma do you prefer: Orange-hued reality-TV blusterbox or steel-jawed Ladytron?

As this week’s disturbing poll numbers showing Trump and Clinton dead even in several swing states should remind us, nothing is certain and the only safe bet in 2016 is to expect the unexpected. I’ll be in Cleveland this coming week, along with my colleagues Sean Illing, Amanda Marcotte and Ben Norton, and about half the Western world’s press corps. (Most of us will reconvene in Philadelphia the week after that, with considerably lower expectations.) What all that cumulative pontification will do to the atmosphere during a sweltering summer week in northeast Ohio I have no idea. Nor do I know what the Republican National Convention will actually be like, inside and outside Quicken Loans Arena, No, seriously — Quicken Loans Arena! You can’t make this stuff up.

As for what this year’s GOP convention will mean, in the somewhat longer arc of American political history, we won’t learn that next week or for quite a while thereafter. Will Cleveland 2016 be an epoch-shaping event, like Chicago 1968 or Houston 1992? Or an anomalous blip that is soon forgotten? Do you remember anything about the John Kerry Democratic convention of 2004? I’m already sorry I brought it up.

It’s tempting to overpredict this year’s Trump-Pence Quicken Loans fiesta, and to heap too much significance on what is usually a stage-managed event that for once feels charged with weirdness and danger. Speaking of which, are those two syllables, Trump and Pence, vaguely salacious when put together? Trump-Pence. Trumpence. It has a naughty Victorian flavor: The tuppence you use to pay a strumpet is a Trumpence.

If Donald Trump has an Achilles’ heel — well, we know it’s not his propensity to say outrageous and offensive things. But he gets less and less comfortable as he gets dragged back toward normal political strategies and orthodox positions, and we can feel that happening a little. I find myself surprised that Trump actually picked Mike Pence, because the Indiana governor is such a boring and predictable choice, and you can’t accuse Trump of being either of those things. If Pence represents a victory for “politics as usual” within the Trump camp, which seems to be the predominant media spin, it’s pretty much the first. I’m halfway persuaded by the MSNBC truther theory that Trump spent Thursday night trying to undo the decision. Trump hates measured, stealthoid, two-faced conservative dudes like Mike Pence. Running with a fatuous pseudo-intellectual like Newt Gingrich or a pompous blowhard like Chris Christie is much more his style.

I don’t imagine Trump gives a crap about what the Republican platform says, or is likely to read it. Written by politicians! Sad! But by attaching himself to Pence and to the most delusional, crazy-town fringe of the Republican right, Trump has leapt right over the so-called mainstream of the Bush family and Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan and reforged the GOP as a nightmare coalition of the very worst kinds of Americans. I’m not letting the supposedly normal, grownup Republicans off the hook — they are the next worst kinds of Americans. It was their pandering and hypocrisy and consumer-grade evil over the past couple of decades that made this all possible, and the fact that they have to spend this week sulking at home atop their piles of money is a better fate than they deserve.