Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 709

July 24, 2016

Debacle in Baltimore: Prosecutors, part of the problem, struggle with solutions

Baltimore state's attorney Marilyn Mosby (Credit: AP/Alex Brandon)

Last May, cheers went up across Baltimore after State’s Attorney Marilyn J. Mosby, the city’s top prosecutor, announced charges against six officers involved in the arrest of Freddie Gray, whose death from injuries suffered in police custody sparked protests and riots that dominated national media. Impunity is the norm for abusive police. It seemed that a chance for justice had arrived.

“To the people of Baltimore and the demonstrators across America: I heard your call for ‘No justice, no peace,’” Mosby declared after days of unrest. “Your peace is sincerely needed as I work to deliver justice on behalf of this young man.”

The national spotlight on the trials, however, has faded as prosecutors have gone on to so far deliver a zero-for-four debacle, rife with accusations of misleading a grand jury and failures to turn over information to defense lawyers that elicited rebukes from Judge Barry G. Williams — a judge whose old job was prosecuting bad cops. Last Monday, Mosby’s office failed to win its third conviction against an officer, in addition to a fourth case declared a mistrial. It was readymade fodder for conservative Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke, who used his primetime slot at the Republican National Convention to condemn “activist” Mosby for “malicious prosecution.”

Defense lawyers, however, say that the overcharging and discovery violations now drawing criticism in the Gray trials are perpetrated as a matter of course against poor black defendants. Beyond predictable Republican and police union attacks on Mosby, the trials point to the limited ability of criminal prosecution to fix the criminal justice system — and also to the ways in which prosecutors, winning sentences that imprison Baltimoreans en masse, are in reality a big part of the problem.

It was apparently Mosby, after all, who had requested that police flood the West Baltimore intersection where Gray was arrested in response to local complaints about drug dealing. If the police officers who arrested Gray were following orders, carrying out drug-war business as usual, then Mosby, and the entire criminal justice system, have a lot to answer for.

Mosby, hailed as Black Lives Matter’s first courtroom hero, has received staunch support from many in the city, including the local chapter of the NAACP and Gray’s family. But defense lawyers complain that an office that has won national attention for prosecuting these officers has done little to nothing to alter a cash bail system that keeps huge numbers of poor defendants incarcerated pre-trial, and charge that they fight defense efforts to gain access to police disciplinary records.

Todd Oppenheim, a local public defender and outspoken criminal justice critic, contends that the officer trials have “completely occupied” a prosecutor’s office that otherwise has little to show in the way “of new approaches to the system.”

A unit dedicated to righting wrongful convictions, the crown jewel of any reform prosecutor’s office, has helped exonerate just one person.

Mosby’s office could not comment on the Gray prosecutions because the cases are subject to a gag order. But they said they are making headway toward reform: the unit dedicated to righting wrongful convictions has been revamped, they have received a grant to create a program to decrease the number of poor people held pre-trial, and they are diverting first-time low-level drug dealers from prison and into jobs.

“As prosecutors we have an obligation to participate in reforming the criminal justice system and lead the charge to create a system that will benefit the citizens we serve,” said Mosby, in a statement forwarded to Salon by her office.

Tammy Brown, the State’s Attorney’s chief of external affairs, points to the diversion program AIM to B’MORE, which she calls an effort “to target individuals who are selling drugs to get them out, and get them a job in lieu of selling drugs.”

It’s a laudable idea but, upon closer inspection, a modest one. Last year, the program had thirty participants, she says, and has doubled in size this year. In Baltimore’s vast system that’s a small drop in a very large bucket: black men, charged with crimes large and small, continue to cycle through the city’s system—with little to nothing to show in the way of checking the street violence that pervades poor neighborhoods like Gray’s.

The city’s bail system, according to Maryland Public Defender Paul B. DeWolfe, is a major culprit. Defendants are incarcerated simply because they are too poor to pay, he says, resulting in a bloated jail population 85 to 95-percent filled with pre-trial detainees yet to be found guilty of anything. Judges set bail but prosecutors can make recommendations. Mosby’s office, he says, has not yet taken meaningful action.

“If you’re poor, you sit in cages. If you have money, you get released,” says DeWolfe. “That’s unfair.”

Oppenheim points to Allen Bullock, whose case received widespread attention when he was brought up on major charges after smashing a traffic cone through a police car windshield during the riots. A judge agreed to a plea deal that included six months in jail. Mosby’s prosecutors had sought more than nine years in prison, and he was held on $500,000 bail, notably higher than that of officers charged in connection with Gray’s death.

“They definitely wanted to make an example of him,” says Bullock’s attorney, J. Wyndal Gordon. Gordon is a supporter of the Gray prosecutions but, in a follow up email, believes that the prosecution of Bullock was intended to “neutralize the effects of some of the reactions” to them and stifle street protest.

Brown contends that a risk-assessment tool under development in Mosby’s office will decrease the number of defendants held pre-trial, and says that their office did make an effort to get low-level offenders out of jail during the riots. DeWolfe says that he’d welcome any improvement but that none has yet materialized, and that he’s “not aware of any request that prosecutors made during those riots, or uprisings, to recommend that people get released.”

Rather, he says that defenders had to file more than 90 habeas corpus petitions to spring people held without a hearing. Brown says that DeWolfe might be unaware of their efforts because prosecutors made their recommendations to release prisoners to the Court Commissioner, before defenders would have been involved.

Untold others remain in prison for crimes that they never committed, and Mosby so far boasts a meagre track record on righting these past injustices.

On May 11, Malcolm Jabbar Bryant, convicted in 1999 for the murder of a teenage girl he apparently did not commit, walked free, making him the sole person that the State’s Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit has helped to exonerate under Mosby, according to unit chief Lauren Lipscomb.

What’s more, Bryant’s case was remarkably straightforward. DNA from the victim’s nail clippings and t-shirt pointed to someone else. In many cases, however, proving that someone is definitively innocent is rather difficult: bad convictions often don’t include much evidence at all, let alone something exculpatory like DNA. In other words, had the teenage girl’s true killer not left DNA evidence, Bryant, convicted on the basis of a shaky eyewitness identification, would likely still be in prison.

Asked whether the unit would support exonerations in cases where a defendant should simply have never been found guilty in the first place, Lipscomb demurred.

“We do not review cases just because they’re weak,” she says. “We’re talking about cases where the facts have been presented to a jury.”

Bryant, of course, was convicted by a jury as well.

Lipscomb says that her unit has three attorneys, an intern and three support staff, and that it’s work is just getting off the ground. But it also has other major responsibilities, including probation enforcement. They currently have just one case under investigation, eight under initial review, and eight that have been reinvestigated and closed.

“They are a new concept,” says Lipscomb, referring to conviction integrity units, “and we are all sort of developing what the best model is in terms of functioning within prosecutor offices.”

Shawn Armbrust, executive director of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project, says that the unit has recently shown a greater interest in collaboration. It is still too small, however, to right what are likely a large number of wrongful convictions in the city.

“I think they’re trying to do the right thing, but it’s a small unit. It doesn’t have the resources to accomplish as much as larger, better-funded units,” emails Armbrust.

Asked whether the unit is developing best practices to help prevent future wrongful convictions, Lipscomb said they are but could not yet point to any specific measures. Remarkably, Mosby has said that the Bryant case did not shake her faith in eyewitness testimony, which can be unreliable and appears to contribute to the majority of wrongful convictions nationwide.

One basic step would be to ensure that police with a track record of lying are not called to the stand. Defense attorneys, however, say that’s not happening: prosecutors, they say, routinely fail to abide by their obligations under what is known as the Brady Rule, which requires that prosecutors turn over to the defense any potentially exculpatory evidence—including evidence of officer wrongdoing that might undermine the credibility of their testimony.

“We fight that tooth and nail, and they resist every attempt at turning over evidence of police dishonesty” and “police misconduct,” says DeWolfe.

Deborah Levi, a Baltimore public defender, says that prosecutors don’t have a regular system to determine whether such officer disciplinary records exist. In order for defense attorneys to even make the case to a judge that they should get files on dirty cops, Levi says that they must look out for rumors, and scour newspaper articles and federal court filings. When defense lawyers do move to request access to records, she says, and then to bring them into court, prosecutors inevitably mount an opposition.

“They argue against disclosure without having scrutinized the file,” says Levi. “That has been my experience in litigation.”

According to an email from a member of the State’s Attorney’s office obtained by Salon, prosecutors do not even have direct access to the police disciplinary record system.

Other discovery violations are routine as well, says Levi: prosecutors, she says, have repeatedly failed to disclose cases where police used a tool called Stingray, which simulates a cell tower to track people’s locations, without a warrant. Brown puts the blame for that on police, who she says that prosecutors rely on to alert them to the device’s use.

“When our prosecutors are made aware that a detective used a cell-site stimulator, it is disclosed,” emails Brown. “We are currently working with the Police Department to improve upon the process to better obtain this information in order to comply with the law.”

In the Gray cases, Mosby’s office finds itself in the unusual position of prosecuting alleged police abuse instead of defending it. The result, says Oppenheim, is hypocritical. Legal experts were shocked, for example, when prosecutors argued that Officer Edward Nero’s arrest of Gray not only lacked probable cause but was itself a criminal act on the officer’s part. According to Oppenheim, the same State’s Attorney’s office on a typical day not only defends bad arrests and searches but fights to ensure that evidence secured from them is admissible in court. Prosecutors, he says, are in the Gray trials making arguments about police misconduct that directly contradict how they approach everyday matters in the courtroom, when prosecutors and police work side by side.

According to critics, Mosby’s office is losing the Gray prosecutions for a simple reason: it does not have anywhere near sufficient evidence to prove that officers committed the alleged crimes beyond a reasonable doubt.

“These were always very difficult cases to prove, and the fact of the matter is there’s just not a whole lot of evidence from which to prove them,” says David Jaros, a professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law.

The real lessons from the Gray prosecutions, however, are already being lost. National and local Republicans have piled on, using the trials to delegitimize Black Lives Matter. So has the local Fraternal Order of Police, whose concern for defendants’ rights is limited to cases where cops are on trial.

“Given what we’ve learned about how the criminal justice system is functioning,” says Jaros, “the question is what are policymakers going to do about it? And to the extent that this case reveals the limitations of using the criminal justice system, and a prosecution, to resolve these issues, we have to ask, what other mechanisms are we going to identify?”

The Baltimore FOP, for one, doesn’t seem interested in any mechanisms at all: they have filed a lawsuit aimed at blocking civilian review board access to internal affairs records.

Across the country, the question of prosecuting cops for misconduct has stood in as a high-stakes symbol for larger problems plaguing the criminal justice system, from aggressive policing to mass incarceration. These problems are rooted in state and national policies but have their greatest impact in local criminal justice systems led by law enforcement officials like Mosby. Whatever one’s feeling about the wisdom of the Gray prosecutions, his death and what followed are an unsettling reminder that the system remains broken across the board and that solutions currently on the table aren’t up to the job.

July 23, 2016

In my genes: Adventures in DNA testing

(Credit: takahashi_kei via iStock)

When I lived in New York City in the early 1980’s, in Brooklyn — long before it became hipster central and preening ground, back when no one would even visit you there, even if you threw a party — I would take a long subway journey once a week, on the E and the F trains, from Park Slope to Kew Gardens, Queens, where I visited a therapist to discuss myself, my life and how I might get it pointed in a different and happier direction. On one such afternoon, I was reading “Lolita” on the F train, which elicited a friendly comment from a young woman nearby; a conversation ensued, and by the time she got out, somewhere in Manhattan, I had entered her phone number into the back flap of my book with a golf pencil, lending to the rest of my afternoon a certain frisson of excitement and possibility. I did not confess my mini triumph to my therapist, Rene, as she was rather old fashioned and direct, and most likely would have asked me, in her gruff, smoky voice, something like, “Are you going to have sex with her?”, which would have forced me into some sort of fumbling answer ending with, “Probably not. But at least I might see her again.”

Which I did. From my loveless hovel in Brooklyn Heights — a single room rented from a recent divorcée and her depressed, all-dressed-in-black daughter — I called the number, we talked and she invited me over for tea in another, not so far other, part of Brooklyn. Perhaps I walked. It took several rings of the bell to get buzzed in, and when I went up, she appeared sleepy, as if she had been woken from a nap. The apartment, like many in New York, was pleasantly overheated. She was a Latina, of Cuban descent, I learned, had lovely, caramel-colored skin, much in evidence below her faded blue gym shorts, with that old-fashioned white piping around the edges. She served tea, and we sat at the kitchen table and talked, but she still seemed sleepy, vaguely disinterested and perhaps surprised that I had actually shown up. In the course of our chat she mentioned a sometimes-boyfriend, and casually mentioned that he sometimes carried a gun. I looked uneasily toward the door, of which there was only one. He had a temper, she told me. Why was she telling me this? The conversation eventually turned to me, and at some point she observed, also casually, that I was really “White bread.”

“Really?” I asked. “What do you mean?” She didn’t feel explanation was necessary, simply repeated the phrase, the subtext of which, I inferred, was that I out of the running for romance. I stayed a while longer, but could not get the thought of her sometimes-boyfriend out of my head and, coupled with my new title. I finished my tea, thanked her, and suggested we could meet at my place, next time. I imagine I called her once or twice after that, but, ah well — so much for subway romance.

Of course, genealogically speaking, she was right: my middle name, Hoyer, from my paternal grandmother, is said to be German; my surname, an evolution from “Op Den Dycke,” the name of the Dutch men and women who had arrived from Holland in the 1600’s, where they were said to have lived “Up on the Dike,” settled in Long Island, what is now Coney Island, and over the next three hundred years worked their way steadily west, at a snail’s pace, settling in Western New Jersey; by the 19th century that region, Princeton and Pennington, was rife with Updikes, and my grandfather, my father’s father, was born in Trenton, on the 53th day of the 20th century: 2/22/00. I have it on good report that there is an Updike Road in, or near, Pennington.

My mother’s maiden name is also Pennington, her mother’s was Daniels, and before them there were Greenes in Rhode Island, and Entwistles, and a French branch, somewhere — all Northern European types. One of my mother’s grandfathers was an Indiana Quaker farmer, and his son, my mother’s father, was a Unitarian minister in churches in Braintree, and Cambridge, Mass., and Chicago. Her mother’s father was a captain in a Coast Guard, on the cutter called The Badger, and before him was a tribe of New Englander merchants and farmers stretching back a couple centuries. The first Greene had emigrated from England to Warwick, Rhode Island, in the mid 1600’s. My mother had shown me a genealogical chart of “Greene’s descent” that showed we “descended” from the royalty of France, and even a Russian named “Rorick the Great.” But that was nearly one thousand years ago, before the first Greene made it to America in the 1600’s.

Genealogy — thanks in part to genetic testing of companies like Ancestry.com, National Geographic and the PBS series “Finding Your Roots” — has become quite popular recently. For a fairly modest cost they will study your saliva, compare it to thousands of other samples, uncover your genotype and tell you where you are really from. The host of “Finding Your Roots,” Professor Henry Louis Gates, made the news, recently, when it was revealed that Gates had acquiesced with Ben Affleck’s request to exclude from the program the discovery that Affleck had a slave owning ancestor: odd that Affleck, a lefty from Cambridge (as am I) would want to hide this inconvenient truth, and that Gates, academic showman and great revealer of inglorious American past, would agree to exclude it. (Of course, the essential premise of the show is “genealogy of the stars,” so it is quite natural that Gates would like to stay on Affleck’s good side.)

Nonetheless, after being on some sort of Public Television “time out,” Gates was back on the air, this year, in his fine suits and shiny ties, with a whole new lineup of celebrities, most recently Dustin Hoffman and Mia Farrow. His guests often end the show in tears: “Sorry, sorry — I told myself I wouldn’t do this …” they say, daubing their eyes at some astonishing fact Gates has unearthed. “It’s okay, brother,” Gates comforts them; they shower him with gratitude, he nods in acceptance and promises to be back next week with a whole new episode and three new celebrities, whose secrets he shall reveal.

Having no claim to stardom, I don’t expect to be invited on soon, and so began to wonder about my own, Northern European roots and wondered if, indeed, that’s all there was. And as with most liberal types, I harbor a secret “wanna be” desire to be something more, or other, than I appear — a white, late-middle-aged male, putting me in the same phylum as Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell — not the sexiest demographic in the world. From ninth grade biology, I vaguely remembered the difference between “genotype” — your genetic code and sequence — and your “phenotype,” essentially, what you look like, and appear to be.

My grandmother had a branch of aunts and cousins with dark hair and eyes and olive colored skin, and she entertained the fanciful notion there was, in her family, some “Arab” blood. And after three hundred years on this continent it seems possible that there had been some “mixing,” most likely of the non-consensual variety, with people of Native American or Asian or African descent. As the Updike Genealogy reports, while describing the migrations of one Johannes Opdycke in the late 1600’s from Long Island to New Jersey, “… their herds of stock in the rear doubtless driven by a negro slave or two, who formed part of the establishment of every prosperous planter in those days.” I read somewhere that 10 percent of white Americans have some percentage of ‘African’ blood, and so it seems plausible that I could be one of them. After all, I love hot climates, prefer African and Caribbean music to their Anglo counterparts and married a woman from Kenya. Perhaps it’s all there, in my genes!

And so when I saw on the computer that you could take the test, for only 99 dollars and a sample of saliva, and within weeks have breakdown of where my ancestors came from, I ordered it online, and within days it arrived. The kit is neat and tidy: a small, white little box, containing an even smaller box, which in turn contains a glass tube to spit into, an eight step diagram of how to get your spit in the vial, the vial on the box, which is then mailed off to somewhere in Utah. I followed the directions with great care and anticipation, drooled into the vial to the exact height indicated, sealed it, and mailed it off to the lab.

Dutifully, they e-mailed me when the box had arrived, and then, a few weeks later, they e-mailed me again to say my DNA was under study, being compared to thousands and thousands of genetic markers, and it would only be a few more weeks! They invited me to get back on their website, so I could know exactly what they were up to, and I examined an enticing map of Europe with overlapping circles of ethnically certified DNA groups, stretching all the way from Eastern Europe into North Africa. Perhaps that “Arab” blood of my grandmother was actually the Moorish blood of that great empire that ruled, built, and educated, large swaths of Spain and Portugal and France for 500 years?

It was with no little excitement that I arrived home one day to find in my inbox the exciting news that my DNA results had arrived: I couldn’t wait, remembered my password for once, and followed the prompts to the results.

There it was, a simple map of Europe, a large circle surrounding Great Britain that included England and Scotland and Wales, excluded Ireland, then looped across the channel to claim Holland, the eastern edge of Germany, and north to Denmark, maybe a bit Sweden.

Below there were only two numbers, as stark as could be:

99%: Great Britain; 1% Scandinavian.

What?! I stared at the map and fiddled with the computer, looking for a more refined, or subtle, breakdown of my mysterious past, but there was none. That was it. Where were the French, the Russians, the tinge of “Arab blood”? What happened to Spain and the Moorish Empire, the tawny Kramer cousins from Pennsylvania, three hundred years of possible intermingling here in America?

Diversity? Well, now at least I know where I got my temper, my aversion to rowing, and hyper-competitiveness in the tennis court: 1% Viking. Ninety nine dollars: one dollar for every percent that I was “British”!

I didn’t tell my wife for days, and kept my secret from my students, too. I thought fondly back to my original genetic analyst back in Brooklyn, my lovely, long-limbed hostess with her sleepy demeanor and old-school gym shorts: over a cup of tepid tea, she had taken the full measure of my phenotype — freckles, thrift store clothes, self-cut hair, a general aura of waspy befuddlement — and for only the price of a New York City Subway token, delivered her verdict: “White Bread.”

You’re not alone in feeling alone: Why it’s so hard for adults to make friends

(Credit: Jan Faukner via Shutterstock)

Practically every light-hearted comedy or TV sitcom makes me feel like I should be drinking wine every night with my best friend while one of us tries on clothes from a massive walk-in closet. Not only should we share the same dress size, but we should also have a long, rich history of togetherness and sworn secrets. Clearly, this is not reality.

I realize I’m going out on a limb here when I admit this: I only have 598 friends. OK, but if I’m honest, 99.3 percent of those friends online range somewhere from stranger-danger-people-I’ve-met-once to convivial acquaintances to people I truly enjoy but who live too far away to see regularly.

That leaves 4.2 legitimate people in my life with whom I share a mutual trust. That is to say, 4.2 people that I can call out of the blue and not feel like I’m absolutely imposing on their time. (The 0.2 percent, I’ve decided, are my houseplants. I can tell them anything.) I’ll further admit that figure includes my mother, and my problem is that none of those close trusted relationships are in my same city.

I’ve noticed this theme making its way into plotlines in mainstream entertainment lately. Michaela Watkins’ character on Hulu’s “Casual” discovers her ex-husband “won” all of their friends in the divorce. Maria Bamford’s Netflix show “Lady Dynamite” devoted an entire episode to her realization, “My contact list is nothing but broken relationships!” “This American Life” aired an episode, “The Perils of Intimacy,” in May, where host Ira Glass opens, “OK, fellow adults, when did you last make a friend? Like an actual friend you see regularly, you talk about actual personal things? It’s hard, right? To make a new one?”

If you’re feeling the same way, take comfort; you’re ironically not alone. I spoke with a dozen people between the ages of 27 and 90 throughout the United States and was astounded to learn that they all felt similarly: it’s difficult as hell to make true friendships as an adult. “Over the years, I seem to have collected a Rolodex of acquaintances, but no one I particularly trust,” one responded. A post-graduate lamented, “Since college I’ve lost most of my close friends to job relocations, marriages, and surely soon enough children.” And a guy in his late 30s replied, “Working from home has its perks, but it’s isolating. No beers after work with office people, so my social life is mostly my family.”

Most of us find our “people” in school, but over time lives change: marriage, kids, divorce, work friendships that fizzle when the job is no longer the commonality. We outgrow our relationships and they outgrow us. People drift, literally and figuratively.

You know the old saying that a good friend will help you move, but a true friend will help you move a body? First of all, are you a grown-up? Hire a moving company. No amount of pizza and beer as payment is worth schlepping your crap. And if you need to move a body, well, that’s out of my jurisdiction (but again, maybe smart to hire someone? I’ll Google that). Right. I’m looking for something in between.

So when platonic relationships come to an end how do you find anew?

A woman in my apartment building, who I had seen around over the years, approached me one day and introduced herself. She bravely stated, “You seem cool [keep talkin’, lady], do you want to hang out with me sometime? I’m looking for new friends.” I nearly dropped my bag of groceries at her social gutsiness. And now we get together for coffee a few times a year, gossip about the neighbors, and take in the mail when one of us goes on vacation. But a few times a year isn’t enough for me.

So, what counts as a true friendship as you get older? For me, it’s feeling comfortable enough to be myself. And if you’re like me, it’s also trust. Not just keeping the odd secret, but trusting that my life choices aren’t your conversational fodder elsewhere (see: Salon article on seeking new friends).

Proximity also has a great deal to do with sustaining friendships. I live in New York, a city where many drop in for a few years before beginning their real life elsewhere. Having lived here since college, I’ve rotated through dozens of friends who stay a while, but inevitably move on to greener pastures: Los Angeles; Minneapolis; Huntsville; St. Louis; Dallas; Austin (times three); Toronto; Melbourne; and Queens. Yes, Queens! Ninety minutes traveling on the subway to visit for teatime does not an easy get-together make.

Of course, you come across people in life where you have the good fortune of picking up right where you left off. Five days or five years, you can reconnect as though no time has passed. That’s awesome, and I do have that special bond with a couple of people, but no one in my area code.

Certainly, what constitutes true friendship is quality over quantity, but how do you find your true “people” when you’re older than 12? And why the hell isn’t there an app for this? There are dozens of dating apps to exchange bodily fluids with perfect strangers (for free!), so why can’t there be an app to seek platonic relationships? For example: I like dinosaurs, however I would do poorly in a room filled with paleontologists. Surely an algorithm could use location services to drop a pin on someone within a five-mile radius who is also into dinosaurs but not in a Ross Geller kind of way.

There are apps like Bvddy, “connecting people through sports,” similar to Tinder but for finding people to platonically work out with at your skill level. In theory, meeting people through sports seems like a great idea, since collecting drinking buddies isn’t necessarily sustainable. I downloaded it for a test run. It requests you select the sports you’re into, offering 58 options ranging from running to badminton to mixed martial arts. I chose yoga and billiards because I’m not a run-around-soaking-in-my-own-sweat-‘n’-chat kind of gal. That and who doesn’t secretly want to be a pool shark? A request to enable location services pops up, which states the theme here, “so you can find buddies nearby because playing alone is just sad.” My closest match lived in Paramus, New Jersey. Logistically, that’s a non-starter.

But I also worry we rely far too much on technology, almost never looking up from our phones to see the real people out in the world before us. And it’s not like it’s difficult to keep up with folks in your life. However, studies have shown that with the ubiquity of social media, people are interacting live and in person less and less. And becoming, you guessed it, more and more socially awkward makes this whole “finding new friends” thing even more difficult. I almost wonder whether it’s conscious or not; by knowing exactly what’s happening on the surface of people’s lives via social media, does getting together face to face feel less necessary? There are fewer topics to catch up on if it’s all posted on your wall. Maybe it comes down to coming out from behind your phone and saying hello to those around you? Maybe if we became a little more human again, we’d have a better chance at connecting?

The other day, I rode the subway seated next to a middle-aged woman clearly visiting from out of town. She was on her phone responding to a group text with the title “Besties” at the top. I sat there silently wondering where the hell does someone your age have friends close enough that you take the time to rename your text thread Besties?! I asked where she was visiting from without getting into my platonic relationship neurosis. “Oklahoma City!” she replied. Oklahoma City. So, that’s where people drink wine while trying on clothes in a massive walk-in closet.

Searching for a great American rock show: Why is rock ‘n’ roll on TV so hard to get right?

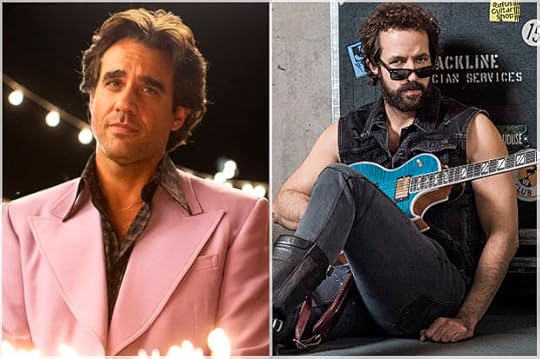

Bobby Cannavale in "Vinyl;" Peter Cambor in "Roadies" (Credit: HBO/Showtime)

Two much-awaited series about rock ’n’ roll made their debuts on prestigious cable networks this year. One has already been cancelled, after generating its share of hatred from the very people who should have loved it. Another has not quite lifted off, and may not last beyond its initial season, either. With a third series drawing mostly bad reviews, it’s enough to make you wonder: Is it even possible to make a decent television show about rock music?

One of these shows, Denis Leary’s “Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll,” didn’t arrive with enormous expectations, so it hasn’t been met with the severe disappointment of the others. But “Vinyl” was set in a period that currently generates immense fascination — New York in the pre-punk ‘70s — helmed by Martin Scorsese, Mick Jagger and Terence Winter of “Boardwalk Empire.” And “Roadies” was created by Cameron Crowe, the former music writer who directed “Almost Famous,” with executive production by Winnie Holzman, creator of “My So-Called Life.”

Two veterans of rock journalism tried to puzzle out with me why these shows didn’t work. All three of us wanted to like these series, but somehow the shows didn’t quite arrive. We disagreed, though, over whether the genre of the rock-show could be saved.

Part of the problem with “Vinyl,” which was cancelled after a single season that cost about $100 million, is that it was aimed at exactly the kind of serious rock fan that would be annoyed by how many of its details it got wrong. (Critic Caryn Rose recapped the show for Salon, focusing on the authenticity of its portrayal of the time period and the artists, and found it often came up lacking.) “My sense of ‘Vinyl’ was that it was a kind of glorious failure,” says Ira Robbins, a music critic best known as the editor of the Trouser Press guides to alternative rock music. “They made a costly, painstaking effort to recreate an era. And then having reproduced it, they laid on these sloppy anachronisms, coincidences and fictionalized history.” And the show’s creators offered brief appearances by actors playing actual musicians, to almost no effect.

“It was like wax figures — Madame Tussaud’s. The story didn’t need any of the real people.” The real parallels — Gram Parsons showing up in a visit to L.A. — were like a series of non sequiturs.

One of the biggest problems was the Nasty Bitz, a band led by Jagger’s son, which bore almost no resemblance to any band in New York at the time, Robbins says. (The other rock critics I spoke to disliked the show almost as intensely.)

Mitchell Cohen wrote about rock music in New York in the years “Vinyl” was set, and took a job in A&R a few years later. He found it “ridiculous on every level,” with a “smug, in-the-know name-dropping” even while failing to create anything like the real atmosphere of those years.

Part of rock music’s appeal is exclusivity, the sense of being inside a dangerous subculture and getting all the jokes. “Vinyl” seems to have failed to resonate with people who like music for that reason, and it somehow failed to reached the people who aspire to be part of its dark, urban demimonde.

Another side of rock is more democratic and mainstream, driven by passion for the music but in a more sincere, open-hearted way: This is what Cameron Crowe offers, in movies like “Say Anything” and “Almost Famous.” So when his “Roadies” went on air this spring on Showtime, it seemed like his warmer approach to rock music might fit our tense times better than the too-cool-for-school coke-fest of “Vinyl.”

But while there have been no announcements of the show’s cancellation, and it’s simply impossible to hate, “Roadies” has failed to generate excitement. “’Roadies’ is a completely nebulous show that exists in its own universe,” says Robbins. “And then they sprinkle in some musical references. It’s simple and obvious and predictable.”

There is some good acting in the show — Imogen Poots plays a bruised young idealist very convincingly — but also a lot of missed connections, as in what’s supposed to be romantic tension between Luke Wilson and Carla Gugino’s characters. I’ve watched all five episodes made available to the press, and keep wanting each one to be better. At some point, I fear, I’ll have to give up.

“I think it would be better if it was either smarter or dumber,” Robbins says. “They’re not telling enough about the reality, and they’re hiding behind the culture. This is so glossed-up it’s like ‘Happy Days.’ ”

Cohen likes “Roadies” a bit better, but his descriptions are the definition of faint praise. “It was nice to see a show where there wasn’t a lot at stake,” he says. “It’s mostly people doing their jobs. The big tension is whether someone can get to the computer in time to put in the new set list. I kind of like that. While ‘Vinyl’ was trying to make these grandiose statements about the power of rock.”

Part of the problem, though, is that after a few episodes of small stakes, it’s hard to keep wanting to tune in again. “This is a band on the road, and not a lot happens,” Cohen says. “‘Almost Famous’ was two hours — what is this, 10 hours?” The tension isn’t exactly building. “Are they gonna change the set list again?”

So between these two shows and Leary’s — “a lame rerun of Leary’s better hits,” the Atlantic’s David Sims judged — I’m wondering: Can anyone do this right?

Robbins thinks not. The audience for rock music ranges so widely in generation, favorite style, and level of commitment that it’s hard to get everyone on the same page, he says. There’s just not enough consensus. “How would you take that enormously fragmented audience and make something both insightful and entertaining?” he asks. “You can’t narrowcast a TV show. It’s hard for someone like Cameron Crowe to make a show that would interest a 20-year-old. You could make a show that nobody understood — with sophisticated references and in-jokes — or a show that’s not really about anything but sort of set in that world. And neither of them would be entirely satisfying to anybody.”

But Cohen disagrees. “I don’t think it’s impossible. I keep coming back to ‘Mad Men.’ It’s just about advertising.” The show’s premise doesn’t sound like a natural hit. “ ‘Really? Are they gonna do TV commercials an layouts for Esquire magazine?’” The show worked, though, because it was smartly written, acted and constructed.

But there’s something else that “Mad Men” and Aaron Sorkin shows like “The Newsroom” and “Sports Night” have in common that these rock shows don’t. “Mad Men” creator Matt Weiner didn’t love advertising, but he wanted to get something across about the role the industry played in ‘60s culture. Sorkin felt for the plight of TV journalists, but he was after character and story. Few people turned to “Mad Men” because of their passion for Madison Avenue.

Similarly, the best movies about rock music — “This is Spinal Tap,” “School of Rock” — were made by directors who cared about rock music, but there’s a sense of ironic distance alongside the love of its characters.

Loving rock music and the people who make it is, as far as I’m concerned, a virtuous stance. But it may not lead to good TV. If someone balance their ardor with their art, may he or she please stand up now. In this dreary year, we could sure use it.

The new working class: Trump can talk to disaffected white men, but they don’t make up the “working class” anymore

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

This piece originally appeared on BillMoyers.com.

Thursday night, Trump spent considerable air time speaking (more like yelling) about how America’s steel and coal workers have been ignored and sold-out for decades by both political parties. He promised to bring back those long-disappearing jobs and to put their needs front and center in his administration. As the daughter of a steel worker, I admit it was nice to finally hear someone talk about how the old industrial working class was robbed of their dignity and livelihood, with little regard for the devastation left behind.

But that working class — the blue-collar, hard-hat, mostly male archetype of the great post-war prosperity — is long gone. In its place is a new working class whose jobs are in the now massive sectors of our serving and caring economy. And so far, neither Trump nor Clinton have talked about this new working class, which is much more female and racially diverse than the one of my dad’s generation. With Trump’s racially charged and nativistic rhetoric, he’s offering red meat to a group of Americans who have every right to be angry — but not at the villains Trump has served up.

The decades-long destruction of American manufacturing profoundly changed the working class — neighborhoods, jobs and families. What had once been nearly universal, guaranteed well-paying jobs for young men fresh from high school graduation were yanked overseas with little regard for the devastation left behind.

To add insult to injury, the loss of manufacturing jobs was often heralded as a sign of progress. As the economic contribution of these former working-class heroes to our nation dwindled and the technology revolution sizzled, in many people’s minds, millions of men became zeroes. They seemed to be a dusty anachronism in a sparkling new economy.

Black men, who had fought for decades for their right to these well-paying jobs, watched them evaporate just as they were finally admitted to competitive apprenticeships and added to seniority lists. When capital fled for Mexico or China, the shuttered factories in America’s biggest cities left a giant vacuum in their wake, decimating a primary source of jobs for black men that would never be replaced.

The economic vacuum would be filled with a burgeoning underground economy in the drug trade, which was met with a militarized war on drugs rather than an economic development plan. That war continues today — the scaffolding upon which our prison industrial complex is built and the firmament upholding the police brutality and oppression in black communities that result in far too many unarmed black men being shot and killed by police.

As for the once privileged, white working-class man, the dignity and sense of self-worth that came with a union contract and the trappings of middle-class life are sorely missed and their absence bitterly resented. In the absence of real commitments from either political party to promote high-quality job creation for workers without college degrees, conservative talk-radio’s echo chamber and the rhetoric of far-right conservative politicians have concocted a story about who is winning (and taking from government) in this post-industrial economy: African-Americans and immigrants.

These are the contours shaping our nation’s political debate.

Trump has hitched his presidential wagon to the pain of the white working class, though far more rhetorically than substantively. With his anti-immigrant pledge to “build a wall” and his unicorn promises to rip up trade agreements and bring manufacturing jobs back to our shores, Trump promises to make the white working class “winners” again.

But the sad reality is that his campaign represents nothing more than yet another cynical political ploy to tap the racial anxiety and economic despair felt by white working-class men. It is a salve to soothe with no real medicine for healing the underlying wound.

Trump, and the Republican Party more broadly, offers no solutions or even promises to address the grave economic insecurity of the broader working class today, whose jobs are more likely to be in fast food, retail, home health care and janitorial services than on an assembly line. Unlike their predecessors, today’s working class toils in a labor market where disrespect — in the form of low wages, erratic schedules, zero or few sick days and arbitrary discipline — is ubiquitous. Gone are the unions and workplace protections that created a blue-collar middle class — the best descriptor for my own family background. Today’s working class punch the clock in a country with the largest percentage of low-paid workers among advanced nations, with the paychecks of African-Americans and immigrants plunging even further, particularly among women.

Thanks to the brave action and demands of movements like Fight for $15, United We Dream and Black Lives Matter, the Democratic Party is finally offering a robust official platform to improve the lives of today’s working class, not the one of my father’s generation. After decades in which working-class plight went largely overlooked by the Democrats in favor of a more centrist, pro-business stance, the party’s progressive economic shift should claim broad support among the new working class. As noted in my book, “Sleeping Giant,” unlike a generation ago, today’s working class is multiracial and much more female — more than one-third of today’s working class are people of color. Nearly half (47 percent) of today’s young working class, those aged 25-34, are not white people. And two-thirds of non-college educated women are in the paid labor force, up from about half in 1980.

The Democratic Party, both through its platform and its candidate, supports higher wages, paid sick days, affordable child care, college without debt and reifying the right to a union. With a platform more progressive than any in recent history, especially on economic and racial justice issues, there should be no doubt that the Democratic Party is the champion of the working class, at least on the merits. But most people don’t read party platforms or study policy positions. Instead, they listen and watch, waiting for cues that a candidate “gets” them and is actually talking to them.

For despite the platform language and Hillary Clinton’s stated positions, the Democratic Party hasn’t been talking to the working class. The words “working class” seem all but erased from the Democratic lexicon — in its speeches, ads and on its social media. The party’s language still clings to vague notions of “working people” or “hard-working Americans” or the false notion of a ubiquitous “middle class.” It may well be that the party has bought the political spin that “working class” is code for “white and male” — but actually, it’s people of color who are much more likely to consider themselves working class. And as the party of racial and social justice, Democrats are missing a big opportunity to sell its economic platform to this new working class.

The General Social Survey, a long-running public opinion survey, found in 2014 that 46 percent of respondents identified themselves as working class compared to 42 percent who identify as middle class. Black and Latino individuals were much more likely than whites to identify as working class. Six out of 10 Latinos and 56 percent of blacks consider themselves working class, compared to just 42 percent of whites. In fact, in every year since the early 1970s, the percentage of Americans who identify as working class has ranged between 44 and 50 percent. Interestingly, younger people are also more likely to consider themselves working class, with 55 percent of 18-29 year olds identifying as working class compared to 36 percent who identify as middle class.

Yet Trump has won the rhetorical war for the working class — despite his pitch being narrowly tailored to disaffected white men. There is no doubt in my mind that the Democratic Party is the party of the working class — white, black and brown — at least substantively. But by failing to explicitly use the term “working class,” the party risks not being heard by the very voters who have the most at stake in this election.

Obsessed with “Stranger Things?” Meet the musicians behind the show’s spine-chilling synth score

Winona Ryder in "Stranger Things" (Credit: Netflix/Curtis Baker)

Netflix’s new streaming series “Stranger Things” is a fantastic voyage through ‘80s sci-fi, horror, teen romance and paranormal tropes. I gorged on all eight episodes in two days after its July 15 release, in part because the show — about the odd disappearance of a little boy and the discovery of a suspicious government lab, slimy creatures and a stoic little girl in a small Indiana town in 1983 — is riddled with cliffhangers. But it’s also a noteworthy series because twin showrunners the Duffer Brothers effortlessly disperse so many clever meta references throughout each episode. They do this narratively (with winking nods to things like “Tales from the Darkside,” “E.T.,” “Poltergeist,” “The Goonies,” “Aliens,” “Altered States” and “Under the Skin,” as well as with actors Winona Ryder, Matthew Modine and River Phoenix doppelgänger Charlie Heaton), but they also really nailed their musical references.

Watching “Stranger Things” immerses you in the sounds and the soundtracks of the ‘80s. The Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go” is a repeated theme here, and other nuggets such as New Order’s “Elegia” and Modern English’s “I Melt with You” encapsulate key scenes. But the musicians who really set the tone for “Stranger Things” are Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein of the synth band Survive. Dixon and Stein wrote the spectral theme song and the show’s spine-chilling synth score. As a result, they now have an avid social media following posting about their work.

There’s already a Reddit thread dedicated to the “Stranger Things” original soundtrack, and older posts on Survive’s Facebook page are littered with new testimonials about the show, while the Facebook page for “Stranger Things” contains raves like “You just killed it with that synth score …. it set the whole mood for the show and immediately made it clear we were watching something different” and “The synth WAS the movie [sic].” The Austin-based musicians have turned their longtime love for Tangerine Dream and John Carpenter scores into a burgeoning new soundtrack career.

As Survive, the duo has been bringing moody synth soundscapes to life since 2008. Their music already contains a bold cinematic quality, their records pulsing with droning hums and glitchy outbursts over layers of icy melodies. But they didn’t land their first Hollywood opportunity until they were approached about licensing two songs off their eponymous full-length record for the 2014 thriller “The Guest.” For “Stranger Things,” the Duffer Brothers hired Dixon and Stein to write all original music.

Dixon and Stein have been on the road since “Stranger Things” came out and the immediate fandom is throwing them for a loop. Speaking on the phone from Portland, OR, Dixon says he went camping last weekend, leaving on the same day that the show debuted. “It came out Friday and I left town Friday and was without cell phone service,” he says. “I came back to town and my cell phone had, like, melted when I got reception again. That was pretty fun, to be cut off and then get totally ransacked by everybody I know.”

I spoke with Dixon and Stein about their process for creating the perfect “Stranger Things” vibe, their upcoming record for Relapse Records and their take on the show’s dramatic ending. [Warning: Spoilers ahead.]

As soon as I heard the opening credits of “Stranger Things,” I thought, “I’m in.” The song really set the tone for the show. What do you think it is about the right soundtrack that pulls people in?

Kyle Dixon: It sets the mood. But I think for TV, the bar is set pretty low. People don’t think twice when something is cheesy because they’re so used to it. So when they hear something that’s a little more tasteful it, it stands out.

Michael Stein: When we write something we’ll call it “too TV” if it’s borderline cheesy or just generic. Almost like a marker of what not to do.

What influence have soundtracks had on your music, before you were creating them yourself?

Stein: I’m obsessed with movies. I think that [the influence of old soundtracks] just becomes intuitive because you grew up with them. It’s like the ‘80s are instilled in you.

Dixon: We listen to a lot of Tangerine Dream and they did a ton of soundtracks. There’s a few key soundtracks by them that definitely influenced us in a lot of ways, like “Thief” and “Sorcerer.”

In older sci-fi movies, the music almost becomes a character in the film — which is how I felt about the music you wrote for “Stranger Things.”

Dixon: That’s great. The Duffers made a conscious decision that they wanted the music to be a big part of [“Stranger Things”]. That’s why they brought us in so early in the process compared to most TV shows, where the music would come last. We sent our demos and got hooked up when they were doing casting.

Stein: Our early demo themes just ended up in the show. That helped define the direction we went in.

So you didn’t have anything visually to work with in the beginning?

Dixon: They did a lookbook with a synopsis of the show and characters and images from movies they were drawing references from — the tones and colors and stuff — and they also made a mock trailer with themes from other movies.

They pitched Netflix a trailer with one of our songs from our last album in it. And then they were like, why don’t we get these guys whose music we used in the trailer?

How did the Duffer Brothers find you in the first place?

Dixon: They just emailed us. We tried to figure out how they found out about us and they’re not even sure — maybe it was from “The Guest” — but they were like, “I don’t know.” So it’s a mystery.

What were some of the specific guiding points that the Duffer Brothers gave you to direct the music you wrote for the show?

Dixon: The main things they told us was there’s Eleven, the girl with the powers, and there are a few other characters, and they wanted us to do a few scenes for her. So we tried a couple of things out, did a few versions of what an Eleven theme might sound like and worked on that.

Stein: She was scared, kinda sad — they gave us guidelines about who she was.

Dixon: There’s a big scope of sci-fi. There’s people-dressed-in-crazy-outfits sci-fi, with monsters everywhere, and then there’s like “Stranger Things” sci-fi, where sure, there’s a monster, but it’s more …

Stein: Ominous.

Dixon: It’s a real-world situation most of the time. It’s like “E.T.” or something. It’s about people, and then there’s this weird thing also. One of the guidelines they gave us was that they didn’t want [the score] to be “too synth.” They came to a synthesizer band to make the score but they don’t want it to be too synth. [Laughs.] We had to figure out what that means to them. Because when you’re talking to directors they may be using words that mean something completely different in musical terms than what they are trying to convey. So there was a bit of learning we had to do there, but obviously I think it worked out.

What did you figure that not being “too synth” meant in the end?

Stein: Resonance.

Dixon: There’s a part of a synthesizer called “resonance” and it makes everything sound kinda (makes laser noises) laser-y. As long as we’re not doing too much of that, I think we’re in good shape. I think that’s what it means, but you never know.

So the music was supposed to be centered around characters like Eleven, not specific scenes?

Dixon: The Eleven scene was just one of the early prompts. That was a starting point for us. But after that the focus shifted to whatever the scene was.

Stein: There were a couple plot points or storylines where we knew we had, like, an ‘80s teen romance. Or there’s some kind of monster. So we came up with themes for all these different elements of the show that showed a broad scope from horror to romance to aliens to childlike. We had to cover a lot of ground with the pitch.

Dixon: And background texture. Stuff that people don’t even really notice but it helps set the mood. We sent them a ton of music early on, like here’s something that could [be playing] when there’s an action scene. Here’s something that could happen when somebody gets happy. This could be cool when they turn a corner. So they had a decent sized library going into it before we even had a picture. They used a lot of that [music] and we ended up writing a lot of new stuff as well.

Stein: Right at the beginning we were talking about all the sound effects we were going to make and got really overzealous. We wanted to do the entire sound design for the entire show, every ambient moment. (Laughs)

What was the most fun “Stranger Things” scenario to work on?

Dixon: The monster theme was fun. The Eleven theme was good. I couldn’t pick one.

Stein: A lot of the more direct stuff that relates to us [as a band], like the theme, came a little easier. The other stuff was more challenging. It’s not like the stuff we write all the time. Like, a kid’s theme?

Dixon: It was pretty fun to do that stuff because we wouldn’t typically write something that’s that overtly happy or childish as Survive.

How did you make sure your soundtrack really matched the era of the show? Did you only use instruments that dated from the early ‘80s?

Stein: Not on purpose.

Dixon: We’ve always used a lot of older equipment and we absolutely did that on this show, but there’s also lot of new equipment in the music as well. We used a Prophet Six quite a bit, which is a brand new synth but it’s modeled after an older synth.

Stein: The Prophet adds a sound that was in so many movies, from Tangerine Dream’s [soundtracks] to John Carpenter’s.

Dixon: It’s all over everything, so it definitely references that [‘80s] era just because it was so popular. That is a great sounding keyboard. We use a Prophet Six but the original one was a Prophet 5.

“Stranger Things” drops a lot of visual Easter eggs in the show — posters for “Evil Dead” and Tom Cruise movies, a Trapper Keeper, D&D jokes — that feel like little in-jokes. I’m curious if in your music, were you dropping Easter eggs for the music nerds to get excited about?

Dixon: They’re going to get excited anyway. People are already speculating about what we were using to get our sound and they’re all varying degrees of correctness because we have quite a bit of gear between the two of us. I couldn’t say we intentionally dropped any Easter eggs but there are definitely some very unique and recognizable sounds from synthesizers in the show.

Stein: I’d maybe write something and laugh to myself about it, about how it sounds like something else. But I think it’s so off that no one would get it. I’m the only one who would think it was funny, like a little melody.

What are people nerding out about the most?

Dixon: We’ve gotten a ton of emails and messages like, are you using this? Are you using this? [Laughs.]

Stein: I saw a message 20 minutes ago that was like, these guys definitely don’t use any vintage equipment, it’s all modern — just dissing on all the old stuff. And I wanted to comment and be like, actually, it’s 90 percent hardware and that “old crappy stuff” you’re making fun of.

Dixon: It’s funny to see the message boards light up with speculation about how we did certain things.

So after I started watching “Stranger Things,” I went straight to iTunes and bought a few of your records. There’s “LLR002,” and “Hd009,” and then your new full-length for Relapse Records that comes out in September is “RR7349”…

Dixon: The names of the records are just the catalog numbers for the record label. We’ve never really named a release.

I thought there was some secret code happening in there.

Dixon: We’re just going to keep doing it. We already have six releases that don’t have names, they’re just random letters and numbers.

What was the concept behind the music in “RR7349?”

Dixon: Our first LP is half songs and drone, and half textural moody stuff. And with this one we wanted to make more substantial songs. We were also trying make it sound ‘70s at times. There’s something between classic rock and prog that we’re trying to do … Slow cosmic songs, I guess? I don’t even know what to call it.

Were there pieces of the “Stranger Things” songs that made their way into this record?

Dixon: No. It’s still us making the music, so I guess it’s going to sound similar, but nothing from the record is in the show.

The record has a strong dystopian vibe. Maybe I was influenced a little by titles like “High Rise,” which was an awesome J.G. Ballard book.

Stein: There’s definitely more horror on there this time. I don’t even know if I’ve seen “Leaving Las Vegas,” but I have an idea of what “Leaving Las Vegas” is like: a dark, luxurious, sad movie that takes place in a fancy place. I could be completely wrong. But it’s the theme of being in a really nice place in a fucked up situation and dealing with that in the lap of luxury …

Stein: … and an ominous magic floating around.

Dixon: Something weird. That was an idea we kept floating back to.

It sounds like even when you’re not making a soundtrack, you still have a visual narrative in your head when you’re making your records.

Dixon: Definitely, we always refer to [visuals]. Like if there’s a certain part of the song where, like this is where the fucking helicopter crashes into the side of the mountain. Or this is when the dude gets drunk and goes blurry and falls down the stairs. This is where they murder the guy in the window.

Stein: This is where the guy’s chest splits open and a giant beam of light hits the sky.

Dixon: And this is the sound of the ax that’s chopping …

Stein: We’ll come up with a story as we’re writing it and we’ll play off our ideas as we’re telling the story and start thinking that’s what the song is.

Dixon: Like we’ll call something “the hammer.” And we need to make the hammer louder right here, and that’s where it’ll break. We’ll kind of name stuff if it fits into the story and that’s how we know what part of the song we’re talking about.

Will you be releasing the music from “Stranger Things” too? I see people already asking for it on social media.

Dixon: If people want it, we’d like to release it, but ultimately it’s up to Netflix if they want to release it. We don’t have any answer on that yet. But I wouldn’t be surprised if it happened. It seems like there’s a strong enough response to warrant doing that, but we’ll see.

Has “Stranger Things” opened new doors for soundtrack work?

Dixon: We don’t have any plans to work on anything else but we have a lot of emails that need to be responded to. I think it’ll lead to more stuff but nothing solid yet.

Since you were involved in “Stranger Things,” I have to ask your opinions on some of the unresolved endings in the show. What do you think happened to Eleven? Do you think Hopper knows where she is? And what’s happening with Will? Is he the flea that can walk between the regular world and the Upside Down?

Dixon: I have no idea, but it certainly looks like Will has a monster or something inside him.

Stein: I’m just hoping we get to find out.

Tommy Stinson is the most positive man in rock ‘n roll: “All of the bad thoughts died with my brother”

Tommy Stinson (Credit: Steven Cohen)

With over three decades under his belt in the rock and roll business, one might expect Tommy Stinson of The Replacements and Guns N’ Roses fame to be bored by just about anything that comes his way. That’s not the case, though.

In conversation, Stinson seems as excited as ever to hit the pavement (albeit not behind the wheel himself — he doesn’t drive) and perform in front of an audience no matter the size.

This summer, Stinson will embark on a solo tour of sorts, crashing houses, record stores and sundry small venues to preview songs from his forthcoming album as well as others from his extensive back catalog. Billed as “Cowboys in the Campfire,” Stinson will be joined by Chip Roberts (a contributor on guitar to Stinson’s “One Man Mutiny” solo offering) on his Southern Dandies Tour.

Stinson may be relatively mum on details about his forthcoming record, which is due out later this year, but he had plenty to chat about regarding the recent Guns N’ Roses reunion, his relationship with Paul Westerberg of The Replacements and how the current state of the music industry is impacting his work ethic.

You’re about to go on a tour where you’ll be hitting small venues and performing at house shows. What’s attractive about that kind of touring?

You know, there are so many different angles on what I do that I like at different points. I like recording a whole lot, but that gets boring. I like playing with a band, but that gets loud and hard and tiresome. Everything has its pros and cons about it that I do.

My kid is out of school. I wanted to go out and have an adventure and that’s what we’re doing. It’ll be called “Cowboys in the Campfire.”

You were active with Bash & Pop immediately following the breakup of The Replacements and before you joined Guns N’ Roses. With a new record on the way, how do you file these songs among the other records you’ve made in your career?

You know, they’re exclusively, completely fucking different. What I’m doing in the summer, I’m going out there and having fun with my friends. Just doing what I feel like doing. I hope people go out and have a great time.

I made a new record, a band record, which I am very stoked about. The band record that I tried to make with Bash & Pop years ago ended up being Steve Foley and I for the most part. It was kind of a band record with friends of mine coming over and filling it out.

This record, I recorded everything completely live over in my own studio. I have one whole room in my house that is just a studio. It’s two rooms, really. One’s a control room; one’s a live room. We put up a couple of microphones and let it all flow.

I’ve always liked the band thing — the camaraderie, the team vibe. It’s always been a huge thing to me. I wanted it live. I wanted it to feel good and sound like it was a bunch of people hacking it out together and getting that rock and roll thing.

The other band you were in for almost two decades, Guns N’ Roses, is currently on tour. You’re not with them anymore, but you were in that band as long, if not longer, than you were with The Replacements. It seems like The Replacements have faded out since the reunion, but Guns N’ Roses are now fading in. Do you have any thoughts on the Guns N’ Roses reunion?

[laughs] I’m actually going to see them again tomorrow! I just went and saw them with a buddy of mine. I think, for all practical purposes, he wanted to go and wanted a comrade to go with. And I told him, “You know what? Let’s go.” He got me a ticket and we had a fantastic time.

All of those people are my friends — the band guys, the crew guys. The only one I don’t know is Slash. I don’t think I’ve ever really met him. But I’m friends with all of them — Axl included. Even Izzy!

So, I’m going to see them in Philadelphia with some friends because I had such a good time. It was fantastic. It was great to see it on the other side and not having to be in it. And I mean that as no disrespect. But, when you’re in it — when you’re in the cacophony with the ear monitors — you can’t really appreciate what the fans see on the other side.

I want to watch it as a show and hang out with the people and go, “Fuck! This is goddamn fun.”

It’s been fun for me. I’m not an ambassador of goodwill because I need to be. They’re my friends and I’m glad for them. They’re having fun, so I’m going to go see them and say “Hi” to my buddies.

I saw you with Guns N’ Roses a few years ago and it was really great. I have to admit that I was skeptical, but I had a really great time and was happy to see you on stage with them. It exceeded my expectations.

Thank you for that. It was a great gig for me. I was in that band almost seventeen years. It was fun for me. It was good for me. I’m just happy they’re all out there. They had the same stigma that The Replacements went through, but they’re doing great. It’s not all the band members, but people should love it. If you’re a fan, you’re going to love it.

How often do you speak with Paul Westerberg and are you two working on anything together? There was some talk of another Replacements record before the reunion ended.

You know, we exchange texts now that he’s actually got a cell phone. We exchange goofy pictures and texts about once a month. We never lost touch. We never went years without talking to one another. We always talked and had that sort of thing. It’s like your brother that you have a lot of history with — good and bad.

He’s a little bit older than me. There are certain witticisms that I reach out to him for. We did our thing. As far as anything together, we’ll probably play something together again. We never said we wouldn’t.

As for anything in the works? Not a thing.

You don’t drive. Does that make touring feel that much more youthful for you?

Paul doesn’t, either! Ultimately, someone’s got to navigate and be able to read a fuckin’ map! Why would I learn how to drive? Someone’s got to know how to read a map and be the passenger. I like that role. I would often ride with the equipment trucks because I liked to do that.

I never felt the need to do it. I grew up in Minneapolis and traveled all over the place. I was always comfortable with public transportation. I lived in L.A. for twenty years. I’m the only guy that I know that was completely punctual to every meeting by taking public transportation.

I run my life like that. I’m not completely anal about time. But if I have a 3 o’clock meeting and I’ve got to take a bus or train to get there, I’d rather be on the early rather than late side.

Because of the nature of touring in a band together, do you ever get tired of being asked about your brother, Bob, and re-living that familial element of the band?

No. I miss my brother a lot. When my brother died, the one thing that happened to me and for me, I suppose, was that there were a lot of good, bad and ugly things that we grew up with — even before The Replacements were put together — there were all of these thought-bubbles and memories of shit. When he died — what I was left with — I just have the good thoughts. All of the bad thoughts died with my brother. So, I’m left with these beautiful and colorful experiences that we had together. We lived in Florida when I was five or six years old, but they’re not full memories because I was so young and I’m old now. But they’re colorful and positive thoughts. All of the bad stuff that happened during The Replacements, all of that stuff went away.

I have dreams about cool things. I don’t have nightmares about my brother dying or anything weird. I had those when he was still here.

These days, you’re being asked to play on a lot of records and produce for other artists that cite the bands you’ve played in as inspirations. Is that flattering for you?

You know what? I am. I’ll be honest with you. I’d like a whole lot more bands to get down with reaching out — whether they want me to produce a song or whatever. At the end of the day, all of my old, staunchy ’80s music friends or A&R guys are complaining about how the internet is killing everything. I’m not on that kick. I think there are options. I think the world is still our oyster.

If I’m going to write a song, I still want that feeling like, “This is the best song I’ve ever written” and then I throw it out there. I wouldn’t bother if I didn’t do that. It’s not like I go to work and say, “Well, I’ve got a mediocre song. I might as well put it out there.” Every song I put out there, I look at it like it’s great — whether it is or not.

I would like more bands, if they felt like I could bring something to them and their sound or whatever — whether I play kazoo or I produce their band — to reach out.

I love the fucking process of this. I love playing live. I love recording. I love being on both sides of the mixing console.

The recording industry may be in shambles, but you can still get in a van have the time of their life.

Fuck yeah! Hell — fucking — yeah. And that’s the reason why we do it. You can’t get in any vessel and go play a set show and half-ass it. Are there 20 people? Or are there 20,000 or 50,000 people? Doesn’t matter. You’re just driven to do it. I may just sit in a cornfield and do it for a bunch of stalks of corn, but I have an inner drive that has nothing to do with who is going to be there. I just go and do my thing.

“Everything that Donald Trump and Mike Pence are not”: Clinton and Kaine debut as Democratic ticket in Florida

Democratic U.S. vice presidential candidate Senator Tim Kaine (D-VA) waves with his presidential running-mate Hillary Clinton after she introduced him during a campaign rally in Miami (Credit: Reuters)

Hillary Clinton introduced running mate Tim Kaine as “a progressive who likes to get things done,” joining the Virginia senator in the crucial battleground state of Florida to help kick off next week’s Democratic National Convention.

Clinton said Kaine cares more about making a difference than making headlines, “everything that Donald Trump and Mike Pence are not.”

Clinton offered Kaine the vice presidential spot on the Democratic ticket in a phone call on Friday night. His selection completes the line-up for the general election. Clinton and Kaine will face Republican Trump and his running mate, Pence, the Indiana governor.

Kaine, 58, was long viewed as a likely choice, a former governor of politically important Virginia and mayor of Richmond who also served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

He also had a particularly powerful backer: President Barack Obama, who advised Clinton’s campaign during the selection process that Kaine would be a strong choice.

Kaine is a fluent Spanish speaker with a reputation for working with Republicans.

“Trying to count the ways I hate @timkaine,” Arizona Republican Sen. Jeff Flake wrote on Twitter. “Drawing a blank. Congrats to a good man and a good friend.”

Kaine was the choice over Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, a longtime friend of the candidate and former President Bill Clinton.

The senator is viewed skeptically by some liberals in the Democratic Party, who dislike his support of free trade and Wall Street. Shortly after Friday’s announcement, Stephanie Taylor of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee said Kaine’s support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact gives Republicans “a new opening to attack Democrats on this economic populist issue.”

Notably, a campaign aide said Kaine made clear “in the course of discussions” that he shares Clinton’s opposition to TPP in its current form.

Clinton’s campaign teased the announcement throughout Friday, encouraging supporters to sign up for a text message alert to get the news – a favorite campaign method for getting contact information about voters.

The Democratic candidate made no mention of her impending pick during a somber meeting with community leaders and family members affected by the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando and a later campaign rally in Tampa.

When the news came via text, she quickly followed it with a message on Twitter: “I’m thrilled to announce my running mate, @TimKaine, a man who’s devoted his life to fighting for others.”

Trump also announced the choice of his running mate on Twitter, and followed it up with an announcement the next day at a hotel in midtown Manhattan – a curious choice given the state’s strong Democratic leanings.

Clinton and Kaine appeared at Florida International University in Miami. Florida is the nation’s premier battleground state, and the bilingual Kaine is likely to be a valuable asset in Spanish-language media as the campaign appeals to Hispanic Americans turned off by Trump’s harsh rhetoric about immigrants.

Before entering politics, Kaine was an attorney who specialized in civil rights and fair housing. He learned Spanish during a mission trip to Honduras while in law school. During his political career, he’s demonstrated an ability to woo voters across party lines, winning his 2006 gubernatorial race with support in both Democratic and traditionally Republican strongholds.

His wife, Anne Holton, is the daughter of a former Virginia governor and is herself a former state judge and the state’s education secretary. The couple has three children.

Trump, in a text to his own supporters, said Obama, Clinton and Kaine were “the ultimate insiders” and implored voters to not “let Obama have a 3rd term.”

Kaine got some practice challenging Trump’s message when he campaigned with Clinton last week in northern Virginia, where he spoke briefly in Spanish and offered a strident assault on Trump’s White House credentials.

“Do you want a ‘you’re fired’ president or a ‘you’re hired’ president?” Kaine asked in Annandale, Virginia, as Clinton nodded. “Do you want a trash-talking president or a bridge-building president?”

—-

Munich shooting linked to neo-Nazi mass murderer Anders Breivik

Police near the shopping center where a mass shooting took place in Munich, Germany on Friday, July 22, 2016 (Credit: AP/Matthias Balk)

A German gunman likely influenced by right-wing extremists killed nine people and injured 27 more in a mass shooting on Friday.

German police said the shooter was “obsessed” with mass shootings.

Authorities also said the shooting was connected to neo-Nazi Anders Breivik.

Munich police chief Hubertus Andrae said the link between Breivik and the Munich shooting is “obvious,” the BBC reported.

The Munich shooting took place on the fifth anniversary of the massacre Breivik carried out in Norway, in which he murdered 77 civilians, the vast majority of whom were leftists at a political activism camp.

Moreover, the shooter used a photo of Breivik as the profile picture on his phone’s WhatsApp messaging service.