Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 701

August 2, 2016

Virgin Galactic is one step closer to making space tourism a reality

Virgin Galactic's WhiteKnightTwo carrier aircraft mothership, in Mojave, California, November 4, 2014. (Credit: Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

When Virgin Galactic’s first SpaceShipTwo was destroyed in October of 2014, it was unclear when — if ever — the company would receive permission from the Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA-CST) to begin testing another.

A little under two years later, the FAA-CST deemed the second SpaceShipTwo ready to be put through the vigorous paces required by the federal government. Its predecessor (dubbed the VSS Enterprise) successfully completed 55 missions before breaking up in flight and crashing due to what was eventually determined to be co-pilot error.

“The granting of our operator license is an important milestone for Virgin Galactic, as is our first taxi test for our new spaceship,” the company’s senior vice president, Mike Moses, told Fortune.

“While we still have much work ahead to fully test this spaceship in flight, I am confident that our world-class team is up to the challenge.”

Over 700 people have already booked $250,000 flights on the ship, including celebrities such as Brad Pitt, Tom Hanks, and Katy Perry, as well as scientists Stephen Hawking and Neil Degrasse Tyson.

The company, which is backed by investments from Richard Branson and the Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, anticipates that within the next decade, the number of human beings who have been in space will rise exponentially, from 550 today to somewhere in the range of 11,000 very lucky millionaires by the year 2026.

July 31, 2016

Cyberattack on America: How vulnerable to hacking is our election cyber infrastructure?

(Credit: Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Following the hack of Democratic National Committee emails and reports of a new cyberattack against the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, worries abound that foreign nations may be clandestinely involved in the 2016 American presidential campaign. Allegations swirl that Russia, under the direction of President Vladimir Putin, is secretly working to undermine the U.S. Democratic Party. The apparent logic is that a Donald Trump presidency would result in more pro-Russian policies. At the moment, the FBI is investigating, but no U.S. government agency has yet made a formal accusation.

The Republican nominee added unprecedented fuel to the fire by encouraging Russia to “find” and release Hillary Clinton’s missing emails from her time as secretary of state. Trump’s comments drew sharp rebuke from the media and politicians on all sides. Some suggested that by soliciting a foreign power to intervene in domestic politics, his musings bordered on criminality or treason. Trump backtracked, saying his comments were “sarcastic,” implying they’re not to be taken seriously.

Of course, the desire to interfere with another country’s internal political processes is nothing new. Global powers routinely monitor their adversaries and, when deemed necessary, will try to clandestinely undermine or influence foreign domestic politics to their own benefit. For example, the Soviet Union’s foreign intelligence service engaged in so-called “active measures” designed to influence Western opinion. Among other efforts, it spread conspiracy theories about government officials and fabricated documents intended to exploit the social tensions of the 1960s. Similarly, U.S. intelligence services have conducted their own secret activities against foreign political systems — perhaps most notably its repeated attempts to help overthrow pro-communist Fidel Castro in Cuba.

Although the Cold War is over, intelligence services around the world continue to monitor other countries’ domestic political situations. Today’s “influence operations” are generally subtle and strategic. Intelligence services clandestinely try to sway the “hearts and minds” of the target country’s population toward a certain political outcome.

What has changed, however, is the ability of individuals, governments, militaries and criminal or terrorist organizations to use internet-based tools — commonly called cyberweapons — not only to gather information but also to generate influence within a target group.

So what are some of the technical vulnerabilities faced by nations during political elections, and what’s really at stake when foreign powers meddle in domestic political processes?

Vulnerabilities at the electronic ballot box

The process of democratic voting requires a strong sense of trust — in the equipment, the process and the people involved.

One of the most obvious, direct ways to affect a country’s election is to interfere with the way citizens actually cast votes. As the United States (and other nations) embrace electronic voting, it must take steps to ensure the security — and more importantly, the trustworthiness — of the systems. Not doing so can endanger a nation’s domestic democratic will and create general political discord — a situation that can be exploited by an adversary for its own purposes.

As early as 1975, the U.S. government examined the idea of computerized voting, but electronic voting systems were not used until Georgia’s 2002 state elections. Other states have adopted the technology since then, although given ongoing fiscal constraints, those with aging or problematic electronic voting machines are returning to more traditional (and cheaper) paper-based ones.

New technology always comes with some glitches — even when it’s not being attacked. For example, during the 2004 general election, North Carolina’s Unilect e-voting machines “lost” 4,438 votes due to a system error.

But cybersecurity researchers focus on the kinds of problems that could be intentionally caused by bad actors. In 2006, Princeton computer science professor Ed Felten demonstrated how to install a self-propagating piece of vote-changing malware on Diebold e-voting systems in less than a minute. In 2011, technicians at the Argonne National Laboratory showed how to hack e-voting machines remotely and change voting data.

Voting officials recognize that these technologies are vulnerable. Following a 2007 study of her state’s electronic voting systems, Ohio Secretary of State Jennifer L. Brunner announced that the computer-based voting systems in use in Ohio do not meet computer industry security standards and are susceptible to breaches of security that may jeopardize the integrity of the voting process.

As the first generation of voting machines ages, even maintenance and updating become an issue. A 2015 report found that electronic voting machines in 43 of 50 U.S. states are at least 10 years old — and that state election officials are unsure where the funding will come from to replace them.

Securing the machines and their data

In many cases, electronic voting depends on a distributed network, just like the electrical grid or municipal water system. Its spread-out nature means there are many points of potential vulnerability.

First, to be secure, the hardware “internals” of each voting machine must be made tamper-proof at the point of manufacture. Each individual machine’s software must remain tamper-proof and accountable, as must the vote data stored on it. (Some machines provide voters with a paper receipt of their votes, too.) When problems are discovered, the machines must be removed from service and fixed. Virginia did just this in 2015 once numerous glaring security vulnerabilities were discovered in its system.

Once votes are collected from individual machines, the compiled results must be transmitted from polling places to higher election offices for official consolidation, tabulation and final statewide reporting. So the network connections between locations must be tamper-proof and prevent interception or modification of the in-transit tallies. Likewise, state-level vote-tabulating systems must have trustworthy software that is both accountable and resistant to unauthorized data modification. Corrupting the integrity of data anywhere during this process, either intentionally or accidentally, can lead to botched election results.

However, technical vulnerabilities with the electoral process extend far beyond the voting machines at the “edge of the network.” Voter registration and administration systems operated by state and national governments are at risk too. Hacks here could affect voter rosters and citizen databases. Failing to secure these systems and records could result in fraudulent information in the voter database that may lead to improper (or illegal) voter registrations and potentially the casting of fraudulent votes.

And of course, underlying all this is human vulnerability: Anyone involved with e-voting technologies or procedures is susceptible to coercion or human error.

How can we guard the systems?

The first line of defense in protecting electronic voting technologies and information is common sense. Applying the best practices of cybersecurity, data protection, information access and other objectively developed, responsibly implemented procedures makes it more difficult for adversaries to conduct cyber mischief. These are essential and must be practiced regularly.

Sure, it’s unlikely a single voting machine in a specific precinct in a specific polling place would be targeted by an overseas or criminal entity. But the security of each electronic voting machine is essential to ensuring not only free and fair elections but fostering citizen trust in such technologies and processes — think of the chaos around the infamous hanging chads during the contested 2000 Florida recount. Along these lines, in 2004, Nevada was the first state to mandate e-voting machines include a voter-verified paper trail to ensure public accountability for each vote cast.

Proactive examination and analysis of electronic voting machines and voter information systems are essential to ensuring free and fair elections and facilitating citizen trust in e-voting. Unfortunately, some voting machine manufacturers have invoked the controversial Digital Millennium Copyright Act to prohibit external researchers from assessing the security and trustworthiness of their systems.

However, a 2015 exception to the act authorizes security research into technologies otherwise protected by copyright laws. This means the security community can legally research, test, reverse-engineer and analyze such systems. Even more importantly, researchers now have the freedom to publish their findings without fear of being sued for copyright infringement. Their work is vital to identifying security vulnerabilities before they can be exploited in real-world elections.

Because of its benefits and conveniences, electronic voting may become the preferred mode for local and national elections. If so, officials must secure these systems and ensure they can provide trustworthy elections that support the democratic process. State-level election agencies must be given the financial resources to invest in up-to-date e-voting systems. They also must guarantee sufficient, proactive, ongoing and effective protections are in place to reduce the threat of not only operational glitches but intentional cyberattacks.

Democracies endure based not on the whims of a single ruler but the shared electoral responsibility of informed citizens who trust their government and its systems. That trust must not be broken by complacency, lack of resources or the intentional actions of a foreign power. As famed investor Warren Buffett once noted, “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.”

In cyberspace, five minutes is an eternity.

Richard Forno is a senior lecturer and Cybersecurity & Internet Researcher at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Mothering, long-distance: There are no models for women who parent from hundreds of miles away

A photo of the author with her daughter. (Credit: Jenille Boston at Nell Boss Photography)

My daughter lost her first tooth late. By the time her first tooth came out, many of her classmates already smiled a handful of grownup teeth. She followed in her mother’s footsteps. My teeth were always slow. I still have all my wisdom teeth.

Her father texted me an un-captioned and unexpected snapshot of her tooth loss that evening. Her smile was lovely and proud and excited. She had been anticipating the loss of that first tooth for many weeks. She was eager to catch up with her classmates.

I wouldn’t see the actual space in her mouth for several days yet. Last summer, one month before she started in the first grade, I moved to a city three hours away from my daughter’s elementary school. I had a new job after finally completing my doctoral program. Since then, Nuala and I have been navigating what it means to love one another from a distance.

My daughter and my dissertation came into this world at about the same time. I began reading the scholarly literature for my prospectus the summer I was pregnant. I sat with my round and growing belly in the garage, with the sun streaming through the open door, reading about sexual violence, victimization and rape laws. It was a mishmash of the best and the worst of the world. Hope and trauma, all at once.

After my daughter was born on the last day of summer, I took some time off, and then resumed reading in the winter months. Now she nursed and napped on my lap while I read and formulated my prospectus. We couldn’t work in the mornings because that was time for play. I wrote in the evenings after she slept. Throughout her babyhood and toddlerhood, she often came with me to meetings, as she attended daycare only some of the time. It was all we could afford.

There was one conference in Chicago, at the beginning of her first summer, when I was scheduled to present first thing on a Sunday morning, and she cried all night long in the hotel room. But of course we survived and drove home to Michigan that afternoon with some new baby teeth.

Her father moved out shortly after her third birthday. He loved someone else. So we were already charting a non-traditional family formation when I moved south. Nuala was already used to shuttling between two homes. She was already accustomed to seeing a broad network of grownups as her people. Luckily, her teachers were great supporters and helped to frame her situation as ordinary, no better and no worse than her classmates’.

We continued on. I collected lots of data, and she grew into a kid. By the end, she was still snuggled next to me on the couch, watching cartoons and keeping me company, as I edited all the words I had written. One rainy afternoon last spring, she asked what I was doing. I told her I was writing a thing called a dissertation. Then she asked if I had written it that afternoon. When I told her, no, it took a long time to write, she nonchalantly turned back to the television.

As I neared the end of my dissertation, I was left with a choice: Which, if any, geographic restrictions should I place on my job search? My divorce had been long and hard, and I lost a lot. I had invested nearly a decade training to become a professor. I didn’t want to also lose the career toward which I had worked so many years. But the academic job market is brutal. Most graduate students go on a national search and count themselves lucky if they receive a single tenure track offer. It turns out that I was one of the lucky ones: I accepted a faculty position just 200 miles south of home.

After weighing all the ordinary concerns of a major life transition, I decided to pursue mothering and my career. Side by side, just like from the beginning. I was proud of what I had accomplished, and I wanted to model a strong professional identity for my daughter. Ultimately, I decided it would be better for Nuala to have a whole mother who she saw less frequently, rather than a broken and bitter mother who she saw exactly 50 percent of the week.

I believe that meaningful work does that to us. It makes us whole; it stimulates us; and it makes us better at raising up the next generation. Still, the distance is hard. When she was born, I assumed that I would be the one to tuck her in bed at night for many seasons to come. I assumed that I would see her every morning. I assumed that I would be there for her first missed tooth and then carefully pack it away for safekeeping after the Tooth Fairy’s nocturnal arrival. I didn’t give these things much thought, but they were there. It’s how I imagined my life as a mother.

We imagine mothers as being in physical proximity to their children. We get so caught up in the mommy wars — cloth or plastic diapers, big career versus stay-at-home mom, free-range or helicopter parenting — that we lose sight of the more fundamental questions. What does it mean to mother a child? What are the specific actions that lead to a well-adjusted child and an emotionally-engaged relationship? How important is daily proximity?

When I tell people about the circumstances with my daughter, their reactions indicate subtly just how central physical proximity is to our understanding of what it means to be a mother. I have received surprised faces, murmurs of apology, and shaking of heads. One friend gave me an unsolicited hug, gripping me tight, and said she was so sorry for me. These reactions of sympathy and shock come from my supporters who only want the best for Nuala and me. I can only imagine the vitriol that the naysayers might spew. Certainly no one has commended me for modeling professional aspirations and independence and financial stability to my daughter.

There are seemingly no models for how to be an engaged mother from a distance. It is almost impossible to imagine an alternative to the idea that mothers should be always close to their children. This is odd because there are many circumstances in which mothers are away from their children for long stretches of time. I look to military mothers and Filipina migrants who provide caregiving and domestic work in the U.S., even as their own children are left without a physically-proximate mother at home. Somehow they make it work.

Nuala and I are charting new territory. We explore all the pizza and ice cream joints on our weekends together. We have weekly Skype story sessions. She always wants to pet the cat as he careens into view on my laptop’s camera. So we then talk about how fun it would be if we could jump through the computer and be in the same room together. Maybe some day in the future, I remind her. I drive up for as many of her school events as I can manage. And we’re planning some summer travel adventures.

I also try to remind myself that each child is a child for a finite amount of time. It is impossible to imagine that a mother would or could be with her child for every moment of her youth. Certainly, this would be a form of hovercraft parenting upon which the experts would frown. For that matter, American time-use surveys indicate that most parents, even those for whom caregiving is their primary responsibility, tend to spend very little focused and engaged time with their children in any given day. I circle back to the question of what exactly it means to be an engaged parent.

Strange, but true: Pokémon Go is a ray of hope in a bleak world

(Credit: Reuters/Jose Cabezas)

Chaos is the new norm. Though some news headlines may still be capable of eliciting shock, they will hardly surprise you anymore. It is a sign of the times when Chachi from the “Happy Days” can return from the celebrity wasteland to prime-time television as a speaker at the Republican National Convention. In Nice, a truck became a weapon of mass destruction when it plowed through a crowd for more than a mile and killed 84 people. Deliberate shootings of African Americans and police officers were seen in Minneapolis, Baton Rouge, and Dallas, yet, as Gary Younge writes, it remains “easier to obtain a semi-automatic gun than to obtain health care” in this country. In an attempt to flex his credentials as a future Secretary of Islamophobia and expose a mind bereft of constitutional knowledge, Newt Gingrich called for the testing and deportation of all Muslims who are Sharia sympathizers. Donald Trump, who has little appetite for reading or complexity, would potentially preside over such a world and make decisions of consequence. And so it is little surprise that 75 million people sought a reprieve from the madness and have chosen instead to tune out and hunt for Pokémon.

Pokémon Go is a pandemic. The game, which is available for free download on Android and iOS, is a resurrection of the Nintendo-owned Pokémon brand that became popular in the late 1990s. It is now once again ascendant. The feverishly downloaded app uses a cellphone’s GPS and camera to make creatures called Pokémon “appear” on a user’s screen in and around his or her surroundings, with the ultimate goal being to capture them. This encourages unprecedented physical exploration, for to catch them all, a player has to exhaustively wander around real-world locations in pursuit. And short of leaving the planet, players are going almost everywhere. A 19-year-old girl in Wyoming discovered a dead body in the river during her quest. Two Canadian teenagers, oblivious of their surroundings, made an illegal border crossing from Canada into the United States during their searches. The Auschwitz Memorial had to ask gamers not to play on its grounds. A Bosnian nongovernmental agency is encouraging users to be wary of landmines left over from the 1990s conflict during their pursuits. Inadvertently, players are also stumbling into health.

Quite simply, a Pokémon is so tantalizing that it compels us to do the unimaginable: exercise. Deconditioned gamers griped about soreness after being forced to walk, run, and jump during their hunts. Since the app’s launch on July 6, its effect on physical activity is best captured through fitness tracker data. Users who mentioned Pokémon Go in their trackers were found to be walking 62.5 percent more than usual. “Pokémon Go” is being entered in workout logs by users of Under Armour’s MyFitnessPal, with individuals burning between 250-300 calories per session. This melding of fitness and gaming is unprecedented and encouraging at a time when more than one-third of the United States is obese. The condition alone contributes to heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and even cancer. Though the app is unlikely to be a panacea for obesity, high blood pressure, or diabetes, it sheds the classic association of gaming with prolonged immobility and establishes a new and hopeful paradigm through its incorporation of fitness and a connection with the outdoors.

Apart from encouraging gamers to leave their homes and obtain some much needed vitamin D from the sun, Pokémon Go has also positively affected those afflicted with mental health diseases. Those grappling with anxiety and depression have noted an improvement in mood due to the app, which promotes social interaction. In addition, the hippocampus (associated with learning and memory) and reward pathways (associated with motivation and goal-orientation) of the brain, which are understimulated in depression and inevitably atrophy, are hyperstimulated during game play based on fMRI studies. The app thus becomes a neurological antidote to depression. Professor Daniel Freeman from the department of psychiatry at Oxford University notes: “It [Pokémon Go] could be used to refocus your attention away from threat by getting you immersed in engaging activity, or it could be used to present the things you fear for long enough to help your anxiety naturally decline. Combine the right psychological science and augmented reality and you’ll have a really powerful treatment tool.”

The Pokémon Go hysteria, which has even gotten the attention of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, can mean whatever we want it to mean. It can be considered a transient fad, an escape from the macabre headlines, or something more profound. In the wake of a Republican National Convention that was, as David Remnick describes, a “four-day-long Fox-fest, full of fear mongering, demagoguery, xenophobia, pandering, and raw anger,” President Barack Obama reminded us about the importance of seeing ourselves in others. In a world currently riven by class, religion, and race, Pokémon Go attempts to do just that as it unites disparate individuals and allows them to shed their toxic assumptions. In the context of our times, this may potentially be the app’s greatest contribution. And perhaps due to our insatiable desire to catch all the Pokémon, we may just stumble upon the elusive land of mutual respect, justice, and love.

“Always be a fighter”: Sharon Jones reflects on her music, her health and her new documentary

Sharon Jones in "Miss Sharon Jones"

As anyone who’s seen Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings in concert will testify, it’s impossible to resist the charisma exuded by the soul/funk/R&B troupe. That’s mainly due to frontwoman Jones, who boasts an unstoppable, gospel-inspired voice and whirling dervish stage moves. At a summer 2015 concert when Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings opened for Tedeschi Trucks Band, I saw first-hand how the audience was completely, singlehandedly won over by the sheer force of her stage presence—moving from disinterested to totally spellbound within the span of the set.

A new documentary, “Miss Sharon Jones!” (which opened in theaters in New York City July 29 and in other cities after that) certainly contains plenty of mesmerizing concert footage. But the emotional, compelling film also follows Jones’ 2013 battle with stage two pancreatic cancer—chemo treatments and their aftermath, moving in with a friend to heal, balancing getting better with musical demands—and the impending launch of the Dap-Kings’ Grammy-nominated 2014 album, “Give The People What They Want.”

The idea for the documentary was floating around for a while before Jones’ manager approached her to see if she would be interested in being featured. Since she was dealing with such serious health issues, she was hesitant at first. “When [my manager] hit me up with it, of course I was like, ‘I don’t know, man,'” Jones tells Salon. “And then, you know, I thought about my fans, the relationship I have with my fans. And I think it would be cool to let my fans see what I’m going through. Maybe I’ll inspire someone who’s battling cancer to fight. And that’s when I chose to do it.”

Thankfully, Jones’ life story was in good hands: “Miss Sharon Jones!” director Barbara Kopple won Academy Awards for her documentaries “Harlan County USA” and “American Dream,” and also directed and produced the Dixie Chicks’ “Shut Up And Sing.” In fact, Jones can’t say enough good things about Kopple and crew—from “the love and the passion they have for doing movies” to the sensitivity they showed when dealing with her health. If she didn’t want something on camera, or wasn’t feeling well on a particular day, they respected her wishes and backed off. “I wasn’t into a reality show,” Jones says. “I didn’t want to [have] a camera up in my face when I wake up early in the morning, like the camera slept with me. Nah, I didn’t want that.” She laughs.

Still, “Miss Sharon Jones!” doesn’t sugarcoat much. For example, Jones talks about the racism and discrimination she faced growing up: During one particular striking moment while she’s visiting her hometown of North Augusta, South Carolina, she points out a shop with an owner who used to sell black kids rotten candy, and also taught his parrot to greet customers with racial slurs. A few scenes involving the Dap-Kings can also be tense, as they involve discussions about tight finances and what being off the road means for the group. In another moment, Jones gets mad at the band over changing holiday dinner plans. “What I wanted was to be with them that Thanksgiving,” she explains. “I wasn’t with my family; they were the only family I was with at the time.”

Jones admits she might have left this interaction out of the documentary had she seen it in advance, even though it concludes with them making up. “If you’ve been around me over the last 20 years, you know when I get angry, those things fly out of my mouth,” she says. “You wouldn’t see it anywhere else, but get me angry….” Jones dissolves into laughter, something that happens frequently in conversation. (That humor also crops up in “Miss Sharon Jones!”: At one point, Jones sees a motorist pulled over by police and cracks herself up by singing and modifying the Dap-Kings’ “Slow Down, Love” to fit the situation.)

These rougher edges ensure that while “Miss Sharon Jones!” is overall optimistic and positive, it’s also realistic. In fact, the documentary is so compelling because Jones confronts her health and residual grief with unsparing vulnerability. A scene where she gets her hair cut and then head shaved in preparation for chemotherapy is particularly moving, as the gravity of the situation hits her while the cameras are rolling. At another point, Jones gets deeply emotional and teary-eyed because her mother (who passed of cancer in 2013) wasn’t there to see her success.

“They caught me through a lot of pain,” she says. “The first time I saw [the documentary] was actually the first showing in Canada [at the Toronto International Film Festival]. To see how they captured that sadness… Every time I see it, I cry still to this day. I’ve seen it three times now, and I still cry. They really caught it. All of those hours of filming me, so much stuff they had—how they were able to break down and use enough film to show that part of my life in an hour and a half, was amazing. You see the love they put into that documentary and capturing me.”

In the end, “Miss Sharon Jones!” is all about the little moments of triumph in a longer, tough journey—those incremental steps forward to wellness, and the joy these smaller gestures bring. One of the most incredible scenes in the documentary depicts when she returns to church after a few months away. After briefly speaking in front of the congregation, Jones starts singing the gospel hymn “His Eyes Are On The Sparrow.” As the performance progresses, her delivery and voice grows stronger—more powerful, animated and overcome by the spirit. As attendees cheer, clap and encourage her, Jones finishes the song and starts dancing in the aisles and near the front of the church for a full minute.

Jones says this scene showed one of her first times singing since a major June 2013 operation called the Whipple procedure that entails removal of her gallbladder, part of her small intestine and head of the pancreas; in fact, she had just started walking again. “In order for me to shout, that was a whole miracle,” she says. “That was part of my energy coming back. That was part of me seeing, ‘All right. I got it. I got a little bit of it back.’ And it wasn’t me doing that as a show—I was really anointed and taken over. Those are a spiritual thing in church. For them to capture that…That wasn’t nothing they could say, ‘Could you do that over in a different position?’ That happened right there. That was natural.”

Accordingly, when people watch “Miss Sharon Jones!” there are a few things in particular she hopes people take from it. “Always be a fighter,” Jones says. “Follow your dreams. Just follow your heart. Because if you have something, a gift—don’t let anybody deter you and take it away. Because if you go on out and continue to do the right thing and just stay positive and have a good aura…I mean, really, that’s so important. You inspired people; people will feel that. Just keep on growing and be an inspiration.

“And I hope from that film someone who’s struggling, battling cancer can see a different light,” she continues. “You just enjoy the little time that you have if you think it’s a little time. And I have plenty more time, but I’m enjoying what I have, and that’s why I want to continue to get out here and perform.”

Jones and the Dap-Kings are currently out on the road, including dates opening for Hall & Oates. She’s also once again battling cancer and dealing with trying to find the right combination of chemo medicine to keep her balanced. “Medicine is supposed to be there to help me, not bring me down,” she says. “So some of the chemo medicine I’m taking now, I told the doctor, ‘I can’t take this chemo anymore,’ because it’s tearing me down. It’s getting to my legs, coming up my legs, my feet. … And the medication, if it got me all groggy and in la la land, and I can’t function, I don’t want to take that stuff. So it’s a lot I’m going through now. [But] they cut back on it, I feel a little better. And we’ll see what happens—they’ll have to find another medication, I’ll have to resort to something else. I’ll take that next step.”

Fittingly, however, she and the Dap-Kings recently released a driving song called “I’m Still Here,” which is appearing on the documentary’s official soundtrack, out August 19. The tune is a chronicle of Jones’ life, covering her early days in North Augusta, move to New York City as a child, tenure as a prison guard and, later, global travels with the Dap-Kings. But it’s also a deceptively simple statement of defiance: Despite people underestimating or discriminating against her—and despite “the big C”—the song declares she’s still fighting with all her might and moving forward.

“In my act, the reason why I have that shouting is because shouting to me is my connection to the church, is my connection to why I’m where I’m at,” she says. “I always feel that God blessed me with my gift. And being on the stage and being out here, to have so many people follow me—and knowing that out of all those thousands of people, [there are] different religions, different beliefs, people who don’t even believe in God. …But they still out there, and they listen to my story and they don’t want to shut me down. [They are] allowing me to be who I am and still be my fans. Those are true fans.

“Everything I do, my strength—why I keep going—is because of my fans. And because of my love for the music and the gift that God has given me. That movie caught all of that—I saw all of that in that little hour-and-a-half movie. I didn’t even know if I had a story that was able to go like that. That’s amazing to me.”

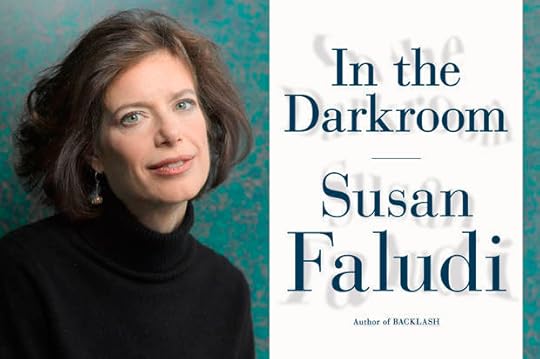

Susan Faludi on gender, feminism and her own “Transparent” story: “We’re at a moment when identity is the battlefield”

Susan Faludi (Credit: Sigrid Estrada)

In her compelling new book “In the Darkroom”, bestselling feminist writer Susan Faludi turns her critical eye from deconstructing gender myths inward, to her own life. The catalyst? Her estranged father, who, at the age of 76, sends her an email with the subject line “Changes.” Her father announces he has “had enough of impersonating a macho aggressive man that [she has] never been inside,” and is now a woman. “Love from your parent, Stefánie.”

“I devoted my life to studying gender issues, and then the question of the age—on gender—shows up in my own backyard,” Faludi said in a phone interview with Salon. “I felt that I couldn’t move forward honestly and engag[e] with questions of gender without admitting to my own experience—on some level [not doing so] would be dishonest.”

“In the Darkroom” encapsulates the approximately ten-year period that Faludi was able to get to know not just Stefánie but her father before her father’s death in 2015. In that decade of email correspondence and frequent visits in Stefánie’s native Hungary, we witness the dance between Faludi and Stefánie as they build their relationship—in the culminating pages, a literal dance, as Susan twirls her to the music of Michael Jackson at a trans party on the outskirts of Budapest. Susan, the intrepid feminist journalist who gently but persistently questions her father about his/her life—first as István Friedman, the Jewish boy growing up in Nazi-occupied Budapest, then as Steven Faludi, the violent and sometimes abusive father, and then as Stefánie Faludi, the trickster and coquettish feminine woman.

The acclaimed feminist, who has spent a lifetime fighting sexism and eviscerating gender myths, finds herself confronted by a woman who revels in gender stereotypes. “‘You write about the disadvantages of being a woman, but I’ve only found advantages,’” she tells Susan says very matter-of-factly. “‘Men have to help me. I don’t lift a finger. . . It’s one of the great advantages of being a woman.’” On another visit, Stefánie gleefully says, “It’s great being a woman… I look helpless, and everyone helps me. It’s a racket. Women get away with murder!” And, on another, she berates Susan for not having children: “This business of no children,’ she said. ‘It’s not normal…. Without children, your existence has no meaning…. Your books will stop selling. People will forget all about what you wrote.’”

Ironically, Stefánie repeatedly tells her daughter to write a book about her but is less than forthcoming with details. Information is piecemeal—not necessarily because Stefánie is ashamed of her past, but because parts of the past carry deep, traumatic wounds. Wounds born from living through the Holocaust, wounds born from the pressures of conforming to mid-century notions of American masculinity. “‘Women didn’t approve of me,’” Stefánie confesses to Susan. “‘I didn’t know how to fight and get dirty. I’m not muscular, I’m not athletic, I had a miserable life as a man.’”

Their reunion, shortly after that 2004 email, is at first extremely awkward. For Stefánie, her process of becoming a woman depended upon gender stereotypes; for Susan, her process of becoming a woman—and especially a feminist—depended upon her shattering those stereotypes. Bickering over gender essentialism betrays the book’s humor — sometimes disconcerting, sometimes dark.

The repeated bandying of the word “normal,” for example, conveys the tension between father and daughter. When Susan first visits her father, Stefánie asks her to leave her bedroom door open at night, after noticing Susan has been keeping the bedroom door shut. “Why?,” Susan inquires. “‘Because I want to be treated as a woman,’” Stefánie responds. “‘I want to be able to walk around without clothes and for you to treat it normally.’”

“‘Women don’t ‘normally’ walk around naked,’” Susan replies.

Faludi doesn’t care that her father is trans—what she does care about is her father’s unabashed appropriation of female stereotypes. “Change your clothes all you want,” she thinks when first meeting Stefánie. “You’re still the same person.” Her anger has nothing to do with her father’s change but with her concern that Stefánie is attempting to exonerate herself of being a horrible father by becoming a woman. “As I confronted, nearly four decades and nine time zones away, my father’s new self, it was hard for me to purge that image of the violent man from her new persona,” Faludi writes. “Was I supposed to believe the one had been erased by the other …? Could a new identity not only redeem but expunge its predecessor?”

“In the Darkroom” is most insightful when the narrative structure of the memoir reflects the dyadic conceptual logic of the book’s central theme: identity. Dialogue is what brings father and daughter together; dialogue reestablishes a connection. Dialogue is also what allows both Susan and Stefánie to develop more nuanced understandings of their identity markers. “As much as [the memoir] is about my father’s transgender journey, it’s not ultimately about transgenderism as it is about identity in its multiple forms, and that we’re at a moment when identity is the battlefield,” Faludi tells me in an interview.

What Faludi proves in “In The Darkroom” is that identity is the starting point, not the end point, of conversation. It is something that emerges and coheres out of dialogue, or interaction, between the self and the other. “For me,” Faludi says, “my identity seemed to take shape in resistance to what the culture was dictating my identity should be.”

“Perhaps it’s just my own perversity,” she laughs. “But others may have another similar identity formation.”

When asked if she would then define identity as a reaction formation, she pauses. “Well, I think that it’s very hard to live without categories… We all need some level of feeling tethered and belonging,” she says, noting how identity functions as way to build communities. “And yet so often, particularly modern identity seems to be about saying, OK, I’m going to put all my chips on this one identity marker, and that’s it. And now I don’t have to think about it anymore, or inspect myself anymore, or deal with any of my complicated internal psychology that is shaped, in fact, by the endless number of dynamics from one’s history to the culture you live in.”

“What was unusual about my father was that she was kind of like an identity zealot,” Faludi says. “Her life was spent up against one after another era defining identity crisis, whether it was being Jewish during the Holocaust, or trying to be the All-American suburban commuter dad during the depths of the postwar ’50s—the masculinity crisis era.” (A nod to her own study of the crisis of American masculinity, “Stiffed.”) “Or going back to Hungary, and trying to fit in again. Or being a trans woman in a country that could not be less friendly to trans people…. My father’s life was uncanny [in] how it touches on all these identity fronts that have been consuming our world for at least a century.”

“My father and I certainly disagreed with how [she] and I defined womanhood,” Faludi admits. “I’m not fan of 1950s femininity. In the end, my father, while very extreme in her notions of clichéd femininity in the beginning, came to do something more in-between and indeterminate. At the very, very end, she started referring to herself as trans rather than ‘I am a woman.’”

“In that way, and in seeing my father take that trajectory, I affirmed my own feminism, which is based on gender being fluid, and that we exist on a continuum and that there is no one way of being a woman,” Faludi adds.

“I don’t buy into any kind of essentialism or singular identity,” Faludi explains. “And in that I think I’m pretty much in agreement with contemporary trans theorists that gender is on a spectrum, and that you can’t make these judgments on an identity through the lens of one person. No one is defined by one identity.”

In many ways, “In the Darkroom” is an exemplary feminist memoir because the story crystalizes around two women who face each other, and who in turn arrive to deeper, more nuanced understandings of themselves and one another through their engagement. As the late “The Feminist Difference” author Barbara Johnson wrote, “as long as a feminist analysis polarizes the world by gender, women are still standing facing men. Standing against men, or against patriarchy, might not be structurally so different from existing for it. . . But conflicts among feminists require women to pay attention to each other, to take each other’s reality seriously, to face each other.”

“This requirement that women face each other may not have anything erotic or sexual about it, but it may have everything to do with the eradication of the misogyny that remains within feminists, and with the attempt to escape the logic of heterosexuality,” wrote Johnson. “It places difference among women rather than exclusively between the sexes.”

When I read this quote to Faludi, she immediately saw the connection. “I love thinking about that quote in the context of my relationship with my father, which went from a childhood of reacting against him as the ur-patriarch to the two of us facing each other, talking about what it means to be a woman.” She continues, reflecting upon her father’s life, “the other side of this is an extension of this idea that Johnson talks about is also seeing the ways that men are trapped by a patriarchal construction.”

This observation holds true for Faludi’s father. Shedding the stifling strictures of masculinity enabled Stefánie’s own journey of release and reunion — not only with her daughter, but with herself. “Whatever the original reason she was conscious of her having or making her gender change in the end,” Faludi observes, “what mattered to her, and what I heard her say over and over again, was that she could communicate with people now. To break out of that isolation was a serious win for her.” Stefánie’s change was her liberation.

“My father is not the poster child for trans,” states Faludi. “We need more than poster children. Trans rights should not depend on every trans person being exemplary. Stories that are individual, that are particularistic, and distinctive — like my father was — are important.”

“Where is our ‘Donald Trump’ when we need one?”: The GOP nominee, as Africans see him

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Carlos Barria)

ACCRA, GHANA — Last March, the African-American website Grio ran a tongue-in-cheek article listing the five best places for black Americans to move if Donald J. Trump won the presidency. First on the list was Ghana, which the article identified as “one of the more stable democracies” in Africa.

That’s true. But as presidential elections approach here in Ghana, where I’m teaching a study-abroad course, Americans might be surprised to find that some Ghanaians wish they had a leader like . . . . Donald Trump.

That speaks to Trump’s international appeal, which isn’t something that you hear a lot about in the United States. With opinion leaders around the world ridiculing Trump, who accepted the Republican presidential nomination last week, you might think that the only people warming to him are right-wing nationalists of the Vladimir Putin variety. But Trump remains a political inspiration to many ordinary citizens, for one simple reason: he’s not a politician.

“Where is our ‘Donald Trump’ when we need one?” Ghanaian journalist Kwaku Adu-Gyamfi recently asked, condemning both major candidates in this November’s presidential contest. Corrupt “professional politicians” had ruined Ghana, Adu-Gyamfi wrote, toeing their respective party lines even as they lined their own pockets. So it was time to look outside of the system, to someone so rich that he can say whatever he wants. Like you-know-who.

“He gets under the skin of corporate giants, politicians, lobbyists, and the media,” Adu-Gyamfi wrote, praising Trump. “Donald Trump is not afraid [to] tell the establishment what he thinks.”

Other Ghanaian supporters point to Trump’s business background, which allegedly gives him real-world experience that most politicians lack. “For Christ’s sake, this man is an American business mogul who cannot fathom why Africa still wallows in despair in the midst of abundant precious mineral resources,” one blogger here wrote in June. “He is shocked to see corrupt African leaders engineering Africa’s sufferings of epic proportions.”

Here the blogger referred to reports from last December, when several African websites claimed that Trump had threatened to “lock up” Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe and Ugandan strongman Yoweri Museveni. The story turned out to be a hoax, but even reactions to false reports speak volumes about Africans’ impatience with their poor leadership. Trump “has already pledged to deal swiftly with Africa’s dictators,” an enthusiastic Rwandan journalist wrote in April. “You can expect him to make their opponents happy.”

At the same time, though, many commentators across the continent have noted similarities between Trump and these same African leaders. “Daily Show” host Trevor Noah fired the first salvo late last year, comparing Trump’s eccentric, self-aggrandizing personality to Mugabe, deposed Libyan dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi, and South African president Jacob Zuma.

“For me, as an African, there’s just something familiar about Trump that makes me feel at home,” quipped the South-African born Noah, whose comic segment superimposed military regalia on a picture of Trump.

To other observers, however, the comparison is no laughing matter. African leaders have too frequently used propaganda and xenophobia to sway voters, as Nigerian journalist Chude Jideonwo warned in May. “Trump follows in this distressing tradition, a politician in a fact-free zone,” Jideonwo added, “telling people what they want to hear without the interruption of reality.”

And that’s precisely what so many Ghanaians see in their current presidential contest. “It’s that time again, when people go crazy, create weird slogans, promise chickens and give us nothing but false hope of a better life,” one blogger wrote last month. “Gosh I hate Politics.”

Meanwhile, the politicians are spewing hate at each other. Earlier this month, a parliamentary minister from the opposition party claimed that the woman directing the country’s electoral commission—and a member of the ruling party—got her job via “sexual favours.” And ruling party members have charged that the opposition’s presidential candidate is a charlatan in the mold of—you guessed it—Donald J. Trump.

Like Trump, one critic claimed, opposition leader Nana Akufo-Addo believes that “a falsehood repeated over and over again” will be “accepted as the truth.” And, again like Trump, Akufo-Addo is known “to demonize all of his opponents as weaklings and lightweights.”

Even as some voters here long for their own Donald Trump, then, others invoke him as a weapon to, yes, demonize their opponents. And that erodes politicians’ legitimacy still further. The less that people trust their government, the more likely they are to put their faith in demagogues like Trump.

In that sense, the Trump phenomenon really is a global one. Around the world, Ghanaian economist Lord Mawuko-Yevugah observed last month, “the political establishment” is under fire. The real question, in Ghana as well as the United States, is whether it can offer people anything better than what the Donald Trumps are promising. We’re about to find out.

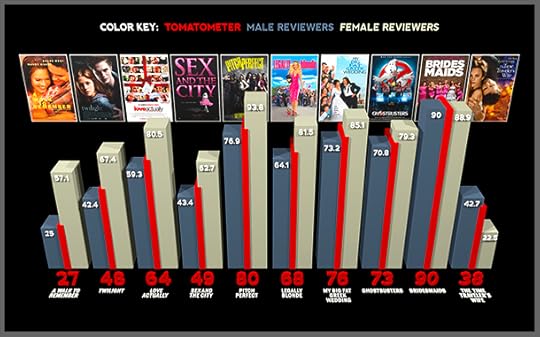

The Tomatometer gender gap is real: We crunched numbers on reviews of 100 films aimed at women, and here’s what we found

Who you gonna call when you need reviews of movies “for women?” Perhaps not Rotten Tomatoes.

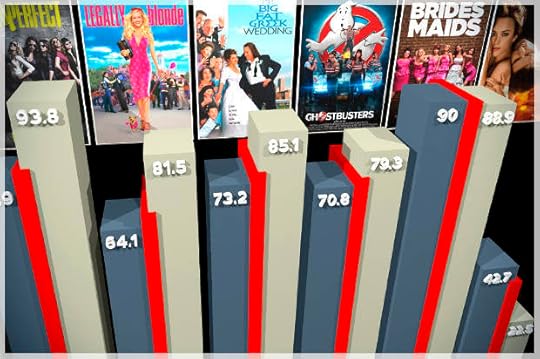

The review aggregator site, founded in 1998, is a hub of film criticism on the Web, the most trusted benchmark for a film’s overall quality. But as Salon pointed out earlier this month, there appears to be a critical blind spot when it comes to movies starring women: The recent “Ghostbusters” reboot, directed by Paul Feig, received significantly higher scores from female critics than their male counterparts. While 79.3 percent of women who reviewed the film gave it a positive review, just 70.8 percent of male critics agreed with them. That’s a difference of 8.5 percent.

But the film, starring Leslie Jones, Kate McKinnon, Kristen Wiig, and Melissa McCarthy as a new generation of paranormal vigilantes, is actually the norm when it comes to how female-centric movies are received.

Looking at movies released since 2000, Salon surveyed 100 films on Rotten Tomatoes that were made and marketed with a female audience in mind. (The large number helps control for selection bias and human error.) These are movies that center women’s experiences, often written, produced and/or directed by women, and they range from “Sex and the City” to “Friends With Money,” Nicole Holofcener’s finely observed comedy of manners about class differences among friends. By and large, these films leaned toward the mainstream, recognizable hits you may have seen and have some opinion on (e.g., “Bridget Jones’s Diary”).

Although we think of the aggregate Tomatometer score as being the objective assessment of a movie’s quality, the survey found there’s more to the story when you break down the scores. These 100 movies, many pejoratively mislabeled as “chick flicks,” received fewer favorable reviews from men—8.4 percent fewer on average. “Ghostbusters” actually falls near the exact middle of the pack: The median gender gap was 8.7 percentage points.

Here are 10 films, at a glance. (The full list is below.) Click the image to enlarge:

In total, 84 percent of the films surveyed received more positive reviews from female reviewers than from men. The movies that showed the greatest divide included “A Walk to Remember,” the Nicholas Sparks adaptation starring Mandy Moore and Shane West; “Twilight,” the 2008 vampire romance featuring Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson; “P.S. I Love You,” a melodrama about a woman (Hilary Swank) grieving the loss of her partner; “Divergent,” the teen dystopia starring Shailene Woodley; and “Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood,” with Sandra Bullock and Ellen Burstyn. All of these movies got critical love from at least 20 percent more female critics than men—some as high as 32.1 percent.

There were a handful of cases where the scales were tipped in the opposite direction. More male reviewers liked “The Time Traveler’s Wife,” the Rachel McAdams-Eric Bana timelord romance; “Uptown Girls,” where Brittany Murphy plays the nanny to a precocious germaphobe (Dakota Fanning); “Monster-in-Law,” featuring Jane Fonda and Jennifer Lopez fighting over a man (Michael Vartan of “Alias”); and “Maid in Manhattan,” also starring Lopez.

Overall, male film critics really liked Jennifer Lopez movies, also giving “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” higher ratings than female critics. They also tended to favor romances where the male character is given equal weight in the narrative (“Two Weeks Notice,” “The Notebook”) or spunky comedies about relationships between women devolving into backstabbing. “Mean Girls,” “Bachelorette” and “Bridesmaids” all rated higher with men, as did Peyton Reed’s “Bring It On,” the 2000 cheerleading satire starring Kirsten Dunst. In the inverse, “The Other Woman,” a comedy about women bond together to get revenge on a man, was also better liked by men.

Men tended to dislike YA literary adaptations and most films marketed to teenage girls. “Pitch Perfect,” which was liked by 93.8 percent of female critics, was rated much lower by men—just 76.9 percent of male reviewers liked it. “Easy A,” Emma Stone’s breakout role, was hugely divisive, with a 14.2 percent gap between men’s and women’s reviews. Male critics also were likely to give a lower score to “weepies” like “Me Before You,” “The Hours,” “If I Stay,” and “Dear John” and most mainstream romantic comedies (see: “13 Going on 30”).

When the mass of male critics men rate movies for women lower than women do, it has a powerful overall effect on how these films are received by the public, bringing down the average Tomatometer of movies aimed at women by nearly six percent (5.77 percent, to be precise). Whereas female critics gave the films surveyed an average rating of “fresh,” with an overall rating of 62 percent, overall men scored them as rotten. Male critics liked these movies just 53.9 percent of the time.

Before we explore why these gaps in scoring happen, check out the full list of films and their scores:

NLang Salon Tomatometer v.2 by Nico Maupin Lang on Scribd

Melissa Silverstein, the founder and publisher of Women and Hollywood, argues that these findings are a reminder that women’s voices matter: According to a June 2016 report from San Diego State University, women account for just 24 percent of film critics. “When women are not seen and heard, our experiences are missed,” Silverstein says.“When we think of criticism we always want to think about it in a binary way—that everyone will agree if a movie is bad and the vice versa. But that’s just not true. We all bring our baggage and our experiences to every movie we see.”

Film critic Angelica Jade Bastien doesn’t believe that the gender gap in criticism is a matter of “conscious, malicious bias.” Bastien tells Salon, “But male critics, since the medium’s birth, have shaped the canon and the markers that are used to judge what makes a ‘good’ film, [and] it doesn’t surprise me that anything that targets women or is viewed as feminine is implicitly seen as less than.”

Stephanie Zacharek, the chief film critic at Time, notes that this is based in a historic bias against “women’s pictures,” the female-centric melodramas popularized by directors like Douglas Sirk (“Written on the Wind”) and Michael Curtiz (“Mildred Pierce”). “Even though men might like them, there’s been a stigma attached to them for a long time,” Zacharek says. “It still hasn’t gone away.”

Aisha Harris, a critic for Slate, adds that in the modern context, these films are referred to as “chick flicks,” which she calls a “pejorative, heavily-female-centric genre” primarily consisting of romantic comedies. She notes, however, that there’s no corresponding category for men.

If there’s a bias against “chick flicks,” surveys have shown that women don’t rate movies aimed at a male audience differently than men do. Even a cursory analysis bears this out: Superhero films like “The Dark Knight,“ “Deadpool,” “Captain America: Civil War,” and “Guardians of the Galaxy” were all rated higher by female critics, while scores were roughly equal for “X-Men: Days of Future Past.”

“As a woman you are raised to understand the perspectives of men,” says Bastien. “This isn’t just cultural conditioning, it’s a matter of survival. We’re able to identify with stories that have male leads in ways male critics weren’t raised having to do in the reverse.”

Silverstein believes that the point isn’t that women make better film critics, but that they “see the world differently — not better, not worse, just different.” That’s why she believes it’s important to have more women at the table, in order to make sure their opinions are heard.

“This is so crucial because when we dismiss content about women we are dismissing women,” Silverstein says.”We should not expect all women to like all movies by or about women,” she adds. “Life doesn’t work like that. People will respond to movies differently based on their race, age, gender, ability—and it should be that way. But when you have so few female voices and voices of color, it is a problem because there is no critical mass. We need multiple opinions and voices. That’s really what all this is about: more opportunities for more voices.”

Get out your wallets, America: It might not be long before we’re bailing out “too big to fail” banks again

Lloyd Blankfein, Jamie Dimon and John Mack testify on Capitol Hill, Jan. 13, 2010, before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. (Credit: AP/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

When you enter the ballot booth this November, keep in mind that you could very well be voting for the captain of sinking ship. You may be voting for the next president who will have to steer us through a financial meltdown, and it’s all because we never truly learned from our mistakes.

The financial crisis of 2008 happened because the banks were too big, they were too opaque and they were engaging in risky business practices. Where are we now? Many of the banks are much bigger, they’re still opaque and they’re still engaging in risky business practices. This is a recipe for (another) disaster.

According to Noam Chomsky and other political and economic experts interviewed for this article, we may be heading to another major bank bailout.

“We don’t actually know a lot of what goes on in banking,” Anat Admati, a professor of finance and economics at Stanford University, told Salon. “We don’t have good monitoring of it.”

Admati said a lot of what banks do is deeply buried in vast financial records, so it’s extremely difficult to follow what industries banks are involved in and what they’re doing. She said the banks benefit from this opaqueness, because it means they can get away with risky business practices while no one knows what’s going on.

The banks are also very interconnected, in various ways. Through contracts and their investments, these enormous and volatile corporations are closely working together and exposing themselves to danger together, which means when one big bank falls, they all start to tumble.

“That’s why there may be a bailout, because the system is so connected, fragile and opaque,” Admati said.

Noam Chomsky, political philosopher and linguist, has said on several occasions that there will likely be another bank bailout in the not-too-distant future, because we haven’t reined the banks in or prevented them from growing. When we asked Chomsky the main reason another bailout may occur, he said that “in brief, ‘too big to fail,’ the implicit government insurance policy, which, according to the [International Monetary Fund], provides most of the profit of the big banks by various means.”

As Chomsky has explained before, the banks can take massive risks for massive profits because they know the government will bail them out if things go terribly wrong. Instead of ending the world of banks that are “too big to fail” and preventing banks from operating in ways that could again sink the economy, we have guaranteed them that the taxpayers are ready and waiting when they make another catastrophic mistake.

One of the major risks banks take is not having enough equity to be considered stable. If there is a financial crisis, a bank with a lot of equity has a buffer that can help prevent it from failing, but many banks currently operate with less than 10 percent equity. “The numbers are pathetic,” Admati said. She said they’ve improved slightly since the financial crash, but their equity numbers are still dangerously low.

Through various mergers and expansions, these banks have become so large that it’s hard to fathom how large they truly are. “All student debt in this country, which is considered a huge problem, is approximately $1.3 trillion,” Admati said. “That is a fraction of JPMorgan Chase. That is like half of the accounting numbers of JP Morgan Chase.” She said these banks have their hands in nearly every part of the economy, and they’re not going to get smaller any time soon unless something is done.

Richard Wolff, a professor of economics emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, also believes we are facing another major bailout if things don’t change soon. He said the “growth of student and auto loan debts relative to mass capacity to carry such debts” could be the cause.

Admati proposed a more sinister future event that could crash the economy, and it makes you think of the USA Network show “Mr. Robot.”

“A cybersecurity [breach] is certainly something that can happen at any time,” she said. “That’s kind of the nightmare.” She pointed to the “cyberheist” that happened earlier this year, where the Federal Reserve Bank of New York lost $81 million to hackers. “Imagine that on a bigger scale,” she said.

Both Wolff and Admati pointed out that the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which came after the 2008 financial crisis and was meant to prevent another one from happening, hasn’t adequately changed how banks operate.

Wolff said Dodd-Frank, as it’s been used, hasn’t prevented big banks from getting bigger and “has failed to address the huge problem of active collusion between major bank lenders and politicians.” He said bankers and politicians are still “cutting dangerous loan deals for mutual benefit.”

“Dodd-Frank tries to do a lot of things,” Admati said. “It gives all kinds of authorities to regulators, the same regulators who failed before, it gives them more slightly different authorities to prevent [another bailout], supposedly, or to deal with it.”

However, Admati said, it has not been used in a way that would prevent another bailout. Beyond the issues that have already been mentioned, banks still have not submitted acceptable “living wills” that are supposed to explain how the biggest banks plan to stay afloat in the face of a future financial crisis. The credit rating agencies that gave bad investments good ratings before 2008 are still in need of major reform. Plus, much of the rules Dodd-Frank was supposed to create still haven’t been finalized years later.

“I’m not happy, because I think they can do much better,” Admati said of the politicians who swore they would prevent another crash.

Things can be done. As Bernie Sanders explained, politicians can use Dodd-Frank to break up the big banks. The credit rating agencies can be reined in. We can finalize the Dodd-Frank rules and enforce them. We can demand the banks be more transparent and carry more equity. And if we do not do these things, we will likely be pulling out our wallets when the banks skip out on the bill again. Remember, it’s the banks that get bailed out when the economy crashes, not the people.

The science behind Hillary Clinton’s problems with trust

Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Large swaths of the American public want Donald Trump to be their president — maybe even a majority, according to an analysis from Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight in late July.

Many people — Democrats and Republicans alike — find this shocking.

Trump made his name as the “You’re fired” guy. He has never held political office, has arguably failed to generate concrete or realistic policy proposals, regularly changes his positions on issues and consistently gets the facts wrong.

This stands in sharp contrast to Hillary Clinton, who has served as secretary of state, senator from New York and first lady of the United States. In his endorsement of her, Barack Obama described Clinton as the most qualified presidential nominee in U.S. history. Presumably experience with, and knowledge of, the system and issues are qualities that make for a good president — so why is this race even close?

How to build trust

Research, including new work from our Human Cooperation Laboratory at Yale, suggests Trump may be successful precisely because of his hotheadedness and lack of carefully thought-out proposals. Being seen as uncalculating can make people trust you.

Hillary Clinton is the opposite of hotheaded. She is careful and calculating — which, despite being a strong asset in actually carrying out the duties of public office, has become a liability in her presidential campaign by undermining the public’s trust in her.

In a recent paper, we found that if you take an action that people like, you come off as much more trustworthy if you decide to act without doing a careful cost-benefit analysis first: Individuals who calculate seem liable to sell out when the price is right.

What’s more, the desire to appear trustworthy motivated participants to act without too much forethought.

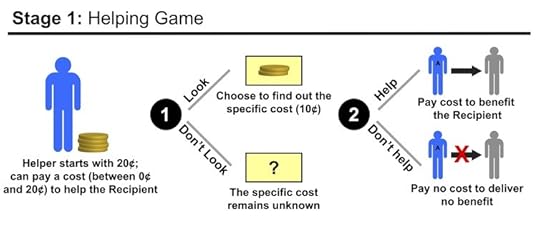

Our research didn’t focus on perceptions of politicians, but rather looked at behavior in a more abstract context. We conducted a series of experiments involving economic decisions between anonymous strangers on the internet. Our goal was to create a scenario that would capture the classic trade-off between self-interest and helping others. This is something that comes up in a lot in politics, but also in all sorts of social interactions, such as in our relationships with friends, coworkers and lovers.

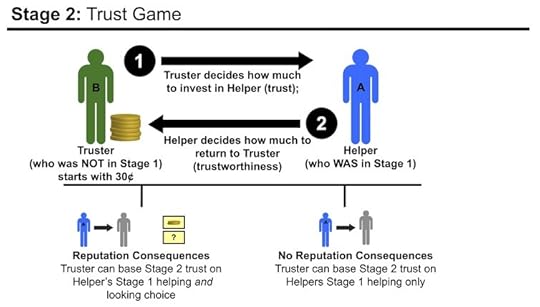

Our experiments occur in two stages, with participants assigned to specific roles.

In the Helping Game stage, “Helpers” are given some money and have the opportunity to give some of it away to benefit another participant.

The second participant is a total stranger who is assigned to the “Recipient” role, and not given any money.

Helpers know that helping the Recipient out will come at a cost — sacrificing a predetermined, but undisclosed, amount of money.

We then give Helpers a choice. They can decide whether to help the Recipient without “looking” at the cost (i.e., without knowing how much money they’ll be giving away). Or, they can choose to find out how much money they’ll be giving away and only then decide whether to help.

Next, in the Trust Game stage, Helpers engage in a new interaction with a third participant. This person is called the “Truster.” The Truster learns about how the Helper behaved in the first interaction, and then uses it to decide how much the Helper can be trusted.

To measure trust, we give the Truster 30 cents. He then chooses how much to keep and how much to “invest” in the Helper.

Any money he invests gets tripled and given to the Helper. The Helper then chooses how to divide the proceeds of the investment.

Under these rules, investing is productive, because it makes the pot grow larger. But investing pays off for the Truster only if the Helper is trustworthy, and returns enough money to make the Truster a profit.

For example, if the Truster invests all 30 cents, that amount is tripled and the Helper gets 90 cents. If the Helper is trustworthy and returns half, they both end up with 45 cents: more than the Truster started with.

However, the Helper may decide to keep all 90 cents and return nothing. In this case, the Truster ends up with zero and is worse off than when he started.

So the Truster bases his decision of how much to invest in the Helper on how trustworthy he thinks the she will be in the face of a temptation to be selfish — that is, how much he trusts her.

We found that Helpers who agree to help the Recipient without “looking” at the cost are trusted more by Trusters. Moreover, they really are more trustworthy. These “uncalculating Helpers” actually return more money to Trusters in the face of the temptation to keep it all for themselves.

Somebody is watching you

We also found that Helpers are motivated by concerns about their reputation.

For half of participants, there were reputational consequences of calculating: The Truster was told whether the Helper looked at the cost before deciding whether to help — and thus Helpers could lose “trust points” by calculating. For the other half of participants, Trusters found out only whether Helpers helped, but not whether they looked at the cost. Our results showed that Helpers were less likely to look at the cost when they knew it would have consequences for their reputations.

This result suggests that people do not make uncalculating decisions only because they cannot be bothered to put in the effort to calculate. Whether this strategy is conscious or not, uncalculating decisions can also be a way to signal to others that you can be trusted.

Uncalculating cooperation in daily life

Our studies demonstrate that there are reputation benefits to seeming principled and uncalculating.

This conclusion likely applies broadly to social relationships with friends, colleagues, neighbors and lovers. For example, it may shed light on why a good friend is someone who helps you out, no questions asked — and not someone who carefully tracks favors and remembers exactly how much you owe.

It may also reveal an unexpected reason for the popularity of rigid ethical guidelines in philosophical and religious traditions. Committing to standards like the golden rule can make you more popular.

To trust Trump or Clinton?

Our studies may also help to shed light on Trump’s appeal. One of his greatest advantages appears to be the authenticity that he conveys with his emotionally charged behavior.

But it’s important to understand uncalculated decisions will benefit your reputation only if the actions you end up taking are perceived positively. In our experiments, Helpers who decided not to help without calculating the costs seemed especially untrustworthy — presumably because they seemed committed to be selfish no matter what. Similarly, Trump’s impulsiveness may be a plus for those people who support his values, but a huge turnoff to those who do not.

In contrast, Clinton’s persona is often unattractive even to those who support her values — because it suggests that she may not stand by those values when the cost is too high. This may shed light on why she does not inspire more enthusiasm among some liberals, despite her experience and progressive record.

However, there’s an important nuance to what it means to be “calculating.” One sense of “calculating” is self-interested: Before you agree to adhere to your ethical principles, or to sacrifice for others, you consider the costs and benefits to yourself — and you follow through with doing the “right” thing only if you conclude that it will be best for you.

Another way to be “calculating” is to carefully consider what’s right for others. Instead of acting on her gut, a policymaker could conduct a complex analysis to figure out the best way to implement a policy to maximize its benefit to the population.

Our theory and experiments apply only to the first sense of “calculating”: They suggest that engaging in self-interested calculations is what undermines trust.

But in what sense is Trump uncalculating — and in what sense is Clinton calculating?

Of course, there’s room for debate, but a common argument in support of Clinton is that her calculations reflect her ability to effectively play the game to deliver the most progressive policies possible, given the constraints of our two-party system.

To win, Clinton needs to convince voters that her calculations have their best interests at heart.

Jillian Jordan is a Ph.D. candidate in Psychology at Yale University. David Rand is an associate professor of Psychology, Economics, Cognitive Science and Management at Yale University.