Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 696

August 7, 2016

The paradoxical campaign of Donald Trump: Why his many contradictions and flip-flops don’t matter

Donald Trump, Donald Trump (Credit: AP/Carlos Osorio)

The myriad contradictions of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign have become so clear and apparent in recent weeks that even his most partisan sycophants have to be wondering to themselves (not out loud, of course) whether their leader actually has any genuinely held beliefs. While it’s no secret that Trump has a long history of flip-flopping — from his shift on controversial issues like abortion and gun control to his ever-changing opinion of Hillary Clinton (whom he lavished with praise for many years before his presidential run) — the contradictions have become so pervasive lately that even Karl Marx would have been confounded.

Consider the candidate’s selection of Gov. Mike Pence as his running mate. Trump has railed against free trade deals like NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) throughout his presidential campaign, yet the man he chose to be his vice president has never seen a trade deal he hasn’t liked. Every “stupid,” “horrible” and “disastrous” trade deal denounced by Trump over the past year has been wholeheartedly supported and championed by Pence.

The Indiana governor was also a strong supporter of the Iraq War, and voted for it as a congressman — as did Hillary Clinton as a senator from New York. But in an interview with “60 Minutes” last month, Trump said that he doesn’t care about this fact in regards to Pence because it was “a long time ago,” people were misled, and “he’s entitled to make a mistake every once in a while.” When it came to Clinton, however, this fair assessment was not applicable (apparently women are not as entitled as men to make mistakes every once in a while).

Like all human beings, Trump is large and contains multitudes; but unlike most adult human beings, he seems to lack basic critical thinking skills. The man’s self-contradictions are legion: he sees “NATO as a good thing,” yet he think’s it’s “obsolete”; he has claimed not to “condone violence in any shape,” yet he encourages violence against protesters at his rallies; he has professed his love for Mexican people while simultaneously scapegoating Mexican immigrants; he has bragged about self-funding his campaign, only to reverse course; he has said that he could eliminate the United States’ debt in eight years as president, even while his proposed tax plan would, according to various analyses, add more than $10 trillion to the debt in a decade; it goes on and on.

Beyond his many contradictory positions and statements, Trump is also an extremely paradoxical figure. A wealthy real estate tycoon born into great wealth who is seen by many as an archetypal common man with his unsophisticated (and often vulgar) demeanor (his son has called him a “blue-collar billionaire”). Moreover, the billionaire has made much of his wealth by scamming and hustling the same working and middle-class people that he now claims to fight for (e.g., Trump University, his casino ventures), and was a big donor himself before becoming an anti-establishment politician.

Incredibly, these contradictions and flip-flops never seem to hurt Trump (as they would any other candidate). This can be mainly attributed to the fact that his political success is more a product of his attitude and image than his policies and political positions. “Trumpism” is an Us vs. Them mentality, not a coherent ideology or political philosophy. This mindset is recurrent in past reactionary and populist movements in American history.

In his essay “From Founding Violence to Political Hegemony: The Conservative Populism of George Wallace,” associate professor at the University of Oregon Joseph Lowndes explores the populism of the infamous Alabama governor and frequent presidential candidate, who, like Trump, was also a paradoxical figure replete with contradictions:

“[George Wallace was] an agitator who migrated between contradictory political positions. [His] paradoxes were legion: as the simultaneous embodiment of the ‘average citizen’ and a self-conscious caricature of a redneck, he was a politician with whom many Americans could identify even as they differentiated themselves from his image. He praised the police and called for stronger law enforcement and more punitive sentencing, yet he was always associated with disruptive violence himself… And although he always claimed he was not a racist, racial demonization was fundamental to his success.”

Like Wallace, Trump is a demagogue and an opportunist who claims to fight for the people and against the country’s elites. “Big business, elite media and major donors are lining up behind the campaign of my opponent because they know she will keep our rigged system in place,” declared the billionaire in his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention two weeks ago. “She is their puppet, and they pull the strings. … I AM YOUR VOICE.”

It is of little importance that Trump’s actual policies (at least those that he has put forth) would hurt the people he professes to fight for — once again, it is his Us vs. Them mentality that matters to so many of his supporters.

Over the past week, Trump’s increasingly erratic and “un-presidential” behavior has started to disturb and worry many Republican Party officials (yes, it’s hard to believe that they’re only now getting worried). And if someone had been living under a rock for the past year, it would seem entirely plausible that his campaign was about to implode. But Trump has been on the verge of political implosion for some time now — yet here he is, the still competitive Republican nominee for president. The contradictions of the Trump campaign are now so ubiquitous that they have been rendered almost meaningless; the candidate’s success in November will depend not so much on his political positions as on the American public’s state of mind. If fear and resentment prevail over rationality and tolerance, Trump’s long-shot presidential bid could change American history.

August 6, 2016

Chasing Ennio Morricone: Our family’s race across an ocean and against the clock to see the concert of a lifetime

Ennio Morricone (Credit: AP/Balazs Mohai)

The Italy Fund. That’s what my mother used to call it, the extra money she would sock away — twenty dollars here, fifty there, another hundred under there. It began, I think, in my late elementary school years, the idea that our family would somehow financially be able to swing a four-person trip to the country our family fled at the turn of the century. We’d never been to Europe so we might as well start with Italy. Go out to dinner? Italy Fund. New sweater? Italy Fund. But time flies and before we knew it my older sister Maria went to college. Two years later I too went to an overpriced academic institution my hard-working parents helped pay for (and I’m still paying for). With two kids in college and life being what it is, The Italy Fund was put on hold.

Someday, maybe, we’d say.

Maybe we’ll go. Someday.

***

Two years ago, in 2014, Ennio Morricone, the Italian composer famous for movie scores from “Cinema Paradiso,” “Once Upon a Time in the West” and “The Mission” (and now, for his Oscar-winning score from Tarantino’s 2015 Western “The Hateful Eight”) was scheduled to play at Barclays Center in Brooklyn. Maria spotted it first, and, both of us living in New York, we decided to buy tickets for what would be a surprise birthday gift for our father. We’d always been Morricone fans, but it was our dad who loved him most. The concert felt like a special thing we could do together. We’d been through a lot, the three of us, since our mother died seven years earlier. We were still working out how to make new memories and be happy.

It really is amazing how quickly life can happen to you. You can plan all you want, start your Italy Fund and dream of someday, but you can get into a car accident and die just as easily, it seems, as putting on your pants in the morning.

Poof!

Just like that, Mom was gone, and someday went right out the window along with everything else we thought we knew about whatever this mad spinning world is we call life.

Two weeks before the concert Morricone cancelled. Health reasons. His back. He’s in his eighties, so who can blame him? (I sort of did). To make matters worse, in a statement to the press Morricone announced he would never, ever do another concert in America.

That, it would seem, was that.

“We’re going to see this guy someday,” Maria said, defiantly. “I don’t care what it takes. We’re doing it.”

Someday. Maybe.

***

In the two years since Morricone cancelled on us and America, our father got engaged. The wedding is planned for this coming fall. It’s been almost a decade since our mother died, and remarriage was probable. Inevitable, even. And yet. And yet even as it was here, just like her death, I still couldn’t quite believe it. Growing up, my life consisted of the four of us — Dad, Mom, Maria and me — and over the last nine years it’s been an adjustment getting used to the empty chair at the kitchen table. Every time I would go home it was a kind of silent assault, the only placemat sitting there mutinously without a plate. As years passed, however, the feeling someone was missing wasn’t as pervasive, as gut-wrenchingly obvious. I can’t remember exactly when it happened, but just like the moment your eyes finally adjust to the light, one day our family that once was four became three. And it was okay. Normal, even.

The Three Musketeers, we’d call ourselves.

I’d gotten used to it. Finally.

And then.

***

Morricone. Rome. May 2016. Maria and I were sitting in a bar in April when she saw it on her phone. “He’s playing a concert there on the twenty-second. Do we do it? A seventieth birthday gift?” she asked. May was a month away. It seemed absurd, insane really, to contemplate booking a trip to Europe at that point. And yes, our father was turning 70 in June, but was a trip to Europe really necessary? Surely we could just send a nice card? But I knew what Maria knew, that everything was about to change. That this nine-year run as The Three Musketeers was ticking down like a time bomb, and after the explosion the landscape was going to look dramatically different. Dad had a new house to move into, a new life to start. And who could blame him? We certainly didn’t. But we also weren’t quite ready to let go.

And so it happened. Together over wine we decided that someday, finally, had arrived.

“Let’s do it,” I said.

We booked the concert tickets first, three clocking it at more than one month’s rent (I got an alert from my credit card company: YOU MAY HAVE BEEN COMPROMISED. I have, I thought, by pure psychosis). The trip would be nine days. Dad’s first visit to Europe, our first trip to Italy.

Carpe freaking diem.

***

Dear Customer,

We are contacting you to inform you that Ennio Morricone at Auditorium Parco della Musica — Sala Santa Cecilia in Rome has been cancelled.

Another cancellation. Health reasons. His back. Again. By this point it was starting to feel like we were cursed. Or this trip was cursed. Or this guy was definitely on death’s door, in which case maybe he should stop scheduling concerts and getting people’s hopes up. You know, people who book very expensive trips from other countries just to see these concerts.

“It says he’s still playing his Paris dates at the end of that week,” Maria said, and I knew what was coming next.

We’d come this far.

It is probably certifiable what we did, hands shaking, hearts pounding due to the sheer expense of it all (another month’s rent?! Two?!), booking three more flights, this time from Rome to Paris, a hotel in Montparnasse, and three tickets to see Morricone at the Palais des Congrès. It wasn’t about money at that point (though, I mean, it sort of was), it was that sickening, powerless feeling of not being able to control your own destiny that neither Maria nor I wanted to succumb to. Not again. With death happening to us the way it did, ruthlessly fast behind our backs, it was our turn to try to reclaim something. To take something back. On our terms. For us. So we decided Morricone was happening. Not later, not someday, now. A shot in the dark to be sure, but our shot to take. It was admittedly a cobbled together, last-ditch effort to hold onto something. Crazy? Maybe. But in that moment — stacked up against the entire timeline of our lives and all that had happened — doing this mattered more than anything in the world.

A week before we were scheduled to leave:

Dear Customer,

We are contacting you to inform you that the time for Ennio Morricone at Palais des Congres, Paris has changed. The event will now take place on September 24, 2016.

I wish I were kidding.

I am not.

***

So there we were, The Three Musketeers on a plane from JFK to Fiumicino that would end in Paris with no one seeing Ennio Morricone. But the powerful play goes on, now set against a European backdrop. There was nothing left to do but go. When we arrived we managed in our best guidebook Italian to order cappuccino and ask directions. For lunch our second day we poured prosecco into plastic cups and ate panino on the steps of an old church. I was proud of the three of us for being so cool, for finally doing the thing we’d always talked about. Proud too of Dad for going along with this madcap adventure his daughters basically forced him on.

Over the years we’d come to trust each other in a way we hadn’t before. As close a family as we’d been when my mother was alive, over the last nine years, through the ups and downs of grief, of one or all of us losing it at one point or another as we grappled with learning how to be in the world together without her, I’d come to feel like I couldn’t function without them. Who are we without each other, these only people in the world who knew who we were as a family before?

In Paris our hotel turned out to be a shithole (oops), and there was a moment when Maria was on her laptop frantically searching for new hotels, I was yelling at the front desk manager, and Dad was sitting on the closed lid of the toilet because it was the only clean spot in the place. So, okay, yes, we had our low points. But we bounced back.

We are The Three Musketeers, after all.

We found a new hotel, and at the Arc de Triomphe Dad stood in awe, the World War II buff in him picturing German troops and horse-drawn artillery advancing down the Champs-Élysées in 1940. And now to be here? Standing in that very place? He had the same expression he did the day we were at the Colosseum and he looked about the place in near disbelief.

“I never thought I’d be here,” he said. Maria and I looked at each other. For us, that was enough.

In fact, it was everything.

***

Morricone, that old maestro with major back issues. We chased him all the way to Europe to get away from a reality that felt like it was closing in on us back home. We had no idea what we were doing, Maria and I, but we knew we needed to give our family a memory before it became a different family entirely. One last hurrah as The Three Musketeers. Our Airbnb in Rome had a patio out back, and after dinner we’d open another bottle of amazing yet affordable wine, and while Dad and I smoked a cigar, Maria played Morricone full blast on her laptop.

It wasn’t the Auditorium Parco della Musica, but I’ll be damned if we weren’t having the time of our lives.

As for Maria and me, it felt like the last phase of growing up and figuring out that grand old tradition of leaving home, the past and all it used to be but isn’t anymore. Over a bottle of champagne (two?) in our hotel room our last night in Paris (Dad was tucked away on another floor), we let the tears fall freely. That night felt like the end of something, an intermission before next act. The act in which our father remarries and the house that’s ours isn’t ours anymore. After Italy, after Paris, we knew we had to go back home and decipher from a lifetime of memories what we wanted to keep, and throw away what didn’t fit in our lives anymore.

It would be another part of the necessary letting go.

This trip, for all its last-minute insanity, for all its Run Lola Run, was, I think, just our inability to relinquish the past without a fight. We couldn’t say goodbye and fade into the night as though all of those years before she died didn’t matter. As though all of those years without her weren’t just as important.

And yet.

You can travel the world ten times over and everything you left behind will still be waiting on your doorstep when you come home. The facts, regardless of the miles logged or wine downed, remain the same. In life there simply are some things you cannot fix. After all, nothing lasts forever (even the Colosseum will have its day). People die. People move. People move on. Houses are sold. New ones are bought. Hearts are broken and resuscitated to love again. We don’t forget but we move forward. We keep living and choosing and loving and making new memories and getting on planes and chasing Morricone and experiences and things that make our hearts beat faster because we can.

Because we have to. Because we are here.

And Morricone is still out there. We’re rescheduled to see him in Paris in September and by God we’ll be there, come hell or high water.

Only this time, it will be four of us.

Democrats Abroad: What the Democratic Party could learn from its overseas footsoldiers

This piece originally appeared on BillMoyers.com.

One of the most memorable moments from this year’s Democratic convention was the touching show of love between Sen. Bernie Sanders and his older brother, Larry.

The elder Sanders, a resident of the United Kingdom, was elected as a delegate for Democrats Abroad (DA), the official international arm of the Democratic Party. On the convention floor, his fellow Democratic expats gave him the honor of announcing his own vote, in a voice heavy with emotion, in favor of the presidential candidate he called “Bernard.”

That poignant moment during the official convention roll call put a spotlight on Democrats Abroad, a more than 50-year-old volunteer organization, without staff or a budget, that the Democratic Party created to mobilize voters living abroad.

The approximately 8 million American expats make up a voting bloc nearly double that of Washington state, the 13th most populous state in the nation. Were they to constitute a state, they would have about 14 electoral votes. Americans abroad are students and retirees, military and diplomatic personnel, people on short- and long-term job assignments, Americans with foreign spouses and their children.

Within the DNC, Democrats Abroad operates like a state party, doing what every other state party does: It organizes its own presidential primary and sends delegates to the convention to pick the presidential nominee. There’s no real GOP equivalent: Republicans Overseas is not recognized by the Republican National Committee as a state party.

This year, DA’s global primary had record turnout. The 34,570 voters who cast ballots exceeded the number of Democrats who showed up for state party presidential caucuses this year in Nebraska, Idaho, Alaska, Hawaii and Wyoming, according to votes compiled by University of Florida turnout expert Michael McDonald’s United States Election Project. Sanders overwhelmingly won the competition, receiving 69 percent of the vote and nine of the 13 committed delegates — including his big brother, Larry. (Democrats Abroad also has eight superdelegates, but each receives only a half-vote, unlike every other state party — they have twice as many DNC members as they might normally have).

Americans living abroad play a significant but little-noticed role in general elections across the country as well. They organize, phone bank and raise money for candidates, and vote (doing so by absentee ballot at their last U.S. voting address).

Democrats Abroad coordinates much of this activity and helps expats request and cast their absentee ballot using its online tool.

Expat votes often make the critical difference in close contests across the country.

Just ask Sens. Al Franken (D-MN) and Jon Tester (D-MT) — both of whom were elected by slim margins in 2008 and 2012, respectively. The number of votes they received from abroad exceeded their margins of victory in their first Senate races. Franken sometimes jokes that 300 Minnesotans in France decided the outcome of his race. (Of course, he could and probably does adapt the same joke to gatherings of Democrats in Duluth, too, in order to illustrate the importance of voting.)

The political relevance of Democrats Abroad and the expat community extends beyond their status as a voting bloc. In the 2016 Global Presidential Primary, Democrats Abroad proved that the primaries can be welcoming as well as efficient, avoiding many of the issues that plagued the 2016 primary process stateside.

For example, unlike some other state parties:

Democrats Abroad enables registration for its primary online.

Primary voters can join the party as late as primary Election Day and still vote (with an official, not provisional ballot). That’s about as open as a closed primary can be.

Party members can start voting via email a few weeks before the official primary day. Mail-in “remote” ballots are accepted during this time frame as well to accommodate the many American who live in places where DA is not physically present.

Members of Democrats Abroad can vote in the Global Presidential Primary for their choice for president, but they can also vote “down ticket” via absentee ballot in their home state primary (for U.S. Senate, U.S. House, local tax assessor, etc.), as long as they pledge not to vote again for a presidential candidate. This allows students and newly situated residents to participate more easily during primary season.

In 2004, DA hosted a caucus, a largely antiquated and undemocratic form of elections. Since then, voter turnout for the global primary has increased 15-fold. And despite non-restrictive voting procedures, there has been little concern for voter fraud.

A strong, accessible and truly representative party and primary system is critical for those living abroad. Since expats are dispersed across the globe, there are neither the resources nor personnel to have polling locations within commuting distance for every citizen. Online and absentee voting measures therefore allow for equal access to the vote.

Moreover, since the issues confronting an expat are drastically different from an ordinary citizen, Democrats Abroad plays a particularly critical role — it is the only institutional body equipped to understand and advocate for these concerns. Many expat voters choose to participate in the global primary, as opposed to their state primaries, for this reason: the more participation in DA, the more influence it has within the DNC and therefore the more likely expat concerns are heard.

Currently the No. 1 policy issue for Americans abroad is the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, known as FATCA. Designed to catch the “fat cats” who hide their wealth in offshore tax havens, this law has had many unintended consequences for the expat community: people have had their bank accounts closed, their mortgages rescinded and suddenly find themselves slammed with huge fees and penalties for non-compliance. So, this year, Democrats Abroad worked diligently to educate both the campaigns of Sanders and Hillary Clinton about this issue. The lobbying worked: a FATCA reform plank is now included in the party’s platform.

American expats did not always enjoy meaningful representation.

Party politics is messy and often inefficient. And in today’s political climate, one filled with distrust and apathy, ensuring representation and active participation is more important than ever. Democrats Abroad serves as a very successful model for how other state parties can reinvigorate faith in the party.

Adopting same-day registration for primary elections, using “remote” ballots to guarantee more participation, and intriguingly, limiting the superdelegates’ votes to just one-half of a pledged delegates’ vote are all concrete reforms that the party could adopt to restore trust with the grass roots.

For the majority of the 20th century, there was no party apparatus abroad. It was only in 1964 when Democrats in London and Paris began to politically organize, coordinating a fundraising campaign for Lyndon Johnson, that the foundation for what would become Democrats Abroad was created.

While fundraising proved successful, there was never a guaranteed right to an overseas absentee ballot. So, after a decade of organizing, expats pressured President Gerald Ford to sign the Overseas Citizens Voting Rights Act of 1975, which gave Americans abroad this right. In the following year, committees of Democrats Abroad in a number of countries held elections to choose delegates to the 1976 convention that nominated Jimmy Carter for the presidency. It was a first, small step that led eventually to today’s Global Presidential Primary.

If there is a lesson in all of this, it is that winning representation and creating well-functioning elections takes time and effort. This means engaged citizens pushing for democratic innovations. For Democrats Abroad, the next step will be to get paid staff operational resources, and they’re entertaining the possibility of a congressional delegate (as D.C. has) to represent its interests in the U.S. Capitol. For the national Democratic Party, activists and party officials must work together to empower all voters and better represent the party’s members, no matter where they live.

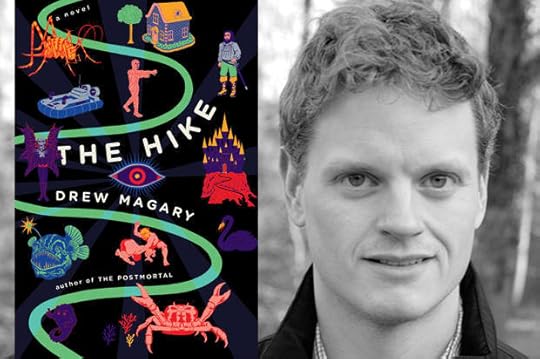

“A folk tale, but with swearing”: Drew Magary on his debut novel “The Hike”

Drew Magary (Credit: Patrick Serengulian)

My first exposure to Drew Magary was his work on Deadspin, specifically his recurring column “Balls Deep,” which frequently managed to (1) make me laugh really hard, and then (2) immediately feel guilty for laughing so hard. He has since gone on to become a regular contributor for GQ, and to write for a number of other equally fancy places, displaying versatility and a breadth of topics within his range. But the main thing he does has not changed — a knack for rhythm, conversational and engaging. A blustery patter that frequently erupts into full-throated rants with liberal use of the CAPS LOCK. Talking fast and loud and profane, the fastness and loudness and profanity collectively having the effect (whether intended or not) of disguising, or at least delaying, the discovery by the reader of how smart a writer Magary is, and how, amidst the ALL-CAPS screaming, one might detect undertones of vulnerability and emotional honesty, surprising qualities to his writing which have a way of modulating the foul-mouthed rants into something interesting and polyphonic and possibly revealing about American dude-dom in the 2010s, or something like that, all of which becomes evident when you read his fiction, especially his new novel, “The Hike.” Also, he’s really good at dick jokes.

Magary and I talked recently about “The Hike,” nostalgia, business trips, video games and the inspirations for the mythical beasts in his book.

I mean this in a good way: Your new novel is demented.

A man, Ben, while on a business trip goes on a hike, during which he encounters, among other things, murderous dogfaces, sentient crabs, and a giant woman whose typical meal is a stew made out of several dudes (I’m picturing an enormous bowl of Campbell’s Chunky Soup with adult-male torsos floating around).

I’m asking because, despite all of the above, at the core of this insane and entertaining story is, I think, a story about a guy trying to get home to his loved ones—and the portions of the book that give us glimpses of Ben’s domestic life are among its most affecting and emotionally direct. Ben, like you, is married with kid(s). So, and I apologize for asking, but is there anything autobiographical in “The Hike?”

The beginning of the story actually all happened. I was on a business trip and staying at this creepy inn deep in the woods, and I was the only guest there, and the clerk said there was nowhere to walk outside even though there TOTALLY was, and then I found a path anyway, which was fucking WEIRD. So all that was based on an actual experience I had. In a way, the book is just an allegory about the loneliness of business travel.

As for Ben, there are parts of him that are me, but parts that very much aren’t. Obviously, I lifted a lot of his parenting and marriage insights from my own, and I also grew up in Minnesota, but then I went ahead and took a lot of liberties with him, compared to my own dull backstory. That’s the fun of writing fiction. You take what you know and then twist it so that it’s way more interesting. If the character really HAD been me, you would have rooted for him to get killed by page 20.

The “loneliness of business travel” has inspired a number of moving and funny stories in recent years. What’s that about? What makes it such a revealing and/or representative part of modern experience? And how did it play into your process of conceiving of and writing “The Hike?”

Well, when I travel for business, I’m dead alone. And I have a wife and three loud kids, so being alone out in the ether feels kind of alien. I can feel how alone I am, and how far away my loved ones are. And then I visualize all kinds of nightmares where I can’t get back to them, or vice versa. There’s this sort of respite you get being away from loved ones, but you’re always keenly aware of the fact that they’re gone. And sometimes that really wears on me, like if I’m tossing and turning at 3 a.m. in some fucking hotel room somewhere.

You certainly capture that alien feeling in the story — even in what is primarily a comic novel, there’s a palpable sense of horror. Did you write significant portions of it while traveling on business? And speaking of that business, is your travel primarily for GQ, or Deadspin, and/or other publications that you work for?

When I travel, it’s usually on assignment for GQ, or for speaking gigs or whatever else. Sometimes I get trips where I can see friends, but sometimes you get sent places where you know literally no one, and that can get really lonely.

But I actually wrote the whole thing at home. I hate writing on the road, only because my back is all fucked up and laptops do me no favors.

While on his hike, Ben encounters a series of fantastical creatures and beings — some foes, some allies, most of them impossible to explain out of context (you just have to read the book)! Were there any particular sources of inspiration, things you’ve read/watched/played that were part of the mix?

It was a mix of completely random shit. I remember I caught my reflection in the bathroom mirror once in the middle of the night and my eyes were glowing, and THAT went in. So just bits and pieces like that. But the big inspiration for me was a woman named Ruth Manning-Sanders. Back when I was a kid, I used to hit the library and take out these folk tale compilations of hers called “A Book of Demons” and “A Book of Dragons” and more. She had a compendium for every creature and magical animal — stories from every country — and I read pretty much all of them. And the tales usually had to do with enchanted objects and brave strong lads who find them. I was way into those books, and the book (hopefully) pays tribute to them.

There’s an atmospheric quality to the book, a mix of creepiness and melancholy. Even a sense of quietness. The crab, Fermona, the woman in the forest, while they’re definitely eerie, they’re also kind of lonely. Now that you mention those books, and your affection for them, something clicks for me — it might be that the quality of the atmosphere you evoke is actually nostalgia. That’s not really a question, is it? Let me see if I can pull one out of there. How about: Is nostalgia something you thought about at all in the writing?

I don’t know about nostalgia, except in the way the story is told, because I loved those old folk tales and just wanted to go live inside something like that for a little while. I do know that, when I’m alone, my past is the only companion I have. My family’s not there, so all I’ve got are the pictures and memories of them. And then there’s memories of the world beyond them. Sometimes I’ll think about what happened a day ago, sometimes what happened 20 years ago. That all comes with me whenever I’m alone, and sometimes that’s nice and sometimes it’s a thing I gotta reckon with.

The other thing is that, ever since I was a kid, I always wanted to walk into the forest and find something there, like a door. C.S. Lewis-type shit. I think that’s natural, right? Sometimes you just wonder about what’s it like to get lost.

That’s one of the most appealing things about the story, is watching Ben get more and more lost. How the narrative propels Ben into his adventure, and that sense of anticipation as we get deeper into the woods as Ben gets increasingly far from anything familiar or comfortable. Ben gets lost in more ways than one, doesn’t he? Is it fair to describe this as a metaphysical novel? And if not, then how would you describe the novel?

At one point, I considered subtitling it “a folk tale” but that sounded so pretentious and annoying that I couldn’t bring myself to do it. But if I were reaching for some kinda description, that would probably do it. A folk tale, but with swearing. And obviously there’s some fantasy and horror and existential shit going on, but I think the main thrust is to tell people it’s a good-ass yarn. We need more yarns, man. I am pro-yarn.

The book feels both timeless and up-to-the-moment contemporary — you said “folk tale” and the book jacket says a mix of “fairy tale” but also… video games, which I think is accurate. There’s this idea of staying on The Path being of paramount importance (and conversely, that straying from it is lethal and dumb), which is a rich and layered metaphor, and for me evokes all kinds of things — the forced march of linear games versus the freedom of open-world games, and how games are (or aren’t) like stories. Were video games on your mind at all, in the writing of this? Any games in particular that you play or played during the writing, or maybe played as a kid that went into the mix?

Yeah I played a lot of “King’s Quest” when I was a kid, and that factored in heavily, because those games were rudimentary point-and-click fairy tale games that didn’t always make sense. Like sometimes you would leave a spot and then have to come back five times in order for an important thing to appear. And I’ll always remember those games fondly, even when they were infuriating.

What are you working on next?

As for next stuff, I’ve tried goofing around with novel #3 this spring but it’s been a little bit futile. This isn’t unusual for me. I only wrote “The Hike” after false starts with two other attempts at a second novel. So hopefully I take a walk this fall and witness an alien invasion and that’ll be all the juice I need.

This is not a moment, it’s a movement: More at stake for Sanders supporters than merely the 2016 election

(Credit: Reuters/Jim Young)

The chaotic and disorderly start to last week’s Democratic National Convention was unsurprising after Wikileaks released nearly 20,000 embarrassing DNC emails just days earlier that implicated top party officials in favoring Hillary Clinton over Sen. Bernie Sanders during the presidential primaries (though most Sanders supporters had already suspected this, party officials had strongly denied any kind of favoritism).

On the first day of the convention, Sanders delegates were loud and outspoken in their discontent, booing the recently resigned DNC Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz off the stage at her state’s delegate breakfast and drowning out convention speakers with every mention of Clinton’s name. Outside the Wells Fargo Center, meanwhile, thousands of protesters flooded the streets of Philadelphia — though the convention area was sealed off by a four-mile long fence, which kept things relatively peaceful for attendees.

This tense and contentious climate continued throughout the week, with a group of Sanders delegates staging a walkout on Tuesday night after Clinton was formally nominated and outside protests becoming increasingly unruly as the week progressed.

In spite of all this disorder, the Democratic convention was, broadly speaking, a success — especially when compared to the previous week’s Republican National Convention, which some of the most prominent Republican figures declined to attend because of their party’s nominee. For Democrats, the disunity was as plain and evident as Donald Trump’s xenophobia; but the speakers were effective and inspiring, which, in an election against Trump’s intolerable negativity, was probably enough.

Still, the stark differences and disagreements between Clinton and Sanders supporters were on full display, and this infighting will no doubt shape the future of the party. In a nutshell, the former are predominately Democratic partisans who subscribe to a binary way of thinking about politics (e.g., Republican vs. Democrat, conservative vs. liberal), while the latter tend to be progressives who champion principles over party and reject partisan narratives. At the convention, the former rolled their eyes and shook their heads in disgust whenever the latter booed or chanted (nothing irks Democratic partisans quite like rudeness), and were attending for their candidate and their party. The latter, who showed up with pro-Palestinian rights and anti-TPP signs, attended the convention for their candidate, but more importantly, for their movement.

This conflict between the party faithful and those who are committed to a broader movement reveals a struggle currently taking place in the Democratic party — and this struggle highlights the difference between electoral politics and movement politics, a subject that Bruce Shapiro, contributing editor at The Nation, touched on in an article last week:

“Elected officials, even the best and most principled, operate within the parameters of possibility that they discern in their constituency. In that sense, elected officials — and American presidents most of all — are the end of the political digestive system. Electoral politics is usually the last place change gets felt… Movement politics, on the other hand, is about reshaping and redefining those parameters. Moving the goalposts.”

For Sanders and many of his supporters, the political revolution is far from over; but at the same time, the next few months must be dedicated first and foremost to stopping Donald Trump (i.e., electoral politics). In a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Jane Sanders explained her husband’s decision to endorse Clinton: “His choice was to endorse [Clinton] — but, at the same time, fight like hell to keep the revolution alive, and keep alive the issues that we all stand behind. So we need [our supporters]. We need them engaged, and we need them to participate. And whatever they decide, it’s their conscience, and they should decide whatever they want. Our job is to defeat Donald Trump; our conscience says we can’t have that.”

Bernie supporters seem to have taken the senator’s call for a political revolution to heart, and in April, a group of Sanders campaign staffers and volunteers introduced a plan to “recruit and run 400+ candidates as a single, unified campaign with a single plan” for the 2018 midterm elections. This bold initiative, called “Brand New Congress,” is a nonpartisan campaign based on shared principles rather than party identification; a fusion of electoral politics and movement politics with the ultimate goal of electing principled non-politicians across the country. In a statement to this author, co-founder of Brand New Congress and former Sanders volunteer Saikat Chakrabarti explained the group’s aims:

“The candidates would be running a unified campaign with a single bold plan to, among other things, fix our criminal justice system, rapidly move to 100 percent renewable energy, end the corrupting influence of money in politics, and invest massively in our industries to end our current income inequality by creating high wage jobs for everyone… We plan to win by running these candidates in a single, unified, presidential-style campaign that will, like Bernie’s campaign, be able to focus large amounts of small dollar donors and grassroots volunteer efforts towards a single powerful goal. Our goal is also to create a Congress that accurately represents the demographics, gender, and wealth of Americans.”

For the next several months, progressives must keep in mind the difference between electoral politics and movement politics. Defeating Donald Trump in November is imperative, but so is maintaining a popular movement long after the votes are cast. “Sanders allowed us to realize that there really are millions of us who share similar goals and together we have enough power to outraise and outact our billionaire-backed rivals,” remarked Chakrabarti. “But to actually achieve the changes we want to see, we need to strategize for the long term because this revolution is not going to happen overnight. We should assume that until the actual problems in this country are fixed, the movement and desire to fix those problems is not going to go away. No one person or group saying that the movement should continue is going to keep it going — the movement is going to continue because we have some very urgent crises in this country, we know that these crises can be solved, and we now see that the people actually do have the power to solve them.”

Sanders’ legacy will be determined not in the next few months, but in the years ahead; and if his supporters remain as committed to the cause in the future as they are today, then the senator’s legacy is in good hands.

David Cross brings “social justice warriors” and the right together: “Through their hatred of me, [they] bond”

David Cross (Credit: AP/Victoria Will)

The comedian David Cross has been all over the place across a career that’s ranged from the oddball sketches of “Mr. Show” to the series “Arrested Development” to standup to appearing in the “Alvin and the Chipmunks” trilogy — that last one a surprise to fans of his edgier fare, like cult-favorite comedy “The Increasingly Poor Decisions of Todd Margaret.” He’s also, along with the jokes, called out people he considers reactionaries or hypocrites, like Creed lead singer Scott Stapp and the comedian Larry the Cable Guy.

Cross’s new special, “Making American Great Again,” which dropped on Netflix yesterday, comes from a standup appearance in Austin. It’s not all political, but its political bits are gutsy and hilarious. At times, it gets close to being in very bad taste.

Salon spoke to Cross from New York. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

It’s funny — your special starts out with this observational humor about family holidays and absurd stuff like buying luggage at an airport, and then you slam right into political material. Donald Trump, Ayn Rand, gun control. I wonder if the same thing kind of happened to you personally. If you just realize that politics was getting so nutty you had to go back to it, you had to focus on it, full bore.

Well, no. The reason that occurs the way it does, in the sequencing it does, is calculated. I don’t want to come out and just start that hard. That’s designed that way for a reason so that at least, the people that walk out will have laughed just the first half hour. That the first half hour is at least palatable. They got some of their money’s worth.

You get on the internet, you read the news, and people swap stories and it becomes part of your consciousness and your day to day and your week to week and your year to year. If I’m not working, I don’t feel this compulsion. In other words, if I’m not onstage I don’t feel this compulsion to go out and talk about the thing that happened yesterday that Trump did. But if I’m on stage, virtually every single night, and I’m riffing about it, and there’s a new thing then that becomes part of the set because that’s sort of what I do.

Right. The tour is called “Making America Great Again” so obviously you had politics in mind when you came onstage.

Well, that was a mistake. I shouldn’t have … That was kind of a tossed-off idea I had. I came up with the name back in November or whenever it was; I had to start marketing it. And the booking agent was on my ass to come up with a name, and everything I thought of was stupid or silly or pretentious. And then I just thought of that because I was like “Hey, I need something right now.” I looked over and saw Trump was on the news and I was like, “Oh, let’s call it that.”

But it does make it seem like I’m gonna go out and do an hour of political comedy, which I don’t, nor would I, nor would I even attend an hour of political comedy because that sounds awful to me. I kind of fucked up because it does (understandably) give that impression.

The political comedy is so good, but you say that an hour of political comedy would be pretty dreadful. Is it too serious, or is it that you’d alienate your audience? What’s the risk of it?

It just gets boring, to me. I feel that way about any kind of, and I always have, about a specific topical comedy like, “an evening of Jewish comedy,” “an evening of feminist comedy” “an evening of gay comedy.” I don’t give a shit, I don’t want to … Fuck that. I don’t mind like, 20 minutes sprinkled in, but I’ve never understood the appeal of that kind of tribal thing.

Since you’re kind of talking about it: Some comedians have talked about comedy being limited by political correctness, and even though your politics are more or less on the left, you’ve complained about political correctness, too. Is it a real problem for people like you? Or anybody?

It’s a problem but that’s relative. It’s not like anybody is preventing me from doing what I’m doing, but I had plenty of people that walked out that were upset at some of the things I said. I’m talking about people on the left, über-left, über-PC, social justice warriors.

I wouldn’t say it is as big of a problem for me with people on the left as the right, but you know, it’s probably like 65-35. I’d say 35 percent of the people get pissed off. It’s interesting, when people have such completely opposite, polar opposite views, I can bring them together with my material and that’s a nice thought — that I can be responsible for bringing angry, white, feminist trust-fund kids together with angry, white, lower middle-class high school-educated workers. And through their hatred of me, [they] bond. So there is some good coming out of it. I’m uniting people through their distaste of me.

You’re providing a public service, it sounds like.

I think for nearly all of the major comedians who have shaped the field, whether it’s Richard Pryor or Lenny Bruce, shock and discomfort have been important. Do you think of them as an important part of what you do?

Absolutely. I would say, certainly an important part of shaping who I am and what path I’ve taken through this life. I mean, I got turned onto Lenny Bruce by my mom, when I was, shit, I don’t know, fifteen? And I devoured all that stuff. I don’t think he’s particularly funny, but he’s certainly important. I got into comedy early on, like a lot of people do, and I was this weirdo alien kid in Roswell, Georgia, in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, I did not fit in in any way — physically, mentally. When you find these people, and you hear these things they’re saying, it’s really important. And so it really was very important in my development and who I ultimately became and am becoming.

You talk about some sensitive stuff in the series, like kids killed by gun violence. Are there lines you won’t cross, things that you think would be funny but are just too unpleasant and too shocking even for you and your audience?

I feel like the only thing that I won’t do, or I need to try to be sensitive to, is if there is a specific innocent person that is the butt of a joke. I try to stay away from that. Somebody that has nothing to with their circumstance that is being exploited by other people, I try not to jump on that. There’s also — I’ll do this on stage, but I’ll cut it out of the special, any kind of recording — stuff about my family. I have made fun of certain people, members of my family, in a light way, never harsh, but when it comes time to broadcasting that stuff, I get rid of that. It’s really about individuals. There is no theme I’ve yet to find that I can’t apply comedy to.

If a celebrity has been accused of rape, and people make jokes about whoever the fuck it is, and then there’s a big kind of dogpile on jokes about the victim and also the perpetrator, I won’t joke about the victim at all, because that’s a real person.

Let’s talk about Mr. Trump for a minute. You talk about Trump events being like white power rallies without the guilt. Besides the racism, what seems to be the appeal of somebody like that?

I don’t think … it’s not simply racism. He appeals to a large segment of America that feels underserved, feels weakened, feels powerless, and there is something to say to the fact that the Republican establishment or the Democratic establishment, every two years, and then especially every four years, comes with a bunch of kind of patronizing bullshit that a lot of people just have gotten sick of, and don’t believe, and see the fraudulent-ness and duplicitousness and disingenuousness of every person asking for their vote.

And they get to a point where they can’t ignore it. Trump has blatantly, and immediately — ill-suited as he is to be president of anything except for maybe the Donald Trump fan club — appealed to the sense of “Yeah, fuck that!” I don’t think there’s much thought given to it. Anybody who does, any two people, like, jumping ship now, are going: Now wait a minute, let’s think about this in real terms — what happens, not 100 days in, but what happens 502 days into a Trump presidency? And that’s pretty scary if you think about it, and everything that he’s demonstrated, but those people don’t think about that. I think the appeal for so many people is “Fuck yeah! Fuck them! Fuck them! I ain’t getting mine, you ain’t getting yours.”

He just taps into the frustration that is not otherwise being addressed at all.

And that whole thing about, “He’s telling it like it is,” there’s truth to that. We know that he’s lying constantly, every third thing that comes out of his mouth is a lie, it’s made up, but it’s what they’re weaned on — Fox News does the same thing. They don’t apologize, there’s never any contrition, or they don’t correct the record when they’re constantly putting out either exaggerated shit or lies by omission or whatever it is. He’s just doing that, he’s doing that thing that everyone does now and you’re allowed to do. I couldn’t keep my job if I lied as many times as Bill O’Reilly or Sean Hannity. Most people couldn’t keep their job.

One more on Trump: Did it start out kind of funny for you? It was like a great gift for comedians.

This tour started out at the end of January, and there were 12 people still, in the race. Thirteen? I think only a couple had dropped out at that point. When this tour started it was January and then, even when I taped the special, there were still Cruz and Kasich, I think Rubio just dropped out, maybe, like, a week before, but there was no guarantee. And when I finished up the tour, he was the nominee. He had given the speech at the RNC where he basically described America as the plotline to “The Purge,” it was crazy. So yeah, it was very much a dismissable joke in the beginning when I started this thing.

I was in London for Brexit, and that was about as sobering a moment as I have had in 10 years. I’m not exaggerating, the whole place was like the fucking “Walking Dead” after that. The next day it was people in shock. I was in Leeds for the vote but London for the aftermath, where 95 percent of the people voted to remain and most of their countrymen far, far away had voted to leave and were successful and that made the Trump thing — all of the sudden the comedy drained out of it.

Finally, you’ve expressed the frustration that a lot of people have about Hillary Clinton; what bugs you about her?

I didn’t like her back in 2008, I was campaigning against her. I find her as disingenuous as anybody who’s been in politics. I think she does things that are politically expedient for her, she has a record I can point to.

This isn’t hypothetical at all; I can point to her voting record. I can see how she came into New York and just sort of pushed her way into a Senate seat in a state she has nothing to do with, and I would imagine there was a whole quid pro quo with Obama and that’s how she became Secretary of State and that was probably understood that she was going to do that for one term, burnish her credentials. And I don’t think she’d be a bad president, I really don’t. I mean, I don’t think she’d be good.

I was a Bernie supporter: In my lifetime I haven’t seen somebody get that close who was close to my ideals on social issues and everything else. And that was very exciting. My wife [actress and author Amber Tamblyn] is a staunch Hillary supporter [and] has been going back to 2008, campaigned for her this time and last time, and we disagree pretty vehemently and it was a source of tension, quite a bit. I just don’t believe [Clinton]. I don’t think she’s devious and evil. I think she’s pretty much as duplicitous as everyone else.

I don’t hold a lot of [politicians] in high esteem. In a relative sense, if it’s Hillary and the other Republican nominees, then it’s Hillary. I’m gonna vote for Hillary Clinton. But I would have preferred Bernie Sanders by a wide margin, and we’ll see what happens. I’ve got a lot of gay friends and family members and black friends and Muslim friends and I know a number of friends who have just recently had children, and if for no other reason, I will vote for Hillary Clinton for them. The Bernie or Bust, Jill Stein people… go ahead. It’s your vote. But if you really do care about gay people, people of color, the people who aren’t necessarily Christian, women, women’s reproductive rights, children or people, then you might want to reconsider.

Julian Assange to Bill Maher: Wikileaks “working on” hacking Donald Trump’s tax returns

“Real Time” host Bill Maher on Friday night interviewed Wikileaks editor-in-chief Julian Assange, who defended his website’s decision to release thousands of DNC emails — leading to the resignation of Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz.

Asked if it was “fair game” to release donor info from a private entity, Assange said, “It was definitely good fun.”

“I am super happy with how that’s gone,” he continued. “That shows a kind of instant accountability — perhaps not proper political accountability — for a really quite concerted effort, through the chain of command at the DNC, to make sure that Bernie Sanders didn’t win, including by pumping out black PR.”

Maher appeared ultimately concerned with bi-partisan hacking, wanting to know, “Why haven’t we seen anything hacked from the Trump campaign?”

“Obviously we know these came from Russia,” Maher added. “And we also know that you do not like Hillary Clinton at all, as does not Vladimir Putin. So it looks like you are working with a bad actor, Russia, to put your thumb on the scale and basically fuck with the one person who stands in the way of us being ruled by Donald Trump.”

“Why don’t you hack Donald Trump’s tax returns?” Maher asked.

“We’re working on it,” Assange assured.

Watch below:

Trump’s suicide mission: He’s not trying to destroy his own campaign — the destructive urge he represents is much bigger than that

Donald Trump; Rubble. (Credit: AP/Rick Wilking/nouskrabs via Shutterstock/Salon)

Amid the unfolding national catastrophe of the Donald Trump campaign, we are once again hearing the theory that Trump doesn’t really want to win the election, or to be president. In defiance of all real-world evidence about Trump’s aspirations and intentions, journalists keep on speculating that he picked a fight with Khizr and Ghazala Khan, the parents of a United States Army captain killed in Afghanistan, in a last-ditch effort to do something so universally offensive as to destroy his candidacy. (All previous efforts having accomplished precisely the opposite.) Barely two weeks after the final collapse of backroom plots to nominate someone else at the Republican convention in Cleveland, we’re told that GOP power brokers are now holding secret meetings about how to nominate someone else if Trump withdraws from the race.

Any such scenario would be entirely without precedent, but what else is new? There has been nothing like the Trump campaign before, not in American political history and perhaps not in history, period, which means that everything that happens is unexplored territory. But all such Trump-truther theories are overly focused on the individual psychology of Donald Trump, which to my mind is an impenetrable and deeply uninteresting phenomenon. There is almost literally no there there; Trump has a public persona but not much of a personality. These theories fail to observe the observable, in Joan Didion’s phrase. They fail to perceive the bigger picture, meaning the contemporary American disorder of which Trump is just one especially gruesome and spectacular manifestation.

Donald Trump is behaving very much like a megalomaniacal billionaire with no qualifications who wants to be president, or at least wants to be elected president. (This might seem to be splitting hairs, but those aren’t the same thing.) The important questions are more about why he’s doing such a nonsensical thing, and why he has been so successful, than about whether he has some unconscious or unspoken desire not to succeed.

I spent the week after the Republican and Democratic conventions on a personal visit to Florida, which as usual will be the crucial battleground state in this election. After experiencing the bizarre strip-mall isolation of the Gulf Coast in August, with the airwaves already blanketed with ads for Trump and Hillary Clinton, and weather so unbearable that no one ventures outside if they can help it, I’m inclined to think that the inexplicable emergence of Trump tells us less about him than about the country that produced him. As I see it, Trump is on a suicide mission, acting out a deep-seated national desire for self-destruction that runs alongside America’s more optimistic self-image and interacts with it in unpredictable ways.

Trump traffics in pseudo-uplifting nostrums about making America great again and how much “we” will “win” once he is president. But he has never offered any specific ideas or policy proposals, only incoherent fantasies that combine isolationism, protectionism, a police state and total war against amorphous enemies. I have never believed that even his most passionate supporters take his proposals about the zillion-dollar border wall, the deportation of all undocumented immigrants or the exclusion of all Muslims at face value. Those things represent a yearning toward the imaginary and the impossible, and a nihilistic rejection of all reality. No candidate who proposes such things — or who asks why we can’t use nuclear weapons, since we have them — is actually selling hope or optimism.

Donald Trump’s suicide mission is not personal, first of all. If I had to guess, I would say that he wants to be president but doesn’t know why, and has no idea what he would do with the office if he wins. Trump wishes only for his own glorification; he isn’t intelligent enough or complicated enough to yearn for his own destruction. Whether that translates in practice to a desire to lose the election, with the side benefit of endangering democracy by claiming that the system is corrupt and the results were rigged — well, that sounds like a pretty good guess, but as I said earlier I don’t know and I don’t really care. Trump’s suicide mission is ultimately about something much larger than his own presidential campaign, and also much larger than demographic clichés about the declining white majority.

America is experiencing a health crisis on an enormous scale — a crisis that is simultaneously physical, psychological and spiritual and is hardly ever understood in holistic terms. If Trump is the most prominent symptom of this systemic disorder at the moment, he is not its cause or even its leading indicator. For starters, this crisis encompasses epidemic rates of obesity and epidemic rates of suicide, dramatic evidence of a wealthy country that is literally killing itself. It’s about a nation of worsening social isolation and individualized info-bubbles and pathological delusion, a nation that spends more per capita on healthcare than any other major Western power to achieve worse outcomes, and where Baconator Fries are $1.99 at Wendy’s.

More than one-third of American adults are obese, and close to 70 percent are overweight. Rates of obesity and associated ailments are highest among Americans with lower incomes and less education. That correlates strongly with support for the candidate who famously proclaimed, “I love the less educated,” at least among people who are white. There’s no way to ignore the racial element in this year of racial discord, division and discussion: African-Americans and Latinos are more likely to have obesity-related illnesses than whites, and far less likely to be Trump voters. As I say, Trump is an important signifier of our national pathology, but not its sole representative.

For all our understandable horror at mass shootings, police shootings and gang-related violence, most gun deaths in the United States are suicides. In 2014, there were more than twice as many gun suicides in as gun homicides. Suicide rates have reached their highest level in nearly 30 years, while murder rates remain near historic lows. Although suicide, like obesity, has increased across all socioeconomic and gender-ethnic categories, about 70 percent of the Americans who kill themselves are white men. Middle-aged white men with lower incomes are at particular risk — the group most likely to support Trump, and to express the incoherent racial and societal grievances he has channeled so expertly. (For reasons that are not entirely clear, blacks and Latinos are much less likely than whites to commit suicide.)

Some researchers have identified a troubling spike in preventable and more or less self-inflicted death among lower-income white people in America, the group that provides nearly all Trump’s support. This phenomenon includes suicide, alcohol poisoning, liver disease and drug overdoses, closely related to the waves of prescription-drug abuse and heroin addiction now visible in virtually every suburban or exurban community across North America.

But I’m not making a social-science case, based on statistical evidence, in arguing that there’s a connection between those physical and mental health crises and the political eruption signified by Donald Trump. I’m suggesting that the deductive or imaginative leap from one to the other is not all that far. I’m saying that the precarious mental state and multiple ailments of downscale white America have found a symbolic outlet in Trump, who offers imaginary remedies to real problems, vainglorious bluster masquerading as thought and hateful nihilism pretending to be hope.

I’m saying that the state of borderline psychosis produced by electronic consumer society leads to OxyContin addiction and Baconator Fries and a suicide epidemic and Donald Trump. Those things are not all the same, but they are interconnected. I’m saying that the landscape I just saw in west central Florida, whose inhabitants crawl mollusk-like from fast-food outlets to convenience stores to healthcare providers to office parks, in their SUVs and pickup trucks with tinted windows, is a landscape of cognitive dissonance and collective delusion. It’s the landscape of madness in general, and the flavor of madness provided by Donald Trump in particular.

We’ve been made acutely aware over the last several years that the fragmented and narrow-casted media landscape produces competing narratives of reality. Fox News viewers believe that Muslims, feminists and gays have joined forces to abolish the Constitution and institute Sharia law; MSNBC viewers believe a cabal of hateful bigots and the super-rich are conspiring to roll back all social reforms since roughly World War I. But the physical landscape of America, with its intense isolation and intense socioeconomic and racial segregation, creates competing realities as well. Donald Trump is not all that important in himself; he’s a fantasy projection created and nurtured by the lonely, frustrated and struggling white folks of Pasco County and Hernando County and places like them across the country.

One reason I felt alienated by the upbeat hyper-patriotism that led into Hillary Clinton’s speech on the last night of the Democratic National Convention was its blithe denial that anything is fundamentally wrong in America. There are small-minded bigots and there is Donald Trump and there is that other political party, the one he somehow caused to collapse like a papier-mâché castle left outside in the rain. Those things have somehow amounted to a threat to democracy, and all that is good and true in America. But the reasons why that might have happened were left unsaid and unexplored, beyond a few ambiguous phrases about people left behind by an improving economy.

No doubt the Democrats presented a much more inclusive and dynamic vision of America at their convention than the Trumpified Republicans did at theirs, and no doubt it’s better for my children and yours if Hillary Clinton wins the election. But Democratic cluelessness troubles me greatly. I’m not sure the Clinton-Obama-Clinton leadership of the Democratic Party has the slightest understanding of the physical and psychological dislocation of so much of America, the loneliness and desperation that has found its voice, for the moment, in Donald Trump. Why would they, since they are every bit as complicit in the political economy that made all this possible as the Republicans are?

Donald Trump is not the problem with America, and Donald Trump is not consciously trying to sabotage his own campaign. Maybe we should be grateful to Trump for what he has shown us. He is no more (or less) than the demonic personification of the central conflict in America, a nation torn by endless self-glorification, an insatiable hunger for Baconator Fries and the urge to put a bullet in its own head.

Sixty years and nothing to show: The slow decay of American politics since Eisenhower, Stevenson

FILE - In this May 12, 1960, file photo, President Dwight Eisenhower, front right, shakes hands with Rep. Arch Moore, of West Virginia, as he poses with a group of Republican congressmen after breakfast at the White House, in Washington. Moore, whose guilty pleas to federal corruption charges overshadowed his record as his era's most successful Republican in Democrat-dominated West Virginia, died Wednesday, Jan. 7, 2015. He was 91. (AP Photo/Bill Allen, File) (Credit: AP)

This piece originally appeared on TomDispatch.

My earliest recollection of national politics dates back exactly 60 years to the moment, in the summer of 1956, when I watched the political conventions in the company of that wondrous new addition to our family, television. My parents were supporting President Dwight D. Eisenhower for a second term and that was good enough for me. Even as a youngster, I sensed that Ike, the former supreme commander of allied forces in Europe in World War II, was someone of real stature. In a troubled time, he exuded authority and self-confidence. By comparison, Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson came across as vaguely suspect. Next to the five-star incumbent, he seemed soft, even foppish, and therefore not up to the job. So at least it appeared to a nine-year-old living in Chicagoland.

Of the seamy underside of politics I knew nothing, of course. On the surface, all seemed reassuring. As if by divine mandate, two parties vied for power. The views they represented defined the allowable range of opinion. The outcome of any election expressed the collective will of the people and was to be accepted as such. That I was growing up in the best democracy the world had ever known — its very existence a daily rebuke to the enemies of freedom — was beyond question.

Naive? Embarrassingly so. Yet how I wish that Election Day in November 2016 might present Americans with something even loosely approximating the alternatives available to them in November 1956. Oh, to choose once more between an Ike and an Adlai.

Don’t for a second think that this is about nostalgia. Today, Stevenson doesn’t qualify for anyone’s list of Great Americans. If remembered at all, it’s for his sterling performance as President John F. Kennedy’s U.N. ambassador during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Interrogating his Soviet counterpart with cameras rolling, Stevenson barked that he was prepared to wait “until hell freezes over” to get his questions answered about Soviet military activities in Cuba. When the chips were down, Adlai proved anything but soft. Yet in aspiring to the highest office in the land, he had come up well short. In 1952, he came nowhere close to winning and in 1956 he proved no more successful. Stevenson was to the Democratic Party what Thomas Dewey had been to the Republicans: a luckless two-time loser.

As for Eisenhower, although there is much in his presidency to admire, his errors of omission and commission were legion. During his two terms, from Guatemala to Iran, the CIA overthrew governments, plotted assassinations and embraced unsavory right-wing dictators — in effect, planting a series of IEDs destined eventually to blow up in the face of Ike’s various successors. Meanwhile, binging on nuclear weapons, the Pentagon accumulated an arsenal far beyond what even Eisenhower as commander-in-chief considered prudent or necessary.

In addition, during his tenure in office, the military-industrial complex became a rapacious juggernaut, an entity unto itself as Ike himself belatedly acknowledged. By no means least of all, Eisenhower fecklessly committed the United States to an ill-fated project of nation-building in a country that just about no American had heard of at the time: South Vietnam. Ike did give the nation eight years of relative peace and prosperity, but at a high price — most of the bills coming due long after he left office.

The pathology of American politics

And yet, and yet…

To contrast the virtues and shortcomings of Stevenson and Eisenhower with those of Hillary Rodham Clinton and Donald Trump is both instructive and profoundly depressing. Comparing the adversaries of 1956 with their 2016 counterparts reveals with startling clarity what the decades-long decay of American politics has wrought.

In 1956, each of the major political parties nominated a grown-up for the highest office in the land. In 2016, only one has.

In 1956, both parties nominated likeable individuals who conveyed a basic sense of trustworthiness. In 2016, neither party has done so.

In 1956, Americans could count on the election to render a definitive verdict, the vote count affirming the legitimacy of the system itself and allowing the business of governance to resume. In 2016, that is unlikely to be the case. Whether Trump or Clinton ultimately prevails, large numbers of Americans will view the result as further proof of “rigged” and irredeemably corrupt political arrangements. Rather than inducing some semblance of reconciliation, the outcome is likely to deepen divisions.

How in the name of all that is holy did we get into such a mess?

How did the party of Eisenhower, an architect of victory in World War II, choose as its nominee a narcissistic TV celebrity who, with each successive Tweet and verbal outburst, offers further evidence that he is totally unequipped for high office? Yes, the establishment media are ganging up on Trump, blatantly displaying the sort of bias normally kept at least nominally under wraps. Yet never have such expressions of journalistic hostility toward a particular candidate been more justified. Trump is a bozo of such monumental proportions as to tax the abilities of our most talented satirists. Were he alive today, Mark Twain at his most scathing would be hard-pressed to do justice to The Donald’s blowhard pomposity.

Similarly, how did the party of Adlai Stevenson, but also of Stevenson’s hero Franklin Roosevelt, select as its candidate someone so widely disliked and mistrusted even by many of her fellow Democrats? True, antipathy directed toward Hillary Clinton draws some of its energy from incorrigible sexists along with the “vast right wing conspiracy” whose members thoroughly loathe both Clintons. Yet the antipathy is not without basis in fact.

Even by Washington standards, Secretary Clinton exudes a striking sense of entitlement combined with a nearly complete absence of accountability. She shrugs off her misguided vote in support of invading Iraq back in 2003, while serving as senator from New York. She neither explains nor apologizes for pressing to depose Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, her most notable “accomplishment” as secretary of state. “We came, we saw, he died,” she bragged back then, somewhat prematurely given that Libya has since fallen into anarchy and become a haven for ISIS.

She clings to the demonstrably false claim that her use of a private server for State Department business compromised no classified information. Now opposed to the Trans Pacific Partnership (TTP) that she once described as the “gold standard in trade agreements,” Clinton rejects charges of political opportunism. That her change of heart occurred when attacking the TPP was helping Bernie Sanders win one Democratic primary after another is merely coincidental. Oh, and the big money accepted from banks and Wall Street as well as the tech sector for minimal work and the bigger money still from leading figures in the Israel lobby? Rest assured that her acceptance of such largesse won’t reduce by one iota her support for “working class families” or her commitment to a just peace settlement in the Middle East.

Let me be clear: none of these offer the slightest reason to vote for Donald Trump. Yet together they make the point that Hillary Clinton is a deeply flawed candidate, notably so in matters related to national security. Clinton is surely correct that allowing Trump to make decisions related to war and peace would be the height of folly. Yet her record in that regard does not exactly inspire confidence.

When it comes to foreign policy, Trump’s preference for off-the-cuff utterances finds him committing astonishing gaffes with metronomic regularity. Spontaneity serves chiefly to expose his staggering ignorance.

By comparison, the carefully scripted Clinton commits few missteps, as she recites with practiced ease the pabulum that passes for right thinking in establishment circles. But fluency does not necessarily connote soundness. Clinton, after all, adheres resolutely to the highly militarized “Washington playbook” that President Obama himself has disparaged — a faith-based belief in American global primacy to be pursued regardless of how the world may be changing and heedless of costs.

On the latter point, note that Clinton’s acceptance speech in Philadelphia included not a single mention of Afghanistan. By Election Day, the war there will have passed its 15th anniversary. One might think that a prospective commander-in-chief would have something to say about the longest conflict in American history, one that continues with no end in sight. Yet, with the Washington playbook offering few answers, Mrs. Clinton chooses to remain silent on the subject.

So while a Trump presidency holds the prospect of the United States driving off a cliff, a Clinton presidency promises to be the equivalent of banging one’s head against a brick wall without evident effect, wondering all the while why it hurts so much.

Pseudo-politics for an Ersatz era

But let’s not just blame the candidates. Trump and Clinton are also the product of circumstances that neither created. As candidates, they are merely exploiting a situation — one relying on intuition and vast stores of brashness, the other putting to work skills gained during a life spent studying how to acquire and employ power. The success both have achieved in securing the nominations of their parties is evidence of far more fundamental forces at work.

In the pairing of Trump and Clinton, we confront symptoms of something pathological. Unless Americans identify the sources of this disease, it will inevitably worsen, with dire consequences in the realm of national security. After all, back in Eisenhower’s day, the IEDs planted thanks to reckless presidential decisions tended to blow up only years — or even decades — later. For example, between the 1953 U.S.-engineered coup that restored the Shah to his throne and the 1979 revolution that converted Iran overnight from ally to adversary, more than a quarter of a century elapsed. In our own day, however, detonation occurs so much more quickly — witness the almost instantaneous and explosively unhappy consequences of Washington’s post-9/11 military interventions in the Greater Middle East.

So here’s a matter worth pondering: How is it that all the months of intensive fundraising, the debates and speeches, the caucuses and primaries, the avalanche of TV ads and annoying robocalls have produced two presidential candidates who tend to elicit from a surprisingly large number of rank-and-file citizens disdain, indifference or at best hold-your-nose-and-pull-the-lever acquiescence?

Here, then, is a preliminary diagnosis of three of the factors contributing to the erosion of American politics, offered from the conviction that, for Americans to have better choices next time around, fundamental change must occur — and soon.