Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 673

September 2, 2016

The “Mexico sends them” myth: Trump’s not just racist but channeling far-right immigration conspiracies

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/David Becker)

Everyone knows that Donald Trump has called Mexican immigrants “rapists” and criminals. But what he actually articulated in his infamous June 2015 announcement speech was not just standard racism but a profoundly bizarre conspiracy theory with roots in the far-right white nationalist anti-immigrant movement.

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

His theory: “The Mexican Government is forcing their most unwanted people into the United States.”

The idea is not that Mexicans are all rapists, but that the Mexican government is intentionally selecting their social refuse and offloading them on the United States. It might not be as offensive as his calling immigrants rapists but it’s an important window into how Trump thinks. This aspect of Trump’s theory on why immigrants come, however, is often overshadowed by his scathing characterization of who immigrants are.

But the notion that the Mexican government is sending immigrants here is part and parcel of a conspiracist framework that shapes Trump’s entire worldview and approach to governance: dull-witted American leaders, he repeatedly intones, are being duped and outwitted by foreigners. A Trump presidency will school those leaders in the art of the deal.

“Our leaders are stupid, our politicians are stupid, and the Mexican government is much smarter, much sharper, much more cunning, and they send the bad ones over because they don’t want to pay for them, they don’t want to take care of them,” Trump said in the first Republican primary debate in August 2015. “Why should they, when the stupid leaders of the United States will do it for them? And that’s what’s happening, whether you like it or not.”

In fact, the notion that the Mexican government is orchestrating an invasion of the United States has been a staple on the white nationalist far right for years.

“This is a longstanding conspiracy on the radical right,” said Mark Potok, a senior fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center. “There have been claims for the better part of ten years now that Mexico is secretly planning to reconquer the American Southwest.”

That conspiracy to take over the Southwest goes by the names Plan de Aztlán (taken from a 1969 Chicano movement manifesto) and “the Reconquista,” or Reconquest. One theory is that it will happen through the “birth canal,” meaning that Mexican women are being sent to the United States to give birth to lots of children and take power through sheer demographic force. The other is that it will take place through force of arms. The Federation for American Immigration Reform, one of the most extreme but influential anti-immigrant organizations, has lent its support to the theory.

“It boils down to the claim that Mexico is consciously infiltrating its citizens into the United States in order to take back the lands lost to the Americans,” said Potok.

A 2006 article in FrontPage Magazine, for example, described “the Mexican invasion of the United States” as “a campaign to occupy and gain power over our country — a project encouraged, abetted, and organized by the Mexican state and supported by the leading elements of Mexican society.”

In 2005, anti-immigrant advocates seized on the Mexican government’s distribution of a safety guide to migrants as evidence that the government was coordinating their outmigration for the economic purpose of ensuring remittances. Rick Oltman of FAIR reportedly said the books were evidence of “the Mexican government trying to protect its most valuable export, which is illegal migrants.”

The theory probably originated, said Potok, in a small group called American Patrol, based in Southern Arizona, and was popular amongst Minutemen anti-immigrant militiamen during their heyday, from the mid to late 2000s.

“It’s a conspiracy theory that began on a tiny hate group on the Arizona that has spread far and wide and quite deeply penetrated the mainstream,” said Potok.

In 2014, a video circulated of a man who described himself as a former Border Patrol agent, who charged that the influx of refugee children was an act of “asymmetrical warfare” carried out by unnamed malignant forces so that they could sneak in drugs and chemical and biological weapons (he also put suggested that the Ebola outbreak in Africa was spread by intentional conspiracy). The video was cited by right-wing figures including former Congressman Allen West.

Others, including former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, accused the U.S. government of being complicit in coordinating the wave of Central American child refugees. That taps into the notion, said Potok, that President Obama wants immigrants and refugees to come to the United States because they will be future Democratic voters. It’s also part of a broader theory that dangerous forces abroad are allied with an internal fifth column of liberals who are aiding the enemy for their own nefarious purposes.

These sorts of conspiracies are not limited to immigration: the far right that has taken over the Republican Party incorporates a whole range of extreme theories rooted in the Cold War paranoia of the John Birch Society (which believed that the civil rights movement was a communist plot and more recently mainstreamed the notion that the United Nations was scheming to destroy the American way of life in the name of environmentalism) and the rantings of Alex Jones and his Infowars empire.

Trump makes a similar but even more sinister argument when he suggests that President Obama is resettling Syrian refugees because he is being fooled by a conspiracy to attack America or may be complicit in it. “Why is he so emphatic on not solving the problem?” Trump asked. “There’s something we don’t know about. There’s something we don’t know about.”

Trump’s position on free trade likewise reflects this worldview. While he does argue that global trade is organized to advantage elites at the expense of workers—echoing criticisms that are also common on the left—the centerpiece of his plan for trade is to “appoint the toughest and smartest trade negotiators to fight on behalf of American workers.”

American leaders have simply been crappy negotiators, he contends. And he will be a much, much better one.

“The most important component of our China policy is leadership and strength at the negotiating table,” according to his website.

There are (to oversimplify matters) two basic radical critiques of the way the world works. One is left-wing and systematic. It takes account of various roles played by different classes and groupings in large economic and political processes. Trump subscribes to the other framework, a form of conspiracist thinking long popular on the far right: contemporary economic problems are created by small cliques in smoky rooms rather than by the fact that labor’s bargaining power against business has been undercut across the board.

This worldview offers another possible explanation as to why Trump went to Mexico to meet with President Enrique Peña Nieto on Wednesday. It was an opportunity not only for Trump to look presidential but also to present himself as the savvy negotiator that is at the core of his personal brand. Perhaps he not only asked Peña to build the wall, but to stop sending his people here as well.

The reality, of course, is that Mexico doesn’t decide which immigrants come to the United States; immigrants experiencing complex social and economic realities do. But conspiratorial explanations become increasingly appealing as the global forces that shape people’s lives become ever more abstract. Trump isn’t just tapping into racist sentiment. He’s channeling a right-wing account of how the world works that is no longer relegated to the fringe.

September 1, 2016

BREAKING: “I have found and befriended a lower-middle class white family”: The Greatest Living American Writer

(Credit: Shutterstock/Salon)

In the many uninterrupted decades that I’ve claimed the title of The Greatest Living American Writer, I’ve endlessly fought for social change via literary nonfiction. No one can forget my epic study of 1970s ghetto life, “Leon: A Man of the Streets,” which caused Cornel West to call me a “righteous brother of the revolution.” I wrote the groundbreaking trilogy about the early days of the gay rights movement, “Just Before Stonewall,” “During Stonewall” and “Slightly After Stonewall, and the Pulitzer-sweeping 1983 book on living with Southeast Asian refugees, “Among The Hmong.” As the beautiful Isabel Allende once said to me as we made love in a hammock at our Uruguayan costal retreat, “No one understands the forgotten like you do.”

That said, there remains one group that, until now, I have neglected: lower-middle-class white people, the people’s people, the first people. They have been abandoned by modernity, swept away by an economic reality that doesn’t care about them or their children or anything else, for that matter. They rot in their moldy hovels while we sip Kir Royale cocktails and laugh. It isn’t right.

I vowed to correct this grievous, gaping wound in the corpus of American journalism, and to do a better job chronicling them than pretenders like George Saunders, Dave Eggers and everyone else who purports to write an elegy for America’s hillbillies. Who, I’ve often wondered, will smell the people? The answer is me, and only me.

To prepare for my journey into real America, I drove a camouflaged truck through 6-inch-deep mud. I wore an anti-Hillary muscle shirt that read “This Bitch Don’t Hunt.” I shot a kerosene-filled barbecue smoker with an assault rifle and arm wrestled a Iraq War veteran forklift operator while eating a fried pork chop. Only then was I ready to meet a real lower-middle-class white American family.

My subjects are the Golicksons, Steve and Susie and their three sons, Tyler, Taylor and Tucker. They live in a wretchedly bland split-level home in a suburb of Savitt, Ohio, a small town on the border of Kentucky, but also near Indiana and maybe rural Illinois or a couple of other states. I’m not quite sure; I’d have to look at the map.

Susie toils nearly 45 hours a week, an inhuman schedule, as an assistant administrator of human resources, personnel distribution management and digital transportation systems at a health care-industry supply and management firm, which sounds heart-wrenchingly awful. Steve works in oil, coal and toxic waste. When I ask him about his job, he says, “I wouldn’t mind quitting to open an ice cream store. I’ve always wanted to do that. But who has the time?”

There is no more ice cream in Steve’s America, and there are no more stores. What will be left for Tyler, Taylor, and Tucker?

Whither America?

Whither?

Whither?

I go to the Golicksons’ house for dinner. They look at me shyly, not knowing exactly what to do with the reporter wearing a flat-brimmed “Git R Done” baseball cap. But the hat is my way of letting them know that I understand how they’ve been left behind by the American Dream’s false promise of inexpensive dentistry for all. These are people who’ve never eaten sushi that’s not from a grocery store. That is, to me, a fate unbearable.

“Hey, kids!” I say to the three boys. “Do you like guns, trucks and football? I sure do!”

As we sit down to a platter of a disgusting casserole, the conversation quickly turns to politics.

“That Trump sure does speak his mind,” Susie says. “And I like it!”

“Are you voting for Trump?” I say.

“Well, sure!” she says.

“Why the fuck would you do that?” I ask. “He hates women! Are you an idiot or something?”

“We try not to curse around our children,” Steve says. “And we try not to insult my wife.”

“Shit, sorry,” I say.

“It’s OK,” Susie says. “I just think it’s time we got somebody who’s going to make America great again.”

This comment scares, fascinates and repels me. But it makes me pause and take stock. I write, “Hmmm, very interesting” in my notebook. Is this how real Americans think?

“My daddy says that Trump is the guy who will get the blacks to know their place!” Tyler, age 9, says.

“Now now, Tyler,” says Steve. “I didn’t put it quite that way.”

“Yes you did,” Tucker, age 11, adds, helpfully. “You said that black people only know how to kill.”

“Kids mishear things,” Steve says. “I’m not racist or anything.”

“Of course not,” I say. “I understand. In these times of globalization and free trade, it can be hard for simple folk who’ve been left behind. America has broken its promises to those who need it most.”

“My daddy thinks gay people should go to jail if they get married!” says Taylor, age 8.

Already I feel a deep bond with this lower-middle-class small-town white family. We look at one another in recognition of our mutual humanity. My heart is warm and full. This, I realize, is immersive journalism at its finest.

“I admire you lower-middle-class white people so much,” I say to Steve.

“We aren’t lower middle class,” Steve says. “We’re just plain middle class.”

“Sure you are,” I say.

“We went on vacation to Hawaii two summers ago,” he says.

“You keep telling yourself that, pal,” I say.

I marvel at the strength and resilience of these true Americans. We cannot be afraid of them just because they support Donald Trump. They are just like you and like their neighbors and also, to some extent, like me. As Steve Golickson says when I leave his house for the first and final time, “Remember to write about the Mexican rapists who are coming across the border to take our jobs.”

“You bet,” I say.

He winces when I give him a man hug. As I drive away in my rented GMC Sierra Denali Acadia Wrangler “These Colors Don’t Run” Florida-Georgia Line Special Edition All Terrain 4X4, I take one last gaze at my new friends, this lower-middle-class white family. My eyes fill with tears. At last, I’ve told their story. Once again, I’ve succeeded in penetrating deep into the moist core of an American subculture. And that’s the only thing that matters.

“Dekalog”: The legendary Communist-era Polish miniseries that shaped the TV we watch today

A still from Krzysztof Kieslowski's TV series "Dekalog" (Credit: Janus Films)

Did an obscure TV miniseries made in Poland at the tail end of the Communist era — and seen in the West only by art-film devotees — pave the way for the explosion of quality TV drama that produced “The Sopranos,” “The Wire” and so many other memorable shows? No doubt about it: Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Dekalog,” a hypnotic, interlocking and often devastating series of 10 hour-long episodes set in the same Warsaw apartment complex and loosely inspired by the Ten Commandments, was something of a curiosity in the late 1980s.

The series was largely understood by American critics and elite audiences as a cinematic work that had arrived by way of the small screen for eccentric reasons: Things were different in Europe and even more different on the other side of the corroding Iron Curtain. An expanded version of “Dekalog Five,” titled “A Short Film About Killing,” won a prize at Cannes in 1988 and played as a theatrical release in Western nations, months before Kieslowski’s series even reached the air. Now a digital restoration of the entire series is opening theatrically in New York this week, with home-video release from the Criterion Collection to follow in late September.

After creating this series, Kieslowski went on to a brief career as a name-brand director of art-house films in the vein of Ingmar Bergman and Andrei Tarkovsky (to cite two obvious influences) before his untimely death in 1996, at age 54. He is best remembered in such circles today for the “Three Colors” trilogy, starring Juliette Binoche, that he made in France in the early ’90s. Those are beautiful films, but in retrospect I would argue that “Dekalog,” produced as it was under the restricted budget of Polish state TV and under the threat of official censorship, is a more important work and a better work with a much longer cultural tail.

Despite the unfamiliar Soviet-bloc setting and the distant historical epoch, these are highly accessible human stories with an enormous emotional range, from dark comedy to reckless romance to unbearable tragedy. As Kieslowski put it, “Dekalog” is an attempt to address fundamental questions that go beyond capitalism and socialism: Is there a point to human life? Why do we bother to get out of bed in the morning?

By the time Kieslowski left Poland and the Berlin Wall came down, the auteurist tradition of European art cinema — essentially a branch of high culture, closer in spirit to modernist drama than to Hollywood — was already in steep decline. It would be virtually swept into the cultural dustbin by the rise of Quentin Tarantino, the Coen brothers and other, more pop-oriented indie filmmakers. Another tradition, the prestigious HBO-style television drama, was just being born. From the perspective of 2016, that’s the genre on which “Dekalog” had its most significant impact. Along with a few other seminal influences from the same period, like Dennis Potter’s classic BBC miniseries “The Singing Detective” and David Lynch’s “Twin Peaks,” Kieslowski’s TV experiment helped mold the future.

Nothing like “Dekalog” had ever been attempted on TV before, in Poland or the United States or anywhere else, and its narrative and thematic ambition is still impressive almost 30 years later. “Dekalog” is not a miniseries in the customary sense, meaning that it doesn’t tell a single overarching story about the same set of characters. But the 10 episodes (all written by Kieslowski with his longtime collaborator Krzysztof Piesiewicz) are increasingly interdependent and interconnected, and are best understood as sequential elements of a single work, to be viewed in order.

Characters from one episode frequently appear in another, usually in bit parts or cameo roles, and it would take several viewings to catch all these interactions. An intense father-daughter conversation in “Dekalog Four” — one of the riskiest of the episodes, and one of my personal favorites — is interrupted by a fellow elevator passenger, an eminent doctor who was entrusted with far too much power over life and death in “Dekalog Two.” But the real interaction between people and episodes is more a question of the way Kieslowski’s themes — love and marriage, life and death, religious faith and religious doubt — reflect and refract each other, gradually building toward something that feels like a grand theory about human existence, created entirely from the lives of the residents in one nondescript middle-class housing development.

When it comes to the relationship between the Ten Commandments to individual episodes of “Dekalog,” sometimes it appears clear enough — as with the wrenching and brutal “Dekalog Five,” which became “A Short Film About Killing,” and “Dekalog Six,” a tale of erotic obsession similarly expanded into “A Short Film About Love.” But that’s not always the case. Kieslowski and Piesiewicz were presumably working from the Roman Catholic version of the commandments, which would be familiar to almost every Polish person. But they never exactly intended each episode to serve as a linear illustration of a particular divine edict, and their attitude toward the meaning of the Mosaic text is deliberately ambiguous.

A few minutes into “Dekalog One,” a science-obsessed boy and his father (who owns a personal computer, surely an unusual possession in 1988 Warsaw) discuss the existence of God and the human soul, which the dad describes as metaphorical notions that people use to deal with death. By the end of the episode, that topic will assume a terrible new significance, and one might well read into it the admonition, “You shall have no other gods before me.”

But “Dekalog Two,” the story of a doctor confronting the relentless and unfair demands of a patient’s wife — who has urgent personal reasons for wanting to know whether her husband will live or die — seems to be about several things but not necessarily taking the Lord’s name in vain. It’s about adultery, which is a running theme throughout “Dekalog.” It might be about bearing false witness (the eighth commandment) and coveting what other people have (the ninth and 10th). It might be about human pride and vanity and arrogance, qualities evident in both characters but not specifically mentioned in the list provided by the Almighty on Mount Sinai.

Sometimes the relevant commandment is no more than a jumping-off point, as with the marvelous, funny and sad tale of “Dekalog Three,” in which a woman invents a threadbare excuse to spend Christmas Eve with her married former lover. They visit abandoned train stations and desolate emergency rooms, file multiple false police reports and stage a car chase and knock over the Christmas tree in the local public plaza. Is that a story about the commandment to observe the Lord’s Day? OK, sure, but it’s about a lot of other things, too, and whether we think this Warsaw Bonnie and Clyde and their mini-getaway from normal life are honoring the Christmas spirit or violating, it is left up to us.

For most viewers, the dramatic heart of “Dekalog” arrives in Episodes 5 through 8, which broach the most overtly serious themes: murder and capital punishment; female sexuality and female relationships; Polish collaboration in the Nazi Holocaust. Once you get that deep, you’re hooked and are likely to binge-watch right through the dark madcap comedy of the final installment. On repeat viewings, I appreciated the supposedly lighter episodes more, and Kieslowski is always at his best in less self-conscious moments that mean more than they say — the small interludes of connection or miscommunication between lovers or strangers or parents and children.

That’s where I see the connection between this landmark of TV history and so much that came later. You can see the influence of “Dekalog” all over the place, but perhaps first and foremost in David Chase’s “Sopranos,” which brought a similar spirit of religious and existential inquiry to a different narrative universe, using the story of a New Jersey mob boss as a way to explore American family life and the decaying social contract of the 21st century. “Dekalog” was much more than a series of short movies accidentally jammed into television and more than a peculiar cultural artifact of late communism. It was the beginning of a process that set television free.

“Dekalog” is now playing at the IFC Center in New York and opens Sept. 17 at the Cinefamily in Los Angeles, with more cities to follow. Home video release will be on Sept. 27.

We’re all living in the “Upside Down”: “Stranger Things” is a show about the internet’s dark sides

Winona Ryder in "Stranger Things" (Credit: Netflix/Screen Montage by Salon)

“Stranger Things” is hotter than Kayne’s Twitter feed right now and Netflix just announced that a second season is on its way. A trailer recently posted online reveals that when 2017 arrives, fans pining for more ’80s pop culture references will be returning to Hawkins, Indiana, in the fall of 1984 as the town faces the aftermath of its first contact with the alternate universe known as “the Upside Down” and the predatory “Demogorgons” that dwell therein. [Note: Spoilers ahead.]

Right now most reviews and discussions about “Stranger Things” focus on its aesthetics: how the Duffer brothers crafted such an eloquent piece of pastiche that takes the best elements of 1980s pop culture and reassembles them into something fresh and entertaining. Of course, that’s worthy of discussion in and of itself. Who wouldn’t jump at a chance to spot a “Goonies,” “Evil Dead” or “Stand By Me” reference and gush adoringly to their friends about it? But then again, there’s a lot of TV, music and film doing the same thing these days. So it’s worth asking — especially while we wait for the next season to arrive — if there is something more to “Stranger Things” that accounts for its popularity and the mass amounts of speculation surrounding its mysterious aura. I think the answer is yes, and I think that’s worth talking about, too.

Even by the end of the first episode, one gets the sense that the Duffer brothers are more than just writers and directors who have an extensive knowledge of ’80s gold. They seem to be filmic philosophers who emerged out of the shadows with this series to deliver an intriguing commentary about a world like ours, a world rife with communication technologies that can harm us just as much as they can help us.

“Stranger Things” is set in small-town America in the 1980s. On the fringes of this town is a mysterious Department of Energy compound conducting weird experiments somehow related to the U.S. military and espionage. People are not really worried about this organization, though, until they have to start worrying about it because technology, espionage, militarism, fear, surveillance and such things were all staples of the Cold War era. (But, in fact, without the Cold War, much of the technology we have today — like the internet and personal computers — simply wouldn’t exist.)

But then all of a sudden the worst thing happens that could possibly happen to a mother, older brother and a small community. A young boy is stolen away in the night to . . . where exactly? Will Byers, like other characters both major and minor in the show — #TeamBarb! — has been kidnapped and possibly eaten by a predatory creature that his friends have dubbed the Demogorgon, after a monster in their Dungeons & Dragons game. The Demogorgon travels through numerous gates between our world and another dimension — the Upside Down — that is sort of like our world but way darker and scarier. The alternate dimension and the Demogorgon are somehow connected to electricity, wires, appliances and communication devices. Ao they all go nuts whenever the monster lurks about in the real world.

Likewise, people trapped in the Upside Down can reach the real world only through electronic devices like telephones and radios, and the bigger the device, the better the contact. We see this clearly when Will’s mom Joyce (Winona Ryder) creates a primitive codex-like thing by painting a wall with the alphabet and assigning a light to each letter, which allows her to use it as a keyboard to communicate between dimensions with her missing son. She asks questions and Will spells out answers by flashing lights above the appropriate letters. It seems like magic, but it’s just primitive computing technology.

All of this sounds like the foundations of the internet, doesn’t it? A network of electricity, phone lines, communication devices and flashing lights that work together to connect distant worlds so that disconnected people can meet and dialogue with each other. I would wager that this intriguing little detail represents a key theme in “Stranger Things.” It also explains why the show has become so popular. Just like now, the ’80s was a paradoxical time of both hope in technology and fear of it. Deep into the Cold War by 1983, both the East and West knew that technological development was both their biggest threat and their biggest hope.

The race to space known as Star Wars — Reagan’s missile defense program, not the films — and the mass ramping up of innovations in personal computing, information technologies, communication devices and consumer entertainment systems, all combined to simultaneously strike people dumb with awe and cower in fear. Sure, an atomic bomb could hit a town at any moment and a commie spy could be running a local grocery store, but at least people had some newfangled digital devices and entertainment while they waited for all that horrible stuff to go down. Meanwhile, the military would be using all this technology to gain the upper hand on the enemy.

All of this explains why the Demogorgon and the sinister Department of Energy lab are secondary issues in “Stranger Things.” The primary issue is the Upside Down, the alternate dimension that the Department of Energy accidentally discovers. If this gate had not been opened up by Eleven, a mysterious child with telepathic and kinetic gifts who is forced to go into that world and inadvertently make contact with the Demogorgon, the monster would have never shown up in Hawkins to kidnap people in the first place. So it’s the Demogorgon’s network, the world it lives in and connects to, that enables the monster to be anywhere at any time to snatch poor Will and Barb away to the Upside Down. That is the real threat to everyone in Hawkins.

Which is to say, the Upside Down starts looking very much like an analog for the internet. Yes, the internet allows people to connect everywhere at every time, but this is not always a good thing. Just look at Kayne’s Twitter feed. Or, on a more serious note, consider the devastating social-media harassment campaign that has targeted actress Leslie Jones. Or reflect on the degree to which even our most banal online activities and conversations are being watched and collected by government agencies.

This explains why there are more seasons to come because by the end of the first season, it appears that the Demogorgon is dead. But the network itself, as well as its effects, remains. Will Byers might be back in the real world to go on D&D quests with his buddies and be bullied at school, yet the network has made an impression on him that he can’t shed. Now he is a part of the Upside Down network and he’s brought it back to Hawkins. We see this when he coughs up a little Demogorgon slug in the concluding episode. The network and its demons are taking root and growing. Pikachu is in our world now and we’d better watch out.

Once you start pulling at these thematic threads, you begin to see a deeper philosophical discussion at play in “Stranger Things.” Of course, some fans love this show because it captures several of their favorite memories of the ’80s. But at the same time, and perhaps more important, we’re intrigued by the experience of watching characters in “Stranger Things” encounter the consequences of rapid technological advancement.

There’s no better example of this than the scene when Joyce Byers finally makes semi-physical contact with Will through an opaque window that appears behind the wallpaper in the Byers’ living room. For a glimmering moment Joyce is able to reach out to Will through a translucent screen to see that he’s alive. And Will reaches back. But that window evaporates as quickly as it appeared. So Joyce takes an ax to the wall to break through to the young Will trapped in the Upside Down. She chops right through the wall and finds . . . nothing — just the world outside. Will is gone. The network escapes Joyce’s grasp, her son is still kidnapped and her life is still in shambles.

It turns out that technology can’t bring Will back, only humans can. And humans eventually do. This draws out a key thesis of the show: We don’t need more or better technology to solve our greatest problems. What we need is more courageous people — like Joyce and Sheriff Hopper; Elle; Will’s friends Mike, Lucas and Dustin; Will’s brother Jonathan, Mike’s sister Nancy and (eventually) her boyfriend Steve.

It may be difficult for some younger viewers to think about what the world was like before digital technology and the internet arrived on the scene and developed into what it is and does to us today. But artistically and philosophically “Stranger Things” helps fans get to (or back to, depending on the viewers’ age) that place. And once we’re there, we’re pressed to explore ethical questions similar to those encountered by the kids and adults of Hawkins. Will we or won’t we make contact with the Upside Down and dimensions and technologies of that kind? And if we do, how will we act when things get strange, volatile and perhaps even violent?

A 10-year-old boy? An 84-year-old grandmother? Police brutality will not end in America until cops stop perceiving blacks as monsters

Legend Preston (Credit: ABC7)

I am a black man. I am an American. I am not a monster.

Like so many other black people in America, I have been followed around department stores by security guards, harassed by police, and encountered racial discrimination in the workplace. These are not minor inconveniences: to be made to feel unwelcome in one’s own country is no petty insult.

It is a reflection of a society where some groups are viewed as full and equal citizens because of their skin color and others are denied the same rights and privileges. In all, this is racism and white supremacy as quotidian life experience. It can kill a person because of the cumulative effects of stress and anxiety; it can also kill a person in a moment of punctuated violence.

Tamir Rice was 12-years-old. He was a black child. He was not a monster. The Cleveland police street executed him in less than two seconds while he played in a park with a toy gun — in a state where the “open carry” of real firearms is allowed.

Michael Brown was 18-years-old. He was a black teenager. He was not a monster. Darren Wilson, a member of the Ferguson, Missouri police department shot him at least six times. Wilson would later say about Brown that, “The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked. He comes back towards me again with his hands up.” According to Wilson, Brown could also run through bullets unharmed and had the amazing strength of Hulk Hogan. These are racist, fantastical, and bizarre comments more fit for a drug induced hallucination than sane observations that were accepted as reasonable facts in testimony to a grand jury. Nevertheless, Darren Wilson succeeded in transforming Brown into the white racist archetype of the “giant negro” and “black brute” (or its modern day equivalent “thug”).

Legend Preston is 10-years-old. He is a black child. He is not a monster. Newark police claimed that he “fit the description” of a 20-year-old adult suspect in an armed robbery. The Newark police then proceeded to point their guns in his face. Legend Preston committed no crime. He was left psychologically traumatized. No apology can repair the damage — and the Newark police have offered none. In that moment, Preston learned that black children in America are not allowed the luxury of innocence. Adultification is a feature of black life along the color line — especially when dealing with police or other representatives of the state. As researchers have demonstrated, adultification also means that white people consistently judge black children to be much older than their actual age. Once and again, the White Gaze distorts black humanity.

Geneva Smith is 84-years-old. She is a black woman. She is also a grandmother. Geneva Smith is not a monster. In the early morning hours of Aug. 7, Muskogee, Oklahoma police pursued her son into their home. Frightened by the commotion, Smith asked the police what was happening. As shown by their body cameras, the Muskogee police then proceeded to pepper-spray her in the face for refusing to comply with their orders. Geneva Smith was arrested and brought to jail. Given her age, she could have suffered serious and permanent injury, or even death, from such a powerful irritant. Fortunately, Geneva Smith survived. She is pursuing legal action against the Muskogee police. To be black, 84-years-old, and a grandmother in America is still to be a threat to the United States’ militarized police.

These are but a few recent examples of how America’s police show little restraint in how they treat black and brown people. They confront “monstrous blackness” with extreme prejudice. Consequently, black men who are unarmed are three times more likely to be shot than white men who are unarmed. Police are also faster to use lethal violence against black men than they are white men. Even when allowing for racial disparities in crime, police are also much more likely to beat, club, throw to the ground, and use other types of physical violence against black people than they are white people.

This is part of a long and ugly history that begins with the origins of modern American policing in the slave patrols of the antebellum South and continues through to the present in the form of racial profiling, “stop and frisk,” and a general culture of police thuggery and abuse towards people of color. These are not bugs or outliers but rather fixtures of the American legal system.

If blackness is perceived as something monstrous by America’s police, then whiteness is perceived as a type of innocence, an identity that is inherently benign and harmless. To that end, white people are (almost always) treated with restraint.

There are numerous examples of this type of white privilege in action. White men have committed mass shootings and been arrested unharmed; white men have shot at (and killed) police and have been arrested unharmed; white people have pointed guns at police and federal agents and have either escaped or been arrested unharmed; white people often brandish firearms in public without being arrested, harmed, or interfered with by police.

And in one of the most powerful and bizarre examples of white privilege in action, several weeks ago Austin Harrouff attacked three people in a Florida, and then proceeded to eat the face of one of his victims. The police eventually arrived while Harrouff was engaging in his cannibalistic smorgasbord. Miraculously—unlike a mentally ill black man by the name of Rudy Eugene, who in a much-publicized incident in 2012 was shot and killed by Miami police as he ate a person—Andrew Harrouff was taken into police custody unharmed.

Why is there such a difference in how America’s police treat white people as compared to people of color?

There are many reasons for this outcome. Racism is a learned behavior. America’s schools, media, and other social and political institutions reproduce and circulate social values and norms which emphasize that the lives of white people are to be valued and those of non-whites are to be devalued. Police, like other (white) Americans, have internalized these values. Moreover, the mainstream corporate news media is especially powerful in how it reinforces negative racial stereotypes: social scientists have documented how crime committed by blacks is grossly over-reported by the news media while crime by whites is under-reported.

Anti-black and brown racial animus also operates on a subconscious level as well. Social psychologists and other researchers have repeatedly documented how “implicit bias” impacts cognition, creativity, and decision-making. Racial animus and (white) anxieties about black people are so powerful that they even have the ability to distort a given (white) person’s sense of time. A recent article published by the American Psychological Association explains:

Time may appear to slow down for white Americans who feel threatened by an approaching black person, raising questions about the pervasive effects of racial bias or anxiety in the United States, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

In a series of experiments, white adults viewed faces of white and black people who appeared to be moving toward them on a computer screen. Participants rated the apparent speed or approximate time that each face was on the screen and completed a survey that measured their anxiety when around people of a different race.

White participants who reported more racial anxiety perceived the approaching black faces as moving more slowly or appearing longer on the computer screen than the white faces. Although participants saw both male and female faces, there was no difference in observed effects based on gender. The same effects weren’t found when the black faces appeared to be moving farther away, possibly because they weren’t perceived as a threat, the study noted.

The consequences are wide-ranging:

The study findings may have important practical implications, including inaccurate eyewitness identification and the misinterpretation of innocent actions by black people as threatening, Kenrick said. “If you perceive time as slowing down, then you may feel overconfident about identifying the approaching person later or interpreting their actions,” she said. “However, more research is needed to reach firm conclusions.”

That some white Americans are so anxiety fueled and fearful of their fellow citizens is a profound indictment of the country’s civic and social culture. It is white racial paranoiac thinking that on an individual level interferes with forming meaningful relationships across lines of race, and on a mass scale fuels the proto-fascism and bigotry of Donald Trump and the American right wing.

Psychologists have also shown that many white Americans view black people as somehow being supernatural, superhuman, and less sensitive to physical pain. This locates black people as somehow different and apart from the human family, thus making it far easier to identify them as some type of monstrous Other.

As I suggested in an earlier piece here at Salon, police brutality and thuggery against black people will not stop until white Americans look at children such as Tamir Rice and Legend Preston and see the faces of their own children. On the other end of the generational spectrum, police brutality and thuggery against black and brown people will not stop until white Americans can look at the face of an 84-year-old black grandmother who is being assaulted in her own home by the police and see their own honored elders and kin.

America loves it black athletes, entertainers and first black president. Unfortunately, White America all too often does not love black and brown people as individuals. It most certainly does not love the black or brown stranger. This enables a type of emotional distance that contributes to racial injustice and makes the United States a less than fully democratic and fair society. It is only when White America and its police cease to see black people as some type of monstrous Other that they will be able to finally embrace their own full humanity. Racism does not just harm black and brown people. It hurts white folks too.

Got to give it up for Robin Thicke: Siding with “Blurred Lines” feels wrong, but it’s the right thing to do

Marvin Gaye; Robin Thicke (Credit: AP/Nancy Kaye/Chris Pizzello)

If you were polling artists and fans on their feeling about a certain opposing pair of musicians — Marvin Gaye on one hand, Robin Thicke on the other — the contest would not last long. Gaye was not only one of the most brilliant musicians in the history of R&B, he made both joyful music and, especially later on, songs that addressed issues from urban poverty to the degradation of the environment to his own divorce. Thicke, by contrast, is well-known as a weasel and musical mediocrity whose career has been derivative at best.

So if the fight over “Blurred Lines” — the 2013 hit single written by Thicke alongside Pharrell Willams, featuring T.I. — had been simply about the relative talents of the musicians and the good will toward them in musical circles, this would be simple. But instead what we’re seeing is the boiling over of long-brewing frustration with the plagiarism decision that awarded the Gaye estate $5.3 million, thanks to the argument that the song stole from Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up.”

Now, more than 200 musicians have filed a brief with a circuit court in Los Angeles decrying the original decision in favor of Gaye’s heirs: R. Kelly, members of the Go-Gos and Black Crowes, composer Hans Zimmer, producer Danger Mouse, Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo, and others are arguing that the decision will stifle musical creativity.

This is from the brief:

The verdict in this case threatens to punish songwriters for creating new music that is inspired by prior works. All music shares inspiration from prior musical works, especially within a particular musical genre. By eliminating any meaningful standard for drawing the line between permissible inspiration and unlawful copying, the judgment is certain to stifle creativity and impede the creative process.

…One can only imagine what our music would have sounded like if David Bowie would have been afraid to draw from Shirley Bassie, or if the Beatles would have been afraid to draw from Chuck Berry, or if Elton John would have been afraid to draw from the Beatles, or if Elvis Presley would have been afraid to draw from his many influences.

While musical plagiarism standards exist, at least in theory, to protect musicians, this court decision has seen opposition from musicians from the beginning. Questlove from the Roots, for instance, told Vulture that he thinks “Blurred Lines” was not stolen: “It’s not the same chord progression. It’s a feeling. Because there’s a cowbell in it and a Fender Rhodes as the main instrumentation — that still doesn’t make it plagiarized. We all know it’s derivative. That’s how Pharrell works. Everything that Pharrell produces is derivative of another song — but it’s a homage.”

It’s not the same chord sequence, not the same melody, and not the same key. Most plagiarism cases — including the recent lawsuit over Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” — have turned on these elements. Others have been provoked by stolen samples, especially when bits of James Brown songs were taken by rappers. De La Soul’s masterpiece “3 Feet High and Rising” was caught in an important suit with the band the Turtles; De La Soul lost.

But what’s disturbing about the “Blurred Lines” case is the way the feel and vibe of the song caused the legal trouble. The song’s lyrics and video may be sexist, and the racial subtext of the song — what Questlove called “Elvising” — is at least moderately troubling. But if the “Blurred Lines” decision isn’t reeled in, it could create a lasting precedent in which everyone — listener and musicians alike — loses.

Leaked “Democratic Party memo” admits U.S. war in Iraq fueled rise of ISIS

(Credit: Reuters)

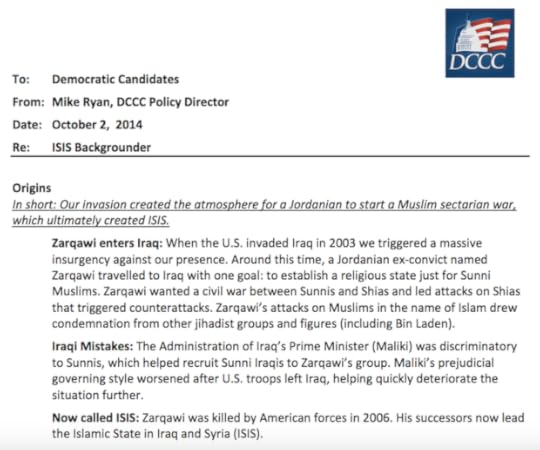

An alleged Democratic Party document leaked by a hacker acknowledges the role that U.S. foreign policy has played in fueling the rise of the genocidal extremist group ISIS.

Guccifer 2.0, the hacker (or group of hackers) that has leaked internal Democratic Party documents, published on Wednesday what it says are documents from the personal computer of Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic minority leader of the House of Representatives.

Among the documents is an October 2014 memo titled “ISIS Backgrounder” that was allegedly sent by Mike Ryan, policy director of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, or DCCC, the official arm of the Democratic Party in the House.

The alleged DCCC memo provides Democratic candidates with two pages of talking points to use when discussing the self-declared Islamic State. The document admits that the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq and the subsequent sectarian policies of the U.S.-backed Iraqi government incited extremism.

In the section on the origins of ISIS, the summary reads, “Our invasion created the atmosphere for a Jordanian to start a Muslim sectarian war, which ultimately created ISIS.”

It also says, “When the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003 we triggered a massive insurgency against our presence.” This insurgency against the U.S. invasion and occupation was exploited by extremists like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of the Sunni fascist organization al-Qaeda in Iraq.

By carrying out brutal attacks on Shia civilians in Iraq, al-Zarqawi helped transform an internal war against U.S. occupiers into a sectarian war between Sunnis and Shia.

Al-Qaeda in Iraq was formed in 2004. Just a few months after al-Zarqawi was killed in 2006, al-Qaeda in Iraq evolved into the Islamic State in Iraq, or ISI — the immediate predecessor to ISIS.

The alleged DCCC memo also notes that the U.S.-backed government of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki relied on a sectarian style of governance that only further fueled extremism.

(Part of the alleged DCCC memo on ISIS)

After Salon reached out to the DCCC to ask about the authenticity of the document, Meredith Kelly, the organization’s national press secretary, said, “We will not at any point be confirming or denying the authenticity of any documents that are released.” Kelly did, however, confirm that DCCC computers were hacked in July. She blamed Russian hackers for the cyber attack.

The Democratic Party and the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign claim that the Russian government is leaking Democratic Party documents in order to tilt the election in favor of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, although they have admitted they have no evidence. Russia denies the allegations, and the U.S. government has not officially blamed the Russian government for the hacks. The FBI is currently investigating.

The alleged DCCC memo goes on to provide background information about ISIS, its structure, its composition, its size, its recruiting tactics, its assets and the “broad array of horrific crimes against humanity” that the fascist Islamist group has committed.

ISIS “owns hundreds of millions of dollars of sophisticated weapons, including vehicles and GPS-equipped weapons,” the memo adds, acknowledging that many “of these are American-made and were captured from Iraqi troops.”

The document concludes with details about the strategy of the U.S. and other countries to defeat ISIS.

As a senator, Hillary Clinton voted for and advocated strongly on behalf of the Iraq War that President George W. Bush initiated. She joined the Bush administration in propagating baseless myths to sell the war, trying to link secular Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein to al-Qaeda, which was ruthlessly repressed by his government and had very little presence in Iraq before the U.S. invasion.

Clinton’s staunch support for the war has haunted her in this election cycle. Former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders stressed in the New Hampshire debate in February that he and Clinton “differed on the war in Iraq, which created barbaric organizations like ISIS.”

U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan explicitly said in 2004 that the U.S.-led war in Iraq was illegal. It violated the U.N. Charter as it was not sanctioned by the Security Council, he explained.

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who joined President Bush in the illegal U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, apologized in October, admitting that the war set the stage for ISIS.

“You can’t say that those of us who removed Saddam in 2003 bear no responsibility for the situation in 2015,” Blair conceded.

As Salon has previously reported, the British government’s official Iraq War inquiry, the Chilcot Report, revealed that top British intelligence officials had, for months in the lead-up to the war, repeatedly warned Prime Minister Blair that a foreign military invasion of Iraq would strengthen extremist groups like al-Qaeda.

The Chilcot Report shows that Western intelligence agencies knew Saddam Hussein did not actually pose a threat, and that the real threat, they had cautioned, were Islamist militants that would take advantage of the war.

“Between 2003 and 2009, events in Iraq had undermined regional stability, including by allowing Al Qaida space in which to operate and unsecured borders across which its members might move,” the U.K.’s Iraq War inquiry noted. It added that the American and British occupation “exacerbated” Iraq’s “deep sectarian divisions,” fueling violence and extremism.

Amy Schumer is our hero: Watch her kick out sexist heckler during performance in Sweden

At her show on Wednesday in Stockholm, Sweden, comedian Amy Schumer encountered a heckler who yelled at her to “show us your tits.”

After fellow audience members pointed out the culprit, Schumer asked him what he does for a living: “Sales.”

“How’s that workin’ out?” she responded with appropriate condescension. “Is it going well? ‘Cause we’re not buyin’ it.”

She then gave him a second chance, telling him if he interrupted her show again, “You’re gonna be yelling out, ‘Show us your tits,’ to people in the parking lot, ’cause you’re gonna get thrown out, motherfucker.”

Of course, he again yelled out and was subsequently thrown out.

Schumer on Thursday posted the video (above) to her Facebook page.

Oregon white supremacist mowed down black teenager with his Jeep

In what has seemingly become a growing pattern of racially motivated attacks, comes the report of yet another murder of a African-American by apparent white supremacists.

19 year-old Larnell Malik Bruce and a group of friends were gathered outside a 7-11 store in Gresham, a small town located near Portland, when Russell Courtier, 38, and his girlfriend Colleen Hunt, 35, pulled up in their 1991 red Jeep Wrangler shortly before midnight on August 10. Bruce, who was just a few days shy of his 20th birthday, had been charging his phone outside the convenience store when the white couple nearly twice his age exited their vehicle.

For reason still unclear, a fight quickly broke out.

As Courtier smashed Bruce’s head into the store’s front window, cracking a pane of glass, his girlfriend encouraged the beating.

“Get him, baby,” Hunt urged her boyfriend, according to police. “Get him, baby!”

Eventually, Bruce pulled out a machete and the couple retreated back to their Jeep.

What happened next can perhaps best be described as a scene from the violent Jim Crow South.

Investigators said Bruce tried to run away from the couple who began to chase him down in their car. Security camera footage shows the teen doing his best to zigzag away from the SUV. Per the Portland Mercury, Courtier and Hunt barley missed Bruce as they gunned the car toward him on the sidewalk. As he tried to cross the street, the couple’s Jeep is seen moving into oncoming traffic and hitting the teenager head-on, although the direct impact is not caught on camera.

Police, who had been called by a 7-11 employee when the fight intital broke out, arrived on the scene just moments later to find the critically injured teen with blood gushing from his head and his ears lying in the middle of the street.

Bruce died from his injuries days later.

Prison records obtained by the Portland Mercury reveal that Courtier is a longtime criminal with a notorious history as a member of a white supremacist prison gang called European Kindred (EK) who was on parole at the time of killing:

In February 2004, while still in prison, Courtier was busted for getting that logo tattooed on his calf and for having a “make-shift tattoo gun” and extra ink in his cell (see that record here). Just two months later, he brawled with a black inmate in the crowded prison yard before “a group of white inmates faced off against a group of black inmates,” records show (document).

And in 2005, while at SRCI, a letter he wrote to another EK member—intercepted by prison staff—indicated he needed backup from his gang because he was “getting run up on by redskins.” (document) That year, Courtier was also accused of throwing a piece of shit-smeared paper at a guard who was a person of color, and later threatened to “take care” of him when he got out.

In total, Courtier was accused of nearly 40 “major” prison violations between 2001 and 2013—for assaults, for joining and associating with EK members, for his prison tattoos (he was busted in 2005 for tattooing “party bone” on his penis, for instance), for having contraband in his cell, for disrespect, for not following rules (see his entire DOC discipline record here).

He hasn’t fared much better outside of prison. Courtier’s had seven felony and four misdemeanor convictions, court records show. He also has an extensive juvenile record that includes multiple assaults and burglary.

As the New York Daily News, which first brought this story to national prominence, noted, Courtier was able to skirt the law in a number of cases before his encounter with the black teenager:

In 2011, he got away with illegally shooting several rounds from his car because police performed an illegal search. The next year, he slammed a woman’s head into a windshield, but was only given probation. He had just spent two years in prison for attacking another Oregon woman with a knife, and was on parole for this crime the night he killed Larnell Bruce.

On August 18, a grand jury indicted Courtier and Hunt for murder. However, the two have not been charged with any hate crimes. Both pleaded not guilty in Bruce’s death during an August 22 court appearance, according to KGW. Their trial is scheduled to begin October 3.

Bruce’s family set up a GoFundMe page to raise funds for the cost of medical bills and his funeral expenses. A post on the page reads:

We lost our son, brother, cousin, nephew and friend to a senseless crime. He was just 19 years old and still had a full life to live.

Though this tragedy has devastated our family, Larnell has the opportunity to save many lives through the Organ Donor program.

We are asking for help to cover the funeral and medical expenses.

Salon Talks with Ali Velshi: A normal interest rate “doesn’t mean the world is coming to an end”

“Salon Talks” host Carrie Sheffield on Monday sat down with global affairs and economics journalist Ali Velshi to discuss the effect — real or perceived — of an interest rate hike on the U.S. economy.

“This is a very important moment that we’re in,” Velshi explained. “Are rates actually going up? And what does the world look like with higher or more normal interest rates? We haven’t seen that for eight, nine years.”

“We’re not too far from that,” but the Federal Reserve raises rates in quarter-point increments, so the U.S. may not see a “comfortable” interest rate — between three and six percent, by Velshi’s calculations — for another decade.

“But ultimately we’re very worried that the world will just collapse if we actually have interest rates,” he continued. “The idea that you might pay six or seven percent for a mortgage doesn’t mean the world is coming to an end.”