Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 50

June 8, 2018

When evolution’s path leads to a dead end

Getty/Aunt_Spray

This article originally appeared on Massive.

Seventy million years ago, in a warm shallow sea, swam an ostracod — a tiny bean-shaped creature, no bigger than a grain of sand. The intricate features of his long, smooth shell, or carapace, identify him as K.cushmani. His carapace hid and protected his delicate body – like a shrimp stuffed inside a clam shell — as he propelled himself with scrabbling legs toward the bacteria he fed on. Around him swam hundreds of other ostracods, just like him, though the females were slightly fatter. Unbeknownst to our K. cushmani, this gender difference in body shape — known as sexual dimorphism — marked him and his kind for failure.

Sexual dimorphism describes these physical — or morphological — differences between males and females of the same species. Differences might include size or shape of the body, color, or ornamentation. Think of the peacock with his iridescent feathery fan compared with the subdued colors of the peahen; the male elephant seal with his enormous bulk and bulbous nose, compared with his relatively slender female counterpart; or the moose and his impressive antlers, where the female has none.

Sexual dimorphism is a result of males and females diverging down different evolutionary paths through selection processes, such as competition to reproduce. These processes happen for a variety of reasons. In some cases, strong colors in male birds are a sign of health. The elephant seal’s bulbous nose allows him to roar loudly to defend his territory – and his harem. And the moose’s antlers are used to intimidate or fight other males. Sexual dimorphism is the end result of choices made by mating partners and can increase the likelihood of reproduction: I would bet on the moose with the biggest antlers, wouldn’t you?

But what about the long run? What’s the impact on survival of the species? There are conflicting theories about whether sexual dimorphism is a good plan for a species. On the one hand, previous research by scientists at the University of East Anglia in the UK argued that selection processes — including those that lead to sexual dimorphism — weed out disadvantageous genes, improving adaptation and increasing the chances of species survival. But on the other hand, investing heavily in selections that benefit reproduction may come at an evolutionary cost, reducing a species’ overall ability to adapt and survive.

Think of those brightly colored birds. Yes, they’re attractive to females, but they are also easy for predators to spot. So males may inadvertently reduce their likelihood of survival. “Well,” you may say, “males aren’t such a big deal. It takes only a few males to keep a population ticking along.” But sometimes males can also reduce the evolutionary fitness of females. For example, researchers from Tufts University showed that the ejaculates delivered with fruit fly sperm can cause female fruit flies to avoid mating again, reducing the number of offspring. This is a much more damaging impact for a species.

So is sexual dimorphism advantageous or not? This was the question that ecologist John Swaddle of the College of William and Mary was trying to tackle by studying birds. But he was confounded by the problem that it’s not possible to study extinction risk directly in living species; the best we can do is look at proxies for extinction, like population decline. But even if a species is clearly under evolutionary stress, how do we know that extinction will be the outcome until it happens? How can we be sure of the ultimate effects of interacting drivers of environmental change, competition, and resource pressures.

The answer is: we can’t. That’s where paleontologists Rowan Lockwood of the College of William and Mary, Gene Hunt of the Smithsonian, and Markham Puckett of the University of Southern Mississippi came in. Hunt had been focusing on fossil ostracods – one of the few taxa where sexual dimorphism can be readily identified in the fossil record. And they brought in Maria João Fernandes Martins, an ecologist who had studied reproduction in living ostracods at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag) in Zurich. Now, she would tackle similar questions in their fossil counterparts.

“I thought, if we can answer the question, it’s with this study,” Fernandes Martins said.

The fossil record is our history book of Earth’s extinct species. It’s not a perfect record. In fact, it’s pretty awful. It’s both incomplete and poorly preserved, as if someone had ripped out 950 pages from a 1,000-page book, and the ink on remaining pages is smudged. Fossils are only preserved in the most fortuitous of circumstances: where there is water, when organisms are buried quickly, when there is limited oxygen, when the creatures have hard parts that don’t easily fall apart. So our fossil record is only a fraction of the story. But nonetheless, it’s the record we have. And in some cases, like ostracods, it’s quite handy.

Ostracods have been around for almost 500 million years – not long after multicellular life first bloomed on Earth. And they’re remarkably resilient, still living today in almost every wet environment: open oceans, freshwater rivers and lagoons, caves, hot springs, even in groundwater. But you’d hardly know they’re there. Ostracods are tiny. Most are a fraction of a millimeter long. But they’re abundant, which is one of the things that makes them so useful. In fact, there are a bunch of things that make these little guys useful: there are often large numbers of individual ostracods preserved, making them great for statistical studies; they have a hard carapace that is often well preserved and which is different in different species; many, but not all, species have sexually dimorphic carapaces; and there are many well-documented extinct species from different environments and time periods.

The team of researchers set about studying 93 species of extinct ostracod, featured in a recent study published in Nature. Under a binocular microscope, Fernandes Martins and her colleagues photographed thousands of individual ostracods that lived in the late Cretaceous, from about 84 to 66 million years ago.They then painstakingly digitized the outlines of each, which were then used to measure the length-to-width ratios – the shape and size – of different species. In most species, differences in shape and size very cleanly distinguish males and females. How did they know these differences relate to genders, and which was which? Because many species of ostracods are still alive today. So they were able to compare characteristics of extinct ostracod species with the abundant living species.

The next step was to figure out what correlation, if any, existed between sexual dimorphism and how quickly species became extinct. To do this they used a computational model that is commonly used in living wildlife studies – a catch-mark-release model designed to look at individuals, how long they live, and where they go. The model was adapted to fossil studies, where it is increasingly being used, so that instead of individuals, the model assesses species. And instead of life spans, it models extinction rates. For over 6,000 individual ostracods, the team recorded the size, shape, and species of each fossil, and when they lived – by looking at where they occurred in the rocks. The software used all of this data and different combinations of these factors to generate hundreds of models, assessing how well each model predicted the likelihood of extinction.

It turns out that sexual dimorphism correlates extremely well with increased extinction rate, with more than 99 percent of models correlating the two. But it’s not sexual dimorphism itself that’s the problem – it’s the type of sexual dimorphism. Only where males were larger or more elongate than females was the extinction rate higher. In living ostracods, larger or more elongate male carapaces are used to house larger sex organs. So by analogy, for the fossil species, males that invested more resources in reproduction did so at significant evolutionary cost.

The study showed that extinction rates in ostracods with the most pronounced sexual dimorphism of this type were 10 times higher than those with the least pronounced dimorphism. And while the researchers expected some correlation, “I never expected it to be so clear, so strong,” said Fernandes Martins.

So those ostracod species where males invested heavily in sexual selection chose poorly, it seems. Evolutionary stresses impacted them more than ostracods with more similar genders, sending them quickly into the evolutionary history books.

Does this mean the same applies to other taxa that show sexual dimorphism? That’s a hard question to answer, because it leads us back to the same old problem of assessing extinction risk in living species. But research on living species has led to increasing evidence that specialization does correlate with extinction rates.

Although specialization allows species to be highly adapted to their environment, it doesn’t mean they’re adaptable. If conditions change, they are likely to be more at risk. And this doesn’t apply just to morphological specialization – like sexual dimorphism – but specialization generally: in habitat, geographic range, maturation age, behavior, and environmental tolerance. In previous research, scientists from the University of Miami gave many examples, such as thermal specialization, which is linked with population decline in lizards. Researchers have noted many examples of specialized species that are, or would be, under increased stress with changes to their environment: changes such as temperature, water chemistry, habitat reduction, prey diversity, or volume. In fact, scientists from the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris have proposed that there is already a worldwide decline in specialist species as a consequence of human impact.

It’s easy to view the progress of evolutionary selection as one-directional – leading toward ever more refined and useful traits. In Darwin’s words, “natural selection will tend to render the organization of each being more specialized and perfect, and in this sense higher.”

But nature does not always make the right choices. Sometimes those choices lead to evolutionary dead ends.

Ostracods’ message to us is that sexual dimorphism can be a major risk factor for extinction. And while it’s not necessarily a death sentence — while there are many factors that contribute to the survival of a species – in these times of marked human impact on natural ecosystems, it just might pay to take special care of our specialized friends.

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

Video gamers may soon be paid more than top pro athletes

Getty/scyther5

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Your interest in sports may have started out as a hobby when you were just a kid. You were better at it than others, and some even said you were gifted. Maybe you had a chance to develop into a professional athlete.

Colleges would soon line up to extend full scholarships. If you pushed hard enough, practised countless hours and kept a cool head, lucrative contracts and international fame awaited.

This fantasy plays out for many North American kids who dream of “making it to the big leagues.”

Whether they play hockey, football or basketball, even the most remote possibility of turning their love of the game into a respected career is worth sacrificing for.

Enter video games.

In less than a decade, the realm of professional sport has been taken by storm by the rise of eSports (short for electronic sports). These video game events now compete with — and in some cases outperform — traditional sports leagues for live viewership and advertising dollars.

For the top eSports players, this means sponsorship contracts, endorsements, prize money and yes, global stardom.

Games on TV still command high ad dollars

This week, dozens of professional video game players will descend on Toronto during NXNE, an annual music and arts festival, to compete in different games for prizes of up to US$1,000. Not a bad payday, perhaps, but still chump change in the eSports scene.

For example, Dota 2, a popular battle arena game published by Valve, recently handed out US$20 million to its top players during its finale.

What does this mean for traditional sports? And sports TV viewership?

The lasting broadcast success of sports leagues games can be explained by the fact that they are meant to be shared happenings and are best experienced live. As such, they have been resilient to disruptions within the media landscape and somewhat spared by the advent of on-demand streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.

The ability to capture a sizeable number of “eyeballs,” long enough and at a precise time, is the reason why professional sports leagues still command huge TV rights and advertising dollars.

In the past few years, the “Big Four” North American sports leagues have all struck new deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Shifts in sports culture

Some leagues like Major League Baseball, and their once subsidiary Advanced Media division (MLBAM), have long embraced technological innovations to enhance audiences’ experience.

Meanwhile, media and telecommunication giants have been slower to catch on.

In 2016, John Skipper, then president of ESPN, referring to cable TV packages said: “We are still engaged in the most successful business model in the history of media, and see no reason to abandon it.”

This attitude, at the time, was not only symptomatic of a lag or inability to adopt technological innovations, but also raised concerns about the company’s future.

But the decline of the traditional linear broadcast, and the risk of losing relevancy in this digital, broadband and tech savvy media landscape is inevitable, and forces these media giants to question their traditional business models and to focus on online audiences.

Along with this shift, a new, popular and expansive trend for the new generation has emerged - eSports.

Whether eSports are actual sports or not is a whole other debate; however, the emergence of the global video game competition field demands attention and strategic investment.

Why eSports is doing so well

As a spectator sport, video games generate viewership at least on par with professional leagues.

Take, for instance, 2016’s League of Legends tournament that drew 36 million viewers, five million more than the NBA Finals, in front of a sellout crowd at the famous Bird Nest stadium in China.

eSports mimic traditional sports leagues principles: Exciting content, likeable stars, catchy team names, slow motion highlights, intense competition and an uncertain outcome.

These video games attract audiences as they are no longer simply designed to be played, but increasingly to be visually pleasing for audiences.

Age-wise, compared to traditional sports that struggle to diversify their audience demographics, eSports have successfully attracted younger viewers.

The fan base is pretty young, with 61 per cent of fans falling in the 18-34 age range. Young men, in particular, are a desirable market for many advertisers.

eSports attracts advertisers

The economic outlook for video gaming sports is staggering. According to NewZoo, eSports “on its current trajectory is estimated to reach US$1.4 billion by 2020.” And a “more optimistic scenario places revenues at US$2.4 billion.”

Companies like Red Bull, Coca-Cola and Samsung, all usual suspects when it comes to advertising and young people, are flocking to eSports.

In recent years, eSports has made efforts to monetize across traditional revenue streams, such as merchandise sales, subscriptions plans, ticket sales and broadcast rights. It is, once again, taking a page straight out traditional sports leagues’ playbook.

So, what can established leagues and media giants do? Given the choice between fighting eSports or joining them, many appear to have chosen the latter. Recall ESPN resisting change in 2016. Then fast forward to their recent strategic investments in the digital platform BAMTech, once MLB Advanced Media, in order to launch ESPN streaming services.

As a result, Disney, the 100 per cent owner of ESPN, now has a say in League of Legends streaming because its publisher Riot Games had signed a seven-year US$350 million dollar broadcast deal with BAMTech.

FIFA just partnered with Electronic Arts on a online tournament that drew 20 million players and 30 million viewers. Also hoping to create platform synergies and to reach new audiences, Amazon acquired Twitch in 2014, the leading game streaming service.

These examples show that eSports are not just popular with gamers, but also among sports leagues and media giants. Both stand to learn from each other. No wonder Activision’s CEO said that he wanted to “become the ESPN of eSports.”

This popularity also opens up more opportunities to compete on the professional level and earn huge endorsements, prize money and salaries just like LeBron James, Serena Williams, Danica Patrick or Sidney Crosby.

In fact, higher education eSports programs are already launching across the country and college scholarships are now commonplace, further acknowledging the economic viability and social acceptability of this phenomenon.

And with talks of introducing eSports in the Paris 2024 Olympic Games, Canada’s “Own the Podium” program may soon have to follow suit.

In any case, it turns out that our parents were wrong all along: You can stay glued to your console in the basement all day and still make it pro.

Louis-Etienne Dubois, Assistant Professor, School of Creative Industries, Ryerson University and Laurel Walzak, Assistant Professor, RTA School of Media, Ryerson University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

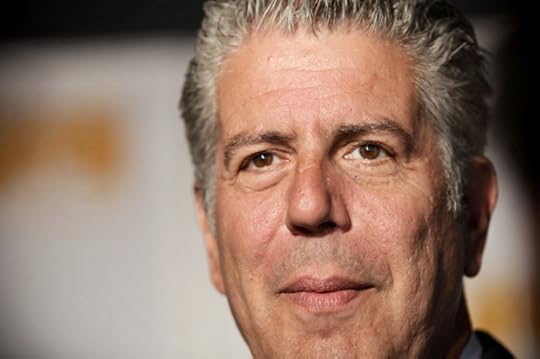

Remembering Anthony Bourdain: The chefs and writers he knew and inspired reflect

Getty/Neilson Barnard

There was a pause this morning when the news of Anthony Bourdain’s passing landed. A stunned silence, and then a buzz. ”I got 45 text messages, almost all at once,” said chef Scott Bryant, whose mastery Bourdain chronicled in his book, the 2000 breakout success “Kitchen Confidential.”

“It’s mind-boggling. I’m in shock. Just last week I called [Eric] Ripert to make a reservation at Le Bernardin for a customer. Eric said ‘sure, I’ll take good care of them, but I’ll be on the road. I’m going to Alsace with Tony that week.’”

Ripert and Bourdain were close friends and often traveled together. It was Ripert who is reported to have discovered his dear friend’s body this morning in Bourdain’s hotel room in France.

“Years ago, back when Emeril Lagasse had like five shows on at once, I used to be in the kitchen at Indigo working six nights a week,” remembers Bryan. “Tony used to come in and visit late in [the dinner] service and tease me, ‘Hey, Scott why don’t you call up the Food Network, get yourself a show.’ That wasn’t me. I don’t speak good English and, for the most part, I’m a misanthrope — I hate people. Tony would laugh and say, ‘You’re the last of the Mohicans,’ and maybe he’s right. But I’ve never seen Tony depressed. I’ve never seen Tony angry. I’ve never seen Tony pissed. He’s always been a happy-go-lucky guy. Smoke a little weed and get mellow. He never let fame get to his head.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Andrew Friedman, author of “Chefs, Drugs and Rock & Roll,” a history of American chefs. “He created an interest in chefs. People didn’t care about chefs until ‘Kitchen Confidential,’ not really. I read in Publisher’s Weekly that one year Bourdain wrote the most forewords to other people’s books, and you know what he said about that? He said ‘hey, there was a time I had just written my first book too; I just want to make it a little easier, just help where I can.”

“Tony treated writers as well as chefs as colleagues. It was flattering,” said Friedman. “I really think he knew what he meant to people and he wore that mantle very comfortably.”

Bourdain was a writer and a TV personality, but he took responsibility for the stories he was telling, made sure they were the stories he wanted to tell, told the way he wanted to tell them. “He totally was aware of what appropriation was. He came into people’s houses as a participant, not a tourist,” said Michael W. Twitty, chef, historian and author of "The Cooking Gene." "He is there totally, and with respect. He experienced the lives of others. He displayed and celebrated the food cultures of West Africa. Nobody, really nobody did that. All of it -- music, dance politics, culture -- he knew you had to include it all. And he broke bread with everybody: Felicia 'Snoop' Pearson from ‘The Wire,’ Tahitian transgender folk, kids in Haiti, poor white Americans, President Obama, everybody.”

“It’s hard,” said Twitty. “It’s hard to see someone so full of life, so loved, a father, a seeker, just gone. I woke up this morning and I heard the news and I thought, ‘Wow. I’ll never get a chance to shake that man’s hand and say, just thank you.’”

Last year, Bourdain sat down with Salon’s Alli Joseph on “Salon Talks,” along with director Lydia Tenaglia and celebrated chef Jeremiah Tower, the subject of the documentary "Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent" that Bourdain executive-produced for CNN. Here is their conversation:

You two have worked together for many years in production of your projects. How did you come to find Mr. Tower and what made his story interesting?

Anthony Bourdain: I’d read Jeremiah’s memoir, originally titled “California Dish,” and it was shocking to me… of course it was wildly entertaining that it was shocking to me for a number of reasons. First, it made a compelling and inarguable case for the way in which Jeremiah transformed the American dining scene, how we look at American ingredients, how we eat today, the role of the chef in our culture, all of these things to a very great extent starting with Jeremiah. But also, what resonated was that I’ve been cooking a lot of dishes and feeling his influence without ever even knowing it for much of my cooking career.

I felt a sense of outrage and injustice that Jeremiah’s contribution to the way we eat today and the role of the chef, from which I personally benefited ,that he’d been, to a great extent, written out of history by the complicity of knowingly lazy journalists who first started telling sort of an alternate version of history and then, because they’d invested so much time in telling a false version, just continued to tell it, and that was my original sort of driving force that it pressed my justice button. But of course, it’s so much more than that. What we ended up with was a really terrific portrait of a complex and brilliant artist.

Who is Jeremiah Tower, the artist, now, many years after leaving Stars, the restaurant that you became very famous for creating? You were gone for about two decades, correct?

Jeremiah Tower: Yeah, 15 years or something like that. But you know, restaurants are very noisy places and Stars was a full Berlin symphony orchestra. Thank you for calling me an artist, but I think as an artist, you need good balance, so I just needed the quiet of a tropical beach for a little while and to go scuba diving. I found my balance and now it’s time to be back.

It seems that there’s a real important and strong tie for you between food and love. Is that the case, and initially, in the lack thereof, this became something you could pour yourself into?

Tower: I never thought that until I saw the film and, actually, they’re asking me the questions and I thought, “Yeah, that’s probably right, absolutely.” I mean, I thought it was great to be left alone. You’re in a huge suite in London’s most fancy hotel in the ’50s and my companions were the waiters doing the room service; I had a great time. I would go down to the dining room, there’s no one there, and it’s a vast dining room, and eat caviar, McSalmon until I couldn’t eat anymore, so this was fun; but obviously, that became imprinted somehow as the best thing in my life, the only thing in my life at that time. I think you’re right, yes.

What is your favorite dish to cook and why?

Tower: You go first.

Bourdain: I like baking. For most of my career, I was cooking French food or American food. I like cooking Italian food, really rustic like a ragù of oxtail, Naples’ style, slowly braised neck, shoulder, or oxtail and a red sauce with some pasta. I’m very happy making pasta.

Tower: With wonderful buttery noodles to the sauce, yes.

Bourdain: There’s something magical at that moment where the pasta takes in the sauce.

Tower: Takes in the sauce, yeah.

Bourdain: That’s still magic for me.

Watch our full conversation with Anthony Bourdain

Anthony Bourdain discusses his love of food with Salon and chef Jeremiah Tower

As such accomplished chefs, is it difficult to be served? Are you always imagining criticizing what you’re eating and/or can you really appreciate it?

Bourdain: For me, and I think it’s true for most chefs I know, the last thing you want to do when you go out to eat is think about food in a critical, analytical, professional way. For me, a perfect meal is something very, very rustic where I could experience it in a purely emotional way, like a child. I don’t want to think about it at all, and the further away I could get away from that, the better.

Tower: Yeah, you don’t want to think about it. You just want to jump in and roll around in it.

Every chef has maybe a top five ingredients that must be in their kitchen at all times. What are those ingredients for you?

Bourdain: Butter, good olive oil, some sea salt, that’s the beginning, and a sharp knife and the rest will come.

Tower: Those are my first three as well, so yeah. I just tasted this salt someone gave me in Seville. He gave me some sea salt from Ibiza which… okay, beach clubs and everything, but I didn’t know about the salt -- it is absolutely incredible because it’s salt, but it doesn’t taste… it’s not strong, it doesn’t burn, and it slowly evolves in your mouth. I never had a sea salt like that before.

Bourdain: But if you have those three things, you can pretty much conquer the world.

How do you conjure up elements of simplicity and unusual food, which people find unusual but so tempting and satisfying at the same time?

Tower: There should never be more than three or four ingredients on a plate. It’s just too confusing, especially now that you’ve got all these dots going around. I’m supposed to take my fork, dip it into each dot and taste it separately. Am I supposed to take my finger and smear them up together and taste it? That’s all rubbish.

Bourdain: It’s an oblong dish and it requires instructions by the waiter: “Starting on the left, chef prefers moving clockwise. Eat this first.” It makes me stabby. I get really angry and upset, and I’m taken away… right away, I’m taken out of that possibility of an emotional experience and now I’m thinking, “I've got to think about how to eat.” I've engaged my waiter in a way that’s intrusive and I’m boiling with rage. This is not a good way to live.

This, you’re referring specifically to when something comes on a plate and you don’t know how to eat it, versus say courses in flights and things?

Bourdain: No. They’ll come and tell you. In a way, I think we both kind of have to… we're partially responsible, particularly Jeremiah, in the sense that before Jeremiah, no one cared what the chef thought. The last person you wanted to see in the dining room was the chef. Jeremiah was the first professional chef in America who customers not only wanted to see, but insisted on seeing. It was an important part of the experience. It was part of that power shift where people started to care what the chef thought, and now we've reached at times absurd extremes where the chef is providing you with a long instructional on how you’re going to eat your chicken.

Tower: I mean, it’s not food anymore, it's the chef — “Me, me, me, me, me.” But a great chef, I think we both agree, a great chef is someone who finds perfect ingredients, knows how to store them, knows how to cook them simply and properly, and let them be the grandstand. Let the ingredients say everything and the chef stands back.

Is there anything you refuse to eat?

Bourdain: Johnny Rockets hamburgers. Worse meal ever.

Lydia Tenaglia: No, it isn’t.

Bourdain: Yeah, the worst.

Tenaglia: No, you’re wrong. I disagree with you.

Bourdain: Heinous.

Tower: For me, there’s only one that I refuse, something in the Philippines called “balut,” which is the egg with the fetal duck -- and it’s all the way from first fetal to final fetal with feathers and bones sticking in your teeth.

Wait, they give you all the stages?

Bourdain: No, it’s in the egg.

Tower: You choose your stage, but it could be. When they take the top of the egg off, it could be a little beak sticking out and I just said, “No.”

Bourdain: My 10-year-old daughter loves balut.

Tower: Really?

Bourdain: It’s crazy. I’m really impressed, I mean because I’m not a big… I mean I’ll eat it, but I’m not a big fan.

That begets the question, you cut the head off and then you have to eat it?

Bourdain: No, you slurp it and then spoon it right in.

What is your favorite food city in the world?

Bourdain: Tokyo.

Tower: Tokyo, yeah. I would have to agree, though Rome is a real close runner-up.

Bourdain: If I’m planning on dying there, I’d say Rome, but spending considerable amount of time eating, Tokyo.

What would be your last meal be if you had to choose?

Tower: My last meal. Oh, my goodness. If I’m going to die, I might as well kill myself, so there’s at least a case of champagne involved in the beginning. You’d be halfway to death if you drink the whole thing, so that’s fine. Then I would have someone find me a two-kilo tin of beluga caviar, and I say that not just because it’s a fancy food, it’s because I haven’t seen it in decades. It's becomes so rare, but it is absolutely delicious when you eat it with a spoon and then I’m nearly dead at that point. Then, I think I’ll have a baba au rhum with old Martinique rum and a great big jug of English cream, until it’s drowned and then I’m done.

Bourdain: I would be eating some really high-test sushi in Tokyo, and I'd just work my way through all of the sushi and around just as they serve me the tamago, the omelet, at the end, if you would shoot me in the back of the head, as I slump to the ground leaking my life’s blood onto the cold tile floor, I would have no regrets. I would not feel cheated having just experienced that meal.

Tower: But as you’re just about to… on the floor, you’re gasping… what was the last thing they’d put in your mouth?

Bourdain: Yeah. It’s probably unagi.

But I mean in reality, it’s probably going to be some hotdog on the street. It’s the closest I’ve come to death in my life. I was really hungry, and I’m halfway down the dog, and I didn’t order any liquid, and I start to choke. I’m choking and asphyxiating on the street. I’m too embarrassed to stop passersby to, like, Heimlich me, and I'm struggling to breathe with a big wad of like dirty-water hotdog in my throat and I suspect that it's much more likely to be this scenario.

Tower: That would be embarrassing in New York for Anthony Bourdain to have a hotdog shoot out of his mouth.

Bourdain: I mean Mama Cass will always be remembered for that ham sandwich and I suspect this is my destiny as well.

She’s the breadwinner and OK with it: A Gen X perspective for “conflicted” millennial women

It’s Sunday morning and my husband and I are in a heated conversation about tomato plants. We have two container beds in our backyard to grow tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers and zucchinis, but he has two tomato starters still to plant. He wants to experiment with an upside down tomato planter he has seen online. Instead of buying upside down tomato planter baskets, he is going to make a contraption for the tomato plants using two white, five-gallon buckets we have in the garage.

This means that somewhere in our backyard, there will be two five-gallon buckets hanging upside down that I would rate a one on a one-to-ten scale of aesthetically pleasing yard decorations.

We compromise: he gets to hang the buckets but they will be placed in an area of our yard where our neighbors can’t see them, and I don’t have to look at them while drinking coffee on our back deck. This debate is resolved quickly compared to our ongoing arguments over who folds more laundry, who is taking our daughter to her piano lesson or how recently the refrigerator was cleaned out.

Throughout our 22-year marriage, there have been many conflicts for us to overcome, but me being the consistent breadwinner has never been a problem. The fact that my salary hasn’t even registered as an issue between us leaves me genuinely confounded when I read a Refinery29 article from last year that recently recirculated, igniting a fresh round of debate on the subject, listing a number of reasons millennial women feel conflicted about out-earning their partners. After more than two decades together debating nearly every detail of our life – from upside down tomato planters to dishwasher-loading techniques — I wonder why my salary has never been a problem within our marriage. Could my indifference to being the breadwinner — and the conflicted feelings millennial women have around it — really be tied to the generations we have been folded into?

My husband and I are both Generation Xers (I was born in 1973, my husband in 1972), and we married young; I was 23 and he was 24. The night we met – exactly one year prior to our wedding date – neither of us had started our careers yet. I had graduated three months earlier with a Bachelor of Arts in English and he was only three weeks out of the Marine Corps. Both of us were still undecided about what to do with the rest of our lives. I was working as a waitress, not sure if I wanted to apply to graduate school. He was unemployed, still living off of his military wages.

The start of our careers aligns with the start of our relationship. By the time we moved in together, I had decided against going to graduate school and accepted an entry level job at an ad agency. He began working for an electrical services company, training to be an electrician. We both knew, because of my degree, I would most likely earn more. Even with our first jobs in 1995, I was a salaried employee making approximately $24,000 a year. He was paid hourly, earning a couple dollars over minimum wage.

Eventually, my husband earned a technical degree along with the necessary networking certifications to manage computer systems, but our earning power was already established. As I worked up the ranks into more senior marketing positions, my paycheck grew at a faster rate than his did. Not once did this cause a rift between us.

As Generation Xers, we are sandwiched between baby boomers and millennials. In an interview with Goldman Sachs, generation expert Neil Howe (the author who coined the term millennial) defined Generation X as latchkey kids who trust no one. “From early on, they understood that focusing on the bottom line was more important in life than ideals.”

Millennials, on the other hand, have been shaped by different forces. A 2015 report from Goldman Sachs claims lower employment levels and smaller incomes have left millennials with less money than previous generations. As a result, millennials are more likely to postpone commitments like marriage and home ownership.

The Millennial women interviewed in the Refinery29 article used words like “tired,” “exhausted” and “resentful” when asked how they would feel if they knew they would always be the breadwinner. I imagine, as a generation faced with fewer employment opportunities and less earning potential than previous generations, being charged at the beginning of a relationship with the bulk of your financial well-being for both you and your partner would feel tiring and exhausting and could make you resentful.

As a working mother of a fourteen-year-old and nine-year-old, there are definitely days I feel tired and exhausted, but not because I am the breadwinner. Being tired and exhausted is inevitable when you have a full-time career and kids. I am sure when I’m out of town, or unavailable to cook dinner, pick up the clutter of our lives and handle bedtime routines, my husband is just as tired and exhausted as I often am at the end of the day.

It has never occurred to me that I would feel resentful about earning more than my husband. Mostly, I am thankful I can contribute what I do to our income and grateful for the career I have (realizing that as I type this, I’m only reinforcing my Gen X nature of remaining focused on the bottom line).

There have been two times during our marriage when my husband earned more. The first time was in 2003. We were both working full-time when I was laid off from my marketing manager position with a local health care company. Instead of searching for a new full-time job, I began freelance writing. While he continued to work full-time and provide our health insurance, I began building a short list of client work that amounted to less than half of what I was earning as a full-time marketing executive.

Within a few months of being a freelance writer, I became pregnant with our first child. What we thought was going to be the perfect setup — him working work full-time, bringing home most of the money and providing our health insurance, while I had the baby and freelanced — ended abruptly when he lost his job six months into the pregnancy.

Already panicked about becoming first-time parents, we were now both unemployed and faced with an $800 per month Cobra payment to continue our health care coverage. The only logical solution was for both of us to begin a job search.

At six months pregnant, my interview attire consisted of a long black button down dress blazer that hit well below my waist to hide a rapidly growing baby bump — it looked like something Prince would have worn if he was a mid-level bank manager. On our tight budget, I bought the blazer to pair with the black dress slacks I already owned but couldn’t zip up over my now protruding stomach.

Less than a month into the interview process, my husband was offered a position that came complete with full benefits – and I was offered a contract position, that turned into a full-time role as a marketing director. Within a year of becoming a new mom, I was earning nearly double my husband’s salary. We were both thrilled — we had a new baby, new jobs, two paychecks and health insurance. Not once did it occur to either of us that there was a problem with me earning more.

Maybe our indifference to my role as the breadwinner isn’t connected to being Generation Xers but instead because we address our biggest challenges — like being pregnant and unemployed — as equal halves of the same unit. We’ve built our careers the same way we’ve built our relationship, each of us supporting the other in whatever way we can. I’ve never looked to him to save me, and his masculinity has never been threatened by my abilities. I know this because when I asked him if he has ever felt threatened that I earn more, his response wasn’t a "yes" or "no" answer. Instead he asked me, “Why would I ever feel threatened by how much you make?”

My husband knew what he was getting when he married me. Along with my English degree, I minored in women’s studies. I also chose to keep my maiden name. The first night we met, we spent most of the evening arguing over Shannon Faulkner’s treatment during her time as the first female cadet at The Citadel and whether or not she deserved to be there. (It took nearly 20 years, but I have since convinced him she did in fact belong there and was horribly mistreated by fellow cadet members as well as the state of South Carolina.)

While who we are within our stations in life may in part be attributed to our generation, my ideas around work and a woman’s earning potential were also shaped by my grandmothers. Both women worked outside the home during an era when working mothers were not part of the cultural norm. My maternal grandmother began her career as a switchboard operator for the local phone company when she was a teenager. She remained with the phone company until she retired in the mid-1980s, working her way up to the executive offices as administrative support to the C-level suite. While it was never confirmed, I am sure she earned more than my grandfather, a factor that no doubt played into their divorce.

My father’s mother was an entrepreneur by necessity. After her divorce in 1970, with four of her six children still living at home, she had only $6.38 in her bank account. My grandmother supported herself and her family running a local grocery store she opened in our small Indiana town. It remained in business until I was in grade school.

Both of my grandmothers took responsibility for their financial well-being at a time when many women didn’t even have checking accounts in their own names. I can’t begin to imagine the challenges my grandmother faced and the sexism she overcame during her 40-year career as an office worker during the second half of the 20th century. I am just as awed by my other grandmother’s strength and resiliency to rebuild her life and create financial stability for herself and her children.

The second time my husband out-earned me during our marriage was six years ago. I was desperate to make a career change and left my job as a marketing director — and my senior-level salary — to become a writer. I remember sitting alone in my home office one morning, just days after quitting my full-time job, in a near panic attack over what I had done. My husband had already left for work and the kids were at school when my phone rang.

“It’s me,” said my husband, “I just wanted you to know how proud I am of you. We’re going to be fine, no matter what happens.”

He was right. Within a year, I landed a full-time role as a reporter. By this stage in our marriage, his annual income was within $20,000 of mine, but I was once again the top earner in our relationship and have remained the breadwinner ever since. Without his encouragement, I never would have had the nerve to change careers — and without his unwavering faith that we would both be OK, neither of us would have come as far as we have in our work or our marriage.

We may not agree on how best to hang upside down tomato vines, but whatever it is we planted more than 20 years ago has kept us from suffering any conflicted feelings over who earns more. I don’t know if this is a generational thing or simply who we are. I do know that we consider our income in the same way we consider all other aspects of our married life — as something we’ve built together.

Alex Jones has a vile Bourdain take. The world serves as a corrective

AP/Andy Kropa/YouTube/The Alex Jones Channel

Since the news arrived Friday morning that beloved chef, author and TV host Anthony Bourdain had committed suicide, the world has been collectively mourning. Well, except for Alex Jones.

The far-right conspiracy theorist took to Twitter to offer a vile take on Bourdain's death. "Anthony Bourdain had the guts to call Henry Kissinger an evil war criminal and Hillary 'shameful' for defending Harvey Weinstein! Hope he is in a better place.. Hillary has called me 'Dark Heart' so let me just say again I will never kill myself!!," Jones tweeted Friday morning, and included a screenshot of an excerpt from Bourdain's book, "A Cook's Tour: Global Adventures in Extreme Cuisines."

Anthony Bourdain had the guts to call Henry Kissinger an evil war criminal and Hillary ‘shameful’ for defending Harvey Weinstein! Hope he is in a better place.. Hillary has called me ‘Dark Heart’ so let me just say again I will never kill myself!! pic.twitter.com/r8SGp1z8Wi

— Alex Jones (@RealAlexJones) June 8, 2018

Somehow, Jones found a way to not only shame Bourdain and all those who suffer from mental illness, but also to disparage Hillary Clinton and — remarkably — make Bourdain's death about Jones himself and his own political grievances.

This type of narcissism and outlandish behavior is far from new for the conspiracy-peddler and media personality. Jones infamously spent years trying to discredit the Sandy Hook massacre school shooting, in which 20 schoolchildren and six adults were shot and killed. On his radio and TV show "Infowars," Jones promoted the theory that the Las Vegas mass shooter Stephen Paddock had to be a liberal because "he drank Pepsi!"

"I mean, literally, conservatives do not drink — especially in the Obama era — conservatives drink Coca-Cola. If you drink soft drinks, liberals drink Pepsi," he added. "Now, that's a big clue!"

Jones has long been a sympathizer for white nationalist causes. Indeed, recently Jones insisted that the white supremacists and neo-Nazis who marched in Charlottesville in August 2017, inciting violence that left one woman dead, was not their fault, but rather the work of "Jewish actors." While Jones refuses to believe that actual neo-Nazis are Nazis, he has no problem depicting Parkland activists David Hogg and Emma Gonzalez as members of the Hitler youth. In a recent broadcast, Jones juxtaposed Nazi imagery with footage from the March For Our Lives mass demonstration in Washington, and replaced Hogg's speech from that day with declarations from Adolph Hitler. These are just a few examples.

But given Bourdain's progressiveness, his attention to representation in the food industry, and reverence for food origin, it makes sense why Jones responded in this way. As food historian and author Michael W. Twitty wrote of Bourdain on Twitter, "Black folks loved this man because he didn't appropriate, when it came to us all he could do was celebrate. He told the world we were the center of Southern [and] Brazilian food and he let us speak for ourselves."

"Anthony Bourdain was the John Brown of food media," Twitty concluded.

Black folks loved this man because he didn't appropriate, when it came to us all he could do was celebrate. He told the world we were the center of Southern&Brazilian food and he let us speak for ourselves. #AnthonyBourdain was the John Brown of food media.

— Michael W. Twitty (@KosherSoul) June 8, 2018

Twitty added that Bourdain was a rarity in the food world and sought to move the industry away from its predominantly white gaze and often harmful stereotypes of black culture and people. "He called Africa the cradle of civilization, took his cameras to Haiti," Twitty said, "broke bread with Obama like a human being."

#AnthonyBourdain did not exploit race or religion or other human conflicts, rather he illuminated how food played a role in the deep passions behind those conflicts and challenged us to not see bad or good but human.

— Michael W. Twitty (@KosherSoul) June 8, 2018

Bourdain "did not exploit race or religion or other human conflicts... rather he illuminated how food played a role in the deep passions behind those conflicts and challenged us to not see bad or good but human," Twitty continued.

Just as Jones seeks to erase or revert the attention away from the beauty and sincerity of Bourdain's life and work, the world has chimed in and marveled at the nuance and versatility of the empathetic chef and writer.

Bourdain was found dead in a hotel room in Paris by the French chef Eric Ripert, according to CNN. "His love of great adventure, new friends, fine food and drink and the remarkable stories of the world made him a unique storyteller. His talents never ceased to amaze us and we will miss him very much," the network said in a statement Friday.

Beyond his accomplishments as a famous chef, author and TV host, Bourdain spoke openly about his past addiction to heroin. Likewise, in the era of #MeToo, Bourdain was unequivocal in speaking out about harassment in the restaurant industry.

Tennessee store puts “no gays allowed” sign back up after Supreme Court’s wedding cake ruling

USA Today

A Tennessee hardware store owner is celebrating the Supreme Court's ruling in favor of a Colorado baker who refused to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple by posting a "no gays allowed" sign in front of his business.

Jeff Amyx, who owns Amyx Hardware & Roofing Supplies in Grainger County, Tennessee, initially put up the sign in 2015 after the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage but later removed it following public backlash.

But the "no gays allowed" sign returned this week after the recent Supreme Court's decision, WBIR reports.

Amyx told the local news organization that the ruling, which he calls a victory for Christianity, came as a surprise to him.

"Christianity is under attack," Amyx claimed. "This is a great win – don't get me wrong – but this is not the end. This is just the beginning. Right now, we're seeing a ray of sunshine. This is 'happy days' for Christians all over America, but dark days will come."

Amyx initially posted the "no gays allowed" sign in front of his store in 2015 because "gay and lesbian couples were against his religion and he believed he should stand for what he believed in as a Christian," the local NBC affiliate notes.

But, due to intense criticism, he reportedly replaced it with a sign that read, "We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone who would violate our rights of freedom of speech & freedom of religion."

Amyx added that he fears a future Supreme Court decision will come out differently.

In a narrow 7-2 decision written by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy on Monday, the court said that "religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression.”

In addition, the court noted that Colorado law "can protect persons in acquiring products and services on the same terms and conditions that are offered to other members of the public, the law must be applied in a manner that is neutral toward religion."

On Thursday, an Arizona appeals court ruled that a Phoenix-based calligraphy business cannot refuse to serve same-sex couples, upholding the city's anti-discrimination ordinance as constitutional. The decision cited Monday's Supreme Court decision.

This week's Supreme Court decision leaves unsettled the broader constitutional questions presented by the case, as it did not issue a definitive ruling on the circumstances under which people can seek exemptions from anti-discrimination laws based on their religious views.

Dennis Rodman announces he is going to Singapore for Trump’s “historical summit” with Kim Jong Un

Getty/AP

Dennis Rodman is here to support President Donald Trump and North Korea leader Kim Jong Un in anyway he can, the former NBC star wrote Friday in a tweet announcing that he would be traveling to Singapore "for the historical summit" between the two heads of state.

In a tweet that was quickly deleted but then reposted, the athlete said: "Thanks to my loyal sponsors from @potcoin and my team at @Prince_Mrketing , I will be flying to Singapore for the historical Summit. I'll give whatever support is needed to my friends, @realDonaldTrump and Marshall Kim Jong Un."

Thanks to my loyal sponsors from @potcoin and my team at @Prince_Mrketing , I will be flying to Singapore for the historical Summit. I'll give whatever support is needed to my friends, @realDonaldTrump and Marshall Kim Jong Un. pic.twitter.com/QGPZ8nPrBE

— Dennis Rodman (@dennisrodman) June 8, 2018

Despite the accompanying image to Rodman's tweet – a composite photo of Trump, Kim and the basketball player including the words "UNITE" and the flags of both nations – he has not been formally invited to the summit.

"White House officials have repeatedly said that Rodman would play no official role in the diplomatic negotiations, and Mr. Trump said Thursday that the basketball legend had not been invited to the June 12 summit," CBS News reported.

"I like him," Trump said of Rodman. "He's a nice guy. No, he was not invited."

But Rodman does not seem deterred, following up his "unite" tweet with a photo of himself and the president.

"To all Americans and the rest of the world I’m honored to call @POTUS a friend," he wrote. "He’s one of the best negotiators of all time and I’m looking forward to him adding to his historic success at the Singapore Summit."

To all Americans and the rest of the world I’m honored to call @POTUS a friend. He’s one of the best negotiators of all time and I’m looking forward to him adding to his historic success at the Singapore Summit. #Peace #Love #MakeAmericaGreatAgain #MakeTheWorldGreatAgain pic.twitter.com/3t3VBMSGaL

— Dennis Rodman (@dennisrodman) June 8, 2018

And Rodman's agent, Darren Prince, confirmed the trip to CNN. "He is willing to offer his support for his friends, President Trump and Marshall Kim Jong Un," Prince said.

Rodman has traveled to North Korea several times since 2013. He has fervently defended the controversial leader, saying "I love my friend– this is my friend," during an interview on CNN in 2014. He also once sang happy birthday to Kim Jong Un before a basketball game.

Most recently, PotCoin, the cryptocurrency company for the marijuana industry, sponsored a trip he took to North Korea in 2017.

I'm back! Thanks to my sponsor https://t.co/zBtIFz1QBr. #NorthKorea #PeaceAndLove https://t.co/G7t6PX3WV9

— Dennis Rodman (@dennisrodman) June 13, 2017

"PotCoin's interest in North Korea, an isolated country, was not immediately known and none was provided in a press release from the company announcing Rodman's trip," my colleague Taylor Link wrote at the time of the trip. "Indeed, the exact nature of marijuana laws and marijuana cultivation in the country are hazy due to a lack of credible literature on the subject."

As part of the press release, Prince said, "Anyone who knows Dennis knows he’s trying to use his relationship to open the line of communication and send a message of peace and understanding."

Rodman also has connections to the president. He was a contestant on Trump's "Celebrity Apprentice" in 2013. And, while Rodman is an infrequent tweeter, one of his more recent re-tweets is one from Trump in 2014, who accused the basketball legend of being "drunk or on drugs" for saying Trump wanted to travel with Rodman to North Korea. "Glad I fired him on Apprentice!" Trump added.

Dennis Rodman was either drunk or on drugs (delusional) when he said I wanted to go to North Korea with him. Glad I fired him on Apprentice!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 8, 2014

Perhaps the re-tweet was a way for Rodman to demonstrate how full circle this moment is for him. On an individual level, Rodman has clearly been fascinated by North Korea and engaged in informal diplomacy for quite some time. And, in many ways, he has received significant flack for it.

But, now that Trump is onboard – and the summit next week represents the first of its kind between a leader of North Korea and a sitting U.S. president – does Rodman wonder if he will be seen as an innovator?

Still, Trump and those around him maintain that Rodman will not be involved. Rodman is "great on the court but negotiations should best be left to those who are good at it," White House Deputy Press Secretary Hogan Gidley told Fox News on Thursday. "President Donald Trump is the best. So we expect he and Kim Jong Un to have an amazing conversation without Dennis Rodman in tow."

How Bitcoin made right-wing conspiracy theories mainstream

AP/Getty/salon

When Bitcoin first came into existence, it was a definitively fringe idea, boosted by libertarians and paranoiacs who had a deep mistrust of the government and generally far-right (even anti-democratic) beliefs about society. Now, Bitcoin – and cryptocurrency in general – has moved from the fringe to the mainstream: Startups that do something with “crypto” have become a hot trend in Silicon Valley, while the number of cryptocurrencies numbers in the thousands. Many on the left and right talk earnestly about the potential for blockchain applications – including its potential for secure voting; meanwhile, big-name websites, including this one, give readers the option of donating their spare processing power to help pay for journalism.

Yet the extent to which cryptocurrency applications have entered mainstream politics belies its right-wing underpinnings. Virginia Commonwealth University Professor David Golumbia, who recently published a book "The Politics of Bitcoin: Software as Right-Wing Extremism," is blowing the whistle on the kinds of far-right ideas and conspiracy theories that not only inspired cryptocurrency's creation, but which are now trafficked, sometimes unknowingly, by many cryptocurrency boosters on both the right and left.

I spoke with Professor Golumbia about the far-right background of Bitcoin and how crypto is helping to normalize some of the more fringe aspects of right-wing thought. This interview has been condensed and edited for print.

In your book, you mentioned that the people who helped create cryptocurrencies had really far-right beliefs about society. I was wondering if you could just talk briefly about the sort of right-wing underpinnings and the people who built it.

Absolutely. There are these two overlapping groups of people, most of whom were in Silicon Valley in California in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. One of the main leaders of them was a guy named Timothy May who was, I believe he was a chip designer at Intel who became rich through his work and retired with a large pot of money. He formed this thing called “the Crypto Anarchist” in the late 1980s, early 1990s, which was basically a mailing list.

There was another guy named Eric Hughes, who was a friend of May's, and he started an email list called Cypherpunk, which was modeled off of “Cyberpunk,” which was the name of a kind of science fiction that seemed to anticipate a lot of what was happening. Hughes went on to be one of the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

The two of them wrote these manifestos that were all about how government was the most evil thing that ever happened and taxation was the most evil thing that ever happened, and Crypto – which they loved – encryption technology was the new weapon that was going to allow them to tear all this stuff down.

It’s true that there are some leftist anarchists, but these were not leftist anarchists. May himself has turned out to be a pretty racist, sexist, very disturbing guy. They were the center of a certain kind of hacker, radical, extremely aggressive form of thought. Back then, the mailing list was very popular.

A lot of people whose names are known to us now were part of these. One of these mailing list members was Julian Assange. He’s probably the most famous one. Assange was kind of more moderate politically than some of the people who were on the list. You can go back and read their manifestos and they are similar to the Tea Party, really. They hated everything about government, everything about democracy. Timothy May, in particular, in the very earliest versions of these manifestos, he talks about the need for some form of cash that is outside of the state system. This has been their goal. He thought that developing this would allow them to tear apart the state. He actually thought somehow that cash outside of the system would be so untraceable that the government wouldn't be able to tax it. Government revenue would dry up because everybody would use this alternative form of cash.

That's one of the places where you see an early Bitcoin discourse, a lot of people seem to believe that you couldn't possibly owe taxes in it because it's outside of the state system. You can get these great reddit threads where you get tax accountants on there who will tell you, “Look, Bitcoin is an asset, you sold it you made a profit. Doesn't matter what asset you sell and make profit on. You owe taxes on it.” It’s like selling a bike, or a painting.

Anyway, Hughes and May and Nick Szabo, and a lot of other people whose names you still see around Bitcoin forums, they crafted version after version of different forms of digital currency. These projects often incorporated the word “gold” into their names, so there was like, “digital gold” and “e-gold.”

They were all pretty lame projects, and of course they all were shut down because they were immediately used by people for illegal activities. Bitcoin is like, iteration 12. I think most people suspect that whoever Satoshi Nakamoto is, he is probably one or more of these people because this is the project they've been working on forever.

I should note that in the book, I'm pretty specific about what I mean by right-wing extremism and very specific conspiracy theories and how those tie into other forms of right-wing thought. Since I wrote the book, actually, you can see how certain people on the right — who were not part of the original group of cryptocurrency advocates – have really taken to cryptocurrency. Now you have actual Nazi groups being in favor of Bitcoin. Weev, one of the biggest Nazi leaders worldwide is into it. There's a great Twitter account that tracks Weev’s Bitcoin wallet, every transaction coming out of it. People like Richard Spencer and even [Peter] Molyneux and other big Bitcoin people, other big "alt-right" people, have gotten all over Bitcoin.

The actual connection between the far right and Bitcoin [has], if anything, become clearer and strengthened since I started writing.

When you put it all in context, it is kind of fascinating just how much so many people who consider themselves liberal or even leftist are enamored of Cryptocurrency; it's kind of surprising. I would be very suspicious of it if I went into it knowing all of that.

Most people don't know the history of it, which is completely understandable. When people want to advocate it for their own political projects, then I think they owe themselves to do some more investigation of what's going on. I mean, can Bitcoin be used for leftist projects or for non-far right projects? I guess you can make $10,000 off your trading and go give it to some cause that you believe in. I don't know what that proves.

What inspired you to write this book? Was there like an "ah ha" moment?

Well, part of it was that I worked for about 10 years in the financial technology sector on Wall Street. In order to do that, you really have to teach yourself finance. One thing I learned at that time was that there are all these conspiracy theories that lurk around the edges of finance — many of which have to do with gold and some of which have to do with the Federal Reserve.

When Bitcoin started to get big, I started to notice that the old conspiracy theories that I recognized from Wall Street were starting to show up with alarming regularity in the discussions around Bitcoin. People were taking them seriously in a way that was surprising to me, in the sense that they didn't have that much traction in the technology world or anything before that, and all of a sudden here they were in the mainstream. And the more I dug, the more I found them.

What are some examples of the conspiracy theories that are embedded in the discourse around Bitcoin and cryptocurrency?

I would say there are three that are really interesting, and they're connected. Two of them have to do with gold and the nature of gold, and especially what the gold standard is and the nature of the Federal Reserve.

In the case of the gold standard, there is this very odd conspiratorial belief that anchoring the value of currency to an underlying asset like gold somehow guarantees the price of the currency in a special way that you can't get otherwise. The history of metal standards is fascinating, but you don't have to dig far into that history until you see these competing strands of ordinary criticism of them and back and forth about whether we should have them, and then these conspiracy theories about, "they want to get us off the gold standards, because they want to take all our precious metals away." These have been going on for hundreds of years. Especially in the 19th century the U.S. used to have a dual metal standard, silver and gold. When we moved to the gold standard, it was thought that the Rothschild banking family controlled all the silver and they were somehow moving us off the silver standard because they were all going to get rich. So you had all these anti-British, anti-Jewish conspiracy theories then.

What exactly a metal standard does to a currency is the really fascinating question. It's really complicated. Partially, it has an element of arbitrariness in it, which is exactly what the people think they're getting rid of. At some level, you have to decide gold is going to be worth X, and its value is going to be related to the currency in some kind of multiplier, and that's what's actually gotten us into trouble. For 30 years or something, the U.S. used to just declare what the value of gold was relative to the dollar, and it wasn't really the value that gold traded on the market, so that created all these really insane incentive all over the world. It's just a mess — the gold standard doesn't fix anything.

On Wall Street you see people trying to sell you gold — there's just a constant stream of advertisements for people who are like, "The dollar is about to be devalued. The stocks are about to crash down to nothing. You should buy gold instead because that's where your value is going to be stable." They never tell you, “Here's a chart of the price of gold over time,” which wobbles just about as much as everything else does. It doesn't really do what it says. That’s a broad and interesting conspiracy theory that you see in the cryptocurrency community.

Then there's the Federal Reserve conspiracy theory, which is much more directly an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory — it has to do with central banking, which is a longer story.

There was an element of truth to the idea that at one point in time central bankers were also the people who owned the real banks and might be personally profiting off some of what the central bank was doing as far as monetary and fiscal policy. Those days are long gone. The Federal Reserve is a tightly regulated organization. You cannot be an officer of the Federal Reserve and personally profit in any way from the kinds of moves that the Federal Reserve does. The Federal Reserve does not print money, which is something we read about all the time.

There's a very familiar anti-Semitic trope in there that they're these evil greedy bankers who are manipulating the public in order to make themselves rich. I should be careful because I've been criticized sometimes for this before. I am not saying the Federal Reserve is beyond criticism. Like any other agenc[y], it deserves to be criticized. I'm not sure of its policies or other central policies are good, but it is not a cabal of evil like “corrupt bankers" who are manipulating all of these world events.

Then the third one, which is in many ways more interesting, is this idea about the nature of inflation. This isn't quite a conspiracy theory so much as a really interesting part of extreme right-wing economic thought that kind of blew over into conspiracy theories. When most economists talk about inflation, what they mean is the prices of goods have gone up — so it's harder to buy a car or whatever because a car costs more money than it used do.

One of the causes of inflation clearly can be “printing more money.” If you start to put a lot of money into the economy, you double the number of dollars, then in general the likelihood is that a dollar will buy half as much as it bought before. That is definitely a way to create inflation. If you really read the economy, that is one way that inflation can happen, but it is not at all the only way that inflation can happen. Inflation happens for all kinds of reasons.

[Right-wing economist] Milton Friedman liked to say that inflation was only caused by printing of dollars, which is just a sort of ideological view that is not connected to reality. Where it turns into a conspiracy theory relative to Bitcoin is that now you see this reinterpretation, where what inflation actually means is the printing of additional [cryptocurrency] tokens, and therefore the price of things is irrelevant to inflation. It’s enough to make one’s mind boggle, but you can observe this belief at play in arguments with Bitcoin people, as I often do.

What happened between January and right now is that the price of Bitcoin went from $20,000 to about $7,000 in U.S. dollar terms. It lost over about two thirds of its value. Depending on how we calculate it, that is something like 300% to 400% inflation, right? What you can buy with a Bitcoin decreased a huge amount. You need a lot more Bitcoins to buy the same thing that you needed to buy. That is, in half a year, Bitcoin inflated by hundreds of percentage points.

But when you get into arguments with Bitcoin fanatics, they will still say, even right now, “Bitcoin is a ‘Store of Value’ unlike the U.S. dollar . . . Bitcoin is safer for your money.” And if you say to them, "What are you talking about, Bitcoin inflated hundreds of percentage points in a time when the U.S. dollar hardly moved at all?" They will say, "What do you mean? Only a few more Bitcoins were mined in that period of time. That's nothing." It’s a misinterpretation of inflation that is mind boggling.

It does connect back to that first thing about gold, because there is this weird idea that money is this very concrete thing that you should be able to understand very quickly and easily. Money is actually incredibly complicated to understand. What is money? How does money work? It is a really tough subject and I'm sympathetic — like, I wish this was simple and I could just point at gold and that I could determine the value of my money, but it just isn't like that.

In your book you talk about the definition of currency and how Bitcoin might not actually qualify as a currency. Can you tell me more about that?

This is part of what is so complicated. Let's say currency is a token of some sort that somebody issued that is usually tied to the value of money.

It makes me think of, like, when you go to play arcade games or skee-ball, and you can't actually put quarters in it, you have to trade your quarters in for tokens or something. The skee-ball token technically is a currency, right?

It is technically currency and it has an equivalent value in money — but the only way we have to perceive money is in terms of national currencies or other currencies. That's part of why it's so hard to get a handle on. It is this abstract thing that it's really difficult to process. From the moderate right all the way to the left, the general accepted definition of money is that it has three functions: the “store of value” function, the “medium of exchange” function and the “unit of account.”

In general, currency is mostly about the “medium of exchange” function. The medium of exchange function means you can use this token to buy and sell stuff.

The unit of accounting has a little bit more to do with, like, it's a way to set prices for that stuff.

The store of value [is] more interesting. The idea of the store of value is that the token should be relatively stable over time with regards to markets. You should be able to sell some of your goods in May and put your proceeds in money in the bank or under your mattress or whatever, and a year later, you should be able to get relatively the same amount. You go back to your pile of stuff that you got, and it should be worth about the same thing that it was worth a year ago. It needs to stay almost identical.

Bitcoin is designed not to do that. In many ways, it is designed to rebuke that as a quality of currency. The Bitcoin people have tried to redefine “store of value” to mean “goes up over time.” That is just absolutely not what store of value means, because it's not storing. Even though going up sounds great, as people like me and a lot of economists have said, something that goes up is also going to go down. There is no such thing as a financial instrument that just goes up. It might look great while it’s going up, but it's not going to look great when it’s going down.

It is very interesting to argue with people over this definition of money because it isn't a prescriptive definition of money — it is a descriptive definition. This is people looking at how currencies and economies have operated over history and then they sort of said, "Okay, these are the three things that everything that functions as money seems to have."

You can't argue with a descriptive definition, unless you're just really playing games with words. We are the state-loving bankers that we say, “Look. It can't be money.” They sort of backed away from this money claim in part because Bitcoin is being so little used as a currency and that's the most obvious sort of money-like function and nobody wants to use it for the obvious reason, that you can't keep your goods in it. You can't keep your proceeds, you have to swap in and out of it almost instantly. That turns out to be an expensive transaction a lot of the time.

One of the most horrifying things you note in the book is that many Silicon Valley luminaries, Marc Andreessen and others, parrot many of the same far-right language and conspiracy theories that are embedded in the politics of Bitcoin when they talk about Bitcoin. It's like they may not realize that they’re doing it. What is going on here?

I wish I understood this better. I remember Andreessen wrote a piece in The New York Times many years ago, called “Why Bitcoin Matters.” Some of the finance parts were a little more tethered to reality, but there were a lot of conspiratorial moments. Myself and a few friends were actually engaged with him on Twitter and we were like, “some of the things you're talking about could only happen if Bitcoin became the only currency in the world and that is clearly not going to happen.” I don't think he recognized the conspiracy aspects of it, necessarily. His partner Ben Horowitz is way more into these conspiracy theories than Andreesen even is. [Twitter CEO] Jack Dorsey recently said he thinks cryptocurrency is the wave of the future, and he's getting into it.

Let me give the sane version of that. It's very clear that if you are going to be a financial technology company or even a financial company right now, you have to have a team that is working on blockchain or cryptocurrency in some way or another. That's because consultants and the vice president and everybody, they want to know what your blockchain strategy is. That's dumb, but it's understandable, and I'm sure that people will come up with some very interesting but non-revolutionary uses for some part of the technology that way. Those people, they needed to work within their own empirical testing environment.

That's fine, but they don't go along with all the crap and stuff where you do see the venture capitalist, some of the technology leaders and some of them . . . Andreessen Horowitz is a company that at some level must pay very close attention to financial systems. They’ve got to understand some of the fundamentals of finance and you really . . . it's hard not to wonder if they're kind of knowingly peddling some of this stuff, knowing that it is really not true. I definitely see that in the initial coin offering phase. I think a lot of those products, so to speak, were very, very specifically developed and promoted by people who absolutely knew that this was a quick way to rip off some people, and it would not produce at all what people were expecting it to produce.

One of the chapters in your book deflates some of the myths about blockchain’s potential. It seems like there are some people who may be skeptical about cryptocurrency, but they think blockchain is a cool and interesting idea — you talked specifically about “smart contracts” for instance, meaning digital contracts that use blockchain to enforce contract rules without a notary.

I think one of your major points was there’s kind of some rhetorical trickery going on in the way people hold up, say, smart contracts as being decentralized or autonomous — meaning, those are buzz words that maybe sound good, but they don't mean that much.

They don't mean that much, and they often prey on some deep and very hard-to-examine beliefs that people have. I mentioned some pretty well-known conspiracy theories, but I started to wonder if when people use the word like “middle man” that isn't at some level a kind of conspiracy theory — I mean, in the context of Bitcoin. They're saying we need to “eliminate the middle man” and it will be this great thing . . . it's probably not true, but it's definitely rallies people to your site because they're like, "Oh, that horrible middle man, we need to get rid of them.”

Certainly there are probably some industries where there are intermediaries who make some money off transactions that is not really necessary, maybe they aren't really adding value to the system. Blockchain, or some other technology, might be able to replace those. I think that's correct. But that is a big step from the sort of political promises that the blockchain boosters make.

Also, the “smart contract” thing is a political promise. I think a lot of it is hinging on words — it was [one of the first people who thought of the idea, legal scholar] Nick Szabo called it a “smart contract.” That makes people think a “smart contract” is the same thing as a contract between human beings, which it’s not.

Of course, Szabo called it that because contracts play a really important role in right-wing political philosophy. It's the only legitimate way of coordinating activities between different people. Without a contract, everything else is invalid in their view.