Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 344

August 1, 2017

Salon’s author questionnaire: Inside Tom Perrotta’s “Mrs. Fletcher” and more summer must-reads

Mrs. Fletcher: A Novel by Tom Perrotta; Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult by Bruce Handy; The Hot One: A Memoir of Friendship, Sex, and Murder by Carolyn Murnick

For August, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: Alex Gilvarry (“Eastman Was Here“), Bruce Handy (“Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult“), Carolyn Murnick (“The Hot One“), Tom Perrotta (“Mrs. Fletcher“) and Shawn Wen (“A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause“).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Tom Perrotta: Identity, sexuality, internet porn, gender fluidity, college hijinks and midlife melancholia.

Alex Gilvarry: Love, ego, sex, breaking up, infidelity, getting back together, more infidelity.

Shawn Wen: Movement, expression, death, the body, evasion, obsessiveness, materialism, pomp and sad clowns.

Bruce Handy: Discovery. Delight in discovery. Finding beauty, wit, insight and occasional shocks where you might not have thought to look. Secondary theme: being amused by some of the horrible things our ancestors liked.

Carolyn Murnick: Female friendship, patriarchy, sex, loss, media narratives, the myth of closure, growing up, definitely not Ashton Kutcher.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Murnick: “The beautiful dead girl” trope, Adderall, my first writing group, Los Angeles, 9/11, my second writing group, bike commuting, Tinder, my third writing group, lattes, 109th street, leggings as pants.

Handy: The fascination of dog parties. The longing for transportive tornadoes and snowy, backless wardrobes. Klickitat Street. A dead spider. My second-grade teacher, Mrs. Anastasia. My fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Brown. My children, Zoë and Isaac. Bedtime.

Wen: VHS tapes, the Bible, radio, old men, egotism, creeps, makeup, distance, walking around Paris.

Perrotta: Amateur porn, Fountains of Wayne, “Freaks and Geeks,” Facebook, Prince.

Gilvarry: A lot of movies. American films of the 1970s like “Midnight Cowboy” and “Kramer vs. Kramer.” Tu Do Street and the Continental Hotel, back when it was Saigon. All overcrowded Southeast Asian cities, for that matter. Old photos of Times Square back when it was an ashtray. Music of this period too, Country Joe and the Fish, CCR. John Fogerty belting out a wail.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Gilvarry: Massive breakup, then crack-up. Career crisis. Started smoking. Five years quitting smoking. Develop Alopecia, visible hair loss on face and head. Healing. Mask in book.

Handy: “The Sopranos,” “Mad Men,” “Breaking Bad,” “Girls,” “Stranger Things.” A day job. Tuitions. Two presidential elections. A long gestation/writing process, many distractions. Bad cats.

Wen: Traveling alone, a sprained ankle, uncertainty, death of a friend, feeling seen, sex, purchasing my first bottle of perfume, the recession, learning to let go a little, learning to cook, long nights in bars with friends.

Murnick: Turning 30, working at New York magazine, aging out of Williamsburg, Mad Men, Instagram, friends having kids, avocado toast, rompers, friends leaving New York, turning 35, finding love, cohabitation, home ownership, midi-length dresses, Hillary’s campaign.

Perrotta: TV show. Empty nest. Venice Beach. Involuntary AARP membership.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Wen: I wouldn’t say “despise,” but I cracked up when a reviewer called my book “whimsical.” It opens with the Holocaust.

Perrotta: Bubbly, frothy, effervescent — anything that sounds like a soft-drink commercial.

Gilvarry: Unsympathetic, preening, flat affect, wan. This is all from one Kirkus review. Who says “wan”? Tell me.

Handy: “Breezy.” “Snarky.” “Plangent.” (Okay, two out of three.)

Murnick: “Honest,” or even worse, “brutally honest.” Because, 1. How would they know? and 2. it feels like a weird memoir catchall term that’s shorthand for someone thinking what you’re revealing about yourself is unflattering, which, ok, but what does that have to do with the work?

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Handy: Mid-century jazz or jazz-pop singer. I wish I had Nat “King” Cole Jr.’s voice, or Frank Sinatra’s. Can you imagine opening your own mouth and having that come out? I’d swap sexes to sound like Sarah Vaughan or Dinah Washington. Doris Day! Also, when you hear a great jazz singer it so often sounds effortless — I know it’s not, that there’s all kinds of craft and apprenticeship and discipline involved — but I love that sense of ease combined with command that a lot of singers project, that sense of refined spontaneity. Those qualities are on my wish list for my prose, since no one is letting me into Capitol’s Studio A anytime soon.

Wen: Ceramicist.

Gilvarry: I want to run an interesting small business. My wife and I talk about opening a broth shop. Or books and broth. Or suds and buds, a beer bar and laundromat. Does that exist? Probably.

Murnick: Cheesemonger.

Perrotta: Big-city mayor.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Perrotta: Strong suit: Chapter Titles. Needs Work: Footnotes.

Murnick: I think I’m good at making compelling cliffhanger sentences at the end of chapters and sections that drive things forward. The hardest for me is structure. Throughout writing “The Hot One,” I never ended up developing my own color-coded note card/paper-clip and clothespin/dry-erase board flow-chart plotting system you always hear authors saying was their saving grace. Maybe next time?

Wen: I have an ear for dialog and the rhythm of a text. I’m good at collage, and so I rely on this technique a lot. I’m not great at rich, descriptive prose. I’m jealous of those winding sentences that you can get lost in. And these are only the craft elements within my lane: I have no idea how to start in on a work of fiction. Like, I wouldn’t know where to begin choosing a name for a character.

Gilvarry: I’m good at the ugly sentence. I can find humor there, beauty sometimes. Dialogue and plot — can write pages of that stuff. I would like to become less reliant on plots. It’s a novel so it’s not always necessary, yet I can’t help myself. Weaning off plot and working on discipline. That’s where I’m at.

Handy: I’m good at structure, at finding a narrative, whether it’s a literal, temporal one, or a conceptual one. My prose is lively and has rhythm. I can be thoughtful and entertaining at the same time. Bad: My desire/ability to entertain can veer into glibness. Easy jokes are a temptation not always avoided. I’m addicted to “not only . . . but also” constructions and other prose tics and rhetorical fallbacks.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Murnick: A woman telling her own story is a feminist act. The rest I don’t think about.

Wen: I don’t have this problem.

Handy: For me, hubris is a double-edged sword. Sometimes, I don’t think I have enough of it. I end up over-researching almost everything I write — not only because I’m procrastinating but also because it helps me create an illusion of mastery, which then allows me to proceed. At the same time, I strive to ensure that my writing is informed by the possibility that people might respectfully disagree with me, or worse.

Gilvarry: I begin to think of my writing as an entertainment, first. Like Graham Greene’s “entertainments.” Those are the books I like of his most. And the ideas and meaning will be there, within the entertainment, and the reader can take or leave them. I think the hubris comes in thinking that my ideas are very important. That’s the writer getting in the way of the story. Don’t do that. I try not to believe that my ideas and my language are too important. They are at the service of the story.

Perrotta: Salon asked me to fill out this questionnaire.

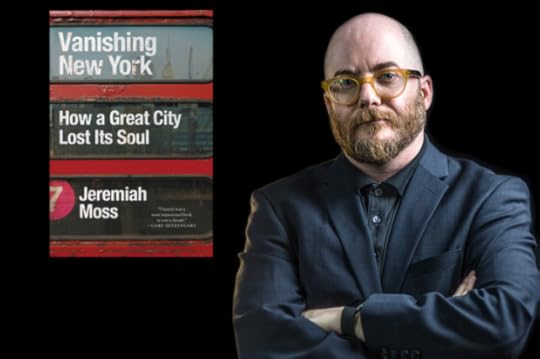

WATCH: Who benefits from gentrification?

Writer and cultural change observer Jeremiah Moss came to New York in 1993 and was immediately in love with the city. Ten years ago, he began to chronicle the dissolution of its character and the rise of gentrification on his blog Vanishing New York. He never thought anyone would read it, but they did, and now the entries have been turned into a fascinating book called “Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost its Soul.”

Moss sat down with me on “Salon Talks” to discuss how New York has changed for the worse and what can be done to stem the loss of both culture and neighborhoods.

Is gentrification ever a good thing?

When we talk about gentrification today, we’re really talking about this antique that doesn’t exist anymore.

What we think we’re talking about was something that existed in the ’60s, ’70s, and was described as this sort of quaint process where these middle class, mostly white people who moved into these divested neighborhoods, purchased properties, and fixed them up — properties that were maybe abandoned, in disrepair and already empty, largely. That’s not what’s happening now.

When we talk about the pros and cons — you know, yeah, lowered crime is a benefit for everybody, but the other benefits are not benefits for everybody, generally. We always have to ask who benefits from these changes — who benefits from the coffee shops . . . these new public spaces that are pedestrian plazas, that are really kind of quasi-privatized in some way? And who’s being policed out of those spaces, and who’s being made invisible? That’s the most important question.

Is there a more equitable future for New York and other large urban centers? What can we do to restore them?

Organize, and really look at the policies [of the city]. New York is the way it is because of policies. People will tell you “it’s the free market, and the free market takes care of it,” but the free market is not free. We know that there are billions of dollars going to developers and going to corporations . . . that needs to be reversed.

New York City used to have commercial rent control. A lot of people don’t know that.

If you say “commercial rent control” in this climate, people scream “Communist!” at you, or something. But, New York City had it once — why not bring it back?

Watch our conversation for more on the effects of gentrification.

WATCH: “First woman Marine to fly in an F-18 in combat” releases powerful campaign ad against Kentucky Republican

"Told Me" — Amy McGrath for Congress Announcement Video (Credit: Youtube/Amy McGrath for Congress)

Retired Marine Lt. Colonel Amy McGrath has announced her campaign against Republican Rep. Andy Barr for Kentucky’s Sixth Congressional District in a powerful new ad on Tuesday. McGrath, a retired fighter pilot, is fighting for Barr’s seat, and is seeking the Democratic party’s nomination for the congressional primary in 2018.

The ad, titled “Told Me,” highlights McGrath’s military service, a move that is reflective of the Democratic Party’s move to recruit more veterans to take back the House in 2018, according to Politico. “I just feel strongly that we need better leaders,” McGrath said in an interview about her campaign. “We need more people who care less about their own political future or career, and we need more people who have been public servants in other ways to run for office.”

McGrath’s announcement centers on the obstacles she overcame during her service, including her accomplishment of being the first woman in the Marines to fly in an F-18 in combat.

“When I was 13, my congressman told me I couldn’t fly in combat. He said Congress thought women ought to be protected and not allowed to serve in combat,” she says in the ad. “I never got a letter back from my senator, Mitch McConnell.”

“Then I got into the Naval Academy, and wouldn’t you know, that’s when they changed the law,” she continued. “I’m Amy McGrath and I love our country. I spent 20 years as a U.S. Marine, flew 89 combat missions bombing al Qaeda and the Taliban.”

In the ad, McGrath calls Bar the “hand-picked congressman” of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, while pointing to his enthusiasm to “take healthcare away from over a quarter-million Kentuckians.”

Barr has represented the sixth district of Kentucky since 2013. In 2016, Barr won his re-election bid by over 20 points, beating out Nancy Jo Kemper.

The ad was designed by Democratic campaign veteran Mark Putnam, who worked on Barack Obama’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns. But McGrath was sure to make clear that she was not recruited to run by party officials.

“I want to make that very clear. I was never recruited by the Democratic Party. I recruited them,” she told the Associated Press. “I believe that veterans running for office is good for the country in general, no matter what party.”

Watch “Told Me” below.

We shouldn’t trust tech industry billionaires to lead the way on immigrants’ rights

(Credit: AP/Paul Sancya)

Earlier this month, the administration of Donald Trump postponed the enactment of the International Entrepreneur Rule, a program that would grant foreign businesspeople the temporary ability to found companies in the United States. The ultimate goal, the administration announced, is to rescind the rule.

The move rankled the tech industry, which owes much of its plenitude to the work of enterprising immigrants. “Steve Jobs might never have been born,” many doting technocrats have ruminated, if his father hadn’t been able to come to the United States from Syria. AOL co-founder Steve Case lambasted the decision as a “big mistake,” and venture capitalist Bobby Franklin told the Los Angeles Times the development stems from “a fundamental misunderstanding of the critical role immigrant entrepreneurs play in growing the next generation of American companies.”

This sentiment is hardly new. Silicon Valley has a history of lobbying for immigration rights, which has culminated in a number of technocratic Obama-era bills, including the Immigration Innovation Act and the Startup Act.

Since Trump’s xenophobic ascent, however, the industry’s efforts to preserve its workforce have grown more visible, galvanized by the shock of such unprecedented threats to its talent as the travel ban targeting Muslim-majority countries. Tech titans condemn Trump while lauding immigrant technologists, parading their own potential to maintain the country’s diversity, boost its productivity and ensure opportunities for industrious immigrants in what have proven to be trying times.

Yet, when sifted through the Silicon Valley filter, immigration reform takes a disingenuous turn.

Among the tech industry’s chief targets is the H-1B visa, which allows U.S. companies to temporarily employ foreign workers in “specialty occupations,” such as engineering, medicine or accounting. Tech lobbyists have long implored authorities to ease H-1B restrictions, claiming concern over a dearth of domestic engineers.

It’s a hollow narrative. Valley elites aren’t so concerned with the aforementioned shortages, which are apocryphal, and — if anything — the result of the industry’s racism and sexism. They are more concerned with the opportunity to harvest the talents of young, STEM-educated people in Asian countries willing to work for significantly less than their U.S. counterparts. A study from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine noted that H-1B workers received “lower wages, less [sic] senior job titles, smaller signing bonuses, and smaller pay and compensation increases than would be typical for the work they actually did.” Additionally, the Economics Policy Institute reported earlier this year that the average Silicon Valley software developer earns $147,000 per year, while an H-1B software developer earning the entry-level wage is paid $102,000.

The conditions of H-1B visas often tether immigrant workers to their employers, furnishing technology companies with labor that’s not only cheap, but also immobile. Employers own and control H-1B visas, with many sponsoring their workers for U.S. permanent residency. The H-1B program, then, effectively sentences these workers to indentured servitude. Those who lose their jobs are instantly susceptible to deportation. As computer science professor Norm Matloff has argued, “though [foreign workers] have the right to move to another employer, they do not dare do so, as it would mean starting the lengthy green card process all over again.”

The consequences of Silicon Valley’s efforts extend far beyond working conditions, betraying a discriminatory, nakedly capitalist value system for immigrants. As techno-capitalists sing the praises of the “best and brightest” STEM-educated talent, they ultimately seek to protect only those immigrants who are trained to augment their own profits. In other words, they seek to support those with the wherewithal to not only earn a college degree, but also to parlay it into a revenue-generating, white-collar job.

In the eyes of the tech magnate, seeking refuge from war, poverty, or other imperialist abuses inflicted in one’s mother country is all well and good, but it alone won’t justify efforts to make a new home in the United States. To be deemed worthy, immigrants must show an ability and commitment to buttress a billion-dollar technology business — and to accept slashed wages in the process.

This conditional acceptance is linked to a principle that has long undergirded the tech industry: American exceptionalism. Couched within Silicon Valley’s reformist clarion calls is an exhortation to compete with other countries: Canada, Germany, South Africa, and China, all of which have sought to lure engineers from abroad in recent years. FWD.us, an immigration-reform group founded by such Valley fixtures as Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gate, and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, seeks to “keep the U.S. competitive in a global economy.” Tech and business pundit Vivek Wadhwa warns, “The country’s competitiveness is at stake now more than ever . . . we need economic growth and job creation and we need to welcome those who would bring about both.”

These calls-to-action again affix immigrants’ value to their ability to stimulate “economic growth” for a country and industry all too eager to exploit them.

Silicon Valley is right to oppose Trump, but its efforts are mere subterfuge. As the Democratic Party toys with a new slogan leading with the phrase “better skills,” the true fight for immigrants’ rights must reject the obsession with evaluating people on schooling and market contribution. Above all, we must recognize the rights of every person — regardless of place of origin or resumé — to live comfortably and safely and be accepted and valued—without fear of reproach for not knowing how to code.

Patriarchy and toxic masculinity are dominating America under Trump

(Credit: Getty/Rick Wilking)

Donald Trump’s election was a victory for toxic masculinity and patriarchy, two issues psychologist Terry Real has spent a career exploring. Since the 1998 publication of his groundbreaking book “I Don’t Want to Talk About It: Overcoming the Secret Legacy of Male Depression,” Real has been one of the most incisive voices on men’s issues, with an emphasis on the destructive effects of male trauma. With Trump’s ascension to the White House, Real sees the re-emergence of a dangerous form of masculinity with potentially far-reaching psychic and emotional consequences. He argues that recognizing and addressing our personal and collective trauma — much of which was inflicted even before Trump entered the political arena — is the only way to heal.

AlterNet publisher Don Hazen and associate editor/senior writer Kali Holloway sat down with Real to discuss the role of toxic masculinity in Trump’s presidential win; “blue” and “red” masculinity; the destructive notion of intimacy as a gendered trait; and the trauma created by psychological patriarchy.

Kali Holloway: Can we start by discussing what toxic masculinity is, how damaging it is and how exactly we got here?

Terry Real: Sure. About Trump — someone in the Trump campaign spoke to me off the record and said that every time Trump did something outrageous and the Democrats and liberals would be up in arms, [the Trump team] was happy because they would watch his numbers dip momentarily and then come roaring back. The chilling thought is that for at least a sizeable part of the population, Trump wasn’t elected despite his horrible misogynist behavior, but to some degree because of it, and that what America seems to be after is an old-style masculinity. Of course, men and women both can participate in patriarchy.

Let me say something about patriarchy. I distinguish between what I call political patriarchy and psychological patriarchy. Political patriarchy is very straightforward. It’s the oppression of one cohort, women, by another cohort, men. It’s about sexism. Of course, it’s still going on in America and all over the world. As a psychotherapist, what caught my eye was not so much the politics of sexism, but a dynamic that exists at the core of the patriarchal system that I see as a psychological dynamic, but I’d like to spell it out.

I like to think of psychological patriarchy as occurring in three rings. Think about it as three concentric rings, three processes. The first ring I call the Great Divide. It’s when you take the quality of your androgynous self — the qualities of one whole human being — and you draw a line down the center. You say all the qualities to the right are masculine, and all the qualities to the left are feminine. We all know what the breakdown is. It’s what [renowned family therapist] Olga Silverstein called halving, or the halving process. Halving a human being is intrinsically traumatic.

Don, as you know, this halving process is traumatic and is imposed by violence. If anybody dares to step outside of the box, the retaliation is swift. I have to say, after 50 years of feminism, the retaliation against “tomboy” girls has softened some over the years. The retaliation to “mama’s boys” and “sissy boys” is just as violent now among peers as it has always been. This halving process takes place whether you want it to or not.

The other thing I want to say about the halving process — when boys learn to suppress half of who they are — is that it takes place between the ages of three and five. It’s very young, almost preverbal.

The second concentric ring is what I call the Dance of Contempt, and that is simply that these in traditional patriarchy, these two halves of masculine and feminine are not held as separate but equal. The masculine qualities are exalted. The feminine qualities are reviled. The essential nature, the dynamic between these two halves, is contempt: contempt for the feminine.

Don Hazen: Contempt is one of the worst elements of any kind in a personal relationship.

TR: I agree. It’s like cancer. It’s toxic. That’s the dance of contempt.

The third concentric ring is one of the unsung great psychological forces in the world. It’s important to remember that the feminine side of the equation can be man, woman, boy or girl. This equation can play out between a man and a woman, but it’s not embodied; it can play out between a man and a woman, it can play out between two men, it can play out between a mother and a child, it can play out between two races, it can play out between two cultures, it can play out in your head.

The point is, whoever inhabits the feminine side of the equation has a deep compulsion to protect the disowned fragility of whoever is on the masculine side of the equation, even while being hurt by that person. Whoever is on the feminine side protects the masculine side from its own disowned fragility. You don’t speak truth to power. You protect the perpetrator. You protect power.

DH: Does that have anything to do with why so many women voted for Trump?

TR: Yes, I think that has a lot to do with it, in the sense that the offensive and perpetrating behaviors were minimized. But I think there’s a simpler answer, actually. I think that what has more do with it is a resurgence of the traditional vision of patriarchy, which is appealing to some, both men and women. To understand that appeal, I’d like to talk to you about a couple of apes, if I could.

You know the whole thing about the alpha male. Everybody’s heard about the alpha male who gets all the females, and the biggest and strongest and toughest gets access to mating. Well, that is a narrative that it turns out was spun by alpha anthropologists who were all male. When women were allowed into the field of anthropology, they discovered a very different kind of male. They call it, lo and behold, the relational ape, or the relational male. That male spends a lot of time grooming the females and is good with their kids and is a nice guy.

DH: Is this the beta male model?

TR: I don’t know what you would call it. We’ll call it “factor R,” for relationship. Anyway, it turns out that the relational male gets as many females as the alpha male does, and they take turns. It’s really very straightforward, and it doesn’t take Darwin to figure this out. In times of peril or scarcity, females tend to favor the alpha male. In times of prosperity and peace, females tend to favor the relational male.

What’s happened, if you have been alive on this planet, is that at 9/11 we were attacked on American soil, and that was trauma. Let me tell you about masculinity and trauma: I wrote an op-ed piece for the New York Times, which never got published, right after 9/11. I said there are two ways to respond to trauma. You can embrace your own vulnerability and deal with the reality of what happened to you and start to put it together piece by piece. Or you can deny your vulnerability and fly into grandiosity. The flight from shame to grandiosity is central to masculinity.

James Gilligan, [psychologist] Carol Gilligan’s husband, wrote a brilliant book 25 years ago called Violence. Jim was the medical director of Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane for 25 years. He writes about himself as a young resident going into this place for the first time. He says to himself, “If I can figure out the mind of a serial killer, I can figure out the mind of any violent person to the most extreme.” What he comes up with is the role of humiliation and self-esteem.

He tells the story of a serial killer who killed women, and usually upper-middle-class, attractive women. He would sew their eyes and sew their mouths. The analysis of this man revealed that there was a pivotal moment where some pretty young women of some prosperity were laughing at a street corner, and in his paranoia he imagined they were laughing at him. He was humiliated, and he righted his humiliation by closing the eyes that were gazing at him and closing the mouth that was laughing at him.

It’s this shift from inferiority to superiority, from inadequacy to attack, which is central to masculinity. I wrote in the piece, if we don’t deal with our trauma, we’re going to find somebody to go attack.

DH: It didn’t take long.

TR: It certainly didn’t. Women are no less prone to this than men are, but they’ll do it vicariously. In times of stress, they turn to that grandiose, powerful, strong, protective man, which Trump clearly positioned himself as being. His rhetoric was very clear about women needing to be protected. He says this explicitly, “And I’ll protect them.” The only difference is that apes don’t generate or amplify times of scarcity or threat in order to make a political point, but Republicans do. You exaggerate the “bad hombres” flooding in from Mexico, and you exaggerate the terrorist on every street corner. You generate the need for that strong alpha male, and that’s part of the machinery.

KH: Trump functions as a man in what you call the ‘one-up position,’ right?

TR: Yes. He’s one-up and boundary-less. You can be one-up and boundary-less, one-down and boundary-less, one-down and walled-off, or one-up and walled-off. Trump is one-up and boundary-less.

DH: What does it mean to be boundary-less?

TR: That he’s uncontained.

DH: Literally, there’s no constraints on him.

TR: Little to none. Certainly less than one would imagine. I’m writing a piece right now and tentatively titling it “Patriarchy Under the Age of Trump.” I start off by saying that as a family therapist, I’m preaching to the saved. You guys are already progressive, but as a couples and family therapist, I’m terribly concerned about the rise of traditional masculinity and traditional patriarchy. Not just in America, but around the world.

One of the ways I describe this is “an ill tide floats all boats.” There’s no surprise that with inflamed rhetoric follows violent actions. I think that traditional masculinity, or toxic masculinity, is dangerous. It’s dangerous to the man, and it’s dangerous to the people around the man.

DH: How much reemergence of this toxic masculinity has there been since Trump, or even before? Is this a trending thing, or is it always true?

TR: No. Ask the Republican baseball players [who were shot by a gunman in Virginia] whether there’s been a reemergence of this kind of toxic masculinity. The most extreme version of this masculinity is a gun.

There’s a great trilogy which has influenced my thinking enormously. It’s by a cultural historian, literary historian Richard Slotkin. It’s a cultural history of America in three volumes. The name of the trilogy, the name of the whole history of America, he sums up as “Regeneration Through Violence.”

DH: Wow. Powerful.

TR: I wrote about this in my book on men and depression, “I Don’t Want to Talk About It.” I wrote about the myth that you find in almost every boys’ adventure story or movie. The myth of the good man, the innocent man, who’s pressed to the wall unfairly. It’s Rambo just walking through town and getting picked on by people. It’s Dustin Hoffman in “Straw Dogs.” There are a million of them.

Somebody gets pressed. At first they don’t do anything, and then the worm turns. They pick up an Uzi and they start blowing people away. The audience cheers. This is a celebration of regeneration through violence, the central theme in masculinity, from one-down to the one-up.

DH: Which can be enabled by many people, including women and mothers, because everybody wants protection, right?

TR: You can have women who inhabit the masculine side of the equation, and you can have men on the feminine side of the equation. You can have women on the feminine side of the equation who buy into the alpha male and think that someone like Trump really will be strong and protect them, and that somebody like Obama was Hamlet-like and too indecisive and weak. That’s the narrative: Trump is a real man.

KH: For Trump’s base, this is the offending from the victim position.

TR: Yes. That’s from one of my mentors, Pia Mellody. Offending from the victim position is, “I’m your victim, you hurt me, and so therefore I have the right to hurt you twice as hard back. I have no shame or compunction about retaliating because I’m your victim.” It’s that righteous indignation, that righteous anger.

I believe that offending from the victim position accounts for 90 percent of the world’s violence. The rest is a scramble for resources. You killed my brother, I’ll kill your family. You kill my family, I’ll rape your grandmother. You rape my grandmother, I’ll burn down your village. And on and on and on. Yes, there’s a resurgence of hate crime, and yes, there is a continuing trend toward increased violence.

DH: Do you also find this true in male/female relationships: husband/wife, boyfriend/girlfriend? There just seems to be constant case studies of murder, of men stalking women they are in relationships with — finding them, shooting them and then often killing themselves.

TR: Yes.

DH: How does that dynamic work?

TR: Abusive men inhabit the same quadrant that I was just speaking about, one-up and boundary-less. They’re love dependent. One of the few characteristics that distinguishes a normal cohort of men from a cohort of abusers is increased sensitivity to the issue of abandonment. You show film clips and the batterers will pick out themes of abandonment much more readily than normal people. They’re boundary-less and they’re dependent.

DH: Are there biochemical things that go on when that abandonment happens?

TR: What being a love addict means is that you’re an addict. If the drug is flowing — and for a love addict the drug is the woman’s warm regard — if her warm regard is flowing, then I have warm regard for myself. I supplement my bad self-esteem for her esteem of me. When she separates from me or disappoints me in any way, I go into withdrawal. I go into a crash, and it feels ugly to be in that crash.

DH: We’ve all experienced that.

TR: We have. It feels dark and jagged and cold and lonely. When you’re one-up and a love addict, you have about two seconds’ worth of tolerance for those feelings, and then you go up from shame into grandiosity. You bounce up into grandiosity. Now you’re an angry victim. Now you’re a self-righteous victim. Now you’re a revenging angel, and you’re going to get that mother.

I write about this extensively. The problem with shifting from shame into grandiosity is that it works. It’s a great self-medicator. It takes away the depression, takes away the impotence, rights the injustice, does it all. It will create utter havoc in your life, but it does pump up your flagging self-esteem. And so you lash out. Then there’s remorse and shame, and the cycle just continues.

DH: What do you imagine is going to happen going forward, assuming Trump continues to be president and act in the ways he does, looking for wars, destroying people’s safety nets, the kinds of things we’re increasingly aware of. Are we going to see more and more of this kind of masculinity? Is there an antidote for it?

TR: I really feel, what is absolutely not in doubt is that we’re at war. There are two halves to this country. There is a blue masculinity and a red masculinity and they don’t get along.

DH: I’ve felt that so many times, but I’ve never quite heard it expressed that way. In fact, one of the things that seems to be Trump’s most potent weapon is to demonize us, make fun of us, poke at us.

TR: Yes. One of the things that he’s tapped into, as several people on the left have written about, is the humiliation of that group at the hands of our contempt for them for years. These are the deplorables. These are the unwashed masses. We have been elitist. We’ve been culturally elitist, and we have looked down our noses at them. Meanwhile, they’re struggling to put food on the table, and they don’t like it.

DH: Do you see any relationship between the opioid crisis and the toxic masculinity crisis?

TR: I do, for young people in particular. Not in Europe or Mexico or South America or Canada do young people, college-age people, get together and socialize by getting shit-faced. That’s not how it’s done in other countries. I think the reason why our young people socialize through extreme intoxication is because they have trouble relating to each other and they have difficulty knowing how to be with each other without getting smashed. They learn over time. Millennials are a mixed bag. I have great faith in the millennials. They will take over, and that Trumpian masculinity will decline when they do.

Millennial men are hands down the most gender-progressive men on the face of the planet, for all their narcissism and all their immaturity. Part of it is economic. Millennial men expect that they’ll be dual career families. They expect that the women will work. They expect to divvy up the housework. That doesn’t mean they always do it, but they expect it. They expect to share decision-making.

I’m writing a piece now about how we therapists cannot be neutral on this issue. We must stand for moving beyond these patriarchal norms. They’re bad for everybody. We know, for instance, that egalitarian marriages breed substantially greater rates of marital satisfaction and happiness, and that traditional marriages breed greater rates of anxiety and depression and dissatisfaction. We as therapists knowing that cannot say, well, you want a traditional marriage, you want a more modern marriage, this is a matter of opinion between the two of you. No, this is a matter of health.

DH: There’s a great book called “The Mirages of Marriage” about systems and relationships. And the secret was the quid pro quo — that if two people could agree that they were both treated fairly, whether one took out the garbage and the other did the dishes or vice-versa, that sense of equality was what kept the relationship going and solid. It’s when one person was exploited that the relationship failed mostly.

TR: Yeah. That’s a relational point of view, one of the things I teach people. It’s really something we’re all concerned about.

KH: We know what the wages of toxic masculinity are: shortened lifespans for men, and often covert depression. We also know more than 60 percent of white men voted for Trump. They’re also the people dying off at increased rates; they’re the only group that for a while there, was seeing increased mortality, often because of reasons that were self-caused: suicide, the kind of self-medication that leads to death. What does that mean, in terms of the kind of toxic masculinity being replicated because of Trump, for his base? Isn’t it likely to exacerbate that stuff among his supporters?

TR: It’s not even a question, absolutely. Trump has been at rallies and has said somebody should punch people’s lights out. I don’t know of more direct inciting than something like that. Absolutely.

It shows up in my office in terms of vulnerability. I had a woman in my office who was crying. She wouldn’t let her husband near her physically, sexually. Since the election, she’s just been in a state. It turns out her father was one-up and boundary-less, and maybe a sex addict, and was very sexual with her. [After the election] she just started crying, and I said, “You know, your father’s now in the White House.” She said, “I know. I feel so unsafe. I just feel safe in my own skin.”

DH: Wow. This is exactly what we’re talking about. (And what we’re writing about with our Trump Trauma project.) The men’s group I was in back in the early ’70s was set up so there was a women’s group that we had to meet with once a month to hold us accountable. We all thought that was great. But we discovered that the problem was we couldn’t be intimate with each other as men. That causes a lot of the sexism because as soon as you get intimate, you feel you’re becoming your feminine part.

TR: One of the great paradoxes is that in the rubric of patriarchy, intimacy is feminine. Closeness, relationship itself is feminine — it’s a chick flick, and we devalue it. We idealize it in principle and devalue it in fact, which is what we do with things we deem feminine. Yeah, you’re right there. Of course we have to learn to be vulnerable and talk to each other.

KH: The last time I spoke to you, you said something that stood out for me, which is, ‘So many men fear intimacy. I think that those men don’t actually know what intimacy is. What they fear is subjugation.’

TR: What they fear is being dominated. What they fear is being overrun. In the one-up, one-down world of men, you’re either in control or being controlled. So men don’t know much about what [author and cultural historian] Riane Eisler calls “power with.” Instead, it’s always power over, and you’re either up or down, one or the other. When women come in, particularly if they’re critical or controlling in any way, men are really phobic about that. They’re really paranoid about being controlled, and paranoid and phobic about being criticized, which doesn’t make them very good listeners.

There’s work that women can do about how to speak with more skill, to be honest. I talk to people in general and women in particular about what I call standing up for yourself with love; cherishing your relationship and your partner and standing up for yourself all in the same breath. It’s very powerful. I really am angry at my brethren in the therapy world, because all over America women drag men into therapy so that the therapist can make them more relational, more responsible, more open, and more open-hearted. The therapist, under the rubric of neutrality, throws the woman under the bus.

I know you are aware of [poet and leader of the men’s movement] Robert Bly. On YouTube, evidently somebody recorded a talk. Bly asked me to teach with him, and I went to Moose Lake. We did the drumming and the Sufi dancing and the whole thing, and I gave a talk to the men. Funny thing, you’re in these cabins in the woods, and whenever anybody would want me, Bly would say, “Get the feminist out here.”

I gave a talk to the guys. It was very well received, and I said, “Look, it’s great that we’re opening our hearts to each other off away from life and our families like this, but when we go home we have to treat our wives and kids well, and we have to bring this back to our families.” They really responded to that message. It was lovely.

DH: There are many millions of men who need to go through that experience. It’s too bad it’s not available to them.

TR: I talk to parents, in particular, about forming relationship subcultures around their families and generating the values that are relationship cherishing instead of relationship despising. This interview is part of that, and you guys are lights in that string of lights, so thank you for your work.

DH: Thank you. We need your inspiration and your analysis. A lot of us don’t fully understand this stuff, and it’s enlightening to have a theory that makes sense and is useful.

Why Trump’s threat to slap tariffs on foreign steel is a bad idea

Workers stand watch as containers are loaded into a cargo ship at Qingdao Port in Qingdao in east China's Shandong province, Thursday, April 13, 2017. China's export growth accelerated in March in a positive sign for global demand, though import growth cooled. (Chinatopix via AP) (Credit: Chinatopix via AP)

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump attracted a lot of support by promising to restore jobs to the American manufacturing sector.

One sector that has been hit hard by purportedly unfair foreign competition is the U.S. steel industry. It supported as many as 650,000 American workers in the 1950s yet now employs only about 140,000.

In order to restore American steel’s flagging fortunes, the Trump administration has been exploring increased tariff or quota restrictions on steel imports, citing national security concerns.

Trump upped the ante this month in an exchange with reporters on Air Force One:

“Steel is a big problem . . . I mean, they’re dumping steel. Not only China, but others. We’re like a dumping ground, OK? They’re dumping steel and destroying our steel industry. They’ve been doing it for decades, and I’m stopping it. It’ll stop.”

My research focuses on the politics of trade, including the use of restrictions like tariffs. A look back at the last time a president slapped tariffs on steel is illuminating for the current debate.

The Bush steel tariffs

Imposing steel tariffs is not a new thing.

In early 2002, then-President George W. Bush imposed steel tariffs of up to 30 percent on imports of steel in an effort to shore up domestic producers against low-cost imports. These tariffs were controversial both at home and abroad because, even as they helped steelmakers, they squeezed steel users, such as the auto industry.

They were also seen as hypocritical at a time when the Republican administration was trying to encourage other countries to liberalize trade policies — and reduce their tariffs — through the (now-foundering) Doha Round of World Trade Organization talks.

This case is instructive as to why President Trump may have a tough time imposing steel tariffs.

The general economic view of trade protection says that tariffs transfer money from a good’s consumers to its producers.

Let’s say a country slaps a 20 percent tariff on imports of beef. The country’s beef producers will be much better off because now imported meat is as much as 20 percent more expensive, meaning domestic companies will be able to sell more ribeyes and raise their prices. That’s bad news for restaurants and fans of steaks and hamburgers, who will pay those higher prices.

This transfer is usually economically inefficient because the benefits that domestic producers receive from a tariff will generally be less than the costs to domestic consumers. In the case of the steel industry, two economists found that the Bush policy would cost US$400,000 a year per steel job saved.

Despite the fact that imposing tariffs is economically inefficient, one of the reasons they still happen is that consumers are typically a very large and dispersed group. While they collectively may lose a great deal of money in higher costs from a tariff, the cost to any one individual may not be that great. Therefore, consumers are often less motivated in opposing trade protection than a relatively narrower and more unified group of producers who have a lot to gain.

Steel tariffs, however, don’t follow this pattern.

That’s because far from being broadly dispersed, steel consumers are heavily concentrated in the construction and automotive industries — which have very powerful political lobbies of their own. As a result, steel consumers are more likely to balk at the higher prices that would result from tariffs.

In 2002, it was pushback from these industries that helped persuade the National Association of Manufacturers to come out against the tariffs. Eventually the World Trade Organization ruled the policy illegal because it violated U.S. trade commitments, which led to the threat of a trade war with the European Union.

The Bush administration withdrew the tariffs in December 2003, about 21 months after they were imposed, but not without a cost. The Consuming Industries Trade Action Coalition found that 200,000 workers in U.S. manufacturing lost their jobs as a result of the tariffs.

The politics of trade

Of course, there are always competing voices lobbying for and against trade protection, and those preferences alone aren’t enough to push a protective measure into law. That depends on how effective an interest group is in working through the governmental process and winning the support of powerful political patrons.

Some of my own research has focused on this last step. Politicians have an incentive to get elected and reelected to office. Therefore, the differing electoral rules that a country has along with which constituencies are considered pivotal to getting elected will help determine which industry voices get heard when asking for trade protection.

In that vein, the steel industry has several things working in its favor. Trump has said repeatedly that he wants to protect American manufacturing squeezed by foreign competition, and U.S. steel certainly fits that profile. But more importantly, steel production is concentrated in old industrial states in the Midwest, such as Pennsylvania and Ohio. These states have been swing states in recent presidential elections, which gives industries with workers in those regions outsized influence.

The U.S. sugar industry, which is very heavily protected, benefits in a similar way from being heavily concentrated in Florida, a frequent swing state in presidential elections.

The flip side is that this opens administrations to accusations of playing politics with U.S. trade, as was the case with the Bush White House in 2002.

Will Trump roll the dice?

Despite the political advantages that the steel industry has working in its favor, protective tariffs would still be a large gamble by the Trump administration.

The ostensible justification for the tariffs is Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act. This law authorizes the president to impose tariffs on imports that jeopardize domestic industries deemed to be vital to national security.

While the WTO also allows national security concerns to be used as a justification for extraordinary trade protection, it seems unlikely that other WTO members will accept this reasoning. The Section 232 justification is probably a stretch in this case. Using the steel industry’s own numbers, only about 3 percent of domestically produced steel in the U.S. goes towards defense industries.

The impact of steel tariffs on other domestic manufacturers such as construction and automotive manufacturing is likely to be bad. However, the bigger concern would be that the WTO again rule such tariffs to be in violation of U.S. trade commitments. Such an event would likely touch off a trade war between the U.S. and its major trading partners, particularly the European Union.

That threat would have negative consequences for U.S. consumers and producers alike.

That threat would have negative consequences for U.S. consumers and producers alike.

William Hauk, Associate Professor of Economics, University of South Carolina

July 31, 2017

Jury sentences man to 137 years in jail for stealing tires

(Credit: Getty/chinaface)

In America, one can fatally shoot an unarmed black teenager without fear of repercussion, but steal expensive property and risk a century behind bars.

Proving once again how little black lives matter compared to pricey inanimate objects, a Virginia jury has sentenced Jason Brooks to 137 years for repeatedly stealing tires and rims over the past year. Brooks, who was tried in Loudoun County, reportedly faces similar charges in Maryland and New Jersey.

According to the Loudoun Times Mirror, reports of Brooks’ alleged crimes began in 2016. Multiple owners of trucks and luxury cars told police that they awoke in the morning to find their vehicles, which were parked in their driveways, propped up on cinder blocks with tires and rims removed. The car owners Brooks allegedly stole from live in one of the most affluent areas of the U.S. According to Wikipedia, Loudoun County’s median household income was $117,876 in 2012. The site notes that “since 2008 the county has been ranked first in the United States in median household income among jurisdictions with a population of 65,000 or more.”

Brooks was found guilty of “six counts of grand larceny, six counts of larceny with intent to sell, three counts of destruction of property and three counts of tampering with an automobile.” The jury recommended he receive a sentence of “132 years in prison, 63 months in jail and ordered to pay $6,000 in fines.”

The Mirror reports that Brooks has “two felony convictions for possession of a firearm by a convicted felon, assault and unlawful imprisonment.” Apparently, those crimes were not judged to merit more than 100 years in jail, while the theft of rich people’s tires and accessories were.

Brooks’ final sentencing date in the case is October 18.

Explaining the rise in hate crimes against Muslims in the US

(Credit: AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File)

Hate crimes against Muslims have been on the rise. The murder of two samaritans for aiding two young women who were facing a barrage of anti-Muslim slurs on a Portland train is among the latest examples of brazen acts of anti-Islamic hatred.

Earlier in 2017, a mosque in Victoria, Texas was burned to the ground by an alleged anti-Muslim bigot. And just last year, members of a small extremist group called “The Crusaders” plotted a bombing “bloodbath” at a residential housing complex for Somali-Muslim immigrants in Garden City, Kansas.

I have analyzed hate crime for two decades at California State University-San Bernardino’s Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. And I have found that the rhetoric politicians use after terrorist attacks is correlated closely to sharp increases and decreases in hate crimes.

Hate crimes post 9/11

Since 1992 (following the promulgation of the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990), the FBI has annually tabulated hate crime data voluntarily submitted from state and territorial reporting agencies. A “hate crime” is defined as a criminal offense motivated by either race, ethnicity, religion, disability, sexual orientation, gender or gender identity.

According to the FBI’s data, hate crimes against Muslims reported to police surged immediately following the terror attacks of 9/11. There were 481 crimes reported against Muslims in 2001, up from 28 the year before. However, from 2002 until 2014, the number of anti-Muslim crimes receded to a numerical range between 105 to 160 annually. This number was still several times higher than their pre-9/11 levels.

It should be noted that other government data, such as the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which relies on almost 200,000 residential crime surveys, as opposed to police reports, show severe official undercounting of hate crime. These studies, based on respondents’ answers to researchers, indicate a far higher annual average of hate crime — 250,000 nationally — with over half stating that they never reported such offenses to police.

FBI data show that in 2015 there were 257 hate crimes against Muslims — the highest level since 2001 and a surge of 67 percent over the previous year.

As I noted in a prepared statement before the Senate Judiciary Committee in May 2017, this was the second-highest number of anti-Muslim hate crimes since FBI record-keeping began in 1992. Not only did anti-Muslim crime cases rise numerically in 2015, they also grew as a percentage of all hate crime. They now account for 4.4 percent of all reported hate crime even though Muslims are estimated to be only 1 percent of the population.

When do the spikes happen?

At our center, we analyzed even more recent disturbing trends related to hate crimes. Based on the latest available police data for 2016 from 25 of the nation’s largest cities and counties, we found a 6 percent increase in all hate crimes, with over half of the places at a multi-year high. In particular, hate crimes against Muslims had increased in six of the seven places that provided more detailed breakdowns.

We also observed a spike in such crime following certain events.

In 2015, for example, we found 45 incidents of anti-Muslim crime in the United States in the four weeks following the November 13 Paris terror attack.

Just under half of these occurred after December 2, when the San Bernardino terror attack took place. Of those, 15 took place in the five days following then-candidate Donald Trump’s proposal of December 7, seeking to indefinitely ban all Muslims from entering the United States.

In contrast, as I observed in my prepared statement before the Senate Judiciary Committee, after an initial sharp spike following the 9/11 attacks, sociologist James Nolan and I found that there was a drop in hate crimes after President George W. Bush delivered a speech promoting tolerance on Sept. 17, 2001.Other groups too, have found similar spikes in anti-Muslim hatred: The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), for example, noted that from the month of the presidential election, through Dec. 12, 2016, there was a spike in hate “incidents” against many minority groups. The SPLC found that the third most frequently targeted group after immigrants and African-Americans were Muslims. And just this month the Council on American-Islamic Relations, a Muslim advocacy group, reported 72 instances of “harassment” and 69 hate crimes that had occurred between April and June 2017.

Fear of Muslims

Prejudicial stereotypes that broadly paint Muslims in a negative light are quite pervasive.

From 2002 to 2014, the number of respondents who stated that Islam was more likely to encourage violence doubled from 25 percent to 50 percent, according to Pew research. A June 2016 Reuters/Ipsos online poll found that 37 percent of Americans had a somewhat or very unfavorable view of Islam, topped only by antipathy for atheism at 38 percent.

The latest polls also show how Muslims are feared and distrusted as a group in America. While most Americans do not believe that Muslims living in the U.S. support extremism, these views vary widely by age, level of education and partisan affiliation: Almost half of those 65 and older believe that Muslims in America support extremism, whereas only few college-educated adults do so.

Interestingly, current polls also show that when people personally know someone who is a Muslim, the bias is much less. This confirms what psychology scholar Gordon Allport concludes in his seminal book, “The Nature of Prejudice,” that meaningful contact with those who are different is crucial for reducing hatred.

Indeed, before we can truly say “love thy neighbor(s),” we need to know and understand them.

Indeed, before we can truly say “love thy neighbor(s),” we need to know and understand them.

Brian Levin, Professor, Department of Criminal Justice and Director, Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism, California State University San Bernardino

Michele Bachmann: “The Lord is working mightily in our government” thanks to Trump

Michele Bachmann (Credit: AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster) (Credit: AP)

Former Minnesota congresswoman Michele Bachmann was a guest on Jan Markell’s “Understanding The Times” radio program this weekend, where she couldn’t stop gushing about President Trump and his supposed deep commitment to God and prayer.

Bachmann claimed that, since the inauguration,Trump has been “working nonstop, 70 days in a row, [he] hasn’t taken a day off” as part of his effort to make America great again and to take a stand for God.

“He is unashamed in standing up for increasing an awareness of God in the United States,” she said. “He recognizes how important that is and that that is a basis of Western civilization … As a believer in Jesus Christ, I could not be more happy with what I am seeing coming out of the Trump White House. This is beyond my wildest expectations.”

“The president himself is man of prayer and man who loves to receive prayer,” she cooed. “He is a man who, I do believe, understands who the God of the Bible is and he wants to lift up the God of the Bible here in the United States . . . The Lord is working mightily in our government and I believe it is because God is being reverenced, God is being lifted up. Prayer is not foreign in the White House, it’s not foreign in the Executive Office Building; looking to God, looking through Bible studies, this is not foreign anymore.”

Bachmann said that Trump deserves all the credit because “he is somebody who gets the fact that the God of the Bible is, He is, He exists, He is real . . . This president is very bold about the need for God in our country.”

Bachmann was among those who met with Trump in the Oval Office recently, where she said they were able to present “the faith perspective voice” to him and explain that enacting public policies based on biblical principles will “be the best for America.”

“I’m shocked at how happy I’ve been with what I’ve seen so far,” she said. “I really believe that it’s because of prayer. I totally believe it’s based on prayer. He’s president because of prayer, the advances we’ve seen are based on prayer and I think, going forward, that is what we need.”

Tick tock: It’s time to stop bullying 30-something women about their biological clocks

(Credit: Image Point Fr via Shutterstock)

“Get that thing out of you!” my boyfriend’s cousin exclaimed after learning about my IUD.

A few bottles of wine into celebrating the 40-something’s birthday at a casual-chic French restaurant, she had asked when I was “finally” going to have a baby. To drive home the point that I still wasn’t quite ready, I pointed to the 99 percent effective birth control device implanted in my uterus, which emits copper ions toxic to my boyfriend’s most determined little swimmers.

Of course, I recognized that her comment was born out of respect for my relationship with her cousin, and a sincere desire for us to experience the joys of building a family. Still, I wasn’t thrilled to receive yet another reminder that my biological clock is ticking. Every. Single. Second.

At 34, I’m on the cusp of that harrowing age so many widely accepted pregnancy statistics seem to hinge upon. Fear-mongering medical professionals, fertility specialists, advertisers, and well-meaning family members love to assert that 35 is the year a woman’s eggs instantaneously become less viable. If you’re lucky enough to get pregnant at such an advanced age, they all seem to scoff, the risks of miscarrying or giving birth to a disease-riddled child suddenly skyrocket.

Thirty-something women are constantly bombarded with infertility horror stories — snippet upon snippet of anecdotal evidence about friends of friends intended to demonstrate that if you wait too much longer, you’re destined to get fucked by Mother Nature. We’re shamed into believing that our limited supply of eggs might soon be entirely worthless, and urged to consider egg freezing — an intensive procedure that costs an astounding $10,000 on average — “just in case.”

I know this because I am a 34-year-old woman and I can’t seem to escape the dreadful feeling that if I don’t get knocked up in the next twelve months, I will miss my shot at carrying a pregnancy to term altogether. The other day I found myself staring at a bottle of prenatal vitamins at the pharmacy, seriously contemplating purchasing the overpriced gummies even though that IUD is still very much lodged inside me. In the last few months, I’ve Googled things like “How fast do a woman’s eggs actually shrivel up?” more often than I’d like to admit. You went through puberty four years late, so you must have more grade-A gametes than most females your age, I tend to coach myself while assessing my reproductive health with questionable Internet fertility calculators.

My 35th birthday looms ahead, taunting me with the promise of missed opportunities and lifelong regrets if I don’t spread my legs and invite some sperm in stat. And yet, more and more research demonstrates that popularized notions regarding women’s fertility are totally bogus.

In “The Impatient Woman’s Guide To Getting Pregnant,” Jean Twenge contests the widespread belief that one in three women over 35 will fail to get pregnant after a year of trying, noting that the claim is based on an analysis of French birth records dated 1670 to 1830. Luckily, medicine has made some pretty significant strides since the eighteenth century! In fact, about 80 percent of women aged 35 to 39 succeed in getting pregnant naturally today, a slight decline from the fertility rate of women aged 27 to 34. In a 2014 study published by the Boston University School of Medicine, researchers even discovered that women who had their last child at 33 or older without the help of drugs lived longer than those who had their last child by 29 — a correlation and not evidence of causation, necessarily, but a notable phenomenon nonetheless. And for those who have trouble conceiving, IVF treatments, though cripplingly expensive, are quickly becoming more effective.

I’m tired of the narratives we feed women about pregnancy. We caution young ladies that if they wait to procreate, they’ll face devastating setbacks down the line. We tell them that their bodies were built to carry babies sooner rather than later (i.e. now!). We say there’s “never a right time” to have a child — as if women should drop everything and get preggers regardless of how prepared they actually feel, financially, emotionally, or otherwise.

If the “right time” never arrives, is it so crazy to presume that a woman might not be cut out for motherhood after all?

I have a hard time understanding the value in pushing a woman into a decision as life-changing as becoming a parent. On the other hand, the downside to forcing someone into a role they’re not yet psyched to play — especially one that involves risking their life to host a parasite for nine long months of potential discomfort before bringing a super needy infant into the world — seems quite obvious.

Does anything good come out of reluctant motherhood? Perhaps. But I’d argue that it leads to a lot of bad, too.

If we could all agree to stop pressuring women, no matter how old they are, into baby-making, the truth is that the world be a much better place — for me, at least.