Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 339

August 6, 2017

I’ve been watching children learn how to lie

(Credit: Getty/FatCamera)

For the liar, telling a lie has obvious costs. Keeping track of the lies one tells and trying to maintain the plausibility of a fictional narrative as real-world events intrude is mentally taxing. The fear of getting caught is a constant source of anxiety, and when it happens, the damage to one’s reputation can be lasting. For the people who are lied to the costs of lying are also clear: Lies undermine relationships, organizations and institutions.

However, the ability to lie and engage in other forms of deception is also a source of great social power, as it allows people to shape interactions in ways that serve their interests: They can evade responsibility for their misdeeds, take credit for accomplishments that are not really theirs, and rally friends and allies to the cause. As such, it’s an important step in a child’s development and there are cognitive building blocks that must be in place in order to successfully lie.

One way research psychologists have sought to understand the reasoning behind the choice to lie versus tell the truth is to go back to when we first learn this skill in childhood. In some studies, researchers ask children to play a game in which they can obtain a material reward by lying. In other studies children are faced with social situations in which the more polite course of action involves lying instead of telling the truth. For example, an experimenter will offer an undesirable gift such as a bar of soap and ask the child whether he or she likes it. Yet another method is to ask parents to keep a written record of the lies that their children tell.

In our recent study, my colleagues and I sought to understand children’s thinking processes when they were first figuring out how to deceive other people, which for most children is around age three and a half. We were interested in the possibility that certain types of social experiences might speed up this developmental timeline.

Watching children discover how to deceive

We invited young children to play a simple game they could win only by deceiving their opponent: Children who told the truth won treats for the experimenter and those who lied won treats for themselves.

In this game, the child hides a treat in one of two cups while an experimenter covers her eyes. The experimenter then opens her eyes and asks the child where the treat is hidden, and the child responds by indicating one of the two cups. If the child indicates the correct cup, the experimenter wins the treat, and if the child indicates the incorrect one, the child wins the treat.

Children played 10 rounds of this game each day for 10 consecutive days. This method of closely observing children over a short period of time allows for fine-grained tracking of behavioral changes, so researchers can observe the process of development as it unfolds.

We tested children around the time of their third birthday, which is before children typically know how to deceive. We found that, as expected, when children first started playing the game most of them made no effort to deceive, and lost to the experimenter every time. However, within the next few sessions most children discovered how to deceive in order to win the game — and after their initial discovery they used deception consistently.

Just one developmental milestone

Not all children figured out how to deceive at the same rate. At one extreme, some figured it out on the first day; at the other extreme, some were consistently losing the game even at the end of the 10 days.

We discovered that the rate at which individual children learned to deceive was related to certain cognitive skills. One of these skills — what psychologists call theory of mind — is the ability to understand that others don’t necessarily know what you know. This skill is needed because when children lie they intentionally communicate information that differs from what they themselves believe. Another one of these skills, cognitive control, allows people to stop themselves from blurting out the truth when they try to lie. The children who figured out how to deceive the most quickly had the highest levels of both of these skills.

Our findings suggest that competitive games can help children gain the insight that deception can be used as a strategy for personal gain — once they have the underlying cognitive skills to figure this out.

It’s important to keep in mind that the initial discovery of deception is not an endpoint. Rather, it’s the first step in a long developmental trajectory. After this discovery, children typically learn when to deceive, but in doing so they must sort through a confusing array of messages about the morality of deception. They usually also learn more about how to deceive. Young children often inadvertently give away the truth when they try to dupe others, and they must learn to control their words, facial expressions and body language to be convincing.

As they develop, children often learn how to employ more nuanced forms of manipulation, such as using flattery as a means to curry favor, steering conversations away from uncomfortable topics and presenting information selectively to create a desired impression. By mastering these skills, they gain the power to help shape social narratives in ways that can have far-reaching consequences for themselves and for others.

Gail Heyman, Professor of Psychology, University of California, San Diego

Has queer culture lost its edge?

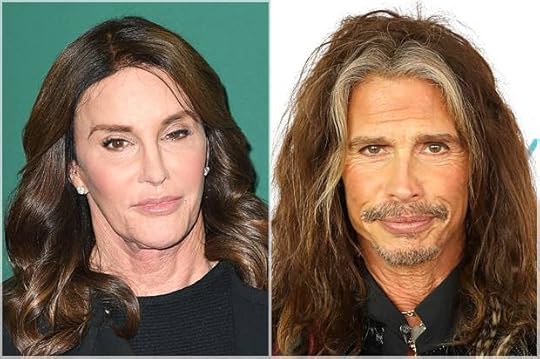

Caitlyn Jenner; Steven Tyler (Credit: Getty/Angela Weiss/Adam Bettcher)

Queer culture. Is it endangered? Gasping its last? Just sad? Consider the following.

Caitlyn Jenner, captioning a picture of herself posing with Steven Tyler, jokingly says that they are working on a duet of “Dude Looks Like a Lady”; apparently it was once her theme song, and she loves it. Huffington Post’s Queer Voices Deputy Editor James Michael Nichols critiques Jenner’s “almost too predictably problematic” use of this “dangerous” trope, as connected to a history of violence perpetrated by those who don’t consider trans women real women.

Students returning from an undergraduate queer studies conference tell me that they were deeply disturbed by a drag queen’s performance there because she made comments that were insensitive and triggering. I argue that it is the privilege of drag queens to ridicule, insult, and generally slay in all ways absolutely everyone in the name of humor — and that this privilege constitutes a moment of public power for a marginalized group. I say that there is empowerment in humor and in being able to take what the drag queen dishes out. They do not accept this explanation, failing to imagine how pointed insults could be acceptable in what is supposed to be a supportive community.

A non-binary student critiques a faculty colleague of mine in class for using the term “drag queens” to describe the self-identified drag queens who resisted at Stonewall. My colleague, who is 35, queer, and teaching Sociology of Sexuality, is informed that this is an incorrect and insulting term.

What do these examples have in common? What has become of us queers — and of our culture? Whose culture, you might ask? Well, mine. I am a white 49-year-old femme college professor whose sexual interest is butch lesbians and trans men. Yes — sexual. Not as in “partner,” like starting up a small business together. As in sex, as in “lover,” which is what we called our lovers before it all became so sanitized and proper. I came up in the ’80s and ’90s, when queer culture was hot because it was outsider culture, and I liked it that way. Queer culture, heavily dominated by gay men, particularly white men, and their concerns and aesthetics, from Tom of Finland to Judy Garland, was flawed, frustrating, even infuriating at times, and beautiful to me despite the marginalization of lesbians and trans people within it. It had glamour. It had glitter and leather and sex and history and laughter.

I liked the centrality of playfulness within this culture — the fact that we couldn’t take ourselves too seriously because, as with many marginalized groups, humor was survival. This was the era of ACT UP, of Silence = Death — an era of many specters, from AIDS to rampant alcoholism and drug addiction in our community to poverty, particularly for gender non-conforming people, queers of color, and lesbians. It was an era of suicides and murders, just like today. It was a time of no legal protection, of the demonization of bisexuals, of the invisibility of trans and genderqueer people, of lovers who were also called “friends” or “roommates” in dangerous circumstances. It was all these things — serious and terrible and terrifying — and yet it was also a time of joy, pleasure and celebration — a frisky, sensuous era of Pride symbols, drag balls, Dykes on Bikes, public sex. It was underground, and it was a risk in any case. It was a time for queens of all sorts in their outrageous, edge-pushing fabulousness. I believe that its special kinds of ecstasy were in fact intimately connected to its special kinds of marginalization, as forms of resistance. And if you didn’t have a wit, a sense of humor, then you didn’t get it. You just didn’t.

Queer culture today: Marriage wars. Custody wars. Bathroom wars. Assimilation. Rights. Sigh.

We deserve all the rights, obviously. We deserve to be who we are and who we want to be and not to be harassed or killed for it, and we deserve to have and keep our children and set up shop in the suburbs if we want. We deserve to pee in peace in the bathroom that suits our identity and serve in the military. Obviously. I myself have lived in fear as a parent with no legal rights. But. Apparently, in the pursuit of rights and respectability, we have somehow shifted as a culture from the celebration of eros to the celebration of victimhood — to comfortably inhabiting a state of being prickly and appalled — and apparently we now have to be and feel like victims in order even to deserve rights. This worries me.

Are we going to become so focused on our legal standing and our feelings, so invested in queer culture as a culture of rights, respectability and sensitivity, that we lose our playfulness and the toughness that used to define survival? Do we just not want to be tough anymore? Are we too emotionally exhausted, or just too bourgeois, to appreciate a classic bitchy drag emcee? Her sensibility was always at the cultural fringe — is there no room for it now? Or are we the truly bitchy ones, ever ready with the political upper hand raised to slap down those among us who still want to play around the edges, where things are a little less comfortable and correct?

“Dude Looks Like a Lady” is crude and transphobic and promotes straight sex tourism. It is also a song about a normative male protagonist’s being irresistibly attracted to a trans woman who “had the body of a Venus,” and having sex with her and enjoying it. It is complicated and contradictory. As a concept, the phrase “dude looks like a lady” is in fact in the neighborhood of classic drag, especially drag in the ’80s and prior, before “realness” became achievable or even desirable. Because the beauty of drag is illusion, a moment of lighting, smoke and mirrors — wigs, makeup, layers of hosiery, and what is underneath all of that — not seamlessness, not a lining up of all the facets of selfhood but rather a disruption of fixed categories as attached to the body. Looks like — if it’s not that, then it’s not drag. This is far afield from many of today’s queer identities, which hold up as their mirrors Truth or the Actual, though it is very true in what it challenges regarding bodies, genders and natures.

Steven Tyler’s song is ridiculous and dangerous indeed. It does not promote understanding of the complexity of queer identities but reduces genders to opposite and incommensurate extremes. But it is also interesting that Caitlyn Jenner loves it, because the word “dude” is not a measure of biology, of essence, but of masculinity, and maybe Caitlyn Jenner, formerly a major dude, has a right to play with masculinity and illusion. And what if this is how she identifies, or just how she feels? What if, becoming a woman, she has not been able to, or even wanted to, completely leave the dude behind, in part because she was famous first as a dude? Would anyone know who Caitlyn Jenner was if she hadn’t first been Bruce Jenner? Is it not alright for her to call up that history? Or to see her transformation in material terms — as being in part about the body and appearance, as about what gender “looks like?” Or . . . here’s a radical thought . . . to joke about something so serious?

And, more to the point than what she may or may not want: Not to give her too much credit, but what if her playing with this phrase publicly undermines its dangerous power? Or what if it acknowledges, however indirectly or unintentionally, a history of masculine privilege that she has not entirely shed? Plus, Steven Tyler looks like a lady too, with his sweet and lovely features, fancy mouth, smoky eyeshadow, luscious long hair, necklaces, and shirt-cut-down-to-there. Who is the real dude, and who the lady here?

Who cares? I do. Because my queer students are so fragile, so easily hurt, and I am worried about them — and not in the way that they want me to be. Because when I say to one of them, “Being a victim is not hot, and in my day a political platform based on being a victim would never have gained traction,” she seems startled but retorts that on the contrary, victimhood is hot, adding, “What about BDSM?” And so I explain that BDSM is not about being a victim, it’s about moving beyond and transforming victimization — for those who come to it that way — and it’s about destabilizing the grounds of victimization, through playing with power. Which is also what drag is about in its way. And I am shocked to find myself in the position of defending, to a queer, the value of hotness — as shocked as she seems to be at the idea that hotness could be the point of queer culture.

I don’t believe her. I don’t believe that she really finds victimhood hot, unless . . . is this a new fetish that is hopelessly lost on me since I’m almost 50? I won’t — I can’t — believe in the victim as the new face of queer culture. What were all those drag queens at Stonewall fighting for, anyway? If victimhood is hot, then we have lost.

Here’s the secret to raising a safe, smart kid

(Credit: Getty/dolgachov)

When it comes to parenting frustrations, nothing beats the challenges of setting screen limits, picking appropriate media, and figuring out Snapchat. We’re raising “digital natives” but we’re supposed to be the experts? Actually, no. It turns out, the most effective way to help your kid have a healthy relationship to media is by being their media mentor.

When it comes to parenting frustrations, nothing beats the challenges of setting screen limits, picking appropriate media, and figuring out Snapchat. We’re raising “digital natives” but we’re supposed to be the experts? Actually, no. It turns out, the most effective way to help your kid have a healthy relationship to media is by being their media mentor.

Many of us think we need to have all the answers. Or we just stick our heads in the sand and hope for the best. But, as so often happens, the middle road is juuuuust right. Researcher Alexandra Samuel surveyed 10,000 North American families and found that some parents put strict limits on what their kids could watch or play (“limiters”), especially when they’re young, while others (especially parents of teens) let their kids control screen time and embrace the idea that more tech is good tech (“enablers”).

But about a third of the parents — whom she calls “media — consistently engaged in media with their kids, despite their ages, and these kids had better outcomes. Kids of media mentors were less likely to access porn, chat online with a stranger, and impersonate an adult or peer online. Exactly what you’re hoping for as a parent, right?

So what does it take to be a “media mentor“? Here are the steps:

Talk about media and tech

Here’s where most parents are #winning. In the 2015 “Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens,” 87 percent of tweens reported that their parents regularly discussed Internet safety. These conversations can include everything from stranger danger to creating strong passwords and should be empowering rather than scary.

Play, watch, learn together

Media mentors play video games, watch movies, and download apps with their kids. They share their favorite YouTube videos and explore new music together. It’s not all the time, of course — who has time for that? — but staying engaged and showing interest breeds comfort and camaraderie.

Teach new skills

Kids with tech-savvy parents have some advantages when getting up to speed on digital life. They can introduce kids to specialized websites and explain the ins and outs of Instagram. But that doesn’t mean the rest of us have nothing to offer. Parents can show kids — especially young ones — how to use a mouse, do a Google search, charge a device, and so on. Children’s librarians are another tech resource, too.

Follow their interests

You know what your kid is into — whether it’s dinosaurs, “Minecraft,” or Taylor Swift — and you can use these interests to support positive engagement with media and tech. Find cool dinosaur apps, sign your kid up for a “Minecraft” coding camp, or take a digital music-making class together.

Do your research

High-quality content makes a difference in how kids interact with media. Parents who seek out good content by checking reviews, surveying friends, and exploring content themselves expose kids to better stuff.

Notes from a trailing spouse: A drive in the desert without my dad

(Credit: Shutterstock/Getty/Salon)

I am stepping into one of six vintage Land Rovers all lined up to take us desert-farers deep into the true heart of the UAE. My driver has wrapped a scarf around my head, and for a moment my shadow makes a credible impression of Lawrence of Arabia — or at least Peter O’Toole — as he flits around in his regal Arab garb until Anthony Quinn comes and ruins all his fun.

But what has me by the throat is the ineffable smell of the Land Rovers. Oil, diesel, sweat, engine, heat.

And I am brought back to a time just after my parents had divorced. I was 12 years old and every Thursday night, so my mother could have some “alone time” with her new boyfriend, my sister and I made a pilgrimage over to my father’s house so we could have some “family time” with his new wife and her son. I remember those dinners mostly for the clean cloth napkins (if we bothered with cloth napkins at home, they tended to be so filthy they lay in near origami shapes beside the plate) and the effort put into each meal. Naturally, there were tensions; namely, my sister and I had this crazy notion that we wanted, needed, to be alone with our father and have some adventure just the three of us. My father’s youth, at least to us, seemed so full of romance — an RAF pilot, a reporter on Fleet Street, a man who dabbled in car racing — that we assumed that his desire for adventure must still be festering just beneath his day-to-day life as a thrice-married man carrying the burden of alimony, children from two different women, an adopted son and a new marriage.

For me, it was a trip to the Arctic. I knew nothing about the place other than that it was north of my hometown of Montreal, it had polar bears and no trees. But I would spend hours as a little kid imagining him and me, parka-clad, setting out across the tundra. Not every girl’s dream but one I think was spawned by the fact that my father didn’t know what to do with children. The refrain that rang through my youth was “Children should be seen but not heard.” But he didn’t want children, heard or unheard. What he wanted was smart mini-adults. No running noses, no temper tantrums, no whining.

In pursuit of this, for my 7th birthday, he gave me T.E. Lawrence’s “Seven Pillars of Wisdom.” On my 8th, a hunting knife. Both utterly baffling gifts. Where the hell was the Suzy Homemaker Oven that I asked for?

I remember lying in bed that night, tentatively opening the huge tome and reading. For years we lived some how with one another in the naked desert, under the indifferent heaven. By day the hot sun fermented us; and we were dizzied by the beating wind. At night we were stained by dew, and shamed into pettiness by the innumerable silences of the stars.

I was a 7-year-old girl in a city clad in snow, and while each word made sense, I couldn’t even begin to fathom what on earth Lawrence was talking about. Silences of the stars? Within a day or two I put it away on my shelf to join all the other incomprehensible books I had received over the years, most of them, I might add, sent by his family in England. There “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” sat, leaned up against Somerset Maugham’s “Of Human Bondage,” which I had received the Christmas before, and the complete set of P.G Wodehouse’s Jeeves series that I got for my 6th birthday. It suddenly occurs to me that my father’s family were collectively out of their minds.

Neither my sister Sophie nor I ever got to have a real alone adventure with my father, at least not one where we went off into the wild. What we did have was the drive home after dinner. In those days he had an old Land Rover, a beast of a truck, with torn, hard seats and no heating. I’ve been told that the engine is supposed to supply one with warmth, but I think on those 10 below nights his Landy hogged all the heat for its own selfish purposes. My father loved that truck and, to demonstrate its pedigree, he liked nothing more than to run the thing full bore up snow banks after slaloming down the steep snowy hills of our neighborhood. I can still hear the low growl of the engine as it (plenty warm now) worked in tandem with my father’s deft gear shifting to extricate us from some high icy mount in order to deliver his half-frozen daughters safely home.

My father died in 2014, a year before my husband and I moved to Abu Dhabi, but here I am stepping into his truck. And already I am getting into a rage. Our little caravan pulls out, slowly. I look at the driver. We are going to pick up speed, right? We are going to take our lives in our hands and go flying over the dunes that are rising so majestically in front of us? Apparently not. Even my pressing an imaginary gas pedal to the floor doesn’t speed things up.

“This is my adventure,” I want to cry out. “This is what my father and I never got to do. You can’t be serious with this putt, putt, putting up the hill?”

With the world going past me at a crawl, I start to look around. To my left is a 20-foot-high chain-link fence topped with razor wire that seems to stretch for miles. Bedouin tribes traveled thither and yon for much of the millennia. With oil and modernity, their endless sands suddenly had value, and soon fences were put up. Still, it’s a little jarring. Chain-link fences are not part of my romantic notion of the desert. I try to block it out; after all, right in front of me are little desert deer. Cute but they did appear suspiciously on cue. I think of my father telling me that now that I had my hunting knife I could, if need be, slit an animal open from stem to stern and weather a storm sheltering in its warm entrails. He was full of practical advice like that. Naturally, now in the desert I try to imagine how I would survive if the five Land Rovers following me at a bovine pace, the skyline of Dubai, not to mention the authentic Bedouin camp all set up and ready not only to feed us but entertain us with sword fights and dancing girls, were all to disappear. What would I do?

Call a cab.

Let’s face it: My moment as an intrepid survivor, sucking out snake venom, building lean-tos, supping on grubs, fending off nocturnal attackers (though as a woman, I am schooled somewhat in that art) is as distant and improbable as the little girl heading out across the tundra with her dad.

But I’m here and I have a hidden flask so I might as well get into the swing of things. There’s a camel to ride and giggling women who are willing to henna my hands.

As the evening sets in and we gather to look at the night sky, I still hold out hope that if I just scratch at this sand, I will find the adventure, the romance. Then I look up and there, high above me, “the innumerable silences of the stars.”

August 5, 2017

Everyone deserves care: Insisting on compassion in the face of congressional cruelty

(Credit: Getty)

When I heard that the Republican effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act didn’t have enough votes, I thought that maybe my family could stop worrying about health care. The next day, my brother-in-law Bill, who relied completely on government assistance, died at age 75.

Developmentally disabled at birth and unable to work, my brother-in-law relied completely on Social Security, Medicare and California Medicaid for his support services that would be at risk with 35 percent cuts proposed to Medicaid. In addition to his physical disabilities, he faced many challenges from conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, Parkinson’s disease and behavioral issues. After 25 years in a state developmental center, during the last 10 years of his life, he benefited from high quality care through a state-supported assisted living service in California that enabled him to receive care in his own apartment. He received assistance with showering and dressing, meal preparation, feeding and transportation; all of this was provided by a small team of people who liked Bill and appreciated his humanity.

Bill loved jokes; he liked to tease and be teased. He had a big heart and cared about his family and care providers. He liked watching old westerns, especially Hop-along Cassidy and the Lone Ranger, or listening to Patsy Cline, Connie Francis and other music that reminded him of his adolescence. He had a penchant for chocolate milkshakes, fruit smoothies and stuffed animals.

One of my fondest memories is when Bill saved up his spending money to buy a small stuffed bunny for our youngest granddaughter, then three years old. He beamed when he gave it to her. She squealed with joy and hugged it close.

Some days Bill spent hours saying, “I’m sorry” over and over again. He may have been remembering mistakes made and things he had done wrong, but mostly I believe he was just apologizing for being different from other people in our family.

He also worried about who would take care of him. My father-in-law died 25 years ago, a few years after I met Bill. At that time, my husband assumed responsibility for Bill’s care and took it seriously — he visited him monthly, wrote to him every day they were not together, and coordinated larger family visits that included Bill’s nieces, nephew and grandniece.

Yet, Bill worried about who would take care of him if something happened to his older brother. So, when I visited, we assured him that I was the back-up plan. He still worried.

Although the latest attempt to repeal parts of the Affordable Care Act failed, I remain most concerned about the fundamental divisions about what kind of society we want. Please, no more talk about who is deserving of care or how much care they deserve. No more arguing about why people should care about people outside of their immediate family. I want a society where housing, food, clothing and health care are basic rights available to everyone. Not everyone has family around to watch out for them and safeguard their care. I want my tax dollars to provide for the most vulnerable members of society — the young, the old, people with disabilities, people who are sick — precisely because I think that the best measure of a society is its compassion.

This piece is part of Fighting for Our Lives: The Movement for Medicare for All, a Truthout original series.

Copyright, Truthout. Reprinted without permission.

A Turkish coffee reader predicted my pregnancy (and Andy Cohen’s skin cancer)

(Credit: pflorendo via iStock)

Is my boyfriend doomed to die in a motorcycle crash? Am I destined to develop early onset dementia? Is someone in my family secretly suffering from an undiagnosed terminal illness? If so, do I even want to know?

These are the questions rattling my brain on Saturday, November 26th as I travel from Manhattan to Queens to meet Sema Bal, the Turkish coffee reader known for accurately predicting future events in the lives of three cast members of The Real Housewives of New York.

The art of reading coffee cups has been practiced for centuries across the Middle East and many Balkan countries. Rooted in a combination of intuition and the translation of symbols, the process is relatively straightforward. Basically, you schedule an appointment with your local gifted coffee guru (an hour-long session with Sema costs $200), drink the highly caffeinated, muddy coffee she prepares for you, place your saucer atop your cup, swirl the little dish about, and then anxiously await the interpretation of any symbols that appear in the moist grounds left behind.

Although Sema sometimes sees specific dates and names or receives a message from a participating loved one’s spirit, she encourages clients to arrive with limited expectations and an open mind and heart. She also urges customers to relax for one to two hours prior to an appointment, but, try as I might, I can’t seem to shake dark thoughts from crowding my mind as I near her home. Can she sense my distress, I wonder.

For most of my life I’ve been a spiritual skeptic. Growing up, I never turned to horoscopes for a giggle, let alone answers. As a super confused 20-something, I never shelled out 20 bucks for a psychic reading. Nor have I ever purchased special crystals or burned bundles of sage to soothe my aching soul or whatever.

When my older sister died on April 5, 2009, however, something shifted within me. Since then, you could say I’ve become more open-minded. More hopeful that there is in fact a shred of meaning to be gleaned from the stars or a magic crystal ball or the residue stuck to the walls of a tiny porcelain coffee cup. Because, well, why the fuck wouldn’t there be?!

To her credit, Sema doesn’t ask any questions prior to meeting her clients. The process works better, she says, with little to no background information. So when I knock on her door that sunny fall day, all she knows is what I disclosed in my initial email: That I’m interested in channeling my dead sister somehow during our session.

As Sema ushers me from doorstep to dining room table, I feel immediately welcome inside the Turkish stranger’s cozy home. For whatever reason, her short, unruly bob, lack of makeup and thick accent put me at ease. So does her demeanor, which is that of a confident but not over-confident mystic. Someone who’s accustomed to seeing and maybe even understanding more than the average person. Someone who has prescient dreams about the likes of Andy Cohen.

In her book, “The Secret of Coffee Grinds,” Sema describes a vivid dream she had on December 4, 2014, in which she appears on Cohen’s Watch What Happens Live to read the talk show host’s cup and predicts that someone in his family has a serious health problem. This was a week before the Bravo network called her out of the blue to appear on The Real Housewives of New York, which, at the time, seemed like a coincidence in and of itself. Roughly two years later, on November 25, 2016 (the day before my visit), Cohen announced on national television that he’d been diagnosed with skin cancer.

In Sema’s world, such prophecies are as commonplace as pausing to channel the dead. But she’s not without a sense of humor about her special skillset.

As we sip our coffee, Sema uses Tarot cards to invoke my older sister Céline’s spirit. Then, quite suddenly, she’s cracking up.

“She wants me to write down 99,” Sema says. “I don’t know why — I don’t know what it means — but she’s insisting I do it. Then she wants me to circle the number.” With a shrug of amusement and no further explanation, Sema grabs a sheet of loose leaf to honor my sister’s weird request.

Sema then reassures me that Céline is with me in nature, which make sense. I’ve always felt my sister’s presence most acutely whenever I see a bird, simply because I used to call her Bird.

“She says she’s sorry for whatever happened,” Sema continues. “She has no more earthly worries. Whatever happened, whatever she went through, she’s okay now.”

However vague these statements might sound, they mean something to me.

“Do you feel her?” Sema asks, gathering her cards back into a pile.

I’m tearing a bit, because I do. It doesn’t seem to matter how or why. I just do.

Before we move on, Sema recommends collecting some dirt from my sister’s grave and carrying it with me at all times. A strange suggestion, perhaps, but one I plan to oblige.

Once we’ve finished our coffee, Sema gently reminds me that what she reads in my cup could be about me, or someone else. “It depends on your energy and who you’ve been thinking about,” she cautions.

Dutifully, I place my saucer on top of my cup, flip the whole thing over, and swirl it about. Then I wait, eagerly, as Sema investigates the mess within.

“When did you see a light in the dark? Someone guiding you? Could be in your dream . . . I don’t know . . . you see the torch?”

Sure enough, there’s a tiny torch-shaped smudge inside my cup, but I have no idea what she’s talking about.

For the next 20 minutes or so, Sema’s assessments flow in a stream-of-consciousness manner with very few pauses. There’s no stopping her as she expertly combs my cup in search of images—and, conceivably, hints about my past, present, and future. Noting that some of her statements might only make sense in the weeks to come, she encourages me to pay close attention to everything, so I do.

“You see the boots? Do you have a boot like that?

I nod because I do own boots resembling the tiny java silhouette of a pair she’s pointing to.

“There’s a big step coming,” she confirms. “Who’s Helen?”

“I have an aunt called Helen.”

“Keep an eye on her . . . Who’s flying to North Carolina? Anything Carolina? Next five weeks . . . ”

I rack my brain but can’t think of anything. Within seconds, Sema has moved on anyway.

“What does September mean to you? Do you have a project you’ve been putting on hold?”

“I’ve been putting off the whole baby-making thing, but I’m not really a procrastinator otherwise,” I say.

“That could be it,” she says. “You need to finish it by next September.” Before I can express that that’s a tight squeeze, Sema is onto the next symbol. “Who’s the brown-haired lady with hair up to here?” she asks, hand to her ear.

“My mom, I guess. But we’re not speaking currently.”

“Why aren’t you talking to her? She has high blood pressure. Get in touch with her sooner than later.”

As if I have no choice in the matter, I make a mental note to do just that.

“Does a tulip mean anything to you?”

“Not particularly.”

“Do you know a Pisces? Do they drain you? You see the fish to mouth? Be careful of the Pisces in your life . . . ”

“Okay,” I say, but I don’t know anyone’s zodiac sign other than my own.

“Who has a car that flipped over?”

“My boyfriend and his friend were in a really bad car accident years ago. The dude was actually at our house just this morning!”

“He’s overdoing it, your boyfriend’s friend. Tell him to take care of himself…Who’s Matt? Do you know about his eye problem? The headaches?”

“I don’t think I know a Matt…”

“You’re not going to Ireland, are you?”

“Not unless my Irish friend gets married.”

“There’s someone going to Ireland. Whomever’s going, tell them to enjoy it. Does a seahorse mean anything to you? Or a horse?”

“I used to ride horses a long time ago.”

“You don’t do it anymore? Why? Whatever opportunity comes after going to Ireland it’s going to be like riding a seahorse. Like wishes are happening.”

“Are you planting a tree soon by any chance? Or a seed?”

“Should I? Maybe a baby?”

“If you’re thinking about it, whatever seed you plant is going to grow . . . Do you have a cat? You see the little white cat? For me that’s someone who’s being too protective of you. If you need your space you need to tell them.”

Sema continues, spotting a penguin, a mountain, and a light-skinned man with dark facial hair who may or may not be my boss. It’s hard to keep up with her as she rambles, but I find myself hoarding each detail feverishly, trusting that I will make sense of it all eventually.

Sure enough, in the weeks following my session, a few key things begin to gel. I may not know anyone called Matt, but my coworker, Katie Mather, soon complains about an eye problem that sends her to the doctor. It turns out she’s prone to migraines, too. Meanwhile, that friend who was in a flipped-car accident with my boyfriend experiences a panic attack, so I tell him he really should mind his health. Another good friend suddenly connects with someone from North Carolina and, at my behest, pursues the opportunity that arises as a result.

All coincidences? Perhaps, but I can’t help feeling otherwise. Partly, it’s just more fun to believe. Plus, the fact is that my very first post-Sema revelation was a majorly convincing one.

Days after my visit with Bal, I was getting ready for work in my bathroom as usual when I saw it: The number 99, circled, just like the one my sister insisted Sema write down. The number stared back at me emphatically from the bottom right corner of an unopened box of pregnancy tests sitting on the top shelf of our medicine cabinet. The tests claimed to be 99 percent effective. Since we only started trying to get pregnant in November, I was dubious but hopeful as I tore open a stick to pee on immediately.

Moments later, I was running into the bedroom wielding my positive test, exclaiming that Sema and my sister had predicted my pregnancy! As it happens, my due date is August 11th, precisely one day past my dead sister’s birthday, and several weeks prior to that crucial September project deadline Sema mentioned during our session.

Though I haven’t yet figured out who the toxic Pisces in my life is, you better believe I’m on the lookout.

20 podcasts your kid should listen to this summer

(Credit: Getty/dolgachov)

What if something out there had your kid begging you to turn off the TV or tablet, put away the video games, and listen to a story? It seems practically impossible in today’s media environment. Why would anyone (especially kids who’ve grown up with YouTube and Netflix) bother with screenless entertainment? But with podcasts, “no screens” becomes “no problem.” Podcasts made for — and even by — kids are popping up all over the place.

What if something out there had your kid begging you to turn off the TV or tablet, put away the video games, and listen to a story? It seems practically impossible in today’s media environment. Why would anyone (especially kids who’ve grown up with YouTube and Netflix) bother with screenless entertainment? But with podcasts, “no screens” becomes “no problem.” Podcasts made for — and even by — kids are popping up all over the place.

Many adults are already familiar with podcasts, thanks to popular but mature hits such as Serial and Radiolab. But thankfully, podcasters are starting to realize that kids love what they’re doing as much as grown-ups. Teachers are even using them in the classroom. With exciting stories, fascinating facts, and lively sound effects to grab kids’ interest, all you need for an entertaining family-listening experience are some headphones or a set of speakers. Check out these 20 awesome podcasts for kids — including perfect bedtime stories, science exploration, cool news, and more. Plus, find out the best way to get them and use them. (We took our best guess for the target ages but include them as a guide since some of the content can be mature.)

How to Listen

It can be daunting for a first-timer to enter the world of podcasts, but digital tools have made it easier than ever to start listening. Podcasts are available to stream online or with a “podcatcher,” an app you can download specifically for podcasts. Here are some popular options for listening:

Podcasts . The original podcast app (only available for Apple iOS)

Stitcher Radio for Podcasts. “Stitch” together custom podcast playlists with this mobile app

Pocket Casts. A mobile app with a sleek, easy-to-use interface

SoundCloud . An online audio-streaming platform for podcasts as well as music (also an app)

Podbay.fm. Streaming platform specifically for podcasts (app available for Android, but iOS coming soon)

Kids Listen. An online (but not mobile) app that only features kid-friendly podcasts

Once you have your favorite app or website, search its library by topic and start exploring everything from science to sports to movies and more. And don’t forget to subscribe! Subscribing lets the app push new episodes directly to your device as soon as they’re available, so you’ll always have the latest update at your fingertips.

Pros and Cons of Podcasts for Kids

On the plus side, podcasts:

Boost learning. With engaging hosts and compelling stories, podcasts can be great tools to teach kids about science, history, ethics, and more. Listening to stories helps kids build vocabulary, improve reading skills, and even become more empathetic.

Reduce screen time. With podcasts, families can enjoy the same level of engagement, entertainment, and education as screen-based activities without worrying about staring at a screen.

Go anywhere. Podcasts are completely portable. You can listen in the car, on the bus, or in a classroom or even while doing chores around the house.

Cost nothing. Podcasts don’t have subscription or download fees, so anyone with internet access can listen and download for free. Most podcatcher apps are free, too.

Get two thumbs up from kids! Podcasts are designed to hook kids with music, jokes, compelling stories, and more. Some are designed in a serial format with cliffhangers at the end to get kids to tune back in.

On the downside, podcasts:

Play lots of ads. Many podcasts run several minutes of ads at the beginning or end. Because they’re often read by the podcast host, the ads can feel like a hard sell.

Can be confusing. Many podcasts update regularly, so you can jump right in and start listening. Others are styled like radio or TV shows, so the most recent episode is actually the end of a season. Check whether something is serialized or long-form before listening to the most recent update.

Vary in age-appropriateness. The iTunes Store labels podcasts “Explicit” or “Clean,” but even a “Clean” label doesn’t guarantee kid-friendly content. When in doubt, listen first before sharing with your kids.

Luckily we’ve discovered some excellent kid-friendly podcasts that you and your family will love listening to. Here are 20 of our favorites:

For the Whole Family

Dream Big

Precocious 7-year-old Eva Karpman and her mom interview celebs, award winners, and experts in a range of fields each week, with a hope of encouraging young people to find their passion and follow their dreams. The relatable mother-daughter dynamic and the big-name guests make this a fun choice for kids and their parents to listen to together. Best for: Kids

Wow in the World

One of the newest podcasts to hit the scene, NPR’s first show for kids is exactly the sort of engaging, well-produced content you would expect from the leaders in radio and audio series. Hosts Guy Roz and Mindy Thomas exude joy and curiosity while discussing the latest news in science and technology in a way that’s enjoyable for kids and informative for grown-ups. Best for: Kids

Book Club for Kids

This excellent biweekly podcast features middle schoolers talking about a popular middle-grade or YA book as well as sharing their favorite book recommendations. Public radio figure Kitty Felde runs the discussion, and each episode includes a passage of that week’s book read by a celebrity guest. Best for: Tweens and teens

This American Life

This popular NPR radio show is now also the most downloaded podcast in the country. It combines personal stories, journalism, and even stand-up comedy for an enthralling hour of content. Host Ira Glass does a masterful job of drawing in listeners and weaving together several “acts” or segments on a big, relatable theme. Teens can get easily hooked along with their parents, but keep in mind that many episodes have mature concepts and frequent swearing. Best for: Teens

Best Bedtime Podcasts

Peace Out

Produced by the same people who do Story Time, this is a gentle podcast that encourages relaxation as well as mindfulness. Great for bedtime, but also any time of day when kids could use a calming activity, this podcast combines breathing exercises with whimsical visualizations for a truly peaceful experience. Best for: Preschoolers and little kids

Story Time

These 10- to 15-minute stories are a perfect way to lull your little one to sleep. The podcast is updated every other week, and each episode contains a kid-friendly story, read by a soothing narrator. Short and sweet, it’s as comforting as listening to your favorite picture book read aloud. Best for: Preschoolers and little kids

What If World

With wacky episode titles such as “What if Legos were alive?” and “What if sharks had legs?,” this series takes ridiculous “what if” questions submitted by young listeners and turns them into a new story every two weeks. Host Eric O’Keefe uses silly voices and crazy characters to capture the imaginations of young listeners with a Mad Libs-like randomness. Best for: Kids

Stories Podcast

One of the first kids’ podcasts to grasp podcasts’ storytelling capabilities, this podcast is still going strong with kid-friendly renditions of classic stories, fairy tales, and original works. These longer stories with a vivid vocabulary are great for bigger kids past the age for picture books but who still love a good bedtime story. Best for: Big kids

Best Podcasts for Road Trips

The Alien Adventures of Finn Caspian

This serialized podcast tells the story of an 8-year-old boy living on an interplanetary space station who explores the galaxy and solves mysteries with his friends. With no violence or edgy content and with two seasons totaling over 13 hours of content, this sci-fi adventure is perfect for long car rides. Best for: Kids and tweens

Eleanor Amplified

Inspired by old-timey radio shows — complete with over-the-top sound effects — this exciting serial podcast follows a plucky journalist who goes on adventures looking for her big scoop. Tweens will love Eleanor’s wit and daring and might even pick up some great messages along the way. There’s even a “Road Trip Edition” episode with the entire first season in a single audio file. Best for: Tweens

The Unexplainable Disappearance of Mars Patel

This Peabody Award-winning scripted mystery series has been called a “Stranger Things” for tweens. With a voice cast of actual middle schoolers, a gripping, suspenseful plot, and interactive tie-ins, this story about an 11-year-old searching for his missing friends will keep tweens hooked to the speakers for hours — more than five, to be exact. Best for: Tweens

Welcome to Night Vale

Structured like a community radio show for the fictional desert town of Night Vale, the mysterious is ordinary and vice versa in this delightfully eerie series. Both the clever concept and the smooth voice of narrator Cecil Baldwin have helped the show develop a cult-like following. It’s a bit creepy and dark for kids, but older listeners will find it perfect for a nighttime drive along a deserted highway. Best for: Teens

Best Podcasts for Science Lovers

But Why: A Podcast for Curious Kids

Kids are always asking seemingly simple questions that have surprisingly complex answers, such as “Why is the sky blue?” and “Who invented words?” This cute biweekly radio show/podcast takes on answering them. Each episode features several kid-submitted questions, usually on a single theme, and with the help of experts, it gives clear, interesting answers. Best for: Kids

Brains On

Similar to But Why, this is another radio show/podcast that takes kid-submitted science questions and answers them with the help of experts. What makes this one different is it tends to skew a bit older, both in its questions and answers, and it has a different kid co-host each week. The result is a fun show that’s as silly as it is educational. Best for: Kids and tweens

Tumble

Often compared to a kid-friendly Radiolab, this podcast not only addresses fascinating topics but also tries to foster a love of science itself by interviewing scientists about their process and discoveries. The hosts don’t assume that listeners have a science background — but even kids who think they don’t like science may change their minds after listening to this podcast. Best for: Kids and tweens

Stuff You Should Know

From the people behind the award-winning website HowStuffWorks, this frequently updated podcast explains the ins and outs of everyday things from the major (“How Free Speech Works”) to the mundane (“How Itching Works”). Longer episodes and occasional adult topics such as alcohol, war, and politics make this a better choice for older listeners, but hosts Josh and Chuck keep things engaging and manage to make even complex topics relatable. And with nearly 1,000 episodes in its archive, you might never run out of new things to learn. Best for: Teens

Best Podcasts for Music Fans

Ear Snacks

The catchy soundtrack is the star in this delightful podcast from children’s music duo Andrew & Polly (not surprising since the hosts have created songs for “Wallykazam!” and “Sesame Studios”). But this funny program also covers a range of topics by talking to actual kids as well as experts, providing thoughtful fun for young ones and their grown-ups. Best for: Preschoolers and little kids

The Past & the Curious

Reminiscent of the TV show “Drunk History” (minus the alcohol), this amusing podcast features people telling interesting, little-known stories from history with an emphasis on fun and humor. Although it’s not specifically a music podcast, each episode contains an often-silly song that’s sure to get stuck in your head. There’s even a quiz segment, so kids will learn something, too. Best for: Kids

Spare the Rock, Spoil the Child

Families can enjoy rock and roll without the downsides with this fun radio show/podcast. Each week there’s a new playlist combining kids’ music from artists such as They Might Be Giants, with kid-appropriate songs from artists that grown-ups will recognize, such as Elvis Costello, The Ramones, and John Legend. It’s a perfect compromise for parents tired of cheesy kids’ music. Best for: Kids

All Songs Considered

This weekly podcast from NPR covers the latest and greatest in new music with a particular focus on emerging artists and indie musicians. It covers a wide range of genres and even includes artist interviews and live performances. Some songs contain adult themes and explicit language, but teens will love discovering a new favorite that you’ve probably never heard of. Best for: Teens

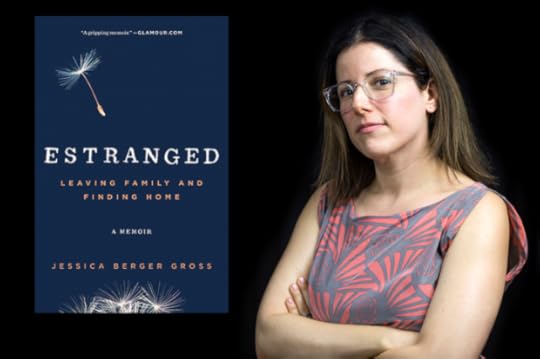

Breaking up with my parents

I wanted them to understand how the abuse had changed me. How I had nightmares. How I woke up sweating and screaming. How lost I’d been feeling. How alone and rudderless. How I wanted a family, but not this kind. There had to be a way to make them understand that there was no excuse for hurting a child, for having hurt me. I needed them to take responsibility.

But they hedged and defended and blamed and made excuses.

After a while the three of us started to lose our voices.

“I should have gotten a divorce,” my mother eventually admitted, sighing her saddest, most exhausted sigh. Finally.

Perhaps she still could leave? she suggested. Maybe she could come live with me?

I tried to imagine sharing an apartment in the city with her now. We could take care of each other like I’d hoped we would back when my father and brothers went to Boy Scout camp. Did I owe her that? Then I came to my senses. No. I was a grown woman and finally free. Besides, she wanted to be with him. We all knew there was no longer any point in her leaving him for my sake.

Fuck. My interviews. I called my college friend Natalie. Broken and shaky from the day, I asked if I could please stay with her. She and her husband were splitting up, and she’d very recently kicked him out, but she invited me to spend the week anyway.

* * *

I hadn’t planned on never speaking to my parents again, not when I stupidly agreed to let them drive me to Natalie’s apartment in Manhattan rather than take the train with my suitcase. Not when we got stuck in Sunday-night back-from-the-Hamptons traffic, me crying in the backseat, with R.E.M.’s “Don’t Go Back to Rockville” blasting on my headphones like a teenager. Not when I hugged them goodbye outside the car and told them that I loved them.

Not even right after that, when we realized my mother had accidentally locked the keys in the car and my father screamed for me to get him some goddamn wire hangers. And when, instead of staying to help them, I ran into Natalie’s building.

Natalie had a father in real estate, a job at a magazine, and a loft apartment in the Flatiron District with a gourmet kitchen and his-and-hers bathrooms. Her wedding had been featured in a bridal magazine.

“Lock the door,” I directed when she let me in. Her apartment was better than the one on “Friends.” She was giving me a tour when my father started buzzing her doorbell.

“Don’t answer that,” I pleaded. “Please!” Natalie backed away from the intercom, startled. She hadn’t realized my father was this crazy. Should we maybe call the police?

We moved to the far end of the apartment, where an enormous wall was lined with windows, and watched the action on the street below like it was a movie of someone else’s life.

My father had found some sort of a crowbar and shattered the driver’s-side window of his Subaru so that he wouldn’t have to prolong that horrible day for one minute more. The broken glass on the street looked oddly beautiful against the asphalt, like shards of diamond.

“Don’t call me” was what I’d said to my parents back when we were standing on the street saying goodbye. We had yelled and screamed and cried, and I had confronted him. But we’d done those things, to one degree or another, many times before. At least he hadn’t hit me. And my mother had taken my side. That was something. Progress, it felt like. I’d give myself a week. Maybe two. A breather. I wanted space, perspective. I needed to get through my job interviews.

That night I couldn’t stop crying. Would my father come back for me? I felt frail and frightened and unsafe. How would I make it in the world without them? I had no money, no job, and I had moved out of Martha’s to spend the summer with Neil. We were in love, but the relationship was very new, and we’d already broken up once.

Natalie filled the bathtub, lit an aromatherapy candle, and ordered takeout. She had a doorman, she reminded me. We’d be fine. Maybe she gave me something to help me sleep. Eventually I did.

I saw my mother the next morning. A coda on a street corner in Manhattan, a detail of the story I like to push away. Earlier that weekend my parents had taken me clothes shopping and bought me two interview outfits: a long skirt and matching top at Ann Taylor, and a black petite Tahari pantsuit that was on sale at a mall department store. The suit fit fine, but the Ann Taylor skirt needed hemming. It was at the tailor in Rockville Centre, which was closed on Sundays. My mother called early Monday morning and said she would bring me the skirt. No matter what had happened between us, she still worried about my looking nice for my interviews. She still loved me.

We met on lower Fifth Avenue. My mother hadn’t found a proper parking space and didn’t turn the engine off. The skirt, wrapped in dry cleaner’s plastic, hung on a hook in the backseat of her car. She was a hoarse mess; so was I. Anxious and angry, I less than halfheartedly thanked her for coming. Part of me was grateful. Part of me hated her.

“You’d better call your father,” she said.

I took the parcel and slammed the car door shut.

I never saw either of my parents again.

No, I don’t want your unsolicited parenting advice

(Credit: Getty/Fertnig)

“Have you tried cooking with her?”

“Have you tried cooking with her?”

This is the question I usually get whenever I describe my eight-year-old daughter’s selective eating.

For years I’ve responded to such unsolicited advice by describing all of the different tricks and tactics I’ve tried, including, yes, cooking with her. Halfway through yet another conversation last week about her food habits, I suddenly realized something.

I was being momsplained.

We are all now familiar with the term mansplaining, in which a man tells another person (usually a woman) how to improve a situation or solve a problem, regardless of whether he has any idea what he’s talking about, or even a decent grasp of the entire situation. Well-intentioned or not, it’s rarely helpful.

We moms do it to each other all the time, too.

Here’s how it usually goes down. You bemoan your latest parenting challenge—perhaps your child isn’t sleeping or refuses to practice piano, or maybe you’re at the end of your rope with the constant meltdowns or mouthing off. Inevitably, another mom jumps in with a story about How She Solved the Problem. She then dives into the details of the star chart, parenting guru, or Pinterest-worthy solution that had her kid on time for school, every single morning.

Momsplaining happens on the playgrounds and soccer fields, in Mommy and Me classes, and anywhere moms congregate and chat between sips of coffee. I’ve been momsplained so frequently in response to my online parenting rants—when I’m really looking for empathy — that I now either come to expect it or I explicitly note that I’m not asking for advice. I almost always receive a litany of suggestions anyway, most of which I’ve already tried or aren’t relevant.

As frustrating as it is to be the recipient of a momsplain, the truth is that I’m just as guilty of dishing it out as the next person, if not more so. I am a clinical social worker, after all, who works with parents, and I’ve written two parenting books. My desire to help is so strong that I have turned it into a career. That’s okay in my professional life, as folks come to me specifically asking for advice.

But my personal life is a different story, and I’ve had to dig deep to understand my desire to share the same unsolicited advice I have very little interest in hearing. When a friend is struggling with a situation I’ve already successfully managed, yes, of course I want to connect with her. And I also want to yell something like, “I can help! You don’t have to suffer through this the way I did!” Though I can probably count on one hand the number of times a piece of unsolicited advice has solved a parenting problem for me, that still hasn’t stopped me from telling everyone I know how I got my kids to take their antibiotics or play quietly in the afternoons even after they dropped their naps.

This common tendency among mothers is understandable; we’re parenting in a culture of constant counsel, often in the form of articles and listicles, expert opinions, and summaries of the latest research. Even so, we should all try to curb our urge to momsplain, for a few different reasons, some of which are not so different from the problems with mansplaining. Not only is it unpleasant to be on the receiving end of any kind of ‘splain, but it can leave a mom in need feeling even more isolated and incompetent, right at the very moment she is seeking support and connection.

Momsplaining also perpetuates two of the most insidious and damaging myths of our parenting generation: first, that every child-rearing challenge can be solved if we moms (and yes, this does seem to be a mom-centric dynamic) just work hard enough. There’s nothing wrong with hard work, of course, but the subtle implication here is that if our child is dealing with a persistent problem or developmental issue, it’s not because growing up is an inherently bumpy road, it’s because we moms haven’t done enough to smooth the way.

This brings us to the next myth of momsplaining: that someone out there is getting this parenting thing right, that someone out there has been able to integrate all of the research and advice and suggestions coming at her from every direction, and has thus unlocked the secret to managing the tantrums and power struggles and debilitating exhaustion in a consistently calm, graceful, and effective way.

Neither of these ideas is true. Not even close.

I’m not saying that we momsplainers are lying. But that particular hack or moment of parenting brilliance, the one that happened to work wonders, isn’t the whole story. I have no doubt that the smiling mom loitering after school was able to figure out how to get her child to sit still at the dinner table. But that doesn’t mean she’s not struggling with other issues, or even that whatever solution she found will keep working for her. Most importantly, it doesn’t mean it’s going to work for me or you.

The reality is that parenting is hard and messy for all of us, and unsolicited advice rarely makes it easier. Instead, for me, it reinforces the mistaken belief that I am the only one still bumbling around.

So the next time I’m moaning about my daughter’s wheat and cheese diet, let me vent for a minute. If you have a potentially helpful idea, ask me if I’m looking for advice before you share it. Otherwise, please don’t suggest a new food or cookbook or blog I should check out. Tell me about the time your kid only ate toaster waffles for three weeks, because what I really need to hear right then is that I’m not alone in this craziness.

Carla Naumburg, PhD, is a clinical social worker, the author of two books on parenting and mindfulness, and a (mostly) recovering momsplainer. You can find her online at www.carlanaumburg.com.

Thank your lucky stars you don’t have Eddie Coyle’s friends

Robert Mitchum in "The Friends of Eddie Coyle" (Credit: Paramount Pictures)

There are a lot of things I do a lot of, but heading up that list are two things I would imagine I do more than anyone: Every year I walk 3,000 miles inside of the city of Boston, and I also watch great gobs of Robert Mitchum films.

The actor is marking his centennial this Sunday, and it’s always confounded me that he never tends to get discussed with the likes of Jimmy Stewart, James Cagney (Orson Welles’ personal favorite) and Cary Grant as the best of Hollywood’s golden age.

When he is discussed it is in terms of his brawn, his tough guy persona, his status as a veritable noir god, or his wisecracking offscreen attitudes, which may or may not include reference to his pot bust in the late 1940s, when such matters were considered huge crises of social justice.

Equally baffling is how so many filmmakers manage to get Boston wrong. How so many actors get Boston accents wrong, with basically no films at all capturing the sounds and the prevailing senses of this city that I absorb as I crisscross it hither and yon week in, week out. And this includes actors from Boston. Come here, stay as long as you like, and you will never hear anyone talk like that cop Matt Damon plays in “The Departed.”

Mitchum rose to prominence in the film noir genre of the postwar years, his apex in that field of darkness being 1947’s “Out of the Past,” directed by Jacques Tourneur, with Jane Greer playing a far worse version of that ex of yours that you’ve told your buddies for years was the worst thing that ever happened to you.

Mitchum is virtuosic in the picture, but a lot of that has to do with his voice, which carries the bulk of the plot through flashback narration that at times reminds me of those old recordings of F. Scott Fitzgerald reading Keats, but these are odes of rain-slicked streets, dreams that have had their brains dashed out, the past getting pugnacious with the present and railroading the yet-to-be-born future.

Mitchum was crazily versatile, with turns in Charles Laughton’s beyond-creepy “Night of the Hunter” (1955), Howard Hawks’ late career “Western El Dorado” (1967) and William Wellman’s matchless war flick, “The Story of G.I. Joe” (1945). But for all of the noir glories — hell, 1952’s “The Lusty Men” is not only rodeo-noir, but it might be the best picture of Nicholas Ray’s career — there is nothing in the Mitchum canon like 1973’s “The Friends of Eddie Coyle.”

It is based on George V. Higgins’ book of the same name, which largely dispenses with traditional novelistic exposition. That is, there’s essentially no first- or third-person narrator setting scenes for us, as almost all of the book — or the parts that really matter, anyway — originate from dialogue. And good Lordy, is that dialogue a’cracklin’.

Higgins worked on the script for the film, too, which involves Mitchum playing the titular character. He’s a low-level, middle-aged Boston crook who simply wants to avoid doing another stint of time in New Hampshire. To achieve this end, he has to work for the cops to ply them with information on his fellows.

The “friends” of the title is deliberately ironic — this dude doesn’t really have friends, as he inhabits a world where connection matters less, and hunting people down matters more. It’s like fighting for survival in an online comments section where everyone tries to hide behind anonymity in a society that is increasingly fragmented and de-emotionalized, only we’re talking Boston city streets rather than computer screens.

The dialogue was so realistic that Mitchum was convinced that Higgins — a former U.S. lawyer — was using actual wiretap records he had. To get himself ready for the role, Mitchum got a cheap down-and-out middle-aged guy haircut, and started hanging out with some seriously shady guys on the Boston docks.

On my walks I like to visit some of the locations where “Eddie Coyle” was shot. There are the obvious ones — the Government Center plaza, Boston Common, the banks of the Charles, MIT. It’s uncanny to me the pace at which the film plays out, which seems to mirror much of what you naturally observe in the city. Boston is a pacey city, but it’s not NYC pacey, and while people rush about their business as you observe them outside, you also encounter a lot of conversations that play out with a kind of wistfulness amid the hubbub, even if they’re about if the Sox suck this year, or whether the Tall Ships are overhyped.

Director Peter Yates nails that feeling early on in the film, when Mitchum’s Eddie Coyle is at this depressing cafeteria-style restaurant for a meeting with Steven Keats’ Jackie Brown, a gun-runner Coyle is hooking up, so he can rat him out later. There is working both sides of the street, and then there is setting up food trucks on each side of them, and just kind of hoping both don’t cancel each other out. You know how it is when you’re desperate; there’s not a lot you won’t try, which makes all of us, in our way, noir denizens.

But this is a little different, because we’re in a post-noir world within “The Friends of Eddie Coyle,” and post-noir might be darker than standard noir, because there’s not an iota of Hollywood razzle-dazzle. Yates executes this scene largely in a two-shot, with Mitchum doing a lot of the talking, giving the upstart the lowdown on how he came by his nickname of Fingers. This is what an actual Boston accent sounds like. Mitchum was from Connecticut, so maybe some of it drifted down there, but his soft R’s have a quasi-English feel about them, like this is a speaker who is descended from people who once broke from a king, their souls perhaps more hardscrabble than nobly born, which set them up as noir folk early on.

The scene is in no hurry to advance, for it has much to convey to you, first, about these two men, and it pulls you from the back of your chair, just as the jaded Jackie Brown character is leaning in himself.

Mitchum appears in only about a quarter of the film, but it is the rare actor whose presence hovers over each scene in which he is not present. I think of it almost like the truly great athletes who always make their teammates better. Peter Boyle is excellent — and cast against type — as Dillon, a sort of Sam Malone-esque bartender figure who doubles as both your shoulder to cry on on as you wet your drink with tears, and the man who can, for a price, blow your head off. (Dillon’s bar was at the location of Tower Records at the Mass. Ave. end of Newbury Street, for you location trainspotters.)

I guess I probably shouldn’t say what happens to Eddie Coyle, if he skates over the ice or sinks under it, because this is a film that still has something of cult status about it, and I’m never surprised when people remark that they haven’t seen it yet. Just as I’m never surprised, having seen it so many dozens of times myself, how those who have watched it become impassioned fans. Eddie might not be loyal to his mates, but you tend to end up being loyal for all time to his picture, once you’ve seen how it all goes down.

But I will mention a scene near the end, where Dillon tries to take Coyle’s mind off of his troubles, by bringing him to a Bruins game at the old Boston Garden, that barn of a rink where the Balcony Gods bellowed out their lungs. Coyle is utterly transfixed by the play of Bobby Orr, who was basically Tom Brady in these parts before Tom Brady was born. Except, he was perhaps even bigger.

At one point, like a groundling at a Shakespeare play, circa 1599, Mitchum strains forward and shouts his encomia for this player, but he might as well have been shouting for the film itself, his own performance, his own career, this careful distillation of a city, and of a genre that had birthed a successor to itself in a single film that I’ll call the best of the 1970s. Sit the F down, “Godfather.”

Asked what had enabled him to be so successful in the role of the hunting and hunted Eddie Coyle, Mitchum cited a single confederate: that cheap middle-aged man’s haircut. But there ain’t nothing cheap about going as deep as this into a picture. And sometimes, never coming back out can be a good thing.