Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 333

August 12, 2017

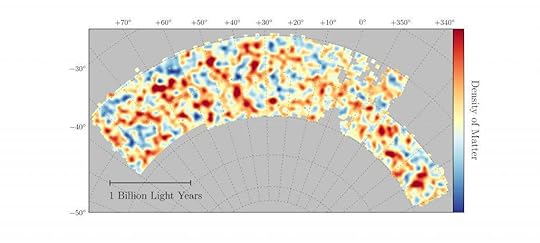

Find your place in the universe in this new dark matter map

(Credit: Getty/ClaudioVentrella)

If you aren’t sure what dark matter or dark energy are, don’t feel insecure about it — scientists aren’t entirely sure either. (There are some very convincing theories, though.) Combined, the two entities make up approximately 96 percent of the matter and energy in the universe — meaning “normal” matter, like what comprises you and everything you interact with, is the exception.

This week the Dark Energy Survey, a consortium of scientists across the globe, released a number of papers from the first year of their collaborative research effort, one of which produced “the most accurate measurement ever made of the present large-scale structure of the universe,” according to a press release. The map, pictured, shows a portion of the sky with the density of matter, both dark and ordinary, depicted on a color scale.

This covers a distance of 1,500 square degrees of the sky. In terms of our universe’s volume, that’s about 1/1200 of the visible universe, or 10 billion cubic parsecs. For context: one parsec is about 3.26 light-years across; our galaxy is about 100,000 light-years across; and the nearest star is around 4.4 light-years away, a little more than one parsec. Mapping the density of ordinary matter is one prospect, but mapping dark matter — which emits no direct light and seems to interact with ordinary matter in no way except via its gravity — is another prospect entirely. A plurality of cosmologists believe that dark matter is made of heavy particles that interact gravitationally with normal matter, and yet also interact with each other — and exert a sort of pressure on neighboring dark matter particles that prevent them from clumping together too much. Scientists can actually see dark matter “haloes” around galaxies, by observing how distant light bends around galaxies, or how galaxies seem to have more mass than their observable ordinary matter suggests.

Mapping the density of ordinary matter is one prospect, but mapping dark matter — which emits no direct light and seems to interact with ordinary matter in no way except via its gravity — is another prospect entirely. A plurality of cosmologists believe that dark matter is made of heavy particles that interact gravitationally with normal matter, and yet also interact with each other — and exert a sort of pressure on neighboring dark matter particles that prevent them from clumping together too much. Scientists can actually see dark matter “haloes” around galaxies, by observing how distant light bends around galaxies, or how galaxies seem to have more mass than their observable ordinary matter suggests.

Within the solar system, the effects of dark matter are not recognizable; because it permeates the galaxy at a relatively even pressure, we flow through it constantly without noticing it, much as fish move about oblivious to water. It is only on galactic scales that it becomes noticeable.

This is precisely how the Dark Energy Survey was able to measure and map dark matter. The Blanco Telescope in Chile, armed with a 570-megapixel camera, “one of the most powerful in existence,” was “able to capture digital images of light from galaxies eight billion light-years from Earth,” DES scientists wrote. By studying these galaxies’ motion and interaction, as well as how they bend light, scientists were able to infer how dark matter affected them. From that, they were able to create this detailed map.

The map is incomplete — in part because the sky survey is incomplete. The above map depicts about 1/30th of the sky. The Dark Energy Survey plans to continue mapping the rest of the sky over the next few years.

It is possible that some parts of the sky may never be mapped; the reason being that our galaxy’s stars partially occlude the view. Like many galaxies, the Milky Way is shaped like a thin wafer, with Earth about a quarter of the way from the center to the wafer’s edge. (The Milky Way’s center is comprised of a very massive black hole, the common point around which the galaxy orbits.) From our edge-on view, the disk of stars in the Milky Way obscures detailed imaging of some parts of the sky. And also like most galaxies, ours is permeated with dark matter, whose presence can be inferred by how stars at our galaxy’s edge do not orbit at the same speed as the Newtonian mechanics of ordinary matter would suggest.

More mysterious than dark matter, however, is dark energy — a countervailing force to gravity, which, rather than pull things together, seems to be accelerating the expansion of our universe outward. How and why dark energy works its dark magic is still not well understood. Yet current science suggests that as the universe accelerates its expansion under dark energy’s curse, distant galaxies will disappear from view entirely as they accelerate away from us. Eventually, the night sky from Earth will be lit only by those galaxies that are gravitationally bound to ours, and the rest of the universe will become unknowable.

Advice from “Insecure” star Jay Ellis on how not to settle for less

“Mediocrity is not going to get you anywhere but unhappiness,” said Jay Ellis, who plays Lawrence on HBO’s hit comedy “Insecure.” “It’s OK to have self-doubt and it’s OK to struggle with it and stumble along the way as you figure it out, but I think if you keep your eye on the prize and the thing that you want to do and you’re constantly learning and being a student of that thing, you’ll make your way there.”

Issa Rae’s breakout series, which began its second season on July 23, revolves around a young woman also named Issa (played by Rae) and her experiences as an African-American woman navigating life today. Ellis plays Lawrence, Issa’s boyfriend who broke up with her when she confessed to cheating on him at the end of season 1.

Ellis appeared on a recent episode of “Salon Talks” to discuss “Insecure” and how he never gave up on his dream of acting and his quest for advocacy.

On not giving up on your dreams:

Nobody is ever going to believe in you like you believe in you. It’s easy for people to believe in you when you have a good moment going or you have a good thing going but it’s those moments when you don’t that you have to keep pushing yourself. Even when you’re doing the thing that you think you’re meant to do you’re still going to face challenges and you’re still going to hit the wall. And that’s a part of life and that’s part of growth. For you to get to the next step I think you have to go through those things.

On using his platform and voice to discuss issues and social justice:

I do think one of the things is to constantly just get people to think and open their eyes to different viewpoints.

For me, I’ve lost a family member to AIDS; I’ve had another family member who’s lived with HIV for 20 years and it’s ravaging our community. So to me, I could not do what I do and reach as many people as I’m able to reach and not talk about it and say, “Go get tested, protect yourself when you’re out here.” We have the highest infection rate in this country and we’re only 13 percent of the population.

We need to break the stigma about these things and talk about them.

Slavery is still happening. Whether we think it’s happening or whether it’s not happening, dudes are being locked up over some of the pettiest laws and crimes. There is legislation that is literally built around keeping people in these boxes and putting them in situations where the minute they step outside their house, they’re going to go back to jail because of a parking ticket, because of something so petty. We’ve created these systems, we’ve been put in these systems that keep reoccurring. So my thing is we have to constantly talk about them, challenge them, and get people to be aware of them so you can make your own informed decision and opinion and hopefully leave the world better than when we got it.

Watch our conversation for more on Ellis’ inspirational advice.

How “Bitches Brew” blew our minds: Remembering the first time I heard Miles Davis’ masterpiece

(Credit: Getty/Bloomsbury Publishing)

In an era awash in commodified violence and gore — death metal and dark industrial, serial killer studies, Headline News Network, embedded war reporters — the opening seconds of Miles Davis’s album, “Bitches Brew,” remain the single most ominous thing in the infinite man-years of experience and consumption that pop culture has produced.

LP 1, Side A, Track 1: “Pharaoh’s Dance.” The first sound is Jack DeJohnette, one of two drummers, coming out of the right channel, keeping a quiet, insistent beat with quarter-notes on the snare and eighth-notes on the hi-hat. A quick bass drum rhythm — still quiet — near the end of two bars announces Chick Corea’s entrance on the electric piano. Also in the right channel, Chick is one of three keyboard players on the track (still waiting to enter are Larry Young in the middle and Joe Zawinul in the left channel). He’s playing a short, repeated fragment that might turn into a longer melody if the music were given enough time to develop.

But that doesn’t happen. Bennie Maupin’s bass clarinet and the electric guitar of John McLaughlin quickly join in with their own insistent repetitions. Lenny White taps his hi-hat in the left channel. Zawinul picks up the theme, such as it is. Young fills in a chord.

There’s no climax, no building to something greater and more developed. Almost immediately, the music comes to a halt, collapsing. Dave Holland answers with a rising arpeggiated octave on the acoustic bass. If this were all louder, the music might be representing an argument. The watchword, though, is quiet — the voices are all at a murmur, yet they carry a weight of intensity, as if the thing they are trying to articulate is just past the edge of language. There’s no identifiable hint of a song, the music sounds ritualistic. The way it whispers, the way it seems to follow the rules of a trance, the way it does not reach, or even seek, finality, make it existential.

I was probably fifteen when I first heard the record, down in the basement at my friend R’s house, after high school. It might have been his record, or it might have been his parents’ (they had a decent jazz collection). We played together in the school band (he played trumpet and I flute, and later baritone and tenor saxophones), and we were getting into jazz. For us, that path started with the contemporary leaders of fusion: Corea and his Return to Forever band, Stanley Clarke and his tremendous “School Days” album (one early, memorable concert we saw was Clarke, with Tower of Power as the opening act, but our very first concert was Jack Bruce and Friends in 1980), “Chameleon” and “Thrust” from Herbie Hancock.

Working backwards, we had found our way to a little bebop, but mainly to the first great Miles Davis Quintet, with John Coltrane on tenor, Red Garland at the piano and the incomparable rhythm section of Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, bass and drums. We were astonished that “Birth of the Cool” came from the same man. Miles’s restlessness confused us. We listened to a lot of great musicians who lit a fire when they were young, then stoked those same embers successfully for decades. We heard Sonny Rollins take apart his own playing and put it back together again in a new way, but no one else did what Miles did, shed one style after another — and not just styles but revolutions! He had a seeming discontent with success, and when other musicians began to follow his lead, he had to do something different.

Somehow, we stepped sideways and forward, and found ourselves listening to “Bitches Brew,” and that knocked us into another dimension.

It’s no exaggeration to say those opening bars disoriented us. We had trouble comprehending them. R would pick up the needle after those several seconds, put it back at the beginning, and we would try to listen again. After a few more times, we would stop and sit and talk and think. What disturbed us was not just the ominous tone the music carries with it like a bulldozing, inexorable force, but that we didn’t understand what was happening, how the music was made, how people could play that way, how they could think that way. Excavating my memory and imagination retrospectively, the sensation was like what the first encounter with a living alien civilization might be like, recognizably sentient beings communicating in a language that can express the most advanced concepts via what appear to be atavistic materials. “Bitches Brew” challenged the neat certainties of our youthful outlook.

We were playing jazz halfway decently already, and we understood tunes and chord changes and fitting a solo into that context. We knew how to organize our shit. But “Bitches Brew,” we could not understand how it was organized; we could not understand how each note determined the next one. It wasn’t haphazard, it made sense, and the fact that two bassists, two drummers and three keyboardists could play simultaneously, making the same music and keeping every note clear, was proof. It was the sound of a brilliant, profoundly restless musician, tired of his past and dissatisfied with the direction of the music he heard around him, using more than a little violence to force open a new path.

We were fifteen, so what did we do? We turned our sunglasses upside down and talked about the record among our friends while we made sure that we did so in crowds, so that our peers could overhear how cool we were. And we listened, because the dark beauty of the music and the unlimited possibilities it promised were irresistible.

On being a part-time working mom

(Credit: FotoShoot via iStock)

I was a stay-at-home mom for eight years. For eight years, I had no employment outside of raising my own children. I made no money, I had no career obligations. I was a classic “opt-out,” a woman who traded in a potentially high-powered job for the hearty mix of wonder, boredom and mess that is being a full-time caregiver to small humans. I didn’t choose to stay home because I thought it was best for my kids, that daycare or working mothers are somehow lacking. I chose it because it felt right at the time and I am well aware it was a privilege to do so.

I was a stay-at-home mom for eight years. For eight years, I had no employment outside of raising my own children. I made no money, I had no career obligations. I was a classic “opt-out,” a woman who traded in a potentially high-powered job for the hearty mix of wonder, boredom and mess that is being a full-time caregiver to small humans. I didn’t choose to stay home because I thought it was best for my kids, that daycare or working mothers are somehow lacking. I chose it because it felt right at the time and I am well aware it was a privilege to do so.

A few years ago, I chose something different. I got a job, a part-time job as a writer, that has taken up increasing amounts of my day, that has colored increasing amounts of my identity. Now when people ask me what I “do,” the answer is more complicated. It is a Venn diagram rather than a simple circle. I am half of one thing and half of another, and because both halves happen mainly in my home, there is an intersection, a blurry middle ground in which I find myself crafting sentences and macaroni and cheese at the same time.

Half of one thing and half of another. That’s not entirely accurate, though, is it? You can be a part-time worker, but can you be a part–time mother? It makes me think of the Stevie Wonder song, “Part-Time Lover,” I hum it to myself, changing the words for effect. Because yes, compared to the past, when my children were all of the phases of the moon to me, sometimes I feel like a part-timer indeed.

This shift in my status — and in my conception of myself — is encapsulated in my two sets of children, divided by three and a half years. The kids who came first still remember the full-time mother me. The one who was always there in body and mind.

The year he started school, I walked into my oldest son’s classroom and saw pinned to the wall a story he had written, in large, halting letters. It was called “My Family.” Alongside the usual five-year-old insights into the intricacies of family life (“I am a big brother”) was this one: “My mom doesn’t have a job.” I remember reading that sentence and feeling something cold and mildly unpleasant flush through my veins, and being surprised by the chill of it, because I was happy as a stay-at-home parent.

My discomfort with my son’s observation was partly a standard reaction to the invisible and undervalued nature of the labor of parenting. But it was partly a realization, now that he had come of age as an overtly thinking being — old enough to put his thoughts into words, penned and permanent—that his perception of my job, my role in life, had acquired a new sheen of importance. I had been spoon feeding this boy feminist sentiment from the minute he could babble — mothers can do anything — but kids have an uncanny knack of generalizing from what they see, as opposed to what you tell them, even if you tell it to them repeatedly and adamantly.

Dads work, moms don’t. Men drink coffee in the morning, women drink tea. Or so my son believed, and couldn’t be convinced otherwise, because it happened to be true in our particular house.

When I started working, it felt tentative. If I had taken up a job in an office, a job that had clear edges, that generated a steady income, perhaps the transition from stay-at-home mom to part-time working mom would have been smoother. As it happened, however, my own skepticism about my burgeoning career as a writer, and the fact that I wasn’t leaving the house to pursue it, was mirrored back to me by my older children.

Where once their mother would sit at the kitchen table absorbed by the glowing screen of her laptop and it was “leisure,” now she would do the same thing and it constituted “labor.” The situation was admittedly confusing, for everyone, and there was a period when I needed to retrain my kids, to reconstruct their idea of me and my availability. My second son would hover around the computer in frustration, musing about how he hated my job, the word enunciated with undeniable disdain, like it was leaving a bitter taste in his mouth. My oldest son would ask me to please stop “playing” on my phone, as I pecked out a time-sensitive email amidst dinner prep or homework.

Their father, it should be noted, whose identity as a working parent has been etched in stone from the very beginning, was never subject to such recriminations.

For my twins, however, my third and fourth children, this part-time incarnation of me is all they have known, a mother who has responsibilities that don’t involve them, a mother distracted sometimes, that faraway look in her eyes. “Play one game with me,” my daughter says on a recent day off from school, when I am mired both in childcare and deadlines. “And then you can do your work.”

At four, this little girl perches at her desk, marking up discarded printer pages with colored pencils and aplomb. She is working, she tells me, like mommy. A much talked about study says she is more likely to be employed herself now, since I am, to earn more money as a result. My sons want to discuss my latest article with me, they know I write about them, they offer opinions and quotations. Apparently, with a working mother, they are more likely to spend greater amounts of time as adults on childcare and housework.

This heartens me, somehow, though I wasn’t disheartened before. I wasn’t concerned for my daughter’s career prospects, when I was technically unemployed. I didn’t worry for my sons’ future egalitarianism. Mommy Wars be damned, I’m sure my kids have benefitted from both versions of me. When I was a full-time mother, they had more of my attention, a lot more of it. As a part–time working mother, what they lose in hours logged, they gain in the fact that I am modeling self-fulfillment.

Mothers are not static entities. We evolve in this role, like in any other. As my children have grown, as they have climbed the first rungs on the ladder of independence, and as I have had more (and more) of them, I have grown too. My interests have changed, along with my needs. Put simply: it’s not enough anymore to fill my days only with theirs. I am half of one thing and half of another. Each half makes me happy, and yet the whole still takes its toll.

Being a part–time working mom is a purgatory of sorts. It is undefined margins. It is scattered focus. It is the constant effort to arrange your features in the right way, to be present for the task at hand, whether it is orchestrating the perfect transition between paragraphs or the perfect move in Monopoly. Anne Tyler once said, when her children were small, that she is a writer between the hours of 8:05am and 3:30pm. That she keeps a partition up between the two halves of her life, so one does not intrude upon the other, so neither reveals itself as “ludicrous.”

While I like the idea of Tyler’s wall, on many days I doubt its reality. Balance and barriers sound perfectly reasonable in theory. But more often than not I am toiling away in the blurry middle: a better writer for having mothered; a better mother for having written.

August 11, 2017

Reengineering elevators could transform 21st-century cities

A 160-foot spire is seen atop the Wilshire Grand Tower building after a crane hoisted it into place early Saturday, Sept. 3, 2016. (Credit: AP Photo/Reed Saxon)

In the 160 or so years since the first skyscrapers were built, technological innovations of many kinds have allowed us to build them to reach astonishing heights. Today there is a 1,000-meter (167-story) building under construction in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Even taller buildings are possible with today’s structural technology.

But people still don’t really live in skyscrapers the way futurists had envisioned, for one reason: Elevators go only up and down. In the “Harry Potter” movies, “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and others, we see cableless boxes that can travel not just vertically but horizontally and even diagonally. Today, that future might be closer than ever. A new system invented and being tested by German elevator producer ThyssenKrupp would get rid of cables altogether and build elevators more like magnetic levitation trains, which are common in Japan and China.

Our work at the nonprofit Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat studies how tall buildings can better interact with their urban environments. One aspect is a look at how buildings might work in a world of ropeless elevators. We imagine that people might live, say, on the 50th floor of a tall building and only rarely have to go all the way down to street level. Instead, they might go sideways to the next tower over, or to the bridge between them, for a swim, a trip to the doctor or the grocery store.

This research project, set to conclude in September 2018, will explore as many of the practical implications of ropeless elevator travel as possible. But we already know that thinking of elevators the way ThyssenKrupp suggests could revolutionize the construction and use of tall buildings. Builders could create structures that are both far taller and far wider than current skyscrapers — and people could move though them much more easily than we do in cities today.

It’s hard to get high

Very few buildings are taller than 500 meters because of the limitations of those everyday devices that make high-rise buildings practical in the first place — elevators. Traditional, steel-rope-hung elevators can travel only around 500 meters before the weight of the rope itself makes it inconvenient. That takes more and more energy and space — which all costs developers money.

Replacing steel ropes with carbon fiber ones can save energy and space. But even so, people who want to go to the uppermost floors from the lowest floors don’t want to wait for the elevator to stop at the dozens of floors in between. That means developers need to make room in their buildings for multiple shafts, for express and local elevators, and for “sky lobbies” where people can switch between them. All of that space devoted to vertical transportation reduces the amount of rentable space on each floor, which makes the economics of the building more difficult the higher it gets.

Traveling in three dimensions

A new elevator system uses electric linear induction motors — the same kind of contactless energy transfer that powers magnetic levitation trains — instead of cables to move elevator cars around. This also lets them move independently of each other in a shaft, which in turn means multiple cabins can be working in one shaft at the same time. That reduces the need for parallel shafts serving different floors and frees up more real estate for commercial use. And there’s no inherent limit to how far they can travel.

Even more exciting is that these cabins can travel horizontally, and potentially even diagonally: The motors pivot to follow the powered track, while the floor of the cabin remains level. That opens up a whole world of possibilities. Without the ropes, it is also feasible to reduce the number of shafts a building requires, by allowing more cars to travel in one single shaft. It also becomes feasible to build massive building complexes interconnected by motorized vehicles operating high above the ground.

The difference between an elevator and a car, or even a train, becomes less clear — as does the difference between a building, a bridge and an entire city. Instead of descending from your 50th-floor apartment to the street in an elevator, then taking a taxi or the subway to another building across town, and going back up to the 50th floor, you might instead have a door-to-door ride between buildings, at height, in a single vehicle.

Creating the cities of the future

Is the world actually ready for this? Probably not right away. In the short term, we can expect to see systems like carbon-fiber-roped and ropeless elevators used in some of the very tallest, most high-profile (and expensive) buildings. Many of these structures house spaces used for many different purposes — residences, restaurants, retail stores, offices, cinemas and even sports. The people who live in, work in or visit those buildings have a wide range of destinations — they might want to stop at a shop to pick up something before going to a friend’s apartment for dinner before heading to a movie. And so they need options for traveling within the building.

At the moment, these systems are far more expensive than the conventional alternatives. Building owners won’t use them until they can save — or earn — lots more money by building systems like this. But as we’ve seen with computers and many other forms of technology, the cost goes down rapidly as more people buy the systems, and as research advances improve them.

There are probably physical constraints and efficiency limits on how many elevator cars could share a particular complex of shafts and passageways. And structural engineers might need to analyze what supports and reinforcements are needed to move people and machinery throughout large buildings. But the tall building industry has no standard data or recommendations to guide designers today. That’s what we’re trying to develop.

The technology is arriving — and with them the certainty that the old ways of traveling through a building are about to change more substantially than ever before.

Antony Wood, Executive Director, Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat; Visiting Professor of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University Shanghai; Research Professor of Architecture, Illinois Institute of Technology and Dario Trabucco, Tenured Researcher in Building Technology, Università Iuav di Venezia

When I first realized my daughter has an eating disorder

On a sunny day in June we picked up my daughter’s prom dress from Lena, our favorite seamstress. After a frenzied online search it had arrived — the perfect yellow dress with its delicate spaghetti straps — and it had only needed simple alterations. As Lauren tried it on to make sure the length was right, Lena said, “It ees too big,” in her lilting Italian accent.

On a sunny day in June we picked up my daughter’s prom dress from Lena, our favorite seamstress. After a frenzied online search it had arrived — the perfect yellow dress with its delicate spaghetti straps — and it had only needed simple alterations. As Lauren tried it on to make sure the length was right, Lena said, “It ees too big,” in her lilting Italian accent.

“See? In the shoulders and in the width. The dress does not fit. What happened? I fix right.”

I glanced at Lauren. Her face had a peculiar smile, one of pride.

I tried to ignore the icy fear that was building from my stomach to my neck. As we got into the car to drive home, I said, “Why have you lost so much weight? I think we need to see the doctor.”

“You can’t make me go,” said Lauren. “There’s nothing wrong with me.”

It was a statement I would hear many more times.

She was 16 when she slid into anorexia. She cursed at me. She stopped smiling. She ignored her friends. She chewed Peppermint Stride gum. She counted almonds.

It’s not that I didn’t notice changes in her behavior in the three weeks before her junior prom and before she had her final fitting for the dress. No more chocolate after dinner, only tea. No interest in warm bread fresh out of the oven. No interest in skating, her passion; instead, a sudden daily interest in going to the gym. No laughter at her younger brother’s silly comments.

Pieces of a jigsaw puzzle without clear borders.

“Teenagers,” I thought to myself. “It’s a phase, she’ll grow out of it.”

But intuitively, I knew something was wrong. She was secretive, quiet. Her eyes held a curious look of defiance.

And her dress for prom looked two sizes too big.

Anorexia? Not my daughter. She was too smart to have an eating disorder, wasn’t she? But her sudden, calculated 13-pound weight loss in three weeks said otherwise.

Lauren was petite. On the ice, she had a natural grace that wasn’t from being thin. She disapproved of skeletal skaters and called them “sticks.” Eating disorders are prevalent in the skating world, and so it was a topic we had discussed. I never thought my daughter would become one of those waif-like, unsubstantial girls, floating on the ice, like a ghost.

But like everything else she did, she was determined to perfect it. The quest for a flawless double axel had been replaced by something much stronger: a challenging journey of self-starvation.

She played the game. She manipulated the system. She stayed one step ahead of the experts. Gain one pound to keep the doctors satisfied was her strategy, lose three to please herself.

For two years after the junior prom and the ill-fitting yellow dress, I took her to doctors in Buffalo and Rochester where teen-age girls with broken limbs sat in waiting rooms, and doctors discussed the importance of food scales. I listened to her complaints about doctors and changed therapists when the first one asked her to play with dolls in a sandbox. At home I didn’t comment when dinnertime turned into a war zone or when her younger brother kept darting glances at her plate.

I didn’t tell her I was afraid of her wrath or I was afraid she was going to die.

When my daughter was four she lined up her stuffed animals in her walk-in closet according to color.

I thought it was cute that she liked to have them in order.

When she was ten, she told me she practiced double-jumps in her dreams, often landing on the floor of her pink-carpeted bedroom.

I thought it showed her passion for skating.

When she was fifteen, she refused to get off the ice, even after practicing for two hours, even when the Zamboni threatened to run her over.

I thought it showed her persistence and determination.

Then, at sixteen, her focus shifted to a world where victory was measured by eating half of a banana.

I thought about the life cycles of mothers and daughters, how the attention had shifted from scraped knees and lost blankets to sterile doctors’ offices and sullen glances. I had always been able to sense when something was wrong with her—when she had a fight with a friend, got a bad grade, or had a crush on a boy. But I couldn’t have predicted this disease happening in the throes of her teenage angst. I didn’t know this girl with dead eyes who said “I hate you” as easily as she once said “I love you.”

I missed her infectious laugh, and her ability to tease her little brother without making him angry; I missed the sparkle in her eyes.

The truth is, I couldn’t fix her. And yet, how could I stop trying?

As high school graduation grew closer she began to slip away, pound by pound.

And then one night, after a graduation party, she came home, hysterical. Flinging her purse against the door, she cried, “They had hot dogs at the party. I went to the bathroom, and Elyse was talking about how I went there to throw up. But I don’t do that. I never do that!”

I felt like saying, “No, you don’t throw up. You prefer to starve yourself.”

But instead, I said nothing. I didn’t understand how for her, sickness equaled power. I wanted to shake the eating disorder out of her brain, rattle her to pieces, exorcise every demon. When she left for college she had made some progress, but still, I was worried.

After one semester at Miami University, where she maintained a 3.8 average and earned multiple gold medals in intercollegiate figure skating competitions, she came home. She was 88 pounds. It had been four months since I had seen her. I recoiled in shock. Pencil thin, her cheeks were hollow. Her dark, luminous eyes were dull and sunken. Her wrists looked flat, grotesque, almost broken. She did not look like my daughter.

It was my job to protect her. Impossible, I know, in a world filled with terror, where suicide bombers appear at Parisian cafes, and children are shot at their elementary schools. In such a world, of course I can’t protect her. But in our world, our cocoon of tree-lined streets and manicured front lawns, I might have done better.

I may never know why being a good mother wasn’t enough to keep my daughter safe.

Perhaps for her, like everyone, the future will always be a fill-in-the-blank question, and this uncertainly worries me. For I remember how she preferred essay questions with lengthy, open-ended explanations—a blank canvas on which to create words of meaning.

Sometimes, though, it is enough simply to fill in the blank.

One word. A beginning.

And maybe a new yellow dress.

Amy Rumizen is a freelance writer and former Dance Critic for The Buffalo News and the mother of three. She is currently working on a series of essays about mothers and daughters.

A long and winding road: Kicking heroin in an opioid “treatment desert”

Heidi Wyandt, 27, holds a handful of her medication bottles at the Altoona Center for Clinical Research in Altoona, Pa., on Wednesday, March 29, 2017, where she is helping test an experimental non-opioid pain medication for chronic back pain related to a work related injury she received in 2014. (Credit: AP Photo/Chris Post)

Heather Menzel squirmed in her seat, unable to sleep on the Greyhound bus as it rolled through the early morning darkness toward Bakersfield, in California’s Central Valley. She’d been trapped in transit for three miserable days, stewing in a horrific sickness only a heroin addict can understand. Again, and again, she stumbled down the aisle to the bathroom to vomit.

She hadn’t used since Chicago. She told herself that if she could just get through this self-prescribed detox, if she could get to her mother’s house in her hometown of Lake Isabella, Calif., all her problems would be solved.

“I’ve been through a lot of horrible, crazy stuff,” said Menzel, now 34. “I’ve been raped. I’ve been beaten up. I’ve been in prison. But trying to kick heroin on the Greyhound on the way home was the worst experience of my entire life.”

When Menzel finally arrived at the Bakersfield bus station at 6 a.m. that day in February 2014, her mother and stepfather were there waiting. The two women hadn’t seen each other in years, not since Menzel stole her mom’s jewelry and fled the area. They didn’t talk much as they drove east though the twisty canyon on State Route 178 toward Lake Isabella, a two-stoplight town with a population of 3,500, nestled in the golden Sierra Nevada foothills.

Menzel hoped that the worst of the withdrawal was over — that a new life without heroin awaited. What she didn’t know was that heroin was now cheap and plentiful in Lake Isabella, as in so many small towns in the U.S., and that her best hope for treatment was far away.

32 churches, no methadone clinic

Experts recommend medication-assisted treatment for drug users like Menzel, one of nearly 2 million Americans struggling with opioid addiction, whether to prescription pills or heroin. MAT, as the therapy is known, has been proven far more effective — and less dangerous and miserable — than cold-turkey quitting. Drugs like methadone and buprenorphine can help suppress opioid cravings and stave off the physical and psychological symptoms of withdrawal.

When carefully managed, MAT can cut the risk of overdose death by half, research shows. But not all medical providers are properly trained and approved to provide the treatments, which themselves are opioids (albeit less likely to be abused). Only state-licensed and federally approved clinics can provide methadone, and doctors need to apply for a federal Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

Lake Isabella sits in the Kern River Valley, home to 32 churches but not a single methadone clinic or doctor able or willing to prescribe buprenorphine. Like half the counties in California, the valley is an opioid “treatment desert.”

“In rural areas, historically, there has been a lot of stigma around addiction treatment,” said Kelly Pfeifer, a primary care doctor and opioid project director at the California Health Care Foundation. “Although the state is trying to remedy this, there are still wide treatment deserts across California.” (California Healthline is an editorially independent publication of the California Health Care Foundation.)

In July, the California Department of Health Care Services awarded 19 applicants part of a $90 million federal grant to improve MAT access. In addition, $6 million was dedicated to support treatment in tribal communities. The agency hopes to create a network of “oases” in the state’s vast treatment deserts, many of which are in far Northern California, as well as eastern Kern County, which encompasses Lake Isabella.

The grants aim to pay for clinical and educational support to rural physicians, many of whom have never been trained in addiction medicine. Local doctors will handle most buprenorphine prescriptions, and in some towns, a mini-methadone program may set up shop.

But eastern Kern didn’t make the cut. For now, expanding opioid treatment in this area, and eastward, will have to wait.

Without such help, many experts say people like Heather Menzel — whose story a reporter followed over the course of a year — barely stand a chance.

Hooked again

From the beginning, Menzel struggled to stay clean at her mother’s. She soon fell back in with her old drug-abusing friends. Within two months of arriving home, her grand plan for getting clean slid into her veins and disappeared with the push of a plunger. She was hooked on heroin again, smoking methamphetamine and, once her mom kicked her out, homeless.

She was risking death, and she knew it. On average, 91 people a day in the United States died of an opioid overdose in 2015, the latest figures available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and projections show the death rate will continue to rise. Overall, California’s opioid death rate is relatively low: 4.73 deaths per 100,000 people. Still, 1,966 Californians died of an opioid overdose in 2015. Kern County’s rate was nearly double the state’s in 2015, and some sparsely populated rural counties, mostly up north, have rates that are far higher.

Policymakers fear the death risk is growing as use of fentanyl moves west. A synthetic opioid estimated to be 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, fentanyl has caused numerous overdoses and deaths on the East Coast. Some policymakers fear the fentanyl monster is heading to California, a potentially vast market of addicts.

“We really feel an urgency in California to increase access to services so if and when fentanyl arrives, we are more prepared to deal with it,” said Marlies Perez, chief of the Substance Use Disorder Compliance Division at DHCS.

Immediate, convenient access to these treatments is key. “It is very important for someone in the middle of addiction to access treatment when they are ready,” said Pfeifer. “There are these moments when people have wake-up calls — when they are ready to seek care and get out of the chaos of trying to get drugs to feel normal again.”

‘What do I do?’

Menzel’s wake-up happened when she noticed that she was still sick after a morning heroin injection. After an angry call to her drug dealer to accuse him of ripping her off, Menzel soon realized it wasn’t fake heroin — she was pregnant.

She took the bus to the emergency room in Bakersfield. “I’m fully addicted to heroin,” she blurted out to the ER doctor. “What do I do?” The doctor told her, “If you want to save your baby, you need to get on methadone.”

Affording methadone wasn’t a problem for Menzel. Medi-Cal, the state’s version of the Medicaid program for the poor, covered the costs. What impeded her was the daily trip from Lake Isabella to Bakersfield — an hour-plus bus ride down the curving canyon road. A round-trip ticket cost $5, more than she could spare. And if she missed an early bus back, she had to stay most of the day in Bakersfield to catch the next one.

For safety’s sake, the clinic started her at a low dose, increasing the amount until it was just right for her. But that beginning dose didn’t stave off the withdrawals, so she continued to use heroin and meth. She started to miss too many days of treatment and was kicked out of the program.

Menzel’s mother got her back in, promising the clinic that she would drive her daughter there every day. That meant quitting her job at Meals on Wheels.

“The fact you have to travel an hour to two hours every day to receive treatment requires somebody to operate a vehicle, pay for gas, and for some of our patients that is impossible,” said Javier Moreno, who manages the narcotics treatment programs in the Central Valley for Aegis Treatment Centers, the state’s largest methadone provider.

His Bakersfield clinics serve about 20 people in the Lake Isabella area, but Moreno thinks many more residents could benefit from MAT.

‘I made it’

Menzel didn’t take the ideal path to getting clean. But she eventually began to feel the groove of methadone, and her cravings for heroin subsided. After a couple of months, she was able to get methadone “take-home” doses for the weekend. She started riding the bus again to give her mother, who has the autoimmune disease lupus, a break.

“I was big and pregnant,” said Menzel, who woke up Monday through Friday at 5:30 a.m. to catch the bus. “I had to ask the bus driver to pull over and pee a lot. But I made it.”

In May 2015, Menzel gave birth to a healthy girl and named her Bella. She said she hasn’t used heroin or any other drug, besides methadone, in more than two years. She’s on a maintenance methadone dose, just 39 milligrams compared with 140 mg she used to take and plans to cut back until she is off it completely. Now she drives herself to the clinic every other week and has enrolled in community college, hoping to become a certified drug and alcohol counselor.

“I don’t know if there will ever be a methadone clinic in the Kern River Valley,” Menzel said. But if one ever arrives, she said, she’d love to work there.

“I really want to work with other pregnant women who will be going through the same thing that I went through.”

A working-class strategy for defeating white supremacy

FILE - This March 20, 2013, file photo shows Culinary Union workers demonstrating along Las Vegas Boulevard, protesting against their contract negotiations with Deutsche Bank in Las Vegas. (Credit: AP Photo/Julie Jacobson, File)

Ever since the earth-shaking election of Donald Trump, there have been innumerable articles arguing that Democrats brought this upon themselves by losing white, working-class voters in the Midwest. These articles have been met with a torrent of essays urging Democrats to focus on becoming the party of diversity. And, coming back from the dead like a bloated zombie corpse is Mark Penn and Andrew Stein’s New York Times piece calling for a return to Clintonian centrism.

All of these discussions imply that progressives can either fight for voters from the working class or communities of color — but not both at once. This line of thinking demonstrates a profound lack of faith in democracy and the electorate’s ability to smell bullshit.

As a seasoned union organizer, I often ask myself whether the pundits offering the aforementioned opinions have ever actually spent time talking to working-class people. By this, I mean all working-class people. Contrary to the narrative put forth in the mainstream — and even some left—media, some of the most significant work confronting homophobia, sexism and racism has been done by working-class people of all ethnicities through collective struggle in the labor movement.

My first substantive labor movement work was as a union organizer with California’s SEIU Local 250 — a healthcare workers’ industrial union, theoretically representing all non-management personnel in hospitals and nursing homes. In practice, the union mostly represented those classifications except registered nurses, who were generally represented by the widely-respected California Nurses Association. Local 250’s membership was racially diverse, with strong representation from African-American, Latino, Filipino and white workers. Standards were generally good for a union workplace: free healthcare, pensions, time off and competitive wages.

My first instructions at Local 250 were pretty simple: Go recruit 10 percent of the membership at the hospital to serve on the negotiating team, and get them ready to lead the entire hospital out on strike in two months. These were strong directives delivered with about as much subtlety. At the time, the union was engaged in a massive, coordinated contract campaign to achieve minimum staffing standards. This meant that as many as 30 hospitals would be bargaining and perhaps striking in coordination.

As a union staffer, one of my myriad job duties was to have meetings with members and member leaders, guided by a small pamphlet titled, “What is a Union?” This pamphlet emphasized that a union is “an organization of workers who all work for the same employer and act collectively to keep the boss from doing things that the workers do not want and to get the boss to do things that the workers do want.”

My job was to explicitly talk about racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, homophobia and religious intolerance as specific barriers to a strong union. A good union member can’t complain about Mexicans ‘taking jobs’ while also asking Latino colleagues to make common cause with him.

My experience was that union members took this seriously. Not only have I watched white men tell other men that sexual harassment has no place in their union, but — even more significantly — I have witnessed people develop genuine curiosity about people from different cultures. Latino housekeepers started eating with Filipino nursing department staff and trying to get to know more about where other people come from.

One story stands out. In preparing for the strike, a number of the African-American kitchen workers kept telling me that the Filipino nursing assistants “were weak” and would not stand up to management. Fortunately, one wonderful African-American female shop steward, Phyllis, pulled them all aside and said that such ethnocentric discussion had no place in our union. When the strike finally happened, not a single Filipino scabbed. In fact, Filipinos were the most dedicated picketers, earning them accolades from everyone in the union.

Along similar lines, I can think of one very religious certified nursing assistant, Gracie, who had strong feelings about homosexuality. We had several openly LGBTQ members, including two men and two women who held prominent positions as officers in the union. I led a discussion about how homophobia has no place in the union, during which Gracie said that her pastor believes being gay is wrong. Because everyone had an interest in uniting to fight against management, the LGBTQ leaders very respectfully told her of their humanity, their hopes and dreams — and how they wanted most of the same things that she did. Over time and through the struggle of fighting alongside her colleagues, Gracie not only changed her perception of her coworkers, but also became an ally for LGBTQ people in her community.

As an organizer, I learned that people often only make the effort to challenge their prejudices when they are engaged in struggle with others. This is not to excuse the horrific racism and sexism that has been exacerbated by the right-wing populism of the Trump campaign. Instead, we need to reach working people with authentic left-wing populism, which will win against the phony rightwing variety every time.

To advance anti-racism on the macro scale, we need to collectively engage in popular struggle, rooted in a left platform that is relevant and intuitive for poor and working people. There should be an immediate creation of a hopeful, broad-based mission that is winnable, which will serve to expand the resistance movement and create an organized majority to kill pernicious nationalism, masquerading as populism.

By embracing popular, left positions with a viable plan to win them, we can build support for basic civil rights. Ultimately, this isn’t just about winning elections: It’s about creating a mass movement that acts collectively to win. Let’s build relationships, go organize and actually get regular people excited about politics again. That’s how we do the real work to change people’s hearts and minds on race, gender, sexual identity and ethnicity.

Why 1987 remains the most important moment in alternative rock

The Psychedelic Furs; Depeche Mode; Echo & the Bunnymen (Credit: Legacy/Sire)

The National has achieved many things in its career: music festival headlining slots, Grammy nominations and near-chart-topping albums. However, the brooding, Brooklyn-via-Cincinnati band hasn’t had a No. 1 single — until now.

Billboard reports “The System Only Dreams in Total Darkness,” a song from the National’s forthcoming “Sleep Well Beast” album, reached the top slot of the Adult Alternative Songs chart for the week of August 19, beating Arcade Fire’s “Everything Now” by a measly two spins.

In addition to the National and Arcade Fire, the rest of the Adult Alternative Songs chart top 10 includes a slew of seasoned artists: Portugal. The Man, Spoon, The War on Drugs, The Killers and Jack Johnson. Sonically, these acts don’t overlap much. However, on an aesthetic level, they all promulgate a musical approach predicated on constant metamorphosis.

The Killers’ “The Man” is an icy, funky strut; the War on Drugs’ “Holding On” is rife with sparkling Springsteenisms; Portugal. The Man’s “Feel it Still” is a taut, soulful shimmy. The biggest chameleons might be Spoon, whose latest effort is the ominous, funky “Can I Sit Next to You,” which feels like Duran Duran filtered through a paper shredder and pieced back together.

In a striking parallel, the composition of the Adult Alternative Songs chart — notably the abundance of veteran bands who are fearless about evolution — echoes the equally transformative alternative bands dotting 1987’s music landscape.

That’s not necessarily surprising: 1987 was an enormously influential year that shaped how fans and artists alike create, consume and appreciate so-called modern or progressive music.

To understand why 1987 is a cultural inflection, it’s best to consider it the year a burgeoning underground movement crystallized and mobilized. Certain facets of this movement were already in place, of course. Specialty national video shows such as MTV’s “120 Minutes” and “I.R.S. Records Presents The Cutting Edge” and USA’s “Night Flight,” as well as regional video shows (V66 in Boston and MV3 in Los Angeles) were already airing clips from new wave and so-called “college rock” bands. Modern rock-leaning radio stations — notably KROQ in Los Angeles and the Long Island powerhouse WLIR — were also giving these new groups a platform.

On a more mainstream level, John Hughes-associated movies such as 1984’s “Sixteen Candles” and 1986’s “Pretty in Pink” combined relatable depictions of teen angst with a cool-mixtape musical vibe. Hughes treated bands such as Thompson Twins, New Order, OMD and the Psychedelic Furs like futuristic pace-setters. The people responded in kind.

In 1986, OMD’s “If You Leave,” from Hughes’ “The Breakfast Club” peaked at No. 4 on the U.S. pop charts. No wonder critic Chris Molanphy, writing in Maura Magazine, points to “how pivotal Hughes was in helping to break what became known as alternative rock in America — he served as a bridge between what was known in the first half of the ’80s as postpunk or new wave and what would be called alt-rock or indie rock by the ’90s.”

Hughes’ imprint reverberated well beyond films. For example, the movie “Pretty in Pink” took its title from the Psychedelic Furs song of the same name. Appropriately, the U.K. band re-cut the tune, which originally appeared on 1981’s “Talk Talk Talk,” for the film’s 1986 soundtrack. This slicker new version landed just outside the top 40, at No. 41. However, the goodwill earned by this re-do buoyed the Furs through 1987: The desperate swoon “Heartbreak Beat,” the lead single from the band’s 1987 LP, “Midnight to Midnight,” became the Furs’ only U.S. top 40 hit, peaking at No. 26 in May.

“Midnight to Midnight” polarized fans: A collection of full-on synth-pop gloss, it bears little resemblance to the group’s early, moody post-punk. Yet bold evolutions were a 1987 trend; multiple established modern and indie bands staked a decidedly contemporary claim, sometimes in ways that completely overhauled (or at least added intriguing new dimensions to) their previous sounds.

(Let the record show that this phenomenon also has precedent: For example, Scritti Politti’s glittering synth-pop gush “Perfect Way,” which reached the top 15 in 1986, is a far cry from the band’s scabrous post-punk roots.)

Elsewhere in 1987, Echo & The Bunnymen buffed up their gloom on a self-titled album with sharper production, while Depeche Mode countered with “Music for the Masses,” an (appropriately) massive-sounding record with a dense, industrial-synth sound. The Replacements, meanwhile, teamed up with producer Jim Dickinson for “Pleased to Meet Me,” their most streamlined and focused rock record yet. R.E.M. forged a production partnership with Scott Litt that would stretch into the ’90s, releasing the loud-and-proud political statement “Document.”

In many cases, these evolutions didn’t necessarily lead to immediate commercial dividends. In fact, the Smiths — inarguably one of the biggest cult alternative acts in the U.S. — broke up in 1987, making their forward-sounding final album, “Strangeways Here We Come,” a posthumous swan song. However, in 1987, the upper reaches of the pop charts were noticeably more amenable to modern bands.

Consider this a culmination of a slow and steady trend — how the chart inroads made by OMD and the Psychedelic Furs paired with those made by Pet Shop Boys (“West End Girls” hit No. 1 in 1986) and INXS (who set the stage for its blockbuster 1987 record “Kick” with 1985’s top 5 smash “What You Need”).

“Just Like Heaven,” from 1987’s “Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me,” became The Cure‘s first U.S. mainstream top 40 chart hit, peaking at No. 40 in 1988. The shimmering 1987 synth-pop gem “True Faith” also became New Order’s first top 40 single, landing at No. 32. Other bands found even greater success: Midnight Oil’s “Diesel and Dust” spawned that band’s first mainstream hit, the top 20 entry “Beds Are Burning,” while R.E.M. landed its first top 10 single with “The One I Love” from “Document.” Los Lobos’ cover of “La Bamba” hit No. 1 (though having a major Hollywood movie behind them helped tremendously).

What’s interesting: Besides individual radio station charts and specialized trade magazines, these alternative acts didn’t yet have a dedicated Billboard chart. The publication only launched its Modern Rock Tracks chart on Sept. 10, 1988, “in response to industry demand for consistent information on alternative airplay,” as it noted in that week’s issue. In hindsight, it’s easy to see this chart as a reaction to 1987’s alternative groundswell. The influence of these groups was now impossible to ignore, and measuring their reach and impact — no doubt crucial for label bean counters, if nothing else — made sense.

In an interesting twist, 1987’s beginnings and endings were as formative as their transformations. That year’s dissolution of the Smiths and Hüsker Dü led to each band’s frontman — Morrissey and Bob Mould, respectively — launching fruitful and vibrant solo careers that endure today. Debut records from Jane’s Addiction (a self-titled effort) and Pixies (“Come On Pilgrim”), and second albums from Dinosaur Jr (“You’re Living All Over Me”) and Faith No More (“Introduce Yourself”) put forth an aggressive, hybridized rock sound that presaged ’90s grunge, metal and punk. Even Crowded House’s 1986 debut LP finally spawned two hits in 1987, “Don’t Dream It’s Over” and “Something So Strong.”

And, in terms of the touring circuit, plenty of popular 1987 acts continue to find success; U2 playing 1987’s “The Joshua Tree” to packed stadiums is the most obvious one. Depeche Mode is currently embarking on an amphitheater tour while Echo & the Bunnymen and Violent Femmes have toured sheds together all summer. In spring 2017, Psychedelic Furs tapped Robyn Hitchcock as an opener. In the fall, the band is teaming up with Bash & Pop, featuring the Replacements’ Tommy Stinson, for tour dates.

These tour dates in particular have led several writers to recently question whether “80s pop” or “classic alternative” could become the new classic rock. It’s an intriguing idea, although one the radio consultants at Jacobs Media doubt has traction.

“While these bands may do well at state fairs and other summer festivals boasting well-stocked lineups of bands, their ability to support a format is questionable,” Fred Jacobs wrote in a recent blog post. “Classic Rock — and its derivatives — as well as Oldies stations were predicated on the power of nostalgia — not just for a few thousand fans in a market, but for tens of thousands or more of die-hard supporters. We’re talking mass appeal vs. niche.”

Jacobs then went on to point out that Echo & The Bunnymen received only seven spins on a Classic Alternative station in a recent week. “It’s hard to create a groundswell of support for poorly exposed music that’s now 30+ years old,” Jacobs adds.

In a sense, current successful bands like Arcade Fire, Spoon and the National are better positioned than their 1987 analogs to avoid this trap. Multiple channels — radio, video, streaming, live shows — make it easier for bands to gain exposure and reach more people.

At the same time, 2017’s fractured musical culture means that there are plenty of people who either don’t listen (or don’t need to listen) to any of these bands. For proof, just look at the puzzled reactions to Arcade Fire nabbing the Album of the Year Grammy in 2011. One person’s mainstream band is another’s niche or unknown act. Perhaps the underlying concept that drove alternative music culture’s 1987 rise — the mainstream cracking the door open to outsiders — is still alive and well in 2017.

Feminism can be funny too: Julie Klausner and season 3 of “Difficult People” on Hulu

Julie Klausner (Credit: Hulu/Craig Blankenhorn)

I am a discerning television connoisseur, and yet when Julie Klausner first begins speaking, I find myself surprised that she’s decidedly unlike Julie Kessler, the pop-culture-obsessed, snarky BFF to Billy Eicnher’s grouchy gay doppelgänger on “Difficult People,” now in season 3 on Hulu. First of all, Klausner is extremely kind and aware. Secondly, her humor is a perfect combo of “Curb Your Enthusiasm” meets meta, feminist commentary on everything from Donald Trump to depression to dybbuks. It’s like living inside Larry David’s mind if Larry David was a woman who binged on chicken fingers and knew all about Countess Luann’s divorce, only more subversive, gay-positive and political.

Here’s the thing about ordinary feminism: It’s good for the world but it’s mostly not a laughing matter. Remember WOST in college? It might have been edifying but it wouldn’t have played well in the Catskills.

Back in the fifth century BC, someone decided schlubby white dudes were funny and women were either boring and pretty or shrill, emasculating harpies bent on killing a schlub’s buzz. Of course, there were anomalies: “Lysistrata.” “Mame.” Also the legendary actress Rosalind Russell confounded everyone. She began her career as a model but then legend has it she was a klutz and so they told her to try comedy.

Russell comes to mind when watching “Difficult People.” Her comic timing and celerity. The fear you might blink and miss some sparkling bon mot. This is not the feeling you get while watching a Judd Apatow movie, where the reigning question is why white guys haven’t been canceled yet.

Klausner, on the other hand, seeks to subvert male and female roles using the traditional form of the sitcom: The man drives the action and women reacts and gets annoyed yet mysteriously stays with the guy anyway. Perhaps because he has the health plan? While Klausner herself is an ardent feminist, her TV id is considerably less self-aware and more self-involved. “Difficult People” depicts a central female who is both funny and unabashed, and shamelessly narcissistic in a way that male characters typically get to be. In other words, Julie Kessler is not a nurturer by anyone’s standards. That role is reserved for Julie’s live-in boyfriend Arthur, played by James Urbaniak. He does all the cooking, reacting and worrying while Julie drives all the action and does all the blundering. She even drives their sex life. He exists for her. He loves her. He even cooks for her.

Episode 2 of season 3 satirizing a Woody Allen TV series and a group of women protesting everything Woody stands for: WAWA — Women Against Woody Allen — is genius and somehow obliquely icky and true. When Julie admits she’s been cast in Allen’s series and that it’s “fucking horrible,” one of the protesters, a nemesis of Julie’s from season 2, reminds her, “They’re all horrible since ‘Crimes and Misdemeanors’” while Julie is cowering in a dumpster. In the same episode, Billy Epstein (played by Billy Eichner) is faking a Mike Pence gay conversion with Julie’s mother (the always amazing Andrea Martin) pretending to be his therapist in order to grift $6,000. The juxtaposition seems to say, we are all on the hustle, but you can’t hustle the hustlers. Or better yet, you can, but nobody wins.

“I wanted a chance to be the difficult one,” Klausner tells me over the phone. “I wanted to be the one with the understanding spouse, nodding and rolling their eyes. It’s pretty recent that women have a chance to be unlikable on TV or selfish, and the funny ones are always obnoxious, like Selina Meyer on ‘Veep’ or Lisa Kudrow on ‘The Comeback.’ As a comedian, I wanted to be the funny one; I didn’t want to be the person people fall in love with.”

In an entertainment universe where women still labor to get publicity to focus on something other than what they did or didn’t eat to get that bikini body or whom they’re schtupping, Klausner is committed to her craft, and she continues to hone both her writing and her schtick in a way that satirizes this trend — the way the public especially owns the lady bits of its female stars — with a character who is obsessed with pop culture and stardom but cannot seem to achieve anything resembling a career. Her character’s “unlikability” hinges on the fact that she cares more for herself and her career, nonexistent though it may be, than she does for her domestic partnership, or anything domestic for that matter. A Passover Seder at her mother’s sends her on a psych-med odyssey that culminates with her re-upping her meds at a Quiznos. In episode 9, “Sweet Tea,” Julie, Billy and the gang mistakenly take ayahuasca with a group of trans women as their unwilling spirit guides. Julie goes on a trip in which she sings a perfect musical number about Etsy and lost hope. It’s a genius send-up about what it means to be a woman who has made the choice of herself over financial success, starting a family or even personal happiness. That in certain circles this is still considered feminist or even radical speaks volumes.

“There’s a therapeutic alchemy to talking about something inaccessible,” Klausner tells me. “In a way, I think men have the advantage to draw on things besides their own personal experience because they have created the world.”

The question is what happens when a morally questionable female character (who may or may not realize she’s morally questionable) confronts being a woman in the age of 45? How does the feminist writer reconcile these truths and continue to be funny? Julie Kessler may be gaming the system — she drags an inflated strike rat around to avoid waiting on lines at trendy restaurants — but Julie Klausner, along with Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, and to a certain extent Amy Schumer, are reifying what’s available for female comedians on TV. The episode of “Broad City” with Hillary Clinton comes to mind, especially Abbi and Ilana’s messianic reverence for her and then the brutal wake-up call of what happened next.

“The election happened while we were writing season 3,” Klausner says. “We had to strike a balance between distraction and catharsis to show people not generally seen on TV surviving and living — a Jewish woman and a gay man with a trans conspiracy theorist (Shakina Nayfack). At the same time, we’re not Samantha Bee or John Oliver. I’m so glad I didn’t have to write jokes about the election but I live in a world where women are in control and a gay man is the lead.” She laughs and then says, “Of course, I would give it all back if the situation had worked out the other way.” I pause for a moment to wonder which Julie is talking, though I’m pretty sure I already know.