Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 292

September 23, 2017

What are animals trying to tell us about climate change?

“Our new book ‘Where the Animals Go’ aims to connect more people to more individual animals,” Oliver Uberti, co-author of “Where the Animals Go: Tracking Wildlife with Technology in 50 Maps and Graphics” told Salon’s Mary Elizabeth Williams on “Salon Talks.”

The new book, co-authored by James Cheshire, uses stunning visuals and data-driven research, tracks the behavior of animals, and in turn, how these animals navigate the world. Inseparable from the stories of various animals of air, sea and land featured in the book is the way animals correlate with our lives and the life of the planet.

“Where the Animals Go” documents and advances the findings of biology professor and ornithologist Henry Streby, who in 2014 investigated golden-winged warblers that flew south. Uberti explains the story behind “a series of maps of five small neo-tropical songbirds, these golden-winged warblers that had arrived back in Tennessee in their nesting grounds in the spring,” he said. “Shortly after they arrived, according to the data, they got up and left and went down to the Gulf of Mexico.”

Uberti said Streby investigated why the birds left their nesting ground in Tennessee, a place they usually stay for the entirety of the summer. He said Streby “looked and compared it to weather data and their own experiences on the ground, and remembered huge tornadoes and storms had come through.”

“Now these aren’t birds that just got up and left a couple hours before the storm, say because they sensed a drop in barometric pressure,” Uberti added. “They left two days before the storm arrived. Birds can hear ultrasounds, so it’s evidence that they probably heard the tornadoes coming.”

Watch our full “Salon Talks” conversation on Facebook.

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

Scorched earth sampling: the chaotic DNA of Public Enemy’s “Nation of Millions”

(Credit: AP/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon)

In the spring of 2008, the strange story of a Georgia widow was tearing up the AP wire. In 1995, her 33-year-old husband, Terry, had committed suicide, ending his life with a single shotgun blast. His heart was salvaged and donated to a man at risk for congestive heart failure, 57-year-old Sonny Graham. Grateful for his new lease on life, Sonny tracked down the widow to thank her. When he met her, he felt like he had known her for years. Exactly like the previous owner of the heart beating in his chest, he fell in love with her. They got married. Eventually, he too killed himself with a self-inflicted gunshot to the head.

Scientists say they’ve documented more than 70 cases of organ transplant recipients who adopt the personality traits of their donors. Parapsychologist Gary Schwartz told the New York Post that living cells have memory cells that store information that can be passed along when the organ is transplanted. The examples read like “Twilight Zone” episodes. A 68-year-old woman suddenly craves the favorite foods of her 18-year-old heart donor, a 56-year-old professor gets strange flashes of light in his dreams and learns that his donor was a cop who was shot in the face by a drug dealer. Does a sample on a record work in the same way? Can the essence of a hip-hop record be found in the motives, emotions and energies of the artists it samples? Is it likely that something an artist intended 20 years ago will re-emerge anew?

Hip-hop is folk music. Melodies, motifs, stories, cadences, slang and pulses are all handed down among generations and micro-generations, evolving so rapidly that it’s easy to lose track of exactly where anything actually began. Check the technique and see if you can follow it:

In 1986 in New York, Kool Moe Dee told careless Casanovas to “Go See the Doctor.”

In 1989, Dr. Dre manipulated Moe Dee’s record, giving his self-assured baritone a case of the hiccups, making him stutter out “ the-the-Doc, the-the-the-Doc” on “Mind Blowin’,” a single by Dre’s protégée The D.O.C.

In 1993, to show respect to his West Coast paterfamilias, Snoop Dogg vocally emulated the Dre-tweaked stutter on his debut single, “Who Am I (What’s My Name),” rapping he’s “funky as the-the-the Doc.” As the centerpiece of a multiplatinum album, Snoop’s version of the line ended up being the most popular one of all.

Snoop was surely the influence when the line went back to New York in 1999, when Jay-Z started “Jigga My N—-” with a salute to his Roc-A-Fella record label: “Jay-Z, motherfucker, from the-the-the Roc.”

Influenced by Jay-Z’s unknockable hustle, Atlanta rapper Young Jeezy flipped Jigga’s rock-hard version in 2005 on “Bottom of the Map” with “I do it for the

trappers with the-the-the rocks.”

It’s similar to the way folk musicians update the storyline of a popular murder ballad or put their unique pluck on a familiar set of chords. Sampling, however is a uniquely post-modern twist, turning folk heritage into a living being, something that transfers more than just DNA. Through sampling, hip-hop producers can literally borrow the song that influenced them, replay it, reuse it, rethink it, repeat it, recontextualize it. Some samples leave all the emotional weight and cultural signifiers of an existing piece of music intact — a colloidal particle that floats inside a piece of music yet maintains its inherent properties. All the associations that a listener may have with an existing piece of music are handed down to the new creation — whether it’s as complicated as a nostalgic memory over a beloved hook or as elemental as a head-nod to a funky groove you don’t specifically recognize.

Take the piano riff in Joe Cocker’s 1973 hit “Woman to Woman,” used in 2Pac and Dr. Dre’s 1995 smash “California Love.” Upon hearing “California Love,” an older listener might associate the riff with how much they did or didn’t enjoy the Joe Cocker original. A younger listener might think of it as a hip-hop hand-me-down, associating it with the Ultramagnetic MCs or EPMD songs that sampled the riff in the late ’80s. An even younger listener might not recognize it at all but simply understand that, since it clashes against a high-polished Dr. Dre production, it’s something “old” or “borrowed” or “funky,” imbued with an odor that’s mysterious but still evocative.

“It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” is congested with 100 of these samples — maybe more — ranging from the familiar to the obscure to the completely unrecognizable. A guitar lick from British rock band Sweet adds to the delirious feel of “Cold Lampin with Flavor.” Is it enough to say that the track “Funk It Up” is a great circa-1976 groove chugger on par with Thin Lizzy’s “Johnny the Fox”? Or is it worth noting that, just like Public Enemy in 1987, Sweet in 1976 were trying to reposition their band as a heavier, meaner, steely-eyed alternative to their past work? Is it a coincidence that “Nation of Millions,” an album focused on liberation, samples Isaac Hayes’ legendary move away from record company dictates, itself a singular success that followed a retail flop? Are the JB’s and Funkadelic and Temptations records that Public Enemy use permeated with special triumph and tumult since they originally appeared shortly after lineup changes?

“We use samples like an artist would use paint,” Hank Shocklee once said (George, Nelson. “Post-Soul Nation” New York City: Penguin, 2004). Their style was not the surrealist clouds of the Beastie Boys or the De La Soul sample collisions that would follow in “Nation of Millions’” wake. The Bomb Squad style of painting was a violent pointillism, taking a single guitar stab or drum kick and dotting the landscape until a song emerged. The Bomb Squad mistreated their samples — when one sounded too “clean,” Hank would throw the record to the floor, stomp on it and try again. They would occasionally break the (still standing) unspoken producer’s rule of “always sample the original recording” and sample a sample, just for an extra bit of chaos.

Their techniques were unlike anything of the era. And thanks to the diligent work of copyright attorneys, their cavalier, frontiersman attitude toward samples will never be repeated — at least not with the support and budget of a record label. They sampled dozens of records because there was never anyone saying they couldn’t. When Chuck envisioned the courtroom drama in “Caught, Can I Get a Witness,” a track in which he’s called in front of a judge because he “stole a beat,” it was a dystopic fantasy, a piece of fiction. Within a year, his story became reality.

How Trump could undermine the U.S. solar boom

(Credit: (AP Photo/David Goldman))

Tumbling prices for solar energy have helped stoke demand among U.S. homeowners, businesses and utilities for electricity powered by the sun. But that could soon change.

President Donald Trump – whose proposed 2018 budget would slash support for alternative energy – may get a new opportunity to undermine the solar power market by imposing duties that could increase the cost of solar power high enough to choke off the industry’s growth.

As scholars of how public policies affect, and are affected by, energy, we have been studying how the solar industry is increasingly global. We also research what this means for who wins and loses from the renewable energy revolution in the U.S. and Europe.

We believe that imposing steep new duties on imported solar equipment would hurt the overall U.S. solar industry. That in turn could discourage choices that slow the pace of climate change.

Trade complaints

A bankrupt manufacturer has petitioned the Trump administration to slap new duties on imported crystalline silicon photovoltaic cells, the basic electricity-producing components of solar panels – along with imported panels, also known as modules.

This case follows earlier and narrower complaints filed by SolarWorld, a German solar manufacturer with a factory in Oregon, that Chinese companies were getting an unfair edge as a result of subsidies and dumping.

Due to those cases, the U.S. has imposed duties on solar panels and their components imported from China and Taiwan. The punitive Chinese tariffs averaged 29.5 percent last year, according to the Greentech Media research firm.

Suniva, a U.S. company that – oddly enough – is majority-owned by a Chinese company, lodged this complaint in April under a rarely activated 1974 Trade Act provision called Section 201. SolarWorld Americas joined in a month later.

The key difference in this new case is that it will potentially lead to tariffs on all imported solar cells and panels, rather than specific kinds from particular countries.

Suniva’s petition calls on the Trump administration to set a 40-cent-per-watt duty on cells and a minimum 78-cent-watt price for panels.

Prior to the complaint, global prices for solar panels had fallen to 34 cents a watt.

Enormous progress

This big increase in import duties could undermine the enormous progress the industry has made in cutting the cost of solar-generated electricity. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory finds that tumbling solar module prices contributed a lot to the 61 percent reduction in the cost of U.S. household solar power systems – typically located on rooftops – between 2010 and 2017.

The Solar Energy Industries Association, which represents the sector in the U.S., calculates a blended average price that takes residential, commercial and utility-scale systems into account. It finds prices fell more sharply, dropping by more than 73 percent during that period.

Likewise, the Energy Department’s SunShot Initiative declared in September that U.S. utility-scale solar systems were already generating electricity at the competitive rate of 6 cents per kilowatt-hour – three years ahead of the program’s ambitious target for 2020. Falling costs for solar panels played a big part in helping the industry hit this milestone ahead of time.

The International Trade Commission will report on September 22 whether it finds that imported cells and panels have caused “serious injury” to Suniva and SolarWorld.

If it does, the independent, bipartisan U.S. agency will hold a second hearing to explore ways to respond. Regardless of what remedies the commission recommends, the White House would get broad powers to increase the cost of imported solar cells and panels to at least theoretically protect Suniva.

Jeopardizing jobs

Imposing duties on imported solar equipment will not help the U.S. industry as a whole. Like most experts, we believe that the remedy sought in this case will make solar power more expensive for businesses and consumers, which will reduce its competitiveness against other sources of energy.

Imposing new import duties also ignores the fact that the U.S. solar industry employs an estimated 260,000 people in installation, manufacturing, sales and other related activities, according to the Solar Foundation, but only a small fraction of these workers are involved in cell production.

Protecting certain manufacturers would thus come at the costs of harming other parts of the industry. The Solar Energy Industries Association, which opposes Suniva’s petition, estimates that 88,000 jobs may be at risk. Steep duties could thus undermine the contribution solar power makes to the U.S. economy

Solar globalization

Along with ignoring the effects on jobs across the entire industry, the petition misses the bigger picture. Cell and panel manufacturing composes a small part of a much larger industry that takes advantage of the global manufacturing base.

The rise of China as a solar manufacturing hub is an integral part of what has helped drive costs down for installation companies and consumers around the world. Lowering the cost of solar power systems makes solar energy more competitive against more carbon-intensive sources of electricity, including coal-fired power plants.

The growth of solar energy is one factor helping many U.S. states reduce their energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.

Experts disagree about how much the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change matters, particularly as states like California continue to work hard on reducing their carbon footprints.

But there is no debate over whether imposing duties on imported solar cells and panels would hinder the growth of renewable energy in the U.S. – reversing climate progress.

Timeline and punishment

Section 201 cases differ from more standard trade complaints because they do not require a determination of unfair trade practices. They also open the door to broader trade restrictions to remedy the perceived problem in a given industry.

If the International Trade Commission finds that imports have injured domestic companies, it’s expected to give the White House its recommendations by November 13. Trump will probably respond within 60 days.

It took decades of research and investment to drive down the cost of solar power to the point where it is competitive with conventional sources of electricity. Should these latest trade woes increase the cost of going solar, it would be likely to kill domestic jobs and slow progress toward cutting greenhouse gas emissions across the nation.

It took decades of research and investment to drive down the cost of solar power to the point where it is competitive with conventional sources of electricity. Should these latest trade woes increase the cost of going solar, it would be likely to kill domestic jobs and slow progress toward cutting greenhouse gas emissions across the nation.

Llewelyn Hughes, Associate Professor of Public Policy, Australian National University and Jonas Meckling, Assistant Professor of Energy and Environmental Policy, University of California, Berkeley

“Battle of the Sexes” has never been so relevant

Emma Stone and Steve Carell in "Battle of the Sexes" (Credit: Twentieth Century Fox/Melinda Sue Gordon)

There are a few different ways you could tell the story of the 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match between Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King. In the movie “Battle of the Sexes” (out Sept. 22), Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris (“Little Miss Sunshine”) opt for the most conventional. Simon Beaufoy’s (“Slumdog Millionaire,” “127 Hours”) screenplay doesn’t wade into the conspiracy theories that Bobby Riggs threw the match. Nor does it fictionalize the event the way, say, Todd Haynes fictionalized Bob Dylan’s life in “I’m Not There.” Instead, “Battle of the Sexes” is a three-act PG-13 sports movie that climaxes in a monumental moment of odds-defying, sports-transcending triumph. It’s the same playbook used in “Rocky,” “Remember the Titans,” “Rudy,” “Miracle” and a million other sports movies. But man is it resonant now!

If you’re vaguely aware of the story behind the match (watching the trailer will do) and if you were sentient throughout the 2016 presidential election, you get it. Bobby Riggs is an old, white clown who promotes the match by labeling himself a “male chauvinist pig.” He faces off against Billie Jean King, a serious woman equally driven on the court and in the pursuit of equality. The parallels could hardly be more glaring if the story included Russian subterfuge.

But “Battle of the Sexes” is too smart — or honest — to cast Riggs (Steve Carell) as a nefarious villain. The movie opens by showing him bored by life post-professional tennis. A gambler and showman at heart, Riggs is incapable of settling into an office job and the doldrums of middle-aged married life. After Billie Jean King wins a tournament, he hears on the radio that King has become the most successful female tennis player ever, and he gets an idea. He’ll challenge the top women. At the time, Riggs was married into wealth, so he didn’t need the money. Nor does it seem he was motivated by a desire to flaunt male superiority. He was just looking for some attention and a good romp.

Billie Jean King (Emma Stone) understands Riggs’ angle. And she doesn’t want any part of it. But when Riggs beats Margaret Court, the other top women’s player, King finds herself boxed into a corner. The movie introduces King by showing her fighting for equal pay in a tournament. When the tournament promoters refuse, citing a variety of reasons that barely veil the underlying sexism (from “men draw more fans” to “men are more exciting to watch”), she starts her own tournament. The match against Riggs is part of the same battle. If she refuses the challenge, she’ll be perceived as a coward; if she loses, it will validate the sexism. But if she wins the match, she could chip away at systemic male supremacy.

There’s an illuminating scene that comes just prior to the match, in which Billie Jean King tells Jack Kramer (Bill Pullman) why she won’t play if he is the game’s commentator. Kramer is the same promoter who refused King’s demands for equal pay. And during the Riggs-Court match, he picked Riggs to win because of his belief that women aren’t built to handle the pressure. The difference between Riggs and Kramer, King tells Kramer, is that Riggs is a clown and Kramer doesn’t respect women. One is a provocateur, the other is a propagator of harmful prejudice.

Perhaps it’s obvious, but the great insight on the part of King — and the film — is that she and Riggs primarily exist as symbols. “I think everyone cares what I do,” King tells a female love interest after she has listed off all off the reasons they can’t be together. The film juxtaposes King agonizing over the world’s perception of her with Riggs blatantly disregarding what other people want from him. They’re held to different standards. She has to be perfect. He doesn’t have to be anything (again, sound familiar?).

I’m not sure whether “Battle of the Sexes” is supposed to be a reminder of how far America has come in the past 45 years or proof that the nation has made hardly any progress at all. Maybe both. Equal pay for equal work is practically universal consensus. And Jack Kramer comes across as a dinosaur. But then, how far removed is James D’Amore? And what of Trump stalking Hillary Clinton on the debate stage? And on and on.

Billie Jean King clearly didn’t shatter American sexism with a few sharp swings of her racket. But the movie is a testament to the importance of clearing barriers. Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris didn’t need to make a Haynesian fictionalization; their film inspires viewers to imagine an alternative history of both the past and the present. The stakes of a presidential election are much greater than those of any tennis match, but there’s a universe where King loses and it empowers misogyny in the same way as Trump’s victory. And conversely, there’s a universe where Hillary Clinton wins the presidency and the victory moves national policies and norms forward, faster.

The history of American biopics is littered what Tom Brown, in “The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture,” refers to as a “Great White Man-centric” view of history. The biopic has often been an engine of American myth-making, by and for white men. Without casting all white men as evil, “Battle of the Sexes” succeeds at myth-disassembling. Trump may be a chauvinist pig, but more pernicious than Trump is the system from which he benefitted. There are more artistically inspired versions of the “Battle of the Sexes” story, but in art, like in tennis, the moment dictates the shot; this moment called for a crisp forehand smash, and “Battle of the Sexes” delivered.

September 22, 2017

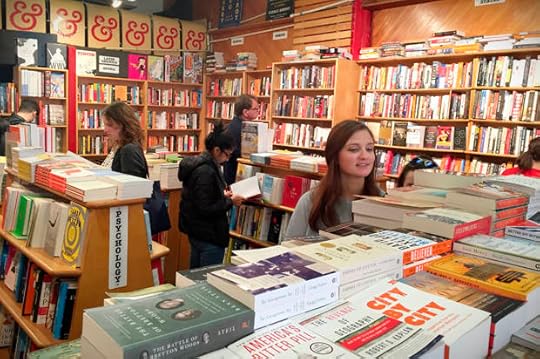

How to motivate a middle school reader

(Credit: AP/Beth J. Harpaz)

In the early grades, parents and teachers focus on teaching kids how to read. As kids get older, we hope they’ll want to read. Reading for pleasure has lots of benefits. It builds vocabulary and improves reading comprehension, writing, spelling, grammar, and knowledge of the world. It also boosts test scores.

In the early grades, parents and teachers focus on teaching kids how to read. As kids get older, we hope they’ll want to read. Reading for pleasure has lots of benefits. It builds vocabulary and improves reading comprehension, writing, spelling, grammar, and knowledge of the world. It also boosts test scores.

A 2013 study found that kids’ leisure reading is linked to increased cognitive development — in other words, clearer thinking, better problem-solving, and improved decision-making.

But as we reported in our 2014 research brief on Children, Teens, and Reading, reading for fun drops off dramatically as children move into the tween and teen years. So it’s crucial to find ways to encourage middle schoolers to read.

One key is to tap into what your kids like to do, what they’re interested in, and where they are in their emotional growth. At this age they’re social, curious, beginning to pull way from their parents to forge their own identity, and fine-tuning their sense of humor. Thus, books that expand their view of the world or poke fun at the world they know (family, friends, puberty, school social dynamics) hold a lot of appeal, as do imagined worlds of science fiction and fantasy.

Try these six tips to get middle schoolers reading:

Let them choose what they read

Having control over what they read increases kids’ motivation to do it. And don’t criticize their choices or formats — books, ebooks, graphic novels, articles. To widen the field, take them to the library or bookstore. Browsing in a used bookstore can be a revelation (and easier on your wallet!).

Feed their interests

Whatever your kids are into — basketball, space exploration, World War II, alien invasions, wizards and dragons, humor, teen romance, social justice, books about middle school (a vast genre unto itself!) — there are books about it. Finding a book on a topic your kid is already passionate about is half the battle.

Make it social

Reading the latest hit book lets your kid be a part of what “everyone” is talking about. Many friendships have been formed over a love of Harry Potter or the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy. Check the middle-grade bestseller lists, clue your kid into book blogs (including ones by kids and teens), and ask booksellers and librarians what kids this age are requesting. And keep your ears tuned to book raves on carpool rides!

Mix movies and books

Many books written for kids and teens are adapted into movies, and knowing there’s a big-screen version on the way can motivate kids to read the book first — or after — to compare the book and movie versions of, say, Wonder or “A Wrinkle in Time.” It also gives kids the chance to be the expert who knows more on a subject than their parents.

Follow the series

If your kid likes the first book in a series, keep ’em coming. Adventure sagas and dystopian nail-biters, which kids love at this age, have lots of installments, each ending on a tempting cliffhanger. Getting hooked on a series like Percy Jackson or The Mortal Instruments leads to being hooked on an author, which leads to more books and even spin-off series.

Make time for reading

Model reading at home by turning off the TV and devices and reading a book or magazine yourself in full view — your kids will be more inclined to follow your lead and read themselves. Try reading aloud: Big kids like it, too. And when you go out, get kids in the habit of bringing a book or magazine along in the car: They’re great boredom killers!

3 signs that gentrification is coming to your neighborhood

(Credit: Brian Berman/Lululemon via AP)

When she returned one evening from what I thought was a routine dog walk around the neighborhood, my partner was nearly in tears. Perplexed and concerned, I probed for an answer.

She explained the sinking feeling of watching her hometown of Oakland, California, become unrecognizable: The urban farm and playground that recently popped up on Peralta Street had not a person of color in sight. Tent encampments with dozens of newly shelterless black people sprawled out beneath freeway overpasses. White neighbors shot quizzical or fearful looks as she passed. Walking the dog — a practice that once brought her joy and rejuvenation — now left her feeling deflated, angry and seemingly powerless. Her home, her community, had vanished. It had all been building up over the past few years, and in those moments as she walked, it became too much to take.

A news search of “gentrification” will land you with thousands of perspectives both for and against. Though the debate has emerged most vocally in the past several years, for residents born and raised in major cities, the ongoing loss of home is felt deeply.

“It is a feeling of powerlessness,” says Bie Aweh, who was raised in the Roxbury and Brighton neighborhoods of Boston. “You’re already vulnerable because of poverty, and it makes you feel like you have no power because capitalism talks the loudest.”

While many in support of urban renewal and development cite decreased crime rates and increased revenue as benefits, long-term residents from coast to coast echo concerns about the impact of gentrification on historically poor, predominantly of color neighborhoods.

Each of the people I spoke to were raised in historically black, poor communities now experiencing continued or more recent waves of gentrification. Noni Galloway, of Oakland, defines gentrification as, “when an environment or culture is taken over or redefined by another culture.”

On a surface level, the changes that come with gentrification are physical — new beer gardens, condominiums and bike lanes — and happen seemingly overnight. Many residents are left to grapple with what, where and whom to call “home.”

1. Shifts in demographics: ‘White people jogging was the first sign.’

When I first moved to Berkeley as a teenager in the early oughts, my peers had endless warnings for me about the neighboring city of Oakland. People living outside of Oakland, many of them white and/or middle to upper class, generalized it as “sketch,” “dangerous” and “crime-infested.”

The neighborhoods they cautioned me against visiting are now, over 10 years later, spaces where young professionals are flocking to, often describing them as “up-and-coming.”

When asked to reflect on the first signs of gentrification they saw in their cities, three of four interviewees specifically mentioned “white people jogging,” especially in areas they previously would not have set foot in. The influx of white and middle-class newcomers on its own is not the issue; rather the loss of culture and diversity that comes when a city’s long-term inhabitants can no longer afford to stay.

“We used to be a Mecca for black home ownership. Now illegalforeclosures.org reports that thousands of illegal foreclosures take place in Wayne County,” said Will, an activist from Detroit. “The discussion of so-called ‘improvement’ should not be separated from the misery being created for tens of thousands of Detroiters.”

Much of the conversation in support of gentrification is coded in a racist and classist belief system that blames the residents themselves for crime rates, rather than lawmakers, local politicians and complicit newcomers who are disinvested from solving the causes of poverty.

The increase of white and/or middle-class new residents to traditionally poor neighborhoods tends to follow or reflect changes in infrastructure, another highly discussed symptom of gentrification.

2. Shifts in infrastructure: ‘Government housing began to disappear.’

“Government housing began to disappear and the projects were being torn down,” said Crystal Lay, of Chicago. “People were being displaced to other areas and put in these quickly built homes.”

The shifts that happen to city landscapes undergoing gentrification are more than physical, they are symbolic of efforts to “improve” an area for incoming residents.

For those who have called these cities home since childhood, there are some strange contradictions: new bike lanes and rent-a-bike programs on streets riddled with potholes; sleek, market-rate apartments popping up beside historic Victorians; urban gardens and beautification in prior dumping grounds.

Oakland’s Noni Galloway summarizes the complex feelings that arise from witnessing these shifts overtime: “I have mixed emotions because … there were much-needed upgrades to the area that I feel didn’t happen until the gentrification started,” she said. “But it hurts to see my old neighborhood turn into the hot spot for someone else to enjoy.”

Another undeniable impact of the skyrocketing housing market is the increase in individuals without shelter, some of them former residents who have been recently evicted. In Oakland, homelessness increased by over 25%, and complaints went up by 600% between 2011 and 2016.

When developers are allowed to build housing starting at $3,000 a month in a neighborhood with a median family income of $35,000, what is being improved? Where can a family call home after their house becomes unrecognizable and unaffordable? What is the cost of gentrification? And who pays?

“Whites and the rich benefit the most,” said Crystal Lay. “I believe poor people and people of color lose. I think any mom-and-pop businesses also lose their customer base and those familiar faces.”

3. Shifts in safety measures: ‘Police make areas safer for suburbanites.’

“We saw blue lights go up in high-crime areas; it was like a sign for people to stay out of those areas. I feel like it was the early 2000s when they began,” said Lay.

Creating the perceived sense of safety associated with suburban areas, including policing, is part of what facilitates the process of demographic changes in major cities.

Sites such as Nextdoor and SeeClickFix encourage residents to report various issues, from car break-ins to graffiti, for resolution. These methods rely heavily on collaboration with law enforcement and public works officials, but also limit community members’ ability to resolve and express concerns together.

The desire to live in an environment that is free of violence, building decay and trash is obviously not unreasonable. I am certain that many long-term residents in urban areas have long wanted to see these changes. The issue is that local governments only invest in these changes when the demographics shift, and that the strategies of “safety” fit the new demographic as well.

The presence of law enforcement does not equal safety in many inner cities, but in urban environments undergoing gentrification, it is common to witness increased policing.

Not only does gentrification push residents out of their homes, it can make them feel unwelcome, or even feared, on their own streets. “

I’m going to have a shirt made,” my partner said, once again returning from walking the dogs, “that says, ‘I’m not a criminal, I’m just from here.’”

Although interview participants overall were not optimistic about the possibility of stopping gentrification, they did have words, advice and requests for new residents.

“Are you moving into the community with the intentions of contributing to the existing culture, by supporting our businesses, or are you coming to disrupt it?” asked Bie Aweh of Boston. “If the answer is disrupt, then please don’t move here.”

“Consider the history of the neighborhood; understand the relationships that are among the neighbors,” Oakland’s Galloway concluded.

Why today’s teens aren’t in any hurry to grow up

(Credit: Getty/AntonioGuillem)

Teens aren’t what they used to be.

The teen pregnancy rate has reached an all-time low. Fewer teens are drinking alcohol, having sex or working part-time jobs. And as I found in a newly released analysis of seven large surveys, teens are also now less likely to drive, date or go out without their parents than their counterparts 10 or 20 years ago.

Some have tried to explain certain aspects of these trends. Today’s teens are more virtuous and responsible, sociologist David Finkelhor has argued. No, says journalist Jess Williams, they’re just more boring. Others have suggested that teens aren’t working because they are simply lazy.

However, none of these researchers and writers has been able to tie everything together. Not drinking or having sex might be considered “virtuous,” but not driving or working is unrelated to virtue — and might actually be seen as less responsible. A lower teen pregnancy rate isn’t “boring” or “lazy”; it’s fantastic.

These trends continued even as the economy improved after 2011, suggesting the Great Recession isn’t the primary cause. Nor is more schoolwork: The average teen today spends less time on homework than his counterparts did in the 1990s, with time spent on extracurricular activities staying about the same.

To figure out what’s really going on, it’s worth taking a broader look at today’s teens — a generation of kids I call “iGen” — and the environment they’re living in.

A different culture, a slower path

Working, driving, drinking alcohol, having sex and dating have one thing in common: They are all activities adults do. This generation of teens, then, is delaying the responsibilities and pleasures of adulthood.

Adolescence — once the beginning of adulthood — now seems to be an extension of childhood. It’s not that teens are more virtuous or lazier. They could simply be taking longer to grow up.

Looking at these trends through the lens of “life history theory” might be useful. According to this model, whether development is “slow” (with teens taking longer to get to adulthood) or “fast” (getting to adulthood sooner) depends on cultural context.

A “slow life strategy” is more common in times and places where families have fewer children and spend more time cultivating each child’s growth and development. This is a good description of our current culture in the U.S., when the average family has two children, kids can start playing organized sports as preschoolers and preparing for college can begin as early as elementary school. This isn’t a class phenomenon; I found in my analysis that the trend of growing up more slowly doesn’t discriminate between teens from less advantaged backgrounds and those from wealthier families.

A “fast-life strategy,” on the other hand, was the more common parenting approach in the mid-20th century, when fewer labor-saving devices were available and the average woman had four children. As a result, kids needed to fend for themselves sooner. When my uncle told me he went skinny-dipping with his friends when he was eight, I wondered why his parents gave him permission.

Then I remembered: His parents had six other children (with one more to come), ran a farm and it was 1947. The parents needed to focus on day-to-day survival, not making sure their kids had violin lessons by age five.

Is growing up slowly good or bad?

Life history theory explicitly notes that slow and fast life strategies are adaptations to a particular environment, so each isn’t inherently “good” or “bad.” Likewise, viewing the trends in teen behavior as “good” or “bad” (or as teens being more “mature” or “immature,” or more “responsible” or “lazy”) misses the big picture: slower development toward adulthood. And it’s not just teens – children are less likely to walk to and from school and are more closely supervised, while young adults are taking longer to settle into careers, marry and have children.

“Adulting” – which refers to young adults performing adult responsibilities as if this were remarkable — has now entered the lexicon. The entire developmental path from infancy to full adulthood has slowed.

But like any adaptation, the slow life strategy has trade-offs. It’s definitely a good thing that fewer teens are having sex and drinking alcohol. But what about when they go to college and suddenly enter an environment where sex and alcohol are rampant? For example, although fewer 18-year-olds now binge-drink, 21- to 22-year-olds still binge-drink at roughly the same rate as they have since the 1980s. One study found that teens who rapidly increased their binge-drinking were more at risk of alcohol dependence and adjustment issues than those who learned to drink over a longer period of time. Delaying exposure to alcohol, then, could make young adults less prepared to deal with drinking in college.

The same might be true of teens who don’t work, drive or go out much in high school. Yes, they’re probably less likely to get into an accident, but they may also arrive at college or the workplace less prepared to make decisions on their own.

College administrators describe students who can’t do anything without calling their parents. Employers worry that more young employees lack the ability to work independently. Although I found in my analyses that iGen evinces a stronger work ethic than millennials, they’ll probably also require more guidance as they transition into adulthood.

Even with the downsides in mind, it’s likely beneficial that teens are spending more time developing socially and emotionally before they date, have sex, drink alcohol and work for pay. The key is to make sure that teens eventually get the opportunity to develop the skills they will need as adults: independence, along with social and decision-making skills.

For parents, this might mean making a concerted effort to push your teenagers out of the house more. Otherwise, they might just want to live with you forever.

For parents, this might mean making a concerted effort to push your teenagers out of the house more. Otherwise, they might just want to live with you forever.

Jean Twenge, Professor of Psychology, San Diego State University

How the ever-bigmouthed crooner has spun criticism into martyrdom

Morrissey (Credit: Getty/Kevin Winter)

Of all the salacious secrets revealed or alluded to in Morrissey’s 2013 autobiography, called “Autobiography,” the most shocking was that he drove a car.

Imagine: Steven Patrick Morrissey, the bitter romantic singer of The Smiths and accomplished solo artist, idol of the terminally glum and broken-hearted, driving an automobile. Checking his mirrors. Buckling his seatbelt. Fiddling with the AM/FM dial. Muttering under his breath when he’s cut off on a crowded L.A. freeway. It’s almost unfathomable. (Yes, he drives a car in the 1992 music video for “My Love Life,” but that could easily be faked.) One imagines Morrissey conveying himself from Point A to Point B — be it from one concert venue to the next, or simply down to the shop to get some tea and Hobnobs or whatever it is Morrissey eats — not by any conventional means, but by, say, crowd-surfing across an endless sea of adoring fans or being ferried in a lavish funerary cart, like the corpse of Alexander the Great. The idea of Morrissey partaking in the world to the extent that he’s signaling turns and merging into traffic and parallel parking is, frankly, unbelievable.

Because Morrissey, you see, has always seemed a man outside-of-time, out-of-place, born in the wrong century or on the wrong planet. He doesn’t belong. His whole thing is not belonging. He is the popstar as Byronic hero, or as highly affected Oscar Wildean archetype, or as hopelessly out-of-touch cartoon, a crooning Montgomery Burns. This is, inarguably, a portion of his appeal, if not the whole of it. Morrissey is aloof and remote, above the fray of daily life or just outside it all together, unmoored from the nagging practicalities of daily life that bog us all down. He is the wanderer above the sea of fog. And so it is frustrating — bewildering, even — when Morrissey is expected to be anything else.

The latest Morrissey micro-scandal sees the singer, who just released a new single and joined Twitter in a seemingly official capacity, criticized for a new T-shirt that depicts a police officer brutally attacking someone, above the words “Who Will Protect Us From The Police?” (the title of a song on his forthcoming record). Described as “politically charged,” the dust-up is nothing compared to that which followed the release of a previous Morrissey T-shirt, depicting author James Baldwin (who is black) wrapped in a Smiths’ lyric (“I wear black on the outside/ ‘Cause black is how I feel on the inside”).

And of course these “problematic” merch designs themselves pale in comparison to the time Morrissey called the Chinese a “subspecies” (citing their negligent treatment of animals). Or the time he called dance music “a refuge for the mentally deficient.” Or his assertions that immigration is compromising English identity, or whatever he’s on about, on any given day. One can only imagine what controversy awaits Morrissey now that he’s on Twitter, a platform infamous for encouraging undercooked, thoughtless incitements.

As a public figure, it’s of course reasonable to take Morrissey to task for his co-opting of the images of police brutality and of American blackness, and for his totally thoughtless, mean-spirited comments about immigration. Yet there’s a relish to burning Morrissey. It feels automated, even performative. This is, after all, the guy who wrote a song called “Bigmouth Strikes Again,” presumably about himself. He has been incautious with his public statements since the 1980s. Being thoughtless and “problematic” is just Morrissey being Morrissey. And it’s precisely why his fans — and the press who giddily draw their knives — love him.

* * *

Remember that scene in Brian DePalma’s “Scarface” when Al Pacino gets wasted at a fancy Miami restaurant and starts snarling at Michelle Pfeiffer and then makes a big scene about being “the bad guy” and how people need him so they can point at him and say, “that’s the bad guy”? Well, Morrissey is just such a bad guy. In his thoughtlessness and arrogant woe-is-me posturing, Morrissey has become a superlative pop cultural scapegoat, right up there with Marilyn Manson and the Slenderman, a rookery of albatrosses hanging heavy around his neck. (Proverbially, of course. Morrissey doesn’t wear feathers or fur.)

Underneath the rote glee with which Morrissey is routinely attacked, there is a seething disingenuousness. After all, standing outside the ebbs of contemporary opinion, the moods of the moment and the fickle vicissitudes of anything like “political correctness” is exactly where we have positioned Morrissey as a cultural figure. Again: in many ways, Morrissey belongs to the past, to the bygone era of English Romantics like Byron, Keats and Shelley. (The Smiths’ “Cemetery Gates” being perhaps the most obvious nod to the latter, who famously wrote a letter to the young Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin asking her to meet him at the cemetery gates, where he would bestow a kiss upon her, above her mother’s grave.) He sings about love, loss, death and self-loathing like a foppish 19th century poet, wilting on some dewey knoll.

Yet this does not make Morrissey conservative in the traditional sense. Just as Romanticism, with its valuing of intense emotion and the pursuit of an authentic inner life, rejected the chilly calculus of modernity and the Industrial Revolution, Morrissey’s witty, highly literate, neo-neo-romantic lyrics and self-consciously solipsistic presentation-of-self stands as its own kind on individualistic rebellion.

On his funny, catchy new single “Spent the Day in Bed,” Morrissey exults cliches of “self-care” to the point of total social detachment. “I love my bed,” he sings, “And I recommend that you stop watching the news/ Because the news can try to frighten you.” He goes on: “Pillows are like pillars,” fortifying himself against the outside world, in his big, comfy bed, which he loves.

As ever, Morrissey’s making himself the villain, withdrawing when we’re all being pestered to engage and even “resist.” In this sense, he offers a contemporary fantasy of aloofness. In an era of media saturation and compassion fatigue, he coos of the decadent option of just straight-up not being bothered. Against looming twin threats of environmental and nuclear apocalypse, Morrissey knows that to turn away is a luxury. He is, like Lord Byron before him, seemingly indifferent to pressing political realities.

The redeeming rub is that it’s all a bit of a joke. “Spent the Day in Bed” makes a mockery of the luxury of indifference and a meta-mockery of himself. This is not to say that Morrissey is something other than indifferent, or callous, or bitter, or forlorn, or even a bit stupid. But self-martyrdom has always been his shtick. In order for him to be so hopelessly tyrannized, he must constantly provide occasion for tyranny. In order to be so beautifully misunderstood, he must give us something to misunderstand. So feigning shock and criticizing Morrissey about his T-shirt designs or his galling lyrics about dropping out of society to roll around idly under the covers, aren’t actual criticisms. They’re the embers stoking the martyr’s funeral pyre he has willingly built for himself.

To paraphrase the villainous, beautifully out-of-touch, self-scapegoating last of the romantics, there’s no need to rake up Morrissey’s mistakes. He knows exactly what they are.

How “Friend Request” squandered an opportunity for good commentary on the Internet

"Friend Request" (Credit: Warner Bros. Pictures)

Internet-based horror films, which are quickly emerging as their own sub-genre, have developed a bad name. The trend was set in 2002 with the abysmal “Feardotcom” and 2003’s even worse “.com for murder,” continued through the dreadful “Pulse” trilogy in the mid-00s, and hasn’t gotten any better this decade with filmmakers tackling social media in flicks like “Chain Letter,” “Smiley,” “The Den” and “Unfriended.”

And now we have “Friend Request,” which just continues the tradition of internet-based horror films not really having anything meaningful to say about the internet — or, for that matter, being particularly scary.

Among the bunch that I just listed (and yes, I’ve seen them all), “Friend Request” falls somewhere in the middle qualitatively. The characters aren’t as obnoxious and unlikable as the ones in “Smiley” and “Unfriended,” but then again, bland and forgettable is only a marginally preferable alternative. Horror-wise, the movie barely delivers at all — there are some effective jump scares and gory images, but nothing that really sticks with you after the credits start rolling.

Most unforgivable, though, is the fact that the plot does very little with the fact that it takes place on Facebook. Instead, the film follows a standard “crazy friend stalks normal person” horror template with virtually no variations. If you tweaked the story to remove Facebook completely, it wouldn’t play that much differently. This might be okay if the movie brought something different to the table aside from its online gimmick, but this shortcoming is fatal to any chance “Friend Request” might have had of being memorable or worthy of distinction.

The shame of it is, though, that you could make a great internet-based horror movie.

The internet is a legitimately terrifying place, one with often terrible real-world consequences. There is a dark web brimming with violent and sexual criminal activity; trolls of all ideological stripes who not only contaminate political discourse, but can actually elect leaders who share their hateful views (see: Donald Trump); cyberbullies who psychologically torment their victims; crooks from thousands of miles away who can steal your identity and destroy your life; and on and on it goes.

The horror genre is perfectly suited to address these issues. Indeed, some of our best social commentary comes from horror films, whether they’re discussing racism (“Frankenstein,” “Get Out”), consumerism (“Dawn of the Dead”), anti-Semitism (“An American Werewolf in London”), classism (“Land of the Dead,” “Hostel: Part II”), sexism (“Ginger Snaps,” “The Cave”) or specific social issues like health care reform (“Saw VI”). The trick is to recognize that the depravity that we see in the real world isn’t that far removed from the terrors that assail us in a good horror flick. It’s just a matter of moving the needle of reality over by a few degrees.

Yet, as with “Friend Request,” none of the internet-based horror films that have made it to mainstream audiences even try to accomplish any of that. They’re just formulaic stories about ghosts, slasher villains, weird cults and other genre tropes that have been lazily transplanted to the internet.

The only one of the bunch that comes close to having anything meaningful to say (and this observation by no means counts as a recommendation) is “Unfriended.” While the characters are terrible people and the story is boringly predictable, it at least has some useful insights about the deplorable behavior that people engage in when they cyberbully one another. While most other internet-based horror movies pay only superficial attention to the dark side of online culture, or base their observations on stereotypes, “Unfriended” posits that cyberbullying exists because the internet’s culture of anonymity has been bred with an ethos of self-absorbed sadism.

It’s not a particularly profound observation, but it at least makes “Unfriended” seem like a story rooted in deeper truths about the internet rather than just an attempt to cash in on neo-Luddite fears.

The potential for good internet-based horror does exist, though; the fact that “Friend Request” is likely to underwhelm at the box office — I was joined in the theater by only two other people, one of them my girlfriend (blameless in the endeavor) — suggests that the window for exploiting this opportunity will soon close. It’s a shame, too, because a genre as inherently versatile as horror could be put to good use in the digital age. For that to happen, horror filmmakers will need to start following in the footsteps of the pioneers who helped create the internet.

That is, they’ll need to learn to think outside the box.

A 106-carat diamond’s epic story of murder and mayhem

Given its epic backstory, the Koh-i-Noor diamond, which weighs in at a whopping 106 carats and currently resides in London as part of the British royal family’s crown jewels, could be called the world’s most controversial jewel.

“This is a rock which has been a kind of focus for desire, bloodshed, murder and mayhem,” said William Dalrymple, the co-author of “Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond.”

Dalrymple and co-author Anita Anand sat down with Salon’s Andrew O’Hehir on “Salon Talks” to discuss the book, which separates facts from fiction around the Koh-i-Noor and features texts translated for the first time into English.

The 13th century diamond, which has been claimed by India, Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan and passed between various rulers over the years, is at its core a living relic of British imperialism.

Dalrymple equates the Koh-i-Noor to the Ring of Power in the Lord of the Rings. “Wherever it goes, people behave extremely badly,” he said. “It was more than the sum of itself,” Anand added. “It came to represent power and dominion, which is why the British coveted it.”

On their international book tour, Anand and Dalrymple presented to audiences in India and Pakistan. The Koh-i-Noor has symbolically left a “heart-shaped wound in the psyche of these countries,” Anand said. “It represents the worst of colonialism in the hearts and minds of the people there.”

Watch the full “Salon Talks” conversation on Facebook.

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET /1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.