Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 254

October 31, 2017

I found love in a haunted prison

(Credit: AP/Matt Rourke)

The Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is a forbidding site. It is the birthplace of “rehabilitative” solitary confinement and for more than a century, held some of America’s most notorious criminals. Stories of abuse, murder, and physical and psychological torture poured out from behind the walls since the day it opened in 1829. And then there are the ghosts, which prisoners reportedly feared as much, if not more, than the physical conditions. Burdened by this history, and the ever-increasing expensive repairs, the city locked the front gates and abandoned the entire site in 1971. It sat vacant for over 20 years, while animal and human scavengers ransacked the ten-acre site and claimed it for their own, before it was rescued in the 1990s by architectural preservationists.

It is not a place most people go to fall in love.

Yet in its own unexpected way, it’s quite beautiful. The feelings of awe and trepidation I felt walking into the neo-gothic institution, enclosed by its 30-foot walls, were overwhelming. Standing in the central rotunda in 2014, beneath the cathedral-esque vaulted ceilings, it was hard to take in: I gazed down cellblock after cellblock, stretching out like spokes on a wheel. All around me were crumbling walls that revealed their history in layers, like rings on a tree: from grey stone, to copper colored brick, to cement, to the green and white flaking paint. Heavy and jagged portions of the floors and walls sat in piles where tree roots and vines had pushed through and wound around the remains of scavenged equipment, a kind of mechanical carnage.

I was there doing research for a book on fear and why and how we engage with scary material. I’ve spent the past 10 years working in the “haunted attraction industry,” a surprisingly booming economy built for people who love nothing more than to have their socks scared off. In this little world, there are few places as grand and influential as ESP. I knew I had to come, because, in addition to the ghosts and whatever animals have made ESP their home, it houses a massive haunted attraction, Terror Behind the Walls. It is the site’s most successful fundraiser, welcoming more than 100,000 guests each season. It’s also one of the most impressive in the industry, thanks in part to the work of the creative director Amy, who makes a living thinking of ways to scare people. In this case, me.

I’d met Amy two years before and was immediately crazy about her. She was into scary stuff, confident, magnetic, oozing charisma. I flushed when she said my name, and I startled easily and often when she tried to spook me. I, on the other hand, hadn’t registered on her radar as anything more than a professional colleague.

But a lot had happened in the two years since I’d met her. ESP was my last trip in a series of adventures I’d undertaken for my book: I had been lost in a dangerous section of Bogotá, pondered mortality in the mysterious Aokigahara Forest in Japan, hung by a cable from the side of the 117-story CN Tower, and survived more anti-gravity roller coasters and Hollywood-caliber haunted houses than I could count. The experiences had made me stronger, braver. I did not scare easily.

That night, standing with Amy in a dark, abandoned prison, I felt my heart race and I wiped my sweaty palms again and again on my shirt to keep the grip on my flashlight. These were classic symptoms of fear — or in my case, a searing crush on an amazing woman.

It was around 10 p.m. and we were the only ones left on site. Amy would take me first through one of their attractions, and then move on to tour the entire site. “Hopefully you won’t get too scared, Margee.” Her smile was equally devious and adorable. I’d never heard a voice like hers — singsong, expressive, yet controlled. She could go from whisper to shout in less than a breath.

Matching her playful tone, I told her I wanted to get scared, that’s what I was there for, that she should do her best. (Amy would later tell me this is when she knew that she had to be at her most terrifying. “It was on,” she said.)

We ventured from one cellblock to the next, encountering rodents of every kind, along with large black beetles that scurried with every labored opening of the heavy wrought iron gates that block each corridor, each cell. We walked through tree branches, tangled vines and sharp hanging stalactites, over roots as thick as a human leg, and carcasses of birds, mice and God knows what else in varying states of decay. Small signs of life and death were everywhere.

All the while, we shared stories of the creepy places we’d been and vendors with the most realistic body parts for the best price. We brainstormed costumes, characters and sets for the perfect scares. Amy even shared her secret recipe for fake blood: between two fear industry professionals, this is a true gesture of intimacy. We eagerly and anxiously made choices about what to say, what to share and what to keep secret, exploring each other’s boundaries like the darkening walls of the old stone prison, boundaries built from histories of loss and pain and a desire to bring light into the dark places.

The time was approaching 2 a.m. and there was only one place left to see: the punishment cells underground, where I would finish out the night.

The punishment cells, or the “Klondike,” are described in a 1924 warden’s report as a row of unsanitary, windowless cells with black painted ceilings and walls, and only an iron toilet and faucet.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” Amy asked as we stood at the top of the steep stairs.

“Yeah, I’ll be fine.” I replied. But I didn’t want to. I didn’t want to descend into a dark, damp, claustrophobic space. I didn’t want to leave Amy.

“OK, step where I step and take your time,” she said. “Be extremely careful. I’ve seen your squirrel moves.”

“I will,” I said with a hint of defiance — and honestly, a touch of ego. I’d survived a lot in my travels.

But Amy stopped me, held my hands and looked me in the eyes.

“I’m serious, Margee. I really don’t want you to get hurt.”

There it was again, the feeling of being lifted gently off the floor and set back down as she said my name. But this time her voice was nothing but sincere, her face nothing but concerned. I believed her.

“Thank you. I’ll be careful.”

I went into the hole and crouched down in the first cell off to the right. The ceilings were only about five feet high, which became unbearably uncomfortable almost immediately. But that wasn’t the worst of it.

There are few places in our well-illuminated world that are pitch black. Even the pin light of a cell phone charger gives us something to orient ourselves against, a way to make sense of where we are. But not here. Reading about these places is not the same as being in them. There is a physical reality that is impossible to replicate.

I was hot and cold at the same time, and the thick damp air made me feel like I was suffocating. I felt frantic; a profound sense of powerlessness and loss of balance in the total darkness came over me. My eyes were open, yet saw nothing. I tried to strain and refocus a thousand times. I waited for my eyes to readjust, but when they didn’t, there was no place left to go except into my own mind. I felt a deep and genuine terror.

I lasted only a little over two hours, and when I left, I took the stairs two at a time. My relief upon reaching the top was quickly replaced with panic as I looked around. It was still dark, and I was disoriented. I desperately scanned up and down the never-ending stone walls, and finally saw a dim light in the distance.

“Amy?!” I shouted and started running towards her. As she stood I wrapped my arms around her and held her tightly.

“You waited here for me?” I said, as tears welled in my eyes.

“Of course,” she said. “I wanted to be close, in case you needed me.”

I did need her, and Amy has stayed true to her word. That night was now over three years ago, and on July 8, this time inside the walls of a historic military fort that is rumored to be haunted, we promised each other that we’ll always be close, that we’ll be each other’s light when darkness inevitably falls. After we exchanged our vows, with friends and family gathered, we stood together, each with one hand on a flaming torch, and fired a 200-year-old cannon into the night sky.

Facebook keeps changing its story, admits Russian posts reached 126 million

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg (Credit: Getty/Justin Sullivan)

Facebook changed its story yet again on Monday, when it admitted that so-called Russia-based operatives had published 80,000 posts on the social networking site over the span of two years, which may have been seen by as many as 126 million Americans.

The details of the reach of Russian-backed posts were provided in written testimony to U.S. lawmakers from Facebook, Reuters reported.

Now executives from three major tech companies, Facebook, Google and Twitter, “are scheduled to appear before three congressional committees this week on alleged Russian attempts to spread misinformation in the months before and after the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” Reuters reported.

Facebook general counsel Colin Stretch wrote in his testimony that the posts had violated the company’s terms of service agreement. Stretch added that the 80,000 posts stemmed from Russia’s Internet Research Agency, a so-called Russian troll farm, and was only a small chunk of Facebook’s content.

“These actions run counter to Facebook’s mission of building community and everything we stand for. And we are determined to do everything we can to address this new threat,” Stretch wrote.

The posts in question were published between June 2015 and August 2017, and Facebook said that a majority of them “focused on divisive social and political messages such as race relations and gun rights,” Reuters reported.

There are still many questions surrounding the role Facebook played in the election and to what degree the apparent Russian influence campaign can be said to have influenced voters.

Moreover, it is still unclear what the fundamental goal of the Russian-backed information was — to elect Donald Trump, or simply to sow confusion and exacerbate political tension — or how it impacted social media users.

In one striking and perhaps counterintuitive example, thousands of Americans apparently attended a New York rally organized on Facebook by a Russian group, just days after Trump won the election last November.

The event was created by the Facebook page “BlackMattersUS,” which is described as a “Russian-linked group that sought to capitalize on racial tensions between black and white Americans,” according to The Hill.

The demonstration was titled, “Trump is NOT my President. March against Trump,” and was attended by between 5,000 and 10,000 protesters, while 16,000 had said they planned to attend. The related post was shared with 61,000 Facebook users. The event shows the potential impacts of “organic content,” meaning posts that have been created and posted by users, rather than as advertisements, The Hill reported.

Facebook has been under pressure to be more transparent in the details it provides to investigators. On Sept. 6, the company revealed that Russian agents purchased ads on the site as well as on Twitter. Facebook said the ads were purchased to sow social discord, and were not geared towards a specific candidate.

At least 8 killed in apparent NYC terrorist truck attack

A New York Police Department officer stands next to a body under a white sheet near a mangled bike along a bike path, October 31, 2017 (Credit: AP/Bebeto Matthews)

Shortly after 3 p.m. on Tuesday afternoon near West Side Highway in Manhattan, a truck struck several people while driving down the bicycle lane, leaving as many as eight people dead, and roughly 16 injured, in what authorities are now calling a terrorist attack, according to multiple news reports.

“This is a tragedy of the greatest magnitude,” New York Police Commissioner James P. O’Neill said during a press conference late on Tuesday afternoon.

NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill on incident in lower Manhattan: “This is a tragedy of the greatest magnitude” https://t.co/FRtLlUHUk0

— NBC News (@NBCNews) October 31, 2017

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio confirmed on Tuesday afternoon that the authorities consider the incident a terrorist attack. “This was an act of terror, and a particularly cowardly act of terror,” de Blasio said.

The vehicle also collided with a school bus from Stuyvesant High School, according to the New York Times. Early reports suggest that the driver, who is in custody, fired gunshots from the truck. Police, however, did not confirm that.

Reportedly, the suspect jumped out of the vehicle with two fake guns and was shot by a nearby on-duty NYPD officer in the abdomen. He was then transported to a nearby hospital, the Times reported. There are currently no other suspects.

President Donald Trump quickly tweeted a condemnation of the attack. “In NYC, looks like another attack by a very sick and deranged person. Law enforcement is following this closely. NOT IN THE U.S.A.!” the president tweeted.

In NYC, looks like another attack by a very sick and deranged person. Law enforcement is following this closely. NOT IN THE U.S.A.!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 31, 2017

The suspect shouted “Allahu Akbar” NBC News reported. The term is Arabic for “God is great.”

The reputed attack occurred a short walking distance from the site of the 2001 terror attacks on the World Trade Center and in the heart of Tribeca, one of the city’s more affluent neighborhoods. It also occurs on the same day as the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade just a short distance north of the scene of the incident.

Students from Stuyvesant High School said they had seen a man shooting from a white pickup truck with a Home Depot logo on it which then collided with a school bus, the Times reported.

The collision with the school bus may have been intentional, but details weren’t immediately clear. Home Depot has since confirmed that the truck belonged to that company.

PHOTO: Scene of incident in lower Manhattan, where multiple people are injured pic.twitter.com/RH4QycdGA1

— NBC News (@NBCNews) October 31, 2017

Video shows blocked off West Side Highway in New York City after incident in lower Manhattan pic.twitter.com/BxuiKtlx4N — NBC News (@NBCNews) October 31, 2017

“I saw a truck – a white pick-up truck – going down the bicycle lane & running people over,” witness describes of Lower Manhattan incident. pic.twitter.com/m9761xX2pA — CBS News (@CBSNews) October 31, 2017

This video appears to show the immediate aftermath of attack in NYC today—mangled bikes along the West Side Highway pic.twitter.com/3gYBz1Z2lT — Jack Smith IV (@JackSmithIV) October 31, 2017

Racism in the workplace is isolating

(Credit: Getty/PeopleImages)

Our awareness of an “ism” can lead to loneliness. In George McCalman’s case, that “ism” was racism. After living much of his life in New York City, feeling part of the community, McCalman, a black man, suddenly felt like an outsider. A white colleague told him that he was employed by their company because of a quota system and “I needed to know my place and that I should not bite the hand that was feeding me.”

“I have described it as an awakening: Where you feel like you’re seeing the world through new eyes for the first time, but it’s been there all along,” McCalman told me on “The Lonely Hour.”

“It’s like your veil of innocence fades away and you just realize the world that you’re living in, that so many of these conversations happen behind closed doors. I remember just feeling like a little frozen in time,” he said.

McCalman wrestled with how to handle the situation. “You know, a byproduct of racism is that black people cannot express their anger publicly. There is still this stereotype that exists about our anger,” he told me. “And so there’s a whole generation — many generations — that restrain ourselves, and I think it’s wired in our bodies. We can express that with each other, but we cannot express that with people outside of our race because we have to be careful.”

Listen to find out what happened and where McCalman is now.

The Lonely Hour is a podcast that explores the feeling of loneliness — and solitude, and other kinds of aloneness — at a time when it may become our next public health epidemic. The show is co-produced by Julia Bainbridge and The Listening Booth. Julia, the host and creator, is an editor and a James Beard Award-nominated writer.

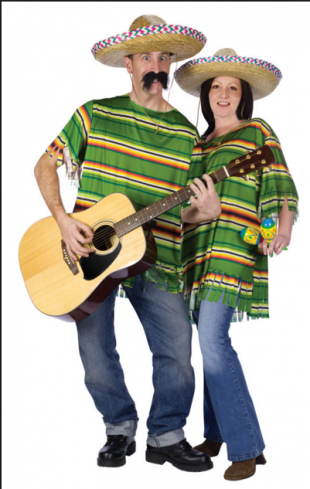

14 Halloween costumes not to wear

(Credit: Stuart Miles via Shutterstock)

Let’s look back at Halloween 2013. That was the year this picture was taken, and went viral, all over the internet.

The person who posted it was Caitlin Cimeno, the delighted-looking woman in the middle. William Filene, the guy on the left, dressed up as Trayvon Martin—a boy who was murdered—including the bloody bullet hole in his hoodie and full blackface. Greg Cimeno, on the right—the guy making a gun with his hand and pointing it at the other guy’s head—is supposed to be George Zimmerman. These three thought this was so uproariously funny that they didn’t just put on the costumes, they took a picture and posted it on social media for the world to see. (This is part of why no one should be surprised Trump got elected!)

They weren’t the first people, and won’t be the last, to have their racism or general awfulness proven by their choice of Halloween costume. Every year, someone inevitably decides it’s a good idea to dress up as an entire race for the day. (And that day often isn’t even Halloween, amiright racist white people?) Still others drag their kids into this whole mess: this little suicide bomber and tiny Hitler can’t be held accountable for what they’re wearing. And that Sexy Donald Trump costume is back again this year, though I prefer this more life-like horrorshow.

So here’s a list of costumes you should be sure to avoid this year, with brief insights on why. And if you’re sick of all this PC stuff blah, blah, liberty something, something, free speech, remember, no one is stopping you from wearing anything and you are not a victim. If you want to be an asshole, be an asshole! Just don’t pretend not to know you’re acting like one.

1. Native American

So many problems here. As a general rule, treating an entire group of marginalized people as a costume you can put on and take off is reductive, offensive and dumb. Reducing people to stereotypes and caricatures, which is what this kind of costume is all about, is pretty much the textbook definition of racism. It’s never okay to appropriate Native American icons and signifiers without regard to context or history, whether it’s for Halloween or Coachella. What you consider a costume may be sacred or deeply meaningful to someone else. Hopefully, you’d rather not be party to continuing our long history of devaluing Native American traditions and beliefs.

As a capper, here’s a video of Native American people trying on “Indian” costumes and explaining why it’s always a terrible idea.

2. Mexican

It was difficult to choose an example here, with so many ridiculous choices. Like this one, or this one, or for god’s sake this one. My only question is, who came up with these costumes and how soon can they start working for the Trump administration?

3. ‘Arab’

Actually, this is listed as a “Sexy Arab” costume, which somehow makes it worse. Anyway, don’t.

4. Geisha

The official name of this costume is “Dragon Lady Geisha.” Who knew before this moment that so many offensive and damaging cultural stereotypes could be sandwiched into one offensive and damaging costume name? (I’m almost impressed, in the worst way.) Putting a dragon on a child’s satin robe, belting it and then calling it anything but “Lazy Orientalism With Stilettos” should be punishable by a fine.

5. Blackface

There’s no one who doesn’t know blackface is offensive at this point. It doesn’t matter if you’re doing some old-school Al Jolson-style blackface or some modern-day blackface you think is an homage to a black actor, musician or character you love from TV. There have been a million articles and discussions about why this is true, and if you’re feeling confused at this point, it’s 2017 and no you are not. If you insist on wearing blackface, you’re an asshole. If you persist in arguing that you should be able to wear blackface because it isn’t racist when you wear it, you’re an asshole. If you wear blackface and pretend not to get it: asshole. There are no more options. (Also, nods to blackface, like this or this, count.

6. Therefore

Just no. To all of this.

7. Sexy Eleven from ‘Stranger Things’

There is zero need to show up to the party as a sexualized child. If you insist on doing some version of “sexy” plus “stupid,” why not go as a sexy slice of pizza or a sexy piece of poop? (Fine, “sexy poop emoji.” Whatever.)

8. Sexy Fake News

This is why we can’t ever have nice things. I don’t even think this is offensive, just another example of a society all too willing to enjoy the unseasonably balmy weather as hell heats to a boiling point. “Spread all the alternative facts,” the seller urges, because we are doomed.

9. Anyone this year who made news just for being awful, from Harvey Weinstein to Bill O’Reilly to any Breitbart employee or Trump staffer. Or Trump offspring. Or Trump spouse.

The world does not need more of these people. Even for one night.

10. Homeless

On any given night, there are nearly 600,000 people living on the street, and more than 200,000 of them are in families, which is incredibly unfunny.

11. Confederate Soldier

The hair on this Trump costume doesn’t even look close to the real thing.

12. Anne Frank

In the current atmosphere, with a white supremacist president, his racist administration and actual neo-Nazis in the streets, now is no time to reduce a Holocaust victim to a costume. (The time for that is called “never.”)

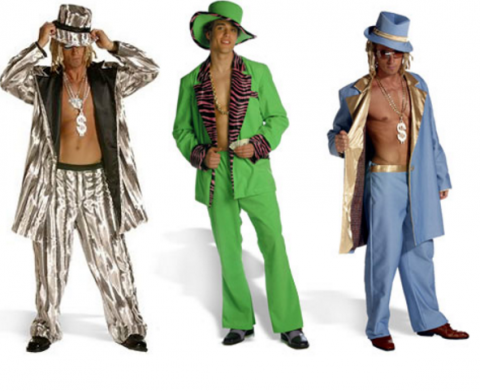

13. Pimp

This costume should be renamed “racist frat boy.” Which can then be shortened to just “frat boy.”

14. What even is this?

Stop it.

Do Democrats really need Wall Street?

(Credit: AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File)

Halloween is coming and fear mongering seems to be the order of the day — not just on the part of Republicans, but apparently no less so on the part of “centrist” and conservative Democrats who are expressing growing anxiety about offending big donors who see politics not as the pursuit of justice but as the pursuit of their interests.

Douglas Schoen, said to have been Bill Clinton’s favorite pollster during his presidency, has taken to the op-ed page of The New York Times to warn center-right party members and friends that ‘all Hell will break loose’ if the Democrats embrace a platform promising “wealth redistribution through higher taxes and Medicare for all” and utilizing democracy to challenge the power of money. Don’t be bewitched by the fantasies of folks such as Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Schoen counsels, for if you do, the American financial elite will not keep the party’s “coffers full.” Indeed, he argues, “Democrats should strengthen their ties to Wall Street,” for “America is a center-right, pro-capitalist nation.”

“Memories in politics are short,” Schoen wrote. And he wrings his hands over the amnesia that robs people of remembering that the center-right assembled under Bill Clinton enabled him to balance the budget, limit government and protect essential programs “that make up the social safety net.” Leaving behind “that version of liberalism,” Schoen writes, has cost Democrats several elections. He even claims that Hillary Clinton lost in Michigan and Wisconsin in 2016 because she “lurched to the left.”

Yes, memories are short indeed, but they are made even shorter by the likes of Schoen. The horrors he prophesies make it clear that he does not want us to remember. He wants us to forget, and therefore to tame our aspirations for social democracy and an economy that serves everyday people instead of the one percent.

Schoen wants us to forget that Hillary Clinton lost the Upper Midwest not because of her supposed “lurch to the left,” but because many working people could not erase from their minds her lavishly paid Wall Street engagements and her adamant refusal to “release the transcripts” of those flattering speeches to the bankers. To many a Rust Belt voter she was the “Goldman Sachs” candidate, something Schoen would consign to the memory hole.

Moreover, he wants us to forget that she likely lost the blue state of Wisconsin, where I live, because she took it for granted. Defeated here by Bernie Sanders in the primary election, she never returned to Wisconsin to campaign against Donald Trump, who visited the state several times and took advantage of the impact Russian-sponsored ads on Facebook and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s voter suppression drive that deterred thousands of minority voters from turning out.

More critically, Schoen also wants us to forget how Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton turned their backs on the Franklin Roosevelt Democratic tradition and proceeded to turn liberalism into neoliberalism. He wants us to forget how Carter alienated working people, opening the door to the conservative administration of Ronald Reagan, by deregulating key sectors of the economy and instituting, in Carter’s own words, “austerity” in government while corporations were exporting jobs, busting unions and devastating communities.

And Schoen, who has been paid handsomely as a lobbyist to several large corporations (something The New York Times did not point out), would erase from our awareness President Clinton’s sabotage of labor and environmental movements as he pushed the GOP’s pro-corporate North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) through Congress, and then proceeded — after declaring “the era of big government is over” in his 1996 State of the Union Address — to encourage ever greater corporate concentration of ownership in telecommunications; inflict “mass incarceration” on individuals (mostly poor) and communities (mostly black); end “welfare as we know it” at the expense of families who needed it, and — egged on by right-wing Republican senators and Wall Street Democrats whom he had named to run economy policy — killed the New Deal law prohibiting commercial banks from speculating with depositors’ money for risky bank activities, thus putting America on the road to the Great Recession of 2009.

Most critically, Schoen wants us to forget the democratic roots and achievements of what historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called “the long Age of Roosevelt.” He utterly effaces from the Democratic story the historic and history-making “center-left coalition” that FDR and the New Dealers built — the coalition of tough-minded liberals and progressives, backed by working people in all their diversity, which regulated ruthless capitalism, taxed the rich (who nonetheless still seemed to be living high on the hog), rebuilt the nation’s infrastructure, improved the environment, created social security, empowered labor, rescued and supported farmers, fueled consumer movements and enlarged the “We” in “We the People.”

Here, again, Schoen suffers his own memory loss — of how this coalition led America in the fight against fascism, expanded democracy at home, enacted the GI Bill and launched a postwar economic boom that not only made the nation richer and stronger, but reduced inequality. Then came legislation for civil rights and voting rights, immigration reform, Medicare and Medicaid, environmental protections and laws to make both the workplace and marketplace healthier.

Schoen would have us forget both how Democrats once upon a time won national and state elections not by deferring to the demands of corporations but by challenging the power of predatory money, enhancing the rights and benefits of working people and directly addressing inequality and poverty. He obviously would not have anyone read “Listen, Liberal,” by Thomas Frank, who described how neoliberal Democrats turned the Party of the People into the Party of Financial and Professional Elites — the 1 Percent.

I’ll wager Schoen actually knows those histories. And yet he wants us to forget them. Why? Because he knows damn well that if we do remember the history that really happened, not the past he is conjuring up, we might well stop fearing. We might in fact start remembering that we are descended from revolutionaries, radicals, socialists, progressives, populists, labor unionists, feminists and civil rights and environmental activists who made America truly great by refusing to bow to the powerful and wealthy and instead fighting to extend and deepen freedom, equality and democracy. The poet Carl Sandburg spoke lyrically of that possibility 100 years ago: When I, the People, learn to remember, when I, the People, use the lessons of yesterday and no longer forget…

Schoen, who spends a lot of time on Fox News as a commentator, appears to be doing the work of Fox & Friends, of conservatives and neoliberals, and that cabal of fixers, white-shoe lawyers and the political strategists and moneyed crowd of Washington that accelerated America’s race to the financial debacles of 2007-09.

Are we to make the Democratic Party all the more the Party of Wall Street? Sure — and follow this pied piper right to oblivion?

So, dear reader, my recommendation is to celebrate Halloween by getting yourself a Douglas Schoen mask, knocking on neighborhood doors and handing out this homemade sign to anyone who answers: “‘The only thing we have to fear is fear itself’ — Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1933. Don’t forget!!

How millions of white Americans bought into a racist myth

Protester holds an image of Trayvon Martin at a rally in Miami, Florida (Credit: Reuters/Andrew Innerarity)

Days after President Donald Trump mocked professional athletes taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality inflicted upon communities of color, namely former San Francisco 49ers’ Colin Kaepernick who first kneeled in 2016, others followed suit. As national media coverage of the athletes’ protests intensified and the president doubled down on his provocations, which soon gave way to threats, the condemnation came. Outlets like the Washington Times implicitly questioned why did the athletes not turn their attention to a more pressing cause: the danger of “black-on-black crime.”

The Washington Times article is only the latest in a long line of attempts to use the racist trope of black-on-black crime to specifically discredit the Black Lives Matter movement and to invalidate very real concerns about police treatment of black communities across the country. Implicit in those attempts is a suggestion of the inherent criminality of black Americans.

This argument is a lie decades in the making.

Statistical data collected by the FBI in 2016 reported that 90.1 percent of black homicide victims were killed by black perpetrators. Similarly, 83.5 percent of white homicide victims were killed by other whites, a figure comparable to that for black victims. And yet the term “white-on-white crime” does not exist in American lexicon. According to Columbia University professor Carla Shedd, “All violence and crime is about proximity” to the point that the label “‘black-on-black crime’ is an unnecessary specification.” Furthermore, the extent to which black individuals are committing crime has been vastly exaggerated in the public imagination. Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics maintains that less than one percent of all black Americans commit a violent crime in any given year, which, stated differently, means that 99 percent of black Americans do not commit crimes to contribute to the black-on-black crime categorization.

Unlike so many other aspects of his presidency, President Donald Trump’s enthusiastic exploitation of “black-on-black crime” is in lockstep with 50 years of conservative dogma. As Professor David Wilson made clear in his book, Inventing Black-on-Black Violence: Discourse, Space, and Representation, “black-on-black crime” is just that: an invention. An invention that proved to be an especially potent weapon in the hands of conservatives, who eschewed centralizing discussions of crime and other challenges around economics and poverty in favor of putting blackness itself on trial, for advancing an agenda and absolving themselves of accountability. Conservative and liberals constructed the myth of black-on-black crime, which proved to be an effective means of shaming and subjugating black communities.

The Reconstruction Criminal Injustice System

In the years after Emancipation, new opportunities for black freedmen were met with vehement opposition from white lawmakers, law enforcement officials, and citizens working in tandem, particularly in the South. Such collusion bore a “winking” justice system that protected black rights in theory, but assisted in abusing them in practice. Though repealed in 1866, the discriminatory “” made a resurgence after the end of Reconstruction. These statutes transformed petty crimes and misdemeanors into felonies that commanded harsher punishments. The ostensible wave of black crime across the South lent credence to the fears of even the most progressive whites that blacks were unqualified for citizenship and inherently more inclined towards criminal behavior. Those fears in turn provided more justification for the criminalization of black life that entrenched Jim Crow.

At the same time, however, while law enforcement officers over-policed black communities for (manufactured) petty crimes, they overlooked or under-investigated the violent crimes that happened in those same communities. One Tennessean official captured the justice system’s disregard for black lives during Reconstruction with this despicable observation: “Nigger life’s cheap now.” Though black-on-black crime would not be officially introduced into the American lexicon until the 1970s, it was clearly on the mind of at least one Louisiana newspaper columnist who offered towards the end of the nineteenth century, “If negroes continue to slaughter each other, we will have to conclude that Providence has chosen to exterminate them in this way.”

Foundations for Invention: The ‘Negro Problem’ in Inner Cities

Decades later, black Americans escaped oppression reminiscent of slavery in the South only to find new challenges in the urban North and Midwest. But as in the South, prejudice thrived. Black labor contributed to the rise of the urban cities, which became bastions of American economic power and physical testaments to the boundless possibilities of the American Dream. By the 1950s, however, the dominance of America’s cities had been usurped by America’s suburbs. Once-reliable sources of investment for cities dried up and turned their sights elsewhere, giving rise to fears about urban decline.

Corresponding white flight from the cities to the suburbs and revived black settlement in those same cities further fueled these concerns. Writer Michael Harrington cautioned in 1962, “There is a new type of slum. Its citizens are the internal migrants, the Negroes, the poor whites from the farms, the Puerto Ricans.” Cities turned to public housing and urban renewal for solutions.

Hope for resolution quickly turned to frustration. Public housing was lambasted as perpetuating the welfare state and the slum-like conditions that necessitated such housing assistance in the first place. Urban renewal efforts proved to be especially counterproductive, often destroying more homes than they created and displacing more people than they resettled.

Problems needed a villain: The villain was found in the poor black communities. Black youth in particular were charged with running out potential investors and wealthier, white families. Concentrated in public housing complexes that were stigmatized as unsafe and debased, black families were blamed for the shortcomings of urban renewal and for keeping those same potential investors and wealthier families away. Speaking in 1999, the St. Louis Home Project captured the national mood of the 1960s and 1970s with this succinct, but explicit denunciation: “Businessmen move out. The African Americans remain.”

Those in the media, with the power to shape perceptions and realities, reinforced the villainization of black communities. Media actors covered the challenges facing America’s cities with narratives that placed black communities firmly at the center of the difficulty. Riots in Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles in the 1960s captured national attention, cementing, in the process, a relationship between black Americans and lawlessness in the eyes of wider society. With the beginning of the 1970s intense media focus on America’s cities transitioned from riots to steadily increasing crime. Elaborate reports on the intersections of murder, robbery, and declining ghettos were disseminated across the airwaves. After drugs, including cocaine and heroin, were introduced to these communities, images of drug-ravaged ghettos commanded the attention of the media and its audiences, leading many to fear “the threat of youth gangs in black areas” strung out on drugs and just itching to terrorize civil (and civilized), law-abiding, (white) suburban communities.

In the eyes of lawmakers, the media, and the public, the difficulties that complicated life in the city were cultural deficiencies on the part of black Americans. Perhaps no other entity more clearly articulated the danger of this culture than the 1965 report “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action” colloquially referred to as the Moynihan Report after its principal author Daniel Patrick Moynihan. “In a word,” the report cautioned, “most Negro youth are in danger of being caught up in the tangle of pathology that affects their world, and probably a majority are so entrapped.” Black families were vulnerable to a “tangle of pathology” that was marked by a culture defined by emasculated men, matriarchal families, welfare dependency, and unemployment.

So the argument went that the arrested development of the black family bred crime and dysfunction. Speaking on the challenges that first gained traction in the 1960s and sounding virtually indistinguishable from the liberal Moynihan, the conservative Center for Reclaiming America opined in 1997s, “Of the last 3 decades… No one disagrees on the problem: high concentrations of poor and poorly educated families in substandard housing–many on welfare and out of work–in an environment rife with crime, dysfunctional families, and domestic violence.” Such cultural degeneracy was endemic to the poor black community. Their challenges constituted a unique “Negro Problem [that] represents a crisis within a crisis, a specific and acute syndrome in a body already ill from more general disorders.”

Destroying Cities: ‘Welfare Queens’ and the Rise of ‘Black-on-Black’ Crime

If the 1960s and ’70s set the stage for the conditions that cultivated the myth of black-on-black crime, the 1980s created a social, political and economic climate that allowed the myth to absolutely flourish. No singular event contributed more to this development than the rise of Reagan conservatism. Amid mounting frustration towards the welfare state, the physical decline in America’s cities, and a very real spike in the frequency of violent crime, conservative Republicans saw an opportunity.

Conservative Republicans, including radio commentator Rush Limbaugh, Department of Education Secretary William Bennett, and President Ronald Reagan, responded to this palpable national mood much in the same way as the lawmakers and media figures of the previous decades: They blamed black communities. The country hardly needed convincing: Decades of stereotypes existed that communicated the undesirability of black families and black youth. But this generation of conservatives took it upon itself to more deeply embed the concept of a “culturally infected inner city space.”

Black families, according to conservative columnist Thomas Sowell, had been “decimated by three decades of disabling programs, welfare bailouts, and affirmative action,” hinting at the “tangle of pathology” admonished by the liberal Moynihan.

The age of the “welfare queen” had begun.

To President Reagan, the malaise of urban America was thanks in large part to the cheats who took advantage of the hard work of taxpayers by participating in programs with benefits of which they were undeserving and the welfare recipients who had eschewed the dignity of hard work for the comfortable dependency of welfare. These undeserving dependents became immortalized in the national consciousness as the welfare people, the pretending disadvantaged, and most famously, the welfare queens who burdened the inner cities, were wholly dependent on the federal government for survival like helpless children, and raised wayward black youths who turned to gang-based violence instead of stable, middle-class values. As Ronald Reagan uplifted the example of Linda Taylor, a black woman living in Chicago who had swindled the federal government out of hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of social safety net benefits, time after time to demand stringent reform, it was clear whom he had in mind while demonizing other welfare recipients. While hard-working (white) Americans took initiative and carried themselves with dignity, welfare queens hid behind cries of racism and classicism in order to continue exploiting the government to support their hordes of children and T-bone steak dinners.

Crime was on the upswing in the 1980s. Mainstream news sources like the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Washington Post treated violent crimes in the city like spectacles, covering the goriest details with specificity and frequency that created a national panic over crime and the black Americans that seemed to be at the center of it. Thus, black-on-black crime emerged as a racialized means of understanding this wave of violence and its confluence with continued urban decline. Not only had they placed a major burden on the resources of struggling cities with their dependency, they were making those same cities hotbeds of violent crime. Both lent further credence to the idea that there was something wrong with black communities. According to conservative St. Louis planner Joe Plann, the city’s deterioration in the 1980s, not unlike that of many others, was due to the fact that “kids became more unstable and started this ‘black-on-black violence’ stuff”.

The Reagan administration and its ideological allies used the pretense of this violence to build constituencies and advance preferred political objectives. Unstable kids, marked as such by their youth, welfare upbringing, and blackness, became known as “superpredators,” a term popularized by conservative political theorists William Bennett, John Walters and John DiIulio. Only one method could control this current wave of crime and the expectant surge that “superpredators” were sure to commit: more punitive policies. Large swaths of conservatives were swept into office on the strength of this rhetoric, including George Pataki in New York, Jeb Bush in Florida, and George W. Bush in Texas. The White House and Congress delivered: Among other measures, the 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 increased the prison sentences and fines for selling or distributing controlled substances. Within two years Congress followed up with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which imposed new mandatory minimum sentences increased maximum sentences for drug trafficking and possession.

The result of the manipulated connection between dying cities and a culture of degeneracy, as denoted by black dependency and black-on-black crime, was that both were given local origins: each other. A culture of depravity within low-income black communities had bred violence that could be seen in the fact that 85 percent of black homicide victims were killed by other blacks in New York City in 1984 and in the destruction of the cities they called home. Or at least that is the message that conservatives circulated in order to downplay the power of structural impacts on producing such tragic realities.

“The truth is we are up against the limits of public policy,” wrote U.S. News and World Report chairman and editor-in-chief Mortimer Zuckerman in 1986 in implicit agreement with Joe Plann’s diagnosis. How else could one explain why “two decades of visible black progress, with billions spent in welfare and training, have also seen the explosive rise of an alienated black underclass whose rootlessness, violence and debased values dominate the ghetto”?

Truths of a Myth

The truth was that conservatives like Zuckerman and even liberals like Moynihan invented new truths that held black communities responsible for the conditions which centuries of slavery and decades of Jim Crow had a major hand in creating.

The truth was that crime was, and is, a reflection of social circumstances.

Previous studies have shown that areas with higher rates of concentrated disadvantage display higher rates of violent crime. Similarly, areas with higher income disparities tend to evidence higher rates of crime as well. To these points, the Department of Justice determined in a 2014 report that poor black families and white families were more likely to be victims of crime than their more financially secure counterparts and at comparable rates. Poverty, segregation, and income inequality each in their own right hamper individuals’ access to necessary resources. Those in power manipulated the levers of influence that, intentionally or unintentionally, kept black people from accessing these necessary resources. The same environment that allowed the myth of black-on-black crime to flourish kept black communities impoverished, segregated, unemployed, and vulnerable to the despair that makes crime a viable solution.

Construction of the black-on-black crime myth began as federal housing programs stimulated homeownership for whites in suburbia and conspired with real estate developers to discourage such ownership for blacks. In 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards maintained that “a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood… any race, or nationality, or individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” Inspired by the efforts begun by the Federal Housing Administration, which created maps to indicate which areas were right (read: white) for investment for use by banks and private lenders, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation further entrenched discriminatory redlining as public policy, offering loans on a selective basis and insuring only those properties that agreed to restrictive covenants.

Chicago provides a particularly insightful case study into the depths to which state-sanctioned discrimination confined black Americans to concentrated poverty. Thanks to the city’s enthusiasm for restrictive covenants, nearly half of all residential neighborhoods in Chicago were inaccessible to black families by the 1940s. After the power to enforce restrictive covenants was compromised, Chicago relied on public housing to keep black communities in check. Between 1950 and the mid-1960s almost all (98 percent) of the public housing complexes built in Chicago were constructed in black neighborhoods.

What the city of Chicago could not accomplish through legislative means, the white residents took upon themselves. White residents formed neighborhood organizations with an eye towards keeping black families away. When appeals and pressure failed, some white residents employed violence. Others simply left the neighborhoods empowered by the social mobility guaranteed by whiteness. Fleeing white families took the prospects of investment along with them. With the white families gone, black families moved in only to have their neighborhoods officially redlined and their property values reduced. Fewer investments meant fewer jobs.

Employment for black Americans in cities was already an issue: By 1950, black unemployment was 7 percent compared to 4 percent for whites. More than 41 percent of black Americans were poor in 1966, making them over 31 percent of the nation’s poor. Liberal politicians responded to this growing unemployment problem with a number of programs like Head Start and Job Corps. Both were introduced by President Lyndon Johnson to shore up black Americans’ educational and employment prospects in the War on Poverty. However, as historian Elizabeth Hinton argued, these programs proved ineffective because they focused, as the Moynihan Report did, on unhelpfully challenging a culture rather than the forces that kept black employment comparatively low and kept black communities in segregated neighborhoods deprived of resources. Doings so allowed the Johnson administration to, as Hinton wrote, distance “itself from accountability for the de facto restrictions, joblessness, and racism that perpetuated poverty and inequality.”

Disparities endured even with employment. Median annual income for black households in 1967 hovered around $24,000, which meant that those households earned only about 55 percent of what white households did. A 1990s study analyzing the employment patterns of youth in Atlanta found that poor job opportunity was connected to neighborhood crime because, as economics holds, crime becomes more attractive in the absence of reasonable, legal alternatives.

Clearly those in power were unaware of the relationship between crime and a barren employment landscape: The riots, which were motivated by economic concerns as they were by those over police brutality, convinced the Johnson administration that, rather than jobs, black communities needed an elevated police presence. This enhanced federal funding to local departments in urban areas marked the transition from the War on Poverty to the War on Crime. Federal funding went towards providing police officers with the resources with which to literally hover around in black neighborhoods rather than the recommendations of the Kerner Commission, which was created in the wake of the riots, including the creation of two million jobs, a universal basic income, and the construction of six million units of affordable housing.

To be sure, violent crime was increasing: The nation’s murder rate and robbery rate increased 30 percent and 26 percent respectively between 1970 and 1974. Black homicide rates specifically were at least 10 times higher than those for whites in 1960 and 1970. But black poverty was up comparatively as well: 30 percent of black Americans were poor in 1974 in contrast to 8 percent of whites.

It was in this context that President Richard Nixon launched his promise to restore “law and order” in the form of the War on Drugs in 1971, justified, as the entrenchment of Jim Crow was, by an ostensible increase in black involvement in crime. The War on Drugs enhanced the presence of drug control agents and, most damagingly, introduced mandatory minimum sentences. The result was a stark increase in the nation’s prison population. An interview with John Ehrlichman, President Nixon’s domestic policy adviser, recently surfaced in which he confirmed what many knew all along: that, again, like Jim Crow, the War on Drugs was executed to criminalize black life. Nixon and his allies saw themselves as having “two enemies: the antiwar left and black people” and that “by getting the public to associate… blacks with heroin… we could disrupt those communities.” “Did we know we were lying about the drugs?” Ehrlichman said. “Of course we did.”

Nixon’s War on Drugs spoke to the essential paradox of black American experience with the criminal justice system: Drug use among black communities was prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law, but murder in these same communities was practically ignored in a throwback to the justice system that defined Reconstruction. One journalist testified to the Kerner Commission in 1968, “If a black man kills a black man, the law is generally enforced at its minimum.” Journalist Jill Leovy made the case in her book Ghettoside that the ineffective justice system described by the journalist is responsible for the preponderance of black-on-black crime. Black Americans, implicitly or explicitly deemed disposable by broader society and, consequently, the law enforcement apparatus, have historically been deprived of protection under the state’s monopoly on violence, the exclusive of the state right to use physical force, which preferred to control them rather than protect them.

Reflecting on the “winking” criminal justice system of Reconstruction that used its power to uphold white supremacy, Leovy suggested that people deprived of resources are more likely, not less, to turn against each other. The absence of legal recourse for individuals who were citizens in name only meant that they often administered justice on their own terms, creating a feedback loop of crime in black communities and police negligence. After all, law enforcement officers refused to “go through the areas where most Negro homicides occur.”

White Americans suffered from the ineffectiveness of the criminal justice too. However, relative to black Americans, they were more likely to have jobs and wealth that helped them participate in the above-ground economy and empowered them with the autonomy to simply move away from each other. State-enforced segregation forced black Americans into ethnic enclaves that rendered them an “occupied people”. When it came to drugs, the criminal justice system acted swiftly and decisively, but allowed murder with few consequences. “It is at once oppressive and inadequate,” Leovy observed. Ironically, as the number of black homicides in cities surged, energizing the black-on-black crime fears of politicians, residents, and media figures, the justice system ostensibly turned a blind eye: During the 1960s and 1970s, prison terms per unit of crime plummeted nationally, recalling the 1968 testimony about the limited enforcement of black crime.

Having engineered a narrative that cast poor black communities as villains responsible for city decline and “superpredators” that preyed on unsuspecting innocents, President Reagan and his conservative allies once again turned to these racist tropes to justify implementing an agenda. Bringing America’s cities back from the disrepair inflicted upon them by the criminality of black youth and the dependency of black families required fiscal conservatism. Fiscal conservatism called for weaning black “welfare queens” from the government teat, a call to which Reagan and his congressional allies responded to with enthusiasm. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) rendered at least half of the almost 500,000 Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) recipients ineligible to participate in the program, while simultaneously cutting the benefits for an additional 40 percent of AFDC families. All told, estimates indicate that OBRA added 600,000 people to the denizens of the nation’s poor in 1982, having forced them below the federal poverty. Reagan’s assault on the welfare state was far from complete, however: His administration cut the budget for the Department of Housing and Urban Development by half between 1980 and 1987.

Residential instability, in which families transition in and out of housing for reasons including an inability to continue to afford rent, falling into foreclosure, or losing access to public housing, can encourage higher rates in violent crime.

From state-enforced segregation to the War on Poverty, conservatives and liberals in power effectively perpetuated the conditions that kept crime in black communities high, cutting them off from investment, employment, and other financially-stabilizing opportunities. At the same time, they laid the blame at the feet of the black families themselves, offering a racialized explanation for these conditions, inherent black dysfunctionality, that absolved them from actively interfering on the behalf of black communities. Indeed, conservative and liberal constructions of the black-on-black crime narrative “banished” important discussions on the effects of racism and poverty on conditions in city communities that effectively “imposed a massive silence” on black communities. Racism, understood in its most extreme forms, was a thing of the past, argued Conservative constructions. Further discussions of it achieved “nothing but [gave] criminals carte blanche to prey on society,” according to columnist Walter Williams in 1985. Suggestions that racism or structural barriers were obstructions to social and economic mobility were no longer acceptable. They had to give way to what Indianapolis conservative politician Stu Rhodes called “the reality of personal responsibility.” In this reality, black communities were responsible for their own living conditions.

From Invention to Incarceration

What is perhaps most devastating about the myth of black-on-black crime was the degree to which it was so undeniably successful. Manufactured public perception of black Americans as villains spilled over into tangible policy that shaped human lives. As during Reconstruction, claims of black criminality became self-fulfilling prophecy as those claims unfairly led to the actual incarceration of black Americans. Johnson’s War on Crime, Nixon’s War on Drugs and Reagan’s “tough on crime stance,” and President Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which expanded the death penalty and the availability of law enforcement officers across the nation, made the prison-industrial complex the monster it is today.

The years between 1980 and 1994 witnessed a massive expansion of the prison population from 500,000 to 1.5 million. Black representation in the prison population increased from 14 percent in 1980 to 51 percent in 1992. More than 32 percent of black men were involved in the criminal justice system in one way or another in 1998. As the prison population grew, resources to other areas fell: California, for example, spent more to incarcerate a child in 1998 than to educate one, $32,200 against $5,327. America compromised its ability to provide for its children’s futures in order to further marginalize black communities.

Conservatives, liberals and their allies built mass incarceration under the pretense of combating black communities misdoings only to, again, more deeply embed the conditions that promoted those misdoings. Black Americans are more likely to be caught up in the net of the criminal justice system, made vulnerable by poverty, unemployment, and what tends to be a higher police presence. Mass incarceration preys and feeds on them, only to spit them back out again into a world that will not hire them, offer them welfare benefits, or allow them to maintain stable housing (private or public) because not only are they poor, they also have criminal records. The myth of black-on-black crime made black life cheap.

Ebony Slaughter-Johnson is a freelance writer and a former research assistant at the Institute for Policy Studies. Her work has appeared in AlterNet, U.S. News and World Report, Equal Voice News, and Common Dreams.

October 30, 2017

Why Papadopoulos spells trouble for Trump

(Credit: Getty/Chip Somodevilla)

While this week began with news that former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort was indicted on 12 counts, including conspiracy to launder money and conspiracy against the United States, the story that could end up being the most troubling for the Trump White House is a guilty plea from a former campaign foreign policy advisor.

According to the legal documents, George Papadopoulos, Trump’s former foreign policy adviser, admitted to lying and omitting information about meetings with a Russian professor with connections to the Kremlin. Papadopoulos was informed about thousands of emails of “dirt” on Hillary Clinton, was encouraged to go to Russia by unnamed senior campaign officials, and tried to set up a meeting between Trump and Vladimir Putin.

I spoke with Stephen Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas, in a video interview for Salon about why the Papadopoulos plea could be a bigger deal than the Manafort indictment.

“Unlike the Manafort indictment, the guilty plea is actually specifically related to the campaign and to the broader concern that there was indeed some kind of relationship between senior Trump campaign officials and the Russian government, Russian officials, et cetera,” Vladeck told me.

During a press briefing on Monday, press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said that the developments have nothing to do with the President and that Papadopoulos was only a volunteer who didn’t have an official capacity on behalf of the campaign.

According to Vladeck, the foolproof evidence of “collusion” is still missing, given the types of charges that have been brought, but in the end, it may not matter. “As the indictment against Manafort and the plea deal by Papadopoulos all underscore,” he said, “the real crimes here may not be the underlying contacts, but rather the cover up.”

Vladeck said he believes that the guilty plea brings up larger questions about what information Papadoupoulos might be providing in order to build up other charges.

“The government’s probably getting something out of Papadopoulos in exchange for allowing him to plead guilty to this relatively minor charge. The million dollar question is, what is the government getting, and perhaps more importantly, who is the government getting it with respect to?”

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook .

Trump’s personal lawyer: Yes Russian contact happened, but it’s totally legal

Jay Sekulow (Credit: AP/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s Monday announcement of a plea bargain with former Donald Trump foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos for making false statements in an FBI interview seems to have definitively put to rest the long-standing claim from the Trump administration that no one affiliated with the president had engaged in any sort of coordination with people associated with the Russian government.

Then-deputy White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders acknowledged how often she and her colleagues were repeating the line in a July news conference,”I think the point is that we’ve tried to make every single time, today and then, and will continue to make in those statements is that there was simply no collusion that they keep trying to create that there was,” she said.

This talking point appears to be dead now in light of the announcement from Mueller that the former Trump aide had met and corresponded with a Russian professor who had assured him of “thousands of emails” from Trump’s then-political rival, Hillary Clinton.

So, it was up to Trump’s personal attorney, Jay Sekulow, to come up with a new line of attack against the investigation Monday in a CNN interview. In the process, he threw Papadopoulos under the front wheels of the metaphorical bus and also defended the idea of a Trump adviser maintaining relations with a hostile foreign power.

Asked by host Wolf Blitzer about whether the administration had reason to worry about what Mueller’s investigation might uncover in light of Papadopoulos’ access to top officials, Sekulow said he was “not concerned.”

The Trump advisor, who was primarily known as a Religious Right lawyer before being hired on by the president, was quick to note that “these weren’t activities that were illegal.”

“If you look at what, again, George Papadopoulos’s plea is, the actual plea that he entered into was, again, a false statement about a timing as to when he talked to somebody about Russian activities,” he said.

Sekulow continued, trying to portray Papadopoulos’s contacts as perfectly normal, “That is, in and of itself, a conversation that someone would have regarding a foreign government whether it was Great Britain, Russia, or anybody else, those are not illegal activities,” he said. “That’s not an inappropriate activity.”

Sekulow then stressed that Papadopoulos’ true crime was to have misled investigators. “The crime was lying about the timing of it [his calls to the Russian professor] to the agent.” Yes, that was the true crime. Yes.

The devil and Aunt Sis: Horror films and my Holiness childhood

"The Exorcist" (Credit: Warner Bros.)

When I was eight years old, my aunt took me to see “The Exorcist,” and I spent the next several years worrying that I would be possessed by the devil. This was not a far leap of the imagination for me. My parents and I attended a holiness church, and we lived in a place where ideas of things like demonic possession and brimstone-hellfire were not out of the question by any means. My parents went to church all the time but did not force me to go, although they certainly wanted me to and encouraged me to the point of coercion.

When I wasn’t there, I was with Sis, my wild aunt who lived alone in a little trailer near the banks of the Laurel River, perpetually smoking Winston Lights and drinking black coffee and either listening to record albums or watching scary movies on the late show. Sis often begged for my mother to let me stay with her on the weekends, particularly on Sunday nights so we could watch “Murder, She Wrote” together. At the time, I just thought she was terribly lonely, since she had lived there alone as long as I could remember. In retrospect, I wonder if she wasn’t keeping me from having to go to church every time the door was cracked.

Sis and I connected on many levels, but mainly through movies and music. She had very eclectic taste. She loved everything from Don Williams to George Michael, from Patsy Cline to Tom Petty to Prince. Sometimes we danced to a particularly good song, often supplied by ELO or John Mellencamp.

Sis especially adored thrillers and horror films. She loved Hitchcock, but only his scary ones. “The Birds” was a favorite. “Psycho,” “Frenzy,” “Marnie.” “That old Mrs. Danvers is a pure-D bitch from hell,” she’d say of the housekeeper in “Rebecca,” and I was dutifully appalled by her language, since I lived in a house in which even playing cards were frowned upon. Cursing was certainly one thing that would send a person straight to hell. When I mentioned this to Sis, she’d say, “I’d bet you every one of that church bunch does something worse than say a bad word occasionally like me.” A pause while she took a deep hit on her cigarette. “Bunch of Harper Valley hypocrites if you ask me.”

When my cousins and I stayed at Sis’s we especially liked playing in the back bedroom because the closet had a folding door which was perfect for playing “Psycho.” One of us would get into the closet and do our best impression of Janet Leigh showering, while the other one took on the steely gaze of Norman Bates. Whomever was playing Norman threw the closet door/shower curtain aside with much aplomb and pantomimed stabbing whomever was in the “shower” until they fell to the floor with one eye largely open. Another cousin had been sounding out the terrifying violin score the entire time. Sometimes Sis watched our reenactments and clapped with her cigarette clutched between her teeth, one eye squinting against the smoke.

Sis was not opposed to gore. One of her favorite movies was John Carpenter’s slasher classic “Halloween.” She had a special penchant for the “Friday the 13th” movies, which were especially terrifying for me because they took place at the lake. Every year, our entire family went on our one vacation to a lake in the mountains a couple hours south. I spent many nights lying awake in my tent, waiting for Jason Voorhees to slice through the thin fabric and reveal his banged up hockey mask to me just before he plunged a machete through my chest and the cot upon which I slept. Each movie always seemed to have at least one impalement that took place on a bed. Regardless, Sis took me to see all of them. I was nine when the first “Friday the 13th” came out.

But a year before, she took me to the 1979 re-release of “The Exorcist” at the Cinema Four in Corbin, Kentucky. What I remember most about seeing it the first time: the scene where Regan’s head turns completely, cracklingly around; Sis putting her hand over my face only once — the infamous scene where Regan uses a crucifix in a very troubling way; looking up at my aunt smoking furiously with one hand and taking great handfuls of popcorn with the other one as she watched the film, transfixed, and unaware that I was so terrified I had slid down into the seat so I couldn’t see the action onscreen. I also remember leaving. A woman caught sight of me exiting the theater, holding onto Sis’s hand. “I can’t believe you brought that little boy to a movie like this!” she said, not so much chiding as she was so amazed she had to articulate it. “Are you scared to death, honey?” Sis steered me on out, not saying a word, but fixing her eyes on the woman’s face in such a way that she was very clearly telegraphing: Mind your own damn business, lady.

I wasn’t old enough then to understand that I had just seen a masterpiece. I didn’t know back then that “The Exorcist” is not only a nearly perfect horror film but also a mediation on belief. For me at the time, it was just a scary movie. In fact, it was the scariest movie I had ever seen. I’m not sure if Sis thought of it much more than that, either. She loved the thrill of being scared, of being startled into jumping and seeing others in the audience do the same. She got tickled at people who screamed during scary films and would laugh at them on the car ride home. “Did you hear that one woman squeal?” she asked, squinting against oncoming headlights. “If I was that scared I believe I’d just stay at home.”

Sis didn’t even seem to be much concerned about the enormous amount of vulgarity in the film, despite the fact that the language caused a national debate about child actors handling such words. She did know, however, that my parents would have been aghast had they known we went to see “The Exorcist.” Since the movie had premiered six years earlier, it had become widely known as not only terrifying but also as pushing the boundaries of good taste. Even people like my parents, who thought it was a sin to go to the movies and knew nothing about pop culture, had heard about it. Violence and gore were okay by folks like them. Coarse language and any hint of sexuality were not. So, once we got back to Sis’s trailer and heard my parents pull into the driveway to pick me up, she told me not to tell them what we had seen. “They’d die if they knew we saw that. Tell them we saw ‘Norma Rae.’”

“You mean lie?” I was beside myself. In one day alone I had greatly increased my chances of going to hell and/or demonic possession.

“A little lie like that won’t hurt nobody,” she said. “If they don’t want to be lied to they shouldn’t be so uptight.”

Now, as a parent myself, I think a lot about Sis’s judgment. I did spend the next few years convinced that a demon like the one who overtook sweet little Linda Blair would slide down my throat at night when I least expected it. I lived in constant fear of being susceptible to possession just by not being faithful enough, good enough. But nowadays I think what I was taught at church haunted me more than any films I saw. By nature I was someone who was constantly questioning the constraints of the church: Why was cussing worse than ignoring those who needed our help the most? Why was going to the movies a sin worse than being racist, homophobic and sexist? The questions were endless. By the time I was a senior in high school, I had watched “The Exorcist” a few more times on our VCR and had come to understand that nothing else had ever made me examine my own belief system as profoundly as that film. Church certainly hadn’t set me to self-study with as much fervor as this movie reviled by every church-goer I knew.

Horror movies could be more than a thrill to make you jump in your theater seat. They could be a way to God.

That same year she took me to see “The Exorcist,” we also saw “The Amityville Horror,” “When A Stranger Calls” and “Alien” (my older cousin was with us that time and covered my eyes when Sigourney Weaver stripped down to her underwear, but I could see between her fingers and now that scene is the most vivid memory of the film for me). We would go on to sit through the “Friday the 13th” and “Halloween” series. We saw all of the “Nightmare on Elm Street” movies together. Throughout the ’80s we watched “The Shining,” “The Fog,” “The Evil Dead,” “Poltergeist,” “Pet Semetary,” “The Fly,” “Creepshow,” “Cujo.” Meanwhile, my parents assumed we were going to see sunny musicals and family dramas.

Even after I graduated high school I continued to go to the movies with Sis, but it was more sporadic, and I tended to only take her to see horror films I had already seen with my friends and knew that she would love: “Body Parts,” “Misery,” “The Silence of the Lambs,” “The Ring.” And then, I stopped going to the movies with her. I saw only one film with her in the years before her death: a terrible remake of “The Omen,” back in 2006. We hadn’t been to the movies together in so long. I had gotten so caught up in my work, in my daughters, in love. But one evening I went to visit her, and she told me how badly she wanted to go to the movies again. “There’s a new scary movie out I want to see,” she said. She was 70 years old but already not remembering everything too well. “It’s one I saw way back. They’ve remade it, I think.” She couldn’t put her finger on the name of it, but I figured it out. “I miss us seeing scary movies together,” she said, and she was not a woman who revealed her aloneness to people. This admission had been hard for her, so I made sure we went to the cinema. She loved it despite my own disappointment. At one point in the film, a priest is killed by a lightning rod that sails through the air to impale him. I looked over to find her unfazed. She shoveled popcorn into her mouth while blood gushed from his chest.

She passed away a few years ago and now I carry the grief with me every day, pulsing in the bottom of my belly like the little girl trapped in her own body who writes “Help Me” from inside her torso after the demon has taken over. One of the ways I am reunited with her is when I go see a great scary movie. She would’ve loved “The Conjuring” films. She would have delighted in “Sinister” and “Insidious” and “The Boy.” Recently, when we were leaving the theater after seeing “It,” I was surprised to see a little boy trailing just behind a woman that appeared to be his mother. He was about eight years old. At first I was shocked to see such a young child leaving such a scary movie, and wondered at a parent who would take him. But then I thought of Sis. I thought of myself, walking beside her back then. And I laid my judgment aside.