Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 249

November 5, 2017

How the government can make disasters wose

Local residents wade through flooded streets after Hurricane Harvey (Credit: Getty/Mark Ralston)

As Hurricane Harvey roared toward the Texas coast in late August, weather models showed something that forecasters had never seen before: predictions of four feet of rainfall in the Houston area over five days — a year’s worth of rain in less than a week.

“I’ve been doing this stuff for almost 50 years,” says Bill Read, a former director of the National Hurricane Center who lives in Houston. “The rainfall amounts … I didn’t believe ‘em. 50-inch-plus rains — I’ve never seen a model forecast like that anywhere close to accurate.

“Lo and behold, we had it.”

That unbelievable-but-accurate rain forecast is just one example of the great leap forward in storm forecasting made possible by major improvements in instruments, satellite data, and computer models. These advancements are happening exactly when we need them to — as a warmer, wetter atmosphere produces more supercharged storms, intense droughts, massive wildfires, and widespread flooding, threatening lives and property.

And yet the Trump administration’s climate denial and proposed cuts threaten these advances, spreading turmoil in the very agencies that can predict disasters better than ever. The president’s budget proposal would slash the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s budget by 16 percent, including 6 percent from the National Weather Service.

Besides hampering climate research, the cuts would jeopardize satellite programs and other forecasting tools — as well as threaten the jobs of forecasters themselves. And they may undermine bipartisan legislation Trump himself signed earlier this year that mandates key steps to improve the nation’s ability to predict disasters before they happen.

It’s hard to overstate how backward that seems after the hurricane season we’ve just witnessed, as well as the deadly wildfires in California, the climate-charged droughts and deluges and, well, you name it. Just when we need forecasting to be better than ever — and need our forecasters to be able to go even further, using those predictions in ways that protect people’s lives and livelihoods — the Trump administration wants to cut back?

Here’s how far we’ve come in forecasting: Three-day hurricane forecasts are now nearly as accurate as one-day forecasts were when Katrina struck 12 years ago. Even routine, “will it rain this weekend?” forecasts are better today than you probably realize. A 2015 paper in the journal Nature called the advancements a “quiet revolution,” both because they’ve gone relatively unnoticed by the general public, and because it’s been cheap. The National Weather Service, an agency of the U.S. government, costs taxpayers about $3 per person each year.

Still, knowing what the weather is going to do tomorrow and understanding how best to warn the public about potential risks are two different things. The first is all about physics; the other is about psychology, human behavior, social interaction, the built environment, and much more. You can guess which is easier.

Forecasts for Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall totals might have been stunningly accurate, but the floodwaters still surprised thousands of people. Days after Harvey’s rains ended, first responders in towns throughout southeast Texas were still rescuing families stranded by rising waters that flowed downstream toward the Gulf.

In the interest of saving lives, forecasters have started moving from simply predicting the weather to attempting to predict the consequences. Call it impact forecasting, an attempt to say what will happen after the rain hits the ground. Scientists hope to answer questions like: Where will water accumulate? Where will floodwaters head? How will it affect people?

The next step is using those “impact forecasts” to get people to safety. Researchers are working to build customized, real-time personal prediction tools that could tell people if their house is likely to flood, or how long they might go without power. There’s also a drive to create easier to understand warning systems, making better use of the latest communication tools and social media.

Besides getting people out of harm’s way, better warning systems could help by letting nonprofits seek donations in advance of a devastating storm, for instance, so they could provide relief more quickly. And they could help public officials do a better job of prepping for the worst.

The need for this new branch of forecasting was highlighted during the height of Harvey’s rains, when the National Weather Service issued a bulletin that put the deluge in stark terms: “This event is unprecedented & all impacts are unknown & beyond anything experienced.”

“This was a good step forward,” says Kim Klockow, a meteorologist and behavioral scientist at the University of Oklahoma who supports the effort to develop impact forecasting. “It admitted something very important,” Klockow says — namely, that the system we have for warning people isn’t good enough.

In fact, experts say the best early-warning systems are ones that start years before the wind picks up and raindrops begin to fall, alerting people who live in vulnerable areas who might be prone to more threats in a climate-charged world.

Following Harvey, Klockow was named to a team of external scientists who will study the National Weather Service’s performance and look for ways to improve. They could start with better flood warnings, she says. “It’s like peering into a black box,” she says. “We give people almost nothing.”

In part, that’s a consequence of insufficient flood-zone maps. Even though rainstorms are getting more intense as the climate warms, FEMA sticks to historical flood data to determine which neighborhoods are required to purchase flood insurance — a policy that’s already leading to skyrocketing losses from floods. A recent study showed that 75 percent of the flood losses in Houston between 1999 and 2009 fell outside designated 100-year flood zones.

If residents don’t know their home is at risk of flooding, they’re less likely to consider that it might, even when a major storm is forecast. So it’s no surprise that, after floods, people report being caught by surprise.

How to keep them from getting surprised? Talk plainly.

There’s evidence that giving people unambiguous information can help move them to action. Recent research has shown that people often need to see the storm with their own eyes before they take cover. They need to see neighbors boarding up their houses before they do the same.

Read, the former National Hurricane Center director, says the same thing applies to him, despite his years of forecasting experience. “Most people, including myself if I’m really honest about it, are in denial that the bad thing will happen to you.”

Before Hurricane Katrina hit the New Orleans area in 2005, the National Weather Service issued a blunt statement that promised “certain death” should anyone be trapped outside unprotected. A post-storm analysis credited that warning with spurring an evacuation rate of more than 90 percent. Read says that’s why the Weather Service is shifting its focus toward making impending storms feel as real as possible to those in its path.

Forecasters need to “personalize the threat,” he says.

Klockow says that she’d like to see flood warnings take a personal approach, too. During a storm, an overlay in Google Street View could show you how high the water is rising in your neighborhood and re-route you away from flooded roads to get you home safely.

The tools to make that happen already exist. Several companies and local governments have already developed mapping tools that to warn of impending floods. North Carolina’s Flood Inundation Mapping and Alert Network relies on 500 measurement stations across the state that transmit their readings back to a central database. When conditions are ripe for flooding, the system’s software estimates possible consequences and alerts emergency managers.

This budding technology, integrated with databases of rescue supplies, could help FEMA figure out where to put aid and supplies before they’re needed.

Other organizations are working on an initiative called “forecast-based financing.” The idea is to allocate money for clearing out storm drains, as well as distributing first aid and water filtration systems, in the days ahead of a storm. Already tested in Uganda, Peru, Bangladesh and other countries, this innovation is now in the process of being scaled up worldwide. It could help organizations like the American Red Cross craft appeals for donations in advance, instead of relying on scenes of devastation after disaster strikes.

All of these efforts and ideas show a lot of promise. Yet even as forecasters have come to understand the importance of developing better advance-warning techniques, their ability to undertake those efforts is being undercut by a White House hostile to funding science.

Earlier this year, along with recommending that Congress gut funding for NOAA, President Trump proposed an 11 percent cut from the National Science Foundation’s budget, slashing funds from the institution behind much of the country’s basic scientific research. If Congress agrees, it would be the first budget cut in the foundation’s 67-year history.

At the National Weather Service, the Washington Post recently reported that the agency couldn’t fill 216 vacant positions as a result of a Trump-imposed hiring freeze. As a result, meteorologists were working double shifts when hurricane after hurricane hit last month and covering for each other from afar.

A forecast center in Maryland, for example, provided days of backup to the National Hurricane Center as hurricanes spun toward shore. National Weather Service meteorologists at the San Juan, Puerto Rico, office complained of “extreme fatigue.” Colleagues in Texas stepped in to give them breaks.

The threat of budget cuts is already crimping federally funded disaster research. A few days after Harvey struck Texas, the Colorado-based National Center for Atmospheric Research — one of the country’s top meteorological research institutions — cut entire sections of its staff focused on the human dimensions of disasters, including impact forecasting.

In an all-staff meeting on Aug. 30, the center’s director explained that the anticipation of tighter budgets forced the decision.

Antonio Busalacchi, president of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, which oversees the center, called the cuts “strategic reinvestments” in a statement to Grist. He said the money saved would be reallocated to “the priority areas of computer models, observing tools, and supercomputing.”

But researchers at the center, called NCAR, say the layoffs will hurt efforts to make forecasts more human-focused and effective.

“Our whole group was cut,” says Emily Laidlaw, an environmental scientist at NCAR, whose work focuses on understanding what puts people at risk from climate change and climate-related disasters. “I would absolutely say that these cuts make people less safe.”

Read, the former hurricane center chief, says increases in supercomputing power shouldn’t come at the expense of developing forecasts that work better for people.

“You can’t drop one for the other,” he says.

The cuts to the National Center for Atmospheric Research will result in the loss of 18 jobs. That may not sound like a lot, but consider that these were some of the only scientists in the United States working to prepare our country’s system for predicting disasters in an era of rapid change.

In that context, the recent revolution in meteorology and pitfalls in preparedness become a powerful metaphor: We know that if we stick to our current course, the future will be bleak. Acting on the forecast of a warmer planet in a way that helps us to usher in a safer and more prosperous future is completely possible, and the stakes keep getting higher.

One-third of the U.S. economy, some $3 trillion per year, is subject to fluctuations in the weather, and millions of people endure weather disasters every year — a number that keeps going up as climate change boosts the frequency and intensity of storms.

Despite excellent weather forecasts, hundreds of people have lost their lives, and billions of dollars in economic value have been lost during this year’s record-breaking hurricane season. In some especially hard-hit places, like Barbuda, Dominica, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, recovery will take years, or longer.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Get people out of a hurricane’s path, put aid workers and supplies in the right place, and a raging storm might not lead to a catastrophe.

We are living in a golden age for meteorology, but we haven’t yet mastered what really matters: knowing in advance exactly how specific extreme weather events are likely to affect our lives. Getting that right could usher in a new era of disaster prevention, rather than the current model of disaster response.

Dark matter: The mystery substance in most of the universe

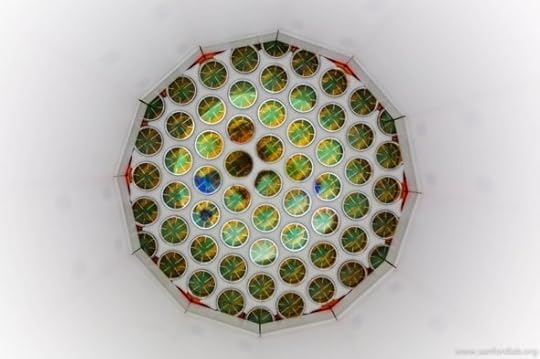

Sensors on the Large Underground Xenon dark matter detector can register the emission of just a single photon from a dark matter interaction within the detector's giant xenon tank. So far, however, no signs of dark matter have been seen. (Credit: Matt Kapust, Sanford Underground Research Facility)

The past few decades have ushered in an amazing era in the science of cosmology. A diverse array of high-precision measurements has allowed us to reconstruct our universe’s history in remarkable detail.

And when we compare different measurements – of the expansion rate of the universe, the patterns of light released in the formation of the first atoms, the distributions in space of galaxies and galaxy clusters and the abundances of various chemical species – we find that they all tell the same story, and all support the same series of events.

This line of research has, frankly, been more successful than I think we had any right to have hoped. We know more about the origin and history of our universe today than almost anyone a few decades ago would have guessed that we would learn in such a short time.

But despite these very considerable successes, there remains much more to be learned. And in some ways, the discoveries made in recent decades have raised as many new questions as they have answered.

One of the most vexing gets at the heart of what our universe is actually made of. Cosmological observations have determined the average density of matter in our universe to very high precision. But this density turns out to be much greater than can be accounted for with ordinary atoms.

After decades of measurements and debate, we are now confident that the overwhelming majority of our universe’s matter – about 84 percent – is not made up of atoms, or of any other known substance. Although we can feel the gravitational pull of this other matter, and clearly tell that it’s there, we simply do not know what it is. This mysterious stuff is invisible, or at least nearly so. For lack of a better name, we call it “dark matter.” But naming something is very different from understanding it.

Astronomers map dark matter indirectly, via its gravitational pull on other objects.

NASA, ESA, and D. Coe (NASA JPL/Caltech and STScI), CC BY

For almost as long as we’ve known that dark matter exists, physicists and astronomers have been devising ways to try to learn what it’s made of. They’ve built ultra-sensitive detectors, deployed in deep underground mines, in an effort to measure the gentle impacts of individual dark matter particles colliding with atoms.

They’ve built exotic telescopes – sensitive not to optical light but to less familiar gamma rays, cosmic rays and neutrinos – to search for the high-energy radiation that is thought to be generated through the interactions of dark matter particles.

And we have searched for signs of dark matter using incredible machines which accelerate beams of particles – typically protons or electrons – up to the highest speeds possible, and then smash them into one another in an effort to convert their energy into matter. The idea is these collisions could create new and exotic substances, perhaps including the kinds of particles that make up the dark matter of our universe.

As recently as a decade ago, most cosmologists – including myself – were reasonably confident that we would soon begin to solve the puzzle of dark matter. After all, there was an ambitious experimental program on the horizon, which we anticipated would enable us to identify the nature of this substance and to begin to measure its properties. This program included the world’s most powerful particle accelerator – the Large Hadron Collider – as well as an array of other new experiments and powerful telescopes.

Experiments at CERN are trying to zero in on dark matter – but so far no dice.

CERN, CC BY-ND

But things did not play out the way that we expected them to. Although these experiments and observations have been carried out as well as or better than we could have hoped, the discoveries did not come.

Over the past 15 years, for example, experiments designed to detect individual particles of dark matter have become a million times more sensitive, and yet no signs of these elusive particles have appeared. And although the Large Hadron Collider has by all technical standards performed beautifully, with the exception of the Higgs boson, no new particles or other phenomena have been discovered.

At Fermilab, the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search uses towers of disks made from silicon and germanium to search for particle interactions from dark matter.

Reidar Hahn/Fermilab, CC BY

The stubborn elusiveness of dark matter has left many scientists both surprised and confused. We had what seemed like very good reasons to expect particles of dark matter to be discovered by now. And yet the hunt continues, and the mystery deepens.

In many ways, we have only more open questions now than we did a decade or two ago. And at times, it can seem that the more precisely we measure our universe, the less we understand it. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, theoretical particle physicists were often very successful at predicting the kinds of particles that would be discovered as accelerators became increasingly powerful. It was a truly impressive run.

But our prescience seems to have come to an end – the long-predicted particles associated with our favorite and most well-motivated theories have stubbornly refused to appear. Perhaps the discoveries of such particles are right around the corner, and our confidence will soon be restored. But right now, there seems to be little support for such optimism.

In response, droves of physicists are going back to their chalkboards, revisiting and revising their assumptions. With bruised egos and a bit more humility, we are desperately attempting to find a new way to make sense of our world.

In response, droves of physicists are going back to their chalkboards, revisiting and revising their assumptions. With bruised egos and a bit more humility, we are desperately attempting to find a new way to make sense of our world.

Dan Hooper, Associate Scientist in Theoretical Astrophysics at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and Associate Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago

How to bring extinct species back to life (and why we may not want to)

Rise of the Necrofauna: The Science, Ethics, and Risks of De-Extinction by Britt Wray (Credit: Greystone Books/Arden Wray)

Michael Crichton’s “Jurassic Park” series popularized the notion that it might be possible to bring extinct animals back to life; yet as with much science fiction, the 1990 book (and subsequent movies) were far ahead of the state of the science. While dinosaurs will likely never be brought back from extinction — at least, not in their original un-spliced genetic form, as no DNA strand can feasibly survive 65 million years or more — we are at a point where it is possible that scientists may soon resurrect recently-extinct species like the passenger pigeon, the Pyrenean ibex, and even Ice Age megafauna like the woolly mammoth.

But just because bringing extinct animals back from the dead is possible does not mean that it is a good idea. Again, “Jurassic Park” was ahead of its time here: In the 1993 film, Jeff Goldblum’s character, Dr. Ian Malcolm, tells the park’s CEO, “your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” Indeed, there are many things that are scientifically possible, but perhaps murky ethically or morally.

Which brings us back to bringing extinct animals back, a process sometimes called “de-extincting.” Imagine the loneliness of being the only member of your entire species, created in a lab and born from another species’ womb. Some argue that we have a moral obligation to bring back species in the name of restoring ecological balance; yet even in the case of animals that occupied an ecological niche that is now missing, it is difficult to say with any foresight whether or not de-extincting them would actually fix anything.

Britt Wray, a science writer and PhD candidate in science communications, has spend years studying the thorny issue of de-extinction, and its myriad social, ethical and biological implications. Wray has a new book out, titled “Rise of the Necrofauna: The Science, Ethics, and Risks of De-Extinction.” I spoke with her about the brave new world of biology that we’ve only just entered.

In your book, you wrote that despite the idea of de-extinction ranking high in popular consciousness thanks to movies like “Jurassic Park,” there aren’t really that many scientists around the world who are attempting de-extinction. Why is this?

Britt Wray: First, there’s not a lot of funding for de-extinction. There’s not scientific agreement that it is a necessary conservation tool, and therefore we should be working on it. Yet some people are working on it. They’re generally donating their own funds from side laboratory projects, and getting private donations and support from the nonprofit Revive and Restore. [Editor’s note: Revive and Restore is a nonprofit, part of the Long Now Foundation, that is working on funding de-extinction efforts.]

Also, [de-extinction] is simply experimental to the greatest degree that you can imagine. People have only done de-extinction once before successfully, and it’s a relatively fringe activity inasmuch that we don’t have a lot of precedent of it working. Now, there’s a time where people are trying to collect themselves and turn what were once a scattering of fringe science projects into an evolving field, a movement, and it’s just the early days of that.

What animals are scientists interested in de-extincting?

Wray: In terms of the projects that are underway already, we’ve got the woolly mammoth revival project happening in George Church’s lab at Harvard Medical School. There’s also a history of teams in Japan and South Korea trying to clone a mammoth back to life by using cells that they take from frozen carcasses that are pulled out of places like Siberia. However, in order to use cloning as a method, you need a perfectly intact cell with its DNA wrapped up nice and neatly in the nucleus, and that has never been found because when animals die thousands of years ago, contamination from other organism sets in and their DNA decays. Basically, perfect intact cells have been impossible to retrieve from those dead mammoths. That’s why George Church’s team at Harvard are using a different approach, gene editing.

Then there are also other animals like the passenger pigeon… the Tasmanian tiger has been approached before as a project. If they get more funding, they might reboot it. The same team led by Michael Archer in Australia is also working on cloning the extinct gastric brooding frog back to life. That was a really special frog that gave birth out of its mouth — it could turn its stomach into a uterus on demand, which is pretty amazing.

There are other projects that are in the beginning stages, such as the heath hen. We’ve also got back-breeding of the aurochs, which is the extinct ancestor of all of today’s living cattle. We’ve got a project called the Quagga Project, which is using artificial selection to recreate the extinct subspecies of zebra known as a quagga. [Quaggas] had a bare backside and mocha color under their stripes, instead of this dark white that we know zebras to have.

Of these projects underway, which is most likely to succeed?

Wray: Maybe the gastric brooding frog. They’ve already been able to take the nucleus with the DNA of the extinct frog and insert that into the egg cell of its closest living relative, which is the great barred frog, then see that transfer of the extinct nucleus into the donated egg, [and] get stimulated to start [its cells] dividing. They have one chance a year to try this because of the breeding season of the great barred frog. Although they haven’t yet been able to grow those into tadpoles, this year again, in February or March, they’re going to try it and see if they get further than they did before.

The woolly mammoth project is really interesting because George Church is a wildly talented writer of genetic technologies, and [a] scientist who just works in a variety of fields that touch on bioengineering. He predicts that perhaps they’ll be able to recreate the woolly mammoth embryo [via] an Asian elephant embryo [by] about 2019. That’s pretty soon. That’s just the embryo, so it’ll take a lot longer to actually gestate that, grow an animal that would be successful, et cetera. But there’s reason to believe that it would definitely be possible within the next decade from a team like his.

Then, there’s the Passenger Pigeon Project. Ben Novak is working on gene-editing the band-tailed pigeon’s genome, which is the closest living relative to the extinct passenger pigeon, which disappeared only 103 years ago now. He predicts that by 2022, he might be able to show the world some of the engineered birds that he’s produced this way. We’ll just have to wait and see, but it’s not unbelievable that this could happen.

The passenger pigeon example is really interesting to me because, as you’ve written about, there were huge numbers of passenger pigeons.

Wray: Billions.

Billions! What led to their demise, and also, how would our world be different if they were still around? Presumably, they were an important part of the ecosystem in some way.

Wray: Right. It’s really difficult to imagine how colossal this species was, because we have never seen anything like it since their disappearance. It’s said to be the most populous avian species that humans ever interacted with. In 1914, the last passenger pigeon, named Martha, died in the Cincinnati Zoo, but between that point and 50 years prior is really when the bulk of their crash occurred, because humans found them to be a tasty and cheap source of protein and we developed a whole market trade around capturing them.

There are records of a single flock of passenger pigeons taking about 14 hours to pass over a single spot in Southern Ontario, and there are also records of one bullet being fired up into the sky, making as many as 25 to 99 birds come down, because they were flying in layers that thick. It’s just unbelievable, [an] almost mythical scale. They definitely acted as a superorganism because of how many they were — so they had an important functional role to play in the eastern forest of North America.

Now, what happens today in those forests where they once were? [They] often have a closed canopy, meaning that the branches of the trees up high prevent sunlight from coming in and hitting the forest floor. If the sunlight reached the floor, it would cause regeneration of different species and vegetation down there.

The advocates of passenger pigeon de-extinction, especially Ben Novak, who studies them and is trying to recreate them now, say that if we could bring hundreds of thousands, maybe a few million passenger pigeons back, when they come in, they would mimic what the extinct bird did, which was weigh down the tree branches when they would come to roost and nest. They would make bark chip off the trees. They would destroy young saplings or old trees and cause that closed canopy to break down, and the sun would then be able to come through the trees, hit the forest floor.

Because they were such a disturbance, forests, as we see today around the world, generally are able to build the next successive forest after a lot of disruptions. Things like forest fires and hailstorms cause forests to regenerate, and similarly, the argument here is that billions of passenger pigeons caused the forest to create new shoots that would sprout up after the disturbance. People who believe in this project [think] it would be a natural and desirable way to regenerate forests that haven’t been regenerated at that scale since the passenger pigeon went extinct.

In the history of de-extinction, there has actually been one successful instance of an animal being de-extincted, although it only lasted about 10 minutes. Can you talk about this case a little bit?

Wray: That happened in the early 2000s with the bucardo, also known as the Pyrenean ibex, which is a type of mountain goat that lived in the Spanish Pyrenees mountain range. Celia, the last living bucardo, was this female who was monitored in a conservation program, and she was all that was left after humans hunted her and her species out of the wild. One day, her radio collar sent out a signal that something was amiss. The scientists and the conservationists rushed out to see what had happened, and they discovered that she had been crushed to death by a branch that fell from a tree. They couldn’t save her from that, and they knew enough beforehand to try and preserve some of her tissue just in case anything beneficial could be done down the line. They’d already taken some cells from her ear and from her flank and quickly frozen them in liquid nitrogen so that they would be perfectly preserved and intact. Then, a couple of years after she died, they did what’s called somatic cell nuclear transfer — this is the same method of cloning that was used to make Dolly the sheep.

They got one success after many, many attempts — they had to create 57 embryos in order to get one success this way. They took the DNA in the nucleus of one of the cells from the extinct bucardo, transferred it into the egg cell that came from a living goat, stimulated it with a shock, which started it dividing, and planted it in a surrogate goat mom. I think they were able to make seven goats pregnant after 57 embryos were made this way. One baby lived for 10 minutes, but then died due to a deformity on its lung. That’s pretty common with cloning. There’s a lot of failure rates and there’s a lot of congenital diseases that they can be born with.

The whole case of that Pyrenean ibex kind of makes me wonder about the ethical or moral questions driving whether or not humans should de-extinct animals. Given that humans are generally the main driver of extinction on Earth, do you think that we have a moral obligation to be involved in de-extincting animals? What are the ethics of this?

Wray: There are some people who say we have a moral obligation to use whatever tools we have available to us now to bring some of these species back in whatever way, shape, or form that we can if we cause their extinction; that we owe them this, that there are holes in nature we ripped open and now we should fill them in. But I find that there’s a logical disjuncture there, because if we really felt that responsible, and guilty, and motivated by this moral argument, we’d be doing a lot more to help the threatened species that are currently facing extinction than we are. We have a rich opportunity to make a greater impact by concentrating our efforts there than saying that it’s morally just to try and de-extinct animals that we killed for whatever reason there might be.

I think that there are potentially interesting conservation benefits of having aspects of extinct biodiversity back in the world, but that doesn’t necessarily mean cloning extinct animals. Endangered species that can use the tools being applied in de-extinction — for instance, gene editing with tools like CRISPR to put biodiversity into endangered populations right now that have low fecundity, that can’t really make it on their own because they have really, really small amounts of biodiversity in their population. For example, black-footed ferrets… although there’s quite a few of them, they’re really badly inbred. Some of the people who are working on supporting de-extinction projects have also turned their attention to this species to try and figure out how they can bioengineer living ferrets to have more genetic diversity in them, by taking the DNA of long-dead ferrets that used to be more diverse that we have, stored in liquid nitrogen.

Or, take the northern white rhino; there are only three of them left living in Kenya. These types of bioengineering tools are now being applied to help them. They’re effectively a dead species walking. They can’t reproduce between themselves. They’re also all very closely related, so it would be a bad idea. Now, there are a variety of different approaches to resuscitate them with methods that look a lot like de-extinction, and I think that that’s really cool. But it’s challenging to say where do we draw the line. Is it really that much better to help a species when there’s only three left and they’re functionally extinct in the wild? Is that a lot better in moral terms compared to trying to de-extinct them after the last rhino died?

So you’re saying that we could put our efforts towards stopping endangered animals from going extinct in the first place, and that’s easier and probably less resource-intensive than bringing back to life some of the extinct ones?

Wray: Well, I am, but I’m also just pointing out that it becomes really foggy as to where the moral reasoning should sit, because it will be probably just as resource-intensive to [try to stop] the northern white rhino from going extinct, [as] there’s only three of them left. I mean, we need to look at each case individually, I think, and then judge from there.

But most importantly, for animals being de-extincted, we need to know: is there a good habitat that’s available where they could live? Where they could thrive? Where they have all the factors that they need to be able to do well? Otherwise, they’ll just go extinct a second time.

Portions of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity.

# # #

Britt Wray is the author of “Rise of the Necrofauna: The Science, Ethics, and Risks of De-Extinction.”

The best reporting on Manafort, Gates and Papadopoulos

Paul Manafort (Credit: Getty/Brendan Smialowski)

Former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort, his protégé Rick Gates and the less well-known Trump campaign foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos have all faced scrutiny before Monday. Here are our favorite stories on them.

Former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort, his protégé Rick Gates and the less well-known Trump campaign foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos have all faced scrutiny before Monday. Here are our favorite stories on them.

The Quiet American, Slate, April 28, 2016

“Manafort has spent a career working on behalf of clients that the rest of his fellow lobbyists and strategists have deemed just below their not-so-high moral threshold. Manafort has consistently given his clients a patina of respectability that has allowed them to migrate into the mainstream of opinion, or close enough to the mainstream. He has a particular knack for taking autocrats and presenting them as defenders of democracy. If he could convince the respectable world that thugs like Savimbi and Marcos are friends of America, then why not do the same for Trump? One of his friends told me, ‘He wanted to do his thing on home turf. He wanted one last shot at the big prize.’”

Paul Manafort’s Wild and Lucrative Philippine Adventure, Politico, June 10, 2016

“POLITICO found that Manafort worked more closely than previously known with Marcos and his wife, Imelda, in Manila, where Manafort and his associates advised the couple on electoral strategy, and in Washington, where they worked to retain goodwill by tamping down concerns about the Marcos regime’s human rights record, theft of public resources, and ultimately their perpetration of a massive vote-rigging effort to try to stay in power in the Philippines’ 1986 presidential election.”

How Paul Manafort Tried to BS Me—and the World, Mother Jones, July 21, 2016

“Manafort, who for decades has been an adviser to warlords and autocratic thugs overseas, including a Ukrainian leader allied with Russian leader Vladimir Putin, had been spinning furiously; some might call it lying. He probably had not even had time to read the full story and discuss it with Trump. Yet he went straight into denial mode, claiming the Times had misquoted his candidate. But it hadn’t. (Manafort later tried this stunt with other reporters.)”

Secret Ledger in Ukraine Lists Cash for Donald Trump’s Campaign Chief, The New York Times, Aug. 14, 2016

“Handwritten ledgers show $12.7 million in undisclosed cash payments designated for Mr. Manafort from Mr. Yanukovych’s pro-Russian political party from 2007 to 2012, according to Ukraine’s newly formed National Anti-Corruption Bureau. Investigators assert that the disbursements were part of an illegal off-the-books system whose recipients also included election officials.”

Manafort Tied to Undisclosed Foreign Lobbying, Associated Press, Aug. 17, 2016

“Donald Trump’s campaign chairman helped a pro-Russian governing party in Ukraine secretly route at least $2.2 million in payments to two prominent Washington lobbying firms in 2012, and did so in a way that effectively obscured the foreign political party’s efforts to influence U.S. policy.”

Manafort’s Man in Kiev, Politico, Aug. 18, 2016

“All the while, Kilimnik has told people that he remains in touch with his old mentor. He told several people that he traveled to the United States and met with Manafort this spring. The trip and alleged meeting came at a time when Manafort was immersed in helping guide Trump’s campaign through the bitter Republican presidential primaries, and was trying to distance himself from his work in Ukraine.”

Washington Lobbyist And Trump Advisor Paul Manafort Owns Brownstone In Carroll Gardens, Pardon Me For Asking, Feb. 16, 2017

“According to ACRIS, The Federal Savings Bank provided funds of $5,300,000 on the property on January 17, 2017. (The amount needs to be repaid by January 2018). An additional mortgage of $1,200,000 by The Federal Savings Bank was issued on the same day. Genesis Capital Master Fund II, LLC appears to have loaned another $303,750.”

Former Trump Campaign Manager Paul Manafort Took Out $19 Million In Puzzling Real Estate Loans, The Intercept, Feb. 24, 2017

“The raw facts stand out for their strangeness. Since 2012, Manafort has taken out seven home equity loans worth approximately $19.2 million on three separate New York-area properties he owns through holding companies registered to him and his son-in-law Jeffrey Yohai, a real estate investor.”

Paul Manafort’s Puzzling New York Real Estate Purchases, WNYC, March 28, 2017

“Nine current and former law enforcement and real estate experts told WNYC that Manafort’s deals merit scrutiny. Some said the purchases follow a pattern used by money launderers: buying properties with all cash through shell companies, then using the properties to obtain ‘clean’ money through bank loans. In addition, given that Manafort is already under investigation for his foreign financial and political ties, his New York property transactions should also be reviewed, multiple experts said.”

Manafort Still Doing International Work, Politico, June 15, 2017

“One of the people, a lawyer involved in the discussions, said Manafort indicated that he could convince the Trump administration to support any resulting deal, because he’s remained in contact with Trump’s team, and that he played a role in helping to soften Trump’s tough campaign rhetoric on China.

‘He’s going around telling people that he’s still talking to the president and — even more than that — that he is helping to shape Trump’s foreign policy,’ said the lawyer involved in the discussions.”

How the Russia Investigation Entangled a Manafort Protégé, The New York Times, June 16, 2017

“As investigators examine Mr. Manafort’s financial and political dealings at home and abroad, they are likely to run into Mr. Gates wherever they look. During the pair’s heady days in Ukraine, it was Mr. Gates who flew to Moscow for meetings with associates of Oleg Deripaska, a Russian oligarch. His name appears on documents linked to shell companies that Mr. Manafort’s firm set up in Cyprus to receive payments from politicians and businesspeople in Eastern Europe.”

Trump Campaign Emails Show Aide’s Repeated Efforts to Set Up Russia Meetings, The Washington Post, Aug. 14, 2017

“The adviser, George Papadopoulos, offered to set up “a meeting between us and the Russian leadership to discuss US-Russia ties under President Trump,” telling them his Russian contacts welcomed the opportunity, according to internal campaign emails read to The Washington Post.”

These 13 Wire Transfers Are A Focus Of The FBI Probe Into Paul Manafort , BuzzFeedNews, Oct. 29, 2017

“The extent of Manafort’s suspicious transactions was so vast, said this former official, that law enforcement agents drafted a series of “intelligence reports” about Manafort’s financial dealings. Two law enforcement officials who worked on the case say that they found red flags in his banking records going back as far as 2004, and that the transactions in question totaled many millions of dollars.”

November 4, 2017

How a French king’s legacy revealed a loophole in evolution

(Credit: AP Photo/Kamil Zihnioglu)

A little more than 40 years ago, Richard Dawkins wrote his landmark book, The Selfish Gene, and changed our view of evolution forever. Dawkins, drawing on work by several contemporary scientists, made a simple argument, very persuasively, that evolution by natural selection operates on individual genes rather than on the organisms that host them.

A little more than 40 years ago, Richard Dawkins wrote his landmark book, The Selfish Gene, and changed our view of evolution forever. Dawkins, drawing on work by several contemporary scientists, made a simple argument, very persuasively, that evolution by natural selection operates on individual genes rather than on the organisms that host them.

It follows from this selfish gene hypothesis that a genetic mutation that’s harmful to its host — and hence limits its fitness, or ability to reproduce — is unlikely to make it into the next generation and will gradually disappear from the general population. This is because if a gene limits its host’s reproductive ability, it’s effectively limiting its own heritability.

Or so we’ve thought for the past four decades. In a remarkable project combining evolutionary theory, population genetics, historical research, and epidemiology, researchers have now found evidence for a genetic mutation that can be deadly to its host while also being efficiently passed on through generations.

This mutation is responsible for a disease called Leber hereditary optical neuropathy — LHON — which results in blindness and can also cause loss of muscle control, cardiac symptoms, and other neurological problems. The genetic mutation that causes LHON is named T14484C, and it manages to escape natural selection in a manner that’s best described as selfish. The wide range of methods used by the scientists hunting the origins of T14484C in Canada, from historical research and genealogy, to DNA sequencing also represent a potentially game-changing development in studies of human evolution.

The Sun King’s ‘daughters’

The story of T14484C begins in 17th century North America, in the colonies then known as New France. Colonists there included a few hundred French colonists, some migrant workers engaged primarily in the fur trade, and some Jesuit priests – that is to say, it was heavily male with little incentive for families and unmarried women to travel and settle there. In order to incentivize colonization, Louis XIV implemented a 10-year policy of shipping unmarried French women to the colony, encouraging marriage — using generous dowries — with French workers and soldiers.

Between 1663 and 1673, around 800 women travelled to New France under this scheme, married and had children; indeed millions of French Canadians today can trace their lineage back to one of these filles du roi — “king’s daughters.”

The first clues that the T14484C mutation was related to the filles du roiprogram were found in 1998, when researchers noticed that this mutation was unusually common among French Canadians. In a 2005 paper that reads like a genetic detective story, the same researchers used genealogical data from Quebec’s BALZAC database and marriage records to track the T14484C mutation back to a single fille du roi who was married at 18 in Quebec City in 1669. Today this mutation accounts for 89 percent of French Canadians with LHON.

This mutation, inherited from a single mother, survived for so long because of a genetic loophole. It was passed on through each successive mother’s DNA, but it could harm only the sons in every generation.

A majority of our 20,000 genes are present in the nucleus of our cells, and are usually inherited from both our parents. But 37 of them lie elsewhere in the cell, in small capsule-shaped organelles called the mitochondria. These mitochondrial genes can only be inherited from our mothers since a sperm’s mitochondria are destroyed when it enters an egg cell.

This maternal-only inheritance of mitochondria has been theorized to serve as a kind of refuge for mutations that could selectively cause disorders in male hosts but not affect female ones. Such mutations could effectively escape natural selection since their vehicle for reproduction, the mitochondria, is only passed on by mothers, who would remain unaffected by the male-specific disease. This type of mutation, , called the Mother’s Curse (so named and first hypothesized in 2004 by scientists from New Zealand and the US), would be harmful to sons but not to daughters, and would thus be passed on from generation to generation.

Searching history for clues

For years though, the Mother’s Curse remained just a theoretical possibility in humans; there was no evidence the LHON (and the T14484C mutation that causes it) have any effect on a patient’s ability to reproduce.

But in a paper published last month, scientists from a number of Canadian universities completed the T14484C story by describing how this mutation was able to persist for so long in the population and demonstrating for the first time that the Mother’s Curse exists in human populations.

Using extensive analysis of databases containing the life histories and marriage records of early Quebec settlers, the researchers first identified over 2,000 carriers of the T14484C mutation in Quebec history. They then assessed the reproductive fitness of these carriers (men and women) as well as that of the overall population at the time. In keeping with the Mother’s Curse idea, they found that male carriers of the mutation had a 20 percent lower survival rate in their first year of life. They also found that male carriers had a lower probability of getting married, and hence a possibly lower chance of becoming fathers. Clearly, the T14484C mutation possesses some “son-killing” ability.

The story of T14484C proves for the first time that the Mother’s Curse is actually present and active in a human population. It is also, in my opinion, a startling example of how a gene can selfishly escape natural selection in spite of effecting devastating consequences on half its host population.

Apart from being yet another scientific curiosity discovered by evolutionary biology, the tale of T14484C may also change how new technologies in medicine are adopted. Just last year the United Kingdom became the first country ever to approve of a new treatment called mitochondrial replacement therapy. In this procedure, scientists remove the mitochondria that carry harmful mutations from a fertilized egg and replace them with healthy mitochondria from another woman’s DNA. The discovery of the Mother’s Curse in humans makes the case for more widespread adoption of genetic screening, and in some cases, the use of mitochondrial replacement as a kind of counter-curse to harmful genetic mutations that can slip past natural selection.

As the authors note in the final paragraph of their latest paper, studies of human evolution are usually ignored in modern medical practice. Clinical symptoms are often a more visible – and hence, an easier – metric to define diseases than measures of evolutionary fitness deduced from genealogical data.

If anything, the story of the Mother’s Curse illustrates just how important understanding evolutionary biology is, not only to biology but in medicine as well. We are fast approaching a future that will be characterized by personalized medicine, genetic diagnoses, and, possibly, human genetic engineering. The need for a better appreciation of evolution by doctors, ethicists, and even lawyers and politicians, has never been greater.

Conservative hunters and fishers may help determine the fate of national monuments

Rock formations in Gold Butte, which President Barack Obama designated as a national monument. (Credit: AP)

This past spring Pres. Donald Trump ordered a review of more than two dozen national monuments, calling the protected status of these lands an “egregious abuse of federal power.” The review included New Mexico’s Rio Grande del Norte, Katahdin Woods and Waters in Maine and the controversial Bears Ears in Utah. The usual environmental organizations and many Democrats excoriated Trump, of course. But this time some of the fury is coming from a less-expected quarter: hunters and anglers.

Sportsmen and sportswomen don’t tend to fit the “tree-hugger” stereotype that many conservatives ridicule; a plurality of them lean right in the voting booth. Yet many strongly support preserving wilderness areas so they can use them to hunt and fish, and public lands such as national monuments often grant access to thriving wildlife.

Hunting and fishing groups have become increasingly politically active in recent years — an important development, since many of their members make up a significant part of the Republican base. Now that Republicans control Congress and the White House, hunting and fishing enthusiasts’ ideas about conservation may start to shape environmental policy more than in the past. So what does their influence look like in the Trump era? And could they sway issues like the national monuments review?

Hunters and anglers in the U.S. can trace their conservation ethic back more than a century. “Sport hunting was an elite activity, and the elite enforced hunting regulations to cut down on the game killed [commercially], and to set up preserves for themselves,” explains Thomas Dunlap, a professor emeritus of environmental history at Texas A&M University. “Hunters were important, though not the only factor, in the development of conservation.”

Their modern-day counterparts — including U.S. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke — often evoke the memory of Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican whom many consider the “conservation president.” A lifelong hunter, Roosevelt established protections for about 230 million acres of public land during his tenure in office from 1901 to 1909. He also signed into law the Antiquities Act, which gives presidents power to create national monuments.

Today many of the more than 40 million hunters and fishers in the U.S. still believe in this ethic — and many of them also identify with the political right. “Our ranks are traditionally conservative,” says Land Tawney, leader of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. According to a national poll, 42 percent of hunters and fishers are Republicans, versus 32 percent as independents and 18 percent as Democrats. In terms of ideology, 50 percent consider themselves conservative, 37 percent moderate, and 10 percent liberal. The poll, conducted for the National Wildlife Federation, also found that most sportsmen and women see themselves as conservationists. “Even for the most hardcore duck hunters, I still think the conservation mission drives them,” says Rogers Hoyt, president of Ducks Unlimited. “Hunters and fishermen are true environmentalists — they enjoy using the resource, and believe in taking care of the resource.” Tawney says his organization’s efforts “are all aimed towards an end goal: having access to our public lands, and fish and wildlife habitat once you get there.”

Hunting and fishing enthusiasts spend significant amounts of money and effort on conservation as well. Hoyt points to initiatives such as the Federal Duck Stamp program, which have long brought in revenue to protect wildlife and habitats, as have revenues from other hunting and fishing licenses and taxes. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, hunters pay for the majority of wildlife conservation efforts in most states through stamps, tags, and licenses. Many sporting organizations devote substantial funds to promoting environmental issues as well — Ducks Unlimited, for example, has spent millions of dollars conserving wetlands.

“What’s more conservative than stewarding our resources so we have them when we need them? That’s planning today for tomorrow — that’s fundamentally conservative,” says Steve Kline, a Republican and hunter who works for the non-profit Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (TRCP). “We are in a place now where conservation issues have become incredibly partisan, and I think that’s unnecessary.”

Other conservative hunters and fishers echoed these views. “The best word is ‘stewardship’,” says Andy Rasmussen, a lifelong Republican and fisherman, and a field coordinator for Trout Unlimited in Utah. “It’s a conservation ethic — you need to be able to have these [public resources and public lands] managed sustainably, so that future generations can use them.” John Cornell, a Republican, hunter and New Mexico field representative for the TRCP, sees such an outlook as an inherent part of what he does. “I’ve always been a sportsman, and have always been a conservationist by being a sportsman,” he says.

After Trump announced his administration’s review of national monuments, several major hunting and fishing and conservation groups sent a joint letter to the president, asking him not to repeal any of the monument designations. And as Zinke worked through the review this summer, those same groups and others waged a public campaign against changes to the monument designations. They sent letters, voiced their support for monuments on social media, ran ads critical of the review and met with Zinke about the issue.

National monuments matter deeply to many hunters and fishers. A country-wide poll by TRCP and research firm Public Opinion Strategies found that 77 percent of Republicans and 80 percent of Democrats supported preserving the existing national monuments that allow hunting and fishing. Nearly all of the monuments in Zinke’s review currently offer access to both. Sporting organizations say monument designations are important because they safeguard those lands from future mining, oil and gas drilling, and other forms of development.

Despite this rare but solid patch of common ground, conservative hunters and fishers still tend to see themselves as fundamentally different in their philosophy than the standard liberal environmentalist — many support natural resource development and view themselves as active managers of the land, rather than preservationists. “There are not a lot of sportsmen who want to preclude oil and gas development [in general],” Rasmussen explains. “A lot of workers out in the oil fields are hunting and fishing in their time off.” Yet national monument lands and other conserved public lands are largely seen by sportsmen as off-limits to development. “Sportsmen want to make sure that within the monument, habitat is protected,” says Cornell, who hunts in the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument in New Mexico (one of the monuments reviewed by Zinke). “We don’t want to see those areas opened up to industry.” But of course, they say that any national monument designations must also guarantee access to hunting and fishing.

The hunting and fishing community is especially concerned that if the Trump administration’s review rescinds or shrinks the boundaries of any national monuments, it will set a dangerous precedent. Currently U.S. presidents use the 1906 Antiquities Act to designate national monuments; it remains unclear whether this act gives them the power to undo such protections ordered by past presidents. Hunting and fishing organizations fear that if this administration does so it will open a door for future ones to do the same. “An attack on one monument is an attack on them all,” Land Tawney says.

Even though hunters and anglers make up a large voting bloc, it has not always translated to the policy they want to see. “The problem is that our community hasn’t been necessarily well represented by our elected leaders,” says Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the TRCP. “Everybody likes to pay lip service to [us].” The reason, he explains, is that the hunting and fishing community has not typically held politicians accountable when they vote against its interests. “Our community is to blame for it,” he says.

“I’d say [the community] has a lot of power, but it is [largely] untapped,” Tawney says. “We could be getting more done if people were more aggressive. But it’s a sensitive subject, how politically active you should be.”

Cornell thinks this is changing. “We have to be more political than we’ve been, or we’ll lose ground,” he says. “It used to be enough to buy a license and find a place a place to hunt, but now we’ve had to up our game.” Rasmussen agrees. “For so long, these groups just didn’t play in the policy arena,” he says. “[Now] sportsmen have a growing political influence.” He notes that eight years ago, Trout Unlimited didn’t have anybody in state legislatures — but in 2017 the organization had dedicated representatives in every western legislature, working directly with them. “That’s [now] typical across the board for sportsmen’s groups,” he says. TRCP says that people who hunt or fish also tend to turn out to vote more than the average American, making them a potentially more influential force in elections — for Republicans in particular.

Just last February Rep. Jason Chaffetz (a Republican from Utah) withdrew legislation to transfer millions of acres of federal land to state ownership after facing immense opposition to the move, including from the hunting and fishing community. In an Instagram post showing Chaffetz in the woods, dressed in camo and holding his dog, he wrote, “I’m a proud gun owner, hunter and love our public lands,” adding that “ groups I support and care about fear [the bill] sends the wrong message.” Chris Wood, president and CEO of Trout Unlimited, says his group has seen similar successes in states including Utah, Wyoming, and Nevada. “Our members were able to help convince legislators that [transferring public lands] was a bad idea,” he says.

When it comes to the national monuments, though, not all hunting and fishing groups have decided to enter the political fray. Ducks Unlimited has declined to take a stance. And not all hunters and fishers support national monuments; some believe the land could be conserved in a better way, without government involvement. “Sportsmen aren’t a monolith,” says John Freemuth, a professor of public policy at Boise State University, who specializes in public lands. “The number one thing that concerns sportsmen is access. Many of them are environmentalists, but some of them aren’t.”

This August Zinke sent Trump a report of his national monuments review. At first only a general summary of the report was made public, without Zinke’s specific recommendations for the president. But the report acknowledged that when the Interior Department invited public input on the review, the majority of the 2.8 million comments it received favored keeping existing monuments as they are.

Shortly afterward, a draft of Zinke’s detailed report to the president was leaked to the media. It revealed that the Interior Secretary had suggested cutting boundaries or reducing restrictions on seven of the land-based monuments and three of the marine monuments: Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in Utah; Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks and Rio Grande Del Norte in New Mexico; Oregon’s Cascade-Siskiyou; Nevada’s Gold Butte; Katahdin Woods and Waters in Maine; Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument; Pacific Remote Island Marine National Monument; and Rose Atoll Marine National Monument. Various hunting and fishing organizations expressed deep disappointment in Zinke’s recommendations.

But those recommendations are not final — the president will ultimately decide what happens to these monuments. Outdoor organizations do not know what to expect next, since Trump is notoriously unpredictable. But, says Chris Wood of Trout Unlimited, “it seems like so far they’re not paying attention to what we care about.” Just last month, Rep. Rob Bishop (a Republican from Utah) introduced a bill to overhaul the Antiquities Act, which would significantly limit the president’s power to designate national monuments. And last Friday, Trump reportedly told Sen. Orrin Hatch (also a Utah Republican) that he would shrink the boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument.

Whether conservatives in Congress and the White House realize it or not, these may turn out to be risky moves. Since many hunters and fishers count themselves as part of the Republican base and number in the tens of millions, “[they are] a huge voting bloc, and something that politicians and the administration need to pay attention to,” Tawney says. Wood puts it more bluntly: “We will ensure the voices of sportsmen and sportswomen are heard throughout,” he says. “They ignore us at their political peril.”

Susie Essman: Being a woman made me a funnier comic

Susie Essman on "Curb Your Enthusiasm" (Credit: HBO/John P. Johnson)

“It’s very, very different for women now,” comedian and actress Susie Essman told Salon’s Alli Joseph on “Salon Talks.”

Essman joined “Salon Talks” to talk about her role as sassy Susie Greene on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” currently in its ninth season. She also reflected on her career in comedy, which began with stand-up and has spanned nearly three decades, and the progress women have made in the industry.

For Essman, progress is all about respect. “What’s always interesting to me is how the young male comics treat women now so different than how they did in the ’80s, and I think it’s because they can’t deny us anymore,” Essman said. “They’ve seen too many funny women that they can’t deny us anymore.”

Essman has played the hilarious Susie Green in “Curb Your Enthusiasm” from the show’s beginning, but her comedy career is expansive. She’s starred in her own HBO comedy special, and appeared in numerous films and television shows, including “Late Night with Conan O’Brien,” “The View,” and “Crank Yankers.” Most recently, she costarred with John Travolta in the Disney animated film “Bolt” as the voice of Mittens the Cat.

According to Essman, in the ’80s it was “much easier for a mediocre guy than a mediocre woman.” But, she added, “who wants to be mediocre?”

Essman combated the discrimination by being so good she was undeniable. “You always have to work harder as a woman to get where you are; it’s just a fact,” Essman said. “It made me a better comic. It’s the silver lining.”

Watch the video above and catch the full “Salon Talks” conversation on Facebook to hear Essman talk about what it’s like to step into her role as the sarcastic and very inappropriate Susie on “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

All hail Cardi B, a true “Trap Cinderella”

Cardi B (Credit: Getty/Dia Dipasupi)

This is going to sound really safe, but I don’t care because it’s true: I’ve been on Team Cardi B from day one. I don’t mean the viral Instagram videos she hit the scene with or her “Love and Hip-Hop” fame, as I’ve never seen the show. But I signed up after I heard about her making the transition from stripping and reality TV to hip-hop, and have been hooked ever since.

Let me take it back to the beginning. I’m sitting in an otherwise empty coffee shop with an old friend I don’t really talk to anymore.

“Rap is trash, they give anybody a platform!” she said. “Like how could anyone take Cardi B serious at anything?”

Like a supervillain, she squeezed her paper cup until it crumbled in her palm. “I hate the internet!”

I tried to hold in my laugh but I couldn’t.

“Yo, who is Cardi B?” I asked. “And what she do to you?”

“You don’t know Cardi B?” she replied with an is-he-crazy smirk. “Really? She’s that yuck mouth THOT from ‘Love and Hip-Hop’! A disgrace to women all over! And now she has a song out! Trash! Pure trash!”

I asked if she heard the track and of course the answer was no, followed by something typical like I don’t have time for that, when really the people who say that have time for everything.

Gross generalizations like that are the reason our friendship had ended. Anyway, I have this great habit of doing my own research instead of listening to other people’s opinions, so I googled Cardi and found a video where she said, “F**king famous people isn’t in style anymore. Scammers, drug dealers and fat ni**as is what’s in! Duhhhhh.” Brilliant. In another clip, she said that she wouldn’t date an artist because they’re not as fun as credit card scammers.

I laughed until I choked a little, watched about 20 more Cardi clips and fell in love with the raunchy personality of the 25-year-old Bronx native. Her humor is raw, vulgar and completely delivered through truisms that anybody from any ‘hood in America can easily understand. If she gets tired of rap, a career in standup can definitely pop.

I went straight to iTunes and bought her single “Bodak Yellow.” I didn’t even sample it. I just wanted to support her because she was funny, familiar and — most importantly — real. We all know a Cardi — she’s that long-haired pretty girl from your middle school with the slick mouth who always lived two or three years above her peers; she’d trash you from time to time and you’d let it go as quickly as you got mad because she was that cool. Everyone loved her, even the people who hated. The only difference is that girl normally disappears after middle school, and Cardi is blowing up — her single shot into the top 10 of the Billboard chart shortly after it was released.

Some weeks passed and I caught up with my Cardi-hating homegirl at a local art show.

“Yo, I looked up Cardi B. She’s super funny,” I said. “And that song ‘Bodak Yellow’ is blowing up! Right?”

“That song is trash, and you are promoting that trash,” she said to me with that is-he-crazy smirk. “You changing, man. I don’t know what is wrong with you.”

We all left the exhibit and headed to a bar. I drove while she was fussing with her girlfriend in the back from the passenger seat. Every slur word was used, and then an awkward silence hit the car about four blocks away from our destination. “Y’all ever see ‘Pretty Woman’?” I asked.

Their argument stopped and they both slipped into a daze of Julia Roberts nostalgia. How beautiful she was in that film, her elegance, and how she took a rough situation and made it good. I’m not really old enough to remember its initial impact on culture; however, I do see Cardi as a real-life millennial “Pretty Woman.”

“So, if y’all can love the fictional prostitute who lands a millionaire,” I said, “What’s wrong with loving a real-life retired stripper who worked her way into having one of the hottest songs in the country?”

She told me that it’s not the same, got out and slammed my car door. I bought a couple of rounds when we got inside, and the DJ blasted “Bodak Yellow” two or three times during his set that night. The club ripped every time he mixed back to her line “Got a bag and fixed my teeth / hope you hoes know that ain’t cheap.”

I looked at my Cardi-hating homegirl and laughed every time.

Over the next few weeks, Cardi blew up — like Jay-Z and Beyoncé backstage at Made in America waiting to meet her-level blew up. Her face was everywhere, and she made history by being the first female rapper with no feature to be #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 19 years.

And then Cardi started popping up on shows like “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” and “The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon.” She’s performing at venues all over the country and lives on the feeds of all of my social media apps. Cardi was given the Spirit Award from the city of Detroit, and in true Cinderella fashion she received a chicken nugget-sized diamond engagement ring from her boyfriend Offset, of the popular rap group Migos (some other guys who are having an amazing year). Every celebrity started embracing her as the whole internet is collectively praising her success, and the naysayers — well, they don’t really exist anymore.

Even my Cardi-hating homegirl isn’t a Cardi hater anymore. She posted a thread on Twitter talking about how great Cardi is and how people who disrespect her are trash. Yes, she switched sides. I’m not sure if her change of heart came from reassessing Cardi’s single or just all of the mainstream validation, but she’s joined the club.

And why not? Why was it so hard for people to like Cardi B? She’s socially advanced, in my opinion, hilarious and a hard worker. What’s a better example of the American dream? A former stripper and reality TV personality turned into the number one musician in the country with the simple recipe of hard work and staying true to herself.

I’m not sure why anyone wouldn’t approve of Cardi initially, but the power of mainstream validation scares me. Why would we wait for big corporations to define hip-hop, especially when many of the genre’s most talented creators and trendsetters, like Cardi, come from the bottom? I guess it doesn’t matter now because Cardi has the streets and the industry — she just landed on the cover of Rolling Stone. But I hope we can all use her rise as an example of the power of loving where you’re from, regardless of what insiders or outsiders think. Cardi, we stand with you and are more than proud to call you our Trap Cinderella, our Bichelle Obama and the reigning queen of culture. May you forever ball out of control.

How hip-hop is trying to get you healthy

Jadakiss; Styles P (Credit: Getty Images/Salon)

On Castle Hill Avenue in the Bronx, a street filled with pizza shops, bodegas and nail salons, one store stands out: Juices For Life.

A chalkboard sign out front often teases wheatgrass shots, smoothies and fruit moss, sometimes with hip phrases such as “We got the juice now!”

Inside, a bar sits on top of an array of fresh fruit and vegetables: pineapple, kale, celery, cucumber, grapes, red and green apples, berries of all kinds. On the menu, the juice offerings are labeled based on your health concerns. There’s a option for acne, for allergies, for depression, for hypertension, for obesity, even for cancer.

But Juices For Life wasn’t started by a Whole Foods defector, or a gentrifier trying to turn a profit. Instead, it’s the brainchild of New York rap legends Styles P and Jadakiss.

“If you walk down the block in the ‘hood, it’s nearly impossible to find something healthy to put in your body. We were consuming whatever was made available to us,” Jadakiss says in a short film about the bar’s opening. “We didn’t have the knowledge or the opportunity that we do now, and that’s exactly what we’re trying to give to our community.”

Since Juices For Life arrived on Castle Hill in 2010, three more locations have opened up, one in the nearby Throggs Neck neighborhood of the Bronx, one a few miles north in Yonkers, where the rappers were raised, and, most recently, one in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. “Our juice bars are opened in the ‘hoods on purpose,” Jadakiss says in the video, “to educate our people on health awareness.”

While hip-hop can be stereotyped as glorifying heavy weed smoking, drinking and a general lack of self care, a clutch of rappers are emerging as leaders of a focused health movement. Given that health and health care disparities continue to be significant across racial lines, it’s an urgent one.

According to the CDC, the life expectancy for black people is four years less than that of their white counterparts. Moreover, black people have the highest death rate for all cancers, and “blacks in the 18 to 34 and 35 to 49 age groups were nearly twice as likely to die from heart disease, stroke and diabetes as whites,” CNN reported.

Maya Feller, a registered dietician and nutritionist, pins at least some of this to the reality that the economic community in which individuals live greatly determines their health on many levels. Given that the U.S. is still significantly segregated, with low-income areas often hosting tight black and brown communities, there are islands of people of color struggling with poor health across the country. But she told Salon this isn’t because of a lack of education or will. This is about access.

Feller describes a “food desert” in urban settings as any neighborhood where there is not “a good, viable grocery store, and what you have is bodegas, fast-food restaurants, chain restaurants.” She tells Salon “What I call those areas are ‘fast-food swamps,’ because it’s not that there’s no food, it’s just that there’s an abundance of fast food,” and not much else.

As rapper SwizZz told HipHopDX, “You see the lack of grocery stores in urban communities, and for people in some ‘hoods it’s easier to get access to guns than it is to get fruits or vegetables.”

“The truth of the matter is, when you step into these impoverished communities — you step into any ‘hood across America — it’s a food desert,” Quentin Vennie, Baltimore native and author of “Strong in the Broken Places: A Memoir of Addiction and Redemption through Wellness” tells Salon. “In my old neighborhood, there’s one grocery store,” Vennie says, “and you go into the produce section, and there are flies all over the place, the kale is limp, the celery is flimsy, nothing’s fresh.”

Vennie was diagnosed with anxiety and depression at 14. Years later, when he went on anxiety medication, he struggled with a two-year addiction that included surviving an overdose and two suicide attempts. Through meditation, yoga and nutrition, he transformed his body and his life.

Vennie says in the community he grew up in, there’s a “Chinese carryout, which is right next door to a pizza spot, which is across the street from a fish takeout, which is directly across the street from a liquor store, which is across the street from another liquor store, which is down the street from another one. We’re not talking about a few miles here, we’re talking three blocks.” Vennie adds, “People can’t say we don’t want to be healthy, when we don’t have that option.”

For Vennie, this is no accident. Black Lives Matter has resurfaced the language of state-sanctioned violence when speaking about what black people and communities endure at the hands of the system. For Vennie, this concept includes not only the immediacy of police killings, but also “slow deaths” caused by constricted health resources.

“In a city like Baltimore,” he says “one of the most dangerous cities in America — and even my community, the Park Heights community of West Baltimore — homicide was like the fifth or sixth leading cause of death.” He adds, “HIV, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer were the top four.”

Feller worries that if President Donald Trump fulfills his promise to undo the Affordable Care Act sometime during his tenure, it will disproportionally affect black communities. “In this country, because many black and brown people are low-income people, dismantling what little health care folks have is detrimental,” she tells Salon. “Now it goes from slow death to imminent death.”

With rappers already leaders in their communities in cultural, and sometimes financial, capacities, a crop of activated hip-hop artists are channeling their influence in an attempt to address this threat through multiple means.

Much of that has to do with individuals in the hip-hop community simply being purposefully open about their own health problems and highlighting their treatments and transformations. For instance, Rapper Gucci Mane kicked an addiction and dropped 75 pounds during a three-year prison stint in what Vogue described as “hip-hop’s biggest makeover in recent years.” He was released last year, never looking healthier or happier.

In 2016, rapper Kid Cudi announced via Facebook that he was checking himself into rehab for “depression and suicidal urges.” His social media post birthed the hashtag #YouGoodMan, which opened up space for people online to talk about mental health, race and masculinity.

In 2015, Jay-Z and Beyoncé said they were going vegan for 22 days. During an interview after his album “4:44″ dropped this year, the rapper talked openly about attending therapy to overcome generational trauma.

It’s a movement that’s become so pronounced and influential that a new documentary following several rappers who’ve pursued weight loss and wellness called “Feel Rich: Health Is the New Wealth” was released this spring. On top of the inspiring individual stories, the film stresses the importance of hip-hop in promoting health, particularly in low-income and black communities.