Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 229

November 25, 2017

“At Home with Amy Sedaris”: Celebrating not-so-good housekeeping

"At Home with Amy Sedaris" (Credit: TruTV)

Domestic performance pressure, be it explicit or implied, is a major source of holiday exhaustion. Some of you are familiar with this aspect of the holidays: the unstated push to deck the halls and bake, sew, knit, crochet and craft; the dream, however attainable, of creating a wintry fantasy in lights and glitter, of setting the perfect table, of presenting guests with a juicy roast that is browned just so.

If you’re feeling such pressure, Amy Sedaris is there for you. If not, then Amy Sedaris is really and truly there for you.

In the first season of the truTV series “At Home with Amy Sedaris,” Sedaris has taken a loving poke at various aspects of the domestic arts, lampooning everything from traditions surrounding grieving to frugality, nature and cooking for one. Her tips range from the utilitarian to the twisted, her calisthenics sessions are giddily raunchy, and her Craft Corner creations are simple enough for children to do — except, that is, for the dangerous ones.

“People who really make stuff and they’re good at it, they’ll get a kick out of it,” Sedaris told Salon in a recent interview, “but I don’t think it’s going to inspire those people on Etsy to get out there and want to make their own plush toy. I think they’re going to be like, ‘Yeah, maybe we should never try it. If she can’t do it, I can’t do it.’ Maybe my books would reach those people but I don’t think a TV show does.”

As we slide into a month of unreasonable light-and-garland displays and outrageous culinary complexity as seen on HGTV or Food Network, the holiday episode of “At Home” that airs Tuesday at 10:30 p.m. — the show’s regular timeslot — offers to be a surreal and ridiculous and ever so slightly numbing antidote. Just like every installment that has come before it.

Think of the holiday episode, and every half-hour before it, as Sedaris’ gift of goofy serenity at the onset of another hectic string of weeks.

(Then consider her wise way of thinking about gift-giving: “What a perfect way to show someone you care without having to spend time with them!”)

“At Home with Amy Sedaris” is part of the increasingly rare breed of cable show that has no other purpose than to display the weirdness of its creator in full bloom. Luckily enough, people are familiar enough with Sedaris’ schtick that a show based on her bizarre imagination and memories of domestic divas of her youth — specifically, Lawrence Welk and a North Carolina show called “At Home with Peggy Mann” — found purchase on basic cable.

For anyone nursing a love-loathing relationship with the housekeeping-perfection industry, “At Home with Amy Sedaris” is a balm and welcome amusement. “It’s more about the characters and their interaction and me having the show out of my home,” she explained. “It’s not so much about what I’m making or cooking.”

Thank goodness, since among the items she makes are flan fit for a hobo and an angel food cake stuffed with ice cream that, as demonstrated by the fictional Amy and her handsy ex-lover, played by Nick Kroll, look like a disaster out of Martha Stewart’s nightmares.

That’s just fine by Sedaris. “I like more naïve-looking things, folk art, things that look like a 10-year-old child made it,” she said, and I gravitate towards that kind of stuff more than the perfect Martha Stewart-type-looking stuff, which takes some skill.”

“And hats off to her,” Sedaris adds, “but it’s not what I’m drawn to.”

Viewers who are familiar with Sedaris know her as the voice of Princess Carolyn on “BoJack Horseman,” or her supporting role in “Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt,” or from her starring role in the cult classic “Strangers with Candy.” Before all that she was also one of David Letterman’s favorite occasional guests, someone whose zany sensibilities tickled him so much that he’d invite her on, you know, just because.

But Sedaris, like her satirist brother David, is a famous person who lives among the rest of us mere mortals out of practicality and who happens to find pleasure in the aesthetics of housekeeping as chronicled in the bizarrely color-saturated recipe tomes from her childhood in the ‘60s and ‘70s. She displayed this with gusto in her 2006 book “I Like You: Hospitality Under the Influence” and its 2010 follow-up “Simple Times: Crafts for Poor People.”

The difference between Sedaris’ books and her show is that “I Like You” and “Simple Times” had real recipes and directions meant to yield crafts that are actually useful. In contrast, the only serious endeavor of “At Home with Amy Sedaris” is its humor, which the host presents with a dusting of genteel irony and dollops of nostalgic visuals.

The set is a replica of her apartment kitchen, minus working appliances and plus lots of construction-paper decor. “It’s still my lifestyle and I’m still surrounded by everything that I love,” Sedaris said. “This show does have a little ’70s vibe to it, but that’s not on purpose. It just happens to be what I like from back then — all the avocado green and goldenrod.”

Episodes stick to a theme while welcoming guest stars such as Rachel Dratch, Chris Meloni and Michael Shannon; Sedaris’ “Strangers” co-star Stephen Colbert and Kroll get to fly their freak flags as themselves or various disturbing characters.

None steals the show from its star, who plays an assortment of caricatures in addition to a version of herself. At any given point she might share the screen with herself as a hobo with a foot fetish; herself as a bombastic Southern lady named Patty Hogg who has a superiority complex; or herself as Regional Wine Lady Ronnie Vino, who drops by to share a recipe for sangria and drop off a bag of her own version made in the toilet, prison style. Ever the charming guest, Ronnie exits while singing her signature tune: “It’s Friday night! I’m gonna get drunk, I’m gonna get laid, I’m gonna be late on . . . Monday!”

Although the show’s Amy promises tips on such useful life skills as “reattaching the tips of your fingers on the cheap,” the unspoken covenant with viewers — sane ones, anyway — is that nobody’s going to learn how to cook or craft much of anything here. A large part of the point Sedaris makes with “At Home,” besides reminding us of the normalcy of imperfection, is that most of us don’t have the time, space, or money — or even the appliances — to reach the standards of the Barefoot Contessa.

“I was just talking about Ina Garten, the Barefoot Contessa, as she would be like, ‘Now, we’re going to juice a lemon,’ and she would pull out this big thing to juice a lemon. That’s exactly why I can’t relate to these shows,” Sedaris said. “Who has counter space for that? Why can’t you just juice it yourself by sticking a fork in it and why do you need that big old gadget?”

In spite of this, Sedaris doesn’t intend “At Home” as pointed satire. Like the art of homekeeping itself, the show is mainly concerned with conveying a sense of comfort.

“It’s just nothing, it’s fluff,” she declares, going on to cite Welk’s penchant for unpredictable frivolity as a guide. “It’s like all these skills have to come into play and it just makes you smile. That’s what I’m hoping people will do when they watch the show. I just hope they have an ear-to-ear smile.”

How cult leader Charles Manson was able to manipulate his “family” to commit murder

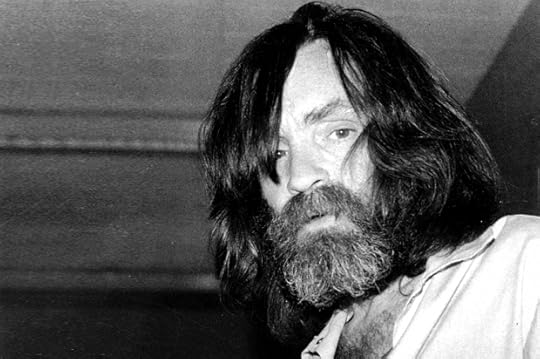

Charles Manson (Credit: AP)

Charles Manson, who died on November 19 aged 83, was a cult leader par excellence. Back in his heyday, he recruited a devoted set of followers to his “family”, some of whom went on to murder people for him and whose tragic story has inspired numerous books, films and TV programmes. But what did people see in Manson and how did he manage to manipulate and control people so successfully and with such terrible consequences?

It is said that “love is in the eye of the beholder” and there’s no better example of this than the love and devotion that intelligent and well-educated people have for cult leaders who portray themselves as the next messiah but who look to the rest of the world like deceitful and abusive sociopaths.

Of course people do not see an advert for an “abusive and murderous cult” or “how to end your life in trafficked drudgery” but instead are told about an inspired and charismatic leader whose vision and purpose can transform their lives for the better and the whole of humanity with it. So people go along to meet this extraordinary person full of hope and optimism – after all their friend or the persuasive man or woman who told them you all those great things about the guy can’t be totally wrong, surely?

This is what psychologists call optimism bias which indicates that we are wired to “look on the bright side” and in the case of people recruited into cults this is also because of what they have been promised and what they then hope and expect to find.

So Manson may have looked sinister to you or I – but we were not expecting a visionary messiah with a promised, powerful message and followers who look just like us. For those who were and choose to believe in this wonderful, life-affirming opportunity, the search for salvation in bondage to the cult leader had begun.

A messiah figure

The key to Manson’s control, as with all cult leaders, was to ensure that followers not only saw him as an all-powerful, messiah-like figure, but that followers see themselves as members of a superior elite that has the answer to the world’s problems – even if that means killing the rest of the world along the way. Manson persuaded his followers to commit murders to trigger “Helter Skelter” where there would be a “race war” which would elevate him to world leadership. He espoused a rambling, incoherent apocalyptic world view that was nevertheless completing captivating for his followers.

Over time the Manson-type cult leader becomes a dominant part of the follower’s identity and their self-esteem. The whole reason for their existence and survival is completely tied up with the leader and the cult. Manson became the core and central part of his followers’ lives – he provided a “family” and fulflled their basic needs. His “family members” acted to further that critical part of themselves that was bound up with him – and with terrible results.

Normal critical thinking and morals go out of the window. This explains why cult followers themselves can do terrible things or witness barbaric acts and do nothing to stop them. If you act against Manson you are acting against yourself and all that you’ve invested in him. After all there’s no going back, is there? This means there is no limit in practice – even if that means murder as in the case of some of the Manson cult members.

These terrible crimes were the ultimate act of loyalty and reinforcement of the cult identity for the followers – like suicide bombers this probably felt like the best thing they could have possibly done at the time. But the Manson followers were living in an altered state of consciousness and existence – aided also by drugs – and where the normal rules of society just didn’t apply in the cosy “family” that Manson had constructed.

The lesson of the Manson ‘family’

Many of the Manson followers went to prison for their crimes, and some felt tremendous guilt later about their actions. But what is really frightening is how it is all too easy to be duped and sucked into believing that your life is dependent on an amazing leader with such wonderful insights who in reality is a murderous psychopath. Followers forget who they really are, their other interests, family and friends and do terrible things for the cause and leader they love.

The lessons from the Manson “family” are a warning to us all: question everything, think critically and don’t believe that any single person has all the answers. Be wary of charisma and charm and people who are devoted to a messiah-like leader because while it is great to believe in big beautiful ideas it can also be the road to cult slavery and servitude.

Manson’s lasting legacy is hopefully that people will increasingly see through such cult leaders quicker and avoid them more easily than the followers who devoted their lives and murdered others to prove themselves as true devotees.

Manson’s lasting legacy is hopefully that people will increasingly see through such cult leaders quicker and avoid them more easily than the followers who devoted their lives and murdered others to prove themselves as true devotees.

I’m a liberal because I’m autistic

A portrait of the author. (Credit: Salon/Flora Thevoux)

To understand why I’m left-wing on economic issues, you first need to realize how devastating it is to be autistic in the modern workforce.

I have no idea what it was like for autistic people who tried to get and hold down jobs before the condition was diagnosed in the mid-20th century — although I imagine it wasn’t easy — but it is definitely hellish now. Given that I work at my dream job as a writer and am in the process of completing my Ph.D., I consider myself incredibly lucky today. But that wasn’t always the case.

When I was in high school, when a classmate heard me talk excessively and enthusiastically in response to a teacher’s question (a common problem for me in those days) he cuttingly observed, “Dude, you’ll never be able to hold down a job.” For the rest of my teenage years and into my early 20s, he wound up being proved right: I got fired from several of my early jobs (grocery store bagger, burger flipper, convenience store clerk, that sort of thing) for offenses ranging from struggling to make eye contact and talking too much, to offenses that wound up being categorized as “abrasive” and “weird.”

“One of the things we always tell employers, and I tell groups when I’m speaking to them, is that most individuals on the spectrum when they lose a job, they don’t lose it because of their performance on the job,” Marcia Scheiner, president and founder of Integrate (formerly Asperger Syndrome Training & Employment Partnership), told Salon. “They lose it because of social missteps at work.”

It is impossible to accurately convey how traumatizing — and yes, the word “traumatizing” is not only appropriate here, but necessary — this is for individuals in the autistic community.

When you try your hardest to hold down a job but are unable to do so due to factors beyond your control, the impact is profoundly demoralizing. When I spoke with other autistic friends and acquaintances for this article, all of them told stories about how they’ve grown terrified of being fired — some to a degree they admit is unhealthy and neurotic — because of all the previous occasions when something they said or did, but did not understand, caused them to lose a job.

Note that I didn’t say “most.” I said “all.”

Even worse, because our culture insists that being unable to hold down a job indicates a deeper character flaw, many autistic people develop self-loathing as a result of their experiences. I know autistic men and women who are brilliant and hard-working but constantly refer to themselves as “bums” or “losers” because society has told them that, well, their inability to hold down a job proves that those things are true about them. If they dare trying to dispel those misconceptions with the facts about their situation, they’re accused of coming up with excuses.

So how prevalent is this problem?

“Unfortunately in this space there is not a lot of good hard data,” Scheiner said. “There are universities and hiring programs where they are starting to collect the data, but frankly there has not been enough known programs and pools of known individuals on the spectrum in employment that anyone can really collect valid data.”

Scheiner added that the solution isn’t likely to come from the government.

“The biggest thing that we think makes it easier for individuals on the spectrum to retain their work is training their employers. It’s not something that the individual on the spectrum needs to do, it’s something the employer needs to do,” Scheiner told Salon.

Fortunately, there are already individuals trying to do exactly that. Within the last month there have been stories about a mother and her autistic son opening up a bakery to employ other people on the spectrum, or a start-up that creates tech jobs for individuals with autism. There are also large corporations like Microsoft, SAP, Walgreens and Freddie Mac that have made a point to try to hire individuals with autism.

These are all steps in the right direction, but they are nowhere near enough. And this brings me back to why I connect my decade-old experiences struggling as an autistic youth in the workplace with my larger belief in economic liberalism. In the end, we are only going to make life easier for autistic individuals in the workplace when we create a more compassionate, tolerant and inclusive atmosphere for everyone in the workplace.

When you hear about someone who is unemployed, or who struggles to hold down a job, check yourself before passing judgment. Dismissing those individuals as screw-ups or layabouts isn’t just cruel or intellectually lazy, it is also quite often incorrect. While libertarians and conservatives tend to blame the poor for their own plight, progressives recognize that factors beyond any one individual’s control can often impose terrible socioeconomic suffering on them.

Sometimes those factors are external, like the ups and downs of the business cycle or a company’s decision to impose layoffs. Others are internal, like neurological conditions that we are only beginning to understand.

Either way, because I was born autistic, I understand all too well that our current economic system is not the wisest or most just one that exists. You don’t have to experience discrimination as an autistic person to recognize that. You just need to be someone who the invisible hand has, at one point or another, decided could be treated as less than human.

Bigfoot, bullets and bud: My insane Humboldt County weed harvest

(Credit: Shutterstock)

“All aboard,” Brady snickered, as he opened the rear door of a horse trailer hitched to a narcoleptic mid-‘90s Suzuki Samurai. The trailer’s windows were boarded over with stained scraps of plywood. I climbed right in, along with 16 others who had trekked to this remote mountain farm in Humboldt County, California, to trim marijuana. Brady slammed the door shut and padlocked it from the outside. Inside was pitch black and filthy. I fell on my ass when we started winding down the road. The trailer creaked and swayed with every bend, threatening to come loose and tumble off the mountainside. It was my first day of work.

In my real life, I’m a filmmaker living in Los Angeles. I’d been lured to the farm with the promise of choice footage and cold hard cash. My friend Summer had been living up in Humboldt for the past few years trimming weed during harvest season and thought the scene would make a great subject for a documentary. I agreed. She ran the idea by the farm’s owners, who said if I came with her to work, they’d be open to me shooting some interviews. Growers are a notoriously insular and suspicious bunch, and they don’t take kindly to outsiders. I’d seen a few documentaries that touched on the subject but never one in which the director immersed herself in their world and portrayed it from the inside. This level of access was unprecedented and promised to be exciting.

I didn’t realize how insane this project would turn out to be.

Since 1996, growing medicinal marijuana has been legal in California under Proposition 215. The state is set to legalize the recreational use and cultivation of the plant in January of 2018, but it’s still illegal federally. Which means that at any point, the DEA can bust one of these pot farms and arrest everyone on it. “If the feds show up, just run into the woods,” Summer said nonchalantly. “But don’t worry, they won’t.”

Most Humboldt growers actually opposed legalization out of fear that it would completely decimate the county’s almost exclusively cash economy. With legalization came a whole slew of problems, starting with the permitting and licensing fees. Grows would be subject to taxation and government regulation, and growers would have a harder time paying trimmers under the table. Then there was the concern that the process would favor large industrial farms and push mom-and-pop operations out of business. The black market also kept marijuana prices high; when it became less dangerous to grow, more product would be available, and that would drive prices down.

The current legal gray area also means that banks won’t take marijuana money, so growers dig holes in the forest and bury their cash. Rumor was, this farm’s owners had around $250,000 stashed on their property. The average wholesale price for a pound of marijuana in California is around $2,000, and a medium-sized farm like this one can easily produce 400 pounds of weed in a season. All of that cash and all of that crop makes growers paranoid. They don’t want workers to be seen coming or going, so trimmers live in tents on the mountain for months at a time. Security is necessary — staff is well armed, and the property is gated and locked. Once I drove onto the land, I couldn’t leave without someone letting me out.

I’d met up with Summer a couple of days earlier at her place in Arcata, a quaint northern California coastal town known for Victorian architecture and marijuana. My new boyfriend Paul was with me. We’d been together for all of a month and a half, so I’d thought it was a great idea to bring him along. By the time I left trim camp, we’d spent half our relationship sharing a tent in the woods. Before we headed to the mountain, Summer took us shopping for the supplies we’d need: ultrasharp scissors made in Japan specifically for trimming weed (at least two pairs were necessary), small plastic perforated baskets to collect trimmed buds, aprons to protect our clothes.

As we left town, we passed clusters of gutter punks roaming the streets, some hitchhiking, some holding up signs saying things like “Looking for 420 Work.” These were “trimmigrants,” Humboldt speak for the seasonal workers who flood the area during the harvest hoping to land a trimming job. They came from all parts of the U.S. and the world, mostly in their twenties and broke. There was the potential to earn a decent amount of money in a short amount of time — some would make around $60,000 cash in a season, then spend the rest of the year traveling the world — but many would show up without knowing anyone, not realizing how difficult it would be to find a job with no connections. They’d run out of money and end up squatting in the town square, essentially homeless. Others would head to a supermarket parking lot in neighboring Garberville, a place growers cruised in their pickups, looking for extra labor. It was very dangerous to find work this way. “You never know who’s going to pick you up,” Summer warned. “There’s a reason why they call it Murder Mountain.” The area above Garberville had first earned this nickname back in the ‘80s after a string of serial killings, and a spate of recent deaths and disappearances kept it going strong.

Last year, there were 22 homicides in Humboldt County — the most since 1986 — and 348 adults reported missing, many of them trimmigrants, in a county of less than 150,000 people. It was especially dangerous for women. In recent years, there had been numerous accounts of sexual assault perpetrated against female trimmers by the growers who’d hired them.

But it was hard to imagine all of this violence as I drove along the bucolic winding stretch of the Redwood Highway towards the mountain farm. My mind was focused on what I wanted to accomplish as a filmmaker: to interview the owners and some of the workers, to shoot some b-roll and to put together a pitch tape for a feature length documentary.

And this is how I found myself riding in a windowless horse trailer in the middle of nowhere. After an excruciating ten minutes, Brady, the farm hand, let us out. The smell of dank weed filled the air. Massive stalks of harvested pot plants, the largest seven feet tall, lay piled on the ground, soaking up the sun. I’d never seen marijuana plants in person before, and it hadn’t even occurred to me that they could be this tall. It blew my mind. Even though I’d been a casual weed smoker for most of my life, and had my medical card, I thought about the origins of my weed about as much as I thought about the origins of the blueberries I bought at Trader Joe’s. Which is to say, I didn’t think about it at all.

We wouldn’t be trimming today, we’d be bucking — serious farm labor. In lieu of an orientation video, I learned by watching the others. Put on a pair of latex gloves, dip your fingers in coconut oil to counteract the sticky resin, snip the buds off the stalk with a pair of rusty scissors, pluck off the fan leaves, drop it in your tub. A full tub paid $20. I filled seven tubs in eight hours, less than most people. Another day with a different strain of weed, I only filled two.

After work, we gathered around the camp’s fire pit, waiting for Tyson, the meth-eyed farm manager, to bring dinner. Campfires were forbidden those first few days; the ground was too dry, the threat of brushfire eruption too strong. It was early October. The chill in the air would only get worse as the days got shorter. We took swigs from bottles of whiskey to keep warm.

My fellow “trimmigrants” were an eclectic bunch: Sally, the Midwestern masseuse who was sleeping with the owner’s brother; Darian, the Norwegian vegan who woke up daily before sunrise to do calisthenics; Tracee and Vance, the older alcoholic couple who once owned a pig farm in West Virginia; Rico, the shit-talking Colombian scuba instructor; Rob, the conspiracy theorist and Bigfoot enthusiast. We were deep in the heart of Bigfoot country here amongst the redwoods, and many were true believers.

Most outdoor grows in Humboldt operated like this farm, although some were a bit less rustic. They housed their trimmers in cabins with power and heat, instead of making them set up tents on the property. All were far removed from civilization — Summer had worked on one where she’d had to take a canoe to get there. Before this, I’d only slept outdoors twice in my life. Neither time prepared me for the extreme nature of this camp. There was no electricity. We did have a generator, but it was always running out of gas. The single toilet and shower were housed in a wooden shed with no insulation. To get hot water, the generator needed to be hooked up to the water heater. I could never quite get it right, so my showers were brutal. Food was provided for us from a fiercely American menu: burgers, hot dogs, chili. Darian was served a baked potato for every single meal. I’m vegetarian, but sometimes the cook forgot and I’d end up eating hamburger buns for dinner. Lunch was cold cuts and American cheese, delivered to the work site in a cooler. There was no refrigeration, so everything stayed in there for weeks until it became slimy. This didn’t stop people from eating it. I lost 15 pounds.

It was a ten-minute hike through the redwoods to the decrepit single-wide trailer that functioned as the trim room. Fluorescent lights, folding tables and chairs, no ventilation. The smell of weed worked its way into every pore, every fiber of clothing.

I sat next to Summer so I could watch her work. “You’re basically giving the bud a haircut,” she explained, her scissors furiously snipping away, tiny leaves flying off in all directions, as she rotated the bud in her hand. The pay was between $175 and $200 per pound of trimmed weed. Summer was really fast — she did between three and four pounds a day. I was lucky if I made two.

The trim boss, a short, round-faced woman named Aylen, inspected our work and made sure no one pocketed any weed. Every night, Tyson collected our trimmed buds and weighed them in private. We’d get paid in cash when we left the mountain for good, not a moment before. I had no way to know if I was being shafted. But even if I was, what could I do about it?

Sometime during my second week, I finally met the owners, Wanda and Rex, a married couple built from hardcore Humboldt farming stock. Wanda thought the idea of a documentary sounded “interesting.” She offered to come by the camp after work so we could discuss it further. She never showed. She’d do this a few more times over the next couple of weeks. None of the other trimmigrants agreed to be filmed, especially not without the owners’ permission, so I decided to work and wait until they all felt more comfortable with me.

One day bled into the next. Rise with the sun, work all day, whiskey and weed by the fire before bed. Repeat. The temperature dropped until it reached the point where it became necessary to choose between foregoing any semblance of hygiene or contracting pneumonia. I went with the former. The only place with heat was the trim room, where Rob would play back-to-back episodes of “Coast to Coast AM,” a radio show devoted to the paranormal, junk science and conspiracy theories, while we worked.

Sitting in a folding chair under screaming fluorescent lights trimming weed for 12 hours a day while listening to George Noory really starts to mess with your mind. Maybe that noise I’d heard really was Bigfoot tree-knocking. “Did you hear that gunshot last night?” Rico asked one morning. I hadn’t. He said he’d gone to investigate and saw someone running out of the camp towards the road. Aylen insisted the noise had been a car backfiring. I didn’t know who to believe.

When they found the mold, things really started to go south. “See this?” Aylen asked, holding up a nug flecked with tiny white dots. “These buds you guys trimmed are no good. You gotta cut the mold out.” She returned the bags we’d handed over the night before. The first day we did as she asked. Then Tyson showed up with a truckload of 30-gallon trash bags filled with weed we’d already trimmed. They wanted us to redo it all. For free.

According to the experienced trimmers, the mold had erupted because the weed hadn’t been dried or stored properly, which wasn’t our fault. They whispered that what we were doing amounted to slave labor. But no one spoke up. Day after day we trimmed that moldy weed.

The air was thick with bud rot and revolution. Tyson took to carrying his pistol in plain view, stuck in the back of his dad jeans. Rex got wind of a potential worker uprising and showed up to set us straight.

“My 12-year-old daughter thinks you’re all a bunch of babies,” he taunted. “Stop complaining. Get through the mold, then you’ll get the good stuff. Anyone got a problem with that?”

No one dared look him in the eye. People like Tracee and Vance couldn’t afford to complain. They’d banked on this money. They had to hope that the new crop would be healthier, the buds would be bigger, and the money would start flowing. There was no other option. I was lucky — I had a life I could go back to. When Wanda flaked on me again, I decided to cut my losses.

Tyson cashed me out in the morning. Five hideous weeks of work amounted to just under $4,200. Before my time on the mountain, I’d had a romantic idea of hippies living on the edge of the law, getting stoned every day, trimming weed and raking in cash. The harsh reality was that this was mind-numbing, back-breaking work, and trimmers had no recourse to fight back against unfair or dangerous employment practices. People who were slow like me could work twelve hours a day, seven days a week, and barely make more than minimum wage. It wasn’t worth it. I left Paul there — it turned out he was a trimming prodigy and wanted to take advantage of it. Aylen unlocked the gate and I hit the road, driving back through the fog and the redwoods towards Highway One. I’ll never look at weed the same way again.

All names and some identifying personal details have been changed.

November 24, 2017

Don’t be fooled by these 12 foods with really tricky names

(Credit: AP)

“What’s in a name?” Shakespeare once asked. Well, everything. Food-wise, when it comes to names, the particular label or nickname an ingredient or dish carries can mean the difference between enjoying your meal or being repulsed by testicles when you really wanted seafood. Naming mistakes can also lead you to miss out on the treats of the world, like Russia’s herring in furs (?!).

When it comes to the following foods, the names just don’t suit the edible item they’re describing. Read on so you won’t be misled the next time you look at a menu.

1. Rocky Mountain Oysters

These rustic-sounding fruits de mer may appeal to the Western-loving diner, but don’t be fooled by this dish’s regional appeal. Not bivalves or seafood in the least, Rocky Mountain Oysters (also called prairie oysters) are the cooked testicles of bulls, sheep and other animals, with, well, meatballs.

Rocky Mountain Oysters made with bison testicles, served at the Fort in Morrison, Colorado. (image: Wally Gobetz/Flickr)

Typically served deep-fried, this dish is indeed more popular in land-locked regions, where the thought of swallowing an entire piece of seafood raw may inspire some gagging.

2. Herring in Furs

This traditional Russian dish sounds … fuzzy? “No one knows how it originally got this name, but herring in furs — also known as herring under a fur coat — was most likely some kind of culinary joke made over 100 years ago,” says Ilya Denisenko, the chef at Teremok in the United States. (The chain has more than 300 locations in Russia.)

Herring in furs, also known as dressed herring, is a traditional dish served at Christmas and New Year celebrations in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and other countries of the former USSR. (image: Paul Frankenstein/Flickr)

The name refers to a salad made with diced pickled herring covered with layers of grated vegetables, like potatoes, carrots, beetroots and chopped onions. It’s comparable to whitefish salad or egg salad, Denisenko says of the fur-free dish. “The vegetables add a nice textural contrast to the herring.”

3. Sweetbreads

One of the most misleading culinary names on menus today, sweetbreads are neither sweet nor bread. Instead, sweetbreads are made from the pancreas and thymus glands of animals, usually lamb or calf.

Country-fried sweetbreads served with a honey-mustard cucumber salad and hot sauce. (image: Lucas Richarz/Flickr)

These tender nuggets of meat are often served fried and savory, not sweet, and are served at Michelin-starred restaurants around the world.

4. Spotted Dick

Though it may sound more like an STI symptom than a dessert, spotted dick is a traditional English cake made with mutton fat and raisins or dried fruit for the spots, and rolled into a circular shape.

Spotted dick was first mentioned in Alexis Soyer’s The Modern Housewife or Ménagère, published in 1849. (image: SarahPresleey/Flickr)

5. Toad in the Hole

While the name of this breakfast dish may evoke images of an adorable toad peeking out of a lily pad, it is completely amphibian-free. Toad in the hole is made in a variety of forms; the English places sausage links in Yorkshire pudding, while Americans fry an egg in a piece of toast with the center cut out.

A cooked toad-in-the-hole in a baking dish. (image: Robert Gilbert/Wikipedia)

6. Blood Oranges

These gorgeous ruby-hued oranges may be the gem of the citrus family, but blood? Pass. Scarlet oranges, crimson oranges or vermilion oranges may be more appetizing names for this sweet and visually appealing fruit.

Blood oranges. (image: Jessie Pearl/Flickr)

The dark red color of blood oranges comes from anthocyanins, a type of antioxidant pigment common to many flowers and foods, like blueberries, black rice and purple cauliflower.

7. Grapefruit

We already have grapes. We already have fruit. If anything should be called a grapefruit, it should be actual grapes. If oranges get to be named by their color, why can’t grapefruits be called yellows or pinks? Or tart oranges?

The grapefruit started as a hybrid of the Jamaican sweet orange and the Indonesian pomelo. (image: liz west/Flickr)

Its name, etymologists suggest, comes from the fact that grapefruits grow in clusters, like grapes on a vine.

8. Chicken Fingers

Cows are beef, pigs are pork and sheep are mutton, but there is no euphemism for chicken flesh. Some perverse cook decided to let us delude ourselves even further into eating parts of a chicken it doesn’t even have.

Chicken fingers are made from the pectoralis minor muscles of a chicken. (image: raymondtan85/Flickr)

Chicken talons or chicken feet may be a more accurate way to describe chicken fingers. Chicken tenders, on the other hand, refer to a piece of the chicken breast that is indeed called a tender.

9. Submarine Sandwich

There’s probably no worse food to eat underwater than a sandwich loaded with meats and mayo and who knows what else, because a sub sandwich can refer to pretty much anything slapped between two slices of bread. Even a foot-long turkey provolone on a baguette does not look like an actual submarine.

Submarine sandwiches are also known as subs, hoagies, heros, grinders, spuckies,po’ boys, and wedges. (image:jeffreyw/Flickr)

10. Ants on a Log

This nickname for celery sticks filled with cream cheese or peanut butter and often topped with raisins or other crunchy snacks isn’t super appealing, nor is it helpfully descriptive. Ants on a log has no standard preparation, nor does the dish involve ants or logs. Unless you’re an upscale New York chef, that is. Alex Stupak, at Manhattan’s Empellón, recently debuted an “ants on a log” rendition that indeed uses the protein of the future: Ants.

Ants on a log served in a bento box. (image: Bunches and Bits {Karina}/Flickr)

11. Head Cheese

Not in any way a dairy product, this charcuterie item, often found chilled in the deli case, is indeed made from boars’ (or pigs’) heads. A sustainable way to practice snout-to-tail eating, head cheese uses the entire pig’s head, cooking it in a stock pot with vegetables and aromatics in order to gelatinize and form the loaf that will later become a sandwich ingredient.

Head cheese, also known as brawn, originated in Europe. Above, commercially sold Dutch preskop (a type of head cheese) as a cold cut on bread. (image: Takeaway/Wikipedia)

12. Duck Sauce

Unlike oyster sauce, this ingredient typical to American Chinese restaurants does not have any duck in it. In fact, the jelly-like, sweet orange sauce is completely vegetarian. Originally served alongside fried duck, the sticky condiment gets its name from its ideal protein pairing, rather than how it’s made, and is often served as a sugary complement to egg rolls, wonton strips or other fried foods.

Packets of duck sauce commonly accompany Chinese takeout meals. (image: Plastic klinik/Wikipedia)

Backlash against “mixed” foods led to the demise of a one-time American staple

(Credit: AP Photo/Matthew Mead)

At the end of “Over the River and Through the Wood” – Lydia Maria Child’s classic Thanksgiving poem – the narrator finally gets to his grandfather’s house for Thanksgiving dinner and settles down to eat.

“Hurrah for the fun!” the small boy exclaims. “Is the pudding done? Hurrah for the pumpkin pie!”

Pumpkin pie sounds familiar, but pudding? It seems like an odd choice to headline a description of a Thanksgiving dinner. Why was pudding the first dish on the boy’s mind, and not turkey or stuffing?

When Americans today think about pudding, most of us think of a sweet dessert, heavy on milk and eggs: rice pudding, bread pudding, chocolate pudding. Or we might associate it with Jell-O pudding mixes (When I was a child in the 1980s, I loved making pudding by shaking Jell-O instant pudding powder with milk in a plastic jug).

For the most part, though, Americans today don’t think much about pudding at all. It’s become a small and rather forgettable subcategory.

That’s a dramatic change from the mid-19th century, the period when Child wrote “Over the River and Through the Wood” and when Thanksgiving became a national holiday under President Lincoln. Back then, virtually every American cookbook had a chapter devoted to puddings (sometimes two or three).

Pudding was important in Child’s poem because, when she wrote it, pudding was such an important part of American cuisine.

From small budgets to banquets

It’s not clear what kind of pudding Lydia Maria Child had in mind for her Thanksgiving poem because it was a remarkably elastic category. Pudding was such an umbrella term, in fact, it can be hard to define it at all.

Americans ate dessert puddings we would recognize today. But they also ate main course puddings like steak and kidney pudding, pigeon pudding or mutton pudding, where stewed meats were often surrounded by a flour or potato crust. Other puddings had no crust at all. Some, like Yorkshire pudding, were a kind of cooked batter. There were also green bean puddings, carrot puddings and dozens of other vegetable varieties. Puddings could be baked or steamed or boiled in a floured cloth.

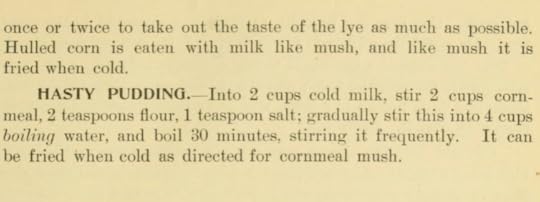

Then there were other dishes called puddings that didn’t bear any resemblance whatsoever to what we mean by that word today. For example, apple pudding could be nothing more than a baked apple stuffed with leftover rice. Hasty pudding was essentially cornmeal mush.

A recipe for hasty pudding from ‘Smiley’s Cook Book and Universal Household Guide’ (1895).

Library of Congress

Puddings were also hard to define because they were consumed in so many different ways. They could be sumptuous dishes, dense with suet and eggs, studded with candied fruits and drenched in brandy. Or they could be rich, meaty stews encased in golden pastry. In these forms, puddings appeared on banquet tables and as the centerpieces of feasts.

But puddings could also be much humbler. Cooks with small budgets valued them because, like soups, puddings could be made of almost anything and could accommodate all kinds of kitchen scraps. They were especially useful as vehicles for stale bread and leftover starches, and 19th-century Americans ate a wide variety made not just with bread and rice but with cornmeal, oatmeal, crackers and potatoes. Recipes with names like “poor man’s pudding,” “poverty pudding” and “economical pudding” reflect pudding’s role as a cheap, filling meal.

Food ‘experts’ exert their influence

So what happened to pudding? Why did this broad culinary category, a defining part of American cuisine for more than a century, largely disappear?

One reason was food reform. By the early 20th century, new knowledge about nutrition science, combined with an obsessive (but misinformed) interest in digestion, fueled widespread “expert” condemnation of dishes featuring a range of ingredients mixed together. This was due, in large part, to xenophobia; by then, many white Americans had come to associate mixed foods with immigrants.

Instead, reformers insisted with great confidence (but scant evidence) that it was healthier to eat simple foods with few ingredients: meals where meats and plain vegetables were clearly separated. People started to view savory puddings as both unhealthy and old-fashioned.

The unique prevalence and zeal of American food reformers in the early 20th century helps to explain why so many puddings disappeared in the United States, while they continue to be an important part of British cuisine.

By the mid-20th century, claims about the digestive dangers of mixed foods had been debunked. But a new kind of dish had since emerged – the casserole – which largely usurped the role formerly played by puddings. An elastic category in their own right, casseroles could also be made from almost anything and could accommodate all sorts of odds and ends. There were hamburger casseroles, green bean casseroles and potato casseroles.

At the same time, the food industry had reimagined pudding as a cloyingly sweet convenience food. Puddings made from supermarket mixes of modified food starch and artificial flavors became the only kind many Americans ever ate.

The classic versions haven’t completely disappeared, however. On Thanksgiving, Americans are still more likely to eat 19th-century-style puddings than at any other time of the year. On some American tables, Indian pudding, sweet potato pudding or corn pudding make an annual appearance. Thanksgiving dinner isn’t the time capsule some people imagine, and most Thanksgiving menus today have hardly anything in common with the 17th-century Plymouth Colony meal they commemorate. But there are some culinary echoes from the 19th century, when the American national holiday officially began.

Why this House tax scheme is for idiots

Paul Ryan (Credit: AP/J. Scott Applewhite)

The House tax bill is an all-out attack on the future prosperity of America, not that any of the major news organizations are telling you that in plain English. Lost in the dense bureaucratic language of modern news reports is the simple fact that the House bill takes from striving students so that the already rich and major corporations can have more.

This bill is a long-term disaster in terms of what economists call opportunity costs. That term refers to a benefit that a person could have received, but gave up, to take another course of action. This tax bill gives up the future wealth from investing in brainpower in favor of permanent tax cuts for the already rich and corporations.

This tax bill should be called the Intellectual Destruction Initiative Outrageous Tax Savings Act, a.k.a. the IDIOTS Tax Act of 2017.

Are we idiots?

What we need is more investment in education and, especially, education of the most serious and scholarly students. I have a name for what we need — the Intellectual Quality General Education National Investment University Scholarship Act or IQ GENIUS Act.

What will we tell our Congress, if anything, about this tax bill and the one being written in the Senate? Hopefully, it’s that we are not idiots and we want to develop more genius minds.

The House bill would eliminate a 2015 law that lets teachers who itemize deduct some of the money they spend on school supplies and materials not provided by their employers. In 2014, almost four million teachers deducted an average $254 each, IRS Table 1.4 shows. Nearly all of the deductions were taken by teachers whose tax returns, which can cover two people if married, had a total income of less than $100,000.

The IDIOTS Act also ends tax-free education benefits for the children of long-term college employees. The House GOP bill would eliminate Internal Revenue Code Section 117(d), which allows these benefits.

“Fifty percent of employees receiving tuition reductions for themselves or family members earned $50,000 or less, and 78 percent earned $75,000 or less,” according to the College and University Professional Association of Human Resources.

In simple terms, here is the bill’s message to the poorly educated person who works in the college cafeteria so that their child may attend college: “Tell your kids plan on a career in the cafeteria.”

Even worse is the plan to eliminate subsection (5), which allows “a graduate student at an educational organization … who is engaged in teaching or research activities for such organization” to get tuition waivers and stipends tax-free.

Taxpayer money now invested in developing knowledge would be shifted to giving massive tax breaks to heirs of the already rich and to the 3,000 corporations (out of 6 million) that own more than 80% of all the business assets in America.

And all so that couples with one family jet can afford, his-and-her private jets, like gambling mogul Sheldon and his wife Miriam with their twin personal Boeing 747s, as I revealed in my book “The Fine Print.” With their tax savings, the Adelsons would be able to upgrade to personal Airbus A-380s, those double-decker jetliners are built in France.

The most valuable asset in America is not factories. It is not formulas for making drugs or the algorithms that make the Internet work. Our most valuable asset is the gray matter between the ears of young people. A mind is a terrible thing to waste, but a wonderful thing to invest in, says an old slogan from the United Negro College Fund. Congress just doesn’t get it.

And the return on that investment rebounds not just to the individual, but to America and the world. My proposed IQ GENIUS Act should be thought of as the 21st Century G.I. Bill for all who will study, study, study.

We should be investing more in young minds, from birth through the highest level of education that serious students desire, not less. That is what China and other countries with an eye to tomorrow are doing, while our Congress looks at today and yesterday.

And the way to recoup that investment is through taxes on the higher incomes of those with advanced educations. Some will make little, many much better than average incomes and a few will become as rich as the Adelsons — and by taxing their fortunes society gets repaid for its investment while at the same time growing ever more prosperous.

When the American education system was developed in the late 19th century it focused on reading, writing and basic arithmetic. It was designed to produce workers for the industrial era — in good measure compliant drones who would do as they were told. It was also cheap, especially when most teachers were women because other job opportunities for women were few and the pay was miserly.

But the economy of today and tomorrow depends on a host of sophisticated skills — creativity, thinking outside the box and critical judgment — that were not so valuable in the Industrial Age. That costs more, but it also produces bigger rewards.

Only by rigorously developing critical thinking skills, a deep understanding of mathematics and statistics and recognizing the nature of science can America continue to prosper. Intense education is the fundamental building block of America’s economic future. Keep in mind that arguably the most successful investment taxpayers ever made, the G.I. Bill, helped produce the enormous increase in wealth today compared to 1940. Indeed, we would have more wealth had more GIs been able to take advantage of the bill, especially African American GIs and women who were clearly discriminated against in its implementation.

Should I get special treatment because I stutter?

(Credit: Getty/Sean_Warren)

I sat on the bathroom floor, dizzy and nauseated, picturing the stage where I would give a reading the next day.

Months ago, in a more optimistic moment, I had agreed to perform in a public reading event for my graduate writing program. The reading was to take place in a local theatre where I had seen plays performed. By accepting the invitation, I was required to read my creative work while standing alone on a stage normally filled with confident, professional actors.

But I was no actor — not even close.

I scooted forward on the floor and circled the toilet, fearful I might lose my lunch. While the nausea hit, I grew worried about my heart rate. It had a wild rhythm, more frantic than my fastest pace on the treadmill. Without meaning to, I pictured the stage again: the back wall lined in dark curtains, a spotlight over the podium, and then — me. Lost in the daydream, I imagined myself standing in front of an audience, then leaning into the microphone, suddenly unable to say a word.

This might seem like an exaggerated nightmare, a scenario of embarrassment lifted from a teen movie. But the reality of my situation made my apprehension genuine: I have a speech impediment and have since childhood. I stutter.

At 24, I had already experienced at least a dozen moments of public agony: public readings I had suffered through, the strain of the stutter making my neck red with shame, along with classroom presentations that turned into 45-minute stuttering displays, content muddled by my repetitions (r-r-r-repetitions) and prolongations (pppppprolongations). Still, there was an even worse way for the stutter to manifest: the dreaded vocal block, an impenetrable wall that prevented any sound from escaping. Blocks found their way into my speech with no warning, and not only during public speaking — they could strike while I ordered at a restaurant or made a phone call, too. Blocks could last anywhere from seconds to whole minutes, during which I would cast my eyes downward and try to ignore the people I was trying to communicate with as they shuffled awkwardly, waiting for me to finally begin speaking again.

There was a knock on the bathroom door. One of my roommates entered with a sympathetic frown and a large glass of water. At first I tried blaming my upset stomach on a meal of bad tacos. But the truth eventually emerged.

“I-I-I-I-I-I mmmmmight be . . . a-a-anxious about tomorrow’s rrrreading,” I admitted.

My roommate leaned into the door frame. “Have you considered not going?” she suggested gently, while I took long gulps of water. “Or maybe they could accommodate you somehow . . . have someone else read for you?”

I shook my head forcefully. My roommate was well-intentioned — logical, even. But I had decided long ago to refuse these sorts of accommodations. I had spent most of my life seeking fluency, before finally accepting that my stutter was to be a lifelong condition. If there was no cure, then all I had was my dignity.

“I’ve nnnnnever asked for ssssspecial treatment before,” I said with pride.

That much was true.Though only 1 percent of the American population has a stutter, I had met others who shared in my impediment, and most accepted accommodations for their disability without a second thought. There was the woman who refused to make phone calls and completed all of her errands online; the guy who had been assigned an aid in grades K-12, a literal mouthpiece following him from class to class. I sympathized with their plight, obviously, but their stories made me feel pretty smug, too. On some level, I felt more dignified than they, because I had never asked for or received special treatment because of my stutter.

My roommate left and closed the door behind her, but her words echoed in my mind. Maybe I had approached this all wrong. I had crafted my “no assistance needed” philosophy a decade ago, forcing myself to appear in control and unbothered, even if I was feeling anxious and depressed — which I often was. I had struggled silently with my disability and insecurities without acknowledging there might be another way.

Sitting on the bathroom floor, stomach turning, heart racing, I finally allowed myself to consider the previously unthinkable. Should I receive special treatment because I stutter?

My epiphany was accompanied by a series of seemingly unconnected memories: me transporting a heavy box, helping my mom use her bad knee; walking into a courthouse and noticing the ramp entrances and Braille signs; seeing my sister post a photo of frosted sugar cookies and asking Facebook friends — are these safe for people with peanut allergies?

Accommodations were being made every day, all around me, and no one was denouncing them or implying they’re a nuisance.

At the same time, no one was applauding my stubborn belief in embracing unnecessary stress, either — especially those closest to me, who realized how distressing my speech disorder can be.

I lifted myself from the bathroom floor. I grabbed my notebook, and — like any decent graduate student — developed a list of pros and cons.

I could go to the reading and stutter mildly. That was a possibility.

I could go to the reading and stutter violently, flush deeply with shame and cry the whole drive home.

If that happens, I thought, it might take me a while to recover.

I thought unexpectedly of a close friend who loves doing laundry. I would watch in amusement as she loaded her washer with detergents and softeners, sprinkling in scented beads, then tumbling the clothes on low-heat or hanging them to dry. She folded them delicately, tucking them neatly into drawers. If she can put that much care into her laundry, I thought, shouldn’t I put that much care into myself?

The next day, I wrote an email and recused myself from the reading, explaining the situation and my newfound awareness for self-care. Instead of putting my stutter on display, I treated myself to hot tea and a good book and enjoyed the solitude. I could have asked someone to read on my behalf, and considered doing so in the future. But for a person who stutters, even social interactions with friends can be taxing. My jaw was sore from speaking all week. My temples throbbed from the strain. I needed to be nonverbal for a while and allow myself time to recharge. It was early October, and though the leaves hadn’t begun to fall, a feeling of renewed clarity hung in the air.

That was one year ago. The changes in me have been subtle. I still consider myself a poised and self-sufficient person. I don’t need anyone finishing my sentences or speaking for me. I’m more than willing to self-advocate and educate others.

But now, if I’m asked to speak or read publicly, or make an important phone call, or meet a new person, and my stutter feels particularly debilitating that day, I feel justified in suggesting an alternative choice — or even just saying no.

The biggest threats to the stability of the world economy — and Google is one

(Credit: AP/Marcio Jose Sanchez)

In the early 1990s, transnational corporations (TNCs) in the agriculture, services, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing sectors each got agreements as part of the WTO to lock in rights for those companies to participate in markets under favorable conditions, while limiting the ability of governments to regulate and shape their economies. The topics corresponded to the corporate agenda at the time.

Today, the biggest corporations are also seeking to lock in rights and handcuff public interest regulation through trade agreements, including the WTO. But today, the five biggest corporations are all from one sector: technology; and are all from one country: the United States. Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft, with support from other companies and the governments of Japan, Canada, and the EU, are seeking to rewrite the rules of the digital economy of the future by obtaining within the WTO a mandate to negotiate binding rules under the guise of “e-commerce.”

However, the rules they are seeking go far beyond what most of us think of as “e-commerce.” Their top agenda is to ensure free ― for them ― access to the world’s most valuable resource ― the new oil, which is data. They want to be able to capture the billions of data points that we as digitally-connected humans produce on a daily basis, transfer the data wherever they want, and store them on servers in the United States. This would endanger privacy and data protections around the world, given the lack of legal protections on data in the US.

Then they can process data into intelligence, which can be packaged and sold to third parties for large profits, akin to monopoly rents. It is also the raw material for artificial intelligence, which is based on the massive accumulation of data in order to “train” algorithms to make decisions. In the economy of the future, whoever owns the data will dominate the market. These companies are already being widely criticized for their monopolistic and oligopolistic behaviors, which would be consolidated under these proposals.

Think about Google, which has become the largest collector of advertising revenue thanks to its ability to analyze and repackage our data. And think about Uber: it is the biggest transportation company in the world, yet it does not own cars and it does not employ drivers. Its main asset is the massive amount of data it has on how people move around cities. And with that “first mover” advantage, and with its army of lawyers and its massive scale, it can outcompete or simply buy up competitors around the world. The disruption Uber has caused in the transportation sector will shortly be seen in just about every sector you can imagine. The implications for jobs and workers are difficult to overestimate.

Another key rule these corporations are seeking would allow digital services corporations to operate and profit within a country without having to maintain any type of physical or legal presence. But if a financial services firm goes bankrupt, how can depositors seek redress? If a worker (or contractor) for the company’s rights are violated, or a consumer is defrauded, how can they get justice? And if the company does not have a domestic presence, how can it be properly taxed, so that it is on a level playing field with domestic businesses? Most countries require foreign services suppliers to maintain a commercial, physical presence in the country to operate for just these reasons; but Big Tech just sees it as a barrier to trade (and unaccountable profit). Public interest regulations would be seriously undermined.

But that’s not all. Big Tech also does not want to be required to benefit the local economies in which they profit. There are a series of policies that most countries employ to ensure that the local economy benefits from the presence of TNCs: requiring technology transfer, so they can grow their own startups; requiring local inputs, to help boost local businesses; and requiring the hiring of local people, to promote employment. But although every developed country used these strategies in order to develop, they seek to “kick the ladder away” so that developing countries cannot do the same, exacerbating inequality between countries.

The business model of many of these companies is predicated on three strategies with serious negative social impacts: deregulation; increasing precarification of work; and tax optimization, which most would consider akin to evasion of taxes. All of these downward trends would be accelerated and locked in were the proposed rules on “e-commerce” to be agreed in the WTO.

Since proponents of “e-commerce” rules in the WTO first tabled proposals last year, they have sought to convert an existing mandate to “discuss” e-commerce into a mandate to “negotiate binding rules” on e-commerce in the WTO. They have justified their proposals on the basis that e-commerce will promote development and benefit micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) ― as if promoting e-commerce and having binding rules written by TNCs are the same thing. But developing countries have focused their demands on increasing infrastructure, access to finance, closing the digital divide (obtaining affordable access), increasing regulatory capacity, and other concerns that will not be addressed by new rules on e-commerce in the WTO.

Meanwhile, MSMEs are able to participate in e-commerce now; but they are less likely to reap the benefits of scale, historic subsidies, strong state-sponsored infrastructure, tax avoidance strategies, and a system of trade rules written for them and by their lawyers if e-commerce rules in the WTO were to be adopted. What MSMEs need are platforms to facilitate customs clearance and international payments, but this is not what has been proposed in the WTO.

At this point, proponents have scaled back their ambitions due to massive resistance from the African bloc and some Asian and Latin American members. Now they are proposing more seemingly technical issues, such as e-payments, e-signatures, and spam. But these issues actually belong in other fora, such as the UN Conference on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) or the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) where legal and technical experts rather than only commercial interests were long ago able to help governments establish better rules.

Perhaps as a Plan B, proponents are claiming that “technological neutrality” already exists in the WTO. This would mean that if a country “committed” financial services in the WTO ― meaning that it agreed to have financial services subject to rules limiting regulation in that sector ― then cross-border online banking ― with all of the potential cybersecurity threats of hacking, or unstable financial flows wreaking havoc on local banking systems ― would already be committed. But this is a preposterous idea, and WTO members have not agreed to it, despite the intent of some countries that it is an accepted principle.

Proponents are also pushing to renew a waiver on tariffs on electronically delivered products, but there is no economic rationale as to why digitally traded products should not have to contribute to the national tax base while those that are traditionally traded usually do. But Big Tech may actually obtain this waiver, since it is often “traded” for a waiver that helps stabilize the generic pharmaceuticals market in developing countries, which helps guarantee access to life-saving medicines for millions of people.

The outcome in Buenos Aires will depend on strong resistance by developing country members to this new corporate Big Tech agenda. They should be aided by a strong civil society resistance to further imposition of procorporate rules that encroach on our daily lives.

Deborah James, djames@cepr.net, facilitates the campaign on the WTO for the Our World Is Not for Sale network.Tra

The Museum of the Bible is connected to a right-wing agenda

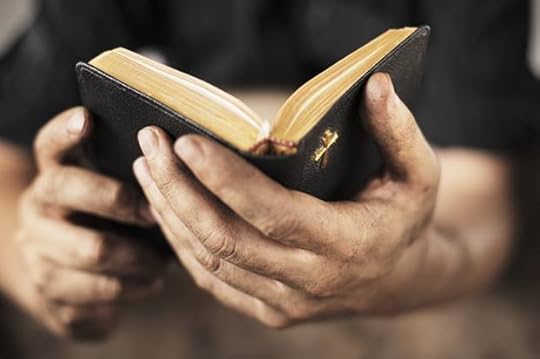

(Credit: Stocksnapper via Shutterstock)

Visitors to Washington, D.C. will now be able to add the Museum of the Bible to their sightseeing to-do lists. The museum, which cost $500 million to build and opens Friday, proclaims its purpose is, “to invite all people to engage with the history, narrative and impact of the Bible.” However, the Museum of the Bible and its founder Steve Green have been entangled in politics, making the high-tech, 430,000-foot space more controversial than it may appear. It’s all part of a larger pattern of the mixing of politics and religion in spaces that are billed as being for entertainment or education.

In an interview with Philanthropy Roundtable, Green said the museum is “not evangelical. It’s more informative.” However, Green, who is the CEO of Hobby Lobby, footed the bill for the museum and is the chairman of the museum’s board. The Green family provided artifacts—while Hobby Lobby has faced legal action over the smuggling of artifacts. The museum’s other controversial board members include Gregory S. Baylor, who works at Alliance Defending Freedom, a designated hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

In advance of the Friday opening, a fundraising gala will be held at the Trump hotel on Thursday. Some employees told the Washington Post that they were uncomfortable with the choice of venue, though Linda Koldenhoven, the director of Women’s Initiatives and Networking for the museum, told the Post, “We wanted it to be beautiful, and [the Trump hotel event space] is beautiful, and available.”

The Museum of the Bible will also be home to research and a Bible curriculum. As Business Insider reported, however, a previous attempt to house this curriculum in Oklahoma schools was “withdrawn following complaints the lessons weren’t neutral.” Steve Green insisted to Politico that while “his family openly supports evangelical outreach programs and more overtly evangelical-themed Bible attractions,” the museum is “a separate endeavor.” Yet D.C.’s new Museum of the Bible is part of a larger landscape of highly politicized evangelical museums across the United States. Here are three other such institutions:

1. Creation Museum: Located in Kentucky, the Creation Museum is operated by Answers in Genesis, which claims to “seek to expose the bankruptcy of evolutionary ideas.” AIG has been at the forefront of debates regarding teaching creationism in schools, and its website urges kids to start a “Creation Club” in their own schools. The museum features exhibits on “creation science” as well as biblical history and dragons. AIG founder Ken Ham (who once debated Bill Nye), regularly tweets about marriage, abortion and the separation of church and state:

“Separation of church & State?” No such thing. There’s a State religion – the State is imposing the anti-God religion of naturalism (atheism) on generations of students – culture is now reaping the consequences of this intense religious indoctrination https://t.co/RqPl8po1D2

— Ken Ham (@aigkenham) November 16, 2017

And about evolution and science:

Secularists falsely accuse biblical creationists of being anti-science. But hose who believe in naturalistic evolution are the ones who are anti-science as they don’t think correctly about the difference between observational facts and interpretation. Evolution ‘s a fairy tale — Ken Ham (@aigkenham) November 12, 2017

2. Ark Encounter: Also in Kentucky and operated by Answers in Genesis, Ark Encounter is billed as a “full-size Noah’s Ark, built according to the dimensions given in the Bible.” The attraction features exhibits on Noah, ziplines and special Christmas events. The Ark Encounter has been at the center of a back-and-forth debate about tax status, beginning in 2014. When Kentucky withdrew the sales tax rebates of $18 million over issues of church and state, there was a lawsuit and Ark Encounter won. As of July 2017, the incentives were yet again in contest due to the Ark Encounter property being transferred.

3. Holy Land Experience: Self-described as “a living, biblical museum” the Orlando attraction includes a musical and claims to be educational, inspirational and historical. The Orlando Sentinel reported that the Holy Land Experience “receives a special tax exemption because it’s classified as a church instead of a theme park.” Inside the attraction, the “Church of All Nations” has a 2,000-seat capacity and is used for musical acts and performances as well as church services. The Holy Land Experience is owned by the Crouch family, founders of the televangelist Trinity Broadcasting Network, which faced controversy of its own due to a molestation lawsuit filed by the founder’s granddaughter.