Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 207

December 17, 2017

Where have all the good male poets gone?

(Credit: Getty/200mm)

If you look at some of the most popular male poets in the writing community at the moment, you will most likely come across large accounts like r.h Sin, and Atticus. With hundreds of thousands of followers, best-selling poetry books, and a gaggle of fans consistently commenting on their writing as if they were all-knowing enigmas in the literary climate, you’d think that you’d be dealing with men who were speaking out on issues from their point of view — men you could respect, and look up to, for juxtaposing their privilege in the world with the kind of art that spoke for something, that stood out.

However, that is not what you will find.

Instead, the eerie similarity between all of these male poetry accounts, is the fact that they use the female experience to promote themselves. And though their writing seems to reach millions of people, day by day, when are we going to admit that these are not authentic pieces of work being gifted to the world, but rather, formulaic pieces of boy band prose meant to be marketed, and digested by the very population of women they are silencing?

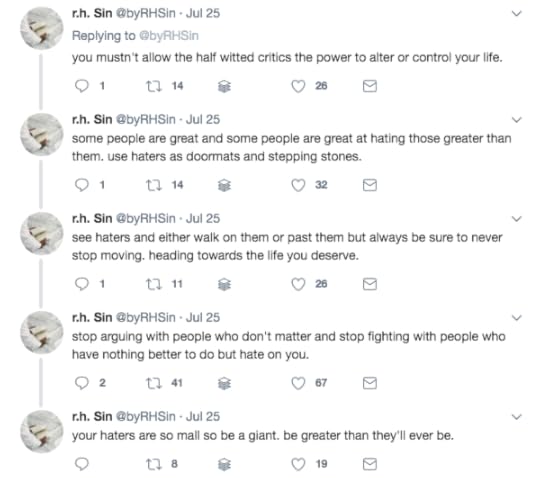

Earlier in the year, one of these writers, r.h Sin, took a hiatus from Twitter because the writing community started to question the credibility of his work. How could someone, who has lived his whole life as a male, write from the female perspective? And when asked this, how could someone, who has become wealthy off of the female experience, completely denounce those same women when they try to educate him on how he has no right to speak on their behalf? Reuben was offended by the backlash. Instead of opening himself up to understanding, in a compassionate way, the reason why some women struggle with his platform, he instead reverted, in a stunning example of male fragility, to calling them “half-witted critics” and to diminishing their concerns. The women who have so eagerly inspired the work that has made him a player in the poetry community, are now, less great than him. Less credible. Less talented. Less. Only worthy enough to be walked on. Ignored. Discredited.

And herein lies another issue. Popular male poetry seems to not only speak on behalf of women, but it also sensationalizes their struggle. Women deal with oppression in many different ways. This is a concept that is coming to the forefront in every climate, whether that is political, educational, occupational, and so on. However, male writers are making money off of the prettiness of their existence.

“There is nothing prettier than a girl in love with every breath she takes.” — Atticus

“She wasn’t bored, just restless between adventures.” — Atticus

“Don’t forget to kiss her often.” — Atticus

Is this all women are meant to be? Listless, and beautiful? Eager to be loved, constantly in need of male affection? If you do not see an issue in those words, let me change them to represent a male.

“There is nothing prettier than a man in love with every breath he takes.” — Atticus

“He wasn’t bored, just restless between adventures.” — Atticus

“Don’t forget to kiss him often.” — Atticus

It feels cheap. It doesn’t resonate, and that is because males have not been illustrated in the media, and in the world for that matter, the same way women have. This is why Julia Roberts will get asked about her beauty routine during important interviews, but George Clooney will not. This is why Brie Larson gets asked about the dress she is wearing on a red carpet, and Leonardo DiCaprio gets asked about global warming, and the state of planetary affairs. When you flip the role, when you change the words to reflect the men who are writing them, suddenly the writing itself doesn’t seem so beautiful. Suddenly, you see it for what it is, and that is why you will never see this scrawled across Atticus’ Instagram feed, or r.h Sin’s Facebook page — because they themselves know that such words are less than marketable.

As a female writer, who is simply just trying to represent my own human experience through my writing, I will not apologize for speaking out against this. I am not afraid of any male with a larger following trying to vilify, discredit, or denounce me. I am not afraid. If there is one thing I have learned about writing in the last few years, it is that people do not want to be told how they feel. They simply just want to represented. So here I am, as a female writer, who lives in this world as a woman, who lives in a world that does not pay her the same as males, who lives in a world where I am statistically not safe from predatory behavior, I am trying to represent other women. I do not need a male to do so.

So please, male poets — stop trying to do so. My voice is loud enough. Let me speak.

How virtual reality proves we are real

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality by Jaron Lanier (Credit: Henry Holt and Co/Getty/Grandfailure)

Even though it’s finally becoming more widely accessible, a lot of the joy in virtual reality (VR) remains in just thinking about it. One way to think about VR is through surreal thought experiments. Imagine the universe with a person-shaped cavity excised from it. What can we say about the inward-facing surface that surrounds the cavity?

Fourth VR Definition: The substitution of the interface between a person and the physical environment with an interface to a simulated environment.

You can think of an ideal virtual reality setup as a sensorimotor mirror; an inversion of the human body, if you like.

In order for the visual aspect of VR to work, for example, you have to calculate what your eyes should see in the virtual world as you look around. Your eyes wander and the VR computer must constantly, and as instantly as possible, calculate whatever graphic images they would see were the virtual world real. When you turn to look to the right, the virtual world must swivel to the left in compensation, to create the illusion that it is stationary, outside of you and independent.

Back in the early days I used to luxuriate when I described this most basic principle of VR to people who had never heard of it. People just flipped out when they first got it!

Wherever the human body has a sensor, like an eye or an ear, a VR system must present a stimulus to that body part to create an illusory world. The eye needs visual display, for instance, and the ear needs an audio speaker. But unlike prior media devices, every component of VR must function in tight reflection of the motion of the human body.

Fifth VR Definition: A mirror image of a person’s sensory and motor organs, or if you like, an inversion of a person.

Or, to make it more concrete:

Sixth VR Definition: An ever growing set of gadgets that work together and match up with human sensory or motor organs. Goggles, gloves, floors that scroll, so you can feel like you’re walking far in the virtual world even though you remain in the same physical spot; the list will never end.

The ultimate VR system would include enough displays, actuators, sensors, and other devices to allow a person to experience, well, anything. Become any animal or alien, in any environment, doing anything, with effectively perfect realism. Words like “any” show up a lot in VR definitions, but after working with VR, most researchers learn to be suspicious whenever “any” is uttered. What’s wrong with this innocent-seeming little word?

My position is that in a given year, no matter how far we project into the future, the best possible VR system will never achieve complete coverage of all the human senses or measurement of everything there is to be measured from a person. Whatever VR is, it’s always chasing toward an ultimate destination that probably can’t ever be reached. Not everyone agrees with me about that.

Some VR freaks think that VR will eventually become “better” than the human nervous system, so that it wouldn’t make sense to try to improve it anymore. It would then be as good as people could ever appreciate.

I don’t see things that way. One reason is that the human nervous system benefits from hundreds of millions of years of evolution and can tune itself to the quantum limit of reality in special cases already. The retina can respond to a single photon, for instance. When we think technology can surpass our bodies in a comprehensive way, we are forgetting what we know about our bodies and physical reality. The universe doesn’t have infinitely fine grains, and the body is already tuned in as finely as anything can ever be, when it needs to be.

There will always be circumstances in which an illusion rendered by a layer of media technology, no matter how refined, will be revealed to be a little clumsy in comparison to unmediated reality. The forgery will be a

little coarser and slower; a trace less graceful. But that’s not even the best reason to think that our simulations will not surpass our bodies.

When confronted with high-quality VR, we become more discriminating. VR trains us to perceive better, until that latest fancy VR setup doesn’t seem so high-quality anymore. The whole point of advancing VR is to make VR always obsolete.

Through VR, we learn to sense what makes physical reality real. We learn to perform new probing experiments with our bodies and our thoughts, moment to moment, mostly unconsciously. Encountering top-quality VR refines our ability to discern and enjoy physicality. This is a theme I will return to many times.

Our brains are not stuck in place; they’re remarkably plastic and adaptive. We are not fixed targets, but creative processes. If time machines are ever invented, then it would become possible to snatch someone from the present and put that person in a future, highly sophisticated VR setup. And that person would be fooled. Similarly, if we could grab people from the past and put them in our present-day VR systems, they would be fooled.

To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln: You can fool some of the people with the VR of their own time, and all of the people with VR from future times, but you can’t fool all of the people with the VR of their own time.

The reason is that human cognition is in motion and will generally outrace progress in VR.

Seventh VR Definition: A coarser, simulated reality fosters appreciation of the depth of physical reality in comparison. As VR progresses in the future, human perception will be nurtured by it and will learn to find ever more depth in physical reality.

Because of future progress in VR technology, we humans will become ever better natural detectives, learning new tricks to distinguish illusion from reality.

Both today’s natural retinas and tomorrow’s artificial ones will harbor flaws and illusions, for that will always be true for all transducers. The brain will constantly twiddle and test, and learn to see around those illusions. The unceasing flow of tiny learning forces—pressed finger against pliant material, sensor cell in the skin exciting a neuron that signals the brain as the pressure reflects—this flow is the blood of perception.

Verb Not Noun

Virtual reality researchers prefer verbs to nouns when it comes to describing how people interact with reality. The boundary between a person and the rest of the universe is more like a game of strategy than like a movie.

The body and the brain are constantly probing and testing reality. Reality is what pushes back. From the brain’s point of view, reality is the expectation of what the next moment will be like, but that expectation must constantly be adjusted.

A sense of cognitive momentum, of moment-to-moment anticipation, becomes palpable in VR.

So how can we simulate an alternate reality for a person? VR is not about simulating reality, really, but about stimulating neural expectations.

Eighth VR Definition: Technology that rallies the brain to fill in the blanks and cover over the mistakes of a simulator, in order to make a simulated reality seem better than it ought to.

Actionable definitions of VR are always about the process of approaching an ideal rather than achieving it. Approach, rather than arrival, is what makes science realistic, after all.

There’s a grandeur in the gradual way science progresses. It takes a while to get used to it, but once you see it, the incremental ascent of science becomes a thing of beauty and a foundation for trust.

I appreciate the infinite elusiveness of a perfected, completed form of VR in the light of this sensibility. Reality can never be fully known, and neither can virtual reality.

Ninth VR Definition: The investigation of the sensorimotor loop that connects people with their world and the ways it can be tweaked through engineering. The investigation has no end, since people change under investigation.

A Vice to Avoid

An obstacle to understanding is that popular metaphors for the nervous system come from commonplace gadgets that operate on principles that are alien to the brain. It is quite common, for instance, to think of eyes as being like cameras, ears like microphones, and brains like computers. We imagine ourselves as USB Mr. Potato Heads.

A better metaphor: The head is a spy submarine, sent out into the world to perform a multitude of experimental missions to try to discern what’s out there. A camera placed on a tripod typically takes a more accurate picture than one held by hand. The opposite is true for eyes.

If you immobilize your head in a vise, and to complete the picture, if you inactivate the muscles that move the eyes about in their sockets, you will have simulated putting your eyes on a tripod. For a moment you’ll continue to see as before, though it might feel as if you’re looking at a movie. Then something terrifying will happen. The world around you will fade to a sickly gray and then disappear.

Vision depends on continuous experimentation carried out by the nervous system, actualized in large part through the motion of the head and eyes. Look around you and notice what happens as you move your head in the smallest increments you can manage. Seriously, stop reading for a moment and just look around and notice how you see.

Move your head absolutely as little as you can, and you will still see that edges of objects at different distances line up differently with each other in response to the motion. This is called “motion parallax” in the trade. It’s a huge part of 3-D perception.

You will also see subtle changes in the lighting and texture of many things. Look at another person’s skin and you will see that you are probing into the interior of the skin as your head moves. (The skin and eyes evolved together to make this work.) If you are looking at another person, you will see, if you pay close attention, an unfathomable variety of tiny head motion messages bouncing back and forth between you. There is a secret visual motion language between all people.

If you are not able to perceive these things, try going into VR for a while and then come out and try again.

Vision works by pursuing and noticing changes instead of constancies, and therefore a neural expectation exists of what is about to be seen. Your nervous system acts a little like a scientific community; it is voraciously curious, constantly testing out ideas about what’s out there. A virtual reality system succeeds when it temporarily convinces the “community” to rally behind an alternate hypothesis. (If VR ever succeeds on a permanent basis, we will have entered into a new form of catastrophic political failure. The more we each become familiar with successful temporary VR experiences, however, the less vulnerable we become to this bleak fate.)

Once the nervous system has been given enough cues to treat the virtual world as the world on which to base expectations, VR can start to feel real, realer than it ought to, in a way, which is a dead giveaway.

The nervous system is holistic, so it chooses one external world at a time to believe in. A virtual reality system’s task is to sway the nervous system over a threshold so that the brain believes in the virtual world instead of the physical one for a while.

Tenth VR Definition: Reality, from a cognitive point of view, is the brain’s expectation of the next moment. In virtual reality, the brain has been persuaded to expect virtual stuff instead of real stuff for a while.

The Technology of Noticing Oneself

VR is a hard topic to explain because it’s hard to contain. It directly connects to every other discipline. I’ve had visiting appointments in departments of math, medicine, physics, journalism, art, cognitive science, government, business, cinema, and sure, computer science, all because of my work in this one discipline of VR.

Eleventh VR Definition: VR is the most centrally situated discipline.

For me, VR’s greatest value is as a palate cleanser.

Everyone becomes used to the most basic experiences of life and our world, and we take them for granted. Once your nervous system adapts to a virtual world, however, and then you come back, you have a chance to experience being born again in microcosm. The most ordinary surface, cheap wood or plain dirt, is bejeweled in infinite detail for a short while. To look into another’s eyes is almost too intense.

Virtual reality was and remains a revelation. And it’s not just the world external to you that is revealed anew. There’s a moment that comes when you notice that even when everything changes, you are still there, at the center, experiencing whatever is present.

After my hand got giant, it was natural to experiment with changing into animals, a splendid variety of creatures, or even into animate clouds. After you transform your body enough, you start to feel a most remarkable effect. Everything about you and your world can change, and yet you are still there.

This experience is so simple that it is hard to convey. In everyday life we become used to the miracle of being alive. It feels ordinary. We can start to feel as though the whole world, including us, is nothing but mechanism.

Mechanisms are modular. If the parts of a car are replaced one by one with the parts of a helicopter, then afterward you will end up with either a helicopter or an inert meld of junk, but not with a car.

In virtual reality you can similarly take away all the elements of experience piece by piece. You take away the room and replace it with Seattle. Then take away your body and replace it with a giant body. All the pieces are gone and yet there you are, still experiencing what is left. Therefore, you are different from a car or a helicopter.

Your center of experience persists even after the body changes and the rest of the world changes. Virtual reality peels away phenomena and reveals that consciousness remains and is real. Virtual reality is the technology that exposes you to yourself.

There’s no guarantee that a tourist in VR will notice the most important sight. I did not notice this most basic aspect of what I was working on until I experienced bugs in VR, like the giant hand. I wish I knew what threshold of elements might bring other people to appreciate the simplest and most profound quality of the VR experience.

Twelfth VR Definition: VR is the technology of noticing experience itself.

As technology changes everything, we here have a chance to discover that by pushing tech as far as possible we can rediscover something in our- selves that transcends technology.

VR is the most humanistic approach to information. It suggests an inner-centered conception of life, and of computing, that is almost the opposite of what has become familiar to most people, and that inversion has vast implications.

VR researchers have to acknowledge the reality of inner life, for with- out it virtual reality would be an absurd idea. A person’s Facebook page can continue after death, but not the person’s VR experience. Who is the VR experience for, if not for you?

VR lets you feel your consciousness in its pure form. There you are, the fixed point in a system where everything else can change.

From inside VR you can experience flying with friends, all of you transformed into glittering angels soaring above an alien planet encrusted with animate gold spires. Consider who is there, exactly, while you float above those golden spires.

Most technology reinforces the feeling that reality is just a sea of gadgets; your brain and your phone and the cloud computing service all merging into one superbrain. You talk to Siri or Cortana as if they were people.

VR is the technology that instead highlights the existence of your subjective experience. It proves you are real.

Bank funds and profits from private immigration prisons

(Credit: Eduardo Ramirez Sanchez via Shutterstock)

One of America’s largest banks, JPMorgan Chase, is quietly financing the immigration detention centers that have detained an average of 26,240 people per day through July 2017, according to a new report by the Center for Popular Democracy and Make the Road New York. Through over $100 million loans, lines of credit and bonds, Wall Street has been financially propping up CoreCivic and GeoCorp, America’s two largest private immigration detention centers.

The two organizations, part of Corporate Backers of Hate, a campaign from multiple immigration and social justice advocacy groups committed to revealing Wall Street’s financial ties to the Trump administration, examined Securities and Exchange Commission filings to determine the extent of the financial connections, and how much Chase stands to benefit from the mass incarceration of immigrants.

The details are hiding in plain sight, buried in a series of Securities and Exchange Commission documents, whose complexity frequently protects them from deeper scrutiny. This new report cuts through the financial jargon to reveal how Chase both finances and profits from facilities that divide families and place tens of thousands of immigrants at the mercy of private contractors, with little oversight or recourse from the deportation-happy Trump administration.

They range from the $13.23 million Chase loaned CoreCivic as of June 2017, to owning $89 million of their bonds, and $77 million of Geo Group’s as of October 2016. They were one of 11 banks that underwrote CoreCivic’s most recent 2015 corporate bond offering of $250 million, contributing $40 million and receiving an underwriting discount of $300,000. Chase also underwrote $42 million of notes for GEO Group’s 2016 bond offering and received an underwriting discount of $630,000. And that only scratches the surface of the relationship, which includes additional millions in revolving credit and stocks, including $72 million and $11 million invested in Geo Group and CoreCivic, respectively.

The impact of these numbers is not an abstraction for the families of the 12 immigrant detainees who died in custody in fiscal year 2017. Detainees are repeatedly denied medical care or given substandard food (one facility in Georgia had bones in its food). Melissa Nuñez, a member of Make the Road New York who was detained in a CoreCivic immigration detention center in New Jersey for six months, told AlterNet:

“I don’t have words to express my disgust that these companies are not only financing, but also investing in, private prisons and immigrant detention. What people like me have lived [through] in these private detention centers are the worst experiences human beings can live. They’re supposed to take care of you, and instead you’re subjected to harassment and abuse. No one should suffer this type of treatment. And no one should be positioning themselves to profit off it.”

Despite the massive financial investment from the likes of Chase, both CoreCivic and Geo Group continue to “charge the federal government a per diem rate anywhere between $30 per bed to detain immigrants for a short-stay facility to $168.64 per day, according to Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse data from 2016,” as ThinkProgress reported in November. For CoreCivic, Geo Group, and Chase, there’s profit in the pain of detention. While the report doesn’t detail exactly how much money Chase gets from its massive investments, they wouldn’t be consistently pouring in money if it wasn’t good for their bottom lines.

Activists were particularly concerned to uncover the extent of the funding, as publicly, CEO Jamie Dimon spoke out against Trump’s September 5th repeal of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, but privately, his company provides over $100M in direct investments for America’s largest private prisons.

The Center for Popular Democracy and Make the Road New York hope that exposing JPMorgan Chase will encourage other banks to divest their holdings from private prisons, says Ana Maria Archila, co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy. “Earlier this year, JPMorgan Chase Chairman Jamie Dimon said he was supporting President Trump out of patriotic duty,” she told AlterNet. “But true patriots stand up for the people and the values of a nation, not its rulers. Facilitating and enabling Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda directly contradicts the values that Dimon says he espouses.”

Instead, she continued, “that’s exactly what JPMorgan Chase is doing by helping to prop up private prison companies, which have boomed in the age of Trump and are being deployed to pave the way for Trump’s agenda of mass deportation.”

Ultimately, Archila said, “JPMorgan Chase — and all companies that have a stake in private prisons — need to divest from private prisons immediately and put their money where their mouth is when it comes to supporting immigrant communities.”

Read the full report.

Ilana Novick is an AlterNet contributing writer and production editor.

Finnish master Aki Kaurismäki discusses his unsentimental refugee drama “The Other Side of Hope”

Sherwan Haji and Niroz Haji in "The Other Side of Hope" (Credit: Pandora Film)

Of all the awards-season categories that industry prognosticators fuss over, none feels quite as confused as that of the “foreign film.” In an increasingly globalized world where a low-budget American action-thriller shoots in Bulgaria, or a would-be prestige production sets up shop in Norway — to take advantage of tax credits, and where talent feels free to pass between borders, industries and national cinemas unfettered — one is increasingly led to wonder: What even constitutes foreignness?

In the case of the Oscars and the Golden Globes, the distinction is made to seem simple: a foreign film is a film that features a predominantly non-English dialogue track. So despite Golden Globes foreign language film frontrunner “The Square,” by the Swede Ruben Östlund, featuring recognizable American talent (Elizabeth Moss, Dominic West), long stretches of talky scenes in English, and a recognizable/blandly conventional American-indie arthouse style, its mostly-Swedish soundtrack qualifies it, de facto, as sufficiently foreign.

This complicated issue of foreignesss also hangs over one of the Globes’ more conspicuous snubs, from a filmmaker ill-afforded his due respect among the peerage of Serious Foreign Filmmakers: “The Other Side of Hope,” by the low-key Finnish master Aki Kaurismäki. I am biased, I suppose, as Kaurismäki’s latest humanist comedy is my favourite film of 2017 (with respect to “Phantom Thread,” “Logan Lucky,” the harrowingly disturbing Japanese cannibal documentary I saw at a film festival, et al). Like any critic-slash-fan who sees his favorites abused, or just straight-up ignored, I’m left wondering: What about “The Other Side of Hope,” and Kaurismäki generally, fails to connect?

* * *

The failure to connect is, indeed, the faintly thumping heart of “The Other Side of Hope.” Sherwan Haji plays Khaled, a Syrian refugee who escapes to Helsinki, stowing away on a ship transporting coal. An early shot sees Khaled rising from a container of dark ash as the ship docks, his face black and sooty. He is simultaneously rendered quasi-invisible against the inky night sky, and marked as different, as “other,” amid the overwhelming ethnic whiteness of Scandinavia. Khaled seeks asylum, but is turned away by Finnish bureaucrats, who themselves aren’t so much unfeeling as they are victims of systemic circumstance. He finds shelter with Wikström (Sakari Kuosmanen), a grumpy gambler trying his hand in the restaurant business.

Over the course of its lean 98 minutes “The Other Side of Hope” tackles all manner of issues that might, one imagines, bait awards-season voters: the limits of globalization, the refugee crisis, and the failure of Western nations to respond to seemingly unfathomable need. It also finds its footing in real-world geopolitics, and problems facing exiles seeking refuge in Finland. “Until spring 2015 about 1,500 refugees came to Finland annually,” explains the typically taciturn Kaurismäki, answering questions via email in a rare interview opportunity. “Then suddenly in summer and autumn came 35,000 in three months. A rumor had spread, especially in Iraq, that Finland is a specially refugee-friendly country. Unfortunately, this has never been the fact.”

“The Other Side of Hope,” and in particular the dynamic between local malcontent Wikström and the hard-pressed, but just as hard-headed, Khaled, grew out of Kaurismäki’s observations on how his fellow Finns handled this sudden influx of asylum-seekers. “I was surprised how positively common Finnish people reacted, minus the normal 10 percent of, how should I say it politely, dummkopfs,” he says. “The government is another case. Now they throw out everybody they possibly can.”

Like so many of Kaurismäki’s films, “The Other Side of Hope” finds resonance in the human capacity for small-scale acts of empathy. The Finnish director’s worldview has sometimes been described as one of “hopeful cynicism.” It may sound like an obnoxious oxymoron, but it holds true nevertheless. Kaurismäki’s is a world where quiet compassion teems on the edges of utter dispassion. Expect the worst from people, and even trivial-seeming acts of kindness blossom into acts of miraculous grace. And perhaps it’s because, well, they are. In a world where people seem so rotten, a person can still possess the capacity for decency. “I like people,” Kaurismäki has said. “But mankind as a whole? I’m not so sure.”

This sort of tension, this ambivalence, makes “The Other Side of Hope” feel not just “timely” or “topical” but universal. Kaurismäki apprehends complex feelings of caring for your neighbor while simultaneously despairing for the whole project of civilization. If people can be so deeply, surprisingly kind on the intimate, micro-scale, how can they be so appallingly awful at the level of societies and nations?

“The Other Side of Hope” addresses this problem without sop or sentiment, surveying the ongoing refugee crisis with a caustic, unsentimental eye. Even Khaled’s increasingly violent run-ins with a gang of shaved-bald Helsinki neo-Nazis are treated without sensation. They are not galling acts of violence but matters of fact: the natural result of right-wing populism that arose from the European migrant crisis, which itself emerged from the crisis of globalization. “The story of migrants in Finland (and Europe in general) can’t be told without showing physical and mental violence,” the director insists. “I show violence now and then in my films, but also take care that it never gives any pleasure to the spectator.”

This draining of sensation may account for a certain chilliness in the reception to “The Other Side of Hope,” and Kaurismäki’s films more generally. Where bigger-ticket European filmmakers are lauded for their naturalistic humanism (Belgium’s Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne) or button-pushing cynicism (Denmark’s Lars von Trier, Austria’s Michael Haneke), Aki Kaurismäki’s distinct melding of these two Euro-arthouse poles tends to get lost in the shuffle. His films tend to challenge — or just straight-up ignore — the experience that many viewers have come to associate with the category of the “foreign (language) film.” Audiences are acclimatized to explosions of affect or discomfort, not the accidents of gesture or the quiet treachery of top-down authority. In a cinematic landscape of screeching emotion and howling importance, “The Other Side of Hope” is gentler — a major work in a minor key.

There is a deliberate affectlessness to Kaurismäki’s films, and his filmmaking, that may feel alienating. The performances are stilted, the compositions are flat, the stories totally quotidian while unfolding strangely like fables. Where foreign films are typically treated as empathy tests, meant to challenge or provoke or deeply move, Kaurismäki’s movies seem mundane. But then, this is the point: that economic, social, and interpersonal callousness is mundane and matter-of-fact. Despite the tweaked prosaic quality of Kaurismäki’s characters, his compositions, his whole worldview, one gets the sense watching “The Other Side of Hope” that this is very much our world as it is, for better or worse.

There is no grand redemption in “The Other Side of Hope,” nor are there any obvious lessons learned. It’s a film of quietude, of stillness, and of biting absurdist humor. Yet in its own strange way, it offers a lesson on how to be in our troubling times. “It is not obligatory to be ‘nice,’” says Kaurismäki, whose characters rarely offer more than the odd wry smile, “but if you are ‘human’ you can never be cruel either.”

It’s the sort of brusque, weirdly compassionate, totally matter-of-fact statement about the governing of human affairs that, in an era marked by hysteria and crass sentiment, feels entirely foreign.

This portable battery pack charges up to 3 devices at once

Whether you’re planning for delays at the airport during holiday travel season, or just plan on waiting for your siblings to finish shopping at the mall, this Graphene 8K HyperCharger PRO gives your devices a boost when there’s not a single outlet in sight.

This highly portable, sleek little battery packs a big punch: its 8,000mAh battery capacity means you can charge three devices at once, no problem. Plus you can power up pretty much any device, thanks to two built-in charging cables, plus an additional USB charging port.

The sleek, low-profile design features fast-charging technology — and it even includes the revolutionary anti-gravity NanoStik PRO pad, which allows the pack to attach to your smartphone without adhesives. That means you won’t even need to remember to bring it along with you (and you can still get a full charge, no matter where you are).

Charge up three devices on the go: usually, this Graphene 8K HyperCharger PRO is $79.99, but you can get it now for $39.99, or half off the usual price.

December 16, 2017

How Coca-Cola invented Christmas as we know it

(Credit: Katherine Welles/Shutterstock)

When you see Santa today, all fat and jolly and rosy-cheeked, you’re seeing an image created for and promoted by the Coca-Cola Company for over 80 years. Michigan artist Haddon Sundblom created the Santa Claus we know so well in 1931, for Coke’s “Thirst Knows No Season” campaign.

Sundblom modeled his Santa on “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” an 1822 poem by Clement C. Moore. While people often point to that poem as the defining element of Santa Claus’ style, or to Thomas Nast’s versions of Santa Claus for Harper’s, it wasn’t until Sundblom and Coke codified the Claus in mass advertising that the world adopted and accepted that version of Santa Claus. Prior to 1931, Santa Claus was depicted all sorts of ways, from an old Diogenes-type man to a bishop to a sprite-like troll.

The idea of Santa—a gift-giving deity who comes bearing gifts in the heart of winter—is ubiquitous across Western cultures for centuries, from Germanic pagan Yule festival and their god Wodan (strikingly similar to the Norse god Odin) to the Dutch Sinterklaas and the English Father Christmas. Going back to the fourth century, Saint Nicholas was a Greek Christian bishop known for giving gifts.

And like many things in the United States, it was our melting pot of cultural origins that morphed Santa into its own American thing entirely—not quite Father Christmas, not quite Odin or Wodan. He became the American Santa, as sold to the world by Coca-Cola: A fat old white man clad all in red.

American families still place statues of Santa on their mantle and leave food and drink out for him on the night before Christmas. His image is splashed everywhere, supposedly not as a symbol or a god to worship, but as a decorative marketing tool.

That makes Coke’s Santa quite possibly the first time a corporation invented something to sell a product that the masses appropriated to celebrate the biggest American financial holiday of the year. Coca-Cola probably didn’t realize it was creating and defining a new god for generations of Christmas visions and shopping trips, but that is exactly what Coke did.

So let’s pause for a moment and consider: Do we really want to keep celebrating Christmas with a Santa created as a marketing tool? It’s as if we’ve been stuck in a Christmas rut since post-World War II. We replay the same holiday music, and watch the same movies and TV shows that came in the 1960s. “A Charlie Brown Christmas” aired in 1965—commissioned and sponsored by Coca-Cola.

Sure, nostalgia feels great this time of year, but so do any number of other intoxicants. It doesn’t mean it’s good for you. (In fact, nostalgia was once considered a mental illness.)

We as a culture might be wise to pause and ask if these corporate-rooted traditions and replay of a manufactured past are really the deep-seated beliefs we want to continue to cultivate and pass on to future generations. If they aren’t, how do we celebrate Christmas? How do we reinvent a holiday to have a deeper meaning than what appears, on the surface, to be a holiday celebrating the god of capitalism rather than the birth of Christ?

First, we decide what we want to keep in our annual traditions and what we want to release to the past. Second, we determine how we want to celebrate the holiday. What do we truly want to celebrate, honor and worship? How do we want to decorate? What do we want to do? What do we want to believe, and teach our children to believe?

Plenty of atheists, agnostics, Christians, Jews and American Muslims alike have already done this in their own lives, eschewing the birth of Christ or Santa or the gift-giving aspects of the U.S. holiday while fully embracing that which they do believe in—almost universally, time spent sharing food and drink with loved ones and new friends alike. A midnight mass or Chinese food and a movie, it seems, can be just as meaningful as a visit from Santa. So are sharing a meal, cooking, giving handmade gifts, or giving to local families in need.

Worshipping and celebrating the birth of Christ also doesn’t require a statue of or a visit from Santa. There’s simply no need for Santa to be a part of any of that—unless, of course, you want him to be.

But that’s where it starts. In your values, and what you want the holiday to be. You don’t need to let the corporate tycoons and marketers define and exploit a holiday you treasure. Your choices—your internet clicks, decorations and shopping habits—have the power to change how you celebrate this holiday. How exciting is that?

It just requires a bit of mindfulness and imagination about what you want the holiday to be for you and your family and future generations. Why not try something new?

Or just have some fun! Hang a Santa mannequin outside, from your home’s gutter. After all, Santa has become the embodiment of our culture’s capitalistic fervor. There’s no need to take him so seriously.

How to talk about sexual harassment with tweens and teens

(Credit: Getty/AntonioGuillem)

Groping. Grabbing. Lewd talk. These are not words any parent wants their kids to associate with sex. But tweens and teens are getting an earful — and not from the 6 o’clock news where you know what they’re seeing and hearing. Instead they head to their phones and devices to check YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and other online news outlets. For kids, memes, viral videos, late-night talk shows, and even user’s comments on stories are news. If you have tweens and teens, you know that the fastest way to get them to clam up is to question where they’re getting their information … or talk about sex.

But the allegations of sexual harassment against famous and powerful men are too significant to let kids figure out for themselves. Now, in fact, is a great opportunity to talk to kids about the role the media plays in our lives, including how it grabs our attention, shapes perspectives, reflects a changing culture, and starts worldwide conversations. While talking to little kids about sexual harassment is challenging because they don’t yet know about sex, older kids (especially teens) may enjoy grappling with the ethical dilemmas raised in the news. Discussing how information is packaged and distributed — and who’s behind it — helps kids develop critical thinking skills, so they can put the news in context, understand different points of view, develop their own perspective, and observe the ways information makes them think and feel. Try these tips to talk to tweens and teens about sexual harassment in the news:

Ask questions and listen. Draw kids out by asking what they’ve read and watched and what they think about it. Say: “Are your friends or teachers talking about the latest news?”, “Why do you think this is such a big deal?”, “Who do you believe and why?” Encourage them to show evidence for their opinions. Get more tips on teaching media literacy to kids.

Compare how different apps, sites, and TV shows cover the same story. Look at your teen’s favorite media, such as YouTube, Twitter, Buzzfeed, Facebook, and Snapchat. Watch clips from The Daily Show, Last Week Tonight with Jon Oliver, and even Weekend Update on Saturday Night Live. Look at the headlines, videos, memes, and other “hooks” they use to get people’s attention. Ask:“Can you tell what’s a legitimate story, what’s satire, and what might be ‘fake’ news?”, “Who do you think the audience is for each site?”, “Does humor make a story less credible — or more believable?”

Read user comments. Though internet comments may be littered with swear words and negativity, they offer a chance for kids to consider how issues can be divisive and emotional. Sites such as Reddit feature lots of opinionated commentary. Understanding others’ views is an important step toward finding common ground. Ask: “How would you engage with this person in real life?”, “Is it possible to have a dialogue with people who disagree with you online?”, “Do you think the commenter has credibility on the issue they’re weighing in on?”

Watch old movies. Old films are little time capsules of cultural norms that may be completely outdated and even puzzling for kids who’ve grown up in the new millennium. Compare movies with outdated gender roles to ones that defy gender stereotypes and discuss how our attitudes have changed.

Talk about objectivity and bias. The news is supposed to be completely objective. But the author’s perspective can make its way into a story, through word choices, quotes, and even the people used as sources. And on social media, bias can be reinforced when people read only stories that validate their point of view and aren’t exposed to the full range of news and opinion on a topic. Ask: “Does the author make assumptions about the reader?”, “How would people who grew up differently from you feel about this story?”, “What news stories show up in your social media feeds? Do they represent a certain viewpoint?”

Talk about consent. When you have The Talk with your kids about the birds and the bees, remember to discuss consent. Tweens and teens need to understand that they must give and get permission to initiate anything sexual — from talking to touching. Popular media can give kids the wrong idea about boys’ and girls’ roles in relationships. And when kids flirt online, they can send mixed messages. When you evaluate news stories about sexual harassment, talk about how people can abuse their power by ignoring others’ basic needs. Make sure kids understand that if anyone violates them or makes them feel uncomfortable sexually, they should report it to an adult. These books can help kids understand the importance of consent.

Has the internet made us cold?

(Credit: Getty/Nicolas Asfouri)

Is technology making us cold? It’s a question I’ve been struggling with for the past few weeks. It started after one of my former students, Stephon, whom I taught when he was in 10th grade, was murdered. Stephon was cool and silly, and he loved to poke fun at any and every situation. So of course everyone posted his image all over social media with loving captions and funny stories that all ended in #RIP, #FlyHigh and #GoneButNeverForgotten. This lasted about two days and then, well, it was over.

I bumped into some of his friends on the basketball court a few days later. I was dropping off some books at this east Baltimore high school and one the guys spotted me. “Hey, Mr. Watkins! What’s up?”

I walked over to the gate and they started telling me about what they’d been up to since the last time I saw them. We laughed for 15 or 20 minutes, and then I asked them if they were OK.

“Dealing with death is tough,” I told them. “We all loved Steph. Y’all reach out if y’all need me.”

We reminisced for about three minutes, and then they went back to talking about basketball, women and Instagram. They had glossed over his death, almost like it hadn’t happened. I don’t know if that’s a coping mechanism or if they were truly over it.

I lost a close friend back in high school when I was around their age. His name was DI and he was cooler than most — to me anyway. He wore his long jeans shorts, colorful tank tops and matching New Balance sneakers up and on Jefferson Street on the hottest of summer days. He always perched his DJ-quality headphones on top of his bush and blasted Nas, Biggie or a member of the Wu Tang Clan. “DI!” you would have to scream at the top of your lungs to get his attention, as the music leaked from the cushion covering his ears. He could rap, too, but we all wanted to make the NBA — that’s a common Baltimore dream that most of us rusty black boys share, generation after generation. We spend hours on the court, beating the spit out of each other, trying to prove who’s superior. DI and I parted ways after one of those long nights of hooping and I never saw him again. They say he was shot from behind while wearing his headphones, and he never heard the killer coming.

The bulk of my friends got DI tats, and we drank gin and mourned his death for weeks. Dude was the topic of every conversation, all over my neighborhood, from when he passed in the spring, well throughout the winter. And we used to get his face airbrushed on our t-shirts every Memorial Day. That was in the ’90s, years before new realities could be created with usernames and catchy hashtags.

I use social media, too. And admittedly, I don’t mourn in the same way. Close friends and family members I lost after social media became a daily part of my life don’t seem to cloud my thoughts as much as those who died prior to the smartphone era. It sounds horrible, but it’s true. It’s almost as if the grief is disappearing into cyberspace or the cloud. You know how we used to have physical CDs and books, and now we just stream? The same is happening with personal relationships. The internet has made it easier to cut people off. We are streaming relationships now instead.

About two years ago, I let my cousin stay with me rent-free until he could get back on his feet. He had just opened a car lot, so his money was tight. I never complained about the piles of dishes he left everywhere or yelled at him about his inability to cut off the hall light. Family looks out for family, right? So he started selling cars, moved out and was doing well. I bought a car from him for a friend who had just been released from prison, and it lasted two weeks. My cousin wasn’t trying to honor his own one-month warranty. We had to go into his office, show him his own contract and make him honor it. I let that slide. And then he sold our cousin a lemon and I had to cut him off.

I made him refund the money, but that was the final straw for me. I never spoke to him again. He told my mom and all of our aunts, but I didn’t budge. I blocked his number in my phone, blocked him on Twitter and would’ve blocked him on Instagram if he was on Instagram. I went one week without communicating with a person I used to talk to almost every day, and I forgot about him. After two years with no contact, he stopped reaching out. My mom doesn’t bug me about it anymore. That’s probably because we are all on social media.

Now, this just my personal experience. But I don’t think that this could happen without social media, for two reasons. First, the internet always gives us something to do. Checking Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Pinterest and Snapchat can easily knock four hours out of your day. Double that if you have a large following, and triple it if you’re trying to use social media for business. I’m not a scientist, but I’m pretty sure it’s the reason why I see people walking up and down the street with tilted heads, fingering their phones all day.

The second reason is connected to the decreasing value of human interaction. Do we still value that? Every time I address groups of kids, I always ask them if they’d rather talk on the phone or text. Texting is always the answer. Add that to the way that apps have made people more accessible and dispensable. You can break up with your significant other and find a new one in minutes on an app. You can find new friends on apps, too. Get in fights with them, block them and then repeat the process all over again. These are options our parents didn’t have.

“Professor Watkins,” a college freshman said to me recently, “I don’t really date anymore. I kind of order sex on Tinder!”

The kid shrugged his shoulders, laughing along with the rest of the class. And that’s where are right now.

Technology has blessed us in many ways. I don’t really hear about long lost family members anymore, because they’re all on Facebook. But how valuable are those relationships? Especially if they are reduced to arguments that start with phrases like, “Why didn’t you like my picture?” or “Why did you like that girl’s picture,” and my favorite: “Why is your ex following you?” And then you can erase that person with a block.

Who knows what the long term effects of digital life will be? I’m going to reach out to my cousin before it’s too late.

American Jews and charitable giving: An enduring tradition

(Credit: (AP Photo/Francisco Seco))

Even though only about one in 50 Americans is Jewish, U.S. Jews donate at high levels, both as individuals and as a community.

As a scholar who studies community philanthropy, I am doing research to discover what accounts for this outsized generosity and why Jews play such a big role in American philanthropy.

While mapping where these donated dollars go, I’m finding that the many reasons why this penchant for giving arose can help explain the strength of support among American Jews for non-Jewish causes.

By any measure

Most Jews, regardless of their economic status, heed their religious and cultural obligations to give. In fact, 60 percent of Jewish households earning less than US$50,000 a year donate, compared with 46 percent of non-Jewish households in that income bracket.

The average annual Jewish household donates $2,526 to charity yearly, far more than the $1,749 their Protestant counterparts give or the $1,142 for Catholics, according to data from Giving USA.

And a larger percentage of Jews give to charitable causes than households of other faiths, according to Connected to Give, a joint effort by foundations to measure religious giving trends. Some 76 percent of American Jews gave to charity in 2012, compared with 63 percent of Americans who observe other religions or are not religious.

Interestingly, the same study also found that Jews, black Protestants, Evangelical Protestants, mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics give at similar levels to congregations and to other causes. However, Jews give relatively less to congregations and more to other causes.

North American twist

So what’s behind this extremely charitable behavior?

Two explanations involve education and wealth, traits strongly correlated with philanthropy.

The Jewish community is among the nation’s most educated and wealthy demographic groups. American Jews have an average of 13 years of schooling, the highest for a major U.S. religious community. And 44 percent belong to households with annual incomes of $100,000 or more, the most for any major ethno-religious community.

This 1908 photo depicts Passover matzo being given away an early Jewish mutual aid society in New York City.

Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com

As education enhances charitable giving at all income levels, it is one key to understanding Jewish generosity. And donors of all faiths, regardless of their religious practices and identities, tend to give more money when their income rises.

Many wealthy Jews, including former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, hedge fund investor George Soros and homebuilder Eli Broad, regularly make the Chronicle of Philanthropy’s list of the nation’s 50 biggest donors.

Theological foundations

And naturally, another reason for Jews’ charitable tendencies is their faith, regardless of how religious they are. There is a strong theological foundation for the Jewish community’s robust giving, just as is the case with other religions.

Expressed in Hebrew, the Jewish concepts of tzedakah (charitable giving), tzedek (justice) and chesed (mercy or kindness) instruct and compel all Jews to give to charity and treat people who are less fortunate with compassion.

Even today, many Jews embrace a concept known as the “eight degrees” of charitable giving first articulated by Moses Ben Maimon, a 12th-century intellectual who was born in Spain and later resided in Morocco and Egypt.

Known as Maimonides or Rambam, he created a metaphor of an eight-rung ladder that donors can ascend to get closer to heaven. At the lowest level, donors give grudgingly. At the highest, they help people in need become self-sustaining.

And while Jewish charity has theological roots, many Jews who aren’t religious give generously. One prominent example is Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who runs a massive charitable initiative with his wife Priscilla Chan.

Sculpture of Maimonides in Cordoba, Spain.

Juan Aunion/Shutterstock.com

Community philanthropy

The U.S. Jewish community not only gives more than other religious groups, it gives differently. Jews have developed unique patterns of charitable giving and philanthropic behavior as a central way to express Jewish identity.

Traditionally U.S. Jewish philanthropy has been embedded in central Jewish communal organizations such as Jewish federations, regional organizations that give collectively to causes in the U.S. and abroad.

These unique organizations exemplify the ethnic, nonreligious expressions of Judaism. They also demonstrate the Jewish community’s tradition of charitable giving as a group effort.

Thus, many Jewish philanthropic institutions in North America take a largely nonreligious approach to Jewish social action.

Making grants

Beyond identifying what drives Jewish giving, I wanted to explore who benefits most from their generosity.

For the past year and a half, I have been studying the giving patterns of North American Jewish grant-making institutions.

These include nearly 150 Jewish federations. There are also thousands of Jewish community foundations, family and corporate foundations and donor-advised funds, such as the Jewish Communal Fund, which pools giving by about 6,000 affluent people.

I found that many of these U.S. and Canadian institutions actually give more to non-Jewish causes than to Jewish ones. In fact, my preliminary findings suggest that despite differences between distinct categories of grant-makers, at most an average of 25 percent of this money backs Jewish causes.

All told, based on my research at the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University, I estimate that these various philanthropic efforts give more than $9 billion every year to charitable causes.

Most of these funds flow to social, welfare, educational, health, research, science, advocacy, art, cultural and environmental causes. Donations support tens of thousands of local and international nonprofits serving a wide range of ethnic and religious communities in the U.S., Israel and elsewhere.

Mega-donors

Separately, I also analyzed the giving patterns of the 33 Jews who made the 2016 Forbes 400 list of the richest Americans. From what I found, an average of only 11 percent of the giving through their foundations backs exclusively Jewish causes.

Their contributions mainly support secular causes, such as the $142 million gift George Kaiser – the entrepreneurial son of Holocaust refugees who settled in Oklahoma – gave the Tulsa River Parks Authority in 2014.

Additional research indicates that only 9.6 percent of gifts from so-called “Jewish mega-donors” between 1995 and 2000 that totaled $10 million or more funded Jewish causes. Nearly half of them supported higher education and none supported religious causes or annual appeals to give to and through Jewish federations.

Billionaire Stephen Schwarzman’s $150 million gift to Yale University in 2015 is one example of Jewish support for non-Jewish causes. On the other hand, some of these major gifts support largely Jewish universities, such as the $400 million the estate of Howard and Lottie Marcus bequeathed to Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel.

Charitable traditions

One reason for this tendency is that Jewish charitable traditions support giving to Jewish and non-Jewish causes alike. Many Jews perceive donations supporting social service providers and social justice advocates as a way to follow Jewish religious laws, even when their gifts benefit other religious and ethnic communities.

And since many Americans Jews emigrated to the U.S. to escape persecution and discrimination elsewhere, mostly in Europe and the Middle East, I believe this history makes it natural for them to identify with and support groups that are currently suffering or even oppressed, whether they are Jewish or not.

I have also seen that over time, Jewish communal philanthropy is becoming less centralized as new kinds of giving institutions and practices emerge. In addition, priorities are changing: Philanthropy serving the Jewish community is becoming less dominant than charity serving other communities.

I have also seen that over time, Jewish communal philanthropy is becoming less centralized as new kinds of giving institutions and practices emerge. In addition, priorities are changing: Philanthropy serving the Jewish community is becoming less dominant than charity serving other communities.

Hanna Shaul Bar Nissim, Postdoctoral Fellow, Maurice and Marilyn Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies, Brandeis University

Heir apparent to Saudi throne on billion-dollar shopping spree

FILE -- In this Tuesday, March 14, 2017 file photo, President Donald Trump stands with Saudi Defense Minister and Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman before lunch in the State Dining Room of the White House in Washington. With an eye toward Washington, leaders of a fractured and conflict-ridden Arab world hold their annual summit Wednesday, March 29, 2017, seeking common ground as President Donald Trump weighs his approach toward the region. The stalled Palestinian quest for statehood, is an issue that host Jordan says will take center stage. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File) (Credit: AP)

When Saudi Arabian police arrested a dozen princes, ministers and a billionaire investor in the span of one night, many interpreted the move as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman flexing his muscle. “The sweeping campaign of arrests appears to be the latest move to consolidate the power of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the favorite son and top adviser of King Salman,” wrote the New York Times on the day after the raid.

Indeed, heir apparent Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman may already be running the show in Saudi Arabia, as his father, the absolute monarch Saudi King Salman, is widely regarded to be suffering from deteriorating health. These sweeping arrests, along with the Crown Prince’s announcement of a slate of reforms — including allowing women to drive and enter sports stadiums, and ending a ban on movie theaters — seemed poised to reorganize major aspects of Saudi society and life.

Yet while Mohammed bin Salman’s reforms have been playing out, in the background the Crown Prince has been on a quiet shopping spree, spending billions on yachts, art, and now, an opulent French estate.

The Times reported today that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was behind the 2015 purchase of a $300 million chateau outside of Versailles. The opulent mansion features a “gold-leafed fountain, marble statues, and [a] hedged labyrinth” on a 57-acre plot.

The identity of the buyer of the chateau was obscured by shell companies around Europe, suggesting that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman did not necessarily want his purchase known.

Recently, the Crown Prince was also the buyer of a 440-foot yacht, for which he paid a reported $500 million; and a Leonardo da Vinci painting, “Salvator Mundi,” for $450 million. Those three purchases alone add up to $1.25 billion — about equivalent to the gross domestic product of the Solomon Islands. It is unclear if the da Vinci painting was a personal or an institutional purchase; it is described as planned to be put on public display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

For two years, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was successful at obscuring his purchase of the French chateau. And it makes sense that he would want to hide his absurdly expensive tastes and the jetsetting freedom that accompanies. While his home country is relatively affluent, largely due to oil exports, it is considered an authoritarian regime by most analysts. Within the country, human rights abuses run rampant. “In 2016,” wrote the NGO Human Rights Watch, “Saudi authorities also continued their arbitrary arrests, trials, and convictions of peaceful dissidents. . . . Dozens of human rights defenders and activists continued to serve long prison sentences for criticizing authorities or advocating political and rights reforms. . . . Authorities continued to discriminate against women and religious minorities.

The Kingdom imports many migrant workers from other parts of the world, particularly Southeast Asia, to work in Saudi Arabia; lured by the promise of high wages, many arrive to find themselves treated like second-class citizens, overworked or glorified indentured servants. A Reuters report from 2016 described the life of a group of exploited migrant workers in a labor camp in Qadisiya, Saudi Arabia:

Migrant construction workers, abandoned in their thousands by Saudi employers in filthy desert camps during the kingdom’s economic slump, say they will not accept a government offer of free flights home unless they receive months of unpaid wages.

The plight of the workers, stranded for months in crowded dormitories at labor camps with little money and limited access to food, water or medical care, has alarmed their home countries and drawn unwelcome attention to the conditions of some of the 10 million foreign workers on whom the Saudi economy depends.

The incongruity between Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s life of excess, and the everyday oppressive existence of many residents of the Kingdom, exposes a double standard in Saudi Arabian society. Indeed, the inequality between royal haves and Saudi have-nots is more egregious in context: the House of Saud is estimated to have assets totaling $1.4 trillion — twice the value of the Kingdom’s annual GDP.