Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 149

March 2, 2018

Understanding the U.S. political divide, one word cloud at a time

(Credit: AP Photo/Steve Helber)

America’s political divide goes by many names — rural-urban, blue-red, metro-non-metro and left-right. We are told it is bad and that it is only getting worse, thanks to phenomena like fake news, economic uncertainty and the migration of young people away from their rural homes.

And it’s fairly common for one side of the divide to speak for the other, without knowledge of who the other really is or what they stand for. An example: The term that’s been used to describe my state’s booming economy — “Colorado’s hot streak” — is in some ways the opposite of what many rural Coloradans are experiencing. But their story rarely makes the news.

Telling someone about metro versus non-metro poverty, suicide or adult mortality rates scrapes the surface of how things are felt by those living these statistics. Descriptions never seem to do justice to how these divides are experienced, which speaks to the wisdom of the writing rule, “Show, don’t tell.”

What is that divide, really? And how can we show it?

How to communicate the divide: word clouds

I am a professor of sociology and have been studying rural and agriculture-related issues, both in the U.S. and abroad, since the late 1990s. Prior to that, I was busying growing up in rural Iowa, in the far northeast corner of the state.

A few years ago I interviewed farmers and agriculture professionals in North Dakota and members of a very different agricultural community: an urban farm cooperative. In the case of this particular urban farm cooperative, land was placed in a trust to support urban agriculture and leased to members on a sliding scale. I promised not to divulge the cooperative’s location in order to elicit participation within this group.

I wanted to know how these two communities talked and thought about issues like sustainability and food security. I was also interested in how these group members, whose lives were focused on agriculture in very different ways, illustrated some of the divides in our country.

I had a hunch these groups differed in more ways than their zip codes and socio-economic backgrounds. The North Dakota group, for instance, was all white and predominately male, whereas the urban population was considerably more diverse. The study eventually made its way into the peer-reviewed journal, Rural Sociology.

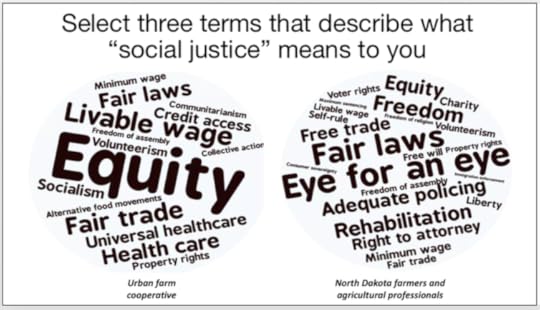

As part of the study, I built four word clouds, visual representations of words I gathered from survey questions. If a picture is worth a thousand words, these particular images show more than thousands of sentences ever could: the divergent worldviews of these two groups. And they show us an angle of the aforementioned political divide that has been missed.

Individuals in each group were asked to “select three terms that describe what ‘social justice’ means to you” and “select three terms describing what ‘autonomy’ means to you.”

Before giving their answer, participants were shown a list of some 50 terms, designed by me to relate specifically to each question. Other terms were explored as well, but only two terms — social justice and autonomy — are discussed here because they complement each other in interesting ways.

The terms respondents chose were then fed into software that generated word clouds, which are graphics that show the most-used terms in large letters, the least-used terms in smaller letters. (Disclaimer: I make no claims that these clouds speak for all Americans, farmers, North Dakotans, metro residents, etc. I also recognize that the cooperative experience could color the responses of those in the urban sample.)

Individual vs. collective

Perhaps the most immediate contrast with these social justice responses lies in how the rural North Dakotans’ image evokes a number of words associated with punishment, policing and due process, such as “eye for an eye” and “right to attorney.” These are terms associated with criminal law and the criminal justice system.

The terms chosen by the urban land cooperative, in contrast, made no reference to punishment or policing when describing their visions of social justice. Instead, they chose terms that overwhelmingly emphasized, to quote the most used term to come from this group, equity.

Word clouds provided by Michael Carolan, CC BY

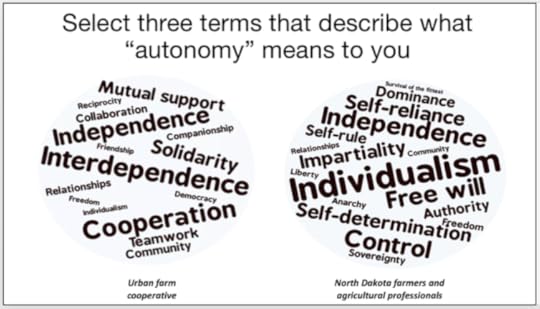

There was also a divergence between groups in terms of whether social justice was something individuals achieve or whether it denotes a collective response, where a community (or even society) as a whole ensures justice for individuals. To explain this point requires that I introduce two more word cloud images, produced in response to the autonomy question.

These autonomy word clouds demonstrate that the above contrasts are no fluke and are important for two reasons. First, they validate that there is something “deeper” afoot. And second, they inform the social justice images.

Note the repeated emphasis the North Dakota group placed on terms like “individualism,” “self-determination,” “self-rule” and “authority.” In philosophical parlance, these terms align with the tradition of individualism, a position that emphasizes self-reliance and that stresses human independence and liberty.

Word clouds provided by Michael Carolan, CC BY

These terms also tie in well with the North Dakota group’s social justice word cloud, with its emphasis on words that emphasize individual responsibility, e.g., “eye for an eye,” and individual freedoms, “fair laws” and “right to attorney.”

This stands a world away from the urban farmer cooperative group, who associated autonomy with “interdependence,” “cooperation,” “solidarity” and “community.” It might appear counterintuitive to link autonomy with concepts like interdependence and solidarity, until you hear individuals from this group explain their position.

A single mother, for example, spoke directly to how independence arises for members of this group because of interdependence, rather than in spite of it.

“We can accomplish a heck of a lot more together; I feel like I have more control over my life, more independence, when we can rely on each other.” She added, “I certainly appreciate how sharing childcare opportunities as a community gives me the freedom to garden. But we can’t forget that farming has always been a collective effort, of sharing seed and knowledge and work.”

The cooperative group’s views of social justice focused significantly on community outcomes and injustices as opposed to purely individual ones. This point about the urban group expressing something resembling a collectivist understanding of social justice came out especially clear in the qualitative interviews with members of the cooperative.

Among the members’ statements was one given by a man while he was erecting tomato cages with his two brothers, uncle and another man who 12 months prior was living in his home country of Costa Rica. Asked what social justice meant to him, he said, “Justice isn’t about charity; it’s about community empowerment; not about what you’re given but about intentionally realizing your aspirations collectively.”

Disagreements can lead to dialogue

The above images reflect disagreements, to be sure, and contextualize our inability to find common ground on such issues as climate change, guns and the social safety net. If one starts from the premise that an individual can only make good, right and just decisions when they’re left alone, then their position on those hot bottom issues will look a lot different from those who think individual freedom is enhanced when those liberties are balanced out by constraints determined by ideas about the collective good. In short, consensus is a stretch when one “side” preaches self-reliance and self-rule while the other speaks of “independence” and needing to “rely on each other” in the same sentence, as the mother from the cooperative did.

So what does this study of these two groups and their ideas mean? Does bridging the political divide in the U.S. mean groups like this need to settle all of their political disputes and arrive at consensus about everything?

Of course not. Disagreements are good when they encourage dialogue and debate.

What we have now in our country appears to sometimes border on combativeness if not outright hate, which has me deeply concerned, both as a sociologist and a citizen.

Before we can hope to repair the divides (plural, since these differences clearly go beyond rural-urban) we need to first understand how deep they cut. You wouldn’t prescribe a Band-Aid for a gash that requires stitches. The following are three concluding thoughts as we triage this wound.

Replace caricatures with actual encounters

First, the opposing worldviews illustrated in the word clouds have less to do with each group having different levels of knowledge and more to do with processing knowledge through very different filters. Thus, settling political disputes by arguing over “the facts” is futile, at least in some instances.

Second, a few respondents from each group appeared to be straddling “worlds.” People like this can be very helpful in bridging our political divides. Instead of building alliances based on geopolitical identities (e.g., ethnicity, political affiliation, rural/urban), we might explore how this process could start by engaging those who, like these few respondents, share similar worldviews.

Third, these worlds risk growing further apart the more their respective inhabitants look inward. The alternative would involve creating situations where we can get to know some of the people and livelihoods that are a world away from what we otherwise experience. That means the caricatures of rural and urban America need to be replaced with actual encounters.

Whoever thinks fences make for good neighbors has been infected by today’s political climate. What we need are bridges. It is time we start building them — and walking across the political divide.

Michael Carolan, Professor of Sociology and Associate Dean for Research & Graduate Affairs, College of Liberal Arts, Colorado State University

#MeToo in Antarctica

In this Jan. 24, 2015 photo, snow surrounds buildings used by Chile's scientists on Robert Island, part of the South Shetland Islands archipelago in Antarctica. Temperatures can range from above zero in the South Shetlands and Antarctic Peninsula to the unbearable frozen lands near the South Pole.(AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko) (Credit: AP)

At the end of October, in the thick of the #MeToo movement, I received a message written by five women. They were reaching out, as so many others were, to share their story.

A couple of weeks earlier, I had written about the prevalence of sexual harassment on scientific research trips to Antarctica. Jane Willenbring, a geologist who was physically and verbally abused by her advisor, finally reported him to Boston University after nearly 20 years of silence. That story, originally covered in Science, shed some light on sexual misconduct in the sciences.

As a counterexample, a sign that meaningful change was on the way, I pointed to Homeward Bound — an Australia-based leadership initiative for female scientists that aims to compile a network of 1,000 women leaders by 2026. Homeward Bound hopes that network will go on to influence future policies and, among other things, fight climate change.

For about a year, approximately 80 women from around the world get to know each other over online chats, coaching sessions, and working groups. Then, they all meet for a three-week-long voyage to Antarctica. Shift the leadership from male to female, goes Homeward Bound’s operational theory, and it will remove the barriers that women in science face — including unwanted advances, bullying at work, and a “boys’ club” atmosphere.

In a 2014 study, 71 percent of female scientists reported sexual harassment during field work; 26 percent revealed they’d been sexually assaulted. The American Geophysical Union recently classified “harassment, bullying, and discrimination” as scientific misconduct in its code of ethics. And earlier this month, the National Science Foundation reformed its policy, requiring grantee institutions to report when research leaders are accused of inappropriate behavior.

The women who wrote to me, all alumnae of Homeward Bound’s inaugural Antarctic voyage, alleged that, rather than working to remove barriers that stymie women scientists, the trip was plagued by them. They noted several instances of sexual harassment and bullying, and one participant alleged a disturbing episode of what she labeled “sexual coercion” at the hands of one of the ship’s crew. Much of that environment of hostility was perpetuated, they say, by Homeward Bound’s leadership and faculty.

Still, most of the women I spoke to have participated in efforts to reform the program to make it safer and better for the next voyage — which set sail ten days ago. They offered feedback through a formal review process, that 2016 alumna Deborah O’Connell, a research scientist with Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, helped lead. O’Connell, who was not part of the group that reached out to me, compared Homeward Bound’s need to iterate to her expertise: trying to devise interventions for climate change. She says that, when trying out new and bold experiments, scientists have to put in place “rapid-learning loops” to ensure they’re moving in the right direction.

“There were many things that needed to be improved about the program content and the way it was run,” O’Connell says, adding that participants and Homeward Bound leaders agreed on many elements that could be refined.

But the women who contacted me are not sure that, a little over a year on, Homeward Bound has changed enough to meaningfully contend with the systemic issues it’s trying to address. Furthermore, they feel they have been silenced for repeating their concerns. Their belief is that Homeward Bound is not yet a safe space for women, even as it works toward making science more inclusive of them.

A program with such noble aspirations has to navigate extremely fraught waters. When those are literal Antarctic waters, it’s even more challenging. As you read this, the second voyage of Homeward Bound could be moving closer to the example for conquering sexism in science that I initially held it out to be. Or it’s sailing toward being a cautionary tale of the complexities involved in toppling long-standing inequity.

“The idea for Homeward Bound came to me literally in a dream,” cofounder Fabian Dattner tells me over the phone in early February. She had envisioned a crowd of women on a ship, Antarctica in the background, and a film crew documenting the whole process.

A self-described social entrepreneur, Dattner is the cofounder of Dattner Grant, a leadership consultancy near Melbourne. She developed Homeward Bound with a marine ecologist in 2015. The modus operandi of the program is to equip women to become leaders via an intensive process of self-examination.

For the first 12 months of Homeward Bound, participants have sessions with coaches to discuss where they are as leaders and where they want to be. They then work in research groups of about six, delving into topics like climate change communications, climate and gender, and climate and health. At the program’s culmination, the women meet in the Argentine town of Ushuaia to board a ship to Antarctica. In 2018, the cost of participating in the program is $16,000.

In December 2016, the first Homeward Bound voyage set out with 76 women from eight countries. Also on board were about a dozen faculty members; around 40, primarily male, crew members (mostly from Argentina and Chile); as well as Australian and German expedition leaders.

December is often the warmest time of year to be in Antarctica, though warm for the bottom of the Earth is still freezing cold. The Homeward Bound journey in 2016 took two days to cross the Drake Passage — the body of water between South America and Antarctica — and participants spent time on the deck marveling at the icebergs and relatively calm sea.

Once reaching the southernmost continent, sunsets would “linger for hours,” alumna Sea Rotmann, a New Zealand-based energy and behavior change consultant, tells me. But the sky would never quite get dark — an ambience that people who have spent time at the planet’s poles characterize as emotionally and physically overwhelming.

It’s in part why Antarctic researchers typically undergo psychological evaluations before going into the field. “If psychologists want to study the combined effects of increased interpersonal stress and reduced opportunity for buffering and coping with that stress, here indeed is a natural laboratory,” notes a 1998 analysis of the psychological hazards at a polar research base.

During a typical day on the Homeward Bound trip — in-between field jaunts out onto the Antarctic ice — there were plenty of leadership strategy discussions and what could be described as guided introspection, which included personality tests and frank analyses of participants’ strengths and weaknesses. In the evenings, there was a lot of drinking on the vessel. The ship’s bar was the primary area to socialize and decompress after hours of intense self-reflection and ice-clambering.

“The outcome is emotional-cognitive — you’re able to change in your entirety, and the program was designed around that,” Dattner explains. “None of this will work if you’re not looking into the dark part of your soul.”

Homeward Bound has been forced to look into the dark part of its own soul over the past year.

On the night the ship docked back into Argentina, the program asked participants to critique the journey, noting what was worthwhile and what had failed. Grist has reviewed the compiled feedback.

The main criticisms were that there was little discussion of participants’ research, climate science, or gender inequity in science. Respondents saw the trip as a missed opportunity to converse about the challenges each saw for others in their industry. Furthermore, about a quarter of the women found the facilitators’ instructional style to be “confrontational.” Four whom I spoke with specifically noted a bullying dynamic in the leadership sessions.

In response, Dattner had to reevaluate her philosophy on creating leaders and, as a result, much of the program. She says that it was, at times, a painful process. But all of those reflections formed the basis for, among other things, a revised curriculum that focuses more on the systemic factors that keep so many women from attaining positions of leadership in science.

Eighteen alumnae sent a separate letter to Dattner and the faculty in April 2017. It requested that greater attention be paid to the safety and health of the women in the program.

“We should take every step possible to ensure the physical and mental health of participants and staff during the voyage and prior to embarkation,” they wrote, adding that they felt safety concerns could not be adequately addressed by Homeward Bound’s feedback process. They asked that the faculty and expedition leaders acknowledge the need to protect the participants traveling to Antarctica.

Several women on that voyage described to Grist an inappropriate dynamic with some crew members, who they allege placed bets on who they could sleep with, discussed whether women scientists would be “fuckable,” and according to one 2016 alumna, tried to get women into “compromising circumstances.” Multiple women noted their discomfort at having their names and corresponding room numbers visibly posted at the bar.

In their letter, the 18 women also wrote that leadership team members “womanhandled” the participants and pushed, pulled, or embraced them against their will. “Unsolicited physical contact by anyone — especially people in positions of authority — is unacceptable,” they wrote. They described instances of public humiliation at the hands of the leadership team — including publicly referencing one participant’s confidential sexual trauma and repeatedly calling out another who was critical of the program as a troublemaker. They even say they witnessed unacceptable objectification of crew members by Homeward Bound faculty.

A June 2017 response from Dattner and Homeward Bound thanks the 18 women for their feedback and lists the 63 changes that the program implemented based on its own review process. It does not acknowledge or respond to the allegations of harassment or humiliation.

“A safe space is needed when one is challenging oneself and exploring one’s inner self, especially when taking women in the middle of the Southern Ocean to do that,” one member of the group of 18 wrote to me via email. “I don’t think a leadership program like Homeward Bound can be successful unless it properly recognises and really listens to the diverse views and negative experiences of the participants, and importantly, takes care of their safety and well-being.”

Even if Homeward Bound starts listening, a 2016 alumna I’ll call Ashley (to protect her privacy) won’t be participating in its network of women leaders. The conditions on the Antarctic journey were particularly hard on her.

Ashley is an Australian environmental scientist, and found out about Homeward Bound through a colleague at the government organization she worked for in 2015. She craved an opportunity to meet other scientists and meaningfully discuss all the challenges they faced as women.

During the application process, she had endured sexual harassment at work. One of her older coworkers began sending her lewd texts detailing sexual acts he fantasized about her doing. She, along with two other women, reported his behavior. He vehemently denied any wrongdoing. After a drawn-out battle with her employer, she resigned.

Ashley, who is also a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, collapsed into a mental breakdown and was eventually diagnosed with PTSD. After being accepted into Homeward Bound, she emailed Dattner about her condition and her recent harassment experience, writing that there are “still small struggles I deal with on a day-to-day basis.”

Dattner was warm in her response. “I suspect this ship will be one of the safest, most thoughtful, responsible, kind, and supportive places any of us could be,” she replied. “I will personally be there for you when, how, and if you need me.” She reassured Ashley that multiple coaches would also be available on the ship to help her through any difficulties.

Ashley ended up facing a lot of them. She was anxious, depressed, and, contrary to Dattner’s assurances, found the program’s faculty unsupportive. At the Symposium at Sea — an event where all the women gave presentations on their scientific work — Ashley asked if she could focus her talk on the sexual harassment she had faced. She hoped to give other women the opportunity to discuss their own experiences.

“I said, ‘I don’t want to talk about my work,’” she recalls. “I want to talk about why I’m not going back to work, and I think that’s pretty important.”

A Homeward Bound spokesperson tells Grist they turned down Ashley’s request because there were participants on board who specifically demanded not to have a discussion about sexual misconduct at work because they feared having to relive their own experiences. It’s an apt encapsulation of a major rift in the #MeToo movement: While many women, like Ashley, find sharing their stories empowering, others want to avoid the subject altogetherto protect their mental health.

As she was feeling silenced by Homeward Bound’s leadership, Ashley was dealing with new, unwanted advances. A male crewmember had made his interest in her known, and at a raucous party on the ship, he offered her several drinks. She accepted them, even though she says she doesn’t normally indulge due to her own issues with alcohol. But she was feeling deeply anxious and depressed while on board the ship, and she recalls wanting to feel more comfortable.

As Ashley spent more and more time with the crewmember, she became confident that they could spend time together as friends. After all, she was engaged to be married and had no interest in romance.

One night, while she was drinking with the crewmember and another Homeward Bound participant, the crewmember asked one of his colleagues to call Ashley’s friend away to another part of the ship. As soon as the two were alone, he climbed on top of Ashley and started kissing her face and chest. She tried to block him.

For several nights, he called her room, asking to be let in. She did not report any of this behavior, she says. She mistrusted the faculty after the Symposium at Sea debacle, and she didn’t know which authority on the ship was best to report it to. And, perhaps above all, she felt too depressed to bother.

On the last night of the journey, after a lot of drinking and partying, Ashley woke up naked with the crewmember, having no memory of what had happened. Facebook messages from him after the fact confirm that they had sex, which she is sure she was in no condition to consent to.

She confessed all of this to Sea Rotmann on the plane back to Australia. But she never reported it to Fabian Dattner or anyone else. She simply wanted to be done with the program.

Every woman I spoke with from the 2016 Homeward Bound trip told me there were several instances of consensual sex on board.

“What happened in Antarctica stays in Antarctica,” Dattner told me. “Guess what, sex turns up. I don’t care what you do as long as you don’t hurt anyone.”

But someone was hurt. Experiences like Ashley’s are — as we’re learning through the media — extremely commonplace. The stories can be blurry and messy, which are frequently subject to question. That’s what makes them hard to report — particularly if you don’t trust the authority you would report to, which Ashley did not.

She has, however, directly confronted the crewmember about her experience, so he could learn from it. “I’ve explained to him that I would not have slept with him if I had not been so traumatized and triggered,” she tells me. “And that I was drunk, and that it wasn’t consensual, and that it wasn’t OK for him to keep going after me when I had told him no.”

Wynet Smith, a geographer based in Canada and one of the 18 women who signed the letter to Homeward Bound, says that none of the women on the ship were given any protocol by which to report incidents of misconduct — though she’s since discovered that was the domain of the ship’s captain. She, along with Sea Rotmann, has been in touch with the company that owns the ship to request that women on board the 2018 voyage are aware of that fact. (A Homeward Bound spokeswoman contradicts Smith’s account, saying the women on the 2016 trip received a safety briefing informing them to direct complaints to the ship captain.)

Dattner insists that any sexual misconduct claim on the 2016 journey, against the crew or otherwise, is completely unsubstantiated. Dattner and a Homeward Bound spokeswoman note there is no record of any transgression — which Ashley concedes. While there was no official complaint from the 2016 trip, the feedback compiled through the program’s review process does include references to both sexual harassment and Ashley’s experience.

According to Dattner, she has more than met the safety requirements based on feedback from the ship’s owners, the ship doctor, the faculty, and the alumnae network. In the additional letter, the 18 cosigners demanded that room numbers not be posted publicly — a request acknowledged in Dattner’s June 2017 response. And a new Homeward Bound code of conduct includes a section on how to report incidents of sexual misconduct.

The 18 women also recommended in their letter that Homeward Bound contract an independent clinical psychologist — who would be available to the women ahead of the trip and on board the ship — to help participants navigate the emotionally strenuous process of self-examination in a challenging environment. The program has hired Kerryn Velleman, an organizational psychologist who had worked as a coach with the 2016 cohort, to join this year’s voyage. (The alumnae I spoke with say that she does not meet their requirements because of her lack of clinical practice and her connection to Dattner.)

In an email to Grist, Velleman explains that Homeward Bound’s application process invites candidates to disclose their mental health history and allows the program’s leaders to assess the emotional preparedness of participants to take part in the program. Indeed, the program now requires that participants have their psychological fitness evaluated before embarking on the Antarctica trip.

“This is not a setting for the clinical resolution of human issues,” Dattner told me. “This is a leadership initiative. It’s really important that the women put themselves forward and self-assess: ‘I’m going to a remote location, I’m on an expedition and a leadership initiative: Do I feel resourceful about being in that position?’”

Ultimately, the fundamental disagreement between Homeward Bound’s leadership team and the women who continue to criticize the program comes down to this: What measures must be taken to create a “safe” space in which women will thrive, succeed, and transform themselves?

Sea Rotmann is perhaps the Homeward Bound participant most openly critical of the program. She believes that the leadership team has not approached the issue of safety with the appropriate gravity, and she’s alarmed that she, along with three other critics, were kicked out of the program’s Facebook group in December for continuing to express disillusionment. (A Homeward Bound spokesperson confirmed that two women were ejected from the Facebook group for behavior that undermined “the sense of safety in our online spaces” and distressed other group members.)

“In this so-called sisterhood of women science leaders, a program set up by women and for women, it seems you’re only welcome to speak out if it is in support of what some of them want to get out of it,” Rotmann wrote to me. “And to me, at least, that seems more perverse and insidious than some of the outright sexism and harassment that is happening to us all over the world.”

Over the course of multiple conversations, Rotmann tells me that despite her significant misgivings, she’s confident that the 2018 Homeward Bound voyage will be an improved experience. And she attributes that to the work that she and the other alumnae did to ensure they were heard by the leadership team.

One early report from the ship seems to indicate things have changed. Shortly after the 2018 voyage’s departure, Ashley received a Facebook message from the crewmember who pursued her. He told her that the crew had been warned against “fraternizing” with the women, and that this year’s voyage would be “boring” because of it. When Ashley reminded him that her experience was what pushed her to call for that warning, he was horrified and became defensive — despite the fact that she had already explained that to him.

Homeward Bound will continue to change and grow. In doing so, it has an opportunity to meaningfully address the ways in which sexual misconduct can infiltrate even the best-intended environments.

The goal of elevating more women into scientific leadership is certainly admirable, but it may not be enough to meaningfully address the problems that face women in the field. And Dattner emphasizes, in our conversation, that she does not presume to say Homeward Bound is single-handedly taking on sexual discrimination in science. She instead describes the program as “a small contribution to gender equity.”

If women are leading, Dattner tells me, “The world will become more equitable and kinder.”

But womanhood does not carry an inherent grace or wisdom or sense of caring or any other quality necessary for compassionate leadership. To address all the barriers that keep women from tearing down the boys’ club in science, not only do we need women who lead, but we need women who truly listen.

March 1, 2018

Ben Carson wants to cancel his office’s $31K furniture order

Ben Carson (Credit: AP/Matt Rourke)

Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson is requesting that a $31,561 order for tables and chairs for his office be canceled after the furniture’s steep price tag fell under public scrutiny.

“At the request of the Secretary, the agency is working to rescind the order for the dining room set,” HUD spokesman Raphael Williams told Politico Thursday.

Carson’s move follows the House committee’s request for documents related to the redecoration venture. The request also included a complaint filed last November by Helen Foster, a former senior HUD official, who claimed she was demoted for refusing a request to help Carson’s wife, Candy, spend more than the legally allowed $5,000 maximum on her husband’s office redecoration venture. Foster claims she received pushback for attempting to call attention to budget shortfalls totaling $10 million, and that she was ousted from her role by a Trump appointee. The complaint alleges that HUD had “violated laws protecting whistleblowers from reprisals.”

The news makes HUD the latest agency under President Trump to come under fire for a scandal stemming from senior officials abusing power and funds for personal benefit. The same pattern played out with Tom Price, the former secretary of Health and Human Services, who resigned after it was revealed he had made lavish personal trips on the taxpayer’s dime.

Taxpayer funds have also been misused by Environmental Protection Agency Chief Scott Pruitt, who like Price, also enjoys flying first class. Add Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to that list, too, as he faced criticism recently for pricey short-distance helicopter trips, one of which involved riding horses with Vice President Mike Pence.

Carson may not be roaming the skies on private jets, but he has remarkably expensive tastes in furniture, particularly for a man who is renowned for his ability to fall asleep anywhere.

“Grey’s Anatomy” star Jesse Williams discusses “Survivors Guide to Prison”

Jesse Williams (Credit: AP/Richard Shotwell)

In 2016 “Grey’s Anatomy” star Jesse Williams magnetized media attention to him after his acceptance speech upon winning BET’s Humanitarian Award. Williams is a lifelong activist, and in addition to playing Dr. Jackson Avery on the ABC hit drama, works on a number of passion projects related to racial and social justice.

But at the time of the speech, which hit in the heat of the Black Lives Matter movement, the country’s long festering racial divide had broken wide open. “What we’ve been doing is looking at the data and we know that police somehow manage to deescalate, disarm and not kill white people everyday,” Williams said. “So what’s going to happen is we are going to have equal rights and justice in our own country or we will restructure their function and ours.” At the time a petition started on Change.org, which went nowhere, demanded that ABC fire him.

Lots has transpired in the nearly two years since that moment, as we know, much of we’d describe as disheartening. But Williams has kept on pushing, creating projects with the production company he’s co-founded, farWord Inc., as well as serving on the advisory board of Sankofa, a social justice organization founded by Harry Belafonte.

It’s through Sankofa that Williams became a producer on Matthew Cooke’s latest work “Survivors Guide to Prison,” current available via video on demand services.

Cooke’s abrasive documentary style is not for the faint hearted, a truth distinct from the hardcore subject matter of “Survivors Guide.” The director favors a claws-out, rough edged approach to his subject matter reminiscent of skate rock or punk videos, designed to hold the viewer’s attention even as it threatens challenges the audience’s sensibilities.

How digestible the documentary’s presentation is depends on what an individual expects from non-fiction works. “Survivors Guide,” like Cooke’s 2012 entry “How to Make Money Selling Drugs,” defies the standard even-handed and didactic longform documentary presentation by adding a snarling, sweaty energy to every frame, setting quick smash-cuts of security camera footage of law enforcement confronting suspects edited to turntable scratching and roaring electric guitars. Reviews of “Survivors Guide” in both The Hollywood Reporter and Variety use the term “assaultive” to describe his filmmaking style.

Despite this, the information conveyed in “Survivors Guide” to prison is meant for all ages because the reason for the film’s existence is to hammer home the point that no American can fool himself or herself into thinking that they can never fall down the rabbit hole of our broken criminal justice system.

“For a lot of well-meaning, open-minded folks, regardless of age, there is a general willingness to understand that something’s wrong, but it kind of stops there when you’re not able to articulate who, why, what would need to change, and what is actually rigged about this system,” Williams observed. “It kind of stops you short at Thanksgiving dinner table. It stops you short when you’re trying to kind of have this verbal battle with somebody to talk about it, but you don’t have your ammunition, for lack of a better term.”

“Survivors Guide to Prison,” he added, is that means of making such data accessible and appealing. The film touches upon many of the same topics director Ava DuVernay explored in her Netflix documentary “13th,” framing its instructions on what to say and not to say, and what to do and not do, with a barrage damning statistics — starting with the mind-reeling estimate that 13 million Americans are arrested every year. And none of our states has use-of-force laws on the books that meet international standards.

Some of the data is well-known in our era of non-scripted reality entertainment about prison life: that American has the highest incarceration rate in the world, that it disproportionately targets the poor and people of color and metes out harsher punishments for blacks than it does for white who commit the same crimes, with black men receive on average a 20 percent longer sentence than a white man.

“Survivors Guide” also enumerates the ways that for-profit prisons exploit convict labor to benefit the bottom line of multinational corporations.

But its edgy presentation and its high-power roster of celebrities gravely listing off step by step directions of what to do in every frightening scenario starting with being stopped by a beat cop through trial, conviction, the appeal process and for the lucky few, re-acclimation into society, strikes the right tone of urgency while holding your attention.

The breadth of its participants is as impressive as its list of producers, which includes Salon Talks guest David Arquette, Adrian Grenier, Danny Trejo, Susan Sarandon, who also serves as a narrator, and Williams. Though the majority of the stars featured hail from the worlds of rock and hip-hop, including such luminaries as Ice-T and Chuck D, “Survivors Guide” also features the likes of Quincy Jones, Deepak Chopra, Patricia Arquette, Danny Glover and Cynthia Nixon, as well as commentary from Van Jones and Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow.”

And some of these stars dispense advice based on their personal experiences with the prison system, including Trejo, MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer and hip-hop artist Busta Rhymes.

Inclusion of such a wide range of personalities was done with the intent of ensuring that “Survivors Guide” speaks to every age, gender and income demographic possible. But Cooke doesn’t merely rely on star power to get the film’s message across.

Although the cases of two innocent men who were wrongfully imprisoned serve as its narrative backbone “Survivors Guide” notably touches upon other cases of wrongful convictions. In one of them, a woman went law enforcement for questioning about a case. One of her kids remembered that she reassured her children she’d be home for dinner, and didn’t actually come back to them for years.

In the main the stories of Bruce Lisker, who served 26 years, and Reggie Cole, imprisoned for 16, lead us through “Survivors Guide.” Lisker and the woman cited above are both white, by the way, examples of what hints at being an intentional ploy on the part of the producers and filmmakers to prove that our criminal justice system can ensnare anybody.

“I’m speaking for myself now,” Williams qualified, “but it’s generally harder for the white population to attach themselves to already loaded minority groups who they are already conditioned to believe that they’re kind of born with a couple strikes against them, and they’re very likely to already kind of be guilty of something. Blackness and brownness is often treated as an act of aggression.

“But when you have an older white woman or a young white guy who’s fairly articulate and he’s getting railroaded, then you can only imagine how bad it is for other folks,” he continued. “I think that some of that was certainly deliberate in choosing subjects that a wider audience could have some empathy for. That’s unfortunate that we need that. It’s unfortunate that sometimes you need a white protagonist for folks to find humanity in. But in this case, I saw a benefit to it.“

Cole, an African American, was pushed into the system as a teenager. The film implies he was named in a murder case by a criminal running a local prostitution house who gave Cole up to the cops despite his innocence. Lisker, meanwhile, was accused of murdering his mother.

Though their backgrounds were different, the economic circumstances leading to their convictions bear a number of similarities, starting with the fact that neither could afford bail or high-powered legal representation. And their stories only grow grimmer from there.

Part of the unspoken challenge in gaining attention and traction for “Survivors Guide” is overcoming our culture-wide tendency to presume that anyone caught up in our penal system deserves whatever horror they’re made to endure. This is part of the reason for the passionate media push Williams and other stars are lending to this project.

“There’s not new information coming out about this,” he said. “It’s just a warmed-up audience that is a little bit more receptive and able to consider that [information]. It sucks that we have to shove it down their throats for them to taste it, but that’s part of the process. All of this, all the information, the multitude of sides and perspectives, helps any group not be viewed as a monolith, or as some homogenous blob that just kind of is predisposed to certain behaviors.”

And though the workings of our justice system are as under attack as the rest of our democracy, Williams maintains his optimism about how the conversation has evolved over the last couple of years.

“We clearly have a consistent increase in folks of influence, and folks making themselves of influence, who are talking about what’s happening in around us,” Williams said. “. . . They’re participating in our society and seeking full citizenship, not only for themselves, but for others. There is, if we’re looking at a graph, it’s definitely going up and to the right, in terms of active citizen participation in the system. That feels very clear to me and that is a good thing now.”

He added, “Some people need to see a bunch of people on the dance floor. I always use that analogy. Some people need to see a lot of other people out there first and see if they survived it, see if they’re okay, see if they got judged, and see if they got dragged on the internet for speaking out on something. It’s a little bit of the wild, wild west out there and it takes a little bit of time.”

How to let girls take the lead in activism

Paola Gianturco and Alex Sangster, co-authors of "Wonder Girls: Changing Our World" (Credit: Courtesy of Paola Gianturco)

This January, Oprah Winfrey stood on the stage of the Golden Globes as she accepted her Cecil B. DeMille Lifetime Achievement Award and addressed all the girls watching: “…know that a new day is on the horizon!” Winfrey declared. “And when that new day finally dawns, it will be because of a lot of magnificent women, many of whom are right here in this room tonight, and some pretty phenomenal men, fighting hard to make sure that they become the leaders who take us to the time when nobody ever has to say ‘Me too’ again.”

It’s a wonderful promise, but for some young girls, “on the horizon” isn’t soon enough.

“The future is now.” Alex Sangster, my latest guest on “Inflection Point” told me. She’s the co-author of “Wonder Girls: Changing Our World,” a book documenting the work of 15 girl-led nonprofit groups in 13 countries. “We are what’s the future. And if we are the future then we are supposed to be creating change now.”

Have I mentioned that Sangster is twelve years old?

She and her grandmother, accomplished photojournalist Paola Gianturco, partnered to interview and photograph more than 100 girls, ages 10-18, who aren’t waiting for a new day to begin their activism: They are rolling up their sleeves and ushering in that new day right now.

These girls are taking on issues like sex trafficking, child marriage, girls’ access to education and feminine hygiene products, and poverty. One girl in the book even told Paola the story of a time she went undercover.

“I said ‘Do you consider yourself an activist?’” Paola told me in our interview. “She was 15 and she said ‘yes.’ And I said ‘Well tell me something that you’re proud of having accomplished.’ And she said ‘last week I led a sting operation against a sex trafficking ring from Dubai.’”

Most girls in the United States aren’t even aware sex trafficking exists. Alex told me that before working on “Wonder Girls,” that “I might have heard of some of these issues. Thought about them briefly and then just gone back to my normal day.”

“But now that I’ve actually met some of the people who face these issues every day I’ve made personal connections with them and I’ve humanized some of the most major issues that girls are facing around the world,” she said.

And their activism, Alex told me, inspired the activist in her, too.

“My perspective has definitely changed,” she said. “I want to do everything in my power to help their causes. I can’t exactly buy them a house, but I can sign a petition. I can donate time and I can bring awareness of their needs so other people with more resources — AKA money — can get involved also.”

As a mother, my first instinct is to protect my girls from the harsher realities and hardships of the world for as long as I can, so they can have a happy, magical childhood free of existential fear. But after hearing Alex’s story, I wonder: when we work so hard to preserve what we see as the innocence of childhood, are we actually holding our kids back from the courageous work they can be doing in this world?

Listen to my conversation with Paola Gianturco and Alex Sangster, co-authors of “Wonder Girls,” about what it looks like when we let girls lead on “Inflection Point,” found on Apple Podcasts, RadioPublic, Stitcher and NPROne.

Facebook just wants you to be happy. It’s not working

Mark Zuckerberg (Credit: Getty/Drew Angerer)

As the 3rd most viewed site on the entire internet, Facebook is a tremendously powerful company with the ability to affect what millions see and believe vis-a-vis their News Feed — the company’s name for the scrolling feed of posts, from users, brands or media outlets, that users see upon log in. Yet lately, the company has been under assault on multiple fronts. From politicians to media outlets, worried psychologists to cultural critics, the growing consensus is that Facebook is too powerful, too big, too prone to manipulation and too easy to propagandize. In reaction, Facebook has made some prominent changes to its News Feed’s underlying structure — their attempt to make users value their time more on Facebook, feel less like they’re dependent on the site for self-esteem boosts, and less manipulated by fake news.

Then today, they changed their minds.

“We constantly try out new features, design changes and ranking updates to understand how we can make Facebook better for everyone,” wrote Facebook’s Head of News Feed in a blog post. “Today, we’re ending one of those tests: the Explore Feed.”

The so-called “Explore Feed” was Facebook’s attempt to bifurcate its two primary functions: creeping on friends and family’s lives, and reading (sometimes fake, often sensationalist) news articles. Admittedly, it is kind of strange to blend these two things together. If a well-informed, newspaper-reading time traveler from the 1950s arrived in 2018, they would identify Facebook as neither magazine nor yearbook nor photo album nor television, but a strange hydra that blends all of those for the purpose of absorbing as much of its users’ time as possible.

Facebook likes being a hydra, but it wants the heads to be more obviously separable. As Facebook described it:

The Explore Feed was a trial response to consistent feedback we received from people over the past year who said they want to see more from friends and family in News Feed. The idea was to create a version of Facebook with two different News Feeds: one as a dedicated place with posts from friends and family and another as a dedicated place for posts from Pages.

Through the course of its history, Facebook has constantly rehashed and redesigned its news feed in an attempt to make more money (and dodge critics). Video ads generally make more money than still ads, which is partly why the site pivoted to video recently. Hence, a TV icon now beckons users of the mobile app, one of five prominently-featured buttons.

In the olden days, Facebook’s news feed was merely a reverse-chronological scrolling list of all the posts from all the things — people, brands, magazines, etc. — that said user followed. Then Facebook started to change it. And change it. And change it.

Eventually, the news feed became the aforementioned weird hydra, yet one that was algorithmically designed to keep people scrolling forever (and thus keep shareholders happy). Studies showed that people reacted more positively to videos and pictures than text; the company keeps quiet about precisely how its algorithms work, but marketers who have studied it believe that if one posts video or photos on Facebook, the site will show said image to more friends than if you were to post a text-only status update. (Buffer, a social media management company, has a fascinating overview of “what the Facebook algorithm loves” on their blog here.) You can imagine how this kind of feedback loop can affect culture at large, by valuing certain types of visual communication over others and rewarding us with self-esteem boosts in specific cases. It’s Pavlovian in the creepiest way.

What if I post a link to a magazine or news article? Reportedly, Facebook doesn’t show posts from publishers to as many of your friends. CEO Mark Zuckerberg claims this is because these posts “crowd out personal moments,” but it is also true that links to external sites generally mean that users will leave Facebook — which that’s bad for their bottom line.

And yet, magazines and newspapers became incredibly dependent on Facebook for revenue, as the site had the power to quickly change a given brand’s visibility overnight with a quick news feed algorithm change. Publishers came to alternately fear and become dependent on Facebook’s algorithmic whims — more evidence, critics content, of the site’s overwhelming power.

You can see the problem here. Facebook likes publishers and needs them to provide content; it’s essentially a curator. And it also needs users to post selfies and status updates; it curates their “content” too. The “Explore Feed” split up the two functions.

Oddly, it didn’t work. Per the aforementioned blog:

You gave us our answer: People don’t want two separate feeds. In surveys, people told us they were less satisfied with the posts they were seeing, and having two separate feeds didn’t actually help them connect more with friends and family.

[…] Separately, we’re also discontinuing the Explore Feed bookmark globally this week. Explore gave people a new feed of content to discover Pages and public figures they hadn’t previously followed. We concluded that Explore isn’t an effective way for people to discover new content on Facebook.

So, does that mean the beleaguered site is back to square one?

It’s important to put any of Facebook’s changes or behavior in context. This is a for-profit corporation, publicly traded: despite their rhetoric about “prioritiz[ing] meaningful social interactions,” the company cares about one thing and one thing only: money. It is constitutionally incapable of caring about anything else.

Moreover, some within the tech industry have suggested that Facebook’s problems are unsolvable. Jonathan Morgan, who runs a company that monitors disinformation, told the Washington Post, “Even if [Zuckerberg] says, ‘Resolve this right away,’ the problems are baked into the fundamentals of the platform […] It’s not like Mark Zuckerberg just comes to the floor, makes a command, and everything turns around. The changes are a real threat to the way that these people think about success at their jobs.”

From a financial and logistical standpoint, this makes sense: the site traffics in eyeballs — not facts, not dog photos. Its entire function is to encourage users to spend as much time on it as possible. In the end, its shareholders do not fundamentally care what you stare at — be it fake news or dog photos or videos — as long as you keep staring. As I’ve written before, it’s a lot like a sewage company in that sense: it doesn’t matter what kind of sewage flows through the pipes, as long as it keeps flowing. That’s how it makes money.

But Facebook brass understandably fear regulation of some sort: Trafficking in the kind of untruths that manipulate election outcomes aren’t the kinds of things that companies want to do to stay in politicians’ good graces in a democratic society. Ditto for getting users, particularly children and young adults, addicted to their services. Hence, it’s just a matter of time before the company announces another hare-brained, silver-bullet scheme, designed to please everyone — yet which will inevitably please no one.

Millennials hate Trump, eager to vote in midterms: poll

(Credit: Getty/Drew Angerer)

A new survey from Pew Research Center examining the generation gap in American politics shows that the majority of Millennials are, or lean Democratic; have significant interest in the 2018 midterm elections; and overwhelmingly disapprove of President Donald Trump.

Pew Research Center has labeled Millennials as those born between 1981 and 1996; Gen X as those born between 1965 and 1980; the Baby Boom generation as those born between 1946 and 1965, and the Silent Generation as those born between 1928 and 1945. People born after 1996 are considered “Post-Millennial.” Some market research agencies and media outlets have alternately deemed the generation after Millennials “iGeneration” or “Digital Natives,” though cultural litigation over their generational designation may take years to definitively settle. Recall that Millennials were, during the 1990s and into the 2000s, often called “Generation Y,” as a Newsweek story from 2000 attests.

Nearly half of Millennial registered voters — around 44 percent — describe themselves as independents, Pew Research Center found. “However, a majority of Millennials (59 percent) affiliate with the Democratic Party,” the report adds, noting that “just 32 percent identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP.” This is a sharp divergence from older generations whose political identification is more equal across partisan lines. Only the Silent Generation lean more Republican than Democrat.

Some hopeful news: “Millennials’ early interest in this year’s midterms is greater than for the past two congressional elections,” the survey reports. “This year, 62 percent of Millennial registered voters say they are looking forward to the midterms; at similar points in 2014 and 2010, fewer Millennials said they were looking forward to the elections (46 percent in 2014, 39 percent in 2010).”

Millennials’ party identification as discussed above generally reflects who they plan to vote for in the midterm elections later this year, with 62 percent of Millennials saying they’d vote for the Democrat in their district. While Pew Research Center says Millennial voters usually favor Democrats during midterms, they do so by wider margins this time around. For older generations, not much has changed from past midterms in terms of who they’d vote for or the amount of early interest in the elections.

When it comes to Trump, Millennials are disproportionately not happy with the president’s performance compared to older generations. Nearly two-thirds of Millennials (65 percent) disapprove and just 27 percent approve of his time in office. For Gen-Xers, Trump’s disapproval number drops to 57 percent; 51 percent of Boomers disapprove and 48 percent of the Silent generation disapprove.

Before Trump was elected president, there was a lot of talk about how Millennials were more liberal and progressive than past generations. While Hillary Clinton did win the Millennial vote, Trump still won about one-third of young voters, which was higher than pre-election polls and popular discourse suggested. So while this information from Pew Research Center — that young voters lean Democrat —doesn’t come off as particularly novel, with midterm elections on the horizon, it is unclear how the chips will fall.

Spotify goes public: Here’s everything you need to know

Daniel Ek, CEO of Spotify (Credit: Getty/Toru Yamanaka)

After ten years as a private company, Spotify announced Wednesday that it plans to go public, filing paperwork for a $1 billion initial public offering.

The Swedish start-up will begin trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker name “SPOT.” According to the company’s SEC filings, shares have traded as high as $132.50 on private markets, which would give the company a valuation over $23 billion as of Feb. 22.

“We set out to reimagine the music industry and to provide a better way for both artists and consumers to benefit from the digital transformation of the music industry,” the company said in its filing. “Spotify was founded on the belief that music is universal and that streaming is a more robust and seamless access model that benefits both artists and music fans.”

Here are the six biggest takeaways from Spotify’s SEC filings:

Spotify is bigger than Apple Music

Spotify is the apparent industry leader in the U.S. among streaming music services, with the company reporting 71 million paid subscribers and more than 159 million active users as of Dec. 31, 2017. Its closest competitor, Apple Music, trails far behind with 36 million paid subscribers, the Wall Street Journal reported last month. Amazon Prime Music, the third-largest digital music service, has 16 million subscribers, according to MIDiA research, a U.K.-based media and technology analysis company.

Although Spotify rules the industry when it comes to on-demand streaming music, it’s now beset with the same problem many public internet companies, including Snap – and until last quarter – Twitter, have faced before: a business model that doesn’t show a clear way to profitability. In addition, Spotify’s two biggest competitors – Apple Music and Amazon – can both afford to run music services without ever seeing a penny.

Spotify’s playlists constitute almost one-third of streams on the platform

Spotify says its playlists are extremely successful, as they have become a key discovery tool. According to its SEC filings, Spotify reported that its playlists account for approximately 31 percent of all consumption. In addition to being a source for users to find new artists and new music, Spotify says its playlists have become influential among labels, artists and managers, saying they’re “one of the primary tools” the industry relies on to promote artists and measure success.

The platform has editorially-curated playlists, like “Good Vibes” and “Rap Caviar,” as well as an algorithm that generates personalized playlists for users with titles such as “Discover Weekly,” “Daily Mix” and “Release Radar.”

Several artists agree that Spotify’s playlists carry tremendous influence. Nick Perloff-Giles, best known as Wingtip, a Los Angeles-based producer, has experienced this power first-hand. With more than 32 million streams on his breakout single “Rewind,” Perloff-Giles attributes the song’s virality to the streaming platform. In an interview with Salon, he says his success “was 100 percent thanks to Spotify.”

The producer released “Rewind” in September 2016, just several months after graduating from Columbia University. (He recorded and produced the song in his college dorm.) The single was added to Spotify’s “Young & Free” playlist, which has nearly one million followers. Despite having no name recognition at the time, Perloff-Giles logged more than one million streams in two weeks. One month later, the producer was getting messages from record labels, offers to play music festivals and tentative publishing deals, leading him to quit his marketing job to pursue music full-time.

Spotify plans to rival traditional radio

“We believe there is a large opportunity to grow users and gain market share from traditional terrestrial radio … With a more robust offering, more on-demand capabilities and access to personalized playlists, we believe Spotify offers users a significantly better alternative to linear broadcasting.”

Currently, Spotify offers a radio-streaming feature, “which grows and evolves along with a users’ taste and choices. Our radio feature uses algorithms that take a user’s chosen song or artist to create an online radio station.”

Spotify aims to extend its reach beyond music

The company said, “We are an audio first platform and have begun expanding into non-music content like podcasts. We hope to expand this offering over time to include other non-music content, such as spoken word and short form interstitial video.”

Matt FX Feldman, a celebrated DJ and record producer best known as the music supervisor of the hit Comedy Central show “Broad City,” agrees that Spotify is tremendously powerful, especially when it comes to musicians or music groups not under contract with a record label. “Spotify, as a platform, has been a massive help to independent artists … Anything that can increase that platform, anything that can create more opportunities, I’m down for,” he told Salon.

Spotify says it has “even bigger aspirations”

Daniel Ek, the co-founder, CEO and chairman of Spotify, said in the filing: “We envision a cultural platform where professional creators can break free of their medium’s constraints and where everyone can enjoy an immersive artistic experience that enables us to empathize with each other and to feel part of a greater whole. But to realize this vision, professional creators must be able to earn a fair living doing what they love, where monetization is at the core of a creative proposition and not an afterthought. We care deeply about our creators and our users and we believe Spotify is a win-win for both.”

Is Spotify too big to fail?

The company faces challenges to its business model, including fluctuations in the royalty rates it pays to music labels, publishers and songwriters, as well as general changes in music industry and law. (In January, the company was hit with a $1.6 billion copyright lawsuit over its failure to properly license thousands of songs before making them available to stream, including titles by Tom Petty, Neil Young and The Doors.) These problems are on top of the company’s bigger, more general problem of becoming profitable.

Nevertheless, streaming now accounts for more than half of the majors’ digital revenue, according to an industry survey by PwC, and Spotify dominates the streaming market with more than 159 million monthly users – and growing.

In preparation for going public, Spotify announced a licensing deal last April with Universal Music Group. The deal would allow some artists to restrict new albums to paying subscribers for the first two weeks of release, while letting free users listen to singles. In exchange for the paywall, Spotify may get a break on fees from Universal. The partners hope the paywall will further increase Spotify’s number of paid subscribers. As Spotify touts that already sky-high number, it seems as though the company is successfully attracting consumers willing to pay $10 a month.

Bloodthirsty John Bolton eager to kill North Koreans

John Bolton (Credit: Getty/Alex Wong)

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed penned Wednesday, John Bolton, the former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations during the George W. Bush administration, explained why he believes the U.S. must “act” on North Korea, and how military action could be justified legally.

For decades, neoconservative militarism has coursed through Washington’s veins; the idea that the United States must make aggressive military decisions, often unilaterally, in the international arena in order to preemptively thwart a perceived immediate threat, has become a norm.

That ideology is still prevalent today, as it is echoed throughout various mainstream media circles and often used as the driver of conversations on how the U.S. should deal with a nuclear-armed North Korea.

“The threat is imminent, and the case against pre-emption rests on the misinterpretation of a standard that derives from prenuclear, pre-ballistic-missile times,” Bolton wrote. “Given the gaps in U.S. intelligence about North Korea, we should not wait until the very last minute. That would risk striking after the North has deliverable nuclear weapons, a much more dangerous situation.”

Bolton added, “How long must America wait before it acts to eliminate that threat?” To which one might counter: How many times in the past has this logic been an accepted, bipartisan line of questioning? It is American exceptionalism at its worst: the historically problematic notion that America is an exceptional nation, and that it and only it, holds altruistic intentions that justify preemptive violence and widespread war casualties, e.g. the half a million dead in Iraq as a result of America’s attempt to bring “freedom” there.

Essentially, Bolton wants to launch an attack to take out the regime of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un; yet like many hawkish intervention plans of the past, Bolton fails to establish what that attack should be, and what it would actually accomplish in the long term besides killing thousands or millions of Koreans. Among the pertinent questions Bolton hasn’t considered: what happens after the U.S. decimates a regime managing a country with 25 million people? A country that also borders the powerful U.S. foreign adversary, China?

These might be important considerations given that only in the past two decades, the U.S. has had similarly mixed results in its imperial ambitions. See also: the invasion and occupation of Iraq, the ousting of Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, etc.

The idea of Trump launching a preemptive strike has been derided by experts as a likely awful decision that has loads of unforeseen ramifications.

Bolton, who is now a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and also a commentator for Fox News, went on to argue that a strike on North Korea would pass the “necessity” test as described by 19th century American politician Daniel Webster.

Bolton elaborated:

British forces in 1837 invaded U.S. territory to destroy the steamboat Caroline, which Canadian rebels had used to transport weapons into Ontario.

Webster asserted that Britain failed to show that “the necessity of self-defense was instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation.” Pre-emption opponents would argue that Britain should have waited until the Caroline reached Canada before attacking.

Would an American strike today against North Korea’s nuclear-weapons program violate Webster’s necessity test? Clearly not. Necessity in the nuclear and ballistic-missile age is simply different than in the age of steam.

[…]

This is how we should think today about the threat of nuclear warheads delivered by ballistic missiles. In 1837 Britain unleashed pre-emptive “fire and fury” against a wooden steamboat. It is perfectly legitimate for the United States to respond to the current “necessity” posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons by striking first

The argument comes after President Donald Trump’s administration surprisingly announced that, after a year of escalated tensions between the U.S. and North Korea, diplomacy may be a smart decision. Evidently, Bolton is pushing back against the administration.

Yet this point of view is dangerous and short-sighted, and while intervention may not exactly be a new trick in American foreign policy, this form of aggression towards a nuclear-armed nation certainly makes things more unique. Consider that we have Trump at the helm of the military — a man who has promised to rain down “fire and fury” on the country of North Korea — and the U.S. could easily find itself in yet another perpetual war, or worse, a nuclear war that threatens all life on the planet.

A larger role for midwives could improve deficient U.S. care for mothers and babies

(Credit: Getty/NataliaDeriabina)

In Great Britain, midwives deliver half of all babies, including Kate Middleton’s first two children, Prince George and Princess Charlotte. In Sweden, Norway and France, midwives oversee most expectant and new mothers, enabling obstetricians to concentrate on high-risk births. In Canada and New Zealand, midwives are so highly valued that they’re brought in to manage complex cases that need special attention.

All of those countries have much lower rates of maternal and infant mortalitythan the U.S. Here, severe maternal complications have more than doubled in the past 20 years. Shortages of maternity care have reached critical levels: Nearly half of U.S. counties don’t have a single practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, and in rural areas, the number of hospitals offering obstetric services has fallen more than 16 percent since 2004. Nevertheless, thanks in part to opposition from doctors and hospitals, midwives are far less prevalent in the U.S. than in other affluent countries, attending around 10 percent of births, and the extent to which they can legally participate in patient care varies widely from one state to the next.

Now a groundbreaking study, the first systematic look at what midwives can and can’t do in the states where they practice, offers new evidence that empowering them could significantly boost maternal and infant health. The five-year effort by researchers in Canada and the U.S., published Wednesday, found that states that have done the most to integrate midwives into their health care systems, including Washington, New Mexico and Oregon, have some of the best outcomes for mothers and babies. Conversely, states with some of the most restrictive midwife laws and practices — including Alabama, Ohio and Mississippi — tend to do significantly worse on key indicators of maternal and neonatal well-being.

“We have been able to establish that midwifery care is strongly associated with lower interventions, cost-effectiveness and improved outcomes,” said lead researcher Saraswathi Vedam, an associate professor of midwifery who heads the Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia.

Many of the states characterized by poor health outcomes and hostility to midwives also have large black populations, raising the possibility that greater use of midwives could reduce racial disparities in maternity care. Black mothers are three to four times more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth than their white counterparts; black babies are 49 percent more likely to be born prematurely and twice as likely to perish before their first birthdays.

“In communities that are most at risk for adverse outcomes, increased access to midwives who can work as part of the health care system may improve both outcomes and the mothers’ experience,” Vedam said.

That’s because of the midwifery model, which emphasizes community-based care, close relationships between providers and patients, prenatal and postpartum wellness, and avoiding unnecessary interventions that can spiral into dangerous complications, said Jennie Joseph, a British-trained midwife who runs Commonsense Childbirth, a Florida birthing center and maternal care nonprofit. “It’s a model that somewhat mitigates the impact of any systemic racial bias. You listen. You’re compassionate. There’s such a depth of racism that’s intermingled with [medical] systems. If you’re practicing in [the midwifery] model you’re mitigating this without even realizing it.”

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE, analyzes hundreds of laws and regulations in 50 states and the District of Columbia — things like the settings where midwives are allowed to work, whether they can provide the full scope of pregnancy- and childbirth-related care, how much autonomy they have to make decisions without a doctor’s supervision, and whether they can prescribe medication, receive insurance reimbursement or obtain hospital privileges. Then researchers overlaid state data on nine maternal and infant health indicators, including rates of cesarean sections, premature births, breastfeeding and neonatal deaths. (Maternal deaths and severe complications were not included because data is unreliable.)

The differences between state laws can be stark. In Washington, which has some of the highest rankings on measures such as C-sections, premature births, infant mortality and breastfeeding, midwives don’t need nursing degrees to be licensed. They often collaborate closely with OB-GYNs, and can generally transfer care to hospitals smoothly when risks to the mother or baby emerge. They sit on the state’s perinatal advisory committee, are actively involved in shaping health policy and receive Medicaid reimbursement even for home births.

At the other end of the spectrum, North Carolina not only requires midwives to be registered nurses, but it also requires them to have a physician sign off on their application to the state for approval to practice. North Carolina scores considerably worse than Washington on indices such as low-birthweight babies and neonatal deaths.

Neel Shah, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a leader in the movement to reduce unnecessary C-sections, praised the study as “a remarkable paper — novel, ambitious, and provocative.” He said licensed midwives could be used to solve shortages of maternity care that disproportionately affect rural and low-income mothers, many of them women of color. “Growing our workforce, including both midwives and obstetricians, and then ensuring we have a regulatory environment that facilitates integrated, team-based care are key parts of the solution,” he said.

To be sure, many other factors influence maternal and infant outcomes in the states, including access to preventive care and Medicaid; rates of chronic disease such as diabetes and high blood pressure; and prevalence of opioid addiction. And the study doesn’t conclude that more access to midwives directly leads to better outcomes, or vice versa. Indeed, South Dakota, which ranks third from the bottom in terms of midwife-friendliness, scores well on such key indicators as C-sections and preterm births. Even North Carolina is average on C-section rates, breastfeeding and prematurity.

The findings are unlikely to quell the controversies over home births, which are almost always handled by midwives and comprise a tiny but growing percentage of deliveries in the U.S., or fears among doctors and hospitals that closer collaborations with midwives will raise malpractice insurance rates. In fact, said Ann Geisler, who runs the Florida-based Southern Cross Insurance Solutions, which specializes in insuring midwives, her clients’ premiums tend to be just one-tenth of premiums for an OB-GYN because their model of care eschews unnecessary interventions or technology. Far from being medical renegades, the vast majority of midwives want to be integrated into the medical system, she said.

Generally, licensed midwives only treat low-risk women, Geisler said. If the patients become higher risk, midwives are supposed to transfer them to a doctor’s care. Since many OB-GYNs only see midwife patients when a problem emerges, they may develop negative views of midwives’ skills, she said.

The benefits of midwifery come as no surprise to maternal health advocates. In 2014, the medical journal Lancet concluded that integrating midwives into health care systems could prevent more than 80 percent of maternal and newborn deaths worldwide — in low-resource countries that lack doctors and hospitals, by filling dangerous gaps in obstetric services; in high-resource countries, by preventing overuse of medical technologies such as unnecessary C-sections that can lead to severe complications. A review by the Cochrane group, an international consortium that examines research to establish best practices in medical care, found that midwives are associated with lower rates of episiotomies, births involving instruments such as forceps and miscarriages.

While widely accepted in Europe, midwives in the U.S. have been at the center of a long-running culture war that encompasses gender, race, class, economic competition, professional and personal autonomy, risk versus safety, and philosophical differences about birth itself.