Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 132

March 19, 2018

Trump and the exit of T-Rex

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (Credit: AP/Jacquelyn Martin)

The firing of the U.S. Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, by President Trump was hardly a surprise. Still, even after 14 months of Trump’s presidency, the “public execution” style of Tillerson’s departure has shocked even the most hardened observers.

The firing of the U.S. Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, by President Trump was hardly a surprise. Still, even after 14 months of Trump’s presidency, the “public execution” style of Tillerson’s departure has shocked even the most hardened observers.

After all, the position of Secretary of State is the most senior position in the U.S. cabinet. The Secretary of State is fourth in the line of succession in the U.S. presidential system, following the Vice President, the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate.

One would normally expect that the departure of a Secretary of State would occur with the deference becoming that position.

Instead, Tillerson — in his own words — received a call from the President and the Chief-of-Staff four hours after the President tweeted his decision. When the Under Secretary of State, Steve Goldstein, had referenced this unparalleled sequence of events earlier in the day, he too was summarily fired by the White House.

Not a star of international relations

Not that Rex Tillerson was a star in the orbit of international relations. His relationship to State Department staff was fractious. Several sources reported that staff was told not to make eye-contact with Tillerson should they happen to encounter him. Hardly a motivating piece of advice — or one that would encourage two-way communication.

Tillerson also took little initiative to protect the State Department from the debilitating budget cuts promoted by the Commander-in-Chief. Trump considers diplomacy generally a waste of time, unless America’s counterparties submit to all of his demands (zero-sum game, 2.0).

Nor does it appear that Tillerson did much to plead with the President to fill the plethora of ambassadorial or departmental openings.

Tillerson himself had publicly stated that he only took the job because his wife had urged him. His curriculum vitae was hardly a recommendation for this immense challenge, unless one considers being an oil-industry executive to be a good fit (cynically, it might be, given U.S. foreign policy priorities).

Standing up to Trump

But as a former CEO of ExxonMobil, one of the largest U.S. corporations, Tillerson brought something to the cabinet table that many of the other Trump followers did not: Independence and a sense of entitlement to get it his way that so often — sadly — defines successful corporate leaders.

As such, Tillerson made no effort to hide his disagreements with Trump. He was even said to have privately called the President a “moron.”

Tillerson voiced support for the Paris Climate Accord, the Iran nuclear deal and his opposition to Trump’s decision to move the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem and the recent one to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum.

It is no secret that Trump expects undying loyalty from those around him. He has shown little inclination to reward competence over constant public statements from his cabinet members, who must declare their complete and unfettered adoration for the leader. In that sense, his forthcoming meeting with Kim Jung-Un will be a meeting of the minds.

Cabinet members swear an oath that says that they “will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic,” that they “will bear true faith and allegiance to the same,” that they “take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion” and that they “will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which” they are “about to enter.”

Trump’s obsession with loyalty

Yet, in Trump’s mind, the entire oath is an oath of loyalty to him, personally. The former Director of the FBI, James Comey, learned this the hard way when he did not oblige Trump’s verbal request to assure him of such loyalty. He too was soon fired, especially since Comey did not suppress the Russia investigation as Trump had asked of him. Clearly, the ultimate betrayal.

This is where Mike Pompeo, currently CIA Director, comes in. Trump justified Pompeo’s nomination not so much with his qualification for the job but with the fact that he and Pompeo were “always on the same wave length.” Pompeo is a harsh critic of the Iran-deal, a climate-change denier and did not oppose steel and aluminum tariffs as Tillerson did.

As a true Tea Partier, he is against abortion even in cases of rape or incest. Among many other colorful statements, Pompeo has suggested that Edward Snowden should be sentenced to death.

After his almost assured confirmation, Pompeo will join the by-now almost unanimous voices of yes-men (and a couple of women) in the President’s cabinet. An evolution that led the President to elate after the Pompeo announcement: “We’re getting very close to the cabinet I want.”

The statement is at the same time frightening, while an unwitting admission of utter incompetence after 14 months on the job.

Dangerous for the world

All of this will leave the President ever-freer to act on his own, often scary, uninformed and crowd-pleasing instincts, cheered on by what can only be defined as a puppet cabinet. Naturally, this is dangerous for the United States, but more importantly dangerous for the world.

At a point in time when Trump’s domestic standing is becoming increasingly embattled and isolated, this raises the risk of wag-the-dog foreign policy actions by the United States.

Far beyond constantly seeking to disrupt the Mueller investigation, Trump is evidently also inclined to distract the domestic public any way he can. This may involve “wars of choice” — the magnitude of which could very well be unprecedented since 1945.

Nebraskans who support and oppose “religious freedom” laws actually share many of the same values

(Credit: Getty/dbvirago)

Religious freedom legislation highlights political division in the U.S., pitting conservative Christians against LGBTQ people and their allies.

As sociologists who study sexuality and conservative Christianity in the U.S., we decided to investigate whether and why people support or oppose these religious freedom laws with our co-author, Mathew Stange. Our study, forthcoming in Socius, asks specifically about laws that protect business owners who refuse to serve gays or lesbians. This is the focus of the ongoing Supreme Court case Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. The case will decide the legality of a wedding cake baker’s refusal to make a cake for a same-sex couple.

In our recently published study of over a 1,000 Nebraskans, we found that a clear majority of respondents, 64 percent, oppose laws that allow business owners to deny services to gay men or lesbians based on religious beliefs. Our poll, like national ones, found that these laws do not reflect broad support.

Why, then, do these bills continue to pass in state legislatures if most Americans do not actually agree with them?

Based on our research, we argue that one factor is that people on both sides of the issue rely on appeals to the American values of rights, freedom and capitalism to justify their position.

Rights and equality

One shared rationale among respondents on both sides is the idea that Americans have a fundamental right to freely live their lives.

People who oppose religious freedom laws emphasized an individual’s right to be free from discrimination. Many drew parallels to discrimination on the basis of race, arguing, as one respondent did: “Businesses discriminating against LGBT people is no different than half a century ago when businesses discriminated against blacks. Supporting civil rights means everyone gets to sit at the lunch counter.”

On the other side, people who support religious freedom laws focused on the freedom and rights of business owners. Many referenced the slogan “No shirts, no shoes, no service,” indicating that business owners can refuse service for a number of reasons. Some supporters explicitly talked about religious freedom. One respondent said an “owner of business should be able to conduct business in accordance with his religious convictions — to be true to himself.”

We found that both sides stressed the importance of freedom and rights, but had different ideas about whose rights were most important.

The free market

Both sides also drew on the significance of the free market and capitalism. When justifying their opinions, people on both sides pointed to an economy of abundant choices and to businesses weighing the potential risks and rewards in terms of profit.

People who support religious freedom legislation believe that there are many businesses willing to serve gays and lesbians. One person explained, “The issue is not denial of service, it is exercise of conscience. The ‘services’ are readily available elsewhere.”

People who oppose religious freedom legislation emphasized that businesses should be concerned with profit above all else. They made statements like: “the idea of business is to make money. To refuse a money making transaction is stupid” and “as a business owner, you don’t turn away business.” Both sides value capitalism and the free market, but had different ideas about whose actions mattered.

Nebraska compared to the nation

Even though this sample from Nebraska doesn’t represent national attitudes, it is an important case study to learn about how people make sense of religious freedom legislation targeting gays and lesbians. Nebraska is more politically conservative than the national average. However, the state is comparable to the rest of the nation when it comes to attitudes about LGBTQ rights and fairly average when it comes to religiosity.

White evangelical Christians, who often lead efforts to pass religious liberty legislation and who are more likely to support it than other religious groups, make up about 25 percent of the population in Nebraska and the country.

At stake in debates over religious freedom is who deserves protection from the government. Our study shows that opponents to these laws believe gays and lesbians have rights in need of protection. Supporters of religious freedom bills believe the rights of religious people, conservative Christian business owners more specifically, are potentially threatened in an era of increasingly greater acceptance of gay and lesbian visibility and relationships.

Yet LGBTQ people are arguably the underdog: Whereas the First Amendment makes illegal attempts to fire or refuse housing for someone based on religion — Christian or otherwise — it is legal in 28 states, including Nebraska, to fire a person or refuse housing to someone based on sexuality or gender nonconformity. The logic surrounding debates over “religious freedom” muddies what these bills codify into law under the guise of shared values about rights, equality and the free market.

Emily Kazyak, Associate Professor of Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Kelsy Burke, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

March 18, 2018

Optimize your data by mastering Google Analytics

Google Analytics is a tool that any marketer should master — it’s the key to breaking down your digital campaigns and optimizing your web traffic, so you can start figuring out what you need to do to convert your visitors into sales. Whether you’re experienced with the tool or just starting out, the Google Analytics Masterclass: Lifetime Access gives you valuable strategies to help you build more successful campaigns.

This comprehensive bundle includes seven modules that you can access 24/7, whether you need a refresher or to get walked through some foundational skill sets again. This course shows you how to measure sales and conversions and understand basic features like the Google Analytics dashboard, shortcuts, alerts and standard reports.

Once you have a solid understanding of the basics, the course dives into the various report types, from traffic acquisitions to site search reports. Once you understand how your users found your website and what pages drive the most engagement, you can start to refine your sales funnel and target your messaging towards what drives the most sales.

Best of all, you can learn at your own pace, rewinding, repeating or fast-forwarding through the lectures as you choose. Usually, the Google Analytics Masterclass retails for $334, but you can get it now for $19, or 94% off. For a limited time, you can use coupon code: MADMARCH10 for an extra 10% off the sale price.

This weighted blanket helps reduce stress and anxiety

Sleep is one of the most overlooked aspects to our overall health and wellness — and while there are starting to be more and more apps and hardware all oriented around giving us a more soothing rest, sometimes we fail to look at less technologically advanced, but just as effective options for a better night’s sleep. This Gravis Weighted Blanket works to alleviate stress and anxiety, helping you enjoy a more soothing rest.

Made from high-quality cotton and weighted with glass pellets, this blanket could be your way to a better night’s sleep — no need for fancy diffusers, expensive apps or prescriptions. It weighs 20 pounds and provides an in-home deep-pressure feel (think of the same pressure you’d get during a gentle massage) that will help you relax.

Plus, it’s machine-washable, so you don’t need to worry about maintenance. Usually, this Gravis Weighted Blanket is $259.99, but you can get it now for $207.99. For a limited time, use coupon code: MADMARCH10 for an extra 10% off the sale price.

When it comes to immigration, it’s time to put common sense into policy

(Credit: Christopher Millette/Erie Times-News via AP)

The immigration debate seems to have gone crazy.

President Obama’s widely popular Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, which offered some 750,000 young immigrants brought to the United States as children a temporary reprieve from deportation, is ending… except it isn’t… except it is… President Trump claims to support it but ordered its halt, while both Republicans and Democrats insist that they want to preserve it and blame each other for its impending demise. (Meanwhile, the Supreme Court recently stepped in to allow DACA recipients to renew their status at least for now.)

On a single day in mid-February, the Senate rejected no less than four immigration bills. These ranged from a narrow proposal to punish sanctuary cities that placed limits on local police collaboration with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials to major overhauls of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act that established the current system of immigration quotas (with preferences for “family reunification”).

And add in one more thing: virtually everyone in the political sphere is now tailoring his or her pronouncements and votes to political opportunism rather than the real issues at hand.

Politicians and commentators who once denounced “illegal immigration,” insisting that people “do it the right way,” are now advocating stripping legal status from many who possess it and drastically cutting even legalized immigration. These days, the hearts of conservative Republicans, otherwise promoting programs for plutocrats, are bleeding for low-wage workers whose livelihoods, they claim (quite incorrectly), are being undermined by competition from immigrants. Meanwhile, Chicago Democrat Luis Gutiérrez — a rare, reliably pro-immigrant voice in Congress — recently swore that, when it came to Trump’s much-touted wall on the Mexican border, he was ready to “take a bucket, take bricks, and start building it myself… We will dirty our hands in order for the Dreamers to have a clean future in America.”

While in Gutiérrez’s neck of the woods, favoring Dreamers may seem politically expedient, giving in to Trump’s wall would result in far more than just dirty hands, buckets, and bricks, and the congressman knows that quite well. The significant fortifications already in place on the U.S.-Mexican border have already contributed to the deaths of thousands of migrants, to the increasing militarization of the region, to a dramatic rise of paramilitary drug- and human-smuggling gangs, and to a rise in violent lawlessness on both sides of the border. Add to that a 2,000-mile concrete wall or some combination of walls, fences, bolstered border patrols, and the latest in technology and you’re not just talking about some benign waste of money in return for hanging on to the DACA kids.

In the swirl of all this, the demands of immigrant rights organizations for a “clean Dream Act” that would genuinely protect DACA recipients without giving in to Trump’s many anti-immigration demands have come to seem increasingly unrealistic. No matter that they hold the only morally coherent position in town — and a broadly popular one nationally as well — DACA’s congressional backers seem to have already conceded defeat.

Good Guys and Bad Guys

It won’t surprise you, I’m sure, to learn that Donald Trump portrays the world in a strikingly black-and-white way when it comes to immigration (and so much else). He emphasizes the violent criminal nature of immigrants and the undocumented, repeatedly highlighting and falsely generalizing from relatively rare cases in which one of them committed a violent crime like the San Francisco killing of Kate Steinle. His sweeping references to “foreign bad guys” and “shithole countries” suggest that he applies the same set of judgments to the international arena.

Under Trump’s auspices, the agency in charge of applying the law to immigrants, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, has taken the concept of criminality to new heights in order to justify expanded priorities for deportation. Now, an actual criminal conviction is no longer necessary. An individual with “pending criminal charges” or simply a “known gang member” has also become an ICE “priority.” In other words, a fear-inspiring accusation or even rumor is all that’s needed to deem an immigrant a “criminal.”

And such attitudes are making their way ever deeper into this society. I’ve seen it at Salem State University, the college where I teach. In a recent memo explaining why he opposes giving the school sanctuary-campus status, the chief of campus police insisted that his force must remain authorized to report students to ICE when there are cases of “bad actors… street gang participation… drug trafficking… even absent a warrant or other judicial order.” In other words, due process be damned, the police, any police, can determine guilt as they wish.

And this tendency toward such a Trumpian Manichaean worldview, now being used to justify the growth of what can only be called an incipient police state, is so strong that it’s even infiltrated the thinking of some of the president’s immigration opponents. Take “chain migration,” an obscure concept previously used mainly by sociologists and historians to describe nineteenth and twentieth century global migration patterns. The president has, of course, made it his epithet du jour.

Because the president spoke of “chain migration” in such a derogatory way, anti-Trump liberals immediately assumed that the phrase was inherently insulting. MSNBC correspondent Joy Reid typically charged that “the president is saying that the only bill he will approve of must end what they call ‘chain migration’ which is actually a term we in the media should just not use! Because quite frankly it’s not a real thing, it’s a made up term… [and] so offensive! It’s shocking to me that we’re just adopting it wholesale because [White House adviser] Stephen Miller wants to call it that… [The term should be] family migration.”

Similarly, New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand claimed that “when someone uses the phrase chain migration… it is intentional in trying to demonize families, literally trying to demonize families, and make it a racist slur.” House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi agreed: “Look what they’re doing with family unification, making up a fake name, chain. Chain, they like the word ‘chain.’ That sends tremors through people.”

But chain migration is not the same as family reunification. Chain migration is a term used by academics to explain how people tended to migrate from their home communities using pre-existing networks. Examples would include the great migration of African Americans from the rural south to the urban north and west, the migrations of rural Appalachians to Midwestern industrial cities, waves of European migration to the United States at the turn of the last century, as well as contemporary migration from Latin America and Asia.

A single individual or a small group, possibly recruited through a state-sponsored system or by an employer, or simply knowing of employment opportunities in a particular area, sometimes making use of a new rail line or steamship or air route, would venture forth, opening up new horizons. Once in a new region or land, such immigrants directly or indirectly recruited friends, acquaintances, and family members. Soon enough, there were growing links — hence that “chain” — between the original rural or urban communities where such people lived and distant cities. Financial remittances began to flow back; return migration (or simply visits to the old homeland) took place; letters about the new world arrived; and sometimes new technologies solidified ongoing ties, impelling yet more streams of migrants. That’s the chain in chain migration and, despite the president and his supporters, there’s nothing offensive about it.

Family reunification, on the other hand, was a specific part of this country’s 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which imposed quotas globally. These were then distributed through a priority system that privileged the close relatives of immigrants who had already become permanent residents or U.S. citizens. Family reunification opened paths for those who had family members in the United States (though in countries where the urge to migrate was high, the waiting list could be decades long). In the process, however, it made legal migration virtually impossible for those without such ties. There was no “line” for them to wait in. Like DACA and Temporary Protected Status (TPS), the two programs that President Trump is now working so assiduously to dismantle, family reunification has been beneficial to those in a position to take advantage of it, even if it excluded far more people than it helped.

Why does this matter? As a start, at a moment when political posturing and “fake news” are becoming the norm, it’s important that the immigrant rights movement remain accurate and on solid ground in its arguments. (Indeed, the anti-immigrant right has been quick to gloatover Democrats condemning a term they had been perfectly happy to use in the past.) In addition, it’s crucial not to be swept away by Trump’s Manichaean view of the world when it comes to immigration. Legally, family reunification was never an open-arms policy. It was always a key component in a system of quotas meant to limit, control, and police migration, often in stringent ways. It was part of a system built to exclude at least as much as include. There may be good reasons to defend the family reunification provisions of the 1965 Act, just as there are good reasons to defend DACA — but that does not mean that a deeply problematic status quo should be glorified.

Racism and the Immigrant “Threat”

Those very quotas and family-reunification policies served to “illegalize” most Mexican migration to the United States. That, in turn, created the basis not just for militarizing the police and the border, but for what anthropologist Leo Chávez has called the “Latino threat narrative”: the notion that the United States somehow faces an existential threat from Mexican and other Latino immigrants.

So President Trump has drawn on a long legacy here, even if in a particularly invidious fashion. The narrative evolved over time in ways that sought to downplay its explicitly racial nature. Popular commentators railed against “illegal” immigrants, while lauding those who “do it the right way.” The threat narrative, for instance, lurked at the very heart of the immigration policies of the Obama administration. President Obama regularly hailed exceptional Latino and other immigrants, even as the criminalization, mass incarceration, and deportation of so many were, if anything, being ramped up. Criminalization provided a “color-blind” cover as the president separatedundocumented immigrants into two distinct groups: “felons” and “families.” In those years, so many commentators postured on the side of those they defined as the deserving exceptions, while adding further fuel to the threat narrative.

President Trump has held onto a version of this ostensibly color-blind and exceptionalist narrative, while loudly proclaiming himself “the least racist person” anyone might ever run into and praising DACA recipients as “good, educated, and accomplished young people.” But the racist nature of his anti-immigrant extremism and his invocations of the “threat” have gone well beyond Obama’s programs. In his attack on legal immigration, chain migration, and legal statuses like DACA and TPS, race has again reared its head explicitly.

Unless they were to come from “countries like Norway” or have some special “merit,” Trump seems to believe that immigrants should essentially all be illegalized, prohibited, or expelled. Some of his earliest policy moves like his attacks on refugees and his travel ban were aimed precisely at those who would otherwise fall into a legal category, those who had “followed the rules,” “waited in line,” “registered with the government,” or “paid taxes,” including refugees, DACA kids, and TPS recipients — all of them people already in the system and approved for entry or residence.

As ICE spokespeople remind us when asked to comment on particularly egregious examples of the arbitrary detention and deportation of long-term residents, President Trump has rescinded the Obama-era “priority enforcement” program that emphasized the apprehension and deportation of people with criminal records and recent border-crossers. Now, “no category of removable aliens [is] exempt from enforcement.” While President Trump has continued to verbally support the Dreamers, his main goal in doing so has clearly been to use them as a bargaining chip in obtaining his dramatically restrictionist priorities from a reluctant Congress.

The U.S. Customs and Immigration Service (USCIS) made the new restrictionist turn official in late February when it revised its mission statement to delete this singular line: “USCIS secures America’s promise as a nation of immigrants.” No longer. Instead, we are now told, the agency “administers the nation’s lawful immigration system, safeguarding its integrity and promise… while protecting Americans, securing the homeland, and honoring our values.”

Challenging the Restrictionist Agenda

Many immigrant rights organizations have fought hard against the criminalization narrative that distinguishes the Dreamers from other categories of immigrants. Mainstream and Democrat-affiliated organizations have, however, generally pulled the other way, emphasizing the “innocence” of those young people who were brought here “through no fault of their own.”

Dreamers, TPS recipients, refugees, and even those granted priority under the family reunification policy have all operated as exceptions to what has long been a far broader restrictionist immigration agenda. Trump has now taken that agenda in remarkably extreme directions. So fighting to protect such exceptional categories makes sense, given the millions who have benefited from them, but no one should imagine that America’s policies have ever been generous or open.

Regarding refugees, for example, the State Department website still suggeststhat “the United States is proud of its history of welcoming immigrants and refugees… The U.S. refugee resettlement program reflects the United States’ highest values and aspirations to compassion, generosity, and leadership.” Even before Trump entered the Oval Office, this wasn’t actually true: the refugee resettlement program has always been both small and highly politicized. For example, out of approximately seven million Syrian refugeeswho fled the complex set of conflicts in their country since 2011 — conflicts that would not have unfolded as they did without the American invasion of Iraq — the United States has accepted only 21,000. Now, however, the fight to preserve even such numbers looks like a losing rearguard battle.

Given that a truly just reform of the country’s immigration system is inconceivable at the moment, it makes sense that those concerned with immigrant rights concentrate on areas where egregious need or popular sympathy have made stopgap measures realistic. The problem is that, over the years, this approach has tended to separate out particular groups of immigrants from the larger narrative and so failed to challenge the underlying racial and criminalizing animus toward all those immigrants consigned to the depths of the economic system and systematically denied the right of belonging.

In a sense, President Trump is correct: there really isn’t a way to draw a hard and fast line between legal and illegal immigration or between the felons and the families. Many immigrants live in mixed-status households, including those whose presence has been authorized in different ways or not authorized at all. And most of those felons, often convicted of recently criminalized, immigration-related or other minor violations, have families, too.

Trump and his followers, of course, want just about all immigrants to be criminalized and excluded or deported because, in one way or another, they consider them dangers to the rest of us. While political realism demands that battles be fought for the rights of particular groups of immigrants, it’s no less important to challenge the looming narrative of immigrant criminalization and to refuse to assume that the larger war has already been lost. In the end, isn’t it time to challenge the notion that people in general, and immigrants in particular, can be easily divided into deserving good guys and undeserving bad guys?

Aviva Chomsky is professor of history and coordinator of Latin American studies at Salem State University in Massachusetts and a TomDispatchregular . Her most recent book is Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal .

A promising backup to the honeybee is shut down

(Credit: AP Photo/Ted S. Warren, File)

The almond industry contributes an estimated $21 billion annually to California’s economy and it is completely dependent on honeybees for its existence. For eight years the Wonderful Company, the world’s largest almond grower, had been funding a large research project to breed another commercial pollinator — Osmia lignaria, aka the blue orchard bee, or BOB — to help the beleaguered honeybee in their vast orchards. Researchers and growers worldwide were keeping a close eye on the program’s progress. But in February 2018, right when a new generation of BOBs was to fly into the orchards, Wonderful canceled the program. Why? And what does this mean for the vital pollinator business?

Blue orchard bees are premier pollinators of early-blooming fruit trees like almonds. Several hundred female BOBs can do the work of a hive that contains 10,000 honeybees. BOBs are completely different kinds of bees, so they are managed differently. One of the key problems inhibiting their widespread use has been the inability of breeders to propagate large numbers of them.

In the mid-2000s, when honeybees were really struggling, several companies started propagating blue orchard bees inside large, netted production cages. Chief among them was Paramount Farming, which was renamed Wonderful Orchards in 2015. Joe MacIlvaine was president of Paramount at the time and says he wanted to pursue an alternative bee because it made him nervous that the honeybees were “our sole means of support.”

Since 2009 Wonderful’s BOB project had been run by Director of Bee Biology Gordon Wardell. Cracking the propagation problem was a primary focus. His goal was to raise one million female BOBs inside 20 acres of netted cages, and it seemed Wonderful was on the cusp of success. Wardell had hoped he might reach that goal in 2018, although admittedly he had hoped for that in 2017 as well.

Given that, the February announcement seemed sudden. (Indeed, Scientific American had just published a detailed article about the program.) Managers at Wonderful declined to be interviewed for this article, and Wardell was not available for comment. But when asked why the company decided to discontinue the program right as the BOB season was about to begin, Mark Carmel, director of corporate communications, replied in a written statement, “We’ve determined that continuation of the program is not financially feasible. In addition, we were unable to consistently achieve the level of female replication needed to make the program successful.”

Fortunately, Wonderful’s bees will not die with the project. Jim Watts of Watts Solitary Bees has purchased them. The research will not be shelved, either. Wonderful Orchards allowed a variety of U.S. Department of Agriculture and university scientists to conduct their own BOB research there. Bill Kemp, who recently retired from the USDA and had worked with the BOBs for years, wrote in an e-mail that Wonderful’s massive project showed “it was possible to mass produce Osmia lignaria at a scale thought previously unimaginable.”

What may happen to the BOB industry, now that such a big player has pulled out? The consensus among the scientists and industry workers contacted for this article is that the pursuit of BOBs as a viable alternative pollinator will continue. Even though the million-female goal had not been reached, “the proof of concept is there,” says Theresa Pitts-Singer, who works at the USDA Bee Biology and Systematics Laboratory and has studied BOBs for years.

Watts notes, “I think Wonderful has figured it out. Five years ago it was complicated, but they’ve shown the path.” Pitts-Singer says Wonderful’s withdrawal “might negatively impact confidence in the supply of these bees, but the fact that it can happen is now known.” She adds, interest in the bees is strong and says, “the industry has moved forward enough — both in in-orchard propagation and other attempts at mass production — that [progress] will continue, but the pace might be a little slower.”

Meanwhile, in Wonderful’s vast almond orchards, the honeybees will have to do the job alone.

OSHA: Georgia Goodyear plant lapses put employees at serious risk

(Credit: AP Photo/Tony Dejak)

A Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. plant in Georgia faces about $70,000 in fines for failing to follow federal workplace safety laws that endangered workers.

A Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. plant in Georgia faces about $70,000 in fines for failing to follow federal workplace safety laws that endangered workers.

Investigators from the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration imposed seven serious citations against the company in January after inspecting its plant last year in Social Circle, Georgia. Federal officials found the company failed to provide proper protective gear to workers processing rubber through hot metal presses withtemperatures exceeding 350 degrees Fahrenheit. They also discovered hazards from unguarded machines, rainwater and leaking equipment that put workers at risk of slipping on the production floor.

“Our inspection found multiple safety deficiencies that put employees at risk of serious injury or death,” William Fulcher, the OSHA area office director in Atlanta, said in a statement. “Potential workplace hazards must be assessed and eliminated to ensure employees are afforded a safe work environment.”

Goodyear has contested the fines, according to an OSHA spokesman.

Laura Duda, a Goodyear spokeswoman, wrote in an email that the company “cooperated with OSHA during its inspection and are now following the standard administrative process for responding to citations. We can’t discuss specifics while this is in progress.”

Similar safety issues were uncovered in an investigation by Reveal in December that showed how Goodyear’s lax approach to safety contributed to the deaths of motorists on the road and workers in its plants. The tire giant ranked among the top five manufacturers in the United States for worker deaths since 2009, according to Reveal’s analysis. In addition, at least four motorists over the last seven years have died in accidents after tires made at Goodyear plants failed.

Those tires were manufactured in plants where intense production demands and leaks in the roof have endangered both workers and consumers, Reveal’s investigation found. Court documents and former workers in the company’s plants in Danville, Virginia, and Fayetteville, North Carolina, detailed how water leaked through the roof and in some cases onto machines. Workers are trained to avoid moisture in tireproduction because it can prompt treads to separate, causing a blowout.

In interviews, several former employees of Goodyear’s Danville and Fayetteville plants said they felt pressure to put production before workplace safety. Some recalled a quota-driven motto invoked on the shop floor: “Round and black and out the back.”

Hours after Reveal’s investigation was published on Revealnews.org and, via The Associated Press, on the websites of The Washington Post, The New York Times and ABC News, a Goodyear spokeswoman issued a statement.

“Over the past two years, we fell short of our own expectations for safety, and we mourn the loss of valued coworkers at two of our U.S. manufacturing plants,” Barbara Hatala, Goodyear’s communications manager for the Americas Operations, said in the statement. “This is unacceptable.”

The story detailed how protections for factory workers are being dismantled. The Trump administration has rolled back and postponed Obama-era protections in keeping with goals laid out by the National Association of Manufacturers. Richard Kramer, Goodyear’s chairman, chief executive officer and president, serves on the association’s board.

Since October 2008, Goodyear has been fined more than $1.9 million for more than 200 health and workplace safety violations, far more than its four major competitors combined. Besides the most recent proposed OSHA fines of $69,058, the company’s plant in Social Circle, Georgia, has been previously cited for three workplace safety violations, two of them serious.

The most recent fines are “deeply discouraging,” said Jordan Barab, the former deputy assistant secretary of OSHA under Obama.

“Even with multiple preventable deaths and serious injuries in plants across the country, and multiple OSHA citations, Goodyear never seems to learn a very basic lesson: that they are legally and morally required to provide safe workplaces for their employees,” Barab said.

Jennifer Gollan can be reached at jgollan@revealnews.org. Follow her on Twitter: 슠@jennifergollan .

How people talk now holds clues about human migration centuries ago

(Credit: Getty/Geber86)

Often, you can tell where someone grew up by the way they speak.

For example, if someone in the United States doesn’t pronounce the final “r” at the end of “car,” you might think they are from the Boston area, based on sometimes exaggerated stereotypes about American accents and dialects, such as “Pahk the cahr in Hahvahd Yahd.”

Linguists go deeper than the stereotypes, though. They’ve used large-scale surveys to map out many features of dialects. The more you know about how a person pronounces certain words, the more likely you’ll be able to pinpoint where they are from. For instance, linguists know that dropping the “r” sounds at the end of words is actually common in many English dialects; they can map in space and time how r-dropping is widespread in the London area and has become increasingly common in England over the years.

In a recent study, we applied this concept to a different question: the formation of Creole languages. As a linguist and a biologist who studies cultural evolution, we wanted to see how much information we could glean from a snapshot of how a language exists at one moment in time. Working with linguist Hubert Devonish and psychologist Ewart Thomas, could we figure out the language “ingredients” that went into a Creole language, and where these “ingredients” originally came from?

Mixing languages to make a Creole

When a Creole language forms, it’s generally because two or more populations come together without a common language to speak. Across history, this was often in the context of colonialism, indentured servitude and slavery. For example, in the U.S., Louisiana Creole was formed by speakers of French and several African languages in the French slave colony of Louisiana. As people mix, a new language forms, and often the origins of individual words can be traced back to one of the source languages.

Our idea was that, if specific dialects were common among the migrants, the way they pronounce words might influence the pronunciations in the new Creole language. In other words, if English-derived words in a Creole exhibit r-dropping, we might hypothesize that the English speakers present when the Creole formed also dropped their r’s.

Following this logic, we examined the pronunciation of Sranan, an English-based Creole still spoken in Suriname. We wanted to see if we could use language clues to identify where in England the original settlers came from. Sranan developed around the mid-17th century, due to contact between speakers of English dialects from England, migrants from elsewhere in Europe (such as Portugal and the Netherlands) and enslaved Africans who spoke a variety of West African languages.

As is the case with most English-based Creoles, the majority of the lexicon is English. Unlike most English Creoles, though, Sranan represents a linguistic fossil of the early colonial English that went into its development. In 1667, soon after Sranan was formed, the English ceded Suriname to the Dutch, and most English speakers moved elsewhere. So the indentured servants and other migrants from England had a brief but strong influence on Sranan.

Using historical records to check our work

We asked whether we could use features of Sranan to hypothesize where the English settlers originated and then corroborate these hypotheses via historical records.

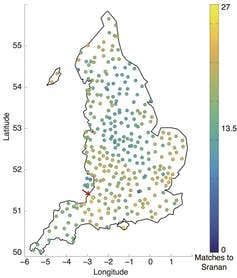

The similarity of each English dialect to Sranan. The most similar dialect, Blagdon, is indicated by a red arrow.

source, CC BY-ND

First, we compared a set of linguistic features of modern-day Sranan with those of English as spoken in 313 localities across England. We focused on things like the production of “r” sounds after vowels and “h” sounds at the start of words. Since some aspects of English dialects have changed over the last few centuries, we also consulted historical accounts of both English and Sranan.

It turned out that 80 percent of the English features in Sranan could be traced back to regional dialectal features from two distinct locations within England: a cluster of locations near the port of Bristol and a cluster near Essex, in eastern England.

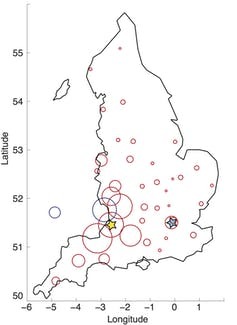

Circles represent the origin locations listed in ship records. The area of the circle is proportional to the number of individuals from that location. Bristol is marked by a yellow star, London by a blue star.

source, CC BY-ND

Then, we examined archival records such as the Bristol Register of Servants to Foreign Plantations to see if the language clues we’d identified were backed up by historical evidence of migration. Indeed, these boat records indicate that indentured servants departing for English colonies were predominantly from the regions identified by our language analysis.

Our research was proof of concept that we could use modern information to learn more about the linguistic features that went into the formation of a Creole language. We can gain confidence in our conclusions because the historical record backed them up. Language can be a solid clue about the origins and history of human migrations.

We hope to use a similar approach to examine the African languages that have influenced Creole languages, since much less is known about the origins of enslaved people than the European indentured servants. Analyses like these might help us retrace aspects of forced migrations via the slave trade and paint a more complete linguistic picture of Creole formations.

Nicole Creanza, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University and André Ché Sherriah, Postdoctoral Associate in Linguistics, University of the West Indies, Mona Campus

Why don’t Americans care about chemicals?

In this photo taken Oct. 9, 2014, body products on display at a Whole Foods in Washington. Theres a strict set of standards for organic foods. But the rules are looser for household cleaners, textiles, cosmetics and the organic dry cleaners down the street. Wander through the grocery store and check out the shelves where some detergents, hand lotions and clothing proclaim organic bona fides. Absent an Agriculture Department seal or certification, there are few ways to tell if those organic claims are bogus. Some retailers, like Whole Foods, have stepped in with their own requirements for what can be labeled organic. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh) (Credit: AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

For the past four years, researchers at Chapman University in Orange, CA have surveyed Americans to determine what we fear most. Polled at random, people were asked to rate their level of fear of about 80 different topics, including crime, terrorism, the government, environmental pollution, and personal fears.

For the past four years, researchers at Chapman University in Orange, CA have surveyed Americans to determine what we fear most. Polled at random, people were asked to rate their level of fear of about 80 different topics, including crime, terrorism, the government, environmental pollution, and personal fears.

For the first time in 2017, environmental fears ranked with Americans’ top 10 greatest fears: “pollution of oceans, rivers, and lakes,” “pollution of drinking water,” “global warming/climate change,” and “air pollution” all jumped into the top 10. They bumped perennial fears, about the economy, government, and terrorism, further down the list.

Increased concern about environmental pollution should not necessarily surprise us. In 2017, the Trump administration supported a market shift in US environmental policy and enforcement. That change has brought new attention to an old fact: we’ve created a whopping number and volume of chemicals over the years for use in industry and public health, somewhere around 140,000 formulations since 1950. Many of these chemicals can leach into the environment and into living creatures.

Although relatively few chemical pollutants are thought to be harmful to human health, only a paltry 2 percent or so of extant chemicals have been well-vetted for safety and toxicity by the US Environmental Protection Agency. We’re learning more every day about these significant levels of ambient contaminant exposure in the US, bringing this sort of pollution more into public awareness.

Though comparatively few in number, harmful synthetic chemicals can wreak havoc on public health around the globe. In 2015, an estimated 16 percent of all premature global deaths were caused by pollution and pollution-related disease, more than 15 times the number caused by war and all forms of violence combined. Ninety-two percent of these pollution-related deaths were in low- or middle-income countries, mostly related to air pollution. In the US, roughly 200,000 premature deaths each year are attributed to air pollution from combustion processes, like ground transportation and fossil fuel power.

Compelling evidence also suggests these chemicals impair the immune system and vaccine effectiveness, child brain development and learning ability, human fertility, weight loss, social behavior, cancer, and a slew of other diseases. You don’t need to work in a chemical plant for high exposure: we encounter pollutants in everyday activities, in concentrations that have been demonstrated to be impactful, in the here and now of normal life.

A chemical Catch-22

Looking at these figures and facts, something seems amiss. We rely on power plants and manmade chemicals every day, and they are supposed to better our lives, not cut them short. But here we are, caught in a chemical Catch-22: some of these same chemicals we count on — for energy, medicine, food, technology — can harm us and wildlife when they’re let loose, as they inevitably are.

Why do we allow chemicals to slip into our lives and bodies? Because it’s largely legal, at least in the US. Unlike more protective rules in Europe, chemical policy in the US errs away from the precautionary principle, which states that given two courses of action, with incomplete knowledge of the consequences, the more cautious approach should be followed. Under the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act(TSCA) and a 2016 update of the law, the burden generally falls on scientists to prove chemicals are harmful, to humans or the environment, before regulators intervene; chemicals are assumed safe until proven guilty.

The dangers of new chemicals are evaluated according to new and existing rules that critics argue have been substantially weakened by the current administration; proponents argue that new emphasis on speedy chemical approval is good for business and still protective of public health, collecting increased fees from manufacturers to defray TSCA implementation costs. Regardless of individual TSCA opinion, the overall jump-first, think-later approach can be costly — in terms of health, lives, and money — yet the public has yet to demand significant revisions to chemical regulations in the US.

Working in contaminant research, I wrestle with our relationship to chemicals every day. I recognize how important modern chemicals are for public health and safety. Yet at the same time, I see environmental contaminants behind cancer in my loved ones, in snake-oil ads for new miracle products, or when a friend tells me over the phone that she just can’t conceive. On most days, these realities motivate me to keep working, to find ways to measure and understand pollutants — to learn more so that we might better understand or regulate the chemical cocktail all around us.

But on bad days, I feel confused and frustrated and a little alone. Why is it so difficult for us to care about toxicants all around us, despite such dire consequences for ourselves and the people we love?

‘Apocalypse fatigue’

Over the last two decades, psychologists have hypothesized that we respond — or don’t — to faceless threats like climate change according to the way those threats are framed in contrast to the status quo. Economists, policy experts, and journalists have expounded on an outcome of this type of thinking, suggesting several terms to describe the phenomena: “threat fatigue,” “resistance fatigue,” and “apocalypse fatigue” all roughly mean the same thing — that we tire out from constant threats that challenge our modus operandi and thus don’t take any of them seriously enough.

Per Espen Stoknes, a Norwegian psychologist and economist, suggests five mental defenses that stifle public engagement with the climate change: distance, doom, dissonance, denial, and identity. In a nutshell, we often see climate change as apocalyptic but far off, at odds with our accepted lifestyles. So we often deny our role in it or refuse to act, unwilling to confront what it means for our habits and identity.

People keep falling ill, sometimes fatally, as research struggles to catch up

If you listen to Stoknes’ TED talk on the subject, you can substitute “synthetic chemical risk” almost everywhere he discusses climate change. Both are faceless, seem distant, and ostensibly require action outside of our routines: the same psychological and cultural barriers seem to influence how we see pollutants, and to neuter public concern and action. We may know that chemicals are all around us and may affect our health, but it seems like a minor threat, or one that is out of our hands, a danger beyond the actionable capabilities of any one person. These paralyzing assumptions mean chemicals keep getting introduced with little vetting. And people keep falling ill, sometimes fatally, as research struggles to catch up to how chemicals contribute to disease.

Where does this leave us?

The same solutions that encourage action on climate change may also help raise appropriate concern for chemical exposure. Stoknes suggests five approaches, readily transferable to our dilemma: discussing the issue in ways that make the threat personal; framing the issue in concrete ways — jobs, safety, etc — rather than global doomsday tidings; providing simple actions to make a difference; and finding better stories to break through denial or polarization.

Several organizations and many scientists are working on these goals already. Last winter, the journal PLOS released a special collection, “Challenges in Environmental Health: Closing the Gap between Evidence and Regulations,” in which a cast of experts filled the collection with short, easily understandable perspectives and essays.

The collection touched on the shortcomings of current law, what goes into our food, how toxicants affect children, how we can better protect drinking water, and a recent policy decision not to ban a pesticide. Each piece framed contaminant topics in terms of public health, policy, and solutions, going a step beyond sterile observations of most peer-reviewed articles. While the opinions were mostly of a kind, the expansive, interdisciplinary approach was both refreshing and riveting. Looking ahead, such holistic thinking is likely what’s required from everyone.

Chemical regulation still faces resistance in the US. Even the collection’s editor, Linda Birnbaum, the director of the National Institute of Environmental Health and Safety, was demonized by politicians who accused her of lobbying in her introduction. It can feel disheartening, but other, similarly accomplished scientists have started to speak out, too, including Joseph Allen from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Richard Corsi from University of Texas. There are even new smartphone apps to better gauge individual exposure potential.

These figures set an example for how to discuss chemicals conversationally and to suggest consumer solutions with policy ones: we should try to tell better and more accurate stories, and to have an open mind. The results of the Chapman University study, indicating Americans today worry about environmental pollution, underscores the increasing effectiveness of more and better storytelling about pollution.

I personally have witnessed a sea change in my own loved ones over the past few years; my mom and dad, far from environmentalists, now try to buy organic foods and tell others about chemical safety. Engaging in these sorts of honest conversations about chemical pollution benefits us all, and will hopefully create fair solutions that support public health, the environment, and the economy.

March 17, 2018

Patients overpay for prescriptions 23% of the time, analysis shows

(Credit: AP Photo/Toby Talbot)

[UPDATED at 12:40 p.m. ET on March 13]

As a health economist, Karen Van Nuys had heard that it’s sometimes cheaper to pay cash at the pharmacy counter than to put down your insurance card and pay a copay.

So one day, she asked her pharmacist how much her prescription would cost if she didn’t use her health coverage and paid cash.

“And sure enough, it was [several dollars] below my copay,” Van Nuys said.

Van Nuys and her colleagues at the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics decided to launch a first-of-its-kind study to see how often this happens. They found that customers overpaid for their prescriptions 23 percent of the time, with an average overpayment of $7.69 on those transactions.

The USC study, released Tuesday, analyzed the prices that 1.6 million people paid for 9.5 million prescriptions in the first half of 2013, based on data from Optum Clinformatics, an organization that sells anonymized claims data for analysis, and National Average Retail Price (NARP) data, which contained drug prices paid by insurers and was based on a national survey of pharmacists.

It showed that the overpayments totaled $135 million during that six-month period.

The practice of charging a copay that is higher than the full cost of a drug is called a “clawback” because the middlemen that handle drug claims for insurance companies essentially “claw back” the extra dollars from the pharmacy. (The middlemen, known as pharmacy benefits managers, include Express Scripts, CVS Caremark and OptumRx.)

Here’s how it works: After taking your insurance card, your pharmacist says you owe a $10 copay, which you pay, assuming that the drug costs more than $10 and your insurance is covering the rest. But unbeknownst to you, the drug actually cost only $7, and the PBM claws back the extra $3. Had you paid out-of-pocket, you would have gotten a better deal.

Until Van Nuys and her colleagues went digging, no one knew how common the practice was.

“Clearly this is going on [at a] much higher frequency than most people imagine,” said Geoffrey Joyce, who directs health policy at the center and was a coauthor on the study. “You’re penalizing people for having insurance.”

(Story continues below.)

The findings cover only a small portion of the population over a short time span, so they might not be perfectly reflective of what’s going on nationally, Joyce said. But they debunk the perception that clawbacks are rare.

Steve Hoffart, who owns Magnolia Pharmacy, an independent compounding and retail pharmacy in Magnolia, Texas, said clawbacks are still happening — even though Texas legislators passed a law to prohibit them. Hoffart said he collects and sends $1,100 or $1,200 a month in clawbacks to the PBMs.

The National Community Pharmacists Association, of which Hoffart is a member, said the new research “is illustrative of just one of many ways that PBMs’ lack of transparency disadvantages pharmacy patients. … If you want to reduce prescription drug costs, policymakers must demand greater transparency from PBMs.”

The trade group for the PBMs, the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, said that overall the PBMs bring down the total cost of prescription drugs, lowering costs for patients and insurers.

“We support the patient paying the lowest price available at the pharmacy counter,” the group said in a statement.

The USC researchers found that brand-name drugs had the highest clawbacks — an average overpayment of $13.46 per prescription. Clawbacks on generic drugs were $7.32, on average. The drug with the most frequent clawbacks was zolpidem tartrate — generic Ambien, a drug used to treat insomnia.

Although the research team was able to obtain copay data, it didn’t have data on what the PBMs paid for the drugs, said Van Nuys, the lead study author and executive director of the Schaeffer Center’s life sciences innovation project. As a stand-in, the reserachers used the National Average Retail Price data, which existed for a short period in 2013. They included clawbacks only of $2 or more.

Sometimes, the clawbacks are stunning. The day before Hoffart testified in favor of Texas’s new anti-clawback law, a patient was charged a $42.60 copay for a generic version of simvastatin, a statin drug. The patient could have paid $18.59 out-of-pocket, and the clawback was $39.64, Hoffart said, adding that the clawback made him lose money on the transaction.

Patients often aren’t told they could pay less without using insurance unless they ask.

“If they don’t ask, they’re not going to get the information they need,” Hoffart noted.

But even then, some insurance plans prohibit pharmacists from telling patients due to gag clauses. Six states have prohibited the gag clauses and 20 more are considering similar legislation, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.