Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 1015

August 17, 2015

Paul Krugman: GOP candidates promise government by the 1 percent, for the 1 percent

Donald Trump is a professional wrestler: How the billionaire body-slammed GOP politics

* * *

In his seminal essay on professional wrestling, Roland Barthes took special attention to performance of the heel archetype, which he describes as the "bastard," about which he wrote the following:Each sign in wrestling is [...] endowed with an absolute clarity, since one must always understand everything on the spot. As soon as the adversaries are in the ring, the public is overwhelmed with the obviousness of the roles. As in the theatre, each physical type expresses to excess the part which has been assigned to the contestant. Thauvin, a fifty-year-old with an obese and sagging body, whose type of asexual hideousness always inspires feminine nicknames, displays in his flesh the characters of baseness, for his part is to represent what, in the classical concept of the salaud, the 'bastard' (the key-concept of any wrestling-match), appears as organically repugnant. The nausea voluntarily provoked by Thauvin shows therefore a very extended use of signs: not only is ugliness used here in order to signify baseness, but in addition ugliness is wholly gathered into a particularly repulsive quality of matter: the pallid collapse of dead flesh (the public calls Thauvin la barbaque, 'stinking meat'), so that the passionate condemnation of the crowd no longer stems from its judgment, but instead from the very depth of its humours. It will thereafter let itself be frenetically embroiled in an idea of Thauvin which will conform entirely with this physical origin: his actions will perfectly correspond to the essential viscosity of his personage.The ultimate goal of a successful professional wrestler is to elicit an emotional response from the audience. Heels want to be booed and hated. Faces want approval and cheers. They are both masters of manipulation and psychology, taking the audience on an emotional journey of highs and lows. However, as the storytelling formula of professional wrestling has morphed over time, it has expanded to include antiheroes and other characters who do not fit neatly into a simple binary of good or bad. (These figures are sometimes called "tweeners.") Heroes can sometimes act like bullies, straining our allegiance. And villains who consistently entertain crowds can come to command more respect and admiration than their benevolent counterparts, even in spite of behavior that could be characterized, from a normative standpoint, as contemptible. What happens then, when the villain, because of their charisma, speaking ability, physical talent, or some intangible becomes popular with wrestling fans? What if the villain receives more cheers than the hero? This brings us again to Donald Trump, because this is the exact situation that the Fox News media machine faces with the billionaire candidate. They gave him the spotlight, what is called a “monster push” in professional wrestling, and built him up as a hero. While it's unlikely that the network would ever have considered him a viable candidate for president, in the early days of the campaign Trump was invaluable, in particular for his ability to channel the aggrieved right-wing populism that has infected the Republican voting base. Thus he was built up as a hero, as a babyface -- until, that is, it became clear what a threat he was to do real damage to the establishment's preferred candidates. That was the state of play when, at the first GOP debate earlier this month, Fox News's panel of debate moderators, including Megyn Kelly, made a concerted effort to take Trump down a peg -- to turn him heel, for all intents and purposes. We all know how that turned out. One of the greatest fears of a professional wrestling owner or promoter -- the person ultimately responsible for "booking" storylines and shaping the narrative direction of the company -- has traditionally been that a champion would go AWOL, and make the choice to not lose a title match when instructed. This could potentially create mayhem. The role of a champion -- especially one who is a villain such as Donald Trump -- is to ultimately to lose to a challenger, thus anointing them as the new figure for the fans to support (or alternatively to hate). But instead of accepting the fact that his political career is a creation of the Fox News echo chamber, Donald Trump, at least to this point, seems to actually believe that he is a viable candidate for presidency in 2016. Fox News tried to “bury” Donald Trump earlier this month. And as has happened in professional wrestling on many occasions, this actually made Donald Trump even more popular among movement conservatives and other extreme right-wing elements. Somewhere along the way, the Fox News media machine forgot to let Donald Trump know that his so-called candidacy was all a “work,” a type of fictional dramatic performance intended ultimately to "put over" someone else. This episode reveals the greatest peril in the creation of a spectacle. Whether you're a wrestling promoter or a power broker, Vince McMahon or Roger Ailes, your power to dictate the narrative can only ever take you as far the audience will allow. In the meta-narratives of both wrestling and politics -- in the behind-the-scenes machinations that result, in the public eye, in a particular outcome -- there is an very particular element of hubris. A heel has the power to captivate audiences; such is the seductive pull of transgression. Having understood this particular ability in Trump, but also the ultimate desired outcome of the Republican nominating contest -- namely, a nominee that is not Trump -- shouldn't Roger Ailes have known better than to push him on audiences as a brash truth-teller? Did he really think he could control someone like that? (Especially given the lather into which the conservative base has been worked over the past half-decade, in particular by Fox News.) In wrestling and politics both, you reap what you sow. If you're a wrestling promoter, the solution to this conundrum is simply to change a popular villain's alignment, make them into a babyface, piggybacking off their success in order to make it your own. But if you're Roger Ailes, faced with the prospect of Donald Trump as a dominant force in Republican politics, is that really a solution you're willing to brook? Are you comfortable making him your hero in a general election? This is the impossible situation into which Fox News and the Republican Party have navigated themselves. Media pundits have been caught off guard by the resiliency of the Trump campaign, seemingly impervious as it is to the traditional rules of play. But maybe they shouldn't have been. If the commentariat wants to make sense of Donald Trump’s apparent political madness, all they need to do is watch professional wrestling.The first thing you should know about me is that I am an unapologetic fan of professional wrestling -- of its outsize characters and operatic storylines, of its physical feats of strength and skill that even the biggest cynic, if they were honest, would have to grudgingly respect. While the sport's biggest stage, that of World Wrestling Entertainment, is often puerile and retrograde in its presentation, even that entertainment powerhouse is capable of staging moments of transcendent spectacle. I'm not alone in these affections, either: Donald Trump, the current Republican primary frontrunner, bomb thrower and nativist iconoclast, is an avid fan and student of pro wrestling, and a close friend and business associate of Vince McMahon, the owner and CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment. (Any familiarity with McMahon's paleolithic politics render these facts completely unsurprising.) Trump’s casinos have played host to two of the biggest events in WWE history, Wrestlemanias IV & V. He's a member of the WWE Hall of Fame. He even went so far as to perform at Wrestlemania 23, appearing ringside for a match dubbed -- wait for it -- "The Battle of the Billionaires." Of course, most Americans are probably now most likely to associate Trump with his maddening and ridiculous, yet unexpectedly ascendant, campaign for president. And yet, believe it or not, his time spent in the world of professional wrestling is invaluable for understanding the path he has cut through the GOP primary field -- because the playbook employed by Trump over the past several months bears an uncanny resemblance to the storytelling and character-building stratagem of professional wrestling. One could even be forgiven for concluding that Trump is directly calling on his knowledge and love of the performance art to create one of the most captivating -- and entertaining -- political stories of recent vintage. To understand why, we first need to establish a few key concepts. As a function of their origins in the classic dramatic form, the storylines in American professional wrestling revolve around the tension between a hero (a "babyface," in industry parlance, or "face" for short) and a villain (known primarily as the "heel"). In its most basic presentation, the babyface is a likable and honest character who wants to win the approval of the fans. He or she is an empathetic figure, one who remains stalwart and determined in their battles against a relentless opposition and overwhelming odds. The current standard bearer of the WWE, John Cena, is a consummate babyface -- touting the all-American values of "Hustle, Loyalty, Respect," and showing unqualified deference to the fans who make up the "WWE Universe." The heel, meanwhile, is the opposite of the face -- a duplicitous, unethical, often cowardly figure, who will cheat to win and who actively antagonizes the fans and his peers. The current champion of the WWE, Seth Rollins, is a quintessential "chickenshit" heel, a craven and bombastic figure who, in spite of his dazzling in-ring skill set and frequent bravura performances, appears incapable of winning big matches "clean," often requiring outside interference in order to maintain his grip on the championship. It's not hard to see how these roles translate into the world of politics. Narrative-building, whether in politics or in wrestling, both affect the structure and conventions of dramatic spectacle, wherein the depictions of conflict are engineered to magnify the intended emotional response in spectators. Any campaign's primary motivation is to elevate its own candidate -- to play the part of a babyface -- while convincingly depicting its opponent as the heel. To use the recent example of the 2012 presidential election, the Mitt Romney campaign, with an assist from Fox News, did its best to present the Republican candidate as a babyface -- the veteran businessman with a record of rescuing companies in distress, who could navigate America to a brighter future in the role of its chief executive. However, Romney was undermined by his own heelish tendencies, his patrician attitude and disconnectedness from the middle class experience, not to mention his actual record in private equity. The now-infamous "47 percent" video (what wrestling aficionados would call a "shoot promo," an unscripted speech that makes visible the artificiality of the spectacle) was his ultimate undoing, revealing as it did the apparent insincerity at the heart of his campaign's message. So there is the basic storytelling architecture: There is a face, and there is a heel, a good guy and a bad guy. Over time, alignments change: Good guys go bad, and bad guys become good. But there is always one of each, and these distinctions are meant to be crystal clear.

* * *

In his seminal essay on professional wrestling, Roland Barthes took special attention to performance of the heel archetype, which he describes as the "bastard," about which he wrote the following:Each sign in wrestling is [...] endowed with an absolute clarity, since one must always understand everything on the spot. As soon as the adversaries are in the ring, the public is overwhelmed with the obviousness of the roles. As in the theatre, each physical type expresses to excess the part which has been assigned to the contestant. Thauvin, a fifty-year-old with an obese and sagging body, whose type of asexual hideousness always inspires feminine nicknames, displays in his flesh the characters of baseness, for his part is to represent what, in the classical concept of the salaud, the 'bastard' (the key-concept of any wrestling-match), appears as organically repugnant. The nausea voluntarily provoked by Thauvin shows therefore a very extended use of signs: not only is ugliness used here in order to signify baseness, but in addition ugliness is wholly gathered into a particularly repulsive quality of matter: the pallid collapse of dead flesh (the public calls Thauvin la barbaque, 'stinking meat'), so that the passionate condemnation of the crowd no longer stems from its judgment, but instead from the very depth of its humours. It will thereafter let itself be frenetically embroiled in an idea of Thauvin which will conform entirely with this physical origin: his actions will perfectly correspond to the essential viscosity of his personage.The ultimate goal of a successful professional wrestler is to elicit an emotional response from the audience. Heels want to be booed and hated. Faces want approval and cheers. They are both masters of manipulation and psychology, taking the audience on an emotional journey of highs and lows. However, as the storytelling formula of professional wrestling has morphed over time, it has expanded to include antiheroes and other characters who do not fit neatly into a simple binary of good or bad. (These figures are sometimes called "tweeners.") Heroes can sometimes act like bullies, straining our allegiance. And villains who consistently entertain crowds can come to command more respect and admiration than their benevolent counterparts, even in spite of behavior that could be characterized, from a normative standpoint, as contemptible. What happens then, when the villain, because of their charisma, speaking ability, physical talent, or some intangible becomes popular with wrestling fans? What if the villain receives more cheers than the hero? This brings us again to Donald Trump, because this is the exact situation that the Fox News media machine faces with the billionaire candidate. They gave him the spotlight, what is called a “monster push” in professional wrestling, and built him up as a hero. While it's unlikely that the network would ever have considered him a viable candidate for president, in the early days of the campaign Trump was invaluable, in particular for his ability to channel the aggrieved right-wing populism that has infected the Republican voting base. Thus he was built up as a hero, as a babyface -- until, that is, it became clear what a threat he was to do real damage to the establishment's preferred candidates. That was the state of play when, at the first GOP debate earlier this month, Fox News's panel of debate moderators, including Megyn Kelly, made a concerted effort to take Trump down a peg -- to turn him heel, for all intents and purposes. We all know how that turned out. One of the greatest fears of a professional wrestling owner or promoter -- the person ultimately responsible for "booking" storylines and shaping the narrative direction of the company -- has traditionally been that a champion would go AWOL, and make the choice to not lose a title match when instructed. This could potentially create mayhem. The role of a champion -- especially one who is a villain such as Donald Trump -- is to ultimately to lose to a challenger, thus anointing them as the new figure for the fans to support (or alternatively to hate). But instead of accepting the fact that his political career is a creation of the Fox News echo chamber, Donald Trump, at least to this point, seems to actually believe that he is a viable candidate for presidency in 2016. Fox News tried to “bury” Donald Trump earlier this month. And as has happened in professional wrestling on many occasions, this actually made Donald Trump even more popular among movement conservatives and other extreme right-wing elements. Somewhere along the way, the Fox News media machine forgot to let Donald Trump know that his so-called candidacy was all a “work,” a type of fictional dramatic performance intended ultimately to "put over" someone else. This episode reveals the greatest peril in the creation of a spectacle. Whether you're a wrestling promoter or a power broker, Vince McMahon or Roger Ailes, your power to dictate the narrative can only ever take you as far the audience will allow. In the meta-narratives of both wrestling and politics -- in the behind-the-scenes machinations that result, in the public eye, in a particular outcome -- there is an very particular element of hubris. A heel has the power to captivate audiences; such is the seductive pull of transgression. Having understood this particular ability in Trump, but also the ultimate desired outcome of the Republican nominating contest -- namely, a nominee that is not Trump -- shouldn't Roger Ailes have known better than to push him on audiences as a brash truth-teller? Did he really think he could control someone like that? (Especially given the lather into which the conservative base has been worked over the past half-decade, in particular by Fox News.) In wrestling and politics both, you reap what you sow. If you're a wrestling promoter, the solution to this conundrum is simply to change a popular villain's alignment, make them into a babyface, piggybacking off their success in order to make it your own. But if you're Roger Ailes, faced with the prospect of Donald Trump as a dominant force in Republican politics, is that really a solution you're willing to brook? Are you comfortable making him your hero in a general election? This is the impossible situation into which Fox News and the Republican Party have navigated themselves. Media pundits have been caught off guard by the resiliency of the Trump campaign, seemingly impervious as it is to the traditional rules of play. But maybe they shouldn't have been. If the commentariat wants to make sense of Donald Trump’s apparent political madness, all they need to do is watch professional wrestling.The first thing you should know about me is that I am an unapologetic fan of professional wrestling -- of its outsize characters and operatic storylines, of its physical feats of strength and skill that even the biggest cynic, if they were honest, would have to grudgingly respect. While the sport's biggest stage, that of World Wrestling Entertainment, is often puerile and retrograde in its presentation, even that entertainment powerhouse is capable of staging moments of transcendent spectacle. I'm not alone in these affections, either: Donald Trump, the current Republican primary frontrunner, bomb thrower and nativist iconoclast, is an avid fan and student of pro wrestling, and a close friend and business associate of Vince McMahon, the owner and CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment. (Any familiarity with McMahon's paleolithic politics render these facts completely unsurprising.) Trump’s casinos have played host to two of the biggest events in WWE history, Wrestlemanias IV & V. He's a member of the WWE Hall of Fame. He even went so far as to perform at Wrestlemania 23, appearing ringside for a match dubbed -- wait for it -- "The Battle of the Billionaires." Of course, most Americans are probably now most likely to associate Trump with his maddening and ridiculous, yet unexpectedly ascendant, campaign for president. And yet, believe it or not, his time spent in the world of professional wrestling is invaluable for understanding the path he has cut through the GOP primary field -- because the playbook employed by Trump over the past several months bears an uncanny resemblance to the storytelling and character-building stratagem of professional wrestling. One could even be forgiven for concluding that Trump is directly calling on his knowledge and love of the performance art to create one of the most captivating -- and entertaining -- political stories of recent vintage. To understand why, we first need to establish a few key concepts. As a function of their origins in the classic dramatic form, the storylines in American professional wrestling revolve around the tension between a hero (a "babyface," in industry parlance, or "face" for short) and a villain (known primarily as the "heel"). In its most basic presentation, the babyface is a likable and honest character who wants to win the approval of the fans. He or she is an empathetic figure, one who remains stalwart and determined in their battles against a relentless opposition and overwhelming odds. The current standard bearer of the WWE, John Cena, is a consummate babyface -- touting the all-American values of "Hustle, Loyalty, Respect," and showing unqualified deference to the fans who make up the "WWE Universe." The heel, meanwhile, is the opposite of the face -- a duplicitous, unethical, often cowardly figure, who will cheat to win and who actively antagonizes the fans and his peers. The current champion of the WWE, Seth Rollins, is a quintessential "chickenshit" heel, a craven and bombastic figure who, in spite of his dazzling in-ring skill set and frequent bravura performances, appears incapable of winning big matches "clean," often requiring outside interference in order to maintain his grip on the championship. It's not hard to see how these roles translate into the world of politics. Narrative-building, whether in politics or in wrestling, both affect the structure and conventions of dramatic spectacle, wherein the depictions of conflict are engineered to magnify the intended emotional response in spectators. Any campaign's primary motivation is to elevate its own candidate -- to play the part of a babyface -- while convincingly depicting its opponent as the heel. To use the recent example of the 2012 presidential election, the Mitt Romney campaign, with an assist from Fox News, did its best to present the Republican candidate as a babyface -- the veteran businessman with a record of rescuing companies in distress, who could navigate America to a brighter future in the role of its chief executive. However, Romney was undermined by his own heelish tendencies, his patrician attitude and disconnectedness from the middle class experience, not to mention his actual record in private equity. The now-infamous "47 percent" video (what wrestling aficionados would call a "shoot promo," an unscripted speech that makes visible the artificiality of the spectacle) was his ultimate undoing, revealing as it did the apparent insincerity at the heart of his campaign's message. So there is the basic storytelling architecture: There is a face, and there is a heel, a good guy and a bad guy. Over time, alignments change: Good guys go bad, and bad guys become good. But there is always one of each, and these distinctions are meant to be crystal clear.

* * *

In his seminal essay on professional wrestling, Roland Barthes took special attention to performance of the heel archetype, which he describes as the "bastard," about which he wrote the following:Each sign in wrestling is [...] endowed with an absolute clarity, since one must always understand everything on the spot. As soon as the adversaries are in the ring, the public is overwhelmed with the obviousness of the roles. As in the theatre, each physical type expresses to excess the part which has been assigned to the contestant. Thauvin, a fifty-year-old with an obese and sagging body, whose type of asexual hideousness always inspires feminine nicknames, displays in his flesh the characters of baseness, for his part is to represent what, in the classical concept of the salaud, the 'bastard' (the key-concept of any wrestling-match), appears as organically repugnant. The nausea voluntarily provoked by Thauvin shows therefore a very extended use of signs: not only is ugliness used here in order to signify baseness, but in addition ugliness is wholly gathered into a particularly repulsive quality of matter: the pallid collapse of dead flesh (the public calls Thauvin la barbaque, 'stinking meat'), so that the passionate condemnation of the crowd no longer stems from its judgment, but instead from the very depth of its humours. It will thereafter let itself be frenetically embroiled in an idea of Thauvin which will conform entirely with this physical origin: his actions will perfectly correspond to the essential viscosity of his personage.The ultimate goal of a successful professional wrestler is to elicit an emotional response from the audience. Heels want to be booed and hated. Faces want approval and cheers. They are both masters of manipulation and psychology, taking the audience on an emotional journey of highs and lows. However, as the storytelling formula of professional wrestling has morphed over time, it has expanded to include antiheroes and other characters who do not fit neatly into a simple binary of good or bad. (These figures are sometimes called "tweeners.") Heroes can sometimes act like bullies, straining our allegiance. And villains who consistently entertain crowds can come to command more respect and admiration than their benevolent counterparts, even in spite of behavior that could be characterized, from a normative standpoint, as contemptible. What happens then, when the villain, because of their charisma, speaking ability, physical talent, or some intangible becomes popular with wrestling fans? What if the villain receives more cheers than the hero? This brings us again to Donald Trump, because this is the exact situation that the Fox News media machine faces with the billionaire candidate. They gave him the spotlight, what is called a “monster push” in professional wrestling, and built him up as a hero. While it's unlikely that the network would ever have considered him a viable candidate for president, in the early days of the campaign Trump was invaluable, in particular for his ability to channel the aggrieved right-wing populism that has infected the Republican voting base. Thus he was built up as a hero, as a babyface -- until, that is, it became clear what a threat he was to do real damage to the establishment's preferred candidates. That was the state of play when, at the first GOP debate earlier this month, Fox News's panel of debate moderators, including Megyn Kelly, made a concerted effort to take Trump down a peg -- to turn him heel, for all intents and purposes. We all know how that turned out. One of the greatest fears of a professional wrestling owner or promoter -- the person ultimately responsible for "booking" storylines and shaping the narrative direction of the company -- has traditionally been that a champion would go AWOL, and make the choice to not lose a title match when instructed. This could potentially create mayhem. The role of a champion -- especially one who is a villain such as Donald Trump -- is to ultimately to lose to a challenger, thus anointing them as the new figure for the fans to support (or alternatively to hate). But instead of accepting the fact that his political career is a creation of the Fox News echo chamber, Donald Trump, at least to this point, seems to actually believe that he is a viable candidate for presidency in 2016. Fox News tried to “bury” Donald Trump earlier this month. And as has happened in professional wrestling on many occasions, this actually made Donald Trump even more popular among movement conservatives and other extreme right-wing elements. Somewhere along the way, the Fox News media machine forgot to let Donald Trump know that his so-called candidacy was all a “work,” a type of fictional dramatic performance intended ultimately to "put over" someone else. This episode reveals the greatest peril in the creation of a spectacle. Whether you're a wrestling promoter or a power broker, Vince McMahon or Roger Ailes, your power to dictate the narrative can only ever take you as far the audience will allow. In the meta-narratives of both wrestling and politics -- in the behind-the-scenes machinations that result, in the public eye, in a particular outcome -- there is an very particular element of hubris. A heel has the power to captivate audiences; such is the seductive pull of transgression. Having understood this particular ability in Trump, but also the ultimate desired outcome of the Republican nominating contest -- namely, a nominee that is not Trump -- shouldn't Roger Ailes have known better than to push him on audiences as a brash truth-teller? Did he really think he could control someone like that? (Especially given the lather into which the conservative base has been worked over the past half-decade, in particular by Fox News.) In wrestling and politics both, you reap what you sow. If you're a wrestling promoter, the solution to this conundrum is simply to change a popular villain's alignment, make them into a babyface, piggybacking off their success in order to make it your own. But if you're Roger Ailes, faced with the prospect of Donald Trump as a dominant force in Republican politics, is that really a solution you're willing to brook? Are you comfortable making him your hero in a general election? This is the impossible situation into which Fox News and the Republican Party have navigated themselves. Media pundits have been caught off guard by the resiliency of the Trump campaign, seemingly impervious as it is to the traditional rules of play. But maybe they shouldn't have been. If the commentariat wants to make sense of Donald Trump’s apparent political madness, all they need to do is watch professional wrestling.

Jeb Bush’s gigantic Iraq fail: Why he’s handling his brother’s toxic legacy in just about the worst way possible

At Iowa State Fair, Jeb Bush plays the sober adult in a summer of angerAh yes, the proverbial "grown-ups are back" story from the beltway press. The last time they characterized Republicans that way they were talking about the mature, serious leadership of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. You remember, the president who engaged us in a decade-long war under false pretenses and the Vice President who said that waterboarding was a no brainer? Those adults. This time, however, the press seems to be indicating that "adult" means lifeless, dull and incoherent, at least as it pertains to the third in line for the throne, Jeb Bush. The article in question tells the story of Jeb's trip to the Iowa State fair, where he's just an "awe shucks" sort of guy hanging with the folks:

"I’m tired of the divides," the former Florida governor said. "I campaign the way that I would govern — out amongst everybody, no rope lines, totally out in the open." Then the fairgoers started asking Bush questions. They asked about the legacy of his brother, a former president. And his father, another former president. And his foreign policy adviser, Paul Wolfowitz, architect of his brother’s Iraq war. And about the war itself. And about the Common Core educational standards that have become a lightening rod for Bush with conservatives. "The term Common Core is so darn poisonous I don’t even know what that means," Bush replied. "So here’s what I’m for: I’m for higher standards — state created, locally implemented where the federal government has no role in the creation of standards, content or curriculum." Bush parried the questions with ease and energy, appearing to avoid the kind of gaffes that have plagued other candidates at the soapbox, which is sponsored by The Des Moines Register. In 2011, after all, Mitt Romney stood on the same stage and declared, "Corporations are people" -- a line that dogged him seemingly forever.Can you see the problem there? First, let's get the Common Core thing out of the way. Bush has been a proponent of the program since its inception. His name is intimately associated with it. Perhaps it's not as big a gaffe as "corporations are people" but it's far more dishonest. Basically, he's disowning something that he's been in favor of for years without admitting it. But it's the other set of questions about using his brother's advisors and his current thinking about the Iraq war that are of interest. After all, there is no foreign policy decision more controversial in the last several decades than the decision to (virtually unilaterally) invade Iraq on a very thin legal pretext and based on intelligence that was dubiously obtained and disseminated. He was specifically asked about his repeated statement that he would call upon one of his brother's most dubious advisors, Paul Wolfowitz -- which, as I've written here at length, should be a problem for anyone running for president. Paul Waldman describes his ever evolving rationales about the current problems in Iraq in this piece and it's clear that Bush's understanding of what happened is either very rudimentary or he's being deliberately dishonest. Saying that getting rid of Saddam was "a good deal" is not going to smooth over the the searing reality that the region is in chaos, and blaming Obama for the fallout doesn't change the fact that the invasion was the most disastrous foreign policy decision in modern memory. Bush brushed off the question with an answer that should set off alarms in the minds of anyone who's been following politics for the past 30 years:

"I get most of my advice from a team that we have in Miami, Florida. Young people that are going to be ... they're not assigned, have experience either in Congress or the previous administration. "If they’ve had any executive experience, they’ve had to deal with two Republican administrations. Who were the people who were presidents, the last two Republicans? I mean, this is kind of a tough game to be playing, to be honest with you. I’m my own person."Who were the last two Republican presidents, you ask? Well, they were both named Bush and they both temporarily experienced sky high approval ratings when they decided to wage war in the middle east and then both left office in disgrace, loathed by nearly everyone in both parties. Jeb's insistence that the only people with "any executive experience" already worked with his dad and his baby bro makes it seem like he has no choice in the matter, except to take advice from the guy who was arguing for invading Iraq on Sept. 15, 2001. Uh huh. The question is whether this issue is salient enough to hurt Jeb in the primaries. There are those, like liberal columnist Eugene Robinson who correctly observe that however much Jeb desires to cast off the smothering cloak of his brother's very recent failed record, his policy statements indicate that it's only campaign talk:

Bush says "we do not need ... a major commitment" of American ground troops in Iraq or Syria to fight against the Islamic State -- at least for now. But he proposes embedding U.S. soldiers and Marines with Iraqi units, which basically means leading them into battle. He proposes much greater support for Kurdish forces, which are loath to fight in the Sunni heartlands where the Islamic State holds sway. And he wants the establishment of no-fly zones and safe havens in Syria, as a way to battle both the Islamic State and dictator Bashar al-Assad. That all sounds like a "major commitment" of something. And none of it addresses the fundamental problem in Iraq, which George W. Bush also failed to grasp: the lack of political reconciliation among Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds. Bush 43's vaunted "surge" was a Band-Aid that masked, but did not heal, this underlying wound.This piece by Peter Beinert about the vaunted "surge" spells out the details of that to which Robinson alludes. Jeb (like all the other Republican candidates) pretends that Iraq was a rousing success, and everyone was living together in peace and harmony until the evil team of Obama/Clinton blew it all up. This, of course, could not be further from the truth. But this piece by Phillip Bump of the Washington Post blog The Fix, suggests this may not be the problem we might assume it would be, at least not on the Republican side of aisle:

There hasn't been a lot of recent polling on the public perception of the Iraq War, but there has been some. And that polling suggests that -- especially in a Republican primary election -- the war is not the toxic topic that it was in 2008. In June, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal included support for the Iraq War in a long list of questions about how people would view candidates who held particular positions. For 64 percent of respondents, having backed the Iraq War either didn't affect their view of the candidate or made them view the candidate more favorably. More telling is a survey the same month from Gallup. The polling agency compared the number of people who said the war was a mistake in February 2014 to the percentage saying that now, and broke out the results by party. Both Democrats and independents were more likely to say that the war wasn't a mistake than in the past -- but only 31 percent of Republicans thought it was a mistake at all. Leaving 69 percent with either no opinion or a favorable one. In a 17-person race, support from 69 percent of the electorate is surely more than welcome.It was inevitable that the Republicans would find a way to make peace with the catastrophe in Iraq. They like war and they passionately backed that one at the time. It's very hard to reconcile the cognitive dissonance of having pushed that hard for war when forced to recognize the failure that followed. So, instead, they are rewriting history to show it as a thrilling victory that was reversed by the inexplicable decision by President Obama to bring the troops home. That's the kind of thinking that works for them. In my opinion, Bush has problems with the base, but I'd guess it has more to do with his membership in the family that continuously embarrasses them. They don't like having to make excuses for their leadership. (And they have to do it so often.) It's also a matter of his lackluster personality. The Republicans are looking for a crusading partisan warrior this time out, someone who will carry their banner both domestically and internationally. Jeb Bush is a hardcore conservative, but he just doesn't deliver a punch with any passion. Perhaps they'll settle for him when all is said and done. But he doesn't get their blood pumping and they really want someone who does. Bush's real Iraq problem comes in the general. If Clinton gets the nod, he will throw her war vote in her face and try to tie the chaos that exists there to her. And most Republicans will buy it. But it's hard to imagine that 50 percent plus 1 of this country will not see Jeb and think of that horrible period after 9/11 when the government invaded a country that had nothing to do with it. It's very hard for any Republican to get past the party's association with a blunder of that magnitude --- it's impossible for a man whose last name is Bush. And it sure seems as though somewhere deep down inside, Jeb knows it.Considering the level of clownish extremism in the Republican primary during these mangy dog days of August, it's probably inevitable that we would start to see headlines like this one from the Washington Post on Friday:

At Iowa State Fair, Jeb Bush plays the sober adult in a summer of angerAh yes, the proverbial "grown-ups are back" story from the beltway press. The last time they characterized Republicans that way they were talking about the mature, serious leadership of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. You remember, the president who engaged us in a decade-long war under false pretenses and the Vice President who said that waterboarding was a no brainer? Those adults. This time, however, the press seems to be indicating that "adult" means lifeless, dull and incoherent, at least as it pertains to the third in line for the throne, Jeb Bush. The article in question tells the story of Jeb's trip to the Iowa State fair, where he's just an "awe shucks" sort of guy hanging with the folks:

"I’m tired of the divides," the former Florida governor said. "I campaign the way that I would govern — out amongst everybody, no rope lines, totally out in the open." Then the fairgoers started asking Bush questions. They asked about the legacy of his brother, a former president. And his father, another former president. And his foreign policy adviser, Paul Wolfowitz, architect of his brother’s Iraq war. And about the war itself. And about the Common Core educational standards that have become a lightening rod for Bush with conservatives. "The term Common Core is so darn poisonous I don’t even know what that means," Bush replied. "So here’s what I’m for: I’m for higher standards — state created, locally implemented where the federal government has no role in the creation of standards, content or curriculum." Bush parried the questions with ease and energy, appearing to avoid the kind of gaffes that have plagued other candidates at the soapbox, which is sponsored by The Des Moines Register. In 2011, after all, Mitt Romney stood on the same stage and declared, "Corporations are people" -- a line that dogged him seemingly forever.Can you see the problem there? First, let's get the Common Core thing out of the way. Bush has been a proponent of the program since its inception. His name is intimately associated with it. Perhaps it's not as big a gaffe as "corporations are people" but it's far more dishonest. Basically, he's disowning something that he's been in favor of for years without admitting it. But it's the other set of questions about using his brother's advisors and his current thinking about the Iraq war that are of interest. After all, there is no foreign policy decision more controversial in the last several decades than the decision to (virtually unilaterally) invade Iraq on a very thin legal pretext and based on intelligence that was dubiously obtained and disseminated. He was specifically asked about his repeated statement that he would call upon one of his brother's most dubious advisors, Paul Wolfowitz -- which, as I've written here at length, should be a problem for anyone running for president. Paul Waldman describes his ever evolving rationales about the current problems in Iraq in this piece and it's clear that Bush's understanding of what happened is either very rudimentary or he's being deliberately dishonest. Saying that getting rid of Saddam was "a good deal" is not going to smooth over the the searing reality that the region is in chaos, and blaming Obama for the fallout doesn't change the fact that the invasion was the most disastrous foreign policy decision in modern memory. Bush brushed off the question with an answer that should set off alarms in the minds of anyone who's been following politics for the past 30 years:

"I get most of my advice from a team that we have in Miami, Florida. Young people that are going to be ... they're not assigned, have experience either in Congress or the previous administration. "If they’ve had any executive experience, they’ve had to deal with two Republican administrations. Who were the people who were presidents, the last two Republicans? I mean, this is kind of a tough game to be playing, to be honest with you. I’m my own person."Who were the last two Republican presidents, you ask? Well, they were both named Bush and they both temporarily experienced sky high approval ratings when they decided to wage war in the middle east and then both left office in disgrace, loathed by nearly everyone in both parties. Jeb's insistence that the only people with "any executive experience" already worked with his dad and his baby bro makes it seem like he has no choice in the matter, except to take advice from the guy who was arguing for invading Iraq on Sept. 15, 2001. Uh huh. The question is whether this issue is salient enough to hurt Jeb in the primaries. There are those, like liberal columnist Eugene Robinson who correctly observe that however much Jeb desires to cast off the smothering cloak of his brother's very recent failed record, his policy statements indicate that it's only campaign talk:

Bush says "we do not need ... a major commitment" of American ground troops in Iraq or Syria to fight against the Islamic State -- at least for now. But he proposes embedding U.S. soldiers and Marines with Iraqi units, which basically means leading them into battle. He proposes much greater support for Kurdish forces, which are loath to fight in the Sunni heartlands where the Islamic State holds sway. And he wants the establishment of no-fly zones and safe havens in Syria, as a way to battle both the Islamic State and dictator Bashar al-Assad. That all sounds like a "major commitment" of something. And none of it addresses the fundamental problem in Iraq, which George W. Bush also failed to grasp: the lack of political reconciliation among Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds. Bush 43's vaunted "surge" was a Band-Aid that masked, but did not heal, this underlying wound.This piece by Peter Beinert about the vaunted "surge" spells out the details of that to which Robinson alludes. Jeb (like all the other Republican candidates) pretends that Iraq was a rousing success, and everyone was living together in peace and harmony until the evil team of Obama/Clinton blew it all up. This, of course, could not be further from the truth. But this piece by Phillip Bump of the Washington Post blog The Fix, suggests this may not be the problem we might assume it would be, at least not on the Republican side of aisle:

There hasn't been a lot of recent polling on the public perception of the Iraq War, but there has been some. And that polling suggests that -- especially in a Republican primary election -- the war is not the toxic topic that it was in 2008. In June, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal included support for the Iraq War in a long list of questions about how people would view candidates who held particular positions. For 64 percent of respondents, having backed the Iraq War either didn't affect their view of the candidate or made them view the candidate more favorably. More telling is a survey the same month from Gallup. The polling agency compared the number of people who said the war was a mistake in February 2014 to the percentage saying that now, and broke out the results by party. Both Democrats and independents were more likely to say that the war wasn't a mistake than in the past -- but only 31 percent of Republicans thought it was a mistake at all. Leaving 69 percent with either no opinion or a favorable one. In a 17-person race, support from 69 percent of the electorate is surely more than welcome.It was inevitable that the Republicans would find a way to make peace with the catastrophe in Iraq. They like war and they passionately backed that one at the time. It's very hard to reconcile the cognitive dissonance of having pushed that hard for war when forced to recognize the failure that followed. So, instead, they are rewriting history to show it as a thrilling victory that was reversed by the inexplicable decision by President Obama to bring the troops home. That's the kind of thinking that works for them. In my opinion, Bush has problems with the base, but I'd guess it has more to do with his membership in the family that continuously embarrasses them. They don't like having to make excuses for their leadership. (And they have to do it so often.) It's also a matter of his lackluster personality. The Republicans are looking for a crusading partisan warrior this time out, someone who will carry their banner both domestically and internationally. Jeb Bush is a hardcore conservative, but he just doesn't deliver a punch with any passion. Perhaps they'll settle for him when all is said and done. But he doesn't get their blood pumping and they really want someone who does. Bush's real Iraq problem comes in the general. If Clinton gets the nod, he will throw her war vote in her face and try to tie the chaos that exists there to her. And most Republicans will buy it. But it's hard to imagine that 50 percent plus 1 of this country will not see Jeb and think of that horrible period after 9/11 when the government invaded a country that had nothing to do with it. It's very hard for any Republican to get past the party's association with a blunder of that magnitude --- it's impossible for a man whose last name is Bush. And it sure seems as though somewhere deep down inside, Jeb knows it.Considering the level of clownish extremism in the Republican primary during these mangy dog days of August, it's probably inevitable that we would start to see headlines like this one from the Washington Post on Friday:

At Iowa State Fair, Jeb Bush plays the sober adult in a summer of angerAh yes, the proverbial "grown-ups are back" story from the beltway press. The last time they characterized Republicans that way they were talking about the mature, serious leadership of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. You remember, the president who engaged us in a decade-long war under false pretenses and the Vice President who said that waterboarding was a no brainer? Those adults. This time, however, the press seems to be indicating that "adult" means lifeless, dull and incoherent, at least as it pertains to the third in line for the throne, Jeb Bush. The article in question tells the story of Jeb's trip to the Iowa State fair, where he's just an "awe shucks" sort of guy hanging with the folks:

"I’m tired of the divides," the former Florida governor said. "I campaign the way that I would govern — out amongst everybody, no rope lines, totally out in the open." Then the fairgoers started asking Bush questions. They asked about the legacy of his brother, a former president. And his father, another former president. And his foreign policy adviser, Paul Wolfowitz, architect of his brother’s Iraq war. And about the war itself. And about the Common Core educational standards that have become a lightening rod for Bush with conservatives. "The term Common Core is so darn poisonous I don’t even know what that means," Bush replied. "So here’s what I’m for: I’m for higher standards — state created, locally implemented where the federal government has no role in the creation of standards, content or curriculum." Bush parried the questions with ease and energy, appearing to avoid the kind of gaffes that have plagued other candidates at the soapbox, which is sponsored by The Des Moines Register. In 2011, after all, Mitt Romney stood on the same stage and declared, "Corporations are people" -- a line that dogged him seemingly forever.Can you see the problem there? First, let's get the Common Core thing out of the way. Bush has been a proponent of the program since its inception. His name is intimately associated with it. Perhaps it's not as big a gaffe as "corporations are people" but it's far more dishonest. Basically, he's disowning something that he's been in favor of for years without admitting it. But it's the other set of questions about using his brother's advisors and his current thinking about the Iraq war that are of interest. After all, there is no foreign policy decision more controversial in the last several decades than the decision to (virtually unilaterally) invade Iraq on a very thin legal pretext and based on intelligence that was dubiously obtained and disseminated. He was specifically asked about his repeated statement that he would call upon one of his brother's most dubious advisors, Paul Wolfowitz -- which, as I've written here at length, should be a problem for anyone running for president. Paul Waldman describes his ever evolving rationales about the current problems in Iraq in this piece and it's clear that Bush's understanding of what happened is either very rudimentary or he's being deliberately dishonest. Saying that getting rid of Saddam was "a good deal" is not going to smooth over the the searing reality that the region is in chaos, and blaming Obama for the fallout doesn't change the fact that the invasion was the most disastrous foreign policy decision in modern memory. Bush brushed off the question with an answer that should set off alarms in the minds of anyone who's been following politics for the past 30 years:

"I get most of my advice from a team that we have in Miami, Florida. Young people that are going to be ... they're not assigned, have experience either in Congress or the previous administration. "If they’ve had any executive experience, they’ve had to deal with two Republican administrations. Who were the people who were presidents, the last two Republicans? I mean, this is kind of a tough game to be playing, to be honest with you. I’m my own person."Who were the last two Republican presidents, you ask? Well, they were both named Bush and they both temporarily experienced sky high approval ratings when they decided to wage war in the middle east and then both left office in disgrace, loathed by nearly everyone in both parties. Jeb's insistence that the only people with "any executive experience" already worked with his dad and his baby bro makes it seem like he has no choice in the matter, except to take advice from the guy who was arguing for invading Iraq on Sept. 15, 2001. Uh huh. The question is whether this issue is salient enough to hurt Jeb in the primaries. There are those, like liberal columnist Eugene Robinson who correctly observe that however much Jeb desires to cast off the smothering cloak of his brother's very recent failed record, his policy statements indicate that it's only campaign talk:

Bush says "we do not need ... a major commitment" of American ground troops in Iraq or Syria to fight against the Islamic State -- at least for now. But he proposes embedding U.S. soldiers and Marines with Iraqi units, which basically means leading them into battle. He proposes much greater support for Kurdish forces, which are loath to fight in the Sunni heartlands where the Islamic State holds sway. And he wants the establishment of no-fly zones and safe havens in Syria, as a way to battle both the Islamic State and dictator Bashar al-Assad. That all sounds like a "major commitment" of something. And none of it addresses the fundamental problem in Iraq, which George W. Bush also failed to grasp: the lack of political reconciliation among Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds. Bush 43's vaunted "surge" was a Band-Aid that masked, but did not heal, this underlying wound.This piece by Peter Beinert about the vaunted "surge" spells out the details of that to which Robinson alludes. Jeb (like all the other Republican candidates) pretends that Iraq was a rousing success, and everyone was living together in peace and harmony until the evil team of Obama/Clinton blew it all up. This, of course, could not be further from the truth. But this piece by Phillip Bump of the Washington Post blog The Fix, suggests this may not be the problem we might assume it would be, at least not on the Republican side of aisle:

There hasn't been a lot of recent polling on the public perception of the Iraq War, but there has been some. And that polling suggests that -- especially in a Republican primary election -- the war is not the toxic topic that it was in 2008. In June, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal included support for the Iraq War in a long list of questions about how people would view candidates who held particular positions. For 64 percent of respondents, having backed the Iraq War either didn't affect their view of the candidate or made them view the candidate more favorably. More telling is a survey the same month from Gallup. The polling agency compared the number of people who said the war was a mistake in February 2014 to the percentage saying that now, and broke out the results by party. Both Democrats and independents were more likely to say that the war wasn't a mistake than in the past -- but only 31 percent of Republicans thought it was a mistake at all. Leaving 69 percent with either no opinion or a favorable one. In a 17-person race, support from 69 percent of the electorate is surely more than welcome.It was inevitable that the Republicans would find a way to make peace with the catastrophe in Iraq. They like war and they passionately backed that one at the time. It's very hard to reconcile the cognitive dissonance of having pushed that hard for war when forced to recognize the failure that followed. So, instead, they are rewriting history to show it as a thrilling victory that was reversed by the inexplicable decision by President Obama to bring the troops home. That's the kind of thinking that works for them. In my opinion, Bush has problems with the base, but I'd guess it has more to do with his membership in the family that continuously embarrasses them. They don't like having to make excuses for their leadership. (And they have to do it so often.) It's also a matter of his lackluster personality. The Republicans are looking for a crusading partisan warrior this time out, someone who will carry their banner both domestically and internationally. Jeb Bush is a hardcore conservative, but he just doesn't deliver a punch with any passion. Perhaps they'll settle for him when all is said and done. But he doesn't get their blood pumping and they really want someone who does. Bush's real Iraq problem comes in the general. If Clinton gets the nod, he will throw her war vote in her face and try to tie the chaos that exists there to her. And most Republicans will buy it. But it's hard to imagine that 50 percent plus 1 of this country will not see Jeb and think of that horrible period after 9/11 when the government invaded a country that had nothing to do with it. It's very hard for any Republican to get past the party's association with a blunder of that magnitude --- it's impossible for a man whose last name is Bush. And it sure seems as though somewhere deep down inside, Jeb knows it.

The GOP’s apocalyptic Obama fantasies: Why Cruz & Walker’s economic fear-mongering makes literally zero sense

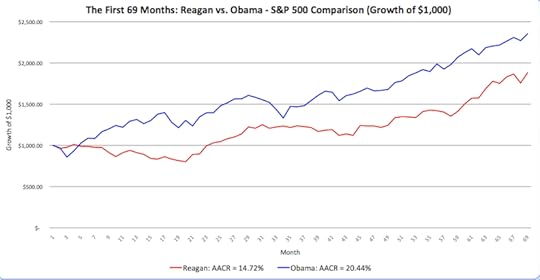

What’s now clear is that the Obama administration policies have outperformed the Reagan administration policies for job creation and unemployment reduction. Even though Reagan had the benefit of a growing Boomer class to ignite economic growth, while Obama has been forced to deal with a retiring workforce developing special needs. During the eight years preceding Obama there was a net reduction in jobs in America. We now are rapidly moving toward higher, sustainable jobs growth.Notice that when you hear the Republicans screeching about the "labor participation rate" (see Jeb Bush above), they never mention the massive influx of retiring baby boomers leaving the workforce. Convenient. 2) The Obama Economic Expansion We can't really gripe about America "not making anything anymore." For the longest time, we've watched as manufacturing jobs were moved overseas to exploit cheaper labor. But during the Obama administration, Institute for Supply Management's Purchasing Managers Index reported, there's been 74 consecutive months of economic expansion, and 31 consecutive months of growth in the manufacturing sector. You'll never hear anything about this from the GOP. Someone should ask them about this -- perhaps during a nationally televised debate. 3) Wall Street Given how Reagan did have to contend with, again, the greatest recession since the Great Depression and a bottomless crash of the stock market, this chart should blow your mind.

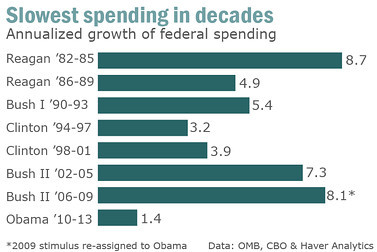

During the Reagan years, your investments grew by 190 percent. That's a lot. Under Obama, however, the same dollar has yielded a 220 percent gain. That's a lot more. If you own shares in the company you work for, you're probably doing better. If you have a 401(k), you're probably doing much better. If you have an IRA, you're doing great. Overall, Dow has reached record highs under Obama -- over 17,400 -- not too shabby for a guy whose economic policies were considered to be the arrival of European socialism, or worse. 4) The Deficit Call me a blasphemer, but Reagan was comparatively terrible on government growth and spending, two areas where conservatism is supposed to rule the day. Reagan famously declared, "Government is the problem," vowing to reduce the size of government. Sorry. He really didn't. The deficit doubled and the debt tripled. Under Obama, the budget deficit has declined by more than a trillion dollars, according to the not-liberal Wall Street Journal. I repeat: the federal budget deficit has gone from $1.4 trillion when Obama took office to around $300 billion. And while government employment increased under Reagan, literally expanding the size of government, it's declined under Obama, much to the detriment of his overall employment numbers.

During the Reagan years, your investments grew by 190 percent. That's a lot. Under Obama, however, the same dollar has yielded a 220 percent gain. That's a lot more. If you own shares in the company you work for, you're probably doing better. If you have a 401(k), you're probably doing much better. If you have an IRA, you're doing great. Overall, Dow has reached record highs under Obama -- over 17,400 -- not too shabby for a guy whose economic policies were considered to be the arrival of European socialism, or worse. 4) The Deficit Call me a blasphemer, but Reagan was comparatively terrible on government growth and spending, two areas where conservatism is supposed to rule the day. Reagan famously declared, "Government is the problem," vowing to reduce the size of government. Sorry. He really didn't. The deficit doubled and the debt tripled. Under Obama, the budget deficit has declined by more than a trillion dollars, according to the not-liberal Wall Street Journal. I repeat: the federal budget deficit has gone from $1.4 trillion when Obama took office to around $300 billion. And while government employment increased under Reagan, literally expanding the size of government, it's declined under Obama, much to the detriment of his overall employment numbers.

While we're here, we should nip something in the bud. Yes, Congress "controls the purse strings," and, no, "the president doesn't create jobs." But if you're going to credit Reagan or Clinton or whomever with the deficit or economic growth, then you have to credit Obama for the same. Likewise, if you're going to criticize Obama because you perceive a weak economy, then you have to give him credit when it's strong. You can't have it both ways. You can't blame him for a bad economy, then suggest improvements are the result of actions by someone else. Well, I suppose you can do that, but you're going to sound silly. Also, chew on this. A Democratic House during the 1980s, and its speaker Tip O'Neill, passed all of the spending bills during the Reagan years. As we all know, spending bills have to be signed into law by the president. So, then, which president signed all of those tax-and-spend liberal bills into law, ballooning the deficit and debt? Hint: not Obama. Along those lines, it's easy to stimulate huge economic growth via limitless deficit spending. Hence, the Reagan economy. Conversely, deficit spending has dropped precipitously under Obama and yet, 1) he's not being given fair credit for it, and 2) the economy continues to expand anyway -- the stock market is booming and unemployment is falling. This speaks volumes about the Obama record versus the gilded Reagan record. It also hints to the shift in economic policy between the parties. The Democrats are slowly embracing lower spending, while the Republicans are embracing increased spending on unnecessary wars and tax cuts. Republicans, especially under Reagan and George W. Bush, don't seem to mind swiping our national credit card down to a worthless nub. But you'll never hear this from Trump and the rest, who can't stop proverbially humping Reagan's leg while lying about Obama's truly noteworthy economic record.

While we're here, we should nip something in the bud. Yes, Congress "controls the purse strings," and, no, "the president doesn't create jobs." But if you're going to credit Reagan or Clinton or whomever with the deficit or economic growth, then you have to credit Obama for the same. Likewise, if you're going to criticize Obama because you perceive a weak economy, then you have to give him credit when it's strong. You can't have it both ways. You can't blame him for a bad economy, then suggest improvements are the result of actions by someone else. Well, I suppose you can do that, but you're going to sound silly. Also, chew on this. A Democratic House during the 1980s, and its speaker Tip O'Neill, passed all of the spending bills during the Reagan years. As we all know, spending bills have to be signed into law by the president. So, then, which president signed all of those tax-and-spend liberal bills into law, ballooning the deficit and debt? Hint: not Obama. Along those lines, it's easy to stimulate huge economic growth via limitless deficit spending. Hence, the Reagan economy. Conversely, deficit spending has dropped precipitously under Obama and yet, 1) he's not being given fair credit for it, and 2) the economy continues to expand anyway -- the stock market is booming and unemployment is falling. This speaks volumes about the Obama record versus the gilded Reagan record. It also hints to the shift in economic policy between the parties. The Democrats are slowly embracing lower spending, while the Republicans are embracing increased spending on unnecessary wars and tax cuts. Republicans, especially under Reagan and George W. Bush, don't seem to mind swiping our national credit card down to a worthless nub. But you'll never hear this from Trump and the rest, who can't stop proverbially humping Reagan's leg while lying about Obama's truly noteworthy economic record.

5 worst right-wing moments of the week — Christmas hysteria comes early for Elisabeth Hasselbeck

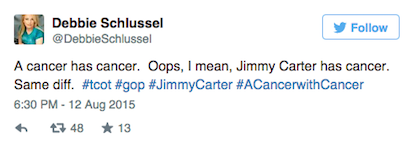

1. True nutcase Ben Carson makes absurd pronouncements that now have to be taken seriously. In a normal world, no one would have to take anything Dr. Ben Carson says seriously. The man has a well-documented history of saying certifiably insane things, notably that Obamacare is worse than slavery and that homosexuality must be a choice because people are raped in prison and come out gay. But ours is not a normal world. Ours is a world in which a billionaire dick with a combover and a fourth-grade vocabulary is the frontrunner in the Republican primary, and a nonsense-spouting TV neurosurgeon ranks in or close to the top five, depending on which poll you believe. So, when Ben Carson declared this week that he absolutely stands by his assertion that abortion is the number one killer of black people—not heart disease as that left-wing conspiracy the Centers for Disease Control has firmly established — there was only one logical response. Aaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhh! OK, we’re calming down now. Breathe. Breathe. "It brings up a very important issue and that is, do those black lives matter?" Carson told one of Fox News’ indistinguishable stooges. "The number one cause of death for black people is abortion. I wonder if maybe some people might at some point become concerned about that and ask why is that happening and what can be done to alleviate that situation. I think that's really the important question." He also accused Planned Parenthood and its founder Margaret Sanger of practicing eugenics on black populations, by placing some clinics in poorer neighborhoods. (We are deep into deranged Alex-Jones territory now.) The word Planned Parenthood uses for what it does is healthcare, and allowing all women, including black women, to have a measure of control over when they have children. Details, details. But Carson’s a contender, and so NPR did a little factcheck on his, errr, facts. Shockingly, they proved to be total lies and distortions. Again, aaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhh! 2. Donald Trump accidentally says something very, very true. It’s Trump’s world, we’re all just paying exorbitant rents in it. This became abundantly clear this week when the Republican frontrunner bullied Roger Ailes into directing Fox anchors and so-called “journalists” not to be mean to the Donald ever again or he will take all his toys elsewhere. Back on her heels, Trump-confronter Megyn Kelly announced she’s taking an unscheduled two-week vacation, and the image of the prostrated Ailes begging Trump’s forgiveness has permanently replaced the former Republican operative-turned-media exec's tough guy image. The Donald emerged very happy—why wouldn’t he? The world continues to work exactly as it should. You get "very rich" (or are born rich, whatever) and your money buys you access to politicians; you throw a hissy fit, even admitting you’re a “whiner” in the midde of it; and an entire network kisses your feet and throws its supposed darling under the bus. You say deeply offensive things about blacks, Mexicans and women, making these utterances abundantly clear despite your limited vocabulary, and you lead the Republican polls week after week after week. Then you do an interview with Newsmax about what will happen when Kelly returns, and say confidently, “She’s going to be fair and good. I’m sure that will happen, and I’m sure Roger will make it happen.” Because that is the way it is, and the way it is supposed to be. Roger will do that, because Donald told him to. Rest assured, Donald Trump sleeps very well at night. 3. Fox Five helps publicize hilariously true ‘Funny or Die’ video about Planned Parenthood’s fantastic services and tries feebly to criticize it. No fair, Kimberly Guilfoyle said in effect after she and her bone-headed colleagues at Fox Five viewed this hilarious, spot-on "Funny or Die" spoof of the recent undercover Planned Parenthood video the right is so trying to make hay out of. Kimberly Guilfoyle said she was speechless after viewing the clip in which women talk about the “pure horror” of dealing with an organization that answers all their questions thoroughly and gives them needed medical care. But she was not speechless. Incoherent, yes, but not speechless. “I don't think it’s okay to make a mockery about women’s health,” Guilfoyle said, clearly not understanding that it is she and her colleagues who harm women on a daily basis. Like this bozo: Gregg Gutfeld: “I mean, what can they do?” he said, readying his zinger. “They are in bed with the devil. It’s called ‘Funny or Die’ but fetuses don’t have that choice because they’re already dead.“ That sounded really good when he composed it in his head. “It’s a shame ‘Funny or Die’ didn’t exist generations ago because they would have been great propagandists for Stalin.” Seriously, who comes up with this guy’s material? It’s fabulous! 4. Elisabeth Hasselbeck gets a jump on fretting about the War on Christmas. It’s August. It’s a gazillion degrees outside. Cars are melting in Europe. But it's never too early to bemoan the War on Christmas. Elisabeth Hasselbeck got a huge jump on her nutty Fox colleagues in firing the season’s first salvo in this non-existent war this week. She was able to do this, because the “War on Christmas” is now defined as any attempt to challenge a state-sanctioned religious display, also known as the separation between church and state. (Another way the War on Christmas and Christians is waged is by not letting people discriminate against gay people, and criticizing lawmakers who try to pass “religious freedom” laws that give patriots the right to discriminate.) So, yeah, the War on Christmas is now a year-round pastime for evil liberals and atheists. Hasselbeck was deploring the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s attempt to have the city of Belen, New Mexico remove a nativity scene on government property, which, like the War on Christmas, is on display year-round. The mayor of Belen is very upset because, as he points out, Belen is named after Bethlehem, birthplace of the baby Jesus. Hasselbeck gave him a sympathetic ear, and encouraged him to fight the good fight. She allowed that this was a case of the War on Christmas comes early, but said he had educated her by showing how it isn’t “just a seasonal issue.” Isn’t that jolly? 5. Right-wing film critic celebrates fact that Jimmy Carter has cancer. Here’s a lovely lady, whose film criticism we’ll be sure to start reading. Her name is Debbie Schlussel, and upon hearing that the 90-year-old ex-president and Nobel Peace Prize winner is gravely ill, the sometime-film critic, sometime-right-wing political commentator tweeted this out:

1. True nutcase Ben Carson makes absurd pronouncements that now have to be taken seriously. In a normal world, no one would have to take anything Dr. Ben Carson says seriously. The man has a well-documented history of saying certifiably insane things, notably that Obamacare is worse than slavery and that homosexuality must be a choice because people are raped in prison and come out gay. But ours is not a normal world. Ours is a world in which a billionaire dick with a combover and a fourth-grade vocabulary is the frontrunner in the Republican primary, and a nonsense-spouting TV neurosurgeon ranks in or close to the top five, depending on which poll you believe. So, when Ben Carson declared this week that he absolutely stands by his assertion that abortion is the number one killer of black people—not heart disease as that left-wing conspiracy the Centers for Disease Control has firmly established — there was only one logical response. Aaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhh! OK, we’re calming down now. Breathe. Breathe. "It brings up a very important issue and that is, do those black lives matter?" Carson told one of Fox News’ indistinguishable stooges. "The number one cause of death for black people is abortion. I wonder if maybe some people might at some point become concerned about that and ask why is that happening and what can be done to alleviate that situation. I think that's really the important question." He also accused Planned Parenthood and its founder Margaret Sanger of practicing eugenics on black populations, by placing some clinics in poorer neighborhoods. (We are deep into deranged Alex-Jones territory now.) The word Planned Parenthood uses for what it does is healthcare, and allowing all women, including black women, to have a measure of control over when they have children. Details, details. But Carson’s a contender, and so NPR did a little factcheck on his, errr, facts. Shockingly, they proved to be total lies and distortions. Again, aaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhh! 2. Donald Trump accidentally says something very, very true. It’s Trump’s world, we’re all just paying exorbitant rents in it. This became abundantly clear this week when the Republican frontrunner bullied Roger Ailes into directing Fox anchors and so-called “journalists” not to be mean to the Donald ever again or he will take all his toys elsewhere. Back on her heels, Trump-confronter Megyn Kelly announced she’s taking an unscheduled two-week vacation, and the image of the prostrated Ailes begging Trump’s forgiveness has permanently replaced the former Republican operative-turned-media exec's tough guy image. The Donald emerged very happy—why wouldn’t he? The world continues to work exactly as it should. You get "very rich" (or are born rich, whatever) and your money buys you access to politicians; you throw a hissy fit, even admitting you’re a “whiner” in the midde of it; and an entire network kisses your feet and throws its supposed darling under the bus. You say deeply offensive things about blacks, Mexicans and women, making these utterances abundantly clear despite your limited vocabulary, and you lead the Republican polls week after week after week. Then you do an interview with Newsmax about what will happen when Kelly returns, and say confidently, “She’s going to be fair and good. I’m sure that will happen, and I’m sure Roger will make it happen.” Because that is the way it is, and the way it is supposed to be. Roger will do that, because Donald told him to. Rest assured, Donald Trump sleeps very well at night. 3. Fox Five helps publicize hilariously true ‘Funny or Die’ video about Planned Parenthood’s fantastic services and tries feebly to criticize it. No fair, Kimberly Guilfoyle said in effect after she and her bone-headed colleagues at Fox Five viewed this hilarious, spot-on "Funny or Die" spoof of the recent undercover Planned Parenthood video the right is so trying to make hay out of. Kimberly Guilfoyle said she was speechless after viewing the clip in which women talk about the “pure horror” of dealing with an organization that answers all their questions thoroughly and gives them needed medical care. But she was not speechless. Incoherent, yes, but not speechless. “I don't think it’s okay to make a mockery about women’s health,” Guilfoyle said, clearly not understanding that it is she and her colleagues who harm women on a daily basis. Like this bozo: Gregg Gutfeld: “I mean, what can they do?” he said, readying his zinger. “They are in bed with the devil. It’s called ‘Funny or Die’ but fetuses don’t have that choice because they’re already dead.“ That sounded really good when he composed it in his head. “It’s a shame ‘Funny or Die’ didn’t exist generations ago because they would have been great propagandists for Stalin.” Seriously, who comes up with this guy’s material? It’s fabulous! 4. Elisabeth Hasselbeck gets a jump on fretting about the War on Christmas. It’s August. It’s a gazillion degrees outside. Cars are melting in Europe. But it's never too early to bemoan the War on Christmas. Elisabeth Hasselbeck got a huge jump on her nutty Fox colleagues in firing the season’s first salvo in this non-existent war this week. She was able to do this, because the “War on Christmas” is now defined as any attempt to challenge a state-sanctioned religious display, also known as the separation between church and state. (Another way the War on Christmas and Christians is waged is by not letting people discriminate against gay people, and criticizing lawmakers who try to pass “religious freedom” laws that give patriots the right to discriminate.) So, yeah, the War on Christmas is now a year-round pastime for evil liberals and atheists. Hasselbeck was deploring the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s attempt to have the city of Belen, New Mexico remove a nativity scene on government property, which, like the War on Christmas, is on display year-round. The mayor of Belen is very upset because, as he points out, Belen is named after Bethlehem, birthplace of the baby Jesus. Hasselbeck gave him a sympathetic ear, and encouraged him to fight the good fight. She allowed that this was a case of the War on Christmas comes early, but said he had educated her by showing how it isn’t “just a seasonal issue.” Isn’t that jolly? 5. Right-wing film critic celebrates fact that Jimmy Carter has cancer. Here’s a lovely lady, whose film criticism we’ll be sure to start reading. Her name is Debbie Schlussel, and upon hearing that the 90-year-old ex-president and Nobel Peace Prize winner is gravely ill, the sometime-film critic, sometime-right-wing political commentator tweeted this out: