Thomas Barr Jr.'s Blog, page 4

June 22, 2016

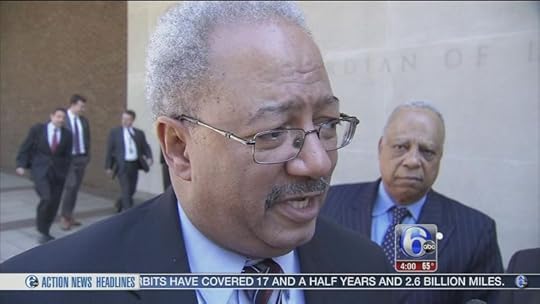

Pennsylvania congressman convicted in racketeering case

Story by AP

A veteran Pennsylvania

congressman was convicted Tuesday in a racketeering case that largely centered on various efforts to repay an illegal $1 million campaign loan.

U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah was found guilty of all counts against him, including racketeering, fraud and money

laundering. His lawyers had argued that the schemes were engineered without Fattah's knowledge by two political consultants who pleaded guilty in the case.

The 59-year-old Democrat had been in Congress since 1995 and served on the powerful House Appropriations

Committee. But he lost the April primary and his bid for his 12th term. His current term ends in December.

Fattah had little reaction to the verdict, but he kept a smile on his face as he conferred with his lawyers afterward.

He will remain free

on bail. A judge set sentencing for Oct. 4.

Prosecutors said Fattah routed federal grant money and nonprofit funds through his consultants to pay back the illegal loan.

Justice Department lawyer Jonathan Kravis said in his closing argument that

Fattah also used federal grants and nonprofit funds to enrich his family and friends.

Defense lawyers acknowledged Fattah might have gotten himself in financial trouble after a costly 2007 mayoral bid, but they said any help from friends amounted to

gifts, not bribes.

Many of them came from co-defendant Herbert Vederman, a wealthy friend who had dreams of scoring an ambassadorship. U.S. Sen. Bob Casey, a Democrat, testified that he never took the pitch from Fattah too seriously, even though Fattah

once bent the president's ear about it. Democrat Ed Rendell, a former mayor and governor, was called to defend Vederman, his former deputy mayor. He said Vederman was qualified for the job and accused prosecutors of cynically misreading the help he lent Fattah.

Vederman helped support Fattah's South African nanny and paid $18,000 for a Porsche owned by Fattah's TV anchor wife.

"The nanny, the Porsche and the Poconos, they weren't part of a bribery scheme," Fattah lawyer Samuel Silver argued in closings.

"Those were all overreaches by the prosecution."

The campaign loan was just one of several schemes prosecutors outlined during the trial. They say Fattah was aided in his endeavors by current and former staffers who ran his district office or the nonprofits;

by Vederman, who now lives in Palm Beach, Florida; and by political consultants Greg Naylor and Thomas Lindenfeld, who pleaded guilty.

The other co-defendants are Bonnie Bowser, of Philadelphia, who ran his district office; Karen Nicholas, of Williamstown,

New Jersey, who ran the education nonprofit Fattah started; and Robert Brand, of Philadelphia, a businessman married to a former Fattah staffer. The jury on Tuesday came back with a mixed verdict for them.

May 23, 2016

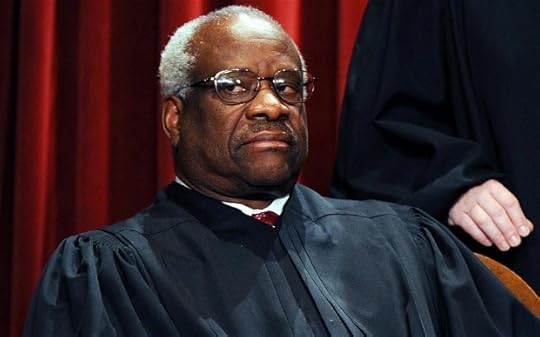

Convicted Gov. Bob McDonnell May Just Convince The Supreme Court He���s Innocent

Story by Cristisan Farias

WASHINGTON — Rarely, if ever, does a felon appealing

his federal conviction get to set foot inside the U.S. Supreme Court.

Bob McDonnell, the former governor of Virginia, broke that general rule on Wednesday as he sat in the courtroom for oral arguments in a case that could not only reverse his multiple convictions on corruption charges, but also redefine what counts as government corruption under federal law.

Luck has been on his side since the outset

of his appeal. And now, even without the late Justice Antonin Scalia on the bench, McDonnell may be able to convince a majority of the justices that he didn’t do anything wrong — and that he shouldn’t spend two years in prison for accepting

lavish gifts and loans from a businessman while he was governor.

This and other acts, his lawyer argued, is conduct that politicians engage in on a daily basis. Should the government get to punish every single instance of it?

“Every

day of the week, politicians write letters on behalf of citizens,” said a concerned Justice Stephen Breyer. He took the lead in searching for a bright line between the kind of conduct that qualifies as true corruption and the kind that doesn’t.

Are those everyday acts by politicians, as a whole, “a crime?” Breyer asked, naturally informed by his lifetime of experience in all three branches of the federal government. “My goodness.”

Breyer, and maybe the court

as a whole, may have an interest in issuing an opinion as narrow as possible — one that upholds the government’s power to prosecute actual corruption, but also one that brings clarity to the law as written, which seems to cast a wide net over

acts that in McDonnell’s view are ordinary politics.

Because the McDonnell case involves the interpretation of federal anti-corruption laws, which use the word “official

acts,” the Supreme Court’s chief role is determining exactly what that means.

If the court comes up with too broad a reading of that phrase, prosecutors could have virtually limitless power to go after even mundane activities —

like a lawmaker who makes a phone call on behalf of her constituent, or an official who arranges a meeting with donors to hear their concerns. But too narrow an interpretation may render the law toothless and make it harder to go after subtler but no

less egregious acts of corruption.

The justices pondered long and hard at what constitutes an illegal “quid pro quo” — donations and courtesies people extend to elected officials in exchange for political favors. Is it the size of

the “quid” that matters for prosecutors or the “quo” that politicians offer in return?

“What’s the lower limit, in the government’s opinion, for the quid?” asked Breyer. He wondered if $10,000, or

perhaps “an evening of trout fishing,” might be sufficient for the kind of gift that might lead to a criminal prosecution.

Justice Samuel Alito, for his part, noted that “gaining access by making campaign contributions is an

everyday occurrence,” which indeed may be “a bad thing.” But this, he said, is “very widespread,” suggesting that in itself it may not be criminal.

Chief Justice John Roberts pointed to a legal brief filed by a broad coalition of government lawyers under both Republican and Democratic presidents,

all of whom sided with McDonnell and cautioned against the pitfalls of an expansive definition of “official acts” — which they said might “cripple” elected officials’ role in a representative democracy.

“I think

it’s extraordinary that those people agree on anything,” Roberts mused, to laughter from the courtroom. “To agree on something as sensitive as this and to be willing to put their names on something that says this cannot be prosecuted

conduct — I think it’s extraordinary.”

McDonnell’s acts didn’t involve campaign donations in the traditional sense. Instead, what he and his wife, Maureen, received were lavish gifts, dinners and shopping sprees from Jonnie

Williams, a pharmaceutical impresario who wanted to seek research assistance and approval from the state for his company’s dietary supplements.

The federal government’s lawyer, Michael Dreeben, argued that Williams’ niceties

— and the governor’s tactics — in turn led to a subsequent indictment and public trial where a jury duly convicted him.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, putting McDonnell’s acts in stark terms, pointed to evidence that there were public

servants at Virginia research institutions who “felt pressured” by the governor’s involvement with Williams and his business interests.

“They were honorable people, obviously,” Sotomayor said. “But the point

is, what do we do with the fact that they perceived that he was trying to influence them?”

She was one of the few justices who seemed sympathetic to the government’s side. Her colleagues, by and large, appeared to go the other way.

“Where

can we find, in your view, the definition of an ‘official act?’” asked Justice Anthony Kennedy, later adding that he failed to see “the limiting principle” for the government’s theory for carrying out these prosecutions.

Breyer seemed troubled by the implication that the government wants to remove all limitations on the “quo” side — what officials do — and what that may mean for future prosecutions.

“My problem is the criminal law as

the weapon to cure” dishonest behavior, Breyer said. He warned that stretching the law’s reach will mean that “political figures will not know what they’re supposed to do and what they’re not supposed to do.”

The

Constitution, in principle, guards against laws that are too vague. But Breyer also worried about another fundamental constitutional problem: an unbound Department of Justice as “the ultimate arbiter of how public officials are behaving in the United

States — state, local, and national.”

“Now, suddenly, to give that kind of power to a criminal prosecutor, who is virtually uncontrollable, is dangerous in the separation of powers,” he said.

At a time when the Supreme

Court is caught in the crossfire of politics over the confirmation battle to replace Scalia, maybe its members will heed Breyer’s words and find a way to rule as sensibly as possible — while understanding that the public doesn’t take kindly

to politicians who abuse the power of their office.

A decision in McDonnell v. United States is expected sometime before the end of June.

May 4, 2016

Supreme Court making it even harder to convict corrupt politicians

Tired of New York’s pay-to-play politics?

Hoping that federal prosecutor Preet Bharara will throw Mayor de Blasio in prison along with, soon,

former state lawmakers Sheldon Silver and Dean Skelos?

Keep hoping. The Supreme Court could make it harder to secure corruption convictions — meaning we’ll have to kick dirty pols out at the ballot box, rather than wait for arrests.

Federal law is clear: A politician can’t take a donor’s money and promise something in return.

Bill de Blasio can’t take money from people who want to ban the horse carriages — and promise to ban the horse carriages in return.

Nor can he take money from people who don’t want to ban helicopter tours — and then protect the tours in return.

So why might the mayor skate when it comes to any pay-for-play shenanigans?

The key is the “in return”

part.

The Supreme Court has long prohibited prosecutors from using timing as evidence: Jurors must believe it is just coincidence if a candidate gets a donation one day and does something for the

donor the next.

Prosecutors need evidence

of an explicit deal, and few politicians are dumb enough to have such a deal.

Now, the Supreme Court could make it even harder for prosecutors to prove a quid pro quo. Under a possible new reading of the law, politicians would be able to make explicit

deals with donors — as long as they don’t act “officially.”

The case in question is federal prosecutors’ conviction two years ago of then-Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell.

McDonnell received a prison sentence for taking

$177,000 in plane trips, Louis Vuitton and Oscar de la Renta clothes, iPhones, a wedding for his daughter and a Rolex, all from a man, Jonnie

Williams, who wanted the governor to promote his diet pill.

The jury was careful — it acquitted

the governor on three counts. But jurors could see the obvious: No politician can take that much money and not know he is being bribed.

Still, McDonnell has a great lawyer, Noel Francisco — who convinced the Supreme Court to take the case.

Last Wednesday, the court heard a novel argument: McDonnell can’t be convicted of bribery, because the things he did for Williams were not “official acts.”

That is, when McDonnell asked researchers at the state University of Virginia

to promote Williams’ drug supplements, he wasn’t acting as governor. He was just acting as any regular person, exercising free speech.

As Justice Elena Kagan observed of one of the governor’s techniques, “so that’s essentially

hosting a party and allowing Mr. Williams to invite some people . . . Why is that an official act?”

Sure. We all have parties in our homes.

Except: The governor has parties in the Governor’s Mansion — not something

anyone can do.

And, as Justice Department lawyer Michael Dreeben noted before the court, the guests from the university weren’t exactly there voluntarily.

The governor appoints the university’s board members. “He sets the budget,”

Dreeben noted. “They know that he’s an important guy . . . The governor is taking every step he can” to signal to

university folk to support this diet drug.

When you’re the governor, everything you do in public

is an official act.

If corruption is only when you take direct action to help a donor, it will be difficult to secure corruption convictions.

A change in the law would affect New York’s recent cases — and chances for future convictions.

Take former state Senate leader Dean Skelos, convicted of bribery in December. US Attorney Bharara’s conviction of Skelos wasn’t mostly based on “official acts,” under the definition the court is considering.

Skelos convinced

Long Island officials to help a company that employed his son, in return for that employment. But Skelos had no legal authority over those Long Island officials. Anyone can ask government officials for help.

The same is true with the mayor. Say prosecutors

do find evidence of a deal between horse-carriage opponents and de Blasio. Any citizen can propose that the City Council consider a bill to ban horse carriages — just as any citizen can encourage regulators to look favorably upon helicopters.

(Silver’s

conviction is more secure. Then again, it took two decades to catch the guy.)

No matter what the Supreme Court rules, we shouldn’t rely on the justice system to govern our politicians.

De Blasio doesn’t have to be found legally corrupt

for the voters to think he is corrupt.

As long as he’s out of office, it doesn’t matter if he’s out of prison, too.