Christine Piper's Blog

January 1, 2022

The 30-day digital detox

For a while now, I’ve been unhappy about how easily I’m distracted by technology. When I get a minute of rest from playing with my kids/doing chores, I instantly reach for my phone. On the rare occasion when I score a couple of hours to write, I open up my laptop and stare at the 78 open tabs (on each of the 3 web browsers I use!) and become mired in research about presents I think I should buy, holidays I should finish organising, articles I bookmarked to read months ago etc. Although I set limits on my children’s screen time, I don’t set any limits for myself. With precious little time for my own work and self-care these days, I need to make the most of what I have.

That’s why, this January, I’m doing a 30-day digital detox, as outlined by Cal Newport in his book Digital Minimalism. For me, this means no web browsing (unless it’s for essentials). For good measure, I’m going to swear off social media for a month too (no more scrolling through Instagram while sitting on the toilet). Email isn’t a source of distraction for me, so I’m going to keep checking emails at certain times of the day (10am, lunchtime, 3pm). WhatsApp sits in a grey area – the conversations about the pandemic and politics are definitely distracting, but it’s also the chief way I organise play dates and catch-ups with friends. One solution would be to turn off all notifications and only allow myself to check WhatsApp at certain times of the day (10am and lunchtime, for example). Or I could go hardline and delete the app completely and either use my husband to relay messages to me, or ask my friends to contact me via text message instead. TBC…

There are two reasons for the month-long detox:

1. To break the compulsive urge to check my screen at the slightest hint of boredom (guilty as charged!).

2. To get back in touch with what I actually value in life.

As Cal Newport writes: “The alluring noise emanating from our screens provides an easy distraction from the bigger questions about what really matters; what we want to do with [our] limited time here on earth. This month-long reprieve provides the space needed to revisit these questions, and through both self-reflection and experimentation, form some tentative answers.”

Newport says it’s important to plan ahead to ensure you fill the void left by technology with higher-quality activities, so here’s what I hope to do in the time I’d normally be wasting on my phone/laptop:

Reading books and magazines,

Engaging with my children,

Craft projects (e.g. knitting and origami),

Meditating,

Going for walks,

Journalling,

Thinking deeply about my novel.

Thinking deeply about my novel is what I’m really striving for. With a frenetic toddler and lots of cancelled daycare days recently due to sickness/Covid exposure, I rarely get time to dive deep and solve story issues related to plot or theme. When I do, it takes me a while to “get in the zone”, and if I get side-tracked with “research” and go down an internet rabbit hole, I lose my focus and the allotted time is lost. Emails, surfing the web and watching videos are examples of shallow work that pull me out of deep concentration and hinder my ability to dream up big ideas and hit my flow state (check out my blog on this).

I’ve been thinking about doing a digital detox for a while, but a turning point came when I read that we wake up with a finite reserve of willpower each day (which is why people who want to get fit are told to exercise first thing each day, and why writers are told to write in the mornings). Each decision we make (should I buy the dancing unicorn for my niece or something else?) chips away at that reserve until we get “decision fatigue” and revert to doing the easiest task on our list – e.g. organising a rental car for our summer trip instead of doing our most important work. This is why Obama only wears blue or grey suits – “I’m trying to pare down decisions. I don’t want to make decisions about what I’m eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make.” If I cut out my ability to browse the web, I won’t be tempted to make those hundreds of decisions that seem so important, but really aren’t.

The idea behind the digital detox is not to give up these technology habits forever, but to only reintroduce the ones that truly add meaning to your life and can’t be achieved any other way (e.g. many people say Facebook is a great way to stay in touch with people, but you can also do that by picking up the phone and having a chat), and to reintroduce them with limits – e.g. only using them at a certain time of day (installing an app such as Freedom to block websites at certain times is a good way to manage it), or having a separate computer for web browsing. There are laws that limit the sale of alcohol before midday on Sundays in New York, and many countries ban junk food advertising to children, so why not limit other addictive behaviours such as surfing the web?

Newport has been described as the “Marie Kondo of technology”, and it’s true that his approach fundamentally mimics hers: dump everything out of your digital toolbox and only add back the stuff that “sparks joy”.

So, starting from tomorrow (January 2), I’m deleting all browsers and social media apps from my phone and laptop. If I really need to use a browser I’m going to annoy my husband and use his phone/laptop instead.

Come February, I’ll weigh up the good and the bad and decide what to reintroduce and with what kind of limits. Stay tuned.

March 8, 2021

Find your flow

While drafting my second novel, I sent instalments every fortnight to a writing coach to help me stay on track. Although I had a few days each week to write, without fail on deadline day I’d only have two or three pages written instead of a complete chapter. So I’d hunker down for a day of writing. Five o’clock would come and go, then 6pm. At 8:30pm, after eating dinner and putting my child to bed, I’d begrudgingly return to my desk and push on with the chapter, all the while flicking to Google for “research”. That’s when the internal tug-of-war would begin:

I should just cut my losses and send it now, apologising for how short and poorly written it is … one part of me would say.

And then: No, you can do this! Just keep going and it will be done by midnight!

Followed by: Ugh, I’m so tired. My writing is crap. Why bother? I just want to go to bed.

This would go on for a while. Sometime around midnight, however, I’d get a second wind and vow to finish the chapter, even if I had to stay up all night. In making that commitment, something in my brain would shift. I would become singularly focused on getting to the end of the chapter. No procrastination, no doubts about my writing. I’d write fast and furiously, words pouring out of me like sweat in midsummer. I’d hammer out the final sentence and look up at the clock: 3am. I’d written two days’ worth in a few hours.

This happened Every. Single. Time. For 16 months until I had completed the first draft.

When my writing coach would get back to me with feedback a few days later, more often than not she’d comment that “the writing really picked up on page X”—exactly the spot where I’d entered a state of hyper focus.

I’d heard about the “flow state” before, but my regular experience with it got me thinking: was there a way to enter flow without the pressure of a deadline (and preferably before midnight)? I did some digging, got a bit obsessed, and this is what I found out.

What is FLow?Finding your flow. Getting into the zone. Doing deep work. Whatever you want to call it, it’s an optimal state of consciousness when mind and body merge and we perform at our peak mental/physical capacity. It’s accompanied by feelings of ecstasy and euphoria, triggered by feel-good neurochemicals: dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, anandamine, oxytocin and endorphins. The flow state usually lasts for 1.5-2 hours. We feel at one with the universe and our sense of time becomes distorted—sometimes slowing down, at other times speeding up. It’s characterised by rapid-fire decision making, happening so quickly that there’s no analysis—we do things almost automatically. That’s because parts of the pre-frontal cortex (“the inner critic”) shut down during flow. Our ability to think critically diminishes, but productivity increases manifold.

Some people may be naturally prone to flow—especially those who score high on personality tests for conscientiousness and openness to experience (yes and YES!), and low on measures of neuroticism (not me). Although it’s typically seen as the domain of sportspeople or performing artists (e.g. concert pianists, jazz musicians), anyone can experience flow. Chances are you already have. Ever been immersed in a video game? Or lost yourself in thought when on a walk, or chatting with a friend, or cooking dinner? Not all experiences of flow are the mind-bending, earth-shattering kind. The flow state is a spectrum, with some episodes more intense than others.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FLOWFor centuries, the flow state was confined to the realm of religious experiences. It wasn’t seen as quantifiable or measurable. However, in 1901, William James interviewed numerous successful people such as Leo Tolstoy, Martin Luther and Lord Tennyson and found they all experienced mystical episodes during periods of intense concentration, indicating that positive transcendent states could be triggered by secular activity. In 1915, James’ student Walter Bradford Cannon identified the fight-or-flight response. This would be used to explain the physiological basis of so-called mystical experiences. In 1964, Abraham Maslow studied college students and the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt and Albert Einstein, and used the term “peak experiences” to describe “moments of highest happiness and fulfillment”.

In 1975, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term “flow” after interviewing hundreds people about when they felt/performed their best. He found that flow is experienced by people from all walks of life: factory workers, farmers, dancers, surgeons, chess players. The most enjoyable moments in people’s lives were also the times that were challenging and painful. In his later work on creativity, he became fascinated by artists who, when absorbed in their work, disregarded the need for food, water and sleep.

how to enter the zone“Write first thing in the morning” is an oft-used writers’ maxim. Authors such as Haruki Murakami, Barbara Kingsolver and Toni Morrison all get cracking before the sun rises, at 4am or 5am. Even Hemingway liked to start writing “soon after first light” (no guarantees he was sober, though). The benefits of a morning writing session are twofold: you’ll ensure you’ll get it done if you do it first thing, and you’re more likely to slip into the flow state soon after waking. Here’s why: the flow state exists between the conscious and subconscious states, so you’re closer to it just after sleep.

Set the challenge level high. A tendency to procrastinate indicates the task isn’t challenging enough. If you aim to work at the upper limit of your capability, or even 5% beyond what you think is possible, you’re more likely to reach a state of hyper focus. Give yourself less time to do things, or try to do more in the time allotted, for example: write 500 words an hour instead of 200.

Engage in mindful activity. Certain types of activity are known to trigger flow states—ones that engage the mind and body without pushing them to their limits. Good activities include model building (try putting together an IKEA purchase, or helping your kid with their school project), painting, crafts (Iowa Writers Workshop director Lan Samantha Chang knits while brainstorming ideas), puzzles, journalling, yoga, meditation, rock climbing, going for a run, walking in nature and gardening. Activities that involve the hands are particularly useful flow triggers—traditional craftspeople report the highest levels of flow in their daily lives. Take this quiz to determine your flow personality and the best trigger activities for you (you have to provide your email address to access results, but it’s easy to unsubscribe from marketing emails): www.flowgenomeproject.com/flow-profile

Breathing exercises can also help you find your flow. Try inhaling for 3.5 seconds, and exhaling for 7 seconds. Do this for 5 minutes and you’ll nudge your body into a relaxed state that’s more susceptible to flow. Box breathing is another effective technique. Inhale for a count of four, hold your breath for a count of four, exhale for a count of four, then keep your lungs empty for a count of four. Repeat for 5 minutes.

Feeling daunted about a big task? Anxiety can negatively affect creativity, but it’s easy to flip anxiety into excitement—just say “I am excited” three times out loud.

Stop when you’re still excited, ready to pick things up again the next day. Hemingway and Gabriel Garcia Marquez often ended their writing sessions mid-sentence.

Embrace the “struggle phase”. Getting into flow always starts with a period of struggle. Accept it as part of the cycle and persist for 20-40 minutes—but not much longer. Stubbornly sitting at your desk for hours when you’re not in the mood won’t help you get things done. Take a break instead.

Know that finding flow takes practice. Like a muscle, you’ll gradually get there quicker and go deeper each time.

YOUR perfect flow-y dayYour perfect workday should include 1.5 to 2 hours of uninterrupted time doing your most important task; 25-45 minutes of flow-trigger activity; 5 minutes of journalling a problem and trying to find solutions to previously outlined problems. You could follow this with a second flow period of about 1.5 hours. After a period of flow, follow with some rest and relaxation for 25-45 minutes. Most learning takes place in the recovery phase. Finish your day with 5 minutes spent writing out a clear list of goals/your schedule for the following day. Don’t try to schedule your downtime (i.e. weekends) as it could diminish your enjoyment. You should also try to include two 4.5-hour periods of rumination each week.

I’m a night owl (as is my partner) with two young kids—double whammy for a writer!—but if I manage to find the Holy Grail of a perfect workday, it would look something like this:

7AM Rise. Meditate (20 minutes). Write Morning Pages (a method from The Artist’s Way). Eat something light and drink tea.

8AM Hit my desk for a solid 2 hours on my most important task, usually my novel. Aim to write 700 words.

10AM Do yoga, or take a walk in nature.

11AM Do less important tasks that don’t involve web surfing (my Achilles’ heel), e.g. checking emails.

12PM Lunch.

1PM Nap. Or, if I’m not feeling tired, meditate (20 minutes) then spend 25 minutes on a flow trigger activity such as a puzzle or origami.

1:45PM Journal for 5 minutes.

1:50PM Second writing session.

3:20PM Finish for the day. Before bedtime, spend 5 minutes planning my next day.

Let’s be frank: I’ve never had a day as described above. With a toddler and a 6-year-old, I don’t get to my desk until 10 or 10:30AM (on the few days I have childcare), and I have to stop working sometime between 2:30 and 4:15 (depending on my kids’ schedules). I do my best to protect 1.5 to 2 hours in the morning as my golden hours to write my novel, and try not to check emails or phone messages or surf the web (apps such as Freedom help with that). I aim to write 600 words, but 300-400 is more like it.

The origami-at-my-desk thing didn’t work, despite toting around packets of pretty paper and various origami instruction books for months. What has been beneficial is getting outdoors—weather permitting, I like to do my morning writing (with pen and paper) in Centennial Park or somewhere along the Bondi-Bronte coastal walk. There’s nothing like the swish of trees, the chirrup of insects, and the hiss and roar of waves to put me in a positive and contemplative mood.

After a hiatus of a few years, I’ve recently returned to regular meditation and writing Morning Pages (scheduling them into my day the night before has worked wonders). Both have had huge impacts on my mood, energy and the depth of my writing—I dive deep into theme and character motivation in my Morning Pages and those mental leaps show in the novel pages I subsequently write.

Have I been able to enter the flow state without the pressure of a deadline? Not every day, but once or twice a week if the conditions are right, I have. It usually happens when I’m well-rested, have avoided all distractions and it’s soon after I’ve woken. Some mornings I’ll start at 9:30 and be on a streak until midday. I’ve written over a 1000 words at those times.

My biggest takeaway from all the research I’ve done is not to force myself to sit at my desk until I hit my word count, as I used to. I take a break, go outside, do some exercise or a trigger activity and then try again.

FURTHER READING/WATCHINGThis excellent 6-hour video course presented by Steven Kotler will explain everything you need to know about flow. It costs $99 but is often discounted.

In Deep Work, computer scientist Cal Newport argues the case for disconnecting from the internet, emails and other distractions. He provides different models for incorporating deep work into our lives.

The definitive book by the grandfather of flow, Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi provides a good overview, but doesn’t offer practical advice on how to get into flow.

Check out Csikszentmihalyi’s Ted Talk on “Flow, the secret to happiness”.

From Where You Dream: The process of writing fiction outlines Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robert Olen Butler’s unique method for entering flow (which he calls “dreaming”), which involves rising at 4am and not reading anything (not even a packet of food!)/watching TV/listening to radio before he starts writing.

www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20190204-how-to-find-your-flow-state-to-be-peak-creative

thriveglobal.com/stories/finding-flow-in-the-unconscious-conscious

Please sign up to my newsletter for more writing advice!

January 10, 2021

To outline your novel, or not? That is the question.

In her 2008 lecture to creative writing students at Columbia University in New York, author Zadie Smith divided novelists into two camps: Macro Planners and Micro Managers. According to her logic, a Macro Planner “makes notes, organizes material, configures a plot and creates a structure — all before he writes the title page.” While a Micro Manager “start[s] at the first sentence of a novel and… finish[es] at the last.” Smith is firmly the latter. “When I begin a novel there is nothing of that novel outside of the sentences I am setting down… In one day the first twenty pages can go from first-person present tense, to third-person past tense, to third-person present tense, to first-person past tense… and so on… Yet, while all that is happening, somehow the work of the rest of the novel gets done.” When writing On Beauty she spent almost two years reworking the first twenty pages, but when she finally settled on a tone, the rest of the book was finished in five months. And because she edits as she writes, she only needs to do one draft.

It’s the old Plotters v Pantsers divide: those who write from meticulously detailed plans, as opposed to those who wing it as they go. So the question the novice scribe must grapple with is: Which kind of novelist am I?

The truth is, the vast majority of novelists fall somewhere in the middle. When it came to writing my first novel 12 years ago, I had no idea where to start. After all, I’d never written a novel before. I asked my mentors at the University of Technology, Sydney (where I was doing a Doctor of Creative Arts degree) how to write a novel, but I mostly got vague answers and the repeated refrain: “There’s no formula.” Liars, I thought. They just don’t want to tell me.

But now, having published one novel and finished the first draft of another, I know they were right. There really isn’t a secret formula (except, perhaps, persistence).

One of my doctoral supervisors, Debra Adelaide, told me to throw away a book about novel structure, and any other book that tried to impose a blanket rule on novel-building. She explained:

“When you finish writing your first novel, you think you’ve figured out how to write novels. But when it comes to your second, you find that none of the same rules apply. Each novel is different, just like each child is different — you can’t approach them the same way.”novel #1 — no plan, no outline… no idea

I started with a topic (I wouldn’t recommend starting with a topic unless it’s something you’re really passionate about, as the story could end up feeling hollow): Japanese immigrants in Australia. My mother is Japanese and immigration/identity is a common theme in my work. I was initially interested in the Japanese pearl divers in Broome (some of whom were interned during the war), but my supervisor at the time, Delia Falconer, suggested I focus on the internment of Japanese civilians in Australia during WW2, because no one had ever covered it in fiction before (coincidentally, a year before my novel was published, Cory Taylor released My Beautiful Enemy, about a young Japanese internee’s relationship with an older Australian guard). I did a few early chapters, which Delia wisely said I should put aside (i.e. Your writing sucks – which, at the time, was true) to instead concentrate on research.

I stared at a blank page for weeks, writing and rewriting the first few paragraphs, then one day a voice popped into my head. It was the voice of an old Japanese man looking back on his life, and it was a voice full of regret. I wrote a chapter and Delia said, yes, that’s good. From that point, the creative process involved working out why that Japanese man came to be so full of regret. I quickly worked out that he was a Japanese doctor who’d been working in Broome and then interned during the war in South Australia, but I felt there was a much deeper source of regret in his past that I hadn’t discovered yet. For most of the first draft (which took me 3 years to write), I didn’t know what it was. I just wrote with this ghostly trauma, this hole, on the periphery. While on a writing retreat at Varuna in the Blue Mountains, I suddenly remembered reading about some bones being unearthed in Japan that were linked to Japan’s wartime atrocities. I jumped online and searched for it and started reading about Unit 731 – a secret unit of the Japanese army that developed and implemented biological weapons and which were used in northern China in the 1930s. It fit with the timeline of the doctor, and everything just seemed to fall into place.

When I was two-thirds of my way through the first draft, I got stuck: I knew how the novel would end, but I didn’t know how to connect the middle scenes to the end. I assumed you had to write scene by scene in the order they’d appear in the novel (Ann Patchett recommends this approach in The Getaway Car). But Debra said, “If you know what the end’s going to be, just write it!” So I did. And once I’d written the end, I could clearly see what was needed to get me from B to C. I sat down and wrote a list of scenes left to write – and from that point I started working from an outline.

ON SECOND THOUGHTS…

For my second novel, I struck upon a story that really grabbed me: two Australians travelling by cruise ship to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, who try to steal a pair of Queensland lungfish on board. Wanting to avoid the pain of the three years I spent writing the first draft of After Darkness without a plan, on the advice of fellow Aussie author in NYC and lady of many talents, Georgia Clark, I decided to write a detailed outline first. I wrote a 20-page outline, breaking down my novel scene-by-scene, which I then sent it to freelance editor Sarah Cypher for finetuning.

With the editor’s feedback, I reshaped the outline, concentrating on character motivation, backstory, agency and conflict. Then I launched into the writing, aiming to finish the first draft in a year. For this I engaged the help of another freelance editor, Lisa Poisso, who became my “writing coach”, offering feedback on fortnightly instalments. My aim was to power through the first draft, making adjustments as I progressed but not spending much time revising, or else risk losing momentum. In this way, I wrote 140,000 words over 18 months and got 95% of the way through my first draft. I had to stop as I was about to have another baby, but I was happy to have a hiatus at that point: the style of my novel had changed over the course of the draft so I knew I’d have to do a big rewrite in the future, and I wanted to keep the ending unwritten in order to have something fresh to explore in the second draft.

the verdictPlotting vs Pantsing. Macro vs Micro. Writing from an outline vs winging it. Which approach worked better? Neither. There were pros and cons to each.

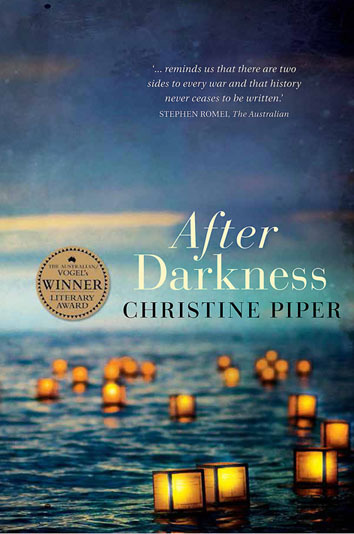

The first draft of After Darkness was written over more than three years. It was soul destroying to be working on something for so long, not knowing where it was going, constantly wondering whether I’d have to abandon it in the end (I did throw away tens of thousands of words). But once I had that first draft down, the next only took me six months, and the third draft two months. Not long after that, my novel was published.

With Lena & Esmond (the working title of my second novel), the process of writing the first draft was much more enjoyable as I knew where it was heading. But my initial vision didn’t completely translate to the page – the pompous omniscient narrator I’d wanted ended up feeling forced and anachronistic, and the characters seemed wooden in the first half of my novel; there’s not much magic there. I now face a big rewrite, which will take another year.

For my next novel, I hope to do something in between. Instead of a detailed outline, I’ll follow the rough arc of the story and major plot points, and I’ll spend more time brainstorming character motivations and backstory early on.

But I suspect writing novels never gets easier. There’s no golden formula, after all. Those years of pain writing thousands of words you’ll inevitably throw away are essential to unearth the gold. I’m reminded of a Haruki Murakami quote: “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional” (What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, 2007) – such a quintessentially Japanese ethos if there ever was one! But they’re wise words to the fledgling novelist: embrace the pain and don’t let it get you down.

March 2, 2016

Old story, new beginnings

Hard to believe it’s been almost two years since my last post. In that time, I did a bunch of print, radio and TV interviews for After Darkness (which has sold thousands of copies and been nominated for several awards, including the Miles Franklin). I wrote a newspaper article about the WW2 internment of Japanese civilians in Australia, and recorded a radio segment about the mixed-race Japanese internees and their struggle with identity. I gave a talk in New York and in LA about my work. I started a script about a foreigner living in Greenwich Village. I wrote a short story about a teenager yearning to escape rural boredom and his drunk dad. I attended Tin House writer’s workshop in Portland, Oregon. I started researching a new novel. Oh, yeah, and I had a baby.

About the new novel… Although I’ve been thinking about it/researching it for more than a year now, it’s still in the R&D phase (yes, I’m a slow starter, but I’ve also been preoccupied with looking after a tiny human) – the most exciting phase for me, so full of hope and glory (without the weight of reality)! It’s about the journey that two Australians take to attend the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933. One character is an amateur naturalist involved in the transfer of aquatic wildlife to the fair, and the other is making the journey separately. It’s an adventure, and also a thwarted love story. I’m writing it partly because I wanted to write something different to After Darkness – something lighter, that doesn’t involve me being in a traumatised and wilfully obtuse man’s head for months on end. In this new novel, I’ll also be tackling the slightly daunting omniscient third-person mode of narration.

The idea for the novel came to me laterally. I’ve always loved early Art Deco posters, especially the world’s fair posters, and I was looking at buying prints of the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: A Century of Progress. As I trawled the internet, I thought: Wouldn’t it be good to set a novel at the Chicago World’s Fair? There would certainly be plenty of drama and spectacle that would make great narrative fodder. I already had two characters in my head, and I felt that at least one of them was Australian, so I jumped on the internet to research links between Australia and the Chicago World’s Fair – and bingo! I discovered that Taronga Zoo in Sydney donated lots of aquatic wildlife to the fair in 1933.

So why the picture of the fish (top)? He’s pretty special – he’s an Australian lungfish known as Granddad. He’s one of the original fish that Taronga Zoo donated to the Chicago World’s Fair, and – wait for it – he’s still alive in Chicago today! Yep, he’s thought to be the oldest aquarium fish in the world; his age is estimated to be about 100 years old (he was already fully grown when he was donated in 1933). He outlived the lungfish that came with him in 1933, and all attempts at breeding with him have proved fruitless.

Me with Granddad in the background.

Kris and I visited Granddad at Shedd Aquarium in Chicago in May. The lovely Karen Furnweger in the editorial/content management department (and author of a book about the history of Shedd Aquarium) furnished me with some vital information about the transfer of the fish from Australia to Chicago, and took me on a tour. Apparently Granddad usually wallows at the bottom of the tank and hardly moves (like most grumpy old men), but on the day we visited he was very active: swimming, taking gulps of air at the surface and foraging for food. A good omen, perhaps? Granddad and the other lungfish are of special interest to the amateur naturalist in my novel. I loved the idea of this ancient creature (lungfish are known as “living fossils”) taking centre stage at a fair that’s all about futuristic innovation – the clash of the old and the new. Fingers crossed Granddad stays alive until the publication of my book!

(There’s also an eerie parallel with my own life: when I was 6-7 years old, my father worked in Tokyo as assistant trade commissioner, overseeing the transfer of koalas from Taronga Zoo to Tama Zoo in Tokyo. My sister and I have fond memories of that time: living in an apartment in Shibuya, getting lots of koala merchandise (stuffed toy, koala backpack), pretending to eat lacquered koala poo… Yes, one of the merch items was lacquered koala poo.)

And in something of a coincidence, Hollywood is all abuzz about Scorsese’s new film portraying the serial killer H.H. Holmes who killed dozens of people at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. It’s based on the bestselling 2003 novel by Erik Larson: The Devil in the White City. Similar to my novel, but different enough that my book won’t seem like a tired idea by the time it comes out… I hope!

May 1, 2014

A shot in the dark

(This piece I wrote about winning the 2014 Vogel's Literary Award was first published on The Wheeler Centre website.)

I got the email at five am. Four fifty-seven, to be precise. I had just returned home from a very long day at The Writers Room in New York, where I have a desk. An hour earlier, working alone in the vast room used by journalists, scriptwriters, memoirists, essayists, academics, poets, short story writers and novelists, I had finally completed the second draft of my novel. It was several weeks overdue, and I still had another two essays and an introduction to write before I could submit my Doctor of Creative Arts thesis to the University of Technology, Sydney. But I was happy with the novel, which was the most important part. Exhaustion and euphoria chased me as I took the lift downstairs, unchained my bike and began the twenty-minute journey home.

The streets of New York are never quiet, not even at four am. As I pedalled through the East Village, college kids stumbled along the road and barkeeps shuttered their premises before turning home. A mild September wind slicked over me. It was that perfect time of year when heat and humidity wane yet the nights are still warm.

I mounted the steep slope of Williamsburg Bridge. On my three-gear bike, I was panting and reduced to a crawl, while lithe-limbed hipsters on fixies sped past me. Just before I reached the crest of the bridge, I paused to look back. Manhattan, in all its shimmering glory. A city full of possibilities. My husband I had had moved to New York six weeks earlier, two more hopefuls chasing a dream. It was our second time trying. Six years earlier, we’d arrived in the Big Apple but had failed to establish ourselves. This time, I’d won a green card through the Diversity Visa lottery program, and my husband had arranged a job transfer. Our fortunes had changed.

The sky was the colour of slate by the time I arrived home. I showered and prepared for bed, looking forward to a long, rejuvenating sleep. Then I remembered an email I had to send. I crossed to the kitchen bench and flipped open my laptop, then noticed an unread email at the top of my inbox. From someone named Annette at Allen & Unwin. ‘I wonder if I could arrange a meeting with you to talk about your Vogel's entry?’ she wrote. I froze.

I first heard about The Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award when the Helen Demidenko/Darville scandal hit the newspapers in 1995. I was sixteen at the time – a bookish Year 11 student with dreams of being a writer. I’d like to enter that award one day, I thought. Over the years, I read many of the winning titles, and they always reaffirmed my desire to enter. I took creative writing classes during my undergraduate degree, and wrote a novella for my honours project. Then I began working full time, and hardly ever found the time for creative writing.

Sometime during my late twenties, I realised that if I didn’t do something soon, I’d miss my chance to enter the award. Soon afterwards, I was accepted into a Doctor of Creative Arts degree at the University of Technology, Sydney, where I was mentored by Debra Adelaide and Delia Falconer. I began researching and writing a novel about the Japanese civilian internment experience in Australia – a topic I was interested in as my mother is Japanese (although no one in my family was interned). I thought I’d finish it within three years. Four at the most, giving me time to enter the award at least twice before I hit 35. After Darkness took me almost five years to create. When the May 2013 deadline drew near, I was midway through the second draft. I was 34. It was my last chance.

Despite my best intentions to deliver a polished second draft, in the weeks leading up to the deadline, I was feeling unwell and was unable to work on the manuscript as much as I’d hoped. I submitted it to The Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award five minutes before midnight, utterly disappointed with what I’d done. ‘I’ve blown my one chance,’ I told my husband.

Then four months later, I got the email. A few minutes before five am. I didn’t get the long sleep I’d hoped for that morning – I didn’t sleep at all. The possibilities kept churning in my mind. Was I shortlisted? Had I won?

It was another two days before I finally talked to Annette, the publisher at Allen & Unwin, who confirmed that I had won. Several stressful, hectic months followed as I struggled to complete my thesis and then immediately began revising After Darkness for publication.

But I didn’t know that then, as I stood in the kitchen of our Williamsburg apartment, day breaking around me. All I knew was hope, and the joy of chasing dreams.

After Darkness is available from all good bookstores in Australia/New Zealand. See www.christinepiper.com/after-darkness/

March 31, 2014

2014 Calibre Prize: The evolution of an essay

The monument to the unidentified bones

After a long break from blogging as I finished my PhD and novel, I am happy to return with some good news: I won the 2014 Calibre Prize for an Outstanding Essay.

I’m very grateful for the generous support of Australian Book Review and Colin Galvin SC. There are so few opportunities to publish writing of this kind, so I’m delighted that my lengthy, Japan-focused essay will reach a wide audience, without the usual editorial constraints. This important issue has remained buried for too long.

‘Unearthing the Past’ traces a springtime walk I took through suburban Tokyo in 2013, on the trail of some mysterious bones discovered in 1989. I met lawyers and activists involved in the struggle to identify the remains and expose the horrors of Japan’s wartime past. I was drawn to the topic because of the shocking nature of the crimes, and the fact that very few people know about it today. Despite the efforts of activists to recognise the victims, not much has changed. The controversy surrounding the bones reflects the larger, ongoing debate about Japan’s contested war memories.

The essay features in the April 2014 edition of Australian Book Review, in print on newsstands and via digital subscription ($6 for one issue, or $40 annually). (Last year’s winning essay can be read for free online, but I don’t think mine will be similarly available. I’ve included a 700-word extract below.)

I wrote ‘Unearthing the Past’ for my Doctor of Creative Arts degree at the University of Technology, Sydney. The themes of memory, silence and testimony tie in neatly with my novel, After Darkness. I’d always wanted to write a long, narrative-driven, creative non-fiction piece, and took the opportunity to do so with my doctorate. It was by far the most difficult single chapter of my thesis to write. The writing alone took seven weeks full-time (not including the research that preceded it, nor the time spent interviewing key people), and involved late nights and even a few tears. I transcribed eight hours worth of interviews and spent $1000 on interpreters. To get my head around all the historical developments, I wrote a six-page timeline, starting with the 1925 Geneva Convention banning the use of biological warfare and ending with the 2012 death of former Army Medical College nurse Toyo Ishii.

My essay is by no means perfect or unputdownable (hey, it’s more than 7000 words long), but I hope it goes a small way towards redressing the silence that has surrounded this issue.

My biggest thanks go to the activists who have spent years campaigning and raising awareness about this dark chapter of Japan’s past: Yasushi Torii, Shigeo Nasu, Kazuyuki Kawamura and Norio Minami (see below). (If you can read Japanese, head to the website for the Association Demanding Investigation Into the Human Remains).

And congratulations to the five other shortlisted essayists, Ruth Balint, Martin Edmond, Rebecca Giggs, Ann-Marie Priest and Stephen Wright – I look forward to reading their submissions in upcoming issues of Australian Book Review.

Yasushi Torii, president of the Association Demanding Investigation Into the Human Remains Found at the Former Army Medical College Site

Shigeo Nasu, director of resources at the Centre for Victims of Biological Warfare

Kazuyuki Kawamura, secretary-general of the Citizens for the Investigation of World War II Issues

Norio Minami, the lawyer involved in the case to prevent the cremation of the remains

An excerpt:

On 7 July 1989 the air was thick with heat in the Toyama district of Tokyo. Tsuyu, the rainy season, had just ended, leaving the atmosphere dense. At the former government health building location, a large pit was being dug for the new National Hygiene and Disease Prevention Research Centre. The workers buzzed around the site, their foreheads glistening in the sun. The mechanical digger plunged deep into the earth, scraping against rock as it brought up a mound of dirt. Something pale shone through the soil. At first, it looked like pieces of ceramic. On closer inspection, the workers realised it was human bones.

Twenty-five years later, their identities are still unknown.

*

In a city famed for skyscrapers and neon lights, Toyama is a quiet pocket in an urban jungle. Situated in the heart of Tokyo, only thirty minutes by foot from the world’s busiest train station, Shinjuku, it is bordered by busy Meiji Road at one end and the prestigious Waseda University at the other. In between lies residential housing, several schools, a public library, a Buddhist temple, the National Centre for Global Health and Medicine, and acres of leafy parkland. Hundreds of years ago, a lavish garden built by a feudal lord occupied the area. Now, at least a dozen public housing monoliths crowd the edges of the park.

Like most of metropolitan Japan, Toyama is full of contradictions. It is a place where the indigent and the upper middle class live side by side. In this suburb, an ancient Shinto shrine dedicated to gods of war is a short walk from the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, committed to exposing wartime violence and enabling justice for victims.

My first visit to Toyama was on 1 March 2013. The grass was tawny and the ground was thick with dry leaves, but I occasionally spied tiny green buds on the branches of trees. Mothers pushed prams through the park and up gently sloping alleys crowded with dwellings. Now and then, a door creaked or the murmur of a television sounded from within.

The idyllic snapshot of suburban life is worlds apart from Toyama’s former identity as a hub of military operations during the Asia–Pacific War. Seventy years ago, the neighbourhood was home to a mounted regiment, the Toyama Military Academy and the Tokyo Army Medical College. The latter was a collection of buildings where the Imperial Army’s medical élite, academics, and politicians gathered to share research and hold secret talks about Japan’s expansion into East Asia.

The area’s unusual past might have stayed relatively obscure but for the accidental unearthing of the bones in 1989. News of the discovery of at least thirty-five human skulls prompted speculation. Some wondered if they were the victims of unsolved murders, while others thought they were the casualties of wartime raids or the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake. Kanagawa University history professor Keiichi Tsuneishi was one of the first to suggest ties to Japan’s covert biological warfare program during World War II. Tsuneishi, whose earliest work on the subject was published in 1981, knew of a special department known as the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory located within the Army Medical College. He was quick to draw links to Unit 731, the secret unit of the Army Medical College that developed biological weapons and experimented on living humans, starting in 1932 in the Japanese colony of Manchuria, and later in Guangzhou, Beijing, and Singapore. The unit conducted tests on bubonic plague, anthrax, cholera, typhus, smallpox, botulism, and poison gas. Infected victims were vivisected to observe the progress of disease – sometimes without anaesthetic. Test subjects were referred to as maruta, or ‘logs’, originally as a joke because the Unit 731 compound was disguised as a lumber mill, then the term persisted.

About three thousand people were directly killed in the experiments at the Unit 731 compound alone. Japanese forces also deposited wheat, rice, and cotton riddled with disease-infected fleas near communities, and released typhoid and cholera into village wells. The total death toll resulting from the spread of disease is estimated to be between 250,000 and 300,000.

*

As the daughter of a Japanese immigrant, I have long been drawn to stories about Japan. In some ways, unravelling the mystery of the bones is my attempt to decipher a culture that is at once both familiar and unknown to me. Although I have lived in Japan several times since my childhood, I have always remained an outsider. Confronting the silences of Japan is a way of piecing together my cultural heritage. So I went to Japan to meet the unofficial guardians of the bones, concerned citizens who have no direct connection to the remains, but who have taken it upon themselves to see that justice is served …

(Subscribe to Australian Book Review if you’d like to read more.)

October 11, 2012

Habits I wish I had a year ago

Now that I'm staring down the barrel of completing my doctorate/novel, I've developed several good habits that make me think: "Why, oh why, didn't I do these years ago?" For the sake of other writers, and as a memo to my future lazy self, I thought I'd share them here. Write every day, first thing in the morning

Write every day, first thing in the morning

Last year I attended a workshop run by time management guru Hugh Kearns. At one point we split into small groups to discuss our approach to study and writing. Two women in my group were already academics, having completed their PhDs while working full-time and with several small children. I wanted to point out that I thought they were in the wrong workshop—the workshop for insanely driven high achievers was down the hall. The first woman said: "When I was finishing my PhD, I'd get up at 4 or 5am to do my writing, because with the kids it was the only time I had free." The other woman nodded sagely: "Sometimes even 3am." 3am?! Holy *#^@! While that's taking it a bit far in my books (I'm someone who'll happily sleep in till 10am), writers from different disciplines say the same thing: write every day, and write first thing in the morning. Why first thing? Because, not only will it mean you can't put it off, the quality of your writing will be freer and more creative then. Your thoughts are less likely to be fettered by what Julia Cameron calls your "internal censor". Pulitzer Prize-winning fiction author Robert Olen Butler advises 1–2 hours of morning writing 6–7 days a week. "If you let two or three days go by [without writing], it's as if you've never written a word in your entire life," he writes in "From Where You Dream: The Process Of Writing Fiction". He even advises against reading the newspaper, watching TV news—allowing any sort of conceptual language to enter your head—until you've done your morning writing. In "Turbocharge Your Writing", Hugh Kearns and co-author Maria Gardener recommend setting aside "two golden hours" every morning. I take this approach. I get into uni (late, about 10.30am, but I'm working on that), and the first thing I'll do is set my SelfControl timer (see below) for two hours. I won't check emails, open an internet browser or eat lunch until I've done two hours of fresh writing. Sometimes, if I'm really itching to read my emails, I'll say to myself: "Just one hour." More often than not, I'm quite happy to extend that to two or even three.

Pomodoro Technique

Pomodoro Technique

I first heard about this anti-procrastination technique two years ago. It involves breaking down tasks into 25-minute blocks of time, or "Pomodoros", with a mandatory five-minute break in between. A timer rings when the 25 minutes is up, and you have to stop what you're doing and take a break. It's supposed to help you focus on the task at hand, and the regular breaks keep your mind fresh. I heard about it, and thought: That wouldn't work for creative writing, that wouldn't work for me. A year or so later, I came upon it again in the context of psychologist Robert Boice's research on effective writing habits. His research found that regular, planned writing sessions resulted in not only a greater output than "binge writing", but regular writing also resulted in more creative ideas. That got me thinking, and feeling guilty, because I'm all about binge writing. I'd convinced myself that pulling all-nighters was the best way to come up with truly creative ideas. Seems I was wrong! Boice believes inspiration is the result of habitual writing, rather than the idea that precedes it. Since then I've been a total Pomodoro convert, and I've written 65,000 words in 9 months. Sure, a lot of that won't end up in the final draft (and yes, I do occasionally write crap to fill the rest of the Pomodoro), but I still have a helluva lot more useful material than if I binge wrote. What I love about it most? It's free. Download the 45-page booklet here, and read it cover-to-cover. It'll teach you how to take charge of distractions, both internal (eg your urge to Google "tonsil stones") and external (phone calls, colleagues bugging you, birthday cakes in the office, etc). It will help you break down big tasks into achievable goals, and to accurately estimate how long it will take to achieve them. I use this great (and free) Focus Booster electronic timer to time the 25-minute blocks. If you do only one of the things I mention on this page, do this one! (Well, do this in combination with the first point about writing every day.)

SelfControl app

SelfControl app

This is a simple app for Macs that doesn't require much explanation. And boy, is it a godsend. Best of all, it's free! To set it up, type in a "blacklist" of banned websites (my list includes every single Google-related page, eBay, Etsy, ShopStyle, news and social media websites). Then when you set the timer for anywhere between 15 minutes and 24 hours, you'll still have internet access (eg for Dropbox and other research-related activity) but you won't be able to access those tempting websites. Be careful, because once you set the timer, nothing—not even turning off the computer—will stop the block on those sites (that's where smartphones and outdated search engines such as Yahoo! and MSN come in handy). Kris commented the app is actually the opposite of exercising self control, but as Paul Silvia points out in "How To Write A Lot": "The best kind of self control is to avoid situations that require self control."

Scrivener

Scrivener

This is a sophisticated program that's perfect for working on longer pieces—novels, scripts and doctoral theses. It's US$45 from Literature & Latte, which I think's a bargain, given I use it every day. It's also very stable. I've been using it for eight months and have still only scratched the surface in terms of its features, but my three favourite functions are: snapshots, composition mode and corkboard. Snapshots allows you to easily save different versions of the same document, instantly cutting out the fifteen different Word docs I have for a single scene. In composition mode, you enter a full screen in which other open programs are hidden so that you can concentrate on your writing. And corkboard gives you a macro view of your document, allowing you to move different scenes around.

Another great tool that needs little explanation. Working on both my computer at uni and my computer at home, I spent the first 2.5 years of my candidature emailing documents to myself and doing my head in in the process. I've found Dropbox especially useful to update reference entries on EndNote. I'm on a $100 per year storage plan, but it's free for smaller sizes. (Sign up to Dropbox for free using this link, and we both get extra space: http://db.tt/KA1khwMY)

I don't want to harp on about this too much for fear of sounding like the leader of a cult, but I started meditating earlier this year and it's helped me enormously—and in ways I didn't imagine. I became interested in vedic meditation (aka transcendental or mantra-based meditation) for the creative breakthrough it can provide. I heard about a friend's friend who's a musician and who often writes complete songs in one go after a vedic meditation session. Five months after doing a course, I'm not sure it's had a huge impact on my creativity—I'm still stuck on several plot holes (but it has allowed me to step back and make drastic changes I wouldn't have made as easily before). But there are two areas I have definitely reaped benefits: stress relief and maintaining focus. In regards to stress relief, I no longer sweat the small stuff—running 10 minutes late or forgetting someone's birthday doesn't bother me anymore. I have a slightly more positive outlook overall, too, which has in turn helped productivity. The second area it's helped me with is maintaining focus. When my meditation teacher told me: "You'll find that even though you're spending 40 minutes a day meditating, you'll have more free time than you did before," I thought: "What a load of bollocks." But, sure enough, in the first week of meditating I noticed I was finishing tasks quicker than usual, because I was less distracted overall.

There you go—hope that helps. And let me know what handy habits you've picked up to help your writing.

July 4, 2012

Stranded: the evolution of a story

Everyone remembers their first time. The first time a story they wrote is accepted for publication.

Everyone remembers their first time. The first time a story they wrote is accepted for publication.

Even though, as a journalist, I'd had fifty-odd articles already published, when my first short story was finally accepted for publication I felt a rush of emotion. Was I happy? Yes, because writing fiction is much more personal than writing a commissioned article. But most of all I was relieved. I finally had a publication to add to my pathetically brief literary CV, and I was now eligible to apply for all those grants and retreats only available to published authors. It immediately validated all the hours I had spent slaving at my desk. Because the sad truth is that no one (friends, family, colleagues) takes you seriously as a writer of fiction until you have something published. A book would be better, but I'm working on that!

Getting my first story, Stranded, published has not been easy. I first wrote it in 2008 when I enrolled in a Gotham Advanced Fiction Writing course while I was living in New York. I started with an image I'd had in my head for a while: while riding on a train in Sydney years earlier, I sat next to a young Asian man in a suit. He spread his hands across the briefcase on his lap, and I remember the beauty of those hands. They were delicate, manicured—a piano player's hands. I was struck by the intimacy I felt staring at his hands—a moment of intimacy between strangers in a public place (although he never acknowledged me, nor do I think he even realised the weirdo next to him was staring at his hands).

Even in its earliest stages, the story I wrote had very little to do with the real-life moment that sparked it—although the theme of intimacy between strangers remains. Stranded opens with a Japanese businessman discovering a blonde hair on his suit one day. He removes it, goes to work, and is surprised to find another (or the same?) blonde hair on him later that day. The second discovery causes the businessman to reflect on the affair he'd had with a young woman who'd prostituted herself for money and gifts (a phenomenon known as enjokosai in Japan), making him think about how the affair had abruptly ended.

I did a rough draft, got lots of helpful feedback from my Gotham classmates, did a revision that my teacher, Michael Backus, thought was a big improvement, but then I was stumped. A lot of people had a problem with the ending. I like story endings to be suggestive rather than didactic, but it's hard to achieve without coming off sounding vague and pointless.

I put it aside for several months, and over the next few years I went back to it again and again, reworked it and sent it to other people to read. The writing became clearer and more polished, and a lot of people thought it was good. But the problem of the ending and the significance of the hair in my story came up again and again. I wanted the repeated appearance of the hair in Stranded to allude to the randomness of life, but it seems that, even though life is random, in fiction, randomness doesn't work. I eventually put my artistic concerns aside, bit the bullet and added a plot line that explained the appearance of the blonde hair.

In 2011, I started to send it out to different publications and competitions in Australia. I thought I had a good shot at some of them, so was crestfallen when the rejections rolled in, one after another. Even though I'd heard from other now quite famous authors that they also had dozens of rejections before they were finally published, I was still crushed when it happened to me. The failures felt personal—it was as if they were rejecting me.

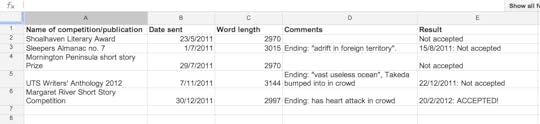

At the same time, I was editing the story and writing different endings. I started to keep a spreadsheet to keep track of all the publications/competitions I was sending it to. It seemed like I had sent it to twenty places before it was finally accepted, but in reality I only sent it to five:

The ending was a persistent problem, and I now realise it was because I wrote the story without a "message" in mind. I shied away from writing a short story with a message or moral, because it struck me as fake, and I wanted readers to make their own interpretation of the story. But now, after reading a lot of guidebooks on writing and critiquing a lot of stories, I realise that nearly all good stories have some sort of a message—but the best ones have a message that's hidden in the story and isn't obvious.

I finally decided to write an ending that cast a sort of moral judgement on the Japanese businessman, Mr Takeda. I personally preferred an earlier ending I'd written, and Kris agreed with me, but I decided to take a risk. I sent it the inaugural Margaret River Short Story competition minutes before the 5pm (in WA) deadline on New Year's Eve 2011, and didn't think about it for a while. I had toughened up as a writer, and no longer expected success. So I was delighted to get an email seven weeks later saying my short story had been shortlisted in the competition, and would be published in an anthology put out by Margaret River Press. A couple of weeks after that I received a phone call saying that I'd been awarded second place! Interestingly, the editor who chose the stories and awarded the prizes, author and Edith Cowan University academic Richard Rossiter, commented about my story that "in spite of the ending"... there is "little sense of moral judgement for Mr Takeda's transgression":

Set in Japan, Christine Piper’s Stranded is a tightly written account of an affair between an older man, Mr Takeda, and a (much) younger woman, Naoko. He pays her for both sex and company. They have little in common except for one thing. As Naoko says, ‘We’re two loners, aren’t we?’ The title brings together the erotic elements of the affair—a strand of blonde hair, representing the sort of woman who is probably not available to Mr Takeda—and the conclusion. Mr Takeda is on his way to see Naoko with an expensive Christmas gift, a Hermès bag. He is very excited by his purchase and the anticipation of seeing his young lover, but the world changes when he catches sight of himself in a display window: ‘a greying man holding a brightly wrapped gift’. This is a very economical story with a strong sense of character and place. It interrogates the values of appearance and surface, with little sense of moral judgement for Mr Takeda’s transgression—in spite of the ending.

READ IT

You can read my short story, Stranded, in the fiction anthology Things That Are Found In Trees and Other Stories (Margaret River Press, 2012). It's only $13.99 plus $2 shipping: www.margaretriverpress.com/catalogue/fiction/things-that-are-found-in-trees-and-other-stories

Or you can buy it in eBook format for $4.09: www.kobobooks.com/ebook/Things-that-found-trees-other/book-3J6kiRvkb06dLR5v9hh__g/page1.html?s=Dr9IM1dqb0KcFjoZyQpxEQ&r=1

LAUNCH

I'll be doing a short reading at the Sydney launch of Things That Are Found in Trees and Other Stories.

Where: Gleebooks (upstairs, 49 Glebe Point Rd, Glebe)

When: Saturday July 7, from 4pm

RSVP online: www.gleebooks.com.au/default.asp?p=events/2012/jul/Launch-A-Taste-of-Margaret-River-an-afternoon-of-food-and-wine-and-literature_htm or phone: 02 9660 2333

What: Double launch -- the fiction anthology Things That Are Found in Trees and Other Stories & the cookbook Chefs of the Margaret River Region... because fine fiction and fine food go so well together!

February 29, 2012

A giant leap

IMG_1697

This is an old article, but one that I've been meaning to write a post about for some time—and I thought today's Leap Day was as good a time as ever:

Jumpology: The Theory of Jumping Shots

The New York Times article is about '40s and '50s fashion and portrait photographer Philippe Halsman, who photographed the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, Salvador Dali and Albert Einstein. He was famous for his philosophy of jump photography—which he called "jumpology"—in which he asked his subjects to jump and captured them while airborne.

Halsman, who died in 1979, said, “When you ask a person to jump, his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping, and the mask falls, so that the real person appears.”

IMG_1784

Although I would like to say that a well-considered philosophy was behind our decision to take jumping shots, the truth is much more prosaic: while on an overland tour between Kathmandu and Lhasa in 2007, two young Danish girls in our group inspired us to start doing them. At first, I didn't like doing them—they took a lot of effort, and seemed gimmicky. But seeing the photos made me change my mind: not only did the jumping pose make aesthetically striking images, but the subjects' facial expressions were eye-catching, too. Joy, surprise, determination and ecstasy were writ large in varying degrees upon each person's face. And the fact that it is difficult to look miserable while jumping added to the photos' appeal.

CP_IncaTrail_LR

As we took more photos, it became clear that each person has their own unique way of jumping, their own unique style and facial expression that they repeat unselfconsciously time and time again. Mine is a sort of knees backwards, floppy starfish pose coupled with an expression of absolute glee. And so it seems there's truth in Halsman's theory that in the act of jumping "the real person appears"—a glimpse of one's true self.

And so began a tradition of taking jumping shots in every destination we have travelled to—and we have been many places since:

IMG_4391

IMG_7627_LR

IMG_2299_LR

IMG_0158_LR

IMG_7040_LR

NYC_Tiff_Paul

IMG_1713_LR

IMG_9604

IMG_3102_LR

January 14, 2012

The Artist's Way and all that jazz

double_bass_findedgespic

I recently started the 12-week creativity program, The Artist’s Way, by Julia Cameron (http://www.artistsway.com/aw.html). Well-known in creative circles (the book has sold about 4 million copies), it’s designed to help artists of all disciplines (musicians, illustrators, dancers, filmmakers, writers – or people who aspire to be artists) unlock their creativity. As well as weekly exercises, the two main components of the program are:

1) Morning pages: Keep a notebook and pen beside your bed, and every morning after waking up write three pages in longhand, stream-of-consciousness-style. You can write about anything. It’s designed to free you up (turn off your “internal censor”) and to get negative thoughts out of your system. The writing starts off as irrelevant drivel, then slowly good ideas start to creep in.

2) Artist’s date: Once a week, go on a “date” by yourself to stimulate your creative sensibility. It doesn’t have to be in your creative discipline, and it’s probably better if it isn’t. It can be anything from going to the movies, going to an art gallery, going to a book reading, spending an afternoon taking photos or hearing an artist talk – the most important thing is that you do it alone.

As a friend pointed out, the tone of The Artist’s Way is very California New Age-y (Cameron refers to “God” a couple of times, although I think she means it in the spiritual, higher creative power sense). But the principles she outlines are effective.

I started the program years ago when I was doing a creative writing thesis for my honours degree and was massively stumped. After a few weeks of doing the morning pages I finally overcame my writer’s block. Unfortunately, once the creative juices were flowing again, I abandoned the program and never went back to it, until now. I’m determined to stick until the end this time – and hopefully even make the morning pages a daily habit.

Today is Day 6. I went on my first artist date today, visiting the Australian Centre for Photography (www.acp.org.au) and then Brett Whiteley Studio (http://www.brettwhiteley.com/). I’ve loved Whiteley’s sensual paintings since high school. I still remember walking into my Year 8 art class and finding the teacher crying because Brett Whiteley had been found dead earlier that morning. I over-estimated the amount of time I would spend at the galleries, so after an hour, I’d run out of things to do. The exhibitions were good, but my visit hadn’t sparked any creative insight – no thoughts or feelings to stoke the creative fire. I felt dejected, as if I’d started up a conversation and it had gone exactly nowhere.

I decided to give up and head home. As I walked down Devonshire Street, I heard a melody. I realised a live jazz band was playing nearby. Not since the SIMA gigs at the Strawberry Hills Hotel stopped in the early 2000s had I seen jazz at a pub in Sydney. Turns out that The Clarendon Hotel, where the band was playing, has jazz on Sundays, but today’s gig was part of the Jazzgroove Summer Festival (http://jazzgroove.com/).

I crossed the road to get a closer look. The place was packed. I joined the throng standing on the sidewalk. The band, The Waples Brothers with Jackson Harrison, were fantastic – sax, double bass and drums, with Jackson on keyboard. Their lovely, rich, uptempo sound was the perfect antidote to a muggy afternoon.

The music unleashed something within me, setting off a chain of loosely linked memories and thoughts. The last time I had been to a live improvised jazz gig was when I was living in New York, four years earlier. Kris, Ghita (visiting from Canada at the time) and I visited St Nick’s (http://stnicksjazzpub.net/), an old jazz haunt on 149th St in the Sugar Hill area of Harlem, a venue that has been around for more than 50 years. It was an amazing place – the old dame at the bar, the locals that had been going there for years, and the tourists who’d heard about it through word of mouth (us). The musicians were so skilful and played so intuitively, it seemed as if they’d played together their whole lives. They played for hours, long into the night.

As I stood on the sidewalk outside The Clarendon, thinking about the time I was listening to jazz in New York, it struck me that association is such a big part of what art is about: presenting the familiar in a way that makes us see things anew and have deeper insight into life.

Creativity is said to come from the meeting of the conscious and the sub-conscious. But to reach that point is tricky, as our rational (conscious) mind too often takes charge in day-to-day life. That’s why people often have creative “eureka” moments when they’re in the shower, out walking or on the train. That’s why, when I sit down with the intention to plough ahead in my novel, nothing comes out. That’s why so many artists (eg Brett Whiteley) turn to drugs or alcohol to help their creativity. The thing is, creativity can’t be forced. You have to distract the conscious mind, trick it into doing another low-level task, in order to give the sub-conscious mind the space to bubble up. That’s also what the morning pages and artist dates are about – freeing up your mind from rational thinking and allowing it to wander and make unusual associations.

Another thing that came to mind as I listened to live jazz was the short story “Sonny’s Blues” by James Baldwin (http://aj-classnotesdiscussion.blogspot.com/2011/03/sonnys-blues-by-james-baldwin.html). Apparently it is often taught in English literature classes in the States, but I hadn’t heard of it till I did a summer course at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in May 2011. Our teacher, Lan Samantha Chang, said it was one of her favourites. I finally got around to reading it a few months ago. It’s a flawed but powerful piece. Fantastic dialogue and thematically rich, I just wasn’t sure what it was about. (If you’re thinking of reading it: it’s long, so set aside an hour to do it justice.) It left me with a certain emptiness, but at the same time it stayed with me for a long time, which I think is generally a good indicator of the merit of a piece of art.

“Sonny’s Blues” has an obvious connection to jazz. Set in Harlem in the 1950s, it’s about a young man (the narrator’s brother), Sonny, determined to become a jazz musician, despite the naysayers all around him. Sonny gets caught up in the Village music scene, becomes an addict and spends some time in jail. The story ends with an evocative scene in a jazz bar, with Sonny jamming with his old jazz buddies. Reading it over now, the final scene strikes a chord as it is as much about the artist’s struggle with creativity as it is about the cycle of poverty, suffering, freedom, redemption – the individual’s battle against the vicissitudes of life.

“All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it. And even then, on the rare occasions when something opens within, and the music enters, what we mainly hear, or hear corroborated, are personal, private, vanishing evocations. But the man who creates the music is hearing something else, is dealing with the roar rising from the void and imposing order on it as it hits the air. What is evoked in him, then, is of another order, more terrible because it has no words, and triumphant, too, for that same reason. And his triumph, when he triumphs, is ours.”

So that was it, my first artist date. And what a great date it turned out to be.

IMG_8808_Berlinfindedgespic