Jan Carson's Blog, page 23

December 24, 2014

Tinned Peas

I was going to post a festive something or other for Christmas Eve but I’ve decided to post this short story instead. There’s been a lot of talk in the news about food banks in the run up to Christmas this year. Whatever side of the debate you fall on, it’s hard to ignore the fact that food poverty is currently an enormous and ongoing problem throughout the UK. This is a quick short I wrote about what life is like for some of the many people who are now reliant on food bank donations. It’s very easy to make assumptions about the kind of people who use food banks and yet, in the last few years volunteering with Storehouse, I’ve become more and more convinced that there isn’t a “kind of person” who uses a food bank. I’ve heard so many different stories from service users, some of which I’ve struggled to relate to because they are so far outside my own range of experience, others which sounded scarily like parts of my own story.

I’m so proud of my brother as he’s worked incredibly hard over the last few years to set up and run Storehouse. They’re helping to fight food poverty in Belfast every week and have managed to maintain an ongoing emphasis on dignity and care for the service users they provides for. This Christmas hundreds of people in Belfast will be able to enjoy a fresh Christmas dinner and enough groceries to keep them going over the holiday period because of the hard work of Storehouse volunteers and the kind donations of those who’ve given so generously to meet the need. You can check out the amazing work Storehouse do throughout the year at www.storehousebelfast.com and if you don’t live in Belfast, track down a similar project and get involved. The problem isn’t going away and people are going hungry while the politicians sit around discussing how to tackle it.

Tinned Peas

At night the table slid sideways. Chloe and her father grabbed a handful of plywood each and tugged until the melamine top came away from itself, dividing like a pair of elevator doors and reconnecting to form the barest beginning of a bed. The table-bed left splinters in Chloe’s fingers and a solitary skelf of plywood embedded in the flesh between her wrist and elbow which -making a bolt for the bone- had ghosted itself to become a pale grey punctuation mark, ill-defined as an underwater fish. Weeks later, bored in maths, Chloe went at her arm with the sharp end of a compass but the skelf was deeper and more determined than she’d anticipated. She bled a thin border of blood dots, like Morse code, crawling across her textbook until the girl who sat next to her, sliding, as the term progressed, further and further away from Chloe’s damp wool smell, seized the compass and hissed, “are you a mentalist, Chloe? There’s places for ones like you that cut themselves.” Chloe tried to explain about the bed which was also a table but everyone else in class had separate places for sleeping and eating.

At first, building her own bed felt like camping or Christmas. In the weeks directly following her mother’s departure everything seemed an occasion of sorts. Normal service succumbed to the rules previously governing birthdays and family funerals: take-away meals and early morning nights, her father, briefly and uncharacteristically inclined towards affection. Each small indulgence settled like a layer of loft insulation over her father’s sadness until it was impossible to read the shape of his loss buried beneath all their anxious bravado. They were giddy, Chloe and her father, high as helium gas on the effort required to reassure each other.

“We’re moving into your Granda’s old caravan in the back field,” her father said when they could no longer afford the rent. “It’ll be a right laugh.” His smile was a spade, dig, dig, digging an old-fashioned trench against the very many looming things which threatened them now from all directions and below.

Fathers, Chloe knew from television, were meant to leave. Mothers, were designed to stay behind, sweating it out with tears and sometimes drinking. This was the proper order of disintegration. She felt ashamed for her father who had not managed to get out the door quick enough. Instead of saying, “why?” and “no way!” or “are you some kind of halfwit?” Chloe had said, “great Dad, sure I’ve always wanted to live in a caravan. It’ll be like going on holidays.”

It had been nothing like going on holidays. For weeks they kept the pretence running like telegraph wires between their old life and the caravan. Bolstered by the success of making it from morning breakfast to midnight, relatively intact, her father would joke with Chloe as he turned their table into a bed, tossing pillows at her head like padded punches, making a circus of shelving the condiments and placemats which stood guard over their daytime table. They slept top to tail. “Like tinned sardines,” he said, though they’d never been the sort of family who ate sardines. The stench of his feet were Chloe’s first and final taste each day. They bookended her dreams which were sweat-thick full of empty mothers and portable homes. In the morning their bed returned to its natural state.

They lived like this for months, stacking and shuffling the caravan’s furniture to preserve the illusion of normalcy. By March her father was no longer able to stomach the effort of pretence. The bed remained a bed from one morning to the next; sheets rising and pooling like pudding meringue; pillows shrivelling in a defeated line beneath the windowsill. They ate dinner on the sofa balancing picnic plates- still scum-smeared with the previous night’s meal- perilously on their knees and drank from mugs, stained the damp-sand colour of a North coast winter. Spoons served for knives, forks and occasionally ladles, saving on the washing up. Chloe could manage most everything but meat with a spoon and, with the price of winter lingering like a stubborn aunt all the way through the Twelfth fortnight and beyond, they could rarely afford meat. They were weekend carnivores, favouring fish fingers with red sauce, or bacon, black burnt and gritty from the ancient frying pan. “Here now, Chloe, a wee slice of bacon for you,” her father would say as he arranged rashers like quotation marks around a puddling dollop of baked beans. “You’ll know we’ve hit rock bottom when your old da has to turn vegetarian”.

Routine kept them rotating from one end of the week to the next. Round and wearily round with nothing to show for the triumph of arriving at another weekend, intact.

On Thursdays Chloe’s father left early for the job centre. On Friday evenings he returned late, his hands crease-cut from lugging plastic bags out of town. Each week on a Friday, they claimed two bags from their local food bank but, without dietary restrictions or religious affectations to act as leverage, had no say whatsoever over the contents. Arranging the bags on the floor at Chloe’s feet they worked their way methodically through their haul: dry pasta, toothpaste, UHT milk- which tasted like soap on cornflakes but lasted weeks- sandwich spread and snot green sauerkraut swimming in the jar, tinned ravioli, chocolate Hob Nobs, toilet roll and shower gel, (though the caravan’s cramped shower had long since expired so matters of personal hygiene were now restricted to a damp flannel and a weekly excursion to the local swimmers, where the unemployed could bathe with the chlorinated regulars for fifty pence an hour).

“No vegetables again, Clo,” her father would say, hands stomping across the shelves as he unpacked the food bank groceries. “They never give you vegetables. I always ask, but there’s never anything fresh.”

Chloe would dig deep into the carrier bag, rummaging past the plastic packs and cardboard wrappers in the nervous hope of locating a carrot, a pear or shock-haired head of broccoli. She’d make a tremendous show of excavating the groceries, holding her face like a pregnant pause, like the night before Christmas, never once expecting anything more perishable than a long-life loaf. All this and other excesses were for her father’s benefit. Lately he’d begun to look like a dropped stitch.

Her hands, fumbling through the week’s groceries were not the hands they’d been six months previously. Her skin, no longer blushing from Sunday roasts and lunch box mandarins had paled the sap grey colour of old dishwater. Her nails were raggedy and both hands, a scribbled network of raised blue veins. Her eyelids, when she occasionally had the chance to examine them in the school bathrooms or, upside down, in the back of a soupspoon, were bruised and almost transparent like baby bird wings held to the light.

There were never any vegetables. Neither Chloe nor her father expected them. Other things had also disappeared with her mother: unprovoked laughter and packed lunches, Eastenders omnibus on a Sunday and a pair of china figurines, only slightly chipped, which had once belonged to the Great Grandmother in Larne. Chloe knew not to mention these things aloud with words. Her father could no longer cope with anything more serious than the farming supplement. Recently she’d begun to keep a list for her own records. Allocating each loss a number and filing it between the pages of her homework diary leant significance to Chloe’s smaller losses so, quilted toilet paper and properly braided hair did not fall forgotten between the towering grief of losing a parent, a house and a working television set.

Chloe had always been a logical child, ill-inclined to misplace things or create a scene when an explanation would suffice. Chloe had, her mother always said, come out of her belly, already frowning; too serious to settle into the name Melanie, which they’d pre-picked for their new daughter. She enjoyed maths, physics and documentary programmes on all television channels, but had never been able to understand the appeal of children’s fiction.

She was not without a measured dose of emotion. Beginning on the morning after her mother left, Chloe had cried for a solid week, careful to do so in damp places such as the garden, (which was, in line with long-established local customs, sodden for eleven months out of twelve), and the shower, (which had yet to be sacrificed with the house and its eight other furnished rooms). In the right conditions, with water falling, it was impossible for her father to tell she’d been crying. Otherwise, Chloe would not have permitted herself to bother. After a week she’d run out of energy for tears though there had been times, even recently, when the cold showers at the swimming pool had triggered a reaction in her eyes, unstoppable as any August downpour. This, Chloe assumed, was something to do with chemical reactions and the chlorine which permeated every inch of the leisure centre.

On Friday evenings when the bags arrived her father seemed to fold into the caravan’s cramped larder, a little more diminished with each item of own-brand, non-perishable, kindly-donated food. Chloe longed for the luxury of a shower in which to cry, uninterrupted, like an ordinary little girl. The air around their collapsible table grew shrill as sugar glass. Even when the gas bills arrived and left unanswered and grandparents came to deliver sanctimonious ten pound notes in envelopes, these Friday evenings were always the worst and thinnest moments of their entire week. Chloe, crouching on the floor between her father and the groceries, could pinch the tension between finger and thumb. It felt like a packet of already broken, value brand biscuits. The rest of the weekend was hers to mend or shatter. Christ himself would have had more room to manoeuvre.

“There’s peas,” she’d cry, fishing the tin out of the bag and holding it above her head like a consolation prize. “Peas are vegetables too, Dad.” There were always peas; sometimes one tin, sometimes two. On good weeks there was also sweetcorn and baked beans, though never the real brand; only the supermarket equivalent.

Her father, moving from the floor to perch wearily on the edge of the table, which was always a bed now, would take the tin from Chloe’s hand and turn it gravely round, clockwise or anti-clockwise, as if looking for a point of entry.

“Peas are vegetables,” he’d mutter, as if anxious to convince himself. “Tinned though; not as fresh as you’re used to Clo; not as good for you.”

His eyebrows, flatlining across his forehead, would form the same frown Chloe saw every time she peered into a reflective surface. It was reassuring to see her own concern, mirrored.

“Peas are my favourite, Dad,” she’d say. It was a lie of course, but neither the worst nor largest Chloe had offered lately. “Fresh peas would be better, but tinned ones are grand for now.”

“They are?” he’d ask, optimistic as a two storey elevator. When Chloe agreed, wholeheartedly with teeth, the roof of the caravan would rise slightly, no more than half a cautious inch but just enough to release the glowering pressure. Tinned peas became the pillars holding their weekends up.

Each time they had peas for dinner, boiled or briefly nuked in the microwave oven, Chloe kept two or three aside, tucking them into the ear of her pocket. On Thursdays, when her father left early for the job centre Chloe wrestled the bed into a table, arranging the condiment bottles and placemats across its melamine top in some semblance of routine. Then, creeping under the caravan, past the gas canister, the tow bar and the tinny steps they used for ascending and descending their own front door, she planted her saved peas in neat rows, two inches beneath the glarry muck. They would, she knew, take weeks to sprout, longer still to produce fresh peas. But Chloe was a sensible girl, capable of persevering through March, April, May and enough stolen peas to dye the pocket of her school skirt a particularly violent shade of lawn.

On the first Friday evening in June, encouraged by the feeble, infant shoots, periscoping through the topsoil Chloe dragged her father from his grocery bags, hunkered him in half and squeezed him beneath the caravan’s floor. There was a taste in her lungs like cut grass and next summer.

“Look Dad,” she said, nudging at a tiny pea plant with her baby finger, “I planted some peas so we’ll have fresh vegetables.”

“Those are weeds, Chloe,” he replied, too tired to approximate disappointment. “Vegetables won’t grow under here. It’s far too dark.” As if to prove a point, he scooped the fledgling plants out of the soil and threw them far down the field into the early evening drizzle.

Chloe lingered for an hour beneath the caravan, listening to the heaviness of her father as he stacked tins and packets and, for her benefit, turned their bed into a table. She allowed herself to cry for it was as damp beneath the caravan as anywhere she’d recently been.

December 21, 2014

December Round Up

December is always a really busy season at the Ulster Hall and this year has been no exception. We’ve been up to our ears in Carol Services, festive Christmas movies and all manner of “special” festive events, (i.e. regular events adapted to include mulled wine and Reindeer jumpers). I’m pretty knackered and just about ready to put Fairytale Of New York out to pasture for another year and move on to a different season. In the midst of all the bedlam I’ve had a couple of nice wee publications and wanted to let you know about them.

Earlier in the year I collaborated with a visual artist and old friend Sarah Poots who, although based in London has been exhibiting her beautiful painting in the CCA Derry for the month of December. Alongside other writers including the poet Jack Underwood I got to contribute a short story, “Hibernation” written in response to Sarah’s exhibition, “Can Be Used Over and Over.” The pamphlet of writing which compliments the exhibition is absolutely gorgeous and it was a further treat to get to road trip up to Derry to read at the exhibition launch last Friday. If you’re in or around Derry before the New Year, be sure to pop into CCA and check out the exhibition.

I was also delighted to have a piece of flash fiction, “Jesus Haircut” included in RTE’s short story collection, “100 Words, 100 Books” published last weekend by O’Brien press. All the stories included in the book are between 100 and 200 words long and are an eclectic bunch and a great way to spend a coffee break. There’s a snippet from my story below and the full collection can be purchased from O’Brien Press’ Website www.obrien.ie

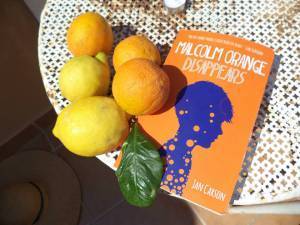

This weekend I was also really chuffed to have Malcolm Orange Disappears included in two different Best of 2014 Books. Please check out these excellent blogs and maybe pick up some of the other books nominated here as they’ve definitely made a dent in my intended reading for 2015 list. (www.headstuff.org and www.americanauthor.tumblr.com). Massive thanks to Orla McAlinden and Lizzie Maguire for their kind words and ongoing support throughout this whirlwind of the year. And now, back to the writing, with a full ten days away from the Hall over Christmas I’m intending to have a first draft of Roundabouts ready to start editing by the end of January, (I might also sleep a little and catch up on my novel-reading and maybe have a few drinks by the fire and watch a few episodes of Casualty and eat some good cheese and…..)

December 10, 2014

Oh, Belfast

Yesterday morning I woke to the news that Northern Irish film organisations were facing up to 50% cuts to their annual budgets. It was not the nicest news to wake up to. Cinemagic could well be affected, also Belfast Film Festival and the QFT; all organisations I’ve been extremely impressed by in the last couple of years. It’s probably wrong to have favourites but I have to admit that I was most upset by the impact on the QFT. I did a quick count and I reckon we’re now into our 16th year of relationship. The QFT has never once judged me when I turn up alone on a Sunday night, with my pyjamas on under my parka and wish to watch art house movies and drink hot chocolate without talking to anyone. The QFT has never once corrected me for my mispronunciation of foreign film titles nor asked why I consistently book my tickets for the wrong date, (the font is very tiny on my iPhone). The QFT has, over the years, returned to me lap tops, (twice), mobile phone, (once), pull on suitcase, (honestly), and my favourite hand knit Kurt Cobain-inspired scarf, (after some six weeks languishing in lost property), and never once insinuated that I should be more responsible. The QFT has introduced me to pretty much every director and most of the actors I now hold in my holy canon of untouchable gods and offered me all this for £4 a pop after membership. Outside my own living room and the Ulster Hall the QFT is the place I feel most at home in the whole of Belfast and it’s fair to say I’m both devastated and a little bit baffled by why anyone would suggest taking much-needed funding from an organisation which is so very obviously do something right.

I know these current budget cuts are affecting healthcare and education, the environment and other areas of Northern Irish life which are all absolutely vital to the infrastructure of our country and already stretched to breaking point. However, the arts is my community, my sector, my colleagues and friends and I feel compelled to say something in defence of it. There are all manner of arguments which can be made in defence of strengthening the arts sector, (it has a direct impact on the tourism industry, it generates business and stimulates the economy, it is a vital part of education and a growing component of the drive to deliver holistic healthcare and well-being to our older people, it combats isolation, helps Northern Ireland to forge a new positive identity and gives people dignity and an opportunity to voice their own stories in their own peculiar way). All of these arguments have been made more eloquently and succinctly by other people over the last few weeks. I have nothing new to add except the fact that last night I spent three hours flicking through photos of the various arts projects and opportunities I’ve been party to over the last five years since my return to Belfast and I am undoubtedly a much richer person for having tea danced with hundreds of older people, been locked in the Lyric overnight and forced to write a play, hosted the most amazing group of young dancers with disabilities and been a fly on the wall to hear Sinead Morrissey help people who’ve lost their partners to stroke find their voices and shape them into poems. This doesn’t even begin to scrape the blessed surface of every gig, every screening, every art launch, every reading, every one of those hundred or so annual festivals and every good, bad and terribly ugly play I’ve sat through in the last few years. Belfast simply wouldn’t feel like home if there wasn’t any art here.

I know our arts community is feeling incredibly demoralised right now. I’ve done my fair share of crying in the Ulster Hall toilets of late and wondering if I should jump ship to a sector with sociable working hours, such as dentistry or librarianing. There’s only so much wrestling you can do before exhaustion begins to kick in. It’s entirely understandable that we’re all feeling this way. There are people in this city who serve above and beyond the limits of expectation, hauling amps from one gig to the next, staying into the wee small hours to hang art in our galleries, driving to Dublin and back and then on to Derry and Enniskillen all in the space of a week to perform for five people on stackable chairs, spending hours and hours cutting shapes out of cardboard to prep for kids craft, wiring sound gear, stacking chairs, dancing on knackered feet, writing in bed with a hot water bottle because they can’t afford to turn the heating on, ripping tickets, pouring drinks, dealing wit difficult audience members, wondering if anyone notices just how hard they’re working and all the easier things they’re sacrificing to be here.

It won’t make much difference with Stormont and it certainly won’t make the agenda for Nolan tomorrow morning, but I think it’s a good thing to stop for a moment and say that you are noticed and you are appreciated and tempting as it is to give up and move to London or become something that actually makes money, you should know that you have made, and in the future will continue to make, a massive difference to many many people’s quality of life. In this very difficult season as we all petition hard and wrestle with squeezing the last thirteen pence out of already exhausted budgets and try to feel festive while the arse has been ripped right out of Christmas, let’s at least remember to be kind to each other. If you’ve appreciated or benefitted from arts provision in Belfast in the last few years now would be a perfect time to let your praise be heard. For weary artists and arts practitioners a thank you email, an appreciative tweet, a wee glass of wine might well be the difference between despair and making it through to the New Year right now.

I’m not leaving Belfast. I can’t. I’ve just bought a house here I can’t afford to sell. More importantly however, I don’t want to leave Belfast. I’ve been all over Britain and America in the last few years and I can honestly say I’ve yet to come across an arts sector which works as hard and as humbly as the artists and practitioners in Belfast. I’ve also never had artistic community like I’ve encountered in Belfast. I am a better writer, a better programmer and an all round better person because I’m working alongside some of you, and I truly believe that you are the most talented and generous artists I’m ever going to work with. I know that nice words aren’t going to change politicians attitudes, so sign the petitions, write letters to Stormont, get down to our venues and buy tickets and memberships for Christmas presents, Tweet, tell your apathetic friends to get involved, do whatever it takes to keep this at the top of the politicians’ agenda. The next few years may not be the easiest but I honestly believe enough wisdom and wit and truth and imagination and sheer bloody-genius in this wee community to see us all through the wilderness.

December 4, 2014

An Afternoon with Eimear McBride

Yesterday was not my best day ever. I had a really important interview first thing in the morning and woke up with a sky high temperature, blocked nose, cactus throat and cotton wool where I usually have a brain. During the interview I sat shivering in my outdoor coat unable to make sense of the questions, (and they weren’t that difficult questions), struggled to recall the name of any institution in Belfast, aside from the Tourist Board, and left earlier than I’ve ever left an interview, feeling like I’d been run over by a truck. (I have been in bed ever since and am only now, thirty six hours later, beginning to feel vaguely human again).

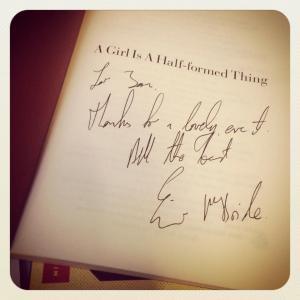

Just forty five minutes after my own mortifying interview experience. I was due to interview Eimear McBride, (author of the wonderful, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, winner of every literary prize in the Western world and personal hero of mine), for our Literary Lunchtime series. I’d been looking forward to this interview for about six months. In my head it was to be the first step in my career as a serious interviewer and would lead swiftly and decisively to a moment in the not-too-distant future, where I’d oust Jeremy Paxman from his chair, take over Newsnight and usher in a new era of friendly chats to replace his firing squad-style interrogations. I’m currently reading the poet, Simon Armitage’s book, Gig. It’s a piecemeal memoir of his experience as a live poet, “gigging” his way round the literary scene. I particularly enjoyed what he had to say about literary programming.

Armitage is totally spot on. Most readings I’ve programmed are more church social than live rock experience. Readings by their very nature are low key, minimalist affairs; there’s only so much showmanship you can bring to an event which is in essence a person reading some words they have written. Also literary audiences tend to be rather nice. They don’t, (usually), heckle. They rarely throw empty pint glasses onstage. They are occasionally accompanied by sandwiches and almost always include at least one well-wisher who lingers after the “gig” to tell the reader just how nice they are. Even when I’ve read with Hannah playing music on her enormous keyboard and Lizzy playing music on her cello and we’ve joked about “gigging” we’ve all known it’s not really a gig when the entire audience is seated on comfortable chairs, sit reverently through the performance and are home in time for the nine o’clock news.Yet there are a few readings I’ve programmed over the years which have felt just a little more rock n’ roll than others: Jo Nesbo, (possibly because he is also a rock star and was, at the time wearing a fetching leather jacket), the Heaney commemorative reading with Don Patterson and Carol-Ann Duffy, (which was in the Grand Hall and pulled in a bigger crowd than U2 the first time they played the Ulster Hall), and our Bob Dylan Literary Lunchtime, (simply because it was all about Bob and at least one person was wearing sunglasses indoors).

I was sincerely hoping Eimear McBride would be another one of those readings which totter on the edge of becoming gigs. She’s a bit of a rock star in my eyes. She’s such a brave and ballsy writer, not only because of the unique style and the content explored in Girl, but also because she’s shown remarkable tenacity in persevering with a novel which took almost a decade to get published. In every interview I’ve read Eimear McBride has come across as opinionated and yet measured in that wonderful fashion peculiar to those who actually have something worth saying. There were a lot of tickets sold to this event; a lot of people excited about hearing Eimear and, yet at approximately twelve o’clock on Wednesday afternoon I was pretty sure it was going to be a wash out. I could barely read the questions I’d prepared let alone instigate any off the cuff, literary banter. My “gig” was beginning to look like a disappointing end to a very disappointing day.

Thankfully however, a combination of strong coffee and Lemsip Max, seemed to finally kick in about twelve thirty and Eimear McBride, (who turned out to be one of the warmest and easiest to work with writers I’ve come across in the last four years), was such a consummate professional that the afternoon redeemed itself and was, by two o’clock, one of my all time favourite Literary Lunchtimes. Despite one ill-timed microphone cough, (deafening the ladies in the front row), my lurgy remained in check for the duration of the interview. Eimear read the opening section of Girl for us and, hearing the prose as she must have heard it when writing the novel, was a wonderfully fresh angle on the book. She talked about the current state of the publishing world, the importance of perseverance when beginning on your journey as a writer and something of her own writing process. Questions from the audience were well thought through and very insightful and there was a massive line of Literary Lunchtimers waiting to get their books signed after the reading. It wasn’t exactly a gig but I definitely came away a little more buzzed and exuberant than I usually am after a reading. Am heading back to my programming board, freshly enthused about booking some great readers for the new year.

November 28, 2014

The World’s First Computer

In honour of the rather mediocre adaptation of Alan Turing’s life currently gracing the big screen, here’s a wee piece of flash fiction I wrote after visiting Bletchley Park a few years ago.

The world’s first electronic digital computer is located in Bletchley Park, ten minutes from Milton Keynes. It is personally responsible for the birth of all future computers and computerish things: Ipods, Ipads, Sonic the Hedgehog, Skype, Bill Gates and probably holograms. It was designed to decode important German intelligence messages during the Second World War.

The world’s first computer appears to be built from Meccano and Christmas tree lightbulbs. It constantly eats and emits reams and reams of old-fashioned printer paper, the kind with hole punched holes running along each side. It is housed in the sort of porta-cabin normally used to contain rural Sunday School groups. A stuffed squirrel has been lodged comically between its circuit boards and switches.

The world’s first computer looks mortified.

November 24, 2014

Malcolm Orange Disappears: Book Group Questions

Quite a few of you, (and you may well be lying to make me feel good), have expressed your intention to host a Malcolm Orange Disappears book group. It’s cold outside. It gets dark rather early. I can think of nothing better than opening a bottle of wine and talking about the People’s Committee for Remembering Songs with a few other bookish people. I know you’ll all have your own opinions on the book but, just to get you started, here’s a few questions to get you chatting about Malcolm. Let me know how you get on and I’d love to see some pictures.

1. What did you enjoy about Malcolm Orange Disappears?

2. What aspects of the book did you dislike or struggle with?

3. To what extent is Malcolm Orange disappearing and what does his disappearance represent?

4. What are the overarching themes of the novel?

5. Did you have a particular favourite character and if so what specifically drew you to this character?

6. To what extent is Malcolm Orange Disappears an American novel? Would the book have worked if it was set somewhere else?

7. Martha Orange is a particularly complicated character. Did you find her likeable? How responsible is she for her own circumstances?

8. How is the process of aging portrayed in Malcolm Orange Disappears? Do you think older people are pitied or celebrated within the novel?

9. Is Cunningham Holt a tragic figure or a hero within the novel?

10. The flying children passages are some of the most powerful and oft-commented upon sections of the book. What do you think the flying children represent?

11. Malcolm Orange Disappears is not a simple, linear story but instead seems to encompass a number of short stories. Did the plot succeed in holding together all these stories? Which stories particularly resonated with you?

12. A lot happens in the final chapter of the novel. Did you feel the ending offered a satisfactory sense of resolution? How could it have been improved upon?

November 16, 2014

Dublin Book Festival

Writing is probably the most serious and glamorous of all art forms. Anyone who happens to come across one of the earnestly intense author photos which grace the covers of paperback novels and poetry collections will instantly understand this. If the black and white filter doesn’t give you a hint, the writer’s furious gaze and polo neck sweater will fill you in on the details. In my author photo I look like the kind of person who might go on Newsnight to talk about feminism or plummeting standards in Secondary education. I look like I take myself very seriously and expect everyone else to approach my work with equal gravitas. I do not look like the kind of writer who would accidentally turn up for a reading wearing my trousers the wrong way round. Pictures can be deceiving. Most writers I know are rarely serious and only glamorous under the right kind of lighting. If nothing else, our wee adventure to Dublin Book Festival on Friday reminded us that this business is one tenth glamour and nine tenths sheer, bloody graft.

Dublin Book Festival invited me along to read from Malcolm Orange Disappears about three months ago. A week or so later they emailed back to see if Hannah McPhillimmy, my terribly talented song-singing sidekick, would like to come too. This was a no-brainer. Road tripping with Hannah is a sheer delight. Over the last six months we’ve played together quite a few times across Ireland and though we’re not exactly the Rolling Stones and usually go heavier on the wine gums than the actual wine, she’s great old company in the car and fairly good at measuring out the Euros for the motorway toll. I’d go pretty much anywhere with Hannah. I’m not so keen on her keyboard.

When I decided to collaborate with a musician I didn’t think through the practicalities of the arrangement. If I had I would have gone for a flautist or, at a pinch, a regular guitar-weilding singer-songwriter. Hannah’s keyboard deserves its own postcode. It is roughly the size of a coffin and weighs more or less the same as fully-loaded washing machine. It is wheeled. Though the wheels are more inclined to inflict pain upon an unsuspecting ankle or doorframe than afford any ease of movement. It just about fits into the back of my car if the seats are lowered and it is sideways inclined to slip between the two front seats and nose the edge of the dashboard. Sudden breaking causes the keyboard to hurtle, (infernal wheels choosing their own moment to aide movement), dangerously forward threatening to smash through the windscreen and instigate the sort of horrific accident heavily featured on DOE road safety commercials.

Despite repeated and detailed calls to venues, warning our hosts ahead of time that we are bringing the biggest keyboard this side of Glam Rock and it will require technical assistance and, if possible, some sort of hoisting mechanism to navigate it up even the smallest flight of steps, time and again we turn up to find our hosts have envisioned a battery operated Casio rather than the behemoth we’ve lugged up two dozen stairs in high heels. As a result most every “gig” (and I call these music and spoken word affairs, gigs for I am unlikely at this stage to ever achieve my ambition of gigging in a proper band with CDs for sale like Del Amitri, for example), we’ve played has seen us red-faced and sweaty from the sheer effort of manoeuvring the keyboard from Point A to Point B. We are not, by nature, sweaty girls, but circumstances have not been kind to us lately.

Dublin Book Festival was no exception. Having left Belfast preternaturally early, (7:45am), for a midday reading, I had envisaged stopping for a leisurely coffee and service station pastry somewhere on the outskirts of Drogheda. The morning had other plans. First we were delayed for an hour waiting to drive through an enormous puddle outside Banbridge. Then we got lost trying to follow our map quest directions and stuck in the one way loop which keeps the uninformed motorist endlessly rotating round the edge of Temple Bar as if caught in the seventh circle of Hell. Then we found the right building but the wrong door and finally the right door but the wrong room. Suffice to say we were a little flustered by the time we arrived on stage. I then discovered that in my haste to leave Belfast I’d put my trousers on the wrong way and became lost looking for a toilet in which to rectify my mistake. The reading itself was grand but I have to say we weren’t exactly the most glamorous people in the room. Later there were other minor dramas, (lost cardigans, angry waitresses, a Toyota full of elderly priest blocking our way out of the multi-storey), and by the time we got to the end of a full day’s readings we were were too tired for after-partying and spent the evening watching the Late Late Show and eating chocolate digestives in our hotel beds.

Dublin Book Festival was marvellous. We were particularly enamoured with the free chocolate and the kind welcome from Julianne and her team of lovely interns. Smock Alley Theatre is a stunning venue and perfect for readings. We got to meet and hear some wonderful authors and catch up with old friends and Hannah did a particularly stunning job providing music for RTE Arena which came live from the Book Festival. I was very proud of her and almost told the stranger sitting next to me that I was her roadie, (I felt justified in doing this as I had fresh keyboard shaped bruises to support my claim). It was fabulous to be part of the festival and hopefully not our last opportunity to be included. Next year we are going to work on being more glamorous. Most likely this will involve locating a slave to haul the keyboard around, (internship anyone?)

November 11, 2014

The Bends

It’s three weeks since I returned from America; one week since I returned to work. A lot has happened. Not very much has happened. I’m slowly beginning to realise that I’ve managed to make the most almighty hash of re-entering the real world. I tried too come back too quickly. I expected too much. I feel like I’ve got the bends and all I want to do is hibernate.

People keep asking me if it’s nice being back at work. It is not nice. It feels like the best and longest school summer holiday I ever experienced ended overnight, leaving me one minute basking on a lazy, sun-drenched beach and the very next, in the bleak mid winter, working every hour God sends and, every time I venture outside, getting drenched in that enormous puddle outside Maysfield Leisure Centre which Translink drivers seem so drawn to, (the first part here is slight exaggeration, the last part, based entirely upon a true story). Of course, it’s nice to see everyone at work. I share the world’s greatest building with a collection of the world’s greatest people and three months without seeing any of them, or indeed partaking of the curly fries in the staff canteen, has been something of a stretch.

However, in the last ten days I haven’t managed to write a single sentence of any worth. (Duty management reports aside). I have fantastic ideas which keep me up at night, insomniac and scribbling notes in the inside cover of whatever paperback I’m currently reading. But each time I sit down at my keyboard the sleep catches up with me and I wake twenty five minutes later, defeated and ill-inclined to make yet another stab at finishing chapter fourteen. I feel like a fraudulent writer every time I tell people the new novel is nearly finished. Yes, it is nearly finished but let’s just say it’s no nearer being finished than it was six weeks ago. The end is in sight but it’s not making much effort to meet me halfway and I’m developing the horrible suspicion that, (despite everything my mortgage has ever told me), full time work and serious novel writing might be too strong a combination for me. I’m a little bit afraid of where this is going.

I have done many, many things to reassure myself that I am not wasting precious writing time. I’ve sorted out my accounts, given a lecture about my forthcoming, (rather slowly) novel, scoured my wardrobe for missing buttons and sewed them all back on, written a Belfast-based musical in my head, watched far too much ITV3 and tonight, as the ultimate in not-writing-distractions, ripped all the wallpaper off my bedroom. I’m hoping the block lifts soon. I don’t feel like myself when I can’t write. Constipated is probably the best word for this feeling. If the sentences don’t come back soon I might actually consider writing that Belfast-based musical in the real world and this probably wouldn’t be the best news for anyone. Patience please. Re-entry seems to be taking longer than I’d scheduled.

November 1, 2014

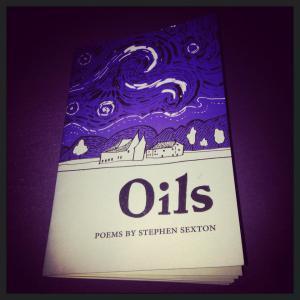

Talented Friends – Mr Stephen Sexton

I’ve said it once and I’ll say it again, over the years I’ve been extremely blessed to fall into friendships with many wonderfully talented people. I don’t see this run of good fortune coming to an end any time soon. On Thursday evening it was an absolute delight to celebrate yet another writer who has, over the last few years, become a really great friend and also an exceptional poet.

I was first introduced to Stephen Sexton around three years ago and have not only grown to value his encouragement and insight into my own writing but also come to really enjoy his poems. I’m not sure exactly why I like them so much. They’re often stacked full of incongruous images and intriguing phrases and sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what they’re about. However, like much of Dylan’s late 60s work the rapid fire imagery comes magically together to invoke a powerful feeling. Stephen’s poems have helped to convince me that poetry is something I can actually enjoy, even if I can’t explain why. I don’t feel quite so much the poetry Philistine when listening to him read. This is quite a big confession from a girl who read Autumn Journal beginning to end and never noticed that it rhymes.

When you find yourself, as I often do these days, surrounded by enormous numbers of poets it can be very tempting to turn to your fellow prose writing friend, (I say friend rather than friends, because more often than not Mickey and I seem to be the only two prose writers in Belfast, propping up the back row of poetry readings), and instigate speculation on which of these fine young poets will go the distance, which will still be composing sonnets, (and other poetic forms of which I am entirely ignorant), in ten years time, which will feature in the “best of Irish poetry” compilations forming the backbone of GCSE English curriculums in the next century. When these debates invariably come up, I always say I’d put a tenner on Stephen Sexton going the distance and if I was I betting woman and bookies took bets on future T.S. Eliot prize winners, I’d actually put my money where my mouth is.

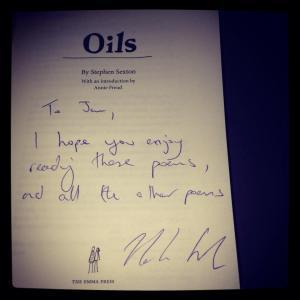

The Emma Press, a wonderful English publishing house specialising in poetry pamphlets, launched a small collection of Stephen’s poems, as part of the Belfast Festival at The Crescent Arts Centre this week and, after many months of anticipation, it was great to finally get my own copy of Oils, albeit with a rather cheeky dedication on the inside cover. If you haven’t heard Stephen’s work before you should proceed with all due haste to the Emma Press’ website (www.theemmapress.com) and buy yourself a copy for £6.50. It’s a thing of great beauty with a gorgeous illustration based on Stephen’s “Starry Night” poem on the cover and a host of wonderful words inside. I don’t think you’ll be disappointed.

October 29, 2014

Re-Entry

This last week hasn’t been the easiest. I arrived back in Belfast ten days ago, after almost seven weeks adventuring around America and, while it was lovely catch up with friends and see family after so long away, and it was genuinely brilliant to get along to a couple of friends’ readings over the weekend, I have to admit re-entry has proved to be a bit of a crunch. The jet lag hit me like a steamroller, then the writer’s block kicked in and, after almost two months traveling by myself, I found being back in the social world more than a little overwhelming. If I’m entirely honest, I spent most of the last ten days wishing I could hide out on the living room sofa with a hot water bottle and a direct hook up to ITV3 and at times, that’s exactly what I did.

Next Monday all that ends. I return to work and I’m really not looking forward to it. Don’t get me wrong, I absolutely love the Ulster Hall and have been convinced for at least four years now that I have the best job in Belfast. However, for the last three months I’ve just been a writer and it’s been liberating. Instead of writing in the margins of my life, juggling little slots of writing around work and other responsibilities, I’ve been able to make working on the novel my main focus. I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to fill up my time and have actually found myself busier than I could ever have expected. I’ve relished every moment of the experience, even those which have felt like something of a stretch.

During the six weeks before and after my American travels I developed my own routines to give the days some shape and ensure I didn’t stay in bed all day watching Murder She Wrote. I’ve been walking into the city centre, splitting my time between a couple of coffee shops and working on the novel, slowly and steadily for around 3 hours each days. I currently have fourteen of sixteen chapters written and am confident that I’ll have some sort of first draft finished in time for the New Year. Afternoons have been reserved for drinking more coffee and indulging in good conversations with a variety of people I don’t always get to spend time with. And, in the evening, I’ve been social without having to battle the guilt normally associated with wasting time I could have been using for writing. As well as progressing the novel I’ve also managed to write three new short stories during my time off and around four dozen small postcard-sized pieces of flash fiction. I read some great books and watched a lot of British made crime drama. It’s been great and I’m reluctant to see this chapter come to a close at the end of the weekend.

Looking back over the last three months the best thing about being, just a writer, is that the stories have become my priority. I’ve not been so tired that I can’t serve them properly. I’ve not been so over-scheduled that i’ve had to leave them be for so long that they grow stale and weary. I’ve not been constrained by practicality so when ideas have come to me in the middle of the night, I’ve ignored the clock and reached for my notepad. My head has been clearer than it has in years. I’ve been more productive, writing wise and read in a different, more focused fashion. I’ve had more “brilliant” (and not so brilliant but extremely pressing), ideas in the last three months than in the last three years combined. And perhaps, most importantly of all, I’ve felt my confidence grow exponentially. Each time I introduce myself as “just a writer” I feel a little more entitled to own those words.