Simone Zelitch's Blog, page 2

November 5, 2017

Who owns a song?

Most of the people who read this know I write novels, and you also probably know that I teach at Community College of Philadelphia. Our students are products of a public school system in free-fall. Frankly, without our union, the work would be impossible. Our salaries are low, but we have reasonable course-loads, good health care, and a remarkable degree of freedom to choose our own materials. People have built professional lives here, including me. I’ve been at the place since 1993. [image error]

Then, a new college administration came along, and things got rough, and then got toxic. President Guy Generals is demanding slashes in healthcare, and a 25% work-load increase that would make it impossible for us to work with students. He and the board of trustees show no sign of budging from this position, and have stopped negotiating. Thus, we’ve been working without a new contract for over a year.

So what do we do? We try our best to organize, to let students know where we stand and get those students to stand with us. We raise some hell. On the first Thursday of November, group of faculty, staff and students waited in the cramped space outside the marble conference room as the college’s board of trustees held its executive session. Student and faculty speakers had been scheduled for three o’clock. Now, it was three thirty, and there was some danger that the crowd in the hallway would disperse.

[image error]Someone started a chant: “What do we want?” “Contracts” we called back. “When do we want them?” “Now!” This went on for around thirty seconds. Then it stopped. Maybe we felt self-conscious. Maybe we were just out of practice. We tried another: “Two, four, six, eight! Why don’t you negotiate!” That didn’t last long either.

Here’s another thing some of you may know about me. I sing a lot, and shamelessly. I always have. It may come out of years of creating elaborate song parodies with my family and friends. I checked in with a union officer, and he granted me permission to begin a round of : We Shall Not be Moved. It was what Pete Seeger called a “zipper song” where you could insert lines to fit a situation: “We are fighting for our students! We shall not be moved!” That got some general participation, and if I’d been on my game, I might have kept it going for a while, and added verses pretty much indefinitely; I’m good at that.

Then someone asked, “What about We Shall Overcome?”

I’ll admit that something about the suggestion seemed a little off to me. That song felt too grand and portentous. It wasn’t meant for biding time before a meeting. Still I was glad for any input, and sure, I started to sing it along with a few others, but it dwindled after a verse and a half.

After the meeting, the social media response began.

It was some woke white folks who started it: A bunch of mainly white faculty singing a hymn that was central to the Civil Rights Movement is a form of microaggression. We caused deep discomfort in the African Americans who were present. Then came the response from some other folks– yes, yet more white folks– who were either there or weren’t there, and posted videos of Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen singing We Shall Overcome, and so on. Two faculty of color joined the discussion which grew increasingly personal and accusatory. It was like a group of people poking at an open wound until it starts to fester and turn gangrenous.

And I remembered how I felt when we began to sing We Shall Overcome, that it didn’t suit the circumstances, that it belonged to a kind of continuum of struggle and I wasn’t sure our immediate struggle was something we’d aspire to “someday.” Plus, frankly, the rhythm was all wrong. Initially, I found myself wanting to reply to those messages along the lines of “Hey, it’s not my fault.” Then, I found myself wanting to stay out of the fray. Finally, to my own surprise, I got slowly, truly and absolutely angry.

I wasn’t angry at microaggression-sensitive white folks or white folks who were half-asleep like I can be at the end of a three hour block of intense teaching. I certainly was and am awake enough to know that good intentions can’t excuse thoughtless actions. Heck, I wrote a whole novel about that, focusing on how the good intentions of the privileged pave the road to hell. However, here’s the truth: I was angry at the idea that We Shall Overcome belongs to one period in its history, and one group of people. I was angry at the inherent connection of purity to progress, a classic right-wing equation. I was angry that a political idea or a strategy, or what’s even more absurd, a song, shouldn’t cross borders. Or maybe I was just angry at the thought of someone telling me what I could sing.

At the same time, it’s disingenuous to pretend that We Shall Overcome is just any old song. It’s associated with the 1963 March on Washington— and everything that led to and beyond that march. Yet according to a recent article in The Atlantic, the song has complex origins, beginning a distinctly European 17th century hymn, changing verbs and pronouns over the years, and surfacing on the picket line where it was sung by workers in a tobacco-factory, primarily African American women.

At the same time, it’s disingenuous to pretend that We Shall Overcome is just any old song. It’s associated with the 1963 March on Washington— and everything that led to and beyond that march. Yet according to a recent article in The Atlantic, the song has complex origins, beginning a distinctly European 17th century hymn, changing verbs and pronouns over the years, and surfacing on the picket line where it was sung by workers in a tobacco-factory, primarily African American women.

To make things all the more ambiguous, it’s likely that this song– along with other protest songs that began their lives as hymns (like We Shall Not Be Moved)– were discovered by a white labor organizer who heard them on the picket line. She was Zilphia Horton, born in a coal-mining town in the Ozarks, alienated from her family because of her politics, and the cultural director of the Highlander Folk School, an incubator for nonviolent resistance. It was Horton who secularized sacred songs like We Shall Not be Moved or popularized the new words to The Battle Hymn of the Republic which transformed that march into Solidarity Forever. As the Highlander Folks School began to focus on anti-segregation work in the ’50s, its leadership included African American women like Bernice Robinson and Septima Clark. Rosa Parks attended Highlander four months before she refused to give up her seat on the bus in Montgomery.

To make things all the more ambiguous, it’s likely that this song– along with other protest songs that began their lives as hymns (like We Shall Not Be Moved)– were discovered by a white labor organizer who heard them on the picket line. She was Zilphia Horton, born in a coal-mining town in the Ozarks, alienated from her family because of her politics, and the cultural director of the Highlander Folk School, an incubator for nonviolent resistance. It was Horton who secularized sacred songs like We Shall Not be Moved or popularized the new words to The Battle Hymn of the Republic which transformed that march into Solidarity Forever. As the Highlander Folks School began to focus on anti-segregation work in the ’50s, its leadership included African American women like Bernice Robinson and Septima Clark. Rosa Parks attended Highlander four months before she refused to give up her seat on the bus in Montgomery.

Of course, most of these songs of protest had their origins in the pews of a church, yet they were snatched– or appropriated– from those pews by people who weren’t Christians, like the students of existentialism who made up the vanguard of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Bob Moses who quotes Camus, the student of philosophy Stokely Carmichael[image error]. Of course, there were Christians among those students and the local people who shaped their organizing strategies, but ultimately, when the community gathered at the end of their all-night meetings and sang: This May be the Last Time, they weren’t referring to Christ’s second coming; they actually knew that their battle against white supremacy might get them killed. Sometimes, it did.

Who owns a song? More to the point, who has the right to be included in the legacy of what people used to call “The Movement”? Out of SNCC’s radical democracy came the  Berkeley Free Speech movement— begun by white college students who’d returned from their summer in Mississippi in 1964, Radical Feminism– which some may argue grew out of an anonymous SNCC position paper on “The Position of Women in the Movement” probably authored by Mary King and Casey Hayden– and much of the anti-authoritarian Left I gravitated towards when I came of age in the post-Watergate era.

Berkeley Free Speech movement— begun by white college students who’d returned from their summer in Mississippi in 1964, Radical Feminism– which some may argue grew out of an anonymous SNCC position paper on “The Position of Women in the Movement” probably authored by Mary King and Casey Hayden– and much of the anti-authoritarian Left I gravitated towards when I came of age in the post-Watergate era.

Who owns the Movement’s icons? At the Women’s March on Washington last year, I was heartened to a revival of the black power fist and the women’s symbol. Is that a form of cultural appropriation, or an acknowledgement that we can and should learn from each other? When we borrow organizing models from SNCC– or examine those models in the context of SNCC’s internal conflicts — are we engaging in microaggression? Is it worse to not name SNCC at all?

So who owns We Shall Overcome? Apparently, a court decided that the first verse is now in the public domain. But more to the point, who owns the legacy of the movement that made that song an anthem? Martin Luther King’s commitment to nonviolent resistance was influenced by Gandhi. Gandhi was inspired by Tolstoy. A cursory exploration led me to Tolstoy’s own list of books that influenced his thinking, and in later life, they include explorations of the life Confucius, the Buddha, and Lao-Tzu.

Who owns the legacy of resistance? I was lucky enough to grow up with some veterans of these experiments in radical democracy. What does it mean to organize without a leader? How can we gather strength and stand up to illegitimate authority?

At Community College of Philadelphia, we work to shape our students into active citizens who face these questions every day. My novels center on those questions too, and the first one I published was about– of all things– a 14th century Peasant Revolt. It began with an epigraph by William Morris:

“[People] fight and lost the battle, and the thing they fought for comes about in spite of [our] defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, [others] have to fight for it under another name”

I altered the original male pronouns (my my academic way) because we all know better now. Along the same lines, we should know better than to arrogantly dismiss or shame those who feel a sense of cultural ownership of a song that is associated with a historical moment. Can we figure out a way to honor that history, while also knowing that the history resonates in ways that cross borders?

In 1939, when Zilphia Horton gathered her appropriated songs into a booklet to distribute to unions throughout the country, labor leader John Lewis wrote in that booklet’s introduction, “A singing army is a winning army.”

There will always be new singers, and we can’t know how those songs will change. Frankly, how can I keep from singing? (Click on that final link. It’s beautiful).

August 18, 2017

Judenstaat 2017

I haven’t written a blog post for over a year, and a wild year it’s been. From Brexit to the anti-elitist movement in the U.S. to the science fiction morning when we woke up and discovered Trump was president, fact has overtaken fiction. Frankly, you could say I’ve been speechless.

[image error]It’s also been a little over a year since my novel Judenstaat was published. Judenstaat is an alternative history about a Jewish state established by Soviet liberators in Germany in 1948. Acquired for Tor by David Hartwell who died six months before the book was published, Judenstaat was tough to market, in part because it was pitched as a thriller but was really a novel about history—how it shifts to match a fashionable ideology, about facts that exist and facts that are erased to create simple and uplifting stories.

I wrote Judenstaat back in the Age of Uplift. The collapse of communism was pitched as an uplifting story. The election of Obama was pitched an uplifting story. People even tried to find uplift in Israel and Palestine in ways that were only possible if they practiced selective amnesia.

In fact, my wonky, weird alternative history was a reflection of those years—when monuments were being toppled and walls collapsing in ways that appeared irreversible. That’s why I set the book in 1988, when a Jewish state established in what we think of as East Germany was facing a period of transition. Judenstaat had a wall to keep out German fascists. Inevitably, that wall would fall. In turn, the Soviet liberators would be re-framed as Soviet occupiers, fascists would become anti-Soviet partisans, and so on.

[image error]Street signs in Budapest in transition, 1991

As one Jewish-Hungarian reviewer, Bogi Takács, pointed out, Judenstaat owes a debt to my time as a Peace Corps volunteer in Hungary from 1991-1993, during just such an ideological transition when we were told the country was “opening up.” Communist street-names were replaced and statues removed from pedestals. By the time I left the country, child-care was no longer subsidized, but you had no problem buying a Pepsi in a village cukrászda. At some point after I returned to America, I remember watching an Visa commercial set in Budapest, oppressively affirmative. Hungarians are free to dance through glittering fountains, set off fireworks, and buy things on credit.

Judenstaat assumed this context: globalization is a giant bulldozer, moving relentless forward, erasing distinctions, borders, and identities.

Boy, was I wrong.

[image error]The bulldozer has crashed, or run out of petrol, or been set on fire. The Age of Uplift is now the Age of Authenticity when only personal experience matters, and Trump can actually say, of historians who say a Civil War battle never took place on his golf course, “How do they know? Where they there?” Walls are being built or re-built, some physical, some psychological. We’ve never been so obsessed with identity. Again, how we should feel about this isn’t obvious.

After all, we should have seen it coming. When you tear down a wall, you release a ghost. When you decide a public square should not be named after Robert E. Lee and choose something affirmative and non-offensive, say, Emancipation Park, you can’t assume that we have been emancipated from the past. The so-called “openness” of Hungary has given way to a reactionary government and a resurgence of the fascist Arrow Cross. Topple a Soviet memorial, and it may well be replaced with a statue of the Tsar, followed by a full-on, old-fashioned pogrom.

Last April, a review of Judenstaat appeared in the Israeli newspaper, Haaretz. It was thoughtful and fascinating, if ambivalent, and its author, the scholar Yaad Biran, took the book seriously in ways I found impressive and instructive. At the same time, he thought I’d bought into the same shifts in ideology I’d tried to savage in that novel, the uplifting “End of History”. Actually, I don’t believe history has an end.

Yet Biran also raised a challenge. I’d set the novel in 1988. What would Judenstaat look like in 2017? Months later, here’s my answer.

In 2017, Judenstaat would have long united with Germany. In fact, the Protective Rampart the country had constructed to keep out fascists would be no more than a memory. As is the case in Lithuania, its Genocide Museum would document Soviet atrocities against Germans and Jews alike. Fascists? What are fascists?

[image error]Judenstaat’s version of the East German Trabant is called the Yekke, which is kind of a Zionist in-joke.

Sure, there are some very very old German Jews who do remember fascists, the Jews who were adults when the country was founded in 1948, and then there would be aging Boomers like my novel’s heroine who would miss the security they’d felt in their own country with its specific Jewish institutions. They’d feel profound Judenstalgie which would extend, in an ironic way, to non-Jewish German hipsters who’d make a point of listening to Judenstaat’s music from the ‘60s, or hanging old Dresden road signs in their coffee shops.

But the millennial generation of Jews don’t have a language to talk about Judenstaat’s past. They know what they see with their own eyes: an economically depressed eastern region, a sense that they’ve been pushed into the margins. Judenstaat’s factories have relocated to Indonesia or Tennessee. Russian oligarchs make global trade-deals that line their own pockets, and build mansions in Saxon Switzerland. Amazon opens a massive data center in Zeitz, displacing archeologists from a site where they’d discovered fragments of a synagogue.

So in 2017, there would be no country called Judenstaat, but there would be Jews in Germany who feel displaced and angry, and they would long for a distinct identity. Would they become religious? That’s possible, though many of Judenstaat’s ultra-orthodox emigrated after reunification and regrouped in Brooklyn and Northern New Jersey. Would they assert a cultural Jewish identity that has no borders? Would they start speaking Yiddish, like some of my neo-Bundist friends in West Philadelphia? Would they fight corporate globalization, and at the same time acknowledge and call out antisemitism on the left? That’s one scenario.

Here’s the most logical path: these disappointed and resentful young people who feel an inchoate sense of loss create Jew-only “safe spaces” and discuss their own oppression. T They’d talk about authenticity, purity and independence. Why did their parents ever allow Judenstaat to be a pawn of America or the Soviets during the Cold War, and to accept the loss of their country once it was no longer useful to the either side?

These young people would believe that Jews need a place that is not given to them for strategic purposes, and not a refuge. This place must be the embodiment of Jewishness, where they could be the agents of their own salvation. They’d reject the symbol of Judenstaat– the yellow star—and search for a new way to express a Judaism that goes beyond Jew-as-Victim. They’d go deep into the past, search for a defining, unifying aspiration that could become a kind of secular religion.

In short, they’d become Zionists.

[image error]Another alternative Jewish state, with its own set of contradictions

And yes, they’d post and tweet on social media, struggle with competing factions and trolling, and organize on-the-ground protests at sites where displaced monuments once stood. There might be some pepper-spray dispensed by one side or another.

Would these Zionists be considered alt-right or antifa? Does it depend on how these terms are defined? Is identity politics anti-fascist if the group in question doesn’t have real power, but fascist if it does? Who defines power?

I’ve said several times already, how we should feel about this isn’t obvious.

August 10, 2016

On Alternative History and Historical Amnesia: MysteryPeople Q&A with Simone Zelitch

Molly Odintz of Mystery People recently sent me a list of questions– pretty darn complicated ones at that! I did my best to answer them. Here’s the resulting interview.

Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of reading Simone Zelitch’s Judenstaat, a brilliant and complex merging of the strange histories of Israel, East Germany, and Birodbidjan (Stalin’s bizarre attempt at a Soviet Jewish state). Judenstaat takes place in the late 80s, in an alternative history where post-WWII, the Soviet Union has created a Jewish state in the German region of Saxony. Zelitch was kind enough to take some questions about the book and its inspirations.

Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of reading Simone Zelitch’s Judenstaat, a brilliant and complex merging of the strange histories of Israel, East Germany, and Birodbidjan (Stalin’s bizarre attempt at a Soviet Jewish state). Judenstaat takes place in the late 80s, in an alternative history where post-WWII, the Soviet Union has created a Jewish state in the German region of Saxony. Zelitch was kind enough to take some questions about the book and its inspirations.

Molly Odintz: Judenstaat brings together threads from the history of several regions and peoples – you weave together the history of East Germany, Birobidjan and Israel/Palestine for a many-layered alternative history of Saxony as a Jewish state. How much did you draw on real history for your narrative? How did you create a story that functions on so many different levels?

Simone Zelitch: Probably the one thing that weaves all these histories together is the way that nation-states tell stories—and what gets left out of those stories. In the case of Judenstaat, my own reading about Zionism and my time in the Peace Corps in post Cold War Hungary led me to think about the way that “narratives” are constructed, but as I pursued the idea of a Jewish State in Germany, I was lucky enough to find some books that complicated my own preconceived ideas and really enriched the novel. Three books that come to mind are: Amos Elon’s The Pity of It All a marvelous account of the history of Jews in Germany, Nora Levin’s two-volume The Paradox of Survival: the Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917, and Mary Fulbrook’s The People’s State: East German Society from Hitler to Honecker. They all made me consider a specific legacy (Jews in the tradition of the very German Moses Mendelson), a specific dilemma (how Jews survived or didn’t survive in Stalin’s Soviet Union and the countries under its domination), and a specific location (a German state which—much like East Germany– constructs its own origin story as a response to fascism, with its borders, and, of course, its wall). I think these different layers do challenge readers, particularly as I overlay an imaginary history. My hope is that my focus on Judit, the archivist, and her own struggle to make sense of all these layers, gives readers a chance to struggle along with her.

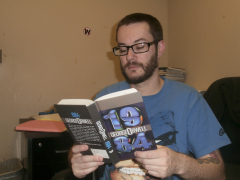

“But here’s the real key to Judenstaat: Nineteen-Eighty Four. I recently wrote that my novel is Orwell Fan Fiction. I borrowed Orwell’s structure—from the Ministry of Truth where history is rewritten, to a Leon Trotsky-like bogey-man who challenges the Great Leader, to the hidden, secret book/manifesto.”

MO: I’ve been on a bit of an alternative history kick lately – would you say Judenstaat is in conversation more with history, or with other alternative histories? Who were some of the writers you went to for inspiration?

At some point in my life, I read The Man in the High Castle, but actually didn’t re-read it until after I’d finished Judenstaat. I was somewhat startled by the way it had insinuated itself into my consciousness (the character of the Stasi Agent Joseph Bondi owes a lot to Joe) but I feel compelled to say that I only saw the TV adaptation after Judenstaat was published; maybe they stole the film-footage idea from me. Also, I’d started Judenstaat when Michael Chabon published The Yiddish Policeman’s Union. I felt like jumping off a cliff. I read it, of course, and admire it, but the only influence it had was this: I changed my ending because it was too close to his own ending, and in the process, changed the structure and philosophical direction of the novel for the better. Thanks, Chabon.

But here’s the real key to Judenstaat: Nineteen-Eighty Four. I recently wrote that my novel is Orwell Fan Fiction. I borrowed Orwell’s structure—from the Ministry of Truth where history is rewritten, to a Leon Trotsky-like bogey-man who challenges the Great Leader, to the hidden, secret book/manifesto. I stole a line verbatim at a crucial point. See if you can find it.

MO: Your vision of cultural dismantling in a Soviet-controlled Jewish state feels frighteningly real. Can you give us some background on the Soviet attitude toward ethnicity and religion?

I’m not a historian, just a novelist. I do know that in the Soviet Union’s early years, there was a tension between internationalism (as represented by Trotsky who ultimately was villainized and died in exile) and nationalism (as represented by Stalin who remained in power from 1929 until his death in 1953). Did you know that Stalin wrote some early—and admired—pieces on nationality? Yet the recognition of nationality was always on Soviet terms. Take Birobidjan, the only country in history where the national language was Yiddish, but a Yiddish stripped of any words of Hebrew origin, a kind of secularized Yiddish. Ultimately, and inevitably, many of the Jews in Birobidjan were victims of Stalin’s political purges.

In terms of my imaginary country, Judenstaat is clearly useful to the Soviets—both as a way to punish Germany and also, initially, as a way to create trade connections with the west. Yet my novel reflects the early Soviet tension between nationalism and internationalism. Under Stalin’s influence, Judenstaat conducts several purges of its own: anti-cosmopolitan campaigns. A cosmopolitan is at home in any country, and has no particular loyalty to one. Thus, in Judenstaat, a political enemy is a cosmopolitan, a follower of my Trotsky-figure, Stephen Weiss, who, like Trotsky, is exiled.

Under Stalin, the term “cosmopolitan” was really a code-word for Jew as well as a follower of Trotsky who was a Jew himself. Full disclosure: my husband’s a Trotskyist. He isn’t Jewish, though.

“I don’t think we ever really forget anything. What we can’t bear, we bury.”

MO: I thought your story was a brilliant critique of the political use of historical memory in the Soviet Union and in Israel, without being too allegorical. Can you expand on the use of memory, personal and historical, in Judenstaat?

A Czech academic, Karl Deutsch, defined a nation as a group of people who agree to lie about the past. That’s generally true, but this selective memory feels most pointed in certain countries. Obviously, the two places I had in mind when I wrote Judenstaat were post-Cold War Eastern Europe, and Israel. I spent two years in the Peace Corps in Hungary between 1991-1993, and watched old Soviet monuments being dismantled, street signs changed, and languages like Russian quite literally un-learned. Israel, a country very consciously built on ethnic continuity, makes a point of leaving Arab villages off maps; to be fair, Palestinians do the same thing in reverse. What are they afraid of? Anything that complicates the story. When Judit creates the documentary about Judenstaat, she’s chided by the ghost her her dead husband, part of Judenstaat’s Saxon minority. What does she leave on the cutting room floor?

On a personal level, of course, we also leave things on our cutting room floor, because otherwise, we become paralyzed with anger or regret. Judit can’t move on from her husband’s death. She can’t let go of who they were together. As she pieces together the story of her country, she also pieces together her personal history, and we discover certain memories have been suppressed. I don’t think we ever really forget anything. What we can’t bear, we bury. Turning to Orwell again, like Winston Smith, at the book’s end Judit will eventually face what—to her—is the worst thing in the world, and it will come out of one of those buried memories.

MO: Judenstaat combines the genres of alternative history, mystery, espionage, and thriller for a reflective yet action-packed read. What drew you to genre fiction, and how did you bring together such disparate genres?

I’m not a big reader of mysteries, and absolutely not of thrillers. On the other hand, my novels do usually have plots (I hope) and a classic plot is this: there is a question that needs to be answered by the end of the story. I recently met Ben Winters, the author of Underground Airlines, another “alternative history thriller” about an America where the Civil War never took place, a book with some structural similarities to Judenstaat. We both agreed that writing a mystery allows for good world-building. Detective work allows a writer to include plenty of expository detail. I do need to say, though, that a few years ago, I sent an earlier draft of Judenstaat to an editor who said he liked it but found it “too ruminative, and not visceral enough.” In response, I read The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, a novel with a heroine almost as alienated as Judit. It helped, I think.

MO: What are you working on next?

I had an old friend—and I mean old, like 95 — who needed to find a safe, comfortable place to spend his last few years, and not long afterwards, I also searched for options for my own mother, and I became fascinated by the culture of fancy retirement communities where smart, frail, cranky people are surrounded by soft colors, advanced technology, and euphemisms. The result seems to be a book modeled on Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, his philosophical novel about pre-WWI Europeans at a TB sanatorium. In my case, the book’s The Hill, and like Mann’s characters, my old folks are obsessed with their bodies, represent contemporary trends and types, and live in isolation from a world on the brink of catastrophe. Also, of course, it’s a novel about how we perceive time. Sounds like a bestseller, huh?

I recently met Ben Winters, the author of Underground Airlines, another “alternative history thriller” about an America where the Civil War never took place, a book with some structural similarities to Judenstaat. We both agreed that writing a mystery allows for good world-building. Detective work allows a writer to include plenty of expository detail.

MO: You’ve talked about this in other interviews, but if you don’t mind, tell us how your travels influenced your narrative.

Of course, I traveled more than once to Israel and former East Germany, but by far, the most influential trip was to Vilnius, where I studied in the Yiddish Institute. It was there that I decided that Yiddish was too inherently subversive to be the language of any country. Also, more to the point, I met the Yiddish Institute’s ex-officio director Dovid Katz who was a one-man campaign against Lithuania’s Holocaust obfuscation. Because Lithuanians suffered under the Soviets, they don’t admit their culpability and collaboration with the Nazis, which included the murder of 100,000 people, 70,000 of them Jews, in Ponar. With Dovid Katz and Fania Brantsovsky, a survivor and ghetto fighter, we participated in a semi-secret tour of the Jewish Partisan camp—secret because those anti-Nazi partisans were Communists who welcomed the Soviets and liberators. It was in Vilnius that I had my face thrust into historical and national amnesia in a real way. It was there I found a way to express some of the most important things I wanted to say in my novel.

MO: Judenstaat explores the tension within the Jewish community between religious practice and assimilationist norms, a tension alive and well in American Judaism today. As a tattooed, Bat Mitzvah-ed millennial who mainly engages with her culture by reading books with Jewish themes rather than bothering to go to synagogue, I related to Judit, and her complicated relationship with Jewish history and the “blackhats.” This might be a huge question, but what do you think is the future of Jewish identity?

Here’s a short answer to a complicated question: I believe that the future of Jewish identity must lie in defining our Judaism in ways that aren’t grounded in Israel and the Holocaust. That doesn’t mean we can’t feel ties to Israel, and it certainly doesn’t mean Holocaust denial, but we need to recover other ways of being Jewish—affirmative, compassionate, international, and deeply subversive. I’ve had the privilege of meeting some of your tattooed comrades in West Philadelphia, and to my great delight, they’re learning Yiddish, and more than a few identify as Bundists, Jewish internationalist-socialists who believed in the concept of Doykeyt, which can be translated as “Here-ness.” We are a nationality without national borders, and we make change where we are.

I recently wondered: do I believe in justice?…I don’t know the answer to that question. I do know that we can insist on acknowledging each other’s history, each other’s memories, each other’s suffering. That’s part of recognizing each other’s humanity. That’s a beginning.

MO: Tell us about your portrayal of the Saxons. How much did you want the alternative history of Saxony in your novel to function as a critique of the here-and-now?

When I wrote Judenstaat, of course Israel was on my mind, but Saxons in my Jewish state are not intended to be stand-ins for Palestinians. For one thing, as Germans, Saxons carry collective responsibility for the murder of the Jews. Thus, Judenstaat’s Saxons are, by turns, obsequious and angry because they have something real to bear and to deny. It’s no coincidence that only Judit’s Saxon husband Hans transcends his history because has no knowledge of his parents, and no real tie to the past.

The history of a Jewish state in Palestine and the role of Palestinians in that history is less straightforward. Zionism’s religious implications, the European-Jewish settlers who arrived in a series of increasingly well-organized waves, the battles between visions of ethnic cleansing (think Jabotinsky) and coexistence with Arab neighbors (think Buber) —none of that’s in my book. I dedicated Judenstaat to my old high school history teacher, and he read it, and was disgusted at the country’s compromises and obfuscations, and demanded: “Where’s the voice of opposition?” In short, there’s no Jewish voice in Judenstaat calling for justice for Saxons, as there certainly was for Palestine’s Arabs in Zionism’s early years, and as there is in Israel now —a faint, marginal but genuine Jewish voice against home demolitions and detentions and collective punishment of Palestinians.

Last summer, I went with an interfaith delegation of the Christian Peacemaker Team to Israel and the West Bank. It was mind-blowing, particularly our time in the old city of Hebron. I published some of my observations in Jewish Currents, and given the frustration that seemed to radiate from almost every Palestinian I met, I was in no way surprised at the series of stabbings that began later that year—not an uprising, but the actions of people who have nothing left to lose.

Early in my novel, Hans, Judit’s Saxon husband, tells her that he doesn’t believe in justice. Maybe if he did—given the complicated history of Germans and Jews—he couldn’t function at all. I recently wondered: do I believe in justice? More to the point, in terms of the landmass that constitutes Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank, is justice possible?

I don’t know the answer to that question. I do know that we can insist on acknowledging each other’s history, each other’s memories, each other’s suffering. That’s part of recognizing each other’s humanity. That’s a beginning.

You can find copies of Judenstaat on our shelves and via bookpeople.com.

July 8, 2016

My novel Judenstaat is Orwell Fan Fiction

My hope for Judenstaat that it would find readers. It’s an alternative history about a Jewish state established in Saxony in 1948, with lots of high-nerd, wonky references, and I knew it would not be everybody’s idea of a good time (as one reviewer wrote, “This is a very peculiar book”). Yet, all things considered, it’s gotten some gratifying responses, and people who aren’t my friends and family are reading it—or, according to Goodreads—planning to read it. That’s good news.

Yet so far, not one reviewer or reader seems to have noticed that I stole Judenstaat’s structure from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four.

I suspect that most of my reviewers have read Nineteen Eighty-four. Many of the clearest connections could be classified as spoilers. Yet here, I’ll try my best to delineate a few.

1. Judit Klemmer, the novel’s heroine, works in the Ministry of Truth.

Yes, her workplace is an archive in the National Museum, but like Winston Smith, she’s pushed to edit and omit, to tell a particular state-approved story. As the ghost of her murdered husband puts it, “every time she cuts a frame, she slits a throat.” Like Winston, Judit’s good at her work. Like Winston, she understands that her work is not actually good. Both have a belief in facts– things they can see and touch– which makes them heretics.

2. The black-hats are Proles—living outside the constraints of the state’s official story.

In Nineteen Eighty-four, Proles—the underclass that make up the vast majority of Oceania—live outside the system. It’s in a prole junk-shop that Winston finds the paperweight that is a central image in the novel—a piece of the past. The black-hats, the ultra-orthodox population of Judenstaat, are not yet a majority, but will be soon. It’s in a black-hat junk-shop that Judit finds forbidden photographs and footage.

3. I stole a line completely.

I won’t say which one. Let’s just that—as in Nineteen Eighty-four—it involves a note passed on secretly from someone the protagonist despises, and that it opens up confusion and eventually, leads to some pretty good sex.

4. Then, there’s Emmanuel Goldstein—and Stephen Weiss.

Emmanuel Goldstein, clearly modeled on Leon Trotsky, is the enemy of Big Brother, one of founding members of the Party who is now perceived as its greatest enemy. Stephen Weiss plays the same role in Judenstaat, founder-turned-outcast, feared even in exile. Emmanuel Goldstein has a book. Stephen Weiss has a manifesto. We get to read both, at roughly the same point in each narrative, and both should be read with suspicion. They’re someone’s version of a counter-truth.

5. O’Brien’s in my book, and so are his philosophical arguments.

Take another look at Judit’s old history professor, Anna Lehmann. In many ways, Nineteen Eighty-four is best read as a philosophical novel, as O’Brien convinces Winston that nothing is real. He can float in the air like a soap-bubble. Unlike O’Brien, Anna Lehmann is no torturer, but she shares his belief that there are no such things as facts, only layers of narratives we sort through to select what serves stability and happiness.

6. Finally, what is in Room 101?

If a state is a religion, and personal loyalties are heresy, what breaks a heretic? Orwell makes it clear: the worst thing in the world. In Winston Smith’s case, of course, it’s rats. In Judit Klemmer’s case, it’s something just as visceral. Yes, there’s a room. There’s also a choice. Given what Judit knows—and by that point, Judit knows may things– will she pursue justice?

7. So, do I believe in justice?

It depends on what you mean by justice. The universe—God, nature, whatever you choose to call it—isn’t just. Human beings can be kind to one another, comfort each other, resist the undertow of selfishness and personal revenge. I’m not so sure about nations.

What would justice in Judenstaat look like? What would justice in Israel look like? What would justice in the West Bank and Gaza, in Jordon, in Egypt, in Syria, in America, look like? In every version, something is left on the cutting-room floor.

I believe in the power of memory, and also in a responsibility not to let our memories paralyze u, or make us less curious and engaged with the world. I think we can do things to alleviate suffering. These actions can take many forms, none of them perfect, and none of them, ultimately, perfectly just.

I’ve read and re-read Nineteen Eighty-four a ridiculous number of times. I actually got a facsimile edition from my husband as an engagement present. While I finished the first draft of Judenstaat at Yaddo, I drank my coffee from a Nineteen Eighty-four mug. I feel the burden of that book’s legacy. Orwell, a socialist, did believe that the proles would ultimately understand their own power, rise up, and overthrow the oligarchy. Orwell also was aware of the trajectory of the Soviet Union.

Judenstaat’s ending is happier than Nineteen Eighty-four’s ending, by the way. At least I think so. Judge for yourself.

June 27, 2016

Unanswered Questions from Judenstaat’s Lauch

My mother Laikee with her caretaker Shabby.

My mother Laikee with her caretaker Shabby.A week ago, I launched my alternative history, Judenstaat, at the Free Library of Philadelphia, a book that takes place in a Jewish state carved out of German Saxony in 1948. The event was head-spinningly wonderful, with nearly seventy people attending—former students, writer-friends, work-friends, and folks I hadn’t seen in years. My mother sat in front in her wheel-chair, gazing at me. I could have been speaking Esperanto, and she still would have had a terrific time.

I was introduced by Rabbi Linda Holtzman, and then I read a little, and did a kind of slide-show that explained the origin of the title, Judenstaat (as in Herzl’s 1896 manifesto arguing for a Jewish state), the conception of the book, and its composition. Then, as promised, Linda asked me some questions. So did Harold Gorvine, my old high school history teacher to whom the book is dedicated. The questions were excellent, but as I previously noted, my head was spinning, and I didn’t really answer a few of them completely. I’d like to do so now.

1. How is Judenstaat different from Israel?

Linda Holtzman asked this one, which should have been a soft-ball. I dropped it, and I’ll answer it now.

Rabbi Linda Holtzman had a few questions.

Rabbi Linda Holtzman had a few questions.Both countries were created in 1948. Both countries are Jewish states, with non-Jewish minorities. Both countries have an ideological basis (in the case of Israel, Zionism, and in the case of Judenstaat, a belief that Germany/Ashkenaz is the cradle of Jewish life in Europe). Ah…but location, location…

Israel is, of course, also Zion. When Jews pray, we face the east, and the national anthem Hatikva makes that connection clear. I did explain that when Theodor Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat, he wasn’t set on Zion; in fact, his primary imperative was refuge, not redemption. In spite of what we may think now, Palestine-based Zionism was not really about refuge. In our ancient home, we would become new men and women. As one song put it well, we came to the land to build and be built by it.

My character, Anna Lehmann (my heroine’s college history instructor) is an expert on failed experiments that preceded Judenstaat, particularly the Rothschild colony in Palestine. “Anna Lehmann’s own argument—one that gained currency—was that the messianic element doomed the project from the start. ‘Messianic’ wasn’t even her name it it. It was their own. Palestine Jews believed that in returning to the land mentioned in the scriptures, they would become the agents of their own salvation” (110).

Those claims don’t apply to Judenstaat. In spite of the founders’ hope of a national home for the Jews of Europe, they did not think that this home would make them new men and women. Judenstaat comes with no messianic apparatus. Rather, it comes out of a belief that the the Jews of Europe are German at the root, and they will grow and blossom where they are.

It’s also important to note that, unlike Israel, Judenstaat doesn’t dismiss the Jewishness of Jews who live elsewhere. There is no notion of “Aliyah” or the “Galut.” And yes, of course, there would still be Jews living in Palestine—in Hebron, in Jaffa, in Jerusalem. I can’t know if there would be Arab hostility towards these Jews if there were no substantial Zionist movement. That’s a good question. What do you think?

2. So what makes Judenstaat Jewish?

This one came from Harold Gorvine, quoting Ahad Ha Am, who attended the first Zionist Congress and described himself as “a mourner at a wedding.” Harold looked pretty mournful himself.

Harold Gorvine, the mourner at a wedding.

Harold Gorvine, the mourner at a wedding.This question appears to assume that Israel is inherently Jewish by virtue of its location. Of course, the national language of Hebrew integrates Judaism into culture and politics in complicated, fascinating ways. The national language of Judenstaat is German. For a long time, I debated whether it ought to be Yiddish, as Chabon chose in his own alternative Jewish State in Sitka, Alaska. Ultimately, I decided Yiddish could never be a language of a country with border; it’s all about border-crossing, and therefore, inherently subversive, put probably that’s the subject of another blog post (not to mention a section of my novel called “The Battle of the Languages.”).

Well, here’s something Jewish: facing death and not running, making a home where you are, and creating, as one founder puts it, “a bridge between east and west.” As I constructed my Jewish state, I found myself profoundly drawn to the Bund, a Jewish revolutionary movement committed to Doykeyt, or “here-ness”, envisioning a secular Jewish nationality without a separate country. Jews would stay where they were, and transform their own societies.

1918 poster fro Kiev urging Jews to vote for the Bund immediately following the Russian Revolution.

1918 poster fro Kiev urging Jews to vote for the Bund immediately following the Russian Revolution.What would be Jewish about the transformation that the Bund envisioned? They believed that Jews had separate concerns, and these went beyond a response to Antisemitism. Working class Jews needed separate distinct political and cultural organizations, rooted in our common language and history. We could form alliances with other organizations, yet we must remain distinct. Essentially, the Bund was anti-Zionist, but also anti-assimilationist. Jews would draw on our past, and would play a particular role on the international stage, but we would not disappear, or go to the ends of the earth to Palestine or Uganda. We’d stay right where we are.

In my opinion, nothing is more Jewish than to take the best part of every country we pass through and build a kind of stone-soup culture, mediating, challenging, and synthesizing. Yet, what if that cosmopolitan quality were translated into an actual country with actual borders? Could it be sustained? When Judenstaat is established in territory liberated by the Soviets in 1948, it’s non-aligned. Can that last? You’ll have to read the book.

3. What about spiritual life?

Well, what about it, Harold? (I say now, impatiently). My old instructor and dear friend would be the first to admit that the spiritual life of Jews is not confined, or defined, by a single country. America—not Israel—is where the 20th century Jewish movements like Conservatives, or yet more recently, Reconstructionism and Renewal have flourished.

Satmars who live in Israel protesting the Zionist project

Satmars who live in Israel protesting the Zionist projectIn Israel– though I don’t want to over-simplify a complicated picture— according to its Chief Rabbinate, what we have are orthodox Jews of various stripes in wigs or snoods, in black fedoras or black wide-brimmed, in low-crowed hats, or black fur hats or enormous knitted kippahs– and then there’s everybody else. In a broad sense, no other form of spirituality is legally recognized by the state. In Judenstaat, it’s the same way. Of course, Judenstaat has no settler movement, and therefore no orthodox contingent gathering on hill-tops aiming guns at Palestinians. That means that there are no knitted kippahs. In Judenstaat, Jews wear a black hat, or they wear no hat at all.

Here is what I didn’t say in response to Harold’s question: this dichotomy has a cost, perhaps the same cost that it has in contemporary Israel. When the black-hats take on the full burden of a country’s spiritual life, they have far too much power. They are the shadow cast by the light of Judenstaat’s Age of Reason. They are the living embodiment of the millions who perished senselessly in the Holocaust. They are the objects—in the case of my heroine—of fascination as much as repulsion.

During a life-crisis, my heroine, Judit Klemmer, can not call out to God. She turns inward, fearing her own vulnerability. In particular, she’s disgusted when she’s approached by Chabad, a group of black-hats who reach out to fellow Jews, and try to draw them into spiritual practice. Her response is irrational (though I’ll admit it’s one I share). When you step into the dark, what will you find there? That question gets answered, but not completely, when you read the book.

Judenstaat is a country I invented, and that I inhabited, in my own virtual way, for several years. That’s what writers do. Frankly, I don’t think it’s the best place to be a Jew. Just now, that would be Philadelphia, where I can write books like Judenstaat, and answer these demanding questions.

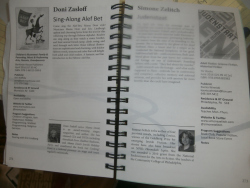

June 11, 2016

Is Alternative History Science Fiction?

My page in the JBC Network booket. Note that I’m across from the Sing-Along Alef Bet.

My page in the JBC Network booket. Note that I’m across from the Sing-Along Alef Bet.Around three weeks ago, I presented my new novel Judenstaat to over 200 members of the Jewish Book Council network in a two-minute pitch. I was one of 270 authors pitching children’s books, cookbooks, biographies of philosophers and rabbis, political analysis, and self-help guides.

The Jewish Book Council assigns us a pitch-coach. Over the phone, I set up my premise: a Jewish state is established in Germany in 1948 as an answer to the Holocaust. Then I said, “And so I give you Judenstaat, a work of Jewish science fiction.”

She asked, “How is this science fiction?”

“Alternative history’s classified as science fiction,” I said. “And my publisher, Tor, is a science fiction press.”

“Okay, but can’t you cut it? It’ll give people the wrong impression.”

The wrong impression? Maybe it made her think of little green men. Still, I didn’t ask her to elaborate; after all, I only had two minutes, and if I cut the phrase, it gave me room for five new words.

Also, honestly, couldn’t answer her initial question. How is Judenstaat science fiction? According to my husband’s enormous analog Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, science fiction is “[f]iction based on imagined future scientific discoveries, major environmental or social changes, etc. freq, involving space or time travel or life on other planets.” Judenstaat doesn’t take place in the future. It takes place in a re-imagined past.

Also, honestly, couldn’t answer her initial question. How is Judenstaat science fiction? According to my husband’s enormous analog Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, science fiction is “[f]iction based on imagined future scientific discoveries, major environmental or social changes, etc. freq, involving space or time travel or life on other planets.” Judenstaat doesn’t take place in the future. It takes place in a re-imagined past.

Theoretically, one might say the science of alternative history has a basis in quantum physics and string theory, in thought experiments like Schrödinger’s cat, who lives in a closed box rigged with randomly administered poison and might simultaneously be dead and alive, and in the endless debate about the nature of parallel universes and the nature of time. My friend, the physicist and author Paul Halpern writes about these issues in his many books (read them!), but I didn’t have physics in mind when I wrote Judenstaat. I had a “what-if” and from that question, I speculated.

It may be more accurate to classify alternative history under the broad category of “speculative fiction,” but that’s awfully squishy. What fiction isn’t speculative? Writers are always asking “what if?” and placing characters in untenable situations to see what will happen next. What if the romance-novel-reading Madame Bovary had an actual love affair? What if Bigger Thomas, who was taught all of his life to fear and loathe and defer to white folks, finds himself alone with the most dangerous creature in the world, a white woman? There’s a kind of cruelty to this Naturalist fiction. These characters are trapped in their age and circumstances. The question is answered from the start. The result feels brutally inevitable.

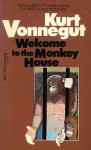

My copy was pretty dog-eared.

My copy was pretty dog-eared.But what if nothing is inevitable? What if the limitations on our lives are arbitrary? What if imagination springs the trap? Most teenagers understand what is meant by a trap, and when I came of age in the ’70s, I read a steady diet of science fiction, Vonnegut, Bradbury, Le Guin, the crazy grab-bags of Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthologies, radical feminist utopias and dystopias. Yes, some of the stories did have little green men (many of them, strangely enough, seemed to be Buddhists).

What really attracted me to science fiction was its generosity. Even at its most pessimistic (and some of it was mighty pessimistic) the story represents one of countless directions we could take. Of course, eventually, I learned to find this generosity in all good fiction, where characters and circumstances have so many layers that they defy easy classification. However, in science fiction, this garden of the forking paths is often built into the work itself, where alternative pasts and futures have the subtle logic of dreams, where traps are sprung, and the path of history itself is theoretical.

‘Nuff said.

‘Nuff said.We’re living in the age of inevitability. We’re told that that increased surveillance is inevitable, that out-sourcing is inevitable, that closing of independent bookstores and the triumph of Amazon is inevitable, that global warming is inevitable, and certain political candidates are inevitable. We’re told to get with the program. Science fiction, by definition, does not get with the program. In fact— forgive the non-linear metaphor—science fiction changes the channel.

So given what I wrote above, yes, alternative histories are science fiction. They challenge the natural order of things, make the reader feel displaced and uncomfortable, and do not bow down to false gods. There are no little green men in Judenstaat. Sometimes I wish there were. Their spaceship would land in the Dresden Opera House and cause a great sensation, and they would insist that the citizens of Judenstaat are living in the wrong reality. A Jewish state actually exists in Israel, and they plan to teleport the audience and use them as slave-labor to rebuild the Holy Temple. Then, the tuba-player could step on one They’re little, after all.

May 31, 2016

A Professor and his Muse

Professor Joseph Kenyon, clearly during Community College of Philadelphia’s winter break

Professor Joseph Kenyon, clearly during Community College of Philadelphia’s winter breakI’ve known and admired Joseph Kenyon as my colleague at Community College of Philadelphia, and I’m proud to have an opportunity to let readers know about this debut novel, All the Living and the Dead.

The novel centers on a students in a secret society in the “German Romantic mode”. The members are Romantics with a capital R, believing in pure, artistic genius and the power of inspiration. They’re young and passionate; some of them are wildly talented, and some are still finding their way. Gaston, Lyle and Autumn are all at the start of their careers. Then there’s professor and composer Quinn Gravesend, who believes that he lost his youth and passion long ago Do we reach a point where vitality gives way to weariness?

These artists are all searching for something elusive and half-mythic: inspiration. Where do we find it? How does it change us? Do we need to cross lines, break taboos, redefine terms, and essentially be reborn?

I had the chance to ask Joe Kenyon some questions recently by email. Below find his responses.

All the Living and the Dead has an academic setting. As a long-time teacher, what interested you about this setting, and in particular the interaction between faculty and students?

I’m a long-time teacher now, but when I first started thinking about this novel, I was a rookie, an adjunct teaching part-time in several community colleges in the Pittsburgh area. I was quickly fascinated by the way the young women interacted with male faculty members who were in their 40s and 50s.

Of course, there were teachers who used their powers in ways that they shouldn’t have, but I was more interested in the teachers who drew the line. And all the time I was learning as a teacher how to deal with the various feminine – and masculine – wiles, I was thinking as a writer “What if it didn’t work? What if the female student found a chink in the teacher’s armor?

Did you begin writing with some knowledge of music and the process of composition?

This novel’s about music and time, and so is the cover.

This novel’s about music and time, and so is the cover. Musically, I was your typical 70s kid who loved classic rock, but when I was seventeen, an older fellow on my softball team turned me on to Mussorgsky’s Pictures At An Exhibition (conducted by Philly’s Eugene Ormandy). I had heard Emerson, Lake, and Palmer’s version, but the original just blew me away. That began my love of classical music. Still, I was nothing more than a fan. I had (and have!) less than average musical talent.

So, I fell back on the writer’s two best friends: Research and Imagination. I talked to a lot of musicians who wrote their own stuff. I talked with music professors who wrote classical pieces. Then I just did what I always do – method writing. I became Quinn and Gaston and Lyle and played their parts like an actor would.

I have to admit that while a lot of people seemed to be impressed with my knowledge of musical composition, I played a bit of a magician’s game there. If you really read those sections closely, you’ll notice that I actually said very little about the composition of music. Other than songs that I know (such as “Epona” or “Hallelujah”) the descriptions quickly move out of the realm of music and into sensory perception – a discussion of the emotion surrounding the music or the reaction of the audience. One-on-one with Autumn, Quinn references some compositional techniques (“…try the arpeggio”), but like with anything we write, only a pinch is needed to season the entire scene.

In my own testimonial, I wrote that All the Living and the Dead is a quest narrative. I know that you have an on-going interest in mythology. Did you have any myths or archetypal stories in mind as you wrote this novel?

Having been steeped in mythology for a lot of my life, it’s never far from my mind. I was once asked why I didn’t write fantasy and my response is that I’ve always been interested in how myth reveals itself in everyday life, at the intersection of Broad and Market rather than at the intersection of the forest and the mist.

Before I began writing All The Living And The Dead, back when it was just an interesting idea, I was reading a lot of works about myth and psychology (Jung and Downing, mainly), and—bang!—suddenly I realized that the feminine archetypes they were discussing were dancing in front of me in the classroom: The Daughter looking for a lost father-figure, the Free Spirit who is unrestrained by traditional boundaries, the Maiden (or girl next door) who is sweet and wholesome, the Nurturer who only wanted to help, and of course the Seductress.

Originally, Autumn was drawn as a quiet, mystical young woman who enticed Quinn, but that was all wrong. It took several drafts before the Autumn you see in the book emerged.

As for the quest narrative, I felt greatly complimented that you saw the book in those terms. When I read your comment, I mulled it over, and came to the idea that every plot is a quest narrative to some degree. The quest may be emotional, psychological, artistic, or self-serving, but characters have to want something bad enough to go and get it, even if “going and getting it” involves only a trip inside themselves.

You’ve published both fiction and poetry. Is the process of writing different for these different forms? Do they influence each other?

They are very different. I write poetry when I can’t think of any other medium in which to

Joe Kenyon’s website contains links to some of his published

Joe Kenyon’s website contains links to some of his publisheddescribe what I’m seeing and feeling. A poet once told me that any poem that doesn’t have to be written shouldn’t be written. Poetry, for me, has its roots in the emotional spectrum. However, my fiction is planted in the curious or intellectual side of my brain. My stories start with an idea or a character that intrigues me enough to want to explore it further. I want to know the story behind that idea or character. Then, I’m off.

The influence of poetry on my fiction is palpable. I wrote fiction for about a decade before I

There are a few stories on the website as well.

There are a few stories on the website as well.started writing poetry, and while I published a few stories, I would say my writing wasn’t very good. Since I started writing poetry, I’ve become much more conscious of word choice, much more economical in my descriptions. Poetry continues to inform my fiction.

However, the current only flows one way, I’m afraid. I’ve tried to write some “story” poems, but they ended up as flash fiction pieces. I really can’t think of any way my fiction informs my poetry.

What is a question you wish someone would ask you about this book?

Readers are very curious about the relationship between Autumn and Quinn, and a few have asked about Lyle. But no one asks about Gaston. So, I guess the question I would like someone to ask is: “Where does Gaston fit in? He’s an insider but seems like an outsider.”

Gaston is easy to overlook because he seems to be so far above everyone else. He has a special affinity for Lyle, and he lives with Autumn, but you really get a sense that it doesn’t matter whom he’s with or where he lives – Gaston resides inside himself and in his music.

And yet, there is a boyish innocence to him. He is this man-child, superior to even Quinn in some ways, but that’s what makes Gaston needy. The scariest thing about being at the top of the heap is that there is no one above you, no one who’s been where you are and can offer some perspective. That’s the entire mission behind Mensa – to give geniuses a sense that they aren’t alone.

It’s easy to look at Gaston and say “genius” and let that explain his aloneness, but his scenes with Quinn belie the simplicity of that idea. He takes off his sunglasses for only one person – Quinn. He recognizes Quinn’s distraction as “working,” and his question sets off the only discussion Gaston has in the entire book where you get the sense he is talking to an equal. Most revealing of all is when he holds out his guitar for Quinn to autograph. Imagine that from Gaston’s perspective. Finally, he gets to be a fan. He looks up and there is someone above him. For Gaston, that has to be such a significant moment.

Finally, he is the one character in the book based on someone I used to know, a guitarist I went to school with who could play almost anything on the guitar. Gaston is far more advanced in his genius then the model, but still, the base of Gaston Gunn lives in this fellow, an hommage to someone I admired in my youth.

What’s next for you?

I have drafted another novel, which begins in World War 2 Italy, about an eccentric painter and a maimed girl and the parallel lives they live. It’s been laid in the cellar to age a bit before I bring it out and see if it’s really ready to drink. In the meantime, I’m taking the summer to reacquaint myself with my Muse, who has been on a rather long holiday while I’ve been involved in the publishing process and finishing the semester. Wherever she leads me – and she’s given me a few hints – that’s where I’m going to go.

For more information about Joseph Kenyon, check out his website at http://www.josephkenyonlit.com/

May 23, 2016

But is it relatable?

In my creative writing class last spring, along with my Amazon boycott, another running theme that amused my students was my disapproval of the word “relatable”. Like, first of all, is it even a word? And more to the point, when applied to writing, it seemed to reward stock situations and stock characters. The term felt reductive and lazy, along the lines of justifying a cliche because it’s “true.”

Pitch outfit without the earrings and lipstick.

Pitch outfit without the earrings and lipstick.Yet how else do we enter strange things, really? These days, with Judenstaat about to launch in a month, as I prepare to pitch my book to the Jewish Book Council, I find myself haunted by the term “relatable.” How do I invite readers inside my weird new book?

In two days, I will do my best to impersonate someone relatable, wearing “business casual” and opening my two-minute pitch this way: “One night, I was lying in bed with my husband Doug and suddenly asked ‘What if a Jewish state was established in Germany instead of Israel in 1948?'” Do you have a husband? Do you talk in bed? Then you can’t be alienated or offended. I’m like you.

The novel is what might be called “high concept”, and in fact in the eight years it took me to shape it into publishable form, it moved beyond its premise and became a kind of thriller where a widow stalks her husband’s assassin through the streets of Dresden.

The novel is what might be called “high concept”, and in fact in the eight years it took me to shape it into publishable form, it moved beyond its premise and became a kind of thriller where a widow stalks her husband’s assassin through the streets of Dresden.

But why should we care who killed her husband? What on earth makes a reader take the leap into speculative history, particularly when, frankly, the history’s dependent on some understanding of the history of the second half of the twentieth century, but turns it sideways, or maybe inside out?

I suspect that many questions about Judenstaat will focus on that history, but frankly, creating the history was the easy part. The really hard work was finding the story, in particular figuring out my widow, a stubbornly opaque historian who can’t live in the present, and who’s pulled out of her memories and grief by forces it took me a long time to understand.

On the other hand, I recognize the memories and grief. Over time, I discovered how her life intertwined and diverged from my own, and the intersections were my own bridge into strangeness: the touch of her husband’s hand in her hair, the manic sewing and and unraveling and re-sewing of a seam after a miscarriage, a stone on a father’s grave.

In the end, as ever, I give my students credit. I continue to value strangeness, and the frisson of energy we feel when we take a leap into unfamiliar territory. Yet what makes us leap is empathy. Sure, my novel’s about an imaginary country established as an answer to the Holocaust, but ultimately it’s about a haunted woman who has lost everything and needs to go on living.

Can you relate?

May 11, 2016

The Future

Around two weeks ago, I collected thirty-page manuscripts from students in my college’s capstone creative writing course, Portfolio Development.

The work appeared– as I required– in enormous binders, which involved creative variation on three-hole punching or plastic sleeves, and the final versions were contextualized by drafts, supplemented by artist statements or query letters and their drafts, and multiple copies with the comments of their classmates.

Amanda, the student most likely to use a typewriter.

Amanda, the student most likely to use a typewriter.Probably most people reading this blog post would consider me insane. Why not have students do all of this online, comments and drafts included? They’d say, “It would save trees.” I’d counter with graveyards of obsolete computers in Third World landfills. They’d say, “It would be more efficient.” I’d counter with plenty of stories about files that don’t load or get erased entirely.

All of that aside, here’s the truth of the matter. I’m just odd, old-fashioned, and analog. But I was assigned to teach a course about “the writing life” which, to my mind, involves not only writing, but a good deal of reading, as well as research on a publishing landscape which is changing in directions I find terrifying.

Francisca, Kerrie, Michael, Carmella and Rachel had all taken at least two other classes together; as a consequence, they could pretty much finish each other’s sentences.

Francisca, Kerrie, Michael, Carmella and Rachel had all taken at least two other classes together; as a consequence, they could pretty much finish each other’s sentences.I love my students. Most of them knew each other from former creative writing classes, and they reminded me of a basket full of happy puppies, climbing all over each other, showing up long before class began, sharing pictures on their smartphones, talking about who-knows-what, maybe something literary.

So…I started coming early too. And they stopped talking. Mostly. I might have imagined it. In any event, I would putter around awkwardly with my big stacks of analog debris, and try not to get in the way.

Is it a good thing when your students love each other more than they love you?

At some point, I understood that for most of these students, their concerns were not my concerns. Their hopes were not my hopes. And most of all, their fears were not my fears. My boycott of Amazon was something of a running joke. For many of them, self-publishing was not only a viable option, but preferable to wrangling with a corporation which would essentially own their work. They are optimistic where I’m cranky. More to the point, they are open where I’m closed.

I gave away some books at the end of the semester, including this one. Alan is pictured here. He read 600 pages of Charles Bukowski.

I gave away some books at the end of the semester, including this one. Alan is pictured here. He read 600 pages of Charles Bukowski.So what could I do? I can’t pretend to be someone I’m not. Ultimately, I can demand coherence, precision, and deliberate choices. Most of all, I can insist that they read and read in ways that can inform those choices, and push them to revise and revise. But how much difference will those factors make in the years to come when everything is uploaded, and content is always free and never fixed?

Students, I admire you. I promised you a blog post, and I know you’ll read this as I intend it to be read, as a tribute. After that final class,you exchanged phone numbers, and I dragged my box of binders home, feeling a little blue. You’ll go where I can’t go. You’ll do what I can’t do. I also fear for you in ways you can’t fear for yourselves, maybe.

I returned the portfolios to my students last week in my office, a few days before graduation. The final conferences were enormously gratifying. One-on-one, we didn’t talk about the future of publishing. We talked about the future of their work, in detail. Michael will keep gathering followers on his food blog but will also go to Panama to research his novel-in-progress. Francina already has thousands of readers of her book Real Muslim Housewives of Philadelphia but is determined to apply what she has learned about the craft of fiction to make the book meet her own exacting standards.

In the end, what I have to give my students isn’t any special knowledge about the changing landscape of publishing. I can give them the quality of attention they deserve which, in this fragmented world, may be a rare thing.

Ultimately, no market can determine a writer’s aspirations. Maybe a teacher helps a little. And more to the point, my former students will support each other in forms I can barely imagine.

January 24, 2016

For David Hartwell

On Friday, I was getting ready for the blizzard which was scheduled to start that night. But we all know that blizzards can’t be scheduled. They run on their own clock; they lift days out of context; they up-end intentions. In short, they make time stop.

Snow begins on Wissahickon bridge a few blocks from my house.

Snow begins on Wissahickon bridge a few blocks from my house.Sometimes, a blizzard is a gift to writers, at least if we have good insulation and a solid roof over our heads. As long as snow accumulates, we can’t do much but write. With that in mind, early Friday morning, I made a point of answering all school-related email to clear a path.

That’s when I got the email message from my agent with the subject heading: “Shelf Awareness Pro for Friday, January 22nd”. Given the punctuation, what followed was very likely typed from her phone:

“Very sad and very sudden. We lost our editor David Hartwell from a sudden Accident last night from which he did not recover.”

Below was the obituary. I just stared at the screen, wanting it to say something else.

***

David Hartwell sent me a contract to publish my novel Judenstaat with Tor Books almost exactly a year ago. I’d sent him the manuscript on the recommendation of Terry Bisson, another writer of alternative history who thought the book would be a good match for Hartwell. And it was—to the point where he accepted it without additional edits. I found an excuse to meet him in New York last March when we were scheduled for a “long lunch” and he told me about how much fun it would be to figure out how to market my book.

I’ll admit that I’d never before heard “fun” and “market” in the same sentence. Yet Hartwell was clearly a happy warrior. As Phillip K. Dick’s literary executor, and a senior editor at Tor, he had been shaping the direction of Science Fiction for a generation. He was also distinctly old-fashioned. He said I shouldn’t bother with a Twitter account because the audience for my novel wasn’t likely to tweet. On the other hand, they’d read Facebook. “I’ll friend you,” he said, “so I can see what you’re up to.”

David Hartwell on Facebook

David Hartwell on FacebookAlthough David Hartwell was born in Massachusetts, there always seemed—to me—something distinctly Western about him. Maybe it was because he wears a cowboy hat in his Facebook Profile picture. More likely it was a kind of expansive generosity that makes me think of a mountain range. He’d wanted to introduce me to Chip Delany, and casually mentioned that he would try to get a copy of my book to Jonathan Lethem and Michael Chabon. I didn’t push it. Frankly, I was more than a little dazzled by the company he kept. I was never dazzled by David himself, though. Maybe I should have been. I’d only begun to understand what Hartwell had accomplished. I’m still learning.

***

The author at an impressionable age…

The author at an impressionable age…Growing up in the ‘70s, you could say I lived in the shadow of the Hartwell mountain range. Like many other misfits of my generation, I devoured Vonnegut, moved seamlessly to anything resembling a dystopia, and read those books until I broke their spines. Was I avoiding my own troubles? Actually, those troubles were right there on the page, mundane and brutal: in the world in which everyone was finally equal and Harrison Bergeron’s parents sat in front of a television, watching their genius-renegade son tear the weights off a ballerina; or in London 635 AF (After Ford) where Bernard the scrawny Alpha hears his tall and perfect fellow-Alphas whisper about the alcohol dropped into his test tube during gestation; or as the child in the cellar moans in the midst of the glorious happiness of Omelas; or in the Ministry of Truth where Winston Smith erases an unperson from the public record.

What Vonnegut, Huxley, Le Guin and Orwell taught me was this: If everything runs smoothly, you can be sure something terrible is going on, and eventually someone will get chewed up in the cogs of the machine. In theory, these pieces are speculating about imaginary worlds or futures , but make no apologies for referencing the present, whether it be in 1961, 1932, 1973 or 1948, and also, somehow, they are writing about the life and prospects of an overweight teenage Jewish girl in in Northeast Philadelphia. Even at their most hopeless, as Orwell seems to be in Nineteen Eighty-four, the authors are intensely angry, and they gave me courage.

Most of all, I learned that I was not alone. Philip K. Dick in particular was a champion for those of us who are—let us say—wired differently, the easily distracted kids, the non-linear thinkers, the ones who are now classified, rather delicately as “on the spectrum”. Dick was also fond of schizophrenics. For him, difference wasn’t a disability. It was a superpower. So you think I have to fit in? Fit into what? You say I need to face reality? I’ll call your bluff. Sir, there are multiple realities, layer upon layer of them, each with its own logic and chain of consequences. Which reality, exactly? Tell me, and then, I’ll face the opposite direction.

Most of all, I learned that I was not alone. Philip K. Dick in particular was a champion for those of us who are—let us say—wired differently, the easily distracted kids, the non-linear thinkers, the ones who are now classified, rather delicately as “on the spectrum”. Dick was also fond of schizophrenics. For him, difference wasn’t a disability. It was a superpower. So you think I have to fit in? Fit into what? You say I need to face reality? I’ll call your bluff. Sir, there are multiple realities, layer upon layer of them, each with its own logic and chain of consequences. Which reality, exactly? Tell me, and then, I’ll face the opposite direction.

***

Now it’s Sunday afternoon. The blizzard ended late last night, and my stepdaughter used a tape-measure, and reported an accumulation of twenty inches. The soft, clean, frankly dazzling snow that blew against our windows has become an obstacle. We tried to dig out the car, and there was nowhere rational to put the snow we shoveled without burying something else. I shook snow out of the trouser-cuffs and went upstairs to write this for a man I had only just begun to know, yet in some ways, had known all my life.