Elizabeth Mitchell's Blog, page 2

November 27, 2016

#FerranteFever: What’s fueling the passion for these captivating novels — and turning their secretive creator Elena Ferrante into a superhero?

THE MYSTERIOUS AUTHOR who goes by Elena Ferrante first discussed her idea for a novel that would become the now-legendary Neapolitan series with her Italian publishers over a lakeside lunch on a sunny summer afternoon in 2009.

“She told us that she wanted to write the story of two friends, middle-aged, and in Naples,” recalls Sandra Ozzola Ferri, Ferrante’s editor and the co-founder, with husband Sandro Ferri, of the Italian publishing house Edizioni E/O. Ferrante had been thinking about her own relationship with a friend who had died, and had envisioned a pivotal wedding scene. Most of the novel’s characters are gathered in one tableau, a group the narrator, Elena, hopes to escape. Sandra continues: “When Elena looks at the crowd and says, ‘Ah, these are the plebes, the ignorant ones and, not only poor, but vulgar.’ Everything is dirty — the floor, the people — and she is really very frightened. This is what she wanted. It was practically one of her first ideas.”

It took Ferrante less than five years to create her epic tale, which sprawls to nearly 1,700 pages. Her impulse to conjure her deceased friend had wired her to crowds of other ghosts, political street violence, abusive industrial conditions, birth, death and betrayal. Sometimes the writing would go so smoothly, she would carry on for 50 to 100 pages without going back to reread or rewrite.

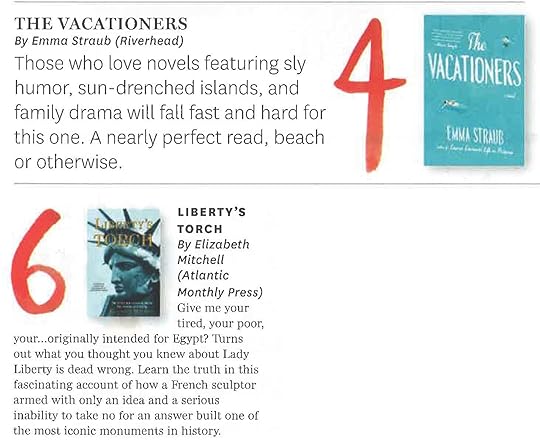

Sandra recalls how odd it was that Ferrante wrote what is now being called a masterpiece with no outline. “She had only the beginning and the end,” Sandra says.

“Practically no notes,” Sandro Ferri adds. “Only in her head.”

READ MORE: ELENA FERRANTE AND THE QUESTION OF ANONYMITY

When Ferrante had gotten approximately two years into the writing — and with the submission date for the manuscript fast approaching — she admitted that she may have underestimated the project’s scope. The novel already stretched to 400 pages — and the two protagonists had only reached the age of 16.

“She said, ‘What should I do?’ ” Sandra Ferri recalls. “And we said, ‘OK, we will publish this, and after, you continue.’ ”

The publishers ultimately decided to release the entirety as a four-volume series, but even in the introductory chapters they could see that the work was extraordinary, in need of only nominal editing. “It was already very, very well done,” Sandra says. “Immediately.”

TOP SECRET Left, Edizioni E/O publishers Sandro and Sandra Ferri are the only known people to know Ferrante’s true identity. Right, Sandra (center) and Sandro in E/O’s early days, with publicist Nennella Bonaiuto.

(EUROPA EDITIONS, THE U.S. IMPRINT OF E/O )

(EUROPA EDITIONS, THE U.S. IMPRINT OF E/O)

TOP SECRET Left, Edizioni E/O publishers Sandro and Sandra Ferri are the only known people to know Ferrante’s true identity. Right, Sandra (center) and Sandro in E/O’s early days, with publicist Nennella Bonaiuto.

Fast-forward to 2015, some six years after Ferrante shared her ideas with the Ferris over ravioli and wine. Fans of her work have crowded the marble arcade foyer of the New York Public Library’s main branch, clustering close to the stage for a bit of proximity, even in its remote form, to the author. It is not Ferrante they have come to hear, but Ann Goldstein, the translator for all of Ferrante’s work into English, who holds the stage for a noontime talk.

The Neapolitan series — which tracks the lifelong friendship between two women, the narrator Elena, who is referred to by her nickname, Lenù, and her best friend Lila, from their childhood in a rough Naples neighborhood through their late sixties, when Lila disappears — has burnished Ferrante’s legend. (The fourth and final volume, “The Story of the Lost Child,” which was released here in September, has appeared on more than 20 year-end best-of lists.) As her fans multiply and the book garners worldwide acclaim readers have been lionizing Ferrante, elevating her status to something verging on superhero. And why not? She possesses the key traits of a superhero: extraordinary gifts, a strong moral code and a veiled identity. All in all, it’s a unique combination of attributes.

The audience has so many questions for Goldstein about Ferrante and her work, and the translator answers what she can. She has never met the author. When she needs to ask Ferrante a question — which is rare — she does so through email, forwarded by the publisher. As Goldstein concludes, the fans line up and wait for her to sign their copies of the four-volume series; although Goldstein has been translating for 23 years, this is the first work for which she has been asked that favor.

“That’s the most amazing thing about the books,” says Goldstein, who seems somewhat stunned to be summoned from her quiet life as head of The New Yorker copy editing department and part-time translator to stand as surrogate for the reclusive author. “There is this endless appetite to talk about them.”

And that appetite keeps growing, along with the phenomenon of the author’s explosive popularity, dubbed #FerranteFever by ProPublica reporter Lois Beckett in December 2013, on her personal Twitter account. The series’ first book landed on the New York Times Best Sellers list in the U.S. as recently as September 2015 (it’s currently ranked No. 2 on the paperback trade fiction list, and No. 20 on the combined fiction categories). U.S. readers have already purchased 780,000 volumes from the series, and interest is surging: By the end of the year, sales for each book in the series had doubled those of the previous month.

Translation rights have been granted in 42 languages; and while only a dozen or so publishers have released the first book so far, it has already risen to a number of best-seller lists. That adds up to an estimated 2 million in sales to date, chiefly in Italy, Spain, the U.S., the U.K. and Australia, the only countries in which the full series is offered (with some 30 countries yet to begin).

There are myriad accounts of Ferrante’s blossoming appeal. The owner of a used bookstore in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, warns that it’s increasingly difficult to find one of her novels on the shelves. “We carried (Ferrante) for years and couldn’t sell her; now, we can’t keep her in the store,” he says. “She’s the hottest thing around.”

This is to adult women of a certain ilk as Harry Potter was to kids,” says Sara Nelson, Amazon editorial director. “I can’t remember the last time people talked about characters in a book as if they knew them.

In a Columbia University meeting room, a mixed-age, mixed-gender audience crowds in for a panel discussion of Ferrante. As the event’s start time nears, more attendees begin to cluster at the door and are forced, finally, into a spillover room with piped-in video. Readers have sold out similar events, including one at the 760-seat Symphony Space in New York City. The Center for Fiction forgot to turn off its reservation hotline for a scheduled Ferrante event and, by the next morning, found it necessary to change the venue after ticket requests had exceeded capacity.

Such soaring demand is extraordinary in the world of books, where just a small group of decorated celebrity authors can command standing-room–only crowds. What makes this even more amazing is that the author, who fiercely guards her privacy and anonymity — is Elena Ferrante a pseudonym or could it be the author’s real name? — will never, by her own decree, make an appearance in public. She is the antidote to the Instagram age of shameless self-promotion. She refuses to publicly hawk her books: no events, no signings, no award-ceremony speeches, no interviews on television or radio. Only her editor and publisher in Italy, as far as anyone knows, have met her. Amazingly, people just want to talk about her books — and they can’t get enough.

***

WHY IS FERRANTE FEVER so contagious? For starters, there is Ferrante’s rich subject matter and her vividly rendered protagonists. It’s difficult to recall an epic story having been written about friendship between two women. Ever. That is shocking and also makes this series uniquely compelling. Lenù is the cautious, studious narrator. Lila, a daring, brilliant but ultimately enigmatic character, is Lenù’s obsession, her greatest champion, her biggest rival, the model for what Lenù’s life would be, both for good and bad, if Lenù weren’t so timid, so unsure of what she really wants.

The power Ferrante has to depict how women really think, move and fight, drills unusually close to the bone. These women act without the delusion of deciding; they resent without feeling resentment. They are highly intelligent, canny and physical.

When Lila is introduced on the first page of the first chapter, she isn’t described by appearance, as most female characters would be. She’s all action, thrusting her hand and arm into a black manhole, climbing up to a ground-floor window, hanging from a clothesline bar, swinging back and forth and ultimately sticking a rusty safety pin into her skin. And that’s just the first page.

That same muscular prose carries through all the buoying and buffeting of the two women’s lives — through poverty, abuse, love, sexism, lust, motherhood, politics, aging, daily tedium and the women’s own frailties, until you come to the haunting conclusion.

“We are dealing with masterpieces here,” Time’s Joe Klein wrote in his review of Ferrante’s work.

Charles Finch went even further in his review in the Chicago Tribune . “What words do you save?” he wrote. “Here’s your chance to bring them out, like the silver for the wedding of the first-born: genius, tour de force, masterpiece. … At least within all that I’ve read, (the Neapolitan novels stand) to be the greatest achievement in fiction of the post-war era.”

The first volume of the series, “My Brilliant Friend,” was published in Italy in 2011. It came out in the U.S. in 2012, with a modest print run of 12,000. Two subsequent volumes — “The Story of a New Name” and “Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay” — appeared in each of the following years. Word that the U.S. publication of the final installment, “The Story of the Lost Child,” would be coming in September 2015, sparked an uptick in sales of the second and third books in July and August. The fourth volume hit the best-seller list in September, and it was soon joined by the first book, which had climbed to No. 2 by the end of the year.

COVER STORY Though the jackets telegraph “chick lit” — a tactical (and controversial) choice by the publishers — the books deliver a riveting reading experience.

COVER STORY Though the jackets telegraph “chick lit” — a tactical (and controversial) choice by the publishers — the books deliver a riveting reading experience. (EUROPA EDITIONS, THE U.S. IMPRINT OF E/O)

Due to the series’ epic reach, the books can seemingly provide something for every kind of reader. The book jackets telegraph “chick lit” — a tactical (and controversial) choice by the publishers — but the writing delivers a riveting reading experience without pandering. For those seeking entertainment, the books are, for the most part, page-turners: “This morning Rino telephoned. I thought he wanted money again and I was ready to say no,” “My Brilliant Friend” begins. “But that was not the reason for the phone call: his mother was gone.”

Women will find a thoroughly unique, honest account of female friendship as the two protagonists trade praise, envy, boyfriends, children and achievements. Some readers will appreciate the ground-level look at what sparks political revolutions, and the casualties they leave behind. Ideological debates at the house of Lenù’s high-school teacher migrate into the streets, putting bodies behind the words, first to rallies, then at the factory where Lila ends up working and finally underground. Once Lenù becomes a writer, she must constantly weigh whether her articles contribute to repairing the miserable conditions of the working poor, or if she is only looking to feed her ego by appearing serious.

Literary types praise the style, calling it clear, confident and sober. Book groups have plenty to debate in the psychological motivations of a cast of more than three dozen characters who oscillate between love and selfishness.

“Maybe this is to adult women of a certain ilk as Harry Potter was to kids,” says Sara Nelson, who has seen her share of popular books as the editorial director at Amazon and, formerly, as the editor-in-chief of Publishers Weekly. “I can’t remember the last time people talked about characters in a book as if they knew them.”

The passion for the series creeps pop-ward, and the coterie of well-known fans attests to the works’ varied appeal. Big U.S. directors and producers have begged for the movie rights. Twitter lights up with #FerranteFever. One reader tweets: “When Ethan Hawke is the third person in a week to recommend the Elena Ferrante books to you, you buy them.” James Franco poses on Instagram holding up the first book in the series; in another, he gazes into the camera wearing earbuds, and confesses to listening to Ferrante on set. (His followers, primarily female, reward him: “You have the best lips.”)

FERRANTE FANATIC Actor James Franco is one of many well-known fans who don’t hide their zeal for the author.

FERRANTE FANATIC Actor James Franco is one of many well-known fans who don’t hide their zeal for the author. (INSTAGRAM)

Porn star Stoya reveals that she was deep into the third volume of the Neapolitan series the night before she decided to go public with allegations of abuse against her former boyfriend and sometimes co-star James Deen. Chris Hayes of “All In” on MSNBC tweets, “Thanksgiving conversation running about 80% Elena Ferrante, 20% Trump.”

Libraries can’t keep the book on the shelves. “I am 31st in the reserve queue for checking out the first Elena Ferrante novel from the library,” a would-be reader laments on Twitter, punctuating it with an emoticon of grief. A U.K. reader says she is 93rd in line. In Oakland, Calif., a reader testifies that she has waited six months to get a library copy.

Readers hungry to gain insight about the mysterious author have made pilgrimages to Naples, where they visit the locations named in the book by way of retracing her steps. A thread on Trip Advisor compares notes on the location of Lenù’s school, or which rough neighborhood could be the one in which Lenù and Lila were reared. On a steamy day last July, Louise Erdrich, author of 14 novels, poet, and winner of the National Book Award and Library of Congress prize for American fiction, found herself rambling across Naples with her daughter, Aza, trying to find the landmarks and piazzas of the Neapolitan series.

At the time, Erdrich was mid-way through the series, though she recalls the difficulty even she had trying to borrow the first volume from the Minneapolis bookstore she owns. “Every time I brought ‘My Brilliant Friend’ home, the bookstore would immediately call and tell me that we’d run out. Could I bring back my copy immediately?

“Once I finally began ‘My Brilliant Friend,’ I had great trouble restraining myself from reading straight through all of the books,” Erdrich continues. “It was the same with Aza. On this trip, we read constantly, whenever we had time.”

Limping back to the hotel, they fell back to the books with, as Erdrich puts it, “the Castel dell’Ovo lighted dramatically, across from us, against the sea.… All in all, it was one of the best reading experiences of my life.”

The last description might suggest that the books include the usual Italian catnip of gorgeous scenery or sumptuous food, but in fact they are noticeably lacking in those pleasures: This is an Italy more akin to Cleveland.

That is just another way the books upend all expectations of what readers typically desire. The book industry is accustomed to mega-hits from titillating fare such as “Fifty Shades of Grey,” but this is a series in translation, a nearly 1,700-page opus in an era when readers supposedly avoid longer texts; a novel that navigates through fiery political history, and essentially, stone by stone, crafts the emotional ramparts for an internal female resistance to sexism in all of its forms. These books are published by a small house in Italy with only 15 employees, and in the U.S., by its 10-year-old affiliate, which counts only three full-time staffers. They’re released with no advertising.

Over the years, I’ve lost all my curiosity about her true identity,” says Ferrante’s U.S. publisher. “She has generated such a vivid sense of her presence. I don’t need the details.

Lisa Gozashti, co-owner of Brookline Booksmith outside of Boston, says that business is booming and the Neapolitan series is partly responsible for what seems like a reading renaissance. “For our population — which are a lot of thoughtful, engaged people, many of them middle-aged and older — it’s been incredibly compelling,” she says. “The writing is fresh. People are very, very hungry for that kind of simple truth-telling, which is also brilliant. (Ferrante) is living a fully engaged life, not looking to see if she is matching up to Mrs. Jones or anyone else, radically finding her own truth in the world, full-on, caring about nothing else. And that is very inspiring for most people today.”

If Gozashti speaks as if she knows Ferrante, she can only derive that understanding through Ferrante’s books and through the spare written interviews the author dispenses, now limited to one per country, per book.

Not even Michael Reynolds, the editor-in-chief of Europa Editions, the U.S. affiliate of her Italian publishing house, knows who Ferrante is, although he has spent 10 years working on her behalf. “I don’t want to meet her,” he says. “I try not to write to her. Over the years, I’ve lost all my curiosity about her true identity. She has generated so fully this strong and vivid sense of her presence, I don’t need the details.”

***

THE CLOSEST ONE can get to the physical being of Elena Ferrante is to meet with Sandra and Sandro Ferri, the married co-founders of E/O. Without them, it is almost a given that Elena Ferrante would never be read at all, at least in her lifetime. Publishing her work, the writer has stated, is not crucially important to her. She wrote for many years before she felt she had a manuscript worth submitting, her first novella, “Troubling Love,” published in Italy in 1992. She chose the Ferris because of her admiration for the serious foreign literature they have been putting out since 1979 (before Ferrante, they had never published an Italian writer).

The Ferris weren’t angling for commercial success with her work. E/O germinated from a desire to better the world, in whatever way they could. Sandro had been a member of a radical workers’ rights group, Lotta Continua (Struggle Continues), and the two met during the time that he owned a left-wing bookstore, La Vecchia Talpa (the Old Mole), in Rome. Ferrante may very well have been part of that scene, since the promises and betrayals of the period figure prominently in the Neapolitan series.

What started out for the Ferris as an educational effort to smuggle manuscripts out of Eastern Europe and publish them in Italy, gradually grew to include a wider array of works including those of Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, and U.S. writers such as Alice Sebold.

Ferrante’s “Troubling Love” arrived at E/O through a friend. That debut novella tells the story of a daughter tracking clues of her mother’s inner life after her corpse has been found floating in the sea north of Naples, naked but for an expensive bra. Compared to Ferrante’s later work, it’s a bit self-conscious. Still, the book is jolting: No one was publishing that kind of work by women in Italy, where they tended to push either frivolous pop or starkly ideological feminist tracts.

Sandra Ferri was awed when she first read the manuscript. “Immediately I thought she is a genius because it is very difficult, very violent,” she recalls.

She and Sandro met with the writer — as is typical for a first-time author and publishers — to discuss edits on the manuscript and its upcoming promotion. Judging from a letter that Ferrante wrote after the meeting to Sandra, she apparently had already alerted Sandro that she would do no publicity for the book, and to “eliminate pauses, uncertainties, any possibility of compliance,” she put her vow in writing.

In the letter, included in “La Frantumaglia,” her 2014 collection of essays and letters, Ferrante is remarkably straightforward. She does not beg permission or apologize for her reticence. She does not bargain or threaten to take her book elsewhere if the publishers don’t agree. “If you no longer mean to support me,” she writes, “tell me right away, I’ll understand. It’s not at all necessary for me to publish this book. To explain all the reasons for my decision, is, as you know, hard for me. I will only tell you that it’s a small bet with myself, with my convictions. I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they won’t.”

She goes on to explain that she had always loved anonymous ancient texts, and the secret of the Befana (the Italian — and female — version of Santa Claus) who leaves gifts during dreamtime. Later on, she would say that she did not wish to give her life over entirely to writing: “I wrote my book to free myself from it,” she writes, “not to be its prisoner.”

For a writer desiring anonymity, E/O was the perfect house. Between the Eastern Bloc state criminals, recluses (they have also published novelist Thomas Pynchon) and fugitives (included among their crime-lit authors), the Ferris have enabled several writers to be published incognito. “We like that,” Sandro says. “Because I think that there has to be magic in fiction, in literature. We don’t like — and we don’t believe in — big publishing, in marketing. We really think there should always be a secret. So many times we pick up authors who are…”

Sandra finishes his thought: “A little bit strange — no photo,” she jokes. “They say, ‘I live in a forest. Write to me in a tree in the forest.’ ”

“Troubling Love” won the prestigious Elsa Morante Prize (named after the writer who happens to be Ferrante’s own literary hero), but Ferrante was in no rush to ride that acclaim. She did not attempt to publish another novel for 10 years.

Then, in 2002, E/O put out “Days of Abandonment” in Italy. Ferrante had been writing during her entire decade-long period of silence, but never could find the right voice, until, as she told The Paris Review in a 2015 interview conducted by the Ferris, “Quite naturally, everything settled around an experience of mine that had seemed to me unspeakable — the humiliation of abandonment.”

In the novella, Ferrante creates a horror-movie effect — the potential monster being the protagonist’s own distracted state, which puts her dog and her children in danger as she struggles with normal life in her apartment. Sandra Ferri says that when she read the manuscript, she had to put it down mid-way. “I was so frightened, I called (Elena) and said, ‘Tell me nothing will happen with the children!’ ”

Ferrante’s translator, Ann Goldstein, also had a hard time with the emotional content, primarily because of the threat to the dog. She had recently gone through an experience that echoed. “To read that book more than once, in a row, was sort of overwhelming,” she says. “There were moments when I just had to walk away from it.”

WHAT’S LEFT BEHIND “The Days of Abandonment” became an indie best-seller when it was released here in 2005, the same year it was made into a movie in Italy.

(EUROPA EDITIONS)

(WIKIPEDIA COMMONS)

WHAT’S LEFT BEHIND “The Days of Abandonment” became an indie best-seller when it was released here in 2005, the same year it was made into a movie in Italy.

After “Days of Abandonment” was made into a movie in 2005 it hit the best-seller lists in Italy. When it appeared in the U.S., in 2005, it also became an indie best-seller and a critics’ favorite. “That book got her this really passionate fan base,” says Lorin Stein, editor of The Paris Review, “so when the big books came along there were a lot of people who wanted to talk about her and write about her.”

The following year, in 2006, Ferrante published another slim novella in Italy, “The Lost Daughter,” the book to which she says she feels the greatest attachment, and which heralded motifs of the Neapolitan novels.

***

MICHAEL REYNOLDS of Europa Editions remembers sitting with Sandro Ferri in the Rome office in summer 2011, going over the list of upcoming titles when “My Brilliant Friend” came up. “Sandro downplayed the series because he thought he shouldn’t jinx the books by speaking too highly of them,” Reynolds recalls. “He had already read the first book, at that point, and had an idea what the project would be. ‘There is a new Ferrante,’ he said.

“That’s good,” Reynolds replied. “What’s it like?”

Sandro told him shyly he thought it might be a masterpiece.

The publishers produced an American print run of 17,000 copies of “My Brilliant Friend” in 2012, which sold out in seventh months. Support was beginning to build among a community of writers. Sebold and novelist Jhumpa Lahiri had been fans for years, and Claire Messud and Elizabeth Strout now championed Ferrante as well. In January 2013, James Wood wrote an article on Ferrante in the New Yorker extolling her virtues. The piece helped legitimize people’s interest in the work, including that of reviewers. When the second Neapolitan book came out in the U.S., in September 2013, sales grew.

The third book, “Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay,” arrived in the U.S. in 2014 with a print run of 14,000, and made 27 best-of-year lists. Then the fourth, “The Story of the Lost Child,” went on the best-seller list the same month it came out, in September 2015 — again, with no advertising.

The Neapolitan series is not for everyone. A review in Commentary magazine calls the series “overwrought, forgettable, and ultimately without substance.”

“She’s like your best friend,” says Amazon’s Nelson, who is a devoted fan. “You love her to death and sometimes you just want to tell her to shut up.”

Ferrante’s books contain all these elements that I love,” says bookstore owner Lisa Howorth. “A little sex. Some bad behavior. Everyone is f***ed up in some way. I like that.

Ferrante herself has admitted that she will employ any technique to hold a reader’s interest; to some, that qualifies her work as potboiler material. In fact, Sandro Ferri suggests that the excellence of HBO-style teledramas have primed readers for well-crafted, episodic storytelling. “The various TV series had a role, maybe, even in the writing of Elena,” he says. “When you are talking about the reason for the moment, you have to notice the big successes of the TV series — people want to look at or read big stories that involve lives.” He believes that world literature has critically overlooked that desire.

Lisa Howorth, a novelist and co-owner of Square Books in Oxford, Miss., also sees echoes of television — and even comic books — in Ferrante: everything from Betty and Veronica to “The Little Rascals” and “The Sopranos,” mixed with the exoticism of “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” “It’s all these elements that I love,” Howorth says. “A little sex. Some bad behavior. There are no good characters, and some are better than others. Everyone is f***ed up in some way. I like that. I don’t want to read a book where there’s heroes, and everything is black and white. And it’s an antidote to so much of the dispassionate fiction that comes out today.”

The Neapolitan books combine head and heart, particularly when it comes to politics. In the third book, for example, Ferrante devotes a full page to Lenù’s reading of the feminist text, “Let’s Spit on Hegel,” which changes even the sentence structure of the narration to accommodate the sensation of ideas trickling into Lenù’s emotional veins.

It seems strange how politically focused the novels are, and yet no one speaks very much about the politics. “Not to put too fine a point on it, but it’s like Tolstoy,” Sara Nelson says. “I mean, that book is really about politics but all people remember is that she threw herself in front of a train. For love.”

In fact, Ferrante’s original manuscript contained even more political material. The only significant edit Sandra remembers suggesting was to cut sections from the third book, which deals with Italy’s “Years of Lead” of the late ’60s to early ’80s, a tumultuous period marked by violence at factories, assassinations, and conspiracies.

“When you talk about terrorism, the extreme left, the fascists,” Sandro explains, “it is still very hot in Italy.” Books had failed because they had gone too far into these subjects. “Of course, (Ferrante) is very good so she knew that. There were parts where Sandra said, ‘Maybe this is too political.’ And (Ferrante) can immediately throw away pages.”

Novelist Jonathan Franzen has written about how difficult it can be to combine politics and art successfully. When interviewed, he notes that Ferrante uses the series’ half-century time frame as a “political filter.” The usual forms of conventional politics prove to be “disqualified for their corruption and wrongheadedness,” Franzen notes, while Ferrante renders feminism as an unassailable human right. He’s correct: A reader can’t dispute the existence of sexism, because after ingesting four volumes’ worth of Lenù’s life, it’s as if he has lived it.

That may be the primary reason for the intensity that accompanies American readers’ advocacy for these books. Women hand them along to each other as if sharing a secret political tract. They circulate against the outrage that fired social-media conversations in recent years, from the 11-hour Congressional interrogation of Hillary Clinton to the abduction of schoolgirls in Africa. Reading the Neapolitan series makes a woman angrier because suddenly the daily, more subtle personal humiliations show themselves to be the very ingredients of epic tragedy. Reckonings along the lines of “Why did I put up with that?” seem to abound every time the storyline coincides with a reader’s life experience.

“Too many women are humiliated every day, and not just on a symbolic level,” Ferrante wrote in a December 2015 interview in the UK-based Financial Times. “And, in the real world, too many are punished, even with death, for their insubordination.”

That echoes one of her exchanges with the New York Times in 2014, a political crie de coeur about life for women in general:

Q. What is the best thing that you hope readers could take away from your work?

A. That even if we’re constantly tempted to lower our guard — out of love, or weariness, or sympathy or kindness — we women shouldn’t do it. We can lose from one moment to the next everything that we have achieved.

Q. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

A. No.

Unflinching responses like these, along with the quality of Ferrante’s work, have made her a kind of polestar of integrity. Consider an incident earlier this year when journalist Roberto Saviano — living undercover and with police protection ever since the publication of “Gomorrah,” his exposé on the Camorra crime syndicate — sent up a distress flare to Ferrante. He had nominated his fellow Neapolitan for the 2015 Strega Prize, the most prestigious Italian literary honor, one that would require her to appear publicly. In the form of an open letter in La Repubblica, he begged her to consider accepting:

Dear Elena Ferrante, I write not as someone who knows you personally but as a reader, and I believe this is the kind of acquaintance you prefer. I have never been intrigued to discover who is behind your name, because since I was young I have always had your pages available to me, and that was enough — and still is enough — for me to believe I know you, to know who you are: a person close and familiar.

Saviano went on to acknowledge that though the Strega Prize had lost its sheen due to speculation that it might be rigged (the winners appear to alternate between the two big Italian publishing companies each year), he hoped Ferrante would keep her name in the running in a bid to cleanse the toxic culture. “It would introduce fresh water to the long stagnant well” of Italy’s publishing world, he wrote, adding, “I nominate you because I think your presence will help this award go back to being something vital and genuine, not just an exchange of vows and favors.”

Ferrante responded with an open letter of her own — here were two writers in hiding communicating in plain view. She relinquished any say in whether he put her book forward: “I completely share your opinions about the Strega, which in my view is one of a great many tables in our country whose legs have been devoured by woodworms.… The use of my book will serve only to prop up an old worm-eaten table for another year, as we wait to see whether to restore it or to throw it away.”

She was named a finalist, but did not win.

The significance of someone like Saviano (himself dubbed a “national hero” by Umberto Eco) appealing to Ferrante’s integrity shows that her rectitude has become a kind of superpower.

Books take off when they address a cultural anxiety. “There is something shifting,” says Brookline bookseller Gozashti, “and I have to credit Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard (the Norwegian author of “My Struggle,” the other confessional multi-volume epic of the moment), for shaking up how we think about things, shaking up our expectations of what we want in literature. Raising those expectations. This is a wake-up call for all of these publishers.”

For latest restrictions check www.corbisimages.com

SIZE MATTERS Ferrante draws comparisons to Norwegian novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard, another writer who is confounding the book world’s established order with his multi-volume confessional epics. (BERND VON JUTRCZENKA/© BERND VON JUTRCZENKA/DPA/CORB)

Michael Reynolds believes readers are reacting to the authenticity of the work. In the U.S., manuscripts tend to emanate from creative-writing programs that standardize craft, then move to marketing-minded agents, editors and salespeople, all of whom can either alter the book for commercial reasons or kill it. “At the end of that process is a super-polished product — I mean, (it’s) exceptional — like this glimmering thing out there,” Reynolds says. “And our books, I am quite happy to say, are not that polished. You might see some messiness, you might find the author doing things that otherwise might have been workshopped out, or edited out. The effect is that you feel you are reading an author’s work, not a work that has been created by committee. And that’s really true with Ferrante. It’s a messy book. For better or for worse, you are getting the author.”

***

AND JUST WHO IS that author? Her protectors will argue that asking the very question amounts to missing the point. Readers have the books, they contend, and that should be enough. But that ignores the seductiveness of her combination of traits: To read a book is to let the author rummage your brain. The implication in Ferrante’s reclusiveness is that the writer wants — more than fame, or prestige, or money — to burrow in and rearrange your emotional landscape. It’s the equivalent of the writer saying, “I don’t want those things. I want you.” And any reader would be compelled by that intimacy.

On top of that, the anonymity is shockingly out of synch with current culture. Clearly, it’s the integrity of the choice that keeps people in awe. People post about a dinner they cooked. Had they concocted a masterpiece, could they resist the urge to share?

BAY WATCH Readers hungry to gain insight about the mysterious Italian author make pilgrimages to Naples, where they visit locations named in the book.

BAY WATCH Readers hungry to gain insight about the mysterious Italian author make pilgrimages to Naples, where they visit locations named in the book. (GABRIEL BOUYS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

And let’s face it: The entire Neapolitan epic is built on the compelling mystery of the disappearance of one of the two main characters. Ferrante herself must believe that the compulsion to discover Lila’s whereabouts or at least, learn why she disappeared, is a strong enough hook to suck readers in. Lila erases not only her physical presence, but every electronic trace of her existence in the world. Why would readers not feel equally compelled, by extension, to find out about the author whose work they have come to care so much about?

What we do know about Ferrante, based on her published interviews, is that she began life in Naples but likely lives elsewhere now. She studied classics. She sometimes translates. She wants writing to be just one of four to five life priorities. It’s a full life involving at least one child. She was a bookish youth. She never went through psychoanalysis. She is shy.

This superhero is afraid of heights. She revealed to the European art magazine Frieze that in her headquarters — in an undisclosed location — she placed a Henri Matisse reproduction, a pebble that looks like an owl, “an early 19th-century painted fan folded up in an antique case,” and a red metal bottle-top she found on a street when she was 12.

In the series, she uses a word, smarginatura, a term used by printers to mean bleeding to the margins. The best advice she ever received was, “Live your life and never complain.” The titles on her recent reading list are intellectual fare that includes books of philosophy and history.

Journalists and critics speculate on her possible identity, thinking perhaps she is a figure already famous among literary circles — such as Anita Raja, the translator from Ferrante’s own publishing house, or even Raja’s husband, novelist Dominico Starnone. But critics could equally speculate, based on the passion Ferrante has stirred up in millions of readers around the world: What if she is simply a normal human, one who passes by in a narrow street or exchanges a “good morning” to her fellow unknowns as she hangs her coat, who does her quiet job well and causes no flurry or stir? There is, for some, a paradise of silence to be found in small-ish towns.

The popularity of her books proves that a deep desire for intense, challenging examinations of lifetimes is not just the hobby of the already famous, but a longing that lurks in the hearts of ordinary people. Ferrante might just be one of those yearning millions. If this superhero is saving us from something, it might be from inanity, from compromise, from exiting life without ever delving into what it all meant.

“Her anonymity tells me that she doesn’t welcome questions,” Franzen acknowledges. “But if we happened to meet at some undisclosed location, I might ask her what she imagines happened to the eponymous lost child of the fourth Neapolitan novel.”

Franzen is talking about a particular plot point, but people get lost in all kinds of ways, and even the brilliant Lila herself becomes the lost child. The highly intelligent grade-school student never got to enjoy the promise she exhibited in youth, and ended up broken by Naples.

The series explores how difficult it is to not let life break you, particularly for women. “As a girl — twelve, thirteen years old — I was absolutely certain that a good book had to have a man as its hero, and that depressed me,” Ferrante told The Paris Review . This epic is essentially a testament to the work that Ferrante has done psychologically not to get lost herself, as an artist or a woman.

***

If we happened to meet at some undisclosed location,” Jonathan Franzen says. “I might ask her what she imagines happened to the eponymous lost child of the fourth Neapolitan novel.

FERRANTE FEVER WILL spread. The Neapolitan series is being adapted for Italian TV by the producers of the wildly acclaimed “Best of Youth,” a 2003 Italian mini-series released in the U.S. as a six-hour feature film.

Ferrante and the Ferris put off pitches by U.S. directors and producers, with Ferrante insisting first on an Italian version, that it be shot in Naples, and that the actress playing Lila be Neapolitan to be true to the dialect. Ferrante can veto the director, and she approves the scripts overseen by Francesco Piccolo, a screenwriter and Strega Prize–winner for his novel in 2014.

The books are propagating throughout the world. Yooyeon Noh, who acquired the books for Korea’s Hangilsa Publishing, predicts that the audience there will embrace the books when they come out in the middle of next year. “I’ve always thought Italian people and Korean people share some common character,” she says, citing their family-orientation and passion.

The one territory the Ferris would love to reach is the Arab world. Years ago, they succeeded in sending a few thousand copies of “Days of Abandonment” in translation, but Arab countries have no distribution. Books can only become known at book fairs in each country. You have to go store to store in each city. “If we were a little younger…,” Sandro says, his voice trailing off. “We should ask the Italian government to help, but they don’t do it. And we certainly can’t go to the rich Saudis with this kind of book.”

In the U.S., Ferrante’s book of essays and letters, “La Frantumaglia,” will be available this April. Her children’s book, “The Night Beach,” which she published in Italy in 2007, may come out here in the next few years — but only, Reynolds insists, if they can do it in a way that does not come across as an attempt to capitalize on Ferrante Fever. Even that decision seems radically out of synch with the culture; most publishers with such a lucrative property would probably be churning out Ferrante beer koozies and keychains.

If a new novel is in the works, Sandra Ferri is the one who will extract the manuscripts from Ferrante. When she senses there is a story nearing readiness, she begins to ask Ferrante when she might see some pages. “Friends call me the Hammer,” she jokes.

For now, though, Sandra won’t push her. “Because really it was such a giant work,” she says. “She was so tired when she finished it. Now she is beginning to be better. And also she is working a lot because she said in each country I can give an interview. But then there were five, six, seven countries — now there are over 40.”

Ferrante may have already written her most important opus. “We were making fun two or three years ago with Elena, ‘Maybe you will win the Nobel Prize’ — but for fun,” Sandro says, “Now, it’s not for fun anymore. I mean, not next year, but who knows?”

Hidden in her lair, Ferrante will keep generating her stories until she finds one she respects. You can imagine that, due to the raw honesty of her work, an emotional blood pact will keep her undercover: Those who know her would be motivated to keep silent so as not to be exposed for their past recklessness. Fans would protect her because she has said she will stop writing if she is unveiled. They want her books, and they admire the integrity.

Besides, only a villain would pull the mask off a superhero.

November 25, 2016

The Power Broker

hn Gomes doesn’t break stride as he rushes across the black marble lobby of his West Village apartment building. He waves a strong arm to indicate I am to fall in immediately as he’s in a hurry to his day’s first meeting. Even from 50 feet away, underneath the lobby’s colossal, 24-foot ceilings, Gomes seems taller than his 6-foot-1 frame. With his shaved bald head, he resembles a more fashionable Daddy Warbucks: stylish, but not flashy, in a soft, gray felt jacket with suede elbow patches, bright tie and brown wingtips. It’s 9:30 a.m. and Gomes has an appointment downtown to discuss the details of a new condo development that could ultimately yield $113 million in contracts.

He bounds into the back seat of his black Mercedes S550 sedan, tricked out with custom, chocolate-brown leather interior. His driver, Douglas, pulls into the heavy traffic, and Gomes hits the button to lower the passenger-window privacy shade, then the window, and thrusts his smooth head fully out into the cold damp May air, like a dog. “I’m sorry,” he says, eyes closed, a beatific expression on his Buddha-like face. “I know this looks weird, but I need to cool down.” This is just one of his morning rituals.

Routine helps keep his driven life on track. He wakes naturally before the 6 a.m. alarm, puts in 20 minutes of Transcendental Meditation and one hour with a personal trainer. For breakfast, it’s muesli with almond milk and Keurig coffee in front of “Good Morning America,” while dispersing hundreds of overnight emails to his assistant or the assistant of his assistant, followed by a long hot steam to clear yesterday’s construction dust from his pores.

Gomes, 44, and his business partner Fredrik Eklund, 39, are the top brokers of luxury new residential development for Douglas Elliman, the biggest real-estate firm in New York City. Riding Manhattan’s building boom, the duo sells multi-million dollar condominiums — many of them outrageously appointed penthouse units perched atop brand-new, gleaming towers — to the very rich, the very very rich and the GDP-hoarders.

Like many who walk the crooked pavements of the city, I have long been perplexed by the end game as more and more high-priced residential skyscrapers climb heavenward. We on the streets negotiate the plywood barricades and dodge cranes in high winds, wondering how there could be yet more billionaires to buy these glass mansions. What does life look like at these altitudes?

The scale of this historic level of development suggests a storyline that I did not fully absorb until I spent a day in Gomes’ company. New York is still harboring foreigners fleeing unstable situations in their homelands, but now the emphasis is not on poor immigrants escaping persecution, it is rich investors seeking a stable haven in a turbulent world market. They are looking to park their global fortunes in our backyard.

skeleton

Katherine Clarke/Daily News

DREAM TEAM Gomes and his partner Fredrick Eklund, left, inspect a property in Tribeca in 2015. The pair surpassed their 2014 record sales commissions in 2015 — and each bettered that total in the first quarter of this year.

This city is creating outsize wealth in multiple industries. According to a 2013 report on the future of cities in The Economist, NYC was rated the most competitive city globally based on its ability to attract business, capital and people — in other words, the ingredients of wealth-building. The report forecasted the city to remain in this position until its farthest projection in 2025. To international and domestic buyers, that makes New York real estate an enticing investment. It’s the reason Russian oligarchs park their money here and one of the reasons the Chinese elite buy homes for their children (along with access to our country’s higher-education system). It’s why Saudis, repelled by British tax laws that have made London less desirable, come house-hunting. Indian, Malaysian and Kazakh investors lead the next wave of foreign home-buyers.

And selling New York real estate can now be done remotely: A broker can send a marketing team to Shanghai or Singapore with their glossy pitch books and computer-animated apartment tours and sell a glinting, high-rise dream home before ever breaking ground.

Domestically, the investment bankers who once swallowed up high-end real estate gave way to hedge-funders. Now, tech moguls and canny entrepreneurs take their place. Celebrities and sports stars buy second or third or fourth homes. Wealthy Manhattanites flip houses in search of the most glamourous asset of all: change.

We rise like emperors over the city, the river and New Jersey unrolling beneath us. Gomes cackles gleefully, “This is how this city gets built!”

Between 2014 and 2015, the number of permits for new residential construction in Manhattan rose nearly 77%. Forbes recently reported that most of New York’s top-ten billionaire developers doubled their net worth since the pre-crash market peak in 2007. Fair-lending and -housing laws prevent the real-estate industry from keeping hard demographic data on buyers, but Jonathan Miller of the real-estate appraisal and consulting firm Miller Samuels Inc., estimates that over the past five years, half of all new-development sales were purchased by international buyers. Those demographics vary greatly by neighborhood: In downtown New York, international buyers make up approximately 15% of the new development purchasers; on midtown’s newly minted Billionaires’ Row, the number is inversed to 85%. But that global buyer pool pulls up prices everywhere, particularly across Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn.

From 2004 to 2014, prices rose dramatically in Harlem (102%), Nolita (79%) and Chinatown (75%), according to PropertyShark, a search engine that tracks real estate in NYC. As a result, the Brooklyn and Queens neighborhoods closest to Manhattan became, in some instances, equally unreachable. The average price of homes in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, increased by 269%, climbing from $275 per square foot in 2004 to $1,015 ten years later.

That, of course, carries along with it all the mixed emotions and experiences of gentrification: Long-time low-income residents cash out and retire happily to Florida, while dependable, long-term renters get pushed out so their buildings can get converted to high-priced condos. Sure, now there are fewer hypodermic needles to step over but fewer subway cars with enough room to squeeze into at rush hour; better restaurants supplant classic dives.

Property values have decreased — sometimes by as much as 30% — in an equally large swath of the city, but in sections all farther out from the Manhattan hub: the Bronx, Queens and South Brooklyn. The net result is that more people struggle to afford life in the city.

But in Manhattan, fortunes can be made. Like most brokers in NYC, Eklund and Gomes are independent contractors who work under the umbrella of a real estate agency. When they represent a seller, they earn 3% of every sale, and 6% when they represent both the buyer and the seller. They pay Elliman an undisclosed amount for office space and the use of the company’s 100-member new-development support team. Under this arrangement, Gomes and Eklund accumulated the highest total commissions at Douglas Elliman in 2013. They bettered that amount in 2014, earning the highest commissions in Elliman’s history, and then beat that record in 2015. Separately, Gomes and Eklund each topped their entire 2015 figures in the first quarter of 2016 alone. In April, they sold their most expensive apartment to date, listed at $32.25 million, on one of the upper floors of 432 Park — at 1,396 feet, the tallest residential structure in the Western Hemisphere — to a buyer whose identity they cannot disclose. Gomes tries to wrangle three or four deals of that magnitude per year, but focuses primarily on volume in the $4-to-$7-million range. He has made up to $1 million on a single sale.

432-park

Courtesy Eklund Gomes Team

PENTHOUSE HUSTLERS Gomes and Eklund sold their most expensive apartment ever, in 432 Park, for $32.25 million. The building, at 1,396 feet, is the tallest residential building in the Western Hemisphere.

In the car, as we navigate the dense traffic of an overstocked city, Gomes educates me on the basic tenets of high-stakes real estate. Sellers, he tells me with the intimate exuberance of a life coach, are his business. Buyers are fickle, he says; sellers, you can count on. They always complete a deal. That’s why he mainly represents sellers, whether they’re developers of an entire building or individuals looking to unload their apartments.

Gomes and Eklund like to think of themselves as not merely selling high-priced apartments, but, rather, creating plush sanctuaries — whole towers of them, from plotting the allotment of one- and five-bedroom units to selecting the cabinet finishes. Sometimes they bring the empty land to a developer, but mostly a developer comes to them with a plot or building shell. They offer developers three choices — always three — of architectural, design and marketing teams. They decide whether the penthouse will have two private elevators and the building should include a candle-lit thermal bath. (High-end master bedrooms now typically have two bathrooms.) Then, they wrangle with the legal paperwork.

Today, Gomes will race to six meetings and appointments up and down Manhattan involving condos in six new buildings — 260 units that will eventually add up to more than $1.1 billion dollars in closing contracts. That constitutes less than half of the buildings that the pair have under development and does not include the dozens of resale units or rentals they currently list.

Like the light of a dead star beaming to our present, the work Gomes does today, for the most part, will not be paid for approximately three years. The day’s agenda includes refining sales materials and selling apartments that mostly do not yet exist. Two buildings are simply “good dirt” as real-estate insiders call it: plots of empty land onto which architectural renderings and animated simulations have been projected. Two are renovations — a former parking garage yet to be gutted and a former music school singing with buzzsaws.

at-party

Bravo

AS SEEN ON TV The Eklund Gomes Team receives exposure from Bravo’s reality series “Million Dollar Listing New York,” on which Eklund stars.

Selling unbuilt apartments requires creativity. In 2008, Eklund paid $10,000 out of his own pocket to create a 12-minute pilot of a show he called “Billion Dollar Broker,” starring himself. A Bravo producer liked it, which eventually led to him landing a lead role on the network’s “Million Dollar Listing New York.” Since its debut in 2012, the show averages approximately 1 million viewers per episode, and has been sold in 100 countries. Eklund’s TV star billing (with Gomes occasionally appearing on the sidelines), along with the heavy use of social media, are part of the duo’s winning pitch. They’re the self-described “New Guard of Real Estate.”

Gomes believes in signs. He believes that if you listen well, the universe will tell you what you should be doing. When he was 26 years old, he used to clip inspirational pictures from magazines: Hotel shots from around the world, beautifully appointed great rooms. One individual obsessed him: Ian Schrager.

“He created everything interesting,” Gomes says of Schrager, innovator of the boutique hotel experience. “The Morgans, the Paramount. He had forayed into the European market.”

Gomes was too young to witness Schrager’s Studio 54 days, when he and business partner Steve Rubell held the keys to New York nightlife. Gomes doesn’t mention the fact that Schrager ultimately went to prison for tax evasion, having hidden cash and paperwork in the club’s ceiling. He is more interested in what Schrager created after serving his time: Palladium, the 14th Street club that Gomes frequented as one of DJ Junior Vasquez’s devoted “disciples,” one who would bounce between VIP room and dance floor during the deejay’s legendary 12-hour parties. Then after Palladium, Schrager created the hotels.

“I thought, If I could ever meet Ian Schrager…” Gomes recalls.

In 2004, Michael Shvo, who was then the top broker at Douglas Elliman, discovered Gomes at Balthazar, the celebrity-studded bistro, where he served as maître d’, having worked his way up from waiter. Shvo used to come every Saturday at 4 p.m. and sit near the reception stand. One day Shvo saw Gomes kissing Eve Mendes goodbye.

“You know her?” Shvo asked.

“Yes.”

“You have her number?”

“Yes.”

“I could make you a millionaire,” Shvo promised.

He kept pushing Gomes to leave Balthazar and join his real-estate crew. Gomes had developed an easy rapport with the restaurant’s A-list clientele: He knew what rich people liked to eat and drink and talk about. While at Balthazar, he was putting himself through business school at Baruch College, focusing on entrepreneurship.

Gomes finally took Shvo up on the offer, and by 2006 he had closed two penthouse deals totaling $12 million.

Shaun Osher of CORE, a boutique real-estate agency, noticed his success. “John Gomes, you are going to have a very long career,” Gomes recalls the agent telling him. “And if you come to me I will put you on the right path.” At that time, Gomes had $500,000 in commissions pending at Elliman and the rule was, if you walked away before the deed transfer, you would leave half on the table. He took the risk.

“And that’s when I met Fredrik,” Gomes says. Once again, luck found him at the right time.

When he started working at CORE Gomes noticed that one of the brokers, the Swedish expatriate Eklund — a former novelist and briefly a porn star, as well as the grandson of Bengt Eklund, one of Ingmar Bergman’s regular actors — always had a desk covered by open-house sign-in sheets, phone numbers, business cards, some spilling onto the floor. Every stray paper represented a deal lost, Gomes figured. He approached Eklund and made an offer to take Eklund’s overflow for a percentage of every sale.

They soon found they trusted each other and, in 2010, struck out on their own. “I started getting a new best friend,” Gomes gushes. “I fell in love with him. He is a very, very beautiful soul and an amazing business partner.” Gomes and Eklund not only work together all day — crossing paths at meetings, then separating for showings — but they vacation together. They involve themselves intimately in each other’s families.

Before Gomes’ wedding to fashion designer Raul Melgoza in 2015, Eklund wrote an Instagram post that detailed the intensity of his and Gomes’ relationship: “I always cry when I think of our friendship and love…. You are the most fearless and honest person I’ve ever met. People are afraid of that, you know, because people can see an angel when they see one, it’s like you are the light that shines and erases all shadows. We’ve been business partners for eight years now but soulmates for eight centuries. And before then parted but never separated in the Big Bang…. We’re going to travel the world together, again and again, retire together and die together.”

vacation

Courtesy Eklund Gomes Team

OFFICE THERAPY The pair frequently vacation together. Before Gomes’ 2015 wedding, Eklund, left, sent a mash note to his BFF on Instagram: “We’ve been business partners for eight years now but soulmates for eight centuries.”

Now we hurtle down to Tribeca, the neighborhood where one apartment vista can encompass not only the skyscrapers of the city, but the living spaces of Beyonce and Jay-Z, Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper. Gomes has shown homes to an entire TMZ roster of these sorts, including Justin Timberlake, Kim Kardashian and Kanye West. He’s sold to J-Lo, and sold for Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick. Once, a woman, led by another agent, arrived for a showing, her entire head, face, and big hair mummified by a colorful silk scarf, large black sunglasses propped over the fabric. She toured the luxury apartment without a word. “I assume a big celebrity was under there,” Gomes says. “But I will never know.”

We leave the spacious showroom on the ground floor of 9 White Street with its detailed architectural model complete with penthouse trees, its meticulous renderings, its samples of finishes, and head over to the husk of 11 Beach Street with an amiable West Coast couple who are contemplating buying in the building, summoned by their increasing work in New York.

The construction elevator on the exterior scaffolding jolts and the whining pulleys haul us to the eighth floor of this soon-to-be 27-unit building. We rise like emperors over the city, the views of Hudson Street, and then the river and New Jersey unrolling beneath us. Here, the air is fresher, more brisk. Gomes cackles gleefully, “This is how this city gets built!”

As the elevator creaks open, we find ourselves in a cement-dust fog. The floor-through is an expansive shell of immense iron and concrete supports. The jackhammers and saws cease and we wend through a thick forest of metal studs, past the half-dozen or so construction crew members frozen in place, like extras in a ballet, poised on a crate doing wiring, or setting up a ladder to hang a socket, or holding a drill to the floor of the future master bathroom. They gaze at us listlessly. The only member of the crew who engages is Miguel, the stocky foreman in baggy work clothes who enthusiastically fills in the blank space left by Gomes’ light pitches.

“New York is becoming a tech city. It makes me feel so good that the people I am selling luxury apartments to are entrepreneurs.”

“This is the great room,” Gomes says, of a space that gapes south into the gray fog of the day. He sketches the stunning future with a wave of his arm and points to the floor plan. “You can’t appreciate the view in this weather.” He points out the massive openings in the cement, “But you get 56 Leonard” — designed by the Pritzker Award–winning architects Herzog & de Meuron — “you get the Freedom Tower…”

“Believe me, the view is unbelievable,” Miguel confirms.

“You have the Tribeca Film Festival…”

“There is fashion, restaurants,” Miguel fills in. “They filmed ‘Ghostbusters’ over at this firehouse.”

Gomes has told me he looks at shoulders when he sells. If he can’t get a person to relax in the space, they will never be able to imagine themselves as residents. But it would be hard to relax our jacketed shoulders clenched in the brisk air that blows through the netting over the massive open window holes, with our awkward hard hats, our mincing steps over the wires.

We head down one flight to a five-bedroom unit in exactly the same shell-like state but facing west. Gomes summons us to one side. “I just want to give you a feel,” he says. He then backs to a metal door, which will one day be the private elevator. I get a sense this performance will be good because he has not actively corralled the group together before. We line up on either side of this future hall. And then he strides past like a runway model, arms arching up over his construction helmet and circling level to his shoulders so they stick out in front of him like bayonets. “As you walk in, that floor-to-ceiling hole is your window. That’s your window,” he calls back to us. “That’s your view!” Watching Gomes perform, you get a sense of how seductive this rarified world can become, how distant the struggles of the majority of New Yorkers who, according to StreetEasy, now devote two-thirds of their income to rent. And I, who had been price-shopping milk the day before, suddenly consider this place, which could house a large family, a steal at $8.65 million.

Real estate in Manhattan has gone through whiplash cycles. Inflated by Wall Street bonuses, the market crescendoed in 2007. After the crash in 2008, nothing sold for a while; in 2009, Eklund was the sole broker in the city to move a Soho apartment in the first quarter.

Volatile markets such as these can spell tough times for brokers. “Card houses,” as realtors call them, crumple when real-estate values go south and prospective buyers of units in new developments walk away from deposits and lawyer fees rather than see a purchase through. Gomes has watched such buildings empty one by one, when all of the work put in over the previous three years goes out the door.

Then, as the U.S. economy stabilized and markets around the world remained volatile, Manhattan real estate became a safe harbor to park assets. Gomes says 2012 and 2013 were erratic and irrational. “It was great for sellers,” Gomes says, “but it was not nice. Many buyers got burnt.” The buyer would put down a deposit and pay for the legal paperwork, only to find a new customer would swoop in at the last minute with more cash and get the keys to their dream home.

Cash purchases kept the high-end market sizzling through June 2015, and remains robust. PropertyShark calculated that the number of all-cash purchases of New York apartments has nearly tripled since 2006. The Treasury Department became concerned that Manhattan was turning into a giant laundromat, with real estate becoming a place to stash ill-gotten fortunes.

In early 2016, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network at the Treasury Department announced a crackdown, starting March 1. They would require all cash purchasers of Manhattan real estate selling for $3 million or more to disclose their identity and not hide behind an LLC.

The Geographic Targeting Order (GTO) focused only on Manhattan and Miami-Dade County, and the program can, by law, last only 180 days. “We are seeking to understand the risk that corrupt foreign officials, or transnational criminals, may be using premium U.S. real estate to secretly invest millions in dirty money,” said Jennifer Shasky Calvery, director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), in an agency press release.

hands-on

Susan Watts/Daily News

FULL SERVICE AGENT Gomes’ hands-on approach extends to prepping properties for photo shoots.

According to Raphael De Niro, son of Robert De Niro and another top Elliman broker, the main reason for hiding behind LLCs might be more straightforward. Speaking at Real Deal, a Manhattan real-estate conference, in May, De Niro said that the concern among potential buyers is mostly about not wanting to pay New York City income tax, when these residences are only part-time homes. In 2015, the New York Times reported that owners of 89,000 of the city’s condos and co-ops claim not to live in the city.

As for Gomes, the topic causes a slight cloud to dim his otherwise sunny demeanor. He offers only that people might have all sorts of legitimate reasons for wanting to protect their privacy. He mentions celebrities trying to keep stalkers of all sorts at bay. Other brokers talk about businesspeople looking to find safe shelter from world leaders wanting to feed them polonium. “We are in America, too, and people came here for freedom,” Gomes says enigmatically. “It’s what makes America what it is.”

Perhaps quieted by the GTO, the high-end residential market shows wear. The developer of a 900-foot, 80-story condo tower on the Upper East Side went to bankruptcy court in April. That same month, Philip Johnson’s landmark 550 Madison, slated to be turned into luxury condos, suddenly sold to Saudi conglomerate Olayan Group for a reported $1.4 billion, not as residences, but as future office space. Gomes won’t comment on the specifics because the realtors on that long-awaited jewel of a project happen to be other Elliman employees. But word is the brokers found themselves surrounded by stacks of exquisitely created pitch books, pored-over floor plans, the detritus of marketing strategies for dream residences that gave way to a commercial market reality. Still, the final sale price suggests the overall real-estate market is healthy.

Between 2007 and 2015, 255 apartments sold in the $10- to $20-million range. Currently, there are 200 apartments on the market at that price point. You could view that inventory as a glut or as an expression of builders’ belief in the global supply of rich people. Michael Shvo, Gomes’ former mentor, noted at the Real Deal conference that the price per square foot at the high end has doubled since 2007, suggesting not so much an oversupply, but a higher valuation.

At the moment, Gomes and Eklund appear to have no shortage of potential buyers. “New York is becoming a tech city,” Gomes says. The former entrepreneurship major likes the new breed. “It makes me feel so good that the people I am selling luxury apartments to are entrepreneurs.”

He admits to feeling a little conflicted that he is profiting off a transformation that annoyed him in the mid-’90s, when he was a young waiter living on W. 10th Street in a coveted rent-controlled apartment. When he was part of Junior Vasquez’s entourage, then-mayor Rudy Giuliani launched his “quality of life” campaign. Gomes resented the crackdown on minor offenses, the scouring of New York’s grittier — and more colorful — neighborhoods. He liked his lifestyle just fine then. But now he considers the source of the luxury boom from which he profits: It all goes back to New York cleaning up back then. And now, upper-middle-class families, who once might have moved to Westchester or Ridgewood, N.J., want to be in New York for the culture and diversity, for the lifestyle. And, as Gomes puts it, who is he to resent families for wanting to live where he wanted to live?

Gomes races into a meeting about a new construction at 1 Great Jones Alley with the developer’s team and Elliman marketing members. Eklund arrives slightly late, apologizing, wearing a fashion-forward black cropped jacket with leather trim. He is more serious than the madcap persona he projects on Bravo, and at this meeting the source of Gomes and Eklund’s success comes into focus: They’re good at what they do. They provide straightforward business advice. They suggest improved design corrections. They pay attention to detail, from the best position of the drone that will take photos of views from the future building to the surface of the facade of the building across the way, which they will rehab to improve that view. They are not crass. They don’t curse. Their teams seem to like them, but they don’t try to ingratiate themselves.

Gomes says he has always held himself to such high standards. “I was always good,” he later tells me. “I was the president of my class in business school. I was captain of the track team. I graduated cum laude. I was an altar boy. My mother always said, ‘I want you to be a good boy. I want you to be a good human.’ ”

The participants at these development meetings throughout the day tend toward a young, competent, shiny-haired, white female majority, with a few smart amiable guys thrown in. The most fascinating aspect is that these young people approach the work not just with a sense of duty, but with what comes off as true personal interest. Everyone perches at the edge of the oversized couches or runs through checklists gripped with the kind of engaged energy formerly reserved for political revolutions.

In another meeting, the design team sent by one collaborator looks fresh from a summer-stock production of “Portlandia,” casually hip, a little scruffy. For a while, I can’t figure out their role. They seem to be responsible for the full-page ad designs, but they also happily volunteer to oversee the construction of a faux balcony so buyers can sense what 200 square feet of outdoor space would feel like. They will fix the looped reel playing on the 16-by-9-foot high-definition screen, but they also crafted the 86-page book with the cover that matches the apartment’s teak veneers. You get the feeling that all of their artistic endeavors are not just the way to pay the bills, but the full expression of themselves.

It’s hard to square this dynamic with discussions about luxury real estate. So much talent is invested in burnishing the high-end, I can’t help wondering what could be accomplished if this same energy could be tapped to address the now seemingly intractable low-end problems. The housing shortage requires clear-eyed advocates: The city government usually demands New York developers to include a percentage of affordable housing in their plans, but often those aspirations disappear along the way. The stock of rent-controlled apartments dwindles. Recent reports on troubles with the Section 8 voucher program show that even employees of New York’s social-service agencies have been pushed into homelessness when they can no longer afford their rent. Of course, my imaginary recasting of these talented real-estate bees as the saviors of the masses is more fantastic than their creation of animated tours of unbuilt luxury skyscrapers. Yet, it’s a testament to the group’s competence that the thought that they could solve New York’s enormous housing problems even crosses my mind.

hands-on

Susan Watts/Daily News

PICTURE PERFECT Gomes reviews a shot during a photo shoot for a penthouse unit in Greenwich Village.

The meeting concluded, Gomes rushes off to his next appointment with a potential seller in Chelsea. Traffic is tight, so Gomes decides to jump out and speed walk. We move so fast the city blurs. I no longer see faces. I don’t notice individual landmarks. Moving at this pace, Gomes occasionally clips a passerby lightly with his umbrella and apologizes. A veteran of the city, I can barely perceive where we are. When Gomes later knocks over a Plexiglas container on a sandwich board he goes back to fix it and notes that it’s an example of his philosophy of leaving things better than when you found them. For once, as I wait for him to complete the task, I can focus: The place he has left better is a pole-dancing school.

Gomes does not eat lunch, per se. He used to shovel down salad in the car, but that proved disastrous. Instead, the driver pauses around noon while in transit to another meeting so Gomes can dash to buy his daily health shake to go. Given that his only other sustenance was the muesli in the morning, I am amazed the man sustains body mass.

The team considers the collages of cabinet finishes and neighborhood finds. “Can we throw in a few edgy objects? It looks a bit tame,” someone says. “Maybe a gun?”

Next stop is home base in the Flatiron District. Gomes and Eklund work at back-to-back computers, divided by a standard cubicle partition in the somewhat cramped office. Their assistant sits on one side, the assistant’s assistant on the other. Gomes’ proclivity for clipping magazine images of grand hotels shows up as the decorative element tacked to his partition wall. Gomes sprays the air with a scent called Relief, created by the company that designs in-house gyms for their buildings, and it is yet another reminder that this whole high-end real estate world smells like paradise — roses in a showroom, gardenia in an elevator. It turns out Gomes picks a unique scent for every selling space to register on the strongest of our five senses.

The Eklund Gomes conference room is small enough that chairs must be carefully choreographed to fit. The design team scrolls through the images from the new catalogue for 75 Kenmare, with Andre Kikoski doing the exteriors and Lenny Kravitz’s design company handling the interiors. It is slated to begin construction this fall. Gomes and Eklund want more bleed-through images, fewer rigid grids. They chuckle at the lobby picture and I realize that it’s because the Elliman employee to my right is the doorman, costumed for the part.

To package these buildings correctly, no glitch can go uncorrected. What is that storm in the distance in the renderings? Why are the imagined pedestrians wearing so much clothing? All those wrinkly pants! They lament that the illustration makes the building in one of Manhattan’s hipper, more vibrant neighborhoods appear like a dentist’s office in a deserted New Jersey strip mall. It must be revised.

The team considers the collages of cabinet finishes and neighborhood finds. “Can we throw in a few edgy objects? It looks a bit tame,” someone says. “Maybe a gun?”

At our next meeting in Midtown East, Gomes returns from the bathroom laughing. “When I stepped away and remembered the image of you running down the street to keep up with me, I realized how insane my life is.” It turns out I, who comes from a family of fast walkers, have no reason to be shamed: Gomes still holds his high school’s hurdling record. Who am I to compete where three decades of adolescents failed?

But having tried to keep pace, I come to wonder what life was like a year-and-a-half ago, before Gomes’ meditation habit, when everything transpired at this frantic speed.

“I was having a nervous breakdown,” Gomes says, frankly. He says he realized he was taking short breaths and would have to give a big yawn in between. “It was counterproductive. I wasn’t happy. What led to the stress was my success and I wasn’t going to become the victim of that success.”

“I am part of the team that is literally changing the skyline of New York.” He laughs. “That’s crazy!”

That’s when he and his husband invited Théo Burkhardt into their apartment for a week to teach them TM. “At core of who we are is spirit, is essence,” Gomes says. “The physical body allows us to do what our spirit wants us to do.”

Gomes’ life now includes a private chef when he and his husband host more than two other people, a weekend house in the country. But life wasn’t always so fancy. His father, Benjie, an immigrant from Cape Verde, off the coast of Africa, met Gomes’ mother, Helen, near Boston, while on a part-time gig installing a Hanukkah Star of David over a local nursing home. He looked down and saw the blond, blue-eyed Irish-American teenager walking into work and was smitten. They married and she gave birth to John at 18, and then John’s sister six years later. Helen never stopped pushing herself, earning her Master’s degree in nursing, eventually working with researchers at Harvard on diabetes, and becoming a much-loved professor at Rhode Island College. Benjie worked his whole career as a truck driver.

John’s relationship with his father, who never graduated high school, wasn’t great when he was growing up in Boston. The father could be aggressive in his desire for his son to surpass him. “Now I look back, I am so happy,” Gomes says. “I credit those lessons to what I’ve been able to achieve.”