Solitaire Townsend's Blog, page 2

June 1, 2025

Our Climate Needs Mythology

Humanity has deep and ever-present mythologies of weather. From storm gods and sun spirits, flood myths and harvest rites, sacred rains and wrathful winds. Weather has shaped not only our farming calendars but also our collective imagination. Weather wasn’t just forecasted; it was feared, worshipped, and wooed. Weather was a mythological narrative.

It still is in most agrarian communities, and echoes reverberate whenever an urban child sings ‘the cold never bothered me anyway’.

But the climate itself? Climate has no Zeus or Thor. No Tlaloc or Tāwhirimātea.

Climate, unlike weather, is slow, statistical, and strangely characterless. It unfolds not in dramatic tempests but in drifting scientific baselines, melting margins, and probability curves. It is a mythological scale threat without the accompanying stories, songs, beliefs, rituals, lessons and icons. That lack, perhaps, is why we struggle so much to care.

This is the great paradox of climate change: it is both the most scientifically documented crisis in human history and the most poorly narrated.

We have an abundance of evidence, and a deficit of meaning.

If we are to rise to the challenge of climate change technologically, psychologically and spiritually, we need more than data and deadlines. We need a mythology. A way of feeling this crisis in our bones, of placing it in story, of seeing ourselves not just as culprits or victims, but as protagonists.

Because myths don’t just explain the world. They shape who we believe we are. In the absence of a shared climate mythos, we risk casting ourselves in the wrong roles: the powerless witness, the indifferent bystander, or the cynical realist. We need instead the healer, the magician, the warrior.

As I’ve often said, climate isn’t just a crisis of chemistry, but of culture. And to meet the moment, we must not only communicate better, but also craft a modern mythology fit for planetary survival.

Mythology As Survival Technology

Myth is not a luxury. Or fluff for children and those easily deceived. If we think of mythology merely as a relic of pre-scientific ignorance, then we neglect one of humaniti’s main coping strategies and drivers of action.

It is, as scholar Karen Armstrong writes in her brilliant book A Short History of Myth, myths are "a system that helps us make sense of our place in the world." Myths shape our moral frameworks, our cultural cohesion, and our capacity to endure suffering and uncertainty.

Anthropologists have shown how myths evolved in human societies as tools for transmitting values, encoding knowledge, and psychologically preparing for hardship. Myths are a survival technology, which are desperately needed when facing a survival crisis like climate change.

One of my favourite books, Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, maps the common structure of myth across time and culture. He sets out the steps: the call to adventure, the descent into the unknown, the return with a gift. These archetypes echo across epics from Gilgamesh to Star Wars, and across religious traditions from Buddhism to Christianity. They are, as Carl Jung suggested, rooted in our collective unconscious, the deep structure of human emotional and symbolic life.

In moments of civilizational stress, it is mythology, not raw data, that enables societies to find coherence and hope. It is what binds individual grief into communal meaning.

The Enlightenment Gave Us Facts, But Took Our Fire.

Since the Enlightenment, modernity has increasingly privileged reason over myth. Science became the dominant epistemology of the West, and myth was relegated to fiction, folklore, or faith.

I’ve considered myself a dedicated empiricist since I first discovered critical thinking as a practice. But the evidence has led me to conclude that when it comes to climate change, science has a blind spot. In the age of empiricism, we lost the cultural muscle for making meaning from complexity.

Climate discourse reflects this deficit. Our most urgent public narratives are almost entirely framed by scientific facts, probabilistic models, and economic forecasts. We talk of 1.5°C, of CO₂ parts per million, of gigatonnes, transition pathways, and net-zero targets.

These are vitally important, but they do not sing to the soul.

We are attempting to fight a dragon with spreadsheets.

Climate Change As Mythic Battle

If climate change is a mythic-scale challenge, then mythic frameworks are required to confront it.

As I look around a field I know all too well, I can’t find the coherent collective mythology for this moment.

The unwilling heroes, the villains to name without abstraction, rituals to help us process grief, rage, and love, symbols that transcend language and culture and above all, narratives that tell us who we are, where we are going, and why we must go together.

This cultural vacuum is too often filled by either despair or denial.

Ingenious and traditional cultures, many of whom have lived through exploitation and collapse, hold a mythology, a belief, that signposts a solution. It’s been my privilege to sit at the feet of storytellers from the Navajo Nation, be transported by Aboriginal Dreamtime, the Mother of the Sea of Greenland is a lesson that will never leave me, I fear the Amazon Boitatá serpant.

These stories uplift me, scare me, teach me.

And I learn that every story was born from somewhere.

Modern Mythology For Climate

What would a modern climate mythology look like? I don’t know yet. But it could be the greatest story ever told.

I do know it would not be a single narrative or a ‘one ring’ market-researched message. Instead, we need an ecosystem of stories: culturally diverse, emotionally resonant, and spiritually compelling.

We will need archetypes. The Fire Bringer, who carries dangerous but necessary power. The Trickster, who exposes corruption with wit and mischief. The Child of Tomorrow, who embodies hope and future memory.

These archetypes must not be just fantasies. They are ways of emotional identification with roles we might play in the real world.

And we’ll need to frame the science in story. Climate not as scientific emergency, but as a threshold. The crisis is a passage, not an end.

The Story That Can Save Us

Myth is not the opposite of truth, it’s how truth travels across generations.

To give ourselves the best chance, we must resurrect what humans have always turned to in times of peril: story, symbol, and myth.

Even an empiricist can see that.

***

You might enjoy other articles from my archives:

Thankfully, Everything Is A Story

Fighting Monsters When You’re Tired

Creative People Are More Optimistic About Our Future, Apparently

May 11, 2025

Becoming A Very Modern Débutante

My novel, Godstorm, is now ‘official’. Last week, my lovely publishers announced the book, and in book launch terms, this is a big moment! Pre-orders will open soon, cover reveal is on its way, and final publication is January 2026.

I promised to share some updates about my writing and the countdown to publication. So far, it’s been so nerve-wracking.

Right now, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m about to debut at court. In Victorian society, a young lady of good breeding would be ‘presented’ at court as part of her coming out season. ‘Coming out’ (no relation to our modern LGBTQIA+ term) was the social debut, an official nod that a young woman was ready to be considered..for marriage, for society, and for scrutiny.

The same holds for the debut novelist. I, too, am ‘coming out’, as in being announced to the literary world. There is a press release. There are Instagram posts. I even have to reach out to ‘influencers’. I’m about to have my moment at the metaphorical Queen’s court, with perhaps a panel at a festival, or a book launch at a Waterstones.

Both debuts are acts of exposure. As one Victorian etiquette guide cautioned, “To come out too early is to risk one’s reputation; to come out too late is to be overlooked.”

Bear with me. This does have at least some relevance! Godstorm is set within a very ‘alternative’ Victorian era with all these social trappings. And although my protagonist would NEVER attend a ball (unless as a serving girl…or assassin), I can’t kick the analogies.

So, as I navigate this unfamiliar world of fiction, I started seeking advice. Not from modern publishing gurus, but from the grand dames of history. What would they say to someone like me…a writer, newly ‘out,’ and entirely terrified?

Coming Out Is an Announcement, Not a Transformation

In 1870, The Queen: The Lady’s Newspaper described a debutante’s presentation at court as: “She is brought out, not changed. Society is not dazzled by novelty but charmed by readiness.”

This hit me quick hard. I guess I’d imagined that being published would change me. Make me feel like a “real” novelist. But no, this isn’t transformation…it’s revelation. I'm not a different person now that my book is about to go on NetGalley. I’ve just been announced. My work is in the room.

Wear The Dress. Don’t Be The Dress

One débutante advice column warned: “Do not let the gown speak louder than the girl. Elegance lies in restraint.”

For me, that gown is my book: polished, blurbed, copyedited, and dressed for the ball. It’s tempting to hide behind it. To say, ‘Let the book speak; I’ll be over here, crouching behind this potted fern of Goodreads reviews.’

But just like a debutante had to speak, dance, and write thank-you notes…I, too, have to show up. Not just at launch parties, but in interviews, emails, school visits, maybe even on TikTok (be still my Victorian heart).

My book may be the dress, but I still have to wear it.

Comparison Is The Thief Of Composure

In 1885, one poor girl wrote in her diary: “Miss Langtree’s gown was embroidered with real silver thread. Mama says it’s vulgar, but I feel dreadfully plain.”

Reader, I have felt dreadfully plain. I’m in a Discord group with many debuts who seem shinier. Their covers are embossed. Their ‘Big 5’ publishers are very enthusiastic. Their blurbs come from authors I worship. Meanwhile, my launch plans feel like they involve more biscuits than buzz.

But the Victorians knew better. “To envy the admired is to dim one’s own candle,” advised The Habits of a Lady. And in today’s terms: my book is not in competition with someone else’s. We are different gowns, different dances, different stories.

Also: I like biscuits.

Choose Chaperones Wisely

No débutante entered society without a chaperone, a watchful and worldly aunt to steer them away from scandal and into safe conversation.

In publishing, those chaperones are my agent, my publisher, my early readers. They tell me how to position Godstorm, when to pause, and how to make some noise about my book.

My work in sustainability taught me that impact demands community. Turns out that is true of most things in life, including publishing!

You Might Not Be the Belle, But You’re Still At The Ball

One of my favourite quotes is from Lady Louisa Anstruther in 1864, who wrote in a letter to her sister: “I was not much noticed, but I did not fall over the footman, nor say anything too foolish. It was, all in all, a success.”

This might be the most comforting debut advice I’ve found.

My novel may not win the Booker. It may not sell 10,000 copies in week one. Maybe the New York Times won’t notice me. But I will not fall over the footman. I wrote a book. I got an agent. I got published. That’s a dance well done.

After The Ball

The Victorians had another truth I’ve come to love: the season was just the beginning. The point of the debut wasn’t just the ball, it was the life that came after. A future full of choices, chapters, and (if very lucky) real companionship.

That’s what I’m preparing myself for. Perhaps I won’t be the belle of the literary season (even though I’ll do my best to be). But I will be there. And I’m already writing my next book. So, I’ll be back. Not as a debut, but as someone who remembers how to breathe through a corset.

And if any debutantes from 1883 are listening, thank you for the advice. You understood more about this wild publishing ride than I ever expected.

As Lady Harriet Stanhope wrote in 1872, “One must never mistake the party for the purpose.”

As I reveal a few more snippets of Godstorm I think my purpose with become clearer. And I hope you like what you see.

May 4, 2025

What Would Shakespeare Do?

I might be the only person in the world who holds post-graduate degrees in BOTH sustainability development and also Shakespeare studies!

Decades ago, I had the chance to combine the two, while making a short film featuring a young Keira Knightley delivering a passage from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a haunting monologue known among scholars as the weather speech:

“The seasons alter: hoary-headed frosts

Fall in the fresh lap of the crimson rose;

And on old Hiems’ thin and icy crown,

An odorous chaplet of sweet summer buds

Is, as in mockery, set; the spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter, change

Their wonted liveries; and the mazed world,

By their increase, now knows not which is which”

(A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2, Scene 1)

In this speech, the fairy queen Titania laments the chaos unleashed upon the natural world. Her quarrel with Oberon, the fairy king, has thrown the cosmos into disarray. The natural cycles have collapsed: seasons bleed into each other, floods ravage the land, crops rot in the field, and disease spreads. The human world suffers because nature has lost its balance…an ecological warning wrapped in iambic pentameter.

This isn't just poetic fantasy. It's startlingly prescient. Titania’s lines read today like the opening chapter of the latest IPCC report. While she speaks of fairy feuds, the deeper truth Shakespeare captures is that when powerful forces lose harmony with each other and the world, it’s the innocent who suffer. Shakespeare, with a playwright’s intuition and a prophet’s vision, understood something about climate collapse long before we had the words ‘global warming’.

Could there be a more fitting allegory for our times? In my almost 30 years of work in sustainability, I’ve used my Shakespearean background as much as my sustainability knowledge. Perhaps in today’s turbulent times, we might all benefit from Shakespeare’s extraordinary insights into the human condition.

The ‘weather’ speech is a perfect example. Titania’s words encapsulate a central idea we grapple with today: that environmental collapse is often a consequence of human conflict, pride, and neglect. The bard may not have written about carbon footprints or atmospheric chemistry, but he instinctively recognised the interconnectedness of human actions and the natural world. What modern science confirms with data, Shakespeare revealed with drama.

Throughout his work, the Earth is not just a backdrop but a character in its own right: sensitive, reactive, and essential to human fate. In King Lear, the wild storm on the heath mirrors the madness of its ageing monarch and the chaos of his fractured kingdom. In The Tempest, nature is both magical and colonised, a source of wonder and exploitation, just as it is today. Shakespeare’s plays don’t just show nature, they remind us that we are part of it.

As we look for new language to motivate climate action, we might do well to return to Shakespeare.

A Climate Speech Worthy Of A King

One of Shakespeare’s most famous speeches, and one I’ll happily recite if we meet, comes from Henry V. It is a masterclass in leadership, resilience, and courage. Delivered just before the Battle of Agincourt, the Saint Crispin’s Day speech transforms a demoralised, outnumbered army into a band of heroes.

Henry’s troops are plagued by sickness, completely outnumbered and demoralised when he says:

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother…”

(Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3)

This is Shakespeare weaponising words to lift hearts. Henry doesn’t sugarcoat the danger; he offers no guarantees of victory or survival. What he offers is meaning. He reframes fear into honour, desperation into unity and suffering into legacy. He tells his men that this will be the moment they’ll recount for the rest of their lives. That their names will be remembered when others are forgotten:

“And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.”

(Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3)

Now imagine we had a speech like this for the climate crisis, not a grim litany of emissions and tipping points, but a rallying cry for action. One not grounded in guilt or sacrifice, but in legacy and love.

Climate change is the defining challenge of our time. It deserves speeches that stir the soul. Shakespeare knew what it takes to rally beleaguered forces in the face of overwhelming odds, and win.

Shakespeare As Climate Muse

There are so many passages and quotes I turn to for hope, inspiration and insight in these difficult days:

“What’s past is prologue.” (The Tempest, Act 2, Scene 1)

History has led us to this moment, but it does not bind us. The story of our species is still being written.

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” (Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene 2)

The crisis we face is not fate. We caused it, and so we can solve it!

“Wisely and slow; they stumble that run fast.” (Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, Scene 3)

A timely reminder that while urgency is essential, recklessness helps no one. Solutions must be just, inclusive, and enduring.

“One touch of nature makes the whole world kin.” (Troilus and Cressida, Act 3, Scene 3)

In climate, there is no ‘them.’ There is only us, and the planet we share.

Shakespeare knew how to connect with something deeper than logic. He spoke to ambition, to shame, to love, to fear. He showed us who we are and who we could be. And perhaps that’s the most urgent need in climate communication today, both the data and the drama.

And there is one line from Shakespeare I return to almost daily. I quote this to myself before I make a speech, before I walk into a meeting, before I try to use everything I am to inspire change;

“All things be ready, if our minds be so.”

(Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3)

I would love to hear other quotes or passages folks turn to for solace and inspiration, please do share them in comments.

⭐ Please share this post on Linkedin, on other social media and email it to friends who might need a touch of Shakespearen poety today ⭐

April 27, 2025

We Need Climate Love Stories, Not Tragedies

I’m in love.

I adore the smell of earth after rain. I’ve fallen for the rustle of leaves above me and crunch of twigs below my feet. The tip of a wave makes my heart flutter. A fleeting smile, children’s giggles, the person who nodded as I held the door for them – I love them.

Too many seem to hate the world we live in and the people we share it with.

Loving them feels easier.

But falling, hard, for life is like every great love story – it can make us vulnerable.

Because to love is to risk loss. To love is to care, and to care is to hurt when harm comes. When fire burns, injustice hits and the beloved world it harmed – it’s heartbreaking.

But here’s the thing I want to argue today:

Climate action, justice work, purpose, positive action, and sustainability aren’t a tragedy. They are romance. Epic, messy, star-crossed romance. With all the longing, heartbreak, fight, and stubborn hope of the best love stories ever told.

Loving something doesn’t mean feeling happy all the time. Romances aren’t easy.

But thinking of this work as a love story, not a horror show, might just save us.

💚 Why Love Stories Work (Even When They Hurt) 💚

Romeo and Juliet may have died young, but we still swoon for their devotion. Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy spend most of the plot arguing…and yet the chemistry! Scheherazade tells story after story, night after night, to keep herself alive and, by the end, wins not only her freedom but love and respect.

The best love stories aren’t simple. They’re not about getting what you want immediately. They’re about persistence and learning. About refusing to give up on each other, even when things get complicated.

Just like climate and sustainability action.

Because climate change, biodiversity collapse, inequality, injustice — these are not just ‘issues’. They are heartbreaks. These are betrayals of the things we love most. The only reason any of us are in this fight is because we are, unapologetically, in love.

💚 Love Makes You Brave 💚

Think of the greatest declarations of love in literature and myth. Penelope weaving and un-weaving her tapestry for twenty years while Odysseus battles gods and monsters. The Chinese legend of Zhinü and Niulang, lovers separated by the Milky Way, allowed to meet only once a year when magpies build a bridge between them.

Love makes people cross oceans, scale walls, plot rebellions, and wait out impossible odds. It makes people believe that the story isn’t over, that love might just conqure all.

Purposeful action asks the same of us.

It asks us to be patient, to be stubborn, to keep showing up. To hold on through the long, dark middle of the tale, that grim chapter when the hero has already failed twice, and the monster still stands. But to believe, fiercely, that the end could still be happy.

In fact, love stories, rather than horror stories, might be the emotional fuel we need to keep going through what climate psychologists call ‘pre-traumatic stress’ and eco-anxiety.

Research from behavioural psychology shows that agency and connectedness reduce despair. We act not because we’re guilted into it, but because we feel bonded to each other, to the world, to the possibility of a future worth fighting for.

💚 The Happy Ending (Might Take A While) 💚

Every romance has that moment where it looks like all is lost. Misunderstandings, betrayals, villains in the way. In Jane Eyre, the wedding is interrupted. In The Princess Bride, Buttercup is married off to a brute. In The Notebook, they’re torn apart for years.

But the hallmark of the great romance? The characters don’t quit. They don’t settle for injustice. They don’t stop loving.

Neither should we.

Because climate solutions exist. Renewable energy is scaling. Regenerative agriculture is growing. Cities are redesigning themselves. Activists are winning courtroom battles. Communities are building resilience.

This isn’t wishful thinking, it’s fact. But facts alone don’t move people.

Love does.

💚 Falling In Love, Again 💚

Romantic plots are driven by two things: longing and connection. That’s exactly what the climate movement can offer, if we tell the story right.

Not as a duty. Not as penance.

But action as a great romance. One where you get to fall in love again and again:

With the taste of local tomatoes warm from the sun.

With the child who looks you in the eye and asks what kind of world they will inherit.

With the flash of a heron’s wings at dawn.

With the activist standing beside you, tired and grinning.

This isn’t about ignoring the hard parts - every good romance has pain! But as the brilliant writer Bell Hooks reminds us, “To love well is the task in all meaningful relationships, not just romantic bonds.” That includes our relationship with the world.

💚 The Story Isn’t Over 💚

Of course, our climate story has its villains and its tragedies. But it also has its love letters. Its meet-cutes and its quiet moments of holding hands in the dark. Its resistance and refusal to give up on each other.

This isn’t about ‘happily ever after’ as a guaranteed ending. It’s about refusing to close the book. About showing up, day after day, page after page, even if the plot twists break your heart.

Because in the best romances, the greatest power is not fear.

It’s love.

⭐ Please share this post on Linkedin, on other social media and email it to friends who might need this reminder that love is the answer ⭐

April 20, 2025

Fighting Monsters When You're Tired

This isn’t going to be a long post, because I’m too tired to write much this week.

But that’s ok. Because I know this story.

These last few weeks have battered everyone. Rising seas and corrupt systems, thick smog and thin empathy. News headlines throb like battle drums. The climate is in crisis, democracy is wobbling, injustice is rampant.

Throw in a family crisis, a health scare, or a job wobble, and suddenly it can become all too much. That’s what happened to me this week.

I’m tired. You’re tired.

You care. You try. But you’re tired.

My sword is becoming heavier in my hand. My muscles ache from raising it again and AGAIN in so many of the same old battles.

Would it really make that much difference if I just…stopped?

Thankfully (or frustratingly), I’ve read, watched and heard so many of our collective stories that I recognise this feeling. In every story I love, there is this dark middle. And the only difference between a tragic and an uplifting ending is whether people give up.

Exhaustion and overwhelm aren’t failure - they are a chapter. And across centuries and continents, fiction has spoken directly to this moment: not the exciting beginning of the fight, but the long middle. The messy, disheartening, relentless part where you’ve already shown up, and the monster still isn’t defeated. Or worse, you begin to realise that there will always be monsters.

So, how do we keep going?

As I’ve often written about before, to be human is to live in a story. Our very essence is narrative, and myth has held, taught and sustained us for literal millennia.

It can offer true comfort, and guidance, in this moment.

The Midpoint Is Always the HardestIn stories from across cultures, the greatest test comes not at the start, but after the hero has already failed once…or twice…or more.

In the Yoruba folktale of Ìjàpá the Tortoise, it’s not his first trick that works to gain his shell. It's his persistence, failing smarter each time (I love these short illustrated versions of his tales if you haven’t discovered him yet).

In Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest surviving texts on earth, the hero’s grief after Enkidu’s death brings him to the brink of giving up. Only then does he begin to change, to listen, to learn what real strength is.

In the beautiful Tale of Genji from Japan, the fragility of life is emphasised through transience. The pain of loss isn’t something to be avoided, but understood and even cherished.

And of course, in my favourite work of climate fiction, The Lord of the Rings, the faithful Sam says:

“It's like in the great stories, Mr. Frodo. The ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger they were. And sometimes you didn't want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the sun shines it will shine out the clearer.”

These stories don’t promise comfort. They offer truth: that the middle of the story is muddy and brutal, and sometimes you will want to stop.

You’re not alone in that. But you’re not done, either.

Exhaustion Is Part of the PathLiterature shows us that the ones who carry on while exhausted are often those who create lasting change.

Psychological research backs this up. Burnout isn’t just individual; it’s systemic. But narrative coping - the ability to frame your struggle as part of a larger story - can reduce emotional fatigue and increase resilience.

This phenomenon is hugely important for folks working to make the world a better place. Seeing yourself and your struggles as part of a large story doesn’t erase your burdens, but can make them bearable. Even meaningful.

Try thinking of those who came before you, and those who will follow after you’re gone, as a shining chain of ‘trying to do the right damn thing even when too tired to do anything’.

You Don’t Have to Fight AloneWhen you're tired, monsters become bigger. That’s how they win; not just by doing harm, but by isolating you. Every dystopia begins with loneliness.

But literature insists on something else: you are never truly alone.

In Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, the key to survival is community, not rugged independence. Lauren, the protagonist, builds a new world while wounded, grieving, exhausted…and with help.

In the Indian novel Sea of Poppies by Amitav Ghosh, characters of vastly different backgrounds form a makeshift family, crossing oceans of pain and empire. The monster of colonial exploitation is not defeated alone, but through collective imagination and care.

And maybe that’s the core lesson: your strength doesn’t always come from inside. Sometimes, it comes from beside.

That’s why I write these posts. It makes me feel less alone, feel part of something, knowing that you are reading. Even in this simple act, we are together. I am connecting with you as my fingers hit the keys in this moment. We are not alone.

Small is BeautifulThe monsters we fight are huge and strong. The systems of harm, the climate feedback loops, and the long shadows of injustice, are all vast.

Feeling tired is a natural response to opening any news app.

But remember this: every great story, every lasting myth, is built around someone who kept going anyway.

So if today all you can do is grieve, then grieve.

If all you can do is plant one seed, then plant it.

If all you can do is rest and whisper, ‘not yet,’ that too is part of the story.

As the Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad wrote:

"I will plant my hands in the garden

And grow, I know, I know, I know..."

Because monsters aren’t just fought with fire. Sometimes, they’re fought with flowers. With friends. With breath. With love.

And always with stories.

⭐ Please share this post on Linkedin, on other social media and email it to friends who might need this reminder that the story isn’t always easy ⭐

April 13, 2025

The Witch and the Carpenter

Instead of writing about stories this week, I thought I’d tell you one. A soft and silly tale for a hard and serious time.

***

The Witch crash lands. Or as she prefers to think of it: a controlled descent.

But when a tall man with grey eyes walks over from a nearby cottage and asks, ‘Did you fall?’ she laughs her reply, ‘Yes’.

The man is the Carpenter. She is not the first witch, wizard, goblin or other broomstick rider to tumble out of the sky into his clearing. Indeed, a few years ago, the Carpenter carefully removed each tree root, jagged rock and thorned bush from the patch between his cottage and the forest. He knows, better than most, how much care a broomstick needs. Not only does magic demand maintenance, but the wood itself must be tended to, oiled and checked for cracks. With diligent attention, a broomstick can last a lifetime.

The Carpenter wasn’t an apprentice anymore. A reed-voiced novice might have lectured the Witch, whose broomstick was splintered and dry. No, he was a master of his craft, who had learnt to provide a clearing for landfall rather than attempting to instruct magic wielders on basic woodcraft. That’s why they came to him.

And this Witch has a wild mop of silver hair and green eyes to laugh at the world. He finds himself smiling rather than frowning at her as his calloused hands run down the broomstick, noting each scratch.

‘This will take me a few days,’ he says, more tentatively than he intended.

The Witch looks around the bright clearing, the dappled darkness at the edge of the trees, and the stone cottage with neat plant pots, gated garden and nothing out of place. A goat bleats.

‘Can you use healing elixirs?’ she asks. It would be a fair exchange. That goat sounded bilious, and her elixirs are potent. The Carpenter nods, eyes wandering between her face and the splintered wood. His fingertips itch, to begin repairing of course.

In his kitchen, the Witch is content to find a large fireplace and cauldron, a solid wooden table, and a stone mortar with pestle. She wanders out to search the wood for herbs while he sands, carves, and oils her broomstick back to health in his workshop. Neither hurry as the sun wanders across the sky. The birds sing about the end of summer, and the goat complains.

As the early autumn light fades, the Witch clears her pots and pestles aside so the Carpenter can lay out a meal of cheese, baked breads, soup from the cauldron and sharp mulberry pickle.

They sit opposite each other to eat, enjoying an unspoken negotiation in the air. The Witch watches the Carpenter move, slow and deliberate as if considering his choices when he picks up a cup or moves a spoon. She studies the large brown hands with blunted nails that carved such elegant designs onto the bowls, cabinets, and candlesticks that light the cottage. She listens as he tells her of his crafting with the Ash, the Rowan, the Oak and the Elder. Then she laughs at tales of his neighbours and the tempestuous goat.

The Carpenter enjoys how the Witch’s eyes widen, breath quickens, and hands dart as she tells him of the daring rescues and dreadful wars she fights. She shifts about in her chair as if dancing, arms thrown wide to describe terrible foes, and laughter ringing even with stories of terror or sorrow.

Leaning over to refill the wine, he thinks her hair smells of adventure.

That night, they both know that rather than the small room he keeps for customers and guests, the Witch will sleep in his large, warm bed. The Carpenter touches her like an intricate carving; he knows how to handle quality. She laughs, and kisses, and teases, and throws back her silver curls, her face warm and shining.

Later, her head nestles in the crook of his arm – just so. At that moment, neither of them wish to be anywhere else. Even though they know they will be.

The few shortening days pass as the Carpenter sands and oils in his workshop. The Witch manages to coax her biliousness elixir down the goat's throat, even though the unpleasant thing tries to bite her hand and stomp her foot. It won’t make the monster any more agreeable, but it will ensure it lives longer.

In the evenings, they sit beside the fire, and it glints in her eyes as she tells him a million things about a thousand different places. And she holds his hand, marvelling at how still she can be when his fingers wrap around hers.

All too soon, the Carpenter has transformed her broomstick from a dusty, peeling branch to a proud staff of rich Rowan, carved with more delicate designs than the Carpenter bothers with for any casual customer. He rubs in the polish for so long that it shines.

Then, they kiss under the tall trees of the wood at the edge of the clearing. Both know this is their last kiss for now, but not forever. He watches her fly off to the world, then walks back to his cottage a little slower than usual.

Of an evening, during the deepening autumn, the Carpenter steps outside with a large mug of tea to stare at the stars, wondering if the Witch will return.

Of an evening, during the early winter, camped at the edge of a battlefield, the Witch wonders if the Carpenter will still be there when she returns.

By the time her war is lost and won, it’s deep midwinter.

She lands lightly in the clearing during a snowstorm and smiles at a yellow light flickering in his cottage window. A powerful desire for warm tea and strong arms wells up, like she’d taken an injury she didn’t remember, and this was the cure.

The Witch returns again in the spring, and the Carpenter takes her to fish in the brook. They end up in the water, laughing and splashing like children. Then she visits in the summer, and they hunt through the trees for herbs to mix in her elixirs. They lay in secret bowers of flowers in the vast forest.

The world turns, as it should.

When she lands one afternoon in the autumn, there are no lights in the Carpenters’ cottage. But the walls still feel warm, and she can hear the dratted goat, so the Witch waits for him on the log beside his door, as the hours pass. What she feels sitting there is every emotion a Witch can feel. Hope, anticipation, embarrassment that perhaps he won’t want her this time. Shame that she, a Witch, is waiting for a man. Worry that perhaps she won’t want him anymore.

As the night creeps across the clearing to cover the cottage, she conjures a little were-light, but it has a colder glow than the yellow flames of his hearth.

Eventually, she hears heavy boot steps crackling through leaves, and the Carpenter trudges into the clearing. Across his shoulders, he carries the corpse of a massive dire wolf, all matted fur and sharp fangs. Her flickering were-light doesn’t reach the Carpenter's eyes, but she almost steps back from him. His calm waters are whipped up into confused waves.

‘It was crazed and killed a child from the village. I had to stop it.’

‘I’m sorry’, she says because she knows the Carpenter does not like to kill, ‘but it was the right thing to do.’

He says nothing, but the waves subside a little.

With her light hovering above them, she helps dig a pit to bury the wolf at the forest's edge. Despite the tiring, dirty work in the dark, the Witch doesn’t ask him why he carried the carcass back here rather than leaving it to rot.

That night, they love more passionately than ever before. Then she holds his head on her chest, stroking his hair as he listens to her heartbeat.

‘I tire of this life, my Witch. The goat is unpleasant, and the winter days are lonely. The wood is just one place in the world’.

‘Of course’, the Witch replies.

The following day, the Carpenter leads (and drags) his goat through the forest to his neighbour's house. Then, he carefully wraps and buries his tools and packs away the warm blankets, carved candlesticks and teacups. The Witch tries to be patient and helpful, but she's excited to show him…everything.

They take off on her broomstick, flying towards the sunrise over the world. The Carpenter doesn’t look back at his cottage.

Together, they tame dragons, and free captives. They argue with kings and lead rebellions. One day, he fights through baying crowds to save her from a pyre on which a tyrant was to burn her. Another day, she hangs over a cliff edge, with him dangling below, only her fingers keeping him from falling.

Her quests take them from the dry sands of the deserts to the thin air of the mountains. They love, cry and occasionally argue. But there is always another village to liberate or an cruel queen to overthrow, so they can’t argue for long.

Then somewhere, at some time, having rescued a family of trolls from an evil princess, they sit together watching the flames of their campfire. The Carpenter softly says, ‘My fireplace will need clearing of leaves before I can light it again.’ And the Witch knows he will soon return to his cottage in the woods.

And she is angry at him, and devastated she will be alone again, and greatly relieved.

After they land in his clearing, the Witch helps clean out the fireplace for a cup of tea together before she returns to her calling. Their goodbyes are fast, and only for now.

The Carpenter collects his unpleasant goat from his neighbours. He digs up his tools and lays each out on his workbench. Seeing the awls and chisels and hammers lined before him fills him with peaceful joy. A feeling he’d forgotten. And he’s glad he went on such wild adventures with the Witch, if only for how perfect his tools are, seen with new eyes.

And the Witch returns in the spring, carrying wildflower seeds collected from all corners of the world to plant in his garden. Then she comes again in the summer, and they run to bathe in the forest brook and splash and kiss in the cool water under the warm sun.

The year turns, and she visits every season, between her crusades.

One night in autumn, her arms cling to his in the warm darkness, but he feels her spirit is walking elsewhere. They gather nuts, roots and leaves, all in silence. He carves, while she wanders alone in the woods. The Carpenter worries, so he makes tea, fills the large copper bath for her to soak, and cooks delicious soups from the nuts, roots and leaves.

He even carves her a tiny wood figure of a witch on a broomstick in intricate detail, with a long cloak fluttering behind. She kisses him with closed eyes, and holds it all evening, turning it around in her hands.

A patient craftsman knows that good timber will reveal its grain.

After dinner, the Witch curls up tight in her chair. The Carpenter sees a scared animal hiding from danger, and a coiled snake preparing to strike.

He slowly plucks the carving from her and wraps her fingers around a cup of tea.

As she stares at the swirling liquid, she says, ‘I've heard tales of a terrible wizard in a great castle on the edge of the world. He is fierce and powerful and has lived for a thousand years. He fuels his magic by stealing the souls of children. I must try to stop him.’

‘Of course,’ the Carpenter answers. He wonders if she will ask him to help her. And he knows he would say yes even though he doesn’t want to re-bury his tools.

‘It’s so far away, and he knows more magic than I do,’ she whispers. Then the Witch sighs as if her decision was taken already. She puts down her tea, unwraps herself to sit in his lap.

‘I will go tomorrow. But tonight, I am here.’

For the rest of the autumn, he looks to the sky, in case she comes hither in need of his help. Through the winter, he leaves a candle burning in the window every night. In the spring, the flower buds he collects for her favourite tea slowly wither. In the summer, he works hard in his shop rather than going to the brook, alone.

His carvings that year are competent, but he does not think they are beautiful.

One crisp morning, just as the leaves start to show a tip of yellowy red, he unlatches the door of his cottage to go and feed the goat.

The Witch lies crumpled on the ground a few steps from his doorway.

Her beautiful broomstick is broken beneath her, his delicate carvings scratched off in places and burnt in others. The Witch herself is nothing but skin and bones, wrapped in a silken dress richer than any he’d seen in his travels. She has a fractured arm and an ermine wrap, a deep leg wound and a necklace of diamonds.

Her breath is as faint as a bird's. The Carpenter carries her into the cottage.

The goat does not get fed that day.

When the Witch finally wakes, her usually bright eyes are cloudy and hooded, ‘He was a terrible man, after all. He used enhancements to hide that he’d murdered the children. But eventually, I destroyed him.’ There was guilt, and pride, and more grief in her voice than he expected.

‘I’m sorry’, he says, because he thinks perhaps the wizard had been harder to defeat than for the reasons she had expected, ‘But it was the right thing to do.’

The Carpenter nurses the Witch, marvelling at how bones heal while wood can’t. He makes her soups and doses her with elixirs she’d left in his cupboard. When she can stand again, he hands her a sturdy crutch he prepared, so she can go outside to look at the sky.

But the Witch doesn’t look upwards. She hobbles with her crutch, carrying a pail of food scraps to the unpleasant goat. Then, she feeds the chickens and makes the tea.

They bury the dress and jewels at the edge of the forest. When she cries out in the night, he holds her until the shaking stops.

As the red-brown autumn succumbs to cold white winter, the Witch wanders into his workshop. He remembers many years ago, standing in the corner of his master’s shop, young hands feeling big and empty. He gives her sandpaper for wood and varnish for the boxes, bookshelves, sledges and staffs.

Before the snows are too deep, they take a long walk to the village. The Witch dresses in a simple smock, which she sewed herself, wrapped with a warm blanket. She is quiet and kind to the village women, and he feels proud, as he should. But he must remember his path when they march back through the dark. For the Witch conjures no were-light. She just holds his hand in the blackness.

Having a Carpenter’s wife is pleasant and easy, but he misses his Witch of the world.

In the deepest winter, a snowstorm starts and doesn’t end. They bring the goat and chickens into the cottage, lest they freeze. And the thick flakes keep falling until they can see only white out of the windows.

At first, they make a game of it in their bright, warm kitchen. But the goat bleats at night, keeping them awake, and the chickens make a terrible smell. They can walk no more than a few steps across their cottage, and for days, the Carpenter can’t lay hands on his tools.

After another night of bleating goat and chicken smell, they try to start a fire for their porridge. But they keep getting in each other's way, and neither can coax the tinder to catch. The goat headbutts the Witch’s leg, and the chickens squawk and the Carpenter moves so very slowly.

‘Enough!’ she says and sparks the fire with magic. Then she laughs, and it sounds like crying.

The Carpenter smiles at her, a sad smile because he no longer has a Carpenter's wife, but a joyful smile because he has a Witch lover.

When the snows melt, he presents her with a gleaming new broomstick built of white Ash. And she kisses him with her lips and her spirit, and she is nowhere else but with him for that moment.

Then she flies off towards the sunrise, singing to the sky.

When he can see her no more, the Carpenter walks back to his cottage, thinking of all the Wizards with Blacksmiths, and Queens with Seamstresses, Professors with Engine-drivers and Explorers with Street cleaners.

Because this is how the world turns. If the Witch had looked down on the Carpenter, as dull and uncouth, then the world would jerk to a stop. Or if the Carpenter had condemned the Witch as wild or dangerous, then the world would turn the wrong way. For we need Witches who will battle for the King of the Eagles and Carpenters who will nurse a robin's broken wing.

Slowly and carefully, the Carpenter makes himself a cup of tea, and looks forward to the spring.

***

April 6, 2025

Thankfully, Everything Is A Story

I was born into a world where everyone seemed to know a story I hadn’t been told.

A glance meant something. A pause meant something else. There were invisible scripts and unsaid rules, exchanged in the space between words, in eyebrows raised and lips bitten. They played roles in a theatre I couldn't quite see, reciting lines I’d never read.

Growing up as a ‘not yet diagnosed’ autistic meant I had to learn the story. Line by line, painfully memorised. Eye contact here, small talk there. Laugh now, nod then. Every social contract was a plot twist I didn’t see coming. But slowly, carefully, I began to read the room.

And in doing so, I began to see the structure beneath the script. That this pretence wasn’t just for social interactions, but society itself.

Because that’s what the world is: a story.

Every social interaction, every institution, every system, every rule, every norm, belief, process, how our economies work, money itself, voting, marriage, work, funerals, capitalism and communism…all just a story.

We are the storytelling species. Not just around campfires, but in every corner of our existence. Yuval Noah Harari famously wrote in Sapiens that ‘the truly unique trait of humanity is our ability to believe in things that exist purely in the imagination’. Every system is a story we’ve agreed to tell together. Shared fictions with real-world consequences.

For most of us, willingly suspending our disbelief in these stories isn’t optional. Neuroscience shows us that human consciousness itself may be nothing more than an elaborate narrative. As cognitive scientist Michael Gazzaniga explains in Who's in Charge?, the brain’s left hemisphere acts as an ‘interpreter’, constructing coherent explanations of our actions after the fact. You reach for a glass of water, and then your brain invents a reason why.

You snap at your kids, and your brain invents a justification from their behaviour.

Even the you you think you are, is a story being told by your brain. An ongoing autobiography, revised moment by moment.

Antonio Damasio, one of the world's leading neurologists, argues that our sense of self arises from the brain weaving together memories, sensations, and perceptions into a cohesive (but invented) narrative. In Self Comes to Mind, he writes, ‘The self is a perpetually recreated neurobiological state’, one that exists to make sense of the world and our place in it.

What feels solid is scaffolded, woven from air.

Social niceties? Stories.

Gender roles? Stories.

Success, failure, beauty, professionalism?

Stories upon stories, written by those who came before us, revised by those with the loudest voices.

And once you see that, you cannot unsee it. And if you're born neurodivergent, you saw the chaos before you could make sense of the stories (or if not make sense, at least learn to mimic). As someone who had to learn the story of being human, not inherit it effortlessly, I’ve developed a strange superpower. I can see that it’s all constructed, not natural or inevitable. I can trace the narrative lines. I can ask: why this story? Who wrote it? Who benefits? And, most importantly, what else could be written?

Because if everything is a story, then we could tell a different one. I’m often bemused, then exasperated, by those who argue are systems are unchangeable, our destiny set, change impossible within a social order that is immoveable.

I want to shout at them IT’S ALL MADE UP! And made-up things can be remade. The story is vulnerable, which is both terrifying and possibly will save us.

We can rewrite the rules of business to value care over consumption. We can change the plotline of leadership from dominance to empathy. We can tell new tales of who belongs, who leads, who thrives. We can burn the scripts that no longer serve us and improvise something astonishing.

Our institutions? They’re stories backed by shared belief. Our economies? Stories dressed up as math. Our cultures? Tapestries of story layered over story, some wise, some broken, many long overdue for revision.

Even the climate crisis is the result of a story, a tale we’ve been telling ourselves about infinite growth on a finite planet. But what if we rewrote it as the story of coming home? Of choosing to care. Of remembering we’re not the protagonists of nature, but part of its cast.

There is radical hope in this idea. Hope not rooted in naivety, but in authorship.

If everything is a story, then we are not passive readers. We are the co-authors of what comes next. We can tear out the tired pages of extraction and exclusion. We can ink new lines of solidarity, regeneration, and belonging.

Neuroscientist Anil Seth, in his work on perception and consciousness, describes our experience of the world as a controlled hallucination…an ever-updated story our brains create based on sensory data and expectation. What we perceive isn’t the world as it is, but the world as our brains predicts it to be.

If our perceptions are that malleable, then our stories about each other, about ourselves, about what’s possible, are even more so.

I’ve spent 50 years carefully tracing the stories, so that I can pretend they are real. Because acting as if this is all real is a pre-requisite of societal acceptance. Even if that often felt ridiculous, willingly conforming to a set of habits that aren’t habitual and norms that aren’t normal.

That was a necessary mistake, but one I’m starting to correct. Because each page we turn on our story is less adventure and more tragedy.

In moments like this, the neurodiverse are called. Those who can see the constructs must lead in dismantling them.

We have lived our lives as outsiders to the story. We are seer of stories. Translators of truths. We witness the architecture of the unseen.

And we are needed. Because the old myths are collapsing. The world is aching for new narratives. Ones with room for nuance, neurodiversity, and necessary change.

Let’s write them together.

Because everything is just a story.

And that means we can make it a beautiful one.

⭐ Please share this post on Linkedin, on other social media and email it to friends who might need this advice on becoming a powerful storyteller ⭐

March 30, 2025

What's Your Superhero Origin Story?

The spider bite, goons killing the kid’s parents, a baby sent into space to escape a dying planet.

The child of a virgin laid down in a manger.

The greatest stories are all about people, and people all start somewhere. Think of any incredible character in a beloved book or movie, and you probably know their ‘back story’. Why? Because of exactly that question - we all want to know ‘why’ someone is who they are, and how they came to do what they do.

And those origin stories might have a more powerful purpose than merely answering our curiosity. Origin stories could be a superpower of their own - one you need to learn to wield.

I shared part of my own origin in the first post for this newsletter - Change The Story, Save The World. About how stories changed the trajectory of my life, and of so many others.

But I’ll be honest, it’s taken me almost a half century to get comfortable talking about the experiences that made me who I am. Instead, when I explained my passion for sustainability, climate action and social good, I used to share a slew of facts, stats and science - as if I was simply a vehicle for the rational rather than a person shaped by my past.

I’m not the only one.

So many of us who are passionate about the world talk about it in abstract terms: parts per million of carbon, biodiversity losses, human rights targets. But behind every act of change, there’s a personal story, a moment when someone woke up and decided to care enough to act. And that moment, I’ve come to believe, matters just as much as the action itself.

Your Origin Is A Welcome MatToo often, the ‘case for change’ sounds more like a moralising sermon, a telling-off, or a patronising lesson in sustainability science.

And then we’re shocked that people don’t warm to our themes, or can’t even summon any interest to listen at all.

But being vulnerable, and sharing the experiences that led us to act, gives people something to empathise with. A reason to care, a foundation to build from, and a narrative to latch onto.

People don’t connect with statistics; they connect with stories.

What I’ve learned from writing, from storytelling, and from the countless creative minds I’ve met along the way, is that personal stories can ripple outward, shaping culture faster than policy or science alone ever could. Culture is where movements begin, with a story shared over coffee, a post that makes someone think, or a moment of vulnerability when we share something true about ourselves.

Research offers fascinating insights into why this power works. When we hear stories, our brains release oxytocin, the chemical which helps us build empathy and trust. According to Dr. Paul J. Zak, a pioneering researcher in neuroeconomics, oxytocin is pumped into the brain when we experience emotional narratives, thereby making us more likely to trust and cooperate with others. In his studies, participants who were shown emotional stories had significantly higher oxytocin levels and then they were even more inclined to engage in charitable and pro-social behavior.

Storytelling is the necessary ‘welcome mat’ to prepare the emotional context to talk about the big issues, warming people up (or at least their hearts).

And the story you can rely on to get right, and to tell with authenticity…is your own.

Once Upon A Time, You Learnt To Tell Your StorySo how do you tell your origin story in a way that sparks action and connection? Here are some things I’ve learned:

Start with a moment of change. Pinpoint a moment or experience that made you sit up and notice something was wrong in the world. It could be awe-inspiring or heart-breaking, or it might be a book you read or just watching animals play as a child. It doesn’t need to be grandiose but it must be real.

Focus on emotion. People remember how you made them feel far more than what you made them think. So use emotional words, explain how you felt in those origin moments - scared, awestruck, overwhemled, angry, shocked, excited.

Use vivid details. Let people see, hear, and feel the story you’re telling. Describe the sights, sounds, smells that defined that moment. If you were 10-years-old watching a beloved tree being felled; tell me if it was chilly winter or sweaty summer, what sound it did the saws make, did you feel tears on your cheek, and make tummy churn?

Show vulnerability. Change doesn’t start from perfection. Be honest about the confusion, doubt, or fear you feel even now. Stories are alwasy about emotional journeys - so share yours.

Tie to action. End your story with what you did about those experiences that shaped you. Show the pathway from waking up to an issue, through to taking action on it.

Ask for a story in return. Ask people about THEIR experience of nature, of unfairness, of postive change. The only thing more impactful than sharing your origin story, is inspiring someone else to share their own and listening to it in rapt attention.

I’ve found that telling my own story not only inspires others but keeps me motivated, too. It reminds me why I care, even on days when the headlines feel heavy.

But, it isn’t easy to be this vulnerable. You need to practice saying it out loud. Share your origin story with a friend or in a trusted group. Notice what makes people lean in, how it feels in your voice, what is hardest to say. Your story is a powerful tool, but it takes practice.

And if you ever doubt whether your story matters, remember this: culture changes one story at a time. One person deciding to care. One conversation sparking another. One brave moment of honesty making someone else say, ‘yes, me too.’

So, what is your superhero origin story? You can share it here in the comments, because we’d all love to hear it.

⭐ Please share this post on Linkedin, on other social media and email it to friends who might need this advice on becoming a powerful storyteller ⭐

March 23, 2025

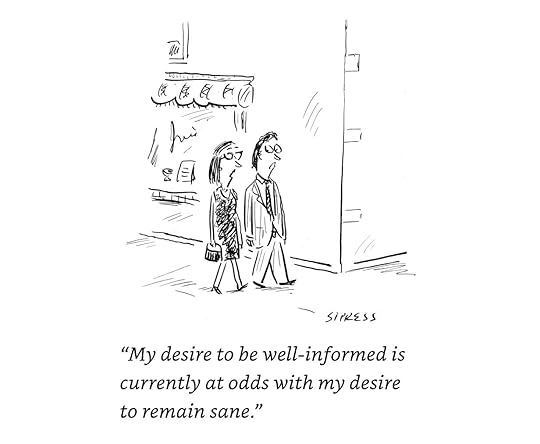

Doomscrolling Won’t Change The World, But Reading Fiction Might

Every morning, before I even rise from my bed, I open the BBC News app on my phone. Laying there, blinking in the too-bright light from the small screen, feels like a solemn responsibility. I am called to bear witness to the neverending outrages, horrors, disasters and foolishness that happened while I slept.

It’s a crappy way to start the day.

My phone could probably tell me how many hours (days?) a month I spend doomscrolling through news reports, LinkedIn posts about that news, deep dives into the background, scathing opinions and data analysis of it all. Catastrophic headlines ping onto my screen by the minute, algorithms funnelling my attention toward the worst-case scenarios. It’s literally my job to ‘stay up to date’ on news about climate change and sustainability. And I scour all that information, opinion and data for scraps of solutions and strategies for action.

Then, almost shamefully, as if partaking in an indulgence that betrays the suffering in all that reality, I read a novel or watch a movie in the evening. I come here on Substack to hurriedly gulp down a short story. Or even, heaven forfend, I daydream my own little fictional vignettes, plotting out my next novel.

The Science Of FictionBut what if those stories offer more than escapism? Perhaps it’s those dramas, romances, fantasies and thrillers that fuel my resilience, emotional dexterity, and, ultimately, hope.

Last week, I wrote that creative people tend to be more optimistic about our future -because imagination is necessary to conjure pathways out of disasters. And the more creative you are, the more solutions you can invent.

And creativity doesn’t (only) mean sitting at a desk pounding out an 80,000-word novel.

Reading a novel or short story, watching a movie or play, or even playing princesses or astronauts with your kids demands imagination - and that’s the raw material with which we build hope.

It may seem counterintuitive. After all, fiction is almost always centred on conflict, jeopardy, or heartbreak. The much-followed structure of the ‘Hero’s Journey’ story arc literally requires a writer to take their character out of everyday reality and fling them into ever more emotionally and/or physically perilous scenarios. Yet, this very aspect is what makes it a vital tool for emotional strength. According to research from the University of Toronto, reading fiction measurably grows our empathy and emotional intelligence. By stepping into the minds and hearts of characters in these overwhelming situations, we practice our own emotional responses to complexity and uncertainty - skills sorely needed in our real-world lives.

One of my favourite genres is science fiction. Perhaps I won’t ever face a galactic war, terraform a far-off planet, or fall in love with an artificial intelligence. But the emotional upheaval of these imagined futures maps onto my real and often justified fears: loss, survival, identity, and the unknown. These narratives offer a safe space to experience terror and triumph without the real-world consequences. In doing so, they offer a rehearsal of resilience. Margaret Atwood has long said that dystopias are not predictions but warnings - and with each warning comes the possibility of change. Through fictional futures, we learn that chaos is survivable, solutions are possible, and endurance is always part of the story.

Empathy Training

Empathy TrainingResearch supports this emotional training ground of fiction. Psychologist Keith Oatley highlights how stories function as a flight simulator for the mind, where we can practice social and emotional strategies in a controlled setting. We absorb the characters’ coping mechanisms and resourcefulness that then imprint on our subconscious. When you find the inner strength to deal with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, that fortitude may have been planted there by a story you read as a teenager.

This revelation echoes findings by neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf, who writes in the wonderful book Reader Come Home that consuming fiction strengthens our ‘cognitive patience’ and raises our capacity for reflection - exactly the mental attributes that all my doomscrolling erodes.

A few weeks ago I explained why Lord of the Rings is my favourite climate fiction. J.R.R. Tolkien also coined one of my most beloved terms: ‘eucatastrophe’, which is a massive turn in fortune from a seemingly unconquerable situation to an unforeseen victory.

Eucatastrophe is the moment when Sauron’s giant hand is revealed to be nothing more than smoke, and Gandalf celebrates the great triumph of the gathered allies, who had all ridden out to war girded for their destruction. Or Shakespeare’s Henry V on the battlefield of Agincourt, having faced French troops outnumbering his own sickly and bedraggled followers, who asks, ‘I tell thee truly, herald, I know not if the day be ours or no’ after his resounding victory.

Fiction trains us to expect these turns, to anticipate that within difficulty lies the possibility of grace. This is not naïve optimism; it’s a disciplined belief that hardship can lead to transformation. Eucatastrophe is possible for us all - if we give everything against the odds.

To Change The Future, We Must Imagine A Better OneThere’s a reason why speculative fiction is often at the forefront of social change. From Octavia Butler’s prescient visions of climate crisis and inequality to Ursula K. Le Guin’s explorations of anarchism and gender, fiction doesn’t just reflect reality - it exponentially expands it. When the real world feels stuck, fiction reminds us that new pathways are possible.

Several years ago, feeling overwhelmed by the seemingly intractable political and industrial causes of climate change, I daydreamed about a world that had it worse than us. Without climate science, this world blames worsening weather on capricious gods, and without renewable energy, the fossil fuel system is literally the only way to keep the lights on. This playful mind game became the basic framework for my upcoming novel GODSTORM. I discovered, to my joy, that dreaming up answers in this fictional world made solutions in our reality suddenly feel much more possible.

So, in an era of relentless fear and crisis, fiction is more than a retreat; it’s an act of mental fortification. It trains us to hold complexity, to face our fears without being consumed by them, and to imagine solutions beyond the current narrative.

So the next time my news feeds feel unbearable, I’ll close my browser and open a book (or write another one). Doomscrolling feeds anxiety. Fiction feeds hope - not by sugar-coating reality, but by helping us confront it with courage and imagination.

If today’s offers you too much reality to handle, turn to fiction for solutions.

[Please share this post on Linkedin and other social media with friends who might need this permission to let fiction fuel their hope]

March 16, 2025

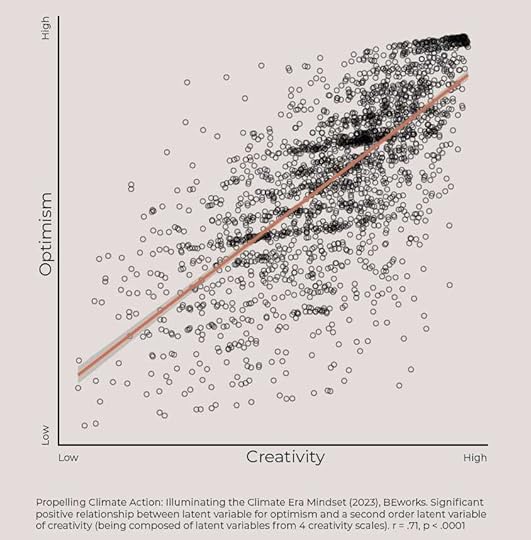

Creative People Are More Optimistic About Our Future, Apparently

Are you optimistic about our future? Then you’re likely a creative person. Score highly on tests for creativity? Then you’re probably a climate optimist.

This research was shared in 2023 and has played on my mind ever since. Based on a global survey of nearly 2,300 people, the behavioural economists at BEworks discovered that creative thinking isn’t just about making art or telling stories, it's a way of seeing and shaping the world that naturally leads to hope and action.

In fact, creative people in the study were more likely to believe in humanity’s ability to tackle the climate crisis, to feel personally motivated, and to put effort into sustainable behaviors. The researchers found a strong link between creative mindsets and climate optimism:

‘A creative mindset will be key to taking on the climate challenge. Fostering a creative mindset can be a pathway to building climate optimism and confidence — and thus engagement in building climate solutions.’

I posted the image above, and the research, very widely when it launched, and it caused quite a stir. Thousands shared and commented on my posts (including Bill Gates), and debate raged.

Those who score highest for creativity also scoring highest for optimism particularly triggered the doomists. They felt rather annoyed by the implication that their pessimism would likely mean they’d score low on creative traits.

I enjoyed the whole thing. But then, after all the 👍 ❤️: the world moved on.

But not me. This BEworks research has played on my mind ever since. As I’ve delved further into my own creativity, I yearned to understand WHY - to understand the causation in the correlation.

I also suspected something very important was lurking in this little survey.

Why are creative people more hopeful?Because creativity is about imagining new possibilities. Inventive and imaginative thought can free us from ‘the way things have always been done’. While many people see climate change as a fixed catastrophe, creative minds see a story still being written and can imagine many different endings.

That’s the experience I’ve most loved about my own journey as a novelist. The permission to invent beyond current rules of reality has exploded my brain. Suddenly, I’ve been unshackled from the rules of the game. I’ve started playing on a different board.

Creative people, especially storytellers, artists, filmmakers, inventors, and writers, have always been the ones who shape how we understand the world, and imagine new ones. As climate scientist Dr. Simon Donner puts it in the BEworks report:

Our imaginations are the key to solving climate change.

Conjuring up different realities is an ability we desperately need in a current reality which could destroy us.

Let’s be clear: optimism doesn’t mean a supine positivity or relaxed assumption that everything will be ok. It also doesn’t mean ignoring the terrible consequences of climate chaos, especially in the most vulnerable communities. In fact, much of the most creative climate art (novels and films especially) is practically dystopian. But I also always find a seed of solutions in these stories. There is always SOMEONE fighting for a better future, looking towards answers, and striving against the dying of the light.

According to the report, nearly half of people globally feel overwhelmed by the climate crisis. 40% feel helpless, and 51% don’t know where to start. But creativity cuts through that fog of fear and inaction, showing us the mindset and mythos to face our grand challenges.

Sparking our own creativity

As a storyteller myself, I don’t want to become a propagandist, even for issues I believe are more important than anything else. Not because I think that creative independence is especially precious, but because propaganda breeds crap storytelling. I do know, however, that climate change is THE most fascinating, shocking, conflict-laden, overwhelming, character-led and important story I will face in my lifetime.

And if it’s true that creative people tend towards optimism, can it be a spark to transform our world in ways unimaginable today?

1. Embrace being a ‘possibility thinker’The BEworks report highlights that creative minds are naturally good at future-oriented thinking, perseverance, and spotting opportunities. These are all essential for climate solutions. If you’re a creative thinker who hasn’t applied your imagination to climate change: we need your magic!

Pro tip: Collaborate with scientists, engineers, and activists to discover real solutions. Then be playful in how you imagine those solutions changing the world. Love stories, mysteries, speculative worlds, thrillers and cosies about climate change will do more than another solemn documentary.

2. Remix the solutionsPeople get stuck thinking that climate action is all about sacrifice and giving up things that matter. But creative people can weave beauty, desire, and joy into climate solutions. Whether it's through film, writing, or creative entrepreneurship, show people the benefits of a different way of living.

Pro tip: Create prose, poetry, art, products, stories and music that make sustainability worth living: more desirable, fun, easy, high-status, amusing, cheaper, beneficial and long-lasting.

3. Make climate intimateStatistics don’t move people; stories do. If half of people are overwhelmed by the scale and height of climate change: cut it down to human size. Explore the lives, loves, challenges and journeys of local heroes, everyday innovators, and exciting activists. Show how climate action connects to the things people already care about - our family, community, and identity.

Pro tip: Focus on specific characters with relatable struggles and victories. Let people see themselves in the story.

Play, invent, and imagine the futureAt a time when so many people are stuck in fear and hopelessness, creative people have an essential role: to imagine pathways out of this mess. As the BEworks report makes clear, creativity is not a luxury in this crisis, it’s a critical survival skill.

So if you’ve ever wondered whether your art, your story, your design, your inventiveness or simply your dreams could make a difference, my answer is yes.

Because if we want a better future, we need to imagine it first.

[Please share this post with creative friends who might take this spark and blow their imagination into a flame of hope]