Ray Hecht's Blog, page 23

March 17, 2016

Beijing Chinglish

Hello readers,

My tour continues in Beijing and beyond to Chengdu, and more on that soon enough. (And more on the security situation in Beijing, on a serious note…)

But first, via Instagram, some Chinglish in Beijing. Including disgusting meat. And a just plain weird candy.

Without further ado:

March 14, 2016

BECAUSE WE (ALMOST) MISSED IT: Best of expat nonfiction 2015

As some readers may recall, I posted, at the end of January, a “best of” list of fiction works by, for, and about expats and other international creatives that came out in 2015.

I know, I know, it should have come out in early December.

And now it’s nearly the end of February, and I still haven’t posted my list of nonfiction books that appeared last year: all of those lovely memoirs, photo guides, guides to expat life, and so on.

But then Leap Day arrived, and I thought to myself: we only get an extra day every four years; why not take the leap and tackle my nonfiction list (so much longer than the fiction one!) once and for all?

Today I present the fruits of my Leap Day labors. May I suggest that you follow my example by springing for one or more of these for your…

View original post 4,767 more words

March 7, 2016

Attending the Bookworm Literary Festival: Beijing and Chengdu

Next week I will be continuing my book tour to all-new heights: I will be traveling to Beijing and Chengdu to participate in the Bookworm Literary Festival!

This is my first time attending, and I’m very excited.

On March 14 (Monday), I will be discussing and reading from my novel South China Morning Blues, at 7:30 p.m., at the iQiyi venue located next to Bookworm. The moderator will be City Weekend’s Adam Robbins. Attendance is 50 RMB.

Then on March 19 (Saturday) I will be traveling to Chengdu. The talk there is at 4:00 p.m. at The Bookworm Chengdu. Tickets are also 50.

Please click on the links for more info.

I haven’t visited Beijing since 2009, and it’s unbelievable that it’s been so long. It will be my first time in Chengdu ever. I’m really looking forward to further traveling in China, and meeting other authors and readers. Most of all, I am grateful – and lucky – for the opportunity to be a part of these events.

Hope to see you there!

March 6, 2016

GZ Poet Aaron Styza

Guangzhou-based poet Aaron Styza organized and spoke at the Yi-Gather event of which I was a part of last month. His poems have been published on Heron Tree, Sediment Literary Arts Journal, and Two Cities Review.

As he is a talented writer in China, I thought it would be nice to interview Sytza and talk about the craft. Little did I know what a fascinating conversation it would be:

(Also, not that I am an expert at poetry but I have occasionally tried to expand my own writing palette…)

What issues or answers does poetry provide or provoke for you?

I’m concerned with the limits of language: how can we measure the effect of what we say? The truth is language cannot adequately express anything. If language were able to express the complexity of thought, there would be no need for poetry. I would say X, and you would understand X. This is not the case. But the inherent inadequacy of language is the very thing that gives poetry its agency: the freedom to investigate a subject obliquely rather than approaching it head-on. Language has a duel effect that causes intense intimacy and terrifying alienation, like birth.

The relationship (or metonymy) between intimacy and alienation haunts a lot of my poems.

How has China shifted your aesthetic focus?

The personas in my poems are often coping with psychological trauma. And like a patient hypnotized into summoning their repressed experiences, poems replay that trauma. Trauma manifests itself as a subjective experience and as a reoccurring, collective experience.

Myths and Fables are a great example of a collective experience: something so ingrained in a culture that it’s inextricable from it. They are our first life lessons and indelible marks on our consciousness. I allude to, and re-appropriate, elements from such sources to “fable-ize” modernity. That is, distance a subject from its context and place in time. And China, with its innumerable stories derived from different characters and dynasties, has opened up a new store for me to work with. This may further reinforce what I said earlier about intimacy and alienation.

What poetic conventions do you avoid or adopt?

I tend to avoid intellectual witticism most, because that techniques imposes the writer’s voice too much and becomes didactic. I admire the poet Robert Frost for his ability to ground his subjects in reality, without intruding his predispositions onto the poem. Even the times when Frost’s voice spikes through the poem—I’m thinking of his piece “West-Running Brook”—he’s laughing at himself, poking fun at his own authority (this is one of many subtleties in Frost’s work which caused him to become one of the most misread and mistaught poets). Yet his representations of the world are some of the closest poetry has come to accessing the humanities. For him, surrendering to the world was a release from it.

Grounding poems in common, understandable images aligns with my own goals (or tastes), rather than getting tied up in heady, theoretical subject matter, or racing to create a new poetic form, which is plaguing a lot of contemporary writing. I’m a sucker for crisp, well-laid images.

As it pertains to artistic inspiration, how does being in Guangzhou, China, contrast with the Mid-West in the United States?

My command for speaking and reading Chinese is not advanced. So when I’m cruising around the street or listening in on people talking, I catch snippets of speech, flashes of images from pictographic characters. In the US, I get it all—I’m right in the middle of the noise. In China, I’m always at a distance. There’s a lesson on silence in here somewhere. What details can we get away with leaving out, and which are essential to the movement?

What poets and poems have inspired you the most?

Two Bobs come to mind: Robert Frost and Robert Bly. Their books are indispensable, inexhaustible resources which I never tire of reciting: Bly’s collection Silence in the Snowy Fields, and the majority of Frost’s work, especially “After Apple-Picking, “Birches”, “Bereft” and “West-Running Brook.”

What brought you to poetry in the first place?

Growing up, I had an affinity for drawing and painting. It was natural for me as well as my siblings. I switched to poetry as an aesthetic choice. I wanted to make larger jumps between ideas, abstractions, and images, without losing structural integrity. Each medium in art has its own particular, idiosyncratic limits, and painting couldn’t facilitate how I wanted to evoke, neither could short stories, but poetry could. There’s also less of a material burden.

Here’s a story I’m fond of: once my brother drove from Wisconsin to New York with his girlfriend to collect some paintings he had left behind when he was studying there. The car was loaded down, but he couldn’t fit one of them—the very painting that compelled the journey in the first place. Too costly to ship, too unwieldy to fit, they set it down near the park, sat at a bench across from it, and waited there until someone walked away with the thing. There’s a photograph of him lighting a cigarette next to the painting as he’s leaving it on a street in New York.

Language is always with you, and it’s light.

http://twocitiesreview.com/2016/02/featured-spring-festival/

Spring Festival

These medical masks aren’t for surgery,

They’re lotus flowers for the mouth.

The air’s killing us slowly.

Let me tell you a tale about the Emperor

Who planted sorrow in his garden

Because he longed for his late wife

And her stories.

And the bit where the shadow puppeteer

Molded her likeness in clay

And danced its shadow on the wall

Behind a candlelit curtain.

Delighted,

The Emperor teemed with song again.

*

The Pearl River takes the heart away,

Coils like a belt to break bone.

We’re swimming backwards through history

And, dear, the water’s just fine.

But I’m so thirsty.

So thirsty, I drink your words.

So hungry, I carve the sky with a knife.

As for loneliness, well, I left out the detail

That the Emperor had other wives.

It’s better to believe shadows become enough,

He might have said,

Getting as lost in form as Narcissus once.

The curtain ripples—blink and she’s there:

No, she’s combing the passages of his hair.

February 29, 2016

Interview with Glen Cornell

Glen Cornell is a local friend, and heads the ChinaSquat language & teaching resource website for expats. He lived in China for a total of five years, starting out as an English teacher in Dalian and finishing up in Shenzhen for three years working for a manufacturing company while simultaneously working as a freelance teacher. He also started up the Shenzhen Book Exchange, an amateur library of sorts for expats to find books in their own language. He recently returned to America and I thought we could catch up via blog…

Hi Glen, how’s the transition back home been? Where are you living now?

I was very ready to move back to the US, but to be completely honest it’s been a bit of a whirlwind the past month, but that’s what I expected. I left China in a bit of a hurry going after a job opportunity that I really couldn’t pass up on. Part of me had hoped things could have gone more smoothly, but normally the transition for expats from China to the U.S. can be a really tough one, with weeks of unemployment, so I’m really glad that I was able to avoid that.

I’m now living in Boston, Massachusetts, working in sales for a marketing software company called HubSpot.

Can you go over about your decision to move to China? Where were you in your life when you made the choice? Why China?

I first decided to come to China about six months after graduating. It was 2010, and the recession still felt like it was in full swing. My “dream job” after college fell through and I was working at a steakhouse living with Mom and Dad. It wasn’t ideal. However, two of my good friends, one from childhood and the other college, were living in China and pushing for me to come check out that side of the world. On my end, I was just happy to get out of my current situation and see a new country. I was also thinking that learning Mandarin would be a good career move, as China and Chinese were becoming more important in the world.

How exactly did you actually get to China? Did you have a job lined up?

So I took a pretty risky move and just came on my own. My friend Eric Lewandowski was currently living in Dalian and he encouraged me to just get myself there with a tourist visa and then I’d find something. In retrospect, that was probably a dumb move, but luckily for me it worked out. I flew in to Chengdu and did some “sightseeing” for a week, and then moved to Dalian to crash on Eric’s couch while looking for work. I found a job my first day in Dalian, and moved into a new place within 5 days.

So clearly you’re not afraid of making big decisions in a hurry.

I guess one could say that.

Without getting into too many specific details, how would you generally summarize your time living in Dalian and working as an English teacher? And how did you get to Shenzhen?

Actually I lived in Xiamen too before I moved to Shenzhen. Haha, it’s a pretty important part to my personal story, but I’ll get to that later.

I started in Dalian working for a private English training center called “Federal IELTS English School”. It was one of those English schools that puts a ton of time into looking like a great school, but very little time actually worried about the content of their classes. I was never trained, and actually ended up passing out in my first class (another story for another day), they very much used me as their “dancing monkey” in numerous situations, but I was willing. I ended up teaching in public a lot. Teaching in malls, in the park, right outside the school… At one point I swear that wanted me to go to one of those indoor playgrounds and just “start talking to random kids and play with them.” A lot of really odd situations. Strangely enough though, I really liked teaching, despite all that BS. I was teaching kids aged from 5 to 18, but mostly middle-schoolers. On the side I decided to open up my own apartment school called “Exact English” which was essentially a chance for me to just simply teach without dealing with all the crap. I was doing small group classes of five students and tutoring one-to-one. It went well, but the biggest hassle was just dealing with parents. I ended up closing things down after about six months in, and ten months into the Dalian experience when I learned that the English school had never properly finished filing my work (Z) visa. It turned out I had been living in China illegally for about three months and had no idea. Since the principal of the school was so well connected with the local government I was given the option to stay with the school, and stay in Dalian, but I opted to just go home. Things had gotten pretty crazy, and I was in over my head, so I went back to the U.S. just in time for Thanksgiving.

You passed out in your first class?

Hahah, okay, so I feinted. It was supposed to be a speaking class of 20 students, but since they hadn’t had a foreign English teacher in years roughly 60 students showed up. It was enough that I didn’t really know what I was doing, but now that there were 3 times the students to the amount of material I had prepared I just kind of lost it and the next thing I knew a student was helping me up. By the way, it was a three-hour class, and this was just the first five minutes. I ended up finishing up the class, but it was definitely not a good start. What I did learn from that, though, is that if you start out at rock bottom you always have room to improve and a real visual for how bad a class can get. I got over a lot of fear from that experience.

What happened after you went back home?

I went back to the U.S. for a bit and lingered, but I knew I wanted to move back to China and work a different job. In February I traveled back with a friend, and started visiting different cities to decide on a place to stay. We visited Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Xiamen, and decided to just stay in Xiamen. I was going to work for the Swiss International Hotel, but once again things fell through in the last second. They changed their policy and could no longer hire foreigners domestically, only their international headquarters could, so despite getting accepted they had to decline within a week. I immediately went to a school called Meten English, that a friend at worked for in the past and told me they were trustworthy. During the interview I basically told them that I wanted to manage or train teachers as soon as I could get the opportunity. I didn’t like the idea of not moving my career forward. To make a long story short, I worked my ass off at Meten. They were much better than Federal IELTS had been, but they had their own problems. Within a couple of months I was declared the center trainer for the foreign teachers, and simply became the liaison between the foreign staff and the Chinese staff. To their surprise I even started doing some teacher training and participated in interviews. I didn’t get paid for any of that, but I actually wanted to make a difference. Because Meten is a chain school (like 40 branches in China now) their headquarters must have heard word of a foreign teacher that was overworking and not asking for much in return. They actually flew into Xiamen and interviewed me for a position in their headquarters in Shenzhen to be a national trainer.

So you took that job?

That’s right, so that’s how I got to Shenzhen. I worked for Meten in Shenzhen for only a year though. The small problems I had with the school only became big problems once I was in the headquarters. It was a great experience though; I got to do a lot of traveling as a trainer.

I recall that you also worked for a manufacturing company; how did you go from English teaching to manufacturing?

So I got to a point where I once again just needed to advance my career, and after almost three years working for English schools I really felt like I could get into something different. I saw a job opportunity posted to be a project manager at an American-owned footwear manufacturing company and jumped at it. In the interview they mentioned liking the fact that I was ambitious and willing to work hard so I got the job despite lack of experience.

Tell me about that job in just a few sentences.

Okay, so basically I was a project manager, product manager, account manager, and marketing manager all in one. We had to wear a lot of hats. I excelled in the account management/marketing side of things, so after about a year working mostly in the factory they shifted me to a position where I could work from home. It was more of a business development role. For the last year I was building out their website, visiting trade shows and making tons of late-night cold calls. To be honest, it was pretty exciting, but I could never get too jazzed about selling insoles.

What about the Shenzhen Exchange?

So this was a pet project of mine, that ended up evolving into several different projects. I basically wanted to start running events, in particular, cross-cultural events that people could learn from. I started with three events, an Idea Exchange, a Book Exchange and a Data Exchange. The Idea Exchange was kind of like a TED talk for China specifically. It kind of took of early on, and I more or less passed it off to a friend that was passionate about developing and growing it. The name changed to IdeaXchange, and it grew to an event that several thousand people went to over time. The Book Exchange was something I worked out throughout the rest of my time in Shenzhen. It was essentially a community library for expats and local Chinese to get access to more English books. I didn’t manage many of these projects very well though, since I was working a full-time job and starting up an English school.

You started an English school?

Really more of a freelance project, but I had a partner and we had big aspirations out the gate to build it out. I was called SpeakEasy English, and we ran it for over a year. In the end, it mostly ended up being an online school and a business training school. We never hired other teachers, but it was a good experience to learn from. Our biggest gig was a five-month long contract with ARUP to train their managers, which only ended when I moved back to the U.S.

What about ChinaSquat ?

ChinaSquat has been through quite an evolution. I technically started the blog in 2010 when I was trying to find a job in the U,S. I started the website as a way to vent some frustration about the job market, and then talk about my move to China. I called it was first called “Life After Graduation” and then I changed the name to “Squatting in China”. The whole “squat” thing was because I knew I’d eventually move back to the U.S. and I thought it sounded catchy.

And now it’s called ChinaSquat?

Yeah, so in my last few months in China up till now I got a bit more serious about the site. I wanted it to be a reference for people like me that want to move abroad to teach in China I didn’t really know what I was doing at the time, but I learned a ton of valuable information. It’s also a bit more than that. I really liked websites like ChinaFile and TeaLeafNation, so I added a section “On China” to go more in-depth about other happenings in China. Now we even have several contributors. Most recently I’ve added a “Stories” section as well, for teachers and expats to share their own experience. I’m hoping that while I’m back in the U.S., this will be my way of staying connected to China in the future.

Sounds like a good plan. I wish you all the best to you in your transition back home, Glen. Good chat!

You too Ray, and congrats on everything you’ve accomplished with the book, website, and blog! I really appreciate the chance to talk!

February 28, 2016

My experience being rounded up by the Chinese police at the big Shenzhen drug raid

[In the early hours of February 21, 2016, there was a major drug raid at a Shenzhen rave party. It has since become international news, reported on by The Guardian and Vice. I was rounded up along with hundreds of other people, and this is my story.]

One of the surprising things I discovered upon moving to China all those years ago was that illegal drugs are remarkably easy to come by. Before arriving, one would assume that wouldn’t be the case in a pseudo-Communist country. Yet, the party scene introduced itself to me almost immediately and I saw that often times drugs among expats were no big deal. Perhaps it’s the chaos that comes with rapid economic expansion, but for whatever reason that’s the way it’s generally been.

To be specific, expat stoners I know seem to usually find a source and easily keep up their stoner lifestyle. It’s only marijuana, and it’s becoming legal in America nowadays anyway, so what’s the big deal?

Besides that, there’s MDMA in the club scene. From what I’ve observed, psychedelics such as LSD are almost unheard of unless one has a very good source – as that kind of psyche-spirituality vibe is not apparent here. Opiates rarer still. I have heard tales of cocaine and ketamine, and newspapers do report that methamphetamine is a growing problem in China.

Based upon my admittedly anecdotal evidence, among foreigners in big cities at least, it’s mostly a bit of MDMA at clubs and the usual marijuana hit if you are into that kind of thing.

Not to mention, like almost everywhere else in the world, the main drug of choice is a certain legal narcotic which is definitely the most destructive of all: alcohol.

Personally, I am not into most that. I think I’ve done the normal amount of experimentation in my life, and politically I am quite against prohibition. But marijuana doesn’t do it for me. It’s not to say that I am morally opposed, the THC chemical reaction simply makes me feel extremely anxious and uncomfortable and I’m not a fan. I don’t particularly like alcohol either, to be honest.

The unfair thing about the world is that the random chemical reactions specific to my brain and genetics more or less keep me clean. It’s not like I’m making any major effort to “just say no.” There is nothing at all fair about functional people who enjoy smoking being punished so harshly in society, while I am not. It’s nothing but luck. And when the police came to drug test me that night, I got to go home, while some of my friends weren’t so lucky…

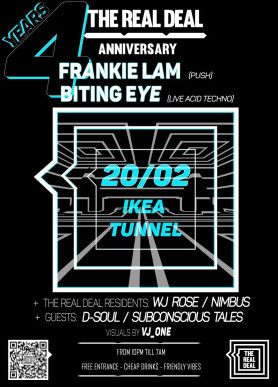

The Real Deal is a group of partygoers in Shenzhen who organize underground outdoor parties with electronic music – raves, if you will. I’ve been going to their parties for years. In fact, the big party that got raided was their 4th year anniversary. They advertise openly, book famous Hong Kong DJs, and have been a fixture on the community for quite some time. It never felt subversive to enjoy their events. I for one appreciate the efforts of the organizers to create a fun place for people to listen to music and find something different to do in Shenzhen. Certainly beats overpriced drinks at pretentious nightclubs.

On the night of February 20th, I decided to go to the tunnel party with my girlfriend. It happened to be near the Ikea, in walking distance from my home in the Baishizhou neighborhood. Several of my friends were there, and I expected we would all enjoy ourselves. Me and my girlfriend arrived at about midnight, met up with some buddies, had some drinks, danced, and so on. I did note that the anniversary party was quite crowded. Still, it seemed legit to me.

Don’t get me wrong. The Real Deal organizers, from my understanding, don’t go farther than make deals with local security guards. Being that it’s outdoors and unlicensed, it’s still pretty much a “rave,” isn’t it? Yet the worst that ever happened in the past is that there’d be noise complaints and some police came to shut down the party. Normal risk, right? Or so one would think.

Without naming names, I did notice LSD and nitrous oxide around. (Are those chemicals even illegal in China?) Pills appeared to be harder to come by, ever since the two unfortunate overdoses back in December most people had been avoiding that sort of thing. No, as usual, the normal culprit was the noticeable smell of marijuana.

I don’t know what made this time so special, why there had to be a crackdown that day. I have no doubt the police knew about these parties for years but never cared. Why now? Was it because of those two overdose deaths that they felt they needed to protect us from ourselves? Was it that the crowds were getting too big and China doesn’t like big, potentially protest-y, crowds? Was it, as currently noticeable from Beijing to Hong Kong, the general atmosphere of authoritarianism which has been growing of late under Xi Jinping…?

In any case, at about 3:45 a.m. a whole lot of shit went down. I remember it clearly because my girlfriend and I had previously discussed that we should leave at 3:30 in order to not to stay out too late. When the time came, she suggested we dance a little more, and I said okay. We tried really hard to not wallow over that decision after the shit went down.

It was totally surreal. I was sitting on a curb catching up with a few pals, and suddenly saw a few police officers run down the hill. I took my girlfriend’s arm and everybody walked away at a brisk pace. Then, the abrupt end to the music caused a weird shift in scenery. The silence came with a sense of panic, and everyone started dashing toward and exit. There was a serious danger of trampling at that point. My first thought was that people were overreacting and it couldn’t be such a big deal, but I soon noticed there was something different about the closure of this party.

We got to an exit and a line of riot police with shields and batons had completely blocked the way. I have never experienced anything like that before. I couldn’t even see behind me because of the crowds, but nobody could move and it must have been blocked on every side. A bilingual, senior looking cop started yelling in English and Mandarin. “Turn off your phones! Sit down! Stay still!” It was a very confusing moment.

The weirdest thing was not knowing what to do next. Although this was an extremely coordinated attack — Shenzhen Daily reported “the Nanshan District Public Security Sub-bureau confirmed the raids had happened and that they had been planned for ‘quite a bit of time.’” — all those hundreds of officers working through the night seemed to be out of their element. We sat around for about an hour. People stood up, and were told to sit down. There wasn’t much room to sit. I saw my friends in various piles, and we tried to keep each other’s spirits up. I had my arm around my girlfriend. On another side, I saw some expat guys getting rowdy and then handcuffed. I saw cops with streams of plastic cable tie handcuffs, yet thankfully they were never used. All in all, in retrospect, it was pretty peaceful. At the time there was just so much speculation; we didn’t know what was going to happen.

Finally, small groups were formed and were told to walk to the nearby parked police buses. We lined up and put our hands on each other’s shoulders like a cheesy conga line. Mine was the second or third group and I was glad to get it over with. I wanted the next step to be done with already.

Once piled into the police bus, we driven around for a while. I had no idea what kind of route they took, but I later learned that it wasn’t even that far; still walking-distance from my home. All different police stations in Nanshan District were working in tandem, and luckily the Taoyuan station was nearby. Along with my girlfriend, two other American friends also joined me in that police station. Along with about fifty people in total. I know that because we were given numbers drawn in sharpies on our hands. I was number 43, and I’ll never forget it.

I had to pee so badly! That was the most painful part of the process. There would be more urine-related activity to go around, and they gave us plenty of water. After things were eventually organized and settled down, the station waiting room was full of chairs and we weren’t allowed to leave and then the real waiting began. The boredom was the absolute worst. No music or anything.

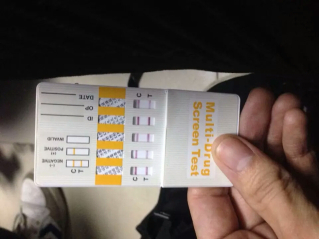

As the sun came up, one-by-one we had to take urine tests. I heard that women had to be watched by a female officer, which is rather humiliating. Men could turn their back while being watched, though I did notice the toilet had a camera positioned above.

Somehow, it occurred to me that it would be appropriate to joke as much as possible. What else could I do but try to laugh it off? I tried to make my friends laugh, and said ganbei! (“cheers”) to the cops as I held my own steaming cup of urine. That got some smiles. I asked if they had Wi-Fi, I declared that I would pee sitting down in solidarity with the women, I sang Taylor Swift songs, I told bad jokes about horses in bars with long faces, and I suggested that I ought to call the police after such treatment. Lastly, when they put the testing device in my cup I asked if it showed I’m pregnant. Get it?

Although I tried to be on everyone’s good side, deep down I felt a lot of animosity for being treated this way. Obviously, the police officers I met are only cogs in a greater machine. Yet they are willing cogs, and cannot approve. Early in the morning they brought some steamed buns for people to eat – struck me as a good cop/bad cop ploy – and I refused to eat any.

Actually, to be fair, our station wasn’t bad compared to what I heard about others. People were made to sit outside on the floor in the cold. Victims were told that the Chinese government has a right to detain anyone innocent for 24-hours without any arrest. Some weren’t allowed to talk. Many weren’t allowed to leave until many hours later than my group.

Of the four of us in my own personal set, only three were to leave that morning. Sadly, one of my friends, of the stoner sort, was sent somewhere else after the drug test. Briefly, I had witnessed some people in a cell in the back; sad scenes of men crying and couples cradling each other. It was very worrying that a friend could be hanging out with us one minute, and then taken somewhere else the next.

After all this grueling time, just before 10:00 a.m., they started letting people out. First a Spanish woman complained until they processed her information and she was allowed to leave. Then a Chinese woman left. I crossed the barricade a few times to complain and plead and just learn what the situation was. Turned out, when I didn’t give them my passport number before (I feigned that I had forgot), they wouldn’t let us leave until everyone gave their numbers so the authorities could check our visa status. Fine. I gave in and gave my number. Then waited another hour or two. How long could it take to look up? I had even crossed the border from Hong Kong the day before. What was the big holdup?

There was one drunk, half-passed out gentleman who couldn’t be bothered to give a real passport number. People were getting angrier and angrier, turning on each other. Interesting to see how easily sleep deprivation can affect people, and on the other side to see how freedom can have the opposite effect. At last, when they had called out numbers and one-by-one we were allowed to leave, we clapped and cheered in joyous relief. “44.” “43.” “42.” Even the cops smiled as us newly freed detainees applauded.

My phone was out of power. My stomach was empty. In minimalist attire, without sunglasses to protect from the morning light, we all went home. That Sunday was a write-off day, like jet-lagged with sleep patterns all askew, and I didn’t get much done. I am getting too old for all-nighters.

In a sense, I was relieved after the experience. A part of me always wondered what would happen if I was got in trouble with the police in China. I feel vindicated now. They didn’t interrogate me or anything, they simply checked my visa status and after a long while let me on my way.

According to a translated press release, the numbers were surprising. 491 people were detained that night. 118 had tested positive for drug use, majority marijuana of course, and 93 held. (It’s not clear why 25 people weren’t held. Connections, corruption?) Of those 93, 50 of them being foreigners. Perhaps they caught like two drug dealers, but most were released after 4 or 5 days. It was called “administrative detention” or “violation.” Not arrest.

“They were after the dealers…” my detained friend later reported back to me. “Everyone else is a pawn to them.”

Those limbo days were rather terrifying. Rumors abounded, and those of us left free all scrambled to figure out what was going to happen to our friends. Moreover, there was the great question of what was happening to the community within China. Simply put, is it worth it to live here anymore?

It has now been confirmed to me that nobody (at least not the vast majority of non-drug dealers) is getting deported. Chinese and foreigners alike, they don’t even have to pay fines. All that fear, and what was the point? The city of Shenzhen undertook this massive operation, apparently all in the legal grey zone haze that is the China system, and just what was the real purpose?

With 80 percent of the detainees drug-free, and only half foreigners: The question remains, what possibly could have been the point of all that?

Whatever the point is, some kind of message has been received. Shenzhen is no longer what it once was. The expat and party scene will get past this, but something has changed. A threatening cloud of authorities now hovers over the community, and somehow China doesn’t seem as welcoming as it used to be.

The party is over.

February 25, 2016

A couple of Chinglishes to tide you over

In these dark times, we must take what we can get to cheer us up :)

From a hike in Meilin, and a Snoopy-ish shirt:

(In other news, I finally saw the Peanuts movie and twasn’t bad…)

February 21, 2016

South China Morning Blues: Excerpt 2

This week I’d like to share another excerpt from my novel South China Morning Blues (last week’s), this time concerning the city of Guangzhou and my favorite character symbolized by the Chinese Zodiac character of 猴… The Monkey!

You can scroll down and read the embedded file below, or download the PDF file via this link:

South China Morning Blues: Monkey

If you’d like to read more, please feel free to order on Amazon or directly from publisher Blacksmith Books

http://www.amazon.com/South-China-Morning-Blues-Hecht/dp/9881376459

http://www.blacksmithbooks.com/books/south-china-morning-blues

February 15, 2016

Excerpt: South China Morning Blues

Now that New Year celebrations are over with, I’d like to share an excerpt of my novel South China Morning Blues published by Blacksmith Books.

You can read the embedded piece below, or download the PDF via this attachment:

South China Morning Blues – Shenzhen: Prologue

It is the very beginning of the story, a prologue to Book I’s setting of Shenzhen. Opening in media res with one character represented by the Chinese Zodiac animal 虎 (Tiger), the story then jumps back and forth with the point-of-view of 兔 (Hare), and finally gets to the introductory character 牛 (Ox). I hope it isn’t too difficult to keep track, hope it’s worth the effort.

These tales represent my attempt at capturing the jagged essence of the modern cityscape experience, as expats and locals try to make sense of this rapidly-changing setting. These people are flawed, don’t always do the right thing, but maybe just maybe they come across as somewhat realistic humans. There are all kinds out there. At least, there are 12 knds out there…

If you’d like to read more, feel free to order on Amazon or directly from the publisher

http://www.amazon.com/South-China-Morning-Blues-Hecht/dp/9881376459

http://www.blacksmithbooks.com/books/south-china-morning-blues

February 7, 2016

Reflections on a Chinese New Year

My own humble attempt at adding to the festivities

The city of Shenzhen is nearly emptied-out. Like a major metropolitan ghost town. Not quite postapocalyptic, but slightly eerie.

All the migrants are back in their hometowns, crowded in record-breakingly awful train stations. And most of my expat friends are posting pictures of paradisesque beaches in Southeast Asia. I’m saving up for a trip later this year.

It is the Year of the Monkey, and cartoon monkeys are everywhere.

Even with Shenzhen at a fraction of its normal population, Lunar New Year’s Eve sounds like a war zone. Bang! Pow! Ka-BOOOOOM!!!! Fireworks — mostly procured illegally — are for sale everywhere. The ancient Chinese traditions.

Many firecracker stands have popped up, selling dangerous flammable items in an unregulated market and it is so much fun.

An odd thing about living in China/Asia is that you get an extra month to reflect upon the new year. There’s the Gregorian calendar to celebrate and I like it. Then there’s several weeks to break resolutions and mull over how your life is progressing. And then you get a second chance to celebrate the new year all over again and embrace the future! The intervening time may be sort of a limbo, but I still like it.

I’d like to wish a particularly happy new year to all you twenty-four and thirty-six year-olds (even though it’s bad luck to have your birthday on your own animal year, right?), as the twelve year cycle begins anew.

新年快乐!

恭喜发财!