Grant Hutchison's Blog, page 54

November 10, 2015

Marooned: Martin Caidin

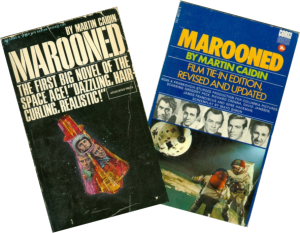

Not a series of novels, but two rather different novels, by the same author and with the same title, written five years apart.

Not a series of novels, but two rather different novels, by the same author and with the same title, written five years apart.

Martin Caidin (first) wrote Marooned in 1964. The novel concerned the fate of an astronaut trapped in orbit by the failure of the retro-pack on his  Mercury spacecraft. I encountered it in the E.P. Dutton first-edition hardback a few years later, as a space-obsessed eleven-year-old prowling the shelves of my local lending library. Everything about it entranced me—the gorgeous cover art, the realism of the technology depicted, the insight into the astronaut training programme, and the fact that there were ten pages of appendices detailing the orbital calculations that had been carried out, by actual spaceflight engineers, to ensure the accuracy of the fictional depiction.

Mercury spacecraft. I encountered it in the E.P. Dutton first-edition hardback a few years later, as a space-obsessed eleven-year-old prowling the shelves of my local lending library. Everything about it entranced me—the gorgeous cover art, the realism of the technology depicted, the insight into the astronaut training programme, and the fact that there were ten pages of appendices detailing the orbital calculations that had been carried out, by actual spaceflight engineers, to ensure the accuracy of the fictional depiction.

The movie rights were picked up by Columbia Pictures, who produced a  film, also entitled Marooned, in 1969. Caidin acted as a technical adviser. The space programme was moving so fast then, at the height of the Space Race, that the novel needed to be completely updated. For the film, the solitary astronaut in his Mercury capsule was replaced by a trio of Apollo astronauts, flying an Apollo Applications mission in earth orbit. The fictional mission drew on much of the planned detail of what would later become the Skylab missions of 1973-74. Caidin made a cameo appearance in the role of a TV reporter.

film, also entitled Marooned, in 1969. Caidin acted as a technical adviser. The space programme was moving so fast then, at the height of the Space Race, that the novel needed to be completely updated. For the film, the solitary astronaut in his Mercury capsule was replaced by a trio of Apollo astronauts, flying an Apollo Applications mission in earth orbit. The fictional mission drew on much of the planned detail of what would later become the Skylab missions of 1973-74. Caidin made a cameo appearance in the role of a TV reporter.

The film received twin accolades: the 1969 Oscar for Best Visual Effects, and the October 1970 Mad magazine movie spoof.

Caidin rewrote his novel to reflect the film plot. This revised edition appeared alongside the film release in 1969, so both the revised novel and the film eerily prefigured the real Apollo 13 crisis of 1970.

Dyna-Soar launch configuration, © Mark Wade

Dyna-Soar launch configuration, © Mark WadeThe novels necessarily differ in the hardware deployed. The 1964 Marooned features rescue missions by the two-seater Gemini spacecraft (which had yet to fly a manned mission at the time of writing), and the Soviet two/three seater Voskhod. The 1969 novel uses a fictional vehicle called the X-RV, which seems to be a hybrid of the lifting bodies then under test, and the cancelled Dyna-Soar design, intended for launch using a Titan IIIC launch vehicle. The Soviet rescue mission is a Soyuz, the Russian workhorse that has been in continuous manned operation since 1967.

The 1964 novel is to some extent a history of the early Space Race, with an almost mission-by-mission account of real-world Mercury and Vostok launches. The 1969 novel, set in the (then) future and written when the Apollo moon landings had only just begun, is necessarily a more speculative affair.

Both books are an extended love letter to the manned space mission. The “Go!” responsory in Mission Control, as the Flight Director polls the Flight Controllers for their go/no go decisions, has always seemed like some sort of quasi-religious ritual, and Caidin is clearly moved by it:

One by one, beautifully, the men at the consoles responded with that exultant, brief cry: “GO.”

Neither book is for the technologically faint-hearted, though. If you can’t stand the occasional paragraph like this, then perhaps you need to seek entertainment elsewhere:

“We’re programming—in the event of trouble in azimuth—launch-vehicle guidance in yaw. This is for the upper stage of the core vehicle only, of course. We do this by varying the launch azimuth of the spacecraft so that the azimuth becomes an optimum angle directed towards the target’s plane. In this way we hope to reduce the out-of-plane distance prior to initiating booster yaw guidance. This cuts down the workload of the booster in correcting yaw discrepancies, and gives us the best chance to slide down into the same plane—or close enough to get that fast rendezvous.”

(I’m glad we’ve got that clarified …)

The film is an obvious precursor to both Alfonso Cuarón‘s 2013 Gravity (peril in low earth orbit), and Ridley Scott’s 2015 The Martian (NASA tries to bring its stranded boy home, with a little help from a foreign space programme). But to a large extent it’s the antithesis of Cuarón‘s undoubtedly spectacular but otherwise deeply idiotic effort. Marooned offers believable characters with believable emotional responses, a plausible problem with plausible solutions, half-decent dialogue and acting, and genuine ramping tension. And it doesn’t need a blaring overwrought score to let you know when you should be worried—in fact it dispenses with music altogether, contenting itself with a little ambient electronic noodling here and there.

I was reminded of how different Marooned and Gravity are when rereading Caidin’s 1969 novel. In the story, the pilot of the rescue mission makes a joke of the fact that he has never flown the rescue vehicle before:

“Nothing to it. I got me a handy-dandy do-it-yourself erector set instruction book. It’s got big pictures …”

It’s as if Caidin were speaking to Cuarón across four decades, but Cuarón wasn’t listening. So poor Sandra Bullock found herself flying a Soyuz capsule using nothing but the sort of instruction manual Caidin had mocked.

That’s all there is to it!

That’s all there is to it!November 9, 2015

Reading: Introduction

I’ve always done a lot of reading. And now there’s a whole lot of reading-for-work that I can stop doing and replace with reading-for-pleasure.

This is a Good Thing, because there’s something of a backlog of books to be read for pleasure. This photo is of about half the stash:

The Oikofuge’s Boon Companion has long had instructions that, in the event of my death, all unread books are to be tipped into the coffin with me. She has recently been grumbling that heavy machinery will need to be hired to move the coffin thereafter.

The Oikofuge’s Boon Companion has long had instructions that, in the event of my death, all unread books are to be tipped into the coffin with me. She has recently been grumbling that heavy machinery will need to be hired to move the coffin thereafter.

To the physical stash, we need to add a couple of hundred additional volumes in the virtual stash: those on the wish-list maintained by the nice people at Amazon.

And then we need to consider the several thousand volumes stored in various nooks and crannies chez Oikofuge. There’s not much point in hanging on to books that you’ve already read unless you intend to read them again. So there’s a lot of work to be done there. In particular, it would be nice to sit down and reread the occasional classic series of novels as a series, in the correct order, rather than encountering them sporadically over many years.

So I’m imagining that this section of the blog will contain reading reports that cover a spectrum between new non-fiction and rather old fiction.

November 4, 2015

Hybrid words

Television? The word is half Greek, half Latin. No good can come of it.

C.P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian

Hybrid formations are words made up of elements derived from different languages. Some people can get very annoyed about this, as did C.P. Scott, above, back in the early days of television. Scott was objecting to the fact that the new word television had been formed from the Greek root tele-, meaning “far off”, attached to the familiar word vision, which is of Latin origin. It had presumably been created by analogy with telegraph and telephone; but both those words are Greek from start to finish, formed from graphe, “writing”, and phone, “voice”.

The trouble with getting annoyed about hybrid words is that they’re everywhere. If you clap an Old English suffix like -ness on to a Latin import like genuine, you have a hybrid; if you add an imported suffix like -able on to an Old English stem like read, you have a hybrid. It gets rather difficult to use English if we disallow all combinations of this sort.

But the ire of the self-styled purists is generally reserved for recently formed words—their newness and unfamiliarity seems somehow to make their hybrid nature more objectionable. H.W. Fowler could be relied upon to express weary contempt for a lot of common English usage, and hybrids were not exempt. In A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926) he made a list of words “of which all readers will condemn some, & some all”. The list included words that are now commonplace, such as amoral, bureaucracy, coastal, colouration, pacifist and speedometer. It also contained a selection that are now pretty much extinct: amusive, backwardation, dandiacal and funniment.

make their hybrid nature more objectionable. H.W. Fowler could be relied upon to express weary contempt for a lot of common English usage, and hybrids were not exempt. In A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926) he made a list of words “of which all readers will condemn some, & some all”. The list included words that are now commonplace, such as amoral, bureaucracy, coastal, colouration, pacifist and speedometer. It also contained a selection that are now pretty much extinct: amusive, backwardation, dandiacal and funniment.

So it seems that there must be other factors that determine whether a word survives and flourishes, or withers and dies. As Robert Burchfield noted in the revised third editon of Modern English Usage: “… a word will settle in if there’s a need for it and will disappear if there is not … amoral, bureaucracy, and the other mixed-blood formations persist, and the language has suffered only invisible dents.”

Hybrid words are sometimes referred to as heteroradicals, from Greek heteros, “different”, and Latin radix, “root”. I’m sure I can’t be the only one who derives an utterly disproportionate amount of satisfaction from the idea that heteroradical is a heteroradical.

Unfortunately, heteroradical is also used to designate a completely different class of words, a subdivision of the homonyms.

Homonyms are words that have the same pronunciation and spelling, but different meanings: for example, the address that you live at, and the address that you make to an audience. Heteroradicals are the subclass of homonyms that also differ in etymology (that is, they’re derived from different roots): for example, the chain mail in a suit of armour and the mail that is delivered to your letter-box. So for the kind of words we’re discussing here, the term hybrid turns out to be more commonly used than heteroradical. This makes me a little sad, but that’s probably just me.

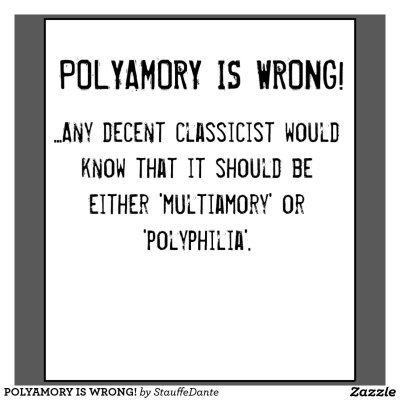

However, I’m cheered by the fact that the abstract little debate about hybrid words seems to have leaked into popular culture, in a post-ironic sort of way. You can now buy the T-shirt:

Click to visit to the seller

Click to visit to the seller(Do I need to tell you that polyamory is the practice of maintain several loving sexual relationships simultaneously, with the full knowledge and consent of all involved? I’m sure I don’t.)

Oikofugic

Oikofugic: having a desire to leave home, an urge to wander or travel

This word was coined in 1904 by the psychologist G. Stanley Hall, in his two-volume opus Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, and Religion. (Given the title, it’s amazing that he managed to hold it down to two volumes.) According to Hall, adolescents were trapped between oikofugic and oikotropic impulses: the desire to leave home on the one hand, and the desire to stay at home on the other. Hall was a great and ponderous coiner of new words. He also described adolescence as being characterized by “a marked decrease of scoliotropism”—that is, a reduced desire to go to school.

One of Kemble’s “Huckleberry Finn” illustrations (1885)

One of Kemble’s “Huckleberry Finn” illustrations (1885)Hall seems to have formed his word from the Greek noun oikos, “a household”, and the Latin verb fugere, “to flee”. So it’s one of those Greek-Latin hybrids that made C.P. Scott write, “No good can come of it.”

Oikos also gives us oikology, a fancy name for home economics, and oikonisus, the desire to start a family. Both these words seem to have no actual life beyond featuring in collections of unusual words.

The Greeks called the whole civilized world the oikumene, as if it were one big residence or household. And when the first great gathering of Christian bishops took place at Nicaea in 325 AD, the resulting Council was called oikumenical, because attendance came from all over the (Christian) world. The English word ecumenical still applies to religious gatherings of this sort.

Fugere gives us fleeing words like fugitive, refuge and refugee. The Latin fugax, “fleeting”, is related, and crops up in medical Latin in the form of amaurosis fugax (“transient darkening”), which is a brief loss of vision in one eye; and proctalgia fugax, a transient, severe pain in the rectum.

The suffix -fuge is problematic. When derived from fugere, it has the sense “fleeing from”—as in centrifugal force, which makes objects appear to fly away from the centre of rotation. But medical Latin treated it as being derived from fugare, “to put to flight”. None of the resulting words is in common use today, but we once had febrifuge, a drug that drives away fever; vermifuge, a drug that causes the expulsion of intestinal worms; and dolorifuge, a drug that drives away pain (what we’d now call an analgesic).

The state of being oikofugic should logically be called oikofugia, though this doesn’t seem to be much attested. And someone suffering from oikofugia should be called an oikofuge.

The difficulty, of course, comes from that ambiguity in the suffix -fuge. So an oikofuge could also be interpreted as something that gets rid of oiks.

November 1, 2015

Words: Introduction

I’ve always loved words: unusual words, technical words, words with interesting etymologies, words that are often misused.

For a while at the end of the last millennium, I wrote little filler items about words for the British Medical Journal, under the slightly self-congratulatory title Words to the Wise. Some have survived to become accessible on the internet, albeit mostly behind a paywall on the BMJ website:

Turning the worm

Byzantine connections

An extended family

Poison arrows

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

Words that count (free full content)

The white album

Muscling in (free full content)

I also used to write occasional Word of the Day items for the site yourDictionary.com, almost all of which have now disappeared. There seems to be a solitary example remaining, oddly preserved on a completely different website. Not even my best one …

So, the set of posts Categorized as “Words” is my chance to get back into that sort of thing. And this time, since I’m setting the rules, I may make occasional diversions to talk about letters, phrases or quotations, too.

I’m planning to include phonetic pronunciations, which will involve a little preliminary fiddling around with web fonts. I apologize in advance if you find yourself peering at some little white boxes or question marks where there should be IPA characters.