Lavinia Collins's Blog, page 13

September 14, 2015

*NEWS* THE FALL OF CAMELOT FREE *NEWS*

THE FALL OF CAMELOT, the third part of the Morgan Trilogy is free for a short time only! Grab it while you can!

THE FALL OF CAMELOT, the third part of the Morgan Trilogy is free for a short time only! Grab it while you can!

Click here to get it free.

September 13, 2015

KING OF AGES Review

King of Ages is a compilation of short stories re-imagining King Arthur across time and space. It features the work of Paola Amaras, Patrick S. Baker, Josh Brown, Dale W. Glaser, Doug Goodman, Joanna Michal Hoyt, Philip Kuan, David W. Landrum, P. Andrew Miller, Mike Morgan, Alex Ness, C.A. Rowland and David Wiley. The stories begin at the end of time, and move through a series of times and locations, reimagining the once and future king and his court in a variety of different times and places from the ancient past through the modern times to the far future.

It’s a wonderful collection, and it really speaks volumes as to the endless creativity and potential for reinvention inherent in the Arthurian Legends. There’s really something for everyone. For me, personally, the standout story was P. Andrew Miller’s ‘If This Grail be Holy’ which reimagines Arthur in the oval office. I thought that Miller managed to capture something of the ambiguity of the painfully intense male-male friendships that so characterise and drive Malory’s fifteenth-century version of the legends, and to translate those meaningfully into a contemporary political scenario. Guinevere appears as a cold political wife a la Claire Underwood, and the story is told with sensitivity and delicacy.

So that was my personal favourite, but the collection really is a wonderful compendium of very different modes; Mike Morgan in ‘Unto his Final Breath’ gives us an apocalyptic Camelot bracing for the end of the world, David W. Landrum imagines a gender-flipped alternative legend, and Josh Brown’s Pirate King Arthur is tremendously good swashbuckly fun. There really is too much creativity and variety to include in one review.

If I were going to be greedy and ask for more (and I am afraid that I am greedy by nature), I would say I would have wanted to see the short story genre harnessed to explore less well-trodden strands of Arthurian legend. In the main, the stories all hugged quite close to the Malorian version of the legends, and this certainly makes sense for longer adaptations since it provides a full narrative sweep from beginning to end, but I hoped that the short story format harnessed to explore less well-trodden versions, such as the early Welsh ones that appear in the Mabinogion – Culwuch and Olwen, Geraint – or perhaps even some of the often unfairly ignored (and much less flattering to Arthur) Scottish Arthurian texts like Golagros and Gawain. Although the stories handled that Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot triangle did so in various ways throughout, I would have liked to have seen something outside that, and for the short story format to be harnessed in order to go off-canon a little bit.

But ultimately this was a wonderful collection that I was more than happy to recommend. It’s a beautiful testament to the way that the Arthurian legends are still alive, still strong and still inspiring people all around the world. It fits so well together, and seeing the Arthurian legend shape-shift through time across the pages is a very entertaining experience. The collection is immense fun, and taken together really is more than the sum of its parts (all of which are good in their own right). And just as one might expect from the Arthurian legend’s endless potential for reproduction reinvention, it’s a collection that sparks the imagination.

I was asked to read this collection to provide a quote for the blurb, and was given a ebook review copy.

September 6, 2015

How Your Bad Reviews Might Be Helping You

It’s easy as an author to react in horror to bad Amazon reviews. Oh no! The inner doubt voice goes, Someone has realised that you are not very good after all, and now they’ve said so in that most sacred of formats, an Amazon book review, the rest of the world will agree with them. It feeds the nasty little voice of that most common of syndromes among fiction writers – imposter syndrome – and makes us fear that one negative voice will put everyone else off.

It’s easy as an author to react in horror to bad Amazon reviews. Oh no! The inner doubt voice goes, Someone has realised that you are not very good after all, and now they’ve said so in that most sacred of formats, an Amazon book review, the rest of the world will agree with them. It feeds the nasty little voice of that most common of syndromes among fiction writers – imposter syndrome – and makes us fear that one negative voice will put everyone else off.

But here’s the thing: OK, I write books, but I buy vastly more books than I write. And never ever ever in my life have I been put off a book that I actually wanted to read by a bad Amazon review. In fact, I have often picked books because of things that negative reviews have said.

The one that comes up most commonly in books written by women, from a female point of view, and set in the past is (in a disparaging manner) that the book is a “bodice ripper”. Aside from the fact that, actually, I love a good bodice ripper, I’m also unsettled by the trend that these tend to be made about historical fiction books that feature a female protagonist and some sex. It seems to be a way of belittling female experience by suggesting that a book is no more than its sex scenes, but often books by male authors that contain a decent amount of sex are viewed differently. So I’m not only positively swayed by the promise of some sex – aren’t we all? ;) – but I’m also suspicious of the reviewer. Romantic love, sex, a combination of the two are not things that make me think less of a book, nor is the fact that something is just a good old middle-of-the-genre romance, and I find reviews that criticise books on that basis deeply suspect.

On that note, I have never ever ever not bought a book because there was a review that said ‘too much sex’. I find that this is rarely ever written about books that are packed with it. I was either interested in the book, or I wasn’t. Sex is a part of life, and I’m not afraid of it, or embarrassed about it. It’s usually obvious from the cover and/or the genre description the level of romping that’s going to be going down (as it were) over the course of the novel.

I’m also put off reviews that go on long, meandering rants, criticising everything about the book, author, cover etc. These are deeply suspect to me too as they don’t seem to be aimed at helping people decide if something is for them, but rather seem aimed at attacking someone or something. They also, perversely, make me intrigued to read the book, and see what it was exactly that got this particular individual (whoever they were) so hot under the collar in the first place. There must have been something engaging about it to merit a rant.

At the end of the day, reviews are what they are; peoples’ opinions. If someone gave a book five stars because it was full of really detailed information on how ships were built in the 1780s, it would still not be the book for me. If someone gave something one star because they thought it was a frivolous romance, I would almost definitely still buy it. It’s hard when, as an author, you are so invested in your own work, but I take comfort in my own readerly habits, and trust that all bad reviews do is guide away people who wouldn’t enjoy my books anyway.

What is other people’s experience with reviews? Do you use them much to choose what you’re going to read?

August 30, 2015

GUEST POST: Author Julie Shackman on “When a Book Doesn’t Do It For You”

I hate having to do this.

It makes me feel incredibly guilty, as I know what a labour of love writing a novel actually is.

But the current novel I’m reading – well, I just can’t get into it.

I’ve tried. Honestly I have. Yet, every time I go to pick it up, I don’t get that frisson of excitement and anticipation.

I really enjoyed this author’s two other novels (which feature the same array of characters) but this one – well, it’s just page after page of dialogue and no description. It’s almost as if the writer is relying on the fact that you have probably read the other two books and don’t need additional details.

Oh but I do!

I’m one of those writers/readers who loves description. From the moodiness of the weather to the knick-knacks a protagonist might hoard in her house, I’m a real sucker for visualising when I’m reading.

I know not everyone is like that and we all have our own way of writing, but just reams of dialogue and no description means, for me at least, that I’m really struggling to become absorbed in this story.

Life is too short to carry on reading a book which you’re struggling to finish, in my humble opinion. So, with a heavy heart, I’ve accepted the fact that I’m going to have to abandon reading this novel and move on to another in my TBR pile.

It has emphasised to me though, the importance of colour and description when writing. It really brings a story and characters alive, making you feel part of it all.

Now I’m off to add some more description to my latest WIP!

Happy Writing and Reading!

Julie X

Julie Shackman is a romance author, witty blogger and friendly tweeter. You can find her blog here, and her latest novel HERO OR ZERO on Amazon here!

August 19, 2015

Who Deserves Privacy?: The Ashley Madison Hack

The Ashley Madison hack – data of thousands of users of the site that urges “Life is Short: Have an Affair” dumped on the “dark web” on Tuesday 18th August – is something that I have found very troubling.

My initial response was something along the lines of this:

It’s hard to feel sorry for a bunch of sleazy, cheating scumbags who’ve fed money into a business that encourages and enables betrayal and infidelity.*

But that’s not really the point.

The point isn’t that they’ve done nothing wrong. The point is that despite the fact that they have done something wrong, they still have a right to privacy.

When nude photos of celebrities were hacked, I defended their right to privacy. I liked them. I supported their right to take private, naked photographs of themselves and share them with whoever they chose to. I don’t like the creeps who use Ashley Madison. I don’t support their right to cheat on their partners. I still support their right to privacy.

Because this is how it works; if we condone this because the people being exposed are seedy and unpleasant, then we condone vigilante privacy-breach as punishment in general, and I don’t think that’s right.

Supporting people’s right to privacy and their freedom to do what they like privately is easy when you agree with what they’re doing. It’s harder when you don’t. It’s harder, but I believe it’s still necessary. Am I disgusted with Ashley Madison’s customer base? Yes. Do I believe they got what they deserved? Maybe, insofar as liars deserve to be revealed. Do I believe that it was right? Certainly not.

It’s easy to cheer on the hackers when they’re attacking the unpopular, but the truth is online we’re all vulernerable. Hacking isn’t really the next frontier of vigilante justice, it’s just vandalism, and as much as I’d love to cheer the demise of Ashley Madison, this hack is no good thing at all.

*I know that I have blogged before about compulsory monogamy in romance novels, but polyamory is not the same as infidelity. I am also aware that my novels deal with extra-marital love-affairs, but these are a. within legendary material, b. in a medieval past, c. not a how-to guide for any marriage.

August 18, 2015

GUEST POST: Wayne Turmel talks writing and rewriting history

Wayne’s debut historical novel is available via Amazon right now! Just click the picture to see it!

When I was writing, “The Count of the Sahara, I encountered a problem common to writers of historical fiction. How much do you stick to the historical record, and how much lee-way do you have to make the characters feel human and interesting?I knew that wouldn’t be a problem with Count Byron de Prorok…. I’ve been obsessed with him since I first discovered him and had access to amazing research that smarter people had already done. I had him down cold.

Half of the story takes place in late 1925 during an archaeological expedition to the Sahara. This was documented in several books, as well as across the front pages of the New York Times so the facts were well known. De Prorok shared a strained relationship with an American graduate student named Alonzo Pond. I knew their relationship was rocky, but Pond always came across as professional, honest, and (maybe as a result) a little dull. As a writer I couldn’t get a handle on him.

Then I found the letter that opened it all up for me.

I was going through the expedition archives at the Logan Museum at Beloit College in Wisconsin, when I came across two letters. The first was from Pond to his boss. Basically it was a very dry report, and as usual Pond was all hepped up about some stone flint he’d found. He casually suggested it would make a great lecture tour, maybe he could make as much as a hundred dollars a lecture (big money for the 1920s). What he got back was a letter congratulating him on their find, but saying in essence, “don’t worry about the lecture tour, we’re sending you to Poland to dig in a swamp when you’re done there.” It was just another example of Pond’s bad luck.

Meanwhile, the Count was making nearly twice that much money, and his lectures were more show than hard science. It drove Pond crazy. That’s when it hit me: it was Amadeus in the Sahara.

If you remember Amadeus, the story of Wolfgang Mozart and the composer Salieri, it was a very one-sided rivalry:

• Mozart was young, Salieri was middle aged

• Mozart was brilliant, Salieri was very good, just not as naturally talented

• Mozart was undisciplined, drunk, rude and frivolous, Salieri did everything by the book

• Mozart was famous and beloved, Salieri worked in relative obscurity and it made him crazy.

That’s what was happening with Pond and de Prorok:

• De Prorok was a tall, handsome, charismatic speaker. Pond was 5’2, hairy and a decent speaker but not in Byron’s league

• De Prorok was a social butterfly, schmoozing and partying, while Pond was loyal to his employers, shy and never happier than when on a dig in the middle of nowhere

• De Prorok was a terrible scientist. He was sloppy, undisciplined, a pathological liar and had no credibility with his peers but was an amazing showman. Pond was very smart, incredibly disciplined and precise, and it made him crazy that he toiled in obscurity while the Count got rich and famous (at least for a while.)

Once I had that dynamic down, the conversations between them flowed naturally and I could make the facts tell a much more interesting tale. As a writer, if you have that one glimmer of insight, it can open the door to an entire world and make boring history a truly human story. I hope I’ve succeeded in doing everyone, especially poor Lonnie Pond, proud.

Wayne Turmel can be found at his own blog, http://wayneturmel.com

Wayne Turmel can be found at his own blog, http://wayneturmel.com

August 11, 2015

Using “Proper English”

In the writing community, there’s obviously a lot of anxiety about being “correct”, and a lot of strident commentary on using “proper” English, including which faux-pas are unforgiveable, and what error might earn you a speedy unfollow or a tut-tut from a fellow writer at the very least.

I used to be 100% invested in the idea of “correct English”. Before I went to University I certainly corrected the kind of miscreants who might leave a preposition to the end of their sentence or who might say “me” when they meant “I” or – sin of sins – split their infinitives with gay abandon, no thought to the sanctity of this our native tongue.

But then when I went to Oxford, I studied the history of the English language, and I learned something that made me see things differently. A lot of things that we think of as “correct English” rules are actually the work of eighteenth-century lexicographers who (to oversimplify massively) wanted to ennoble the English tongue by making sure that it stuck as closely as possible to Latin language rules.

To this end, to give one example of one of these uptight ninnies making anachronistic “improvements”, John Dryden charged through Shakespeare getting rid of all of the “hanging prepositions”. Now, you and I know that a preposition is a very bad thing to end a sentence with (ho ho). So why aren’t we allowed to do it? Shakespeare did it. Medieval English writers did it. Well, it’s because these eighteenth-century fusspots looked at the etymology of the word preposition – pre + position – and decided that because prepositions preceded in Latin, they could not hang at the end of sentences in English.

Likewise, split infinitives. In Latin, and in Old English, because of the grammatical structure of the language infinitives were single words. But we’ve lost that – we don’t inflect our verbs by person or number anymore (except with verbs like go or be), and our infinitive is formed with the auxiliary ‘to’. But once again analogy with Latin added in a late rule which is now often referred to as one of the great tenets of the English language.

I’m not saying this makes it wrong, I’m just saying that we need to be aware of the state of flux our language has always been in before we dash about condemning the energy and variety of “text-speak” and rap lyrics. I’m not saying these should be taught in schools, but there’s an implicit snobbery that comes with condemning variety in favour of only the codified. Likewise, people who criticise Americanisms, often for being new-fangled. American English has changed a lot less than British English, because when we colonised, we clung harder to our native expressions and terms. American English has retained more seventeenth and eighteenth century language quirks than British English. And neither is “right” or “wrong”.

That said, there are some errors that really grate. My pet peeve is people saying “I” when it should be “me”. This is because it stops the sentence making any sense. e.g. “The trouble with him and I is…” take away “him and” and you’ve got nonsense: “The trouble with I is.” Argh!

But obviously as a writer, I care very much about everything that is printed in my novels being correct. And correct to printing-standards. That matters a lot to me. What doesn’t so much is blogging and tweeting – that’s not to say that I don’t care if I make typos (which I often do), just that it’s often nice to embrace the more casual contexts of language use, to be playful, to not worry so much about precision and perfection. English is beautiful and vibrant and changeful. It is a descriptive rather than a prescriptive language – that is to say, there is no great authority of English use, only the way it is used, and the people who use it. That’s what makes it so wonderful, I think.

But what about the rest of you? I’m aware that this is a controversial topic (!) and I’d love to hear what other people think.

August 4, 2015

Old into New: What is “off-limits” when you adapt?

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the process of adaptation, and I’ve written a couple of posts about the dangers of adapting a much-loved story and the fallacy of thinking there is a “right” version of any legendary material. It got me thinking about what can and can’t be changed.

More literature is adaptation than people tend to think. With the rise of printing and then the rise of copyright law, coupled with a post-romantic idea of “inspiration” over imitation, I think we’ve forgotten that there’s nothing really new under the sun. And this is a good thing – the stories of the past are part of how we understand ourselves. But, when you’re adapting, how far is too far?

I am personally of a vaguely Swansonesque persuasion in that, that is to say, for the most part I think people should be free to do with existing material what they wish. That said, if you travel too far from the original then you lose that sense of working with something and remaking it creatively – and remaking is in many ways at least as creative as making new.

That said, I’m yet to come across any Arthuriana that successfully translates the story through time (except perhaps Avalon High, for its shameless disnified tweenieness). I’d be very interested to read one (or perhaps write one one day, ho ho). But that said, every version seems to shuffle things around; family relations, the order of events, goodies baddies etc. And I think that’s what’s attracted me to it the most.

So really I’m just interested to know – what do others consider when they adapt? What is “off-limits”? What’s “fair play”? Does anyone know of any adaptations of *any* stories that have worked particularly well?

August 3, 2015

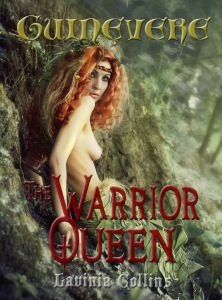

*NEWS* THE WARRIOR QUEEN Arthurian #1 Amazon Bestseller FREE for a short time *NEWS*

July 27, 2015

Walking on Sacred Ground: Guy Ritchie’s King Arthur

The ever lovely Karen Gordon brought the upcoming (well, next year, and I may have died of excitement before then) Guy Ritchie King Arthur reboot to my attention via twitter yesterday.

So I toddled along to EW to read the article, and I was really interested in the way they were marketing it. As this brand-new rough-the-hero-up tough-guy action thing, as though this was what went against the grain of the ‘literary classic’. The sentence that really got me was: “Hopefully, loyalists won’t be too offended by what we’ve done,” says producer Lionel Wigram. I’ll come back to that (and that very real fear, which I have talked about briefly before on this blog) in more detail, but at this point I’d just like to ask, exactly which version are the “loyalists” loyal to?

I’m really intrigued to see how this version goes. I’d not yet describe myself as a fan of Guy Ritchie. I watched Layer Cake twice and all I really remember about it is that nobody ever ate any actual cake. Based on that, I’m kind of anxious about macho man-mumbling and women hanging around like accessories, but there are loads of things I am excited about as well. I can’t wait to see this King Arthur who is ‘a little bit rough around the edges, but he’s basically a survivor.’That sounds great. Also a little shufty at IMDB tells me that Vortigern (in the seemly form of Jude Law) – the British leader who Geoffrey of Monmouth has foolishly making deals with Hengest and Horsa the wicked invading Saxons – will be making an appearance in this version. Much intrigue!

But as I say, what is most interesting to me is Ritchie’s idea that past versions have “[made] King Arthur bland and nice, and nice and bland.” I mean, if we’re talking The Sword in the Stone and (to a lesser extent) The Mists of Avalon, then yeah I could see that he was not one of the more troubling or (dare I say it) interesting characters, but this “bland and nice, nice and bland” guy is the same chap who in the medieval versions a. knocks up his sister, b. tries to have their incest child murdered, instead only manages to murder all babies that age, c. resolutely refuses to do anything about the treason, corruption or infighting in his kingdom until it collapses around him. And that’s just in Malory. Because of how deeply associated with the myth of Britishness King Arthur has become, it does seem that the popular media is saturated by this T.H.White “Once and Future King” who is the saviour of Britain, but that’s not the whole story.

Like Hunnam’s portray promises to be, the old Welsh Arthur is an action hero, whose main bag is riding around with his knights getting shit done. Medieval Scottish romance is much less favourable to Arthur; he’s a bastard, a usurper and – frequently – a tyrant with questionable judgement. To the French he is this Roi fainéant (do-nothing king) who is too busy following his friend around trying to stop him having sex with his wife to get on with the things he should be doing.

And this has been one of the sticking-points I have found in my own experience of rewriting Arthurian legend; our modern understanding of literature and indeed of story is less able to encompass the elasticity of legend the way that medieval and early modern writers did. I daresay it comes along with the rise of copyright law. I am equally tempted to blame it on the Romantics and their idea of a single perfect version of any one story. Whatever it is, it’s daft. Any “loyalists” who aren’t intrigued and thrilled as I am about the promise of this version don’t really know what they are being loyal to.

Reviews on Amazon have criticsed my Arthur for not being “nice” enough (snooze – while we’re here I might suggest this excellent post by Victoria Griffin on writing likeable characters), which I think is shaped by the fact that these are stories that we often come across in our childhoods, where the for-kids versions are shaped to be palatable. Because a palatable hero Arthur is not necessarily. So I can’t wait for this. I can’t wait for some gritty, bloody, down-to-earth version with something to say. Bring it on. And maybe Charlie Hunnam will take his shirt off. Who knows?