Tullian Tchividjian's Blog, page 9

February 26, 2014

One Way Love Video Curriculum

Thanks to my friends at Right Now Media and my publisher David C. Cook, the video curriculum for my book One Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World is now available. I hope and pray that many are wildly blessed by it. Spread the word!

Here is the trailer for the series.

You can find the whole six-part series here.

February 17, 2014

We Don’t Find Grace, Grace Finds Us

I love the introduction to Sally Lloyd-Jones’ Jesus Storybook Bible. A piece of it goes like this:

I love the introduction to Sally Lloyd-Jones’ Jesus Storybook Bible. A piece of it goes like this:

Other people think the Bible is a book of heroes, showing you people you should copy. The Bible does have some heroes in it, but…most of the people in the Bible aren’t heroes at all. They make some big mistakes (sometimes on purpose). They get afraid and run away. At times they are downright mean. No, the Bible isn’t a book of rules, or a book of heroes. The Bible is most of all a story. It’s an adventure story about a young Hero who comes from a far country to win back his lost treasure. It’s a love story about a brave Prince who leaves his palace, his throne – everything – to rescue the one he loves.

She’s right. I think that most people, when they read the Bible (and especially when they read the Old Testament), read it as a catalog of heroes (on the one hand) and cautionary tales (on the other). For instance, don’t be like Cain — he killed his brother in a fit of jealousy – but do be like David: God asked him to do something crazy, and he had the faith to follow through.

Since Genesis 3 we have been addicted to setting our sights on something, someone, smaller than Jesus. Why? It’s not that there aren’t things about certain people in the Bible that aren’t admirable. Of course there are. We quickly forget, however, that whatever we see in them that is commendable is a reflection of the gift of righteousness they’ve received from God-it is nothing about them in and of itself.

Running counter to this idea of Bible-as-hero-catalog, I find that the best news in the Bible is that God incessantly comes to the down-trodden, broken, and non-heroic characters. It’s good news because it means he comes to people like me — and like you.

Our impulse to protect Bible characters and make them the “end” of the story happens almost universally with the story of Noah.

Noah is often presented to us as the first character in the Bible really worthy of emulation. Adam? Sinner. Eve? Sinner. Cain? Big sinner! But Noah? Finally, someone we can set our sights on, someone we can shape our lives after, right? This is why so many Sunday School lessons handle the story of Noah like this: “Remember, you can believe what God says! Just like Noah! You too can stand up to unrighteousness and wickedness in our world like Noah did. Don’t be like the bad people who mocked Noah. Be like Noah.”

I understand why many would read this account in this way. After all, doesn’t the Bible say that Noah “was a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time, and he walked faithfully with God” (Genesis 6:9)? Pretty incontrovertible, right?

Not so fast.

Let’s take a closer look. You can’t understand verse 9 properly unless you understand its context. Here’s the whole section, verses 5-7:

The Lord saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time. The Lord regretted that he had made human beings on the earth, and his heart was deeply troubled. So the Lord said, “I will wipe from the face of the earth the human race I have created—and with them the animals, the birds and the creatures that move along the ground—for I regret that I have made them.”

Now that’s a little different, isn’t it? Look at all the superlatives: every inclination, only evil, all the time! That kind of language doesn’t leave a lot of room for exceptions…and “exception” is just the way Noah has always been described to me. “Well,” I hear, “Everyone was sinful except Noah. He was able to be a righteous man in a sinful world…it’s what we’re all called to be.” But that’s not at all what God says! He says, simply and bluntly, that he “will wipe from the face of the earth the human race I have created.” No exceptions. No exclusions.

So what happens? How do we get from verse 7 (“I will wipe from the face of the earth the human race I have created…for I regret that I have made them.”) to verse 9 (“Noah was a righteous man.”)? We get from here to there – from sin to righteousness — by the glory of verse 8, which highlights the glory of God’s initiating grace.

“But Noah found favor in the eyes of the Lord” (Genesis 6:8).

Some read this and make it sound like God is scouring the earth to find someone—anyone—who is righteous. And then one day, while searching high and low, God sees Noah and breathes a Divine sigh of relief. “Phew…there’s at least one.” But that’s not what it says.

“Favor” here is the same word that is translated elsewhere as “grace.” In other words, as is the case with all of us who know God, it was God who found us—we didn’t find God. We are where we are today, not because we found grace, but because grace found us. In his book Surprised by Joy, C.S. Lewis recounts his own conversion with these memorable words:

You must picture me alone in my room, night after night, feeling the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had come upon me. In the fall term of 1929 I gave in and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most reluctant convert in all England. Modern people cheerfully talk about the search for God. To me, as I then was, they might as well have talked about the mouse’s search for the cat.

It took the grace of God to move Noah from the ranks of the all-encompassing unrighteous onto the rolls of the redeemed. Pay special attention to the order of things: 1) Noah is a sinner, 2) God’s grace comes to Noah, and 3) Noah is righteous. Noah’s righteousness is not a precondition for his receiving favor (though we are wired to read it this way)…his righteousness is a result of his having already received favor!

The Gospel is not a story of God meeting sinners half-way, of God desperately hoping to find that one righteous man on whom he can bestow his favor. The news is so much better than that. The Gospel is that “while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). Sinners like Noah, like you, and like me are recipients of a descending, one-way love that changes everything, breathes new life into dead people, and has the power to carry us from unrighteousness to righteousness without an ounce of help.

So, even in the story of Noah, we see that the Bible is a not a record of the blessed good, but rather the blessed bad. The Bible is not a witness to the best people making it up to God; it’s a witness to God making it down to the worst people. Far from being a book full of moral heroes whom we are commanded to emulate, what we discover is that the so-called heroes in the Bible are not really heroes at all. They fall and fail; they make huge mistakes; they get afraid; they’re selfish, deceptive, egotistical, and unreliable. The Bible is one long story of God meeting our rebellion with His rescue, our sin with His salvation, our guilt with His grace, our badness with His goodness.

Yes, God is the hero of every story—even the story of Noah.

February 14, 2014

Jeremy Abbott and Freedom in Failure

Nick Lannon, editor-in-chief of LIBERATE, wrote an amazing gospel reflection on figure skater Jeremy Abbott’s epic fall last night during his routine:

Nick Lannon, editor-in-chief of LIBERATE, wrote an amazing gospel reflection on figure skater Jeremy Abbott’s epic fall last night during his routine:

It is when we can look ourselves in the mirror and be honest about what we see: failings, sins, and shortcomings, that we can begin to live our lives with some measure of freedom. As long as we look in that mirror and tell ourselves that glory is possible (Olympic or otherwise), we’ll be like Jeremy Abbott before “the fall”: a nervous wreck. We’ll be terrified of exposure, of failure…of being outed as frauds.

Admitting from the beginning that we are a failure in need of profound rescue from the outside makes it all the easier to accept that salvation. Martin Luther famously said that the quest for glory could never be satisfied; that it must be extinguished. This is perhaps most clearly obvious during the Olympics. For every gold medal awarded, there are hundreds of athletes who leave with their arms in slings, their egos bruised, and their dreams crushed. In the same way, for every Mother Teresa, there’s a you and me. Of course, our freedom is even better than Abbott’s: our errors, our embarrassing falls, and our public disgraces have been give to a substitute. His perfect score has been given to us. We now live secure in the knowledge that when the “judges” (the Judge) regard us, they see only God’s blameless son, Jesus Christ. The next time Jeremy Abbott skates that program, that fall will come back to him. He’ll worry about it, and hope it doesn’t happen again. Our falls can never come back to us. They were nailed to a cross 2,000 years ago.

Read the rest here.

February 10, 2014

“LiveStrong” Christianity

A couple months back I wrote about Reader’s Digest Christianity, and how it reduced the Christian faith to pithy, easily-achievable goals that ensure our personal improvement. Here, I have a different (though depressingly similar) target: “LiveStrong” Christianity. LiveStrong bracelets are today even more popular than the infamous WWJD bracelets were 10 years ago, despite the public fall from grace of their namesake, Lance Armstrong.

A couple months back I wrote about Reader’s Digest Christianity, and how it reduced the Christian faith to pithy, easily-achievable goals that ensure our personal improvement. Here, I have a different (though depressingly similar) target: “LiveStrong” Christianity. LiveStrong bracelets are today even more popular than the infamous WWJD bracelets were 10 years ago, despite the public fall from grace of their namesake, Lance Armstrong.

In the minds of many people inside the church, “Livestrong” is the essence and goal of Christianity. You hear this obsession in our lingo: We talk about someone having “strong faith,” about someone being a “strong Christian,” a “prayer warrior,” or a “mighty man/woman of God.” We want to believe that we can do it all, handle it all. We desperately want to think that we are competent and capable— we’ve concluded that our life and our witness depend on our strength. No one wants to declare deficiency. We even turn the commands that seem to have nothing to do with strength (“Blessed are the meek” or “Turn the other cheek”) into opportunities to showcase our spiritual might. I saw a church billboard the other day that said, “Think being meek is weak? Try being meek for a week!”

We like our Christianity to be muscular, triumphant. We’ve come to believe that the Christian life is a progression from weakness to strength—”Started from the bottom, now we’re here” (Drake) seems to be the victory chant of modern Christianity. We are all by nature, in the terminology of Martin Luther, theologians of glory—not God’s glory, but our own.

But is the progression from weakness to strength the pattern we see throughout the Bible?

Take Samson, for instance. As a kid growing up idolizing Rocky, Rambo, and Conan the Barbarian, the story of Samson was right up my alley. I may have been bored by the rest of the Bible, but not the Samson narrative. Anybody who could kill a thousand bad guys with the jawbone of a donkey had my respect. He was the Wolverine of the Old Testament and I wanted to be just like him. Samson seems, at first blush, to be an exemplar of “Livestrong” Christianity.

The story of Samson is actually the exact opposite of the “weakness to strength” paradigm that has come to mark our understanding of the Christian life. Samson’s story shows us that the rhythm of Christian growth is a progression from strength to weakness, rather than weakness to strength.

Samson starts off strong. He’s invincible. Seemingly indestructible. Clearly unbeatable. He’s what we all want to be—what, down deep, we’re all striving to be. Maybe not physically, but spiritually.

We think his strength is in his hair (heck, even Samson thought that his strength was in his hair), but before every great deed Samson performed, we read, “The Spirit of the Lord rushed upon him.” Before he tears a lion apart with his bare hands (Judges 14:6), before he kills the 30 men of Ashkelon (14:19), and before he kills a thousand men with the jawbone of a donkey (15:14), the exact same phrase is used: “The Spirit of the Lord rushed upon him.” The author of Judges is at pains to make it clear that these feats of strength are not Samson’s, but God’s.

Think about the times in your life when other people have told you that your faith was strong. Aren’t people always saying that when you feel the weakest? When you feel like you’re barely hanging on? There’s something to be said for the real-world truth of Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 1:27—”But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong.” It is when we feel foolish that God shows himself to be wise. It is when we feel weak that God shows himself to be strong.

The Philistines are not defeated until Samson is weakened. His hair is shaved, his eyes are gouged out, and he’s chained up like an animal in the zoo. He finally realizes that he is weak and that God alone is strong and so he prays and asks God for a generous portion of strength. God answers his prayer and Samson brings the building down on himself and all the lords of the Philistines. It is when Samson is at his weakest that he is most powerfully used.

Gideon experienced something similar to Samson. Gideon is prepared to fight a battle. He’s got his army ready—32,000 strong. But God reduces his army from 32,000 to 10,000 by getting rid of everyone who’s afraid. Then he reduces the army from 10,000 to 300, keeping only those who drink “like a dog.” Then he reduces their weaponry to trumpets and empty jars. No knives, no swords, no spears. God wants to make it obvious that their promised victory is owing to his strength, not theirs.

We see this same pattern in the life of the Apostle Paul. By his own admission (Phil. 3:4-6) he started off strong. His spiritual resume was more impressive than anybody else’s. And yet God systematically broke him down throughout his life so that by life’s end he was saying stuff like, “I’m the worst guy I know” and “I’m the least of all the saints” and “For when I am weak, then I am strong.”

The hope of the Christian faith is dependent on God’s display of strength, not ours. God is in the business of destroying our idol of self-sufficiency in order to reveal himself as our sole sufficiency. This is God’s way—he kills in order to make alive; he strips us in order to give us new clothes. He lays us flat on our back so that we’re forced to look up. God’s office of grace is located at the end of our rope. The thing we least want to admit is the one thing that can set us free: the fact that we’re weak. The message of the Gospel will only make sense to those who have run out of options and have come to the relieving realization that they’re not strong. Counterintuitively, our weakness is our greatest strength.

So, the Christian life is a progression. But it’s not an upward progression from weakness to strength—it’s a downward progression from strength to weakness. And this is good news because “Livestrong” Christianity is exhausting and enslaving. The strength of God alone can liberate us from the burden of needing to be strong—the sufficiency of God alone can relieve us of the weight we feel to be sufficient. As I’ve said before, Christian growth is not, “I’m getting stronger and stronger, more and more competent every day.” Rather, it’s “I’m becoming increasingly aware of just how weak and incompetent I am and how strong and competent Jesus was, and continues to be, for me.”

Because Jesus paid it all, we are set free from the pressure of having to do it all. We are weak. He is strong.

February 7, 2014

What Of It?

“So when the devil throws your sins in your face and declares that you deserve death and hell, tell him this: ‘I admit that I deserve death and hell, what of it? For I know One who suffered and made satisfaction on my behalf. His name is Jesus Christ, Son of God, and where He is there I shall be also!’” (Martin Luther).

“So when the devil throws your sins in your face and declares that you deserve death and hell, tell him this: ‘I admit that I deserve death and hell, what of it? For I know One who suffered and made satisfaction on my behalf. His name is Jesus Christ, Son of God, and where He is there I shall be also!’” (Martin Luther).

Well may the Accuser roar, of sins that I have done; I know them all and thousands more, Jehovah knoweth none!

February 3, 2014

God Threw A Stone

As I’ve said before, God speaks two words to the world. People have called them many things: Law and Gospel, Judgment and Love, Critique and Grace, and so on. In essence, though, it’s pretty simple: first God gives us bad news (about us) and then He gives us Good News (about Jesus).

As I’ve said before, God speaks two words to the world. People have called them many things: Law and Gospel, Judgment and Love, Critique and Grace, and so on. In essence, though, it’s pretty simple: first God gives us bad news (about us) and then He gives us Good News (about Jesus).

This is perhaps most clearly seen in another incredibly well-known (and incredibly misunderstood) passage of Scripture: Jesus’ interaction with the woman caught in the act of adultery.

The scribes and Pharisees catch a woman in the act of adultery, and drag her before Jesus. Can you imagine a woman who ever felt more shame than this one? Literally caught in the act of adultery? Unfathomable. They tell Jesus of her infraction, and remind him that the law of Moses says such women should be stoned. Then they issue a challenge: “What do you say?” They’re trying to trick Jesus into admitting what they suspect: that he’s “soft” on the Law.

Boy, were they wrong.

Confronted by this test, Jesus bends down and writes in the sand with his finger. Now, we aren’t told what he writes, but I think it’s instructive to look at the only other instances in the Bible where God writes with his finger. The first is obvious: The inscription of the 10 Commandments on the stone tablets. The second, though, is less well-known.

In Daniel 5, King Belshazzar is having a huge party, at which “they praised the gods of gold and silver, of bronze, iron, wood and stone” (v. 4). Suddenly, a hand appears and begins writing on the wall. When Daniel is called in to translate the writing, this is what it is revealed to say: “Mene: God has numbered the days of your reign and brought it to an end. Tekel: You have been weighed on the scales and found wanting. Peres: Your kingdom is divided and given to the Medes and Persians.” There can be no doubt that these are three words of judgment—i.e. Law. “You have been weighed on the scales and found wanting.” Has a more chilling word of judgment ever been uttered?

So the two other times God wrote with his finger, he wrote law. I don’t think, therefore, it’s a stretch to think that when Jesus writes in the sand with his finger, he’s writing law. I like to think that perhaps Jesus wrote, “Anyone who even looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Matt. 5:28).

Far from being “soft” on the Law, Jesus shows just how high the bar of the law is. How do we know? Because the scribes and Pharisees respond the same way that all of us respond when we are confronted with depth of God’s inflexible demands—they scattered. Beginning with the oldest ones, they all, like the rich young ruler, walked away defeated.

When Jesus and the woman are left alone, and she acknowledges that no one remains to condemn her, Jesus speaks his final word to her: “Neither do I condemn you; go, and from now on sin no more” (John 8:11). This is where the story gets misunderstood.

“Aha!” we cry. “See! Jesus tells her to shape up! He leaves her with an exhortation!” But look at the order of Jesus’ words: First, he tells the woman that he does not condemn her. Only then does he instruct her to sin no more. This is enormous. He does not make his love conditional on her behavior. He does not say, “Go, sin no more, and check back with me in six months. If you’ve been good, I won’t condemn you.”

No. Our Savior does so much better than that.

Jesus creates new life in the woman by loving her unconditionally, with no-strings-attached. By forgiving her profound shame, he impacts her profoundly. Now free from condemnation, she walks away determined to leave her old life behind. As this account demonstrates, redeeming unconditional love alone (not law, not fear, not punishment, not guilt, not shame) carries the power to compel heart-felt loyalty to the One who gave us (and continues to give us) what we don’t deserve (2 Corinthians 5:14).

Like the adulterous woman, we are all caught in the act—discovered in a shameful breach of God’s law. Though no one on earth can throw the first stone, God can. And he did. The wonder of all wonders is that the rock of condemnation that we justly deserved was hurled by the Father onto the Son. The law-maker became the law-keeper and died for us, the law-breakers. “In my place condemned He stood; and sealed my pardon with His blood. Hallelujah, what a Savior.”

January 27, 2014

Who Is The Good Samaritan?

For every good story in the Bible there’s a bad children’s song. This is the one I remember for the Good Samaritan:

For every good story in the Bible there’s a bad children’s song. This is the one I remember for the Good Samaritan:

The man who stopped to help, right when he saw the need; he was such a good, good neighbor, a good example for me.

On the surface, this little diddy may seem harmless. The problem, however, is that Jesus wants us to identify with every person in the parable except the good Samaritan. He reserves that role for himself.

“You should be like the Good Samaritan.” If you grew up in church or Sunday School, you probably heard this a thousand times. In fact, even outside the church, the parable of the Good Samaritan is used to exhort neighborly love and concern for the downtrodden. This parable is perhaps the best known story Jesus ever told after the parable of The Prodigal Son. It is, however, also the most misunderstood.

You know the story: a man is walking down the road when he is set upon by robbers, who mug him, beat him, and leave him for dead. As he lies, suffering, in the roadside ditch, a priest and a Levite, in turn, pass by on the other side of the street, preferring not to get their hands dirty. It is the hated half-breed—a Samaritan—who comes to the man’s aid, setting him on his donkey, taking him to an inn, paying the inn-keeper to take care of him and promising to return to see that his needs are attended to.

You also know the common interpretation: don’t be like the priest and the Levite, too concerned with themselves to help another. Be like the Good Samaritan – be a good neighbor. In other words, our preachers want us to (at least eventually) identify with the Good Samaritan, the hero of the story.

The parable of The Good Samaritan is the second of the great commandments in narrative form: love your neighbor as yourself. In fact, Jesus tells the story to answer a lawyer’s question about who his neighbor is. The lawyer, trying to trick Jesus, asks him what he must do to inherit eternal life. Jesus tells him to follow the laws he already knows so well: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind;” and, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Luke 10:27). Then, “seeking to justify himself,” the lawyer asked Jesus a follow-up question: “And who is my neighbor?”

Jesus answers him by telling the parable of The Good Samaritan…and we miss the point completely.

If Jesus had been asked, “How should we treat our neighbors?” and had responded with this story, perhaps “Be like the Good Samaritan” would be an acceptable interpretation. Instead, Jesus was asked, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” He was asked a vertical question (a question about a person’s relationship to God) rather than a horizontal one. The lawyer was, after all, seeking to “justify” himself. This parable must, therefore, be interpreted vertically. It’s about justification, not sanctification.

The context puts Jesus’ final exhortation to “go and do likewise” in perspective. Remember, this is the same Jesus who told his audience at the Sermon on the Mount that they “must be perfect, as [their] Father in Heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48). What Jesus is saying in the parable of The Good Samaritan is that, to inherit eternal life, you must keep God’s law perfectly—which includes loving your neighbor as yourself. No wiggle room. You must always love perfectly, sacrificially, selflessly—not just on the outside, but on the inside too. You must, in other words, always want to love perfectly, sacrificially, and selflessly. You must never hurt anyone—physically, emotionally, relationally. And you must always help everyone—physically, emotionally, relationally. You must never harbor grudges. Never. You must never seek retribution. Ever. You must never want to seek retribution. When someone cheats you, instead of trying to get your stuff or money back, you have to give them more. You have to turn the other cheek to your most aggressive enemies. You must love perfectly.

“Go and do likewise” is, therefore, not a word of invitation to be nice. It’s a word of condemnation in answer to the laywer’s question, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?”

Far from telling the story to help us become like The Good Samaritan, Jesus tells this story to show us how far from being like The Good Samaritan we actually are! Jesus’ parable destroys our efforts to justify ourselves; to find a class of people we can call “neighbors” that we actually do love. In destroying our self-salvation projects, the story of The Good Samaritan destroys us. Jesus brings the hammer of the Law (“Be perfect…”) down on our self-justifying work.

In a rich irony, we move from being identified with the priest and the Levite who never perfectly love our best friends “as ourselves,” much less our enemies, to being identified with the traveler in desperate need of salvation. Jesus intends the parable itself to leave us beaten and bloodied, lying in a ditch, like the man in the story. We are the breathless bruised. We are the needy, unable to do anything to help ourselves. We are the broken people, beaten up by life, robbed of hope.

But then Jesus comes.

Unlike the Priest and Levite, He doesn’t avoid us. He crosses the street—from heaven to earth—comes into our mess, gets his hands dirty. At great cost to himself on the cross, he heals our wounds, covers our nakedness, and loves us with a no-strings-attached love. He brings us to the Father and promises that his “help” is not simply a one time gift—rather, it’s a gift that will forever cover “the charges” we incur.

Yes, Jesus and Jesus alone is the Good Samaritan.

January 23, 2014

Now I See That Which Is Done

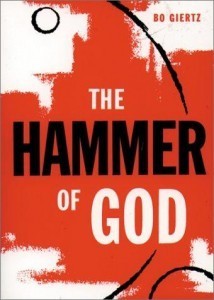

In my interview last week with my friend Rev. Dr. Matthew R. Richard, I mentioned that one of the books I have read and re-read many times in the past few years–a book that has had a profound influence on me–is Bo Giertz’s (1905-1988) fictional work The Hammer of God. Giertz was a Lutheran theologian, novelist and bishop of the Gothenburg Lutheran Diocese from 1949 to 1970. A relatively unknown book in Evangelical circles, Leland Ryken–longtime literature professor at Wheaton College–referred to The Hammer of God as “one of the best literary finds I have ever made.” I couldn’t agree more!

In my interview last week with my friend Rev. Dr. Matthew R. Richard, I mentioned that one of the books I have read and re-read many times in the past few years–a book that has had a profound influence on me–is Bo Giertz’s (1905-1988) fictional work The Hammer of God. Giertz was a Lutheran theologian, novelist and bishop of the Gothenburg Lutheran Diocese from 1949 to 1970. A relatively unknown book in Evangelical circles, Leland Ryken–longtime literature professor at Wheaton College–referred to The Hammer of God as “one of the best literary finds I have ever made.” I couldn’t agree more!

After sitting on my shelf uncracked for far too long, I finally decided a few summers ago to read The Hammer of God (first published in 1941). I first heard about it from my friends Elyse Fitzpatrick and Mike Horton. I couldn’t put it down. It was simply breathtaking. It tells three stories (novellas) of three different pastors who learn in three different ways the nature and necessity of relying on God’s grace. It is law/gospel theology in captivating narrative form. You have to read it.

To whet your appetite, I want to share one part that I found especially illuminating for preachers. I need to first give some context, though.

Set in Sweden in the early 1800-s, Henrik is a young, remarkably gifted and fiery preacher who very much looks up to Justus Johan Linder, a preacher ten years his senior. Henrik is having a crisis of faith. Bothered by the behavioral worldliness all around him, he has become widely known for his passionate pleas and exhortations for people to stop sinning. He’s meticulous in his examination of sinful behavior both in and out of the pulpit. And it is bearing fruit. The church is packed every Sunday and licentious behavior is declining in the village. But, much to his surprise, “new sins” are popping up everywhere. He notices that while drinking and debauchery may be at an all time low, a self-righteous and legalistic hardness of heart has emerged in their place. While on the one hand Henrik is encouraged to see external worldliness dissipating, he’s remarkably discouraged to see a cold, loveless culture developing. Not only that, but now he’s beginning to realize the depth of his own sin. In despair over his own inability to be as good as he tells other people to be, he breaks down and confesses to Linder that he’s not even sure he’s saved. Linder’s response is pure gold:

Henrik, we must start again from the beginning. We have thundered like the storm [speaking of the way he and Henrik have preached God's Law], we have bombarded with the heaviest mortars of God’s Law in an attempt to break down the walls of sin. And that was surely right. I still load my gun with the best powder when I aim at unrepentance. But we had almost forgotten to let the sunshine of the gospel shine through the clouds. Our method has been to destroy all carnal security by our volley’s, but we have left it to the soul’s to build something new with their own resolutions and their own honest attempts at amending their lives. In that way, Henrik, it is never finished. We have not become finished ourselves. Now I have instead begun to preach about that which is finished, about that which is built on Calvary and which is a safe fortress to come to when the thunder rolls over our sinful heads. And now I always apportion the Word of God in three directions, not only to the self-satisfied [the bad people] as I did formerly, but also to the awakened [the "good" people] and to the anxious, the heavy laden and to the poor in spirit. And I find strength each day for my own poor heart at the fount of redemption.

Henrik is captivated by the “new” way in which Linder is preaching and he asks about the results. “Do you note any difference?”

Linder answers:

In the first place, I myself see light where formerly I saw only darkness. There is light in my heart and light over the congregation. Before, I was in despair over my people, at their impenitence. I see now that this was because I kept thinking that everything depended on what we should do, for when I saw so little of true repentance and victory over sin, helplessness crept into my heart. I counted and summed up all that they did [to clean up their act], and not the smallest percentage of debt was paid. But now I see that which is done, and I see that the whole debt is paid. Now therefore I go about my duties as might a prison warden who carries in his pocket a letter of pardon for all his criminals. Do you wonder why I am so happy? Now I see everything in the sun’s light. If God has done so much already, surely there is hope for what remains.

The way Linder describes the transformation that took place in his preaching is almost identical to the transformation that took place in mine. I have a long way to go (bad habits die slowly), but a number of years ago a Copernican revolution of sorts took place in my own heart regarding the need to preach the law then the gospel without going back to the law as a way to maintain God’s love and favor.

Preachers these days are expected to major in “moral renovation.” They are expected to provide a practical “to-do” list, rather than announce, “It is finished.” They are expected to do something other than–more than–lift up before their congregation Christ’s finished work, preaching a full absolution solely on the basis of the complete righteousness of Another. To be sure, preachers need to “load their guns with the best powder when aiming at unrepentance”, but far too often a preacher’s final word to Christians is law and not Gospel. To finish a sermon asking “What would Jesus do?” instead of announcing “This is what Jesus has done!” is to betray the final word God speaks over Christians.

Preachers these days are expected to major in “moral renovation.” They are expected to provide a practical “to-do” list, rather than announce, “It is finished.” They are expected to do something other than–more than–lift up before their congregation Christ’s finished work, preaching a full absolution solely on the basis of the complete righteousness of Another. To be sure, preachers need to “load their guns with the best powder when aiming at unrepentance”, but far too often a preacher’s final word to Christians is law and not Gospel. To finish a sermon asking “What would Jesus do?” instead of announcing “This is what Jesus has done!” is to betray the final word God speaks over Christians.

“Life is a web of trials and temptations”, says Robert Capon, “but only one of them can ever be fatal-the temptation to think it is by further, better, and more aggressive living that we can have life.” Given this sobering statement, it would seem that many preachers unwittingly lead their congregations “into temptation” by implying that you can live your way to life. The fact is, however, that you can only “die your way there, lose your way there…For Jesus came to raise the dead. He did not come to reward the rewardable, improve the improvable, or correct the correctable; he came simply to be the resurrection and the life of those who will take their stand on a death he can use instead of on a life he cannot.” After our preaching of the law rightly pushes people under water, we all too often lead them to think that they must “save” themselves by giving them swimming lessons: “Paddle harder, kick faster.”

I want the last word I speak over Christians when I preach to be the last word God speaks over Christians-”Paid in full.” The Gospel always has the last word over a believer. Always. When it’s all said and done there are two types of sermons: Jesus + Nothing = Everything or Jesus + Something = Everything.

May God raise up a generation of bold preachers who storm the gates of works-righteousness in all its forms with nothing more and nothing less than, “In my place condemned he stood, and sealed my pardon with his blood. Hallelujah, what a Savior.”

January 20, 2014

Go Ahead…Talk To A Lutheran

Those of us who have a blog here at The Gospel Coalition would readily admit that while we each have an ecclesiastical home and a theological tradition (Baptist or Presbyterian or Anglican, etc.) we have gleaned much from, and been influenced by, those from other ecclesiastical homes and theological traditions. Borrowing an analogy from C.S. Lewis, we each have rooms in which we live, but we gather in the hallway with those from other rooms to meet and talk and listen. It would be a mistake to live in the hallway. After all, “it is in the rooms, not the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals” (C.S. Lewis). But it would also be a mistake to never leave your room. The way I see it, The Gospel Coalition is a “hallway”, not a room. It’s a place where Presbyterians and Baptists and Anglicans and Episcopalians and others who trace their theological roots back to the Reformation, gather for conversation–both talking and listening. We don’t live here, but we have conversations here.

Those of us who have a blog here at The Gospel Coalition would readily admit that while we each have an ecclesiastical home and a theological tradition (Baptist or Presbyterian or Anglican, etc.) we have gleaned much from, and been influenced by, those from other ecclesiastical homes and theological traditions. Borrowing an analogy from C.S. Lewis, we each have rooms in which we live, but we gather in the hallway with those from other rooms to meet and talk and listen. It would be a mistake to live in the hallway. After all, “it is in the rooms, not the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals” (C.S. Lewis). But it would also be a mistake to never leave your room. The way I see it, The Gospel Coalition is a “hallway”, not a room. It’s a place where Presbyterians and Baptists and Anglicans and Episcopalians and others who trace their theological roots back to the Reformation, gather for conversation–both talking and listening. We don’t live here, but we have conversations here.

While Baptists and Presbyterians, for example, will not agree on things like sacraments, church government, worship, spiritual gifts, and so on, they still talk. One of the voices that is largely missing from our “hallway” conversations is the Lutheran voice–an absence that would have been odd to American Reformed folks from just a century ago, according to Michael Horton. “Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield, Geerhardus Vos and Herman Bavinck, would not have understood this development…they took it for granted that confessional Lutheran and Reformed Christians were natural allies, joined at the hip on major issues” (Horton).

I’m not exactly sure why (or how) this has happened, but I think our conversations suffer to the degree that confessional Lutherans are not included. (Granted, some of them do not want to be included–some Lutherans can be just as insular as some Presbyterians and some Baptists.) As a Presbyterian, I have benefited greatly from being in conversations with Baptists, Anglicans, Episcopalians–and Lutherans. I’d love to see our hallway conversations include more talking with and listening to our Lutheran brothers and sisters. I think you’ll find that there are few people who are more theologically serious and pastorally sensitive than Lutherans.

Last week I had the privilege of being interviewed by a couple of different Lutheran ministries. After listening to, and reading, my conversations with them, I hope you will add them to the list of people you engage in conversation when you come out of your room and into the hallway.

The first is a website called Steadfast Lutherans–a very popular blog in Lutheranism, getting around 2,000,000 page-views each year. My friend Rev. Dr. Matthew R. Richard interviewed me regarding my interaction with Lutherans.

Here’s a small sample:

Pr. Richard: Tullian, within Lutheran circles I have heard people refer to you as a ‘closet Lutheran.’ This is obviously a tremendous complement from my perspective. What are your thoughts about this and is it true?

Pr. Tchividjian: [Laughing] I’ve heard that too. People who know me, however, know that I’m not a closet anything. I’m pretty outspoken and unashamed about what I believe and why. I wish I had the kind of personality that was subtle, but I don’t. I have some theological differences with my Lutheran friends which is why I am a Presbyterian. But I will joyfully admit that few theologians have helped me more than Lutheran theologians. They tend to be much more down-to-earth and realistic, with little tolerance for theoretical descriptions of the human condition and God’s saving grace. They are existential realists, rather than idealists. They’ve helped me better understand my sin, God’s grace, and the Reformational distinction between the law and the gospel. They’ve guided me through deep and wide pastoral challenges and, I think, made me a better preacher, pastor, and counselor.

You can read Part 1 of the interview here. And you can read Part 2 of the interview here.

The second you may be more familiar with. My friend Chris Rosebrough has a ministry called Pirate Christian Radio. This is an audio interview where we cover my background, issues pertaining to law and gospel, and my book One Way Love. You can listen here (with an encore presentation of Dr. Rod Rosenbladt’s amazing sermon The Gospel for Those Broken by the Church).

I hope you enjoy these hallway conversations. I did. And I hope they encourage you to have some of your own.

January 14, 2014

Papa Please Preach

LIBERATE’s editor-in-chief, Nick Lannon, has an incredibly helpful piece here on how and why the words “preach” and “preaching” has fallen on hard times:

LIBERATE’s editor-in-chief, Nick Lannon, has an incredibly helpful piece here on how and why the words “preach” and “preaching” has fallen on hard times:

You know that churches have dropped the ball when one of the foundational words about church has become a slur. The term “preach” has been so sullied by the church that it has become almost unusable in polite secular conversation.

Think of the classic Madonna song “Papa Don’t Preach”:

Papa I know you’re going to be upset

‘Cause I was always your little girl

But you should know by now

I’m not a baby

You always taught me right from wrong

I need your help, daddy please be strong

I may be young at heart

But I know what I’m saying

The one you warned me all about

The one you said I could do without

We’re in an awful mess, and I don’t mean maybe – please

Papa don’t preach, I’m in trouble deep

Papa don’t preach, I’ve been losing sleep

But I made up my mind, I’m keeping my baby, oh

I’m gonna keep my baby

So, Madonna has messed up. She’s been seeing a guy of whom her father doesn’t approve, and she’s gotten pregnant. In her own words, they’re “in an awful mess.” So she goes to her father, and her one request is that he not “preach.”

Phrases like, “don’t preach at me,” or “I didn’t like that movie; it was so preachy” shine a light on the redefinition of the word: “to preach,” in common parlance, now means “to judge” or “to criticize.” When the Madonna of the song goes to her father, she’s saying, “I already know that what I did was wrong, so I don’t need you to tell me again. I need your help, not a sermon.”

And who wouldn’t agree with that sentiment? “I need your help, not a sermon.” But that’s the tragedy: sermons are supposed to help!

Read the rest here.

Tullian Tchividjian's Blog

- Tullian Tchividjian's profile

- 142 followers