Kathleen B. Jones's Blog, page 3

December 6, 2013

Thinking and Moral Considerations

“There exists in our society widespread fear of judging…[B]ehind the unwillingness to judge lurks the suspicion that no one is a free agent, and hence doubt that anyone is responsible or could be expected to answer for what he has done…Who has ever maintained that by judging a wrong I presuppose that I myself would be incapable of committing it?” (From Hannah Arendt, ”Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship.”)

It’s difficult to know where to begin to counter the errors, misreadings, and plain obfuscations of Arendt’s point of view in the essay by Richard Brody that appeared a few days ago in The New Yorker online. But perhaps the most glaring mistake Brody makes is to confuse what Arendt wrote about “thinking” with some form of “intellectualism.” To begin with, when, in her interview with Gunther Gaus, she makes the point that it was the betrayal by “friends” that she found most shocking this is not because she thought only intellectuals could think or were the only ones to have “ideas” but that they “believed”—without thinking!—the very “ideas” they had fabricated, without considering where these “ideas” might take them. They were “trapped” in their ideas, which is why Arendt, in the same interview, refused to call herself a philosopher, cut off from the world, and insisted she was a political theorist.

Thinking depends on letting the imagination go visiting, and Arendt argued it was Eichmann’s inability to think from the standpoint of anyone else that made him “thoughtless” and hence become unable to distinguish right from wrong. But the same could be said, for different reasons, of the “intellectuals” Arendt referred to and said she’d found so grotesque in the interview with Gaus. And, whether you like where it took her or not, thinking from the standpoint of others was exactly what she practiced in the case of her judgment of the leaders of the Jewish Councils. She imagined they might not have cooperated. Yes, they faced “fear and despair,” as Brody notes, but Arendt imagined it was still possible not to comply even in the face of significant threats and consequences. And the historical evidence indicates this to be the case: not everyone complied.

Yet nowhere does Arendt claim the ability to judge a situation means I myself (or she) necessarily would have done anything differently. The most chilling conclusion she reached from her reflections on the trial is that there are no guarantees “when the chips are down” that I will know the right thing to do, and just do it. And it was her confrontation with Eichmann’s banality—not what he did, but who he showed he was, and “how many were like him” during this time—that led Arendt to warn near the end of the book that once such crimes had entered the human experience it is entirely possible that “similar crimes may be committed in the future.”

In an interview with Roger Errera, from which Brody also quotes, Arendt remarked that her intention was in writing about Eichmann as she did was to “destroy the legend of the greatness of evil.” As she was thinking about this issue she said she’d “found in Brecht the following remark: ‘The great political criminals must be exposed and exposed especially to laughter.’” And her “tone” in Eichmann in Jerusalem was an attempt to do just that: expose the criminals to derision.

It was the banality of the criminals—not the crimes they committed—that gave Arendt such a shock she responded with laughter. And it’s a shame Brody doesn’t understand what this signifies: the humanization of perpetrators actually serves to humanize victims as well. She did not equate the responsibility of “persecutors and persecuted” for crimes committed by the Nazi state, as Brody claims. Not to allow victims and perpetrators to occupy the same moral universe is to traffic in the dangerous idea that guilt and innocence are not the result of human behavior but exist somehow independent of what people do.

Let me close with an excerpt from my new book, Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt:

Many people still find abhorrent Hannah’s claim that Eichmann, the man, was no monster. Everyone knows murder is wrong; certainly, then, murdering millions without a guilty conscience must be the classic example of monstrous behavior. Or madness. Surely only a monster or a madman could commit such heinous deeds. And that’s an understandable reaction. Most of us hold fast to a well-guarded belief that rules and standards used to tell right from wrong, rules we assume to be universal, cannot be easily discarded. Not I, we believers in our own inherent goodness insist; I would never comply with such an order. But Hannah wouldn’t let anyone rest on such a convenient way to avoid having to think for herself.

“The trouble with Eichmann,” she wrote, “was precisely so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together, for it implied…that this new type of criminal…commits his crimes under circumstances that make it well-nigh impossible for him to know or to feel that he is doing wrong.[i]

The idea that “an average, ‘normal’ person, neither feeble-minded nor indoctrinated nor cynical, could be perfectly incapable of telling right from wrong” defies any ordinary understanding of good and evil. And yet, Hannah observed, “without much notice, all [these rules governing right and wrong] collapsed almost overnight…What happened? Did we finally awake from a dream?”[ii] How had it become so easy for so many to behave like Eichmann and participate in carrying out these atrocities?

Hannah explained it this way: the Nazi state had generated a “totality of…moral collapse…in respectable European society—not only in Germany but in almost all countries, not only among the persecutors but also among the victims.”[iii] And at that sentence, many people throw her book across the room in disgust, perhaps missing the other point she made: not everyone complied with the system.

But Hannah’s writing has made me wonder why we need to believe a solid wall separates the performers of horrible acts from the rest of us? And what holds that wall in place?

“When I think back to the last two decades since the end of the last war,” she wrote in the mid-1960s, “I have the feeling that this moral issue has lain dormant because it was concealed by something about which it is indeed much more difficult to speak and with which it is almost impossible to come to terms—the horror itself in its naked monstrosity.”[iv] Trying to think the unthinkable—the horror of state-ordered, socially coordinated manufacturing of corpses in the twentieth century, or of other genocides in previous centuries and in this one—can take one’s breath away. Not even time’s healing power seems to bring relief.

[T]his past has grown worse as the years have gone by so that we are sometimes tempted to think, this will never be over as long as we are not all dead…This past has turned out to be ‘unmastered’ by everybody, not only the German nation [v]

Yet Hannah insisted on confronting those concealed moral issues even though they looked like “side issues…compared with the horror.”[vi] She pushed past the speechless horror to grapple with the moral implications of the “ubiquitous complicity”[vii] surrounding the Holocaust. Because not grappling with those implications would allow Eichmann to gain what the monk Thomas Merton, deeply influenced by reading Eichmann in Jerusalem, would have considered a “posthumous long life,” making us all, like it or not, “vulnerable to complicity in deeds of destruction.”[viii]

[i] Ibid., 276.

[ii] “Some Questions of Moral Philosophy,” in RJ, 50.

[iii] EiJ, 125-6, emphasis added.

[iv] “Some Questions of Moral Philosophy,” in RJ, 50.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid., 56.

[vii] EiJ, 18.

[viii] Karl Plank, “Thomas Merton and Hannah Arendt: Contemplation after Eichmann,” The Merton Annual, 1990, vol. 3: 132.

November 12, 2013

“Diving for Pearls” Excerpt Published in Los Angeles Review of Books

“I use Grammarly’s free plagiarism checker because credit should be given where credit is due!”

The wait is over! Today, the Los Angeles Review of Books published the excerpt from my new book, Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt.

I am delighted to see my book’s cover on the front page of today’s edition of the LARB. I am hoping it will bring some advance notice to the book, which will have its official release date on November 25, 2013. That’s when you can order it from your independent bookseller or online, in either print or eBook version (available in all digital formats).

I am delighted to see my book’s cover on the front page of today’s edition of the LARB. I am hoping it will bring some advance notice to the book, which will have its official release date on November 25, 2013. That’s when you can order it from your independent bookseller or online, in either print or eBook version (available in all digital formats).

Readying the book for release has been a tedious process, but I can finally see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. I finalized all changes and uploaded the latest version to Ingram Spark a few days ago. By Friday, I will have the first print copies in my hand for one last look before pressing the “release” button, which sends the book out on all Ingram’s distribution channels.

In the course of events leading to release, I’ve discovered many useful writing resources, including Grammarly, which I mention at the beginning of this post. I’ve also learned a lot about advance marketing, reviews and other post-production activities essential to a book’s success. And I am interested in sharing what I learned with other writers who, like me, might decide to go the independent route. Watch soon for annoncements about solicitation of other books for Thinking Women Books’ list.

For instance, ForeWord Reviews is an excellent source for the latest news and reviews about books produced by independent presses. I’ve taken out an ad in their next issue, which hits Barnes and Noble bookstores and thousands of other venues in few weeks, just in time, I hope, for holiday ordering.

Here’s the ad, which includes pull quotes from advance reviews of the book.

I intend to enter the book in ForeWord’s book award competition. And I’m searching for other similar ways to showcase it. Any ideas you have? Send them along.

Meanwhile, thanks for following me on this journey.

November 1, 2013

Technical Obstacles, OR the Road to Launch is not Paved.

Spent the past week mastering the various templates and software programs needed to create an eBook file to upload at Ingram Spark, the POD service I am using for distribution. I learned more about WORD’s tricks for formatting than I ever knew before! And I also learned about Calibre, the software (freeware) that allows you to convert .docx files into EPUB, the format Ingram Spark requires for eBooks.

Spent the past week mastering the various templates and software programs needed to create an eBook file to upload at Ingram Spark, the POD service I am using for distribution. I learned more about WORD’s tricks for formatting than I ever knew before! And I also learned about Calibre, the software (freeware) that allows you to convert .docx files into EPUB, the format Ingram Spark requires for eBooks.

Despite having a very useful template for the creation of eBook formatting—thanks to Joel Friedlander’s Book Designing services–I still needed to make adjustments to get the eBook into the correct shape for it to convert properly into EPUB, the format that is now the digital publishing standard and one required on Ingram’s platform.

For example, you don’t want a Table of Contents to display page numbers for an eBook, so that requires changing it to an anchored list, with hyperlinks to a specific location in the document.

If this is more technical information than you understand or want to know, welcome to the challenges of independent publishing!

There are easier services than Ingram to use, but if you want your book to have wide distribution, you’ll choose to go the Ingram route. For instance, if you want a Shelf Awareness review of your book, they will accept independently published books but only if they are distributed by Ingram. And, they expect you to send them two proof copies of your book about two months in advance of publication—a deadline I am unlikely to make, depending on how quickly Ingram turns around my manuscript for proofing.

Still, it’s time for me to think forward to the launch of Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt. So, I have been reviewing web sites for advice on how to get the book into the hands of reviewers. Not an easy task either, since  many venues won’t touch independently published books. But Poets and Writers recently published a list of review sites, noting which will accept self-published material, which is a handy guide and starting place for consideration. Beyond this, many author blogs and author-related web sites provide information on blogging venues for reviews. Some of these will be useful for me, like Blog Critics, for which I have written reviews in the past. Others will be too general to be the audience I am trying to reach.

many venues won’t touch independently published books. But Poets and Writers recently published a list of review sites, noting which will accept self-published material, which is a handy guide and starting place for consideration. Beyond this, many author blogs and author-related web sites provide information on blogging venues for reviews. Some of these will be useful for me, like Blog Critics, for which I have written reviews in the past. Others will be too general to be the audience I am trying to reach.

I am also reaching out to you, dear readers, in the hopes you have connections to local, independent bookstores or community centers or schools willing to order my book and perhaps schedule me for a reading. I am already booked for Winthrop University in Rock Hill, South Carolina in March, thanks to my colleague Jennifer Disney, who invited me for Women’s History Month and related campus events. I’ll give a lecture based on the book and lead a writing workshop in her feminist theory class.

Any other suggestions you have, please send them along.

I am still hoping to launch in November, but it depends on production schedules.

October 24, 2013

Exciting News: An Excerpt of Diving for Pearls Soon to Appear in Print!

On November 12, 2013, The Los Angeles Review of Books will publish an excerpt from Diving for Pearls in its online journal. The day I received this news, I was so excited I read the email at least a dozen times. I have my editor, Louise Bernikow, to thank for encouraging me to find a journal that would publish a part of the book to generate advance interest. But the story of how I wound up in the LARB is interesting, and, obliquely, ties back to my book’s exploration of Arendt’s circle of friends.

On November 12, 2013, The Los Angeles Review of Books will publish an excerpt from Diving for Pearls in its online journal. The day I received this news, I was so excited I read the email at least a dozen times. I have my editor, Louise Bernikow, to thank for encouraging me to find a journal that would publish a part of the book to generate advance interest. But the story of how I wound up in the LARB is interesting, and, obliquely, ties back to my book’s exploration of Arendt’s circle of friends.

Hannah Arendt published in some of the leading New York literary journals, including the New York Review of Books, a journal I read for many years. When Elżbieta Ettinger’s book about Arendt’s affair with Martin Heidegger was published, articles about it appeared in the NYRB. So it surprised me that the NYRB never reviewed Deborah Lipstadt’s more recently published, and, in my view, equally controversial book, The Eichmann Trial, which came out in 2011. I was critical of Lipstadt’s perspective on Arendt, and took a leap, writing to Robert Silvers, the long-time publisher of NYRB, who also knew Arendt, asking why Lipstadt’s book hadn’t been reviewed in his magazine.

I was surprised when he wrote back asking if I had anything on Arendt I wanted him to read. I sent him a section of the book, and didn’t hear anything back. I let the matter drop and went back to my writing.

But while I was in the final stages of editing my manuscript I thought I might try some advance publicity and wrote to Silvers again, sending him an excerpt from Diving for Pearls. The excerpt was about Arendt’s female friendships and, in my email to Silvers, I suggested it might interest folks who had seen the new film by Margarethe von Trotta about Arendt, which included the first celluloid representation of Arendt’s friendship with Mary McCarthy. To my surprise again, Silvers replied, saying I have “many fresh things” to say about Arendt in my essay, which he hoped would be published. But they wouldn’t run it because they already had commissioned a piece on the von Trotta film from someone else, and would be doing another one on Arendt “for the while.” But he recommended some other places to send it, none of which worked because of their deadlines.

Then I remembered the Los Angeles Review of Books and thought that maybe my own New York bias hadn’t brought that new journal to mind before. And when I read the piece in The New Republic about editor Tom Lutz’s vision for the LARB compared with the NYRB, I felt a door might be opening.

So I sent a query to LARB and I got an email back in a couple of days saying they’d love to have it! A few weeks later, I received the edited version, along with a slated publication date: November 12. Moral of the story: keep sending your work out!

Besides being excited that my book would receive some advance press, having the publication date for my essay spurred me to finish all the pre-production details and ready the book for release by November 12.

I’ve spent the last two week since returning from a trip to the USA—where the government shutdown cancelled a meeting I was supposed to have with the NEH about my upcoming summer seminar on Arendt—preparing the manuscript. Today I readied it for uploading. The only thing left to do is upload the cover design, which Jeanette Vieira, my designer, is working on, and review the eProof that Ingram Spark will send me.

Then, the book will be available for sale. Once I get the green light from Ingram, it should be available for order from your local bookseller, or from Amazon or B&N. It will be available in print and eBook format and you can check Thinking Women Books, my publishing website, or email me through this website, for updates.

Thanks for your interest!

September 30, 2013

Visibility and Independent Publishing

I have reached that stage of my project when production details will now dominate as I get my new book ready for printing. In other words, I have switched to “publisher” mode. So, during the last two weeks, it’s been ironic for me to be thinking about production, marketing and otherwise figuring out how to make my writing visible while simultaneously following the fracas generated by Jonathan Franzen’s recent essay in The Guardian on “what’s wrong with the modern world.”

As I read the essay, I found myself agreeing and disagreeing with it at the same time. much like Michelle Goldberg’s response to it on The Daily Beast. In the essay, I heard echoes of Hannah Arendt’s worries about technology and the rise of “consumer society” and its corollary—the “society of laborers—whose effects she articulated in The Human Condition:

As I read the essay, I found myself agreeing and disagreeing with it at the same time. much like Michelle Goldberg’s response to it on The Daily Beast. In the essay, I heard echoes of Hannah Arendt’s worries about technology and the rise of “consumer society” and its corollary—the “society of laborers—whose effects she articulated in The Human Condition:

For a society of laborers, the world of machines has become a substitute for the real world, even though this pseudo world cannot fulfill the most important task of the human artifice, which is to offer mortals a dwelling place more permanent and more stable than themselves.

Franzen, too, expressed concern about the “dehumanization” of technology-dominated “technoconsumerism,” emphasizing the hidden power structures lying behind it. Using as a trope Karl Kraus, a turn of the nineteenth century Austrian satirist and trenchant critic of modernity, Franzen wrote:

With technoconsumerism, a humanist rhetoric of “empowerment” and “creativity” and “freedom” and “connection” and “democracy” abets the frank monopolism of the techno-titans; the new infernal machine seems increasingly to obey nothing but its own developmental logic, and it’s far more enslavingly addictive, and far more pandering to people’s worst impulses, than newspapers ever were [Kraus was a critic of the newspapers of his time].

Fair enough. It’s become increasingly difficult to see the monopolies of power that drive internet-democracy and clearly profit from it behind the rhetoric of “access = democracy” often associated with the internet. But Franzen wasn’t content simply to point to the Wizard behind the curtain—in this case, identifying two: Apple and Jeff Bezos—but went on to decry the “dumbing down” of writing and thinking by what he called “the internet’s accelerating pauperisation of freelance writers.” Too many people, of too little talent now have the tools to assault us with meaningless twatter, he argued. Among his examples were twitter and other social media.

Confessing to being disappointed that “a novelist who I believe ought to have known better, Salman Rushdie, succumbs to Twitter”—which, by the way, led Rushdie to respond to Franzen on Twitter: “Dear #Franzen: @MargaretAtwood @JoyceCarolOates @nycnovel @NathanEnglander @Shteyngart and I are fine with Twitter. Enjoy your ivory tower.”—Franzen lambasted the internet, social media, and, in particular, the impact of Amazon on publishing.

It’s important to my argument to quote Franzen at length here:

Amazon wants a world in which books are either self-published or published by Amazon itself, with readers dependent on Amazon reviews in choosing books, and with authors responsible for their own promotion. The work of yakkers and tweeters and braggers, and of people with the money to pay somebody to churn out hundreds of five-star reviews for them, will flourish in that world. But what happens to the people who became writers because yakking and tweeting and bragging felt to them like intolerably shallow forms of social engagement? What happens to the people who want to communicate in depth, individual to individual, in the quiet and permanence of the printed word, and who were shaped by their love of writers who wrote when publication still assured some kind of quality control and literary reputations were more than a matter of self-promotional decibel levels?

Amazon becomes, yet again, the bête noir of the coterie of truly serious writers, in which camp Franzen clearly positions himself, by making it harder for readers “amid all the noise and disappointing books and phony reviews” to find their way “to the work produced by the new generation of this kind of [serious] writer.” And not only are readers damaged; these non-shallow writers are being transformed into “the kind of prospectless workers whom [Amazon’s] contractors employ in its warehouses, labouring harder for less and less, with no job security, because the warehouses are situated in places where they’re the only business hiring.” (For the record, I didn’t think The Corrections deserved as much rave as much as everyone else lavished on it. But I intend to give his Freedom a chance to change my mind. And, yes, I am linking to his books because I think folks deserve to know about them.)

There’s no question that Amazon’s impact on publishing has been consequential in major ways, including lowering writer’s earnings. But what Franzen doesn’t address is the fact that the big publishing houses have contributed to this mess, making it more difficult for anyone without a “platform”—read notoriety of some kind, or an already significant record or the endorsement of folks like, well, Franzen—even to get the attention of the agents and without an agent most publishers won’t even take a look at a proposal.

Many really good writers, including some well-known literary writers, turn to indie-publishing as the only way to get their work into print, and also to have greater creative control. And many serious writers make every effort to have their work vetted before putting into the world. But when it goes into the world, sales notwithstanding, it will be judged.

The implication Franzen makes that there are among this group of self-published writers no serious writers “who want to communicate in depth, individual to individual, in the quiet and permanence of the printed word” is simply wrong, as other indie writers already have noted.

So, while I agree with Franzen’s wider worries about cultural malaise, I don’t think its roots can be placed entirely at the foot of Amazon or even of digital technologies. Even Franzen knows these are symptoms of a much, much deeper, systemic problem.

True, we need to feed ourselves with more “slow” forms of communication and defend the reverie necessary for thinking. And I believe good books—reading and thinking and talking about them—are one way to bring us back to this focus. But to trash those who have been excluded from the pantheon of writers blessed by publication by one of the “Big Six” is to pander to a kind of snobbery and self-importance that Franzen’s own analysis suggests he ought to know better than to embrace. At least a writer of his caliber should make more finely tuned distinctions.

And for those of us, including myself, who have taken the independent path, marketing, including a version of “self-promotion,” is essential to getting the word out about our books. But then, it’s important to Franzen too, whose article, by the way, was “tweeted” and circulated on Facebook, and otherwise shared more than 10,000 times.

In the next posting, I’ll have some suggestions for authors about how to increase the visibility of their work. By the way, this is no guarantee that anyone is going to read a book, much less a guarantee they will like it.

September 23, 2013

Getting Ready to Launch

After several weeks of time off for a much needed period of “rejuvenation” (translation: a two week 186-mile hike around the Pembrokeshire Coast of Wales!!), I returned to put the finishing touches on Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt. In hand were the final recommendations from my excellent editor, Louise Bernikow.

After several weeks of time off for a much needed period of “rejuvenation” (translation: a two week 186-mile hike around the Pembrokeshire Coast of Wales!!), I returned to put the finishing touches on Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt. In hand were the final recommendations from my excellent editor, Louise Bernikow.

Louise had read the entire manuscript and provided insight into how to strengthen the form and sharpen the writing. I edited the manuscript and then she read my updated version, offering key ways to put finishing touches on it, making the prose really “sing.” I credit Louise not only with making the book better, but also for keeping me focused and motivated. It’s not easy to return to a manuscript you thought you’d completed and find you have two major sections to rework. But, with the help of Louise’s “sharp pencil,” I found my way to completion!

Two things became obvious through my work with Louise: 1) in the words of Robert Lipsyte, (found on Jon Winokur’s website via his Twitter feed: @AdviceToWriters): “there’s too much satisfaction with the first draft, which is never as good as it could be.” I would say that can be true of the second, third, and fourth drafts too, because 2) using the services of a professional editor is essential to insuring your manuscript is as polished as it can be.

When searching for an editor, let me underscore how critical it is to find someone who “gets” your book. This means you want someone who not only has the technical skills of an editor, but who also knows how to “read like a writer,” to use Francine Prose’s lovely phrase (I recommend you read Prose’s book of the same title, by the way. It’s an excellent resource for writers.)

Having started a conversation with Louise through Facebook, where I had learned about her writing workshops, I continued my research into whether she was a “good fit” for my project by reading some of her writing (her Among Women, in particular, had a very similar feel in style and focus to what I was trying to do in Diving for Pearls). And I asked others who knew her and me for their opinions.

The collaboration between us worked like magic! Louise was thorough, unafraid to point out both the strengths and weaknesses of my prose, and absolutely “spot on,” as they say in this part of the world, with her insights. And, equally important, she was a reliable communicator; despite the time zone differences we were dealing with, I knew I could count on her to keep to schedule.

Now the book is ready to be “thrown into the world.” For the last week I have been working on the production side of the independent publishing process—getting my micro-publishing imprint’s web site operational (ThinkingWomenBooks), formatting the book for uploading to Lightning Source, finalizing the front cover design, and collecting “blurbs” for the back cover.

Micro-publishing? I chose that category for my press because it fits the mission of Thinking Women Books—“a small imprint with a big mission.” Micro-publishers aim for a niche audience with books that the “big” commercial presses aren’t likely to pick up. As Christina Katz put it, micro-publishing aims to “serve specific types of readers rather than focusing on pleasing the masses” and to cover topics traditional publishers might not want to cover. “Micro-publishing serves authors and readers across every increment of the content spectrum instead of merely serving readers of bestsellers.”

I’m in the process of soliciting writers and others with publishing experience to join the production team of Thinking Women Books. Once my own book is in final production, I will turn my attention to soliciting additional manuscripts.

August 28, 2013

Thinking Women Books

The votes are in! Decision time!

After reviewing folks’ comments, working with my designer, and weighing the options, I have selected the final front cover for my new book, Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt.

We followed carefully several design points, as well as looking at MANY covers of other books, as suggested, and here is the final design:

The back cover will wrap the “watery effects” around and also have space for “blurbs” as well as a small photo and author bio along with the necessary ISBN and scanning codes needed on all books.

I know several of you liked the younger Arendt, but this “older” Arendt is more iconic…including her smoking, which was signature for her. The “writing” that you see on the right part of the cover is actually a small excerpt of her notes from the Eichmann trial in her own hand.

I have completed all edits and sent the MS to my editor for one final review!

And I have completed the formatting of the book for a small paperback trim size of 5.25 x 8.00, which is a fairly standard size for books in my genre.

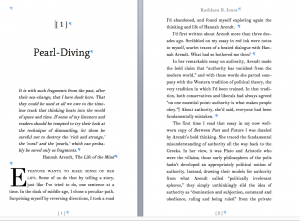

Here is a sample of what the first pages looks like:

Finally, after some back and forth with several folks, who responded to the blog and privately, I have named my new imprint:

Thinking Women Books

Having purchased the url for ThinkingWomenBooks.com I am now in the process of working with my web designer on getting that up and ready for launching the new press. The site is simply a placeholder for now, but stay tuned. There will be a call for book proposals to be reviewed and vetted, once I get the editorial board fully in place.

Mean time, I was delighted to hear from fellow writer, Mary Duncan, that she has launched a press of her own, Paris Writers Press, and has recently published the second edition of her Henry Miller is Under My Bed: People and Places on the Way to Paris.

Thanks to all of your for your suggestions and support and I look forward to your staying in touch as my adventure continues.

August 4, 2013

Design and Imprint

These past two weeks I have been working non-stop on the recommended edits for my manuscript, hoping to bring Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt into the world some time in the fall. As I near the end of this process, my attention turns toward the production angle of independent publishing, and has me thinking more and more about what to do to make my endeavor successful.

The first thing is tofinalize the design of my book. This includes both the cover and interior design.

COVER: I asked folks to respond to the cover options, and several subscribers did, but I am still looking for more feedback. (If you can look back to the previous post and see what you think of the options, sending me your votes—either as comments to the posting, or a separate message to me, I would appreciate it).

INTERIOR: Having selected a trim size (likely 5.25” x 8.00”), conforming to industry standards for memoir or literary non-fiction paperback titles, I’ll want to decide on fonts and layout. For that, I will likely turn to the services of a book designer, using one of the available templates to transform the WORD document of the manuscript into the required format for digital printing. Working with a designer will help insure layout and formatting are the most professional they can be.

DISTIBUTION: After much consideration, I’ve decided on Ingram’s Lightning Source for print-on-demand distribution. Lightning Source stood out for me as the best option for distribution, preferable to Amazon’s CreateSpace, because of the paper, trim size and cover design options (I wanted creme paper and a matte finish) Lightning Source offer. And if all this is sounding boringly technical to you, it’s just part of what you have to learn when you take on independent authorship. Which brings me to the main topic for today and something I’d like your input on.

A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME?

To distribute a title as an independent author I become a publisher, and that means creating my own imprint. So, I need a name for my press!

The first thing that came to mind, given my Arendt interests, is to call my imprint SELBSTDENKEN PRESS. The German word “selbstdenken” will be recognizeable to some of you; it translates into “thinking for oneself,” and was a watchword for Arendt’s conceptualization of thinking. Still, it might strike some folks as, well, a little odd. So for an alternative, what do you think about the inexact but more felicitous (to English speakers) THINKING PRESS?

Or, perhaps you have a name to propose? Comment or send me your suggestions as a message.

Another reason why the name of my imprint is important is my aim to publish more than one book, and not only my own titles!! YES! Since I am going to all this trouble gaining knowledge about publishing, I thought, why not offer a service to others, who might have books looking for presses?

A NEW IMPRINT WITH A FOCUS

The focus of my press will be on “historical and contemporary women’s stories with a personal is political slant,” which is the description I use on my Twitter account, but it also very much represents the focus of my own writing  over the last thirty years or so.

over the last thirty years or so.

This new imprint might appeal to a number of folks who have fiction or non-fiction works on this theme that they’d like to see in print, but who don’t want to take the time and energy—and face the often inevitable frustration—involved in searching for a traditional publisher, or even take on self-publishing. Some academic writers who have books that fall outside the narrower and narrower considerations of even academic presses might find my press an appealing option, assuming certain obstacles can be overcome.

More and more academics are looking for ways to get their creative research and other writing available and into print without having to deal with increasingly bottom-line decision-making being displayed by just about every publisher today. (See this recent article discussing the interest). For academics, and even some non-academic writers, having a proposed book vetted or peer reviewed in advance of publication is a necessity. Without that, an independently published book might not be considered part of one’s professional profile or C.V, even if it’s popular and sells well.

My press can fill this gap.

It will be a small enterprise of two to three books a year. To address the “peer review” issue, I plan to create a “board of advisors” made up of researchers and writers I know who would be willing to read proposed manuscripts and evaluate them for publication, much as many of us already do for traditional or university presses. (Any of my writer friends out there who want to volunteer, you are welcome to be considered!)

I’ll keep you posted on the press’s development.

AND SO…

Once again, please send ideas for PRESS NAME, advice on COVER DESIGN for my new book (see previous posting) and any other ideas/responses you may have in relation to my new project.

Enjoy the remaining months of summer!!

July 21, 2013

Collaboration in Friendship and Cover Design

I am a few days late with this week’s posting and for good reason. I got distracted into writing an essay about Hannah Arendt’s female friendships by a question my editor Louise Bernikow posed after reading part of my manuscript. Louise wanted to know more about Rosalie Colie, one of Arendt’s lesser known friends (lesser know than, say, Mary McCarthy), and Louise’s professor at Barnard in the late 1950s. I had a lot more material on Colie than I’d brought into my book so far and Louise’s comment sent me back to the drawing board or, rather, the computer screen. Within a week I’d written a piece entitled Passionate Thinking: Hannah Arendt’s known and less known female friends. My essay offers much-needed perspective on the complexity of Arendt’s friendships with women, and on female friendship more generally, providing a view not fully appreciated, even by recent commentators.

For instance, in the aftermath of the , which includes the first filmic representation of Arendt’s friendship with McCarthy, several reviewers have weighed in on whether the portrait of this iconic friendship in von Trotta’s film does justice to the kind of friendship that existed between these two intellectually self-confident women. Michelle Dean wrote of her disappointment in The New Yorker book blog.

Nearly every exchange between the two women is about men and love….Women talk about ideas among themselves all the time. It would be nice if the culture could catch up.

I don’t disagree with this assessment in general, but think there is much more to the story of Hannah Arendt’s friendships with women than has been explored so far. And that’s what I do in this new essay. I’d love to share it with you, but can’t post it on my blog until it’s gone through the review process at Guernica, “a magazine of art and politics,” where I sent it for publication consideration. So, stay tuned.

Apart from that productive distraction, while waiting for Louise’s final comments, which will take me back to my manuscript for edits, I’ve been busy designing my book.

Jeanette Vieira, my graphic designer, sent me new ideas for the cover. We’d been playing around with the idea of creating the cover as a visual allusion to the most recent edition of Arendt’s biography of Rahel Varnhagen. But that idea was hampering Jeanette’s creativity. So, at the brilliant suggestion of someone else, I began to think about images more directly related to my title—Diving for Pearls—and encouraged Jeanette to experiment with them, allowing her visual associations to wander into watery depths.

It turns out it was exactly what Jeanette needed to allow her imagination to soar (or dive, in this case)! She wrote me an enthusiastic email:

The underwater visual provides so much opportunity to illustrate the deeper meaning of the book…Seems there is psychology of the underwater realm that fits well here. I’m much more inclined to, and inspired by this direction after reading the text.

And then she asked me to associate to the places and emotions that emerged for me through the writing. This kind of collaborative process, which I’ve experienced before in my work in theater, underscores why the self-publishing route, though time-consuming, can result in so much unanticipated and exciting learning for anyone who takes the leap.

Last week Jeanette sent me four samples and, with her permission, I’m sharing them with you now and invite you to comment on which one you think most effective. (I have my own favorite, but really want to hear your responses. Click on the pictures and you’ll be able to view them separately in larger format).

As you will note, the differences between the two basic designs are subtle shifts of color and resolution. I’d also like to hear your suggestions on font/typographic design.

Cover Design 1

Cover Design 2

Cover Design 3

Cover Design 4

I want to avoid the pitfall that Tim Kreider described in a recent posting on the New Yorker’s book blog. Designs are becoming bland and formulaic, he wrote, explaining how and why “most contemporary books all look disturbingly the same, as if inbred.” It’s because of what he called the two rules of book cover design:

The main principles of design—in books, appliances, cars, clothing, everything—1. Your product must be bold and eye-catching and conspicuously different from everyone else’s, but 2. Not too much!

I don’t want my book to succumb to this trend. In fact, most book design blogs that I’ve been reading emphasize the importance of the cover to help make a book stand out from the crowd. So, even though I know most readers will come to my book based on recommendations from friends or fellow readers and writers, I still want it to have a distinctive aesthetic; I want my book to become a “conspicuous exception.”

We’ll continue to experiment until we get exactly the right look to grab a reader’s attention and also communicate what the book is about.

I’m looking forward to your comments and suggestions!