Andy McPhee's Blog, page 2

April 26, 2023

When Writers Can’t Write

Lots of things going on in the McPhee household lately, so much so that I haven’t been able to write for a few months, and I absolutely hate it.

I feel unmoored on a lake during a storm. I can see land all around me, but I’ll be damned if I can get there. I want to, and I’ve been able to do a bit of revision on existing chapters now and then, but to write new stuff? Cain’t get there from here.

And I’ll probably remain unmoored for the next few weeks, dang it. Oh, well, such is life.

So, how are you-all doing?

April 4, 2023

One Woman’s Story of the Deadly Smog

When you write a true story of an event, you always gather information you’d like to include in the final version but just can’t. Such was the case with one of my interview subjects for my book, Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town. I interviewed Donora native Edie Jericho (above) about her recollections of the smog. I included information she provided about her neighbor Emma Hobbs (chapter 24), but couldn’t fit other recollections into the text.

Let’s look at what else she told me about that fatal Halloween weekend in 1948.

I got up Friday morning. It was the first day of the smog [it was officially the fourth day] and it was foggy out, but in October and November it usually is foggy along the river. My mother got us ready, and we walked to school. My oldest sister was going to tenth grade and she was going to Rostraver, which meant she had to catch a bus, and she went down to the bus stop, but the bus never came.

I would have been in seventh grade, eighth grade. We walked down to the school in Webster, which is no longer there. And [when we] walked home for lunch at 12 o’clock, it was still foggy because usually by then the fog would have burnt off.

We got our Halloween costumes on, went back to the school, and we had a Halloween parade. I mean, they did that every year, that was part of it. Kids walked around with their Halloween costumes on, and you got voted on by the teachers. Then [the fog] was getting really bad, and they noticed you couldn’t see each other. It was hard to see, so it was an early dismissal, and I went home.

When you were twelve years old back then, your mother would never worry if you and maybe three or four other girls would walk across the [Donora-Webster] bridge to go see a parade, because nobody ever bothered you. It was the kind of a town where you never locked your doors. It was just like everybody trusted everybody.

We walked the bridge and watched the Halloween parade, what we could see of it. You could see the ones that were closest to you, but you couldn’t really see across the street and tell who was on the other side of the street.

When we went home I told my mother that I was going to go off for a while trick-or-treating. And my mother said to me, “Oh, no you’re not.” She says, “it’s bad outside.” And I said to her, “Oh no, I have to go trick-or-treating.” There was this one lady in Webster, her name was Olive Lorenzo, and she made the most delicious candy apples you ate in your life. I said, “I’m going to Olive’s because Olive made candy apples.”

We went out Halloweening for a while and then we went back home. I don’t remember too much about the next day, but I know my dad went to work. He had a wet handkerchief pad across his face.

“Well, Sunday, my mother’s next-door neighbor come running over to the house and he hollered, “Miss Annie! Miss Annie!” My mother says, “What’s the matter?” He says, “Hurry up, something’s really wrong with my Emma.”

Edie Jericho, May 15, 2019

Edie’s mother was too late. Her dear friend, Emma Hobbs, had become the smog’s eighth victim.

Purchase the book at UPitt Press, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.

March 11, 2023

What That “It’s My New Book” Feel Feels Like

When I practiced as an RN many years ago, I had a chance to play a direct role in saving the life of a few people. It’s an incredible feeling, a mix of pride from a job well-done, humility from the fragility of life, and an inner warmth that fuels the self. It’s a feeling that never goes away, that becomes part of your very being, and that you’re grateful every day to have felt it.

I’m not sure I’ve ever felt anything like that since I left nursing, but I have to tell you, holding a book you’ve written and that just arrived from the printer comes pretty, pretty, pretty close.

I recently received a copy of my book, Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town, in the mail, and I love it. The folks at the University of Pittsburgh Press did an outstanding job on it, and I am hugely appreciative of their work. I love the soft, almost furry feel of the cover. I love the heft of it, the zffffffttt of the pages as I riffle through them. I worked hard on the book and, even with the flaws—Damn those flaws!—I just love looking at it and feeling it.

No, it’s not the same as saving a life, but it’ll do for now.

October 4, 2022

Irish Surgeon Becomes America’s Leading Body Snatcher

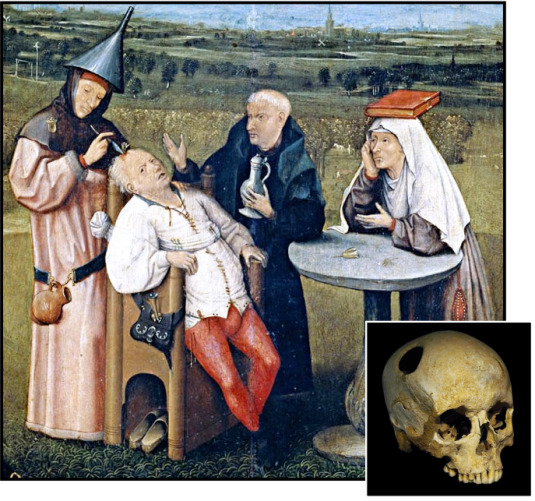

Detail from The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, by Hieronymus Bosch, depicting the medical procedure of drilling a hole in a person’s skull to release fluid and other matter. Inset shows a trepanned skull.

Detail from The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, by Hieronymus Bosch, depicting the medical procedure of drilling a hole in a person’s skull to release fluid and other matter. Inset shows a trepanned skull.The story above might sound like fiction, but it actually happened. The surgeon, Samuel Clossy, would go on to become a leading surgeon in New York City.

Born in Dublin in 1724, Clossy emigrated to New York in 1763 and became two years later the first professor of anatomy at King’s College, now Columbia University. He had written a classic anatomy text while in Ireland called Observations on some of the Diseases of the Parts of the Human Body: Chiefly taken from the Dissections of Morbid Bodies.

Morbid bodies indeed.

And where did those morbid bodies come from, oh, great Dr. Clossy? Why, from recently deceased individuals whose remains were unceremoniously and illegally dug from their graves and transported at night, undercover, to your anatomy lab.

That Little Ol’ Body Snatcher, Me Samuel Clossy

Samuel ClossyClossy had been using bodies snatched from graves throughout his schooling in Scotland and his medical practice in Ireland. That’s how physicians at the time secured bodies for teaching anatomy, by stealing bodies themselves or having others steal them. Clossy almost certainly stole bodies himself as a student and later most likely hired others to do the dirty work.

Clossy specialized in gynecology and, not long after he arrived in New York, gave his first anatomy lectures and dissections. The first two dissections were performed on females, one Black and one White. Clossy had aimed to do a third dissection but ran into, um, an issue. “We could not venture to meddle with a white subject,” he said, “and a black or Mulatto I could not procure.”

Most of the bodies obtained for dissection in New York City during and after the Revolutionary War came from either the potter’s field or the Negroes Burial Ground. The two graveyards were opposite one another on Chambers Street near Broadway, within three blocks of New York Hospital. How handy.

Clossy Came, Clossy WentClossy didn’t stay long in New York after the war. He was a confirmed Loyalist and didn’t back down from his beliefs when the British lost.

Francis R. Packard wrote about Clossy in his voluminous History of Medicine in the United States, published in 1901. Packard was a highly esteemed Philadelphia oncologist who had studied under one of the most venerated physicians in history, Sir William Osler. Packard said that Clossy’s “political opinions rendered him obnoxious to the patriots, and he returned to his native land after a few years’ sojourn in this country.”

Clossy would not live to witness the anger and violence of the Doctor’s Riot of 1788, a riot prompted by the practice of body snatching. Clossy’s declining health and continued Loyalist leanings prompted him to return to Dublin, where he died at about age 62 on August 22, 1786.

August 6, 2022

Feuding Founders of First US Medical School

The early years of the nation’s first medical school did not go smoothly. Not at all.

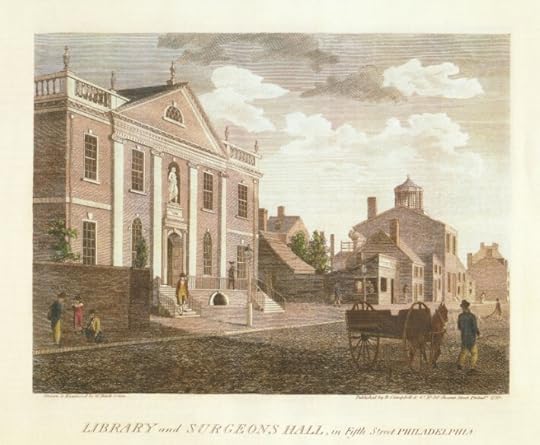

The medical school, now the Perelman School of Medicine, was founded under the auspices of the College of Philadelphia, which would eventually become the University of Pennsylvania. The first class of medical students started classes on Thursday, November, 14, 1765, at Surgeons Hall, now called Library Hall, across the street from Independence Hall. At first the school consisted of sixty lectures on human anatomy as well as a course in the “theory and practice of physik,” a now archaic term meaning “the science of the principles operative in organic nature.”

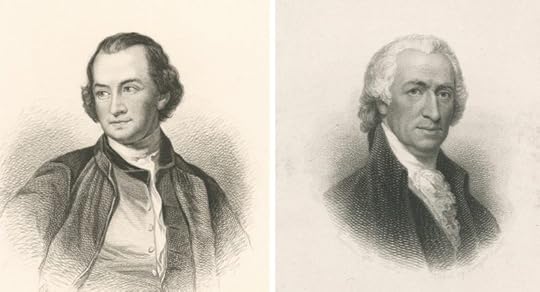

The medical school was founded by two men, William Shippen Jr. and John Morgan, though Morgan is generally credited with being the primary founder. Theirs was a complicated history fraught with anger, resentment, and betrayal. Both grew up in Philadelphia, and both received their medical education at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, where a great many US physicians went to medical school in in the late 1700s and into the 1800s. Shippen attended Edinburgh a few years before Morgan and returned to Philadelphia in 1762, three years before Morgan returned.

Morgan and Shippen knew each other in school and had discussed the need for a medical school in the United States, though they differed in what that school should look like. Morgan envisioned a school similar to the University of Edinburgh‘s medical school, one associated with an institution of higher learning. Shippen, on the other hand, envisioned a medical school more like those in London, one associated with hospitals, not colleges or universities.

When Shippen returned to Philadelphia he began offering lectures on anatomy, surgery, and midwifery on his own. His discussions with Morgan led him to believe that after Morgan graduated and returned to Philadelphia, they would both establish a medical school in the city. “I should long since have sought the patronage of the Trustees of the College [of Philadelphia],” wrote Shippen in a letter to the trustees, “but waited to be joined by Dr. Morgan, to whom I first communicated my plan in England, and who promised to unite with me in every scheme we might think necessary for the execution of so important a point.”

John Morgan (left) and William Shippen Jr.Morgan Strikes First

John Morgan (left) and William Shippen Jr.Morgan Strikes FirstMorgan, however, had other ideas. When he returned to Philadelphia from Edinburgh in 1765, he immediately proposed to start a medical school at the College of Philadelphia. College trustees loved the idea and appointed Morgan as chair of Theory and Practice of Physik. Morgan set up classes on anatomy and physik, but failed to do so for surgery. “Morgan had disparaged surgery as an unintellectual, mechanical art, repugnant to sensitive men,” wrote George W. Corner in his book Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. “He was apparently willing to leave it to be taught by apprenticeship alone, for he proposed no chair of surgery in the school.”

Guess who was a surgeon? William Shippen.

Shippen felt betrayed, though he accepted Morgan’s offer to become professor of anatomy and surgery. Even so, Morgan’s self-appointment as chair constituted a huge affront to the elder physician’s ego. From that point forward, the two men feuded frequently, their hostility toward each other growing throughout their lives. For instance, during the Revolutionary War Morgan was named director general and chief physician of the Continental Army. Morgan struggled in the position and was fired two years later.

Guess who took his place? William Shippen, an appointment that infuriated Morgan.

Shippen hardly fared better, though. He was accused of falsifying mortality reports, neglect of duty, and misuse of hospital funds and supplies and was court-martialed, though later in the 1780 trial he was declared innocent of all charges. He was subsequently given back his position as the army’s medical director, serving for only a short time before resigning his commission.

Enemies ‘Til the EndWhen College of Philadelphia was renamed University of the State of Pennsylvania in 1780, Shippen was granted a full professorship of anatomy and surgery. Over his career he pioneered midwifery as a separate course in medicine and proved instrumental in the development of medical education in America, helping to establish the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, a society established “to advance the science of medicine and to thereby lessen human misery.” The society continues to operate the famed Mütter Museum.

Morgan likewise enjoyed an outstanding career in medicine. He helped found the American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin to promote “useful knowledge.” Morgan was one of the first members of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and was active in the Anglican Christ Church at Second and Church Streets.

Morgan eventually faded from practicing as a professor and died of influenza on October 15, 1789. He was 53. Shippen lived considerably longer. He died from an anthrax infection on July 11, 1808, at his home in Germantown, a quaint Philadelphia neighborhood . Shippen was 71.

The two unreservedly brilliant physicians never settled their grievances and died as archenemies.

June 19, 2022

Incident at the Marshall House

Marshall House in 1860s

Marshall House in 1860sHe was either a traitorous villain or a martyr for the cause, depending on which side of the Mason-Dixon line your ancestors lived.

It was 1860, and a man named James W. Jackson, a rabid secessionist, was managing the Marshall House, a hotel that once stood on the corner of King and Pitt Streets in Alexandria, Virginia. Jackson found it fit to hang an enormous woolen Confederate flag—14×24 feet—from a 40-foot mast at the top of the hotel and installed a non-working cannon behind the hotel’s tavern, aimed at the hotel’s front door. He then told people that the flag would be removed only over his dead body.

In late May the following year, the first year of the Civil War, Jackson was granted his wish. The 11th New York Infantry, better known as the New York Fire Zouaves, had just swept into Alexandria. The unit couldn’t miss the gigantic flag of their enemy atop a hotel. The unit’s commander was Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, who had known President Lincoln back when he was just a gangly lawyer in Springfield, Illinois. Ellsworth was not going to allow that flag to fly.

Elmer Ellsworth

Elmer EllsworthHe and another Union soldier, Francis E. Brownell, climbed to the roof and removed the flag. When they came back down the stairs, an enraged Jackson met them with a shotgun. Jackson fired at Ellsworth, striking him in the chest and killing him. Brownell fired his already-loaded musket at Jackson, striking him in the face. He then rammed his bayonet into Jackson’s chest. In a confrontation that took just a few seconds, two men lay dead on the stairs.

Thomas Holmes, a New York coroner who had been embalming bodies and teaching others the trade for several years, heard about the incident and discovered that Ellsworth was a friend of Lincoln. He visited the president in Washington and offered to embalm Ellsworth for free. Lincoln accepted.

Holmes used a French embalming technique in which he injected an artery in the neck or wrist with a mixture of alcohol, arsenic, creosote, mercuric chlorides, and turpentine. The embalming preserved the body long enough for it to lie in state for several days before being buried in Mechanicsville, New York, Ellsworth’s hometown.

Michael Strahan, in a post for Lost New England, wrote, “This incident at the Marshall House would mark the first Union officer to die in the Civil War. Ellsworth’s body would be sent to the White House for public mourning, while Jackson’s actions made Southerners view him as their first martyr of the war.”

Not only was Ellsworth the first Union officer killed in the war, but he was also the first casualty to be embalmed. Coroner Holmes would go on to embalm an estimated 4,000 men, mostly officers, at a fee of $100 per body. A total of approximately 40,000 embalmings were carried out during the war, out of about 750,000 killed on each side.

A newspaper at the time wrote this about Thomas Holmes:

He expresses the hope that if employed upon any one of celebrity, it will be no less a personage than Jeff. Davis. He would take especial pleasure in injecting a very large amount of embalming fluid in his veins, and rendering him as rigid as a marble statue.

Embalming changed forever when formaldehyde came into funereal use in the 1890s, but of course that’s a story for another time.

May 2, 2022

The Most Important Half-Finished Painting in American History

Hanging in a prominent position in the Winterthur Museum in Pennsbury Township, Delaware, is a painting one might think shouldn’t be there at all. It might, to the casual visitor, look like it belongs back in the artist’s studio to be completed. Half of it is blank, after all.

The painting is, however, as complete as it is ever going to be. Visitors gazing at the painting today might visualize in it an America of the late 1700s, an America in the nascent stages of its nationhood, an infant that can finally stand on its own but finds walking slow, cumbersome, and fraught with the danger of failing.

The painting is officially called the American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Negotiations with Great Britain, but is more commonly known as the Treaty of Paris. It depicts the signing of the 1783 treaty to end the Revolutionary War and was painted by Pennsylvania-born Benjamin West.

The Death of Socrates, by Benjamin West

The Death of Socrates, by Benjamin WestWest, born October 10, 1738, began painting as a child. He lived in a small, two-story brick house in Springfield that still stands today, at the corner of Goshen Road and Route 252 in Newtown Square. West’s talent proved so substantial that he began during his teenage years to receive commissions to paint portraits. He painted his first historical piece, The Death of Socrates, a detailed, consequential painting (right), when he was just eighteen.

At age twenty-two West found himself in London, where his career flourished. His brilliant work eventually caught the attention of King George III, and he was given the title of “Historical Painter to the King.” West delivered sixty paintings to the King between 1768 and 1801.

It was during that period that King George III was rather heavily engaged in a war with his colonists. After Britain’s surrender at Yorktown in 1781, and after two years of negotiations between the two nations, the king’s historical painter found himself in a perfect position, as an American expatriate living in London, to paint a portrait of the signing of the treaty ending the war.

Benjamin West, Self-Portrait, 1819, six months before his death*

Benjamin West, Self-Portrait, 1819, six months before his death* West decided he would place American delegates at one end of a table and British delegates at the other. He would later donate the piece to Congress. “This work I mean to do at my own expense,” West explained, “and to employ the first engravers in Europe to carry them into execution, not having the least doubt as the subject has engaged all the powers of Europe, all will be interested in seeing the event so portraid.”

The final painting would include each nation’s negotiators — John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and Henry Laurens for the Americans, and a Scottish merchant named Richard Oswald for the British. The painting also would include the secretaries for both delegations, Franklin’s grandson William Temple Franklin and Oswald’s secretary, Caleb Whitefoord.

Oswald, however, had been forced to resign his position a few weeks prior and was no longer in Paris. Without having Oswald available to sit for him, West was at a loss. He eventually chose to set the work aside and go on with his life.

Benjamin West’s unfinished painting of the Treaty of Paris. From left: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.

Benjamin West’s unfinished painting of the Treaty of Paris. From left: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.To look at the painting now is to visualize not just the split between America and Great Britain, but to consider the tenuousness of a brand-new nation. There were genuine leaders aplenty after the war, but there was no national constitution, nor would there be for six more years.

Nothing in the new nation seemed finished. With a population of fewer than four million after the war, America entered a period of social, economic, and political turmoil distinct from the war, yet equally crucial to the country’s survival. The nation began shedding its Britishness and forging an American persona, a process that would take generations.

If ever a piece of art captured the incompleteness, the fragility, the very essence of post-revolutionary America, Benjamin West’s Treaty of Paris was surely it.

* “Six months before he died, West looked unflinchingly into the mirror to paint his self-portrait. He holds a drawing pencil and wears a painter’s robe and beaver hat, which identify him as a founder and president of the Royal Academy of Art. The light is strongest on his face and hands, but the rest of the picture falls into shadow, as if he foresaw his own end. West was official painter to the King of England and the first American artist to gain an international reputation. His example led generations of American artists to measure their art and professional identities by European standards.” — Exhibition Label, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2006April 9, 2022

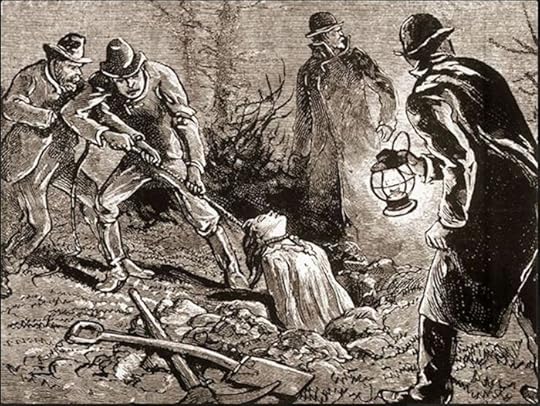

The Business of Body Snatching

Body snatching was big business in the late 1700s and all through the 1800s, when medical schools couldn’t obtain enough bodies legally to dissect in anatomy labs. So along came body snatchers. Grave robbers. Sack ’em up men. The more elegant name for these ruffians was “resurrectionist.” They were crafty fellows, that’s for sure.

How Did They Do It?They would enter a cemetery at night, dig up a freshly buried body, wrap it up, load it on a carriage of some sort, and haul it to an anatomy lab or the home of a physician. They would be paid for their product, and then disappear into the darkness.

Body snatching was not for the weak of heart. First, the ground above the body’s head and shoulders would be dug out. The coffin itself wasn’t dug up; snatchers were interested in leaving the ground as undisturbed as possible.

So they dug down to the head end of the coffin and broke open just that end of the coffin lid so that the head and shoulders were uncovered. Then they would loop a rope or, sometimes, a hook around the head or shoulders, and drag the body out.

They would then try to return the gravesite to its original condition, to avoid suspicion.

If anyone discovered a missing body, trouble could ensue, depending on whether the deceased was White and considered a respectable member of society. The bodies of homeless, poor, indigent, or Black people were pretty much fair game. Said one New Yorker of the time, “The only subjects procured for dissection are the productions of Africa …” and executed criminals, “and if those characters are the only subjects of dissection, surely no person can object.”

Ruh-Roh John Scott Harrison

John Scott HarrisonLet a “respectable” White body be stolen, though, as happened in April 1788 at New York Hospital, and all hell could break loose. A three-day riot arose that year when medical students dissected the body of a woman recently buried in a church cemetery. Ten or more people were killed in what came to be known as the Doctor’s Riot of 1788. Baltimore experienced a similar uprising in in 1807, though no deaths were reported.

Relatives of presidents were not immune from having their body snatched. In 1878 the body of William Henry Harrison’s son John, a congressman himself, turned up in a pickling tank at Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College. His body had been stolen from its grave and then dissected by medical students.

I’ll have more about body snatching, medical dissection, anatomy laws, and the Doctor’s Riot of 1788 in the weeks and months to come.

April 6, 2022

A Tale of Two Henrys

St. George’s Hospital stood stately and regal in a corner of London’s Hyde Park, its raised colonnaded entrance beckoning visitors inside its healing walls. Now a posh hotel called The Lanesborough (below), St. George’s in 1858 birthed a worldwide bestseller from its dissection and post-mortem rooms. The book would furnish students for a dozen decades to come with critical information they needed to practice medicine.

The Lanesborough, formerly St. George’s Hospital

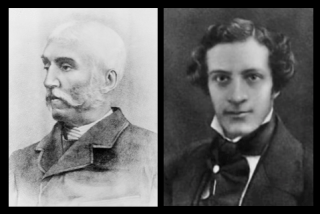

The Lanesborough, formerly St. George’s Hospital Henry Carter (left) and Henry Gray

Henry Carter (left) and Henry GrayThe book was Gray’s Anatomy: Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical, known as simply Gray’s. The men who wrote and illustrated the book were both named Henry — Henry Gray, who wrote all the words, and Henry Vandyke Carter, who created all the illustrations.

In 1855 Gray had an idea for a detailed anatomy book for students. He approached Carter, who was a talented artist and also a physician, about joining forces to publish such a book. Carter considered the idea interesting, but he wasn’t sure it could work. He wrote in his diary, “Little to record. Gray made proposal to assist by drawings in bringing out a Manual for students: a good idea but did not come to any plan … too exacting.”

Three years later — an incredibly short period of time to produce and publish such a book — the first copies of Gray’s hit bookstores. Seven hundred eighty-two pages strong, the tome promptly became a bestseller throughout Europe. It was published a year later by Blanchard and Lea, a prestigious Philadelphia publishing house, and became a bestseller in the United States as well.

The book is now in its 42nd edition, and its growth and popularity has been remarkable. From a size of 6×9 to 9×12, from 782 pages to 1,606, from just over three pounds to more than ten, and from 1£ 8 pence (about $5 in 1860)[2] to $230 in 2022, the book remains a foundational text for healthcare students of all kinds.

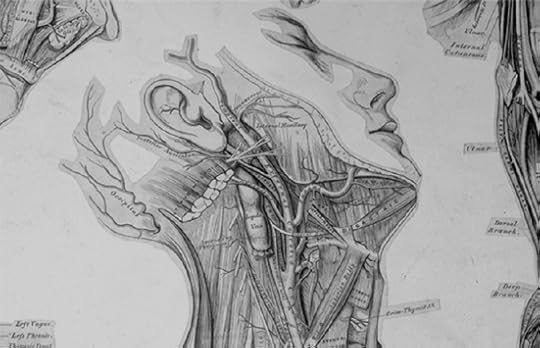

Henry Gray’s detailed, voluminous descriptions provided the depth and clarity of information medical students needed. Carter’s 363 finely detailed illustrations, originally drawn on paper but later drawn on woodblock, gave students clear and compelling visual references to the body’s inner anatomy. Even today anyone with even a passing knowledge of Gray’s could probably identify an H. V. Carter image (below) with just a glance.

Upper vascular system

Upper vascular systemengraving from the first edition of

Gray’s Anatomy

Ruth Richardson, in her superb work, The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy, captures the value of Carter’s images this way.

One of the most distinctive qualities in Carter’s illustrations is that they are a look and say all on their own. They are definitely visual, but also verbal. When you open an illustrated page in Gray’s, especially when the image is a goodly size, it’s hard to look first at the text. The eye is drawn to the illustrations, with their physical demonstration of what Gray’s words endeavour to describe in the adjacent letterpress. Carter’s illustrations lay out the body, showing behind, above, below, concave, smooth, passes through, arises from, and lies along; and at the same time telling trapezius, clavicle, sternum, hyoid, sterno-thyroid. And as you look, you’re already down deep in the structures, discerning their names and shapes for yourself as you go. Even without being conscious of thinking, the eye takes in the structure and its name at the same time.

Carter went on to teach anatomy in Bombay, India, where he had lived since the book published. He returned to England in 1888, married for a second time (his first wife having died), contracted tuberculosis and died in 1897. He was sixty-five.

Gray’s life proved tragic. Three years after Gray’s was published, Gray’s nephew, Charles, contracted the virus that causes smallpox. In treating the lad, Gray himself developed the disease. Charles survived, his uncle did not. Gray died in 1861 at age thirty-four.

The book the two Henrys made continues to sell around the world, cementing the men’s legacy for generations to come.