Paul Bishop's Blog, page 44

August 11, 2015

THE DELIGHTS OF MURDER AND MISS FISHER

Few things bring more joy to a longtime voracious reader than discovering a delightful new (to them) fictional character in a well written novel by an established author who has hitherto slipped below their book gobbling radar. What makes the find even better is if the book turns out to be the first in a series with nineteen more tomes to read!

Few things bring more joy to a longtime voracious reader than discovering a delightful new (to them) fictional character in a well written novel by an established author who has hitherto slipped below their book gobbling radar. What makes the find even better is if the book turns out to be the first in a series with nineteen more tomes to read!These rare discoveries can come in several ways…a recommendation from a friend (hardly ever suits your taste), a review in an obscure publication (hit and miss), surfing through Amazon listings (sometimes), or even stumbling across one in a used bookstore (the most rewarding).

None of the above, however, apply to the impetus that made me delve into the first of Kerry Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher mysteries. In this case, I had been hearing distant raves about Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, an Australian television series unavailable via American television or cable networks.

These rumors of the special delights presented by Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries continued to circulate, while I waited patiently for the series to turn up on PBS’ Mystery, BBC America, or possibly A/E – who I happened to be boycotting ever since they cancelled Longmire. The rumors spoke of gorgeously produced, well written, episodes starring actress Essie Davis, who it was said couldn’t be a better match for the iconoclastic feminist sleuth Phryne Fisher – a lady detective operating in 1920’s Melbourne. I was more and more intrigued.

An online search turned up information and photos of the series. It looked and sounded great – but still no planned US release. I saw Acorn TV (which carries a lot of British and European shows) was streaming an episode, but you could only see five minutes worth without signing up for a monthly subscription fee. I was still intrigued, but not monthly subscription fee intrigued.

Finally, the inevitable DVD release made its debut on Amazon. I quickly snaffled it up and found myself hooked from the very first episode. The show’s tag line sum it up: Who says crime doesn’t play?

What a delight – frothy but never silly, tart but never pretentious, with smart dialogue, great character actors in supporting roles, and plots that hold together without being too simple or sordid.

The production was as advertised: The sets, the cars, the planes, and – I’m not to macho to mention – the costumes. Plus, Essie Davis was a revelation. So too – but to a lesser degree perhaps – was Nathan Page who portrays Detective Inspector Jack Robinson, Miss Fisher’s long suffering, efficient, and smitten police foil.

The relationship between these two characters is at the heart of the show – driving fans into a frenzy of support when the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Company) network made noises about cancelling the show after two seasons, for all the nonsensical reasons networks cancel popular shows (refer to A/E and Longmire above). A third season was eventually commissioned and Miss Fisher carries on toward 1930.

As season three of Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries premiered in Australia, Phryne Fisher fever seemed to become contagious Down Under. There were costume exhibits, themed luncheons, and premiere parties. All of which I totally understood and would have enjoyed participate in had I been in Melborne.

All of this is a very longwinded journey to get to the point that the television show was so good, I couldn’t resist at least trying the first book in the series – which really wasn’t even close to the normal genre sweet spot of my reading habits. I wa wary as I know, from prior experiences, if you love a book then a television series or movie based on it most often disappoints. Conversely, if you love a movie or television series, the books they are based on usually pale by comparison. In the case of Miss Fisher, the television series had really caught my imagination, and I didn’t think there was a chance the books would live up to my expectations. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

At this point, I’ve finished the third Phryne Fisher book from author Kerry Greenwood and have listen to the excellent audio version of two others. The television series is one of the best book to screen translations I’ve ever come across. Greenwood’s writing is assured and has the light yet substantial touches the television series has captured so well. I’m hooked and am already freaking out because I only have fifteen more book titles, and eight shows from season three of the television series, to go.

Reading and viewing experiences like this are like shooting stars – brilliant, amazing, and gone too fast. When they've disappeared, it’s back on the hunt for more elusive treasures.

DO YOURSELF A FAVOR AND CLICK HERE TO VISIT KERRY GREENWOOD’S PHRYNE FISHER WEBSITE

CLICK HERE TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE TELEVISION SERIES

Published on August 11, 2015 06:54

August 10, 2015

THE DELIGHTS OF MURDER AND MISS FISHER

Few things bring more joy to a longtime voracious reader than discovering a delightful new fictional character in a well written novel by an established author who has hitherto slipped below their book gobbling radar. What makes the find even better is if the book turns out to be the first in a series with nineteen more tomes to read!

Few things bring more joy to a longtime voracious reader than discovering a delightful new fictional character in a well written novel by an established author who has hitherto slipped below their book gobbling radar. What makes the find even better is if the book turns out to be the first in a series with nineteen more tomes to read!These rare discoveries can come in several ways…a recommendation from a friend (hardly ever suits your taste), a review in an obscure publication (hit and miss), surfing through Amazon listings (sometimes), or even stumbling across one in a used bookstore (the most rewarding).

None of the above, however, apply to the impetus that made me delve into the first of Kerry Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher mysteries. In this case, I had been hearing distant raves about Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, an Australian television series unavailable via American television or cable networks.

These rumors of the special delights presented by Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries continued to circulate, while I waited patiently for the series to turn up on PBS’ Mystery, BBC America, or possibly A/E – who I happened to be boycotting ever since they cancelled Longmire. The rumors spoke of gorgeously produced, well written, episodes starring actress Essie Davis, who it was said couldn’t be a better match for the iconoclastic feminist sleuth Phryne Fisher – a lady detective operating in 1920’s Melbourne. I was more and more intrigued.

An online search turned up information and photos of the series. It looked and sounded great – but still no planned US release. I saw Acorn TV (which carries a lot of British and European shows) was streaming an episode, but you could only see five minutes worth without signing up for a monthly subscription fee. I was still intrigued, but not monthly subscription fee intrigued.

Finally, the inevitable DVD release made its debut on Amazon. I quickly snaffled it up and found myself hooked from the very first episode. The show’s tag line sum it up: Who says crime doesn’t play?

What a delight – frothy but never silly, tart but never pretentious, with smart dialogue, great character actors in supporting roles, and plots that hold together without being too simple or sordid.

The production was as advertised: The sets, the cars, the planes, and – I’m not to macho to mention – the costumes. Plus, Essie Davis was a revelation. So too – but to a lesser degree perhaps – was Nathan Page who portrays Detective Inspector Jack Robinson, Miss Fisher’s long suffering, efficient, and smitten police foil.

The relationship between these two characters is at the heart of the show – driving fans into a frenzy of support when the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Company) network made noises about cancelling the show after two seasons, for all the nonsensical reasons networks cancel popular shows (refer to A/E and Longmire above). A third season was eventually commissioned and Miss Fisher carries on toward 1930.

As season three of Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries premiered in Australia, Phryne Fisher fever seemed to become contagious Down Under. There were costume exhibits, themed luncheons, and premiere parties. All of which I totally understood and would have enjoyed participate in had I been in Melborne.

All of this is a very longwinded journey to get to the point that the television show was so good, I couldn’t resist at least trying the first book in the series – which really wasn’t even close to the normal genre sweet spot of my reading habits. I wa wary as I know, from prior experiences, if you love a book then a television series or movie based on it most often disappoints. Conversely, if you love a movie or television series, the books they are based on usually pale by comparison. In the case of Miss Fisher, the television series had really caught my imagination, and I didn’t think there was a chance the books would live up to my expectations. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

At this point, I’ve finished the third Phryne Fisher book from author Kerry Greenwood and have listen to the excellent audio version of two others. The television series is one of the best book to screen translations I’ve ever come across. Greenwood’s writing is assured and has the light yet substantial touches the television series has captured so well. I’m hooked and am already freaking out because I only have fifteen more book titles, and eight shows from season three of the television series, to go.

Reading and viewing experiences like this are like shooting stars – brilliant, amazing, and gone too fast. When they've disappeared, it’s back on the hunt for more elusive treasures.

DO YOURSELF A FAVOR AND CLICK HERE TO VISIT KERRY GREENWOOD’S PHRYNE FISHER WEBSITE

CLICK HERE TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE TELEVISION SERIES

Published on August 10, 2015 22:45

L.A. GALAXY: ARE THEY UNSTOPPABLE?

L.A. GALAXY: ARE THEY UNSTOPPABLE?

L.A. GALAXY: ARE THEY UNSTOPPABLE?For my soccer-head peeps, because nobody else will understand or care...

Perhaps this is blasphemy but – taken strictly in the context of American soccer, and considering it has as much to do with the three musketeers attitude of comradery as it does with star power – could the LA Galaxy's trio of Keane, dos Santos, and Zardis become the MLS version of Messi, Naymar, and Suarez? Is there any other MLS team who can point to similar firepower?

I know it’s early days for the full strength Galaxy line-up to gel, but with Keane, dos Santos, Gerrard, Zardis, Juninho, Sebastian Llegget, A.J. DeLaGarza, Omar Gonzalez, Dan Gargon, Robbie Rogers, and Leonardo on the field – and Alan Gordon, Raul Mendiola, Baggio Husidic, Bradford Jamison, Ignacio Maganto, and Tommy Meyer ready to come off the bench, and coach Bruce Arena at the wheel – is there any other MLS team with the same level of overall potential?

I know it’s early days for the full strength Galaxy line-up to gel, but with Keane, dos Santos, Gerrard, Zardis, Juninho, Sebastian Llegget, A.J. DeLaGarza, Omar Gonzalez, Dan Gargon, Robbie Rogers, and Leonardo on the field – and Alan Gordon, Raul Mendiola, Baggio Husidic, Bradford Jamison, Ignacio Maganto, and Tommy Meyer ready to come off the bench, and coach Bruce Arena at the wheel – is there any other MLS team with the same level of overall potential? On the downside, there are still big issues with the defense, which could lead to a spectacular downfall. The Galaxy backline is shaky – the skill is there, but so is confusion in communication and positioning.

But the biggest question mark is plastered across arguably the most important position on the field. By letting world class Panamanian National goalkeeper Jaime Penedo get away, the Galaxy could have made a disasterous misstep. ‘Settling’ for rewinding the clock to bring back the rickety-handed not-so-world-class Jamaican national goalkeeper Donovan Ricketts is a head scratcher.

There is an old goalkeeper joke applicable to the situation: “Donovan Ricketts fell in front of a bus the other day, but he didn’t get hurt because the bus went under him…” In Sunday’s game against Seattle, Ricketts was constantly out of position and juggled more balls than a jester performing for an audience.

No matter how many goals the Galaxy’s front line produce (an amazing 30 in the last 12 games), if opponents can run rampant through an unorganized Galaxy defence directed by a ball-shy keeper, chances of a sixth MLS championship will vanish as quick as Jaime Penedo disappearing off the Galaxy roster.

No matter how many goals the Galaxy’s front line produce (an amazing 30 in the last 12 games), if opponents can run rampant through an unorganized Galaxy defence directed by a ball-shy keeper, chances of a sixth MLS championship will vanish as quick as Jaime Penedo disappearing off the Galaxy roster.

Published on August 10, 2015 08:38

August 8, 2015

FILM NOIR: WHEN IT FELT GOOD TO BE BAD

FILM NOIR: WHEN IT FELT GOOD TO BE BAD Film noir, a particular genre of movie storytelling, wasn’t given its label until the 1970s. Before then these types of films were merely referred to as melodramas. Enough time and distance finally passed so these movies could be looked upon as primarily very much a particular style, of presentation, low lighting, shadows, and desperate, shifty players, who were always of questionable character. The unique lighting was derived from the German Expressionists whose primary timeframe was pre-World War II, 1930s. The need to label this particular style, most dominant from 1940 to 1958, was born out of the second Golden Age of film making. In the first Golden Age, the 1930s, filmmakers were still experimenting with the new art form and it was too soon to label films with anything too exotic. All they had then were westerns, war pictures, prison pictures, and so forth. They used simple, clear labels. Jerry Lewis, after making so many movies it gave him a heart attack, wrote a tome, The Total Film-maker, which became the dog eared Bible of George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and the rest of the bearded, film school wunderkinds of the 1970s Golden age. Lewis, as their mentor, made them extremely aware they were creating art and with every frame there was potential for great technique and meaning. As a result, film criticism itself blasted off like it was the space program and many new film terms were adopted. No splice of film went unexamined after the 1970s when these very self-aware directors started putting out their fare. Film school enrollment exploded with both the filmmakers and their film critic classmates expounding on their products.

FILM NOIR: WHEN IT FELT GOOD TO BE BAD Film noir, a particular genre of movie storytelling, wasn’t given its label until the 1970s. Before then these types of films were merely referred to as melodramas. Enough time and distance finally passed so these movies could be looked upon as primarily very much a particular style, of presentation, low lighting, shadows, and desperate, shifty players, who were always of questionable character. The unique lighting was derived from the German Expressionists whose primary timeframe was pre-World War II, 1930s. The need to label this particular style, most dominant from 1940 to 1958, was born out of the second Golden Age of film making. In the first Golden Age, the 1930s, filmmakers were still experimenting with the new art form and it was too soon to label films with anything too exotic. All they had then were westerns, war pictures, prison pictures, and so forth. They used simple, clear labels. Jerry Lewis, after making so many movies it gave him a heart attack, wrote a tome, The Total Film-maker, which became the dog eared Bible of George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and the rest of the bearded, film school wunderkinds of the 1970s Golden age. Lewis, as their mentor, made them extremely aware they were creating art and with every frame there was potential for great technique and meaning. As a result, film criticism itself blasted off like it was the space program and many new film terms were adopted. No splice of film went unexamined after the 1970s when these very self-aware directors started putting out their fare. Film school enrollment exploded with both the filmmakers and their film critic classmates expounding on their products.

What was written about film noir in the 1970s was definitive and important. Twenty plus odd years of aesthetic distance helped film historians identify, clarify, and most importantly, label film noir with a name. More labels came after. Everything after 1958 is considered neo noir, especially if filmed in color. Film soleil is film noir with sunshine. The consensus that film noir is mostly about the technical style continues to dominate analysis of the genre and much has been written about the darkness of the characters as well. Yet there is more. So much more this period of this particular film genre says about history and says about, not just our society, but how we as individuals feel on the inside and how we may choose to live our very lives. What we may have missed out on in the excitement of being in the middle of viewing new creations being released into theaters firsthand, like in the 40s and 50s. Or even what we may have missed by not being in the throes of labeling an art that had been around for a while, like in the 70s, we can make up for by having the longitudinal insight to be able to see what was really going on in America in a collective sub consciousness way. Also to see how those things were expressed through this fascinating movie genre. The year the American public was the most insatiable in its appetite to consume film noir movies was 1946. One might ask why 1946? The answer could be World War II ended in 1945 and there was right after a deliberate plan to put America back into place. Primarily that core of American Society, which is very backbone the American Family.

What was written about film noir in the 1970s was definitive and important. Twenty plus odd years of aesthetic distance helped film historians identify, clarify, and most importantly, label film noir with a name. More labels came after. Everything after 1958 is considered neo noir, especially if filmed in color. Film soleil is film noir with sunshine. The consensus that film noir is mostly about the technical style continues to dominate analysis of the genre and much has been written about the darkness of the characters as well. Yet there is more. So much more this period of this particular film genre says about history and says about, not just our society, but how we as individuals feel on the inside and how we may choose to live our very lives. What we may have missed out on in the excitement of being in the middle of viewing new creations being released into theaters firsthand, like in the 40s and 50s. Or even what we may have missed by not being in the throes of labeling an art that had been around for a while, like in the 70s, we can make up for by having the longitudinal insight to be able to see what was really going on in America in a collective sub consciousness way. Also to see how those things were expressed through this fascinating movie genre. The year the American public was the most insatiable in its appetite to consume film noir movies was 1946. One might ask why 1946? The answer could be World War II ended in 1945 and there was right after a deliberate plan to put America back into place. Primarily that core of American Society, which is very backbone the American Family.

Rosie the Riveter had to give her job to a man. Get out of the factory. Put on an apron and go back into the kitchen. If she didn’t, the man would not be the head of the family. The hierarchy of the family would be askew. Society as a whole then would be messed up. The sky would eventually fall. Many, many movies were made in the second half of the 1940s that sent the not so subtle message that women needed to buckle under and let the father dictate the future of the family…or there might be no family. If there was no family then there would be no society, and then no America and so then why was the war fought? Much has been written about Meet me in St. Louis, in particular as a proclaimer of this very agenda. If the American family was not restored to the pinnacle of its idealized form, how could we justify all that was sacrificed in fighting for our freedom and the freedom of our nation’s friends? However, the passion for film noir represents that deep down much of America wasn’t buying it. We were attacked at Pearl Harbor, which finally brought the United States into the war. We were going to be warriors, and supporters of warriors. We had to find our dark sides where we were selfish, driven, ambitious, strategic and most importantly…killers. We, as a nation, had to find our inner film noir character in order to go to war. We had to go dark, black even, become comfortable in the shadows, tighten our lips or ships would sink. We had to learn to sacrifice and be stingy. And we did it. Then we won the war and the message was then about getting back to normal. But what was normal? The Great Depression that preceded the war –where the heads of households had trouble leading because they couldn’t be breadwinners? Plus, we had been to war or seen the pictures and films of war like never before. The devastation, the killing, the hunger – starvation even – and torture. No. Americans couldn’t flip flop that easily. Their hearts well knew the darkness and the splintering of the family over great distances. They knew they were supposed to want things bright and shiny, yet they flocked in droves to the movie theaters to see the dark seamy sides of life they had been living themselves for years during the war. They had been living film noir. The films could not be produced fast enough to keep up with demand. The production of film noir movies and its popularity continued through the 1950s. Forces in the culture increasingly put continued pressure on the creation of an idealized rigid family structure – a structure so stultifying, the only release from it could be gained by watching very selfish people walking around in the shadows on the big screen, while the consumer themselves sat in a darkened movie theater. The American family had to have a father who had the last word on everything, a subdued housewife/mother, obedient children, all living in cookie cutter neighborhoods in the suburbs because America went to war to protect that perceived way of life – even though it didn’t exactly exist beforehand. Having actually been film noir characters during the war, having had to be so dark, needed justification. And besides it felt cool to be legitimately bad.

Rosie the Riveter had to give her job to a man. Get out of the factory. Put on an apron and go back into the kitchen. If she didn’t, the man would not be the head of the family. The hierarchy of the family would be askew. Society as a whole then would be messed up. The sky would eventually fall. Many, many movies were made in the second half of the 1940s that sent the not so subtle message that women needed to buckle under and let the father dictate the future of the family…or there might be no family. If there was no family then there would be no society, and then no America and so then why was the war fought? Much has been written about Meet me in St. Louis, in particular as a proclaimer of this very agenda. If the American family was not restored to the pinnacle of its idealized form, how could we justify all that was sacrificed in fighting for our freedom and the freedom of our nation’s friends? However, the passion for film noir represents that deep down much of America wasn’t buying it. We were attacked at Pearl Harbor, which finally brought the United States into the war. We were going to be warriors, and supporters of warriors. We had to find our dark sides where we were selfish, driven, ambitious, strategic and most importantly…killers. We, as a nation, had to find our inner film noir character in order to go to war. We had to go dark, black even, become comfortable in the shadows, tighten our lips or ships would sink. We had to learn to sacrifice and be stingy. And we did it. Then we won the war and the message was then about getting back to normal. But what was normal? The Great Depression that preceded the war –where the heads of households had trouble leading because they couldn’t be breadwinners? Plus, we had been to war or seen the pictures and films of war like never before. The devastation, the killing, the hunger – starvation even – and torture. No. Americans couldn’t flip flop that easily. Their hearts well knew the darkness and the splintering of the family over great distances. They knew they were supposed to want things bright and shiny, yet they flocked in droves to the movie theaters to see the dark seamy sides of life they had been living themselves for years during the war. They had been living film noir. The films could not be produced fast enough to keep up with demand. The production of film noir movies and its popularity continued through the 1950s. Forces in the culture increasingly put continued pressure on the creation of an idealized rigid family structure – a structure so stultifying, the only release from it could be gained by watching very selfish people walking around in the shadows on the big screen, while the consumer themselves sat in a darkened movie theater. The American family had to have a father who had the last word on everything, a subdued housewife/mother, obedient children, all living in cookie cutter neighborhoods in the suburbs because America went to war to protect that perceived way of life – even though it didn’t exactly exist beforehand. Having actually been film noir characters during the war, having had to be so dark, needed justification. And besides it felt cool to be legitimately bad.

Returning from WWII to the conformity of the supposed American dream, letting go of a noir character’s inner darkness couldn’t have been easy. Then there were those who must have known noir was their nature to begin with – the war experience only exacerbating it, and the pressure to be part of a 1950s happy family must have been daunting.

Returning from WWII to the conformity of the supposed American dream, letting go of a noir character’s inner darkness couldn’t have been easy. Then there were those who must have known noir was their nature to begin with – the war experience only exacerbating it, and the pressure to be part of a 1950s happy family must have been daunting.A lot may have suspected they couldn’t do it. They suspected they lacked the tools to hold that kind of a family together. Some people were noir characters in reality. Other ones were noir characters in their souls,and didn’t have the guts to live it out. Instead, ill equipped as they were, they strove for the 1950s ideal, which was (is) all about conformity.

Besides the consumption of film noir to feel genuine to oneself, or to vicariously see what it was like to be so darkly driven, or to aide in the transition of having been a killer back to being a husband and father, there were other signs of leakage that it wasn’t easy to change into the pereived1950s family ideal.

Lucy wanted to work and was always trying to break into Ricky’s show, but that was a joke, right? It was laughable…women working outside of the home. Men found themselves having to hit the bar/lounge on the way home from the career battlefield and have a martini, before heading home to the domestic battlefield? Why were things more chaotic than on TV? Yes, there was leakage.

And unbelievable oppression of who an individual really was.

In the 1950 film noirs, all the women who had been strong powerful individuals before the war, or during the war, like Joan Crawford, Betty Davis, and Barbara Stanwyck, were now suddenly playing victims – females terrified by a mere phone call. The message being: stay in line, stay in the kitchen – so to speak – or you might be brought in for questioning. At worst, you could be investigated and interrogated on television for un-American activities, or at best, judged by your neighbor.

In the 1950 film noirs, all the women who had been strong powerful individuals before the war, or during the war, like Joan Crawford, Betty Davis, and Barbara Stanwyck, were now suddenly playing victims – females terrified by a mere phone call. The message being: stay in line, stay in the kitchen – so to speak – or you might be brought in for questioning. At worst, you could be investigated and interrogated on television for un-American activities, or at best, judged by your neighbor.The fictional noir characters on screen weren’t participating in this societal model in any way, shape or form. Whether they were the criminals, or the private dicks chasing them, or the showgirls, or the molls, or the mysterious widows, they were all refusing to play house. The morals police insisted all of the films prove that crime, and/or a lack of morals, were going to be punished in some way or another by the end of the film.

Many people obsessed on these characters because they remembered when they were in a war and they had to kill or be killed. That was a terrible pressure. Now, having to participate in a perfect family was also a lot of pressure.

Besides being entertained, watching a film noir was an exercise in exploring if one had chosen the wrong life to live, and if the idealized 1950s family lifestyle was as joyful as they were being led to believe.

Truthfully, there have been many parents who should not have been pressured into the 1950s happy families. Many people who should have only chased criminals and chorines might have been happy with only that. Some should have only hung at the racetrack and had dinner with friends. Or others should have spent time mostly talking on the telephone, dancing, and doing their nails.

There is no doubt a slew of people could tell you their parents would have been so much better off not trying to live the American Dream in a sheltered house surrounded by a white picket fence. They’ll tell you how much happier everyone would have been if their parents had just lived their whole lives like noir characters, rather than drag whiffs of it to the dinner table.

The pressure was so great to live in a perfect 1950s television family that by 1958 Americans finally believed they had the dream overall in the nation and film noir became far less popular as a form of relief from conformity.

That was until 1963 when Kennedy was assassinated, which showed there was a very healthy dose of the darkness still out there after all. The shock of Kennedy’s death blew the fantasy of how family life will protect you, and the nation, all to hell.

Soon after the late 40s and 50s, offspring of those who witnessed WWII, formed their own rebellion against the American Dream and, as hippies, tried and succeeded to an extent, to overthrow the establishment in which they were reared. They knew first hand it was hypocritical and oppressive.

They had been raised with morals and righteously believed a new lifestyle was the better, more moral way to live, not really seeing their own self-righteousness was a very similar offshoot from the same constricted pressure they learned at home growing up. But they did very much care about community. If they didn’t become Yuppies, they grew to be the guardians of the planet and animals. Being a conforming happy family still seem to fit in well with this alternative lifestyle.

It can also be argued that artists, designers, and most very creative people can also be very alternative in their lack of need for the 1950s family structure. Their creative drive is paramount to everything else. They get fulfillment through the results of their creative output and products.

The satisfaction creative artists and tree huggers derive from their passions denote an inner emotional world that, although still being alternative from the happy family tradition, are still pro social.

Noir characters, on the other hand, don’t live for others. They live self-righteously and selfishly. And the genre will never completely die because there are those who are not built for family life, creativity, or granola eating. These noir individuals will seek, consciously or not, justification for living life as who they are, in the shadows or not.

The inclination here might be to label them sociopathic, but that temptation is counter intelligent to the fact the gumshoes and cops, and their informants, are also very much noir characters. They are driven by their own inner worlds that may be about protecting the American family, and society etc., which doesn’t necessarily mean they want personally to live that conforming lifestyle.

Film noir characters are primarily emotion driven. Auteur Stanley Kubrick said only two emotions drive them: desire and threat. I would add adrenaline. Noir characters get bored easily. Adrenaline is a physical addiction and not necessarily a desire. They would never be happy living in the suburbs or hanging at the Mall of America.

Conformity and the traditional family structure might be sought out for those who need daily routine, for those who fear the tumultuousness of being around those who are selfishly driven. But as long as those in the burbs question their static lifestyles, and they wonder internally if the sacrifices they make for that peace are worth it, or worse, suspect they have given up their coolness for stability, there will always be noirs to serve the explorations of their own natures.

Thx to the late Suzanne Manders for her input into this article.

Published on August 08, 2015 16:36

August 4, 2015

HANDLING YOUR CHARACTER’S BACKSTORY

HANDLING YOUR CHARACTER’S BACKSTORY

HANDLING YOUR CHARACTER’S BACKSTORYMy first novel (Shroud of Vengeance) was part of an ongoing adult western series (think Louis L’Amour with sex scenes) featuring a character named Diamondback. The editor gave me the bible for the series providing the limited information needed as part of the characters backstory: Diamondback got his nickname after being the victim of a horrible whipping, he is wanted for a murder he didn’t commit, he wanders the west acting as a travelling judge settling disputes between outlaws and he is very, very popular with the ladies.

It was pretty simple to include this information as part of the ongoing series of books, which could be read in any order without any intrusive information dumps or large chunks of narrative explanation. Drop the nickname on the first page, show his scars when he takes off his shirt for the first sex scene, and tie the plot into a dispute between dangerous outlaws for Diamondback to settle. With series of this type, the main character remains static. There are no consequences or character arcs to carry over from one book to the next.

Until the last decade most television series were also examples of this type of storytelling. This was perfect for reruns, as series could be shown in any order. Think about I Love Lucy. It doesn’t matter which episode a viewer watches, the set-up is immediately clear – wacky redhead doing wacky things. There is no need to know what has happened in prior episodes. There are no ongoing storylines to confuse the narrative if episodes are shown out of order. Many, many mystery and cop shows operated, and still operate, on the same principle.

However, times have changed. Now, books and many of the most popular television series thrive on ongoing storylines continuing from episode to episode, or book to book, to maintain viewer/reader loyalty.

When my literary career moved on from writing under a house name pseudonym (which in the case of Diamondback just happened to be Pike Bishop) to my first standalone, hardcover, novel under my own name (Citadel Run now Hot Pursuit in e-book), I ran into this problem. What I had envisioned as a standalone novel, suddenly became the first in a series when the publisher asked for another book with the same characters (Sand Against the Tide now Deep Water in e-book). Staring at the blank page at the start of writing the second book, I was faced with the problem of how to integrate the complicated backstory and relationships of the characters established in the first book into the narrative of the second.

My issues with the situation also included overcoming the fact I had wrapped up the first book with the main character retiring from the police department and his female partner promoting to detective. I probably would never have done this if I had realized I was going to be writing more books with the same characters. As it was, I had to quickly figure out a fictional situation in which these two main characters could continue to interact together on the same case.

After writing the second book in the series, I went on to write another standalone novel (Chapel of the Ravens now Penalty Shot in e-book). Not having learned my lesson the first time around, I again ended the novel in a way precluding an easy transition to a second book with the same character and, consequently, there was never a second book. Publishers love series characters as a way to build reader loyalty, and I was shooting myself in the foot.

When I sat down to write my next novel (Kill Me Again), I decided upfront I would also design the book to be the first in a series. As a result, I outlined a four book story arc for the main character, LAPD detective Fey Croaker. I also took into consideration story arcs for the secondary characters comprising her crack homicide squad.

One of my concerns in doing this was how much background from the first book in the series needed to be included in the second book. And how about the third and fourth books? Did I need the same amount of backstory? More? Less? Or did I need any?

Currently, almost all television show writing staffs plan out a full season story arc before any individual episodes are written. When the individual episodes are created, there is already a larger established macro arc containing what information needs to be included in the micro arc of each individual episode to keep viewers watching.

There is almost always a quick story recap provided usually in dialogue at the beginning of each individual script act. This is done to bring a viewer up to speed if they have just turned on their set or are channel surfing from other shows. Television also uses previously on… lead-ins before the new episode starts to remind regular viewers of story points, or bring new viewers into the fold.

The previously on… technique is almost impossible to use in the novel form. Prologues have also become unfashionable in our modern world of instant gratification. Contemporary readers want to jump right into a story without wading through a prologue providing either tedious backstory or unnecessary teaser information. So, what to do? In episodic television, you never hear long expositional explanations of character history or incidents from previous episodes. Instead, the action on the screen is so crisp and clear, viewers become invested in the show from the first scene. The same thing needs to happen on the page. To accomplish this, you need to emulate what occurs in the television world, where staff writers for a show create a macro story arcfor the season before creating the micro story arcs for each individual episode. This way, each individual episode of a show contains all of the beats of the micro arc for the episodes specific storyline, as well as one, two, or three beats needed to progress the storyline of the macro arc. To imitate this, you need to create a macro story arc for the first three to four books you plan in a series. Then, as you write the micro arc of the plot for each individual novel, you also included several elements from your macro arc which continues from book to book. The macro arc for my Fey Croaker novels involved Fey’s personal life deteriorating and her character becoming more and more isolated until, in book four (Chalk Whispers), events force her to deal with the demons of the abuses from her past. In the first book, Kill Me Again, I established Fey’s background, laying out the beginnings of the macro arc, as she moved through the books specific plot of a current murder victim whose identity shows she was murdered ten years earlier the micro arc of this specific book. In Grave Sins, the micro arc deals with a series of male murders possibly committed by an NBA rookie phenom. To keep up with the macro arc, I included several elements to turn up the heat on Fey: Her professional ethics are called into question; her low-life brother makes unreasonable demands and ends up as the killers bait. Without giving all the twists away, Fey ends the storyline completely isolated from family and increasingly distanced from her own team. The micro arc of Tequila Mockingbird takes Fey and her crew into the world of deep undercover cops, referred to as mockingbirds, when one is murdered in front of station. As Fey unravels the plot, she is aided by a character with whom she can’t help falling in love despite the fact she knows he’s dying (more crushing isolation). There is a strong, action-filled ending to the book, but Fey finishes shattered, emotionally raw, and completely vulnerable – fulfilling the needs of the macro arc. The four book macro arc culminates in Chalk Whispers, where it is completely tied into the micro arc of a plot involving a cold case investigated by Fey’s deceased, abusive, cop father. As the past comes back, it puts Fey’s life in danger, forcing her to confront all her own bad behaviors, co-dependencies, and mistakes, which have led her to this point in her life. She eventually finds happiness through the final resolution of the macro arc. Within each of those novels, I also worked in macro arcsfor each of the partnership duos comprising Fey’s homicide team. And before I started book five, I created another four book macro arc, which unfortunately wasn’t resolved as the series fell victim to the curse of traditional publishing’s mid-list. By using a macro arc, which slowly spools out, each novel in a series has its own internal structure, allowing returning and new readers alike to keep moving forward without feeling they have either missed something or getting bored by the same info dumps of backstory again and again. To recap: A macro arc contains those things your characters need to be slowly accomplishing as the series progresses. The individual plots to your novels comprise the micro arc story beats your characters need to rapidly accomplish in resolving the current story line. If you follow a three or four book macro arc for your series, you won’t need any exposition about the past. If your writing is crisp enough, the established structure and character interactions will quickly become clear as they fulfill the micro arc in the current storyline. This is the dynamic that keeps the pages turning. This article first appeared in two parts in my weekly column on Venture Galleries. To read more CLICK HERE

Published on August 04, 2015 08:05

July 29, 2015

REEVALUATING THE AVENGERS ON FILM

REEVALUATING THE AVENGERS ON FILM

REEVALUATING THE AVENGERS ON FILMThe pending release of the new Man From U.N.C.L.E. film recently sparked a discussion on Facebook of the 1998 film The Avengers – a big screen adaptation of the iconic television show of the same name. Digging deep into this subject matter experts Jack Walter Christian, Mathew Bradford, and my humble self. What follows is a compilation of the shared comments… JACK WALTER CHRISTIAN Here's a rather controversial subject for movie buffs and film fanatics whom I will find having a dispensable disagreement with my point of view, or perhaps the classification of The Avengers, 1998 film, screen adaptation of Sydney Newman's television series of the same name from the 1960s, citing the Emma Peel era. Where do I begin? I have seen this film countless times I have lost track. Almost thirty years after the original series, Warner Bros have brought us the film version of Steed and Mrs. Peel's escapades. Not a reboot (sigh, overtly used word, nowadays), nor a continuation, but rather a film of its own. It follows the perspective of the notable two protagonists publicly known as the spies who "save the world in style", putting them against a very dangerous threat that could excruciate the entire planet of the mankind (amongst the other mortal beings) if not prevented in time. Obviously, the film was over-the-top, as was the original television series since halfway the second season, giving the franchise its own template rather than being down-the-earth spy thriller. What was the fault of the film? To tell you the truth, I cannot comprehend. I can see none. Sure, it's always the mainstream statement that brainwash people into believing something and insisting upon, while the rest of us maintain the reputation of being wrong. The primary argument that would headline the whole over-criticizing of the motion picture is, It's nothing like the original show!Care to explain? Because the severe times I have compared them both, brought them to constant conclusions of innumerable set of analysis, they are more but not less the same. Just with an updated atmosphere, while keeping the spirit of the original show. No lover of fantasy/escapist adventures? Well, if I remember correctly, or my eyes don't betray me, The Avengers John Steed led was all about escapism, nothing regular we see in real-life, always dealing with strange subjects that the antagonists composed in every separate episode. Obviously, after thirty years, especially a film adaptation, was going to be bigger than just what the standards of television represented with outdated-as-of-now technology. What were you expecting? Cameras recording an immobile vehicle with a beforehand recorded projection behind it? Or were you so eager to see a very slow-paced, low-budget, all-dialogues no action flick where actors and actresses only pretended what they are meant to be and showing off to one another? Perhaps some fans are far too conservative in the topic that they no longer appreciate extension or expansion. Or...some would just prefer miserable films in which nothing is fun nor entertaining. The very same people, for instance, who hated Pierce Brosnan's era of the James Bond films. Or I could go as far to say... the upcoming The Man from UNCLE film that severely goes mocked by every 50/60 year old fan of the source material. Indeed very miserable, isn't it? Now, we constantly get comparisons to other film adaptations from original television series such as I-Spy(2002), Wild Wild West (1999), The Saint (1997), Starsky and Hutch (2004), among some others. These aforementioned titles did drift away from the original source material, as did U.N.C.L.E. (2015) to some extent. But, some of them are quite entertaining that I would watch, again, except The Saint which I will never approve of because it has weakened the cocky and overtly-confident personification of Simon Templar, while U.N.C.L.E., to my understanding, injects some newer stuff into the material and changes some of the backstories while being a fun film to see, judging by the extended trailers. What is the point behind relentlessly submitting mockery to The Avengers? If it was the acting that received worst-something-awards, I've got to point out, it doesn't strike to me as relevant to a tiny bit. Ralph Fiennes played a very brilliant John Steed with similar performance to what Patrick Mancee's was. Similar. Do note on that word, please. While Uma Thurman's Emma Peel was slightly different from Diana Rigg's, she brought a lovely execution with her act, stereotypically channeling the way the actors pulled their own performances in the 1960s. Different time, different era. What was to dislike? Nothing I could detect. One would argue about the theme tune? It was there. John Steed in his full attire? Present. Steed's signature car? Present, yet again. Emma Peel in her lovely of tight clothes, stylish and sometimes provocative catsuits? Right in the open! So, what was bad about this film, if I may ask? Didn't feel like the original? How so? Too over-the-top? Then, why does Marvel's own Avengers get all the praise while this one is always disputed? Oh, it's a superhero stuff, these are just spies, aren't they? I think you and I know very well that Steed's Avengers weren't just spies, they were super-spies facing supervillains along with their overcomplicated plots. Heck, even the roles they have plated were impeccable. What is the problem, then?

PAUL BISHOP Okay, I've been on the side of this film being a disaster. As I haven't seen it once it came out, your commentary has made me think I need to see it again and reassess. Off the top of my head, my feeling was the actors in The Avengers had been directed to ‘act’ their roles as opposed to ‘inhabiting’ them – bringing no originality or trace of the actors on personality (this type of thing is totally the director’s fault – not the fault of the writing or the actors themselves). I could feel Feinnes and Thurman trying so hard to color within the lines, I could see the ‘acting’ which kept me from getting into the film. Clearly, I'm coming from an unusual perspective. Most fans of the original series on which remakes/reboots are based are looking for the exact same things they loved in the original. I prefer ‘reimaginings’ … Keeping the spirit of the original while bringing something new to the franchise. This still often goes awry as in the I Spy, Starsky and Hutch, and Wild Wild West big screen remakes. There was obviously no understanding of the original material, and the characters were treated as if the film was a Mad Magazine parody – constantly pointing out everything that was flawed or silly when seeing the original shows through a more modern perspective. For me, The Saint feature film had no connection to the original series, it was too different. As a result, I enjoyed it more than you did as I was able to divorce the film for the series as I watched it. The Mission Impossible films mostly get the mix of original and update right. The original Star Trek films had the advantage of the same actors inhabiting the roles they originally brought to life, but even J.J. Abrams take on Star Trek with new actors works for me – perhaps because I am a casual Star Trek fan, not a purist or a fanatic (although, I do have my willing suspension of disbelief shattered not by the made up science fiction of space travel, but by those things within the ST films that make a mockery of physics). I think director Guy Ritchie got things mostly right in his Sherlock Holmes films with Robert Downey Jr., which give me hope for the new U.N.C.L.E. film (which he also directed). The series was brilliant in its day, but watching the reruns on Me TV recently, it doesn’t hold up particularly well filtered through modern sensibilities – it has become quaint. As a result, I’m ready for a reimagining of the concept to breathe new life into U.N.C.L.E. But, you’ve convinced me to take another look at The Avengers and possibly reassess my opinion.

PAUL BISHOP Okay, I've been on the side of this film being a disaster. As I haven't seen it once it came out, your commentary has made me think I need to see it again and reassess. Off the top of my head, my feeling was the actors in The Avengers had been directed to ‘act’ their roles as opposed to ‘inhabiting’ them – bringing no originality or trace of the actors on personality (this type of thing is totally the director’s fault – not the fault of the writing or the actors themselves). I could feel Feinnes and Thurman trying so hard to color within the lines, I could see the ‘acting’ which kept me from getting into the film. Clearly, I'm coming from an unusual perspective. Most fans of the original series on which remakes/reboots are based are looking for the exact same things they loved in the original. I prefer ‘reimaginings’ … Keeping the spirit of the original while bringing something new to the franchise. This still often goes awry as in the I Spy, Starsky and Hutch, and Wild Wild West big screen remakes. There was obviously no understanding of the original material, and the characters were treated as if the film was a Mad Magazine parody – constantly pointing out everything that was flawed or silly when seeing the original shows through a more modern perspective. For me, The Saint feature film had no connection to the original series, it was too different. As a result, I enjoyed it more than you did as I was able to divorce the film for the series as I watched it. The Mission Impossible films mostly get the mix of original and update right. The original Star Trek films had the advantage of the same actors inhabiting the roles they originally brought to life, but even J.J. Abrams take on Star Trek with new actors works for me – perhaps because I am a casual Star Trek fan, not a purist or a fanatic (although, I do have my willing suspension of disbelief shattered not by the made up science fiction of space travel, but by those things within the ST films that make a mockery of physics). I think director Guy Ritchie got things mostly right in his Sherlock Holmes films with Robert Downey Jr., which give me hope for the new U.N.C.L.E. film (which he also directed). The series was brilliant in its day, but watching the reruns on Me TV recently, it doesn’t hold up particularly well filtered through modern sensibilities – it has become quaint. As a result, I’m ready for a reimagining of the concept to breathe new life into U.N.C.L.E. But, you’ve convinced me to take another look at The Avengers and possibly reassess my opinion.

MATHEW BRADFORD I think you're right, Jack, that this movie gets a worse rap than it deserves. That said, I'm hopelessly torn on it myself, and always have been. I was so excited for it. And there was a lot I liked about it. I saw it many times in the theater that summer. But there were also huge things I didn't like about it. And I remain divided to this day. What I love is its world and its production design. The movie's "Avengersland" is not the same as the TV series', but is equally surreal and based on a Never-Never Britain, on Americans' idea of quaint Olde England, the same cherished but not quite real past that the Kinks sing about on Village Green Preservation Society. That was great. The movie was even weirder than the show ever really got! I loved the bear suits and wasp drones. What I didn't like was the lead actors. And I'm a fan of both of theirs. I had a huge crush on Uma in high school, and still do, really. She's one of my favorite actresses. But somehow, both of them are bad in that movie--or at least in the version we've seen. And not just a little bad. Really bad! I agree with all of Paul's points about the performances. He hit the nail on the head saying it feels like they're acting rather than inhabiting the characters. And like him, I've always laid the blame for that on the director, because I know both those stars are capable of delivering excellent performances! And in The Avengers, they feel somnambulant. They've confused the "effortless cool" oozed by Macnee and Rigg with detachment. You never feel like there are any stakes for either character, because their reaction to any situation is to not react. When Rigg's Mrs. Peel is tied up by a diabolical mastermind, she keeps her cool, sure, and delivers witty rejoinders... but that's a veneer. She still very much cares. Just watch her trying to keep that car driving on the simulator in Dead Man's Treasure, for example. There's no such caring in either Fiennes' or Thurman's performances. But is it fair to judge them and director Jeremiah Chechik on the movie we've seen, which was famously re-cut and re-scored by the studio? I tend to think not. Because Chechik is also generally reliable. National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation is one of my favorite comedies of its era, and a movie I watch every year at the holidays. And he's recently directed some of the best episodes of Burn Notice. So I'd really like to see his director's cut. I think WB really missed out when they turned down his offer to finish it for free for inclusion on the Blu-ray. It's a real shame. What we have is ultimately a very compromised film, and it's really impossible to judge the original intent. Personally, I can't imagine exactly how a different cut would make those sleepwalking performances suddenly work, but it just might! We'll never know. And when it comes to the score, while I'm very curious to hear the rejected one, I have to say, I absolutely loveMcNeely's music from the finished film. In fact it's my favorite part of the movie! And frequent writing music for me. Finally, if you've never read the original script, I really suggest doing so. I think it's excellent on the page. I read it and hear Macnee and Rigg in my head. I don't think that the roles couldn't be played by other people, but I am convinced that the dialogue was written with them in mind. And if you hear the lines in their deliveries, they work. Plus, some great moments got cut out of the film. I really, really hope that one day Chechik's original vision gets released so we can really properly judge the movie.

MATHEW BRADFORD I think you're right, Jack, that this movie gets a worse rap than it deserves. That said, I'm hopelessly torn on it myself, and always have been. I was so excited for it. And there was a lot I liked about it. I saw it many times in the theater that summer. But there were also huge things I didn't like about it. And I remain divided to this day. What I love is its world and its production design. The movie's "Avengersland" is not the same as the TV series', but is equally surreal and based on a Never-Never Britain, on Americans' idea of quaint Olde England, the same cherished but not quite real past that the Kinks sing about on Village Green Preservation Society. That was great. The movie was even weirder than the show ever really got! I loved the bear suits and wasp drones. What I didn't like was the lead actors. And I'm a fan of both of theirs. I had a huge crush on Uma in high school, and still do, really. She's one of my favorite actresses. But somehow, both of them are bad in that movie--or at least in the version we've seen. And not just a little bad. Really bad! I agree with all of Paul's points about the performances. He hit the nail on the head saying it feels like they're acting rather than inhabiting the characters. And like him, I've always laid the blame for that on the director, because I know both those stars are capable of delivering excellent performances! And in The Avengers, they feel somnambulant. They've confused the "effortless cool" oozed by Macnee and Rigg with detachment. You never feel like there are any stakes for either character, because their reaction to any situation is to not react. When Rigg's Mrs. Peel is tied up by a diabolical mastermind, she keeps her cool, sure, and delivers witty rejoinders... but that's a veneer. She still very much cares. Just watch her trying to keep that car driving on the simulator in Dead Man's Treasure, for example. There's no such caring in either Fiennes' or Thurman's performances. But is it fair to judge them and director Jeremiah Chechik on the movie we've seen, which was famously re-cut and re-scored by the studio? I tend to think not. Because Chechik is also generally reliable. National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation is one of my favorite comedies of its era, and a movie I watch every year at the holidays. And he's recently directed some of the best episodes of Burn Notice. So I'd really like to see his director's cut. I think WB really missed out when they turned down his offer to finish it for free for inclusion on the Blu-ray. It's a real shame. What we have is ultimately a very compromised film, and it's really impossible to judge the original intent. Personally, I can't imagine exactly how a different cut would make those sleepwalking performances suddenly work, but it just might! We'll never know. And when it comes to the score, while I'm very curious to hear the rejected one, I have to say, I absolutely loveMcNeely's music from the finished film. In fact it's my favorite part of the movie! And frequent writing music for me. Finally, if you've never read the original script, I really suggest doing so. I think it's excellent on the page. I read it and hear Macnee and Rigg in my head. I don't think that the roles couldn't be played by other people, but I am convinced that the dialogue was written with them in mind. And if you hear the lines in their deliveries, they work. Plus, some great moments got cut out of the film. I really, really hope that one day Chechik's original vision gets released so we can really properly judge the movie.

JACK WALTER CHRISTIAN Some accurate points you've put there, Matthew, as usual. However, I do disagree on the way Fiennes and Thurman's performances were delivered. I know, they were acting, but it's the way I somewhat felt both Macnee and Rigg were doing, quite honestly. And I've got to state, the television series concentrated on science fiction in the later episodes quite heavily, I can see no fault in the movie bringing it to a higher level with weather control. Heck, it even is possible in real-life to control the weather, just portrayed in a cartoony way in The Avengers, but then again, I would imagine the original series doing it the same way. Since Macnee took the lead, the series drifted from the serious tone to rather parody-themed episodes, and not necessarily in a spoofed manner. The whole Britain thing in the film was indeed what was envisioned in the TV series. You know the phrase. Then again, it wouldn't be Avengers if they didn't. McNeely's score was very brilliant I could definitely see him scoring a classic James Bond film. Heck, to this day, I enormously enjoy listening to the end credits song... well, one of them anyway... Graces Jones' Storm. And to my knowledge, it was written especially for the film.

JACK WALTER CHRISTIAN Some accurate points you've put there, Matthew, as usual. However, I do disagree on the way Fiennes and Thurman's performances were delivered. I know, they were acting, but it's the way I somewhat felt both Macnee and Rigg were doing, quite honestly. And I've got to state, the television series concentrated on science fiction in the later episodes quite heavily, I can see no fault in the movie bringing it to a higher level with weather control. Heck, it even is possible in real-life to control the weather, just portrayed in a cartoony way in The Avengers, but then again, I would imagine the original series doing it the same way. Since Macnee took the lead, the series drifted from the serious tone to rather parody-themed episodes, and not necessarily in a spoofed manner. The whole Britain thing in the film was indeed what was envisioned in the TV series. You know the phrase. Then again, it wouldn't be Avengers if they didn't. McNeely's score was very brilliant I could definitely see him scoring a classic James Bond film. Heck, to this day, I enormously enjoy listening to the end credits song... well, one of them anyway... Graces Jones' Storm. And to my knowledge, it was written especially for the film.

MATHEW BRADFORD I wasn't faulting the movie for being even more out there than the show. I was praising it for that! I love the out there-ness of the color seasons! However, I think there's a huge difference between how Macnee and Rigg are playing it compared to Fiennes and Thurman. I can see the latter seem to be tryingto do what the former did, but to me they really miss the mark – in the released version, anyway.

MATHEW BRADFORD I wasn't faulting the movie for being even more out there than the show. I was praising it for that! I love the out there-ness of the color seasons! However, I think there's a huge difference between how Macnee and Rigg are playing it compared to Fiennes and Thurman. I can see the latter seem to be tryingto do what the former did, but to me they really miss the mark – in the released version, anyway.

JACK WALTER CHRISTIAN I don't think we'll ever see anything from it, again, Matthew. Back then, to my knowledge, the premiere for the film was cancelled due to the fans being outraged or somewhat. So, all in all, I hardly think anyone will ever mention the film nor talk about it. The same way people treat Die Another Day for instance, if not worse. I would have really killed to see an Avengers sequel with the same cast, perhaps with a better cinematographer and a director.

JACK WALTER CHRISTIAN I don't think we'll ever see anything from it, again, Matthew. Back then, to my knowledge, the premiere for the film was cancelled due to the fans being outraged or somewhat. So, all in all, I hardly think anyone will ever mention the film nor talk about it. The same way people treat Die Another Day for instance, if not worse. I would have really killed to see an Avengers sequel with the same cast, perhaps with a better cinematographer and a director.

Published on July 29, 2015 14:06

July 28, 2015

CRY U.N.C.L.E. AGAIN

CRY U.N.C.L.E. AGAIN

CRY U.N.C.L.E. AGAINI’ve written before about the profound influence The Man From U.N.C.L.E. television show has had on my life – specifically in my choice of careers as both an L.A.P.D. cop (had to work somewhere with initials) and as a writer. Currently, we are a little more than two weeks away from the August 14th premiere of a rebooted, reimagined, major Warner Bros. feature film based on the original television series, which first aired on NBC fifty years ago.

The film is not a remake, so I am not going to spend more than a paragraph on the segment of fans of the original series who have curmudgeonly decided, sight unseen, that the new movie is a travesty and an insult to the memories of their childhood. They are upset because the film is not a carbon copy of the original series, does not (most probably) include the original U.N.C.L.E. theme music, and stars current actors who are not clones of Robert Vaughn and David McCallum (the original stars of the series). To those fans I can only say, “Get a life.”

Personally, I can’t wait to see (on an IMAX screen opening night) what director Guy Ritchie has done with the original material. From the looks of the thrilling (yes, thrilling) extended trailer released at the recent – packed – U.N.C.L.E. panel at Comic-Con, Ritchie and stars Henry Cavill and Armie Hammer have captured lightening in a bottle. Those things that set the original series apart from other spy shows and Bond imitators are all in place – the sixties cold war setting, the light touch of humor, and the actual characters (as opposed to just the names) of Napoleon Solo and Illya Kuryakin (respectively Cavill and Hammer).

Sight unseen, I’m stoked. But let’s back up a sentence or two. Did I say a packed Comic-Con U.N.C.L.E. panel? There’s a sentence I never thought I’d write, but it’s an excellent measure of how U.N.C.L.E. has once again captured the public imagination. I’m more used to mentioning The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and receiving blank stares from the current generation – “Dude, you must be really old. I have no idea what you are talking about.” I dare not mention the first season was in black and white.

Sight unseen, I’m stoked. But let’s back up a sentence or two. Did I say a packed Comic-Con U.N.C.L.E. panel? There’s a sentence I never thought I’d write, but it’s an excellent measure of how U.N.C.L.E. has once again captured the public imagination. I’m more used to mentioning The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and receiving blank stares from the current generation – “Dude, you must be really old. I have no idea what you are talking about.” I dare not mention the first season was in black and white.Suddenly all that has changed and U.N.C.L.E. is back on the radar. Almost every pop culture and entertainment magazine has featured extended, positive coverage of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. film. Young, popular, YouTube bloggers are doing retrospectives on the series to bring everyone up to date while expressing anticipation for the new film. There are billboard ads and U.N.C.L.E. one-sheets pasted and posted everywhere. There are press parties in Rome, premiere parties in England, and the stars of the film are on red carpets everywhere promoting the film as well as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and every other form of social networking large or small. Heck, there is even new U.N.C.L.E. merchandising – the first in forever – in the form of branded plastic soda cups from Carl’s Jr. And don’t even look at the prices the original U.N.C.L.E. toys, games, guns, gum cards, books and comics are garnering on e-Bay.

For me, the biggest indication the movie is going to play strong, is Warner Bros. decision to move the film from its original release date in January 2015 – the traditional dumping spot for films the studios think are going to tank – to a prime August spot at the end of the blockbuster season. The Man From U.N.C.L.E. even scared the studio behind that other successful ‘60s series reboot, Mission Impossible, into moving the release date of Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation forward to two weeks earlier than the U.N.C.L.E. release. Now, that’s a great sign those in the know are taking The Man From U.N.C.L.E. seriously.

For the sake of full disclosure, it should be noted this isn’t the first Man From U.N.C.L.E. feature film release. During the height of the original show’s popularity there were eight U.N.C.L.E. feature films released. Six simply comprised two-part episodes of the actual show edited together with added footage to spice things up (One Spy Too Many, One of Our Spies Is Missing, The Spy in the Green Hat, The Karate Killers, The Helicopter Spies and How to Steal the World). The two other films, I believed, were expanded versions of original episodes release to international markets (To Trap A Spy and The Spy With My Face).

These cobbled together movies made a lot of money both domestically and overseas for the U.N.C.L.E. franchise and added immeasurably to the world-wide tidal wave of U.N.C.L.E. fever. In 1983, there was even a made-for-TV movie, Return of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. ~ The Fifteen Years Later Affair, complete with the original actors. However, this new U.N.C.L.E. film is the first truly big screen adaptation of the material.

I really liked what new U.N.C.L.E. director Guy Ritchie did with the venerable character of Sherlock Holmes in the two films starring Robert Downey Jr. Again they were not remakes, but reimaginings, bringing Holmes to a whole new generation of fans and paving the way for the popular current television series Sherlock and Elementary. I’m expecting no less from Ritchie’s take on U.N.C.L.E.

Am I setting myself up for disappointment? The curmudgeons certainly think so as they point again and again to previous disasterous attempts to bring popular television series from the same era to the big screen. I agree the movies based on I Spy, The Wild Wild West, Starsky & Hutch, and The Avengers (the real Avengers not those costumed clowns) were pretty much unwatchable. But Mission Impossible has won through and my money is on The Man From U.N.C.L.E. doing the same.

If not, I’ve had a blast enjoying the build-up and have delighted in seeing a new wave of potential U.N.C.L.E. fans cresting at just the right time.

Open Channel D …

Published on July 28, 2015 08:36

July 22, 2015

RACING WITH BIKES, WITH WORDS, AND ON FILM

Racing with bikes, with words, and on film The Tour De France is once again speeding recklessly through the French countryside with all its accompanying hoopla, crashes, and feats of almost inhuman endurance. After following the first three stages, I was prompted to visit my bookshelves to revisit my favorite cycling fiction and check my DVD collection for my favorite cycling films. Not all of these titles revolve around the Tour de France, but all bring out the reality, agony, and determination of cycling’s two-wheeled speed demons. Taking the movies first, I have to give my top vote to 1985’s American Flyers. Starring Kevin Costner as a cycling sports physician with a secret who persuades his younger brother to train with him for a three-day bicycle race across the Rocky Mountains known as The Hell of the West. The racing scenes are well shot and the bonding relationship between the two brothers is worth the price of admission. As in most sports films, prepare to cheer while shedding a tear.

Racing with bikes, with words, and on film The Tour De France is once again speeding recklessly through the French countryside with all its accompanying hoopla, crashes, and feats of almost inhuman endurance. After following the first three stages, I was prompted to visit my bookshelves to revisit my favorite cycling fiction and check my DVD collection for my favorite cycling films. Not all of these titles revolve around the Tour de France, but all bring out the reality, agony, and determination of cycling’s two-wheeled speed demons. Taking the movies first, I have to give my top vote to 1985’s American Flyers. Starring Kevin Costner as a cycling sports physician with a secret who persuades his younger brother to train with him for a three-day bicycle race across the Rocky Mountains known as The Hell of the West. The racing scenes are well shot and the bonding relationship between the two brothers is worth the price of admission. As in most sports films, prepare to cheer while shedding a tear.

1979’s Academy Award winning Breaking Away has obviously garnered more than its share of acclaim. However, this tale of a hardscrabble kid obsessed with Italian bike racers, and the small town clash between blue collar cutters and the much more affluent Indiana University students, is still a delight. If you haven’t seen it, or haven’t seen it in a while, now is the time to add it to your Netflix’s queue.

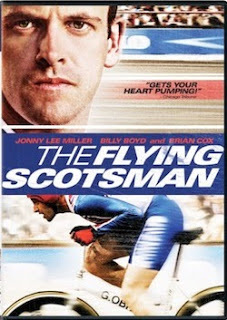

My favorite Sherlock, Jonny Lee Miller gets his cycling groove on in 2006’s The Flying Scotsman. The true story of Graham Obree, growing up from a bullied childhood to become a champion cyclist, by way of designing his own bikes and innovating in body-position aerodynamics. Miller as Obree does a good line in paranoia, however the film was completed before Obree’s more recent revelations, which help explain why he tried to commit suicide on three occasions. To bring this column back to the Tour de France, 2004’s Höllentour – Hell On Wheels – takes us inside the Tour de France. A documentary, the film focuses on the trials and tribulations of the T-Mobile team as they struggle to compete on cycling’s biggest stage. There are some heartbreaking moments which bring the whole scope of the race into focus.

I remember my first exposure to cycling fiction. From the bookmobile that visited my elementary school, I checked out a battered copy of The Big Loop by Claire Huchet Bishop. I don’t remember if it was the cycling or the author’s last name that made me read this, but I was hooked from the first page of the sepia toned world of the 1950s, in which Frenchmen always win their own Tour and the teenage fiction that heroes are easily distinguished from villains. Perhaps this is outdated by today’s standards, but years later, I tracked down a used copy and have it sitting proudly on my book shelves. Between 1995 and 2002, author Greg Moody produced five cycling murder mysteries featuring bike racer and reluctant sleuth, Will Ross. Two Wheels, Perfect Circles, Derailleur, Dead Roll, and Dead Air, are all above average sports mysteries with scalpel-like insights into both cycle racing and the business of cycle racing. Two novels by Dave Shields, The Race and The Tour, are as fast-paced as the sprint legs of the Tour de France on which their stories focus. Troubled American racer Ben Barnes has a chance to redeem his honor, keep his word, and overcome the secrets of his past. Both books contain top notch race scenes from an author who learned his craft in the saddle.

My favorite Tour de France book can most likely be described as two-wheeled chick-lit. Yes, I know, many of you will be turned off by that term, but you’ll be missing out on what is a terrific insider story. Cat by Freya North features the requisite Bridget Jones style journalistic heroine who sets out to report the Tour de France, inevitably getting entangled with some shaven legs along the way. That said, North’s research into the race and the personalities who ride in it gradually takes over the story giving the reader vicarious experience not to be missed. As the Tour itself heads out over the Pyrenees, cycle enthusiasts can get out on the road themselves or used the above recommendations to settle back into a visual or literary peloton.

Published on July 22, 2015 14:50

LIFE IS THE RING ~ WRITING FIGHT CARD: JOB GIRL