Marc Laidlaw's Blog, page 6

December 23, 2016

Year’s Finest is Full

Paula Guran has put out the Table of Contents for the latest volume in her annual collection, The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror: 2017.

“The Finest, Fullest Flowering” made the cut, and is in some splendid company.

The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror: 2017

[Cover is not finalized]

Contents (in alphabetical order by author’s last name)

“Lullaby for a Lost World,” Aliette de Bodard (Tor.com 06/16)

“Our Talons Can Crush Galaxies,” Brooke Bolander (Uncanny #13)

“Wish You Were Here,” Nadia Bulkin (Nightmare # 49)

“A Dying of the Light,” Rachel Caine (The Gods of H.P. Lovecraft)

“Season of Glass and Iron,” Amal El-Mohtar (The Starlit Wood: New Fairy Tales)

“Grave Goods,” Gemma Files (Autumn Cthulhu)

“The Blameless,”Jeffrey Ford (The Natural History of Hell)

“As Cymbals Clash,” Cate Gardner (The Dark #19)

“The Iron Man,” Max Gladstone (Grimm Future)

“Surfacing,” Lisa L. Hannett (Postscripts 36/37: The Dragons of the Night)

“Mommy’s Little Man,” Brian Hodge (DarkFuse, October)

“The Sound of Salt and Sea,” Kat Howard (Uncanny #10)

“Red Dirt Witch,” N. K. Jemisin (Fantasy #60)

“Birdfather,” Stephen Graham Jones (Black Static #51)

“The Games We Play,” Cassandra Khaw (Clockwork Phoenix 5)

“The Line Between the Devil’s Teeth (Murder Ballad No. Ten),” Caitlin Kiernan (Sirenia Digest #130)

“Postcards from Natalie,” Carrie Laben (The Dark #14)

“The Finest, Fullest Flowering,” Marc Laidlaw (Nightmare #45)

The Ballad of Black Tom, Victor LaValle (Tor.com)

“Meet Me at the Frost Fair,” Alison Littlewood (A Midwinter Entertainment)

“Bright Crown of Joy,” Livia Llewellyn (Children of Lovecraft)

“The Jaws That Bite, The Claws That Catch,” Seanan McGuire (Lightspeed #72)

“My Body, Herself,” Carmen Maria Machado (Uncanny #12)

“Spinning Silver,” Naomi Novik (The Starlit Wood: New Fairy Tales)

“Whose Drowned Face Sleeps,” An Owomoyela & Rachael Swirsky (Nightmare # 46/What the #@&% Is That?)

“Grave Goods,” Priya Sharma (Albedo One #6)

“The Rime of the Cosmic Mariner,” John Shirley (Lovecraft Alive!)

“The Red Forest,” Angela Slatter (Winter Children and Other Chilling Tales)

“Photograph,” Steve Rasnic Tem (Out of the Dark)

“The Future is Blue,” Catherynne M. Valente (Drowned Worlds)

‘‘October Film Haunt: Under the House’’, Michael Wehunt (Greener Pastures)

“Only Their Shining Beauty Was Left,” Fran Wilde (Shimmer 13)

“When the Stitches Come Undone,” A.C. Wise (Children of Lovecraft)

“A Fist of Permutations in Lightning and Wildflowers,” Alyssa Wong (Tor.com 03/16)

“An Ocean the Color of Bruises,” Isabel Yap (Uncanny #11)

“Fairy Tales are for White People,” Melissa Yuan-Innes (Fireside Magazine Issue 30)

“Braid of Days and Nights,” E. Lily Yu (F&SF, Jan-Feb)

The post Year’s Finest is Full appeared first on Marc Laidlaw.

December 8, 2016

@lantis…and Others On the Way

Rudy Rucker and I have been writing stories of surf-jerks Zep and Delbert since the mid 1980s, beginning with “Probability Pipeline” which appeared in George Zebrowski’s Synergy series in 1988. It’s a series, but we treat them like episodes in a comic strip, so not much carries over from one story to the next, other than the characters. They have changed over the years, but not much.

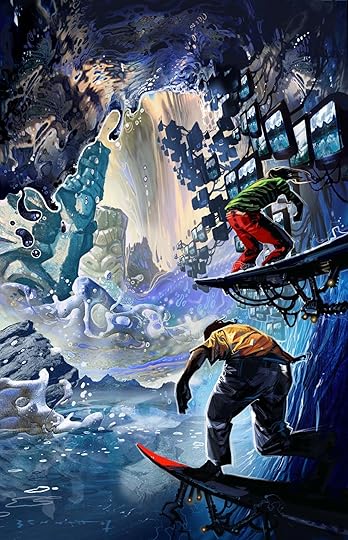

(Above is ‘s awesome Asimov cover illustration done especially for “The Perfect Wave.”)

This summer we had the chance to hang out together for a couple weeks, and started talking about doing another. Each one of these seems a little crazier than the last, and we had a lot of fun writing it. The end result just sold this week to Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (which published the previous two, “The Perfect Wave” and “Watergirl”).

It’s called “@lantis.” I will post more when I know the publication dates. (For the complete series, don’t forget “Chaos Surfari”…the only one to have a band named after it!)

I also finally finished the latest tale of Gorlen Vizenfirthe, the bard with a gargoyle hand. I wanted to do one substantial story that would round off the series so that I could put it aside, maybe collect all of them in a single volume, give those who’ve been following the series over the years a sense of closure. I might come back to it eventually, either to continue Gorlen’s story or plug some gaps in between the existing tales, but for now it seems a good time to put it aside and make room for completely new ideas. This one is called “Stillborne.” No news yet on where or when it might appear.

And finally, a very short story called “Vanishingly Rare,” emerged almost out of nowhere. Well, not exactly. I spent much of last year going through my papers, preparing to pack them up for donation to UC Riverside’s Eaton Collection. Out of that mass of notes, I pulled one self-contained fragment that had been intended as a piece of a longer work to be called (at last retitling) The Secret War of Photographs. I doubt I’ll ever do the long work at this point (the fragment was dated 11/26/90, so it’s probably past its expiration date), but I did hit on a way to turn the fragment into a complete short story. I will post when it has found a home!

The post @lantis…and Others On the Way appeared first on Marc Laidlaw.

October 17, 2016

Now Appearing on Great Jones Street

My story “The Finest, Fullest Flowering” is now appearing on an interesting new mobile app from Great Jones Street, which is devoted to delivery and discussion of short fiction. They hope to create something like a Netflix for fiction, but with more of a community aspect.

This link should connect to the app, where the story is featured.

The post Now Appearing on Great Jones Street appeared first on Marc Laidlaw.

October 6, 2016

Twisted: I Alone Am Escaped From the Floppies To Tell Thee

I sent several 5.25″ floppies to a service that scoured them for salvageable files. Most of what they found were documents of little interest or which I already possessed on paper.

This very short piece called “Twisted,” featuring Charles Dickens as an “eye in the sky” breaking news reporter, is the one exception.

I don’t remember anything about, but it seems quite self-contained and self-explanatory. The world was perfectly fine without it, but I’m happy to have rescued it.

The post Twisted: I Alone Am Escaped From the Floppies To Tell Thee appeared first on Marc Laidlaw.

October 3, 2016

Afterthought Overkill

[file dated 11/6-11/9/98]

Preface: This appears to be an expanded version of the “Day After Shipping” document, that was being written simultaneously. Ah, word processors, with your copypaste function making document provenance baffling. It incorporates big pieces of the other document, but is wrapped and shot through with a fair bit of new stuff. I think this was probably written to be presented at a CGDC Roadtrip—a smaller, local developer’s conference. I added “Anyway, as I was saying” sorts of things that made it sound more talky. But I don’t believe I ever got up and gave the talk. I recall I was on a panel about narrative in games, and might have spewed small chunks of it then, however.

Deep breath…

***

When I was about twelve years old, sometime around 1972, I wrote a few pages of a science fiction story about a futuristic form of entertainment. About all I remember is that it featured huge banks of lenses projecting holographic images into the middle of a round stage, and that the audience participated in the performance somehow. I recall making a big deal out of the futuristic-sounding words “three dimensional”—as if everything in 1972 were actually two dimensional, and we’d have to wait another 50 or 100 years for the third dimension to kick in. The story was supposed to be about this new entertainment industry, but since I don’t recall ever inventing any characters or conflicts or anything that might actually happen in the story, it didn’t get much beyond the planning stages.

But I find it interesting that in the 70’s, when I first really started grappling with all the possible ways of telling a story, the idea of immersive 3D entertainment was far more science fictional than the thoroughly mundane notion of riding rockets into space. Science fiction in the 70’s was all about mass media, and where it might be taking us—in some ways, a far scarier and riskier trip than any rocket ride.

Fast-forward, just over twenty-five years. Instead of a bank of glittering lenses, instead of a round central stage, there is one gleaming computer screen. Instead of an audience gathered in one place to watch the 3D performance, the audience is scattered all over the world, each of them with his own personal computer stage. Each one of them preparing to star in a drama that will be partially of his own making. They’ve finished the installation. They click their way through a set of menus using this weird futuristic device that no one in 1970 could ever have seen a need for—namely, a mouse—and suddenly it’s beginning. They’re barreling straight into the heart of the Black Mesa Research Facility, looking through the eyes of Gordon Freeman. They can’t yet feel or smell or taste what Gordon perceives; that’s a matter of degree and refinement and iteration—and perhaps a deadend that this industry will never want to explore. But in essence, the 3D future is now.

For me, I’ve come full circle, from that adolescent dream of an immersive artform, to the actual creation and even the marketing of that dream. Writing for Half-Life, and doing the other various odd-jobs that I did for the game, has been in many ways like living out a fantasy…an experience much richer and more rewarding, and also more demanding and challenging, than I could ever have envisioned. I think the future we’ve arrived at is much more interesting and full of possibility than we might have speculated thirty years ago.

Let me just get myself out of the way as soon as possible, since what everyone wants to hear about is Half-Life. I was loosely associated with the cyberpunks: I have a story in Bruce Sterling’s MIRRORSHADES, which remains the seminal cyberpunk anthology. My first novel, DAD’S NUKE, was written somewhat in satiric reaction to the wired, gritty urban visions of NEUROMANCER and its cousins. But I was not a very cyber writer, and not a very punk one either. My other novels include horror and fantasy titles among the satiric sf. A few years ago, I had a brief journalistic career, doing a fair amount of writing for Wired—mainly reviews of computer games. This culminated when Wired sent me on several trips to id Software, where I posed as a journalist to to document the making of Quake. You might remember the faces of John Carmack, Adrian Carmack, and John Romero lit up by Christmas tree lights on the cover of Wired a couple years back. In my own defense, at least I didn’t take the picture.

The time I spent at id was a revelation to me. It was the first time I had ever seen a team of highly talented, extremely creative individuals at work on one project. I found it absolutely irresistable. I was also heartsick because there was obviously no place at id for a writer. I had found the thing I wanted to do more than anything in the world right at that moment, which was to create these fantastic 3D worlds with John Carmack’s miraculous technology—and there was no place for me in it.

I guess it was right about then that I started scheming. I would either have to find a niche in that world, or carve one for myself.

Writing, however noble an activity, is a solitary one—especially the writing of fiction, where you sit in front of a typewriter or computer screen and feed on your own brain for as long as you can possibly stand it. I had collaborated on a few stories with friends, and those were great experiences. I had worked on a screenplay for a William Gibson novel, VIRTUAL LIGHT, and that was a group effort in the sense that armed resistance is a group effort. I’ll just reference all the cliches about Hollywood in a footnote. But what I realized when I got a look at id, was that after 20 plus years of working with myself, I was aching to work with other people—people whose artistic visions and abilities would give me a daily jolt of awe and inspiration.

Valve is precisely that place, and still is. It is less a job than an addiction. When I’m at work, I am engaged on almost every level, all the receptors are being stimulated. There is nothing more addictive than that. Every day at Valve I draw on the skills and intuitions I developed as a writer…and not only when I’m actually sitting down to work on a bit of dialog or some portion of a spec. It’s significant that an extremely tiny portion of my time is actually spent in the act of writing; and yet I continually draw on what I know about writing to solve the problems that come up in the process of developing a game.

Now, I like to be upfront about the fact that I don’t know very much about games. I missed most of the classics of this exceedingly young field, and unfortunately every time I go back to study one of them, I find myself in EMS/XMS, divide overflow hell. As an aside, this industry has a huge problem with long term memory, and is setting itself up for the industrial equivalent of Alzheimer’s, owing the fact that none of the classics are readily accessible to future audiences: The damn things just won’t run on new machines. This makes it extremely difficult for someone like me to go back and try to study the field and see what’s been done to death already, and what should be avoided. When I was learning to write, I read everything I could get my hands on—and especially the moldy old crappy old stuff. It’s important to learn what NOT to waste time on. The ability to wade through piles of ugly, obsolete crap should be the birthright of every young game developer. Otherwise they will be forced to create it for themselves, and we will continually be starting over again.

Anyway, as I was saying, I missed most of the classic computer games. It’s not that I wasn’t paying attention, but in my formative years, there was no such thing as a computer game. My first encounter with a computer didn’t occur until I was 20, and that one filled a small building at the University of Oregon. Those who brag about building Quake maps with a text editor…how much prouder they’d be if they’d had to compose their maps on punchcards, using an input device that was a frightening hybrid of typewriter and jackhammer.

So I can easily list the games that have had an influence on me or taught me something about the possibilities of storytelling in this new form: Myst showed me that books and movies had lost their exclusive domain over my imagination; it did what my favorite stories did—it cast a spell—and I knew I wanted to learn how to cast those spells myself. Ecstatica and Relentless taught me a bit about how one might embed narrative elements seamlessly in an action environment without compromising either…I saw no reason that what these games did in the third person could not be done in first person. Gadget was less a game than a new, even more immersive form of graphic novel, and the chances it took, the intelligence it represented, completely awed me. The id-family of games, including Quake and Doom, Hexen and Heretic, introduced me to the virtues of a highly addictive, frenetic style of gameplay that bypassed intellect completely and went straight for the throat. I have always liked entertainment that goes for the throat. So…this is not much—it’s nothing at all, compared to the number of games played since childhood by most of my cohorts at Valve. So most of what I know about developing games doesn’t really have much to do with games—and yet, certain things are universal. At least, in working on Half-Life, I found them to be so.

Working by yourself, writing on your own for a long long time, teaches you some really valuable things about the nature of the creative process. Because you’re working alone, you get to pay a lot of attention to every part of the process. It’s like hiking in the mountains all alone: You think about every step you take, and everything you see, and it all sinks in a bit more deeply because there’s no one else there to distract you, no unrelated chatter. After writing a few novels, you start to recognize certain distinct milestones which invariably appear at certain points during any lengthy project. You learn a lot about intuition and inspiration. You learn a lot about trusting in things you can’t quite put into words. Most of the big projects I’ve worked on began with a lightning strike of inspiration, a strong vision that seemed seductively easy to accomplish; and yet invariably somewhere in the middle you lose sight of the final goal and the original vision. You see nothing but chaotic details that may never cohere into anything worthwhile. You lose hope; you lose all sense of perspective; and it is very easy at this point to give up. However, knowing that this middle stage is inevitable, and even a necessary part of the maturation process, you learn to just keep doing the work, to keep on until you get to what you think is the end, so that you can finally realize it’s not the end at all but simply the next place you have to start from.

Specifically, here’s what I did on Half-Life.

When I arrived at Valve in July of 1997, the game was “almost finished,” as befit something that was supposed to go on sale for Christmas. I was supposed to put in a couple weeks of work putting finishing touches on the Half-Life story, and then I would get right to work on a far more detailed storyline for Valve’s second game, which was completely unrelated to Half-Life and something in a very different mode. I loved what I had seen of Half-Life, but I mainly expected to work on that second game, where we sat around talking about Borges and Tesla and Escher. Gradually, Half-Life took over my life, and I’m glad it did so.

Half-Life in the summer of 1997 bore only superficial resemblance to the Half-Life that just went gold. It had a storyline involving an accident at a decommissioned missile base, a dimensional portal experiment, lots of smart alien and human enemies, and a bonus trip to another world. There was a storyline in the spec, but it was not terribly evident in the maps that had actually been built. I was reminded of a shared world anthology. These are a popular form of short story collection, where some one or couple of people get together and come up with a basic background, such as Thieves World, and then a dozen writers are asked to write stories sharing that background. There may be overlapping characters and some slight reference to events in other stories, but overall each story is a distinct and separate performance by an individual writer, and they had only the loosest association with one another. That was how Half-Life struck me when I first saw it. There was an experimental portal device, several silos, some train tunnels, and nuclear reactor, and miles of corridors and airducts. I thought there must be some grand scheme that united all these interesting fragments, and it took me about three months to realize that maybe, just possibly, there…wasn’t. Every level designer was telling a different story. Half-Life was a shared world anthology, when what we really wanted was a coherent, unified novel.

It took me several months just to figure out what I was doing at Valve—and how I could possibly contribute. Our maps were a confusing collection of things named c1a1c, c2a3b, c3a2; so it was difficult for me to follow even simple conversations. “I was just looking at c2a4a and I saw that you had a piece of c1a2c next to something that belongs in c2a1a.” By the time I had just started to figure out the connections between all the levels, and was wondering how to pull the loose Half-Life story together into something fairly taut, Valve reached a general consensus that the entire game as it stood was in need of severe reworking. At Thanksgiving, just when we should have been in the stores, we decided to tear the existing game down to its elements and more or less start over again.

This is the point where I began to find my writerly instincts coming in handy. I am extremely comfortable with the process of selection that comes about during revision. As a member of the so-called Half-Life Cabal, we started working our way through the entire game, figuring out what worked, what was new and interesting, and what probably would never work as we had hoped. When we were down to a few basic elements that seemed to work, we started fleshing them in with new material. It was in some ways an extremely painful process—both because we knew that the game was going to slip far longer than anyone liked, and because it meant that a great deal of work was going to be lost and probably never seen again. As a writer, passing judgment on my own work, it’s hard enough to decide that pages and pages of text probably don’t serve the story and ought to be cut; but at least I have only myself to answer to. But cutting someone else’s work is never fun.

I have been very lucky in my writing career to have had not one but several excellent editors. At Omni Magazine, at St. Martins Press, my editors were not shy about telling me when something I’d written didn’t work. But they didn’t stop there. They seemed to understand what I was trying to communicate, rather than what I had succeeded in communicating. When they gave comments or criticism, it was always aimed at getting me closer to satisfying my own goals, rather than their editorial agendas. I really tried to do this in working with the level designers. We had specific goals for the game, things we expected Half-Life to deliver, but apart from that I understand that level designers have their own unique talents and interests. And wherever possible, the game benefitted from trying to match the designer’s strengths and artistic goals with the needs of the game. Once we moved beyond redesigning the game on paper, and the level designers got to work revising their levels or creating new maps, we commenced a process of working very closely with the designers. I tried to think back to my editors, and how they always encouraged me to do what I did best—and to discover new strengths which they sensed, but which I perhaps didn’t always know I had. This was my philosophy in working with the level designers.

Somewhere along the line, I was asked to take on the role of lead for the level team. This was really an ideal place from which to watch the story taking shape. The designers were so busy, nose to grindscreen, that they rarely had time to give much in-depth consideration to what the other designers were up to. It became my job to look at everyone’s work on a daily basis, and make sure that people were moving in synch, that an area at one end of the game did not conflict with an area at the other end. The designers were constantly inventing details that amazed me, things that weren’t in the spec but which just seemed right for the story—things which seemed to magically click with something a designer down the hall had just invented independently. I had experienced this kind of spontaneous invention enough times on my own, in the process of writing a story, to know that finally we were on the right track. We were still buried in fragments, in midstream, but I felt that we would soon have our first draft…our rough mockup of the entire game. That was a crucial milestone for me, because I knew that once we got to that point, we would be able to really see what we were trying to do. We would be able to decide much more pragmatically what elements belonged in the game, and which things just did not fit. This was something I knew from writing novels, and in fact it worked out much as I had expected.

Once we had finished up the first pass on the entire game, we found it possible to sit down and tighten up specific areas—cutting complete sections, adding new ones. As well, the process of adding scripted sequences and setting up dramatic gameplay, suddenly became much easier. Designers were able to work on their level with increased confidence that the work they were doing would actually end up in the game, and be an important part of the story. Needless to say it had been extremely disheartening for some when their levels were cut. Now, instead of cutting, we were able to get into the mode of improving and elaborating on existing material.

In a novel, it’s a common technique to pick up one isolated image and try to work variations on it elsewhere in the story—it creates a thread of meaning and metaphor which is so much richer than if you leave only the one instance. This kind of polishing usually happens most effectively in the rewrite stage. I was really gratified to see the same things happening in Half-Life. One of the cleverer constructions in Xen, our alien dimension, is a series of puckered orifices which swallow you and spit you high into the sky for a lethal fall. These were picked up by one of the other designers and worked back into the terrestrial levels, immediately giving the impression that the earthly plane is being infested by the alien one. This was further elaborated on when a third designer did active earthly versions which fling you one or two stories high. So the puckers went from being a localized trap to become an important element of gameplay for a significant part of the game. This kind of borrowing and scattering of imagery is to me one of the most effective things that happened spontaneously in the creation of Half-Life. It happened opportunistically, because it made sense at the moment, but it enriched the game a great deal.

So, as writer, was I responsible for this level of invention? No. Did I encourage it because it made sense for the structure of the game overall? Hell yes. In fact, staying on top of the constant inventiveness of the level designers was a fulltime job. Because they were in there working on the details of the game on a daily basis, this meant the story itself shifted in minor ways from day to day. Actually, the story shifted in major ways more often than I can recall. Several times we had Valve-wide meetings where I would tell the entire story of the game as we understood it from beginning to end, so that everyone would be on the same page as we went forward. But invariable, as soon as those meetings were over, I’d find the story changing again. We’d discard the ending, we’d eliminate a central element, we’d cast everything in a new light. It became impossible to keep everyone continually apprised of how the story worked itself out. Again, I was used to this kind of behavior; it more or less describes the writing of every novel I’ve worked on…but leading a team of people through this state of perpetual reorganization was unnerving. I think most of the designers were so busy worrying about the details that they didn’t have time to think about the big picture, and counted on a few of us to keep the grand scheme in mind.

There were quite a few grand schemes which were tried out and discarded in the course of settling on the game we ended up with. Before I arrived at Valve, there was a fair amount of talk about how there would be no bottlenecks—how you would be able to run from one end of the game to the other and all the way back again. This was to have been a feature, and certainly it would have been a very easy one to implement. But I failed, and still fail to see how this could have made the game any better. All drama, all narrative, relies on pacing and rhythm; horror is especially dependent on getting things set up just right for the audience, so that you can spring your little traps at opportune moments. By choosing to let the player run in any direction at any moment, we would have been choosing to let our story go right out the window. Half-Life begins on the morning of one particular day, it continues through that day, through the next night, and far into the following day, before breaking on into a place where time ceases to have any real meaning. Say it were possible to turn back at the end of the second day and run all the way back to the point where you had started two days ago. First of all, you would miss the climactic moment we’d set up for the end of day two. You would arrive (many many hours later) at the place where everything had begun. There would be some monsters there, some moss might have grown on a wall, but not much in the way of drama would await you. We really wanted players to have a structured narrative experience, and time and trial have basically proven that the most satisfying narratives are linear. I was a huge champion of keeping our story linear. I don’t think I would have known how to deal with a nonlinear narrative the first time out. It’s extremely hard to handle well in fiction, where the tools are far more flexible.

I was also a champion of avoiding third person cut-scenes and cinematics altogether. I came into Valve with a deep-seated prejudice against cinematics. My feeling was that if we were going to do a first person game, we should stay first person the entire time, so as to never break the narrative spell for the player. Ironically, I soon began to bend from this rigid stance, especially when I saw how difficult it was to create scripted experiences for the player that they absolutely must not miss. I became a reluctant advocate of the camera; and in fact our developers implemented an absolutely beautiful camera system which made me want to do a third person camera kind of game. But the more we worked with our scripted sequences, the more we discovered we could do without a camera. Once we saw how well the opening disaster worked from first person, we realized that we would not be using the camera at all, anywhere. I was all too happy to go back to my original prejudice. For Half-Life, the third-person camera would have been a cop-out, and I am very glad we managed to avoid it.

Actually, another reason we avoided it was because we really had no good place to introduce it. If we were to use the camera at all, we should have used it in the very opening scene, when Gordon Freeman boards the personnel train. You’d let the player have a look at the player they were inhabiting, and then you’d zoom down into his eyes and lock into first person. The problem was, our only Gordon Freeman model was wearing a hazard suit, and he didn’t actually put that on until the game was well underway. We could have cut to our camera when he stepped out of the changing pod, fully dressed, but that would have been a really undramatic way of introducing him. Ultimately, we just never found a very good or necessary place to introduce the camera, and we kept pushing it back farther and farther until it was out of the game.

This introduced an interesting challenge. How could we create a real character for our game, when you never saw the guy and he never uttered so much as one word? Well, we let the player answer that question for himself. You start the game knowing very little about the character you play; but apparently everyone around you knows who you are. Between the player’s ignorance and the NPCs’ knowledge of Gordon Freeman, something very interesting happens. Players create their own version of Gordon Freeman—one they can completely identify with. There is literally nothing to jar you out of Gordon, once you’re in the game. He never says anything stupid that you would never say in a million years. He never does anything you wouldn’t do—since you control all his actions. He becomes a hollow receptacle into which every player can pour himself. In a sense, he’s an everyman.

This makes traditional character development a bit problematic. We create an experience for the player as Gordon—one that has a beginning, a middle and an end. We provide a lot of clues for the player to ignore or pick up on as they choose. From this, they can put together a picture of what is “really” going on in the world of the game. And by the end of the story, they will have played some unique version of Half-Life which is meaningful to them in a different way than it is to anyone else. Some people want Gordon to speak; they want to run through lists of possible questions and converse with the NPCs. I think if we had provided a voice for Gordon, and lots of conversational gambits, they would have had a very different experience…and not necessarily a better one. I’m very happy with the choice we made to let people create their own protagonist.

It has been extremely satisfying to note the reactions of players to the story itself. Before beginning work on Half-Life, I heard a lot of comments to the effect that a first person shooter didn’t need a story—that the players didn’t want one, and that anything more complicated than a bunch of moving targets and some buttons to push would be lost on them. The reaction from hardcore gamers has been exactly the opposite. If anything, what people seem to want is more story—story that is integrated into the action, story that matters. It’s something that you’re often taught in writing prose, but you should never condescend or write down to your supposed audience. There has been a lot of condescension toward gamers, I believe—both from those looking at the field as outsiders, and from those who are actually creating games. The former is understandable, the latter unforgivable. Computer games currently occupy a niche of poor reputation previously held by pulp fiction and comic books: A form of mass entertainment whose appeal is supposedly lowbrow and unsophisticated, presuming an audience that wouldn’t recognize quality if it were available. It would be impossible to list all the excellent, unforgettable stories that were originally published as pulp. There is not much we can do to change the fact that games may be regarded as lowbrow entertainment by the so-called mainstream, but we can make sure we don’t fall into this trap of thinking about ourselves. When writing for computer games, you should abide by the same principles and virtues that distinguish and elevate any kind of traditional entertainment. The great thing about working in such a new medium is that tradition is not a limiting factor but simply a springboard into creating new kinds of experiences which our audience has never had before.

My thinking about game design is constantly in a state of creative tension between tradition and experimentation. When I think of our main character, Gordon Freeman, as a kind of conduit for the player’s self-invented identity, I can’t think of a literary or cinematic equivalent. That right there excites me immeasureably. How often does a writer get to work with tools that are completely untried? The early history of literary and cinema is already written. For any writer who wants to know what it feels like to pioneer—this is the place to be.

Now I’ve been describing a job that involves a lot of thinking about story and structure, but very little actual writing. I think that’s fairly important. The writing I did was done in snatches, when needed, and often to satisfy the demands of a particular scene that we had invented on the fly. I don’t believe a freelance or contract writer would have been much use on Half-Life. Writing the story is not something that was all done up front and never revisited, and being tied to a fixed story with no writer on-site would have been crippling to the project. This leads me to believe that certain kinds of writers probably are a better fit for game companies than others.

First, you probably want someone who is interested in absolutely every aspect of game design. I think a lot of writers fall into this category: Interested in everything. Being curious and interested and perhaps even knowledgeable about all sorts of things is at least as important as what you know about games. Curiosity is just a basic starting point for any enterprise. Even though I never played a computer game until I was in my 30’s, I am intensely curious about everything that goes into creating game. I love the point where art and technology intersect, and nowhere is this point of fusion so alive and easier to access than in game design. This is living, breathing science fiction. It’s the frontier. It’s the thing I caught a whiff of there in id’s offices, which started me on the invisible trail that led me here today.

There are a million and one things to do in building a game, and only a tiny percentage of them involve putting one word after another. It helps if you’re willing to wear the managerial hat for a while, if called upon to do so. It helps if you have worked in other businesses, so that you will understand something about how people ought to treat each other in a professional workplace, and will know in advance some of the pitfalls of office politics which are the same whether you work in a game company or a utility company. It also helps to have had some absolutely terrible, soul-numbing jobs, so that you will never take for granted your job in a field that thrives on innovation and creativity. It helps if you know enough about level design to do some rough mock-up work to test out ideas before inflicting them on the real level designers. I did some of that. I also helped do some really minor editing of wave files when we had a thousand lines of dialog to process and two days in which to do it.

Everyone designing a game really, really, really needs to understand the limitations and advantages of their technology, and that’s something no freelance writer sitting at home a hundred miles away from the developers can readily come to terms with. I proposed hundreds of story ideas that would never have worked in Half-Life. Because I was able to see at first hand on a daily basis what worked, I stopped proposing certain things, and started thinking in terms of expanding upon proven features. There is nothing like having a level designer laugh in your face to convince you that there must be another way of doing something.

This mass of hard-won, odd little insights was probably the most valuable thing I brought with me to Valve from my writing background. It is also probably the hardest thing for a game company interested in hiring a writer to evaluate in a prospective employee. It is very, very easy to represent yourself as a professional writer; but it is not very easy to tell exactly what this means. Professional does not necessarily mean good. And a good writer may not necessarily be a good fit at a game company. Some writers absolutely need the solitude of their profession, and would feel terrifically compromised to be part of a team. I assume this kind of writer is never going to seek work at a game company. The way it worked between me and Valve was that they squinted sidelong at me for awhile and I repeatedly made eyes at them while trying not to appear too desperate. In evaluating a writer, you should always read what they have written.

Valve’s owners endured the clumsy Quake maps I submitted, but mainly they read my books and were able to judge my abilities based on the record. I would add that whoever judges the writer should be someone who actually reads a lot and can tell the good stuff from crap. If you’ve got one person at your company who reads and reads and reads, loves reading as much or even more than they love games, that is the person who should evaluate the writing of the prospective writer—even if they’re not the person who will make the hiring decision. It takes a reader to judge a writer.

The post Afterthought Overkill appeared first on Marc Laidlaw.

Writing For Half-Life

(File dated November 9, 1998)

PREFACE: Another file from the same disk with the Nihilanth sketches, this one, if it is to believed, written the day after we shipped Half-Life. I do believe it because the file’s creation date is indeed November 9, 1998, and I am not l33t enough to know how to fake that sort of thing. The title of this file was “CGDCTALK” but I don’t remember ever giving a talk anywhere until years later, after the success of HL2. It might have been published somewhere (perhaps near Geoff Keighley’s piece on The Last Hours of Half-Life), but if so it was probably edited, and there might be some value in the unedited braindump. If this was indeed written right as we shipped the game, then I would not be surprised if it conflicts with things I’ve said in decades since. But the guy writing this little article was there, and his memory is much better than the old guy writing this preface, so I’d be inclined to believe him over me.

***

When I started working at Valve, Half-Life was almost finished. It would be on sale for Christmas. If I was lucky, I would get to put in a few weeks of touch-up work on the story, and then get on with a far more detailed storyline for our second game. That was in July of 1997.

Yesterday afternoon, just as the sun was setting on Kirkland, Gabe Newell took a crowbar to a headcrab pinata which had been dangling in Valve’s main room for several weeks like the headcrab of Damocles, waiting for Half-Life to go gold. As rubber bugs and monopoly money sprayed the room, I knew that I was finally finished working on the story for Half-Life.

Between July 1, 1997 and November 8, 1998, it seems to me that every day has been somehow occupied by Half-Life. I’m sure this is an exaggeration—but not much of one. If my memories are distorted, it’s because the world of Half-Life created such an intense and powerful gravity well that everything that came anywhere near it was inexorably drawn in until it was bent beyond recognition. I know the game put me through quite a few twists and turns before it was finished, and I can only hope it does the same for its audience.

Half-Life in the summer of ‘97 bore only superficial resemblance to the Half-Life that just went gold. There was a storyline in the spec involving an accident at a decommissioned missile base, a dimensional portal experiment, lots of smart alien and human enemies, and a bonus trip to an alien world. But when I looked at the game itself, it was not terribly obvious where or how this story was ever going to get told. My first detailed view of the game reminded me in literary terms of a shared world anthology. In a shared world anthology, some author or editor comes up with a basic background, such as Thieves World, and then asks a dozen other authors to write stories sharing that background. There is some obligatory overlap of characters and casual reference to events in other episodes, but overall each chapter is a distinct and separate performance by an individual. So it was with Half-Life. There was an experimental portal device, several silos, some train tunnels, a nuclear reactor, and endless miles of corridors and air ducts. They were great sets, but it was not at all clear what kind of continuing drama could ever unfold against them. Half-Life was still an anthology, when what Valve really wanted to create was something with the coherence and unity of a novel.

As a novelist myself, I hoped that I could provide some guidance to a team that was already well on the way to creating what had been from the beginning an ambitious game of great promise and epic scope. There was really no magic formula, and I had nothing but intuition and experience in a completely different medium to guide me. But that seemed appropriate, somehow, since Valve was doing something for which there were no previous examples. If we did it wrong, we would never know how near or far we had come to whatever the right thing was. But if we did things right, we would all know. And we would finally have our example.

Before coming to Valve, I had published half a dozen novels and scores of short stories. I was lumped in with the cyberpunks, and got to watch that little popular revolution from somewhere near the front row. I had written screenplays, dabbled in journalism, and lately I had started playing lots and lots of computer games. Playing them, yes, but also studying them. Trying to figure out what made them tick. I wasn’t exactly tired of writing prose, but I had been doing that and little else for more than 20 years, and my muse kept pointing me down other roads. I found myself making Quake maps for my own amusement. I found myself working for id, writing their company history, wishing I could be a part of it somehow.

The time I spent at id was a revelation to me. It was the first time I had ever seen a team of highly talented, extremely creative individuals at work on one project. I found it absolutely irresistible. I was also heartsick because there was obviously no place there for a writer. I had found the thing I wanted to do more than anything in the world right at that moment, which was to create these fantastic 3D worlds with John Carmack’s miraculous technology—and there was no place for me in it.

I guess it was right about then that I started scheming. I would either have to find a niche in that world, or carve one for myself.

I had originally come to id on assignment from Wired magazine, writing a cover story about the making of Quake. By coincidence, that magazine had just appeared on the newsstands when Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington were making their first trip down to id’s offices to discuss licensing the Quake engine for their start-up game company. Mike and Gabe were old associates of Michael Abrash, another ex-Microsoft employee and now one of id’s more high profile programmers. Abrash was the one person at id who proved endlessly willing and able to translate what John Carmack was up to into terms that I could understand and convey to the readership of Wired. We became friends, and the first time I heard about Valve, it was from Michael. I was agonizing because I had been offered a writing job at IonStorm, and I just couldn’t bring myself to move to Texas. Michael consoled me with vague hints of other possibilities, including one in the Seattle area. I knew they had licensed the Quake engine, which was the only technology that really interested me. I couldn’t understand why someone didn’t take the best engine they could get, namely Carmack’s, and use it to tell fantastic first-person 3D stories. Needless to say, when I finally got a look at what Valve was up to, I felt an immense cosmic click.

Writing, however noble an activity, is a solitary one—especially the writing of fiction, where you sit in front of a typewriter or computer screen and eat your own brain for as long as you can possibly stand the taste. I had collaborated a few times with friends, and those were great experiences. I had worked on a screenplay for a William Gibson novel, and it being Hollywood and all, that was a group effort in the sense that armed resistance is a group effort. But when I saw the group at id, I realized that I was aching to work with other people—people whose artistic visions and abilities would give me a daily jolt of awe and inspiration.

Valve is precisely that place. When I’m at work, I am engaged on almost every level, all the receptors are being stimulated. Every day I draw on the skills and intuitions I developed as a writer…and not only when I’m actually sitting down to work on a bit of dialog or some portion of a spec. An extremely limited portion of my time is actually spent in the act of writing; and yet I continually draw on what writing fiction has taught me to solve the problems that come up in the process of developing a game.

One of the best things about working alone is that you get to pay a lot of attention to all the subtleties of the creative process. There’s no one else to distract you. It’s like hiking in the mountains by yourself. You notice every step you take; every birdsong registers a bit more clearly because there is no one else there talking. Well, after writing a few novels with no other company than the characters you create, a writer starts to recognize certain milestones along the seemingly endless road between page one and THE END. Every novel I’ve ever written began with a jolt or even several jolts of inspiration. These overwhelming visions are usually so vivid as to be unforgettable, and yet somewhere along the way you inevitably lose sight of them. In the midst of creation you see nothing but chaos and dim glimmers of sense. You lose all perspective; you may even lose hope. It is very easy at this point to give up, and I have. However, if you keep on, you will learn that the floundering feeling of the middle game is temporary, and may even serve some purpose in causing you to question and test your assumptions. A book that makes it through the doubts and revisions of the middle stage is a stronger, more complex and curiously more stable book, I believe, than it would have been without the reevaluation. Still, it’s a hellish process, even when you’ve weathered it more than a couple times. You learn to keep doing the work. You keep on until you get to what you think is the end, so that you can finally realize it’s not the end at all but simply the next place you have to start from.

I am talking of novels, but the same applied to Half-Life. Maybe it applies to every work of real creativity.

It took me several months just to figure out what I was doing at Valve—and how I could possibly contribute. Our maps were a confusing collection of things named c1a1c, c2a3b, c3a2; so it was difficult for me to appear even remotely intelligent when people asked me things like, “What did you think of c2a4a?” By the time I had finally figured out the difference between c2a3 and c3a2, and was wondering how to pull the loose Half-Life story together into something fairly taut, Mike and Gabe decided that the entire game was in need of reworking. At Thanksgiving, just when we should have been bashing open headcrab pinatas, we took a crowbar to the game itself. The floor of the office was strewn with Half-Life components. We tore the game to pieces, trying to determine what worked, what might work someday, and what would probably never work given what we knew about our abilities. It was in some ways an extremely painful process—both because we knew that the game was going to slip far longer than anyone liked, and because it meant that a great deal of work was going to be lost and probably never seen again.

Now, I personally I enjoy revision, and the refinement of purpose that comes about during the rewrite process. But suggesting revisions to a collaborator is always much touchier than simply carving up one’s own work. Every piece of the game we discarded represented the work of some artist or programmer or level designer. I’ve been lucky enough to have had several excellent editors, and none of them has ever been shy about telling me when I wasn’t doing my very best work. But none of them has ever stopped at mere criticism either. A good editor tries to understand where things went wrong; a good editor can work miracles in getting a story back on track, by giving a few thoughtful comments to the writer. I tried to follow these examples when it came to working with level designers. We certainly had specific goals for the overall game, some things we expected Half-Life to deliver, but apart from that each designer has his own talents and interests. Wherever possible, the game benefitted from matching the designer’s strengths to the needs of the game. We have designers who excel at the broad plan, laying out huge complex areas in a few breathtaking strokes; and others who really go into high gear once the architecture has solidified, and they are able to set up finely balanced dramatic situations using monsters and triggers and scripted sequences. Half-Life benefitted immensely when we recognized and reorganized the workflow to take these differences into account. In the last few months of content creation, very few designers were solely responsible for maps they had originated.

As we moved beyond redesigning the game on paper, and into the mode of implementing our changes, I was asked to take on the role of lead for the level team. This was an ideal place from which to contribute further story elements to the game, and to make sure that all the various parts of the game interlocked as we knew they must. The level designers were so busy, nose to grindscreen, that they rarely had time to give in-depth consideration to what the other designers were up to. But I could look at everyone’s work on a daily basis. The designers were constantly inventing details that amazed me, things that were not in the spec but which belonged in the story. I had experienced this kind of spontaneous invention often enough in writing to feel that finally we were on the right track.

The crucial milestone for me was the completion of our first rough mock-up of the entire game—in essence our first rough draft. I knew that once we could move through the maps from beginning to end, without cheating, we would all discover a new vision of the game. Something closer to the final vision. This was something I believed very strongly, based on my experience as a writer. First drafts exist only to teach you what you really want to accomplish.

It was true enough in Half-Life’s case. Once we had finished up the first pass on the entire game, the process of adding scripted sequences and setting up dramatic gameplay suddenly became much easier. Designers were able to work on their levels with increased confidence that the work they were doing would actually end up in the game. Now, instead of cutting, we were able to get into the mode of improving and elaborating on existing material.

In a novel, it’s a common technique to take an isolated image and work variations on it elsewhere in the story. This creates a thread of meaning and metaphor which is much richer than if you leave only the one instance. I was really gratified to see something of the sort happening in Half-Life. One of the cleverer constructions in Xen, our alien dimension, is a series of puckered orifices which swallow you and spit you high into the sky for a lethal fall. These were picked up by one of the other designers and worked back into the terrestrial levels, giving the impression that the earthly plane is being infested by the alien one. Then a third designer did more benign earthly versions which fling you one or two stories high. So the puckers turned from a localized trap into an important gameplay element for a significant part of the game. This kind of borrowing and scattering of imagery is a function of revision, and to me one of the most effective things that happened spontaneously in the latter stages of Half-Life’s creation.

But was I, as the person in charge of the story, responsible for this level of invention? Not at all. Did I encourage it? Hell yes. Keeping up with the constant inventiveness of the level designers was a fulltime job. Because they were working on the details of the game on a daily basis, the story itself kept shifting from day to day.

Several times we had Valve-wide meetings where I would tell the entire story of the game as we understood it from beginning to end, so that everyone would be on the same page as we went forward. But invariably, as soon as those meetings were over, we’d find some reason to change the story yet again. We’d discard the ending, we’d eliminate a central element, or introduce a new one. It became impossible to keep everyone continually informed on the state of the story. Again, I was used to this kind of fluctuation; it more or less describes the writing of every novel I’ve worked on. I would have been happy enough to reassure everyone else that this state of perpetual disarray was normal, but no one seemed too bothered by it. And as we drew closer to our deadlines, everyone became so busy with their parts of the Half-Life universe that they rarely had time to think about the big picture. Everyone assumed that someone else was keeping track of the grand scheme. I was the only person who wasn’t allowed to assume that.

We tried out and discarded quite a few grand schemes. Some of you may remember, as I do, early talk about how there would be no bottlenecks in the game; how you would be able to run from one end to the other and all the way back again. This would have been a very easy feature to implement, given the nature of our transitions, but I was very relieved when we jettisoned this notion. Total freedom for the player would have meant a total loss of dramatic suspense. All narrative forms of drama, but especially horror, rely on pacing and rhythm. In horror timing is crucial. You have to set up your traps just so, and wait until your victim is precisely in position. There’s nothing worse than springing them a moment too soon or too late. This would have been virtually impossible to control in a nonlinear game. would have been choosing to throw all suspense right out the window. We really wanted players to have an artfully structured experience, and time and trial have basically proven that the most satisfying narratives are linear.

I was also a champion of avoiding third person cut-scenes and cinematics. I came into Valve with a deep prejudice against cinematics. My feeling was that if we were going to do a first person game, we should stay in first person the entire time, and never break the narrative spell or jar the player out of the story for even a moment. Midway through the process, I became a reluctant advocate of the camera. Some of us were convinced that important scripted sequences would only work if we could lock the player into position. Our developers implemented an absolutely beautiful camera system which I’m sure the mod-authors will enjoy, but as it turned out, we only used it once, and when we did it was to simulate a first-person viewpoint and further deepen the spell we were trying to cast. There were a number of critical scenes in the game which we couldn’t quite envision doing without a camera, one of the key scenes being the disaster that really sets the story into motion. We had recorded all the audio leading up to the disaster; the voices were wonderful, the test chamber was impressive, but the main event itself was still a mysterious void known simply as The Disaster. Due to time constraints, The Disaster had gone from being a developer’s problem to being a level designer’s problem. Some of us spoke of a third person camera solution, but nothing was settled. I remember I went home on Friday and The Disaster was still an act of faith; someone else would make it happen. And someone else did. On Monday morning I came in and I could hear people all around me in the office playing the opening disaster over and over again. I held off as long as I could. When I watched it, my hair stood on end. It delivered the final blow to the third-person camera. Having seen that we could pull off the Disaster in first person, it was obvious that we should be able to do just about anything we could think of within the limits we had set for ourselves. So we went first person all the way.

The one noticeable casualty of the camera’s elimination was the absence of Gordon Freeman himself, our main character, as a visible presence in the game. Apart from the loading screen and the multiplay menus, and on the box itself, you never get to see Gordon Freeman. This introduced an interesting challenge. How could we make a real character out of someone you never saw, and who never uttered so much as one word? Well, we let the player solve that problem for himself. You start the game knowing very little about Gordon; but apparently everyone else knows you who you, and they fill you in on their expectations. In the gray zone between the player’s ignorance and the NPCs’ knowledge of Gordon, something rather interesting happens. Players create their own Gordon Freeman—a character they can identify with completely. There is nothing to jar you out of Gordon, once you’re in the game. He never says anything stupid that you would never say in a million years. He never does anything you wouldn’t do—since you are behind all his actions. He becomes a hollow receptacle into which every player pours himself.

This flexibility makes traditional character development a bit problematic. We create an experience for the player—a story that has a beginning, a middle and an end. We provide plenty of clues from which the player, if he chooses, can construct an explanation for what is really going on in the story. And by the end of the game, every player will have experienced some unique version of Half-Life which is meaningful to them in a different way than it is to anyone else.

Before beginning work on Half-Life, I encountered a lot of comments to the effect that a first person shooter didn’t need a story—that hardcore gamers didn’t want one, and that anything more complicated than a bunch of moving targets and some buttons to push would be lost on them. The reaction from our audience has largely contradicted this. If anything, what players seem to want is more story—but story that is integrated into the action, story that matters but doesn’t bog you down. It should go without saying that a boring story is a bad story, and that writing for a medium which is not considered “literary” is no excuse for creating boring or otherwise terrible stories. If gamers don’t like the bad stories they’ve been offered, the gamers themselves are hardly to blame.

Anyone writing for computer games should start off recognizing the principles and techniques of drama that give impact and meaning to traditional forms of art—start there, but by no means stop there. The great thing about working in this new medium is that tradition is not a narrow set of restrictions, but a proven springboard. With a solid foundation in traditional storycrafting, I believe we are in a better position to create totally new kinds of experiences which our audience—any audience–has never had before.

My ideas about game design are in a constant state of creative tension between tradition and experimentation. When I consider our main character, Gordon Freeman, as a conduit through which a player invents an identity for himself, I can’t think of a literary or cinematic equivalent. That right there excites me immeasureably. How often does a writer get to work with tools that are completely untried? The early history of literary and cinema is already written. For any writer who wants to know what it feels like to pioneer—this is the place to be.

The post Writing For Half-Life appeared first on Marc Laidlaw.

Mathoms from the Lambda Files (c. 1998)

PREFACE: For the past few months, as part of my post-retirement purge, I’ve been organizing papers, rummaging in drawers, going through the basement, getting rid of moldy paperbacks, looking for the occasional piece of debris worth saving. At the end of the process I ended up with a stack of 3.5” floppies, so I bought an external floppy drive to see if there was anything on them worth saving. Mostly they held back-ups of old manuscripts and story fragments from before I joined Valve, but on one disk I found several documents from the summer of 1998, late in Half-Life 1’s development, when I’d been working on the game for a year.

The first one is called “Finale” and appears to be an attempt describe the whole final sequence, which makes it pretty clear that we didn’t have an ending built yet. Another interesting thing is that it ends with a third-person cut-scene view of Gordon Freeman. As I’ve stated before, we only committed completely to first person when we realized we didn’t have time and resources to do a good job with third person views. Resource constraints forced our hand and gave the game its strict first-person integrity. It was all very seat-of-the-pants.

Note the confused naming convention as well. I think Nihilanth and Overmind both refer to the same thing. We didn’t have a settled name or even a monster. Nothing had been modeled yet, as I recall.

I present these as curiosities. These are not necessarily things that might have been, these were just sketches I wrote and threw out there to see if any of the ideas might stick. Level designers didn’t necessarily read them, they kind of just kept building what they thought would be fun and, more importantly, possible. Building with words, everything costs nothing, so you can make anything.

***

FILE 1: “FINALE”

[created 6/4/98, last edited 7/21/1998]

You step out from between dark towers into the glowing core of the Nihilanth’s power. At first all you notice is the Nihilanth itself, a supreme and supremely tortured intelligence, suspended in space above a bottomless abyss. It begins to drop toward you, as if you were worth noticing; and you shrink back in fear, for you are weak and nearly defenseless after your ordeal in the Gonarch’s den. As it descends, an alien pulse or heartbeat begins to toll—slowly and softly at first, but gathering intensity. But then you see that it is coming not for you, but for something which is emerging from the open portal down below.

Two Xen Masters, their bulbous heads gaping in the presence of their living god, rise up with a struggling morsel trapped between them. It is a suited figure like yourself—a scientist, probably, one of the survivors of the survey team. At any rate, a human being. They drift up from the portal and take advantage of the lowered gravity at the core to sling their prize straight up into the maw of the Nihilanth, while sinking back themselves into the portal. A moment later, the awesome sight repeats itself. They are feeding the thing a steady diet of people.

You want only to get away…to remove yourself from any possibility of its noticing you. You discover an opening near at hand, a place perhaps where you can hide. But even as you enter, you can hear the electric crackling of the Vortigaunts. This place cannot possibly be safe—and yet…there is nowhere else to go.

Within, the Vortigaunts are busy. Too busy, in fact, to take notice of your presence. The air is charged with their power, and yet the trails of energy are aimed not at you but at the powerful machines that crowd your path. The creatures work in unison, tapping power from immense reservoirs and feeding it into huge cathodes, segregated into a few separate tasks in the first few rooms you explore. You move among them, avoiding the lighting blasts, but otherwise unhindered. But eventually you find a human prize, another scientist in an HEV suit, imprisoned in some sort of device which is drawing out his soul. You take his weapon and he begs you to kill him—and in fact, there is no other way to progress.

Once provoked, the Overmind lets out an alarm and raises its arms. Lightning flickers from its fingertips, sweeping the ground around you. A tide of snarks comes seething from every surface—spawning from teleports, appearing between crannies in the stone. They threaten to engulf you. You can fight them with the hivehand, and by leaping across gaps in the rock and using the effects of lowered gravity to dodge them, causing them to fall into the void. The Overmind fires jolts of psionic lightning at you, which has the advantage of crisping many snarks.

When you have mostly beaten the snarks and inflicted sufficient damage on the Overmind, it will begin to retreat, rising through the iris into the darkness above. As part of its retreat, it blows out the floor, and chunks of rock begin to rise in the Overmind’s wake. [DESTRUCTION OF ENVIRONMENT; RELATIVE MOTION/PARALLAX EFFECTS; MOVING TRAINS] You must keep your footing on the fragments, for they will carry you to the dark transition above. You are carried through a transition into a .bsp stacked directly above the first.

Zone 2: Controllers, Conveyors and Homing Missiles

Floating up into the second level, you find the Overmind awaiting you. (The region below is now completely dark, except for the orange beam extending upward.) It is accompanied by Controllers, who immediately come after you. [SQUAD/FLOCKING AI] The orange beam still streams up from the level below, and the violet beam extends from its crown straight up through another iris in the ceiling of this area. The surrounding rocks are less frequent here—it is much easier to plunge into the sky. Navigation in this area is accomplished via some sort of organic conveyor belt equivalent…a surrounding webwork of living goo-strands whose cilia scull you along the “walls” and across the space while the Overmind attempts to eradicate you. [CONVEYOR BELTS]

The pulsing heartbeat is even louder here, and it is now mixed (very occasionally) with a chilling alien whisper which sounds all too much like “Gordon Freeman” being uttered by an orifice unaccustomed to human speech. Possibly a telepathic threat—at any rate, evidence of recognition. The Overmind knows you. You’ve managed to become something important to it. [AUDIO EFFECTS]

The Overmind now starts drawing on its secondary attack–a “homing salvo” attack. It periodically (and frequently) fires off a cloud of silver spheres (directly related to the Controllers’ spheres) which scatter about in random directions then converge on your last location, exploding with tremendous force. You must stay on the move constantly to avoid being caught by the spheres. [AMAZING MONSTER BEHAVIOR]

You can do only limited damage to the Overmind from your awkward position. Every time you try to get the advantage of height, it rises toward the ceiling, giving the impression that its crown is fairly vulnerable. Whenever you kill the existing Controllers, the Overmind will send jolts of lightning out to portals located in the level, and summon in reinforcements; it will do this until, injuring the Overmind directly, you cause it to flee. When you have injured it sufficiently, and taken care of the Controllers (hopefully by luring them into the path of the Overmind’s homing spheres), the Overmind will retreat once more through the open ceiling. The area darkens. You follow through a transition into the third and final of the stacked levels.

Zone 3: The Portal

In the third level, you see that the violet beam connected to the Overmind’s crown is connected to a large portal mounted in a floating web directly overhead. The portal is open at the bottom (where you cannot reach) and guarded by some kind of mesh or protective cage on the upper portion, so you cannot jump in. Showers of lightning, energy beams, sizzle down from the portal, giving juice to the Overmind. [BEAM EFFECTS] Up here it is almost alone. The two of you hang in a darkened sky. There are enough chunks of circling and bobbing rock to allow you to make your way directly overhead and into the webwork, where you at last escape the lightning attacks and find good footing. But the gravity is lowest here, and you must be careful not to leap incautiously, or you will find yourself falling straight toward the Overmind and its sparking crown of lethal energy.

At the third level, the Overmind could introduce yet a third attack in combination with its lightning and salvo attacks. This is still unspecified. [MORE MONSTER BEHAVIOR]

Now that you are directly above the Overmind, you are finally at an advantage. It cannot fire lightning up at you because the portal is in the way. It is fairly easy to dodge the homing missiles up here. The pulse is at a high pitch, but the wailing telepathic echo of your name is almost pitiful. [AUDIO]

You can fire directly down into the core of the Overmind’s brain. You find the body of a fellow scientist trapped in the webwork, with tripmines and grenades, and by lobbing several of these into the Overmind’s sensitive region, you eventually wear the beast down to nothing—it implodes violently, splattering the rocks and portal-web with alien gore. [DECAL EFFECTS] Lightning and sparks are spawned to fill the area at the instant of death, and when they subside we see the orange portal beam from below growing stronger and stronger. In the absence of the Overmind, the orange beam has arced straight into the heart of the portal, and the portal is starting to go critical. [BEAM EFFECTS]

The cage surrounding the portal shatters [DESTRUCTION OF WORLD OBJECTS], opening the way for you to jump in. A high-pitched electronic shriek signals that the portal is overloaded and about to undergo a cosmic meltdown. The Overmind’s pulse has been replaced by a scream of pure energy rising to a killing pitch. An explosive power starts climbing the orange beam, shooting up the shaft from the levels below. You see a blazing pulse of death surging toward you from the hollow pit. Before it reaches the portal, you must leap in. If you remain behind, the explosion kills you. [EXPLOSION EFFECTS]

Then we switch to a third person camera, showing Gordon framed within a circular portal: a tiny speck or silhouette tumbling against a background of immense explosions. Everything goes white. When it fades, we are back on Earth…. [SCRIPTED SEQUENCE/NARRATIVE]

NOTES:

Apart from its attacks (lighting and homing salvo), the Overmind’s behavior is fairly simple. It needs to rotate to follow your location, and it needs to rise and fall within a restricted cylindrical space.

It would be great if the Overmind were not immediately visible, but partially shrouded in darkness, revealed by the flashes of its lightning attack. At the very least, when you commence battling it in the lowest level, it might show you only its lowest portions, and you won’t get sight of the entire creature until you climb above it in the uppermost level—where the play of portal lightning reveals the entire anatomy of the thing.

Health should be resupplied to the player in the form of floating localized pools of healing light…energy effects that are common and random in Xen, and which you will have learned to use by now. In the upper areas, they will be located in mid-air, so that in order to heal yourself you will have to make some precarious jumps through the middle of a healing light. Weapons and ammunition should be refueled with the bodies of your peers, which can be located in crevices.

***

The next file is called “Nihilanth” and dates from 7/21/98, making it a later and slightly more coherent development of ideas in the first file.

This one seems more like an attempt to sum up the ending thematically, and also it was an attempt at whipping up some marketing. Not sure who the audience was for this piece. Was it intended only for internal consumption? Were we trying to explain the story to others? I see in this (at this remove) the first hint that we were starting to look beyond HL1 at what the next threat might be. It was nothing as coherent as the Combine, and in fact for a while we threw all kinds of aliens at the problem before settling on a unified force.

***

FILE 2: “NIHILANTH”

[File first created and last edited on 7/21/1998]

The Nihilanth floated enchained, enmeshed in agonies. The light of colors without name bound it implacably. “You are nothing,” said the voice that echoed in its mind. “And yet you hear me, you feel everything, and in your pain you cast off the very stuff that holds the universe together.”

Horrible as the Nihilanth may have seemed, there was another thing more awful still which tormented it.

The Vortigaunts were not enslaved, except in the broadest sense. They did their duty out of devotion, and whatever befell the Nihilanth they accepted gratefully. It had been so always, in their collective memory; but the Nihilanth could still dimly recall a time when it had not been so, a distant age when it had not yet gathered so many entities around itself and made them necessary to its existence, forming a complex colonial organism which was sentient and malevolent in all of its parts.

There are numerous stories of humanity on the edge of reaching the stars—a small-minded and predatory race, more dangerous to others than even to itself, on the verge of extending their reach throughout infinity. Usually the technology that they are about to discover is that which makes space flight possible, faster than light travel. In Half-Life, the technology is teleportation.

Initially.

Teleportation has been mastered by a chain of superintelligent (compared to us) aliens. Mainly, they use it to exploit and enslave the races they encounter; their exploitation may be open or it may be extremely covert, involving political manipulation of the worlds they control. It all depends on what they want out of the species they intend to dominate.

The civilizations which are potentially the most dangerous—and also the most useful—to them are those which have independently arrived at the creation of a teleport technology which could surpass their own…for as in all things, even advanced alien superscience is bound to become obsolete, and the drive for a more powerful technology is unending.

Earth is at exactly this point. We made a few strong experimental forays into the science of teleportation, began to discover the practical underpinnings of the art, and then succeeded against our wildest dreams—stumbling into a weird dimension whose properties defied our understanding of natural law. Nor were we alone in this realm, which we named Xen—for that which is forever alien and inexplicable.

Xen proved to be a meeting place, a point where universes collided and hung in endless freefall, the elements of countless worlds intermingled. No sooner had we begun to explore Xen—with particular attention to its wealth of natural resources with unknown properties—than we found ourselves the object of unwanted inspection. Members of the survey team were collected in a cold and systematic manner, much as we gathered living specimens of alien wildlife. Realizing our precarious situation, we shut the portal completely, stranding the last members of the survey team and forcing them to survive alone in Xen.

But shutting our gate was not enough, for now the predators of Xen had traced our signal—found our location. And come looking for us.

The only hope seemed to be to find their portal and close that down from Xen itself; but we had lost contact with the survey team, and there was no one willing to cross over until Gordon Freeman reached the lambda portal. Eventually he reached the portal and killed the Nihilanth, which held the portal in existence by a concentrated effort of thought. But there was a deeper mystery awaiting him on his return to earth.