Corey Redekop's Blog, page 41

May 3, 2011

Monkey droppings - A Book of Tongues, by Gemma Files

Confession time: I'm a geek.No, no, please, let me finish. I'm a geek, and as such, there are certain literary qualifications I feel I have to admit to. I worship at the altar of all things Vonnegutian (if that's not an accepted term, consider it copyrighted to me and me alone, and you owe me a nickel if you use it in conversation). I play video games; perhaps not with the same "three day weekend of video goodness" mentality of my youth, but I recently completed Arkham Asylum, and am slowly working on the original Dead Space (I haven't jumped this much at a game since Resident Evil). In my early thirties I dressed as Bruce Campbell for Halloween, complete with chainsaw hand and sawed-off boomstick. I read zombie novels (hell, I'm writing one), I'm now heavily into the fantastical imaginations of Jeff Vandermeer and China Mieville, I'm deeply drawn to steampunk, I've even contributed to a fantastical bestiary (still coming, click here for proof of my bookish geekiness). I can quote Monty Python sketches verbatim.So yeah, I have geek credentials, a membership in the geek-of-the-month club. My not attending sci-fi, fantasy, and other genre conventions has far more to do with geographic placement than it does desire.But if there is something that I geek out over more than anything else, it's Clive Barker.Once, the Rainbow Lady had told Asher Rook, in dreams, a human ball-player was enticed by owls to pit his skills against the lords of death, and made a descent into what was then called Xibalba. He swam the river of blood, yet did not become drunk with it. He reached the crossroads, the Place of All Winds, where he took not the red road, nor the white, but the black. He entered the bone canoe, piloted by spiders and bats. He sank downwards, through cold water, to the whole world's bottom.Xibalba, as it was called then. Mictlan, as it became. Mictlan-Xibalba, as it is now, and will be, forever more.When he arrived, however, he was met only with mockery and betrayal. The Sunken Ball-Court's kings set him impossible tasks, then cheated the rules to make sure he would fail, and sent him to be executed, decreeing that his severed head should be set in a tree by the wayside, as a warning to other travellers.Promptly, the tree flowered all over, producing a hundred succulent calabash melons that attracted the attention of Blood Maiden, the Blood Gatherer's beautiful daughter. She reached up to pick one, only to discover she held the ball-player's skull instead. The skull spat in her hand, and told her: Though my face is gone, it will soon return, in the face of my son. And she found herself pregnant.

When I first started reading horror (probably too young, but hey, psychological scars don't show), it was Stephen King I flocked to, devouring everything of his I could, shaping my sensibilities for decades to come. From him, being a gateway author, I experimented with others; I dabbled in Koontz (too silly, no lasting side-effects), Simmons (whoo, a rush and a half), McCammon (ups and downs, usually a good ride), Rice (strong start, lately almost unreadable), Lansdale (now that's more like it), Wilson (Repairman Jack, what a guy), and Lumley (ridiculous, but those covers haunted my nightmares as a teen).But even beyond all those, the writings of Barker were a gutpunch to my psyche. Something about his style, gothic and gory and gorgeous, sank its talons into my medulla and began an eminently enjoyable parasitic relationship. Some labeled him as a 'splatterpunk' author, but Barker has never been a gore-for-gore's-sake sort, although he splashes the mausoleum red with the best of them. Reading The Hellbound Heart, with its miasma of kitchen sink marital drama and religious sadomasochism, was to suddenly comprehend the vast depth of perversions that exist outside my tiny middle-class life. The Damnation Game and The Books of Blood gave me epic horrors I never knew could be put to paper. Cabal gave me monsters as heroes, and to date is likely the only classic of modern horror to be set in Edmonton, Alberta. His efforts Weaveworld and Imajica and The Great and Secret Show proved to me that there existed the possibility of truly adult fantasies that created monsters and otherworldly terrains yet were not the usual hack-and-slash D&D epics that taint the fantasy shelves of my favourite bookstores (yeah, despite my geek certification, I've never fully embraced the genre subset of trolls and elves and middle-earth Tolkien wannabees). Barker filled his tales with mytho-religious symbolism, depraved desires, and the glories of all assortments of sexuality on a level I had never before experienced. And I fell head over hooks for him.But Barker's output is now sparse and erratic, with many promised jewels still awaiting completion (where are you, Scarlet Gospels? If I don't get my Harry D'Amour/Pinhead crossover soon . . . ). So I've been forced to look elsewhere for similar entertainments, and while I have not regretted the search, I can emphatically state that I have never found an author who raised in me the same level of excitement.Until, of course, the true subject of today's meandering post, Gemma Files, a Canadian author with some short story collections and poetry chapbooks to her credit, but nothing that has ever appeared on my radar. But her publisher ChiZine has, several times. I've said it before in these posts, and I'll say it again, there is no publisher out there that comes close to touching the heights of genre fiction that ChiZine is putting out. Tim Lebbon, Robert J. Wiersema, Lavie Tidhar, Craig Davidson, Douglas Smith, David Nickle, Tony Burgess - if you haven't yet discovered ChiZine, I envy you the journey I am now ordering you to undertake.

When I first started reading horror (probably too young, but hey, psychological scars don't show), it was Stephen King I flocked to, devouring everything of his I could, shaping my sensibilities for decades to come. From him, being a gateway author, I experimented with others; I dabbled in Koontz (too silly, no lasting side-effects), Simmons (whoo, a rush and a half), McCammon (ups and downs, usually a good ride), Rice (strong start, lately almost unreadable), Lansdale (now that's more like it), Wilson (Repairman Jack, what a guy), and Lumley (ridiculous, but those covers haunted my nightmares as a teen).But even beyond all those, the writings of Barker were a gutpunch to my psyche. Something about his style, gothic and gory and gorgeous, sank its talons into my medulla and began an eminently enjoyable parasitic relationship. Some labeled him as a 'splatterpunk' author, but Barker has never been a gore-for-gore's-sake sort, although he splashes the mausoleum red with the best of them. Reading The Hellbound Heart, with its miasma of kitchen sink marital drama and religious sadomasochism, was to suddenly comprehend the vast depth of perversions that exist outside my tiny middle-class life. The Damnation Game and The Books of Blood gave me epic horrors I never knew could be put to paper. Cabal gave me monsters as heroes, and to date is likely the only classic of modern horror to be set in Edmonton, Alberta. His efforts Weaveworld and Imajica and The Great and Secret Show proved to me that there existed the possibility of truly adult fantasies that created monsters and otherworldly terrains yet were not the usual hack-and-slash D&D epics that taint the fantasy shelves of my favourite bookstores (yeah, despite my geek certification, I've never fully embraced the genre subset of trolls and elves and middle-earth Tolkien wannabees). Barker filled his tales with mytho-religious symbolism, depraved desires, and the glories of all assortments of sexuality on a level I had never before experienced. And I fell head over hooks for him.But Barker's output is now sparse and erratic, with many promised jewels still awaiting completion (where are you, Scarlet Gospels? If I don't get my Harry D'Amour/Pinhead crossover soon . . . ). So I've been forced to look elsewhere for similar entertainments, and while I have not regretted the search, I can emphatically state that I have never found an author who raised in me the same level of excitement.Until, of course, the true subject of today's meandering post, Gemma Files, a Canadian author with some short story collections and poetry chapbooks to her credit, but nothing that has ever appeared on my radar. But her publisher ChiZine has, several times. I've said it before in these posts, and I'll say it again, there is no publisher out there that comes close to touching the heights of genre fiction that ChiZine is putting out. Tim Lebbon, Robert J. Wiersema, Lavie Tidhar, Craig Davidson, Douglas Smith, David Nickle, Tony Burgess - if you haven't yet discovered ChiZine, I envy you the journey I am now ordering you to undertake.

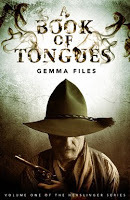

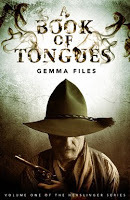

So when I saw Gemma Files' A Book of Tongues sitting on the shelf of my favourite bookstore (with another amazing cover - seriously, ChiZine covers are works of bloody art), I knew that I'd be getting a good bang for my buck. But I never saw this coming; it's too soon to call Gemma Files the next incarnation of Clive Barker, but if it happens the way I hope, I said it here first. Files has the same fanatical attention to research and detail, the same intermingling of eternal horrors with unexpected settings, the same fearlessness of the body and all its yearnings. If this manuscript had been given to me and attributed to Barker, I would have believed it.Setting her yarn in one of the only genres I do not recall Barker ever trying, the western, Files puts together an apocalyptic, baroque melange of cowboys, magicians, long-dead Mayan and Aztec gods, detectives, and biblical fury. Outwardly a story of rebel soldiers from the Civil War making their way across the American landscape as thieves and pursued by the Pinkerton Detective Agency, Files subverts all expectations and arrives at a stunningly original result; think Hellraiser crossing paths with The Wild Bunch. My experience with western novels starts with Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove quartet (a masterpiece), and ends with Chuck Norris's ode to all that is awful in life The Justice Riders. I think it safe to assume that McMurtry might admire Files' subversive take on the genre, but Charles McHighKicks will choke on his own rage/beard as the heroes and villains of the western epic narrative tradition he has long modelled his career after are exposed to the unflinching sexual storytelling prowess of Files."On this whole wide earth, there's nothin' worse than a bad man who knows the Bible." So says "Reverend" Asher Rook, who knows whereof he speaks. Rook is a hexslinger, an outlaw born with supernatural tendencies, a bible-quoting mystic who uses phrases of the Bible to access his unique abilities.

So when I saw Gemma Files' A Book of Tongues sitting on the shelf of my favourite bookstore (with another amazing cover - seriously, ChiZine covers are works of bloody art), I knew that I'd be getting a good bang for my buck. But I never saw this coming; it's too soon to call Gemma Files the next incarnation of Clive Barker, but if it happens the way I hope, I said it here first. Files has the same fanatical attention to research and detail, the same intermingling of eternal horrors with unexpected settings, the same fearlessness of the body and all its yearnings. If this manuscript had been given to me and attributed to Barker, I would have believed it.Setting her yarn in one of the only genres I do not recall Barker ever trying, the western, Files puts together an apocalyptic, baroque melange of cowboys, magicians, long-dead Mayan and Aztec gods, detectives, and biblical fury. Outwardly a story of rebel soldiers from the Civil War making their way across the American landscape as thieves and pursued by the Pinkerton Detective Agency, Files subverts all expectations and arrives at a stunningly original result; think Hellraiser crossing paths with The Wild Bunch. My experience with western novels starts with Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove quartet (a masterpiece), and ends with Chuck Norris's ode to all that is awful in life The Justice Riders. I think it safe to assume that McMurtry might admire Files' subversive take on the genre, but Charles McHighKicks will choke on his own rage/beard as the heroes and villains of the western epic narrative tradition he has long modelled his career after are exposed to the unflinching sexual storytelling prowess of Files."On this whole wide earth, there's nothin' worse than a bad man who knows the Bible." So says "Reverend" Asher Rook, who knows whereof he speaks. Rook is a hexslinger, an outlaw born with supernatural tendencies, a bible-quoting mystic who uses phrases of the Bible to access his unique abilities.Together with his lieutenant/lover Chess Pargeter, a terrifyingly remorseless killer, Rook leads his men across the wilds of the west, robbing trains and banks, killing all in their path. Also in their midst is Ed Morrow, a detective gone undercover to discover the extent of Rook's power and perhaps unlock the secrets of magic.In this world, magicians are not quite plentiful, but they are historically documented, and the Pinkerton Detective Agency hopes to gather enough information to put a halt to all magical activities, and perhaps use magicians against each other to clean up the Earth. "Break her to the bridle and use her, like any other animal. Turn a wolf into a dog." What works in their favour is the fact that "Mages don't meddle;" magicians in this world cannot work together for long until one inevitably turns on the other. This simmering hostility has kept hexslingers from combining their powers and becoming as gods. If Rook has his way, however, there may be a way around this.Files is an intensely visceral writer, delivering fantasy/horror with the glee of a razor-wielding psychopath; just the thing for my Barker kick. But enough about Barker, Files is her own author, and while the similarities are there (Rook reminds me completely of Barker's Nix, another magician with delusions of godhood), Barker has only laid the groundwork for the next generation, a generation Files could prove herself a leader. She is equally fearless in gore, grotesqueries, and sex (boy, is she fearless in sex, in all its glories and fluids), but her style is brilliant and complex, a gorgeous mixture of goth and grit that completely transforms the material into something magical. Not many people, I suspect, could mash together lovecraftian-style horror with Old West patois with such panache.Does it go too far? Arguable. The story does careen wildly at points, and doubtless some will be turned off by Files' frank and earthy depictions of homosexual congress, others by vivid descriptions a la "carving out loops of guts, as the man tried hopelessly to stuff them back in."But sometimes, that's what I want in horror. I appreciate all forms of horror for their differing strengths (I'm currently enthralled with the quiet atmosphere and dread of John Ajvide Lindqvist's Harbor), but sometimes I want to be pushed past the boundaries of my own taste, I want to be abused. Clive Barker was my go-to guy for this, and still is; I predict a re-read of The Damnation Game is in my near future. And now, I've got Gemma Files to warm/horrify the cockles of my whatever it is that cockles reside in. She is a true talent, and I look forward to whatever fresh horrors she may unleash upon my imagination.As it bore down on [Rook] - the uppermost Pinkerton already back on his feet, grasping for the Gatling's crank - he opened his mouth and preached, from Corinthians:THOUGH I SPEAK WITH THE TONGUES OF MEN AND OF ANGELS, AND HAVE NOT CHARITY, I AM BECOME AS SOUNDING BRASS, OR A TINKLING CYMBAL.It was one of the sweetest verses known to man, quoting at every wedding he'd officiated. But when his lips shaped the words, something else came out through his mouth along with them - a lashing ghost-tongue spear of silver-gilt which rammed full-speed through the boiler without jumping the train off its tracks, just pinning it there like a massive iron bug, releasing its entire compliment of steam in a hissing cloud.And that was the problem, in the end. It was a bit too dense for Rook to completely calculate what he was doing. So though he'd meant for whatever effect he produced to stop short, or just slap the Pink silly, it split the man's skull and neck alike, spraying everything around it with gouting red.

The second book in the series, A Rope of Thorns, is available at the end of May.I've already pre-ordered a copy.VERDIC

The second book in the series, A Rope of Thorns, is available at the end of May.I've already pre-ordered a copy.VERDIC

T: DID YOU NOT JUST READ THE REVIEW? MONKEY LOVES!

T: DID YOU NOT JUST READ THE REVIEW? MONKEY LOVES!Monkey droppings - A Book of Tongues, by Gemma Files

But all three? At once?

Fair warning: this review will be one of the geekiest the monkey has ever done.

A Book of Tongues (ChiZine, 2010)

by Gemma Files

Confession tine: I'm a geek.Once, the Rainbow Lady had told Asher Rook, in dreams, a human ball-player was enticed by owls to pit his skills against the lords of death, and made a descent into what was then called Xibalba. He swam the river of blood, yet did not become drunk with it. He reached the crossroads, the Place of All Winds, where he took not the red road, nor the white, but the black. He entered the bone canoe, piloted by spiders and bats. He sank downwards, through cold water, to the whole world's bottom.

Xibalba, as it was called then. Mictlan, as it became. Mictlan-Xibalba, as it is now, and will be, forever more.

When he arrived, however, he was met only with mockery and betrayal. The Sunken Ball-Court's kings set him impossible tasks, then cheated the rules to make sure he would fail, and sent him to be executed, decreeing that his severed head should be set in a tree by the wayside, as a warning to other travellers.

Promptly, the tree flowered all over, producing a hundred succulent calabash melons that attracted the attention of Blood Maiden, the Blood Gatherer's beautiful daughter. She reached up to pick one, only to discover she held the ball-player's skull instead. The skull spat in her hand, and told her: Though my face is gone, it will soon return, in the face of my son. And she found herself pregnant.

No, no, please, let me finish. I'm a geek, and as such, there are certain literary qualifications I feel I have to admit to. I worship at the altar of all things Vonnegutian (if that's not an accepted term, consider it copyrighted to me and me alone, and you owe me a nickel if you use it in conversation). I play video games; perhaps not with the same "three day weekend of video goodness" mentality of my youth, but I recently completed Arkham Asylum, and am slowly working on the original Dead Space (I haven't jumped this much at a game since Resident Evil). In my early thirties I dressed as Bruce Campbell for Halloween, complete with chainsaw hand and sawed-off boomstick. I read zombie novels (hell, I'm writing one), I'm now heavily into the fantastical imaginations of Jeff Vandermeer and China Mieville, I'm deeply drawn to steampunk, I've even contributed to a fantastical bestiary (still coming, click here for proof of my bookish geekiness). I can quote Monty Python sketches verbatim.

So yeah, I have geek credentials, a membership in the geek-of-the-month club. My not attending sci-fi, fantasy, and other genre conventions has far more to do with geographic placement than it does desire.

But if there is something that I geek out over more than anything else, it's Clive Barker.

When I first started reading horror (probably too young, but hey, psychological scars don't show), it was Stephen King I flocked to, devouring everything of his I could, shaping my sensibilities for decades to come. From him, being a gateway author, I experimented with others; I dabbled in Koontz (too silly, no lasting side-effects), Simmons (whoo, a rush and a half), McCammon (ups and downs, usually a good ride), Rice (strong start, lately almost unreadable), Lansdale (now that's more like it), Wilson (Repairman Jack, what a guy), and Lumley (ridiculous, but those covers haunted my nightmares as a teen).

When I first started reading horror (probably too young, but hey, psychological scars don't show), it was Stephen King I flocked to, devouring everything of his I could, shaping my sensibilities for decades to come. From him, being a gateway author, I experimented with others; I dabbled in Koontz (too silly, no lasting side-effects), Simmons (whoo, a rush and a half), McCammon (ups and downs, usually a good ride), Rice (strong start, lately almost unreadable), Lansdale (now that's more like it), Wilson (Repairman Jack, what a guy), and Lumley (ridiculous, but those covers haunted my nightmares as a teen).But even beyond all those, the writings of Barker were a gutpunch to my psyche. Something about his style, gothic and gory and gorgeous, sank its talons into my medulla and began an eminently enjoyable parasitic relationship. Some labeled him as a 'splatterpunk' author, but Barker has never been a gore-for-gore's-sake sort, although he splashes the mausoleum red with the best of them. Reading The Hellbound Heart, with its miasma of kitchen sink marital drama and religious sadomasochism, was to suddenly comprehend the vast depth of perversions that exist outside my tiny middle-class life. The Damnation Game and The Books of Blood gave me epic horrors I never knew could be put to paper. Cabal gave me monsters as heroes, and to date is likely the only classic of modern horror to be set in Edmonton, Alberta. His efforts Weaveworld and Imajica and The Great and Secret Show proved to me that there existed the possibility of truly adult fantasies that created monsters and otherworldly terrains yet were not the usual hack-and-slash D&D epics that taint the fantasy shelves of my favourite bookstores (yeah, despite my geek certification, I've never fully embraced the genre subset of trolls and elves and middle-earth Tolkien wannabees). Barker filled his tales with mytho-religious symbolism, depraved desires, and the glories of all assortments of sexuality on a level I had never before experienced. And I fell head over hooks for him.

But Barker's output is now sparse and erratic, with many promised jewels still awaiting completion (where are you, Scarlet Gospels? If I don't get my Harry D'Amour/Pinhead crossover soon . . . ). So I've been forced to look elsewhere for similar entertainments, and while I have not regretted the search, I can emphatically state that I have never found an author who raised in me the same level of excitement.

Until, of course, the true subject of today's meandering post, Gemma Files, a Canadian author with some short story collections and poetry chapbooks to her credit, but nothing that has ever appeared on my radar. But her publisher ChiZine has, several times. I've said it before in these posts, and I'll say it again, there is no publisher out there that comes close to touching the heights of genre fiction that ChiZine is putting out. Tim Lebbon, Robert J. Wiersema, Lavie Tidhar, Craig Davidson, Douglas Smith, David Nickle, Tony Burgess - if you haven't yet discovered ChiZine, I envy you the journey I am now ordering you to undertake.

So when I saw Gemma Files' A Book of Tongues sitting on the shelf of my favourite bookstore (with another amazing cover - seriously, ChiZine covers are works of bloody art), I knew that I'd be getting a good bang for my buck. But I never saw this coming; it's too soon to call Gemma Files the next incarnation of Clive Barker, but if it happens the way I hope, I said it here first. Files has the same fanatical attention to research and detail, the same intermingling of eternal horrors with unexpected settings, the same fearlessness of the body and all its yearnings. If this manuscript had been given to me and attributed to Barker, I would have believed it.

So when I saw Gemma Files' A Book of Tongues sitting on the shelf of my favourite bookstore (with another amazing cover - seriously, ChiZine covers are works of bloody art), I knew that I'd be getting a good bang for my buck. But I never saw this coming; it's too soon to call Gemma Files the next incarnation of Clive Barker, but if it happens the way I hope, I said it here first. Files has the same fanatical attention to research and detail, the same intermingling of eternal horrors with unexpected settings, the same fearlessness of the body and all its yearnings. If this manuscript had been given to me and attributed to Barker, I would have believed it.Setting her yarn in one of the only genres I do not recall Barker ever trying, the western, Files puts together an apocalyptic, baroque melange of cowboys, magicians, long-dead Mayan and Aztec gods, detectives, and biblical fury. Outwardly a story of rebel soldiers from the Civil War making their way across the American landscape as thieves and pursued by the Pinkerton Detective Agency, Files subverts all expectations and arrives at a stunningly original result; think Hellraiser crossing paths with The Wild Bunch. My experience with western novels starts with Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove quartet (a masterpiece), and ends with Chuck Norris's ode to all that is awful in life The Justice Riders. I think it safe to assume that McMurtry might admire Files' subversive take on the genre, but Charles McHighKicks will choke on his own rage/beard as the heroes and villains of the western epic narrative tradition he has long modelled his career after are exposed to the unflinching sexual storytelling prowess of Files.

"On this whole wide earth, there's nothin' worse than a bad man who knows the Bible." So says "Reverend" Asher Rook, who knows whereof he speaks. Rook is a hexslinger, an outlaw born with supernatural tendencies, a bible-quoting mystic who uses phrases of the Bible to access his unique abilities.

Together with his lieutenant/lover Chess Pargeter, a terrifyingly remorseless killer, Rook leads his men across the wilds of the west, robbing trains and banks, killing all in their path. Also in their midst is Ed Morrow, a detective gone undercover to discover the extent of Rook's power and perhaps unlock the secrets of magic.As it bore down on [Rook] - the uppermost Pinkerton already back on his feet, grasping for the Gatling's crank - he opened his mouth and preached, from Corinthians:

THOUGH I SPEAK WITH THE TONGUES OF MEN AND OF ANGELS, AND HAVE NOT CHARITY, I AM BECOME AS SOUNDING BRASS, OR A TINKLING CYMBAL.

It was one of the sweetest verses known to man, quoting at every wedding he'd officiated. But when his lips shaped the words, something else came out through his mouth along with them - a lashing ghost-tongue spear of silver-gilt which rammed full-speed through the boiler without jumping the train off its tracks, just pinning it there like a massive iron bug, releasing its entire compliment of steam in a hissing cloud.

And that was the problem, in the end. It was a bit too dense for Rook to completely calculate what he was doing. So though he'd meant for whatever effect he produced to stop short, or just slap the Pink silly, it split the man's skull and neck alike, spraying everything around it with gouting red.

In this world, magicians are not quite plentiful, but they are historically documented, and the Pinkerton Detective Agency hopes to gather enough information to put a halt to all magical activities, and perhaps use magicians against each other to clean up the Earth. "Break her to the bridle and use her, like any other animal. Turn a wolf into a dog." What works in their favour is the fact that "Mages don't meddle;" magicians in this world cannot work together for long until one inevitably turns on the other. This simmering hostility has kept hexslingers from combining their powers and becoming as gods. If Rook has his way, however, there may be a way around this.

Files is an intensely visceral writer, delivering fantasy/horror with the glee of a razor-wielding psychopath; just the thing for my Barker kick. But enough about Barker, Files is her own author, and while the similarities are there (Rook reminds me completely of Barker's Nix, another magician with delusions of godhood), Barker has only laid the groundwork for the next generation, a generation Files could prove herself a leader. She is equally fearless in gore, grotesqueries, and sex (boy, is she fearless in sex, in all its glories and fluids), but her style is brilliant and complex, a gorgeous mixture of goth and grit that completely transforms the material into something magical. Not many people, I suspect, could mash together lovecraftian-style horror with Old West patois with such panache.

Does it go too far? Arguable. The story does careen wildly at points, and doubtless some will be turned off by Files' frank and earthy depictions of homosexual congress, others by vivid descriptions a la "carving out loops of guts, as the man tried hopelessly to stuff them back in."

But sometimes, that's what I want in horror. I appreciate all forms of horror for their differing strengths (I'm currently enthralled with the quiet atmosphere and dread of John Ajvide Lindqvist's Harbor), but sometimes I want to be pushed past the boundaries of my own taste, I want to be abused. Clive Barker was my go-to guy for this, and still is; I predict a re-read of The Damnation Game is in my near future. And now, I've got Gemma Files to warm/horrify the cockles of my whatever it is that cockles reside in. She is a true talent, and I look forward to whatever fresh horrors she may unleash upon my imagination.

The second book in the series, A Rope of Thorns, is available at the end of May.

The second book in the series, A Rope of Thorns, is available at the end of May.I've already pre-ordered a copy.

VERDIC

T: DID YOU NOT JUST READ THE REVIEW?

T: DID YOU NOT JUST READ THE REVIEW? MONKEY LOVES!

April 22, 2011

I have been remiss! Oh, bad, bad monkey, thy name is ... remiss? Is that a name?

Why bring this up, you ask? Well, aside from being a darn sight better than many similar websites, with insightful commentary and in-depth book reviews, it has a marvellous lineup of reviewers.The Winnipeg Review publishes on-line every quarter, with weekly updates, from its eponymous home. Like the inhabitants of this midcontinental city, TWR is always opinionated, occasionally cranky, and ethnically confused. We exist to review literary books, mostly Canadian fiction, and to showcase interviews, excerpts, poems, and columns by writers with something to say.

Do you really not see where I'm going with this?

Yes, I have gouged away heaping hunks of my free time to through a few reviews their way, which I have been sadly neglect in mentioning here, a neglect I will now remedy.

First, my very recent review of Timothy Taylor's remarkable The Blue Light Project:

And secondly, from two months ago, my two-hander review of Alexander MacLeod's Light Lifting and Sarah Selecky's This Cake is for the Party:The Blue Light Project does not do things the easy way; there are no clear lines of plot, the agendas of secondary characters flit in and about, not everything is tied up in a neat bow. Some reviewers have tried to compensate by refusing to follow the inner logic, instead imposing upon Blue Light a structure Taylor never intended: one reviewer in a major Canadian publication takes this so far as to devote the majority of the review to Pegg's interview with the hostage taker, all but ignoring Eve and Rabbit, removing much of the mystery Taylor delicately builds, and emphasizing all out of proportion what turns out to be a fairly small segment of the actual novel.

Blue Light, despite some remarkably tense moments, is not a thriller, and Taylor never posits it as such. The hostage situation is integral, but it functions as a pivot point for the others to balance on, not as a central theme. What is far more important is Taylor's conjecture that only through trauma can we see clearly and possibly hope to achieve something meaningful in our lives. Blue Light's characters are all seekers; of what, they are not sure, until something jars them from complacency. We see this in the various mobs that surround the building, yearning to be a part of the conclusion, wanting to be a part of anything that might affect them and thus add significance to their existence.

And there you have it. Drop in to The Winnipeg Review for some terrific reviews of a few of my recent favourites, including a sterling treatise by Lee Kvern on Valerie Compton's affecting Tide Road and Michelle Berry on Miriam Toews Irma Voth (on my TBR pile).At this point, any review of Sarah Selecky's or Alexander MacLeod's recent work could be argued as superfluous. Their fame, for the moment, is secure. Two collections of short stories, each acclaimed to a degree that would make most authors collapse under the weight of their envy. Each a Giller finalist. Each now shortlisted for Commonwealth Best First Book, winner still to be determined. Each taking a comfortable roost inside national and regional bestseller lists. Selecky earns comparisons to Alice Munro. MacLeod escapes the sizable shadow of CanLit heavyweight and father Alistair to carve his own small niche in the canon. These are truly auspicious beginnings for any literary career.

Taken side by side, weighing each collection against the other as we would combatants in a field of battle, Selecky's This Cake is for the Party and MacLeod's Light Lifting showcase sizable talents, displaying unique voices and mastery of craft. They each contain stories of memories captured in time, stories that tell of personal moments and hint at larger ramifications beyond the last sentence. Yet of the two, This Cake holds together better as a whole, but Light Lifting hints at a slightly broader range. It is doubtful anyone would mistake a Selecky story for a MacLeod, but MacLeod could, in the future, pull off a reasonable Selecky.

April 17, 2011

Monkey droppings - sci-fi epics, haunted wilderness, and unnerving neighbours

The monkey ranks them from least favourite to most.

The monkey likes ranking. And ranks.

Refer to the monkey as Commodore Monkey from now on.

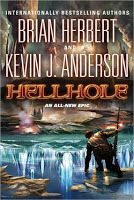

Hellhole (Tor, 2011)

by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson

Pretty much all you need to know about Hellhole can be summed up in its cliffhanging final sentence: "With this war, we will make his planet a true hellhole."

Translation: this ain't a subtle work. I cannot say from personal knowledge how Brian Herbert's continuation of father Frank's Dune series ranks as compared to the originals, but from what I've read in Hellhole I'd say, "Not good."

That's too damning, however. Judged on its own performance, Hellhole is a fun space opera; hardly artful or incisive, but would likely make a good mini-series. Yet comparisons with Frank Herbert's seminal masterpiece are inevitable, particularly when both books concern planetary politics, alien races, strange religious beliefs, and mad dictators intent on galaxy domination. Dune was almost biblical in its construction, an expansive, encompassing, engrossing piece of world-building that meticulously crafted theological underpinnings to guide its fantastic universe. Hellhole is a blunt instrument, a sledgehammer retelling of the settlement of America, except this time, the settlers make peace with the indigenous peoples rather than slaughtering them wholesale. Dune was fresh; Hellhole is recycled.

But it is fun, in an obvious way. I hadn't read a sci-fi space epic since Neal Stephenson's grandiose Anathem, and while this may seem like heresy (it does to me), I found more sheer entertainment in Hellhole's pages than in Anathem's ponderousness.

Taking place ten years after a failed rebellion, disgraced leader General Tiber Adolphus has been exiled to the Deep Zone planet of planet Hallholme (read: Hellhole) rather than receiving a death sentence.

NOTE: As an aside, can we all agree how lucky for the publisher that the original name of the planet wasn't Peaspoot, Sheetcrack, or Matherfluck? Dodged a real bullet there.On Hellhole, Adolphus bides his time, building up settlements and paying out planetary tributes to the power-hungry Diadem Michella Duchenet. But he's also sowing seeds among the fifty-three other planets in the Deep Zone, altering transport routes and forming alliances. When explorers discover the original inhabitants of Hellhole (long thought dead from an asteroid strike), Aldolphus realizes that there might be a new way to rid his planet of the Diadem's chokehold.

This is fairly standard sci-fi world-building, filled with broad expositional characters, speechifying, and ridiculous names. I suspect half the fun of writing such operas is the creation of unusual character appellations; a quick referral to the handy glossary reveals Ishop Heer, Encix, Kerris Urvancik, Rendo Theris, and Tel Clovis, among many others. Every character is clear and obvious; bad guys are hissable, good guys are noble. The alien race of Xayans are laughably spiritual and ludicrously naïve.

But again, it's just fun. I won't carry Hellhole in my soul as I do Dune, Brian Herbert and his co-writer Kevin J. Anderson are hardly maestros, but I never resented the time I took to read it. Call it a b-movie of a book, one of those films on TBS that you get sucked in to watching despite their obvious flaws. I loves me some Stanley Kubrick and Duncan Jones and Ridley Scott, but sometimes a Roland Emmerich or Michael Bay can be just the thing to wile away an afternoon. Or David Lynch's adaptation of Dune, come to think of it.

VERDICT: MONKEY ENJOYS DESPITE HIMSELF (BAD MONKEY!)

The Silent Land (Doubleday, 2010)

by Graham Joyce

I had never heard of Graham Joyce, but I vaguely recall once perusing his novel Indigo, with an accompanying front-cover rave from Stephen King (a recommendation I can never again trust, thanks to his grossly over-enthusiastic blurbs on the covers of Bentley Little novels—man oh man, The Walking was just terrible). The Silent Land, however, comes with a rapturous blurb by geek god Jonathan Lethem, a writer whose shoes I am not worthy to lick. So in I dive, not knowing what to expect, keeping myself purposely vague on the plot details.

A short while later (the plot just zooms by), I emerge, unscarred but shaken and genuinely spooked. The Silent Land is hardly a genre-buster, but this atmospheric and ghostly little chiller is just the thing for a quiet night alone, with the wind howling outside for added oppression.

Zoe and Jake awaken early one morning during a ski vacation to get on the mountain before the tourists carve up the slopes. Trapped in an avalanche—a mightily effective piece of claustrophobic writing here, as Zoe struggles to right herself under hundreds of pounds of snow—the pair find their way back to the village to discover everyone gone. They wait for people to return, expecting that the town was evacuated as a precaution, but as the days stretch by it becomes apparent that something has gone drastically wrong.

Joyce is not exactly traversing new material here; Zoe and Jake's predicament is the stuff of the Twilight Zone, two people trapped somehow outside of reality. There are echoes of King's The Mist and The Langoliers in its construction, as well as the video game Silent Hill, although monumentally less gory. The Silent Land never crosses the road into outright horror, but Joyce can create a hauntingly evocative sense of despair and loneliness like few others.

Joyce is a craftsman, and while the structure may not be unique, the author layers on more than enough style to make the story his own. The Silent Land was recently nominated for the Shirley Jackson award, and it's easy to understand why; Joyce shares with Jackson her marked economy of words and marvellous dexterity with mood. The Silent Land does not re-invent the wheel; the ultimate ending can be seen a mile away, being a staple of many similar entertainments, and this obviousness contributes to the slightly less-than-enthralling finale. It is a letdown to have the cards revealed, the magicians showing the trick, and having figured it out so easily.

Nevertheless, The Silent Land is a superior spook machine. Joyce has a canny grasp of characters and dialogue which raises the storyline from the merely weird to one that is greatly, enjoyably creepy. Read this one with the lights low, and a cat curled on your lap for company. As Zoe and Jake's predicament unravels, you may find you'll need the companionship as you check over your shoulder at every noise.

VERDICT: MONKEY REALLY LIKES

Sarah Court (ChiZine, 2010)

by Craig Davidson

If Hellhole is entertainment for a lazy afternoon, and The Silent Land is a late evening's ghost story, then Sarah Court is the book for two a.m., when your brain is tired and decides to play tricks on you. And if Jonathan Lethem's praise of The Silent Land intrigued me, Sarah Court's triumvirate of Peter Straub, Chuck Palahniuk, and Clive Barker grabbed me by the throat and demanded some attention, dammit!You really are such magnificently grim bastards. Trashing utopias is how you party.

Sarah Court, a series of five interweaving stories all set around a neighbourhood near Niagara Falls, is one strange little beastie. Craig Davidson has previously written a book of short stories and a novel, both set in and around the sport of boxing. Yet while boxing does make an appearance here, these tales are far different than I expected; gritty, moving, and often unpredictably eerie and horrific.

Translation: I loved Sarah Court, but I'd never want to live there.

Davidson's stories are outwardly simple, only revealing layers of complexity when the other stories begin to overlap. There's a father whose job it is to fish corpses from the river, and a son vainly trying to regain his glory as a stuntman. A doctor disgraced for uncertain reasons. A former boxer who now works as a high-end enforcer of the infamous American Express Black Card. A boy who thinks he's Dracula. An unwilling powerlifter. A strange woman with a revolving door for foster children.

And through every tale, there are hints of unnamable corruption, usually in the guise of animals or elements of the corporeal body, reminding me of nothing so much as filmmaker David Lynch and his genius at creating unclassifiable dread. Red spider mites teem in a deer's eyes, "so many as to give the impression it's weeping blood." A can of paint has "the hue of diseased organ meat." Squirrels abound in Sarah Court, somehow playful yet harbingers of some interior evil a la the sinister owls in Lynch's Twin Peaks. "The owls are not what they seem." And in several tales there is the presence of a perplexing transparent box holding "a squirming mass the size of a medicine ball."

While Davidson wreaks some sinister havoc on his characters, there is a grounding in reality that keeps Sarah Court from becoming weird for weird's sake. There is an outlying supernatural element, but Davidson's horror is far more the horror of character, of people causing unconscious destruction through their own ill-conceived desires. No resident of Sarah Court gets off unscathed; there are emotional cripplings, physical disfigurements, and mental implosions. There is also good, a desire to rise above the fray, making the climax of each story almost overpowering in each person's sad realizations of their weaknesses.

Sarah Court is a startling, often brilliant collection, further proof that publisher ChiZine is the go-to publisher for unsurpassable genre literature (even more proof: just began Gemma Files' A Book of Tongues, and wow wow wow). Mr. Davidson's neighbourhood has never seen a beautiful day in its life, and I do not want to be a neighbour. However, I will walk its streets from time to time, whistling in the dark to keep the demons at bay. And watching for squirrels.

VERDICT: MONKEY FREAKIN' LOVES

April 3, 2011

Monkey droppings - Room, by Emma Donoghue

Monkeys should be free, not caged.

However, the monkey does enjoy free meals, so he's torn.

Room (HarperCollins, 2010)

by Emma Donaghue

By now, there really is little point in reviewing Room, Emma Donoghue's internationally best-selling novel shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and winner of the Hughes & Hughes Irish Novel of the Year and the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize (among others). Its high-concept subject matter assured attention, its pedigree assured quality, and its ultimate content assured that Room will be a staple of book clubs for years to come.While Bath is running, Ma gets Labyrinth and Fort down from on top of Wardrobe. We've been making Labyrinth since I was two, she's all toilet roll insides taped together in tunnels that twist lots of ways. Bouncy Ball loves to get lost in Labyrinth and hide, I have to call out to him and shake her and turn her sideways and upside down before he rolls out, whew . . . Fort's made of can and vitamin bottles, we build him bigger every time we have an empty. Fort can see all ways, he squirts out boiling oil at the enemies, they don't know about his secret knife-slits, ha ha. I'd like to bring him into Bath to be an island but Ma says the water would make his tape unsticky.

With all that, my knee-jerk reaction was to hate it. Nothing breeds reflexive contempt like massive success, which Room has in abundance. I am fairly surprised that there hasn't yet been a Life of Pi-like backlash, although I am sure that it's coming.

So it comes with no little sense of relief that I report Room to be, in all aspects, fully deserving of its acclaim. From the first page, Donoghue won me over with a superbly-examined portrait of a young boy caught up in horrendous circumstances, and a mother determined to keep her son safe from a reality almost impossible to imagine. Believe me, I'm as surprised as anyone to care for Room so deeply, as I fully predict an Oprah endorsement, if she's still doing that sort of thing.NOTE: And bite it, naysayers, Life of Pi is a damn fine novel, probably one of my top ten for the first decade of the century.

Based thematically on real-life events too gruesome and upsetting to mention here (so I'll just point out a wikipedia article here), Room concerns the never-named Ma and her five-year-old son Jack. As Jack narrates the tale (in a manner obviously too advanced for any five-year-old, but never mind, we have to take some literary liberties, and besides, Donoghue's depiction of his mind-set is wonderfully original and astute), we discover that they have lived in an eleven-foot square room for the entirety of his life. For Jack, life is the room, what exists within the room, and the television which shows life beyond, but which Ma assures him is not real in the slightest. Anything they require comes from Old Nick, a (to Jack) foreboding father figure who brings what he and Ma need, if it suits him to do so. It becomes quickly apparent that Ma has been kidnapped, Jack was born in captivity after Old Nick had raped Ma, and she has done her utmost to protect Jack from the reality that there is an entire world outside the walls that he can never see. In this, Room is thematically similar to Roberto Benigni's Life is Beautiful, about a father's desperate attempts to shield the horrors of the holocaust from his son by telling him that the death camp they reside in is really a game.

For Jack, alone with Ma and shielded from Old Nick, life is nothing but a festive routine:

It is startling how readable Room is considering its intensely unsettling subject matter. I had steeled myself for a gut-wrenching tale of horror (how could it be anything but?), but Donoghue subverts expectations through placing her tale in Jack's hands. Through his eyes, what is horrific to consider becomes a day-to-day normality, and while Donoghue does not shy away from Jack and Ma's circumstances, her insistence in grounding the tale in Jack's limited perspective keeps Room from becoming a claustrophobic tale of horror, and her immaculate skill keeps the story from eroding into a Flowers in the Attic clone (wow, I just made myself shudder at the prospect).We do Bowling with Bouncy Ball and Wordy Ball, and knock down vitamin bottles that we put different heads on when I was four, like Dragon and Alien and Princess and Crocodile, I win the most. I practice my adding and subtracting and sequences and multiplying and dividing and writing down the biggest numbers there are. Ma sews me two new puppets out of little socks from when I was a baby, they've got smiles of stitches and all different button eyes.

It is not giving away anything (besides, every other review has done so) to reveal that Jack and Ma do indeed escape, and that half the book takes place outside of Room, as Jack adjusts himself to a world he never considered possible. As the two become unwilling celebrities, Donoghue allows herself some pointed barbs at media hysteria over such cases, especially in a pointed exchange between Ma and an over-zealous interviewer. As the interviewer keeps pushing for the triumph-over-adversity angle, and how brave it was for Ma to keep Jack despite his brutal conception story, she plays at being dismayed that Ma had breast-fed Jack for the entirety of their captivity. As Ma says, "In this whole story, that's the shocking detail?"

As Jack comes to grips with the concept that his life has been an entire lie (There are other people? Animals actually exist?), the author arguably lays it on a little thick, and the tale threatens to become repetitive. Jack's befuddlement and sometimes outright terror at the new reality is clear and vividly drawn, but the constant predictability at his responses hinders the narrative. Perhaps it is because the first half of the novel was a completely alien terrain to the reader, but the second half suffers from a slight case of obviousness. Yet Donoghue keeps throwing left hooks where you least expect it, keeping the story building to its inevitable conclusion.

At its core, Room is about the mother-child dynamic, about love and trust, and the lengths we go to protect those we care about most. Emma Donoghue has indeed crafted a memorable novel fully deserving of its praise. Its themes are identifiable to most readers, its concept is gripping from the get-go, but what pushes it out over the top is that that Donoghue is just so fine a writer. She is a magician of character and nuance, and makes Room a special treat.

VERDICT: MONKEY DAMN NEAR LOVES

VERDICT: MONKEY DAMN NEAR LOVESMarch 9, 2011

Monkey droppings: The Good, the innocuous, and the ugly

The monkey's done a lot of 'high lit' reading lately.

The monkey's done a lot of 'high lit' reading lately.Time to go genre, clear the palate, get some junk food.

Healthy, well-regarded junk food.

Subway, not Arby's.

Three reviews, hot and fresh and ready for the table. One good, one innocuous (bad seemed too harsh), and one ugly (think Hollywood-ugly, not ugly-ugly).

THE GOOD

Lanceheim (HarperCollins, 2010)

by Tim Davys

In 2009, Tim Davys (a pseudonym) released the English translation version of Amberville, the first in what I have now discovered to be the Mollisan Town quartet. It was a hardboiled noir dealing with issues of faith, death, fate, and existence. It was also populated exclusively by stuffed animals, automatically appealing to a strange side of me that enjoys unique literary examples of anthropomorphization (Hello, Winkie! Hello, Hal Jam!)."Without doubt, faith is worth nothing."

I loved Amberville, and tore into its sequel Lanceheim with gusto, expecting another tale of Eddie Bear and his investigatory exploits. Imagine my surprise (and later delight) at finding Lanceheim to be an entirely different beast, set in another section of Mollisan Town (segmented into the quarters of Amberville, Lanceheim, Tourquai, and Yok), this time not a detective noir but a parable, a play on the Christ mythology that takes on many of the same themes of Philip Pullman's The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ yet plays them far more intriguingly (and I really enjoyed Scoundrel Christ).

Lanceheim follows two separate narrative paths: on one, the reader follows Reuben Walrus, a famed composer seeking a miracle following a diagnosis of quickly oncoming deafness; on the other, a fellow named Wolf Diaz recounts his life as friend and later servant to Maximilian, a strange stuffed animal with unusual powers and a gift for speaking in obtuse parables. As in Amberville, the residents of the city live in fear of death, or in this case, "the Chauffeurs," dark figures who arrive without warning and remove stuffed animals who have reached the end of their lives. New residents are manufactured by Magnus, their (for lack of a better word) god, and Maximilian, with his charisma and lack of guile, is starting to threaten the religious hierarchy that uses fear of Magnus to keep the populace of Mollisan Town in check.

Davys comes across heavy-handed at times, more so than Amberville, and oftentimes Lanceheim falls prey to speechifying to get its point across. Yet again, Davys uses the conceit of a world of stuffed animals to bring forth serious questions of faith, dogma, and politics that would weigh down more realistic portrayals. Lanceheim is a less satisfactory novel than Amberville, too episodic, but it still retains a startling power, particularly in its remarkable twists near the end. I look forward to the next novel Tourquai with particular delight."I intend to create a Retinue," said Chaffinch, "which is neither afraid to believe nor to listen. The stuffed animals in this city are suffering. You know that, Wolf, you know it well - the terrified pursuit of success and material happiness that never has an end. Weighed down by the dogmas of the church. The thought of the Chauffeurs, and that they might come any day whatsoever. Stuffed animals are to be pitied. And if we can give them solace, we must do so. If ten stuffed animals can repeat what I say, what Maximillian has taught us, we are ten times more effective."

VERDICT: MONKEY LIKES A LOT

THE INNOCUOUS

The Good Fairies of New York (Soft Skull Press, 2006)

by Martin Millar

Ah, whimsy. So easy to get tired of."Right, you two," said Dinnie, stomping back into the room. "get out of here immediately and don't come back."

"What's the matter with you?" demanded Heather, shaking her golden hair. "Humans are supposed to be pleased, delighted and honored when they meet a fairy. They jump about going, 'A fairy, a fairy!' and laugh with pleasure. They don't demand they get out of their room immediately and don't come back."

"Well, welcome to New York," snarled Dinnie. "Now beat it."

That's not fair, but sustaining whimsy over 200+ pages is hard. Far better if you taint your whimsy (yikes, now there's a sentence I've never typed before) with a healthy dapple of cynicism a la Vonnegut, or a dose of giddy mean-spiritedness a la Douglas Adams. You need balance, take the salt with the sweet.

Martin Millar almost pulls it off with The Good Fairies of New York. The cult urban fantasist (his Lonely Werewolf Girl sound likes a good time) sprinkles whimsy all throughout his tale of misplaced fairies making their way in the unScotlandlike boroughs of New York, but makes sure to add rude jokes, violence, obscenities, and various naughty bits to keep his ethereal heroines grounded in filthy reality. And it's fun, but too slight to resonate after completion.

The Good Fairies are Heather and Morag, thrown out of Scotland for inadvertently desecrating a fairy clan's sacred banner. Heather takes room with the disconcertingly awful Dinnie, "an overweight enemy of humanity [and] the worst violinist in New York," while Morag moves in across the street with Kerry, a free spirit suffering from Crohn's disease and attempting to complete a flower alphabet for a Community Arts award. There are also rock 'n' roll ghosts, Italian fairies, Chinese fairies, an awful version of A Midsummer Night's Dream, mythic flowers, horrible fiddle-playing, homeless people, and more subplots and diversions than you can shake a wand at.

It's all handled with a fair amount of aplomb; Millar is an amiable storyteller, and at its best Good Fairies reads like Neil Gaiman-lite, or a more sedate Terry Pratchett. But the story structure and its constant narrative momentum leave every character a cipher; I wanted to grow to like Dinnie, I understood that Kerry was adorable, but never did I actually appreciate them beyond their postings as serviceable plot movers. I can see that Millar is a talented fantasist, and I look forward to revisiting his imagination, but The Good Fairies is only diverting, too flimsy a tale to last.

VERDICT: MONKEY LIKES, BUT ONLY SO FAR AS THAT GOES

THE UGLY

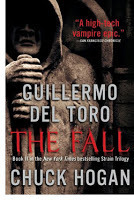

The Fall (HarperCollins, 2010)

by Guillermo del Toro & Chuck Hogan

Well, 'ugly' might be overstating it. The Fall is fairly entertaining. But these vampires, man, they is ugly.

The direct sequel to last year's The Strain, The Fall is part two in author Chuck Hogan's and director Guillermo del Toro's Strain Trilogy, about a vampire epidemic taking over the world. In this world, vampires ain't the usual vaguely European dandies in capes, they are virus-laden monsters with a six-foot stinger that extends from their throats to grab and infect any person unlucky enough to be nearby. Continuing from the previous instalment, we join our hardy gang of vampire killers (including an epidemiologist, his young son, an elderly vampire hunter, and a New York exterminator who takes to monster slaying with ease) as they hunt down the Master, the one rogue vampire responsible for an outbreak which shows every possibility of destroying mankind permanently. Or at least moving us substantially down the food chain.

The authors tell their story well, jumping from attack to attack, but as with The Strain, the real problem is a lack of actual scares. The vampires lack personality, and the story moves forward so rapidly that there is no time to learn to empathize with the heroes. What we get is a fast-paced Hollywood monster movie from two men who should know better. Del Toro knows his monsters (Cronos, Mimic, Hellboy) but as he proved with Pan's Labyrinth, he can provide depth to join with his imagination to result in something truly spellbinding and wonderful (side note: del Toro's finally giving up on his adaptation of The Hobbit is likely a great loss to filmgoers, and his recent troubles in getting a Tom Cruise-starring adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness is a personal grievance). Hogan, in Prince of Thieves, proved himself an able craftsman who can weld interesting characters onto classic action scenarios. Working together, the result should be a near-classic, and its managing to be merely entertaining is a severe disappointment. I'm not turned off enough to not look for the finale in 2011, but The Fall is a wasted opportunity, a lark by two talents slumming it.

VERDICT: MONKEY THINKS IT'LL DO UNTIL THE NEXT DIVERSION, HEY, SOMETHING SHINY!

March 1, 2011

hidden monkey - Because I Have Loved and Hidden It, by Elise Moser

Today, a new monkey joins the shelves. The hidden monkey.

Today, a new monkey joins the shelves. The hidden monkey.Or hidden book, if you will. The book that, for one reason or another, never got the attention it desired (leastwise, from the shelf monkey).

Which, of course, goes for most books. But since blogging is largely subjective, I'll allow myself the power to decide what precisely constitutes a hidden monkey.

These will be short, pithy reviews, because sometimes, my longwindedness overwhelms me.

Today's debut instalment:

Because I Have Loved and Hidden It (Cormorant Books, 2009)

by Elise Moser

the hidden monkey plot: Julia is a fortyish woman whose mother has just passed away. At the funeral, her Uncle Paul reveals a startling revelation about her past, one that her mother has kept hidden away until now. In a parallel plotline, Julia's married lover Nicholas has gone missing, and as she strikes up an unlikely friendship with his wife, Julia finds herself becoming unmoored from the life she thought she knew.

why is this monkey hidden? It is a fact of literary life that sometimes (hell, most times), despite glowing reviews, quality books deserving of love fall between the cracks. Until I had cause to meet the author Elise Moser in person, I had never heard of Because I Have Loved at all.

what does the shelf monkey think? Because I Have Loved and Hidden It is gloriously lush and sensual, a deeply passionate examination of one woman's spiritual rebirth, if that isn't too hackneyed and overused a phrase. Moser displays a raw carnality that is refreshing, never playing coy but giving full force to the emotional erruptions Julia faces. The plot description may seem the stuff of soap operas, but Moser is a gifted storyteller, bringing Julia to life with delicate notes that enbue her with emotional realism. There are a few jarring moments - references to The X-Files and other popular entertainments are at odds with the subtlety of Moser's prose - but overall this is a sterling novel, one to be savoured.

hidden monkey verdict: this monkey deserves to come out of the shadows.

February 20, 2011

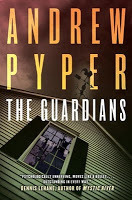

Monkey droppings - The Guardians, by Andrew Pyper: "No such thing as an empty house."

The monkey fears nothing!

The monkey fears nothing!'Nothing' as in an absence. A void. An empty space. Blackness.

Man, does the monkey fear nothing.

The Guardians (2011, Doubleday Canada)

by Andrew Pyper

It's really difficult to write about a horror novel without somehow mentioning Stephen King. You can't escape his influence, even if you want to. If a writer were to pen a horror novel without any foreknowledge of King's oeuvre, I'd still lay odds that there would be a comparison somewhere.

This isn't necessarily a bad outcome. It's no small thing to be compared to someone who single-handedly changed the way people looked at horror fiction. And when you write as King does (obsessively, compulsively) and publish as many books as he has, you're bound to cover pretty much every theme in the book.

King has his standbys, of course. He loves small towns. He luxuriates in the theme of past horrors rising back to the surface. He often puts children at risk in some way.

So when you write a novel about men returning to their hometown to confront an evil which scarred them as children, a Stephen King comparison is a fait accompli. All you can do is hope it's favourable.

Andrew Pyper, who has been Canada's best pure thriller writer for quite some time now (Lost Girls, his debut, is a marvel of sustained atmosphere), is finally getting some recognition beyond the critical. His last novel The Killing Circle was a treat and a half, a moody and introspective serial killer piece that also functioned as a sly critique of authors and pop culture journalism. His newest, The Guardians, has been appearing on best-seller lists since its release.

And no wonder; with its canny mixture of nostalgia, personality, and frights, The Guardians is a superior haunted house story, with echoes of the best of Peter Straub and Shirley Jackson.

And yes, it wields the traits of Stephen King, particularly in the precisely hewn township that Pyper sets his tale in. Rather than King's Derry or Castle Rock, Pyper crafts into existence the small, nicely forbiddingly named Ontario town of Grimshaw, a splendidly articulated burg that Pyper could easily revisit with other stories should he wish a la King.

It was thought, when they built the four lanes running west between Toronto and the border of Detroit a couple years before I was born, that the highway's proximity to Grimshaw would lend new purpose to what was before then not much other than a service town for the country's farmers. But there was no more reason to take the Grimshaw exit than there had previously been to limp in its direction on the old, rutted two-lane. Like many of the communities its size on the broad arrowhead of farmland stuck between the Great Lakes, it remained a forgotten place. Never industrial enough to be outright abandoned in the way of the ghost towns of Ohio, Pennsylvania and Upstate New York, but not alert enough to attempt re-invention. Grimshaw was content to merely hang one, to take a subdued pride in its century homes on tree-lined streets, the stained facades of its Victorian storefronts, its daughters or sons who met with success upon moving away. Now, entering it as a stranger, one might see a gothic charm in the wilful oldness of the place, its loyalty to the vine-covered, the paint-peeled. But for those who grew up here, it was only as it had always been.

As it is with all small towns, there is one house that somehow seems a little off, a little psychically skewed; "not sane," as Jackson put her Hill House. In Grimshaw, it is the Thurman house, decrepit yet always there, eternal, only in place to become the stuff of nightmares for children; "the Thurman house never allowed itself to be observed without a corresponding price."

As it is with all small towns, there is one house that somehow seems a little off, a little psychically skewed; "not sane," as Jackson put her Hill House. In Grimshaw, it is the Thurman house, decrepit yet always there, eternal, only in place to become the stuff of nightmares for children; "the Thurman house never allowed itself to be observed without a corresponding price."The tale is narrated by Trevor, a middle-aged man suffering the beginning stages of Parkinson's Disease. Twenty-odd years ago, he and three friends, Ben, Randy, and Carl - the guardians of the title, and players on the local hockey team The Grimshaw Guardians - found their own shared nightmare within the walls of the house, a nightmare partly of the own devising when they decided to find out what had happened to a missing music teacher. Now, Ben, the only one to remain in Grimshaw, is dead by his own hand, and when the three Guardians return for the funeral, they find that they have never outrun their past.

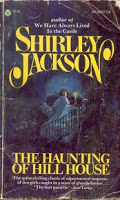

Many haunted house novels (the good ones, anyway, the ones that stay with you long after you've closed the book, put it back on the shelf, and checked under your bed before you dared go to sleep) are not only about the house itself, but rather use the supernatural manifestations and ghostly goings-on as metaphor for larger issues. King's The Shining, with the never-surpassed ghastliness of the Overlook Hotel (thank you Kubrick for the ideal cinematic manifestation of its evil), is a novel about the dissolution of family through addiction. Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House addresses repression, Dan Simmons' The Summer of Night, the end of childhood. There are other themes present, of course, but I'm generalizing for the sake of brevity. And I'm lazy, there I said it.

Many haunted house novels (the good ones, anyway, the ones that stay with you long after you've closed the book, put it back on the shelf, and checked under your bed before you dared go to sleep) are not only about the house itself, but rather use the supernatural manifestations and ghostly goings-on as metaphor for larger issues. King's The Shining, with the never-surpassed ghastliness of the Overlook Hotel (thank you Kubrick for the ideal cinematic manifestation of its evil), is a novel about the dissolution of family through addiction. Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House addresses repression, Dan Simmons' The Summer of Night, the end of childhood. There are other themes present, of course, but I'm generalizing for the sake of brevity. And I'm lazy, there I said it. In its dual structure of the present-day narration of Trevor and the past brought to life through his recorded "memory diary," The Guardians addresses the theme of masculinity, of what it is to 'be a man.' Much of the boyhood trauma which occurs (and no spoilers here, I assure you) requires the boys to take definitive steps toward a maturity they are arguably unprepared to take. In the present, we see said masculinity present in the mid-life crises of the men: Trevor, unable to commit and facing a slow decline into immobility; Randy, failed actor; and Carl, the saddest of them, vanished in a haze of dangerous activities.

In its dual structure of the present-day narration of Trevor and the past brought to life through his recorded "memory diary," The Guardians addresses the theme of masculinity, of what it is to 'be a man.' Much of the boyhood trauma which occurs (and no spoilers here, I assure you) requires the boys to take definitive steps toward a maturity they are arguably unprepared to take. In the present, we see said masculinity present in the mid-life crises of the men: Trevor, unable to commit and facing a slow decline into immobility; Randy, failed actor; and Carl, the saddest of them, vanished in a haze of dangerous activities.All this may make it seem as if The Guardians is a ponderous slog though subtext, but Pyper keeps the story zipping along with verve. He does make the odd stumble - the main female character seems a bit too good to be true - but he displays, once again, a canny knack for characterization that feels warm and identifiable, an ability to put fully recognizable and sympathetic characters into great peril.

Pyper also understands the mechanics of the haunted house itself, the classic theory that such places are less haunted than they are psychic mirrors feeding off their inhabitants.

Within what was probably less than three minutes, I slid from the heights of fear to boredom. This is what a haunted house was: a place where nothing happens, so you have to make something up. It's the same impulse that makes us tell lies to a stranger sitting next to us on a plane, or pushes the planchette over a Ouija board to make it spell you dead cousin's name.

And when the horror comes, it is subtle and spooky and shivery in all the right places. Ghosts do indeed roam the halls of the Thurman house, ghosts that ache with past transgressions. Pyper never lets the story get gory, playing instead with mood to create the Thurman house as a dark and twisted place. "Touching the boy was like touching the inside of a scream," is a delicious sentence I'll remember for a long time.

And when the horror comes, it is subtle and spooky and shivery in all the right places. Ghosts do indeed roam the halls of the Thurman house, ghosts that ache with past transgressions. Pyper never lets the story get gory, playing instead with mood to create the Thurman house as a dark and twisted place. "Touching the boy was like touching the inside of a scream," is a delicious sentence I'll remember for a long time. Not that there's anything wrong with gore, lest you think me a prude: Richard Matheson's Hell House is a treasure trove of unsubtle, full-throttle gruesomeness.

I started this review with Stephen King, let me end with him. In his excellent treatise Danse Macabre, King lays out the three levels of literary fear. First is terror, which shows nothing but taps into the darkest recesses of the mind. Second is horror, a little lesser on the scale, scary to think about and usually contains a more visceral element. Lastly, there's revulsion, or in King's terminology, "the gross-out." Andrew Pyper's novel The Guardians never stoops to the gross-out, dabbles in the horror, and works mainly with terror, which makes it a top-notch horror novel, and a damned fine story whatever the genre.

VERDICT: MONKEY REALLY LIKES

February 13, 2011

Monkey droppings - Michael Van Rooy

The monkey has no jokes today.

An Ordinary Decent Criminal

(Turnstone, 2005)

(Turnstone, 2005)by Michael Van Rooy

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Criminal (Turnstone), 2008)

by Michael Van Rooy

"You do the math. If you're a bad guy, you don't have a job, no bank account, no apartment. You live in hotels, move around a lot, eat in restaurants. But not expensive hotels because you might be noticed in those and you'll need ID . . . You need maybe sixty bucks a day for food and a little more than that for the hotel and maybe another thirty to fifty for incidentals . . . That's about one-eighty each day. Life gets stressful, though, so you start doing a little something to deal with the stress. If you drink or do grass to level you out, that's another twenty or forty per day. But you can't be level all the time, you might have to move fast so that means keeping cocaine or crank or meth handy, and that's another fifty to one hundred a day and that's if you don't have friends. That's a total of about three Cs per day. Every day. That means two grand one per week, or eight grand four per month, and that means one hundred and nine thousand, two hundred dollars per year. Period."

Michael Van Rooy was a Winnipeg author who passed away far too soon in January 2011. Michael was an author much beloved in the Winnipeg community; his first novel won the Eileen McTavish Sykes Award for Best First Book, he won the 2009 John Hirsch Award for most promising writer, he worked with emerging writers, he served on several Arts boards and was named one of Winnipeg's arts ambassadors for its 2010 Cultural Capital of Canada campaign.

Michael Van Rooy was a Winnipeg author who passed away far too soon in January 2011. Michael was an author much beloved in the Winnipeg community; his first novel won the Eileen McTavish Sykes Award for Best First Book, he won the 2009 John Hirsch Award for most promising writer, he worked with emerging writers, he served on several Arts boards and was named one of Winnipeg's arts ambassadors for its 2010 Cultural Capital of Canada campaign.I never got a chance to get to know Michael; we were Facebook 'friends' brought together through mutual interests, and only last December did I have the opportunity to meet Michael in person. He was signing copies of his books at a Coles bookstore in Winnipeg, and I was fortuitously visiting my family for the holidays. I stopped by to do the old one author to another appreciation bit, and we chatted for twenty minutes or so. I found Michael to be a warm and approachable sort, and I thought to myself that were I to ever return to Winnipeg for a long-term stay, Michael would be a person I would very much enjoy hanging out with.

Even in that brief space of time, I could tell that Michael was a man passionate about his profession. He gave me a few pointers on how to better pitch a few novelists I represent to Thin Air, the Winnipeg International Writers' Festival. We discussed our mutual work, my still-in-editing second novel and his ongoing series of crime novels, which had just been picked up for release in the States by Minotaur Books. I left with signed copies of his first two novels and a promise to keep in touch.

And the books sat on my shelves for a brief time while I attended to the many other things that takes up the daily routines of life. And then Michael suddenly passed away, at the age of forty-two, while on tour for his latest release A Criminal to Remember.

I didn't know how to feel about it all. I still don't. We were not close in any way, but I keenly felt the loss of an author whom it appeared was on the cusp of bigger things. And so I honoured his memory in the only way I could; I sat down with his first novel An Ordinary Decent Criminal and began to read.

And now, with two books read and only one left to purchase, his loss is even more personal. Michael Van Rooy was a real talent, his novels bursting with wit, bravado, and style. That we get only three Monty Haaviko novels to remember him by is, quite frankly, not nearly enough, and not fair.

Both An Ordinary Decent Criminal and Your Friendly Neighbourhood Criminal concern the ongoing exploits of Montgomery "Monty" Haaviko, an ex-con with a seriously cruel past that Van Rooy thankfully keeps all but hidden. As Decent Criminal opens, Monty has changed his name and moved his family to Winnipeg, Manitoba, hoping to give them all a fresh start.

Both An Ordinary Decent Criminal and Your Friendly Neighbourhood Criminal concern the ongoing exploits of Montgomery "Monty" Haaviko, an ex-con with a seriously cruel past that Van Rooy thankfully keeps all but hidden. As Decent Criminal opens, Monty has changed his name and moved his family to Winnipeg, Manitoba, hoping to give them all a fresh start.Doubtful. From the opening sentence, "I had a gun I didn't want to use," it is clear that Monty may yearn for the quiet life, but the quiet life doesn't want him. In its first four pages, Monty has killed three intruders to his new home, and Van Rooy has provided not only an attention-grabbing start but the groundwork for a defiantly appealing hero/anti-hero. Monty may view himself as a simple ODC ("ordinary decent criminal"), but as Van Rooy's story revs up, it becomes abundantly clear that Monty, no matter his current intentions, was never ordinary.

Throughout Decent Criminal's narrative, we see that the odds are stacked up against him at every turn. The three men he killed had connections to a local crime figure who has a personal stake in seeing Monty punished for defending himself and his family. Detective Sergeant Enzio Walsh has figured out Monty's past, and has made it his personal vendetta to destroy Monty by any means necessary. And Monty's new neighbourhood is hardly accepting of Monty and his family, particularly after Walsh begins a not so discreet campaign of slander against him. But Monty is not alone: his wife Claire is supportive, nurturing, but realistic about erasing Monty's past; his son Fred is still in diapers; and his dog Renfield is, well, a dog. Yet without them, Monty would be another lost soul"I used to be bad. Now I'm not."