Chris Pearce's Blog, page 30

August 24, 2015

Architecture in ancient Rome

Ancient Roman architecture borrowed heavily from Greek architecture, such as the huge columns used in temples, but it soon developed its own distinctive style of domes, arches and vaults. These features hadn’t been used before and can be attributed to the innovative use of concrete by the Romans. They also learnt from the Etruscans to the north with their knowledge of hydraulics and arch construction.

The Romans’ use of arches allowed them to build aqueducts across the empire. Examples include 11 aqueducts in Rome and the almost intact Aqueduct of Segovia on the Iberian Peninsula. Many bridges were constructed using the same principle, such as the Merida Bridge over two forks of the Guadiana River in Spain with its 60 arches. Similarly, the invention of the dome produced innovations in public building. Vaulted ceilings allowed taller, wider public buildings, including basilicas and bath houses. Huge temples were constructed, such as the Pantheon in Rome with its large concrete dome and its open spaces. Over 220 amphitheatres, including the Colosseum, were used for public meetings, displays, and gladiatorial contests. The Romans built many lighthouses too. Many of their buildings and structures still stand.

Private housing and associated structures were also made to last. Most obvious are private baths and latrines as well as water pipes, hypocausts for under floor heating, and double glazing. The Romans built multi-story apartment blocks or “insula.” The residences within these blocks were semi-detached and each one had its own terrace and entrance. Apartments had a similar floor plan, making these buildings cheap and easy to construct. Rooms were basic yet functional. Interior walls were often plastered and painted in colorful patterns such as alternating stripes of red and rainbow. Despite being regarded as unhealthy fire hazards, some of these building still stand, such as in the Roman city of Ostia.

In the early period of Roman civilization, the predominant building material was marble. This was used to construct buildings with thick columns supporting flat architraves, very much in the Greek style. When concrete became the main material, covered with tiles, larger and more imposing buildings were erected, with pillars supporting arches and domes. Concrete allowed colonnade screens of decorative columns to be erected in front of load bearing walls. It also allowed large open spaces within buildings rather than smaller rectangular cells.

Concrete wasn’t invented by the Romans. This honor probably goes to the Mesopotamians, who used it as a minor or supplementary material. But the Romans were the first to use it on a large scale. Their concrete included stones, sand, water and lime mortar, making it stronger than earlier concrete. These ingredients were put into wooden frames and allowed to harden and bond with bricks or stones to make a strong wall. The surface was smoothed and a layer of stucco or tiles of marble or other stone was added. Mosaic patterns made of colored stone became popular in the first and second centuries for both public and private buildings, complementing the murals that already decorated many floors and walls.

The greater use of concrete and the resulting grandeur of Roman public architecture greatly assisted the expansion of the empire. The buildings were not only constructed to perform their intended use but also to impress. They were very durable, many of them withstanding wars and the environment for 2000 years.

August 23, 2015

Romulus and Remus: The beginnings of Roman civilization

Romulus and Remus were part of the royal family of the city of Alba Longa, southeast of Rome, a family whose ancestors had fled from Troy in present day Turkey. Brothers Numitor and Amulius had assumed the throne after their father’s death. Numitor had a daughter Rhea Silvia, but he feared she might have children who would eventually overthrow him. He forced her to become a vestal virgin priestess which meant she had to swear to abstinence.

But Mars, the god of war, seduced her and she had twin boys Romulus and Remus. Modern day historians believe that Amulius may have been the father. The story has several variations, but it seems that a servant was ordered to kill the illegitimate twins. Unable to bring himself to commit such an act, he cast them adrift in the Tiber where they were looked after by river god Tiberius before they were nursed in a cave by a she-wolf. The twins were found by Amulius’ shepherd Faustulus who, with his wife, raised the boys.

When they reached adulthood, Romulus and Remus killed their great uncle Amulius, who had overthrown their grandfather Numitor. This meant Numitor was restored to the throne. After this, the twins decided to found their own town and chose the spot, Palatine Hill, where the wolf had nursed them. This is the center of the Seven Hills of Rome. Each brother supposedly stood on a hill, and when a flock of birds flew past Romulus, this signified that he should become king of the new city. He started building the walls but Remus complained they were too low and demonstrated this by jumping over them. In a fit of rage, Romulus killed him. In another version, Remus was killed after the twins argued about who had the support of the local gods and thus have the city named after him.

Romulus kept building the new city and named it Roma (Rome) after himself. The first citizens, who were fugitives and outlaws, settled on Capitoline Hill. A shortage of wives for these men prompted Romulus to abduct some women from the Sabine tribe to the north. The Sabine king Titus Tatius and his men were furious and went to war against Romulus and his settlers. But the Sabine women were happy with their new husbands and urged a ceasefire between the warring parties. They joined forces and Romulus and Titus Tatius were joint rulers of their combined groups for five years until Tatius was assassinated by outsiders.

As sole king, Romulus legislated against murder and adultery. There were three tribes under his rule: the Latins from the area around Rome itself, the Sabines, and the Etruscans further north. Together they became the Romans. Romulus divided each tribe into 10 curiae or subdivisions for administrative purposes. A tribune or elected official represented each tribe in civil, military, and religious matters. Romulus fought many wars and expanded the Roman territory for more than 20 years, gaining control over much of today’s central and northern Italy. When Numitor died, Romulus took over as ruler of Alba Longa too, appointing a governor to manage the city’s affairs.

Legend has it that Romulus disappeared supernaturally in a storm after leading the Romans for 37 years. A senator announced to the people that their leader had gone to live with the gods. A temple was built to him on Quirinal Hill. Numa Pompilius, Tatius’ son in law, became Rome’s second king. Modern day analysis suggests that little if any of the story is true. It may have been taken from a Greek tale a few centuries after the founding of Rome in order to explain the origin of the name and some of its early customs.

August 22, 2015

England’s Navigation Act of 1651

The Navigation Act of 1651 was passed by the English Parliament in an attempt to prevent non-English ships from transporting goods to England from places outside of Europe, while both English ships and those from the originating country could carry goods within Europe. It was one of several navigation Acts passed by parliament.

England has legislated in the areas of shipping and trade since as early as 1381. The navigation acts were brought about due to the deterioration in English trade following the end of the Eighty Years’ War between the Dutch and the Spanish in 1648. The Dutch emerged with an overwhelming competitive advantage in coastal trade throughout most of Europe. Also, the level of trade in English commodities fell due to a substantial increase in goods from Mediterranean countries, as well as the Levant, the Iberian Peninsula and the West Indies.

The English wanted to stop or reduce the market for these imports. A precedent had already been set in 1645 when the Greenland Company persuaded parliament to pass an Act stopping whale imports other than by this company. Similarly, in 1648 the Levant Company petitioned to prevent Turkish imports. By 1650, parliament was preparing a policy to restrict imports via the Netherlands. A bill was passed in 1651 stating that English trade was to be carried in English ships. The bill was largely a reaction to the failure of the Netherlands to agree to an English proposal to join forces and take over Spanish and Portuguese colonial possessions. England’s idea was for it to take over America and the Dutch could have Africa and Asia. But the Dutch had just finished a protracted war against Spain and had already gained several Portuguese colonies in Asia and weren’t interested. Instead, they suggested a free trade agreement. This would be to the Netherlands disadvantage as they had been the leading sea trader for many years, with their superior ships, lower tariffs and a near monopoly in the Baltic area. England rejected the idea and took the proposal as an affront.

The new Act prevented foreign ships carrying goods from outside the European area to England or English colonies, and also denied other countries from transporting goods from European countries to England except for a ship belonging to a country where the goods originated. Thus the Act specifically targeted the Dutch and the advantage it had in sea trade, something the Dutch economy had become quite dependent on. The failure of negotiations and the Act itself are often blamed for the First Anglo-Dutch War of 1652-54. English naval supremacy resulted in several battle wins in the North Sea, but the Dutch were able to close down English trade in the Mediterranean and the Baltic. Finally, the Treaty of Westminster ended the war in 1654, although English trade continued to suffer at the hands of the Dutch.

All Acts, including the Navigation Act of 1651, were declared void when Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 following a period of military and parliamentary rule that operated after the English Civil War. A new Act, the Navigation Act of 1660, was similar to the preceding Act. Another Act, the Navigation Act of 1663, stated that European goods heading for the colonies, including America, had to go via England, where they had to be unloaded, inspected and reloaded, but not before the duties were paid. Costs and delivery times increased. Neither Act lasted long. Following the Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665-67, the Dutch gained various trade concessions.

The end of the Navigation Acts came in 1849 due to growing support for free trade. The aim of the Acts had been to gain wealth through restricting trade. But in the end, they pushed costs up. By the mid 19th century, England wanted to reduce food prices for the starving masses in the industrial towns and saw that it could do this through cheap imports.

The effects of the Navigation Acts were mixed. In the short and medium term, there were a number of benefits, at least for England. The Acts limited Dutch trade, and may have contributed greatly to London becoming a commercial center for American goods. An increase in English trade led to a larger and more powerful Royal Navy, enabling the British Empire to flourish. Even so, the Dutch trading system was so efficient that they were able to maintain their trade supremacy. The Navigation Acts caused colonial resentment and were partly responsible for the American Revolution. They also led to higher prices and inefficiency, which eventually prompted Britain to repeal them.

A further navigation Act, the Molasses Act of 1733, resulted in heavy duties on French West Indies sugar headed to America, who then had to buy the more expensive British West Indies sugar.

August 21, 2015

Should Australia increase its GST rate?

I posted the following comment to a Business Spectator article (http://www.businessspectator.com.au/news/2015/8/21/tax/nsw-presses-case-15-gst) yesterday:

An increase in the GST [goods and services tax] rate is probably the way to go. When a country raises a large proportion of its taxes from income, as in Australia, it is more susceptible to the ups and downs in the economic cycle. This is because income (and therefore taxes on it) fluctuates more than consumption (and the taxes raised on it). Thus it would probably make sense to increase the proportion of tax on consumption, such as an increase in the GST to 15%. What’s in and what’s out can be discussed. At the same time, we would need to lower tax rates on income, especially at the lower levels, to compensate.

But the net change in tax wouldn’t amount to much. It might be a relatively small increase and we would still be running the large deficits we’ve had ever since the GFC pushed revenue through the floor, and it still hasn’t recovered. Practically every government (left, right and centre) in the world ran deficits at the time of the GFC to keep their economies out of recession or in many cases to ease the severity of an inevitable recession.

The Coalition is now pushing the federal government debt up by $5 billion a month because they have reduced taxes and increased expenditure. Expenditure by the Coalition will average 25.6% of GDP in 2014-15 to 2018-19 compared with Labor’s average of 24.9% in 2008-09 to 2012-13 and that period included the GFC and stimulus packages to keep us out of recession. But fundamentally, it remains a revenue problem rather than an expenditure one. The Coalition has pushed the federal government debt up from $265 billion to $380 billion in 23 months. At that rate, the debt will be around $900 billion by 2023-24.

The problem started in the early and mid 2000s with endless tax cuts and high expenditure with the government not putting much away for a rainy day. The previous Coalition government was wasteful according to a 2013 IMF report using data to 2011 that found the Australian government “profligate” in 2003, 2005, 2006 and 2007 (and 1942 and 1960). Also, public service numbers increased by 40,000 from 2000 to 2007 compared with 5000 between 2008 and 2013.

In order to fix the problems that the previous and current Coalition governments have given us, we will need to do much more than fiddle with GST. We would still need to look at the overly generous tax concessions on property investment and superannuation. Tax concessions amount to about $120 billion a year or 8% of GDP, far higher than comparable countries.

We would also need to look at some form of carbon pricing rather than the expensive and ineffective Direct Action which has pushed emissions back up after we saw a fall during the time of the carbon tax. Getting rid of carbon pricing will cost the budget $18 billion over four years according to the Parliamentary Budget Office or about $800 a person.

Land tax is another option that should be discussed.

We might also need to abolish the states and save $50 billion a year according to a 2007 estimate in a PhD study by Dr Mark Drummond. At the moment we have eight systems (six states and two territories) all basically doing the same thing, which the federal government (one system) could do, rather than all the current inefficiencies, overlapping and fighting.

But the problem at the moment is that we have a federal government that wants a “mature” debate on tax but has ruled out most areas of potential reform, or has placed various conditions such as with any changes to the GST making agreement unlikely. They will probably just keep on playing the blame game like kids. There will be plenty of talk but in the end nothing much will be done.

August 20, 2015

British exploration of the Pacific Ocean

Exploration of the Pacific Ocean can be divided into several phases. The Spanish and Portuguese were active in the 16th and into the 17th centuries, starting with Ferdinand Magellan. The Dutch period of exploration was mainly in the 17th century, with Abel Tasman being the best known of their explorers. Then came the English and French phase in the 18th century. For the French, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville is perhaps the most well-known. The Englishmen who were famous for their exploration activities during this period were John Byron, followed by Samuel Wallis, Philip Carteret, and finally James Cook. Reasons for British exploration included expansion of the empire, trade, research and defence.

An exception to this pattern of exploration was the journey of Englishman Francis Drake in the 16th century. Queen Elizabeth I sent Drake to fight the Spanish on the Pacific side of the Americas in the Pelican in 1577. He captured a Spanish ship that was laden with gold near Lima, and chased and caught another ship with gold on board. This second ship had been sailing west for Manila, an area the Pope had given Portugal the right to explore. This led to a Spanish invasion of Portugal in 1580. Meanwhile, Drake claimed land somewhere north of Point Loma for the British. He attempted to find a western end to the Northwest Passage, but was forced back by freezing weather. He then crossed the Pacific to the Moluccas islands in modern-day Indonesia and returned to England via southern Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, becoming the first Englishman to circumnavigate the world.

John Byron first circumnavigated the globe as a midshipman. In 1741 his ship, the HMS Wager, was shipwrecked off the southern Argentina coast. He led a squadron to destroy fortifications built at Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, and later defeated a French flotilla at the Battle of Restigouche. He again circumnavigated the world in the mid 1760s, taking possession of the Falkland Islands. While on the Pacific Ocean leg of this voyage, Byron discovered various islands, including the Gilbert Islands, Tokelau and Tuamotus, as well as visiting Tinian Island in the Northern Marianas group. He was appointed governor of Newfoundland and was later the British fleet’s commander in chief in the West Indies during the War of Independence.

Samuel Wallis was sent by the British Admiralty in HMS Dolphin in 1766 to search for a continent that was believed to exist south of South America. In July 1767, he saw a mountain that he thought could be the new continent, but he had discovered Tahiti instead. The Tahitians threw stones, to which Wallis’s men responded by firing cannons. Next day, the explorers went ashore and planted the British flag and claimed possession. Two days later, armed Tahitians approached the Dolphin in canoes as well as the party on the land. Guns were fired and the warriors fled to the hills. Later that day, the Tahitians begged for peace with food and other gifts, and their young women. The Dolphin’s crew went ashore and the trading commenced.

Philip Carteret was a lieutenant on the Dolphin with John Byron. He then took command of the Swallow and accompanied Samuel Wallis on the 1766 voyage around the world. They became separated at the Magellan Strait at the southern tip of South America. Carteret went on to discover Pitcairn Island, and the Carteret Islands or Atoll near New Guinea. He also discovered the York Islands, and the Solomon Islands which probably hadn’t been sighted by a European since Spaniard Alvaro de Mendana 200 years earlier. His health suffered as a result of the expedition and he was put on half pay. He finally got a new ship, the HMS Endymion in 1779, and conducted a voyage to the West Indies.

James Cook is perhaps the best known of the English explorers in the Pacific. He was the first person to map Newfoundland, before making three trips to the Pacific Ocean. His first voyage of 1768-71 in HMS Endeavour started by sailing round Cape Horn at the bottom of South America and heading across the Pacific to Tahiti. As planned, he observed Venus’s transit across the Sun. He went on to circumnavigate New Zealand, producing a remarkably accurate map for the time. He crossed the Tasman Sea and reached the eastern coast of Australia in April 1770, being the first European to see this part of Australia, unlike the west coast which had been visited by many European explorers starting with Dutchman Willem Janszoon in 1606.

Cook’s first landing on the continent was at Botany Bay, on the south-eastern coast. A convict settlement was established 18 years later in 1788 just north of this area as a direct result of a favourable report by Joseph Banks, Cook’s botanist on the trip. The convict colony was Sydney, now the largest city in Australia, with a population of over four million. In 1779, in Cook’s absence on another voyage, Banks was called as a witness by a House of Commons committee set up to decide where Britain should send its convicts after the War of Independence stopped them from being sent to America. He mentioned the availability of fresh water, abundance of fish, arable soil, good pasture, plentiful timber and warm climate at Botany Bay. He also reported that the Aboriginal people were placid and disinterested, presenting little threat. Botany Bay was eventually selected for the convict settlement, but it moved to Sydney Cove after the original location proved inadequate within a week of arriving.

On his second voyage in 1772-75, James Cook was sent in HMS Resolution to find the great habitable landmass that was still thought to exist south of Australia and New Zealand. He crossed the Antarctic Circle in January 1773, and also claimed South Georgia for Britain. He became separated from his companion ship HMS Adventure captained by Tobias Furneaux who continued on to New Zealand where a number of the crew were killed in a fight with the Maoris. Cook sailed well south of the Antarctic Circle, but didn’t quite reach the Antarctic mainland. He then headed north, all the way to Tahiti. He also visited Easter Island, the Friendly Islands or Tonga, New Caledonia, Vanuatu and Norfolk Island. Cook was able to make very accurate maps with the help of the ground-breaking Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer. This voyage also put an end to the Terra Australis myth.

James Cook’s third and last voyage took place on the Resolution in 1776-79. Its main purpose was to find the Northwest Passage to the north of Canada, thereby linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. On this trip, he went to Tahiti and then became the first European to see the Hawaii Islands. He mapped for the first time the western coast of North America right up to the Bering Strait, between Russia and Alaska, but found it to be impassable. He returned to Hawaii. After several months, he departed the islands but was forced to return due to a broken foremast. It seems that Cook’s return was not welcomed by the Hawaiians. There was quarreling and one of Cook’s boats was taken. He tried to take their king as hostage. The villagers prevented this and he was struck on the head and stabbed to death in the shallows.

The British Empire’s exploration of the Pacific Ocean achieved some remarkable things. The west coast of America and the east coat of Australia were charted for the first time, and many islands were discovered. Accurate maps were drawn for the first time. Cook had extensive contact with the people of the Pacific and correctly concluded that their ancestors had come from Asia. More than 3,000 plant species were collected, which were of great value to botanists in Britain. A favourable report by Cook’s botanist Banks resulted in the settling of Australia by Europeans.

August 19, 2015

Australian political situation

I follow the political situation here in Australia and post comments to a few sites from time to time. I posted one yesterday to Business Spectator (http://www.businessspectator.com.au/news/2015/8/18/national-affairs/leadership-talk-swirls-around-coalition):

A Morgan poll in July had Turnbull as preferred Liberal Party leader by 44% of people (up 6% from April). Bishop had 15% of the vote (down 12%). Abbott was on just 13% (up 1%). Coalition voters had Turnbull at 32% (up 2%), Abbott 26% (up 1%), Bishop 16% (down 9%), Morrison 13% (up 5%), Hockey 4% (unchanged). Turnbull would perhaps be the Coalition’s only chance of a second term, given it would need to convince a lot of swinging voters to change their minds.

Labor would obviously prefer Abbott to remain and it seems there’s a good chance the Coalition might be silly enough to oblige. They’ve painted themselves into a corner on this after endlessly criticising Labor’s leadership changes, although the Coalition had four leaders in two years: Howard, Nelson, Turnbull, Abbott. But the Coalition paints itself into various corners criticising Labor and then does a worse job themselves. The budget is a good example. But they still carry on like vengeful schoolkids blaming everyone and everything for their problems but themselves.

You would think something has to give. The latest Morgan poll is at 57:43 in favour of Labor. The poll is much larger than the others and includes people who only use a mobile phone. It’s hard to see this improving with the Coalition’s efforts on marriage equality and climate change.

A number of polls have shown that support for marriage equality is 68-72%, yet the Coalition (read Abbott) has decided to draw the issue out for years, ensuring plenty of internal bickering, and then perhaps have a referendum at a cost of $150 million to find out something we already know: that support for marriage equality is high.

On climate change, they’ve gone with a weak emissions reduction target and prefer non-renewables.But the Climate of the Nation 2015 survey found that 84% of people had solar in their top three preferred energy sources, followed by wind with 69%, gas 21%, nuclear 13% and Abbott’s coal 13%. The same survey found that more than three-quarters of people felt the polluters should pay, not the taxpayers. But carbon pricing is gone and we now have the expensive, ineffective Direct Action policy where the taxpayer pays. The Parliamentary Budget Office estimated the cost to the budget of abolishing carbon pricing to be $18 billion over four years. Surveys have shown that people (and especially economists) prefer carbon pricing to Direct Action.

Then there’s the Dyson Heydon saga.

How many nails do you need in a coffin? It’s quite possible Abbott and the Coalition will think of some more.

Comment by Andrew: “good summary Chrispy”

Comment by Rich: “Thank you for the BEST REASONED, FACT-BASED ANALYSIS I’ve seen ANYWHERE about the current malaise in our Federal political situation!!”

Thanks guys. Yes, it really is a malaise that surely can’t continue medium or long term. Will be interesting to see what happens. Anyone’s guess really. Perhaps the only safe bet is that Tony Abbott won’t be there long term.

August 18, 2015

Reasons for the British Empire’s colonisation of Australia

Transportation of undesirables had long been an issue in Britain. Under the Vagabonds Act of 1597, England expelled its lawbreakers across the Atlantic. Banishment to the New World accelerated with the Transportation Act of 1717, before coming to a halt with the outbreak of the American War of Independence or American Revolutionary War between Britain and the 13 former colonies in 1775. Transportation may have stopped soon after this time in any case. The American economy already relied on slave labour from Africa, and British convict labour was no longer required.

English prisons were soon overcrowded with paupers caught stealing food and clothing, as well as debtors without the means to discharge their obligations. As a temporary solution, the British Government converted old wartime sailing ships into floating jails called “hulks”, mooring them on various rivers and harbours. England thought the war in America would soon be over and transportation would be resumed.

But the war dragged on and, in 1779, the House of Commons set up a committee to decide where Britain should send its convicts. It called upon a number of witnesses. One was Joseph Banks who was the botanist on Captain James Cook’s first expedition of 1768 to 1771, which had sailed along the previously unexplored east coast of Australia in 1770. Cook was unable to attend the hearing as he was on his third voyage. Banks reported favourably on Botany Bay, just to the south of Sydney Cove. He mentioned the availability of fresh water, abundance of fish, arable soil, good pasture, plentiful timber and warm climate. He felt that a convict colony would be self-supporting in a year. Banks spoke of the Aboriginal people and their placid, disinterested nature, presenting little threat.

The expedition had also visited New Zealand, and Banks told the committee how the Maoris had greeted them with stones and the “haka”, an aggressive war dance still used at the start of rugby union matches between New Zealand and Australia. New Zealand was eliminated as an option for a convict settlement. Other witnesses presented cases for Gibraltar and western Africa. In the end, the committee made no decision, but the issue wouldn’t go away, especially due to chronic overcrowding and disease in prisons and on the hulks.

Much discussion took place in the first half of the 1780s on where Britain should set up a convict colony. Three main reasons were suggested for establishing a settlement in Australia. There was of course the problem of large numbers of convicts and nowhere to send them. The second reason was to do with economics. Britain had increased its trade substantially with the Far East, in particular India, south-east Asia, and China. The third reason was for defence purposes. A naval post would help keep the French and the Dutch away. Also, Australia, and especially Norfolk Island, 1000 miles or 1600 kilometres east of the mainland, had a good supply of tall pine trees and flax for replacing navy ship masts. In 1783, James Matra, who had been a midshipman on Cook’s first voyage, proposed a settlement at Botany Bay for strategic reasons and the pine and flax on Norfolk Island. When his plan was largely ignored, he suggested that convicts could be sent to this outpost.

The British Parliament passed the Transportation Act of 1784, once again allowing convicts to be sent overseas, but it didn’t specify an actual location. Plenty of suggestions were made at the time, including Botany Bay, Norfolk Island, and Lord Howe Island, 400 miles east of the mainland. A number of places in Africa were also proposed, such as Gromarivire Bay east of Cape Town, Madagascar, Tristan da Cunha, Das Voltas Bay at the mouth of the Orange River in south-west Africa, and 400 miles up the Gambia River in West Africa. By 1785, Das Voltas Bay was leading the race due to strategic and trade reasons. There were rumours of copper in the mountains. But a survey team found the location too dry for settlement.

Botany Bay became the government’s preferred option. A proposal was drawn up and approved by cabinet to transport convicts to this place, with Captain Arthur Phillip as expedition leader and governor of the new colony. The First Fleet of about 1400 convicts, crew and officers left England on two naval vessels and nine convict ships on 13 May 1787. They reached Botany Bay on 19 January 1788. But no one had visited the area in 18 years and it was found to be too open to offer protection. The soil was poor, fresh water was lacking, and the convicts’ tools broke when they tried to chop down the hardwood trees. The colony moved to Port Jackson, just to the north, on 26 January, to a spot that is now part of downtown Sydney. This date is now celebrated as Australia Day each year and is a public holiday.

Colonisation soon expanded outside the initial area. The main reason for this was to grow enough food for the colony. Settlements were established at Parramatta and to its north and west, as well as along the Hawkesbury River. The Hunter Valley to the north was opened up in 1797 when coal was found. The first of the penal colonies for convicts who had committed another crime since their arrival in Sydney was set up at Newcastle, 100 miles to the north, in 1801. John Macarthur launched the wool industry at Camden, 35 miles from Sydney, in 1805.

By the 1810s, reasons for further colonisation turned to growth of a successful, prosperous and expanding colony. Governor Lachlan Macquarie encouraged settlers to grow extra crops, go to church, and get married. He closed many of the public houses, and undertook an extensive program of public works, such as a market place, public storehouses, a new hospital, convict and military barracks, and better streets and roads. He sent an expedition to find a way over the Blue Mountains so that the vast interior could be opened up to farming and industry.

The reasons for colonisation were not solely economic and social. In the 1820s, more colonies of secondary punishment were established at Wellington Valley, Port Macquarie, and Moreton Bay in the 1820s. The latter is more than 500 miles north of Sydney and became the city of Brisbane. A separate convict colony had been set up at Hobart, Tasmania in 1803. Norfolk Island hosted convicts on two separate occasions. A settlement was established on Melville Island, Northern Territory in 1824 to open up trading with Indonesia and ward off the French.

A military settlement was started at Albany south of Perth in 1825, also to keep the French away. The colony of Swan River was established in Western Australia in 1829, on the site of present day Perth. This settlement was established to receive convicts and also due to a rumor that the French were about to set up a colony somewhere along the western coast. This part of Australia had been explored by several countries over a period of nearly 200 years but colonisation did not occur, probably as it was so far away from anywhere and largely desert.

A primary reason for colonisation continued to be as a place to send convicts. Over a period of 80 years from 1788 to 1868, Australia received 158,829 convicts, consisting of 134,261 males and 24,568 females, mainly from England and Ireland. They were employed on public works or assigned to free settlers, many of whom were farmers. Most convicts were transported for theft. Sentences were usually seven or fourteen years. Only about 5% of convicts ever returned to Britain. Convicts were instrumental to the colonisation and development of Australia.

Two major free settlements were started in the 1830s. The Port Phillip colony and the town of Melbourne commenced in 1835. A gold rush to the north and north-west of the town in the 1850s brought large numbers of migrants to the region. A colony at South Australia was formed in 1836, also without convict labor. Here, systematic colonisation was based on the plan of Edward Wakefield. Land was sold to settlers rather than given as grants, as in other colonies. The proceeds would be used to ship laborers to the colony rather than using convict labor.

In summary, the colonisation of Australia took place for various reasons. The underlying reason was to establish colonies where Britain could send its lawbreakers. Economics and defense also played their part in the decision to choose Australia over other places. Further colonisation was due to these three reasons plus additional factors such as the desire to build successful and prosperous communities, and the discovery of gold.

August 17, 2015

How the Industrial Revolution started

In the late 18th century, something happened in Manchester, United Kingdom, that had never occurred anywhere before – the city experienced what would later become known as the Industrial Revolution. It was not a true revolution, characterized by sudden change, but rather an evolution over about seventy years from around 1770 to 1840, which took Manchester and nearby towns from a rural based society to a manufacturing one. In the process, the structure of family life changed completely, from one dominated by agriculture and cottage industries in the country to one of large factories in ever expanding cities and towns. But why did it start in Manchester?

The answer lies in its association with cotton. As early as 1282 a cottage industry existed in Lancashire, making articles of linen cloth and wool. By 1600, production extended to other fabrics such as cotton wool and fustian, or coarse cotton, made of raw materials from the Near East. A hundred years later, cotton became the most important industry in the Manchester area due largely to its moist climate and lime free water, making fiber easier to weave than in other parts of the country. Larger markets and better transport facilities led to strong growth in both the cotton industry and in the Manchester population between 1730 and 1770. The colonies of North America, for example, became not only an important supplier of raw cotton but a market for finished goods.

England had been a major producer of wool, coal and tin, and had well established trade links with Europe since medieval times. But industry was conducted from homes either in the countryside or in villages, and in the case of mining, by small local firms. In the mid 18th century all cotton was still hand spun. A series of inventions during the second half of that century had far reaching ramifications, not only for the cotton business but for society in general.

Rapid expansion of the industry meant the spinners could not produce enough weft on their linen warps to keep the weavers in work. This problem led to the invention of the spinning jenny in 1764 by James Hargreaves, a former weaver of Blackburn. The jenny enabled a person to spin several yarns at once. Successive jennies soon became too large to fit into the village homes of spinners and had to be placed in workshops or factories. Economies of scale were kicking in, where large scale production meant far greater output for a given level of inputs compared with home industry.

Around 1770, Preston barber Richard Arkwright developed the water frame, to be driven by water power in a factory. When Samuel Crompton of Bolton introduced his spinning mule in 1779, a combination of a jenny and a water frame, the burgeoning factory system grew quickly. Factories, large and small, sprang up all over Manchester and surrounding towns. Steam power, first used in 1787, enhanced this growth as it meant factories no longer relied on water power and were not confined to locations beside streams often in the countryside. Growth was also boosted by the expanding overseas markets in Europe and elsewhere. The nearby town of Liverpool became a major port. Further improvements in road and river transport contributed to the rise of large scale industry.

Cotton workers throughout Lancashire and other English counties found they could no longer compete with the new cotton mills. Carding and spinning – traditionally undertaken at home by women and children – were done almost solely in factories by the 1790s. The weavers hung out but their pay diminished dramatically over ensuing decades and they too were forced to abandon their home based handlooms. Thousands of families had no choice but to leave their villages and migrate to the cotton towns and cities to obtain work. The population of Manchester grew from 15,000 in 1750 to 90,000 in 1800, making it the second largest urban area in England behind London.

The downside was that living and working conditions were atrocious, disease was rampant, education and literacy fell away as children worked full-time in factories, and local government services were virtually non-existent. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that these things gradually improved as a result of political pressure by various groups, including the fledgling trade union movement.

A similar industrial transition took place in other parts of Britain from the early 19th century before spreading to Europe, the United States, and later throughout most of the world. But it was in Manchester, United Kingdom, that the conditions were right for it to lead the way in creating an industrialized world that was to dominate society for most of the 19th and 20th centuries before service industries became dominant.

August 15, 2015

Peterloo update

Further to the excerpt I posted yesterday on Peterloo from my novel A Weaver’s Web (https://chrispearce52.wordpress.com/2015/08/15/a-weavers-web-novel-excerpt-the-wakefields-at-peterloo/), the anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, Manchester, UK is on 16 August. The Peterloo Picnic has been held each year since 2007 to commemorate the event that occurred back in 1819. In 2015, it will be held outside the Manchester Central Conference Centre, 1-3pm. For more about the picnic and the massacre, see http://www.peterloomassacre.org/.

I wrote a guest post on Peterloo for Catherine Curzon and this was published on her site last Friday, 14 August. See http://www.madamegilflurt.com/2015/08/a-lost-child-at-peterloo.html.

Mike Leigh is making a film on Peterloo. The filming of Peterloo starts in 2017 and it is expected to be released in 2018 in plenty of time for the 200th anniversary of the massacre the following year. See http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/apr/17/mike-leigh-to-make-movie-of-peterloo-massacre. Mike’s last film, Mr Turner, won two awards at the Cannes Film Festival and a number of other awards, and got four Oscar nominations.

August 14, 2015

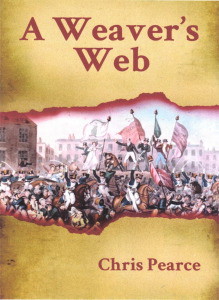

A Weaver’s Web novel excerpt: The Wakefields at Peterloo

(based on what happened at a reform meeting of 60,000-80,000 people at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, UK on 16 August 1819 that became known as the Peterloo Massacre)

In the hot afternoon sun, the yeomen moved along what was left of the gap, towards the hustings. But they were unskilled in such manoeuvres and the noise of the crowd unsettled them and their horses. The people wanted nothing of them and tried to close ranks. In response the yeomen lashed out with their sabres, but missed their targets. Cries of ‘Soldiers, soldiers!’ went up among the crowd. Some of the people tried to get out the way while others stood their ground and waved sticks, which country folk often carried when they went out.

Henry and Sarah [Wakefield] weren’t far from all this and grabbed the children’s hands as people started screaming and running, though at fourteen Albert wasn’t keen to have his hand held.

From the hustings, [Henry] Hunt tried to reassure the crowd. ‘Stand firm, my friends. You see they are in disorder already. This is a trick. Give them three cheers. Hip, hip …’

A loud ‘hooray’ went up.

‘Hip hip …’

A second ‘hooray’ was louder and longer than the first.

‘Hip, hip …’

The third ‘hooray’ shook the earth, and the magistrates.

‘They’re defying us,’ Norris said.

‘More than one can play at this game,’ Hulton said. ‘Messengers,’ he called to several of them in the room, ‘get everyone on our side to cheer at the top of their voices and then get the yeomen to make the arrests.’

Much cheering followed, but it came from both sides.

The Wakefields joined in the revelry along with thousands of other families.

‘Henry, look up the back,’ Sarah said. ‘The cavalry and the constables and loyalists are cheering. They’re joining us.’

‘It may be a ploy,’ Henry said.

The cheering soon stopped as the yeomen, many abreast, rode through the crowd. At first they went slowly, but then made their horses go faster. The gap left by the constables had closed up and swarms of people were pressed between the soldiers and the hustings. Men, women and children screamed as they were trampled by the yeomen’s horses or cut by sabres. No mercy was shown by the yeomen. They lashed out at those on the hustings, some falling to the ground. The rest were forced to climb down. Less ruthless were the hussars who had now arrived. They used the flats of their swords rather than the edges as the yeomen were doing.

Captain Birley, leader of the Manchester Yeomanry, spoke to Hunt. ‘Sir, I have a warrant against you and arrest you as my prisoner.’ He waved it in front of Hunt who stayed on the platform.

‘Remain calm,’ Hunt bellowed to the crowd, ‘and don’t put up any resistance.’ He then turned to Birley. ‘I willingly surrender myself to any civil officer who shows me his warrant.’

Nadin stepped forward. ‘I will arrest you,’ he said. ‘I have information upon oath against you.’ Hunt didn’t resist, and was arrested and taken away.

Other arrests were made in the same way. But soon after Hunt’s capture, the Manchester yeomen cried out: ‘Destroy their flags,’ and began slashing at the banners attached to the hustings and then at the ones in the crowd. More people were crushed and cut.

The crowd panicked and large groups tried to flee, but all exits from the field were blocked by extra yeomen and hussars who had gathered on the perimeter. But the local yeomen panicked too, and were in complete disarray as they rode their horses wildly through the crowd. People tried to defend themselves but most were unarmed. Some had their sticks, and a number of rocks and brickbats were thrown, but these were no match against the yeomen’s horses and sabres.

Hussars leader Colonel L’Estange rode up to the magistrates’ house and called to Hulton who was at the window. ‘What do you want me to do, Sir?’

‘Good God, man! Do you not see how they are attacking the yeomanry? Disperse the crowd,’ Hulton said without consulting the other magistrates.

‘Very well, Sir.’ L’Estange led the Fifteenth Hussars into the crowd.

Cavalry rushed about in all directions and hundreds of citizens were thrown to the ground. Most got up and continued their desperate attempts to scramble free. Henry was knocked to the ground trying to protect Sarah and the children as a horse rode over the top of them. He got up holding his shoulder, only to be knocked down again. People stumbled over him trying to get away. He thought he could hear Sarah screaming ‘Catherine’ several times, but he couldn’t see either of them. As he crawled along looking for them, his face covered in blood and dirt, he saw people staggering and limping, some supported by their families and friends. And he saw other folk lying motionless as frantic loved ones tried to help them. He got to his feet but everything spun. He tripped over belongings left behind and over a number of people crawling about. He went with the general flow of those nearby, calling out: ‘Have you seen my family,’ but they didn’t know him or where his family might be.

end of excerpt

The magistrates can be seen at a window of the building on the left-hand side of the image from Peterloo on the front cover of A Weaver’s Web, below.