Lewis DeSimone's Blog, page 4

February 12, 2012

Rigoberto González on The Heart's History

I'm excited to pass along more praise for The Heart's History, from another award-winning writer.

Rigoberto González, author of The Mariposa Club and Butterfly Boy, winner of the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, states:

"With admirable sensitivity, Lewis DeSimone reaches deep into a close community of friends to explore the textured lives of gay men, their urgencies haunted by the traumas and anxieties of the past, illuminated by their current (sometimes troubled) affinities and relationships. At the center of this circle is the endearing couple, Robert and Edward, their touching story a catalyst that allows those near them (including the reader) to consider the power of commitment, the grace of forgiveness. The Heart's History is a stunning portrait of love."

That last phrase is the new tag line for the novel. Thanks, Rigoberto!

February 5, 2012

Michelle Tea on The Heart’s History

Michelle Tea and I go way back. Or at least we should. We both grew up in Chelsea, Massachusetts, a sad little town just north of Boston, which Michelle immortalized in her wonderful memoir, The Chelsea Whistle. We didn’t know each other back in Chelsea, but met several years later, once we had both settled in San Francisco.

Michelle, of course, has become a literary star with such works as Rose of No Man’s Land and the Lambda Award-winning Valencia. So, of course, she was one of the first people I thought of when it came to requesting advance reviews of The Heart’s History. Here’s her take:

“Lewis DeSimone is a great writer. His prose is thoughtful, deep, layered and real. His characters are living. It’s about love and sex and AIDS, about human connection and the ultimate unknowability of another person. It’s about the slow assimilation of a larger gay culture that used to be more angry and badass. It’s a really good book written by a very skilled author.”

Coming from one of the most “bad-ass” writers I know, that’s a real compliment.

Michelle Tea on The Heart's History

Michelle Tea and I go way back. Or at least we should. We both grew up in Chelsea, Massachusetts, a sad little town just north of Boston, which Michelle immortalized in her wonderful memoir, The Chelsea Whistle. We didn't know each other back in Chelsea, but met several years later, once we had both settled in San Francisco.

Michelle, of course, has become a literary star with such works as Rose of No Man's Land and the Lambda Award-winning Valencia. So, of course, she was one of the first people I thought of when it came to requesting advance reviews of The Heart's History. Here's her take:

"Lewis DeSimone is a great writer. His prose is thoughtful, deep, layered and real. His characters are living. It's about love and sex and AIDS, about human connection and the ultimate unknowability of another person. It's about the slow assimilation of a larger gay culture that used to be more angry and badass. It's a really good book written by a very skilled author."

Coming from one of the most "bad-ass" writers I know, that's a real compliment.

January 29, 2012

Read an Excerpt from "The Heart's History"

January 24, 2012

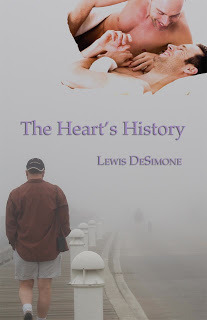

Announcing my new novel, The Heart's History

I'm thrilled to announce that my next novel, The Heart's History, will be published by Lethe Press in May 2012.

I'm thrilled to announce that my next novel, The Heart's History, will be published by Lethe Press in May 2012. From the cover:

This is Edward—architect, friend, lover, mystery. Everyone has their own Edward—a kaleidoscope of images struggling to define a man who has never let anyone get too close. But now, Edward is dying, and all of his loved ones are desperate to understand him, to connect fully with him, before it's too late.

In this beautiful and haunting novel, Lewis DeSimone, author of the acclaimed Chemistry, explores the hidden depths of love, the struggle to maintain a balance between connection and individuality. Edward's illness is set against the backdrop of a sea change in gay culture, a time when AIDS is assumed to be simply a manageable condition, and when the drive for assimilation—through marriage, or the military—has begun to trump the distinct characteristics that were once a source of pride. Deftly shifting perspectives to paint a compelling portrait of a man and a community on the cusp of a critical transition, The Heart's History gives hope that, despite the impossibility of ever achieving true oneness with another person, it is the attempt itself that gives life its greatest joy.

***

I'll be posting more about the book as the publication date approaches. In the meantime, it's available for pre-order at amazon.

September 26, 2010

Eat, Pray, Throw Up

When I learned that Julia Roberts had gotten the lead in Eat, Pray, Love, I was at first appalled. How on earth could an actress whose range extends all the way from the feisty but shallow Pretty Woman to the feisty but shallow Erin Brockovich ever play someone on a spiritual quest?

Then I read the book. And now I believe that Roberts—who, despite attempts at girl-next-door cuteness, is really best at playing selfish bitches—is, once again, perfectly cast.

If the definition of insanity is doing the same thing again and again while expecting different results, then I've grown one step closer to the loonybin each time I picked up a memoir and hoped to actually like it. The truth is that memoirs don't get much better than Eat, Pray, Love. And that's the problem: memoirs don't get much better than Eat, Pray, Love. In other words, memoirs pretty much suck.

I did start out liking the book—really, I did. I especially enjoyed the Italy section: hey, I'm of Italian origin, I love pizza and gelato and flirtatious men—what's not to like?

But it didn't take long for my mood to turn. About a third of the way through, I realized I didn't like the narrator. Still, I thought, that was hardly a deal-breaker: I've read Ayn Rand novels, for god's sake; I'm used to self-centered heroines.

But as the book went on, the narrator became more and more obnoxious, and I could no longer pass my distaste off as interesting. The genre itself was the problem, I soon realized: in a novel, the author has the luxury of hiding behind a character, and she can make the character as bitchy as she wants without earning the ire of her reader. But in a memoir, that defense is gone: in a memoir, the narrator (however obnoxious) is, as far as the reader knows, indistinguishable from the author. That is the point, after all, isn't it?

So, in the end, it wasn't just the narrator of this book I disliked: it was the author herself.

But even that didn't completely explain my growing revulsion for the book. I've hated authors before and still liked their work (once again, Ayn Rand comes conveniently to mind).

No, I decided, ultimately not liking the author wasn't the problem, either. The problem was that I didn't trust the author. I didn't trust her one bit.

And that, I realized, is the key for me with any work. Whether it's a memoir, a novel, a poem, or a recipe, I don't have to like the author, but I do have to believe that she's not selling me a bill of goods.

Unlike Oprah, I was not surprised when James Frey's alleged true story fell into a million little pieces. After all, he had written it first as a novel and called it a memoir only because memoirs sell better in the confessional age that Oprah herself helped to create.

As I understand that controversy, the problem was simply that Frey was passing off the fictional as the real. I fear the problem with Eat, Pray, Love goes a lot deeper. Or, more to the point, a lot shallower.

I've read a lot of memoirs and a lot of novels, and one thing that all those pages have taught me is this: there is a great deal more truth in fiction than in memoir. Not verisimilitude—this happened and then that happened; she was wearing a red dress—but truth of character and purpose, self-awareness.

Memoir, this genre that in recent years has come to take up 50% of bookshelf space (if you can find a bookshelf in the Kindle age), is comprised largely of whiny exercises in self-pity and/or self-aggrandizement—but precious little self-awareness. This is the genre of "Mommy, look at me!" And frankly, I can understand why Mommy turned away in the first place.

My suspicion was aroused early on, when Gilbert refuses to elaborate on the reasons her marriage fell apart, claiming respect for her ex-husband's privacy: "I don't think it's appropriate for me to discuss his issues in my book." But as I got deeper into the story—300 pages of "me, me, me," and we all know how enlightened and spiritual that is—I started to develop my own theory about why the relationship ended.

One thing Gilbert does reveal at the beginning of the story is that she signed a contract for the book before her year's journey began—in other words, this year of spiritual discovery started with a paycheck. Along the way, her narrative notes a lot of gastronomic pleasure in Italy, a budding romance in Indonesia, and one briefly described but profound meditation in India (which quickly pales into the background once said love affair begins in the next chapter).

Then, near the end we get the longed-for climax. And it's a flashback.

When it comes time to reveal her most profound spiritual experience, Gilbert tells us about her first trip to Indonesia—before the year of pilgrimage that constitutes the arc of this book. And the experience is lovely—the kind of enlightened moment many people strive for. But she had it before the story of this book began. She had it before she signed the contract and got her advance.

I spent 300 pages with her, waiting for the epiphany that she could have revealed on page 25 if she'd chosen to tell her story chronologically. But instead she chose to construct a narrative that is at its heart false: this is not a spiritual story any more than the beginning of the book is an open depiction of a marriage in crisis. It's as if Odysseus had already arrived home at the beginning of the poem and then spent 20 years sailing around the Aegean just for the hell of it.

Eat, Pray, Love is nicely written and humorous. (I haven't even touched upon how amusing are its Stepin Fetchit depictions of the Balinese—those whom the Great White Woman educates, enlightens, and buys houses for—with other people's money.) But at its core it is, for this reader at least, a manipulative exercise in disingenuousness.

The ad for the film shows Julia Roberts licking gelato off a spoon. How apt—delicious, sweet, and completely devoid of nutritional content.

December 1, 2009

Advent? What the heck are we waiting for?

Last week, I was asked to speak at my church, Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco, about my thoughts on Advent. Having recently become an atheist, I was concerned that my thoughts might not be received that well. But, as I discovered when I gave this talk, atheism is alive and well--even in church. MCC strives to be a multifaith organization, and it attracts people from every religious stripe--even those with no religion per se. My discussion opened a dialogue, and the atheists in church came rushing out of their closets. Richard Dawkins would be proud.

*****

When I was a child, December was all about anticipation. I spent the entire month, from Thanksgiving on, looking forward to Christmas. But, of course, my sense of expectation had nothing to do with Christianity per se, or even Jesus. What I spent the month waiting for was presents.

I would scour toy ads in the newspaper, circle the items I wanted, and not so discreetly leave the clippings where my parents would see them. This was sometime after my belief in Santa Claus had faded: I knew it was my parents I had to work on, and that no one was checking to see whether I was naughty or nice. Besides, I was always nice. I deserved everything I wanted.

And sometimes I actually got it. On one particular Christmas morning, I got spoiled more rotten than usual. At one point, surrounded by toys and a pile of discarded wrapping paper as high as a snowdrift, my mother passed me another present and I started to cry. "No more!" I wailed, exhausted. Now really, what child complains that he has too many toys? I still haven't figured out what that moment says about me.

But it does say something about Christmas. I spent a month waiting for toys, a month of delicious anticipation, imagining the moment when I would walk up to the tree and find the mound of brightly colored boxes with my name on them; imagining the toys that would litter the floor that afternoon as I ran from one to the other as my interest waxed and waned. I spent a month wanting. And then I got what I wanted. And it was too much.

Too much, or not enough? Was I in despair because I thought I didn't quite deserve such largesse? Or was I upset rather because it wasn't enough? Because what I really needed was something that didn't come in a box.

It wasn't until my twenties that I really understood that—long after the toys had dried up and my presents became more pedestrian things, like sweaters and books and Madonna albums. (The other Madonna, not the one in the Christmas story.) As an adult, I was no longer looking through a glass darkly: I saw the truth, face to face. Christmas, in my parents' home, was inevitably about presents and food. That was how my parents showed their love: my mother bought us things, and my father cooked. And they fought. Every Christmas, like clockwork, they fought. But why should Christmas be different from any other day?

We watched Charlie Brown and listened to Linus tell the story of the baby Jesus. We even went to church on Christmas Eve, now and then, and sang the hymns. I fell in love with the story of Jesus, but I saw it only as a story. I think I always saw it only as a story—no truer, in a literal sense, than Homer's Odyssey, or Peter Pan. I got presents for Christmas, more than I needed, more than I wanted. What I didn't get was peace. What I didn't get was a true sense of connection, the image of family I watched every week on The Waltons. Ultimately, Christmas was hollow. And in my twenties, I began to dread it—the long flight back east to visit a squabbling family, where the Christmas spirit was as much a myth as Santa Claus himself.

Frankly, I don't understand Advent. If God is eternal, then what are we waiting for? If the Messiah has already come, why do we need to watch the clock for his arrival every year? And if the Christmas spirit fills the world only on December 25, then what's the point?

Life, they say, is what happens when you're making other plans. And I have always had lots of plans. I would be happy, I thought, when I moved into a bigger home. And I was, for a few hours. I would be happy when I published my first novel. And I was, for a few days. I would be happy when I fell in love. And I was, until it ended. … So I would be happy the next time I fell in love. And I was, until that ended. And then the next one … well, you get the picture.

The achievement of each goal merely led me to another goal. And I found that I was constantly living for the future, constantly waiting. Every season was advent. I was making plans, hoping for the future, and in the meantime, life was passing before my eyes.

Waiting—hoping, imagining a happy future—is, in the end, a distraction. If I focus on the happiness to come, I won't have to think about what's wrong in the present. Hoping gives me permission to be lazy. All I have to do is wait, and one day I'll be happy.

Well, ultimately, it doesn't work like that. Ultimately, the present is all we have, and I am responsible for mine. The present is where the future comes from. It doesn't come from a star hovering over a stable, or a deity dropping down from a cloud for 33 years, or staying on the cloud and listening to prayers.

In the end, this moment—now … and now … and now—is all we have. We don't need to wait for Christmas. We have our present already.

September 3, 2009

The Voyage In

I recently finished reading Virginia Woolf's debut novel, The Voyage Out. It had been sitting on the to-read shelf of my bookcase for months—but each time I returned to that shelf, in search of new reading material, my hand strayed from its spine, intimidated by the memory of how challenging Woolf can be. Inevitably, I would forsake her for something more accessible, less taxing. But recently, when I was in the midst of a serious bout of anxiety, a dear friend told me that Woolf was precisely what I needed. I needed the validation of the inner life that her work offers, to counteract the doubts I was having about my own obsessive wrangling with identity and the boundaries between myself and others.

And so, I cracked open the book at last. I was expecting another Mrs. Dalloway, another To the Lighthouse, something dense with stream-of-consciousness narrative and elusive storytelling. But what I found was quite different. Yes, Clarissa and Richard Dalloway do make their indelible appearance in the book, but the narrative style is much more accessible than Woolf's mature work, the plot more straightforward—almost, dare I say it of a Woolf novel, linear.

Like her later work, The Voyage Out veers from the consciousness of one character to another, often in the course of a single paragraph, so that one has to keep looking back to keep track of whose head one is in at any given moment. But if the gist of most of Woolf's work is that, essentially, nothing happens—that is, nothing much external, the sort of thing that passes for action in the vast majority of novels (marriage, death, car chases)—her first foray into full-length literature is quite different. On the surface, the plot is almost Victorian—a young woman, mourning the death of her mother, goes on a journey across the ocean and falls in love. That, in Woolf's world, is a lot of plot.

And yet, ultimately—and here is a key to Woolf's genius—the story is still an internal one. The title refers less to Rachel Vinrace's voyage across the sea than to her voyage deeper into her own psyche. Many of the passages describing her budding love for Terence Hewet are heartbreakingly beautiful—skating on just this side of sentimentality—and soon one realizes that Woolf is deliberately playing with the notions of Victorian literature, turning it on its head. Rachel is madly in love with Terence, and he is madly in love with her, and yet he ridicules her to her face as a silly woman, incapable of deep thought by mere virtue of her sex. They are completely ill suited for each other, and that very knowledge seems to be what confirms them in their relationship: they do not belong together, and so they must be together.

Not the ideal novel to read when one is in the midst of a romantic crisis. Or perhaps it was precisely the novel I needed to read. Rachel and Terence's story ends tragically, but the tragedy seems less a symbol of the nature of their relationship than a reminder of the fragility of all human bonds. In the end, Woolf's sense that we are all mysteries to one another is the whole point of her elusive style: she turns her attention to the minds of one character after another because none of them (including the narrator, including the author) has a handle on the whole truth, because—try as we might—none of us can ever really know what it is like to occupy someone else's skin. So while Rachel and Terence appear to be a bad match, who among these characters is a good one? Richard and Clarissa Dalloway? Well, there's a whole other novel to disillusion us of that notion.

One could read The Voyage Out, or any of Woolf's work, from a pessimistic standpoint—as testament to our inability to fully understand one another. That, one could argue, is the essence of the tragedy of the human condition: we continuously long for something we can never have. Or one can read the novel as a reminder that connection is actually ever-present. Woolf's fluid movement from one character's mind to another suggests, ironically, that they are all pieces of a whole—a single consciousness splintered into fragments, perhaps, but all connected, all one.

Several years ago, I reached a turning point in my writing career when I wrote the death scene for a central character in one of my (still unpublished) novels. After finishing his last chapter in the book, in which he has a deathbed conversation with a close friend, I turned off the computer and crawled into bed. And lying there in the dark, I began to sob. I sobbed over the death of someone who had never existed—a character I had created out of thin air, not even basing him on anyone I knew. I cried over the death of a character I didn't even really like that much. But something in the chapter moved me deeply, and I remember thinking: If this is what being a writer is, if good writing is always accompanied by this much pain, then I don't want it. Real life is painful enough without creating more opportunities to tear out my heart.

When I later workshopped the chapter, one of my fellow writers pulled me aside and confessed that it had had a similar effect on her. She, too, had cried at the death of my not-so-charming character. A light went on at that moment, and I understood why we do what we do, we writers. We rip our own hearts open in order to share their inner workings with the world. And in the process, we may even open our readers' hearts, too—push the boundaries of their own compassion, enlighten them about the lives of others, shine a light on our shared humanity, make a dent in the walls that separate us.

One March day, in her sixtieth year, Virginia Woolf put rocks in the pockets of her coat and walked into the River Ouse. The victim of a lifetime of anxiety and depression, she finally decided that she could no longer stand the pain. For decades, she had bled her pain onto the page—for the benefit of the rest of us—and I, for one, am extremely grateful. I am also humbled. My own pain can't compare. Neither, I fear, can my talent. But I can still live by Woolf's example: I can refuse the temptation to surrender to sentimentality. I can choose to bleed onto my own pages, to pour real life into my work, real life with all its pain and discomfort, all its contradictions. And in sharing that truth, I can reach out and join hands with you. Maybe then, we can pull each other out.

May 23, 2009

Tone Deaf

Let the record show that I gave up on American Idol weeks ago. Unlike last season, when there was some real competition, this time around I lost interest when the final 12 emerged and turned out to be a single great talent surrounded by 11 mediocre wannabes. I didn't tune in again until the two-part season finale, when I saw Adam Lambert predictably leave Kris Allen in the musical dust on Tuesday night. Of course, when the dust settled the next evening, it was—appallingly—Kris who was left standing.

I want to believe this absurd decision is simply another example of bad taste in a country where Lindsay Lohan is a big star and nobody's ever heard of Patricia Clarkson, where Dan Brown's pablum sells millions of copies while Philip Roth languishes on the top shelf. But this time I think there may be more going on.

Much has been made of Adam Lambert's ambiguous sexuality—the eyeliner, the flamboyant costumes that make him part Gene Simmons, part Elton John, and a whole lot of Freddie Mercury. So I suppose, in this age of Carrie Prejeans whose fake breasts are bigger than their brains, we should consider it a breakthrough that someone so probably gay made it even this far on today's ultimate homage to conformist Americana.

But in the end, America in its infinite wisdom decided it was willing to go only so far in its political correctness, and musical taste once again lost out to intransigent homophobia. And so Adam Lambert becomes the bridesmaid instead of the bride—and in a state where the likes of Miss Prejean have decreed that he shall never marry at all. Runner-up status is, one could argue, the reality-show equivalent of domestic partnership: Adam is equal, but separate.

Or perhaps it's a lot simpler than that. Perhaps the tween girls who make up the supposed majority of American Idol voters just wanted to vote for someone they could imagine kissing who might actually kiss them back. One hearkens back to the 2000 election, when many people preferred to vote for the guy they'd want to have a beer with (even though he was a recovered alcoholic) rather then the one who might actually do something.

I have nothing against Kris Allen per se. He's certainly talented, easy on the ears and the eyes. But the gap between his talent and Adam's is huge. Picture Halle Berry competing in the Miss America pageant against Janeane Garofalo—pretty, but hardly a beauty queen: who would you vote for?

Will Young, the very first winner of Britain's Pop Idol, all the way back in 2002, was gay. Now, seven years later, America still can't catch up—even when the truth is glaringly obvious.