Pankaj Sekhsaria's Blog, page 2

October 3, 2017

A review of Islands in Flux in Hindustan Times

Review: Islands in Flux by Pankaj SekhsariaAn important book provides insights into a region that is largely neglected by mainstream Indiabooks Updated: Sep 23, 2017 13:45 IST

Prerna Singh Bindra

Hindustan Times

http://www.hindustantimes.com/books/review-islands-in-flux-by-pankaj-sekhsaria/story-si2aDGc2dmmX98IjtNErxK.htmlFor the longest time, the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, rich with rare endemic wildlife remained on my wish list, inaccessible due to expense and distance. It was only in early 2005 that I made my way there to report the aftermath of the tsunami. The visit was turbulent – the island was reeling with the massive destruction unleashed, and a profound sense of loss. My brief stay was an unsettling mix of the exquisite and the tragic: my first, bewitching sight of the coral wonderland, walking the rich, riotous — and diminishing — rainforests that clothe the emerald islands, witnessing dead bodies being unearthed from under flattened homes and trees even three weeks post the tsunami, and the heartbreaking, haunting encounter with a once-proud people, the Jarawas, running after our vehicle, arms outstretched for a packet of biscuits. The cost of dignity, priced Rs 4. The tsunami, I gathered, was one among the many storms — none so pronounced — the islands had been battered by, their violence gradual, but no less virulent.

It is this steady invasion of the island, of its people, cultures and ecology, so that its original identity is subsumed that journalist and researcher Pankaj Sekhsaria has meticulously chronicled over the past two decades and brings together in the Islands of Flux. He calls it — bluntly and boldly, a colonization. The exploitation of the islands was started by the British who systematically logged the great forests for timber, unmindful of the animals and plants they housed, and the tribes that depended on it — an agenda followed with “clinical efficiency by a modern, independent India.” After 200 years of tyranny by a colonial power that fattened itself on the back of its people, land and resources, India gained freedom only to itself emerge as a colonizer. In the late 1960s, the Government of India had an official plan in place to “colonise” the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

This is the subtext that runs through the book, a collection of Sekhsaria’s articles, published in different newspapers and magazines. The pieces give insights into the islands — there are 572 in all, with only 36 being inhabited — their environment, wildlife, indigenous people, the influx of mainlanders, and their idea of development.

Massive deforestation took away from the tribals their means of sustenance. The consequent soil erosion killed live coral and marine life. The other onslaught was from settlers from mainland India — they encroached on and cleared the jungles, brought in disease, alcoholism, industry, and an economy alien to the local cultures. They ridiculed the Onges, the Great Andamanese and other tribal people — isolated for millennia — as ‘uncivilized’, making them outsiders in the land they belong to. Their numbers dwindled, and were soon vastly outnumbered. From instance, from being the sole inhabitants of Little Andaman, there are today over 120 outsiders for each Onge.

This exploitative vision has only worsened with successive governments, who have given a thrust to ports, industrial infrastructure and tourism, including inside sanctuaries and tribal reserves. Coastal and environment norms are being tweaked to accommodate these.

No contemporary record of the islands can be complete without the tsunami, which shifted the very geography of the islands. Sekhsaria delves on these wounds and suggests other far-reaching consequences one of which is escalating military activity. Owing to its strategic location — far from mainland India and close to Myanmar, and Indonesia, the archipelago has always been of strategic importance, serving as a launching pad and a look out post. Post tsunami, there was a flurry of defence activity and proposals. The Brahmos missile, test-fired on one of the remote islands, made news in March 2008. Other controversial proposals include a missile-firing testing system that would endanger the ground nesting of the endemic Nicobar megapode in the Tillanchong Sanctuary and a RADAR station in the only home of the Narcondam Hornbill on Narcondam Island.

The problem in this vision of development, a view of the islands as a military and economic colony is that it fails to consider the fragile ecology and the vulnerable indigenous communities. “The islands has always only existed on the margins of the consciousness of the nation. Did the earthquake and tsunami further ratify the fringeness of the fringe, allowing for experimentation, explosions and targeting in the interests of the Centre?” asks Sekhsaria.

The writing is elegant, the pen compassionate, the vision clear, even if the book is hampered by the fact that it is a collection of reports, hence lacking flow, and with a few overlaps across reports.

That apart, Islands of flux is an important book, providing a unique document from a region that rarely features in the mainstream media, and in dialogues in faraway Delhi. Even more lacking is an understanding of its unique wildlife, forests, people, culture and the intricate link between these, which the author writes of with finesse. This book is particularly relevant as the country sees mounting tensions from other such ‘colonies’ in the hinterland, where farmers, fisherfolk and tribal people are up in arms against the juggernaut of development: mines, ports, power plants, industries that erode ecology that sustains them, and a way of life.

The writer tackles this complex, nuanced subject with sensitivity and an insight backed with his years on the ground.

I hope that the book will bring the islands closer to the state that rules it but fails to serve it, and to tourists who visit it, unseeing and uncaring of their footprint. I know I need to visit again, to see the island with eyes anew.

The book is available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

The book is available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Prerna Singh Bindra

Hindustan Times

http://www.hindustantimes.com/books/review-islands-in-flux-by-pankaj-sekhsaria/story-si2aDGc2dmmX98IjtNErxK.htmlFor the longest time, the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, rich with rare endemic wildlife remained on my wish list, inaccessible due to expense and distance. It was only in early 2005 that I made my way there to report the aftermath of the tsunami. The visit was turbulent – the island was reeling with the massive destruction unleashed, and a profound sense of loss. My brief stay was an unsettling mix of the exquisite and the tragic: my first, bewitching sight of the coral wonderland, walking the rich, riotous — and diminishing — rainforests that clothe the emerald islands, witnessing dead bodies being unearthed from under flattened homes and trees even three weeks post the tsunami, and the heartbreaking, haunting encounter with a once-proud people, the Jarawas, running after our vehicle, arms outstretched for a packet of biscuits. The cost of dignity, priced Rs 4. The tsunami, I gathered, was one among the many storms — none so pronounced — the islands had been battered by, their violence gradual, but no less virulent.

It is this steady invasion of the island, of its people, cultures and ecology, so that its original identity is subsumed that journalist and researcher Pankaj Sekhsaria has meticulously chronicled over the past two decades and brings together in the Islands of Flux. He calls it — bluntly and boldly, a colonization. The exploitation of the islands was started by the British who systematically logged the great forests for timber, unmindful of the animals and plants they housed, and the tribes that depended on it — an agenda followed with “clinical efficiency by a modern, independent India.” After 200 years of tyranny by a colonial power that fattened itself on the back of its people, land and resources, India gained freedom only to itself emerge as a colonizer. In the late 1960s, the Government of India had an official plan in place to “colonise” the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

This is the subtext that runs through the book, a collection of Sekhsaria’s articles, published in different newspapers and magazines. The pieces give insights into the islands — there are 572 in all, with only 36 being inhabited — their environment, wildlife, indigenous people, the influx of mainlanders, and their idea of development.

Massive deforestation took away from the tribals their means of sustenance. The consequent soil erosion killed live coral and marine life. The other onslaught was from settlers from mainland India — they encroached on and cleared the jungles, brought in disease, alcoholism, industry, and an economy alien to the local cultures. They ridiculed the Onges, the Great Andamanese and other tribal people — isolated for millennia — as ‘uncivilized’, making them outsiders in the land they belong to. Their numbers dwindled, and were soon vastly outnumbered. From instance, from being the sole inhabitants of Little Andaman, there are today over 120 outsiders for each Onge.

This exploitative vision has only worsened with successive governments, who have given a thrust to ports, industrial infrastructure and tourism, including inside sanctuaries and tribal reserves. Coastal and environment norms are being tweaked to accommodate these.

No contemporary record of the islands can be complete without the tsunami, which shifted the very geography of the islands. Sekhsaria delves on these wounds and suggests other far-reaching consequences one of which is escalating military activity. Owing to its strategic location — far from mainland India and close to Myanmar, and Indonesia, the archipelago has always been of strategic importance, serving as a launching pad and a look out post. Post tsunami, there was a flurry of defence activity and proposals. The Brahmos missile, test-fired on one of the remote islands, made news in March 2008. Other controversial proposals include a missile-firing testing system that would endanger the ground nesting of the endemic Nicobar megapode in the Tillanchong Sanctuary and a RADAR station in the only home of the Narcondam Hornbill on Narcondam Island.

The problem in this vision of development, a view of the islands as a military and economic colony is that it fails to consider the fragile ecology and the vulnerable indigenous communities. “The islands has always only existed on the margins of the consciousness of the nation. Did the earthquake and tsunami further ratify the fringeness of the fringe, allowing for experimentation, explosions and targeting in the interests of the Centre?” asks Sekhsaria.

The writing is elegant, the pen compassionate, the vision clear, even if the book is hampered by the fact that it is a collection of reports, hence lacking flow, and with a few overlaps across reports.

That apart, Islands of flux is an important book, providing a unique document from a region that rarely features in the mainstream media, and in dialogues in faraway Delhi. Even more lacking is an understanding of its unique wildlife, forests, people, culture and the intricate link between these, which the author writes of with finesse. This book is particularly relevant as the country sees mounting tensions from other such ‘colonies’ in the hinterland, where farmers, fisherfolk and tribal people are up in arms against the juggernaut of development: mines, ports, power plants, industries that erode ecology that sustains them, and a way of life.

The writer tackles this complex, nuanced subject with sensitivity and an insight backed with his years on the ground.

I hope that the book will bring the islands closer to the state that rules it but fails to serve it, and to tourists who visit it, unseeing and uncaring of their footprint. I know I need to visit again, to see the island with eyes anew.

The book is available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

The book is available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Published on October 03, 2017 04:38

September 30, 2017

In Deep Water - on the Hyd release of 'Islands in Flux'

In deep water by Sangeetha Devi Dundoo

September 16, 2017 16:48 IST

Updated: September 16, 2017 16:48 IST

http://www.thehindu.com/books/books-authors/in-his-new-book-pankaj-sekhsaria-continues-his-analysis-on-complex-issues-that-put-the-beautiful-andaman-and-nicobar-islands-in-a-state-of-flux/article19698573.ece

In his new book, Pankaj Sekhsaria continues his analysis on complex issues that put the beautiful Andaman and Nicobar islands in a state of flux

--

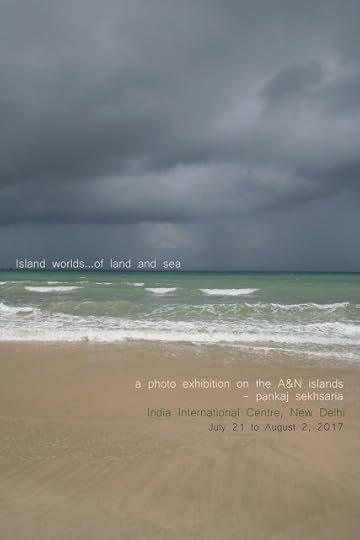

‘Islands in Flux – the Andaman and Nicobar Story’ (HarperCollins India; ₹399) is a collection of writings by researcher Pankaj Sekhsaria over two decades, many of them published in mainstream media including The Hindu. While a collection of fictional works might be of nostalgic value or help analyse the evolution of a writer’s style and thought processes over time, this compilation aims to educate and inform readers of the history, geology and ecology of the earthquake-prone islands.

Hyderabad-based Pankaj Sekhsaria, who unveiled his book in the city recently, first visited the islands in 1994-95 on a friend’s invitation. An avid photographer with an interest in wildlife, environment and conservation, he travelled extensively between the islands of the archipelago for two months. Since then, he has gone back several times and chronicled the changes and conflicts in the island.

When we begin to talk, he puts things in perspective on the need for this compilation: “As a researcher or an activist, you have a sense of the history of a place and its issues and you see things coming back in circles. There is enough information out there — be it on development, ecology or about the indigenous people. But issues crop up and you feel the need to respond and react, though it feels repetitive since you’ve already written about it. In a sense, it feels like being on treadmill — running in the same place,” he says.

A keen observer of events in the islands, he observes how those in authority, irrespective of the political party, announce development projects as though starting on a clean slate, but oblivious to the ramifications.

Seismic activity

In the islands, Sekhsaria explains, geological activity is a crucial factor. “The Andaman and Nicobar islands are among the most seismically active zones in the world, with earthquakes occurring even twice a month. The earthquake measuring 9.3 on the Richter scale that triggered the tsunami of 2004 happened off the Sumatra coast, which is 100km off the Nicobar, and caused huge damage. A decade later, new development projects haven’t taken into account the geological, socio cultural and ecological components of the islands. Indigenous people who’ve been there for 30000 to 40000 years are part of the unique ecology. A characteristic of the islands is the high endemism — plants, animals, birds and butterflies not found anywhere else,” he points out.

Having highlighted various issues pertaining to the islands through his ‘Faultline’ column in The Hindu, Sekhsaria hopes his writings will raise awareness. He feels the islands need plans that understand its seismic activity and the inherent risks, while also factoring in the presence of indigenous tribes and forest areas that need to be conserved. By not having a deeper understanding of the issues at hand, he feels projects might increase the “vulnerability of both the tribals and around 400,000 settlers from mainland who live modern lives like any of us.”

Living in denial

To cite an example, he talks about the union home minister’s (Rajnath Singh) visit to the islands this summer. “A delegation of farmers from Port Blair met him to request compensation for their lands that were submerged following the tsunami of 2004. On another day, there was a tourism delegation requesting relaxation of CRZ (Coastal Regulation Zone). The 2004 tsunami raised some parts of Andamans by 4ft while sinking parts of Nicobar by 15ft. If there are tourism-driven properties closer to the coast, aren’t they also vulnerable? We have to acknowledge the risks and think of a solution; we can’t live in denial.”

Over the years, Sekhsaria has interacted with people and organisations working on environmental conservation and education in the islands.

Writing or holding talks are his way of increasing the dialogue. “The least I can do is talk or write so that there’s a counter narrative,” he states.

Sekhsaria draws attention to how every now and then, political parties toy with renaming some of the islands or their landmarks. “The islands have a complex history — the first war of independence, kalapani and colonisation. Some may argue in favour of renaming the colonial-sounding names after Indian freedom fighters. But the islands have a history longer than that of colonisation; there are original names given by indigenous people,” he states.

As a parting thought, he states that even if some of the writings in this book have been more than a decade ago, it assumes more relevance today.

The author’s previous books on the islands:

The Last Wave – an island novel (HarperCollins India; 2014)

The Jarawa Tribal Reserve Dossier – Cultural and Biological Diversity in the Andaman Islands (UNESCO and Kalpavriksh; 2010)

The books are available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

September 16, 2017 16:48 IST

Updated: September 16, 2017 16:48 IST

http://www.thehindu.com/books/books-authors/in-his-new-book-pankaj-sekhsaria-continues-his-analysis-on-complex-issues-that-put-the-beautiful-andaman-and-nicobar-islands-in-a-state-of-flux/article19698573.ece

In his new book, Pankaj Sekhsaria continues his analysis on complex issues that put the beautiful Andaman and Nicobar islands in a state of flux

--

‘Islands in Flux – the Andaman and Nicobar Story’ (HarperCollins India; ₹399) is a collection of writings by researcher Pankaj Sekhsaria over two decades, many of them published in mainstream media including The Hindu. While a collection of fictional works might be of nostalgic value or help analyse the evolution of a writer’s style and thought processes over time, this compilation aims to educate and inform readers of the history, geology and ecology of the earthquake-prone islands.

Hyderabad-based Pankaj Sekhsaria, who unveiled his book in the city recently, first visited the islands in 1994-95 on a friend’s invitation. An avid photographer with an interest in wildlife, environment and conservation, he travelled extensively between the islands of the archipelago for two months. Since then, he has gone back several times and chronicled the changes and conflicts in the island.

When we begin to talk, he puts things in perspective on the need for this compilation: “As a researcher or an activist, you have a sense of the history of a place and its issues and you see things coming back in circles. There is enough information out there — be it on development, ecology or about the indigenous people. But issues crop up and you feel the need to respond and react, though it feels repetitive since you’ve already written about it. In a sense, it feels like being on treadmill — running in the same place,” he says.

A keen observer of events in the islands, he observes how those in authority, irrespective of the political party, announce development projects as though starting on a clean slate, but oblivious to the ramifications.

Seismic activity

In the islands, Sekhsaria explains, geological activity is a crucial factor. “The Andaman and Nicobar islands are among the most seismically active zones in the world, with earthquakes occurring even twice a month. The earthquake measuring 9.3 on the Richter scale that triggered the tsunami of 2004 happened off the Sumatra coast, which is 100km off the Nicobar, and caused huge damage. A decade later, new development projects haven’t taken into account the geological, socio cultural and ecological components of the islands. Indigenous people who’ve been there for 30000 to 40000 years are part of the unique ecology. A characteristic of the islands is the high endemism — plants, animals, birds and butterflies not found anywhere else,” he points out.

Having highlighted various issues pertaining to the islands through his ‘Faultline’ column in The Hindu, Sekhsaria hopes his writings will raise awareness. He feels the islands need plans that understand its seismic activity and the inherent risks, while also factoring in the presence of indigenous tribes and forest areas that need to be conserved. By not having a deeper understanding of the issues at hand, he feels projects might increase the “vulnerability of both the tribals and around 400,000 settlers from mainland who live modern lives like any of us.”

Living in denial

To cite an example, he talks about the union home minister’s (Rajnath Singh) visit to the islands this summer. “A delegation of farmers from Port Blair met him to request compensation for their lands that were submerged following the tsunami of 2004. On another day, there was a tourism delegation requesting relaxation of CRZ (Coastal Regulation Zone). The 2004 tsunami raised some parts of Andamans by 4ft while sinking parts of Nicobar by 15ft. If there are tourism-driven properties closer to the coast, aren’t they also vulnerable? We have to acknowledge the risks and think of a solution; we can’t live in denial.”

Over the years, Sekhsaria has interacted with people and organisations working on environmental conservation and education in the islands.

Writing or holding talks are his way of increasing the dialogue. “The least I can do is talk or write so that there’s a counter narrative,” he states.

Sekhsaria draws attention to how every now and then, political parties toy with renaming some of the islands or their landmarks. “The islands have a complex history — the first war of independence, kalapani and colonisation. Some may argue in favour of renaming the colonial-sounding names after Indian freedom fighters. But the islands have a history longer than that of colonisation; there are original names given by indigenous people,” he states.

As a parting thought, he states that even if some of the writings in this book have been more than a decade ago, it assumes more relevance today.

The author’s previous books on the islands:

The Last Wave – an island novel (HarperCollins India; 2014)

The Jarawa Tribal Reserve Dossier – Cultural and Biological Diversity in the Andaman Islands (UNESCO and Kalpavriksh; 2010)

The books are available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Published on September 30, 2017 07:11

September 16, 2017

Islands in Flux - Released in Hyderabad

The story of two Islandshttp://www.thehansindia.com/posts/index/Hyderabad-Tab/2017-09-16/The-story-of-two-Islands/326897 THE HANS INDIA | Sep 16,2017 , 12:05 AM IST

The book ‘Islands In Flux’, released recently in the city which explores the story of Andaman and Nicobar Islands

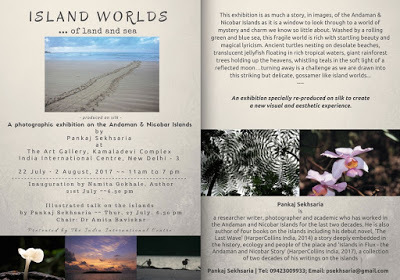

Aasheesh Pittie and Pankaj Sekhsaria. Photo: N Shiva Kumar Meru Ornithologist Aasheesh Pittie launched the book ‘Islands In Flux’ written by Pankaj Sekhsaria, researcher and author, recently at Goethe-Zentrum, Banjara Hills.

Aasheesh Pittie and Pankaj Sekhsaria. Photo: N Shiva Kumar Meru Ornithologist Aasheesh Pittie launched the book ‘Islands In Flux’ written by Pankaj Sekhsaria, researcher and author, recently at Goethe-Zentrum, Banjara Hills.

The book features the information, insight, and perspective related to the environment, wildlife conservation, development and the indigenous communities and contemporary issues in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

It provides an important account that is relevant both for the present and the future of these beautiful and fragile Island but also very volatile Island chain.

Pankaj Sekhsaria said, “It is not new for me to write about Islands and it this is my collection of writings about Andaman and Nicobar Islands. These islands are far away from India but they are part of it. The islands have various kind of animals, birds and more.”

Pankaj Sekhsaria said that everybody started talking about these Islands after the Tsunami in 2004. “Today our oceans are filling up with a lot of plastic. Many scientists are fearful that our oceans will have more plastic than fish in 2050,” added Pankaj.

He informed that no government has taken care of the tribal people of these Islands since independence. “No one is concerned about the tribal people, who have been living there for more than 40,000 years. In 1956, these Islands are declared for the tribal, but no one is taking care of them,” he adds.

Pankaj hopes that his book will create awareness in people about these Islands.

The book ‘Islands In Flux’, released recently in the city which explores the story of Andaman and Nicobar Islands

Aasheesh Pittie and Pankaj Sekhsaria. Photo: N Shiva Kumar Meru Ornithologist Aasheesh Pittie launched the book ‘Islands In Flux’ written by Pankaj Sekhsaria, researcher and author, recently at Goethe-Zentrum, Banjara Hills.

Aasheesh Pittie and Pankaj Sekhsaria. Photo: N Shiva Kumar Meru Ornithologist Aasheesh Pittie launched the book ‘Islands In Flux’ written by Pankaj Sekhsaria, researcher and author, recently at Goethe-Zentrum, Banjara Hills.The book features the information, insight, and perspective related to the environment, wildlife conservation, development and the indigenous communities and contemporary issues in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

It provides an important account that is relevant both for the present and the future of these beautiful and fragile Island but also very volatile Island chain.

Pankaj Sekhsaria said, “It is not new for me to write about Islands and it this is my collection of writings about Andaman and Nicobar Islands. These islands are far away from India but they are part of it. The islands have various kind of animals, birds and more.”

Pankaj Sekhsaria said that everybody started talking about these Islands after the Tsunami in 2004. “Today our oceans are filling up with a lot of plastic. Many scientists are fearful that our oceans will have more plastic than fish in 2050,” added Pankaj.

He informed that no government has taken care of the tribal people of these Islands since independence. “No one is concerned about the tribal people, who have been living there for more than 40,000 years. In 1956, these Islands are declared for the tribal, but no one is taking care of them,” he adds.

Pankaj hopes that his book will create awareness in people about these Islands.

Published on September 16, 2017 05:19

August 29, 2017

Islands in Flux - Presentation in Bangalore, Sept 8

Friends in Bangalore...

Copies of the book are available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Copies of the book are available in stores and via amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Published on August 29, 2017 05:41

Shaping Wilderness

Shaping wilderness Pankaj Sekhsaria and Naveen Thayyil

The Hindu, August 23, 2017The use of technology is challenging long-held ideas about conservation

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/shaping-wilderness/article19541365.ece

One of the most significant trends visible in wildlife conservation and management today is the increased use of ‘technology’. Camera traps, for instance, have provided new evidence of tiger presence in the Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary in Goa and of the Asiatic wildcat in Bandhavgarh, Madhya Pradesh; radio collars have helped solve the mystery of tiger deaths in Bandipur in Karnataka and Chandrapur district of Maharashtra; and satellite telemetry promises to provide new insights into the behaviour and movement patterns of the Great Indian Bustard in Gujarat, which includes its journeys across the border to Pakistan. New software and sophisticated surveillance technologies are being operationalised to keep an eye on developments across large landscapes and the use of contraceptives has been suggested to contain runaway populations of animals ranging from the monkey in large parts of India to the elephant in Africa.Within easy reachWe may not be able to escape such a technology-based framing, but is it possible that the current set of technologies, like those mentioned earlier, are profoundly different from those of the earlier era? And is the change that we are seeing, therefore, a more fundamental one?

What these innovations appear to do is increase our proximity to the subject of our interest and of our investigation. Surveillance technologies are bringing distant and topographically complex landscapes right into our homes and offices so that they can be observed and monitored without moving an inch. More individual wild animals are perhaps being caught and handled today than has ever happened earlier. And then there are various levels of physical intrusion that these sentient beings are subjected to — be it a microchip in the tail, a radio collar around its neck or a contraceptive injected into its body, not to mention the sedation that most of these individuals are forced into to enable such intrusions.

Technology has always allowed us deeper access into and control over our environment; in many ways it has been key in the human conquest over nature. And yet there are some things — a ferocious large cat or a free flying bird or a deep-sea mammal — that had still seemed out of reach. They were wild, defined as an animal ‘living or growing in the natural environment; not domesticated or cultivated’. They were wild and therefore inaccessible or inaccessible, therefore wild. Technology is closing that gap and it is the very idea of the ‘wild’ and ‘wilderness’ that comes into focus in important public initiatives such as conservation and protection of biodiversity. How wild or natural, for instance, is an animal that cannot perform its fundamental biological function of procreation because it has been sterilised by human intervention? Is a tiger that has been sedated multiple times and now carries a radio collar as ‘wild’ a tiger as one that has never been photographed, sedated or collared? How wild is a wilderness where everything has been mapped, where everything is known and where all movement is tracked in real time?

Aesthetic and ethical issuesThe matter here is both aesthetic and ethical. The basic pleasures of enjoying the wild are essentially technology mediated intrusions (think binoculars and cameras) into the private lives of animals that the human species does not allow in its own case. Aldo Leopold pointed out, for instance, to the role of the automobile, and the dense construction of roads to accommodate them, as central to the emergence of wilderness areas in 19th century United States. Does the radio collar go only a step further, or is there a fundamental shift here? One could argue that this collar is a signifier of further human dominance and authority over the wild animal if not complete control. A photograph of a collared tiger is unlikely to win an award in a wildlife photography context just as an encounter with a collared animal is unlikely to evoke the same experience of thrill because the element of surprise will have been removed. The issue is one that goes to the very heart of the notion of the ‘wild’ and of ‘wilderness’, marking as it does a paradigm shift in our relationship to and understanding of wildlife.

This is not an esoteric matter because it has a direct bearing on the agenda of conservation; it is the conservation of this ‘wild’ life that we are talking about after all. If we agree that technologies and technological interventions are bringing about fundamental changes in the identities and essence of wild subjects, it follows that current ideologies and methods of conservation will also have to change.

Are we willing to characterise wilderness areas as glorified theme parks? Are attempts at conservation then just routes to manage these slippery slopes? If this is not an appropriate aesthetic or ethical stance, then how do we think of the ubiquitous use of high technology to shape wilderness, and to intrude into ‘wild’ bodies, even as they are used in the name of protecting them?

Pankaj Sekhsaria and Naveen Thayyil are researchers at the DST-Centre for Policy Research, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT-Delhi. The views expressed are personal

The Hindu, August 23, 2017The use of technology is challenging long-held ideas about conservation

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/shaping-wilderness/article19541365.ece

One of the most significant trends visible in wildlife conservation and management today is the increased use of ‘technology’. Camera traps, for instance, have provided new evidence of tiger presence in the Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary in Goa and of the Asiatic wildcat in Bandhavgarh, Madhya Pradesh; radio collars have helped solve the mystery of tiger deaths in Bandipur in Karnataka and Chandrapur district of Maharashtra; and satellite telemetry promises to provide new insights into the behaviour and movement patterns of the Great Indian Bustard in Gujarat, which includes its journeys across the border to Pakistan. New software and sophisticated surveillance technologies are being operationalised to keep an eye on developments across large landscapes and the use of contraceptives has been suggested to contain runaway populations of animals ranging from the monkey in large parts of India to the elephant in Africa.Within easy reachWe may not be able to escape such a technology-based framing, but is it possible that the current set of technologies, like those mentioned earlier, are profoundly different from those of the earlier era? And is the change that we are seeing, therefore, a more fundamental one?

What these innovations appear to do is increase our proximity to the subject of our interest and of our investigation. Surveillance technologies are bringing distant and topographically complex landscapes right into our homes and offices so that they can be observed and monitored without moving an inch. More individual wild animals are perhaps being caught and handled today than has ever happened earlier. And then there are various levels of physical intrusion that these sentient beings are subjected to — be it a microchip in the tail, a radio collar around its neck or a contraceptive injected into its body, not to mention the sedation that most of these individuals are forced into to enable such intrusions.

Technology has always allowed us deeper access into and control over our environment; in many ways it has been key in the human conquest over nature. And yet there are some things — a ferocious large cat or a free flying bird or a deep-sea mammal — that had still seemed out of reach. They were wild, defined as an animal ‘living or growing in the natural environment; not domesticated or cultivated’. They were wild and therefore inaccessible or inaccessible, therefore wild. Technology is closing that gap and it is the very idea of the ‘wild’ and ‘wilderness’ that comes into focus in important public initiatives such as conservation and protection of biodiversity. How wild or natural, for instance, is an animal that cannot perform its fundamental biological function of procreation because it has been sterilised by human intervention? Is a tiger that has been sedated multiple times and now carries a radio collar as ‘wild’ a tiger as one that has never been photographed, sedated or collared? How wild is a wilderness where everything has been mapped, where everything is known and where all movement is tracked in real time?

Aesthetic and ethical issuesThe matter here is both aesthetic and ethical. The basic pleasures of enjoying the wild are essentially technology mediated intrusions (think binoculars and cameras) into the private lives of animals that the human species does not allow in its own case. Aldo Leopold pointed out, for instance, to the role of the automobile, and the dense construction of roads to accommodate them, as central to the emergence of wilderness areas in 19th century United States. Does the radio collar go only a step further, or is there a fundamental shift here? One could argue that this collar is a signifier of further human dominance and authority over the wild animal if not complete control. A photograph of a collared tiger is unlikely to win an award in a wildlife photography context just as an encounter with a collared animal is unlikely to evoke the same experience of thrill because the element of surprise will have been removed. The issue is one that goes to the very heart of the notion of the ‘wild’ and of ‘wilderness’, marking as it does a paradigm shift in our relationship to and understanding of wildlife.

This is not an esoteric matter because it has a direct bearing on the agenda of conservation; it is the conservation of this ‘wild’ life that we are talking about after all. If we agree that technologies and technological interventions are bringing about fundamental changes in the identities and essence of wild subjects, it follows that current ideologies and methods of conservation will also have to change.

Are we willing to characterise wilderness areas as glorified theme parks? Are attempts at conservation then just routes to manage these slippery slopes? If this is not an appropriate aesthetic or ethical stance, then how do we think of the ubiquitous use of high technology to shape wilderness, and to intrude into ‘wild’ bodies, even as they are used in the name of protecting them?

Pankaj Sekhsaria and Naveen Thayyil are researchers at the DST-Centre for Policy Research, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT-Delhi. The views expressed are personal

Published on August 29, 2017 05:38

August 22, 2017

The last straw

The last straw that triggered the battle against plastic

Pankaj Sekhsaria

Pankaj Sekhsaria

August 19, 2017 16:16 IST

Updated: August 19, 2017 18:26 IST

Could the ocean soon have more plastic than fish? | Photo Credit: AP more-in

Could the ocean soon have more plastic than fish? | Photo Credit: AP more-in

Faultline The humble straw might have just triggered the first fight in the battle against plastic http://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/the-last-straw/article19523610.ece

Think of anything you have had to drink today — a cola, fruit juice, cold coffee or lassi — and it is likely that it was served with a straw. The ubiquitous pink, white or blue plastic drinking straw has indeed become an unlikely marker of the modern culinary culture. Now think of the number of drinks served in a restaurant every day, the number of restaurants in a city, and the number of cities, big and small, in the world today, and one can only imagine the volume of plastic straws used on a daily basis. The plastic straw is also emblematic of the ‘use and throw’ culture.

And the ease with which we ask for a straw and then dispose it underlines both the mindlessness and the magnitude of our actions and their repercussions.

In Kerala 3.3 million plastic straws are used every day. It is 500 million daily in the U.S.. So billions of these straws, by implication, are thrown away around the planet. A significant chunk finds it way to the oceans and not surprisingly, plastic straws are consistently in the top 10 items collected every year during efforts to clean up the coastline.

While the single straw multiplied a billion times over might still only be a fraction of the total production and consumption of plastic in today’s world, it has become the inadvertent stimulus of a very significant anti-plastic campaign that has gained rapid traction all over the world.

The initiative against the plastic straw had started a little earlier, but it was about two years ago that the campaign took off.

International outrageThe specific catalyst was a 2015 video that showed a plastic straw jutting out from the nostril of an olive ridley turtle in Costa Rica.

The video that went viral on social media (more than 12 million people have seen it so far) has a marine biologist trying to pull out the straw with a plier, when blood starts to flow from animal’s nose. The rescuer continues to struggle for nearly five minutes before being able to pull out the nearly-four-inch-long straw, revealing how deep it had been embedded inside the animal’s body. The video sparked international outrage, giving wings to a movement to fight the menace of the plastic straw.

Much has been achieved since then. The Plastic Pollution Coalition (www.plasticpollutioncoalition.org) has estimated, for instance, that nearly 1,800 institutions worldwide, including prominent ones like Disney’s Animal Kingdom and the Smithsonian have banned plastic straws or give them only on request.

Volunteers who clean up beaches regularly are reporting fewer straws now than they did about a year ago and there is a small boost to those who make reusable straws from metal or bamboo.

The international movement has had its impact in India as well with reports of initiatives coming in from different parts of the country. Responding to the global online campaign #refusethestraw, earlier this year, restaurants and bars in Mumbai decided to stop giving their customers straws with their drinks or to offer them paper straws.

The restaurant industry in Kerala too made a similar decision to mark World Environment Day this June, and responding to complaints from citizens, the Kozhikode Municipal Corporation in the State too decided around the same time to ban plastic straws. It is one situation where the individual appears to be in a position to make a very significant difference.

Anthropocene markerOne of the markers of the Anthropocene, scientists say the planet has now entered, is plastic pollution (others include nuclear tests, concrete, and domesticated chicken).

Not only is plastic being produced and dumped in ever increasing quantities, it is unique in that it does not decompose or decay. A paper published in the journal Science Advances in July 2017 estimates that the world’s oceans now have nearly nine billion metric tonnes of plastic with an additional 5 to 13 million metric tonnes being added every year.

This being the case, it is expected that oceans will have more plastic than fish by the year 2050. It’s a problem of gigantic and timeless proportions and the humble plastic straw might just have triggered the first fight in a battle that will need to be sustained.

The author researches issues at the intersection of environment, science, society, and technology.

Pankaj Sekhsaria

Pankaj Sekhsaria August 19, 2017 16:16 IST

Updated: August 19, 2017 18:26 IST

Could the ocean soon have more plastic than fish? | Photo Credit: AP more-in

Could the ocean soon have more plastic than fish? | Photo Credit: AP more-in Faultline The humble straw might have just triggered the first fight in the battle against plastic http://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/the-last-straw/article19523610.ece

Think of anything you have had to drink today — a cola, fruit juice, cold coffee or lassi — and it is likely that it was served with a straw. The ubiquitous pink, white or blue plastic drinking straw has indeed become an unlikely marker of the modern culinary culture. Now think of the number of drinks served in a restaurant every day, the number of restaurants in a city, and the number of cities, big and small, in the world today, and one can only imagine the volume of plastic straws used on a daily basis. The plastic straw is also emblematic of the ‘use and throw’ culture.

And the ease with which we ask for a straw and then dispose it underlines both the mindlessness and the magnitude of our actions and their repercussions.

In Kerala 3.3 million plastic straws are used every day. It is 500 million daily in the U.S.. So billions of these straws, by implication, are thrown away around the planet. A significant chunk finds it way to the oceans and not surprisingly, plastic straws are consistently in the top 10 items collected every year during efforts to clean up the coastline.

While the single straw multiplied a billion times over might still only be a fraction of the total production and consumption of plastic in today’s world, it has become the inadvertent stimulus of a very significant anti-plastic campaign that has gained rapid traction all over the world.

The initiative against the plastic straw had started a little earlier, but it was about two years ago that the campaign took off.

International outrageThe specific catalyst was a 2015 video that showed a plastic straw jutting out from the nostril of an olive ridley turtle in Costa Rica.

The video that went viral on social media (more than 12 million people have seen it so far) has a marine biologist trying to pull out the straw with a plier, when blood starts to flow from animal’s nose. The rescuer continues to struggle for nearly five minutes before being able to pull out the nearly-four-inch-long straw, revealing how deep it had been embedded inside the animal’s body. The video sparked international outrage, giving wings to a movement to fight the menace of the plastic straw.

Much has been achieved since then. The Plastic Pollution Coalition (www.plasticpollutioncoalition.org) has estimated, for instance, that nearly 1,800 institutions worldwide, including prominent ones like Disney’s Animal Kingdom and the Smithsonian have banned plastic straws or give them only on request.

Volunteers who clean up beaches regularly are reporting fewer straws now than they did about a year ago and there is a small boost to those who make reusable straws from metal or bamboo.

The international movement has had its impact in India as well with reports of initiatives coming in from different parts of the country. Responding to the global online campaign #refusethestraw, earlier this year, restaurants and bars in Mumbai decided to stop giving their customers straws with their drinks or to offer them paper straws.

The restaurant industry in Kerala too made a similar decision to mark World Environment Day this June, and responding to complaints from citizens, the Kozhikode Municipal Corporation in the State too decided around the same time to ban plastic straws. It is one situation where the individual appears to be in a position to make a very significant difference.

Anthropocene markerOne of the markers of the Anthropocene, scientists say the planet has now entered, is plastic pollution (others include nuclear tests, concrete, and domesticated chicken).

Not only is plastic being produced and dumped in ever increasing quantities, it is unique in that it does not decompose or decay. A paper published in the journal Science Advances in July 2017 estimates that the world’s oceans now have nearly nine billion metric tonnes of plastic with an additional 5 to 13 million metric tonnes being added every year.

This being the case, it is expected that oceans will have more plastic than fish by the year 2050. It’s a problem of gigantic and timeless proportions and the humble plastic straw might just have triggered the first fight in a battle that will need to be sustained.

The author researches issues at the intersection of environment, science, society, and technology.

Published on August 22, 2017 03:31

August 17, 2017

An interview with Aniket Latpate

https://bookishaniket.wordpress.com/2017/08/17/author-interview-pankaj-sekhsaria/

Pankaj Sekhsaria has a long-standing association with the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (ANI) as a member of the environmental action group, Kalpavriksh. He is the author most recently of ‘Islands in Flux – the Andaman and Nicobar Story’ (Harper Collins India 2017), a collection of his journalism based on the islands over the last two decades. His debut novel ‘The Last Wave’ (HarperCollins India, 2014) was also set in the Andaman Islands and he is also co-editor of The Jarawas Reserve Dossier for UNESCO (2010).

He is also author of ‘The State of Wildlife in Northeast India 1996-2011: News and Information from the Protected Area Update’, published by Foundation for Ecological Security.

He recently finished his PhD thesis titled ‘Enculturing Innovation – Indian engagements with nanotechnology in the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS)’ from the Maastricht University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

He currently works as a Senior Project Scientist, DST-Centre for Policy Research, Dept of Humanities and Social Science at IIT- Delhi.

when did you first realized that you want to write? My interest in writing began, interestingly, because of writing letters. These were my early days of college and while I was not a loner, I did not have a very large circle of friends. Those were also the years I was learning about environmental issues and thinking about things that as a teenager are full of questions and have no straight forward answers. There were a couple of friends who lived in different places and we would regularly exchange hand written letters. Remember, this was the era of no email – even computers were hardly there. And I would write really long letters – running into many pages. And they would write back often saying they enjoyed reading what I wrote and the way I wrote. Those responses, I think, sowed the seeds for me and that is where I began thinking of writing more seriously. Being an author, however, was never on my list of things to become. The writing progressed then from letters to friends, to letters to newspapers, to articles and photo-features and eventually, now, to books.

2. Where did you get information for your books?

Both my recent books on the islands – ‘ The Last Wave’ , which is my debut novel, and ‘Islands in Flux’ which is a collection of journalism have come after nearly two decades of research, writing and photography in the islands. So, it is this body of experience, research, traveling and reading that I have drawn upon to put the two books together. In some senses, the books are a consolidation of nearly two decades of my work in the islands.

3. What do you do when you are not writing?

Research and writing is an integral part of what I do and I do end up writing quite a bit. There is a newsletter on wildlife that I edit for the environmental action group, called Kalpavriksh. I also write a monthly column on the environment for ‘The Hindu’ and besides that regularly put together articles and photo features for other publications. My research work is at the intersection of the environment and social sciences and there is a lot of writing to be done there as well. So I do end up writing a lot. To answer your question more specifically – I do read quite a bit, I like to travel too and I am also a keen photographer. My photography has in fact, been an integral part of my writing and research work.

4. How did the idea of ‘Islands in Flux’ come about? Was there a certain incident or experience that led to this narrative?

‘Islands in Flux’ is a book that brings together my journalistic and research based writing about the Andaman and Nicobar islands over the last two decades. The attempt is to bring together the wide range of experiences, issues and challenges that constitute the islands, the three main dimensions of which are the histories of the human communities here, the ecological diversity and fragility of this unique island chain and the constant geologic and tectonic activity that is very much part of life here. These are subjects I have been writing about since the mid 90s for a range of English publications in India and I realized that there is a considerably vast terrain that these articles have covered. In many contexts these writings continued to be relevant today, even as the issues they deal with are very interesting.

So, Islands in Flux, is not one narrative; the idea was precisely to show that there are multiple narratives and stories and all of them are important and relevant in different ways. And this becomes particularly important because of the specific vulnerabilities of the islands – one of the issues that was raised, for instance, during the Home Minister’s recent visit to the islands was related to compensation for land and other losses suffered by people here during the cataclysmic earthquake and tsunami of December 2004. A simultaneous demand was for relaxation of Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) norms because these are coming in the way of expanding tourism in the islands. I am not sure about others, but I see very clear contradictions here and the fact that policy planning continues to ignorant of these very specific contexts and vulnerabilities of the islands. A recent proposal for the development of the islands being pursued by the Niti Aayog has proposed, among others, plans for port construction, an integrated tourism complex, construction of a trans-shipment terminal and creation of a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in areas that are ecologically fragile and also legally protected in the name of the indigenous communities. The scale of what is being proposed in the islands today is unmatched, and its implications for the local people and the local ecology barely understood.

In recent years it has also been frustrating for me to see that many of these issues have been discussed in various fora including in my own writings in the past and yet none of these are seen reflected in new proposals, statements and policies being put forward by politicians, ministers, and the administration. The whole discussion has to be started from scratch – it’s like being on a treadmill for ever. And so, this was one of the most important reasons for me to put ‘Islands in Flux’ together – to kind of move on from that treadmill and force others to do the same as well.

5.What has been the biggest challenge while penning this book?

The format of the book – of putting together old writings to make them relevant for a contemporary context and reality – I think, is an interesting one. It is not a new format at all and has its limitations, but it also offers some striking possibilities. And the key question is whether I’ve managed to do it right. That would depend on how the book is received and what kinds of discussions and debates it generates. The initial responses from readers have been very encouraging and interesting. At least a couple of people have written in saying they realized on finishing the book how unaware they were of the multiple realities and challenges in the islands – that there is much more to the islands than the cellular jail, pretty beaches, and sparkling beaches that the tourism brochures show us. All of this is very much the reality in the islands, but there is much much more and conveying this is the challenge that ‘Islands in Flux’ seeks to take up.

6.Tell us about cover of your latest book and how it came from?

The book as you know is titled ‘Islands in Flux’ and the central idea for the cover was to focus on this idea of ‘change’ and ‘flux’. So what we ended up doing was to create a rather serene and calm scene with the boatman, the water and a tinge of green via the coconut. It in some senses, depicts the calm before a storm – the idea is that the calmness and the serenity is only momentary and change is just around the corner. And this has worked well, I think because of the contrast between what this scene depicts and the title where the letters that make up ‘flux’ themselves are struggling to find a balance.

7.Are you writing new book? If yes. What is it about?

There are two books that I am working on at the moment. One is an edited book that looks at wildlife in the state of Maharashtra and the other is in what is broadly called the Social Studies of Science and Technology. This is based on my recent PhD thesis that studied nano-science and technology laboratories in India to understand life inside the lab and to also understand what innovation means inside these labs and for scientists and technologists who work at the nano scale

8. What advise would you give to aspiring writers?

Writing is hard work and the more we write the better we get. Every single iteration of a piece of writing is better than its preceding version. So one should never think that what I have now cannot get better. It can and being at it all the time is very important.

The other thing I believe is useful if not important to be a good writer is to read – to read to learn and get new ideas but to read, also to see how other writes write, how they use the language, how they work with ideas…

9. How can readers discover more about you and your work?

Blog: http://pankaj-lastwave.blogspot.in/

Facebook Handle: https://www.facebook.com/pankaj.sekhsaria?ref=bookmarks

Twitter: @pankajsekh

Amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Thank you very much for taking the time out of your busy schedule to take part in this interview.

Pankaj Sekhsaria has a long-standing association with the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (ANI) as a member of the environmental action group, Kalpavriksh. He is the author most recently of ‘Islands in Flux – the Andaman and Nicobar Story’ (Harper Collins India 2017), a collection of his journalism based on the islands over the last two decades. His debut novel ‘The Last Wave’ (HarperCollins India, 2014) was also set in the Andaman Islands and he is also co-editor of The Jarawas Reserve Dossier for UNESCO (2010).

He is also author of ‘The State of Wildlife in Northeast India 1996-2011: News and Information from the Protected Area Update’, published by Foundation for Ecological Security.

He recently finished his PhD thesis titled ‘Enculturing Innovation – Indian engagements with nanotechnology in the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS)’ from the Maastricht University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

He currently works as a Senior Project Scientist, DST-Centre for Policy Research, Dept of Humanities and Social Science at IIT- Delhi.

when did you first realized that you want to write? My interest in writing began, interestingly, because of writing letters. These were my early days of college and while I was not a loner, I did not have a very large circle of friends. Those were also the years I was learning about environmental issues and thinking about things that as a teenager are full of questions and have no straight forward answers. There were a couple of friends who lived in different places and we would regularly exchange hand written letters. Remember, this was the era of no email – even computers were hardly there. And I would write really long letters – running into many pages. And they would write back often saying they enjoyed reading what I wrote and the way I wrote. Those responses, I think, sowed the seeds for me and that is where I began thinking of writing more seriously. Being an author, however, was never on my list of things to become. The writing progressed then from letters to friends, to letters to newspapers, to articles and photo-features and eventually, now, to books.

2. Where did you get information for your books?

Both my recent books on the islands – ‘ The Last Wave’ , which is my debut novel, and ‘Islands in Flux’ which is a collection of journalism have come after nearly two decades of research, writing and photography in the islands. So, it is this body of experience, research, traveling and reading that I have drawn upon to put the two books together. In some senses, the books are a consolidation of nearly two decades of my work in the islands.

3. What do you do when you are not writing?

Research and writing is an integral part of what I do and I do end up writing quite a bit. There is a newsletter on wildlife that I edit for the environmental action group, called Kalpavriksh. I also write a monthly column on the environment for ‘The Hindu’ and besides that regularly put together articles and photo features for other publications. My research work is at the intersection of the environment and social sciences and there is a lot of writing to be done there as well. So I do end up writing a lot. To answer your question more specifically – I do read quite a bit, I like to travel too and I am also a keen photographer. My photography has in fact, been an integral part of my writing and research work.

4. How did the idea of ‘Islands in Flux’ come about? Was there a certain incident or experience that led to this narrative?

‘Islands in Flux’ is a book that brings together my journalistic and research based writing about the Andaman and Nicobar islands over the last two decades. The attempt is to bring together the wide range of experiences, issues and challenges that constitute the islands, the three main dimensions of which are the histories of the human communities here, the ecological diversity and fragility of this unique island chain and the constant geologic and tectonic activity that is very much part of life here. These are subjects I have been writing about since the mid 90s for a range of English publications in India and I realized that there is a considerably vast terrain that these articles have covered. In many contexts these writings continued to be relevant today, even as the issues they deal with are very interesting.

So, Islands in Flux, is not one narrative; the idea was precisely to show that there are multiple narratives and stories and all of them are important and relevant in different ways. And this becomes particularly important because of the specific vulnerabilities of the islands – one of the issues that was raised, for instance, during the Home Minister’s recent visit to the islands was related to compensation for land and other losses suffered by people here during the cataclysmic earthquake and tsunami of December 2004. A simultaneous demand was for relaxation of Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) norms because these are coming in the way of expanding tourism in the islands. I am not sure about others, but I see very clear contradictions here and the fact that policy planning continues to ignorant of these very specific contexts and vulnerabilities of the islands. A recent proposal for the development of the islands being pursued by the Niti Aayog has proposed, among others, plans for port construction, an integrated tourism complex, construction of a trans-shipment terminal and creation of a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in areas that are ecologically fragile and also legally protected in the name of the indigenous communities. The scale of what is being proposed in the islands today is unmatched, and its implications for the local people and the local ecology barely understood.

In recent years it has also been frustrating for me to see that many of these issues have been discussed in various fora including in my own writings in the past and yet none of these are seen reflected in new proposals, statements and policies being put forward by politicians, ministers, and the administration. The whole discussion has to be started from scratch – it’s like being on a treadmill for ever. And so, this was one of the most important reasons for me to put ‘Islands in Flux’ together – to kind of move on from that treadmill and force others to do the same as well.

5.What has been the biggest challenge while penning this book?

The format of the book – of putting together old writings to make them relevant for a contemporary context and reality – I think, is an interesting one. It is not a new format at all and has its limitations, but it also offers some striking possibilities. And the key question is whether I’ve managed to do it right. That would depend on how the book is received and what kinds of discussions and debates it generates. The initial responses from readers have been very encouraging and interesting. At least a couple of people have written in saying they realized on finishing the book how unaware they were of the multiple realities and challenges in the islands – that there is much more to the islands than the cellular jail, pretty beaches, and sparkling beaches that the tourism brochures show us. All of this is very much the reality in the islands, but there is much much more and conveying this is the challenge that ‘Islands in Flux’ seeks to take up.

6.Tell us about cover of your latest book and how it came from?

The book as you know is titled ‘Islands in Flux’ and the central idea for the cover was to focus on this idea of ‘change’ and ‘flux’. So what we ended up doing was to create a rather serene and calm scene with the boatman, the water and a tinge of green via the coconut. It in some senses, depicts the calm before a storm – the idea is that the calmness and the serenity is only momentary and change is just around the corner. And this has worked well, I think because of the contrast between what this scene depicts and the title where the letters that make up ‘flux’ themselves are struggling to find a balance.

7.Are you writing new book? If yes. What is it about?

There are two books that I am working on at the moment. One is an edited book that looks at wildlife in the state of Maharashtra and the other is in what is broadly called the Social Studies of Science and Technology. This is based on my recent PhD thesis that studied nano-science and technology laboratories in India to understand life inside the lab and to also understand what innovation means inside these labs and for scientists and technologists who work at the nano scale

8. What advise would you give to aspiring writers?

Writing is hard work and the more we write the better we get. Every single iteration of a piece of writing is better than its preceding version. So one should never think that what I have now cannot get better. It can and being at it all the time is very important.

The other thing I believe is useful if not important to be a good writer is to read – to read to learn and get new ideas but to read, also to see how other writes write, how they use the language, how they work with ideas…

9. How can readers discover more about you and your work?

Blog: http://pankaj-lastwave.blogspot.in/

Facebook Handle: https://www.facebook.com/pankaj.sekhsaria?ref=bookmarks

Twitter: @pankajsekh

Amazon: http://tinyurl.com/y9pnz9ml

Thank you very much for taking the time out of your busy schedule to take part in this interview.

Published on August 17, 2017 23:40

August 12, 2017

The Andaman & Nicobar Story

The Andaman & Nicobar Storyhttps://www.natureinfocus.in/intervie... On this International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, Pankaj Sekhsaria discusses the ecology of the Andaman and Nicobar islands, and his new book, Islands in Fluxby Aadya Singh

Sekhsaria on a turtle survey in Wandoor, South Andaman Island. Photograph by Pankaj Sekhsaria Wednesday, 09 August, 2017

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are a microcosm of multitudes – not just because of their unique location, ecology and biodiversity, but also because of the variety of contexts within which they can be experienced and studied. (But information and studies on the islands are sparse and hard to find, so you might find this backgrounder useful for some cultural and historical context.)As a noted researcher, writer, activist, and photographer of the Andaman and Nicobar islands, Pankaj Sekhsaria embodies the diversity of the region in his own work. Sekhsaria has been chronicling the stories of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for over two decades now. With a sharp understanding of the islands’ issues, ranging from the cultural to the political to the economic, he has been instrumental in crafting both intellectual discourse and active intervention pertinent to this landscape. His recently released book, Islands in Flux – The Andaman and Nicobar Story, is a collection of his journalistic writings on the ANI over the past twenty years. Pankaj Dekhsaria is a noted researcher, writer, activist, and photographer. Photograph by Peeyush Sekhsaria Islands in Flux is a tapestry of events in the island story, organised by themes that transcend timelines and continue to be relevant today. With their unique location off the mainland and their interconnected threads of culture, community, ecology, and geology, the Andaman and Nicobar islands defy singular, linear narratives – they are truly islands in flux.We sat down to talk with him about his experiences from the union territory that most of us on the mainland know shamefully little about.What motivated you to put together a chronicle of the islands?What motivated me was the need for a consolidated account of the islands, that could comprehensively cover a gamut of issues. I realised that every few years, with every new person that comes into the administration, we had to start from scratch. Despite so much information out there in the public domain, it’s like these people were saying things in complete ignorance of certain issues, without any historical knowledge. So two years ago, I thought, why not make another consolidated account [his first compilation was titled Troubled Island and released in 2003] so that all the facts are in one place.

Pankaj Dekhsaria is a noted researcher, writer, activist, and photographer. Photograph by Peeyush Sekhsaria Islands in Flux is a tapestry of events in the island story, organised by themes that transcend timelines and continue to be relevant today. With their unique location off the mainland and their interconnected threads of culture, community, ecology, and geology, the Andaman and Nicobar islands defy singular, linear narratives – they are truly islands in flux.We sat down to talk with him about his experiences from the union territory that most of us on the mainland know shamefully little about.What motivated you to put together a chronicle of the islands?What motivated me was the need for a consolidated account of the islands, that could comprehensively cover a gamut of issues. I realised that every few years, with every new person that comes into the administration, we had to start from scratch. Despite so much information out there in the public domain, it’s like these people were saying things in complete ignorance of certain issues, without any historical knowledge. So two years ago, I thought, why not make another consolidated account [his first compilation was titled Troubled Island and released in 2003] so that all the facts are in one place.

Tracks of a nesting Giant Leatherback Turtle. Galathea, Great Nicobar, 2003. Photograph by Pankaj Sekhsaria When you compile such a large body of writing, certain themes begin to emerge, and that’s how this book is organised. It offers a snapshot of issues beyond the usual. The islands aren’t just about the tsunami, or about the Jarawa. Even older stories have a new salience in today’s context – those issues haven’t gone away. I have had readers telling me that they weren’t even aware about some of these issues that plague the islands.What first brought you to the islands, and what has the journey been like so far?I grew up in Pune, and was pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in engineering. By then, I was already interested in wildlife and writing. It was a ‘forced’ gap year that started it all. I had enrolled in a post-graduate degree in journalism, but two months into the course, I found out that I hadn’t cleared my Bachelor’s and couldn’t continue the journalism course, so I had a lot of time on my hands. At the time, a very dear friend of mine was based in Port Blair, working in the Navy. He invited me to come over, and that’s how I showed up at the islands for the first time, more than 20 years ago. I spent about two months there, travelled, met people, and got to know about the issues at the forefront. I came back to complete my graduation and then enrolled for a masters in communication at Jamia [Millia Islamia University] in Delhi. It was when I moved to Delhi that I got in touch with Kalpavriksh, which had been working in the islands for some time. And then I went back for a research project in 1998.

Tracks of a nesting Giant Leatherback Turtle. Galathea, Great Nicobar, 2003. Photograph by Pankaj Sekhsaria When you compile such a large body of writing, certain themes begin to emerge, and that’s how this book is organised. It offers a snapshot of issues beyond the usual. The islands aren’t just about the tsunami, or about the Jarawa. Even older stories have a new salience in today’s context – those issues haven’t gone away. I have had readers telling me that they weren’t even aware about some of these issues that plague the islands.What first brought you to the islands, and what has the journey been like so far?I grew up in Pune, and was pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in engineering. By then, I was already interested in wildlife and writing. It was a ‘forced’ gap year that started it all. I had enrolled in a post-graduate degree in journalism, but two months into the course, I found out that I hadn’t cleared my Bachelor’s and couldn’t continue the journalism course, so I had a lot of time on my hands. At the time, a very dear friend of mine was based in Port Blair, working in the Navy. He invited me to come over, and that’s how I showed up at the islands for the first time, more than 20 years ago. I spent about two months there, travelled, met people, and got to know about the issues at the forefront. I came back to complete my graduation and then enrolled for a masters in communication at Jamia [Millia Islamia University] in Delhi. It was when I moved to Delhi that I got in touch with Kalpavriksh, which had been working in the islands for some time. And then I went back for a research project in 1998.