Alida Winderhimer's Blog, page 3

September 25, 2014

Scrivener, You’re Losing Me!

Alida Winternheimer, author

Right now, one of the projects I’m juggling is the layout and design of The Murder in Skoghall. Last week, a reader of my Word Essential Writers newsletter (sign up to the right) asked me what I do about layout, and I helpfully reported that I do my interior design in Scrivener. It has a steep learning curve and some trial and error head aches, but so far I was happy with it.

Well, no more. Scrivener, you’re losing me.

Not for writing. I love Scrivener’s organizational capabilities. I will definitely continue to write in Scrivener. But… Skoghall has illustrations. I’m also inserting a vector graphic at the head and tail of the chapters. My design head aches have tripled with this book.

The Problems

In the images here, you can see the vector graphic I’m using above each chapter. I was able to insert the typewriter using Scrivener’s compile feature and setting the prefix above the folder name with the image tag. That was easy enough.

However, I want to use a small flourish at the end of each chapter and the end of the text. Scrivener has a front matter folder built in, but not a back matter folder. So, to compile the back matter into the book, requires it be part of the manuscript. This means the end flourish was placed after the About the Author page, not at the end of the story.

One of my illustrations has been inserted into the book successfully. See the image with the house. The next image didn’t go so smoothly. Why? Because Scrivener uses image tags, not the images themselves. This means the text shifts when the book is compiled to accommodate the image. That shift left weird white space around paragraphs. See the picture below with the image tag in the text? The tag is a single line. But the image fills about a third of the page. If the image falls on a page break, then you get stuck with a lot of white space either above or below the image.

I suppose one solution might be to use full pages for illustrations, inserting page breaks before and after them. But that’s not what I want.

And I have issues with Scrivener’s page numbering feature in compile. If I don’t want the number on the pages with chapter headings, I haven’t found a way to remove those.

The Solution

I’ve polled some indie authors and learned that Word is the way to go for layout. Shocked? I was. I used Word with its sections and style controls to format both of my academic theses; however, I never really considered it for working the layout of a novel. I thought it was either InDesign or Scrivener. I have done layout work in Scribus, a shareware alternative to InDesign. Scribus was great for doing chapbooks, which, for fiction, can run about 50 pages. When I considered switching from Scrivener to Scribus this past week, I thought “Hell no!”

See, when months pass between projects, I slide back down the learning curve. I’ve logged plenty of hours in Scrivener the past couple of weeks setting up this manuscript. And if Skoghall didn’t have illustrations or graphics, it would be done already. When I considered the learning curve I’d face switching to Scribus, it made me want to stay with Scrivener.

One of the indies I polled is also a professional designer. When I heard that she does layout in Word, and she has and knows how to use InDesign, I was floored. Then a bunch of other authors weighed in. Guess what? Word was the big winner. Nobody likes Scrivener for layout. Well, Donna, I’m sorry I steered you wrong! I was happy with the layout of my last book. No real complaints, other than the rather steep learning curve. But now—thanks to my frustrations and asking others what they do—I have seen the light.

I hate to have lost all those hours to working the layout in Scrivener, but at the end of the workweek, I need a layout that I’ll be proud of—even if it means taking on another learning curve with another software.

Word, here I come!

The post Scrivener, You’re Losing Me! appeared first on wordessential blog.

September 22, 2014

The Rocking Self-Publishing Webinar: Editing

Alida Winternheimer, author

Want to learn about editing? Want to know what I’m like to work with? Check out the webinar I did with Simon Whistler of Rocking Self-Publishing.

The post The Rocking Self-Publishing Webinar: Editing appeared first on wordessential blog.

August 29, 2014

Imagery in Your Writing

Alida Winternheimer, author

“A picture is worth a thousand words” is one of those old adages that holds true. It might seem skewed in favor of painters and photographers, but before you declare me a traitor, hear why it’s true for your writing as well. Fiction and nonfiction.

Think of your favorite book.

Now think of the most beautiful, well-crafted sentence in that book.

Got it?

…

No? How come?

Because by and large, even the most lyrical of sentences won’t be remembered. An attentive reader might pause and reread the line to savor it (and bless him for doing so), but the odds of it sticking in memory are slim.

Sure, there are a few exceptions. The most iconic sentence in American literature is…go on, tell me—from memory—and I’ll share it with Word Essential Writers next week.

My vote for the most iconic sentence in American literature is “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” That’s the closing line of The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, of course. But how many sentences of cultural magnitude can you name?

Let’s go back to your favorite book.

Think of the most powerful image within that story.

Got it?

Of course you do. Instantaneously.

The Poisonwood Bible

One of my favorites is The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver. I’m sure the text is full of beautiful sentences, but I can’t recite a single one. Ask me about a favorite image, however: At the beginning, the family is packing to move to the Congo for a year-long mission. They are only allowed one suitcase per person. So, the mother and daughters wear all the clothing they can layer on their bodies. They even fashion belts out of ropes and hang things, like fry pans and utensils, within the layers of their skirts. The image of these girls struggling down an airplane aisle, sweating under all their clothes, their skirts clanging with cookware, is indelible.

As a writer, the greatest gift you can give your reader is also the thing that will make your work memorable: a remarkable image. So, mind the old adage “A picture is worth a thousand words,” and you’ll craft scenes your readers will remember for years after they close the cover on your book.

What about nonfiction?

Everything I said about imagery above applies to nonfiction as well. Think of the latest nonfiction book you read. What do you remember about it? I’ll bet the parts of the book that got you fired up and stuck with you are the parts that evoked a mental image. The image might be part of an anecdote or case study. It almost certainly involves a human being and either triumph or defeat.

Empathy is one of the most powerful tools in your writer’s toolbox. Make your reader feel for that character or case study. Help your reader picture herself that character’s shoes. And then several things are more likely to happen in the reader’s mind:

• your how-to becomes possible,

• your reader becomes inspired,

• your trust quotient rises,

• your book becomes memorable.

A memorable book is a book that gets recommended, functions well in a product funnel, and adds authority to your name.

The post Imagery in Your Writing appeared first on wordessential blog.

July 31, 2014

Editing for Indies Interview Out Today!

Alida Winternheimer, author

The Editing for Indies Interview is out today!

Simon Whistler of the Rocking Self-Publishing Podcast recently interviewed me about editing for indies.

I’ve been working with Simon on his forthcoming Audiobooks for Indies. Working with him is as much of a pleasure as you’d imagine. It was especially fun to chat about editing for his indie audience. We cover lots of great topics:

3 levels of editing

hiring your editor

working with your editor

cost considerations

whether your editor should also be a writer

style sheets for nonfiction

You can find the podcast on the Rocking Self-Publishing Podcast website and iTunes.

And as if that’s not enough, Simon is hosting the first Rocking Self-Publishing webinar on August 9th.

I’ll be there to answer your editing questions–all for free!

You can find the Editing for Indies webinar sign-up page at rockingselfpublishing.com/joinwebinar.

When you sign up, you’ll get a free download of my Editing for Indies Guide! (That’s 9 pages of tips to save you time & money.)

The post Editing for Indies Interview Out Today! appeared first on wordessential blog.

When to Slow Down

Alida Winternheimer, author

There is a time and place for summary in every story, but it’s not when you’re writing an important or dramatic scene. The more important the scene, the more you need to slow down.

Summary is useful when you need to move along and a wide brush stroke won’t detract from the story.

Any important scene–one with dramatic tension, that develops a character, or advances the plot–is where you need to slow down your writing.

There’s an old adage: the faster the action, the slower the writing. If things are happening fast, or simultaneously, it’s going to take more ink to describe this to the reader in a way that presses emotional buttons.

Turtle is a proponent of slow writing.

You don’t want your pivotal moments to pass by in a blur. You want the reader to absorb every gritty detail. You want the impact on your character to resonate with your reader. And you want all that fast-paced action to be clear on the page.

Here’s an example from my own work. I was busy revising The Murder in Skoghall this past week–rewriting the climax, in fact–and this is what I found:

The leaves and debris on the trail were soggy and anywhere not covered by litter was already turned to mud. Mud that slid in through her Keens and oozed between her toes, making a slippery mess of the footbed. Lightning ripped across the sky. Jess felt somewhat protected by the tree cover, but still jumped at each boom of thunder.

Notice that paragraph is comprised of summary. I’m telling the reader what the trail was like. The verb was/were is used, and I actually say “Jess felt.” Yikes. Here’s the revised version:

Jess picked her way over fallen logs and branches. She put her foot down on what she had glimpsed as a bed of leaf litter, like so much of the trail before. She scanned out ahead in the narrow ring of lantern light, seeking the next place to land her foot. The cushion of debris, slick with rainwater, acted like an unmoored raft, sliding easily away when Jess shifted her weight onto it. She flung her arms out for balance as her feet lost their purchase, and the lantern knocked against a slender tree trunk beside the path. It went out. Jess swore as her ass landed where her foot should have been.

Notice in this revised paragraph that I avoid was/were. I put us firmly in Jess’s point of view, and the result is more tactile, more tangible. I later mention the mud coming in through her shoes and squishing between her toes, but cut it from this moment.

The second paragraph is a little longer, sure, but the payoff is great. In the first paragraph, there is the sense of things going on around Jess, or happening to her. In the second paragraph, we can feel what it’s like to pick our way along a treacherous path, performing a balancing act while trying to make it safely to the other side. As a result, we’re more likely to care when Jess falls on her ass.

And that is what slowing down is all about: being present in each and every moment.

The post When to Slow Down appeared first on wordessential blog.

June 17, 2014

To Be, Or Not To Be? In Your Writing, Not To Be!

Alida Winternheimer, author

As a native speaker of any language, you get to take certain things for granted, like conjugating irregular verbs. I’m not sure I was really aware of irregular verbs, never mind conjugating them, until I took French. Then, because I took English for granted, I thought those French were pretty much nuts, assigning a gender to inanimate objects and all those irregular verbs! I remember the day I learned etre, the French verb “to be.”

A lightbulb went off as I sat conjugating it: je suis, I am; tu es, you are; il/elle est, he/she is; and so on. I had never connected those little verbs, am, are, is, was, and were with a parent verb before. I had taken them for granted…until French class. To be is an awfully handy little verb. Imagine all the ideas we are able to express thanks to to be.

Those little verbs refer to a state of being and provide the subject with a sense of place in time. “I was great.” “I am great.” “I will be great.” Neat little verb, isn’t it? Really. To be is a neat verb when you are referring to a state of being.

However, (you sensed a “but” coming, didn’t you?) in your writing, you want to avoid using to be when you are referring to an action. You know, those times you have to attach a gerund to it (-ing). “He was running fast.” “He was breathing hard.” “She was scanning the crowd for the man she was to meet.”

Of course, there are times when there’s no better way to say something than with a to be + gerund construction, but in general, avoid doing so. Why?

Twitcher is eating a chip.

Because the to be + gerund construction is not immediate. It lacks urgency. It sounds passive, not active. Look at this example.

Sarah was sitting on a park bench, picking at her ragged cuticles. The sun was shining across her head, falling over her shoulders, and throwing her long shadow into the grass. She was enjoying the warmth on her back, getting lost in her own thoughts, when she heard someone walking on the path behind her, approaching, then stopping…standing…right behind her. Shivers went running up and down her spine.

You might think I’m exaggerating, but you might be surprised how often I see to be + gerund constructions in my clients’ writing. Check out the rewrite.

Sarah picked at her ragged cuticles, lost in thought, oblivious to the park spread out before her. The sun warmed her back, the top of her head, and threw her long shadow into the grass at her feet. Someone with a heavy gate approached on the path behind her bench. Unlike all the other passersby, this person slowed, then stopped right behind her, blocking the sun. Sarah lifted her head as a chill ran up and down her spine.

When you avoid using to be, your writing becomes present, imminent, and in prose, that means there’s more tension. Tension is a good thing. Tension is what makes your reader sit up and think, “Yeah? Yeah? What’s going to happen next?”

I think of to be writing as early draft writing. That’s when you are telling yourself the story. See that? You are telling yourself the story. In revision, look for those constructions and cut as many as you can. Ruthlessly. In your prose, you don’t want to give the reader the sense that things are happening around your character. You want the character and the reader to be in the action, a part of it, a source of it!

Share your thoughts in the comments below, and let me know if this was helpful to you.

The post To Be, Or Not To Be? In Your Writing, Not To Be! appeared first on wordessential blog.

June 11, 2014

Revision Time

Alida Winternheimer, author

It’s revision time again. There’s first draft time, then there’s revision time. Revision time is harder. When I’m writing a first draft there’s always the possibility of getting into flow. You know, that magical state where the words stream forth and everything makes sense. The characters speak, the plot advances, the tension is high, and you just know it’s awesome! The day I write “the end” at the bottom of the page, I do a little happy dance. It’s that good.

But then it’s time for phase two. No matter how good writing felt, how often I was in flow, there will be things to fix. Some of those things will be major. Most of them will be small–word choice, punctuation, clarity issues. This is the stuff I don’t like to fix because it necessitates hours at the keyboard, searching out the right sentence, tweaking it, and saving it. It’s tedious for sure. I’d rather fix the big things, because then I get to dip back into the writing process, get into flow if I’m lucky, and at the end of the day know that I accomplished something real. Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for ideal word choice and properly used commas, but entering those changes in a manuscript is like balancing your checkbook–yawn.

Sometimes, however, I get to something major, like the climax….

boring!

That manuscript, the one I’ve lavished with attention for months, the one that thrilled me, the one with flow…well…the climax is lame. I don’t mean bad. I just mean lame. When you have to ask, “where’s the dramatic tension?” there’s a problem. When you find yourself wondering why the scene ended here and not there, there’s a problem.

Sometimes we don’t know what we’ve accomplished until someone points it out to us. So much of subtext occurs on a subconscious level. When that happens, I feel brilliant. But sometimes we don’t know where we’ve failed until someone points it out to us. And if your book is already on the market…oops.

That’s why it’s critical to rest a manuscript. If you rest it long enough and come at it with (relatively) objective eyes, you’ll see the failures yourself. Let the glow of finishing that first draft wear away before you read it. It’s also useful to log several years reading and critiquing other writers manuscripts. We can easily see flaws in other people’s work that hide from us in our own work. It’s not because we’re better writers, it’s because we’re too close to the material. Objective distance is critical to gauging your own abilities. Even experienced writers need peers and editors to read their work. And always, always give it time.

Just as I was beginning the revision of The Murder in Skoghall, I was called away by a teaching job that I couldn’t turn down. It forced me to rest the manuscript for six more weeks. I’m sure I would have realized the climax wasn’t cutting it before going to print…right? I don’t know for sure, because the way it happened I did have those extra six weeks.

Now I’m ready to sit at the keyboard and type in the minutiae of editorial changes–this word, that comma, yawn. But I’m looking forward to getting to the end of the book and rewriting the climax. Then I’ll take a break and read it again.

Re-Vision isn’t just about seeing something again; it’s about seeing something again as for the first time.

The post Revision Time appeared first on wordessential blog.

March 30, 2014

Webcast Plot Storyboarding

Alida Winternheimer, author

Tonight the Word Essential Webcast Plot Storyboarding has gone live. It’s the first in the Plot Series and is all about Storyboarding.

The webcast is a way to share more information with you and hopefully answer your writing questions. Please let me know what you like and even what you don’t. Use the comments form or the contact form to suggest topics for future webcasts.

I’ll be organizing things into series, so once there are more to pick from, you’ll be able to find things by keywords, like plot, character, or setting.

I hope you like it!

Webcast Plot Storyboarding

The post Webcast Plot Storyboarding appeared first on wordessential blog.

February 22, 2014

When Stories Die

Alida Winternheimer, author

A writer just said to me that she gets halfway through a story and it dies. She loses interest and doesn’t finish it. I’ve heard lots of people mention that it’s easy to start and hard to finish, so just what is happening when stories die? And how can you get beyond that point and actually finish?

Let’s begin with a simple premise: a story is bad things happening to interesting people.

Here’s another simple premise: a story is made up of three things—character, plot, and setting.

When a story derails midway, the plot, the character, or both have gone wrong. Let’s use an example to work through this common writing problem.

I’ll give you a tool to make sure your stories don’t die.

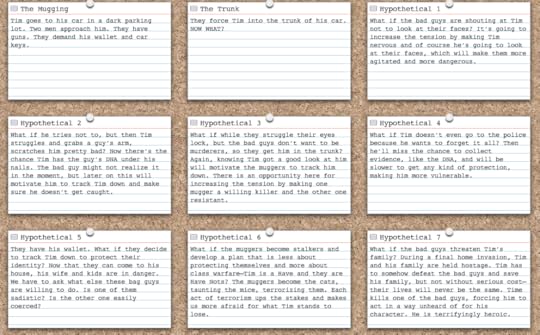

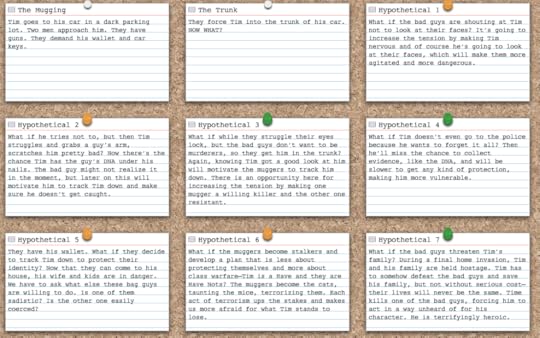

Suppose Tim is mugged in a parking lot, but instead of taking his cash and running, the bad guys make him climb into his trunk and lock him in.

That’s a good scenario. I don’t know anything about Tim at this point, but I’m worried for him because he’s put in harm’s way and there are clear bad guys in the scenario. I could write a story about this. Everyone would be interested to see how it ends.

Now, suppose I like Tim. He’s a good character and this is the middle of the book, so both I and the readers know Tim has to get out of the trunk alive. I want Tim to understand that life is precious and could be taken away any time, so he should be a better husband and father.

Did you just yawn? Why?

Appreciating life is a great theme. It’s universal. We should all aspire to it, right? Sure, but the story just stalled. Did you hear it sputter and halt? Why?

Well, Tim is an average guy who should be a better person. That’s how the character killed the story—Tim is just an average guy with a universal goal.

And we know he’s going to be fine. And that’s how the plot killed the story—if we know he’ll be fine, there’s nothing at stake.

So how do we get out of this fix? The same way we got into it: imagine new things until we get excited. It was exciting to imagine the bad guys forcing Tim into the trunk. We could feel Tim’s heart pounding against his ribs. He’s wishing he’d bought the hatchback instead of the sedan right now, and so are we.

Imagine that the bad guys run away and within a half hour, someone hears him yelling and he’s rescued. That would make a great anecdote to tell his wife when he gets home. In real life, that would be harrowing. But why would that be harrowing in real life and not in a story?

In real life, we play The Hypothetical Game. Tim tells his wife he was mugged. She says “Oh my God! Were you hurt? What happened?” He tells her. Then they spend the rest of the night giving themselves the chills by talking about scenarios that could have happened. “They could have killed you!” “They could have stolen the car with you in it!” “They could have shot you before making you get in the car!” (Those Hypotheticals are plot.) “I could have fought them.” “I could have gotten a better look at their faces.” “I could have scratched one to get DNA under my nails.” (Those Hypotheticals are character.)

That is how we make real life scarier than it actually is. If Tim said, “I was mugged and locked in the trunk, then released and now I’m just fine.” That would all be true. His wife could say, “How nice dear. At least your day wasn’t boring.” Also true. But it makes for a poor story.

Our stories die when we think we’ve run out of Hypotheticals.

We get stuck thinking that if we need Tim to be fine, then there’s not that much we can do with this scenario. And if that’s the case, the story is dead. Might as well move on to the next great story idea.

Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Lots can happen between the mugging and Tim getting on with his life. We’re going to play The Hypothetical Game.

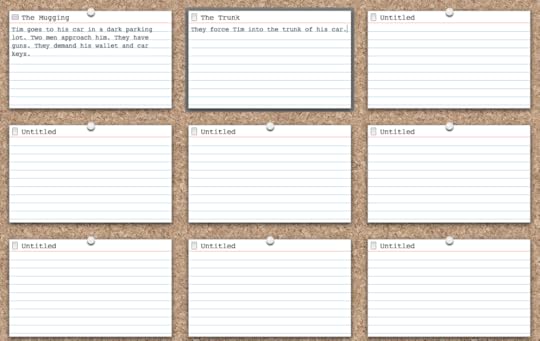

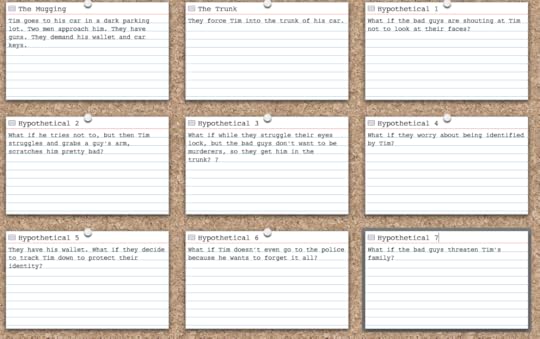

Do you have a storyline that is stalled? Then get out your index cards (or use the corkboard feature in Scrivener.)

*You can click on the pictures to enlarge them.

The Hypothetical Game, step 1

Write out all of your Hypotheticals on index cards and move them around, re-order, mix and match. What if the bad guys are shouting at Tim not to look at their faces? What if he tries not to, but then Tim struggles and grabs a guy’s arm, scratching him pretty bad? What if while they struggle their eyes lock, but what if the bad guys don’t want to be murderers, so they get him in the trunk? What if they worry about being identified by Tim? They have his wallet. What if they decide to track Tim down to protect their identity? What if Tim doesn’t even go to the police because he wants to forget it all?

Now something more interesting is shaping up. A cat and mouse game is developing between the muggers-turned-stalkers and Tim. Now we have something more at stake: the mugging isn’t over, it’s continuing as the bad guys decide to track Tim down and take care of him. They have his address, so now his wife and kids are in danger. Tim didn’t stand up to them in the parking lot, but he’s going to have to sooner or later to save his family.

Each of these Hypotheticals advances the action of the story, increases the risk to Tim and his family, and thereby increases the stakes.

Every time the stakes go up, we save the plot.

The Hypothetical Game, step 2

What about the character?

Average-guy-Tim is now forced to be exceptional. He’s going to have to call on or develop some survival skills and fast! And if our original thought was that Tim should appreciate life and be a better person, now that he’s in a position to protect his family from the bad guys, that message is coming home in a dramatic way.

Every time we let Tim be extraordinary, we save the character.

Go back to those cards with the Hypotheticals written on them. Answer the questions. Also, as you go through, toss out cards that are redundant and add new Hypotheticals that further up the stakes. As you address each Hypothetical, your ideas will continue to develop. You will find new avenues to explore. For instance, on card #7, Tim has to kill one of the bad guys to save his family. This is an act completely out of character that will profoundly impact his psyche, traumatize his family, and change all of their lives. While he is acting in self-defense and is a hero, he is also terrifying. A new set of Hypotheticals will have to be developed in order discover the best situation (action/reaction) for Tim to fulfill this climax of killing a bad guy and saving his family.

The Hypothetical Game, step 3

There’s one more step to The Hypothetical Game. Because stories die from both plot and character issues, go through the cards and color code them. Orange for plot. Green for character.

Of course, some Hypotheticals serve both plot and character, but you want to make sure that as you write forward you are developing both plot and character. The action rises and the character develops. If your cards are mostly orange or mostly green, even them out. Ask yourself how this action affects the character involved, or what kind of action this character development would enable.

The Hypothetical Game, step 4

Now that you’ve got your Hypotheticals written out, you can finish that book. Each step card marks a point in the action and/or character development that will keep you interested in your story now, and engage your readers later.

One of the reasons stories die midway, is because we start thinking about them like real life. But people don’t read stories to engage with real life, people read to escape real life.

Grab your index cards. Be extraordinary!

The post When Stories Die appeared first on wordessential blog.

January 6, 2014

Goodreads Winners!

Alida Winternheimer, author

Goodreads has chosen the winners of theA Stone’s Throw giveaway!

Congratulations to: Carol in Pennsylvania, Shelby in Iowa, Debbie in Maryland, Annie in Alaska, Kimberly in New York, and Amanda in North Carolina!

All six winners will receive a signed copy of A Stone’s Throw and an invitation to a web chat with me and each other, like our own virtual book club!

I’m looking forward to meeting you all and hope you enjoy the book,

**Details about the web chat will be included with the book.

The post Goodreads Winners! appeared first on wordessential blog.