Callum McLaughlin's Blog, page 10

March 11, 2021

Nicholle Ramsey & Alok Vaid-Menon | Mini Reviews

Calling in Black by Nicholle Ramsey

Published by Talking Drum, LLC

Rating:

In her debut collection of poetry, Ramsey blends personal reflection with incisive social commentary. There is a pleasant rhythm and flow to her style, reflective of her experience as a spoken word performer, and though the language and imagery are largely straight-forward, her unique poetic voice still shines through.

In her debut collection of poetry, Ramsey blends personal reflection with incisive social commentary. There is a pleasant rhythm and flow to her style, reflective of her experience as a spoken word performer, and though the language and imagery are largely straight-forward, her unique poetic voice still shines through.

Thematically the collection is certainly at its strongest when Ramsey lays bare the realities of life as a Black woman in a landscape that is inherently racist, capturing the dual persistence of oppression and resistance: “… the phoenix gains strength from / ashes / and we have been burned / for generations”. With that said, I love the way she contrasts the disdain society shows for Black bodies with the love she has come to cherish for her own Black body, some of the pieces as hopeful and celebratory as others are angry and weary.

And while she calls on history, making direct references to powerful names from the Civil Rights movement, she is also not afraid to place her work firmly in the here and now, with namechecks for the likes of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd hitting like a punch to the gut:

“history repeating, strange fruit / skipping on the record player / sandra bland knew the melody / but breonna taylor was caught off guard by the beat / we may pull up the statues, / but miss the roots / it grows, / grows like roses that bloom / in chests of young black boys / and thorns that choked george floyd / as he cried for his mother”

Rousing and impassioned, Ramsey is a poet whose future work I’m excited to follow.

Thank you to the publisher for a free advanced copy in exchange for an honest review.

Beyond the Gender Binary by Alok Vaid-Menon

Published by Penguin, 2020

Rating:

Non-binary writer and artist Alok Vaid-Menon presents readers with an eloquent, intersectional, warm, and honest rumination on their experience with gender identity.

Non-binary writer and artist Alok Vaid-Menon presents readers with an eloquent, intersectional, warm, and honest rumination on their experience with gender identity.

There’s a particular focus on the role that language plays in shaping opinion, perpetuating bias, and driving division, as the author discusses why a strict binary system of categorization limits everyone, not just those who opt not to live by it. They also go out of their way to debunk common misconceptions about belief in a gender spectrum, explaining that the recognition of identities beyond the “norm” isn’t an attempt to erase the concept of men and women; simply to allow everyone and anyone to feel at home in their own skin, and comfortable with the language they use to describe themselves.

Being so brief, and offering just one person’s perspective on such a complex, nuanced topic, this was never going to be an entirely comprehensive exploration of gender identity, but it serves as a fantastic and highly accessible entry point.

March 3, 2021

Summerwater by Sarah Moss | Book Review

Summerwater by Sarah Moss

Published by Picador, 2020

Rating:

Set across one relentlessly rainy day on a remote Scottish holiday park, Summerwater captures a microcosm of contemporary British society, in all its post-Brexit tension. Each of the twelve chapters follows the perspective of a different resident of the park, giving us a snapshot into their life; the thoughts and worries that occupy their mind.

Set across one relentlessly rainy day on a remote Scottish holiday park, Summerwater captures a microcosm of contemporary British society, in all its post-Brexit tension. Each of the twelve chapters follows the perspective of a different resident of the park, giving us a snapshot into their life; the thoughts and worries that occupy their mind.

With a deft hand, Moss highlights the multitudes and contradictions within us all, showing time and again that the same person can be capable of both great tenderness and great cruelty. With all of the residents wrapped up in their own domestic dramas, and feeling alone in one way or another, it’s their ingrained prejudice towards perceived outsiders that unites them (namely, an Eastern European family whose loud music is causing resentment throughout the park). With each chapter offering a character-focussed slice-of-life vignette rather than anything particularly plot heavy, it’s only at the very end the various threads are brought together, with Moss commenting on the bittersweet irony that it often takes tragedy to overshadow difference and unite people in their shared humanity. It’s also no coincidence that, despite being the linchpin of the novel, the “outsiders” themselves are never given a voice, being seen only through the eyes of their white, disproving British audience.

Moss writes with such understated skill. There’s an ease to the whole thing; beautiful without ever feeling overdone, as she weaves seamlessly between pathos and humour. It’s when she turns her attention to the surrounding natural world that her prose really shines, however.

We know from the blurb that the book will culminate in some kind of tragedy. Entering the book with this knowledge actually heightened the reading experience for me, emphasising the absolute control Moss has over the narrative. Suddenly, even the most mundane situations are infused with an undercurrent of threat, as people make seemingly throwaway decisions that we now see potential danger in, leaving us to constantly wonder when and how disaster will strike, and all too aware of how close we are to ruin at any given moment in our own lives. The eventual climax, though arguably a little too brief, tells us just enough to hit home the true enormity of what has unfolded. Again, Moss opts for a subtlety that could frustrate some, but such is the skill of her delivery that she more than gets away with it.

Though a couple of the points-of-view were decidedly less compelling than the others, and failed to add much thematically that hadn’t already been established elsewhere, Moss writes so well that I was never deterred. If the sucker-punch that is Ghost Wall remains my firm favourite of her novels, the strength of The Tidal Zone, and now Summerwater, confirm that Moss is an author I’m excited to continue following.

February 28, 2021

February Wrap Up

Here are links to the books I read & reviewed throughout February, followed by a quick look at the embroidery projects I completed.

Books read: 8

Yearly total: 16

1. The Truth of You by Iain S. Thomas

| Review

| Review

2. The Monsters of Rookhaven by Pádraig Kenny

| Review

| Review

3. On Connection by Kae Tempest

| Review

| Review

4. Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson

| Review

| Review

5. The Quiet Music of Gently Falling Snow by Jackie Morris

| Review

| Review

6. A Map of Rain Days by Jennifer Hosein

| Review

| Review

7. Wain by Rachel Plummer

| Review

| Review

8. A Luminous Republic by Andrés Barba, translated by Lisa Dillman

| Review

| Review

Favourite of the month: Open Water

As with last month, I enjoyed trying out a variety of embroidery styles, which resulted in the following 4 pieces.

What was your favourite read in February?

February 26, 2021

A Luminous Republic by Andrés Barba | Book Review

A Luminous Republic by Andrés Barba, translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

Published by Granta, 2020

Rating:

An air of foreboding hangs over this almost fable-like tale, which looks at the community response to the sudden appearance of 32 seemingly feral children in the subtropical town of San Cristobal. Seeming to speak their own language, and growing increasingly hostile towards the locals, tensions rise as the divide between “us” and “them” grows ever wider.

An air of foreboding hangs over this almost fable-like tale, which looks at the community response to the sudden appearance of 32 seemingly feral children in the subtropical town of San Cristobal. Seeming to speak their own language, and growing increasingly hostile towards the locals, tensions rise as the divide between “us” and “them” grows ever wider.

With our narrator reflecting on the events some 20 years later, Barba is able to add a wistfulness; the nostalgia, pathos, and regret that come with time and hindsight. It also means we, the readers, know from the very first sentence that the story will end with the deaths of all 32 children. This isn’t a crime-mystery in any traditional sense, but if it was, Barba is concerned entirely with the how, why, and who, rather than the outcome itself. Framing the story in this way instantly adds intrigue as we trudge towards certain tragedy, but with the entire narrative hinging on the Big Reveal, I’m sorry to say the answers that finally arrived in the book’s closing pages proved distinctly underwhelming. With so many powerful possibilities hinted at along the way, by comparison, the route Barba ultimately chose failed to impact me from an emotional, narrative, or thematic perspective.

On a more positive note, the atmosphere throughout is suitably cloying, and Barba flirts with lots of big, fascinating themes. These include: The human need for control, and fear of what we cannot understand; our ability to other those who go against the grain, dehumanising them so we can better justify our resistance; the idealised innocence we project onto children, and the imposition we feel when they fail to meet the ascribed moral standard; how much of our “humanity” is in fact a construct that serves to deny our true animalistic nature; and whether or not children retain closer links to this wild past. He also draws parallels between the adults’ reaction to the children and society’s hostile resentment of indigenous people, which I thought was subtle though effective.

It’s impressive that Barba manages to introduce so many ideas within the scope of a comparatively small word count. That said, I kept waiting for the sucker-punch that sadly never arrived. I also felt there were occasional examples of clumsy writing where the female characters were concerned, but I could never quite decide if the protagonist’s odd way of speaking about his wife and step-daughter was a deliberate quality of the character, or if it came directly from the author.

Ultimately offering more questions than answers, this contemplative, unnerving morality tale is certainly a good springboard for thought and discussion, but its uneven execution and failure to delve as deep as it could have hint at untapped potential.

February 23, 2021

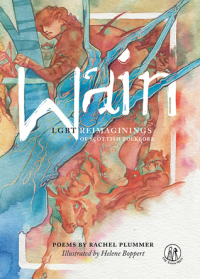

Wain by Rachel Plummer | Book Review

Wain by Rachel Plummer

Published by The Emma Press, 2019

Rating:

As a queer parent, Plummer was disappointed by the lack of representation for families like theirs in her daughter’s beloved fairy tales. Thus, the idea for Wain was born: a collection of poems that reimagine the traditional folktales of Scotland from the perspective of LGBT+ characters.

As a queer parent, Plummer was disappointed by the lack of representation for families like theirs in her daughter’s beloved fairy tales. Thus, the idea for Wain was born: a collection of poems that reimagine the traditional folktales of Scotland from the perspective of LGBT+ characters.

I was so pleased to see how inclusive of the queer community this collection actually is. Many books that claim to be proud “LGBT” reads represent one or two of those letters at best. In Wain, Plummer presents us with characters who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and non-binary, as well as those who don’t ascribe to any clear category, and all in a sensitive, normalized way that avoids the need for labels.

Deliberately written to be engaging for teens, the poems are highly accessible from a linguistic, structural, and rhythmic perspective. While this means they rarely wowed me as an adult reader, they were still well crafted and charming. On the whole, I adored the collection for its narrative content and thematic intention.

My favourite individual piece was Green Lady. Inspired by the stories of green-hued ghosts that are said to haunt Scottish castles and manor homes as a mark of familial secrets, Plummer reimagines one such ghost as a trans woman, utilising evocative colour-based imagery, with subtle, tragic implications adding real pathos and power to the poem’s deeper meaning.

Helene Boppert (who is also openly queer) provides stunning watercolour illustrations that make the book truly sing. Suitably otherworldly and ethereal in honour of the stories’ fantastical undertones, it’s likely no coincidence that she employs a vivid rainbow spectrum of colour throughout her chosen palette.

A few of my favourite illustrations from throughout the book

Representation is so important. It’s wonderful that this book exists, brought to life by two own-voice queer creatives, so that LGBT+ teens, adults, and families can see themselves reflected in the kind of stories we’re all brought up on, but which so often fail to acknowledge them.

February 20, 2021

Jackie Morris & Jennifer Hosein | Mini Reviews

The Quiet Music of Gently Falling Snow by Jackie Morris

Published by Graffeg, 2016

Rating:

Morris is one of my favourite artists, and in this collection of illustrated short stories, she proves herself an equally skilled writer.

The project has unique origins. Originally commissioned as an ongoing series of music-themed Christmas cards for the charity Help Musicians UK, the images were created across a span of 17 years. With recurring characters and motifs throughout, and Morris’s signature style tying them all together within the same dreamlike world, she collated the pieces and used them as a jumping off point for a series of interconnected stories.

Reading like fairy tales, Morris proves her prose is just as capable of establishing an ethereal, immersive atmosphere, and beautifully setting a scene as her artwork:

“Listen.

In the still, cold air of early morning there would be only silence but for the quiet music of gently falling snow. No leaves cling to the trees. Beneath stone-hard ground snakes sleep, coiling in cold dreams.

Winter.”

Most of the stories are brief, offering up an enchanting snapshot while remaining vague enough for the reader to embellish. As Morris explained in the introduction:

“My hope is that the threads of stories will wrap around the dreams of others and spin fine gold threads to catch the imagination.”

A Map of Rain Days by Jennifer Hosein

Published by Guernica Editions, 2020

Rating:

In this collection of poems, Hosein tackles numerous big topics, including abusive relationships, the painful loss of her mother, the emotional strain of trauma, and the racism she faces as a POC living in Canada. All are approached with honesty and verve, employing simple yet effective imagery to hit home her themes:

In this collection of poems, Hosein tackles numerous big topics, including abusive relationships, the painful loss of her mother, the emotional strain of trauma, and the racism she faces as a POC living in Canada. All are approached with honesty and verve, employing simple yet effective imagery to hit home her themes:

“I took you in / and you took me over / the way a spark / consumes a forest”

“You have no vision / of the carcass of youth / that lies ahead / the swill and gore of it”

The strongest section for me is the one that opens the collection, exploring the gradual, heartrending loss of her mother. Hosein captures the uniquely painful time in life in which your parents come to rely on you for care, just as your children reach independence, reflecting the mother-daughter relationship from both perspectives. The section that explores her experiences as the daughter of immigrant parents is also very strong, exploring the internalised shame she felt as a child, the flames of which were fanned by the 2016 election result.

“I was always dark / concrete / a blood-spot / on a crisp / white shirt / They tried to / scrub me / wipe me / cut me out / Every day / it took an army / of pains / to prepare a face / to confront the world”

These sections open the book so strongly that the rest fails to reach the same heights by comparison. Some smaller pieces fail to add much to the overall impact, meaning the collection ultimately feels overlong. A more streamlined selection would have allowed the real gems to shine, but I’m still glad to have discovered Hosein’s work.

Thank you to the publisher for a free advanced copy in exchange for an honest review.

February 15, 2021

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson | Book Review

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson

Published by Grove Press, 2021

Rating:

Open Water follows a young Black British couple through their tentative yet passionate relationship, as they attempt to navigate their feelings for each other (and themselves) within the context of systemic racism.

Open Water follows a young Black British couple through their tentative yet passionate relationship, as they attempt to navigate their feelings for each other (and themselves) within the context of systemic racism.

As the central couple’s love blossoms, so too does their friendship. This raises the stakes in terms of what they stand to lose should things not work out, with the author capturing how simultaneously beautiful and daunting it can be to fall for your best friend. Caleb Azumah Nelson also does a fantastic job of conveying the difficulty inherent to being open with someone when society has conditioned you to supress so much of yourself; the struggle to accept happiness when you’ve been made to feel like you don’t deserve it, as so many Black people have.

The physicality of their relationship is so important; to find intimacy, safety, and understanding with a fellow Black body, when to simply exist within one is to be at risk on the street. I also really admired the recurring look at the importance of the arts as a means for Black people to explore and express their cultural identities on their own terms, when they are otherwise made to feel unseen and unheard.

The author has such a knack for sustaining a very specific mood. An air of balmy heat hangs over the entire narrative, the balance of nostalgia and melancholy making for a hugely absorbing experience. In terms of descriptive detail, an ability to create atmosphere, and to convey emotional depth, the prose is fantastic. The only blips for me throughout the whole reading experience were a few instances in which the dialogue felt awkward; characters striving for philosophical profundity in situations that didn’t feel entirely believable. One of the book’s key narrative and emotional peaks is also framed in a needlessly convenient, thematically heavy-handed way, when the rest of the book is carried by such an understated grace.

Initially, I was hesitant about the book being presented in second-person, as though addressed directly to the reader. This is a notoriously difficult device to pull off, and though I worried it was going to feel like a superfluous creative choice, its relevance becomes clear as the story progresses; ultimately serving as an astute means of furthering the author’s look at identity, and the struggle to truly see yourself without first stepping back to take in the bigger picture.

Tender, wise, and moving, Open Water appears unassuming, but ultimately lands a sucker punch. It marks Caleb Azumah Nelson as an exciting new voice on the literary scene, and I can’t wait to see what he does next.

Thank you to the publisher for a free advanced copy in exchange for an honest review.

February 12, 2021

Pádraig Kenny & Kae Tempest | Mini Reviews

The Monsters of Rookhaven by Pádraig Kenny

Published by Henry Holt & Company, 2020

Rating:

I picked this up knowing very little about it (due in part to a deliberately vague blurb), and there was definitely an element of my expectations not matching what the book actually set out to offer. I was anticipating something gothic and unsettling that flirted with magical realism, akin to Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. Instead, I got a middle grade-leaning fantastical story with a campy-horror vibe, more akin to The Addams Family.

I picked this up knowing very little about it (due in part to a deliberately vague blurb), and there was definitely an element of my expectations not matching what the book actually set out to offer. I was anticipating something gothic and unsettling that flirted with magical realism, akin to Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. Instead, I got a middle grade-leaning fantastical story with a campy-horror vibe, more akin to The Addams Family.

We follow a ragtag family of strange “monsters” who live together in a mansion kept hidden from humans by magic. When the barrier protecting them is breached, two orphaned siblings on the run stumble into their hidden world, and drama ensues from there, as the monsters come into conflict with the residents of the neighbouring village. Though it never delves very deep, the story does touch on some nice themes, like the concept of found family, and the idea that real monsters hide among us, causing division by spreading fear of the Other. It also pays homage to several staples of the horror genre in fun little ways.

I appreciated the contrast between the slow-burn first half that focuses on establishing characters and lore, and the breathless latter-half that really ramps up the stakes. That said, there are definitely lapses in logic when it comes to the world-building and characterisation. If you can suspend your disbelief and submit yourself to the wildness of the ride, this certainly has its charm.

On Connection by Kae Tempest

Published by Faber & Faber, 2020

Rating:

Performance poet, musician, and novelist Kae Tempest has written an extended essay that explores the role of creativity in fostering connections throughout society.

Performance poet, musician, and novelist Kae Tempest has written an extended essay that explores the role of creativity in fostering connections throughout society.

Nuanced and self-aware, the book opens with Tempest acknowledging their own privileges as someone who grew up white and middle-class, highlighting the problematic nature of a blanket call for unity. By recognising the validity (and necessity) of vocal pushback against injustice (like the BLM, MeToo, and TransLivesMatter movements), they embrace rather than dismiss the idea of difference. Instead of reductively claiming, “we’re all the same”, Tempest goes on to argue that the constantly evolving relationship between artist, art, and audience makes creativity a vital tool in bridging, rather than denying, our differences. Providing us with an opportunity to process, explore, and express our individuality (when creating ourselves), or to empathize with, educate ourselves on, and understand different perspectives (when engaging with someone else’s creative output), we can find common ground that transcends potential division.

Tempest completed and published the book during the covid-19 pandemic. The context of widespread isolation and the catastrophic impact it has had on individuals’ mental health, as well as the creative arts world at large, adds a whole other layer of resonance to its look at the importance of connection. Somehow, it allows the book to feel both timeless and very much of the now. And while a couple of points can feel somewhat tenuous, beyond anything else, the work cements Tempest as one of the most interesting, observational, engaging, and galvanising voices at work today.

February 8, 2021

The Butchers’ Blessing by Ruth Gilligan | Book Review

The Butchers’ Blessing by Ruth Gilligan

Published by Tin House Books, 2020

Rating:

Set amidst the devastating outbreak of “Mad Cow Disease” in the 1990s, The Butchers’ Blessing is an achingly real portrayal of rural life in Ireland and an ode to the Republic’s fraught history with its own folklore.

Set amidst the devastating outbreak of “Mad Cow Disease” in the 1990s, The Butchers’ Blessing is an achingly real portrayal of rural life in Ireland and an ode to the Republic’s fraught history with its own folklore.

The book opens with a disturbing tableau — the image of an unidentified body suspended from a hook — before jumping back to explore the events that would lead to this man’s grotesque end. It’s a beginning of instant intrigue, and the stakes are consistently raised as we attempt to identify the victim and the perpetrator from a cast of complex, morally ambiguous characters.

The narration is split between five key perspectives: Úna, a preteen girl whose father is one of eight enigmatic Butchers (men who travel the country slaughtering cattle according to controversial traditional customs believed to stave off an ancient curse); Grá, Úna’s mother, who feels trapped in a cold marriage with her absent husband; Fionn, an aging farmer desperate to save his ailing wife to atone for his violent past; Davey, Fionn’s son, who dreams of escaping to the freedom of a cosmopolitan city; and Ronan, a photographer from out of town who longs to make a name for himself.

You can read my full review over on BookBrowse. I also wrote a piece about the legacy or Ireland’s curses to go alongside it, which you can find here.

February 3, 2021

Emily Pattinos & Iain S. Thomas | Mini Reviews

I’ve been on a real poetry kick recently, so in this post I’m reviewing a couple of ARCs for upcoming collections I was grateful to receive through Netgalley.

The Last Unkillable Thing by Emily Pattinos

Published by University of Iowa Press, 2021

Rating:

In this collection of poems, Pattinos explores the loss of her father and the complexities this brings to her relationship with her mother. With its seamless shifts between anger, sorrow, humour, and tenderness, it encapsulates the breadth and complexity of emotion inherent to the grieving process, despite its relative brevity.

In this collection of poems, Pattinos explores the loss of her father and the complexities this brings to her relationship with her mother. With its seamless shifts between anger, sorrow, humour, and tenderness, it encapsulates the breadth and complexity of emotion inherent to the grieving process, despite its relative brevity.

Anchoring the collection is the recurring motif of the natural world. Pattinos evokes scenes with razor-sharp precision; its enduring beauty in the wake of her sadness as much a frustration as it is a comfort. Though subtly handled, the changing of the seasons can also be seen as reflective of her own journey towards healing.

The collection arguably lacks standout pieces that I’ll be able to recall on their own, making it the kind I will remember more for its overall impression, but it was certainly a tight, focussed selection of work.

Thank you to the publisher for a free advanced copy in exchange for an honest review.

The Truth of You by Iain S. Thomas

Published by Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2021

Rating:

This is a case of a poetic style that just isn’t for me, sadly. Without wanting to sound dismissive of the writer’s work, it’s what I would describe as very surface level, with most of the pieces barely a few lines long. In this respect, most feel like the rough outline of an idea, rather than a fleshed-out poem.

This is a case of a poetic style that just isn’t for me, sadly. Without wanting to sound dismissive of the writer’s work, it’s what I would describe as very surface level, with most of the pieces barely a few lines long. In this respect, most feel like the rough outline of an idea, rather than a fleshed-out poem.

There’s no depth to mine in terms of word choice, rhythm, imagery, structure, and so on. Instead, everything is presented in a straight-forward, matter-of-fact way that makes the collection read more like a thought journal. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course, and I don’t doubt those who enjoy sentimental writing presented in an earnest way will find more to connect with. It’s certainly contemporary and accessible, good perhaps for those who otherwise feel intimidated by the form. But for me, it aimed so stringently for universal relatability that it failed to bring anything new or interesting to the table on a thematic or linguistic level.

Thank you to the publisher for a free advanced copy in exchange for an honest review.