K.D. Dowdall's Blog, page 41

March 22, 2018

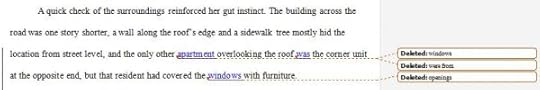

Line Editing: What Is It? By Jami Gold

What Is Line Editing and What Should Line Editors Do? by Jami Gold

Last month, when I put together the Master Lists of writing craft skills to provide insights for self-editing and/or finding editors, I created a list for each phase of editing:

content/developmental editing (fix story and character-level issues)

line editing (fix scene and paragraph-level issues)

copy editing (fix sentence, word, and grammar-level issues)

As I mentioned in the Line Editing post, in my experience, line editing is the hardest type of editing to nail down. We can say that line editing is about how we write scenes and paragraphs, but what does that mean?

Let’s take a closer look at what line editing encompasses…

Why Is Line Editing Hard to Define?

While developmental editing is about the story and characters and copy editing is about grammar rules and sentence-level issues, line editing skills are all about our writing—as a whole:

our voice

our style

our techniques

our choices

Despite how line editing skills overlap those of developmental editing and copy editing, the skills also go far beyond looking at character arcs or knowing grammar and into becoming deeply in tune with an author’s voice. Talented line editing can make our writing sing, and the step shouldn’t be skipped.

Do We Need a Professional Line Editor?

Unfortunately, many writers have probably never been exposed to good line editing to recognize it (or its lack). It’s rare for a beta reader or critique partner—or even an English teacher—to have the necessary skills to be a good line editor. Due to the difficulty in finding non-professionals with the necessary line editing skills, my “default” recommendation as far as editing is:

For most writers, if we can afford to pay only one professional editor, we should get a professional line edit.

However, many editors who call themselves line editors actually perform more of a copyedit. It’s essential to get a sample edit from a potential editor to see what kind of changes they’re suggesting—and whether or not their changes are good for our voice, etc.

What should a professional line edit include? Check this list of examples… CLICK TO TWEET But that brings up the issue: If it’s so hard to define or recognize good line editing, how can we find a good line editor?

The first step is to learn more about what line editors do (or should do). The better we understand this stage of editing, the more we’re able to self-edit for these issues or judge whether a sample edit from someone calling themselves a line editor reveals if they’re actually looking at the right things.

Once we know whether a potential editor measures up, skill-wise, we can then focus on whether they’re a good match for our voice. I hesitate to ever recommend specific editors because we all have different strengths and weaknesses, but our individual needs are never more important than finding a line editor who’s a good match for our voice.

No matter how skilled the line editor, we should stay far away from any who don’t “get” our voice. *smile*

What Should Line Editors Do? The Basics…

Line editing focuses on clarity and strength in our writing, such as:

Are any sentences clunky or confusing?

Do any motivations need to be made clearer?

Are any phrases too cliché?

Do any sentences or paragraphs need to be tightened?

Are any sentences or paragraphs too repetitive?

Would different words make a stronger emotional impact?

Would showing or telling make a point more effective?

Would rearranging any sentences or paragraphs help the storytelling flow or have emotional focus?

In my post a few years ago about how we can evaluate potential editors, I gave a few examples of line-editing comments:

“I feel like her words should directly follow this. See what you think of the new arrangement.”

“This wording is a little awkward, and I would add a sentence or two showing her decision.”

“You can cut this. We know it already.”

“This almost goes without saying. Could you use a more descriptive adverb, or better yet, phrase?”

Note how these comments get into reading flow, clarity, tightening, and stronger writing. These are what we’re looking for with line edits. (Also note how these comments get into the nitty-gritty of how we word things. That’s why we need our line editor to be in tune with our voice.)

What Should Line Editors Do? More Examples…

I love how line editing makes my voice and writing stronger, so I want to give more insights into what a good line edit can do for us. I hope these examples give us more ideas about the types of self-editing we can do as well as what we should look for when evaluating potential line editors.

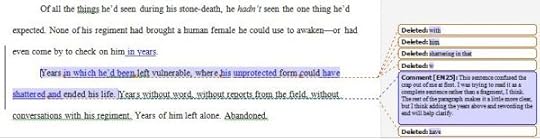

In my Line Editing Master List post, I organized line-editing skills into several categories. Using many of those same categories, here are some of the comments I received from my line editor on my latest release, Stone-Cold Heart:

Structure Scenes

Scene structure is usually a developmental editing step, but this is one of those areas that can overlap with line editing—especially when it comes to narrow story issues, repetition of ideas, and story/emotional flow.

“What’s the deal with this? Where did it come from?”

“That’s DEFINITELY something I’d expect her to ask about.”

“Would this not cause problems in the world?”

“I think it’s fine to have this new POV scene this way. It’s not like there’s any other way to reveal this info. The only other thing you could do to make it slightly less jarring would be to put a prologue in her POV.”

“I would cut this and move it down to AFTER her explanation so you don’t cut the tension of us waiting to see what happens, with all the backstory.”

“I pictured them still on the couch and assumed she was either talking to them from the kitchen or had come back into the living room, so I’m confused about when they decided to join her.”

“Insert scene break.”

Structure Paragraphs and Sentences

Paragraph and sentence structure is the “meat” of line editing, ensuring ideas are expressed with strength and clarity.

“Three prepositional phrases in a row is the absolute max. I prefer no more than two because it gets overwhelming, but I’ll let you decide if there’s an easy way to rework this.”

“Feels redundant. I don’t think you need both of these.”

“Cut. This goes without saying, as we see this already.”

“I don’t see any need for the paragraph break.”

“Closer implies comparison, but what are you comparing here?”

“Wrenched what?”

“Unclear who’s speaking here.”

“This sentence has too much going on. Can you split it into two?”

“Maybe change to “it doesn’t matter” or something similar. “No” is a confusing answer here.”

“This is a little hard to picture.”

“This is a little clunky. Reword if you can.”

“Even going back to review the last page, it’s not immediately clear what excuse you’re referring to.”

“Odd word choice. I feel like this word implies the opposite.”

Tightening sentences is also a major aspect of line editing, as in these screenshots:

(Newsletter readers need to click through to the post to see the images. Click on the images to see full size.)

Develop Voice

As I mentioned above, voice is the trickiest aspect of line editing. A line editor who’s not a good match for us will try to “fix” our voice choices into something dull, but a good match will help us make our voice stronger and sharper.

“You know me and repetition, but using the different form of the word in the first sentence throws it off. Do you think changing it to match the other two makes it too much? What if you combine the last two sentences?”

“I think you may be over-using this word. The idea is well established at this point, and I don’t think the particular word needs to be repeated quite so many times.”

“I feel like a pause before this is necessary to emphasize it. Comma, em dash, ellipsis, your choice.”

“Try adding this understatement to make it funnier.”

“Sounds too formal.”

“I would maybe draw out these words with ellipses.”

“Some writers would use hyphens to make this into one idea. I was just reading something in an editor forum that said that’s considered lazy writing. Meh. Who knows?

But the italics are a little odd as well. You could rephrase.”

“Technically these are comma splices. Which I’m sure you know. I would probably use periods here, but I can see wanting to tie it all together, so I’ll look the other way if that’s what you choose.

Stock and Cloned Characters in Storytelling

by Melissa Donovan on March 15, 2018 ·

I was recently reading a novel, and a few chapters in, I realized I had mixed up two of the main characters. In fact, I had been reading them as if they were a single character. I’m a pretty sharp reader, and this has never happened before, so I tried to determine why I’d made the mistake. Was I tired? Hungry? Not paying attention?

I went back and reviewed the text and noticed that these two characters were indistinct. They were so alike that without carefully noting which one was acting in any given scene, it was impossible to differentiate them from each other. They were essentially the same character. Even their names sounded alike.

This got me to thinking about the importance of building a cast of characters who are unique and distinct from each other instead of a cast of stock characters who are mere clones of one another.

Stock Characters

We sometimes talk about stock characters in literature. You know them: the mad scientist, the poor little rich kid, the hard-boiled detective. These characters have a place in storytelling. When readers meet a sassy, gum-popping waitress in a story, they immediately know who she is. They’ve seen that character in other books and movies. Maybe they’ve even encountered waitresses like her in real life. These characters are familiar, but they’re also generic.

When we use a stock character as a protagonist or any other primary character, we have to give the character unique qualities so the character doesn’t come off as generic or boring. It’s fine to have a sassy, gum-popping waitress make a single appearance in a story, but if she’s a lead character, she’s going to need deeper, more complex development so the readers no longer feel as if they already know her. She has to become fresh and interesting.

Stieg Larsson did this brilliantly in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and the sequels that made up the Millennium trilogy. At first the protagonist, Lisbeth Salander, seems like a surly punk, the kind of character we’ve seen a million times before. As the story progresses and Lisbeth moves to center stage, we learn there’s more to her than meets the eye. She’s antisocial, and she’s a computer genius. She’s bold, brave, and tough. She’s not just some surly punk. She is a moral person with unique challenges — one of the most intriguing characters in contemporary fiction.

Cloning Characters

Stock characters are often taken from source material, sometimes as an homage and other times as a blatant rip-off. Such characters are problematic when they feature prominently in a story and have no traits that differentiate them from the character upon which they are based. Do you want to read a story about a boy wizard named Hal Porter who wears glasses and has a scar on his forehead? Probably not, unless it’s a parody of Harry Potter, whom we all know and love.

You can certainly write a story about a young wizard who is based on Harry Potter, but you have to differentiate your character from Harry. Make the character a girl, give her a hearing aid instead of glasses, and come up with a memorable name that doesn’t immediately bring Harry Potter to mind. And give your character her own personality and challenges.

As the book I was recently reading demonstrates, we also have to watch out for cloning characters within our own stories. For most writers, this is a bigger problem than cloning characters out of other authors’ stories.

Think about it: you are the creator of all the characters in your story. You might have based them on people or characters you know and love (or loathe). You might have conjured them from your imagination. But they are all coming from you: your thoughts, your experiences, and your voice.

While I’ve never mixed up two characters in a book I was reading before, I have noticed that characters who act, think, and speak similarly are common. And while a cast of characters who are similar to each other in every way imaginable doesn’t necessarily make a story bad, a cast of characters who are noticeably distinct from each other is much better.

Nature vs. Nurture: How to Avoid Cloned Characters

Cloning is the practice of making a copy of something, an exact replica. You can clone a human being (or a character), but once the clone comes into existence, it will immediately start changing and becoming different from the original. Its personal experiences will be unique. By nature, the original and the clone are exactly the same, but nurture (or life experience) will cause the clone to deviate from the original.

Here are some tips to make sure your characters are unique and not clones of each other or any character or person they are based on:Give your characters distinct and memorable names. Avoid giving characters name that sound alike. Don’t use names that start with the same letter and are the same length, and don’t use names that rhyme.

1.Give your characters distinct and memorable names. Avoid giving characters name that sound alike. Don’t use names that start with the same letter and are the same length, and don’t use names that rhyme.

2.Unless you’re writing a family saga, make sure your characters don’t all look alike. Try developing a diverse cast of characters.

3.Characters’ speech patterns will depend on where they’re from, but individuals also have their own quirky expressions and sayings. Use dialogue to differentiate the characters from each other. Maybe one character swears a lot while another calls everyone by nicknames.

4.Create character sketches complete with backstories. If you know your characters intimately, you’ll be less likely to portray them as a bunch of clones.

5.To help you visualize your characters, look for photos of actors, models, and other public figures that you can use to help your imagination fill in the blanks.

6.Once you’ve created your cast, ask whether any of them are stock characters. If any of your primary characters feel like stock characters, make them more unique.

Are You Using Stock Characters? Are Your Characters a Bunch of Clones?

The main problem with the book I mentioned at the beginning of this post was that there were two characters who were essentially functioning as a single entity, at least for the first four or five chapters, which is as far as I got in the book. Together, they shared the same purpose or function within the story. The best fix for that problem would have been to combine the two characters into a single character, something I have had to do in one of my fiction projects that had a few too many names and faces.

I can’t help but wonder if the author ever bothered to run the manuscript by beta readers, and since the book was traditionally published, I wondered how the cloned characters made it past the editor.

How much attention do you pay to your characters when you’re writing a story? What strategies do you use to get to know your characters and make sure they are all unique? Have you ever noticed stock characters or cloned characters in a story you’ve read? Share your thoughts by leaving a comment, and keep writing!

March 19, 2018

…scoff not at the honest endeavours of others…

This is wonderful! And, every writer and author should read this post-haste! You will love it! thank Seumas Gallacher!

…to every man, woman, and child who ever picked up a pen or pencil, tapped at a typewriter, clicked at a keyboard, in an effort to WRITESUM’THING out of their own imagination, I salute yeez… each and every one of yeez… heroes and heroines all… lately, I saw a Facebook exchange about what constitutes a ‘good’ writer, a ‘successful’writer, a writer ‘of note’, which discussion also included some gratuitously offensive commentary on certain scribblers whose material didn’t ‘meet the expectations’ of some readers… I call those sniper ‘critics’ cringeworthy carpers, pedantic peddlers, humbugging hussies… I wonder how many of those, so quick to relegate so readily to the dustbin the literary effort of others, have ever written a book themselves?… I recall the time this ol’ Scots Jurassic completed my first novel… my maiden sortie into the universe of the wordsmith, THE VIOLIN MAN’S LEGACY… it was…

View original post 211 more words

March 18, 2018

Favorite Poems I Like: #1- “The Child In The Garden.”

This simple, yet complex poem, played on my heart-strings, because it is so true.

REFLECTIONS OF A MINDFUL HEART AND SOUL

REFLECTIONS OF A MINDFUL HEART AND SOUL

When to the garden of untroubled thought

I came of late, and saw the open door,

Found on Pinterest on 6-11-17. Saved from meetup.com. Darkfire. Magic & Mysteries.

Found on Pinterest on 6-11-17. Saved from meetup.com. Darkfire. Magic & Mysteries.

And wished again to enter, and explore

The sweet, wild ways with stainless bloom inwrought,

And bowers of innocence with beauty fraught,

It seemed some purer voice must speak before

I dared to tread that garden loved of yore,

That Eden lost unknown and found unsought.

Then just within the gate I saw a child,-

A stranger-child, yet to my heart most dear;

He held his hands to me, and softly smiled

With eyes that knew no shade of sin or fear:

“Come in,” he said,“and play awhile with me;

I am the little child…

View original post 112 more words

March 17, 2018

HAPPY ST. PATRICK’S DAY!

March 16, 2018

How to Jumpstart Book Reviews for Self-Published Books!

[image error]BY JOEL FRIEDLANDER ON JANUARY 15, 2018

It’s never been a better time to be a self-published author, and there have never been more book reviewers available to the writer who decides to go indie.

Book reviewers help spread the message about your book by publishing a review to their own network. But if you’re new to publishing, you have to figure out how to get those book reviews that can bring you more readers.

First, Get Your Kit Together

Before you go hunting for reviewers, make sure you’ve got the essentials you’ll need. At the minimum you should have:

Either a PDF or an ePub of your book, or both. Include the covers, and also have the cover available as both a high-resolution (300 dpi) and low-resolution (72 dpi) graphics, preferably in JPG format

For print books, plenty of copies and mailing supplies. If you’re publishing via print on demand, order enough books to respond to reviewer requests, since you’ll need to add your marketing materials to the package.

Press release about the launch of your book. Try to make it sound like a story you would read in the newspaper.

Cover letter. This should be a brief introduction to you and your book, but keep it short.

Photos of the author. Again, you’ll need both high- and low-resolution images if you’re approaching both print and online reviewers.

Author biography. This is a good place to show your qualifications, particularly if you’re a nonfiction author.

There are lots of other things you can put in a press kit or a reviewer package, and you can find more about that here: Media Kits for Indie Authors

How to Find Reviewers

There are literally thousands of book bloggers online, and most of them review books even though they aren’t paid. Nevertheless, many are thoughtful reviewers and good writers, and have a significant following.

There are also reviewers offering paid reviews, and over the years this has become much more acceptable in the indie community. It’s one of the ways we get word out to readers about our books.

Paid reviews might work for completely unknown fiction authors, who have little chance to get exposure when they get started. Otherwise, use free review sources at first, it will be a long time before you run out of them.

Here are some recently updated resources that will help you locate reviewers:

Midwest Book Review welcomes self-published books, and their website is bulging with targeted information about book reviews and reviewers.

Indie Reader invites authors to submit their books for review, and they have become a trusted source for reviews. The site is run by authors and writers.

The Indie Author’s Guide to Free Reviews is an updated article from Publishers Weekly by By Daniel Lefferts and Alex Daniel with lots of excellent resources.

Indie View keeps an updated list of hundreds of reviewers.

Self-Publishing Review has been reviewing books since 2008 and also has lots of information about book marketing in general as well as an archive of great content.

Don’t forget the many reviewers who post on book-oriented sites like Goodreads, where you can also find genre-specific groups, too.

Reedsy has built an excellent list of Best Book Review Blogs of 2017. Authors can search by genre and filter out blogs that do not review indie books.

The Book Blogger List is another searchable curated list of online reviewers.

A recent interview with Jason B. Ladd, How To Get Book Reviews As An Unknown Author, with a great outline of the process of getting reader reviews.

For print reviewers, consider the programs run by the Independent Book Publishers Association. These mailings of books for review go to over 3,000 newspaper and magazine editors and reviewers.

There are an almost endless list of blog articles and books on this subject to research, too. Getting reviews is a standard part of book marketing, and you should plan on spending

Here are some recently updated resources that will help you locate reviewers:

Midwest Book Review welcomes self-published books, and their website is bulging with targeted information about book reviews and reviewers.

Indie Reader invites authors to submit their books for review, and they have become a trusted source for reviews. The site is run by authors and writers.

The Indie Author’s Guide to Free Reviews is an updated article from Publishers Weekly by By Daniel Lefferts and Alex Daniel with lots of excellent resources.

Indie View keeps an updated list of hundreds of reviewers.

Self-Publishing Review has been reviewing books since 2008 and also has lots of information about book marketing in general as well as an archive of great content.

Don’t forget the many reviewers who post on book-oriented sites like Goodreads, where you can also find genre-specific groups, too.

Reedsy has built an excellent list of Best Book Review Blogs of 2017. Authors can search by genre and filter out blogs that do not review indie books.

The Book Blogger List is another searchable curated list of online reviewers.

A recent interview with Jason B. Ladd, How To Get Book Reviews As An Unknown Author, with a great outline of the process of getting reader reviews.

For print reviewers, consider the programs run by the Independent Book Publishers Association. These mailings of books for review go to over 3,000 newspaper and magazine editors and reviewers.

There are an almost endless list of blog articles and books on this subject to research, too. Getting reviews is a standard part of book marketing, and you should plan on spending some time doing this for your own book launches.

5 Key Tips for Getting Book Reviews

Now that you have your materials together and access to lots of reviewers, you’re ready to go. Here are my 5 best tips for getting book reviews, whether online or off:

Pick the right reviewers. This is the single most important thing you can do to help your review program. Find out what kind of books the reviewer likes to review, and only select appropriate reviewers. Don’t just spam your contacts or people you know in unrelated fields. I do few book reviews on the blog, but I constantly get pitched by romance novelists, thriller writers, and just about everyone else. Save everyone time and effort by aiming your review requests in the right direction.

Query the reviewers. Check each reviewer’s requirements. Some want you to just send the book, but many ask for a query. Some review e-books, many do not. Conforming to their requirements saves both of you time. Check out this query letter tutorial.

Send the book. In your query make sure to offer both as many versions as you can of the book. You can use a PDF, an ePub or Kindle format, or a print copy. Let the reviewer decide how she wants to receive it.

Follow up. Don’t stalk or harass the reviewer, who is probably doing this in her spare time. But if you haven’t heard anything after a few weeks, follow up to see if they still intend to write the review.

Thank the reviewer. It’s common courtesy, but it also shows you appreciate the time and effort someone else took to help bring your book to the attention of more people. Every reviewer has an audience of some kind, and every audience can create network effects that spread the word about a book that really stands out.

Book reviews can be very effective in spreading the word. Nothing sells books as well as word of mouth, and you can get people talking about your book if you can bring it to their attention. Book reviews will do that for you. Consequently, an aggressive, ongoing book review program is one of the best ways for self-published authors to get attention for their books.

Something to Add?

In addition to the resources mentioned in this article, do you know of others for finding book reviewers, and particularly identifying top reviewers in your field? Any tips to share? Please let us know in the comments.

March 14, 2018

Why We Celebrate March 14th – Happy Pi (TT) Day !

[image error] Pi Day spotlights one of math’s most seductive numbers! by Dan Rockmore.

Why do we celebrate the number pi (π) on March 14? Because it’s the fourteenth day of the third month of the year, and 3 and 14 are the first three digits of pi’s decimal expansion. If you really want to show you’re a pi aficionado, you can start your celebration at 1:59 p.m. and 26 seconds, because with those five additional digits you have pi’s first eight digits: 3.1415926.

Those eight numbers are just the beginning of pi’s true value. Unlike most numbers we encounter in everyday life, pi has digits to the right of the decimal point that go on not just for a long time but forever — and in an unpredictable way. The Swiss mathematician Johann Heinrich Lambert proved that in 1761.

The short way to say this is that pi is an irrational number, one that cannot be represented as a fraction and thus has an infinite and never-repeating decimal expansion. And since the 19th Century, pi has been known to be transcendental, meaning that no combination of its powers can add up to a whole number. This distinguishes it again from more familiar irrational numbers like the square root of two (whose second power is equal to two).

REAL-WORLD REFLECTIONS

You don’t have to be a mathematician or even a “math person” to find pi fascinating. We all learned as students that pi represents the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, or, as we might put that mathematically, π = c/d. But not every student fully appreciates the fact that the ratio stays constant no matter how big or how small the circle.

Pi is an ideal. It characterizes the relationship between measurements of a perfect circle in a Platonic world. But we see its real-world reflection all around us. It’s present in coins, plates, those circular irrigation ponds you see from airplanes, and other familiar objects — pi is embedded within them all. The same is true for three-dimensional objects like spheres and cylinders. As long as something is round, pi applies.

And pi isn’t just about round things. Famously, it’s a piece of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, which quantifies the level of precision one can obtain when making measurements at the subatomic level. Closer to home, pi is part of a formula used to price investment risk. Pi both leaves nothing to chance and helps measures chance.

ANCIENT ORIGINS

Pi is as timeless as it is unchanging. Our ancestors knew about pi at least as far back as 4,000 years ago, even if a Greek letter wasn’t used to denote it until 1647. The Bible contains an implicit reference to pi: A cylindrical vat used by Hiram in the “Book of Kings” is said to measure 10 cubits across and 30 cubits around. (30/10 = 3, which at least gives the first digit of pi.) The ancient Egyptians and Babylonians made their own estimates of pi’s value, and Archimedes famously used a clever geometric argument to place the value of pi between 22/7 and 223/71.

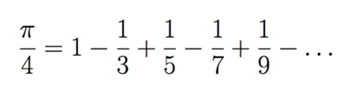

While both of those fractions come close to representing the actual value of pi, we’re always coming up with better ways to express pi’s value. Recent attempts tend to rely not on geometry but on mysterious formulas like the one often taught in first-year calculus:

Mathematical formula

Mathematical formulaAnd this is just one of many “infinite series” representations for pi.

The Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan — you may know him from the 1991 book and 2015 movie “The Man Who Knew Infinity” — owes his fame, in part, to his pursuit of elaborate formulas for the reciprocal of pi, or “one over pi” in the common parlance. Ramanujan’s formulas reveal mysterious connections between pi and patterns in prime numbers — whole numbers like 2, 3, 5, and 7 that are divisible only by themselves and one.

GOING TO EXTREMES

Fascinating as they are in their own right, formulas like Ramanujan’s provide the starting point for the “extreme computing” efforts to calculate pi we’ve all read about in recent years. In 2016, computer whiz Peter Trueb made headlines when he used an ingenious computational configuration to calculate pi to mind-blowing 22,459,157,718,361 decimal points.

Related

Americans have a nature problem. Is ‘biophilic design’ the solution?

While some people use computers to calculate ever-more-accurate values for pi, others memorize pi to thousands of digits and then recite them aloud in a public setting — as if reciting a sonnet for robots. The current Guiness Book world record holder here is Rajveer Meena from India, who in 2015 recited 70,000 digits of pi before stopping.

So while we differ in the ways we think about pi and work with pi, we can all come together today to celebrate the seductive powers it has over our minds. So on this March 14, take a moment to contemplate this remarkable constant — maybe over a slice of pie. Here in Dartmouth’s math department, we’ll have a nice selection — and we’ll start at precisely at 1:59 and 26 seconds.

Just for good measure.

Get the Mach newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

March 12, 2018

10 Things that Red-Flag a Newbie Novelist by Anne R. Allen

10 Things that Red-Flag a Newbie Novelist by Anne R. Allen

Beginning novelists are like Tolstoy’s happy families. They tend to be remarkably alike. Certain mistakes are common to almost all beginners. These things aren’t necessarily wrong, but they are difficult to do well—and get in the way of smooth storytelling

They also make it easy for professionals—and a lot of readers—to spot the unseasoned newbie.

When I worked as an editor, I ran into the same problems in nearly every new novelist’s work—the very things I did when I was starting out.

I think some of the patterns come from imitating the classics. In the days of Dickens and Tolstoy, novels were written to be savored on long winter nights or languid summer days when there was a lot of time to be filled. Detailed descriptions took readers out of their mundane lives and off to exotic lands or into the homes of the very rich and very poor where they wouldn’t be invited otherwise.

Books were expensive, so people wanted them to last as long as possible. They didn’t mind flipping back and forth to find out if Razumihin, Dmitri Prokofitch, and Vrazumihin were in fact, all the same person. They were okay with immersing themselves in long descriptions and philosophical digressions before they found out what happened to Little Nell. The alternative was probably staring at the fire or listening to Aunt Lavinia snore.

But in the electronic age…not so much. Your readers have the world’s libraries at their fingertips, and if you bore them or confuse them for even a minute, they’re already clicking away to buy the next shiny 99c book.

Whether you’re querying agents and editors or you’re planning to self-publish, you need to write for the contemporary reader. And that means “leaving out the parts that readers skip” as Elmore Leonard said.

Agents and readers aren’t going to want to wade through a practice novel. They want polished work. All beginners make mistakes. Falling down and making a mess is part of any learning process. But you don’t have to display the mess to the world. Unfortunately easy electronic self-publishing tempts us to do just that.

But don’t. As I said two weeks ago, it takes the same amount of time to learn to write as it did before the electronic age.

Here are some tell-tale signs that a writer is still in the learning phase of a career.

I’m not saying these things are “wrong”. They’re just overdone or tough for a beginner to do well.

1) Show-offy prose

Those long, gorgeous descriptions that got so much praise from your high school English teacher and your critique group can unfortunately be a turn-off for the paying customer who’s digging around for some kind of narrative thread or reason to care.

People read novels to be entertained, not to fulfill the needs of the novelist. If you’re writing because you crave admiration, you’re in the wrong business. The reader’s right to a story—not the novelist’s ego—has to come first.

If there’s no story, no amount of verbal curleques will keep the reader interested. Give us story first, and then add embellishments. But not too many.

Also, even though it may be really fun to start every chapter with a Latin epigraph from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, unless it’s really important to the plot, this will probably annoy rather than impress readers.

Ditto oblique references to Joyce’s Ulysses or anything by Marcel Proust. People want to be entertained, not take a World Lit quiz. (And yes, I went there myself. Originally, every chapter title of The Gatsby Game was a quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald. Nobody cared.)

2) Head-hopping

Point of view is one of the toughest things for a new writer to master. Omniscient point of view is the hardest to do well, because it leads to confusion for the reader.

But a lot of beginners write in omniscient because they haven’t mastered the art of showing multiple characters’ actions through the eyes of the protagonist.

But be aware that third-person-limited narration (when you’re only privy to the thoughts and feelings of the protagonist) is the norm in modern fiction (with first person a close second in YA.) If you use anything else, your writing skills need to be superb or you’ll leave the reader confused and annoyed.

And you’ll red-flag yourself as a beginner.

3) Episodic storytelling

I think nearly every writer’s first novel has this problem. Mine sure did.

I could never end it, because it didn’t actually have a single plot. It was a series of related episodes, like a TV series—the old fashioned kind that didn’t have a season story arc.

Critique groups often don’t catch this problem, if each episode has a nice dramatic arc of its own.

Every piece of narrative has to start with an inciting incident that triggers ALL the action in the story, until it reaches a satisfying resolution at the end. It’s called a story arc.

If you don’t have a story arc, you don’t have a novel. You have a series of linked stories or vignettes. But novel readers want one big question to propel them through the story and keep them turning the pages.

The writer who blogs as Mooderino has a great post on why we want to avoid episodic narrative, even though it worked with some classics like Alice in Wonderland.

4) Info-dumps and “As you Know Bob” conversation

When the first five pages of a book are used for exposition—telling us the names of characters, what they look like, what they do for a living, and details of their backstories—before we get into a scene, you know you’re not dealing with a professional.

Exposition (background information) needs to be filtered in slowly while we’re immersed in scenes that have action and conflict. This takes skill. The kind that comes with lots of practice.

Another big clue is info-dumping in conversation, often called “as-you-know-Bob”:

“As you know, Bob, we’re here investigating the murder of Mrs. Gilhooley, the 60-year-old librarian at Springfield High School, who may have been poisoned by one Ambrose Wiley, an itinerant preacher who brought her a Diet Dr. Pepper on August third….”

Thing is, Bob knows why he’s there. He’s a forensics expert, not an Alzheimer’s patient. Putting this stuff in dialogue insults the reader’s intelligence, since nobody would say this stuff in real life. (In spite of the fact you hear an awful lot of it on those CSI TV shows.)

5) Mundane dialogue and transitional scenes that don’t further the action.

All that “hello-how-are-you-fine-and-you-nice-weather” dialogue may be realistic, but it’s also snoozifying.

Readers don’t care about “realism” if it doesn’t further the plot. As James Patterson, the bestselling author in the world says, “realism is overrated.” Readers want “just the good parts.”

That also means skipping the trip from the police station to the crime scene and the lunch breaks when nothing happens except the MC doing some heavy musing and doughnut chomping.

Ditto the endless meetings or arguments where people come to decisions after tedious deliberation. Those are an exception to the rule of “show don’t tell.” Let us know the outcome, not the snoozerific details.

Just make a break in the page and plunge us into the next scene.

6) Tom Swifties and too many dialogue tags

The writer who strains to avoid the word “said” can rapidly slide into bad pun territory, as in the archetypal example from the old “Tom Swift” boys’ books: “‘We must run,’ exclaimed Tom swiftly.”

They were turned into a silly game in the 1960s, promoted by Time Magazine, which invited the public to submit outrageous Tom Swifties like:

“Careful with that chainsaw,” Tom said offhandedly.

“I might as well be dead,” Tom croaked.

So we don’t want to go there by accident. Bad dialogue tags may have crept into your consciousness at an early age from those Tom Swift, Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys books. The books were great fun—I adored them myself—but they were written by a stable of underpaid hacks and although the characters are classic, the prose is not.

“Said” is invisible to the reader. Almost any other dialogue tag draws attention to itself.

Very often the tag can be eliminated entirely. This allows your characters to speak and THEN act, rather than doing the two simultaneously.

Not so swift:

“We must run,” exclaimed Tom swiftly.

Better, but awkward.”We must run!” said Tom, sprinting ahead.”Best:

“We must run!” Tom sprinted ahead.

7) Mary Sues

A Mary Sue is a character who’s a stand-in for the writer’s idealized self, which makes the story a wish-fulfillment fantasy for the author, but a snooze for the reader.

Mary Sue is beautiful. Everybody loves her. She always saves the day. She has no faults. Except she’s boring and completely unbelievable. For more on this, check out the post on Mary Sue and her little friends I wrote last month.

8) Imprecise word usage and incorrect spelling and grammar

Unfortunately, agents and the buying public aren’t your third grade teacher; they won’t give you a gold star just to boost your self-esteem.

Spelling and grammar count. Words are your tools.

If you don’t know the difference between lie and lay or aesthetic and ascetic and you like to sprinkle apostrophes willy-nilly amongst the letters, make sure you find somebody who’s got that stuff under control before you self-publish or send off your ms. to an agent.

Nobody is going to “give you a break” because it’s your first novel. Practice novels belong in a drawer, not the marketplace. If people are spending their money and time on your book, they deserve to have a professional product.

Electronic grammar checks can only do so much. And they’re often wrong. Buy a grammar book. Take an online course. Not everybody was a good student in elementary school, but you’ll need to brush up on your skills if this is going to be your profession. Even a good editor can’t do everything.

9) Clichéd openings

People who read a lot (like agents and editors) have seen some things so often they immediately get turned off. Even if it’s a perfectly good idea. The problem comes when a whole bunch of people have had the same good idea before you.

The most common is the “alarm clock” opening—your protagonist waking up—the favorite cliché of all beginning storytellers, whether short story, novel, or script. There’s a hilarious video on this from the comedians at Script Cops They say, “78 % of all student films start with an alarm clock going off.”

Here are some other openers too many writers have done already:

Weather reports: it’s fine to give us a sketch of the setting, but not more than a sentence or two.

Trains, planes and automobiles: if your character is en route and musing about where he’s been and where he’s going, you’re not into your story yet. Jump ahead to where the story really starts.

Funerals: a huge number of manuscripts—especially memoirs—start with the protagonist in a state of bereavement. If you use this opening, make sure you’ve got a fresh take.

Dreams: we’re plunged into the middle of a rip-roaring scene, only to find out on page five that it’s only a dream. Readers feel cheated.

“If only I’d known…” or “If I hadn’t been…” starting with the conditional perfect seems so clever—I used to love this one—but unfortunately a lot of other writers do too.

Personal introductions: starting with “my name is…” has been overdone, especially in YA.

Group activities: don’t overwhelm your reader with too many characters right off the bat.

Internal monologue: don’t muse. Bring in backstory later.

The protagonist looking in the mirror describing herself: In fact, you don’t need as much physical description of the characters as you think. Just give us one or two strong characteristics that set them apart. Let the reader’s imagination fill in the blanks.

Too much action: Yes, the experts keep telling us to start with a bang. But if too much banging is going on before we get to know the characters, readers won’t care.

If you use one of these openers in an especially clever and original way, you may get away with it. But be aware they are red flags, and many people won’t go on to find out what a great story you have to tell.

For more on this, Jami Gold has a great post this week on how to avoid cliches in your opener.

10) Wordiness

There’s a reason agents and publishers are wary of long books. New writers tend to take 100 words to say what seasoned writers can say in 10. If your prose is weighty with adjectives and adverbs or clogged with details and repetitive scenes, you’ll turn off readers as well.

Remember a novel is a kind of contract between writer and reader. If you are writing to fulfill your own needs, not those of the reader, you’re breaking that contract. They’ll feel cheated. And they will probably let you know.

If you’re still doing any of these things, RELAX! Enjoy writing for its own sake a while longer. Read more books on craft. Build inventory. You really do need at least two manuscripts in the hopper before you launch your career.And hey, you don’t have to become a marketer just yet. Isn’t that good news?

For more on this, Sarah Allen has a great post this week on Top 7 Mistakes that Make Your Writing Look Unprofessional.

How about you, scriveners? What mistakes did you make when you were starting out? As a reader, what amateurish red flags make you start to feel nervous about buying a book?

posted by Anne R. Allen (@annerallen) September 21, 2014

March 11, 2018

Blog Tour for Charles F. French and His New Release, Gallows Hill, A Review

[image error]Gallows Hill, by author, Charles F. French, is the second book in his series, The Investigative Paranormal Society. Within this taunt, terrifying, page-turner, we find Roosevelt, Jeremy, Helen, and Sam continuing to pursue ghostly evil and new revelations about a heart-breaking past event, that complicates an already murderous ghost assignment that the IPS needs to vanquish before more innocent lives are lost.

Adding to the taunt, terrifying ghost encounter, is a back-story vendetta out to destroy Sam, a retired police detective, and anyone else in proximity to Sam. Beyond the uniquely horrific ghost mystery, is a heart-breaking love story, as well as a long-lost love rediscovered, that adds to the emotional complexity that drives this story forward.

The character development within this ghostly horror novel is superb and adds to a narrative that is taunt with tension and suspense. The dialogue is not shy and gives a realistic representation of language, idioms, and images within the back-story to the present day, that reflects the different characters’ prerogatives and state of mind. The physical environment presented in this horror novel, is tangible, adding to the realism, terror, and fear in Gallows Hill.

Anyone who loves, not only a terrific horror story, but also one that is expertly written with a strong human story, heartbreak, and a love story, wrapped up in terror and courage to face what could be a death sentence, this story is for you. Don’t miss out on reading Gallows Hill, you won’t be disappointed. I highly recommend this intriguing horror novel. I give it 5 stars!

*****5 stars*****

The Seven Ravens: a Tale for International Women’s #FolkloreThursday by Author, A. M. Offenwanger

In this wonderful story, presented by author, A. M. Offenwanger, for International Women’s Day, The Seven Ravens reveals how a young girl saves her brothers – no damsel in distress was she, and the age old warning, “be careful what you wish for”.

I love fairy tales, discussions about fairy tales and writers who write fairy tales. I believe that fairy tales, in many regards, are a litmus test for how a society is behaving. It is a form of free speech, disguised as a fairy tale when free speech is limited in many societies. Fairy tales often describe what is noble in the human spirit, that doing the right thing often brings its own rewards, and how the down-trodden can fight for their human dignity. Elements of fairy tale like stories, in the modern era, are found in all genres of fiction. Fairy tales, in my opinion, were never meant just for children, they often were meant for a society, like the Little Match Girl and Little Red Riding Hood, the age old good vs evil, yes, but much more than that, it was a way to change hearts and minds, a way to build character and a conscience.

It’s International Women’s Day today. It’s also Thursday, which invariably generates a flurry of Twitter posts under the hashtag #FolkloreThursday. So, of course, today a fairy tale nerd’s Twitter feed is awash in tweets about women in folklore.

“Ah, women in fairy tales,” you say, “damsels in distress, passively waiting for a prince to come rescue them – right?” Bwhahahahah! Excuse me while I laugh loud and long (not to mention a little scornfully). Yes, sure, they exist, the Sleeping Beauties and Snow Whites in their glass coffins or rose-covered castles (and we love ’em). But just as common are the wide-awake Beauties who are the ones that do the rescuing – of Beasts or Frogs, for example, to mention just two of the best-known tales. And not all of those tales’ happy endings are weddings, either – there are people other than lovers or boyfriends to rescue, you know.

View original post 1,834 more words