Theresa Smith's Blog, page 78

April 16, 2020

The Isolation Lucky Dip Reading List by @TheresaSmithWrites

I’ve never been one for reading to lists but I recently saw a post somewhere (could be Twitter, Facebook or on my WordPress reader) about a list of books to read while in isolation. I honestly don’t need a list – there are, without exaggeration, hundreds of books here in my house just waiting to be read. But I didn’t click on the link when I saw this post as I was in a bit of a hurry, and now I can’t find it. Searching for it led me down a bit of a list rabbit hole and after reading countless best books of all time and books to read before you die lists, I decided to make my own.

Many of these lists just keep banging on about the same old classics, many of which I’ve read, and whole lot of which I don’t want to. But I wanted something more contemporary. Again, these lists contain many books I’ve already read along with some that I’d be quite content to die without having ever read. So, with a paper and pen by my side, I have come up with my own list of twenty books, a kind of pick a mix from the many lists I combed over with dissatisfaction. Any more than twenty books would likely see me ignoring it.

1. All that I Am by Anna Funder

2. Atonement by Ian Mc Ewan

3. The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd

4. Daughter of Fortune by Isabel Allende

5. Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

6. Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie

7. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

8. Beloved by Toni Morrison

9. The Secret History by Donna Tartt

10. 100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

11. Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kinsolver

12. The Color Purple by Alice Walker

13. The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern

14. Birds Without Wings by Louis de Bernieres

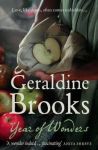

15. Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks

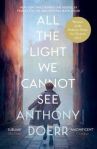

16. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

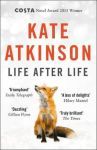

17. Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

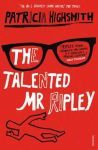

18. The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith

19. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

20. The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell

April 15, 2020

Author Talks: Tony Park on Getting the Research ‘Right’

[image error]

One of the most enjoyable and challenging things about starting a new novel is learning about something you know absolutely nothing about.

My next novel, Last Survivor, is, like many of my previous books, based on the fight against poaching in Africa. The difference in this book, however, is that instead of focussing on mega-fauna, such as rhinos or elephants, I’ve tackled something I’d never heard of until recently – the trade in endangered plants.

Research is the friend and foe of the novel writer. Get it ‘right’ and your fiction will ring true – even to people who know what you’re writing about; but get it wrong and you’ll totally undermine your credibility among knowledgeable readers.

I’ve learned a few tricks about research over the course of writing my novels, mostly by making every mistake a rookie author can possibly make, and I’d like to share what works for me.

Firstly, I use the internet to stalk people, not to find facts. In the past I’ve made the mistake of trawling the net to find ‘proof’ of a fact that I need in my manuscript. As well as a lot of factual information, there is also a lot of BS online. It’s easy to find what you want, but it may be wrong (that’s happened to me).

Instead, I used the internet, when writing this book, to find experts who knew about Cycads, the subject of my story. A cycad is a plant that looks a bit like a stubby palm tree with overly long spikey leaves. In fact, its closest relative is a connifer, and they even produce cones, like pinecones.

The southern African Encephalartos family of cycads are the most endangered living organisms on the planet. Some species are now extinct in the wild, thanks to the passion of devoted cycad collectors and the greed of the people who steal them from their natural habitat and sell them – for huge amounts of money.

I used the internet to track down a professor of botany and a retired special investigator from the US Department of Fish and Wildlife. My investigator, Ken McCloud, ran a two-year, multi-national undercover operation several years ago that brought down an international ring of cycad smugglers.

These people, rather than books or webpages, became my prime source of research.

The second trick I’ve learned about research is to do it in reverse. I do my detailed research retrospectively – that is, after I’ve finished at least the first or second draft of my manuscript.

[image error]

I make my books up as I go along – I don’t have a plot – so there’s no point doing too much research before I start writing. Rather, I write my first draft, letting it flow, and if I don’t know something I just write ‘check’ in the manuscript. After I do my first edit, if I still need that piece of information (sometimes I don’t), I go looking for it.

Having made contact with my experts, I can now approach them with a specific list of questions that relate to the missing pieces of information in my manuscript – that saves their time and mine.

The third tip is to ask your experts to read your manuscript. If you’re reading a novel and the writer has touched on something you know about, then errors will leap off the page at you. By getting my experts to read the whole story they often pick up on incorrect assumptions I’ve made (and, of course, other typos or errors I might also have made).

And finally, when it comes to research, less is more. One of my earlier novels, African Sky, is set on a Second World War pilot training base in Africa. I love aeroplanes and was interested in the period, so I went to town on the research. I let my own interest clutter the story with too much detail and my editor cut back about 60 per cent of the historical information I had jammed into the story.

As the bestselling thriller writer Stephen King says in ‘On Writing, A Memoir of the Craft’ (in my opinion the best book ever written on how to write fiction), when it comes to description “a few well-chosen details will stand for the rest” and so it is with research.

The trick, for me, in Last Survivor was to just provide enough information on cycads – and the type of people who collect them – to make it believable. My aim was to have people who know about plants convinced that I knew what I was talking about, and to provide enough information to enlighten people like me – who know nothing about cycads – but not bore them. I hope I achieved that.

That’s not to say that research can’t be fun. During a trip to London, while writing ‘Last Survivor’ I made a visit to the Kew Botanical Gardens and checked out the rarest cycad in the world, Encephalartos woodii, which became extinct in the wild more than 100 years ago.

Cycads need a male plant and a female to reproduce naturally and the only E. woodiis left in existence, in collections, are all males. The premise of ‘Last Survivor’ is that a long-lost female woodii is discovered – a plant that wealthy collectors would pay a king’s ransom to own.

Terrorists want the plant to fund a spectacular attack and the only people who can stop them are middle-aged former mercenary Sonja Kurtz and a team of heavily armed elderly plant fanciers called The Pretoria Cycad and Firearms Appreciation Society.

I hope you enjoy ‘Last Survivor’ and learn something about the trade in endangered plants – but not too much!

Last Survivor

[image error]

Greed.

Joanne Flack is on the run – suspected of stealing a rare African plant thought to be extinct and worth millions of dollars.

Danger.

Sonja Kurtz is hired by the CIA to hunt down Joanne and find the link between the missing plant and a terrorist group hiding out in South Africa.

Treachery.

Joanne is a member of the Pretoria Cycad and Firearms Appreciation Society who take it upon themselves to track down the plant … and the traitor in their midst who is willing to kill for it.

Published by Pan Macmillan Australia

Released 30th June 2020

About the Author:

Tony Park is the author of 17 thrillers set in Africa. His 18th novel, Last Survivor, due for release June 30, delves into the little known, but lucrative world of international plant smuggling. As Tony’s research discovered, there are unscrupulous plant-fanciers making a fortune out of smuggling African cycads – rare plants dating back to the Jurassic era – to greedy collectors worldwide.

There’s more about Tony at www.tonypark.net or on your social media platform of choice as tonyparkauthor

[image error]

April 14, 2020

Book Review: Liberation by Imogen Kealey

About the Book:

The must-read thriller inspired by the true story of Nancy Wake, the most decorated servicewoman of the Second World War, soon to be a major blockbuster film.

To the Allies she was a fearless freedom fighter, special operations super spy, a woman ahead of her time. To the Gestapo she was a ghost, a shadow, the most wanted person in the world with a five-million Franc bounty on her head.

Her name was Nancy Wake.

Now, for the first time, the roots of her legend are told in a thriller about one woman’s incredible quest to save the man she loves, turn the tide of the war, and take brutal revenge on those who have wronged her.

My Thoughts:

I had such high hopes for this novel but after only a few chapters, it was apparent these hopes were to be well and truly dashed. The novel reads like the ‘Hollywood Blockbuster’ it is promoted as becoming. All action, crass conversation, an overabundance of swearing and lewd intention, with little to no depth of feeling.

The French men are depicted as animals and Nancy herself appears as a cross between Wonder Woman and Jessica Rabbit. As an ode to Nancy Wake, a truly inspirational and brave woman, this is a woeful attempt and a bitter pill to swallow.

The only redemption offered is within the historical note at the end where the authors outline Nancy’s true actions against those they embellished and invented. It is my hope that readers interested in the life of this remarkable woman may seek out further reading in order to garner a much clearer and less debased and sensationalised view of Nancy Wake.

Thanks is extended to Hachette Australia for providing me with a review copy of Liberation.

About the Author:

‘Imogen Kealey’ is a pseudonym for Darby Kealey and Imogen Robertson.

Darby Kealey is a writer and producer, based in Los Angeles. His credits include the critically acclaimed series Patriot for Amazon, as well as a number of film and television projects currently in development. His feature script Liberation was nominated to the 2017 Blacklist. He has an MFA in Screenwriting from UCLA, and a BA in Politics from UC Santa Cruz.

Imogen Robertson is a writer of historical fiction. Now based in London, she was born and brought up in Darlington and read Russian and German at Cambridge. Before becoming a writer, she directed for TV, film, and radio. She is the author several novels, including the Crowther and Westerman series. Imogen has been shortlisted for the CWA Historical Dagger three times (2011, 2013 and 2014), as well as for the prestigious Dagger in the Library. She has also written King of Kings, a collaboration with the legendary international bestseller Wilbur Smith.

[image error]

Liberation

Published by Sphere

Released 31st March 2020

Book Review: The Yellow Bird Sings by Jennifer Rosner

About the Book:

Poland, 1941. After the Jews in their town are rounded up, Róza and her five-year-old daughter, Shira, spend day and night hidden in a farmer’s barn. Forbidden from making a sound, only the yellow bird from her mother’s stories can sing the melodies Shira composes in her head.

Róza does all she can to take care of Shira and shield her from the horrors of the outside world. They play silent games and invent their own sign language. But then the day comes when their haven is no longer safe, and Róza must face an impossible choice: whether to keep her daughter close by her side, or give her the chance to survive by letting her go . . .

The Yellow Bird Sings is a powerfully gripping and deeply moving novel about the unbreakable bond between parent and child and the triumph of humanity and hope in even the darkest circumstances.

My Thoughts:

Fair warning: I’m sharing more quotes than usual with this one, because once again, I have been almost struck dumb by the beauty and brilliance of a novel. Isn’t it remarkable how the right combination of words strung together to articulate a certain story can have such a profound effect on some people? As you’ll now be familiar with from previous reviews, music reaches me at a whole other level when blended with literature. And so it is with The Yellow Bird Sings, a novel so achingly beautiful that it managed to destroy me while lifting my heart, the story sinking deep within, so much so, it’s taken me days to get my thoughts together for this review. They still might not be all too coherent, but I’ll give it a shot.

As we all live out our days within our own house and yard, venturing out only when necessary, many of us are feeling the walls closing in around us, an urge to do things we can’t, to visit places that are closed (not me, but I am seeing evidence of this on my social media and within my own house). Imagine though, that instead of having to stay in your own little patch of suburbia, you and your five year old child were instead contained to the loft of a barn, forced to hide under mounds of hay for hours on end, speaking only in whispers, eating, sleeping, relieving yourself, passing 24 hours, 7 days a week, in a small loft. No exercise. No entertainment. Only fear and mercy from those hiding you. Not for a day, a week, or even a month, but for more than a year. Four hundred and sixty odd days of this.

‘As soon as they spot her, the children swarm her at once and stare. Zosia shifts soundlessly from foot to foot, unaccustomed to being looked at. A lone girl greets her with “Hallo,” but Zosia’s voice chokes. Words, to Zosia, are like glass beads around her neck. If one were to break loose, they would all clatter to the floor and scatter, shatter the quiet that kept her and her mother alive, entwined beneath hay.’

That’s only the first part of this novel though, and as remarkable as it is, it just moves to a new level of remarkable once mother and daughter are no longer in hiding in the barn. This is a story of absolute endurance and survival, about making connections and alliances in an effort to save your life so that you can in turn save the life of the one you love; the only one you have left. The story splits about a third of the way in, and we then follow the separate journeys that Róza and her daughter are forced to take, further and further apart, connected by an invisible chain of daisies and a metaphorical little yellow bird that sings. There is no glamour in this story and the heroics are more of the quiet sort performed by people who allow morals and conscience to weigh greater than fear. Likewise, the prose is spare and to the point, although infused with a lyrical quality that makes it both easy to read and heartbreaking to decipher. The story itself is awe inspiring, based more on the collective war experiences of many, than just on one person.

‘All three of them are stained with dirt, their hair matted and itchy from lice, their faces sunken and gaunt, their lips swollen and cracking. As mirrors for one another, they offer no comfort. But the focus is on movement and on food. The thaw coaxes new shoots from the ground and new buds on plants that can be eaten. Their boots leave tracks in the mud. Each tries what she can to prevent it: Chana wears a pair of socks over her boots; Róża alters her stride in an effort to obscure the pattern and even walks on all fours at times. Since the soles of Miri’s boots have detached completely, she ties them on backward so that her tracks point in the opposite direction.’

So, where is the music? The music is in everything. Róza comes from a family of musicians, her father was a violin maker, she a cellist, her husband a violinist. Her daughter, at five, is a prodigy, something Róza only begins to get an inkling of before they are separated. Shira, for all the trauma she has had to endure in such a short space of time, locks much of herself away, but music is the one thing that she can’t block out. She has the fortune of being hidden in a convent, and this is where we see another group of heroes, vulnerable women protecting children from Nazis, all over Europe. It’s not all roses there, of course not, but if you keep the situation within context, the fear these nuns must have constantly felt, the responsibility for the safety of the children they bore. That manifested itself in many ways: cruelty in some, protectiveness in others, kindness in most. It is within this convent that Shira’s musical talent is unleashed.

‘A loud burst of real singing interrupts Zosia’s reverie. She twists around to see a group of nuns standing in two lines at the back of the church. Zosia doesn’t know the language of the song, but her heart delights at the joyous interweaving of voices, some deep and resonant, others high and bell-like. She stops crying and sits up. The sound is miraculous, like the broke-open sky— the sky they sat under, she and her mother, in the hills and the pastures, before all the walking stopped. Before the rafters and roofs trapped them in. Before her mother sent her away.’

You may have noticed from the quotes that Shira is not mentioned, but rather, they are about someone named Zosia. Zosia is Shira. And so is Tzofia. From the moment Shira leaves her mother, she becomes one of the displaced children of Israel. Her identity changed too many times for her to be traced. The loss for both her and her mother is profoundly affecting to read about and contemplate, for of course, this story takes its bones from history itself. From about halfway through until the end, I listened to classical music while reading, an album of string orchestra pieces. The experience of reading this story about a child surviving exile through music while listening to what I deemed as similar music was so incredibly moving, I can’t even describe to you how it made me feel.

‘Zosia loves the dramatic start! As she plays, she imagines costumed dancers circling one another, arms hooked, their eyes sparking with each playful pluck of strings. Zosia pulls her bow its full length, back and forth. When the music slows, briefly languid, she imagines the embrace; then speeding up, the flight of feet, raised arms , and twirling skirts; and on an extended note, long and trilling, her bird flitting above the dance, excited and happy.’

~~~

‘Tuning her violin hastily, she quarter turns, hardly noticeable, to avoid directly facing the soldiers and the children seated behind them. She puts bow to string to start— her arm steady despite how nervous she feels inside— and plays, the guiding rhythm a Romani march, soft and introspective. In her mind, her bird, solitary, restless, seeks out a resting place in the icy branches of a tree. His warbling notes reverberate in the night sky like a call and response: Are you there? Yes, I am here. Where? Right here. Settle yourself. Settle. A long, rising note, barely audible, ends the middle sections— a gloomy place to stop. Zosia takes a chance and continues, playing the final movement: upbeat and rousing, a showpiece. As she keeps watch on the intricate fingering and bowing, she really performs now, angling outward to the audience, aware of the sound echoing in the room, escalating , frenzied, and exciting. The last measures push Zosia, and she rises to their challenge with the quickest of strokes and wild plucking. She feels expansive as never before, legs rooted, bow-arm flying, her fingers dancing between the strings. She closes her eyes. The music soars beyond her own sensibilities, into the listening crowd. She finishes with a strong, dramatic bow stroke.’

~~~

‘Maybe Tzofia would never be one for words. But horsehair on string, bow-arm at just the right angle , with her violin, all that Tzofia holds inside floats out of her in long, even strokes. Rather than the mass of her own body, rather than words, choked and dry, it is the heft of the violin upon her shoulder, the smooth rest for her chin, the steady pressure demanded of her hand on the bow, that roots Tzofia in the world.’

This novel has one of the most incredible endings. Hard fought for, a long time coming, and a testimony to the power of music: the way it can reach out across time and experiences and connect two people who had given each other up as forever lost. The Yellow Bird Sings is one of those novels where you mourn at the end because you can’t ever experience it for the first time again.

Thanks is extended to Pan Macmillan Australia for providing me with a copy via NetGalley of The Yellow Bird Sings for review.

About the Author:

The Yellow Bird Sings is Jennifer Rosner’s debut novel. She is the author of the memoir If A Tree Falls: A Family’s Quest to Hear and Be Heard, and the children’s book, The Mitten String. Her writing has appeared in a wide variety of newspapers and magazines. Jennifer lives in western Massachusetts with her family.

[image error]

The Yellow Bird Sings

Published by Picador

Released 25th February 2020

April 13, 2020

Book Review: Gulliver’s Wife by Lauren Chater

Book Review:

Birth. Death. Wonder … One woman’s journey to the edge of love and loyalty from the bestselling author of The Lace Weaver

London, 1702. When her husband is lost at sea, Mary Burton Gulliver, midwife and herbalist, is forced to rebuild her life without him. But three years later when Lemuel Gulliver is brought home, fevered and communicating only in riddles, her ordered world is turned upside down.

In a climate of desperate poverty and violence, Mary is caught in a crossfire of suspicion and fear driven by her husband’s outlandish claims, and it is up to her to navigate a passage to safety for herself and her daughter, and the vulnerable women in her care.

When a fellow sailor, a dangerous man with nothing to lose, appears to hold sway over her husband, Mary’s world descends deeper into chaos, and she must set out on her own journey to discover the truth of Gulliver’s travels . . . and the landscape of her own heart.

My Thoughts:

Lauren Chater, author of The Lace Weaver (a personal favourite of mine), has returned with a new historical fiction release, Gulliver’s Wife. In a sort of fan-fiction type of mash up, Lauren has breathed life into a character that didn’t get much airtime in the original classic, Gulliver’s Travels: Mary Gulliver, wife of the main character, Lemuel Gulliver.

‘The decision to set my own novel between the first and second of Gulliver’s journeys was driven by the desire to condense the action and highlight the drama around his possible madness and the impact it might have on his wife’s life.’ – Author note.

Innovative and unique, this novel was gripping from the very first page. It’s very much a character driven narrative, there is certainly a lot happening within the story, but for me, it was the character responses to these events that took centre stage rather than the events themselves. Eighteenth century London was not a safe place, particularly for women and children. I feel this period of history is not as touched upon within fiction as often as the 17th and 19th centuries are. It was a grim time, crime and disease running rife, child labour laws still non-existent, women and children considered as the property of their husbands and fathers. Lauren Chater has done her research in the crafting of this novel and it shows within the meticulous details and the manner in which she’s recreated this entire world with such authenticity. More often than not this is a dark and confronting story, but that’s the way I like my historical fiction, and that’s also the way in which this novel sets itself so firmly within its chosen era.

Gulliver’s Wife is very much a story of female agency and it’s a magnificent ode to midwifery. Instead of trying to paraphrase, I’ll once again share Lauren’s own words:

‘Contrary to stereotypes (reinforced by male practitioners) that the London midwives were ‘ignorant, incompetent, and poor’, they commanded immense respect within their close-knit communities and their commitment to the role, which included apprenticeships, licensing and oath-taking, meant they were often viewed as experts in the ‘secret women’s business’ of childbirth. They also testified against criminals accused of rape and sexual assault and were considered ‘expert witnesses’ by the courts, since their work required extensive knowledge of female anatomy. Not everyone approved. In the early 1700s, a movement aimed at discrediting female midwives to promote the interests of male practitioners began to gain momentum, supported by surgeons who favoured the medicalisation of birth via forceps and ‘lying-in’ hospitals which eventually led to devastatingly high mortality rates in the latter half of the 18th century.’ – Author note.

Enter Mary Gulliver, who I adored from the outset. Like a shining beacon of hope, she tended to the women of her section in London, and sometimes further into other neighbourhoods, juggling home and work in a time when there was no respect to be had for doing so. She was far from perfect, and she definitely dropped a few balls from time to time, but she was real, so genuine and a character I became deeply invested in. I felt so much sympathy for her, being married to Lemuel, who really was an arrogant arse, among other things. Life was not easy for Mary, but she remained selfless and steadfast. Her relationship with her housemaid, Alice, was a particular drawcard for me and I enjoyed the sections where this was highlighted. As ever, the botany aspects caught my attention the most. It’s an interest I can’t seem to shake.

‘This garden is her private sanctuary, the symmetry and geometry of the plants and trees designed to foster a deep, contemplative sense of calm. The herbs and flowers in their beds are the descendants of the seeds her mother passed on to her. Perhaps it is almost pagan to indulge in such earthly pleasure but each plant in her garden has its pleasing purpose: medicinal, gourmand, ornamental. Nothing is wasted and everything has its place. Even the bees have their role to play, always pausing first at the hollyhocks before they move on to the woodruff, some elemental compulsion propelling them from flower to flower. The ants consume the garden’s dead waste, chomping through old branches and litter, stripping leaves down to their skeletal core while in the cool darkness beneath the topsoil, the earthworms dance.’

Now, this story is not just about Mary. It’s also about Bess, her fourteen-year-old daughter. I really struggled with Bess, right alongside Mary, but I have a suspicion that may have been the intended response. Spoiled, naive, selfish, and most irritating of all, the misplaced hero worship she displayed towards her father. She constantly put herself at risk, caused Alice and her mother no end of distress and worry. As much as I found her intolerable, I am filled with admiration for Lauren’s authentic rendering of a headstrong teenager within such a setting. It was also a risk, to create a character such as Bess, one who just didn’t know when to stop pushing her luck, for not every reader would develop empathy over impatience for the girl – I certainly didn’t. And yet, I still loved this novel. Bess was indeed fortunate, more than she was capable of realising, to have a mother such as Mary. Her future could have been vastly different – a whole lot worse off. And as insufferable as Bess was, her presence within the story and all of the trials and petty nonsense that she brought to the table just further displays Lauren Chater’s skill as a writer. In less competent hands, a contrary character like Bess may have given me cause to abandon a novel – I have too much lived experience of teenage dramatics and egotism to want to escape into it by choice through literature!

‘This is the beating heart of London – of life, really. Men like her father are the lynchpin on which the world turns. Without them, everything will grind to a shuddering halt. They are like the Titans Pa told her about, like Cronus or Hyperion or mighty Oceanus, gods of sea and of land. Mam and her friends consider their midwife’s work indispensable but Bess knows it is men like Pa who ensure London’s children have a future. Men keep them all afloat.’

~~~

‘Her mother was just a worrier who liked to flaunt her authority whenever he was away. Bess had enjoyed watching Mam grow flustered as Pa ordered her about. She loved to watch her pa scoop handfuls of coins and traders’ tokens out of the teapot in the parlour while Mam was at work. The china teapot had belonged to Mam’s mother, Bess’s grandmother. It was one of the only things Mam owned which had belonged to her and Mam kept it filled with farthings and pennies for emergencies only. Not that the notion ever stopped her father. Munching on a pilfered shortcake, Bess had watched with glee as her father breathed new life into their stale existences and upended her mother’s carefully ordered world.’

Gulliver’s Wife is a literary achievement, a smorgasbord of delight for fans of historical fiction. I know we’re in for a bit of a wait, but if this is the standard we can expect from Lauren Chater, I honestly can’t wait until her next release.

‘Love takes strange forms. Sometimes it is a pebble, hard and unyielding, at other times a willow birch, bending to accommodate the headlong rush of water in a stream.’

Thanks is extended to Simon & Schuster for providing me with a copy via NetGalley of Gulliver’s Wife for review.

About the Author:

Lauren Chater is the author of the bestselling historical novel The Lace Weaver and the baking compendium Well Read Cookies: Beautiful biscuits inspired by great literature. She is currently working on her third novel, The Winter Dress, inspired by a real 17th century gown found off the Dutch coast in 2014. In her spare time, she loves baking and listening to her children tell their own stories. She lives in Sydney.

For more Lauren, see:

www.laurenchater.com

www.thewellreadcookie.com

www.instagram.com/the_well_read_cookie

www.facebook.com/LaurenChaterWriter

www.twitter.com/WellReadCookie

[image error]

Gulliver’s Wife

Published by Simon & Schuster Australia Released April 1st 2020

April 12, 2020

Book Review: Stone Sky Gold Mountain by Mirandi Riwoe

About the Book:

Set during the gold-rush era in Australia, this remarkable novel is full of unforgettable characters and deals with timeless questions of identity and belonging.

Family circumstances force siblings Ying and Lai Yue to flee their home in China to seek their fortunes in Australia. Life on the gold fields is hard, and they soon abandon the diggings and head to nearby Maytown. Once there, Lai Yue gets a job as a carrier on an overland expedition, while Ying finds work in a local store and strikes up a friendship with Meriem, a young white woman with her own troubled past. When a serious crime is committed, suspicion falls on all those who are considered outsiders.

Evoking the rich, unfolding tapestry of Australian life in the late nineteenth century, Stone Sky Gold Mountain is a heartbreaking and universal story about the exiled and displaced, about those who encounter discrimination yet yearn for acceptance.

My Thoughts:

Stone Sky Gold Mountain is an unforgettable story, gentle in its brutality as it inches closer to its tragic inevitability. It is a study of prejudice, displacement, racism, and misogyny. You really didn’t want to be anything other than a white man in 19th century Australia.

It is so beautifully written, evocative and lyrical, yet entirely easy to slip into and get lost in.

‘And in the dim hut, his thoughts shatter like porcelain – crumbling fragments of confusion, shards of lucidity. The pieces shift and tremble in the cavity of his skull. Some come together, neat, with only tell-tale fissures in the glaze, but mostly they float in the air, broken.’

Deeply atmospheric, the setting and era is conjured through the narrative vividly and consistently. There is no mistaking the location within this novel, and anyone who has lived in central and north Queensland will relate to the sense of cloying and oppressive heat that lifts from the pages of this story; the depiction of the unrelenting buzz of flies and the aggressive way they pursue you in a bid to locate the slightest bit of moisture. I can’t even begin to comprehend, from my air-conditioned and fully screened house, how unbelievably hard it would have been to live each day with no reprieve from the elements.

‘She stirs her soup, closing her eyes to banish thoughts of grey-shirt. She doesn’t want her enjoyment of the meal to be tarnished. She carries her stool outside and settles down to watch the last of the sun sink beyond a rise of grass as dry as wheat, punctuated by clumps of bright green foliage. Before eating, though, she sifts the soup for flies that might have fallen into its depths, stunned by its heady steam; searches for tell-tale wings or the crooked leg of a roach. Thinking of how her mother would scold her for being so fussy. She gulps down five burning mouthfuls before looking up again.’

There is so much sadness and injustice throughout this novel but it bears this weight lightly. It’s a truthful read, but not a depressing one. Literary historical fiction is my absolute favourite to read, so I feel as though this novel was, for me, made to measure. Needless to say, I highly recommend it and hope to see it listed for future literary prizes.

‘Sunset casts its dreary gloom through the doorway, lingering over their meagre belongings, before slowly withdrawing, inch by dark inch until Meriem lights the two lamps.’

Thanks is extended to UQP for providing me with a copy of Stone Sky Gold Mountain for review.

About the Author:

Mirandi Riwoe is the author of the novella The Fish Girl, which won Seizure’s Viva la Novella V and was shortlisted for the Stella Prize and the Queensland Literary Award’s UQ Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in Best Australian Stories, Meanjin, Review of Australian Fiction, Griffith Review and Best Summer Stories. Mirandi has a PhD in Creative Writing and Literary Studies and lives in Brisbane.

[image error]

Stone Sky Gold Mountain

Published by UQP

A$29.99 (Paperback)

Released 31st March 2020

April 10, 2020

#BookBingo2020 – Round 4: Friendship, Family and Love

[image error]

An Almost Perfect Holiday truly hit all the right notes for me. It’s an absolutely perfect read if you’re looking for a novel that has a little bit of everything: humour, romance, drama, family issues, personal growth, mystery, friendship, grief, and love.

Visit my full review on this book here.

[image error]

I’ve teamed up once again with Mrs B’s Book Reviews and The Book Muse. It’s going to be a little different for 2020, the card has less squares, allowing us to run bingo on the second Saturday of each month. Also, for the first time since beginning bingo, I haven’t specified genre, type, or even fiction or non-fiction for the categories. 2020 is all about themes, and from there, the choice is wide open.

Hope to see you joining in! If you want to play along, just tag us on social media with your bingo posts each month. You can also join the Page by Page Book Club with Theresa Smith Writes over on Facebook, where we all post in the same place on the same date and chat over each other’s entries. Alternatively, drop a link each month into the comments of my Saturday bingo post so I can follow your progress blog to blog.

#BookBingo2020

April 9, 2020

The Week That Was…

Easter. As we’ve never previously known it, but at least there is still chocolate and plenty of time for quiet contemplation while eating prawns and drinking chilled wine.

My joke of the week is Easter themed:

[image error]

Everyone is using zoom these days…

~~~

In passing:

Just to update you all on my oldest son. Tests came back as positive for glandular fever but he’s not doing too bad. The tonsilitis has cleared up but he’s doing a lot of sleeping, which I understand is to be expected. I figure it’s best just to leave him to it, even if his waking and sleeping schedule is a bit topsy turvy.

~~~

Movie of the week:

I needed a break from the real world so I watched this, even though I don’t have young children to use as an excuse for having done so. And it was very good, although, there’s a scene where Elsa belts out a number and the whole combination of song, costume and special effects put me in mind of Eurovision!

[image error]

~~~

I’ve read three

reads in a row this week. That must be some kind of jackpot.

reads in a row this week. That must be some kind of jackpot.

~~~

Until next week…

April 8, 2020

Author Talks: Suzanne Leal on Inspirations for The Deceptions

[image error]

Although landlords are not always loved, mine not only gave me a roof over my head but also my career as a writer. For they told me the stories that inspired both my new novel, The Deceptions, and my first, Border Street.

I was just out of university when I moved from inner city Sydney across to the beachside suburb of Tamarama. The rental property was newly advertised and not expensive. There was one catch: it was a duplex and my boyfriend and I would be sharing with the landlords. It was a small price for the location, I thought, and, competitive by nature, I was determined to beat the other would-be tenants milling around. And I did. I secured the property and for six years, we lived next door to our landlords, Fred and Eva Perger, who were Czech and Jewish and Holocaust survivors.

Fred and I became close, close enough for him to tell me his wartime story, a story that had taken him from the Theresienstadt ghetto outside Prague to Auschwitz and Dachau. In giving me this story, he revealed more to me that he had even to his own family. Perhaps it was less painful to tell a trusted outsider.

And so, for over a year, I spoke to Fred about his life, particularly about his life during the Second World War. These interviews, which I later transcribed, would provide the foundations for my first novel, Border Street.

Among the many stories Fred told me was one that never left me; one that, many years later, after Fred and Eva had both died, would provide the inspiration for my new novel, The Deceptions. It was a story that both fascinated and perturbed me.

This was the story Fred told me.

As teenagers, both he and Eva – together with their families – had been sent to the ghetto of Theresienstadt. The ghetto was overcrowded and there was poor sanitation and inadequate food. Furthermore, the spectre of transportation hovered over the inmates: the SS would determine the number of detainees to be taken, then ask the Jewish Council of Elders within the ghetto to decide who should be chosen. Eva and Fred were more fortunate than many because for they believed themselves protected from transportation. This was because Eva’s father, Dr Franz Fischer, was a doctor whose skills were of great demand in the ghetto. For this reason, he and his family – including Fred – had been promised protection.

The ghetto was guarded by Czech gendarmes who were part police, part military. When one such gendarme broke his arm, Dr Fischer set it for him. To thank him, the gendarme offered to smuggle correspondence out of the ghetto for Dr Fischer and his family. It was an excellent arrangement that might have lasted indefinitely, had the gendarme not been accused of Rassenschande – or race shame – for his illicit relationship with one of the Jewish detainees. The gendarme and the Jewish woman said to be his lover were both arrested. The gendarme’s notebook was also confiscated, in which he had recorded Dr Fischer’s name and details. Soon afterwards, Dr Fischer was taken to the nearby political prison and Fred and Eva were both transported to Auschwitz.

Dr Fischer never returned home. Fred and Eva both survived the war, as did the gendarme. But of the woman who’d been arrested with the gendarme, Fred knew nothing. He’d never even known her name.

This unknown woman haunted me. Who was she? What was the nature of her relationship with the gendarme? And what had been her fate? I needed to know more. But how? I had next to no information and because Fred and Eva were no longer alive, I was on my own. Or so I thought.

Since their parents’ death, I had kept up a friendship with Fred and Eva’s daughters, Helena and Renata, and I told them my problem: I wanted to write the gendarme’s story but I knew nothing about Czech gendarmes and there had been little written about them.

Helena had an idea. She had many non-Jewish Czech friends living in Australia. She would ask them if they knew anything about the Czech gendarmerie and whether they themselves had relatives who had been gendarmes, particularly during the war. She was met with absolute silence. No-one would say a word. For although Fred had liked the gendarme he had come to know, gendarmes who had worked during the war risked being accused of collaboration. So we drew a blank. Any secrets would continue to be closely held. No-one would be coming forward to help me.

Instead, I turned to books and stories. I immersed myself in the memoirs of women who had been sent to the Theresienstadt ghetto and to the concentration camps and I read the work of Arnošt Lustig, who had been sent to the Theresienstadt ghetto as a teenager and who wrote about the gendarme who, upon discovering contraband in an detainee’s pocket, could have reported him to the SS – but didn’t.

In this way, my characters emerged – the strong, arch, dry Hana Lederová and her beguiled guard, Karel Kruta – as I reimagined the story Fred and Eva had told me. And so The Deceptions took shape: a story of love and betrayal and hope and resilience in the tumult of the Second World War. And as our world once again catapults into uncertainty, I hope it is a story that gives heart to its readers.

About the Book:

[image error]

Long-buried family secrets surface in a compelling new novel from the author of The Teacher’s Secret.

Moving from wartime Europe to modern day Australia, The Deceptions is a powerful story of old transgressions, unexpected revelations and the legacy of lives built on lies and deceit.

Prague, 1943. Taken from her home in Prague, Hana Lederova finds herself imprisoned in the Jewish ghetto of Theresienstadt, where she is forced to endure appalling deprivation and the imminent threat of transportation to the east. When she attracts the attention of the Czech gendarme who becomes her guard, Hana reluctantly accepts his advances, hoping for the protection she so desperately needs.

Sydney, 2010. Manipulated into a liaison with her married boss, Tessa knows she needs to end it, but how? Tessa’s grandmother, Irena, also has something to hide. Harkening back to the Second World War, hers is a carefully kept secret that, if revealed, would send shockwaves well beyond her own fractured family.

Inspired by a true story of wartime betrayal, The Deceptions is a searing, compassionate tale of love and duplicity-and family secrets better left buried.

Read my review of The Deceptions here.

Published by Allen & Unwin

Released 31st March 2020

About the Author:

SUZANNE LEAL is the author of The Deceptions, The Teacher’s Secret and Border Street. A regular presenter at literary events and festivals, she was the senior judge for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards from 2017 to 2019 and is a board director of Sydney Crime Writers Festival. A lawyer experienced in child protection, criminal law and refugee law, Suzanne is a senior member of the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal and former member of the Refugee Review Tribunal.

Facebook: suzannelealauthor

Instagram: suzannelealauthor

Twitter: suzanne_leal

www.suzanneleal.com

[image error]

April 6, 2020

Book Review: House of Trelawney by Hannah Rothschild

About the Book:

The seat of the Trelawney family for over 800 years, Trelawney Castle was once the jewel of the Cornish coast. Each successive Earl spent with abandon, turning the house and grounds into a sprawling, extravagant palimpsest of wings, turrets and follies.

But recent generations have been better at spending than making money. Now living in isolated penury, unable to communicate with each other or the rest of the world, the family are running out of options. Three unexpected events will hasten their demise: the sudden appearance of a new relation, an illegitimate, headstrong, beautiful girl; an unscrupulous American hedge fund manager determined to exact revenge; and the crash of 2008.

A love story and social satire set in the parallel and seemingly unconnected worlds of the British aristocracy and high finance, House of Trelawney is also the story of lost and found friendships between three women. One of them will die; another will discover her vocation; and the third will find love.

My Thoughts:

This novel was pure gold class entertainment. Hannah Rothschild takes us into the world of a modern impoverished aristocratic family who are very much living their worst nightmare: there is no money. None. Every parcel of land that could be sold, has been sold. Anything of value inside has also been sold. The rest is crumbling to ruin around them as they live out their days in a castle too large and expensive to run, much less fix and maintain, slowly being reclaimed by nature as the ivy and rodents move in and take hold.

Dripping with satire and speckled with moments of outrage and eccentricity, House of Trelawney examines the ever-changing face of British society. This is an intelligent work of fiction, diving deep into the financial crisis of 2008 and its far-reaching effects for all: the aristocracy through to the working class.

As the family navigate these changing waters, their circumstances are brought to a head by several factors and a few key people intent on quite literally bringing down the house. I am a fan of British humour so for me, this entire novel was pitch perfect. It’s boldly honest, laugh out loud funny, intricately plotted, and peopled with a wholly unique and entertaining cast. Hannah Rothschild is a great writer, achieving a precise and clever balance between scorn and empathy. I really enjoyed House of Trelawney and can highly recommend it.

Thanks is extended to Bloomsbury Publishing for providing me with a copy of House of Trelawney for review.

[image error]

House of Trelawney

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing

Released 18th February 2020