Jason Micheli's Blog, page 85

February 5, 2023

Participating in Providence

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Genesis 28

Five years ago, three years after he should have been no longer alive, the esteemed New Testament scholar, Richard Hays, addressed those who had gathered to celebrate his retirement from Duke Divinity School.

At the top of his lecture, Hays said,

“I’m grateful to all of you who’ve come here this evening to hear a few reflections from me on the occasion of my retirement. I’m grateful for all your prayers over these past three years.”

They worked.

God answered them.

“I’m grateful for all your prayers. Most of all, I’m grateful to God for granting me a little more world and a little more time to think back on what has been and to ponder what is to come. The key note of all I have to say is gratitude. This is the day that the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

This is the day the Lord has made. That’s not a sentiment. It’s a claim.

“Most of you know…three years ago I received a devastating diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and I went on medical leave to undergo chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. When I left the dean’s office that July, I left in tears with my hair falling out. I took up the tasks of reviewing my will and writing directions for my funeral service. As I stand here tonight, I’m unexpectedly able to look back on that night, that year, of now done darkness. Chastened, hopeful, healed. I’m grateful for your prayers.”

A couple of year ago, I was in my truck, driving to the office, when a different Duke professor called me.

Over the years the theologian Stanley Hauerwas has become more than a mentor.

He’d been ill and had undergone surgery in England, and I’d left him a message inquiring about his health and spirit.

That morning on the way to church, he called me back and before I could even say hello, his gravely Texas accent barked out, “Jason I can’t piss, and it’s just so damn painful.”

As I pulled into the church’s parking lot, he described all the complications he’d suffered following what should have been a routine procedure.

I listened.

But I knew that Stanley is not the sort of Christian to be satisfied with a preacher who offers nothing but active listening.

So I said to him, “I’ll pray for you, Stanley.”

“You damn well better do it now,” he grumbled, “I’m miserable, in agony.”

I cleared my throat and was about to begin praying when Stanley interrupted me.

“And Jason?”

“Yes, Stanley?”

“If you’re not going to pray for God to heal me, then, hell, just hang up the phone right now already.”

I laughed and I prayed to God for just that and when I was done he said, “Thank you. I’m grateful for your prayers.”

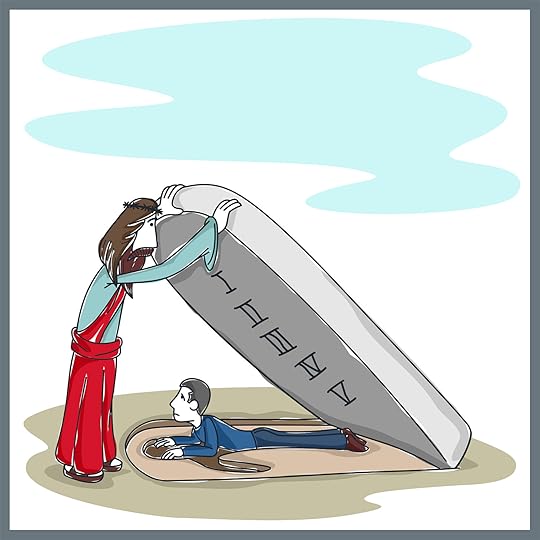

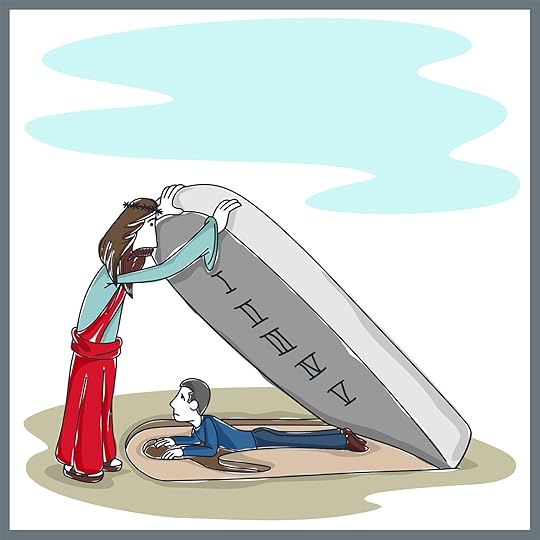

After having dishonored and deceived his father and stolen his elder brother’s blessing, Jacob nevertheless receives a prayer from his father.

“May God Almighty bless you…” Isaac prays, “May God give the blessing of Abraham to you…”

With this prayer in his pocket and a staff in his hand, Jacob sets out for a life in exile on his uncle Laban’s estate. But no sooner has Jacob left his father’s home than God Almighty answers Isaac’s prayer. Jacob makes camp at Bethel, the very place where his grandfather had built an altar and called upon the name of the Lord.

Jacob picks out a stone for his pillow. He lays down to sleep. And he falls in to a dream. Jacob dreams of an earthbound exit off a heavenly highway jammed with angelic traffic. And then, after the dream, God Almighty answers Isaac’s prayer.

God appears to Jacob— for the first time to Jacob— and God says,

“I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac…Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.”

Notice—

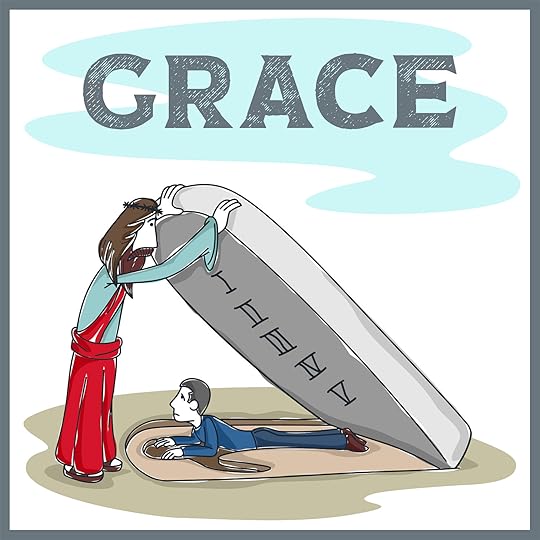

In answering Isaac’s prayer, God says nothing to Jacob about Jacob’s sin, neither his trespass against his brother Esau nor his transgression against his father. It’s all just blessing and grace.

Jacob is addressed by God. Jacob is addressed graciously by God. And God addresses Jacob as a result of Isaac’s prayer for Jacob. No doubt Jacob is grateful for Isaac’s prayer.

Jacob meanwhile responds to the Lord’s address of him by himself praying. Jacob’s prayer at the end of Genesis 28 is a clear indication that we should not expect a person’s religious experience to change their character in any significant manner. The Jacob who prays after having had this mystical encounter with God is the same Jacob who conned a birthright from his brother and stole a blessing from his father. Jacob prays,

“Since you’re going to be with me, Lord, abiding with me and all, how about you take care of the groceries too? And I had to leave home in a hurry. I only packed a spare change of clothes. How about you take care of my wardrobe as well, God? And bring me back to my father’s house in one piece why don’t you? Keep Esau from killing me. If you’ll do all that, Lord, then, yeah, you can be my God.”

Jacob prays without tact, humility, or self-awareness.

And God does just as Jacob asks.

Jacob is clothed and fed and sheltered and reconciled.

Nothing that happens in the world happens apart from the free willing of God.Yet…God is persuadable.Several years ago now, I was at the infusion center to receive the Neulasta injection that bookended my every round of chemo. An old woman sat directly across from me, a red-orange tube running from a bag to her chest. She wore a blue scarf with peacocks on it around her small, bony head. Her face looked so sunken and her skin so stretched and translucent that guessing her age felt impossible. She greeted me—exhausted, her eyes only half open—with a distinct prairie accent when I sat down and cracked open my book.

I didn’t get past the first page.

She started to cry—whimper really—from the sores her chemo-poison had burnt into her mouth and tongue and throat. Beseeching the nurse, she pleaded, “make the pain go away.” She kept on like that, inconsolable, with no concern for what I or anyone else might think about her. In a different-size person you’d call it a tantrum.

Seeing her there, spent and defeated, I felt compelled to do the only work I could for her. I prayed. Quietly, under my breath, just above a whisper, my lips moving to the petitions. And when I finished, I made the sign of the cross over her.

“You religious?” the man in the next infusion chair asked me.

“Sort of, I guess.”

He went to wave me off, dismissively, but then remembered his arm was taped and tethered to tubes and the tubes to an IV pole. He’d been on the phone on work calls almost the whole time I’d been there. A gray tie that matched his hair hung loose from his unbuttoned collar.

“You really think that stuff works— prayer?”

He said it in a tone that suggested no believer anywhere at anytime had ever wrestled with such a question.

“Well,” I replied, “If prayer doesn’t work, then it’s entirely a waste of time.”

If prayer doesn’t work, then it’s entirely a waste of time.

He nodded seeming to appreciate that I had not evaded the stakes at the heart of his question.

“I’ve got a partner,” he said, “in my firm. He prays. He says he does it because it changes him. Like, he prays for patience and the practice of praying makes him more patient. Like meditation I suppose.”

I nodded and smiled wryly.

“You’d never know it from the way a lot of Christians talk about prayer,” I said to him, “But the content of prayer is not irrelevant to its benefit.”

The content of prayer is not irrelevant to its benefit.

He didn’t follow me so I said, “You’d be surprised how many people pray who do not believe in prayer.”

“A lot of them are ordained,” I added.

He laughed, and then he went back to his work.

A couple of minutes later he sat his phone down on his lap and raised his hands in a “What gives?” gesture.

“But how?” he said, “I mean, come on! You’re telling me that you think we can change God’s mind about God’s will?”

I smiled a wide and crazy smile.

“It’s totally crazy, isn’t it?” I said, “It’s tremendously preposterous— to say nothing of presumptuous— but that’s the claim. That’s the claim Jews and Christians make (at least the ones who haven’t lost their theological nerve). If the claim is wrong, then the gospel is a lie and prayer is nothing but a bunch of hot air.”

And then I pointed at the exhausted, whimpering woman across from me.

“The claim is not only that we can tell the Father what he ought to do about her; the claim is the Father will listen and may heed us.”

The old rabbis considered Jacob the father of faith.

How?

Jacob doesn’t know the promise of God so as to trust it. Jacob has not heretofore had any experience of God. If faith denotes a spiritual experience, Jacob has not yet had one. How is Jacob the father of faith? Jacob doesn’t even know the stories of the faith— he doesn’t realize he’s pitched a tent in the very spot Abraham called upon the Lord. How is he the father of faith? If faith is equivalent to virtue (like many of you imagine), Jacob has none.

Jacob is the father of faith, the old rabbis attested, because Jacob made a verbal reply to the God who addressed him.

He prayed.

He prayed a petitionary prayer.

He prayed, “Father, give me this, that, and the other, and you can be my God.”

The law commands faith.

The creeds describe faith.

Prayer is the act of faith.Prayer is the act of faith, and, put the other way around, a sure sign of a lack of faith is a reluctance to pray boldly.

Jacob is the father of faith because prayer is the most elementary act of obedience. It does not matter how many good works you do or how much you give. Alms to the poor do not substitute for prayer. Jacob is the father of faith because prayer is the most elementary act of obedience, and prayer is the most elementary act of obedience precisely because it is a correlative of the gospel.

The gospel is an address to you for you from the Living God. “This is my body given for you,” he says to you every Sunday. “In the name of my Son, your sins are forgiven.”“This is the word of God for the people of God.” Since God initiates a relationship of address, it follows that, in return, he wants to hear from you.

Prayer is the most elementary act of disobedience. Elementary but offensive.Just imagine—

Imagine an anthropologist from outer space, observing for the first time, Jews and Christians engaged in prayer.

What would she think?

Surely, she would conclude that we were engaged in dialogue with one on whom we are utterly dependent but one we could nevertheless influence.

It’s quite obvious.

Yet if asked a question like, “Do you really believe your prayer can change God’s mind?” many believers balk at the unambiguous implications of our practice.

Our evasions are not dictated to us by scripture.The God of the Bible hears the cries of his people as slaves in Egypt and is moved to deliver them. The God of Israel is talked off the ledge by Abraham, who convinces the Lord not to destroy every citizen of Sodom. The God of Abraham is persuaded by Jacob to go beyond the promise and also provide for Jacob’s room and board and meal plan.

The God of the Bible is persuadable.Prayer is elementary but it’s offensive.

Think about it—

When we bring God our petitions, we presume to advise the Maker of All that Is about how best to order the universe. That’s what we’re doing; that’s what we presume. We don’t pray simply because such prayers form us. We don’t pray to accrue any merit. We’re not practicing mindfulness.

No, we pray to tell the Creator how to govern his creation.

We presume that the cosmic course of history can be brought to respond to our concerns.Such presumptions are presumptuous.

Now to get overly philosophical or polemical but all of you have been shaped deeply by the Enlightenment’s conviction that we inhabit a mechanical universe whose processes (called nature and history) are immune to petition.

The great temptation, one which traditions like Methodism have largely fallen prey, is to reconstruct a God appropriate to this supposedly indifferent, mechanical universe.

Thus:

A God too impersonal and static, impassible and distant, to be pleased by our praise or persuaded by our petitions.

But if the gospel is true, if scripture is reliable, if faith is possible, then all of this is backwards.

This is the day the Lord is making.

If bold, presumptuous petitions are implausible in our world, then it is the world we misunderstand not God.

Which means, we’re worshipping an idol and we ought to repent and turn to the true God.

The Persuadable God.

In his recent book, Peace in the Last Third of Life: A Handbook of Hope for Boomers, Paul Zahl writes,

“I got a sincere but somewhat pathetic prayer request from an old friend last year, asking me to pray for her friend’s stage- four breast cancer. My friend asked me to pray for good medical care for the person, for patience and endurance for the person’s husband, for a sound mind among her family that would know when it was time to “pull the plug,” and for a loving exchange of ideas concerning the inevitable funeral. I wrote back, asking if the possibility of praying for remission in this case were on the table. She wrote back saying that it had not come up.

Then later, during the coronavirus pandemic, I received a series of prayers from the chaplains of the Episcopal prep school I attended. Not one of the prayers included a single note of supplication for the virus itself to be restrained or for healing to be given to any who had contracted it.

I used to be diffident about praying for the remission or healing of a physical illness, let alone of a mental incapacity or disturbance. I would pray for the sufferer’s acceptance and serenity much more often than for God’s intervention and victory.

I was wrong.”

Paul Zahl may have been wrong, but he is hardly alone.

When I first got cancer several years ago, I was astonished at the apparent unbelief in prayer by those who do it. Every person was sincere. It just goes to show how little sincerity has to do with discipleship.

“l’ll pray that God gives you strength,” people would tell me.

“I’m praying that God will give your doctors wisdom,” pastors told me.

“You’re in my thoughts,” far too many Christians told me.

Your thoughts? What in the hell good are your thoughts going to do? I’m dying. Why don’t you pray for God to make it not so?! Why don’t you attempt to persuade God to heal me?

Some did so pray.

And I am grateful for their prayers.

At the beginning of the Gospel of John when Jesus calls Phillip and Nathanel, Jesus reveals to them that he is the ramp Jacob sees laid down from heaven onto the earth. The Son of God, Jesus says, is Jacob’s ladder; that is— pay attention now, the Son is the means by which our communication with the Father is possible. This is Jesus’s point when he gives us permission to pray to his Father as our Father.

As Robert Jenson says, “This is to be taken seriously.”

We can dare address God with our petitions because Jesus has invited us into his conversation with the Father.

God is so gracious.

He hasn’t just made a decision about you in Jesus Christ. On account of Jesus Christ, he’s willing to listen to you. He doesn’t just allow he invite our views to be heard and weighed in his care of the universe, exactly as a parent listens to and considers seriously the views of their children.

“Our expressed opinion,” says Robert Jenson, “is an essential pole of the process of God’s decision-making.”

Because of Jesus, because you’ve been incorporated in to him, because you’ve been invited in, because his Father is now your Father too, the life of the Trinity is now like a parliament in which you are a member.

The life of the Trinity is now like a parliament in which you are a member.

God wants you to speak up. Make a motion. Voice your opinion.

The claim implicit in Christian prayer is astonishing. Most will not believe it.

Quite simply:

To pray to stake a claim over the care of creation.To pray is to presume co-determination of the universe.To pray is to participate in Providence.Any lesser claim evades the clear implications of scripture and makes prayer nothing but an empty practice of piety.

There is perhaps no stronger indictment of the Church in a secular age than the fact that this needs to be said clearly and without hesitation:

Prayer accomplishes things.When we pray for someone, when we petition God on their behalf, we intend thereby to accomplish something for them.

Prayer is the work grace gives us to do. It is our work in the world on the world. It is our work in the world for the world’s future.

Prayer pulls us into the working out of God’s governance of the world. Prayer is our participation in Providence. In Jesus, the Father has given you a say in how his history will come out.

So, let us pray.

Let us pray prayers that are big enough and bold enough that only God can bring them off.

Pray for the war in Ukraine to be ended. Pray for all its victims to be mended. Pray for the Lord to smite Vladimir Putin. Pray for a major health event to strike Donald Trump. Or Joe Biden if that’s your politics.

In either case, pray like prayer does work.

Pray for every racist cop to be unemployed. Pray for every homeless to be housed— not fed. Pray for me to be a better preacher. Pray for Peter to be a better dresser. Pray for the gospel to reach your unbelieving child. And gift them saving faith. Pray for miracles. Pray for your addicted loved one to be, inexplicably, set free. Pray for all professional Philadelphia sports teams to fail.

Pray for Gary to be healed.

Pray for Gary and Mike and Clarence and Denny and anyone else not yet on the other side of the “now done darkness” to be healed.

Prayer accomplishes things.

You can change the Persuadable God’s mind.

By the baptism of his suffering, death, and resurrection, Jesus Christ has invited you into the household called Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Don’t tiptoe around quietly.

Don’t put your head down and your hands in your pockets.

Don’t keep your opinions to yourself.

Speak up!

SPEAK UP!

If the world knew what you know by faith, they would be grateful for your prayers.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 22, 2023

The Buck-Stopping Will

Thanks for reading Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Genesis 27.1-13

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself,” the prophet Isaiah exclaims to the Lord at the end of a long ecstatic utterance.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

In the Gospel of Luke some listeners interrupt Jesus’s lesson plan. He was just about to teach them the parable of the barren fig tree. They interrupt and ask him if he’d seen the news trending on Twitter. “Did you hear Jesus?” they ask, “Pontius Pilate killed a whole church full of Galileans. He had them struck down while they were in the middle of worshipping the God of Israel according to God’s law.”

Luke doesn’t report the rest of their questions. Luke needs not.

We can hear the questions in our own voices. Why? Why do bad things happen to (sinful) people? Where? Where was God when members of his flock were slaughtered like sheep? How? How do you explain this tragedy, Jesus? Was God punishing them? Is the Almighty an underachieving pretender? Is there a reason it happened?

Is there a will which willed it?

We desperately want Jesus to say, “No, shit happens.”

But the Lord Jesus doesn’t say “Yes” or “No.” He instead answers in a manner that certainly would bar him from ordination in the United Methodist Church. The Lord Jesus replies, “No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.”

God’s gonna do the same to you unless you repent.

That’s not a “No.”Nor is it a “Yes.”

“Those Galileans weren’t any worse sinners than the lot of you; God’s gonna do likewise to you unless you repent.”And then Jesus points to another news story on his Twitter feed.

“What about the eighteen folks who perished when the tower in Siloam collapsed. You think they were especially rotten in a manner different from you? Of course not, but I’ll tell you what. Unless you repent, God’s gonna do the same to you.”

In the Gospel of John, the disciples ask Jesus about a man born blind.“Rabbi, who sinned? This man or his parents that he was born blind?”And Jesus very helpfully refuses to accept the premise that the man’s blindness has anything to do with anyone’s sinfulness. But Jesus rejects the premise for reasons that are even more offensive to our enlightened sensibilities than the original premise. Jesus says God made the blind man blind. God made him blind; so that, the work of God might be revealed in him. Again, Jesus would never get past the United Methodist Board of Ordained Ministry.

There are two conclusions we can draw from these responses by the Lord Jesus, one comforting and the other unsettling.

The Lord Jesus forbids us from conjecturing any causality between a person’s sinfulness and the suffering that besets them. Jesus won’t allow us to say this thing is happening to them because of that thing they did.

The Lord Jesus believes— and so we are compelled to believe— that there is a will that wills in the world, often in ways that shock and offend us.

“Unless you repent, God’s gonna do the same to you.”

Such a God appears even more mysterious when we insist on saying that such a God is one and the same with the Jesus who speaks of him.

“I am the Lord,” God declares to the prophet Isaiah in that same passage, “I make weal and create woe.”

And the prophet replies, “Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

And the Lord does NOT correct him.

Notice—

It’s not, “Truly, thou art a hidden God,” as though the matter was God’s distance from us or our perception of him.

It’s not that God is hidden. It’s not an adjective. It’s a verb. God hides. God hides himself.

God is the hidden Lord of his own unhiding, says St. Gregory.

At the start of Advent, Maria Kamianetska mailed a photograph to her husband who had remained behind in their home village in Ukraine.

She attached a note, “You have a son.” In the picture, baby Serhii’s eyes were closed. On his head sat a little white hat. His tiny body was swaddled in a matching blanket. Maria gave birth to him in a city maternity ward in a region of Ukraine allegedly annexed by Vladimir Putin’s army.

After nine months of carrying her baby through a war zone, Serhii had come into the world at a healthy six pounds with three siblings anxious to meet him. They never did. After nursing him and lulling him to sleep and laying him in the crib next to her bedside, a Russian rocket crashed through the maternity hospital. Like that tower in Siloam, the maternity ward’s walls collapsed with everyone inside.

Serhii is the youngest casualty of Putin’s invasion. He did not live long enough to be issued a birth certificate. All of the nearly five hundred other children killed in the war thus far have been older than Serhii. Serhii was so young and so tiny that rescue workers picking through the rubble at first mistook him for a doll.

“That’s my son!? Maria, his mother, had shrieked.

Fifteen attended baby Serhii’s burial. Shelling rumbled in the distance of the cemetery as the priest placed a cross bigger than the baby into the casket and prayed the commendation.

Serhii’s siblings didn’t attend the burial. They knew their new baby brother wasn’t coming home after all but they did not know why. Because neither Maria nor her husband knew how to explain Serhii’s death to them.

Because, after all, what is there to say except, ““Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

The hiddenness of God—

It’s more than an unmistakable fact of human experience. It isn’t merely a feature of the Book of Isaiah. It’s Christian dogma. As much as the doctrine of the incarnation or justification through faith alone, the hiddenness of God is one of the constructions with which we speak Christian. The contemporary American theologian, Robert Jenson, writes that when he first encountered the dogma as a young student, he said to himself,

“THIS about God’s impenetrable hiddenness is really great stuff! And, moreover, it surely must somehow be true.”But the dogma doesn’t assert quite what you assume.

God’s hiddenness does not name his metaphysical distance from us. Quite the opposite, the belief speaks to the problem of the character of God’s presence with us. If God were far off in some metaphysical distance, a cosmic butler in the great by-and-by, then we could exonerate God from the troubles and tragedies that befall our history.

But such a distant God is not the God of the Bible.

Such an aloof, hands-off God is not the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ nor is it their Holy Spirit who blows where the Spirit wills to blow. If God rules as his creation’s here and now Lord, if Jesus Christ sits at the right hand of the Father, then baby Serhii not only sits on his ledger waiting to be to be accounted but baby Serhii also masks God’s visage. Baby Serhii is an instance of God’s hiding.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

The prophet Isaiah utters that confession upon hearing God announce that God would use a pagan emperor, Cyrus, to deliver Israel from the exile into which God himself had originally sent them.

“God works in mysterious ways his wonders to perform,” sings the hymn. William Cowper, the hymn writer, suffered from lifelong suicidal depression. He knew of what he sang.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

That God hides does not mean that God is only vaguely glimpsed.

You can’t put God in a box, some say. Never mind that God, having already put himself in tent and temple, placed himself in a space no bigger than Mary’s womb. The hiddenness of God does not mean we know God only partially. No, Jesus is the fullness of God. There is no knowability of God yet to be discovered that lies beyond Jesus. That God hides does not mean that God is not glimpse-able.

The hiddenness of God instead refers to the impenetrability of God’s moral agency.

The hiddenness of God marks the boundary beyond which we cannot discern a good or moral pattern to God’s providence.God is good (all the time), we profess. But, with scripture, we cannot say how. We cannot always— or even, often— say how God is good. This is what St. Paul is after when he cites Job and Isaiah and asks, “God’s ways are unsearchable…who has known the mind of the Lord?”

The way God is God seems to us morally problematic.That’s what the dogma claims.Throughout scripture, the hiddenness of God does not refer to the weakness of our knowledge or absolute uniqueness of God. It refers to God’s reality as a moral agent involved with other agents. It refers to God’s history with us. As Martin Luther once said,

“If we observe how God rules history and judge by any standard known to us, we must conclude that either God is wicked or God is not.”

Consider, for example, the continuing story of God’s promise in Genesis 27.

Isaac and Rebekah’s marriage is the only monogamous marriage in the entirety of the Book of Genesis, yet obedience to God’s promise (“The elder shall serve the younger…”) tears it apart. So much so, notice, Isaac and Rebekah never appear on stage together. Neither do Jacob and Esau.

We remember this story as Jacob cheating his brother out of his inheritance but that’s not the case. It’s Rebekah cheating her son by means of her other son. Jacob is a reluctant co-conspirator, “Look, my brother Esau is a hairy man, and I am a man of smooth skin. Perhaps my father will feel me, and I shall seem to be mocking him, and bring a curse on myself and not a blessing.”

And already in the narrative, Jacob and Esau are not young men.

They’re seventy-seven years old. Esau has two wives and children and grandchildren, all of whom are dispossessed by Rebekah’s deception of her husband.

The plot ends with the family ruptured and the cheated brother vowing to kill his twin.

Jewish and Christian interpreters alike have sought explanations to justify the theft and dishonor Rebekah and Jacob commit. Esau was a hypocrite, they speculate, he didn’t truly love his father. He loved his father for the prospect of his father’s wealth. Jacob was the virtuous, obedient child, they say, he gets the inheritance because he was the deserving one.

But none of that is in the text.

The text isn’t even really about them; it doesn’t tell us anything about their motives or character. The text is straightforwardly about God and God’s promise. The text is about the continuing forward of the promise, and the consequence of its continuance in this instance is a broken family and a vow of blood vengeance.

The tradition of squeamish interpretation aside, quite simply:

Esau is cheated.

All is house is disinherited.

Isaac is dishonored.

Jacob is exiled.

And Rebekah bears the curse of his transgression.

All because…this is the will of God.“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

It isn’t simply that God is involved in the messiness of our history.

God is, in some way we cannot comprehend, complicit in it and responsible for it. This is simply the flip side, the God side, of the doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith. You are justified apart from any of your works, which means God justifies you by his will alone. It’s a strict implication of the doctrine of justification that whatever happens happens by God’s will— even those things we freely choose. God wills not what we freely choose but God wills that we freely choose.

Several years ago, shortly before his death, the theologian Robert Jenson agreed to be a guest on my podcast, and during the course of the interview he spoke about the hidden God:

“For example, when asked why some are healed and some are not, I answer because that is the will of the Lord. You know that I have Parkinson’s disease. Now that is degenerative disease. So that isn’t reversible. Nevertheless, I pray to be healed and one has to live with that. As to why there is so much suffering in the world, such evil, that’s the famous theodicy question, and in my judgment it’s the only good reason not to believe in God. To say despite all the suffering in theworld, all the suffering in our lives, God is good: that’s as far as can go and no further.”

When I was a college student, I often worshipped at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. It was just off grounds so I could walk easily. Even better, St. Paul’s had a 5:30 service on Sunday afternoons, which fit nicely with Saturday nights.

I remember one Sunday during Lent. This lady was in front of me in the receiving line after worship. She looked to be in her fifties. I could tell just from her bearing that she was righteously livid. Her white hair was tightly braided. She wore wire glasses and plain slacks and a shirt that smelled of grass clippings. She poked the priest in the chest when he offered her his hand.

“How dare you!?” she exploded.

He looked genuinely flummoxed.

Unspoken words fell stillborn from his lips.

“How dare you take the word and the absolution away from us.”

Then I knew as quickly as the priest what she meant. For the season of Lent that year, the church had replaced— I kid you not— the scriptures with readings from Robert Frost’s poetry and they had decided to “put away the absolution” until Easter so that there was only confession of sin but no forgiveness.

“How dare you take those away,” she hollered in the way of someone who hasn’t yet realized they’re hard of hearing.

“I’m a social worker. Do you have any idea the hell I wade through every day? Just yesterday I was with a child with cigarette burns all over his body. You can probably guess who put them there. And Wednesday it was a mother too strung out to bother noticing her baby was malnourished. Most of my every days it’s like God’s nowhere to be seen. Don’t you dare take away two of the places he’s promised to be found.”

And the priest just nodded with an awkward smile like this was a worship planning suggestion. But she just stood there, as immovably determined as Rebekah before Jacob.

“Well,” she said.

“Well, what?” the priest asked.

“You need to absolve me,” she said, “In fact, you need to announce the forgiveness of sins to all of us. I’m not moving until you do.”

And she held out her arms like she was holding back a flood.

The red-faced pastor made the sign of the cross in the air and said, “In the name of Jesus Christ, your sins are forgiven.”

The line of folks behind me in line mumbled in reply, “In the name of Jesus Christ, your sins are forgiven.”

“Maybe I ought to go to law school,” I thought to myself.

The world is constituted by worse than deception. All due respect to Dr. King, the arc of the moral universe does not, on its own, bend toward justice. Everyone knows, firsthand even, the hiddenness of God. It’s a very shallow faith that has not wrestled with the fact of the hidden God.

If God can be judged by any standard known to us, we must conclude that either God is wicked or God is not.

Everyone knows God hides. Only Israel, only the Church, know that the self-hiding God can nevertheless be found in creaturely means like the word that absolves, the water that washes and the bread that is the God of the Passover’s own body. God hides, the dogma insists; so that, God may be found only in the promises through which he gives himself to us.

To say that Abraham and Jacob and Rebekah were justified on account of their faith in God’s promise— that doesn’t go far enough.

The claim is really that the Lord wants to be known and related to in no other way but faith.Why?Because, just like everyone else in your life, God doesn’t want to be used. That is, after all, the essence of idolatry.God doesn’t want to be used. And we are not neutral seekers of God’s majesties. God doesn’t want to be used. Like any other person in your life— and God is a person— God doesn’t want to be used. God wants to be trusted. And loved. And so God hides. In every way. Except in the places where he’s promised we will find him. In a word that says, “I will raise you from the dead.” In water that says, “You are mine.” In wine and bread that says, “You’re wondering where I am for you. I’m here, as near to you as your lips and your belly.”

Still, the fact that the God who hides has promised he can be found in, say, bread or the absolving word does not absolve God of, say, baby Serhii or whatever dread and suffering looms over you. If God is the buck-stopping will of history, then the buck stops with him. We’re still left with this apparent split in God’s image:

The God who is the absoluteness of the gospel promise is pure love. The will behind all events is not so easily apprehended as pure love or even as pure justice.

“This is my body, broken for you.”

“God’s gonna do likewise to you, unless you repent.”

What do we do about this apparent split in God’s image?

If God wants to be known and related to on no other basis than faith, then we have no other recourse but to abstain, abstain from any attempt to reconcile the apparent contradiction.

On the one hand, we admit that God is the ambiguous will behind all events, good and evil— that there is a will behind all events the gospel compels us to affirm.

On the other hand, we hear and trust the gospel of God as pure and personal and universal love.

And finally, we insist that these two images nevertheless constitute one and the same God but we dare not say how.

The how is the one fundamental truth reserved for revelation on the last day, when time ends, and all the jarring and dissonant notes of history are gathered together in God’s great fugue called creation.

What do we do with the hidden God? We abstain from any attempt to reconcile him with the crucified God. We admit God is the ambiguous will behind all events. And we trust the God of the gospel. But we abstain from saying how they are one and the same God.

The missing how is the darkness.

According to the Washington Post, it was cold the day they buried baby Serhii so Maria, baby Serhii’s mother, bundled up in a black winter puffer coat. On the back of the black jacket were the words,

“Everything will be fine. It will be even better every day.”

The words seemed to be an absurd contradiction to the artillery shelling that could be heard in the distance from the cemetery and the tiny coffin being lowered into the earth. But Maria’s black jacket is no different than what we do when we take bread, break it, acknowledge a world that would crucify him all over again, yet nevertheless look to that day when Christ will come back in final victory.

Faith trusts that, on that day, on the last day, in The End, God will all have told with his history with us not only a coherent story but a good one.“To say despite all the suffering in the world, all the suffering in our lives, God is good: that’s as far as can go and no further.” Actually, we can go a bit further. We can come to the table.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 15, 2023

Hope is the Child of History

Thanks for reading Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Genesis 25.27-34

“What then are we to say about these things?” the Apostle Paul writes at the crest of his epistle to the Romans. “If God is for us, who is against us?” Paul asks the church at Rome. For Paul, it’s not a rhetorical question. For Paul, it’s a question at the beating heart of the Bible.

If God is for us— all of us— if God is determined to reconcile and redeem all of us, then what could stand in God’s way? “What can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?” the apostle asks. And then, one by one, Paul proceeds to eliminate the possibilities:

Hardship. Check.

Injustice. Check.

Persecution. Famine. Check. Check.

Nakedness. Nope.

War. Not it either.

What then, in the end, can separate us from God? Not Death. Not Rulers. Not Powers. Neither things present nor things to come. Not anything in all of creation. NOTHING can separate us from what God wants to do with us. Except, the Apostle Paul does leave one possibility off his list; see if you can spot it:

Hardship

Injustice

Persecution

Famine

Nakedness

Peril

War

Death

Rulers

Powers

Notice there is one possibility missing from Paul’s list, one potential dis-qualifier lingers still.

You.

Can you finally separate yourself from the love of God?

Can I?

Have we been made with the ability to sever ourselves forever from the love of our Maker?

If Injustice and Persecution and War can’t leave our ledgers permanently in the red, can our Refusal?

Back in the day, when I worked as a chaplain at Trenton State Prison in New Jersey, part of my routine, every week, was to visit the inmates in solitary confinement. It was a sticky, hot, dark wing of the prison. Because every inmate was locked behind a heavy, steel door with just a sliver of thick plexiglass for a window, unlike the rest of the prison, the solitary wing was as silent as a tomb.

Whenever I visited solitary, the officer on duty was almost always a fifty-something Sergeant named Moore. Officer Moore had a thick, Mike Ditka mustache and coarse sandy hair he combed into a meticulous, greased part. He was tall and strong and, to be honest, intimidating. He had a Marine Corps tattoo on one forearm and a heart with a woman’s name on the other arm.

The Old Adam in me would described Officer Moore as an asshole.

Whenever I visited solitary he’d buzz me inside only after I refused to go away. He’d usually be sitting down, gripping the sides of his desk, reading a newspaper. I hated going there because, every time I did, he’d greet me heated ridicule. He’d grumble things like, “Save your breath, preacher, you’re wasting your time.” He’d grumble things like, “Do you know what these people did? They don’t deserve forgiveness.” He’d grumble things like, "They only listen to you because they’ve got no one else.”

“No, they’ve got someone other than me,” I’d tell him, “That’s why I’m here.”

Once, when we gathered for worship, I’d invited Officer Moore to join us. He grumbled that he’d have “nothing to do with a God who’d have anything to do with trash like them” and he refused to come into the service. He sat outside instead with his arm crossed. The locked prison door between us.

About halfway through my time at the prison, Officer Moore suffered a near fatal heart attack; in fact, he was dead for several minutes before the rescue squad revived him. I know this because when he returned to work, he told me. He tried to throw it in my face.

“It’s all a sham,” he grumbled at me one afternoon.

“I was dead for three minutes. Dead. And you know what I experienced? Nada. Absolutely nothing. I didn’t see any bright light at the end of any tunnel. It was just darkness. Your god? All make believe.”

“Bless your heart," I thought.

"Maybe you should take that as a warning,” I said, “Maybe there’s no light at the end of the tunnel for you.”

He grumbled and said, “Don’t tell me you, Mr. Grace and Forgiveness, believes in hell?”

“What makes you think I wouldn’t believe in hell?” I asked.

“Oh, and since I don’t believe in your Jesus, I’m going to hell? Is that it?”

Officer Moore pushed his chair back and fussed with his collar.

He suddenly seemed uncomfortable. His eyes took a bead on me.

“So what the hell is hell like then?’ he asked, smirking, “Fire and brimstone, I mean, really?”

“No,” I said, “fire, brimstone, gnashing of teeth, those are probably all metaphors.”

He let out a sarcastic sigh of relief.

So then I added, “They’re probably metaphors for something much worse."

That got his attention.

“Your loving God sends people to a place worse than brimstone just because they don’t believe in him?" he asked.

“Who said anything about God sending them there?” I replied, “No, I think hell is like a prison where the door is locked from the inside.”

He looked at me, suddenly no longer with contempt.

“It’s like C.S. Lewis said,” I told him, “In the end, there are only two kinds of people: those who say to God, “Your will be done,” and those to whom God says, “Your will be done.”

But, I wonder. Is that right? Is it even possible? Do sinners possess the stubborn strength to fight God to an everlasting draw? Can we separate us ourselves from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?

On the one hand, it appears we are able.

After all, scripture is unwavering in the sole qualification for salvation.

“Christ is the end of the law of righteousness,” the Bible says, “for everyone who believes.” “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus Christ is Lord,” says scripture, “and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” The bar is the same in the Old Testament too. The Book of Joel says quite clearly, “Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord [in faith] will be saved.”

Can we separate us ourselves from the love of God? On the hand, it certainly seems so, for unfaith abounds.

On the other hand, though, Paul insists that the word of God cannot fail.

“My word will not return to me void,” the Lord tells the prophet Isaiah. The word of God can only work what it says, do what it decrees, accomplish what it announces. And the word says clearly, the Lord’s not content with just you and you and you. God wants all of you.

For the apostle Paul, this question is no theological abstraction. The reason that famous passage in Romans is so impassioned is because Paul is agonizing over the fact of Israel’s unfaith. The God of Israel has raised his eternal Son from the dead, yet the Israel of God believes not these tidings.

“Does this mean God has rejected his people?” Paul asks at the top of Romans 11. The grammar of the question gives away the answer. As soon as Paul refers to Israel as God’s possession he’s already shown his tell. “By no means!” Paul answers immediately. After all, God made a promise, “I will be your God and you will be my People.” And if God can break his no-strings-attached, unconditional, promise, then God is the very troubling answer to the question,

“What can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?”

Does this mean God rejects those who do not believe?

By no means!

For all the ink Paul spills in his anguish, the problem can be put rather simply:

God desires all to reciprocate his love and mercy— made flesh in Jesus Christ— with faith, alone.

Many— but especially the Israel of God— do not so believe.

Finally— here’s the kicker— God’s word can no more fail than God’s promise can be broken.

In wrestling with this sorrowful conundrum, Paul looks to the past and there he discovers a pattern that enables him to predict a hopeful future. Specifically, Paul considers the twin sons of Rebekah (you were wondering when I was going to get around to our text). Jacob attempted to swindle his older brother at a moment of acute vulnerability while Esau foolishly was willing to forsake his entire inheritance in order to satisfy his appetite.

Neither of Rebekah’s children prove exemplary; nevertheless, both Jacob and Esau are chosen by God while they’re still in Rebekah’s womb. God’s election happens in utero. The promise was spoken to Rebekah, Paul writes of Jacob and Esau:

“though they were not yet born and had done nothing either good or bad— in order that God’s purpose of election might continue, not because of works but because of him who calls— Rebekah was told, “The older shall serve the younger…” So then it [the purpose of election] depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who has mercy.”

As Paul dwells on his fellow Jews’s apparent rejection by God, Paul sees a pattern behind the way God has worked in the past, election and rejection.

Abel over Cain.

Sarah instead of Hagar.

Moses against Pharaoh.

David to the exclusion of Saul.

Israel rather than any other nation of the earth.

In each and every case, God’s choosing “neither corresponds to nor is contingent upon prior human difference.”

Jacob and Esau are twins.There is no difference between them—that’s precisely the point!God’s choice creates the difference.God elects for the promise to go through Jacob not Esau, and God elects Jacob not Esau before either Jacob or Esau could do any bad or any good. Therefore it is a choice God makes irrespective of merit or demerit. It’s a choice premised on the providence of God not on the performance of either Jacob or Esau.

What’s more, Paul notices that this pattern of election and rejection, faith in some and hardness of heart in others, is an inextricable part of the history God makes with his world. What looks like God’s rejection of some in scripture always serves God’s redemption of the whole. The Father seemingly rejecting the Son, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” even that forsaking is for all.

Hope is the child of history.

Paul’s hope for the future, his hope for those who do not believe, is a child of this history, election and rejection. “Has the Israel of God stumbled so as to fall away forever?” Paul asks before he answers in the very same breath, “No!” Instead Israel’s unfaith, what appears to be God’s rejection of them, it is a choice God has made for the reconciliation of the whole world, Paul says. “For God has consigned all to disobedience [the Gentiles’s their ungodliness, the Jews’s their unfaith],” Paul writes, “so that he may have mercy on all.”

God has consigned some to unbelief; so that, God may have mercy on all.The failure of some to believe is, in fact, the means by which God is working even now to show mercy to all.

In other words— pardon the cliche— it’s all a part of God’s plan.

God’s predestination.

It’s not surprising that Paul concludes Romans 9-11 with God’s plan. Paul began with predestination too. Just before Paul wonders, “If God is for us, who can be against us?” Paul reminds us that those whom God predestines— the whole world— God calls. Those whom God has chosen according to his plan (ie, all of us) God calls, and God calls— specifically— with his justifying word (ie, the Gospel).

That’s Romans. Chapter eight. Verse thirty.

That’s the word of God.

Predestination.

It’s not a primordial choice that makes you no more than a bit of code in the Almighty’s matrix. It’s a present-tense call. That is, God applies his predestination in the here and now through the handing over of the goods of the Gospel.

Like Jacob and Esau, God makes choices.

God has consigned some to unfaith.

Why?

So that, those who do not believe might be summoned into faith by the handing over of the goods.

By you.

By Christ’s own word on the lips of the likes of you.

As scripture says plainly, “faith [which saves] comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ.”

Predestination is not abstract.

It’s auditory.

Predestination is not speculative.

It’s spoken.

The God of an idea, like universalism, that says “God loves everybody,” such a God never gets around actually to saying it to anyone.The God of predestination, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, wants to say to everyone, a creature at a time, “I love you. I forgive you. You’re mine.”Is that clear, I wonder? Predestination isn’t a divine decision that hovers a thousand miles above us and a billion years behind us. Predestination happens, here and now, in the gospel word on the lips of a sinner to another sinner.

As Paul writes to the Corinthians, “For it pleases God to save…”

How?

“It pleases God to save through the folly of proclamation,” Paul says.

In other words, it please God to save the whole world through such foolishness as you and your words.

A couple of months ago, Betsy shared with me how a stranger wandered into the Mission Center one afternoon while she was there sorting food. He’d walked there, for two hours, all the way from the other side of Woodson High School. He wanted— he needed, he said— to confess his sins.

Betsy says she was reticent at first, “I’m not a pastor. There’s no preacher or priest here. Maybe if you call and schedule…”

The stranger was undeterred, “I need to confess.”

So Betsy relented and said, “Alright, I’ll listen to you.”

And this stranger spilled out into her ear his secret burdens and his most troublesome sins. After he was finished, Betsy says, he peered up at her expectantly.

“Does this mean I’m forgiven? Does God forgive me?”

And Betsy says she replied, “Well, I’m not sure. Who am I to say whether or not God forgives you?”

When Betsy told me how she had answered the stranger— we were standing on the church steps after worship one Sunday— I initially responded pastorally, “Betsy! No!”

“I should’ve told him he’s forgiven? But I’m not a pastor…”

“You’re baptized, Betsy,” I may have said a little loudly, “You’ve been called to put just such a word in the ear of any person God sends your way.”

Now, it’s not Betsy’s fault.

She hadn’t yet heard this sermon.

The rest of you, however, will be without any excuse because you’re about to hear me announce that you have been called.

You have been called.

What do you mean I’ve been called? I was just a baby when I was baptized!

So what? Jacob was even tinier.

The Lord God desires to save all. And the Lord God has elected to show mercy upon all through those whom he has called. And just as surely as God chose Jacob over Esau, he has consigned some to unbelief so that unbelievers might hear God say— hear God on your lips say, “I love you. I forgive you. You’re mine.”

By virtue of your baptism, you have been called to a particular, peculiar task.

The baptized are authorized to do the mighty acts of God’s predestination. Your baptism commissions you, therefore, to speak not about God. Talk about God never comforted any conscience. Talk about God has yet to save a single soul.

Your baptism authorizes you to speak not about God but for God. God wants to hide on your lips in a word like, “Your sins are forgiven” or “Christ Jesus will raise you from the dead” or “The Devil has no power over you because Christ Jesus has saved you.”

God wants to hide on your lips in the promises he’s given us.

So, the next time it happens to you you’re without any excuse. You have been called to speak for God, to apply his predestination in the present. And if you’re dubious that you’ve been called, baptism notwithstanding, I can remove all grounds for doubt right this very moment, “In the name of Christ Jesus, I summon you to speak for him.”

There.

You’ve just been called again by God.

You see how it works?

The Holy Spirit lives in the promises he’s given us to speak.

The purpose of the doctrine of predestination is not speculation.The purpose of the doctrine of predestination is proclamation.The purpose of the doctrine of predestination is to give you a platform on which you can stand. It’s to give you certainty. It’s to give you an actual message, a concrete promise to deliver, because, by the doctrine of predestination, you can know without any doubt that if someone comes to you with unfaith, if someone comes to you burdened by their sins and regrets, if someone comes to you fearful of death or feeling forsaken by God, then it’s because the Lord God has sent them to you.

The Lord God has sent them to you— you, whom he has called to speak for him. God has chosen them and sent them to you. This is how God’s plan plays out. It’s not how I’d plan the salvation of the whole world, but give the Big Guy credit.He himself calls it folly.

Therefore—

When God sends someone like this to you, you don’t speculate.

Well, I think God probably forgives you. I guess we’ll see.

When God sends someone like this to you, you don’t settle for empathy, which is easier.

I’m here for you. You’ll be in my prayers. This is what worked for me.

When God sends someone like this to you, you don’t make appeals or exhortations. Give it over to God. Pray on it. Invite Christ into your heart. Repent and believe.

No, no, no.

You hand over the goods.

The Lord God in his predestination has set this creature before you. In that very moment. You don’t invite them to church next Sunday or entreat them to read their Bible or encourage them to talk to a pastor.

No, you’ve been called. You proclaim to them. You speak a promise over them. You deliver a promise that scripture authorizes you to promise.

I’m absolutely serious.

You can say— you must say— to the person burdened by shame or sin, “The Lord has chosen you and sent you to me so that I can say to you, “In the name of Jesus Christ, all your sins are forgiven.”

You promise the loved one who’s fearful and dying, “The next voice you hear will be the voice of Jesus Christ calling you, like Lazarus, straight out of your grave.”

To the person feeling forsaken by God, you say, “You were bought with a price. You belong to Christ Jesus. He’s got you. And he’ll never let you go.”

Every other time I went to the solitary unit at Trenton State, as always, Officer Moore would balk at buzzing me inside. He’d grouse about how I was wasting my time with “these losers,” and he’d snarl about how the gospel is so much foolishness. “A whole lot of nonsense,” he’d grumble, inspecting for contraband the bibles I’d brought with me. In the words of Paul, he remained “consigned to disobedience.” Locked up in unbelief.

Because I’d never bothered to use the keys Christ had given me. Officer Moore’s unfaith is on me. It’s my fault.

The trouble with thinking predestination is a divine decision that hovers a thousand miles above us and a billion years behind us is that it lets us off the hook.

It leaves no place for proclamation.

I sometimes spoke with Officer Moore about God but I never ponied up and spoke for God. I never dared to wave away his unbelief and say to him straight-up, “Christ Jesus has sent me to you to summon you to faith in him. Trust and believe.”

Can anything separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?

As it turns, the “No” depends on you daring to do what he redeemed you to do.

Which makes it all the more imperative that I remind you that Christ is the host of this table.

Christ is here to give himself to you, not just in words but in wine and bread, so that you will take him at his word when he says to you, “I love you. I forgive you. You are mine.”

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 8, 2023

The Faithful Deceit of Laughter's Wife

Thanks for reading Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Genesis 25.19-28

Tom Radney was an Atticus Finch like fixture of Alabama politics during the crucible of the Civil Rights movement. Upon graduating from the University of Alabama Law School, Radney first served as an Army JAG officer during the conflict in Korea. After the war, Radney returned to Alabama. He married the daughter of a prominent state legislator, and he opened a law practice in Alexandria City, the seat of Tallapoosa County where he also became a lifelong member of First Methodist Church.

The trouble started when, through his civil and criminal work, Radney became better acquainted with the injustices of the Jim Crow status quo. Radney then realized he’d been on the wrong side of the race issue. The threats and attacks, though, began when Radney volunteered to run for the Alabama Senate a year after Selma’s Bloody Sunday. In response to his advocacy, the Klan called his wife and made death threats. They burned crosses on his front yard for his children to see.

They intimidated his secretary before fire-bombing his law office.

Shortly before his death, Radney told the story of how, sometime during those frightening days, he was at work on a case in his office when his secretary knocked softly on his door.

“I’m sorry, sir,” she said, “I told him you were busy and didn’t wish to see anyone but he insisted “He’ll see me.””

Radney said, “Alright, let him in.”

An imposing man with a square head and horn-rimmed glasses and hair parted down the middle stepped into the office and stood over the mahogany desk.

“Mr. Radney,” he said in a North Carolina drawl, “I am your bishop, Kenneth Goodson.”

Radney stood up and offered his hand.

“Of course, pleased to meet you. What can I do for you?”

The bishop stood there, not taking the hand, like he was there for too important a purpose for mere pleasantries.

“I believe I’m here to do something for you.”

Radney sat back down at his desk and stared at the strange, serious man.

“When I was consecrated as bishop and sent to Alabama,” he said, “the Lord told me— the Lord promised me— that I was being sent here to bless those doing his righteous work to undo Jim Crow. And when I heard about your work and the hardships that have come upon you in the course of it, I knew I’d been sent here to bless you.”

“They threatened my children,” Radney said, his voice caught in his throat.

The bishop nodded but then asked a non sequitur, as though such dangers, toils, and snares are simply part and parcel with following a Jesus Christ.

“Can I assume,” the bishop asked the attorney, “The Methodist Church is responsible for the work you do?”

Radney chewed on the question— he’d never reflected upon the cause of his conversion— and answered, “I suppose probably so; I’ve been a Methodist my whole life. Of course, George Wallace and Bull Connor are both Methodists too so maybe my change of heart owes more to miracle than to Methodism.”

As though he had already arrived at exactly the same conclusion, Bishop Goodson said to him, “Rise.”

“And I stood up immediately,” Radney said.

“Come here,” the bishop ordered him, “Stand before me.”

“And I did as I was told. He laid these heavy hands on my head and looked at me intensely and said, “I’m going to bless you— that’s why I’ve been sent here, to you. Kneel.”

And Radney recalled, “So I got down on my knees there on the carpet at his feet.”

“Tom Radney,” the bishop prayed, “In the name of Jesus Christ, by the power of the Holy Spirit, I bless you with the strength and protection of the Almighty Father; so that, you will remain steadfast and never shrink from the holy task he has set before you.”

“And then he said, “Amen,” and he left,” Radney remembered, “My secretary wondered what in holy hell had happened because when she came into my office, she found me curled up in a fetal position on the floor, weeping like a baby. It was one of the most pivotal moments in my life. Somehow he knew to be there, right then, for me, with that promise from the Lord.”

As a way of avoiding the Bible’s authority and downplaying its coherence, critics often will insist that the Bible is not one, unitary book but, in fact, a library of books. And within that library called the Bible, critics will point out, there are many literary genres: histories, legal codes, gospels, liturgical prayers, primeval myths. There’s even a steamy, erotic poem.

The Bible, such critics contend, is like your Amazon Kindle; it’s a device with many different, possibly unrelated books on it.

Such a comparison is as common as it is incorrect.

By adding the story of Jesus Christ (the Gospels) and their story with Jesus Christ (the Epistles) to Israel’s scriptures, the ancient church made the assertion that the now Christian Bible tells a fundamentally connected and coherent story.

Lengthwise, from beginning to end, the Bible hangs together christologically; that is, according to Christ, who, before he is Mary’s baby, is the second person of the Trinity, eternal and pre-existent, by whom all things were made.

The Bible hangs together as a single christological story or it does not hang together at all.Therefore, Jesus Christ is the hermeneutic— the interpretative lens— by which all the Bible can be read.

Take, for example, the opening of the Jacob narrative in the Book of Genesis.

Like her mother-in-law, Sarah, Isaac’s wife does not become a mother until she is an old woman. For twenty years, the text tells us, Rebekah’s husband “prayed to the Lord for his wife, because she was barren.” Isaac— his name means “Laughter,” remember— pleaded with God for two decades, so long that his desire for a child went from no laughing matter in the beginning to what must’ve felt like a joke near the end. No one shops for maternity dresses or packs a hospital go-bag after they’ve received their AARP card in the mail.

The Israelites, whom God rescued from slavery in Egypt only after they had cried out to the Lord for generations, were the ones to write down these memories of their patriarchs and matriarchs. Surely they could resonate with Rebekah’s and Isaac’s prayers receiving a reply on such a tarried timetable. Not for nothing is the most common prayer uttered in the psalms, “How long, O Lord?”

Laughter is sixty years old when Rebekah conceives.

Rather than a normal quickening, the Hebrew says the children “clashed together within her womb.” Only, Rebekah knows that she’s pregnant with twins. Rebekah knows only that something is amiss. At her age, it would be odd not to fret.

The wife of Laughter grows afraid.

And so she prays. She prays maybe the most common prayer ever prayed by absolutely everybody, “Why?”

“Why is this happening to me?”

And the Lord answers her!

Deus Dixit— And God spoke.

First, God gives Rebekah an explanation, “Two nations are in your womb.” But explanations are not what makes scripture hang together, and if you’ve come here today looking for answers you’ve come to the wrong place.

God gives her an explanation for the commotion in her belly.

Notice, the Lord also gives her a word about the future; that is, the Lord gives her a promise. A promise that offends an ancient people’s sense of justice. A promise that turns the kin and kingdoms of their world upside down. A promise that surely sounded like foolishness and a stumbling, for it is a promise that contradicts the eternal, natural law of primogeniture.

“The elder shall serve the younger,” the Lord promises Rebekah.

You know the story.

The twins are delivered from her, one after the other, the younger clutching his hairy elder’s heel. Just so they name them, Hairy (Esau) and Heel (Jacob). But long after Rebekah last held her boys in her arms, she still held onto this promise from God, “The elder will serve the younger.” According to the text, at least forty years pass. Her children are grown men. Esau’s a married man. And everything remains as the world would have it, according to the law.

Rebekah’s an old woman, still with this promise from God socked away like a ball of rubber bands or a cigar box of old movie stubs.

Then one day, Genesis 27 remembers for us, Laughter is a very old man and very blind and very much dying. Isaac summons Esau. It’s time. Isaac must put the law into action; the eldest will not assume the father’s place.

When Laughter’s wife hears her husband aims to bless Esau, suddenly she knows.

She recognizes the time has arrived for her to apply the promise.

She sees God gave her the promise all that time ago— forty years— in order for her to apply that promise now.

Rebekah realizes that the promise isn’t simply a word God gave.Rebekah realizes it’s a word that needs giving.No matter how much it will upset and offend.

Even though it will violate the law. Despite the cost.

So she conscripts her youngest into a scheme to fool Isaac into blessing him, insisting to the skeptical Jacob, “Let your curse be on me, my son…” She takes on to herself the scorn and punishment that will justly fall upon the child for his transgression because she knows— by faith, she knows— the promise God had spoken was now seeking its moment of application. Surely she knows too that it’s a promise Jacob in no way merits. Actually he’s already earned the opposite of such a promise.

The Bible hangs together christologically.

A month ago in Paradise, Texas, Tanner Lynn Horner was charged with kidnapping and murder. A FedEx driver, Horner snatched seven year old Athena Strand, who was in the care of her stepmother. He kidnapped her while he delivered packages to their address. Her body was found two days later. The justifiable rage in the community is such that his trial likely will be moved to another county or district.

Yet—

Athena’s grandfather, Mark Strand, acknowledging his anguish and what he would want to do were he allowed five minutes alone with his granddaughter’s murderer, issued a public declaration of forgiveness:

“This flesh, this man that I am, is bitterly angry, but there’s a gentle voice that continues to tell me I need to forgive him…if you stood that man before me right now…I would probably kill him…there’s not an ounce of me that wants to do this or say this but there is mercy in Jesus Christ even for him, even for him or not for any of us. Either we live by the grace of God in Jesus Christ and his shed blood or we do not live at all. I don’t want to do this or say this, but my spirit has heard God’s voice so right now I declare publicly that I forgive— and I will work on forgiving— this man, this monster. I pray that by my public declaration others will hold me accountable to my pledge. I do this to honor our precious Athena who knew no hate…”

Quite understandably, Mark Strand’s declaration of forgiveness offended and outraged members of his community as well as his own family. When asked how he could possibly offer forgiveness to a man who manifestly does not deserve it, Mark Strand replied:

“I’ve been hearing the Lord’s promise of the forgiveness of sins and the justification of the ungodly my whole life. I think now I was being prepared— the Lord was preparing me— to put that promise into action in just this terrible circumstance.”

The promise given to Rebekah in Genesis 25 leads to Rebekah’s deceit of her husband two chapters later. Rebekah’s deceit has long preoccupied interpreters. Can the covenant rely upon a lie? What about bearing false witness? Honoring thy husband? Does this mean we’re free from the obligation to truthfulness? The Protestant Reformers, however, were untroubled by this text.

Luther called it “the faithful deceit.”

Faithful because faith follows the promise not the law.

You obey a command. You trust a promise.

You can keep a rule without having any relationship with the rule-giver.

You can keep the sabbath. You can give to the poor. You can avoid cheating on your spouse. But it doesn’t make you a Christian. It makes you obedient. Or worse, “good.”

You can keep a law without having any relationship with the law-giver.You cannot trust a promise without having trust in the promise-maker.And you can only trust one whom you know and love.

Faithful deceit.

Faith follows the promise not the law.Faith follows the promise.

Even when, precisely when, it conflicts with the command.

Faith follows the promise.

Even when, particularly when, it offends: “How could you forgive that monster?!”

Faith follows the promise.

Even when, especially when, it upends: “The elder will serve the younger?! Our entire society is built on the first being first and the last being last.”

Faith follows the promise.

Even when, exactly when, it makes no sense whatsoever: “What do you mean because one man died to sin, all have died? Not only are we very much alive, we’re also still very much sinners.”

Faith follows the promise.

Rebekah puts the promise (“The elder shall serve the younger…”) above the law (“The elder will be served by the younger…”).

Day by day by day, year after year, for four decades, she clings to the promise until its moment of application arrives.

Says Luther:

“Rebekah gave thought to how she might be able to deceive her husband Isaac; her son Esau, and all who were in the house; for now she not obeying the rule or the law. Now she is obeying God, who transfers and dispenses contrary to the law. Therefore, Rebekah did not sin.”

Indeed, under the promise, the lie that would be sin becomes faith. Exactly because faith follows God’s promise and not the law, faithfulness can sometimes appear as a strange obedience.

Faith attaches itself to a thing (a promise— in word, water, wine, and bread).

Faith attaches itself to a thing that is still yet an utter nothing (word, water, wine and bread).

And faith WAITS.Until everything promised comes about.This is precisely what it means to walk by faith and not by sight or sense or commonsense. To walk by faith is to be carried through the present, by means of a graspable promise, towards a future that is yet hidden but nevertheless certain.

To walk by faith is to be carried through the present by a promise towards a future that is as good as guaranteed.

Many months after that afternoon when the bishop paid him a visit, Tom Radney was climbing up the courthouse steps for a civil rights case in which he was the advocate. Racists and rabble rousers crowded the stairs. They taunted and jeered and threatened him.

“Tom Radney we’re going to get you!”

“Tom Radney we’re going to make you pay!”

“Tom Radney we’re going to make you wish you’d never done this!”

Radney stopped on the courthouse steps, in the midst of them, and he remembered the promise the bishop had prayed over him, the promise of the Lord’s strength and protection.

“Tom Radney, we’re going to kill you!”

Tom Radney remembered the promise, and he turned to the mob.

“No, you ain’t. I’m going to be fine.”

Then he walked into the courthouse. And into an unseen but assured future.

Faith follows the promise.

To walk by faith is to grab ahold of God’s promise and let it carry you through your present days towards a certain future you cannot see.

And you’re no different than Rebekah.

There is no distinction between the world of the Bible and our world. There’s just the world and the God who from before the creation of the world elected not to be God without the world. There is no distinction between the world of the Bible and this world.

Like Rebekah, God speaks promises to you too.

We said just a bit ago, “This is the Word of God for the People of God.”

We don’t mean that as, like, a metaphor.

The Almighty Father who spoke a promise to Rebekah still speaks, by his Holy Spirit, through the Son who is his Word. The Living Lord is loquacious, and he loves to speak promises. To Rebekah and Jacob. To Tom Radney and Mark Strand. To you.

Based on his word in Genesis, the Lord’s promise to you today might be:

Yes, you have prayed for weeks upon weeks or years upon years, you have prayed holes in the carpet, you have prayed for healing or reconciliation, for sobriety or children or faith, to no apparent avail.

To you, today, the promise may be that, no, the Lord’s ears are not shut to you. The Lord who heard Laughter’s prayers for forty years hears your prayers too and likewise he will heed them. He is just waiting for you to let go; so that, he is the only solution to your problem.

Or, based on this word, the Lord’s promise might be:

Like Rebekah, you’ve committed some deception. Maybe even, like Rebekah, that lie was against your spouse. And perhaps, like Rebekah, you caught your children up in it too. But unlike Rebekah, yours was not a faithful deceit.

To you, today, the promise may be that if God chose Jacob in utero for salvation, before Jacob could do any bad (or any good) then it’s true indeed that in the God of Jesus Christ there is no condemnation.

Or, based on this word, God’s promise today could be:

Like Laughter and his wife, you’re old. The life you’ve had is not the life you wanted. You’re worse than past your prime, you fear. You’re past your purpose.

To you, today, the promise is that God loves to commandeer people like you just as much as he likes to call sinners. And the good news for you is that you’re both. So, more so than anyone, you should watch out.

Or quite possibly, you don’t think this business has anything to do with you.

Well, neither did Esau.

Therefore, the promise is that even you— unbelieving, unwilling you— are a necessary character in God’s drama of salvation.

Faith follows the promise.

To walk by faith is to grab ahold of God’s promise and let it carry you into the future, free and unafraid.

And today, as with every day, the promise the Lord speaks to every last one of us, whether we are old or unbelieving, the promise he makes tangible so that we can grasp ahold of it and take it and eat it and drink it— the promise from God, today, to you, for you: your sins are forgiven.

All of them.

Even that one.

So come to the table.

Grab onto a pardon that is better even than the promise of the Lord’s protection. But before you come to the table, beware. The Lord doesn’t give you a promise without expecting you to apply it when the time presents itself.

Even as you come forward to the Lord with hands held out, be ready.

The Lord is surely coming with the moment for you to say, “I forgive you.”

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 1, 2023

God Gives a Feck

Thanks for reading Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Luke 2.21-35

In Martin McDonagh’s recent film The Banshees of Inisherin, actor Brendan Gleeson plays Colm Doherty, an amateur musician in the clutches of a crippling melancholia and existential dread. Colm lives on a a sparsely populated island off the coast of Ireland, close enough to the mainland to hear gunshots traded during the early years of “The Troubles.” Gripped by despair over the fleetingness of time and the meaninglessness of life, Doherty hopes his music somehow will justify his existence and insure that the future will remember him.

Thus Colm vows to waste no more of his precious time in the company of his kind-hearted but “dull” friend, Pádraig. Colm, literally, spites himself in order to cut off his former friend. Colm’s shocking ultimatum leads inadvertently to the death of Padraig’s last remaining companion, his pet donkey Jenny. While Colm shows no remorse over the cruel way he suddenly shunned his former pub mate, Colm does regret that his despondent tantrum killed Jenny the donkey.

Genuinely vexed, Colm confesses his transgression to a feckless priest who comes to the fictional island on Sundays in order to dispense the sacraments.

"How's the despair?" the priest asks Colm.

Colm replies it's been not so great lately.

”But you're not going to do anything about it, right?"

Colm replies that no, he's not going to do anything about it.

But the reply hangs in the air.

Later Colm confesses to Jenny’s accidental killing.