Jason Micheli's Blog, page 125

March 18, 2018

Modern Reformation Magazine: A Wrath-Less God has Victims

Modern Reformation Magazine has featured my essay on atonement and wrath about my friend Brian Stolarz’s work freeing Alfred Dewayne Brown, who is also now my friend, from death row in Texas.

Modern Reformation Magazine has featured my essay on atonement and wrath about my friend Brian Stolarz’s work freeing Alfred Dewayne Brown, who is also now my friend, from death row in Texas.

You can read Brian’s book Grace and Justice here. The theme of wrath as it relates to Dewayne’s case is even more pertinent now than when I wrote this as the Houston Chronicle recently broke the story that the DA in the case intentionally withheld exculpatory evidence from the very beginning of the case. To wit, the institutional racism was such they so didn’t give a damn about an innocent black man’s life they were willing to damn him to death.

Like many upper middle class mainline Protestants, which is to say white Christians, I’ve long taken issue with the concept of divine wrath, believing it to conflict with the God whose most determinative attribute is Goodness itself. Whenever I’ve pondered the possibility of God’s anger I’ve invariably thought about it directed at me. I’m no saint, sure, but I’m no great sinner either. The notion that God’s wrath could be fixed upon me made God seem loathsome to me, a god not God.

I’ve changed my mind about God’s wrath. Or, rather, my friend, Brian Stolarz has changed my mind. When reflecting upon the category of divine wrath, thanks to Brian, I no longer think of myself. My mind goes instead to Alfred Dewayne Brown, Brian’s client.

Brian spent a decade working to free an innocent man, Alfred Dwayne Brown, from death row in Texas. Dewayne had been convicted of a cop-killing in Houston. Despite a lack of any forensic evidence, he was sentenced to be killed by the State on death row.

Brown’s IQ of 67, qualifying him as mentally handicapped, was ginned up to 70 by the state doctor in order to qualify him for execution. This wasn’t the only example of prosecutorial abuse in the case; in fact, the evidence which could’ve proved his alibi was hidden by prosecutors and only discovered fortuitously by Brian, years later. Dewayne was released by the state in the summer of 2017.

Meanwhile, Dewayne has a civil rights case pending to seek restitution for the injustice done to him. To seek rectification, biblically speaking.

I spent about a half hour alone with Dewayne this fall as we waited for his presentation, with Brian, to a group of law students. I’ve worked in a prison as a chaplain and interacted with prisoners in solitary and on death row. Like my friend, Brian, I have a good BS radar. Dewayne was unlike the prisoners I’ve met. My immediate reaction from spending time with him was how difficult it was for me to fathom any one fathoming him committing the crime of which he was accused. My second reaction was to feel overwhelmed by Dewayne’s expressions of forgiveness over the wrongs done to him by crooked cops and lawyers, a prejudiced system, and an indifferent society. ‘I’ve forgiven all that,’ Dewayne told me in the same sort of classroom where lawyers who had turned a blind eye to his innocence were once trained into a supposedly blind justice system.

Here’s the crux of the matter, and I use that word very literally: Dewayne is allowed to express forgiveness about the crimes done to him. But, as a Christian, I am not so permitted. Neither are you. If we told Dewayne, for example, that he should forgive and forget, then he would be justified in kicking in our sanctimonious teeth.

In The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, Fleming Rutledge points out in her third chapter, “The Question of Justice,” we commonly suppose that Christianity is primarily about forgiveness. Jesus, after all, told his disciples they were to forgive upwards of 490 times. From the cross Jesus petitioned for the Father’s forgiveness towards us who knew exactly what we were doing. Forgiveness is cemented into the prayer Jesus taught his disciples.

Nonetheless, to reduce the message of Christianity to forgiveness is to ignore what scripture claims transpires upon the cross. The cross is more properly about God working justice.

The most fulsome meaning of ‘righteousness,’ Rutledge reminds her readers, is ‘justice’ understood not only as a noun but as an active, reality-making verb. Though righteousness often sounds to us as a vague spiritual attribute, the original meaning couldn’t be more this-worldly. Justice, don’t forget, is the subject of Isaiah’s foreshadowing of the coming Messiah. Justice is the dominant theme in Mary’s Magnificat, and justice is the word Jesus chooses to preach for his first sermon in Nazareth.

To mute Christianity into a message about forgiveness is to sever Jesus’ cross from the Old Testament prophets who first anticipated and longed for an apocalyptic invasion from their God. And it’s to suggest that on the cross Jesus works something other than how both his mother and he construed his purpose.

Rather than forgiveness, Rutledge asserts, we see on the cross God’s wrath poured out against Sin with a capital S and the upon the systems (Paul would say the Powers) created by Sin. On the correspondence between Sin as injustice and God’s wrath, Rutledge cites Isaiah’s initial chapter:

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the Lord; I have had enough of burnt-offerings… bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity. Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doings from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow… Therefore says the Sovereign, the Lord of hosts, the Mighty One of Israel: Ah, I will pour out my wrath on my enemies, and avenge myself on my foes! I will turn my hand against you…

Christianly speaking, forgiveness is a vapid, meaningless concept apart from justice. The cross is a sign that something in the world is terribly wrong and needs to be put right. The Sin-responsible injustice of the world requires rectification (Rutledge’s preferred translation for ‘righteousness’).

Only God can right what’s wrong, and the cross is how God chooses to do it. God pours out himself into Jesus and then, on the cross, God pours out his wrath against Jesus and, in doing so, upon the Sin that unjustly nailed him there.

Summarizing the prophets’ word of divine wrath in light of the cross, Rutledge writes:

Because justice is such a central part of God’s nature, he has declared enmity against every form of injustice. His wrath will come upon those who have exploited the poor and weak; he will not permit his purpose to be subverted. [CITE]

Despite the queasiness God’s wrath invokes among mainline and liberal Protestants, how could one think of Alfred Dewayne Brown and not hear the above lines as good news? The example of Dewayne Brown points out the problem with the popular disavowal of divine anger; namely, what we (in power) find repugnant has been a source of hope and empowerment to the oppressed peoples of the world.

The wrath of God is not an artifactual belief to be embarrassed over, it is the always timely good news that the outrage we feel over the world’s injustice is ‘first of all outrage in the heart of God,’ which means wrath is not a contradiction of God’s goodness but is the steadfast outworking of it.

The biblical picture of God’s anger, Rutledge shows, is different from the caricature of a petulant, arbitrary god so often conjured when divine wrath is considered in the abstract. ‘The wrath of God,’ she writes, ‘is not an emotion that flares up from time to time, as though God had temper tantrums; it is a way of describing his absolute enmity against all wrong and his coming to set matters right.’ Put so and understood rightly, it’s actually the non-angry god who appears morally distasteful, for ‘a non-indignant God would be an accomplice in injustice, deception, and violence.’

Maybe, I can’t help but wonder, we prefer that god, the one who is a passive accomplice to injustice, because, on some subconscious level, that is what we know ourselves to be: accomplices to injustice.

I did no direct wrong to Dewayne Brown, for example, but on most days I’m indifferent to others on death row like him. The inky facts of injustice are all over my newspaper but I don’t do anything about it. I try not to see color even as I neglect to see it through the prism of the cross. I’m not an oppressor but I am most definitely an accomplice. Odds are, so are you.

Perhaps that is what is truly threatening to so many of us about a wrathful God; we know that the Bible’s ire is fixed not so much on the hands-on oppressors as it is against the indifference of the masses.

As Rutledge points out:

,,,in the bible, the idolatry and negligence of groups en masse receive most of the attention, from Amos’ withering depiction of rich suburban housewives (Amos 4.1) to Jesus’ lament over Jerusalem (Luke 13.34) to James’ rebuke of an insensitive local congregation (James 2.2-8).

As Brett Dennen puts it in his song, ‘Ain’t No Reason,’ slavery is stitched into every fiber of our clothes. We’re implicated in the world’s injustice even if we like to think ourselves not guilty of it. Rutledge believes this explains why so much of popular Christianity in America projects a distorted view of reality; by that, she means sentimental. Our escapist mentality protects us not just from the unendurable aspects of life in the world but also from the burden of any responsibility for them.

Such sentimentality, however popular and apparently harmless, has its victims. They have names like Alfred Dewayne Brown.

Having a friend like Brian and having met someone like Dewayne, I’m convinced we risk something precious when we jettison God’s wrath from our Christianity. We risk losing our own outrage.

Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion might’ve convinced all on its own:

If, when we see an injustice, our blood does not boil at some point, we have not yet understood the depths of God. It depends on what outrages us. To be outraged on behalf of oneself or one’s own group alone is to be human, but it is not to participate in Christ.

To be outraged and to take action on behalf of the voiceless and oppressed, however, is to do the work of God.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 16, 2018

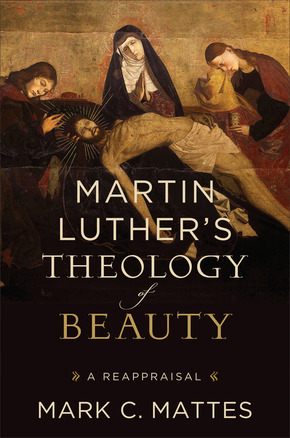

Episode #143 – Mark Mattes: Martin Luther’s Theology of Beauty (?)

The Protestant Reformer Martin Luther once remarked that God in Jesus Christ gets so close to the muck and mire of our lives that “his skin smokes.” That is, the incarnation is more than the cute baby Jesus in his golden fleece diapers; it’s like the steaming pile of…you get the picture…that our life so often feels. Is that in any way beautiful?

The Protestant Reformer Martin Luther once remarked that God in Jesus Christ gets so close to the muck and mire of our lives that “his skin smokes.” That is, the incarnation is more than the cute baby Jesus in his golden fleece diapers; it’s like the steaming pile of…you get the picture…that our life so often feels. Is that in any way beautiful?

Luther, more than any other theologian, focuses on the centrality of the crucified Christ for you? Is the naked and shamed Jesus nailed to a tree in any intelligible way beautiful?

In this episode, I talk with Dr. Mark Mattes about his new book, Martin Luther’s Theology of Beauty. He reflects on how Luther’s reconceptualizing beauty can inform us in how we think about what constitutes a beautiful life, how we parent and love. Along the way, he pushes back on frequent podcast guest David Bentley Hart and also helps this United Methodist think through how to square Wesley’s notion of sanctification and perfection with Luther’s insistence that we always remain sinners who nonetheless already possess Christ’s perfect righteousness.

In this episode, I talk with Dr. Mark Mattes about his new book, Martin Luther’s Theology of Beauty. He reflects on how Luther’s reconceptualizing beauty can inform us in how we think about what constitutes a beautiful life, how we parent and love. Along the way, he pushes back on frequent podcast guest David Bentley Hart and also helps this United Methodist think through how to square Wesley’s notion of sanctification and perfection with Luther’s insistence that we always remain sinners who nonetheless already possess Christ’s perfect righteousness.

If you’re receiving this by email and the player doesn’t come up on your screen, you can find the episode at www.crackersandgrapejuice.com.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Help support the show! This ain’t free or easy but it’s cheap to pitch in.

Click here to become a patron of the podcasts

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 12, 2018

Episode #142 – Andy Root: Obsessed with Growing Young

Joined by Rev. Drew Colby, Teer and Jason interview Dr. Andy Root of Luther Seminary and author of “Faith Formation in a Secular Age: Responding to the Church’s Obsession with Youthfulness.” Andy’s book is an engagement on the implications for ministry, particularly youth ministry, posed by the philosopher Charles Taylor’s monumental work the Secular Age. Also in this episode are the cultured tunes of whatever classical station Teer’s mic were picking up during the interview.

Joined by Rev. Drew Colby, Teer and Jason interview Dr. Andy Root of Luther Seminary and author of “Faith Formation in a Secular Age: Responding to the Church’s Obsession with Youthfulness.” Andy’s book is an engagement on the implications for ministry, particularly youth ministry, posed by the philosopher Charles Taylor’s monumental work the Secular Age. Also in this episode are the cultured tunes of whatever classical station Teer’s mic were picking up during the interview.If you’re receiving this by email and the player doesn’t come up on your screen, you can find the episode at www.crackersandgrapejuice.com.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Help support the show! This ain’t free or easy but it’s cheap to pitch in.

Click here to become a patron of the podcasts

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 6, 2018

Taking the Bible Seriously Means Reading It Figurally

Here is my article in the Christian Century Magazine about the theologian Ephraim Radner’s book Time and the Word.

When scripture refers to something in the “past,” this is itself to raise a question about the nature of our relationship with God. . . . From a theological point of view, we must wonder if “the past” to which Scripture refers is not simply a divine mode of the present, whose nature exceeds comprehension even as its moral demands can never be evaded. And this question, raised and answered if only cautiously and uncertainly, is precisely what lies behind the straightforward figural reading.

Click over to read the full essay:

https://www.christiancentury.org/revi...

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 5, 2018

Temple Tantrum

Mt. Olivet UMC – Lent 3: John 2

I want to thank you all for taking the time out of your Oscar Party preparations to be here this morning. I mean, Teer Hardy didn’t get a hipster haircut or start wearing beard oil until he became a pastor here at Mt. Olivet so I assume that means you’re a sophisticated, culturally savvy bunch of cinephiles.

For an erudite community of aesthetes like yourselves, coming to church on the dawn of Oscar night is akin to worshipping the Sunday after Christmas, a day when only the old, lonely guy from Home Alone attends church. Oscar Sunday is like the Sunday of Thanksgiving or Memorial Day.

Just for being here this morning, you deserve a gilded statue all your own.

I had a special Oscar-themed outfit I was going to wear for you this morning, but my wife thought it showed a little too much nipple for a guest preaching gig. Plus, I’ve not shaved my chest in days.

Show of hands, how many of you are planning to watch the Oscars tonight?

Show of hands, how many of you have seen the Vegas favorite Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri? How many of you have seen the Darkest Hour? The Post? Dunkirk? How many of you have seen the critical darling the PT Anderson flick The Phantom Thread?

How many of you are lying?

Every Oscar season I think of an article I read in Slate Magazine 10 years ago.

Back in 2008, when Netflix was not yet a streamed-movie service, reporter John Swansburg investigated which mail-order Netflix movies languished the longest on customers’ coffee tables and television consoles.

Swansburg discovered that it was Hotel Rwanda.

Even though at the time Hotel Rwanda was the 10th most popular rental among Netflix’s 8.4 million customers, only a fraction of people ever got around to watching it.

In fact, Steve Swasey, spokesman for Netflix, confessed to having had a copy of Hotel Rwanda on his nightstand for 2 years without having watched it, which is about how long we left it on our nightstand before sending it back, unwatched.

Other Oscar-bait films that people requested by mail but never got around to watching included No Country for Old Men, There Will be Blood, Pan’s Labyrinth (made by this year’s Best Director favorite, Guillermo del Toro) and Last King of Scotland about dictator Idi Amin.

It goes without saying that Schindler’s List and the English Patient were also perennial dust collectors.

Turns out many of Netflix’s most popularly requested movies never left their red pre-paid postage sleeves. Their most requested films are also some of their least watched films.

As Swansburg notes, you add a movie like Hotel Rwanda to your Netflix queue because you don’t want to be thought a bad person who turns a blind eye to unspeakable tragedy.”

Truthfully, most of us don’t want to watch a movie about genocide, we’re too tired for aThere Will be Blood, and we’re already too depressed for a No Country for Old Men but neither do we want to appear as the sort of people not interested in watching those worthwhile films.

We don’t want to watch movies like Hotel Rwanda, but we do not want to be perceived as people who do not watch movies like Hotel Rwanda.

Unlike political pollsters who have difficulty prognosticating how prejudiced we’ll prove to be behind the voting booth curtain, Netflix knows the truth about us.

We’re not who we pretend to be.

We’re not as sophisticated or concerned or altruistic or woke as we feign.

Our queue reveals more about us than our feed.

Netflix knows that, when it comes to social justice, we’d rather hashtag than roll up our sleeves.

Netflix knows we’re more likely to stick a sentiment on our bumper than we are to know an honest-to-goodness human-style poor person by name.

Netflix knows that even though we have 12 Years a Slave sitting in our queue, we’re just as likely as anyone to cross the street when we see a black man in a hoodie walking our way.

Netflix knows that no matter what we tweet or pin or like, Vegas-odds are we spend more on our gym memberships- we spend more on Netflix– than we do on church or charity.

Netflix knows we’re all going to add The Florida Project to our queues when it becomes available because we all want to be perceived (and to perceive ourselves) as the sort of person who watches a film like The Florida Project.

But, odds are, we won’t.

Watch it.

Because, after a day of dealing with your boss and yelling at your kids about homework, who really wants to watch a movie about child homelessness?

For example, I’ve had The Hurt Locker in my Netflix queue for years, but I’ve never watched it; meanwhile, I’ve seen Sahara, the Matthew McConaughey and Penelope Cruz straight-to-video action movie about Confederate gold and Civil War Ironclads in Africa at least 60 times.

And I love it.

Netflix– it’s just one example of what we do across our lives.

We pretend and we perform and we prevaricate.

We crop out our true selves and filter it through a social media sheen.

We virtue signal from behind the masks we wear.

We project a false self out onto the world.

Which makes it ironic that the one theological conviction our culture has conditioned you into believing is that God loves you just the way you are.

You don’t even love you just the way you are. You wish you were a Hotel Rwanda, Phantom Thread kind of person.

You don’t even love you just the way you are, yet our culture has conditioned you into thinking that God is just like Billy Joel.

God accepts you just the way you are, which- again- is ironic because it turns out Billy Joel didn’t love Christie Brinkley just the way she was. He went searching for something else from someone else, which maybe makes him someone who shouldn’t be accepted just the way he is either.

I don’t mean to pile on Billy Joel; I know some of you Baby Boomers love him more than Jesus. I don’t mean to pile on Billy Joel or you.

Lord knows- or least my wife knows, I’m no better than most of you. Look, I know guest preachers, like Oscar hosts, are supposed to charm and delight. I don’t mean to smote you with fire and brimstone. But today in John’s Gospel- Jesus doesn’t just cleanse the Temple, whipping the money-changers and turning over their tables.

Notice- in the midst of his Temple tantrum, Jesus refers to himself as the Temple: “Destroy this Temple and in three days I’ll raise it up.”

In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, by contrast, this statement is put on the lips of Jesus’ accusers at his trial. What’s more, his accusers edit the statement, claiming Jesus said: “I will destroy this Temple and in three days I will build another…”

In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the accusers make Jesus the agent of destruction but today, in John’s Gospel, Jesus makes us the agents of destruction.

Which makes Jesus the Temple. And if Jesus is the Temple then it makes sense today to point out the basic presupposition behind the Temple.

It’s this:

You aren’t acceptable before the Lord just the way you are.

The gap between your sinfulness and the holiness of God is too great. You aren’t acceptable before the Lord just the way you are. You have to be rendered acceptable. You have to be made acceptable, again and again.

That’s the assumption that animates all the action at the Temple.

And that’s the thread that stitches together the Bible by which Jesus understood himself and understood his death and understood himself as the Temple.

You have to go back to Jesus’ Bible, to the Book of Leviticus, which begins with God’s instructions for a sin-guilt offering: “The petitioner is to make his offering at the door of the tent of meeting so that he may be accepted before the Lord.”

The worshipper, instructs God to Moses, should offer a male from the herd, a male without blemish; he shall offer it at the door of the tent of meeting, what becomes the veil to the holy of holies when the temple in Jerusalem is built.

God instructs Moses that the sinner is to lay his hand upon the head of the offered animal and “it shall be accepted as an atonement for him.”

For him. On his behalf. In his place.

The offered animal, as a gift from God given back to God, is a vicarious representative of the sinner. The offered animal becomes a substitute for the person seeking forgiveness. The blood of the animal conveys the cost, both what your sin costs others and what your atonement costs God.

God intended the entire system of sacrifice in the Old Testament to prevent his People from thinking that unwitting sin doesn’t count, that it can just be forgiven and set aside as though nothing happened, as though no damage was done.

Those sacrifices, done again and again on a regular basis to atone for sin, were offered at the door of the tent of meeting. Outside.

But once a year a representative of all the People, the high priest, would venture beyond the door, into the holy of holies, to draw near to the presence of God and ask God to remove his people’s sins, their collective sin, so that they might be made acceptable before the Lord.

Acceptable for their relationship with the Lord.

After following every detail of every preparatory ritual, before God, the high priest lays both his hands on the head of a goat and confesses onto it, transfers onto it, the iniquity of God’s People.

And after the high priest’s work was finished, the goat would bear the people’s sin away in to the godforsaken wilderness; so that, now, until next Yom Kippur, nothing can separate them from the love of God.

———————-

It’s easy for us with our un-Jewish eyes to see this Old Testament God behind the veil as alien from the New Testament God we think we know.

In Jesus’ Bible it’s true we’re not acceptable before God just the way we are but it’s God himself who gives us the means not to remain just the way we are. So these sacrifices in the Old Testament are not the opposite of the grace we find in the New. They are grace.

As Christians we’re not to see them as alien rituals or inadequate even.

We’re meant to see them as preparation. We’re meant to see them as God’s way of preparing his People for a single, perfect sacrifice.

—————————

But get this- all the sacrifices of the Old Testament they were to atone for unintended sin. There is no sacrifice, no mechanism, in the Old Testament to atone for the sin you committed on purpose. Deliberately. Or, at least, knowingly.

Not one.

By contrast, the New Testament Book of Hebrews, which frames Jesus just as Jesus frames himself here in John 2- as the Temple, describes Jesus’ death as the sacrifice for sin.

All. One sacrifice. Offered once. For all.

Ephapax is the word: “once for all.”

For unwitting sin and for willful sin. For just the way you are and all the ways you aren’t who you pretend to be.

———————-

Not only is Jesus the true Temple. Not only is he the sacrifice to end all sacrifices for sin. He’s our Great High Priest.

Aaron all the other high priests from the tribe of Levi they went beyond the veil alone and they came back alone.

But this Great High Priest in his flesh, his flesh of our flesh, he carries all of us- all of humanity- to the mercy seat of God, says the Book of Hebrews.

He draws near to the Holy Father and, in him, all of us draw near too. And there this Great High Priest offers a gift. Not a calf or a goat or grain. But a gift so precious, so superabundant, as to be perfect.

A gift that can’t be reciprocated, it can only redound to others. He offers a gift exceeding our every debt. Such that no sacrifice ever need be offered again. His own life. His own unblemished life.

We choose to put him on a cross, but this Great High Priest chooses on it to gift himself as sacrifice, to sprinkle his own blood on the mercy seat of the cross.

To make atonement.

Once for all so that all of us can be free and unafraid before the holy love of God just the way we are.

——————————-

Ironically, Atonement, the high-brow, arthouse film starring Keira Knightley and based on the award-winning novel by Ian McEwan, has sat idle and unwatched in my Netflix queue since 2007.

I put it in my queue after it cleaned up at the Oscars.

Meanwhile, I’ve watched all 7 seasons of Californication 3 separate times, and just last night I wasted 2 hours of my life watching 3,000 Miles to Graceland starring Kevin Costner and Christian Slater and Courtney Cox,

(And I loved it).

And last night too, I was short with my kids.

And I only half-listened to my wife as she told me about her day.

And I didn’t call a friend who I know is hurting and then I told myself I’d forgotten, but I hadn’t.

And after dinner I tossed the recycling into the trashcan because it was too chilly to take it outside.

Martin Luther said the cross frees us to cut out our BS and call a thing what it is.

So here goes: Despite how sexy I am, I’m not anyone’s idea of a leading man. I’m no hero. I’m certainly no saint.

But I don’t have to be. There’s no role I have to play. There’s no mask I need to wear. There’s no character I need to project out onto the world other than the broken, butt-headed but baptized person I am.

Because Jesus Christ has taken on the role of our Great High Priest…

Because God judges me not according to my sins

But according to Christ’s perfect sacrifice…

I’m free.

Christ’s sacrifice upon the cross, the Apostle Paul says, sets us free from performing the obligations of the Law.

And that frees us from the obligation to perform.

It frees us from the obligation to pretend. It frees us from the burden of projecting a false more faithful self. The cross frees me to be me. The cross frees me to play no other role than me because, honestly, if anyone were to play me it would probably be Steve Buschemi. Or that creep Willem Defoe.

The cross frees me to be me, unafraid and unashamed

Because my life is not the good news- and that’s good news.

You’re free to be you, just the way you are, like Adam before the apple: naked and unashamed.

Because you are not what you do.

And you are not what you have done.

You are what Christ, our Great High Priest, has done in the Temple that is his Body by his blood sprinkled on the mercy seat of a cross.

Because his sacrifice is perfect, once-for-all:

There is nothing you can do to make God love you less.

And there is nothing you can do to make God love you more.

That’s called the Gospel.

And you don’t have to wait in any queue for it.

You don’t have to earn it. You don’t have to deserve it.

You certainly don’t need a fake ID to purchase it.

It’s yours. By faith. And it’s free.

Just the way you are because of the way he was all the way unto a cross.

Ironically, this free gift alone has the power to transform you into more than just the way you are.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 2, 2018

Episode 141 – Mark Lilla: After Identity Politics

“If progressives want to advance their agenda, they need to relearn how to win elections.”

“If progressives want to advance their agenda, they need to relearn how to win elections.”

In this episode, taped back in the late summer, I talk with Dr. Mark Lilla about his book The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics.

Mark Lilla is Professor of the Humanities at Columbia University and a prizewinning essayist for the New York Review of Books and other publications worldwide. His books include The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics; The Shipwrecked Mind: On Political Reaction; The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics, and the Modern West; and The Reckless Mind: Intellectuals in Politics. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. VISIT MARKLILLA.COM.

If you’re receiving this by email and the player doesn’t come up on your screen, you can find the episode at www.crackersandgrapejuice.com.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Help support the show! This ain’t free or easy but it’s cheap to pitch in.

Click here to become a patron of the podcasts

Follow @cmsvoteup

February 28, 2018

(Her)Men*You*tics: Kenosis

We’re working our way through the alphabet one stained glass word at a time.

We’re working our way through the alphabet one stained glass word at a time.

In this episode we consider ‘Kenosis‘ i.e. how God poured himself into human form in the incarnation, and/or how Jesus emptied himself of divinity (like omniscience and omnipotence). It’s the perfect word for Lent!

But mostly we talk about what human qualities Jesus experienced, the good and the bad. And Jason swears that, if Scarlet Johanssen gave him directions, he would follow them.

If you’re receiving this by email and the player doesn’t come up on your screen, you can find the episode at www.crackersandgrapejuice.com.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Help support the show! This ain’t free or easy but it’s cheap to pitch in.

Click here to become a patron of the podcasts

Follow @cmsvoteup

February 27, 2018

Patience

Here’s a sermon on Mark 8.31-38 from my friend and colleague, Drew VanDyke Colby:

Did you know that here at St. Stephen’s United Methodist Church we have a discipleship plan? We do! When we first started to write down how it is that disciples become disciples at St. Stephen’s we were sure that we wanted something special. We were Northern Virginia people in a Northern Virginia church, we wanted the best plan to make the best disciples. At least I did…

I wanted to be able to greet new people and say, welcome to St. Stephen’s a place where God isn’t just an angry dude in the sky who wishes you would come to church more often. No, here God is the one who has saved the world from sin and evil and death. Has saved you from this. AND has saved you for something: which is discipleship. Christ in his cross has invited you to get behind him and follow him into the perfect love of God and neighbor. I wanted to be able to say, we’re different, and we have a plan for you! And I wanted it on the website, and in the welcome center, and in neighborhood mailings, and roadside banners. I was pumped!

The threat here for Northern Virginia people in a Northern Virginia church is that what’s intended as a gift to be received will quickly become another ladder to climb, and another achievement to accomplish. If you were to describe the posture of a Northern Virginian you might name things like hard-working, efficient, results-driven, busy, upwardly mobile, and in traffic. So, In order to avoid a posture towards the God of upward mobility, we name in our plan the postures of Christ instead. Postures we believe Christ welcomes us into as a way to get behind him and follow. This Lent we are looking for these postures of Christ in the scriptures each week. We looked at humility on Ash Wednesday with Pastor Abi. And last week Pastor Mark tried to convince us that the posture of self-control was fun. I actually think he did a good job.

In fact, we’ve asked folks to share with us some artwork on these postures. [pictures on screen] This one by Gabby Ducharme is called “Ball of Events” with the explanation “we encounter many colors of trouble as our life rolls on. This develops patience. And that is the posture of Christ we look for this week: patience.

One day Jesus and the disciples settle in for a chat. Jesus says to them, “who are people saying that I am?” They say “some say Elijah, others say John the Baptist, others say one of the other prophets.” Then Jesus says, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter, our idiot-in-chief, says “You are the Messiah, the Christ.” Peter is right. Jesus tells them not to spread this around because, the timing isn’t right. It’s not time yet for that to be revealed. And then Jesus talks about what it really means to be the Messiah, the Christ, also known as the Son of Man. Here is what he says it entails.

A reading from the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Mark:

Then he began to teach them that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again. He said all this quite openly. And Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him. (The word here is even stronger than that. He’s berating Jesus)

But turning and looking at his disciples, Jesus rebuked Peter and said, “Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.”

He called the crowd with his disciples, and said to them, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it. For what will it profit them to gain the whole world and forfeit their life? Indeed, what can they give in return for their life? Those who are ashamed of me and of my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, of them the Son of Man will also be ashamed when he comes in the glory of his Father with the holy angels.”

The Word of the Lord

Peter messed up. We should not be shocked. He had the best of intentions. He thought that the Messiah, the Christ was the one who was going to Make Israel Great Again, by any means necessary. Peter and the disciples had planned to be part of a winning revolution, and they were looking for a guy who would overtake this corrupt government and throw a big military parade in the capital as he took his throne. Peter and the other disciples were walking around strapped, with swords at the ready at Jesus’ signal to cut off some ears and start the revolution.

So, when the leader of their movement says, look guys, I’m gonna lose, Peter’s instinct was to say, like hell you are! We’re destined for glory, there is no way I’m letting you lead us to suffering. And Jesus whips back, “Get thee behind me, Satan!”

And finally we see Jesus behave like a human! Finally, Jesus loses his patience, just like we do. Or does he? What if this is actually not a story of Jesus losing his patience, but of Jesus exhibiting patience.

Not just the patience of a teacher with a distracting disciple; but a bigger picture patience. The patience of one who is willing to suffer, and endure discomfort, because he trusts in something bigger. Do you believe in that kind of patience? I do. And actually, it’s a very old Christian tradition. Don’t believe me? Ask an African.

Picture Africa. It’s the year two-hundred-four. The church there has no missionaries, they have no evangelists, they don’t even use the word evangelism. They have no neighborhood mailings, or eggstravaganzas, or welcome centers, or websites, or google ads, or roadside banners. The general public, interested parties, would-be visitors who are curious about becoming Christians are not even allowed in worship. Members only. To top it all off, the church is either barely tolerated by the government, or actively under threat. And in these conditions in Africa, in 204, the church is growing like wild flowers.

Scholars disagree on the actual numbers; but it’s clear that the growth was staggering. And in Africa, in the year 204, one of the leaders of this growing church was named Turtullian. And when he sits down to put into writing what makes the church the church, what does he write? A treatise called “On Patience.”

In it he first admits he has none, and gravels at the feet of Jesus, the only one who does. Then he explains that this is one of the greatest gifts that awaits us in Christ is a capacity for patience, and in fact, their survival as church can be owed to his patience in them. See, Turtullian is writing to Christians who are being jailed and killed. It was a time when your neighbor could find out that you went to bible study and turn you in to the authorities. And what was Turtullian saying to them? Stand up? FIght back? No. He was saying, “Patience. Have patience. It’s free. It comes from Christ.” In more specific terms, just so you’re not confused, what he’s really saying is, “Be willing to suffer for this. Suffer. It’s okay. It comes from Christ, and in a sense, Christ comes to us in suffering.” He writes, “When God’s Spirit descends, then Patience accompanies Him indivisibly.” And “Patience is hope with the lamp lit – or Patience is hope with the lights turned on.”

Fast forward another 50 years. Cyprian, an African, and a bishop of the church writes another treatise, On the Good of Patience. Then fast forward another hundred and fifty years. Augustine of Hippo, an African, writes his teaching On Patience.

For the church in its first few centuries, under persecution, and before finding its way to cultural power, the church was growing and growing, and if you asked its leaders why, they said, it’s because we have been given the patience of Christ.

To be clear, we are not talking here just about the patience you and I lack in traffic, or in the grocery line, or when we’re waiting on someone to reply to a very important text. No, this is big-picture patience. Patience in the midst of suffering like cancer. Like estrangement. Like prolonged conflict. Like perpetual war. Like profound segregation. Patience when the future is unclear. Patience in the midst of suffering like the suffering Christ was about to endure when Peter tried to stop him.

If you’re like me, when you’re in that kind of situation, everything from bad traffic to systemic injustice, if you’re like me, you’d like to fix it. Now. Demand. Protest. March. And the Spirit very well may be behind that; who am I to say it’s not.

But, we also have another well-established tradition of what some Christians have always been able to do in situations like this: it is patience. Don’t believe me? ask an African. Because what our African ancestors of the faith tell us is that there is no suffering we can endure that Christ will not endure with us or has not already endured for us.

Still don’t believe me? Ask an African-American. Just as our generous God spoke through the church in Africa in its first 500 years. God has also spoken in the last 500 years through the descendants of enslaved Africans in our own country. In both cases, through the faithful of African descent, Christ has modeled for the church the posture of the long-suffering patience..

There are countless examples of this, but, as we near the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King, I have one example I’d like to share from the civil rights movement. In this clip, you’ll see a young man leading a group to go and register to vote in their precinct. Their plan, should the courthouse be closed, is to pause for a time of prayer at the courthouse and return home. Watch with me what happens next.

Watching that, we may want to race in there and shake that officer and shout in his face or worse. Like Peter, we probably would love a show of force to put that officer in his place! But the young man in that video does not seem to require that from us. He seems to be well planted, sure, and patient. How is that possible? How, in the midst of suffering, and in the face of such antagonism is he able to be patient? Two words: first, practice. The posture of patience. Long-suffering. It’s a posture that is learned through practice; and learned quickly by people forced to practice in suffering regularly.

And the second word? Christ.

The patient love that young man showed his enemy, even inviting him to pray with him, or at least pray for him, has its source in the patience of Christ. What is not pictured in this clip is what likely happened immediately before this confrontation: Christian worship. One thing that was true of the vast majority of civil rights demonstrations, protests, and marches is that they started in a church, praising God, focusing on Christ, and getting behind Jesus.

See, when Jesus rebuked to Peter it was a command. “Get thee behind me. I’m not gonna let nobody turn me around.” And then he went and fulfilled his mission. So to us, the people of his resurrection, the command “get thee behind me” ceases to be an admonition and becomes an invitation.

For it is Christ who suffered patiently so that those who suffer would not suffer alone. It is Christ who suffered at the hands of the upwardly mobile so that their upward mobility could be redeemed into humility. It is Christ who took the hate and violence that should have been directed by him toward murderers, and terrorists, and demagogues, and slave traders, and school shooters, and instead bore it in his own body out of love for the unlovable, like me. And today, we who suffer, and we the perpetrators of suffering are invited once again to hear the words of the crucified and resurrected One. “Get behind me. Get behind me and walk the patient way of love trusting that there is nothing that can defeat the one whom you are behind.”

The invitation to get behind Christ is an invitation to be covered by him.

Christ covers over our sin–he gives us some cover and invites us behind him to walk in the way made possible by his salvation.

And, for those of us that are not persecuted, the invitation is to find refuge from our own demons, destructions, and delusions of grandeur and to get behind him.

That is the invitation answered by those early Christians in Africa, those Christians of the civil rights movement, and it is Christ’s invitation to us today. I stand as one thankful to have been commanded and invited and welcomed behind the cross of Christ; and it is in his name that I invite you once again, or for the first time, to flee from sin, be patient in suffering, and get behind Christ. Hear the good news, The Risen Christ invites you saying, “Get behind me.”

So may it be. Amen.

Follow @cmsvoteup

February 26, 2018

Because Jesus is the Temple, Liberation is Not Salvation

Can the oppressed nonetheless also be unrighteous?

Are the poor blessed by virtue of being poor, possessing an inherent righteousness, or do they not also need atonement made?

Can a victim of systemic sin still be a sinner in need of forgiveness? And speaking of victims, what about victimizers? If God’s preferential option is for the former, can the latter be justified?

I’m wondering about these questions because in the Gospel lection for this coming Sunday, Jesus pitches his (premeditated) Temple tantrum, whipping the money-changers, driving the livestock out of the sanctuary, and drop-kicking the cash registers. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus’ violent protest takes place the week of his Passion, but in John’s Gospel, the text for Sunday, the Temple tantrum comes right after the first of his signs, the wedding at Cana.

That the Jewish Leaders respond to Jesus behaving badly only by asking by what authority he has said and done this but do not call for his arrest implies that they likewise recognize the problem at hand. Because Roman coinage bore the image of Caesar and was stamped with a profession of faith to Caesar’s Lordship, it was unclean and out of bounds for Jewish ritual use. Moreover because it’s inconvenient to travel very far with your prized 4-H bull, Jewish pilgrims who came to the Jerusalem Temple for festival days often needed to purchase sacrificial animals after they arrived. So, in the text, the sheep and doves are being sold on the Temple grounds because neither would fit in a pilgrim’s wallet or duffle bag, and the money-changers have their tables set up there too because there’s little point in sacrificing an animal to make atonement for your sin if you’re going to buy that animal with cash that itself breaks the first and most foundational of commandments.

What Jesus diagnoses as a “den of thieves” began as an understandable and well-intentioned system. But, if you’ve been trapped in a movie theater, airport, or baseball stadium, then you can easily imagine how this process devolved into price-gouging poor pilgrims, extorting the faithful for ever greater sums.

That Jesus’ Temple tantrum is premeditated (he wove the whip from ropes) underscores how Jesus intended it as a performed parable. Rather than spontaneous anger, the Temple tantrum is a prophetic demonstration against an unjust and exploitive economic system.

Sure enough, this is how the John 2 text will get preached in many pulpits this coming Sunday. Jesus’ meme-starting moment in the Temple will be used as an example to exhort Christians to go and do likewise, pitching their own Temple tantrums to rage against modern day money-changers.

The righteous anger of the students in Parkland, Florida, for example, is an easy parallel to draw to Jesus’ own fury in his Father’s House and I’d bet a bull and 2 sheep that many preachers will go there. And to connect those dots from the pages of John’s Gospel to the newspaper pages isn’t wrong per se; it’s insufficient, for to employ this passage for imperatives exhorting social justice is to narrow the frame of the text.

As Pope Benedict writes, to ‘cast Jesus [merely] as a reformer in this passage of the cleansing of the Temple fails to do justice to the witness of the passage.’

To read the cleansing of the Temple as a prophetic act of social justice that compels our own similar acts misses what Jesus says in response to the leaders’ questions about his authority- and it misses how his answer differs from the Synoptics’ rendering of this response. In John, Jesus responds to their questions about his authority by saying “Destroy this Temple and in three days I’ll raise it up.” In the Synoptic Gospels, by contrast, this statement is put on the lips of Jesus’ accusers. What’s more, his accusers edit the statement, saying Jesus said: “I will destroy this Temple and in three days I will build another…” In the latter, Jesus is the agent of destruction but in the former, in John’s Gospel, we are the agents of destruction.

Which means:

Jesus is the Temple

And the sign of his authority is his Cross and Resurrection

Jesus identifying himself as the Temple where atonement is made echoes how the Book of Hebrews understands Christ’s own flesh as the Temple veil that mediates the holiness of God and the sin of humanity and Christ’s cross as the mercy seat upon which the propitiation of blood is sprinkled, once and for all.

In answering with himself as the Temple, Jesus points out that the system of Temple sacrifice wasn’t only problematic for those who made an exploitive mockery of it, it was problematic- maybe more so- for those who were sincere about it because it could not atone for your sins, once for all.

As common as it is for preachers to interpret Jesus’ Temple tantrum as the impetus for what we do against exploitive systems of injustice, scripture itself- notably, the Book of Hebrews- uses this passage not in terms of what we must do for God but what God has done in Christ for us.

That Jesus is the Temple, his flesh its veil, and his cross its mercy seat shows that the problem humanity faces is more systemic than the problems about which we prefer to preach

The New Testament, indeed all of the Bible, points to a far deeper and far graver source of human misery than injustice and oppression. It’s popular to the point of cliche to insist that God stands on the side of the marginalized and dispossessed and while that’s certainly true, it’s insufficient for, according to scripture, the marginalized and oppressed with whom God stands are also sinners in need of forgiveness and mercy.

To put it another way:

Liberation is not Salvation.

The emphasis upon social justice in the Church, whose premise is that what defines God’s redemptive activity is liberation from oppression, displaces the centrality that belongs to Jesus Christ alone as Savior of the world. What defines God’s redemptive activity is not liberation from oppression but from the Powers of Sin and Death, for the sign of God’s redemptive activity, so says Jesus, is Cross and Resurrection.

Liberation from oppression, standing up against social injustice, solidarity with the marginalized- those are all faithful frames and postures but they are not sufficient for what scripture names by ‘salvation’ because the oppressed still require atonement for their sins.

The dispossessed do not posses an inherent righteousness.

As my teacher George Hunsinger notes, referring to Karl Barth‘s work:

“The New Testament message, as I understand it, is that we have all sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, that we are helpless to save ourselves, and that our only hope lies in God’s gracious intervention for us in Jesus Christ. There is only one work of salvation. It has been accomplished by Christ. It is identical with his person…

Victim-oriented theologies, such as we find among the liberationists, fail to do justice to this central truth. The fundamental human plight is that of sinners before God not of victims before oppressors.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

February 25, 2018

Moving…

But this weekend I let my congregation know I would be appointed elsewhere this June. Here’s the note I wrote them. I thought I’d share it here too.

Hi Friends (and Steve Larkin),

If you missed worship this weekend…

Or if, like Lew, you’d already fallen asleep before the announcements…just kidding it’s about Grace not Law, right?

But if you weren’t here, you didn’t catch the news:

I heard last Friday that I will be appointed by the bishop to a different church in June.

Our Leadership Team and I had requested to the bishop that I return, but there were needs elsewhere in the conference and so I will be going. Almost 3 years ago to the day, you found out I had stage-serious cancer and now you find out I’ll be leaving you. I’m not very good when it comes to Februarys. My wife, just from the perspective of Valentine’s Day would agree. Can you tell how hard I’m trying to joke this news away? That’s because I don’t do feelings well, and, right now, I’m just sad. As big a pain in the ______ as you can be, I love you.

While Methodist pastors are part of an itinerant system, appointed one year at at time, and the unknown of being moved is something that comes up every year, this news is hard to adjust to after serving at Aldersgate for 13 years. Some of the kids who were here when I arrived are the adults I’ve married, and some of their kids I’ve gotten to baptize. I’ve buried many of your parents, and spouses. You’ve taught me to be a better pastor (well, most of you). You helped me keep the faith in the face of cancer, and, most importantly of all, you’re my friends- Dennis most important of them all. Like the tree in a forest, if a joke is told about Dennis and you’re not there to laugh was it even a joke? Not to mention, there’s the added inconvenience of having to rededicate my book to a different church in the second edition.

Starting in July I will be the senior pastor at another United Methodist Church in Northern Virginia. That’s all I’m permitted to say right now but I thought you deserved to know as much as you could as early as you could- and, I didn’t think my kids needed to keep our moving a secret longer than necessary.

My last Sunday here at Aldersgate will be mid-June. Bright side, the move shaves a few minutes off of Ali’s commute, the boys will remain near their friends, and I will be near my doctors. They boys are still processing the news but are relieved to remain close to their friends and curious about what’s to come.

With feedback from our Leadership Team, Dennis will be submitting his choices for a new associate pastor to the bishop in mid-March. You will find out who that person is sometime in April. It’s your job to give that new person every opportunity to succeed. But you know that already I think.

Of course, not all of you will miss me or be sad to see me go, in which case, I’d just like to point out that as my last act as your Executive Pastor I will be bringing Aldersgate even further into the black by my departure. So, I get the last laugh.

– Jason

PS:

Stay-tuned for next Sunday when we announce that Dennis will be leaving Aldersgate to join the cast of Moonshine Wars, and make sure you have our special ‘Gettin’ Rid of Richard Good Friday Service.’

And because I know that will generate questions from the unimaginative, Yes, that was a joke.

Follow @cmsvoteup

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers