Ben H. Winters's Blog, page 5

July 6, 2014

“Mysteries…reinforce belief in the fundamental order” –Daniel Friedman on God and the crime novel

One of the best mystery novels I read last year — and, listen, I read a lot of mystery novels — was by a guy named Dan Friedman, who put it in my hands his own damn self in New York City one evening at a MWA event. That book was Don’t Ever Get Old: great title, great novel, about a super-old Jewish World War II veteran and ex-homicide cop named Baruch “Buck” Schatz who gets caught up in a late-life crime caper, looking for Nazi gold and—oh, you know. Revenge. There’s a sequel, out this month, called Don’t Ever Look Back, which I haven’t read yet, but early reviews indicate it’s equally terrific.

I’ve had this feeling since reading the first Schatz novel that Dan and I are sort of kindred spirits, not only because we’re both obsessed with the structure of the mystery novel (and how to mess around with it) but also because we’re both secular Jews, whose work in some way is informed by that background. Someday I will force myself to think hard about how my religious background functions in my own work; in the meantime, I made Dan do it for my Reverse Blog Tour.

Take it away, Dan Friedman:

The arc of the archetypal mystery novel looks something like this: At the beginning, there is a crime, which disrupts the order of society. The business of the story is finding out why this happened, and rendering justice unto the perpetrator so that the orderly state that preceded the crime can be restored.

Daniel Friedman, with New York City behind him.

No matter how depraved the crimes they depict might tend to be, mysteries that follow this structure maintain and reinforce a belief in the integrity of this fundamental order. The crime being investigated is fundamentally aberrant, and it will be set right.

This plot structure, and the worldview that underpins it are intertwined with the key questions of Western religion. Mystery novels deal with many of the same problems that we ask in church or synagogue: Why do bad things happen to good people? How can justice coexist with so much suffering? And, at the same time, the conventions of the mystery novel strongly imply that God is working behind the scenes; assuring that every knotty conspiracy is matched with a dogged, patient sleuth who will unravel it, every devious killer is a little dumber than the cop or federal agent hunting for him, and within every sick or corrupt institution, there is someone with the backbone and standards to insist on doing things the right way.

The truth about crime and punishment is a lot less sunny: In New York City, where one of the largest, best funded and best trained police departments ever assembled patrols a city with a per-capita violent crime rate significantly below the national average, only two murderers out of three are caught and convicted. In smaller towns where violence is rare, resources are scarce, officers have little investigative experience and police officials are functionaries rather than detectives, homicides tend to have an even lower clearance rates.

If crime fiction reflected the truth about crime, it would be upsetting and demoralizing. Readers don’t want to see forensic tests take months to process and come back inconclusive. Readers don’t want to see serious crimes investigated by uninterested clock punchers. Readers don’t want to see bureaucratic breakdowns. Readers care who the killer is, and they want the hero to care as much as they do.

More ambitious crime writers will try to complicate the message a little bit: In my novels, my elderly detective’s triumphs over his adversaries does little to mollify his grief over the death of his son, and nothing to change his declining health. Ben’s novels, of course, place the criminal investigations in the shadow of a fast-approaching human extinction event that dwarfs the stakes of his hero’s main business. Both of us, I think are using impending, inevitable calamity to ask a question about whether anything we do matters when set in contrast with the inevitability of death

But they’re still mystery novels. Even in the shadow of a giant meteor poised to wipe out civilization, the readers will expect to know who did it, and why. The question of who did it has got to matter, and justice has got to be dispensed, even if you qualify the catharsis. Mystery novels, as we understand them, don’t work unless they take place in a universe where there is a God.

Thou shalt not neglect to craft satisfying character arcs.

I think readers know this subconsciously, even if they’ve never thought about it in these terms. Seeing mysteries unraveled feeds the same need we try to address by searching religious texts for answers to unanswerable questions. And the revelations are always more disappointing than you hope they’re going to be, because the authors generally aren’t in possession of any definitive answers to fundamental questions. At the end of most mystery novels, you usually find out that some asshole did it, for some asshole reason. And, if we’re being honest, the resolution can never really set right the initial wrong. Authors try to hide it with gunfights and car chases and explosions, but our catharses tend to be kind of anti-cathartic.

Religion in my books serves several purposes: It wedges my character in a history and a worldview. It makes him specific, rather than general, but I could have done that by making him the fourth son in a big Italian family, or the child of patrician WASPS, or just an old redneck.

But it also allows me to more directly explore the fundamental moral questions that are inextricable from the genre’s subject matter. In DON’T EVER GET OLD, Baruch can look at Christian notions of forgiveness and redemption with an outsider’s skepticism, because he is not a Christian. But his inability to forgive others suggests there are things in his past he can’t forgive himself for.

In my second book, DON’T EVER LOOK BACK, neither Baruch, an American WW2 veteran nor his antagonist, an Auschwitz survivor, can put their trust in a deity as a result of their experiences. Each of them tries, in a sense, to become God, by taking control of his own narrative, and when the stories they are trying to live out cannot be reconciled, they have to clash.

In my second book, DON’T EVER LOOK BACK, neither Baruch, an American WW2 veteran nor his antagonist, an Auschwitz survivor, can put their trust in a deity as a result of their experiences. Each of them tries, in a sense, to become God, by taking control of his own narrative, and when the stories they are trying to live out cannot be reconciled, they have to clash.

I’m not particularly devout or observant, and I have serious reservations about the applicability of ancient texts to modern problems, but I don’t think you serve much of a purpose by avoiding reference to God in books that are concerned with questions of justice.

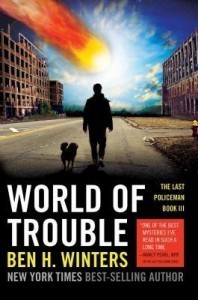

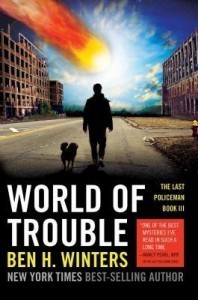

Thanks, Dan. You, like Buck Schatz, are a mensch. Stay tuned for more special guests, and don’t forget to pre-order World of Trouble. It comes out on July 15.

July 3, 2014

“SOMEONE STOLE YOUR PENCILS” YA novelist Suzanne LaFleur on what children care about

So, although I have written for kids, and I have a bunch of kids, I’m one of these weird adults who mostly reads fiction written for adults. I make an exception, however, for the novels of my old pal Suzanne LaFleur—her debut, Love, Aubrey, was so heartbreaking and good that I’ve read her two followups (Eight Keys and Listening For Lucca). Suzanne and I met a long time ago, when we were both working at the same elementary school for eccentric young geniuses, deep in the heart of the Upper West Side.

She’s a shy and thoughtful kind of person, but I goaded her into participating in my Reverse Blog Tour by promising to ask easy questions. I lied, though, they’re all ready hard.

***

OK, Suzy. Is there any difference in what kids books are supposed to do (comfort, challenge, scare, excite) as opposed to what adult literature is supposed to do?

No.

I would say the main purpose of both—and of literature in general—is to engage people with written language. Kids’ lit might need slightly different language or content to achieve that, but in terms of emotional investment, the criteria should be the same. People of any age will of course gravitate towards that which interests them, so there should be an equal variety of choices available for kids as for adults. Maybe not every kid wants to be scared, but that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be scary books for kids.

Suzanne LaFleur with her mysterious floating signature.

How does writing make you feel inside?

This question wins the award for “highest potential for an abstract answer.”

When writing isn’t going well, it feels really frustrating. I get up a lot, pace, do things around the house. I typically abandon it, and then at the end of the day, I feel bad because I didn’t produce anything. I gave up. But there’s no sense sitting to write if there’s nothing ready in your head.

When writing is going well, I go into a sort of trance, which can happen whether or not I’m physically writing or just walking around or swimming or something. When that happens, the story spins itself along and I observe, record, replay. I don’t notice the time passing. Sometimes it will be hours. I suppose that part feels good, because it’s kind of relaxing and the story unfolds very genuinely, but I’m definitely not aware enough to consider how it feels. I have recently put my awareness to the test a little bit, because in the past year I have become much more of a coffee-shop writer. At home, there are fewer signs of time passing in chunks around you, but at the coffee shop, I’ll realize I didn’t see people around me sit down or get up to leave their table; they will just suddenly seem to have appeared or vanished. Sometimes it’s scary, because—where have I been?

You’re probably thinking at the end of those days, living in the minds of my characters, I feel good, right? Nope. I feel bad then, too, because I can’t account for my time. Whole hours disappeared and I’m not even sure how I spent them. If you sit down to work after lunch and blink and realize it’s time to make dinner, it’s a bit disconcerting. Even if you’ve filled ten notebook pages. You should have noticed the day passing, right? Or filled the notebook pages and then moved on to something else? How do you hold yourself accountable for how you’ve spent your time when you literally make your living daydreaming?

If both kinds of days leave me feeling bad, why do I continue? I think my markers of accomplishment happen on a much larger scale. For example, I’ll scribble in my notebook for weeks, and then type it all up, and WOW, my document is fifty pages longer! That’s a day on which I feel like I’ve made progress. I can print it, read it—that feels good! Those days occur? Once every couple months. Even more rare: once every two-three years, I get to THE END of a draft. THE END. The elation of knowing you’ve reached the end—I can’t even explain it. It’s awesome. Then I get a letter from a nine-year-old reader: “your book [aka the result of all those hours of pacing as well as the ones that disappeared] has changed my life.” Changed a life! Hmm. Perhaps I wasn’t making a living daydreaming after all, but changing lives.

This lifeguard chair is in New Hampshire.

I’m reminded of something my dad said to me when I was a teenager. My first official job was as a lifeguard. I hated lifeguarding because it made me so nervous. But very little ever happened. Every time I came home from lifeguarding, my dad would ask, “Did you have to save anybody?” and I would say, “No,” feeling defeated, and then he would say, “Then you saved everybody.” I think writing is like that on some level. On most days, there’s not a big event. There may not be any sense of accomplishment after hours of sitting, watching and listening, and there may not be anything concrete to show for your work. Odds are you didn’t write a whole novel that day, so you would have to answer the question “did you write a novel today?” by saying “no.” But those hours still mattered. At the pool, my presence and advice prevented my patrons from needing someone to dive in after them—they’re not not changed. And their existence itself is actually quite concrete—without a dramatic event, they all walked away from my pool, to go home and have their dinners and live their lives. A million things that never happened actually add up to something positive, something whole and beautiful and maybe thoroughly unacknowledged by anyone. Writing, I sit and think for hours and hours, selecting a few words sometimes, and while nothing seems to be happening, a book emerges. I’m never not writing. One day, children will interact with my book for just a few hours of their lives, and walk away, perhaps declaring in a letter that they’ve been changed, the vast majority not noticing that anything’s different, but still, they’re not not changed.

So, after that, writing makes me feel good inside. The hours spent get forgotten; the words you’ve decided on stay, the impact you’ve had stays.

What did you learn from teaching little kids that has been valuable to you as writer, besides learning what sorts of stuff they’re interested in, content-wise?

I learned what they consider injustices and what they get excited about.

Injustices:

–Your friend plays with someone else and not with you.

–Your friend give away his/her candy to someone else and not to you.

–Your friend goes to someone else’s house—without you.

–Your parents are the only ones who don’t come to the classroom party.

–Your parents don’t let you have sleepovers on a school night. Even though someone else’s parents do.

–Your teacher seems to pick you to blame out of a group of people all doing the same bad thing.

–Your teacher gives you the previously-determined penalty for not doing your homework (I haven’t yet figured out why, but your teacher is always being unfair if you haven’t done your homework).

–SOMEONE WENT IN YOUR DESK. IN YOUR DESK. YOUR PRIVATE SPACE. AND STOLE YOUR PENCILS.

–Pizza lunch day is canceled with no warning. And it’s the only day you’re allowed school lunch and now it’s ruined. What will you EAT?

–You don’t get to finish eating in the allotted time. Even though you were able to draw three pictures, talk and laugh with your friends, and make fun of someone else, you definitely weren’t given enough time to eat and now you will be hungry and sad for the rest of the day.

–It rains. Unless you happen to prefer reading, rain interfering with recess is a terrible injustice.

Taken!

–You don’t get to be Benjamin Franklin on biography day. Everyone knows that you love Benjamin Franklin the most. And that is why someone else claimed Benjamin Franklin first. On purpose. To be mean.

Excitements:

–Anything that disrupts the daily lessons routine in any way (unless gym is canceled—that’s an injustice)

–Parties. In school or out. Parties rule.

–Sugar. Sugar when combined with parties is particularly exciting. Too much sugar usually leads to additional events in the “injustices” category, but to start out with, sugar is great.

–Showing off a newborn sibling. Additionally, when asked to write a memoir about something important that happened in his or her life, a young child will most often write about the birth of a sibling, and each author will include what he or she ate for dinner that night. I checked this phenomenon against my own memory, and it’s true, I remember eating fried eggs for dinner the night one of my sisters was born, though I was four at the time.

–Riding on a school bus to anywhere (really doesn’t matter where).

–Anything with “land” in the name. Legoland. Disneyland.

–Singing. Everyone loves singing. Especially in rounds.

–A new friend coming over for the first time. Heightened by the fact that this event involves written record passed between parents and teachers, and must otherwise remain totally secret, so as not to create injustices for others.

–The return of anyone beloved. Even if the person was your student teacher for only a couple weeks. She comes back to visit, she is beloved.

–GRANDPARENTS. ARE THE BEST.

Kids’ emotions are almost palpable: hot, invisible bubbles of anger or joy bursting from their chests in silent waves. I would bottle up all these feelings—the lunchboxes lovingly packed, the ones that weren’t; the girl ecstatic to head to grandma’s, the boy who’d never met his dad—and take them home with me, where they would filter into the emotions of my characters.

“SOMEONE STOLE YOUR PENCILS” YA novelist Suzanne Fleur on what children care about

So, although I have written for kids, and I have a bunch of kids, I’m one of these weird adults who mostly reads fiction written for adults. I make an exception, however, for the novels of my old pal Suzanne LaFleur—her debut, Love, Aubrey, was so heartbreaking and good that I’ve read her two followups (Eight Keys and Listening For Lucca). Suzanne and I met a long time ago, when we were both working at the same elementary school for eccentric young geniuses, deep in the heart of the Upper West Side.

She’s a shy and thoughtful kind of person, but I goaded her into participating in my Reverse Blog Tour by promising to ask easy questions. I lied, though, they’re all ready hard.

***

OK, Suzy. Is there any difference in what kids books are supposed to do (comfort, challenge, scare, excite) as opposed to what adult literature is supposed to do?

No.

I would say the main purpose of both—and of literature in general—is to engage people with written language. Kids’ lit might need slightly different language or content to achieve that, but in terms of emotional investment, the criteria should be the same. People of any age will of course gravitate towards that which interests them, so there should be an equal variety of choices available for kids as for adults. Maybe not every kid wants to be scared, but that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be scary books for kids.

Suzanne LaFleur with her mysterious floating signature.

How does writing make you feel inside?

This question wins the award for “highest potential for an abstract answer.”

When writing isn’t going well, it feels really frustrating. I get up a lot, pace, do things around the house. I typically abandon it, and then at the end of the day, I feel bad because I didn’t produce anything. I gave up. But there’s no sense sitting to write if there’s nothing ready in your head.

When writing is going well, I go into a sort of trance, which can happen whether or not I’m physically writing or just walking around or swimming or something. When that happens, the story spins itself along and I observe, record, replay. I don’t notice the time passing. Sometimes it will be hours. I suppose that part feels good, because it’s kind of relaxing and the story unfolds very genuinely, but I’m definitely not aware enough to consider how it feels. I have recently put my awareness to the test a little bit, because in the past year I have become much more of a coffee-shop writer. At home, there are fewer signs of time passing in chunks around you, but at the coffee shop, I’ll realize I didn’t see people around me sit down or get up to leave their table; they will just suddenly seem to have appeared or vanished. Sometimes it’s scary, because—where have I been?

You’re probably thinking at the end of those days, living in the minds of my characters, I feel good, right? Nope. I feel bad then, too, because I can’t account for my time. Whole hours disappeared and I’m not even sure how I spent them. If you sit down to work after lunch and blink and realize it’s time to make dinner, it’s a bit disconcerting. Even if you’ve filled ten notebook pages. You should have noticed the day passing, right? Or filled the notebook pages and then moved on to something else? How do you hold yourself accountable for how you’ve spent your time when you literally make your living daydreaming?

If both kinds of days leave me feeling bad, why do I continue? I think my markers of accomplishment happen on a much larger scale. For example, I’ll scribble in my notebook for weeks, and then type it all up, and WOW, my document is fifty pages longer! That’s a day on which I feel like I’ve made progress. I can print it, read it—that feels good! Those days occur? Once every couple months. Even more rare: once every two-three years, I get to THE END of a draft. THE END. The elation of knowing you’ve reached the end—I can’t even explain it. It’s awesome. Then I get a letter from a nine-year-old reader: “your book [aka the result of all those hours of pacing as well as the ones that disappeared] has changed my life.” Changed a life! Hmm. Perhaps I wasn’t making a living daydreaming after all, but changing lives.

This lifeguard chair is in New Hampshire.

I’m reminded of something my dad said to me when I was a teenager. My first official job was as a lifeguard. I hated lifeguarding because it made me so nervous. But very little ever happened. Every time I came home from lifeguarding, my dad would ask, “Did you have to save anybody?” and I would say, “No,” feeling defeated, and then he would say, “Then you saved everybody.” I think writing is like that on some level. On most days, there’s not a big event. There may not be any sense of accomplishment after hours of sitting, watching and listening, and there may not be anything concrete to show for your work. Odds are you didn’t write a whole novel that day, so you would have to answer the question “did you write a novel today?” by saying “no.” But those hours still mattered. At the pool, my presence and advice prevented my patrons from needing someone to dive in after them—they’re not not changed. And their existence itself is actually quite concrete—without a dramatic event, they all walked away from my pool, to go home and have their dinners and live their lives. A million things that never happened actually add up to something positive, something whole and beautiful and maybe thoroughly unacknowledged by anyone. Writing, I sit and think for hours and hours, selecting a few words sometimes, and while nothing seems to be happening, a book emerges. I’m never not writing. One day, children will interact with my book for just a few hours of their lives, and walk away, perhaps declaring in a letter that they’ve been changed, the vast majority not noticing that anything’s different, but still, they’re not not changed.

So, after that, writing makes me feel good inside. The hours spent get forgotten; the words you’ve decided on stay, the impact you’ve had stays.

What did you learn from teaching little kids that has been valuable to you as writer, besides learning what sorts of stuff they’re interested in, content-wise?

I learned what they consider injustices and what they get excited about.

Injustices:

–Your friend plays with someone else and not with you.

–Your friend give away his/her candy to someone else and not to you.

–Your friend goes to someone else’s house—without you.

–Your parents are the only ones who don’t come to the classroom party.

–Your parents don’t let you have sleepovers on a school night. Even though someone else’s parents do.

–Your teacher seems to pick you to blame out of a group of people all doing the same bad thing.

–Your teacher gives you the previously-determined penalty for not doing your homework (I haven’t yet figured out why, but your teacher is always being unfair if you haven’t done your homework).

–SOMEONE WENT IN YOUR DESK. IN YOUR DESK. YOUR PRIVATE SPACE. AND STOLE YOUR PENCILS.

–Pizza lunch day is canceled with no warning. And it’s the only day you’re allowed school lunch and now it’s ruined. What will you EAT?

–You don’t get to finish eating in the allotted time. Even though you were able to draw three pictures, talk and laugh with your friends, and make fun of someone else, you definitely weren’t given enough time to eat and now you will be hungry and sad for the rest of the day.

–It rains. Unless you happen to prefer reading, rain interfering with recess is a terrible injustice.

Taken!

–You don’t get to be Benjamin Franklin on biography day. Everyone knows that you love Benjamin Franklin the most. And that is why someone else claimed Benjamin Franklin first. On purpose. To be mean.

Excitements:

–Anything that disrupts the daily lessons routine in any way (unless gym is canceled—that’s an injustice)

–Parties. In school or out. Parties rule.

–Sugar. Sugar when combined with parties is particularly exciting. Too much sugar usually leads to additional events in the “injustices” category, but to start out with, sugar is great.

–Showing off a newborn sibling. Additionally, when asked to write a memoir about something important that happened in his or her life, a young child will most often write about the birth of a sibling, and each author will include what he or she ate for dinner that night. I checked this phenomenon against my own memory, and it’s true, I remember eating fried eggs for dinner the night one of my sisters was born, though I was four at the time.

–Riding on a school bus to anywhere (really doesn’t matter where).

–Anything with “land” in the name. Legoland. Disneyland.

–Singing. Everyone loves singing. Especially in rounds.

–A new friend coming over for the first time. Heightened by the fact that this event involves written record passed between parents and teachers, and must otherwise remain totally secret, so as not to create injustices for others.

–The return of anyone beloved. Even if the person was your student teacher for only a couple weeks. She comes back to visit, she is beloved.

–GRANDPARENTS. ARE THE BEST.

Kids’ emotions are almost palpable: hot, invisible bubbles of anger or joy bursting from their chests in silent waves. I would bottle up all these feelings—the lunchboxes lovingly packed, the ones that weren’t; the girl ecstatic to head to grandma’s, the boy who’d never met his dad—and take them home with me, where they would filter into the emotions of my characters.

July 2, 2014

man on the scene

Tomorrow we will be continuing the Reverse Blog Tour, which I hope is providing some interest and amusement, but I needed to interrupt just briefly to share two really exciting pieces of media: one is that this Barnes & Noble Book Buzz post put The Last Policeman on a list of “five new detective-fiction classics“, along with Benjamin Black (who is not-secretly John Banville), Robert Galbraith (who is even less-secretly JK Rowling), Loren D. Estleman, and, uh, Stephen King.

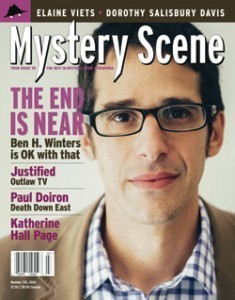

The second exciting thing is that Mystery Scene Magazine put me on the cover of their July issue; you can see the picture here—though to read the article you’ll have to find yourself a print copy, as I will be doing tomorrow!

The second exciting thing is that Mystery Scene Magazine put me on the cover of their July issue; you can see the picture here—though to read the article you’ll have to find yourself a print copy, as I will be doing tomorrow!

Like I said, back tomorrow with more guest bloggers, starting with the remarkable Suzanne LaFleur. (And don’t forget to pre-order World of Trouble and win big prizes from Quirk Books.)

June 30, 2014

“Exeunt Omnes” — Ian Doescher works his Shakespearean magic on The Last Policeman

Ian Doescher is the guy who had the brilliantly simple idea of rewriting the entire Star Wars trilogy as Shakespearean tragedies—and not only did he have the idea, he’s executing it well, rendering all of Luke and Han’s dialog in flawless iambic pentameter. William Shakespeare’s Star Wars and The Empire Striketh Back were Times bestsellers, as I’m sure The Jedi Doth Return will be—it comes out tomorrow!

Hereth is Ian:

Ian Doescher, Poet Laureate of Dagobah.

When you work with a mid-sized publisher like Quirk Books, you hear a lot about the other books they publish. While I was working on the William Shakespeare’s Star Wars trilogy, I heard about two other trilogies currently in the works with Quirk Books: Ransom Riggs’ Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children trilogy, and, of course, Ben’s Last Policeman trilogy.

When I heard about The Last Policeman in the fall of 2013, the concept was immediately attractive to me: a detective novel with just one element of reality tweaked—the impending end of the world. I was fascinated by the concept and even more excited when I read The Last Policeman and Countdown City in quick succession. Hank Palace was a hero unlike any I’d met before: dutiful, blundering, compassionate, thoughtful, and devoted to his craft (to a fault). I looked forward to World of Trouble with excitement, and read it as soon as Quirk Books could send me an advance copy. Now I know how it ends—but of course I’m not saying. (How fun to write a trilogy and have your readers not know the ending! Everyone knows how William Shakespeare’s The Jedi Doth Return is going to end up.)

Ben and I were virtually introduced back in November, and I couldn’t help but fan boy on him a little bit. In the midst of our correspondence, I decided Hank Palace needed his own Shakespearean treatment. So now, as we prepare for the final book in The Last Policeman trilogy, I humbly present the soliloquy Shakespeare might have penned had he been clever enough to invent Hank Palace:

Palace:

What dismal age is mine in which to live—

An asteroid doth come to crush the Earth,

The new book, which I cravenly did not write in verse.

Humanity of future is bereft,

Each story now is fear and apathy

And, in the end, the hand of suicide.

Yet even in the midst of terror great

Some signs of hope still break upon my sight:

The college boys out rowing in their shells,

The skill’d forensic doctor plies her trade,

All people who maintain their excellence—

Forsooth, these things I like. Aye, them I like.

In such an age we stand apart, alone,

E’en a policeman who doth battle crime

Though seemingly ‘tis pointless so to do.

Yet, I have little pride as I perform

My calling to enforcement of the law.

Aye, even as I spend my working days

In dutiful fulfillment of my job—

Good Farley and wise Leonard with me e’er—

There sometimes comes a nasty, creeping thought:

Belike my lawful life is meaningless.

Such naggings plague my soul, and shake my heart—

In these dark moments doubt creeps in, and then

Ne’er was a Palace emptier than I.

Yet e’en when these vile questions do arise,

I see my Concord with the eyes of hope.

For from the darkest moments grows within

A newfound confidence in ev’ry step:

I can the last days face with courage rare

E’en if I were the last policeman e’er.

[Exeunt omnes]

Congratulations, Ben. Here’s to the next trilogy.

June 26, 2014

“They always assumed I was writing a children’s book” — Laura McHugh on writing while parenting

My fellow midwesterner Laura McHugh just published her debut novel, a wickedly dark murder novel called The Weight of Blood. I thought she was a perfect person to invite on the Reverse Blog Tour to talk about something I think about all the time: how to reconcile the writing side of one’s life with the parenting side. Because you do, if you’re a dad or a mom and also a writer—especially a mystery writer—then you’ve got these two parts, the part that imagines bloody scenarios and broods over complicated crimes, and the part that changes diapers and carefully applies sunscreen.

Here’s Laura:

Look at Laura McHugh’s enigmatic smile. Is she planning a playdate or a murder?

I didn’t tell many people that I was writing a book. I had recently lost my longtime job as a software developer and given birth to my second daughter, and I dreaded the pitying looks people would give me if I admitted that I spent every spare moment working on a novel that would probably never be published

At that point in my life, everyone saw me as a stay-at-home mom. Some of the other stay-at-home moms did not even know I’d had a full-time career writing software, and I was hesitant to tell them that my children were not my sole focus—that the moment my daughters fell asleep each night, I opened a seemingly innocuous Word document that began with the discovery of a girl’s dismembered body in a tree.

Once I let people in on my secret writing life, they almost always assumed that I was writing a children’s book. Oh, that’s great! Have you read it to your kids? (No, they’re not quite old enough for stories about backwoods human traffickers.)

I was surprised that everyone expected me to write stories for children. I wondered if I should be insulted that no one assumed I wrote werewolf erotica or biographies or hardboiled crime fiction. I mean, I did have children, and I read lots of kiddie books, but just because I spent every waking minute immersed in diapers and sippy cups and Barney songs didn’t mean that was all I thought about. Perhaps, on the surface, I didn’t appear to be the type of person who would write something so dark. What many of my acquaintances didn’t know was that I’ve always had a penchant for twisted tales. I grew up reading Stephen King and Shirley Jackson. Even when it comes to kids’ books, I tend to favor stories about monsters and ghosts and witches. I’ve read Goodnight Goon to my kids more times than Goodnight Moon.

This is not a sippy cup.

To my amazement, the book that I wrote while my children slept was published. It went out into the world, where anyone could read it. People saw that I hadn’t written a picture book. They knew that The Weight of Blood was dark, and unsettling, and that these dark, unsettling things had come out of me, the mother of two sweet little girls. There were a few awkward moments, like when you realize that your in-laws, your kids’ teachers and babysitters, and the priest at your church have all read a sex scene you wrote. I had to own it. Yes, this is me, this is the sort of thing that lurks in my head and demands to be put down on paper.

I can write about horrible crimes and still chat about potty training and playdates with all the other mommies.

***

Thanks, Laura!

I actually think this is a pretty gendered aspect of our profession; as cheerful and goofy a dad as I am, I doubt anyone is shocked, exactly, to discover that I write very dark stories—I think women, and especially moms, are just assumed by society to be cheerful and nurturing, inside and out.

Interestingly, women have ALWAYS been notably proficient and successful at this business—I’m not an expert, but I bet there are more famous female names in mystery and crime fiction than other literary forms. (From Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers to PD James and Patricia Highsmith to Sue Grafton and Sara Paretsky, right on down to Gillian Flynn.)

I’d love thoughts on this from my fellow writers and parents, of all genders—meanwhile, get to know Laura McHugh, and come meet me on tour, starting in Indianapolis on July 12.

June 22, 2014

“I like many comics, and I like many romance novels” — Noah Berlatsky on eclecticism

When you are a kid and your older cousins have huge comic book collections, you think they are the coolest people in the world. Imagine how much cooler it is when they both grow up to be actual recognized experts in comic books? THAT HAPPENED TO ME. My cousin Eric Berlatsky is an English professor, but he’s the kind who publishes books about Alan Moore. His brother Noah, meanwhile, is not only a prolific freelancer but also the proprietor of this insane website about superheroes and…well, superheroes and everything else—here, I’ll let him tell you…

Hey all; I’m Noah Berlatsky, Ben’s cousin. I write at the Atlantic and edit a comics and culture website called The Hooded Utilitarian. (or sometimes HU for short.) Ben asked me to contribute to his reverse blog tour, and since I have known Ben since before he was born, I figured I should say yes. So here I am!

Hey all; I’m Noah Berlatsky, Ben’s cousin. I write at the Atlantic and edit a comics and culture website called The Hooded Utilitarian. (or sometimes HU for short.) Ben asked me to contribute to his reverse blog tour, and since I have known Ben since before he was born, I figured I should say yes. So here I am!

As folks here know, Ben’s Last Policeman series is a detective/sci-fi genre-crossing extravaganza. Ben saw a bit of a parallel there with my criticism, since I write about lots of different genres (YA, and comics, and sci-fi, and literature, and romance, to just stick to print ones.) And, for that matter, for a blog that’s ostensibly about comics, HU is quite eclectic when it comes to what genres we cover. We have posts on wine, posts on fashion, posts on film and posts on music, just for starters.

So, Ben asked me, what’s with that, exactly? Are there benefits to crossing genres? Or does it just sow confusion?

This is not a comic book.

The answer is maybe some of both. There are definitely disadvantages to eclecticism. The main downside is that aesthetic experience in our culture is organized, often quite intensely, around genres. Lots of folks of course have different genre interests — but nonetheless, if you go to a comics website, you tend to want to read about comics, not fashion or music or wine. So just in terms of marketing and retaining an audience, crossing genres as often as we do at HU can be a bad idea. You confuse the brand.

Crossing genres can also be uncomfortable in other ways. Genres aren’t just category designations; they’re communities. Refusing to embrace one genre means to some degree that you’re refusing to fully occupy one community — and that means people can end up seeing you as untrustworthy or as an interloper. I’m interested in romance novels and comics, for example, but I’m not exactly in the fandom of either, which means I haven’t necessarily read as much as people who are more fully committed. I’ve had both comics fans and romance novel fans be super-welcoming, and interested in what I have to say. But I’ve also had people from both communities basically argue that I don’t have enough expertise to speak, or that I’m morally compromised when I talk about the genres because I’m an outsider.

I don’t mean to dismiss those critiques. It be difficult, or uncomfortable, or problematic, to write as an (at least partial) interloper. Just as it can seem needlessly alienating, I suppose. to write fashion posts on a comics blog. Still, I think it’s worth doing both for a couple of reasons.

First, I get bored writing about the same thing all the time. I like many comics, and I like many romance novels, but I don’t want to just read and write about comics, or just read and write about romance novels. I doubt that that’s especially unusual or anything — most people have different interests and like to dabble in different things to some extent. But fear of boredom is a big part of the impetus for me to try new things and write about new things, so I thought I should mention it.

This is not a romance novel.

The second reason is a little more involved. Maybe I can explain best through a book by Carl Freedman called “Critical Theory and Science Fiction.” In the book, Freedman points out that while we usually think of art being broken down into genre, it’s actually more accurate to say that genre precedes, or defines art. Shakespeare’s plays, for example, are art. Shakespeare’s laundry lists are not art. The genre of plays are seen as aesthetic objects, worthy of analysis and fandom. The genre of laundry lists are not. Recognition of genre, then, precedes the perception of art. For art to be art, it needs to be in the right genre.

I think this is true beyond just laundry lists and plays. Freedman points out that sci-fi, by virtue of its genre, has often been seen as lesser or marginal — Samuel Delany isn’t a laundry list, but he’s not quite perceived as (say) Borges either. Romance novels are even more denigrated. Wine often isn’t exactly seen as an aesthetic experience at all — or at least not as one that can be usefully discussed alongside film or television or literature.

The question here might be, so what? Why does it matter if people want to think about comics rather than fashion, or literature rather than romance novels?

Sometimes, maybe it doesn’t matter all that much. But, as genres are social constructions, the way they’re manipulated can also have social effects, for better or ill. Freedman notes that African-American literature, for example, is often treated as a specialized genre, marginal to capital-L literature. Romance’s denigration has a lot to do with the way it is perceived as art by and for women — which is why fashion is often seen as not-quite-art as well. Genre designations tell us what is important, what has quality, what is of interest. And they do so in a way that is often beyond analysis, because the recognition of, or use of, genre, precedes, and creates the grounds of, the analysis itself.

Trollope’s beard is considered by some to have been its own genre.

Which is why I’m interested in trying to engage with different genres, and to think about the ways (for example) in which comics fandoms and romance fandoms are similar and different, or to include posts about video games alongside posts on Trollope. Genre shapes how we look at art, and so at life. That’s not a bad thing, necessarily— but it seems worth shaking it up occasionally too, if only to see who’s being left out of which landscapes.

As in Ben’s books, a different investigator can maybe help you see where the world ends, and where others might start.

***

Thank you, Noah!

This, dear readers ,is the level of discourse you will always find at The Hooded Utilitarian, though very rarely here on my website. We do keep it classy with our next guest, though: Laura McHugh, a fellow midwesterner, whose fierce debut novel is The Weight of Blood. Laura will be here later in the week to talk about another odd crossing of genres: “author” and “parent.”

Onwards!

June 21, 2014

Not your average book tour!

My new book.

The Reverse Blog Tour will continue on Monday with a guest post from the mysterious Hooded Utilitarian, but I wanted meanwhile to fill you in on my very special, not-your-average book tour, which will take me to some great bookstores all through the month of July.

I am going to do all the usual author-visit stuff, but (like a good mystery writer) I’ll be adding a couple of surprise twists.

My ukulele.

Here’s the pitch…

Join author and raconteur Ben H. Winters to celebrate the release of World of Trouble, the concluding volume in the Edgar-award-winning Last Policeman trilogy. Ben is so excited to come and meet readers, he will do not only the the usual book tour activities (read from the new book, sign books, answer reader questions), he will also…

* Deliver his Patented Rapid-Fire Five-Minute History of Crime Fiction, and give out his top secret list of Ten Crime Novels Every Human Must Read

* play Mystery Trivia with the audience, and give away fabulous prizes—like signed manuscript pages and novelty Detective-Palace-style mustaches!

* Play a medley on his ukulele of every single Bob Dylan song mentioned in the Last Policeman trilogy!

First stop is Indianapolis on July 12: see you there!

June 20, 2014

“We rise, we fall, we gather”–Hugh Howey on trilogies

My Reverse Blog Tour is designed to promote the release of the concluding volume of my trilogy, so I figured I’d start by asking someone to explain for us the enduring appeal of tripartite fictions—do trilogies make some inherent mystical sense, somehow, or do we just do it because it’s always been done?

Who better to meditate on the question of threedom than science-fiction author Hugh Howey, whose Wool novels were a genuine self-publishing phenomenon in 2011 and 2012 (so much so that they are now published by Simon & Schuster), and who is co-editor of The Apocalypse Triptych, a super-cool series of end-of-the-world anthologies to which I am a proud contributor.

Here’s Hugh:

First up on the Reverse Blog Tour:

Mr. Hugh Howey

Bad things and fiction have this in common: They both seem to come in threes. This is not a recent phenomenon. The superstition of threes dates back for centuries. And even two thousand years ago, theater often came in the form of trilogy. Classical music is fond of triplets as well. And both film and novels have displayed this tendency for as long as the mediums have been popular.

Stories are fractal in a way. Every proper novel has a beginning, middle, and end. But if you inspect just the middle of most books, you’ll see that it has a beginning, middle, and end of its own. As does each of those scenes, and so on. All of these embedded trilogies combine to form a single novel, which we often lump into larger trilogies of three distinct books. And it doesn’t stop there. If you are a fan of the Star Wars universe, you are eagerly awaiting a third set of trilogies. Each trilogy becomes its own single story, and one story just isn’t good enough.

Conflict, denouement, resolution. The rising action, the climax, the aftermath. Our brains are sensitive to patterns, even where they do not exist. When something bad happens, we brace for the next tragedy, and then claim the cycle is closed with the third. But it always starts again. We just keep counting in threes.

Three furies.

Look at the Holy Trinity. Or Freud’s id, ego, and superego. You have the Three Furies and the Three Fates from ancient mythology. There is some speculation that three holds sway as the first prime number, the first number that isn’t easily distributed. It sits like a triangle in our minds, the sturdiest of shapes and also the first circular structure. Thinking on a set of three is like studying a well-balanced painting, your mind cannot rest and finds itself roaming, circulating, considering.

The Walpiri of Australia are said to count: One, two, many. And in that way, they are our kin. We refer to the entire alphabet as the ABCs. As Monty Python puts it, the Holy Number of Counting is Three. Thou shall not count to four. And Five is right out. (Don’t tell this to Douglas Adams or Isaac Asimov.)

As a reader and a writer, why am I drawn to trilogies? They don’t exist because of 3-book deals from publishers; it’s far more likely that those 3-book deals exist because of the innate allure of the number. When I finished my first novel, I immediately set out to write a sequel. Now that I had characters introduced, I could jump right into the action with them. And then a third book was needed for mopping up. A fourth book served as prelude, providing origin stories. This pattern of 3+1 has a long history, both in Greek Theater and classical music. Tolkien’s classic works followed this form. Or am I just looking for patterns in noise? Do we all tally the coincidental?

I tend to be a skeptic on these things. I don’t believe that bad things come in threes. We just group them that way. We strain to find that third bad thing so we can put a bow on our tragedy and seal it away, keep it from haunting us further. Until the next tragedy strikes and starts the counting again.

But with storytelling, I can’t help but see the rightness of the triptych. We rise, we fall, we gather. Stories are peaks and valleys, a sharp sine wave, the shape of the angry sea. And looking closely, the sets of three are made up of threes. This is as much as we care to hold of a story. Until we’re ready to start all over again.

***

Thanks so much, Hugh, for kicking off my inverted tour, and thank you, dear readers, for playing along. Feel free to comment if you think Hugh hit the nail on its three-pointed head, or to tell him he’s off his rocker (Hugh is no stranger to controversial discussions)—and then drop back by on MONDAY JUNE 23 when Noah Berlatsky, a.ka. The Hooded Utilitarian, will be stopping by to talk about the blending of genres.

And (what the hell, it’s my stupid website), don’t forget to PREORDER WORLD OF TROUBLE and win fabulous prizes. There, I said it.

***

June 17, 2014

Order my new book! Win fabulous prizes!

These illustrated panels of The Last Policeman by Joseph Laney are objectively incredible.

The team at Quirk Books have announced an official “pre-order campaign” for World of Trouble, the concluding volume in the Last Policeman trilogy.

Prizes to be won include signed bookplates, amazing fan art by Joseph Laney, and the official “Hank Palace Survival Kit,” which has to be seen to be believed, but which definitely includes a big bag of coffee beans.