Angela Rae Harris's Blog, page 21

September 28, 2025

Mark Kiszla: The CU Buff who wilts under glare of spotlight is Coach Prime

For that $54 million the CU Buffs forked over to him, shouldn’t Deion Sanders be expected to look at a clock and tell the time?

As a showman, Coach Prime shines more brilliantly than the huge necklace he wears in Folsom Field.

As a cancer survivor, he’s a beacon of hope to anyone facing a similar fight.

But on game day, Sanders is a bad football coach.

“Sometimes,” he said after Colorado’s 24-21 loss to nationally ranked Brigham Young, “it felt like the moment was just too big for some of our athletes.”

Oftentimes, the member of the CU football program stumbling worst under the glare of the bright lights is Sanders.

He blew an early 14-point lead against the Cougars and went home a loser with two timeouts in his pocket.

“In the awkward moment when you get your butt kicked, it’s always awkward to run across the field to greet the (other) coach,” said Sanders, whose record against ranked foes since taking over in Boulder is now 1-8.

Well, know what’s even more awkward to watch?

With Sanders flanked by assistant coaches Warren Sapp and Marshall Faulk, there are three – count ’em- three members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame on the CU sideline.

And, sometimes, I swear there is no common sense.

For the second time this season, Sanders’ inability to manage the clock late in the fourth quarter contributed significantly to a Colorado loss.

The Buffs did not call a timeout to stop the clock, settle the hyperactive nerves of quarterback Kaidon Salter, or dial up the perfect play in the game plan after the 6-minute, 45-second mark of the final period.

And Sanders wasted that timeout to let staff talk a $54 million head coach out of his gut instinct to go for the gusto on fourth down near midfield while trailing by three points to 25th-ranked BYU.

“I thought about going for it … I really wanted to do it,” said Sanders, admitting it was a collective decision to punt.

Punt? That’s not Prime. That’s lame.

Without Heisman Trophy winner Travis Hunter and a pro-quality quarterback in Shedeur Sanders, these Buffs aren’t good enough to play scared and pray for the best.

Taking the safe way out and punting in front of a national television audience when the vast majority of 52,265 fans have your back seems to be the very antithesis of “We Comin’” and “Ain’t Hard to Find.”

As the only professional athlete in history to play in both the Super Bowl and World Series, he never choked in the big moment as a cornerback or outfielder.

As coach of the Buffs, however, Sanders doesn’t seem to make any better choices in the clutch than Mike MacIntyre or Mel Tucker did.

With the constant Louis Vuitton threat to send under-achievers packing, Sanders exhorted his players to “step up.”

As a wild card that proved to be a joker no matter what position he played, CU sophomore Dre’Lon Miller stood up and stepped out against the Cougars, producing 79 yards and two touchdowns on only 10 touches from scrimmage.

Much more than a fluke, Miller looks like a fixture of the CU offense in the future. “That was real-real,” insisted Sanders. “We’re going to use him as much as we can and even more.”

So all is not lost for the Buffs. And, yes, it could be worse.

Look to Fort Collins, where Colorado State would be crazy to keep clueless coach Jay Norvell employed even one more day.

Or take a gander at the Air Force Academy, where it feels like the time is rapidly approaching to give distinguished coach Troy Calhoun a gentle nudge into the wild, blue yonder of retirement.

Already stuck in last place of the Big 12 Conference standings and with not a gimme victory remaining on the schedule, Sanders finds himself with his back against the Flatirons.

“I’m trying to find light,” Prime said, “In a dark tunnel.”

Summer has come and passed.

Will these Buffs wake up when September ends?

Prime shouldn’t require a timeout to know the score.

Right now, CU has more gold jackets (three) on the sideline than victories (two) in the books.

Guess $54 million doesn’t go as far as it once did.

How to watch: Broncos vs. Bengals on Monday Night Football

TV: ABC (Joe Buck, play-by-play; Troy Aikman, analyst; Lisa Salters, sideline; Laura Rutledge, sideline)

Kickoff: 6:15 p.m. Monday

Radio: 94.1 FM and 850 AM KOA (Dave Logan, play-by-play; Rick Lewis, analyst; Susie Wargin, sideline)

Betting line: Broncos -7.5

Broncos vs. Bengals | The Denver Gazette’s picks

The Denver Gazette sports staff predicts Monday’s game between the Broncos and Bengals at Empower Field at Mile High.

Paul Klee’s pick: Broncos 22, Bengals 20

Denver’s ferocious pass rush is working, with an NFL-tops 12 sacks. The run game kicked into gear, with J.K. Dobbins’ three TDs. The Broncos will win, but what’s out of sync won’t find itself Monday: the round-peg-square-hole pairing of Sean Payton’s vision and Bo Nix’s skillset.

Overall: 2-1

Chris Schmaedeke’s pick: Broncos 27, Bengals 10

The Broncos get back on track against the woeful Bengals defense. Bo Nix throws two touchdowns, but questions still linger about whether this offense is good enough to beat the elite teams in the AFC.

Overall record: 1-2

Chris Tomasson’s pick: Broncos 30, Bengals 17

Broncos running back J.K. Dobbins has talked about averaging 6 yards per carry, and he might do that Monday against the woeful Bengals defense. Dobbins, coming off an 83-yard game at the Chargers, now again has a higher career yards-per-carry average than the legendary Jim Brown, 5.26 to 5.22.

Overall record: 2-1

Mark Kiszla’s pick: Broncos 31, Bengals 10

J.K. Dobbins runs wild, the Broncos run roughshod over the Bengals, and Sean Payton starts running his mouth again about the Super Bowl.

Overall record: 3-0

Kyle Fredrickson’s pick: Broncos 27, Bengals 14

The Broncos should not be intimidated by this version of the Bengals. Look for running back J.K. Dobbins to establish the tone with an early rushing touchdown. Then watch the defense feast on backup quarterback Jake Browning. You can’t lose on a last-second field goal if you have a multiple-score lead in the fourth quarter.

Overall record: 2-1

Colorado town tops list of “most beautiful ski towns”

The ski blog Unofficial Networks recently published a list of the most beautiful ski towns, and with Colorado’s stunning natural splendor it’s no surprise that one mountain town claimed the top spot.

To create the list, Unofficial Networks asked their readers “What is the most beautiful ski town?” Skiers from around the world shared their favorite picks, and the results included everything from hidden gems to iconic resorts. According to Unofficial Networks, the hundreds of comments spotlighted a variety of North American favorites and European classics.

According to Unofficial Networks’ chart of the relative popularity of ski resorts, Telluride claimed the top spot.

Founded as a mining camp in 1878, Telluride mixes “historic charm with modern ski lifts.” The ski resort features over 2,000 acres of terrain and a 4,425-foot vertical drop. It is also home to North America’s only free public gondola, which takes visitors on a 13-minute ride from the Mountain Village to the town.

However, Telluride wasn’t the only Colorado mountain town to make the list. Crested Butte and Vail also were named on the rankings.

With Colorado’s natural beauty and reputation for world-class outdoor recreation, it stands to reason that three of its mountain towns were recognized among Unofficial Networks’ most beautiful ski towns.

A voice trying to pull us back from the brink | Vince Bzdek

By Vince Bzdek

Two weeks after Charlie Kirk was assassinated in Utah, it’s worth noting what didn’t happen, especially in Utah.

“I want you to look at how Utahans reacted,” Republican Gov. Spencer Cox said after the suspect was caught.

“There was no rioting. There was no looting. There were no cars set on fire. There was no violence. There were vigils. And prayers. And people coming together to share the humanity.”

I give credit to Cox himself for that. As our politics reach a new boiling point, Cox has been one of the loudest voices trying to turn temperatures down.

“Over the last 48 hours, I have been as angry as I have ever been. As sad as I have ever been,” he said at that press conference. But Cox has not given into his anger and sadness and called for heads to roll. Just the opposite.

“As anger pushed me to the brink, it was actually Charlie’s words that pulled me back,” Cox said.

“I desperately call on every American – Republican, Democrat, liberal, progressive, conservative, MAGA, all of us – to please, please, please follow what Charlie taught me,” Cox said. “Always forgive your enemies – nothing annoys them so much.”

Cox implored folks on both sides of the aisle to dedicate themselves to ending this rising cycle of violence. In doing so he was echoing his longstanding calls, made in partnership with our own Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, for more civility in the nation’s political discourse, urging people to “disagree better.”

Cox launched the “Disagree Better” initiative in 2023 through the National Governors Association that he chaired at the time, and Polis vice chaired.

I heard them speak together about the push for a better politics before an audience in Fort Collins as part of CSU’s thematic Year of Democracy. At the time, I thought the campaign was idealistic, but maybe unrealistic. Now I think it is essential.

“Tell me more.” That simple phrase can spur a productive conversation between two people on opposite sides of a difficult subject, according to Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, left, and Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, who sat down with CSU President Amy Parsons for a forum on politics and civil discourse in 2023 at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. It was part of the “Disagree Better” initiative of the National Governors Association. Colorado Politics and CSU sponsored the event.

“Tell me more.” That simple phrase can spur a productive conversation between two people on opposite sides of a difficult subject, according to Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, left, and Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, who sat down with CSU President Amy Parsons for a forum on politics and civil discourse in 2023 at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. It was part of the “Disagree Better” initiative of the National Governors Association. Colorado Politics and CSU sponsored the event.“Disagreeing better doesn’t mean don’t disagree; people have different values, different faiths (and) different political opinions,” Polis said during that talk. “That’s what makes our democracy in our country so wonderful. But it’s how you handle that. How you let it lead to a better outcome. How do you form common cause?”

Cox echoed Polis’s words in his extraordinary speech just days after the shooting, emphasizing the measured, prayerful reaction of Utahans.

“And that, ladies and gentlemen, I believe is the answer to this.

“We can return violence with violence, we can return hate with hate,” he warned. “At some point we have to find an offramp or it’s going to get much, much worse.”

He made the point that freedom of expression, the very act that Kirk was exercising when he was killed, is the absolute key to moving beyond our current polarized state.

“We will never be able to solve all the other problems including the violence problems people are worried about if we can’t have a clash of ideas safely and securely. Even, especially, especially those ideas with which you disagree.

“That’s why this matters so much.”

He placed his highest hopes for an offramp to the violence in young people.

In remarks aimed directly at the young, Cox said: “You are inheriting a country where politics feels like rage. It feels like rage is the only option. Your generation has an opportunity to build a culture that is very different than what we are suffering through right now, not by pretending differences don’t matter but by embracing our differences and having those hard conversations.”

That gets really tough when you see the other side as a threat rather than someone to work with.

But if we don’t try to, Cox believes, our country will unravel.

“History will dictate if this is a turning point for our country,” he said at the end of his speech.

“But every single one of us gets to choose right now if this is a turning point for us.”

Cox’s calming comments in the face of national fury reminded me of another politician’s memorable speech after an assassination.

One terrible night in 1968, presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy went to a park in a Black neighborhood in Indianapolis to deliver the news in person that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot and killed.

Amid wrenching sobs and unearthly moans, standing on the back of a flatbed truck, Kennedy found his voice.

“You can be filled with bitterness. And hatred. And a desire for revenge,” he said, choosing words very similar to Cox’s. “We can move in that direction as a country, in greater polarization… filled with hatred toward one another.

“Or we can make an effort as Martin Luther King did, to understand, and to comprehend, and replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand, compassion, and love.

“What we need in the United States is not division,” he concluded. “What we need in the United States is not hatred. What we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness. It is love and wisdom and compassion toward one another.”

Every major city in the United States erupted in violence and flames and riots that night. But not Indianapolis. Indianapolis, like Utah after Kirk’s death, was peaceful and prayerful thanks to the compassion and understanding of a single leader.

At this fraught time, I thank heaven that we have perhaps found another leader who wants, more than anything, to “make gentle the life of this world.”

Denver police search for driver in fatal crash with bicyclist

Denver police seek the public’s help in finding a driver who fatally struck a bicycle rider on Friday night.

The crash, which occurred around 10:10 p.m., took place near N. Federal Boulevard at W. 26th Avenue, just northwest of downtown Denver, according to a Denver Police Department news release.

Police said the driver crashed into a bicyclist, then drove northbound on Federal without checking on the bike rider or contacting authorities.

The person riding the bike died from the crash.

Police haven’t provided an exact description of the suspect’s vehicle.

Authorities ask anyone with information to contact Metro Denver Crime Stoppers at 720-913-7867.

Another hunter dies in Conejos County wilderness

Another hunter has died in Conejos County wilderness, in the same area where two hunters were killed by lightning earlier this month.

According to reporting from Denver 7, the Conejos County Sheriff’s Office announced that a 54-year-old man from Tennessee died either late Friday or early Saturday.

Around 11:30 p.m. on Friday, a group of hunters called for help in an unspecified remote location in the South San Juan Wilderness. The caller said that CPR was being performed.

However, when search and rescue teams arrived the man had already died.

According to KKTV 11, an immediate recovery of the body was not possible due to nighttime conditions. A Flight for Life helicopter recovered the body on Saturday.

The cause of death and victim’s name have not been released.

The sheriff’s office also said that there is “no threat to the hunting public or those observing the fall colors in the area.”

This death follows the tragic deaths of two out-of-state elk hunters, Andrew Porter and Ian Stasko, in the same area.

Camille Pissarro retrospective coming to Denver Art Museum

Camille Pissarro’s retrospective is coming to the Denver Art Museum (DAM), and the Mile High City is the only U.S. venue to exhibit the first major show of the “Father of Impressionism” in 40 years. On Oct. 26, the DAM will open “The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism,” the latest in its autumnal series of blockbuster exhibitions.

The uplifting exhibit of almost 100 works presents Pissarro as a colorful art history character introduced through his dazzling paintings and also excerpts from his archive of personal letters. At a tumultuous time for many Americans, Pissarro inspires as a free-spirited and optimistic artist able to see harsh reality while believing the world can and should be a better place.

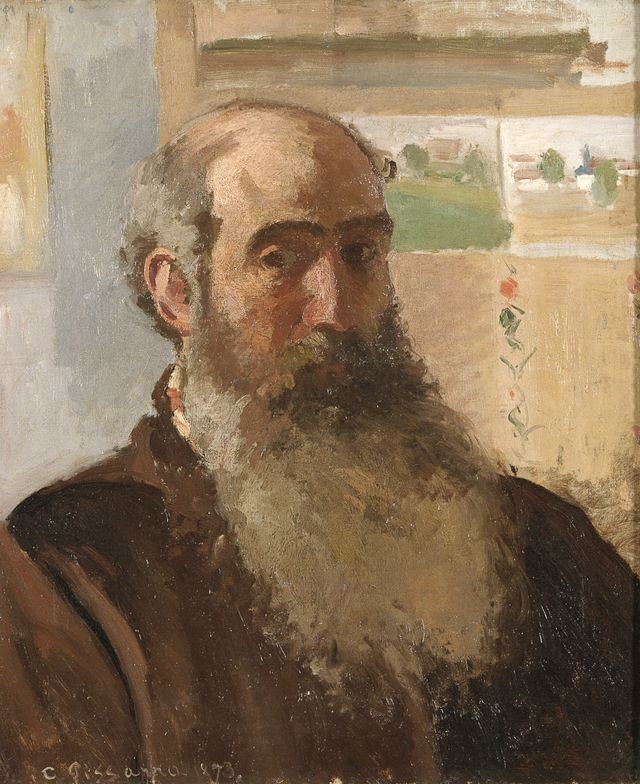

Pissarro’s self-portrait depicts the robust trademark beard he wore since at least his 30s. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum)

Pissarro’s self-portrait depicts the robust trademark beard he wore since at least his 30s. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum) “Pissarro was a cool guy. He’s the most interesting of all, the one I’d most like to meet,” said the DAM’s director, Christoph Heinrich, no stranger to the Impressionists. Heinrich has authored books about the Impressionists and co-curated the DAM’s major Monet show in 2019-2020.

“Pissarro was a true cosmopolitan, and that makes his life so interesting,” Heinrich said. “There was the belief that we are all in it together. Pissarro shows people in their dignity. ‘Respect’ might be an old-fashioned term these days that nobody wants to take seriously, but Pissarro shows us respect for very different environments and approaches to life. There is this true humanist stripe in all of his work and all of his statements, and how he looked at life is absolutely remarkable.”

A game-changing gift of Impressionist paintings

“The Honest Eye” shows through Feb. 8, 2026, exhibiting some of the most important paintings of Pissarro’s oeuvre, some never seen in the U.S. Befittingly, the DAM will mount the exhibit in the Hamilton Building — a 146,000-square-foot Daniel Liebeskind-designed, titanium-clad, origami-shaped structure named for the late Frederic C. Hamilton.

Pissarro, known for his authentic art, was the first to paint smokestacks. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum)

Pissarro, known for his authentic art, was the first to paint smokestacks. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum) In 2014, Hamilton and his wife, Jane, bolstered the DAM’s permanent collection with a donation of their 22 Impressionist paintings. “That bequest was really a game-changer for us,” said Heinrich. “This is a very good example of how a permanent collection can drive an exhibition. I truly believe if we hadn’t received the Hamilton paintings, we wouldn’t have tackled the Monet show, nor would we have done this Pissarro show. The ability of museums to do certain projects is driven by the curiosity of what we have in our collection. The richer and more comprehensive the permanent collection gets, the more opportunities.”

Heinrich sat for an interview in his office together with the DAM’s senior interpretive specialist, Lauren Thompson, and Angelica Daneo, co-curator of both the Monet and Pissarro shows.

Daneo said, “Pissarro had a hopefulness. He knew turbulent times with personal and economic difficulties, political tensions. Yet through his paintings, his letters, his actions, he showed an unwavering hopefulness and a willingness to go on. There’s a lot to learn from Pissarro — more than from other artists who are more guarded — something very inspiring one can apply to wherever they are in life.”

The DAM’s Pissarro show spotlights a quintessentially Impressionistic painting, one from the Hamilton collection, “Spring at Éragny” — “Definitely one of my darlings,” Heinrich said.

Thompson said, “It’s one of my favorites. It’s luminous. It’s joyful. And the figures in the painting are probably his wife, Julie, and his children.”

Pissarro primarily painted en plein air, yet when he suffered an eye malady, he painted inside looking out from a window. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum)

Pissarro primarily painted en plein air, yet when he suffered an eye malady, he painted inside looking out from a window. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum) In many ways seen and unseen, the exhibit highlights the value of relationships — Pissarro’s relationships with his family, peers and his working-class neighbors depicted in his rural paintings, as well as, naturally, his painterly relationship to landscape, to light. Pissarro’s importance in the art scene of his time is evidenced by his friendships with other celebrated artists: Claude Monet, Paul Cezanne and Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, George Seurat, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and the American, Mary Cassatt.

The exhibit’s many sponsors include Barbara Bridges — an educator and entrepreneur who founded Women+Film and formerly chaired the board of the Women’s Foundation of Colorado. Bridges, also an Impressionist fan, praised Pissarro’s leadership. “Camille Pissarro is known as the ‘Father of Impressionism,’ partly because he was a bit older than the others, but also because he acted like a father in holding the group together and encouraging the other members,” she said.

This past summer, Bridges saw the Pissarro show in Potsdam, Germany, at the Museum Barberini — the only other venue for the exhibit. “It’s fabulous. In this exhibition people will learn about Camille Pissarro. It takes us from his earliest paintings through the stages of his life’s works,” Bridges said. “I think people will love it!”

Pissarro painted and lived authenticity

Heinrich spoke to the exhibit’s title: “The Honest Eye.” He said, “What strikes me is Pissarro’s striving for authenticity. Pissarro wanted to paint exactly what his eyes were seeing at this moment. This authenticity is a striking motif in his whole life. He’s transferring what he sees, not editing. I find that refreshing in a time when things are Photoshopped or edited or an AI-altered image that loses the core. Pissarro’s striving for giving a picture that is authentic, giving an experience that is authentic still has something to teach us today.”

In addition to painting landscapes, Pissarro painted Paris cityscapes. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum)

In addition to painting landscapes, Pissarro painted Paris cityscapes. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum) Heinrich and Daneo began planning the Pissarro show in October of 2019, the day after opening the Monet show — also a collaboration with Museum Barberini. The director and the curator realized the collective holdings of the two museums included more than a dozen Pissarro artworks could provide a foundation for this retrospective. The DAM also will show Pissarro works from American museums such as the National Gallery in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. International lenders to the exhibit include the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the Muse’e d’Orsay in Paris and the National Gallery in London.

Daneo said, “Some of the loans visitors will see are something I am pleasantly surprised by — something that needs to be celebrated.”

Pissarro the person, Pissarro the painter

Like one of his pointillist canvases composed of countless daubs of paint synthesized as a whole, Pissarro presents as a man of many aspects. Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born in 1830 to well-heeled Sephardic Jewish parents of French and Portuguese extraction living on St. Thomas, an island then part of the Dutch West Indies. Pissarro never used his Hebrew names.

“He was fiercely secular,” Thompson said.

In the exhibit, the DAM devotes a gallery to Pissarro’s early, lesser-known works inspired by his time living in the Caribbean and Venezuela. Pissarro broke ranks with the family business to become an artist rather than a merchant. He married the family’s maid and established his family in France. Significantly, Pissarro was the only painter to show in all eight Paris Impressionist exhibitions.

Pissarro engaged with literature, poetry and politics. He spoke French, Spanish and English. Pissarro consistently recreated himself and varied his subject matter. The exhibition includes landscapes, cityscapes, harbor paintings, portraits, figures and still-life works. Pissarro painted not only romantic pictures, but also the pork butcher, the poultry market, the brick yard. He painted not the bourgeoisie, but the washer woman, the shepherdess, haymakers, peasant girls and gardeners.

The Denver Art Museum’s Pissarro retrospective will present 100 artworks from private and institutional lenders. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum)

The Denver Art Museum’s Pissarro retrospective will present 100 artworks from private and institutional lenders. (Courtesy Denver Art Museum) Pissarro painted in oils on canvas, watercolors and pastels on paper. He toggled between Impressionism and Pointillism and at one point melded the two. He sketched. He drew political caricatures. A portion of the exhibition presents Pissarro’s silk fans painted with gouache. He experimented with ceramics and printmaking.

“He had the curiosity to reach out and be interested,” Heinrich said.

Pissarro’s letters reveal the man

Pissarro also distinguished himself by penning thousands of letters to his family, his art dealer and fellow artists. Drawing from this trove of source material, the DAM team patched together details from the painter’s life presented in the exhibit.

“It was a real privilege to start with the letters, the words of the artist. Pissarro pours himself into his letters and doesn’t shy away from sharing his ideas. That allowed us to bring out the human component. ‘Freedom’ is a big motif throughout his letters. He seeks to be absolutely free: freedom of thought and freedom to make choices in life, which he did, but also freedom in art is something he’s consistent about,” Daneo said. “Pissarro felt like an outsider, but his outsider status contributed to his greater experimentation in life and in [painting] styles. He believed he shouldn’t feel bound.”

Thompson said some of Pissarro’s letters were translated for the first time into English. “A deeper dive into his correspondence reveals the man: his worries, complaints, medical issues, his hopes, what’s going on with the family. We find his personal philosophies, politics, local gossip,” she said.

“Ultimately, he was an optimist and maintained a sense of optimism, through challenging personal and professional situations. Three of his children died. He fled the Franco-Prussian War. The Dreyfuss affair happened in Paris,” Thompson added. “In a letter to his landlord, he said 20 years of his life’s work had been destroyed in the war, but ultimately he wanted to get back to work.”

Pissarro valued the liberty of artistry

Heinrich said, “Pissarro believed art is the only and unique profession where you’re free. You decide what you’re doing. You’re not a boss to somebody, and you don’t have a boss. It’s not work that you do one part of it and somebody else finishes it. Only an artist is completely free and self-determined,” Heinrich said.

Pissarro’s insistence upon freedom did cost him: “There’s a joke that he painted cabbages and his wife cooked them,” said Heinrich. “They had hardship.”

Pissarro never realized much financial reward from his art, unlike his friend Monet, who granted Pissarro a loan for his home outside Paris. Yet in 2014, at auction, Pissarro’s “Le Boulevard Montmartre, Matinée de Printemps” fetched $32.1 million.

In closing, Thompson said, “Pissarro wrote that all an artist should wish for is to find a kindred spirit to understand him. We invite visitors to be those kindred spirits.”

The legacy and loss of Colorado’s once-mighty glaciers

High in the Indian Peaks Wilderness beyond her home in Boulder, Millie Spencer has been venturing to an extreme, jagged place of rock and ice.

“Especially since I became obsessed with this idea of watching its decline,” she said.

Like others before her, the Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado-Boulder has been drawn to the plight of what might be Colorado’s last glacier: Arapaho Glacier.

Others before her include Dan McGrath, a glaciologist and professor at Colorado State University. Earlier this month he joined a research flight over a dozen snowbound sites around the state — sites with “glacier” in their names but not meeting a scientific standard to be defined as such.

“More so snow fields or perennial snow and ice (patches) than glaciers,” McGrath explained. The fields were no longer masses large enough to subtly move under their own weight, as true glaciers do.

As Arapaho Glacier does, researchers suspect. McGrath also suspects Andrews Glacier does — perhaps the only correctly named “glacier” among several in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Andrews Glacier high in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath

Andrews Glacier high in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrathThe sign along Interstate 70 reads “St. Mary’s,” not “St. Mary’s Glacier,” as the popular destination has been popularly called.

“It used to be a glacier, I assume,” said Bruce Raup, the senior associate at the Boulder-based National Snow and Ice Data Center. “But it’s been a while.”

Colorado has been warming with the rest of Earth, and glaciers everywhere have been shrinking and vanishing. Melting glaciers are a major, well-documented source of sea level rise. A study between 2006-2016 quantified the global loss at around 335 gigatons a year — or enough glacial melt to fill close to 130 million Olympic-sized swimming pools a year, as McGrath has noted.

Tracking this loss has been a more recent mission of a database Raup oversees, called the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) initiative. Analysts at Rice University went with a more straightforward name for their database similarly in early development: the Global Glacier Casualty List.

It’s indeed “early days” for GLIMS, Raup said. “So only a couple hundred glaciers so far,” he said. “But we’re in the process of getting more data from various collaborators around the world.”

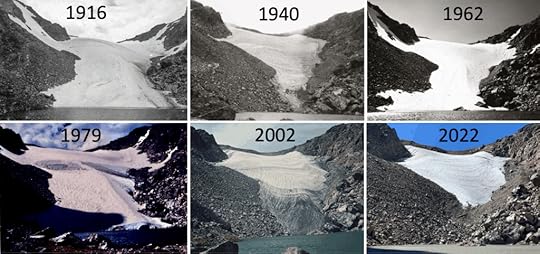

Including in Colorado. This month Raup flew with McGrath over those glacial sites, gathering imagery and adding to a collection that spans the last century. From around the turn of the 1900s to today, images show snow and ice drastically fading at Arapaho and Andrews glaciers.

Colorado State University professor and glaceologist Dan McGrath compiled these photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center showing changes over the years at Andrews Glacer. 1916 Willis Lee/NSIDC; 1940 Paul Nesbit/NSIDC; 1962 C.B. Harris/NSIDC; 1979 and 2002: Russell Allen/NSIDC; 2022 McGrath.

Colorado State University professor and glaceologist Dan McGrath compiled these photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center showing changes over the years at Andrews Glacer. 1916 Willis Lee/NSIDC; 1940 Paul Nesbit/NSIDC; 1962 C.B. Harris/NSIDC; 1979 and 2002: Russell Allen/NSIDC; 2022 McGrath.To Spencer, the images are “heartbreaking.” Why? That’s the question she’s been exploring.

As part of her dissertation, she’s been exploring the sociocultural impacts of disappearing glaciers in Chile. Glaciers are much bigger there and in other parts of the world compared with Colorado. And yet the emotional loss seems no lesser to Spencer.

Why? she has asked in a brief paper she’s drafted on Arapaho Glacier. She titled the paper “On Death and Dying.”

In summary, she said: “What does it mean to lose these parts of the landscape that contribute so much to our sense of place?”

Yes, glaciers have contributed greatly to Colorado.

Arapaho Glacier in Indian Peaks Wilderness. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath

Arapaho Glacier in Indian Peaks Wilderness. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath“The ruggedness of our mountains is a direct result of glaciers,” said Vincent Matthews, the retired director of the Colorado Geological Survey.

Last year he published a book, “Land of Ice: Jaunts into Colorado’s Glacial Landscape.” The book offers a crash course on eras of glaciation, including some 20,000 years ago, when snow and ice coated much of the Front Range. Glaciers thousands of years earlier carved the Rockies, leaving the kind of U-shaped valleys we see, for example, at the Maroon Bells.

It’s but one cherished scene depicted in Matthews’ book of “jaunts.” He suggests more road trips showcasing many more remnants of glaciers: the sculpted ridges, aretes and cirques of Rocky Mountain National Park, for example. Those features decorate the San Juan Mountains and the opposite, northwest mountains around Steamboat Springs, where Matthews points to a terminal moraine by the Walmart. He likes to call Turquoise Lake “the most famous terminal moraine.” He calls the Grand Mesa “a grand ice cap.”

Glaciers, he writes, could be thanked for shaping the corridors of our scenic highways. They could be thanked for the ski terrain we love. They could be thanked for some of our drinking water. And maybe glaciers could somehow be thanked for saving the world.

Referring to the U-shaped valley that was home to the 10th Mountain Division, Matthews writes: “Glaciers created the landscape that prompted the Army to select this area for training an elite force that played a key role in winning World War II.”

Camp Hale, like much of Colorado’s topography, is the result of a more recent period of glaciation referred to as the Little Ice Age. This was around the years 1650-1850, Matthews writes.

“Then the climate began warming again, and the glaciers retreated. Enjoy them while they survive.”

Moomaw Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath

Moomaw Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrathJust how much longer Colorado’s glaciers will survive — if any could still be called a glacier — has been of some debate this century.

Particular focus has centered on Arapaho Glacier, which has long captured the fascination of onlookers from Boulder.

An adventurous botanist, Herbert N. Wheeler, wrote of a visit in the summer of 1897. He wrote of walking across the ice and coming by cracks “at first a few inches wide and then several feet wide.” This was “rather terrifying,” he recalled. “We dropped rocks down into the crevasses but didn’t hear them strike bottom.”

However terrifying and immense, the glacier was probably retreating at that time, later researchers surmised.

Using imagery throughout the decades and modeling technology, University of Colorado-Boulder scientists found Arapaho had lost 52% of its area throughout the 1900s. This was documented in their 2010 paper, which also delved into climate data and projections, similar to a paper from a few years prior. Based in Rocky Mountain National Park, that 2007 paper concluded: “Glacier recession on the Front Range at present may be greater than at any other time in the historic record.”

Warming temperatures that shrunk Arapaho Glacier in the previous century were increasingly warming in this century, researchers wrote in 2010: “If recent trends in area loss continue, Arapaho Glacier may disappear in as few as 65 years.”

But the study pointed to peculiar, potentially sustaining aspects of the glacier’s position.

Arapaho is “in a protected cirque environment,” explained McGrath, the Colorado State University glaciologist. Thanks to surrounding mountains, “it’s topographically shaded,” he said, and often gaining snow from avalanches.

Compared with others globally, Colorado’s glaciers “are a little bit different in that they’re highly dependent on wind distribution of snow,” added Raup at Boulder’s National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Arapaho and Andrews glaciers benefit from snow-giving westerlies. And they benefit from high elevation temperatures that, amid warming, could keep precipitation falling as snow instead of rain, unlike other parts of the West.

That’s at least for the foreseeable future. Projections for seasonal snowpack “are quite, quite grim for later this century,” McGrath said.

And “without a doubt,” he said, “the loss of glaciers here in Colorado would impact local ecosystems.”

The perennial snow is essential to the pika, for example, and also to the white-tailed ptarmigan, which makes a seasonal home in the alpine. Many more animals and plants have counted on glacial melt feeding streams downslope.

Arapaho Glacier’s perennial runoff has also fed Boulder’s drinking water supply — “miniscule when compared to the relative contributions of rain and seasonal snow,” Spencer, the Boulder Ph.D. student, wrote in her brief.

No matter that small impact, “On Death and Dying” seemed the right title for the paper. Because “the sociocultural impact of the glacier’s death is immense,” Spencer wrote.

On her regular ventures to Arapaho, she’s met skiers missing the snow they once knew. She’s met longtime hikers. “They’ll bring up pictures they have of their family there in the ’50s at the top of the glacier, and how different it looks today,” Spencer said.

She hasn’t been around that long; she’s only seen the loss in those photos. And yet hiking to Arapaho somehow feels sad and nostalgic, she said.

“Maybe it’s more like secondhand nostalgia, and I’m mourning this experience that I may not get to always have,” she said. “Or if I have a kid, knowing these glaciers might not be around for the next generation. They might just be stories passed down.”

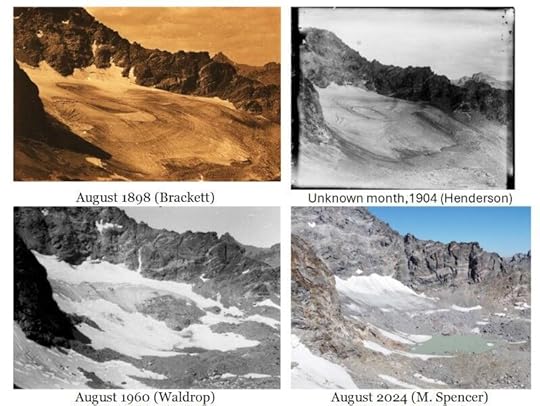

University of Colorado-Boulder PhD candidate Millie Spencer compiled these photos showing changes at Arapaho Glacier over time. The photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center are from 1898 (Brackett); 1904 (Henderson); 1960 (Waldrop); and 2024 (Spencer).

University of Colorado-Boulder PhD candidate Millie Spencer compiled these photos showing changes at Arapaho Glacier over time. The photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center are from 1898 (Brackett); 1904 (Henderson); 1960 (Waldrop); and 2024 (Spencer).

September 27, 2025

CU Buffs vs. BYU | 3 takeaways from Colorado’s loss in Alamo Bowl rematch

BOULDER — Colorado’s Folsom Field magic has disappeared, it seems.

Despite taking an early 14-0 lead less than 10 minutes in, Deion Sanders and the Buffaloes allowed 17 unanswered points in a 24-21 loss to No. 25 BYU on Saturday night.

In a rematch of last year’s Alamo Bowl in San Antonio, CU was much more competitive but came up short on a last-minute drive to try and win the game.

Here are three takeaways from the loss that drops Coach Prime’s team to 2-3 on the season and 0-2 in Big 12 play.

Freshman QB carries BYU

He may look silly wearing No. 47, but the Cougars have themselves a quarterback of the future in Bear Bachmeier. The true freshman didn’t look like someone making just his fourth career start in the toughest environment he’s ever played in in his life.

Bachmeier was BYU’s engine offensively, leading the way with both his arms and his legs. He finished 19-for-21 passing for 179 yards and two touchdowns, also adding a game-high 98 yards with his legs.

This probably wasn’t a game where Coach Prime expected to get out-played at quarterback, but that’s just what happened.

Buffs’ fast start

If you blinked, you may have missed it, but offensive coordinator Pat Shurmur was in his bag, as the kids say, to start Saturday night’s game.

Whether it was pre-snap movement or run-pass-option plays that allowed quarterback Kaidon Salter to make quick decisions, the Buffs were able to go down the field and score touchdowns on their first two possessions. They needed just 15 plays and less than seven minutes to do it, too.

But after that, it was much of the same from CU. They managed just one touchdown drive the rest of the game as the offense sputtered against a BYU defense that found a way to contain the Buffs’ rushing attack.

Penalties haunt CU

The CU secondary just isn’t the same without Travis Hunter.

It turns out the Heisman Trophy winner was covering up a lot of warts deep downfield, as the Buffs haven’t been the same in coverage through four games. Typically reliable starters DJ McKinney and Preston Hodge struggled again, each picking up penalties in coverage that extended BYU drives.

In total, Coach Prime’s team finished with six penalties for 67 yards, and it felt like every one of them came at the absolute worst time.